Richelieu A Domestic Tragedy (1825) & The French Libertine (1826)

Author

John Howard Payne (1791-1842)

Payne was born in New York City and his theatrical career began early when he submitted theatrical reviews to newspapers at the age of 12, began a short-lived Thespian Mirror at the age of 14, and wrote his first play Julia at only 15. He started acting in 1809, aged 18, and he was one of the first Americans to play Hamlet. Although his debut season saw him dubbed the ‘American Roscius’, his career waned almost immediately.

His second play was an adaptation of Kotzebue’s Lovers’ Vows (of Mansfield Park fame) and this was to set the tone for much of his later work: adaptation was to prove profitable for him. He moved to Britain in 1813 but his second attempt at an acting career, which began in Drury Lane, did not take off. He then translated a French melodrama La Pie Voleuse (1815) and produced an adaptation with such speed and ‘rightness’ that Douglas Kinnaird, manager of Drury Lane, hired to him to supply the theatre with as many adaptations as he could manage. Payne even went to Paris for a time to more swiftly turn his plays around.

Despite his considerable output and success, Payne was poorly paid. This remained the case when he went to work at Covent Garden for a couple of years. He wrote Brutus (1818) at this time and it became one of the best-known tragedies of the nineteenth century, particularly in America. Continued poor treatment at the hands of the patent theatres encouraged him to open his own theatre at Sadlers Wells; this was a disaster and he went to prison for debt. He fled to Paris where he continued to produce adaptations, notably Clari which contained the song ‘Home, Sweet Home’ which became hugely successful (but with no great financial benefit to Payne). In Paris he also renewed his friendship with Washington Irving and they collaborated on a number of plays, including Charles the Second, a comedy that also received attention from the Examiner particularly for suggestions that the monarchy was corrupt and dissolute.

He courted Mary Shelley briefly in 1824-25 back in London before returning to America in 1832. Here he was greeted with the public regard and fame that had eluded him in Britain – he was finally recognised as a man of letters. Political activism on the part of the abolitionist movement saw him expelled from Georgia in 1835. In 1842 he was appointed American consul at Tunis, was recalled by the next administration, and sent again in 1851 where he died in 1852.

Plot

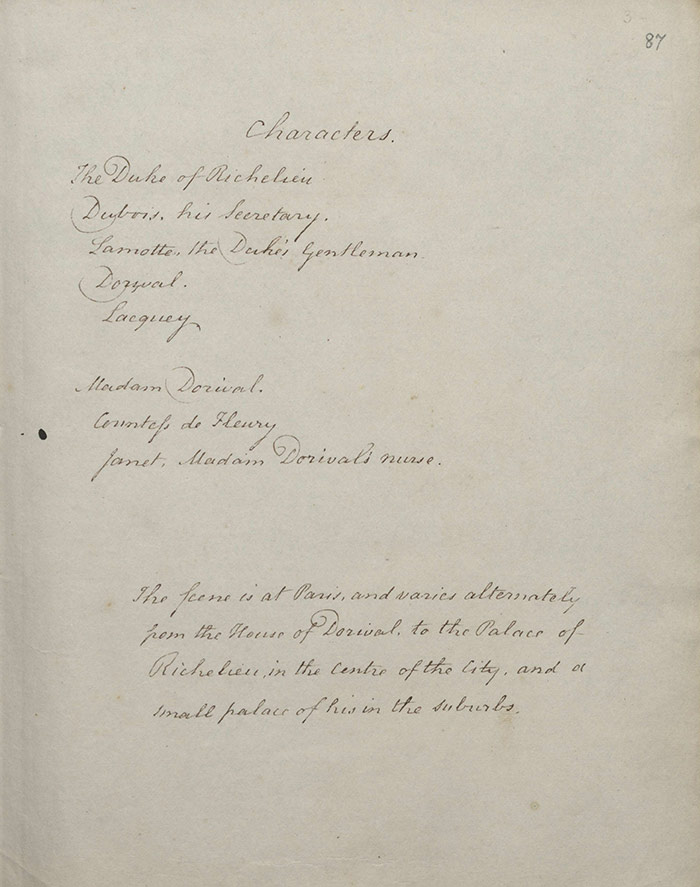

The plot synopsis is based on the original version (ADD MS 42875); significant alterations are discussed in the censorship section below.Act 1

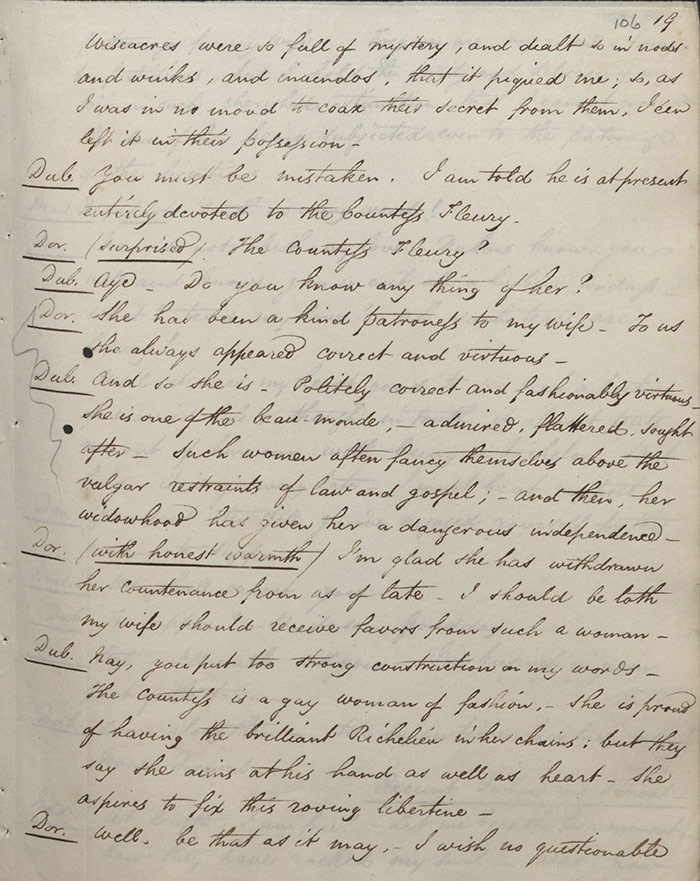

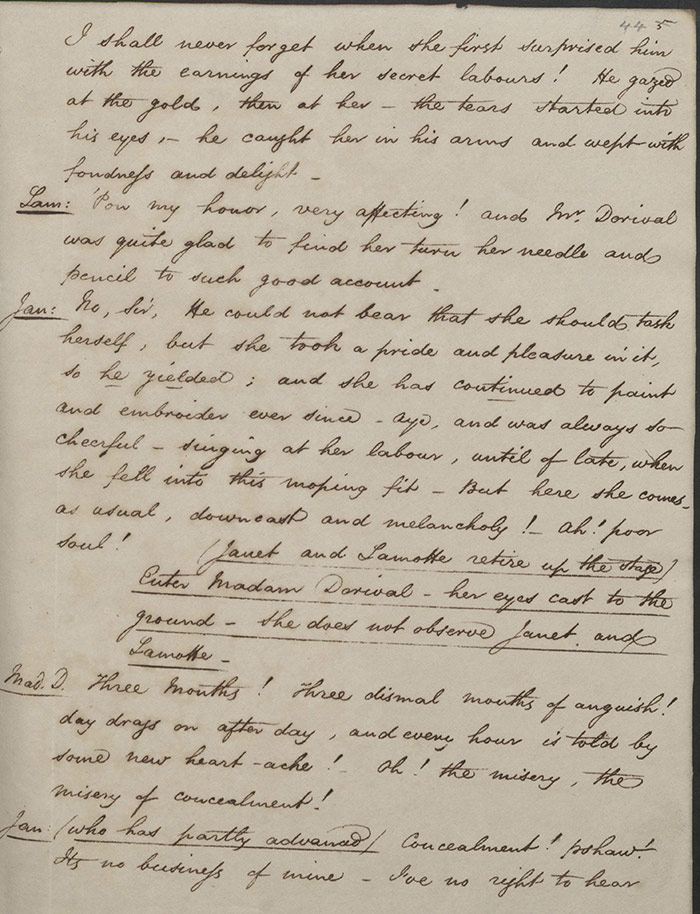

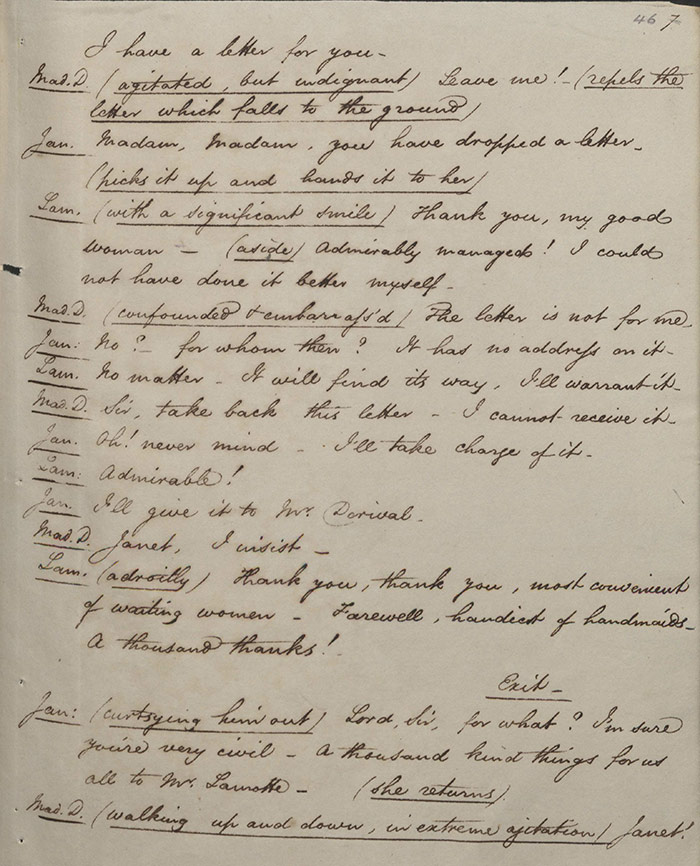

Lamotte, servant to the Duke of Richelieu (Rougemont in the second version), calls on the Dorival household. He is pretending to be acting for himself and seeking Mr Dorival. In truth, he is the agent of the Duke of Richelieu (who has previously adopted the guise of Lamotte in an attempt to seduce Madame Dorival). When he leaves, after successfully leaving a letter from Richelieu, Janet, nurse to Madame Dorival, finally gets an explanation for Madame Dorival’s languid and disconsolate behavior over the past few months. The Duke of Richelieu, disguised as Lamotte, had inveigled his way into the good graces of Mr and Madame Dorival by purchasing some of her drawings before revealing his desire for her. This culminated in her rape, after which she has been consumed by guilt as she holds herself largely to blame, much to the consternation of the more worldly Janet. Dorival arrives home, bringing with him their friend Dubois who has been made a protégé of the Duke. Dubois makes reference to Richelieu’s libertinism and Dorival tells his wife that he has heard Richelieu has had an intrigue in their neighborhood. Dubois insists that Richelieu is fixated on the Countess Fleury who has also been a patron of Madame Dorival. Fleury is a widow with, it is rumoured, aspirations to settle the libertine Richelieu for herself. Dubois leaves, promising to return for supper, and the act ends with Madame Dorival lamenting her situation.

Act 2 (f.109)

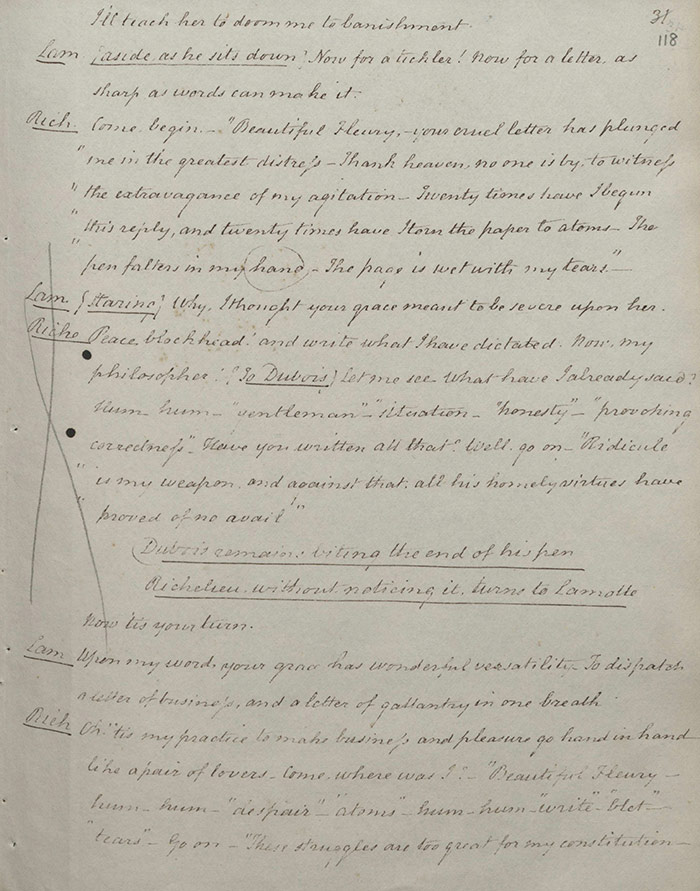

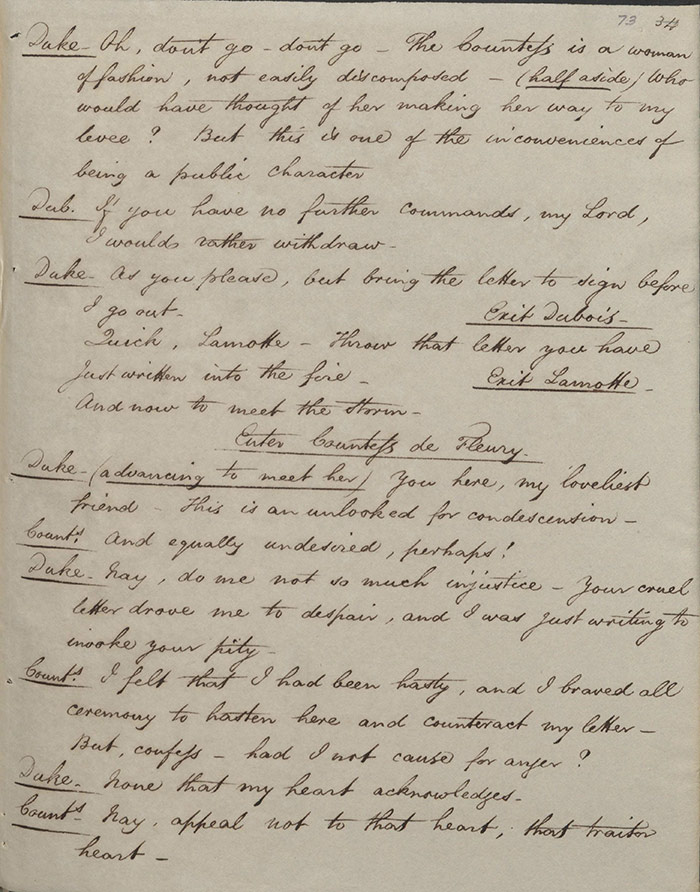

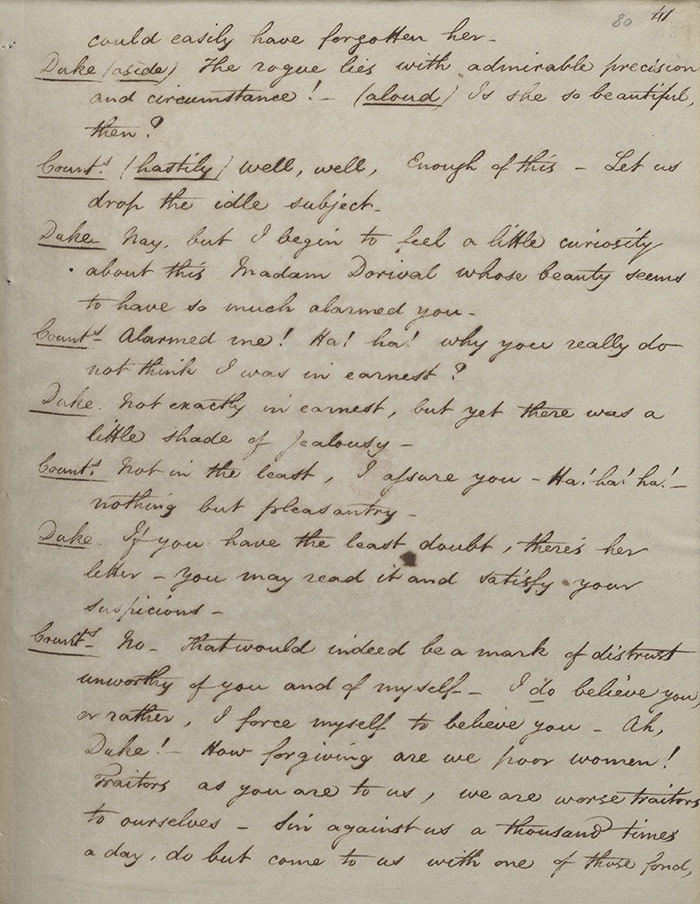

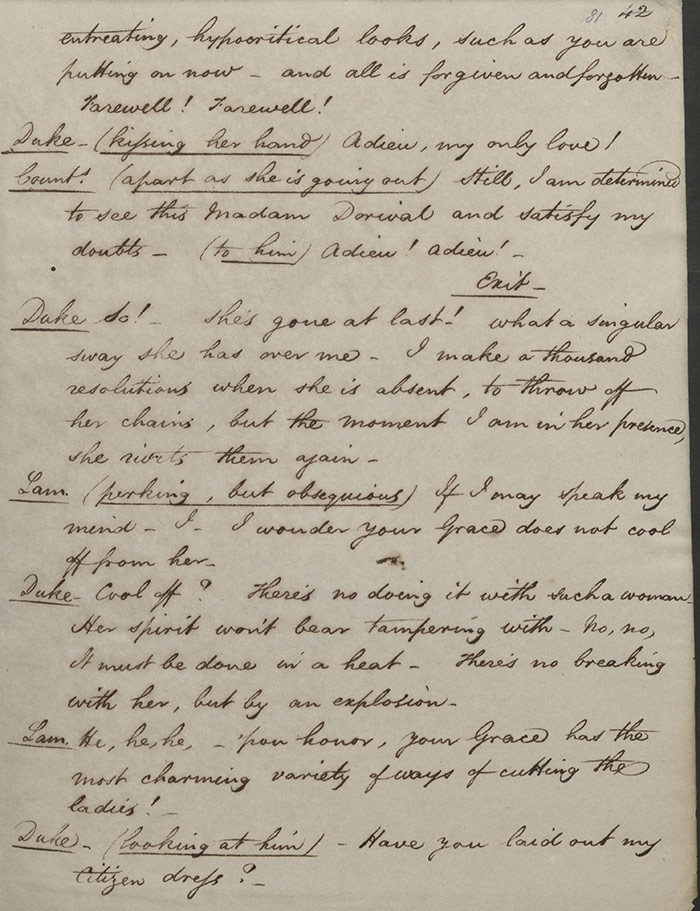

The Duke of Richelieu and Lamotte discuss Madame Dorival and Countess Fleury. Richelieu expresses some remorse for the rape and intimates he may be falling for Madame Dorival. He is more dismissive of the Countess who, Lamotte tells him, believes she will marry him. Dubois enters as Lamotte leaves and they talk about a recent battle, Richelieu expressing his horror at the death of nobility (but no regret for the common soldier). Lamotte re-enters and Richelieu dictates dissembling letters to an admiring Lamotte and an appalled Dubois. The Countess Fleury enters and attacks Richelieu for bad faith; he dissembles, professing his love for her. Janet then arrives to return the letter Lamotte left but is recognized by Countess Fleury whose suspicions are roused. After Janet leaves, she quizzes Richelieu who gets Lamotte to insist that it was he alone who ordered embroidery from Madame Dorival. Indeed, he turns it around on the Countess by pretending to be piqued by Lamotte’s description of Madame Dorival’s beauty to the point that she apologises, worried that she had provoked his interest in a rival where there was none. After she leaves, Richelieu resolves to adopt his disguise as Lamotte again and connive his way into Madame Dorival’s affections again. Dubois enters and he quarrels with Richelieu as he refuses to write a letter dismissing someone from office for dishonourable motives. Richelieu is at first enraged at the defiance and then tolerates it.

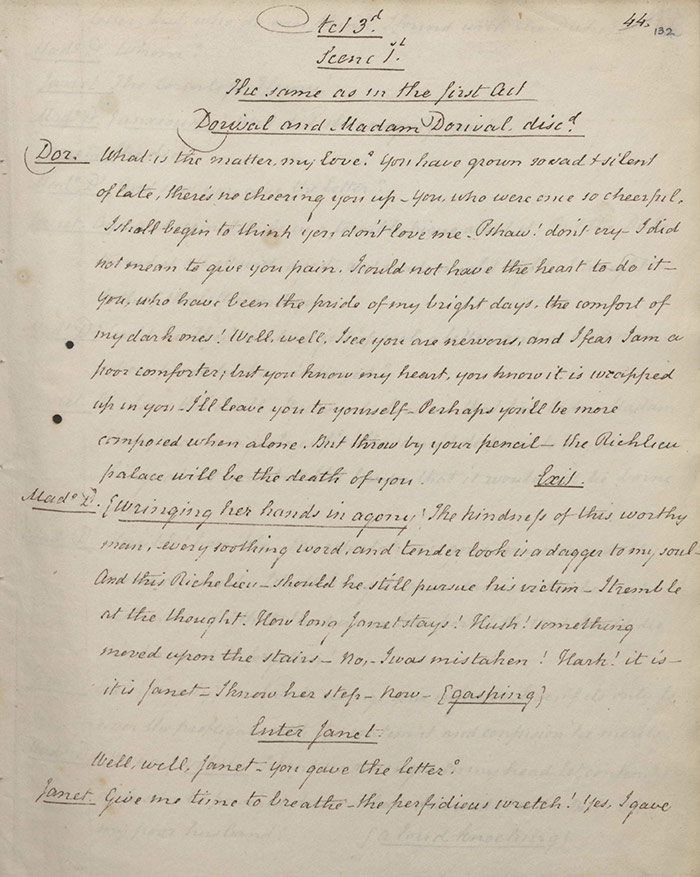

Act 3 (f.132)

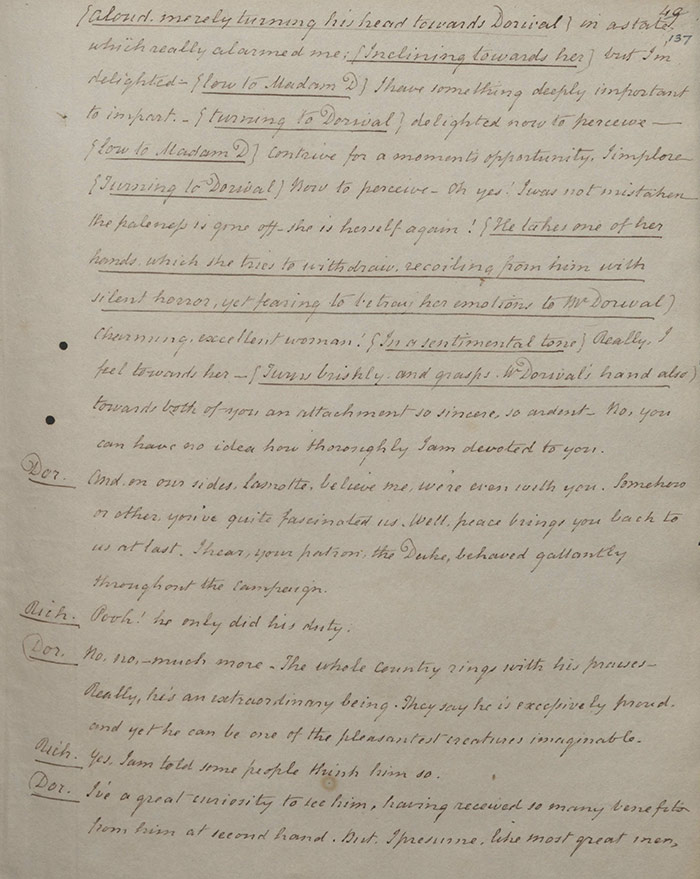

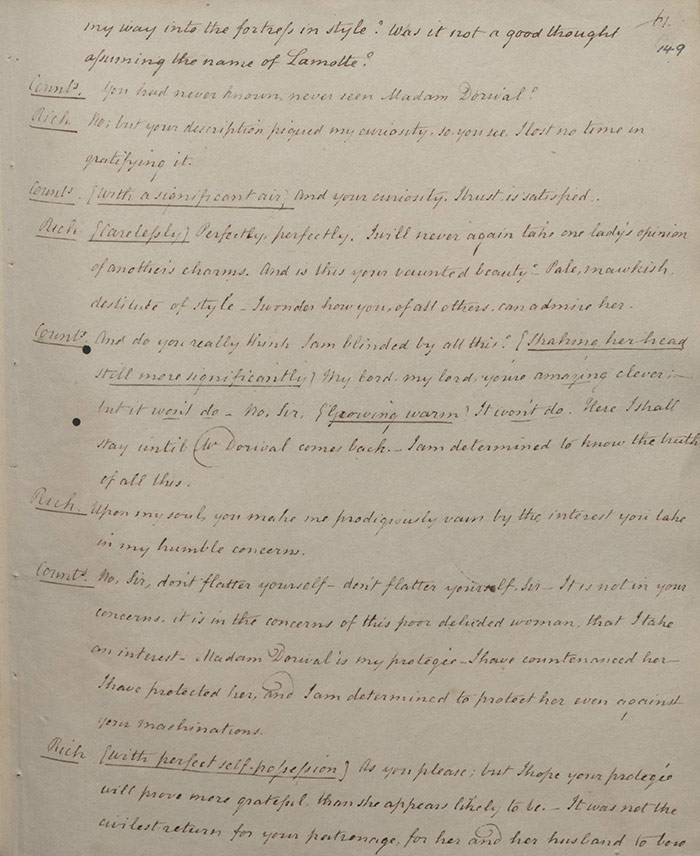

Richelieu calls on a distraught Madame Dorival. Janet calls for Mr Dorival in an effort to thwart Richelieu. Dorival welcomes ‘Lamotte’ to his home and they discuss the character of Richelieu about whom Dorival has heard much. ‘Lamotte’ defends Dorivals’ attack on Richelieu’s morals by suggesting that power, attractiveness and rank mean that he cannot be held truly accountable for his actions. Richelieu engineers some time alone with Madame Dorival by requesting a painting that his putative master has requested. He pleads his case and is rebuffed. On his return Mr Dorival invites Richelieu to supper which Janet thwarts by inventing a previous dinner engagement for Madame Dorival. However, aside, Richelieu determines to direct the coachman to bring her to his palace. Countess Fleury arrives and is shocked to discover Richelieu at the Dorival residence. He convinces her to maintain his subterfuge, maintaining that it is the first time he has seen the Dorivals and he is only there because he was curious to see the famed beauty. She is not entirely convinced and determines to bribe the real Lamotte for the full story.

Act 4 (f.152)

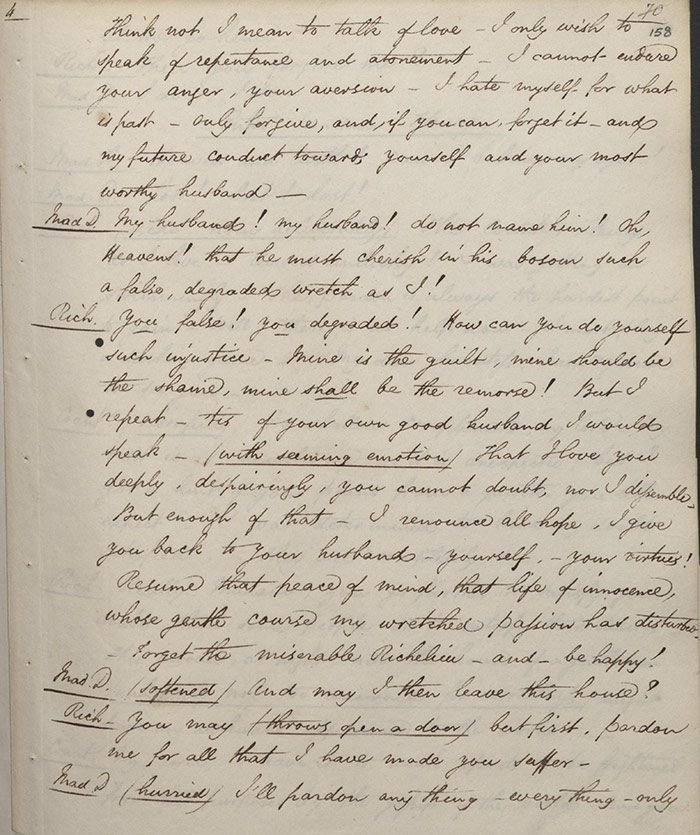

The Duke of Richelieu awaits Lamotte’s delivery of Madame Dorival. Dubois enters and is disturbed by Richelieu’s lack of scruples in engineering an embassy place through the offices of the Regent’s mistress. He isfurther perturbed by Richelieu’s casual attitude towards using force to bring a woman to him (although Dorival is unaware that it is Madame Dorival). Richelieu wants him to deliver a letter to the Regent’s mistress that will help her justify her choice for the embassy job. When Lamotte enters and tells that Madame Dorival is shouting for help, Dorival exits in horror while Richelieu scoffs at his morality. Madame Dorival, extremely distraught, is brought into him. In vain, he tries to calm her down and then Countess Fleury enters. In the violent remonstrations that follow, the Countess renounces Richelieu and finds herself affected by Madame Dorival’s sincere distress. Dubois is heard approaching and Madame Dorival, panicked, hides behind a screen. Dubois tells Richelieu that he must go to the Regent to secure the embassy appointment. He leaves and the Countess decides, as an act of kindness, to implore Dubois to aid the poor woman hiding behind the screen. He agrees and is amazed to discover Madame Dorival who suffers a heightened bout of anguish at being found out by her husband’s friend. Nonetheless, she agrees to be escorted away by him

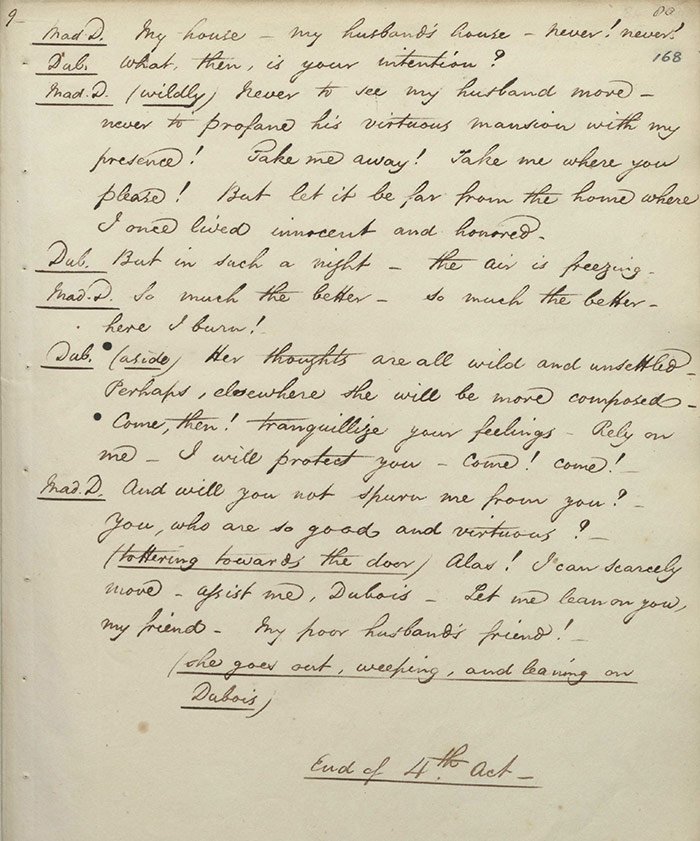

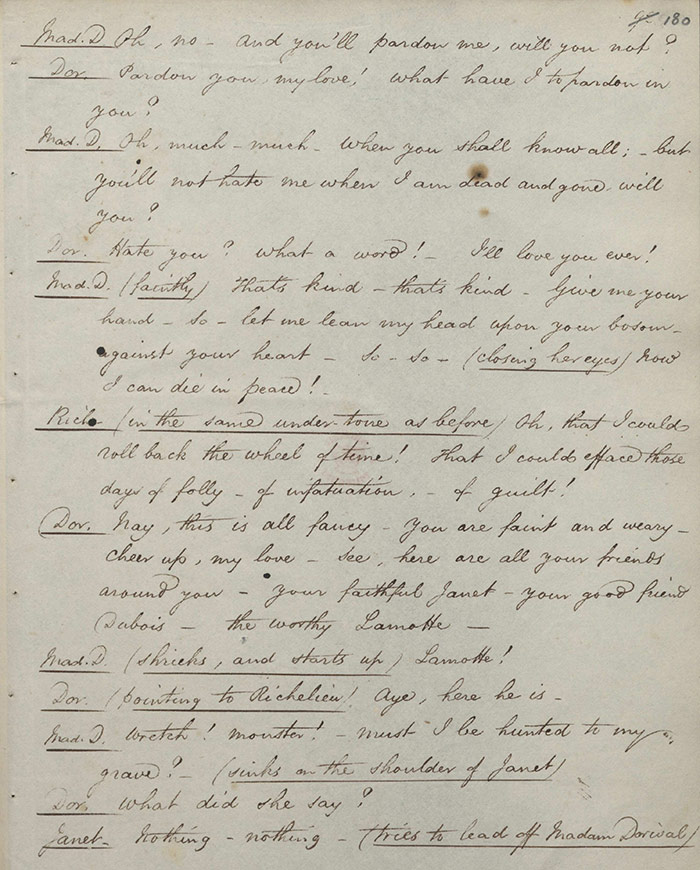

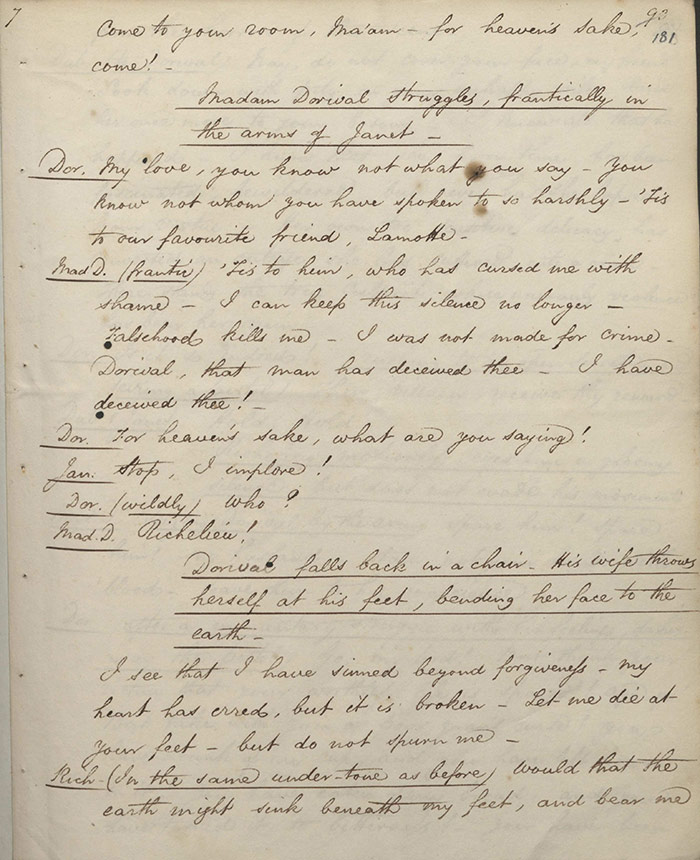

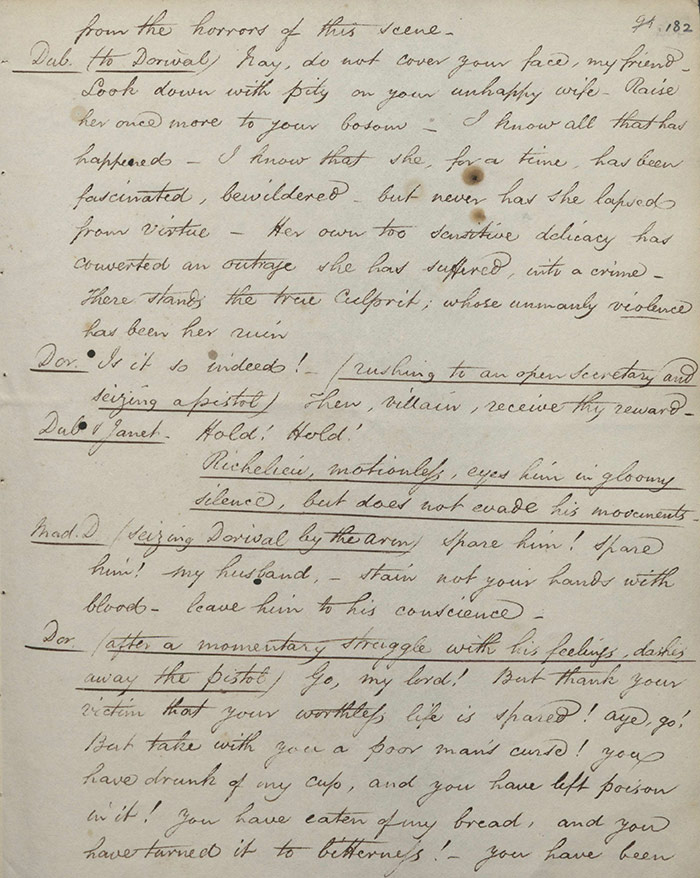

Act 5 (f.169)

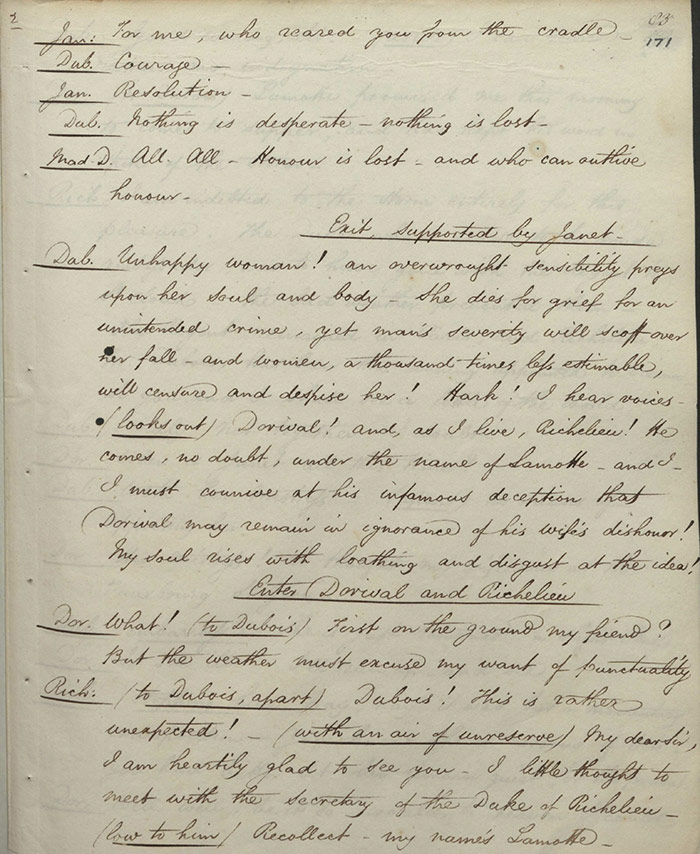

Dubois brings her home where Janet finds out that her satisfaction in defying Richelieu was misplaced. Madame Dorival is increasingly distraught and melancholy and is led away by Janet. Dorival and Richelieu (as Lamotte) enter, the latter surprised to find Dubois there, the former to hear that his wife has returned from her supposed dinner. Dubois speaks coldly and pointedly about Richelieu’s character to Richelieu (as Lamotte) in front of Dorival. Their exchange gets increasingly heated to Dorival’s bemusement. He goes to bring his wife down and Dubois pleads with Richelieu to depart; he scornfully refuses. Dorival brings in his wife, now somewhat delirious, hinting at her shame to his puzzlement until she confesses in front of all. Dubois defends her honour and points to Richelieu as the true culprit and Dorival, now aware of his true identity, threatens to shoot him before relenting. Richelieu is now suffering from a genuine and terrible remorse. Madame Dorival dies, somewhat relieved after seeing her huband’s tears which she understands to imply forgiveness, and Richelieu rushes out in horror.

Performance, publication, and reception

Richelieu: A Domestic Tragedy was submitted to the Examiner by Charles Kemble on 19 December 1825. A number of changes were demanded, and the altered version of the play was resubmitted towards the end of January. A couple of additional changes were requested and the piece—now titled The French Libertine—was finally licensed on 28 January 1826. The detailed correspondence of Kemble, Colman and Montrose may be seen below.The piece was first performed on 11 February 1826 at Covent Garden Theatre. Harrison records that there were only 5 performances of it before it was withdrawn as ‘the strong arm of power’ was against it in addition to receiving ‘the abuse of the papers as immoral’ (105). Performances certainly took place on 13, 14 and 16 February. The reviews indicate that the play provoked strong approval and disapproval as well as some bemusement as to why the Examiner felt obliged to intervene.

The Theatrical Observer was a great champion of the play. Its initial review (13 February) dryly noted that the play that had ‘struck such terror into the heart of Mr. Colman’ had ‘exploded’ on Saturday night without ‘any irreparable injury to the loyalty or morality’ of the Covent Garden audience. Despite finding the title somewhat irritating, it insisted that it was ‘the most successful dramatic production of its kind which we have seen for many years, and its merits are of a high class’. The situations were ‘deeply interesting to the last’ and the dialogue ‘may claim the praise of strength, vivacity, and much wit’. There is praise for the costumes and the acting and we were informed that the drama received ‘the warmest applause from a crowded audience’. The following day’s issue continued its high praise of the production with a paean to the acting of Charles Kemble (who played the title role) and Mrs Sloman (Madame Dorival). The death of Madame Dorival at the end saw the audience hiss Kemble ‘as if the scene were real’. All in all, the writer believed that the play’s merits, the ‘splendour’ of its production, and the acting all meant that the play ‘must be popular’. The issue for 27 February advocates strongly for the play’s morality by way of response to violent press attacks against it on those grounds.

Other supportive reviews may be found in The Examiner (19 February 1826), and the Monthly Magazine (March 1826) despite it being ‘French all over—French in its characters—French in the large proportion which dialogue bears to incident—French in the length of the speeches […] and French, too, in a very anxious regard to the unity of place’ (307). The London Magazine (March 1826) was not impressed nor was The Observer (13 February) which, while admitting that it was well applauded and thought it likely to have a strong run, also concluded that the insofar as the ‘real claims of the Drama’ were concerned ‘they are far from being of a high order’. However, it is—not unsurprisingly—The Times which dealt the most excoriating critical blow.

The review in The Times (13 February 1826) begins by nominating Payne’s effort as ‘an extremely tiresome, vulgar, stupid, common-place description of [a] play’. The story is ‘slight’, the plot ‘single’, and the dialogue ‘very dull and incipid [sic]’. A sardonic and sniping plot synopsis follows and this is where the writer really hits his stride:

Now, to begin a play, which was to go on through five acts, with a woman so situated [i.e. ‘fallen’] for the leading character, would be, with the very best appliances, a measure of very questionable prudence; but, in The French Libertine, this revolting interest stands not merely a leading feature, but becomes absolutely all that the writer has to trust to; and it is carried forward with a perfect disregard of all those limits which decent taste and respectable feeling have been used to set to such discussions.

The review then argues that previous stage libertines—such as Lothario or Don Juan—have many redeeming character traits that render them fit for public consumption but Rougemont is a ‘senseless, heartless, contemptible, bragging coxcomb’. Kemble’s acting was weak (although that of Mrs Sloman is commended) and the denouement unsatisfactory but then we get to the reason for such a long and thorough assault on the drama:

For the play altogether, it would not have been worth giving ten lines of notice to, if it did not look like a sort of attempt at introducing a style of entertainment which we hope not to see endured in this country. A certain class of French novels are well known as living upon this unpleasant detail, of which The French Libertine is one of the paltriest specimens; but for Heaven’s sake let us have none of it, upon any terms, brought to market in England […] Let us have English feeling, and English hearts, if we cannot always have that which is very recherché or entertaining; English anger, and English punishment, for that which is villainous; and English contempt for all that is ridiculous or base.

This angry jingoistic flourish brings us towards a conclusion which insists—despite the testimony of the other reviews—that Kemble received ‘loud and heavy’ disapprobation from the audience when he announced another performance.

The published version was dedicated to Washington Irving. The play was later adapted by Catherine Farren and frequently played as The Bankrupt’s Wife in America.

Commentary

The original manuscript (Ad Mss 42875) contains a number of emendations in pencil. These indicate passages or phrases to be deleted are underlined, boxed or marked with squiggles in the margin. As the markings are different to those usually deployed by Colman, we might speculate with some confidence that Montrose went through the manuscript himself. The correspondence below supports this possibility. As one might imagine, the bulk of the deletions are related to the account of the rape in Act 1 and the subsequent references to this event. The detail is offered below but first it is worth reviewing the correspondence attached to the first manuscript version which offers us specific detail on the censorship process (the letters have been reordered chronologically) and that the problems were with the rape, the attack on the Richelieu family, and the suggestion that this was based on a true event.

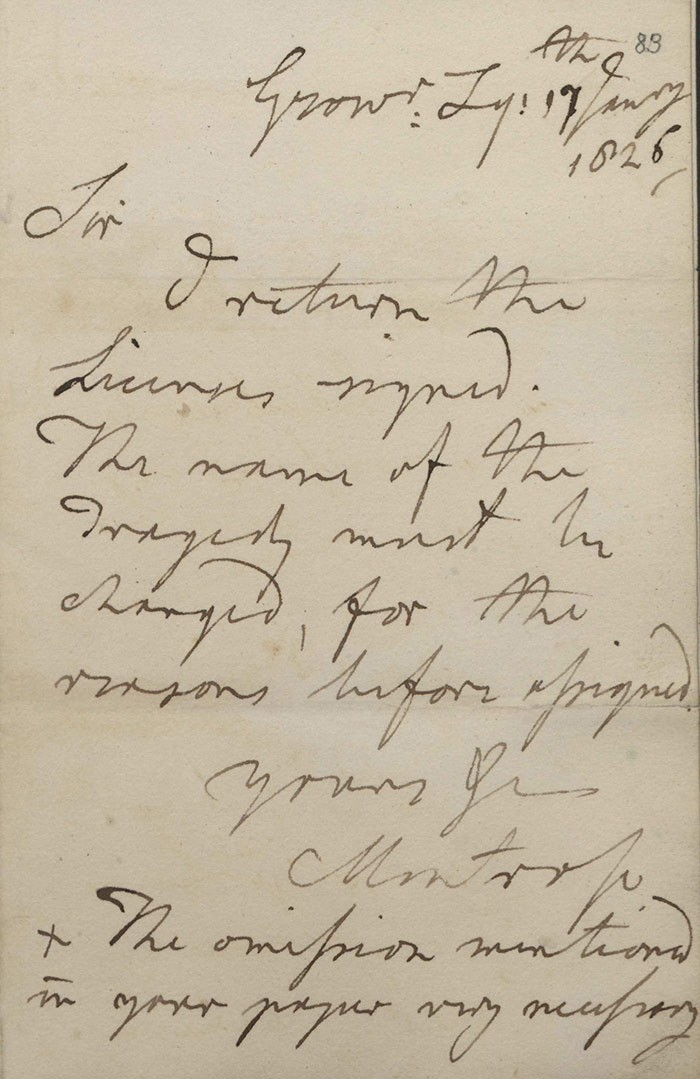

[Montrose to Colman, 20 December 1825; f.85r]

Sir

I see no occasion for desiring Mr Kemble to come here, I cannot License the Play, & so you may inform the Manager.

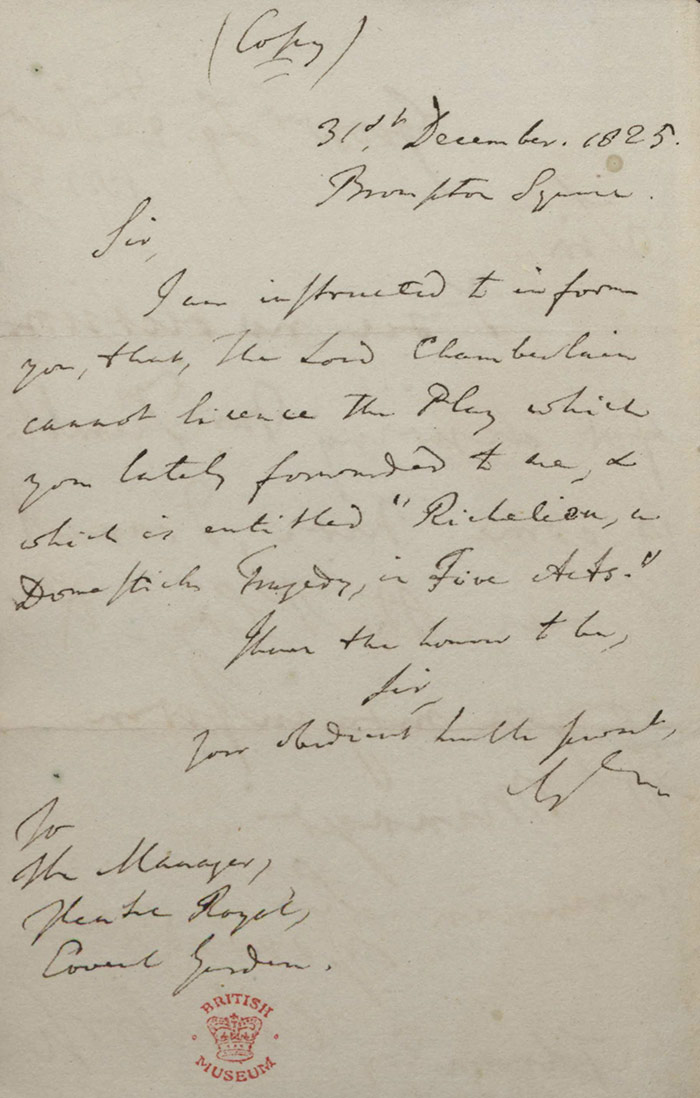

/[Colman to Kemble, 31 December 1825 (copy); f.85v]

Sir,

I am instructed to inform you, that, the Lord Chamberlain cannot licence the Play which you lately forwarded to me, & which is entitled “Richelieu, a Domestick Tragedy, in Five Acts”.

[Montrose to Colman, 5 January 1826; f.82rv]

Sir

As to the Richelieu Play, I object to both name, & subject. Mr Kemble may bring you another play, which when seen you will form a judgment upon. I do not see how that Play can be amended! As to the Babington I fear I must see it also, before I can sign my name.[Kemble to Colman, 9 January 1826; f.84r]

My dear Mr Colman

I have, at the suggestion of the Duke of Montrose, who honoured me the other day with an interview upon the subject of “Richelieu” made many alterations in the Piece; and expunged, as I believe, every passage that could be considered exceptionable – will you oblige me by re-perusing it at your very earliest leisure and in the event of your approval of it in its amended form, procure the licence from his Grace.[Montrose to Colman, 12 January 1826; f.81rv]

I return Mr Kemble’s Note. The foundation of the Tragedy must be changed, as well as exceptionable passages expunged; but you understand my feeling on the subject, & there /must be no libel on a Noble Family, whether the fact may have been true, or false.[Montrose to Colman, 17 January 1826; f.83r]

Sir

I return the Licenses signed. The name of the Tragedy must be changed, for the reasons before assigned.

Yours etc

Montrose

X The omission mentioned in your paper very necessary

We can also add the letter attached to the second manuscript (Ad Mss 42876) to complete the known correspondence on this play.

[Colman to Kemble, 24 January 1826; f.38r)

Sir,

In reference to your M.S. ^now entitled “The French Libertine”, you, of course, recollect that the Lord Chamberlain has uniformly revolted against the incident of violating a Female in a Swoon; &, also, against libelling an existing Family. It does not quite appear that you have been [illeg] to remove his Graces objections as to escape them. His Graces objections are not thoroughly removed by your present alterations. I am instructed, therefore, to propose to you, as follows: - Omit, after the Title of your play, The French Libertine, the words “Founded on Fact.” Omit the proposed words “I sank exhausted”

Give the Duke of your Dramatic Personae / a [decided] , & fictitious appellation, - such as “Rougemont,” for instance, which you, yourself, have suggested.

When you have acquiesced in the above propositions, the Play, as I understand His Grace, will be licenced.

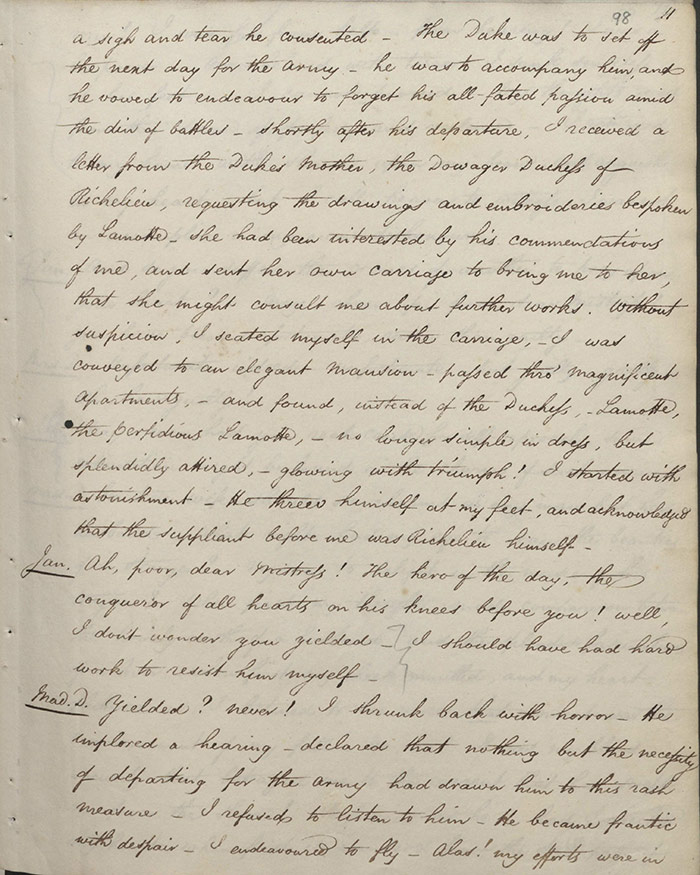

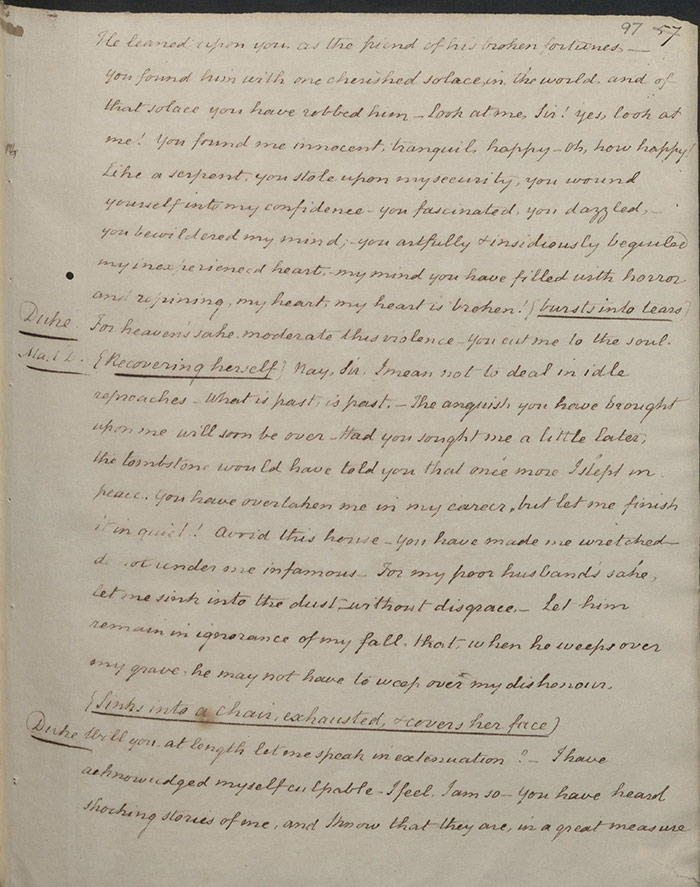

The crucial passage insofar as the question of censorship is concerned is Madame Dorival’s admission of having been raped in the first act:

JANET: […] well, I don’t wonder you yielded – I should have had hard work to resist him myself -

MADAME DORIVAL: Yielded? never! I shrunk back with horror – He implored a hearing – declared that nothing but the necessity of departing for the army had drawn him to this rash measure – I refused to listen to him – He became frantic with despair – I endeavoured to fly – Alas! my efforts were in / vain! I was far from help – from hearing! I was in his power – Overwhelmed with terror, I sunk senseless at his feet – I cannot proceed – my thoughts recoil from this scene of perfidy and violence – I returned to my home with shame upon my brow, and anguish in my heart – but I call heaven to witness – I was not an accomplice in my own dishonor –

JANET: And do you suffer the crimes of another to prey upon your heart? Nay, cheer up, poor, dear mistress! you have been unfortunate, rather than guilty –

MADAME DORIVAL.: Unfortunate indeed – unfortunate – but guilty – guilty – Oh, how guilty!

JANET: Nay, even had you real cause for self-reproach, some extenuation might be found in the charms of such a man – (ff.98r-99r)

The section of Madame Dorival’s speech beginning with ‘vain’ and ending with ‘anguish’ is all marked with a penciled squiggle in the margin. Moreover, all three of the worldy Janet’s speeches—where she downplays the magnitude of the rape —are also so marked. It is notable to the modern reader that Madame Dorival’s anguished guilt does not trouble the Examiner; the implication is that this is a correct moral response despite her lack of complicity, not to mention consent. We can turn now to the rewritten version of this scene to see how Payne blurred the reference to the violent attack:

MADAME DORIVAL: I shrunk back with horror – He implored a hearing – declared, that nothing but the necessity of / departing for the army, had impelled him to this rash measure – I refused to listen, and he became frantic with despair – I endeavored to fly – Alas! my efforts were in vain. I sank exhausted. I cannot proceed – I returned to my home, with shame upon my brow, and anguish in my heart –

JANET: Nay, cheer up, poor dear mistress! You have been indeed unfortunate. (ff.51r-52r)

As per Colman’s epistolary instruction of 24 January, Kemble had the brief phrase that physically described Madame Dorival ending up on the floor removed from the speech, thus rendering the rape entirely implicit. Equally, Janet’s earthy insistence that this was not a complete disaster has been replaced with pity.

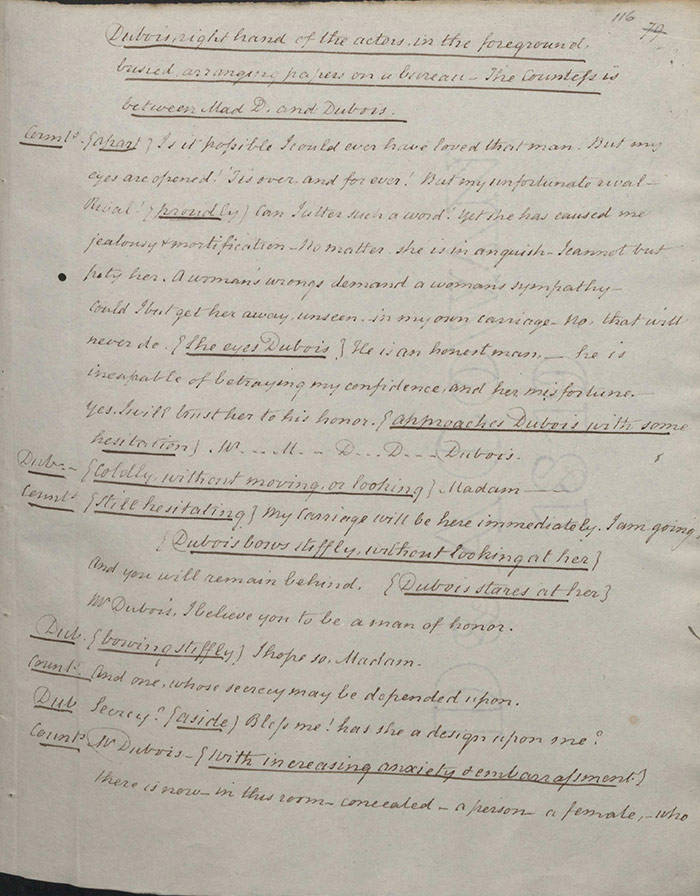

Other passages may be fruitfully compared and contrasted across the two manuscripts. Here Dubois is describing his new employer to the Dorivals; from ‘eclipse’ onwards the passage is marked with a squiggle in the margin, possibly indicating that it should be removed:

DUBOIS: That is to say, he knows he is a favorite with the public; - he cares not to restrain, or even hide his / faults, conscious that the brilliancy of his merit, will eclipse them. He is despotic in his temper, yet every body yields willingly to such commanding talents. The splendor of his genius, both in the Cabinet, and the field, secures to him the admiration of his equals, and the populace love him for his daring bravery, his manly grace, his winning affability; his open-handed magnificence; - and for the dashing spirit that gives a charm even to his faults –

(ff.103-104)

The comparable passage in the revised manuscript reads:

DUBOIS: Luck! luck! Accident introduced me to a patron, conspicuous for his rank, his credit at Court, his wealth, his munificence, and his gallantries – (f.55r)

The contrast between these two passages invites considerable speculation as regards Colman’s objections and Payne/Kemble’s response. The first thing to say is that the passage is considerably briefer so the fervour of the initial description is toned down considerably. The substitution of ‘court’ for ‘cabinet’ is also striking, perhaps the Examiner was more comfortable with linking corruption with the more typically referenced aristocratic arena in literary culture than the cabinet, closer to the practical exercise of political power in the 1820s. The revised version also dampens considerably our sense of the Duke operating within the nexus of political power, influencing his peers as well as deceiving the people. Notably, the reference to his military prowess is also passed over in the second version. Of course, we also have to acknowledge that the squiggle may simply indicate that Colman or Montrose believed this passage contributed to the negative depiction of the Richelieu name; thus, the renaming of the character did much to mitigate the initial transgression so it did not need to be deleted in its entirety.

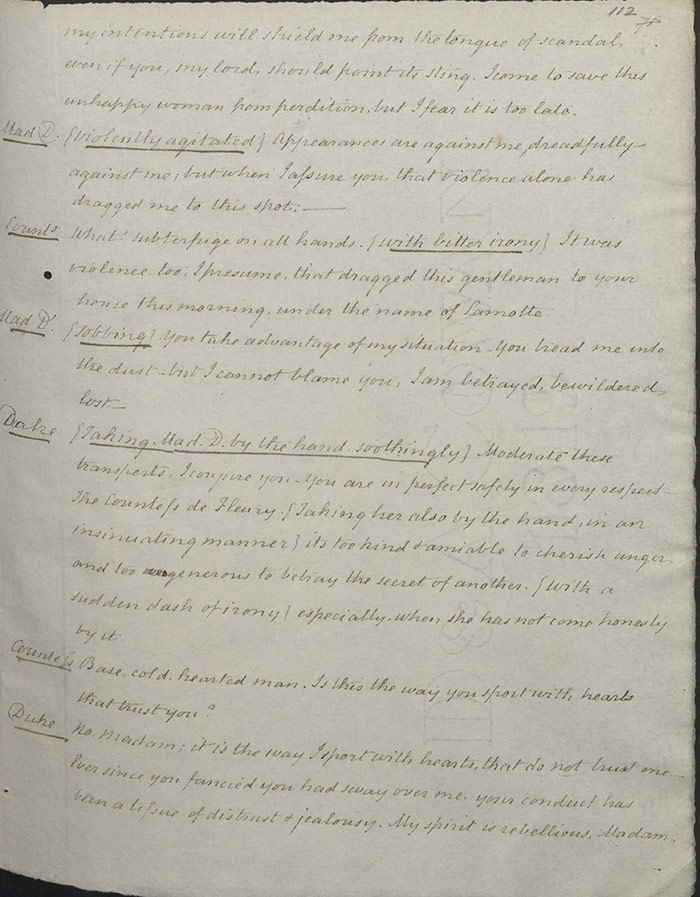

Further explicit references to the rape are also marked for deletion or rewriting (f.111) (f.153) as are admissions or references to Richelieu’s pernicious character (f.113), (f.114), (f.128), (f.155). Colman seemed particularly exercised by the Duke dictating a letter to Lamotte to ensure the dismissal of a man whose honesty was inhibiting his schemes: the relevant passages can be seen on (ff.117-118) and large penciled Xs are used to excise it. Equally, Colman wanted a duplicitous letter to the Countess Fleury removed (f.119). The Examiner was also not keen on any suggestions that the nobility were contemptuous of the ‘vulgar’: see (f.116) (f.129)(f.177) (f.178) by way of example. As per Colman’s usual practice, biblical references and religious language are also marked out e.g. (f.96) and (f.101).

The second manuscript, as we might expect, is much less marred by Colman’s pen. As we have seen he wanted a sentence removed from Madame Dorival’s account of her rape. The second manuscript also has ‘founded in fact’ scored out on (f.37) as per Colman’s letter. The real interest in the second manuscript though is in the careful reading of how Payne reshaped the character of Rougemont—or at least the nature and expression of his malevolence—in response to the heavy censorship of the original version.

Further reading

Frederick Burwick, Romantic Drama: Acting and Reacting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009),p. 53.

Rosa Pendleton Chiles, ‘John Howard Payne: American Poet, Actor, Playwright, Consul and the Author of “Home, Sweet Home”’ Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington D.C. 31/32 (1930), 209-297.

Edward Fiorelli, ‘John Howard Payne’, Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia (2019)

[accessed through Research Starters in EBSCO Discovery Service database]

Gabriel Harrison, The Life and Writing of John Howard Payne (Albany, New York: Joel Munsell, 1875)

[available on archive.org]

John Howard Payne, Richelieu: A Domestic Tragedy Founded on Fact (New York: E. M. Murden, 1826)