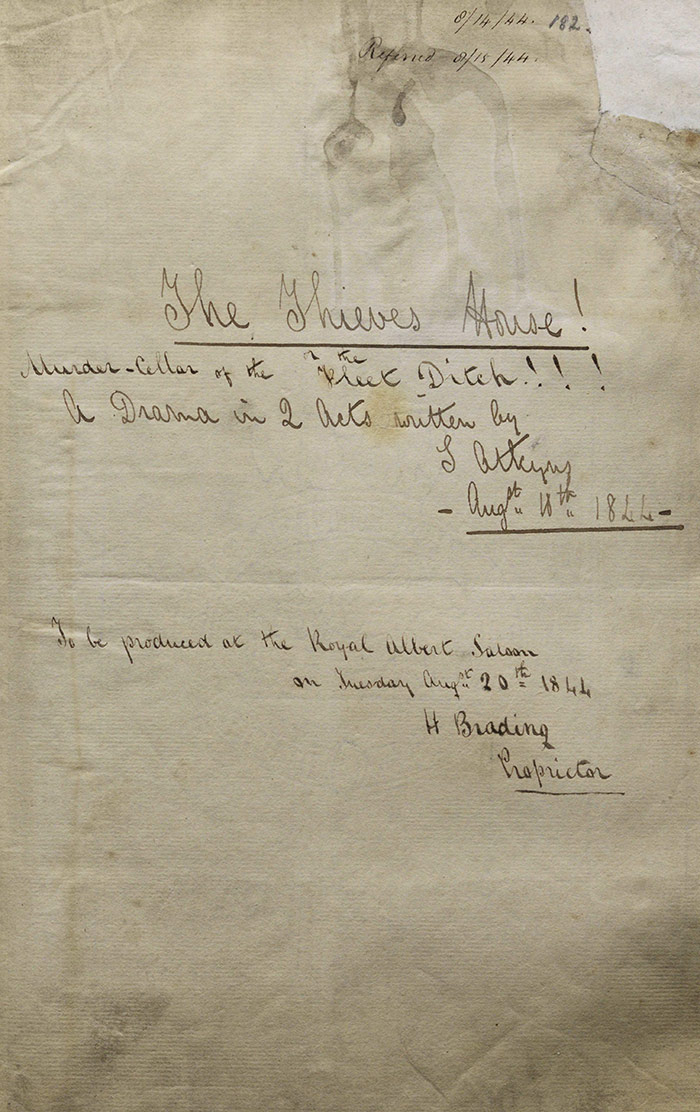

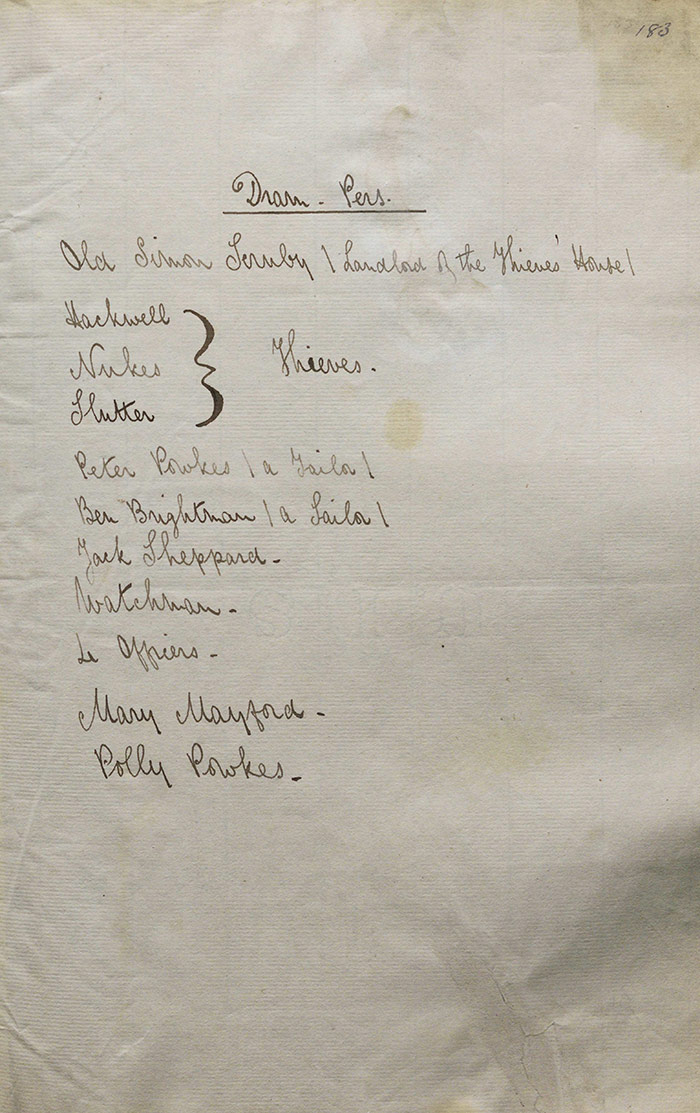

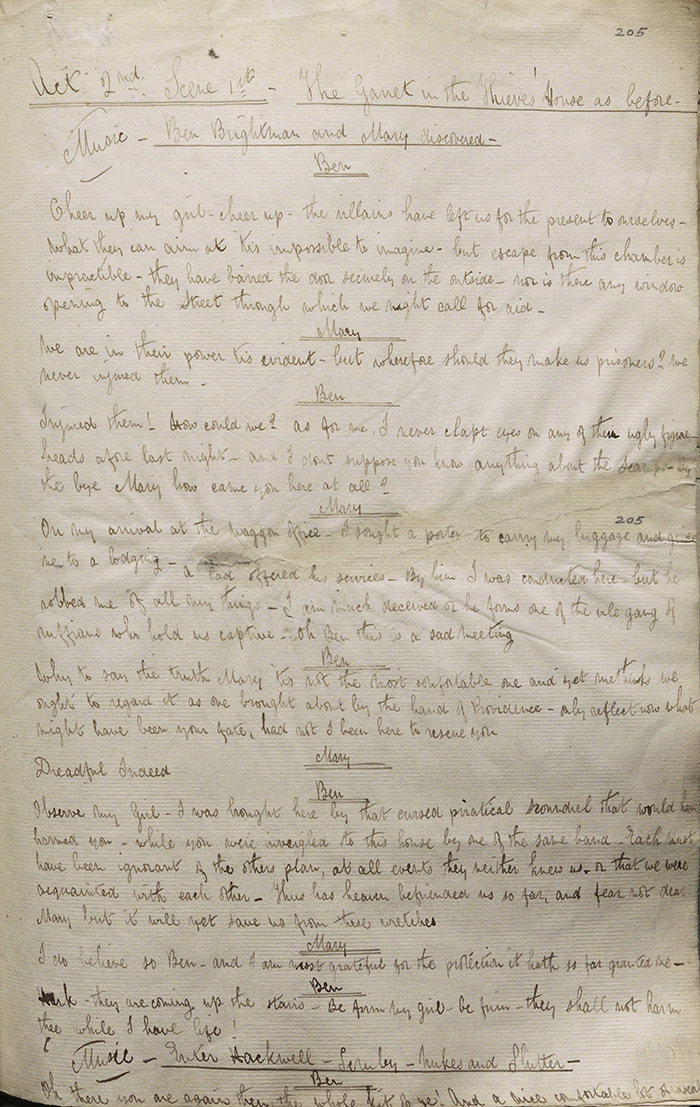

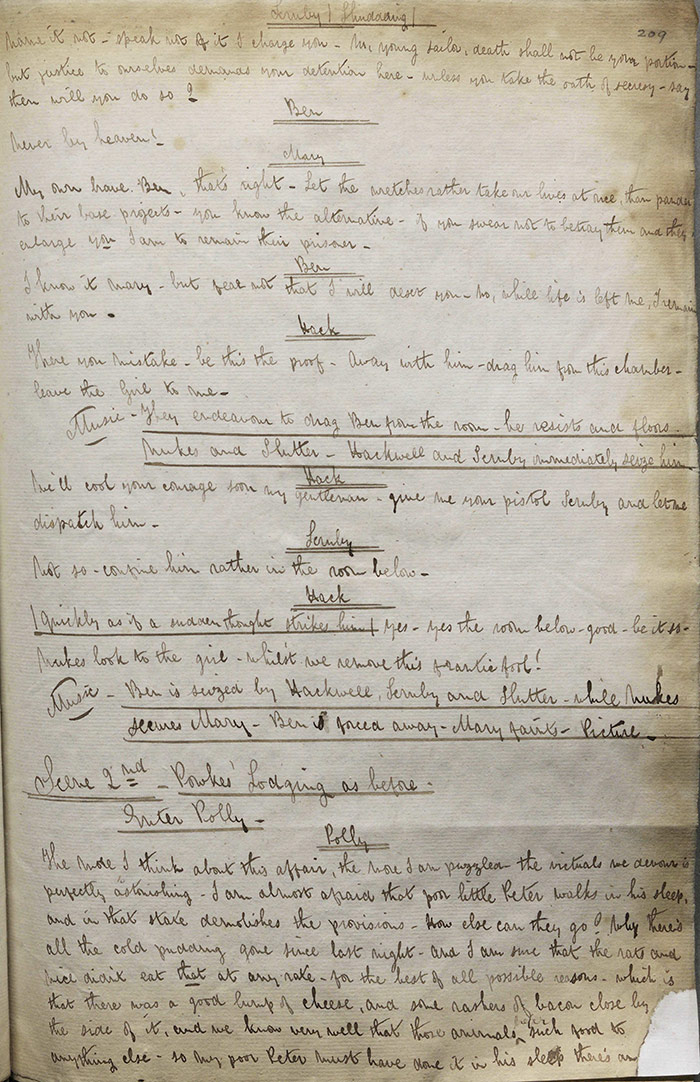

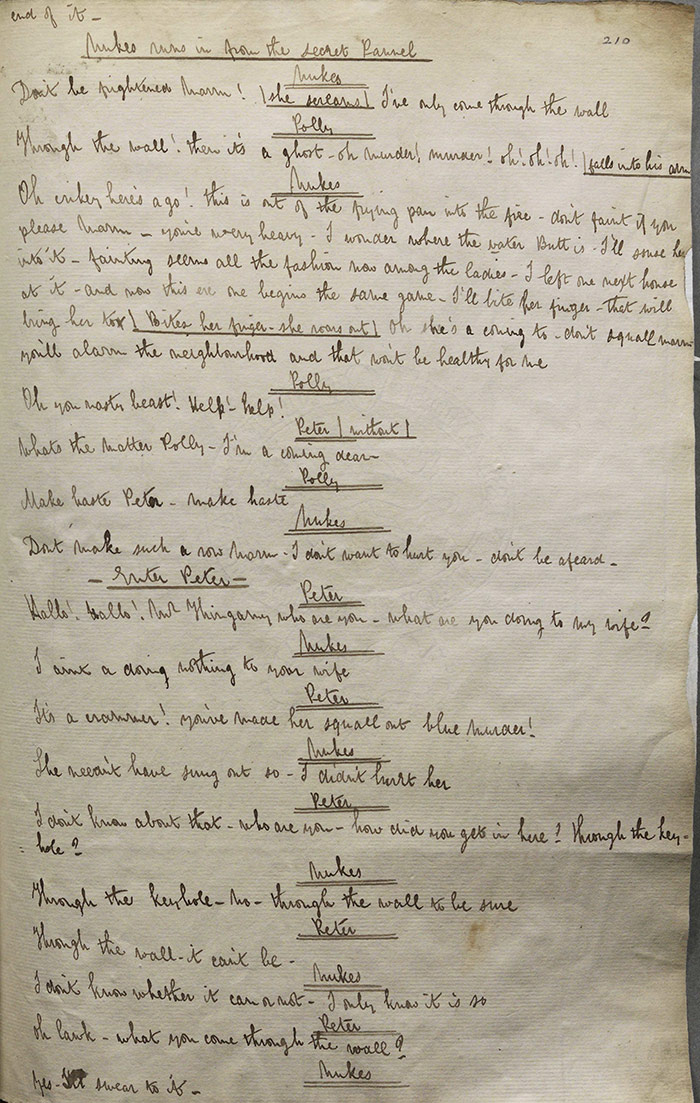

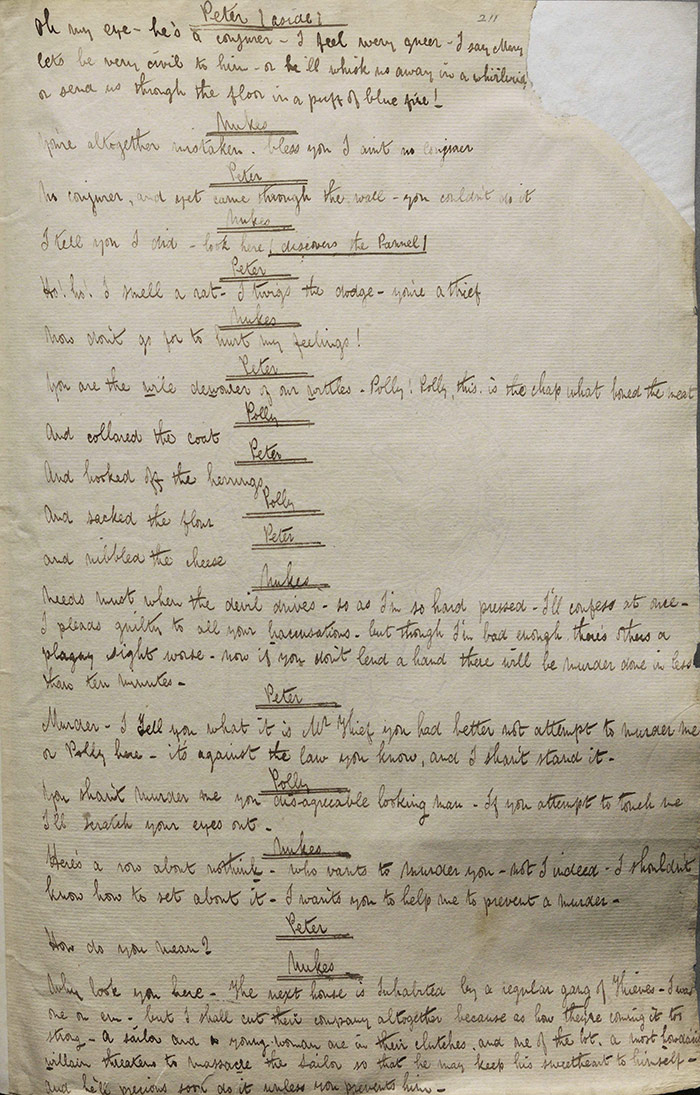

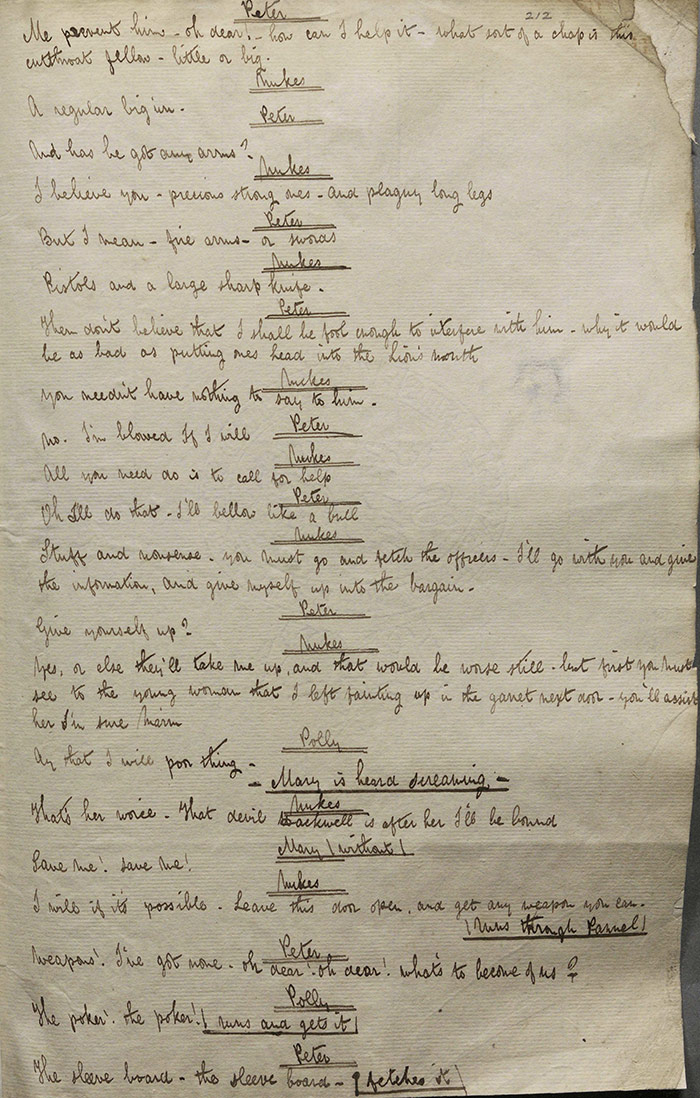

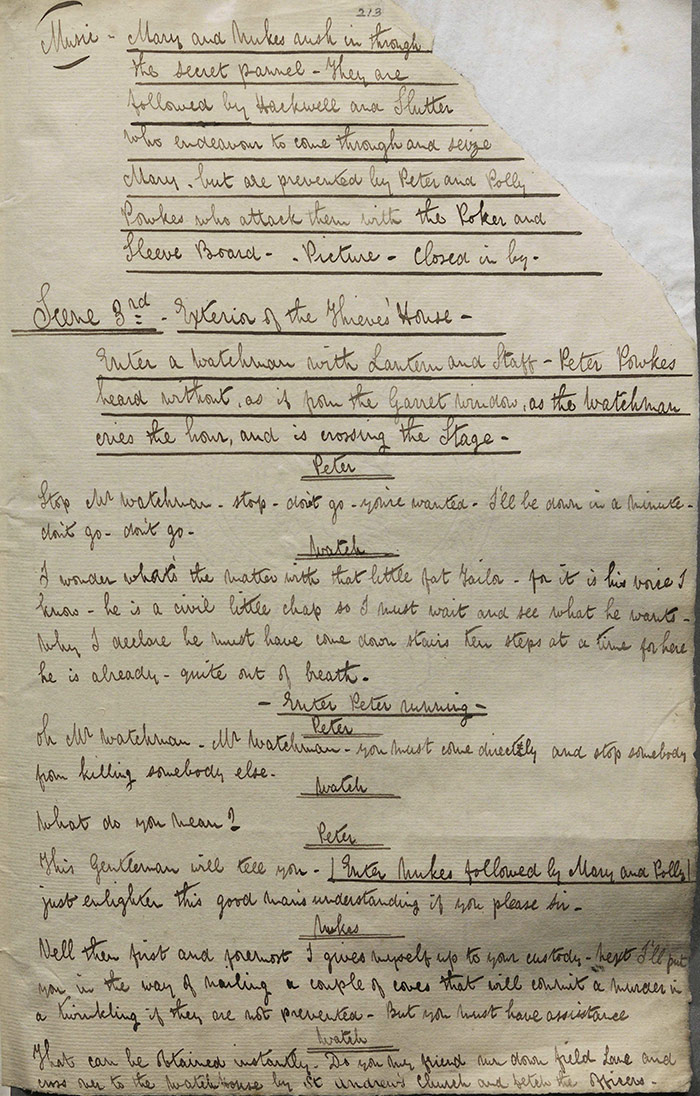

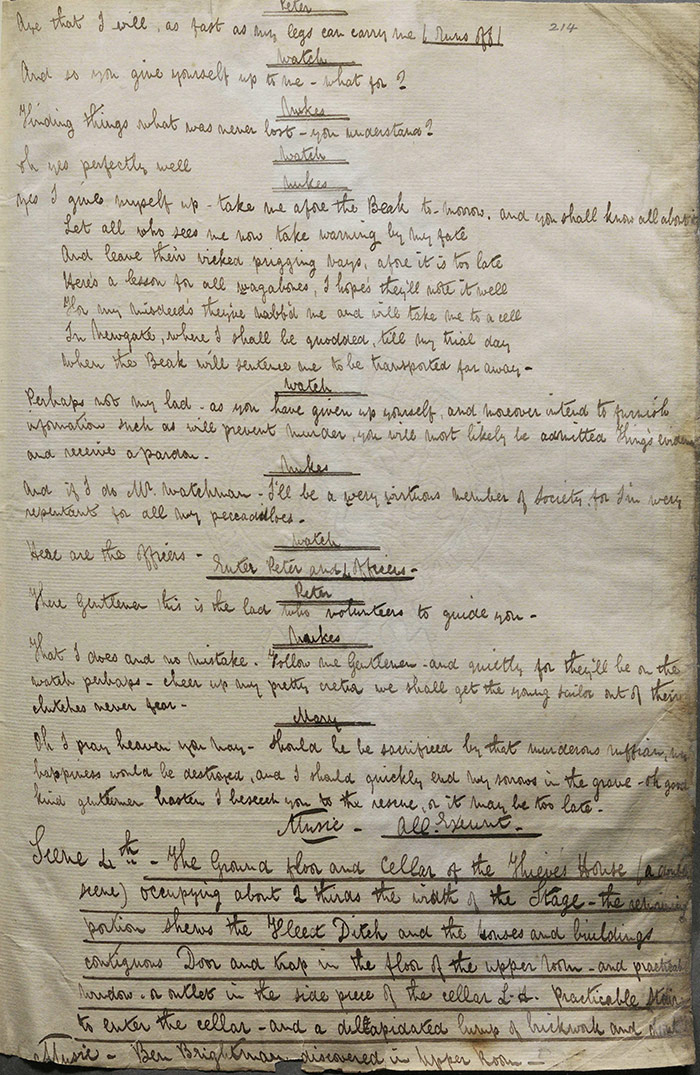

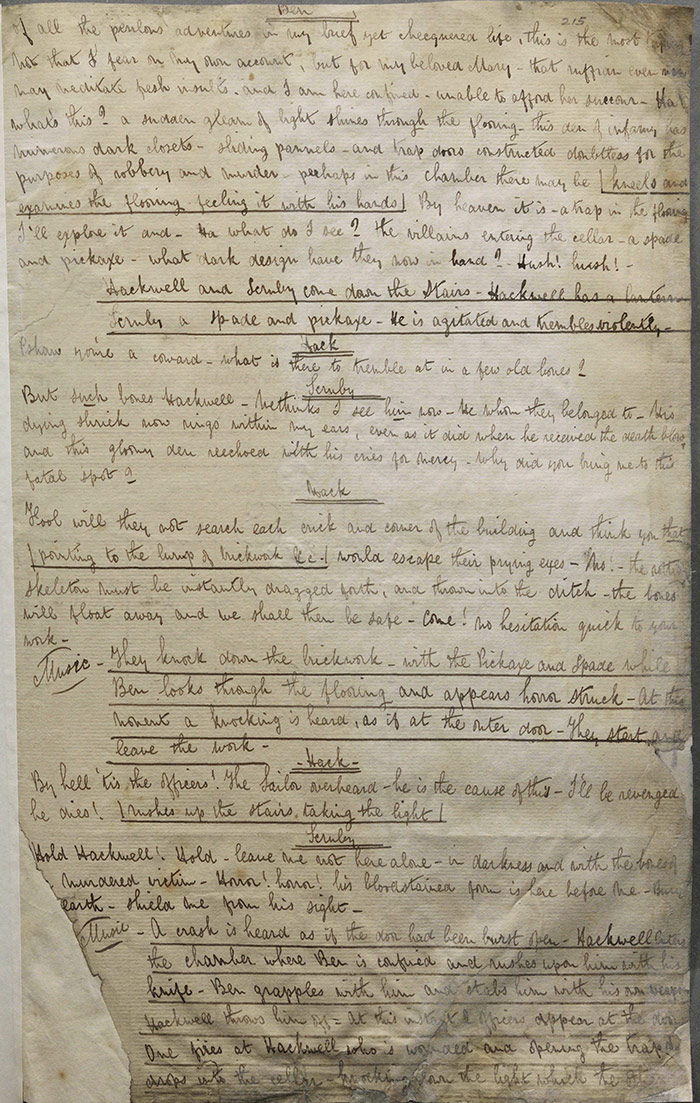

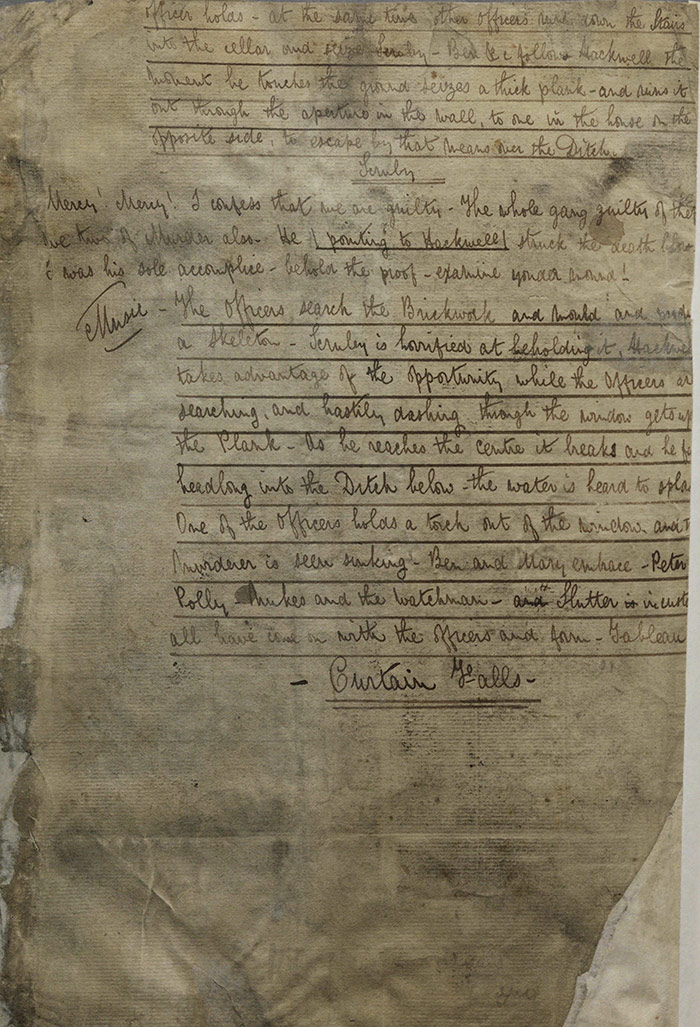

The Thieves House!; or, The Murder-Cellar of the Fleet Ditch!!! (1844) BL ADD MSS 42977, ff. 182-215

Author

Samuel Atykns (fl.1844-50)

Atkyns was an actor and dramatist but there is little readily available biographical information on him. He was author of Rookwood, or, The Tree of Fate [1845] which features Dick Turpin and this play, like The Thieves House!, was based on a William Harrison Ainsworth novel Rookwood (1834). See also Guido Fawkes (1840) for another play in this resource based on an Ainsworth novel. Atkyns was also manager of a theatre in Teignmouth, Devon, in 1851.

Plot

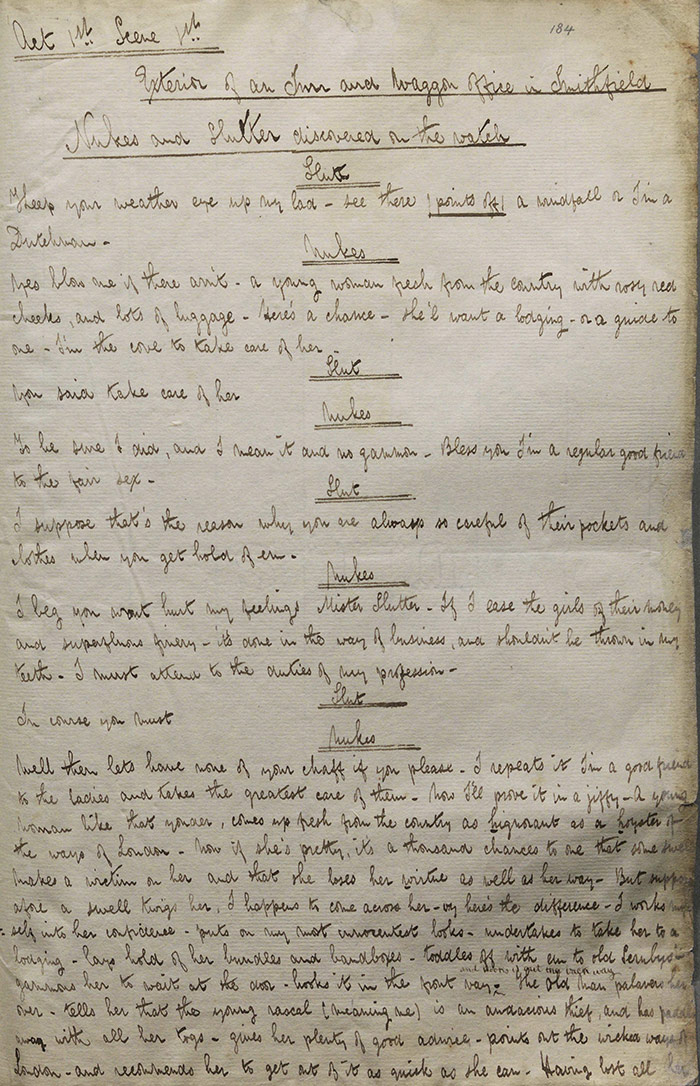

Act 1

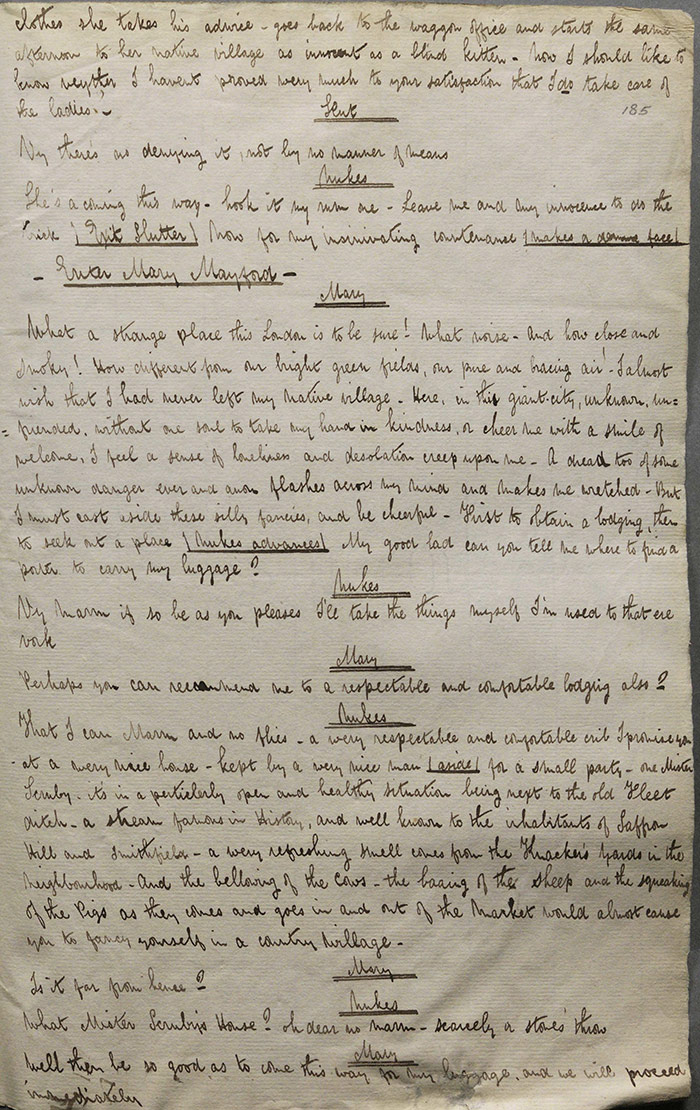

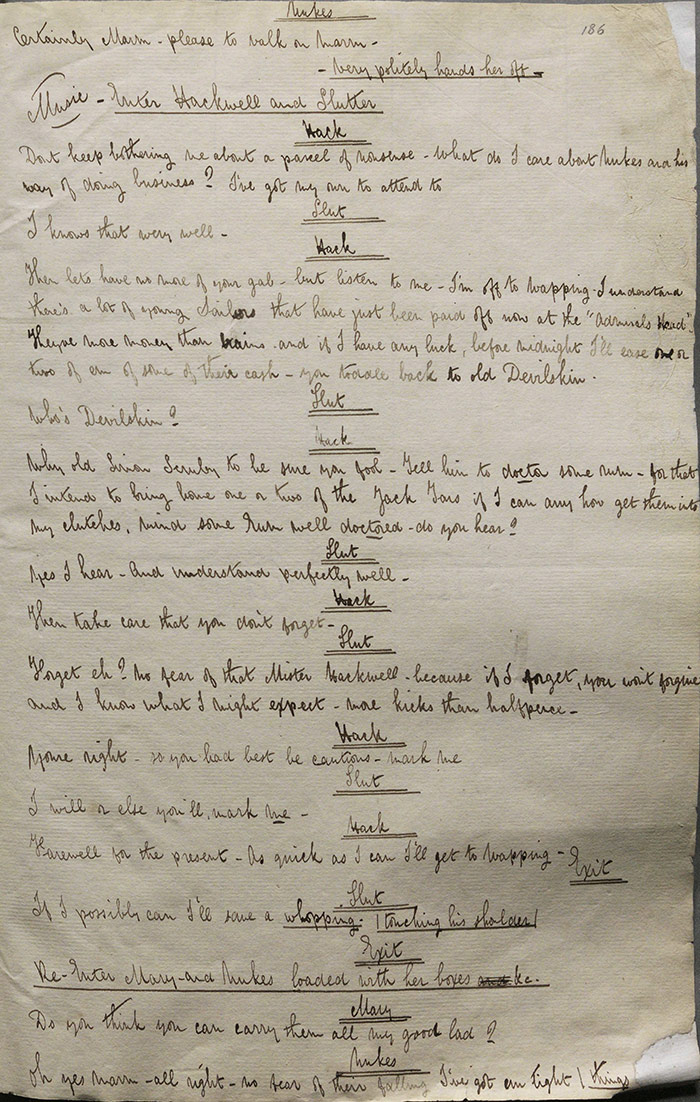

In Smithfield, thieves Nukes and Flutter are outside the wagon office and on the watch for a suitable target. Mary, newly arrived to London, proves a tempting mark. Nukes offers to carry her bags and bring her to an appropriate lodging. She agrees and he leads her off to Simon Sernby’s house next to the Fleet-ditch. Meanwhile, Flutter has met another fellow thief, Hackwell, who is planning on targeting some sailors who have come ashore. He asks Flutter to tell Sernby to doctor some rum as he will aim to bring back one or two of them. Fearful of physical retribution, Flutter promises not to forget. Nukes carries Mary’s boxes and she follows.

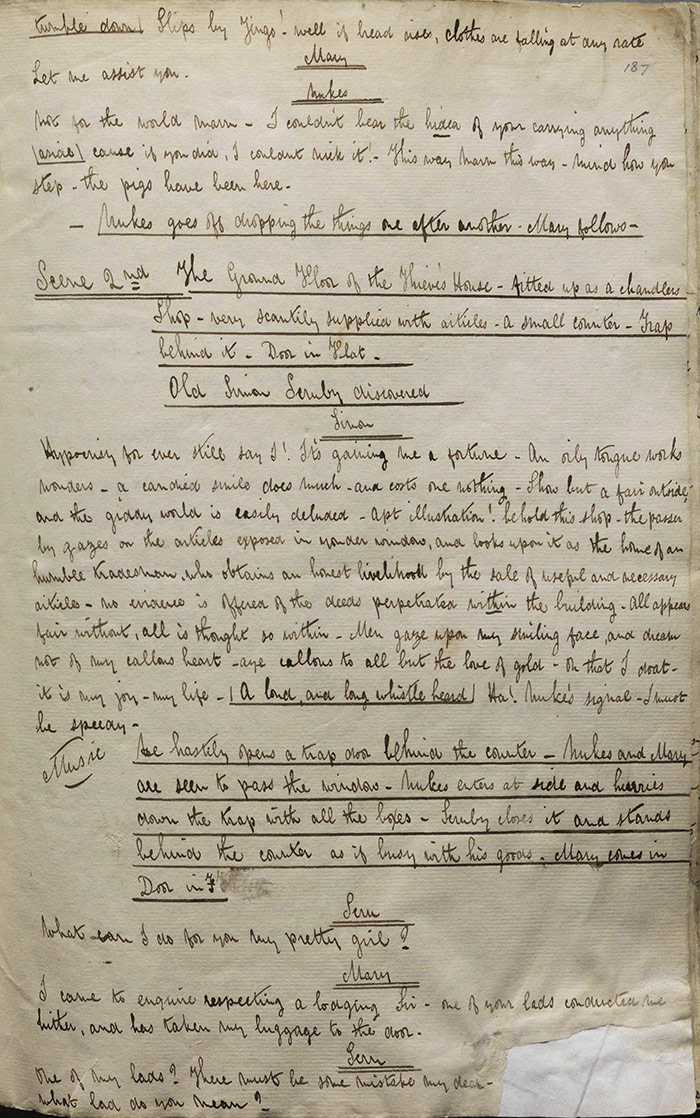

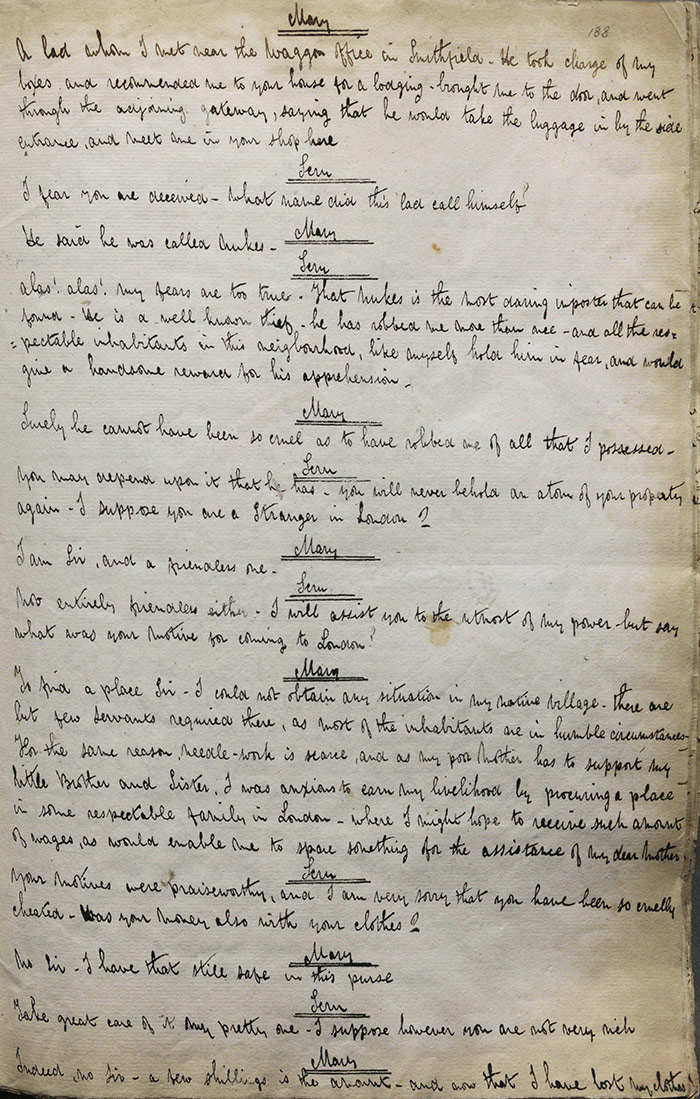

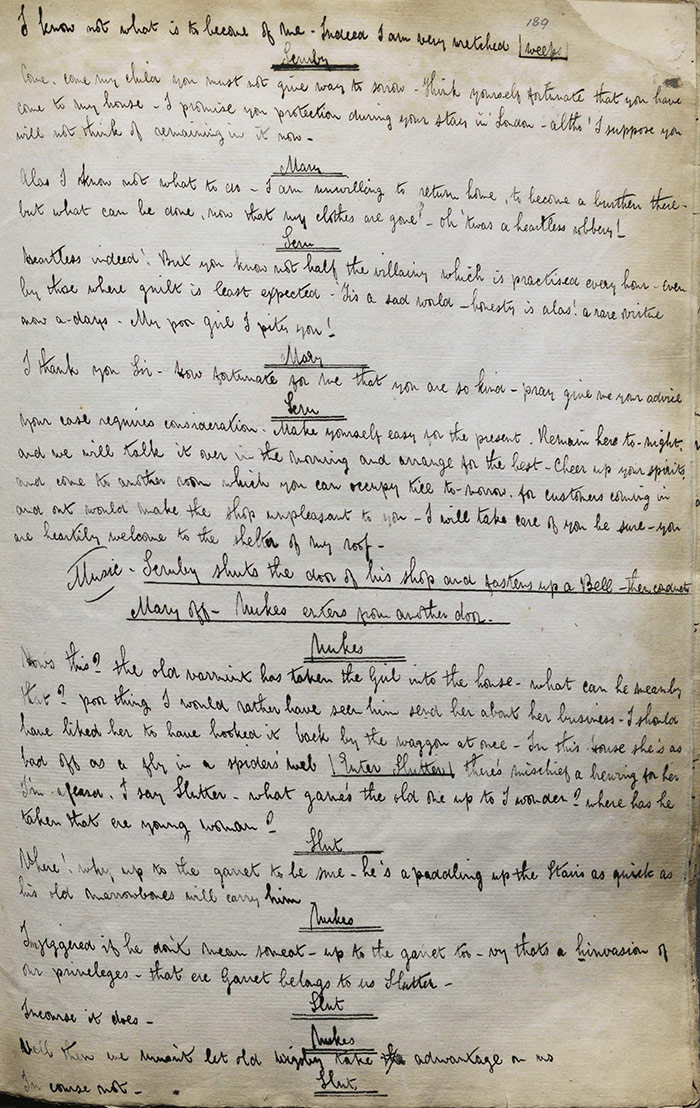

The second scene takes place in in the thieves’ house, fitted up as a chandler’s shop. Simon, alone, revels in the deceit of his shop and his love of gold. He hears a whistle and recognizes it as Nukes’s signal. He opens a trapdoor behind the counter. Nukes enters through a sidedoor and hurries down the trap with all Mary’s boxes. Sernby closes it after him and occupies himself behind the counter. She comes in the front door and tells Sernby that one of his boys has directed her here. He feigns ignorance and tells her that she has been duped by a notorious criminal. She is distraught, having come to London to help support her impoverished family. He soothes her and tells her to stay the night. He closes the shop door and leads her into the house. Nukes enters from another door, sees her being led off and expresses pity – he anticipates some dark deed by Sernby. Flutter appears and the pair decide to follow Sernby to see what he is up to.

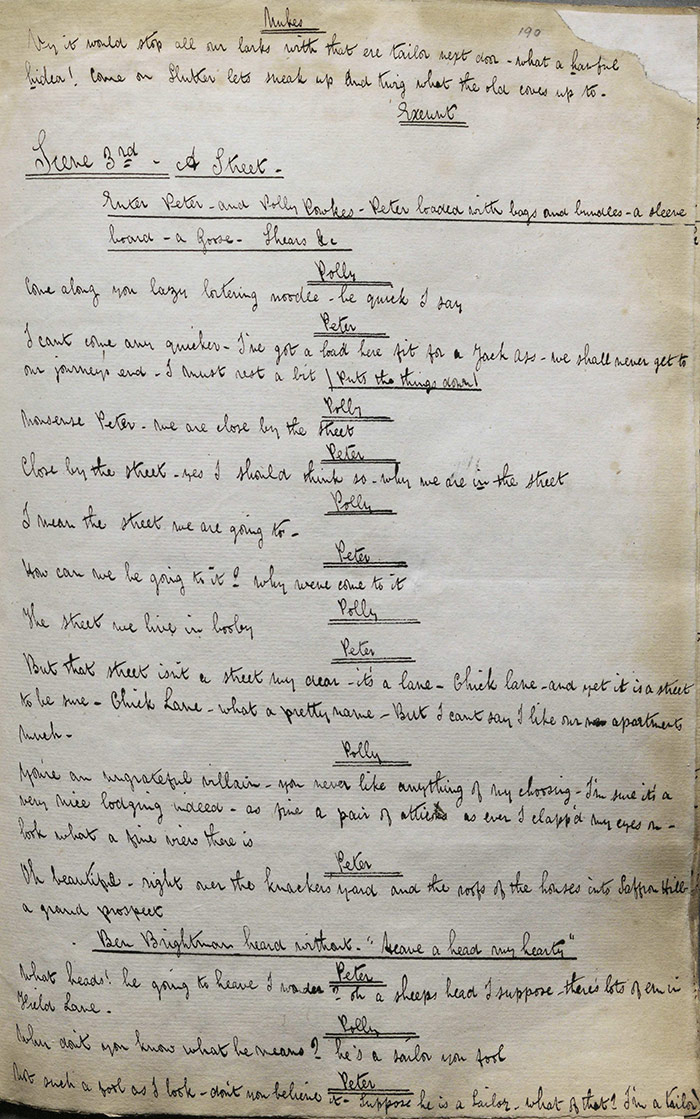

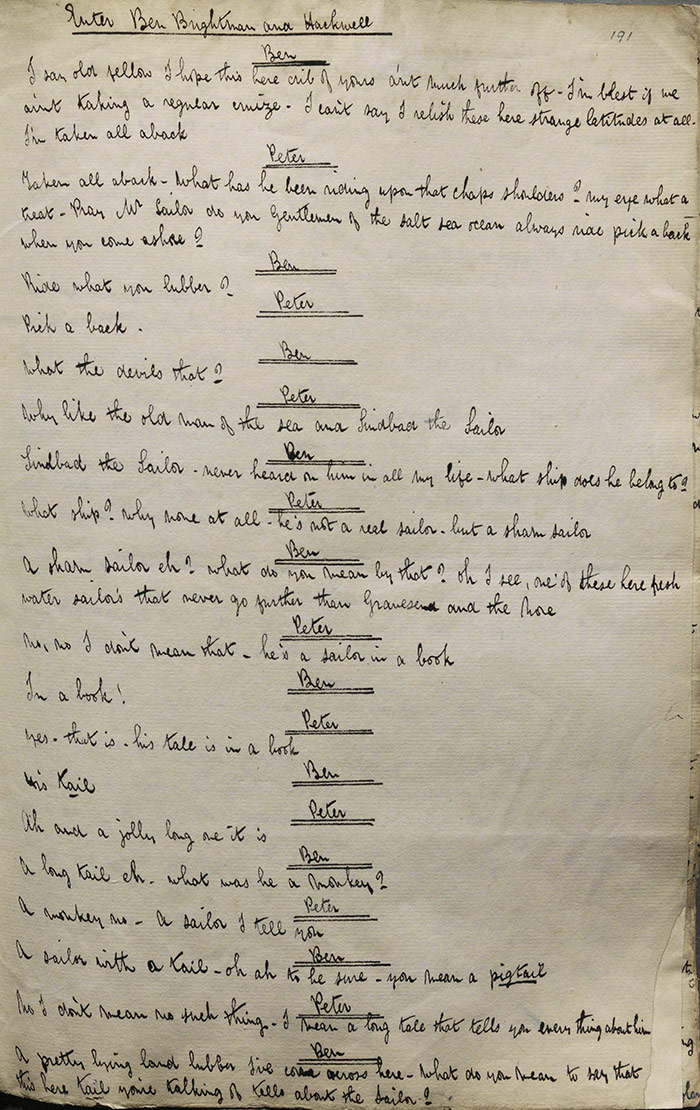

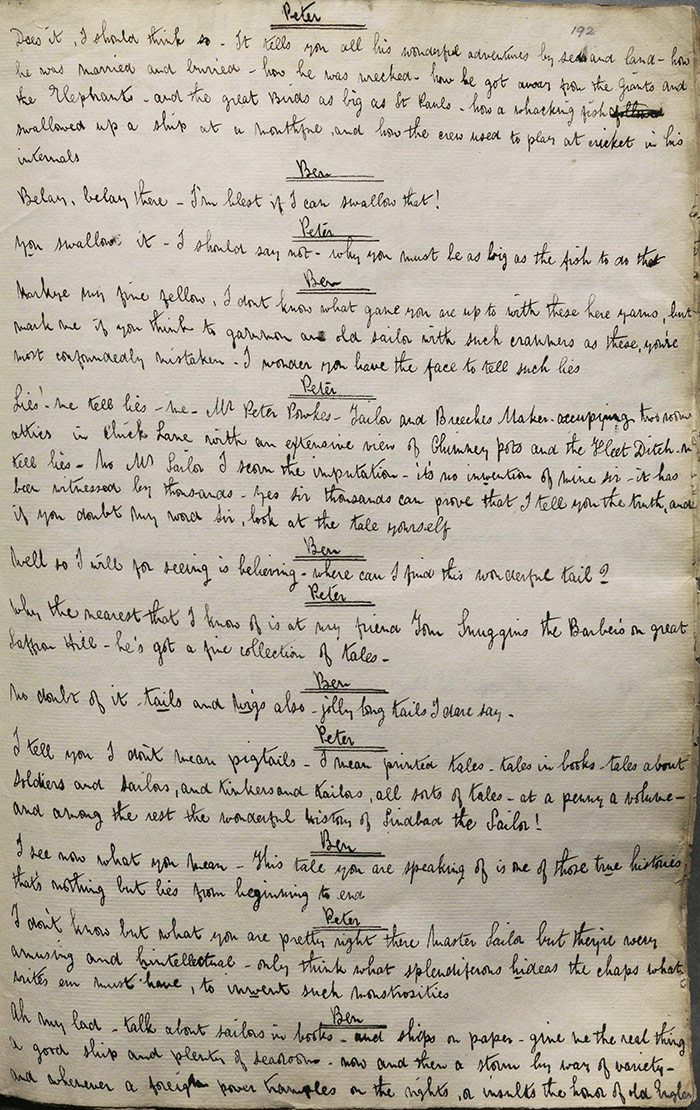

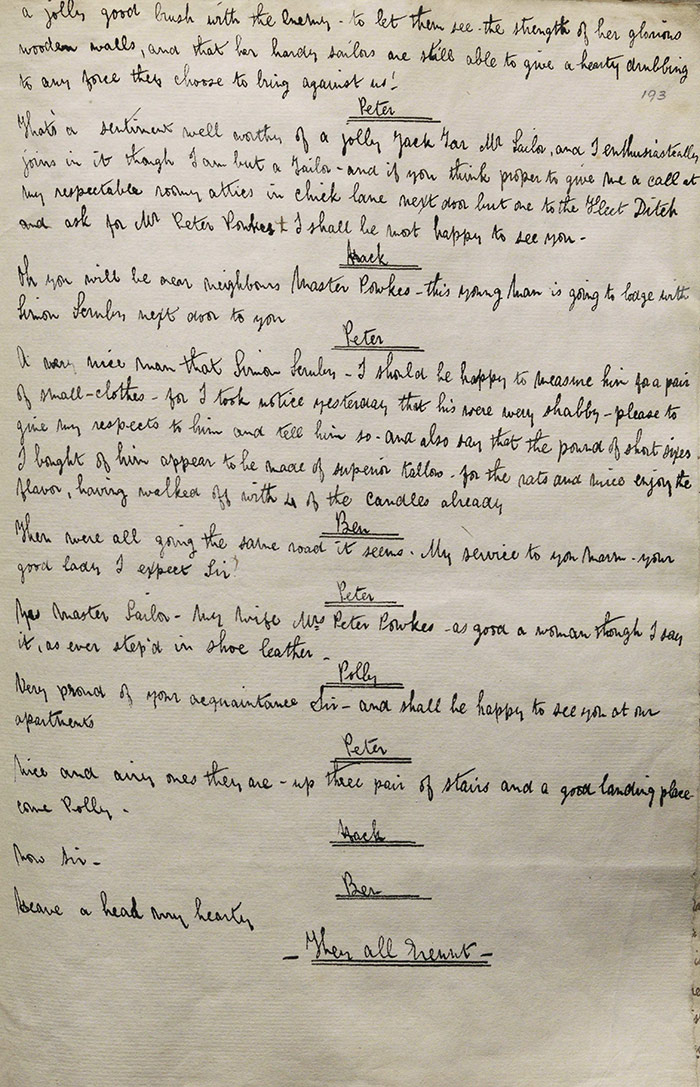

The third scene finds Peter and Polly Powkes on the street. They are moving lodgings to an attic in Chick Lane, a place overlooking and attached to Sernby’s. They hear Hackwell and Ben Brightman, a sailor, approach. Peter and Ben get involved in conversation and Hackwell tells Peter that Ben is lodging with Sernby. Ben praises Sernby and the quality of the tallow candles he produces. They all proceed companionably together to their destination.

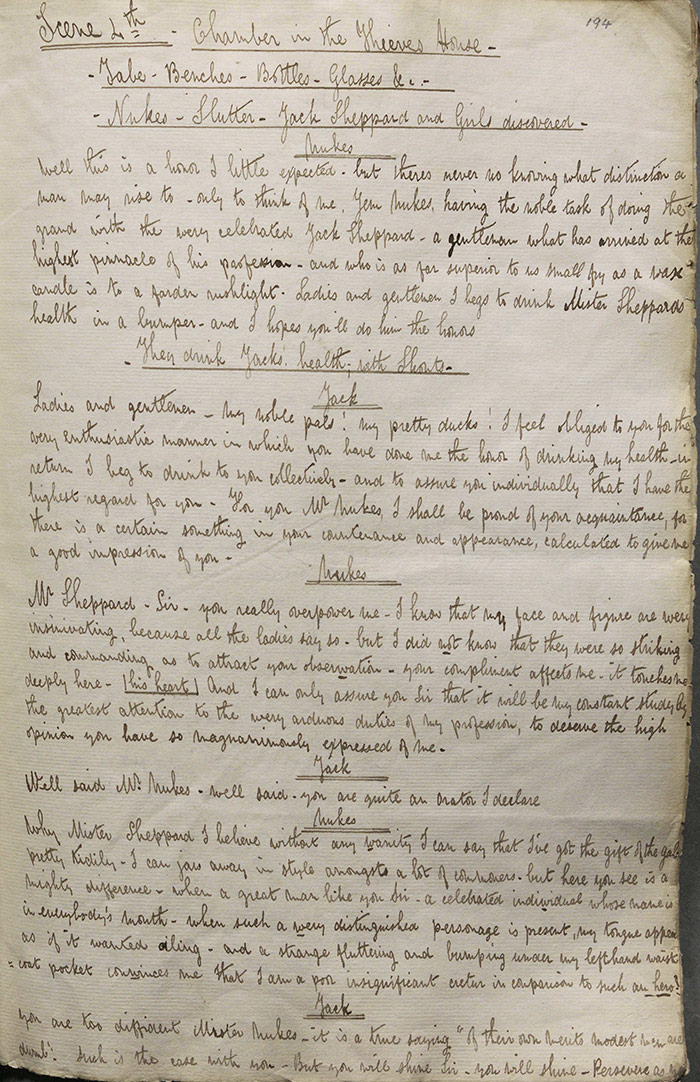

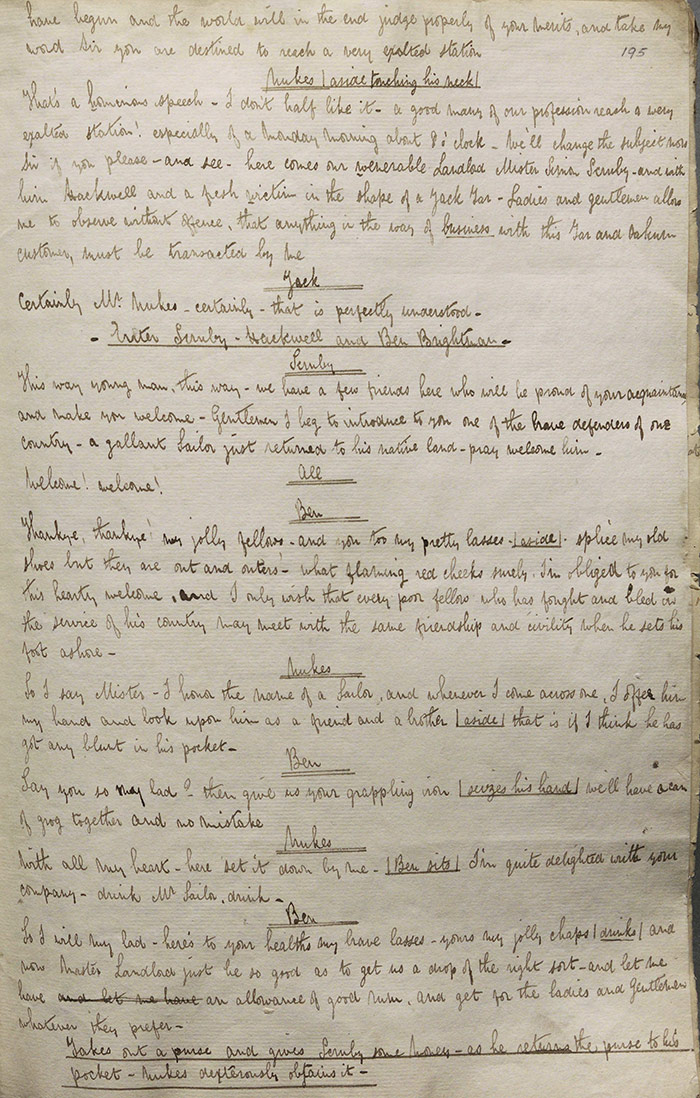

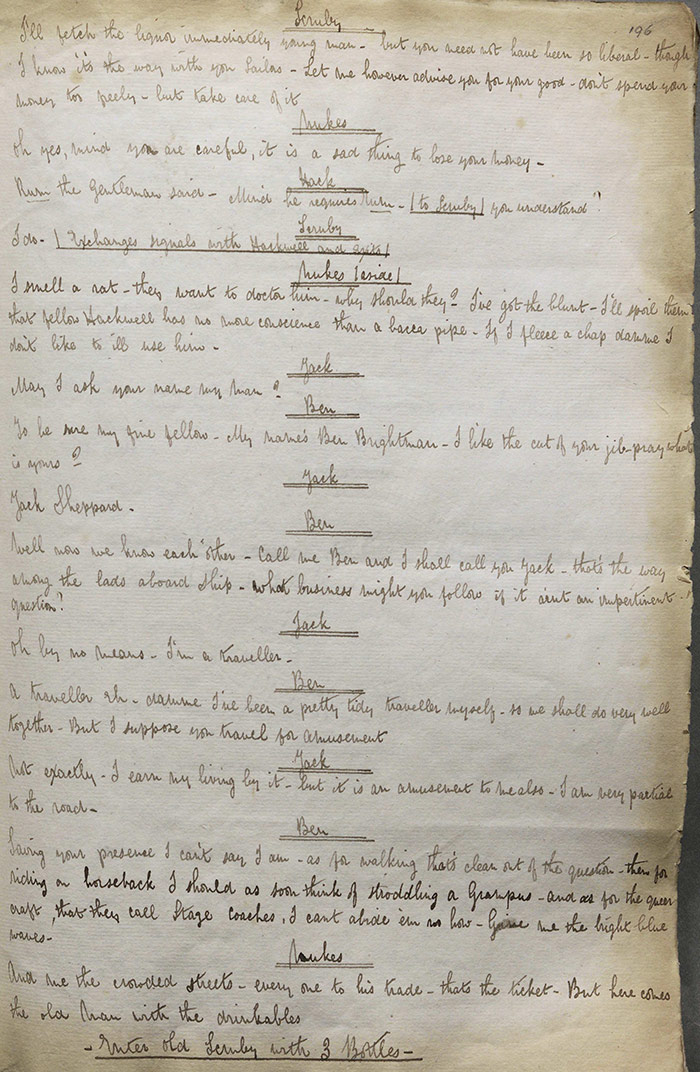

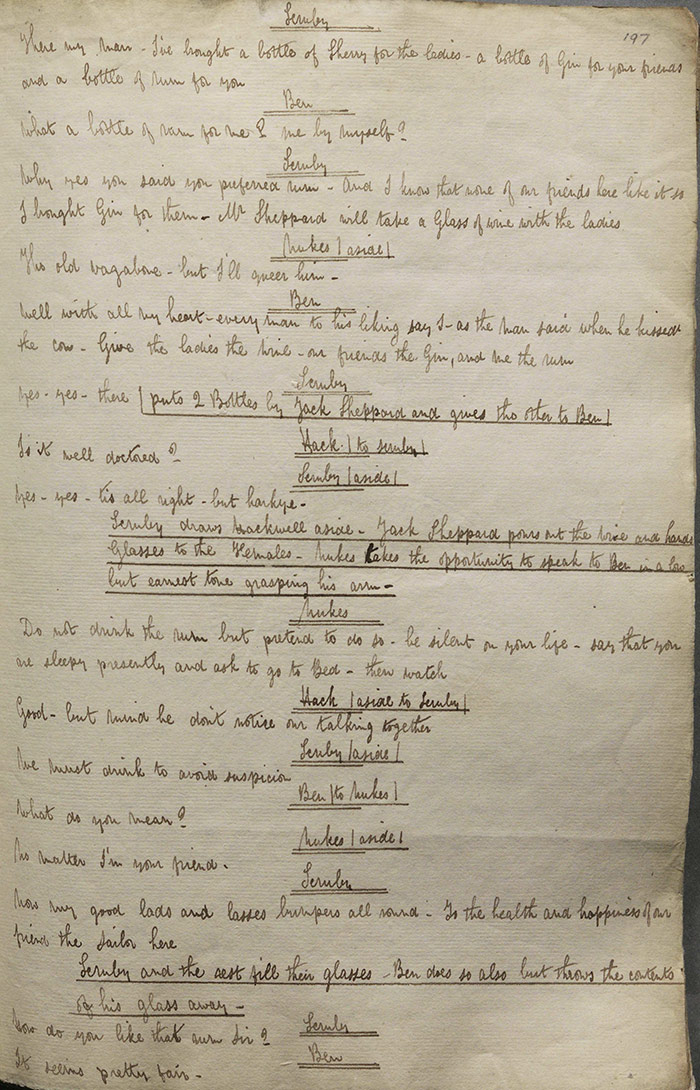

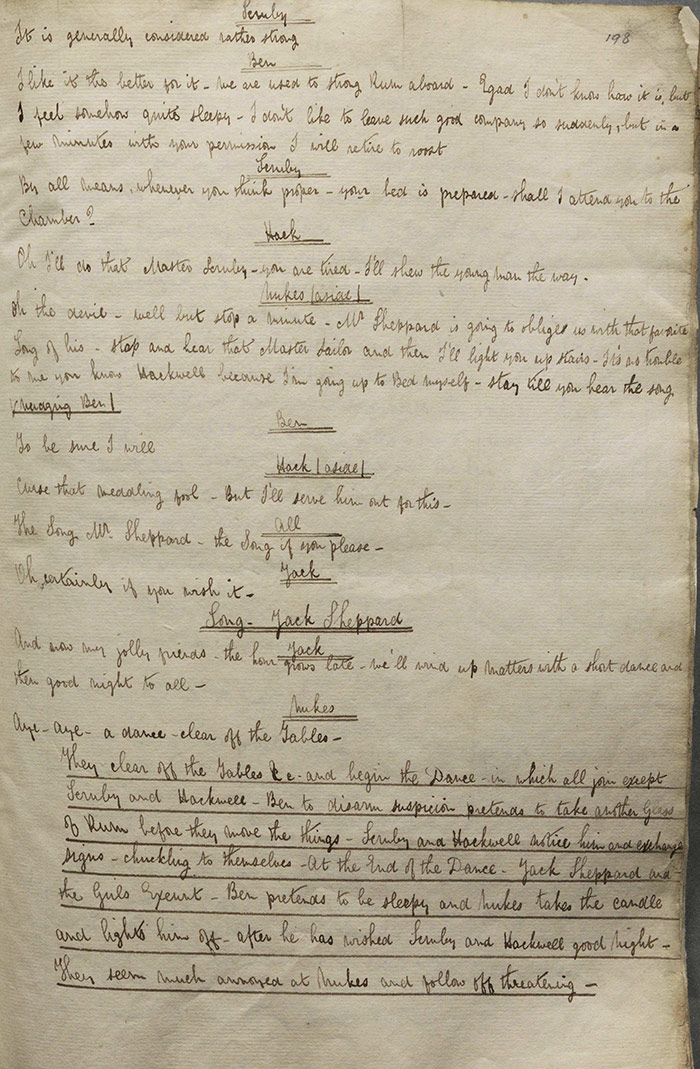

Jack Sheppard, Nukes, Flutter and some girls are discovered in the thieves’ house chamber at the opening of the fourth scene. Jack is holding court to his admirers, Nukes being chief among them. Sernby and Hackwell introduce Ben to the group. They welcome him, Ben buys a drink for them, and Nukes pickpockets his purse. Hackwell signals Sernby to get the drugged rum and Nukes determines to intervene, figuring stealing the man’s money is sufficient misfortune to deal him. When the drinks arrive, Hackwell and Sernby confer, giving Nukes an opportunity to warn Ben to pretend to drink, then say he’s sleepy and retire. He duly does so and Hackwell tries to escort him to bed but Nukes manoeuvres himself into that job, much to Hackwell’s annoyance.

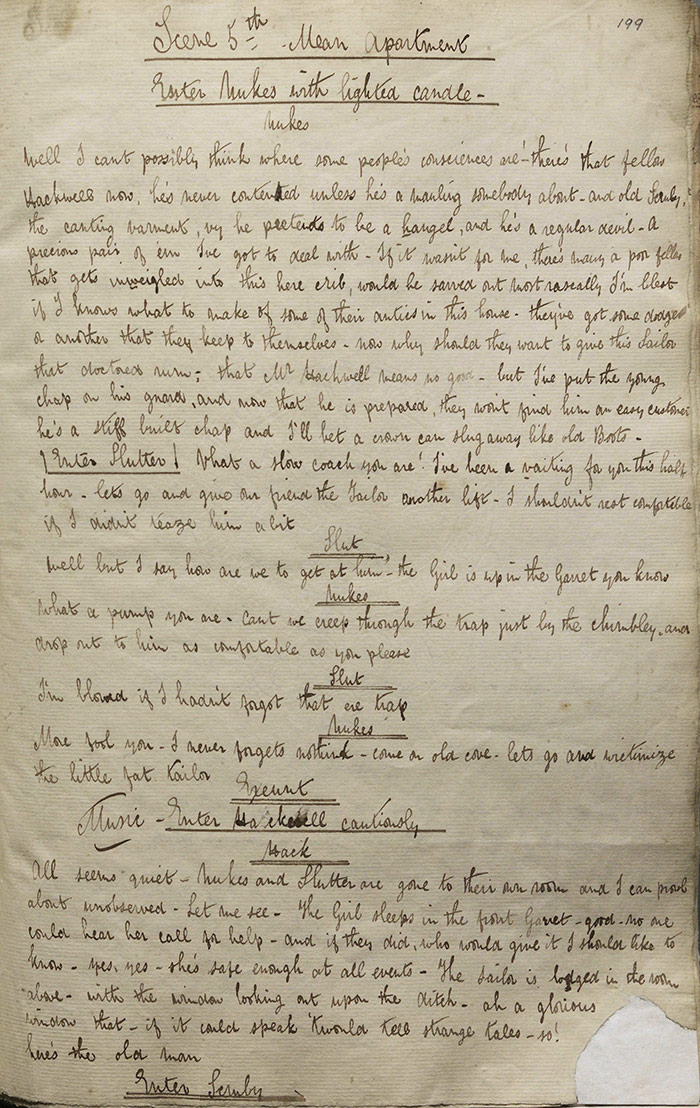

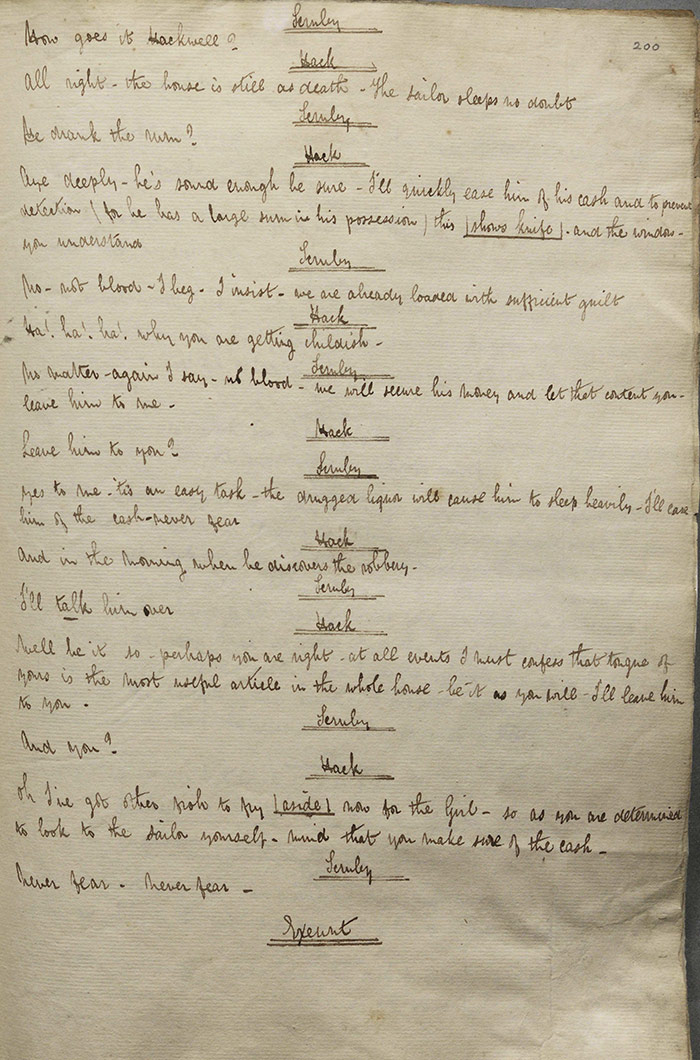

Nukes and Flutter decide to go and tease Peter some more in scene five. Hackwell and Sernby arrive to steal Ben’s money. Hackwell wants to murder him but Sernby, showing signs of conscience, convinces him to relent, saying that he will steal the money and talk him over in the morning.

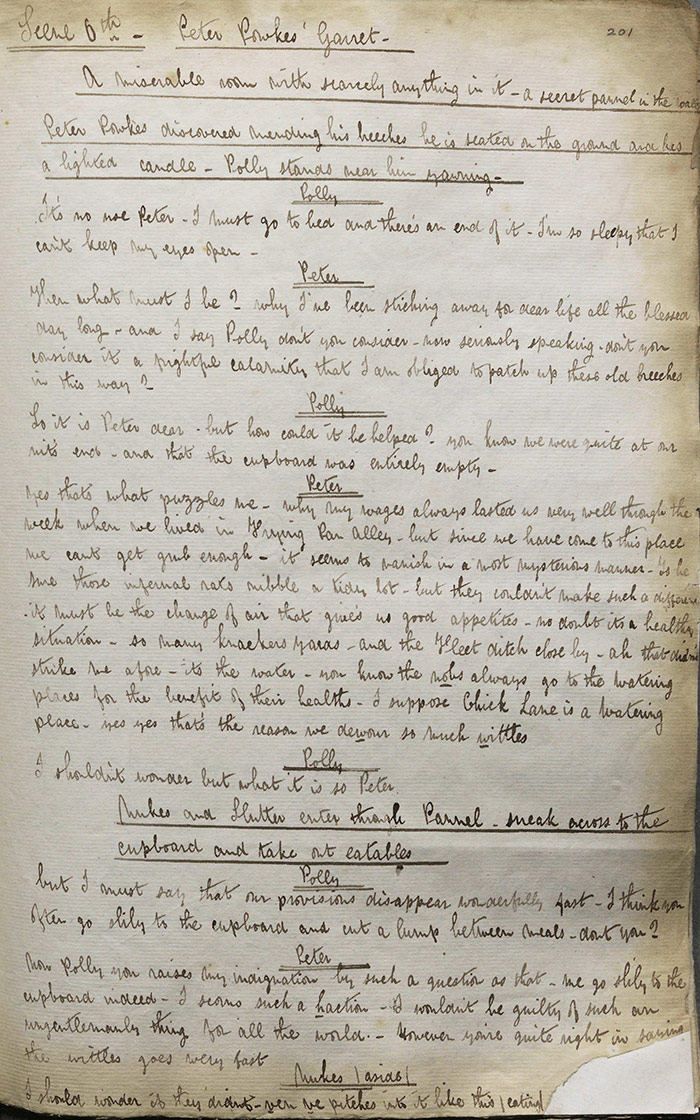

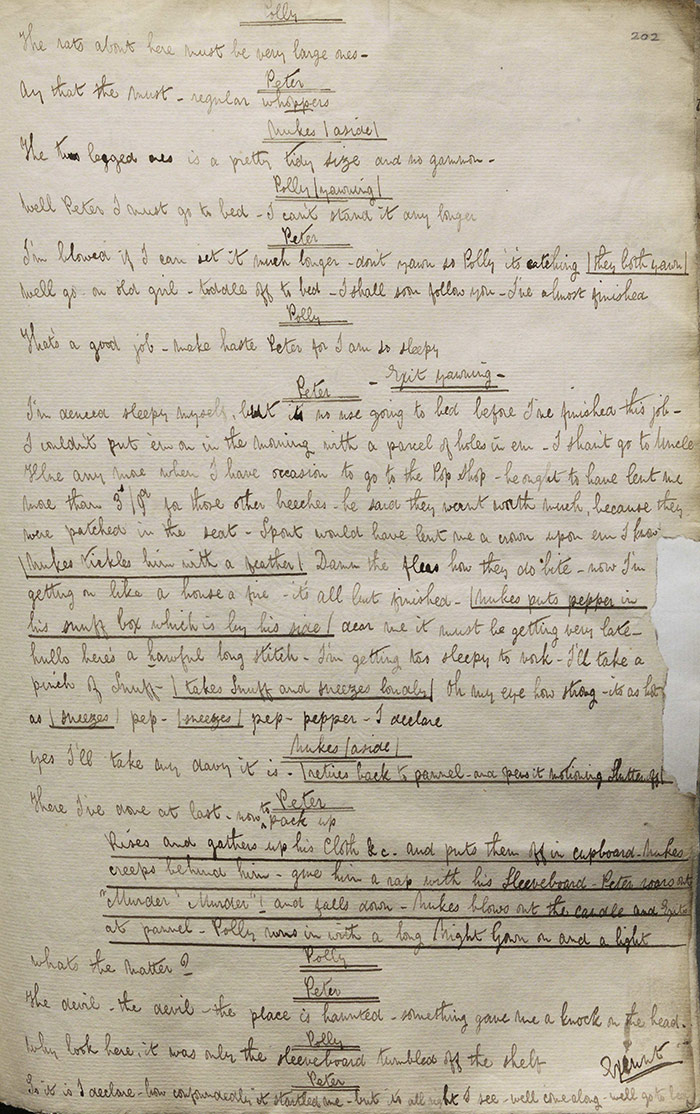

In Peter Powkes’s garret room, he is complaining about his money and food seemingly disappearing in mysterious fashion. As he speaks, Nukes and Flutter enter through a secret panel and take food out of a cupboard. Peter does some work; as he finishes up, Nukes sneaks up behind him and raps him on the head before disappearing with Flutter through the panel. Peter roars and collapses in fright.

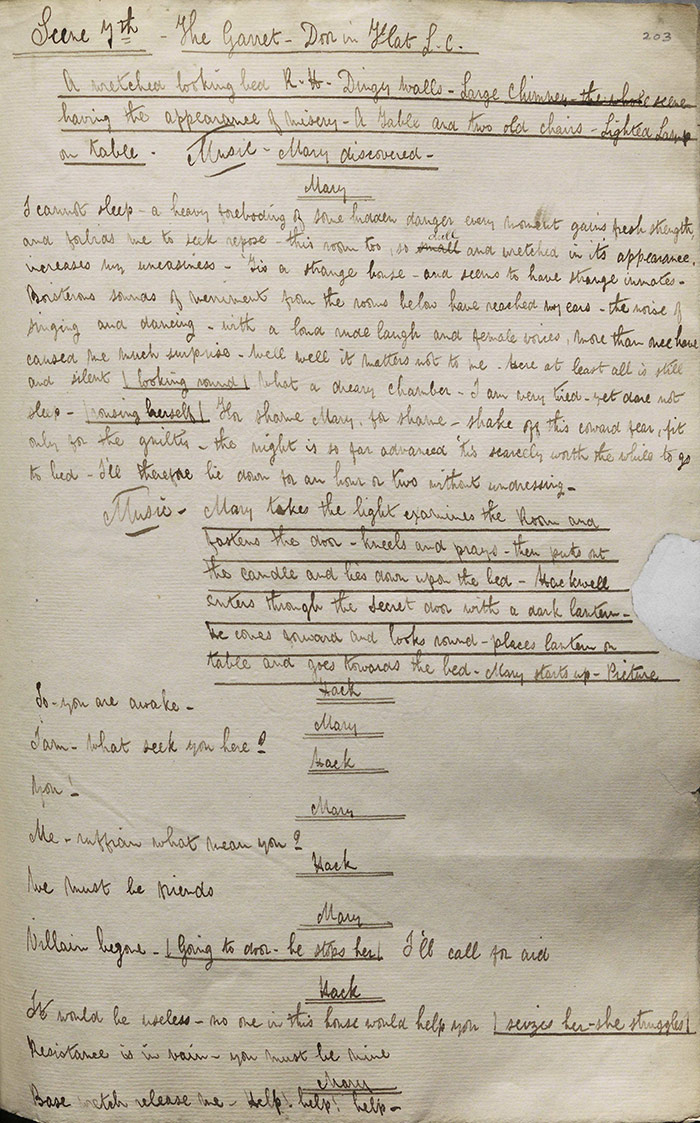

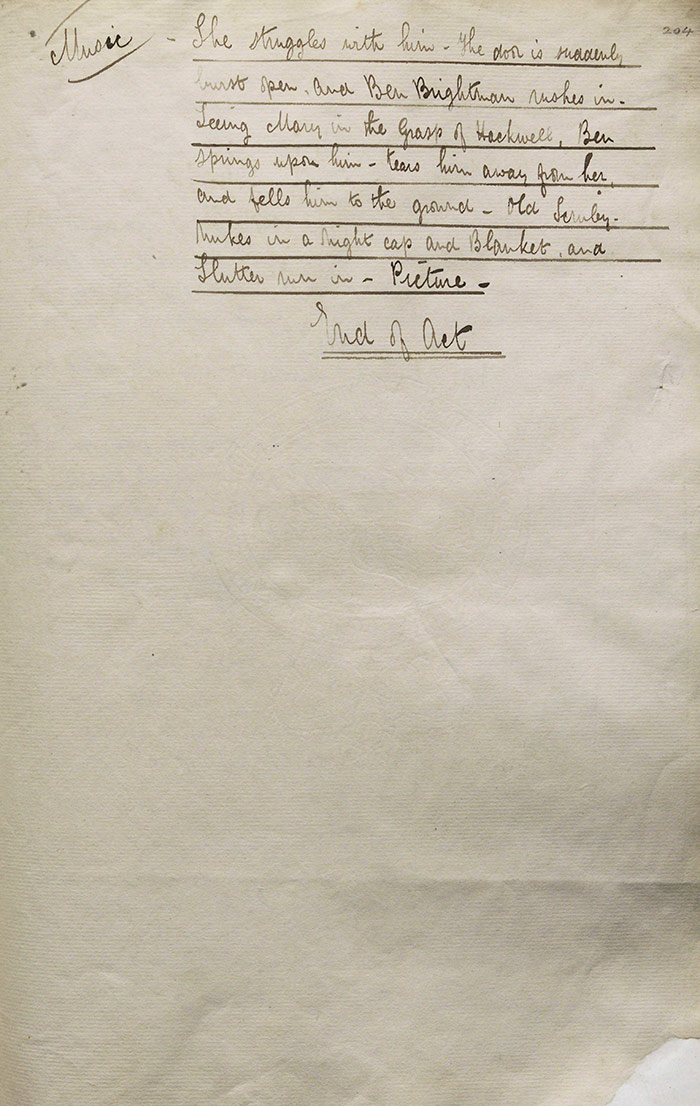

In scene seven, Mary is filled with foreboding at the wretched garret room she finds herself in. Hackwell enters through a secret door and assaults her, intending rape. She screams and Ben bursts through the door and knocks him down. Sernby and Flutter run in. The act ends in a tableau.

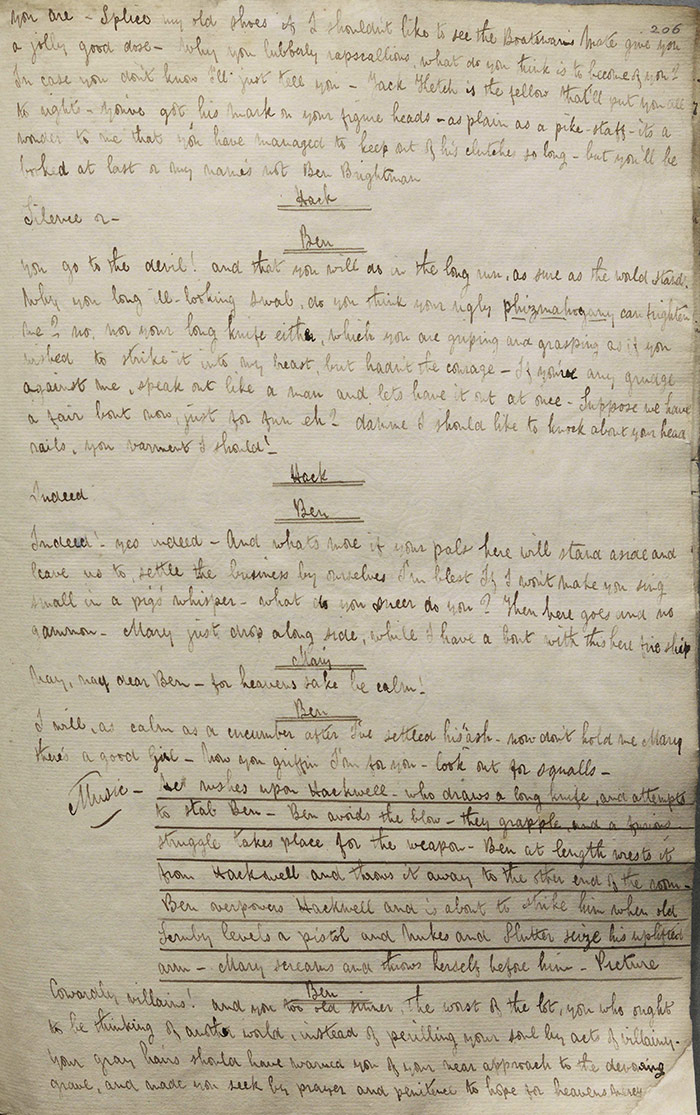

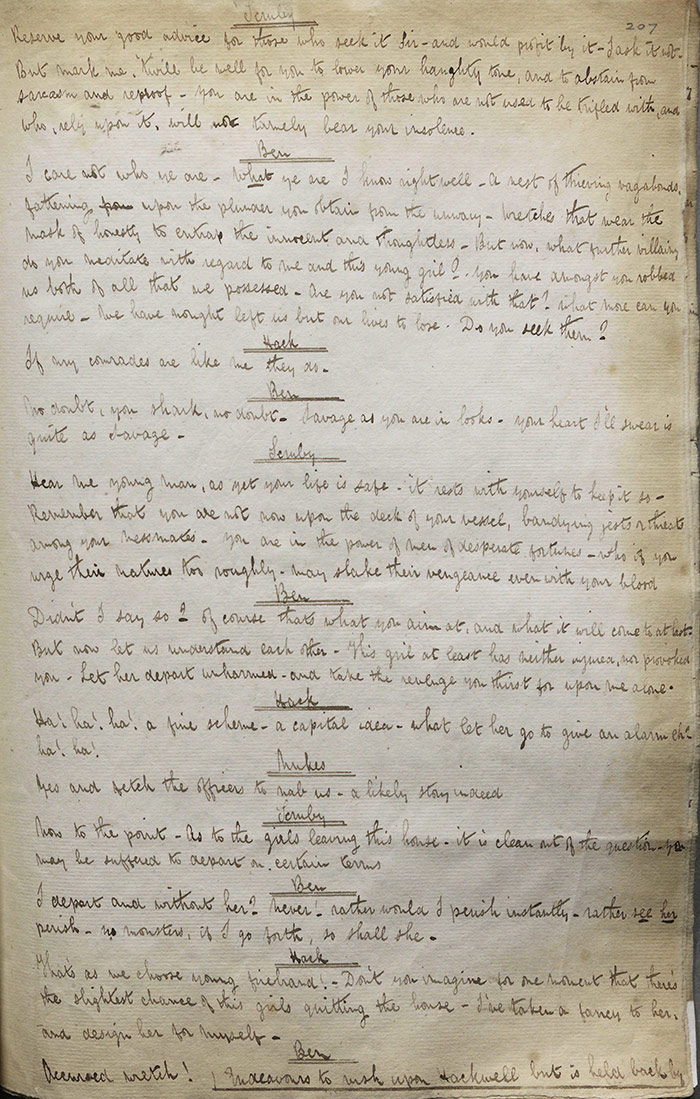

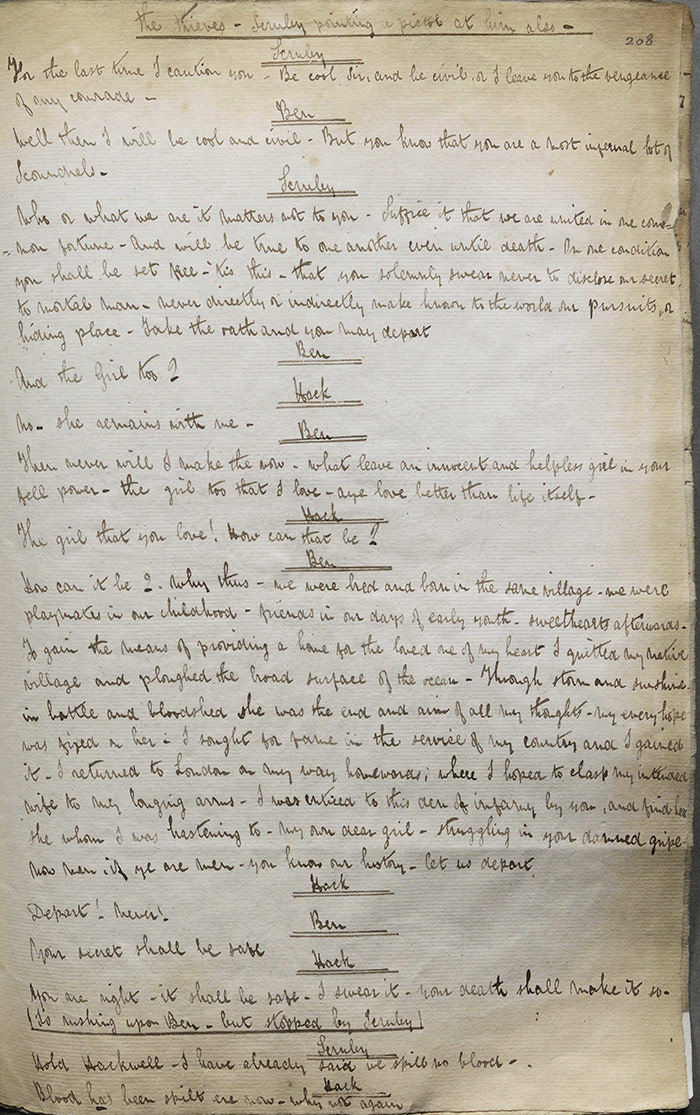

Act 2

Ben and Mary are locked in the same room. She tells him her tale of woe but he cheers her up by insisting that providence has brought them together. Hackwell, Sernby, Nukes, and Flutter come in. Ben is defiant and rushes the knife-wielding Hackwell. He overpowers him but then Sernby levels a pistol at him. Mary screams and throws herself in front of Ben. Tableau. The villains offer to let Ben go on certain terms. He asks them to let Mary go but Hackwell refuses, saying that he has taken a fancy to her. Ben swears never to leave without her, it is revealed that she is his sweetheart from youth. Hackwell wants to kill him but Sernby stops him, haunted by previous murderous acts that have taken place there. Ben is forcibly dragged out; Mary faints. Tableau.

In the Powkes’s room, Polly is puzzled by the mysterious disappearance of their food. Nukes enters through the secret panel and terrifies her out of her wits. She comes to and shouts for Peter. He arrives in and eventually makes sense of what has been happening to his food. Nukes, however, recruits them to fetch police officers and catch the gang. Mary is then heard screaming for help. Nukes goes to get her through the panel and urges Peter to get a weapon. Nukes and Mary come back through followed by Hackwell and Flutter, but they are prevented from coming in by Peter and Polly who are brandishing makeshift weapons.

In the third scene Peter runs out to a watchman, demanding he get help. He is sent to fetch more officers. Nukes tells all and gives himself up to his custody. The watchman says he might get a pardon and Nukes promises he would be a virtuous member of society. Peter returns with officers and Nukes leads them to the villains.

Ben is on the ground floor of the thieves’ house in the fourth scene. He can spy into the cellar below him and sees Hackwell and Sernby with a spade and pickaxe. Hackwell and Sernby are trying to hide the skeleton of a previous murder for fear of discovery. But the officers are heard knocking and panic ensues. Hackwell rushes up the stairs to revenge himself on Ben. In a dramatic and violent conclusion, Sernby confesses all and Ben stabs Hackwell, who still manages to escape through a hole in the wall. He falls to his death into the Fleetditch when the plank he is walking on breaks. The remaining characters and the officers form a concluding tableau.

Performance, publication, and reception

The manuscript was submitted to the Examiner on 14 August 1844 and was subsequently referred to the Lord Chamberlain on 16 August. It was intended for production at the Royal Albert Saloon on 20 August. It was refused a licence and never performed.

Commentary

The manuscript has no emendations related to censorship and was simply refused a licence out of hand for its overall tendency. Its inclusion in this resource might be objected to on the grounds that 1844 is outside our period of scrutiny; however, the rationale in favour is that it represents a culmination of theatrical and literary output dating back to 1839. Its prohibition in August 1844 was a result of a considerable public outcry about the links between the sensationalist Newgate novel, its theatrical progeny, and an actual, rather grisly, murder in 1840.

Bernard Courvoisier murdered his elderly employed Lord William Russell with a cutthroat razor on 5 May 1840. Russell had been critical of Courvoisier’s work as a valet and the young man was fearful of the potential damage to his ‘character’ and subsequent employment. Leaving aside its brutality, what was particularly astonishing about this crime was Courvoisier’s claim that he had been inspired by reading Jack Sheppard, William Harrison Ainsworth’s novel and illustrated by George Cruikshank.

Ainsworth’s novel had first appeared in serial form in Bentley’s Miscellany in summer 1839 and continued into 1840. Jack Sheppard (1702-1724) was a notorious housebreaker who was celebrated for his multiple escapes from prison before finally being hanged in 1724. His death was attended by an enormous crowd of Londoners and Harlequin Sheppard was staged just a fortnight after his execution, one of many offshoots of popular culture he inspired. Ainsworth’s novel emerged as one of the foremost Newgate novels—prose fiction that took crime and criminals as its subject—alongside Bulwer Lytton’s Paul Clifford, George Reynolds’s The Mysteries of London (1844-48), and Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837-8), the last also illustrated by Cruikshank. As Matthew Buckley has noted, Jack Sheppard provoked popular fervour and prompted a slew of pamphlets, plays, street shows, prints, and cartoons that took London by storm.

John Baldwin Buckstone’s theatrical adaptation (BL ADD MSS 42953, ff.88-118) was staged at the Adelphi Theatre but, such was the level of public interest, the mania soon spread:

At the MINORS – the Adelphi, the Surrey, the Victoria, Sadler’s Wells, and the Pavilion, Jack Sheppard, is drawing in crowds and filling the treasuries. It is useless to deplore this; let us hope that it is the daring courage he exhibited in relieving himself from difficulties, and not the vicious propensities that led into them, which excites the sympathy and calls down the applause of Jack’s crowded auditories. (The Charter, 3 November 1839).

The craze was sustained with more or less continuous performances right through to March 1840 (Theatrical Journal, March 1840) and there are explicit comparisons made with the ‘Tom and Jerry’ mania of the 1820s (The Odd Fellow, 9 November 1839). The newspapers are agreed on its enormous level of success although concerns about its immoral tendencies were also raised (The Champion and Weekly Herald, 3 November 1839). The Examiner’s office, however, had little such concerns with the manuscript of Buckstone’s play being passed through without a hitch. The Lord Chamberlain’s Day Book does contain this brief censorial instruction for a production in Hull Theatre:

You are desired to omit the following words in P. I. 2nd Sc 5th

Jack Sheppard

Oh God! In their Mercy either restore my mother or destroy the Son!

Mrs Sheppard

I will not pray for my poor Jack’s soul! I know it is wicked to do it. (28 Dec 1840)

However, the murder of Lord Russell put paid to this tolerance. While Buckstone’s play, having been licensed, was allowed to continue (although one wonders whether it did to any great extent), new theatrical productions in this line, such as The Theives House! were rejected out of hand. Indeed, that week in August also saw the prohibition of The Murder House; or, The Cheats of Chick Lane (Britannia) and The Old House of West Street (Surrey). The Lord Chamberlain ordered a number of police raids on some of the minor theatres in 1845 and it was discovered that the City of London Theatre was showing Jack Sheppard and selling tickets on a two for the price of one basis. Manager Frederick Fox Cooper’s admission of the lowest class of society to this play cost him dear as he was forced to give up his ownership for not being able to make the theatre pay at standard admission prices. In 1848, the Surrey and Haymarket theatres were also refused permission to stage versions of the Jack Sheppard story.

Further reading

Matthew Buckley, ‘Sensations of celebrity: Jack Sheppard and the mass audience’, Victorian Studies (2002): 423-63.

Derek Forbes, ‘‘Jack Sheppard’ plays and the influence of Cruikshank’, Theatre Notebook 55:2 (2001): 98-123.

Keith Hollingsworth, The Newgate Novel, 1830–1847: Bulwer, Ainsworth, Dickens & Thackeray (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1963).

F.S. Schwarzbach, ‘Newgate Novel to Detective Fiction’ in Patrick Brantlinger and William B. Thesing (eds), A Companion to the Victorian Novel (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 227-43.

John Russell Stephens, ‘Jack Sheppard and the Licensers: The Case Against Newgate Plays’, Nineteenth Century Theatre Research 1 (1973): 1–13.

_______ The Censorship of English Drama 1824-1901 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 61-77.

George Taylor (ed), Jack Sheppard. Trilby and Other Plays: Four Plays for Victorian Star Actors, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 1-83.