Guido Fawkes (1840) BL ADD MS 42956, ff.742-756 and BL ADD MS 42956, ff.756-775

Author

Edward Stirling (d. 1894)

Stirling was born in Oxford; various dates of birth are in circulation ranging from 1807 to 1811. When his father died, he lived with his brother who was the landlord of the King’s Arms Inn. He moved to London and made his acting debut at the Pavilion Theatre in 1828 before moving to the Richmond Theatre. Stints at Windsor, Croydon and Gravesend followed before he moved to Scotland. He returned to London and married an actress (Fanny Clifton, according to one source; Mary Anne Hall, according to another).

Sadak and Kalasrade, produced in Birmingham,was one of his first dramatic efforts and it was a success. He became acting manager of the Adelphi Theatre in 1838 and was stage manager 1843-44 before travelling with Frederick Yates (Adelphi proprietor) through the provinces. He was also stage manager at Covent Garden, the Surrey, the Olympic, and Drury Lane.

He wrote over 190 plays but he is best known for his adaptions of Charles Dickens’s novels. His adaption of The Cricket on the Hearth ran for over 90 performances in 1845-56. Other adaptions included Nicholas Nickleby; or, Doings at Do-the-Boys Hall! (1838, 1839); Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress (1838, 1840); The Old Curiosity Shop; or, One Hour from Humphrey's Clock (1840); Barnaby Rudge (1841); and, A Christmas Carol; or, Past, Present, and Future (1843, 1859).

His surname is occasionally spelt ‘Sterling’ but he is not to be confused with prominent journalist Edward Sterling (1773-1847).

Plot

The plot synopsis is based on the original version; significant alterations are discussed in the censorship section below.

Act I

The two act play opens with citizens sorrowfully discussing the upcoming execution of Robert Woodroofe on Market Street Lane near the Old Salford Bridge in Manchester. Woodroofe is to be burnt at the stake for Catholic tendencies. The bell tolls and Woodroofe, escorted by pikemen and Roger Clayton, enters. Elizabeth Orton enters and halts them. Despite being rebuffed by Clayton, she asks for a blessing and receives a book, presumably a bible, from Woodroofe, thanks to the intervention of Humphrey Chetham, a wealthy merchant. Clayton, informed that she lives in a cave beside the river Irwell near Ordsall Hall, decides that her cave must be searched for the Jesuit priest, Oldcorne whom he believes to be sheltered by Sir William Radcliffe and his daughter. While this has been going on, Woodroofe has been burnt to death, signaled by a ‘light seen from the bridge’ and a ‘murmur of horror’ (f.744r). Orton re-enters, followed by a mob, and announces a vision of nineteen shadowy figures promising vengeance on their persecutors, much to the chagrin of Clayton. Humphrey urges her to flee but she is defiant to the point that Clayton orders his pikemen to kill her. Suddenly, Guy Fawkes appears to defend her. As the situation grows more heated, Orton leaps from the bridge; Guy follows her to save her.

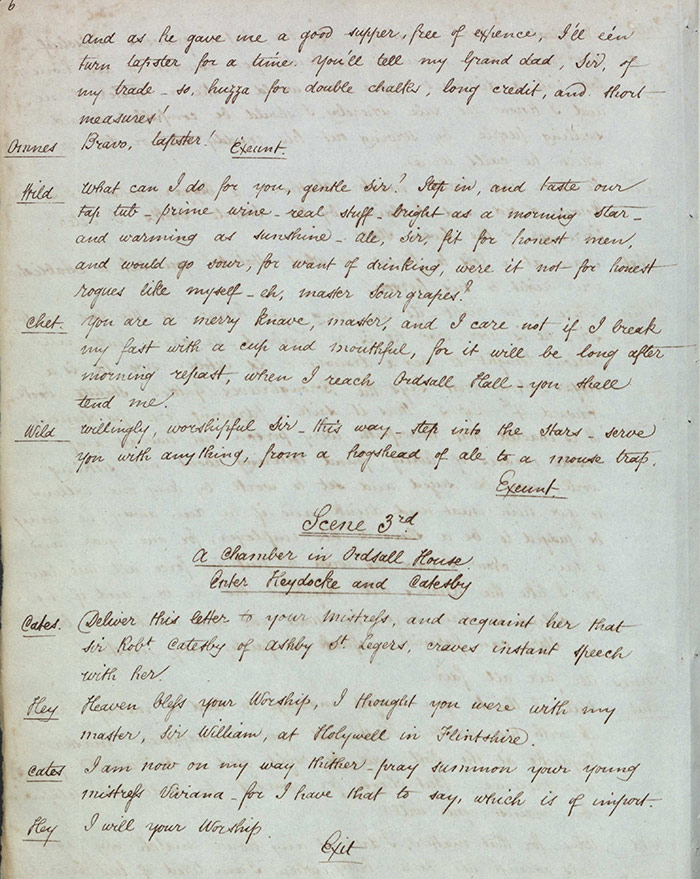

The second scene takes place in the Seven Stars Tavern (f.745r) where Watling Wildduck is discovered, pursued by Tunbelly Porringer. Humphrey intervenes to see what is the matter and Porringer says he is putting Wildduck, something of a vagrant, to work as is his right under statute. Wildduck seems to come round to the idea and invites Humphrey in for wine before he travels to Ordsall Hall where Sir Radcliffe and his daughter lives.

The next scene opens in Ordsall Hall and with an exchange between Heydocke, a servant and Wildduck’s grandfather, and Sir Robert Catesby (f.745v). Catesby makes some unwanted advances to Viviana Radcliffe before telling her that Clayton has a warrant for her father’s arrest for sheltering Oldcorne. The priest, who has joined them, vows to quit the house immediately as the raid is coming that night, but both Catesby and Viviana urge him to stay and hide. Catesby says he will go to Chester to warn Radcliffe for which Viviana is grateful but she tells him to forget her as she is in love with another. After she leaves, Catesby repeats his declaration that he will have her and Oldcorne promises to assist him.

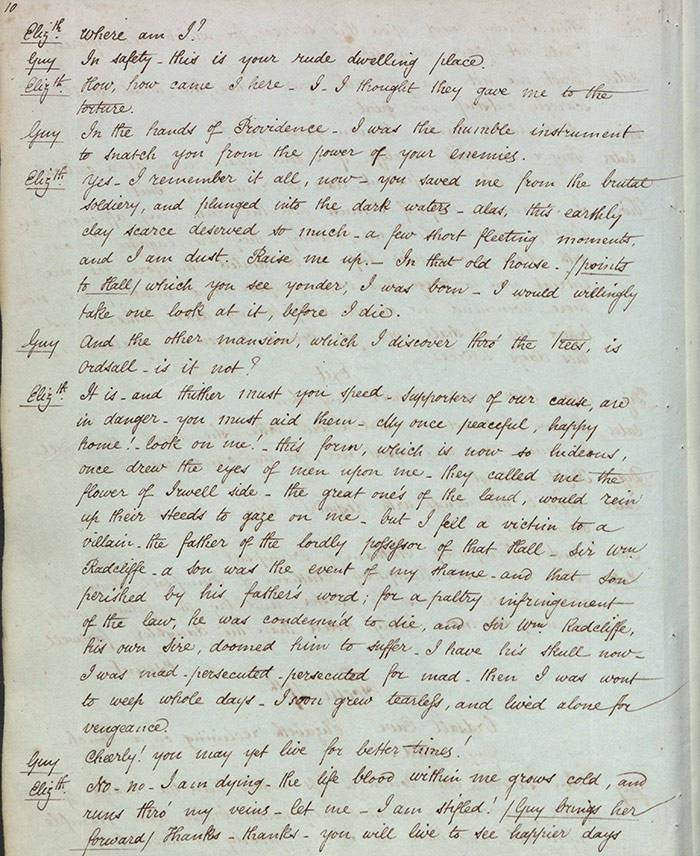

The fourth scene finds Elizabeth Orton and Guy Fawkes in a cave (f.746v). Before Orton dies, she tells Fawkes that she bore a child to Sir Robert Radcliffe of Ordsall Hall, a child who was hanged by his own father for a petty infringement. She also tells him that she has foreseen Fawkes’s death at the hands of an executioner. But he is undaunted and ‘would laugh to scorn their efforts, and strike the ermined tyrant on his throne!’ (f.747r).

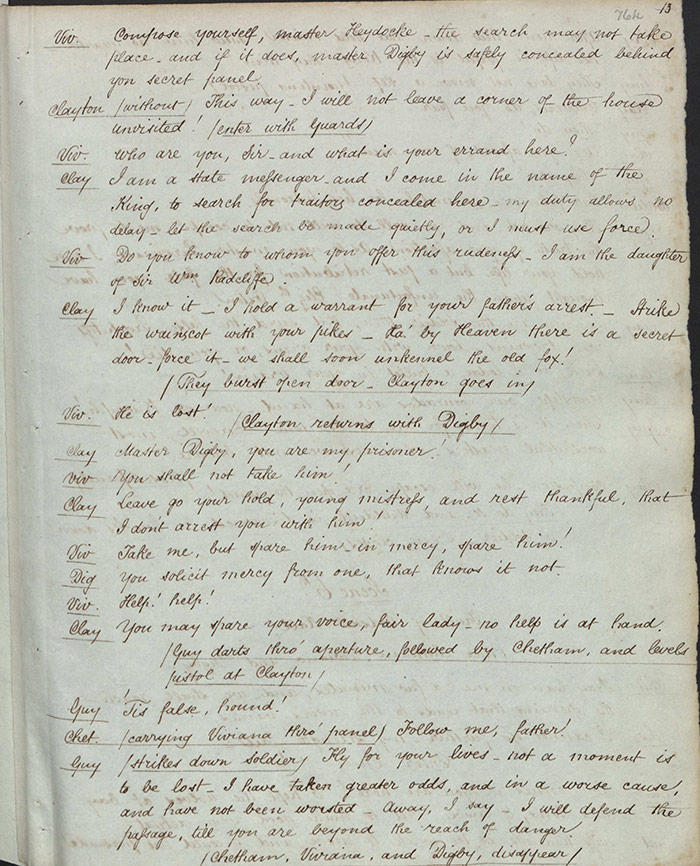

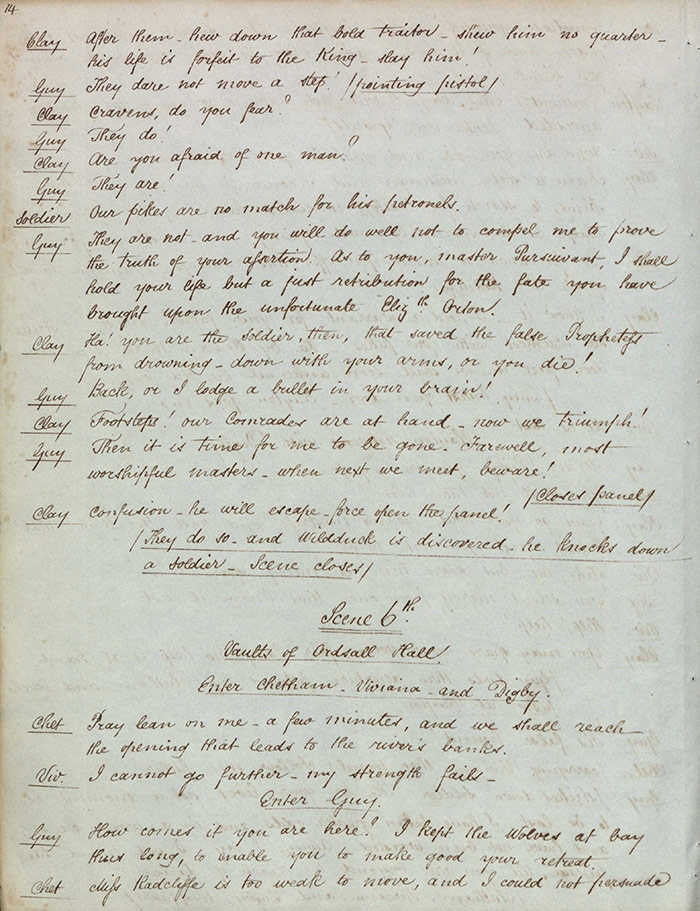

In the fifth scene, Clayton and his men arrive at Ordsall and discover Oldcorne hiding. In a scuffle, Fawkes and Chetham rescue the priest and Viviana, and escape with Wildduck’s aid. The subsequent scene finds the escapees in the vaults of the house trying to make it to Chetham’s horses beside the river (f.748r). Separately, Wildduck is captured by Clayton’s men, having led them away from the others. The final scene of the first act takes place on Chat Moss, a marshy bog through which Chetham knows a secret path (f.749r). Clayton and soldiers are in hot pursuit but are distracted by a will-o’-the-wisp; they all perish save Clayton who is spared.

Act II

At the Seven Stars tavern, Clayton and Catesby make a deal: in exchange for the capture of the Radcliffe family and Oldcorne, Clayton must engineer the death of Chetham (f.750r). Wildduck overhears the plan but is discovered and ordered to the pillory by Clayton before he exits. However, Dame Porringer intervenes and rescues Wildduck.

In the second scene, Viviana and Humphrey’s love is to the fore (f.751r). Oldcorne, speaking for Viviana’s father, makes clear that they cannot marry unless Humphrey converts to Catholicism which he is not prepared to do. Oldcorne tries to persuade her to marry Catesby rather than take the veil but she is adamant in her refusal. Fawkes enters and tells Oldcorne of his suspicions that Catesby is not committed to their cause. Dame Porringer confirms this when she tells them of his involvement in Wildduck’s sentence to the pillory. Fawkes tells Oldcorne to fly to the Hall and he will go to rescue Wildduck.

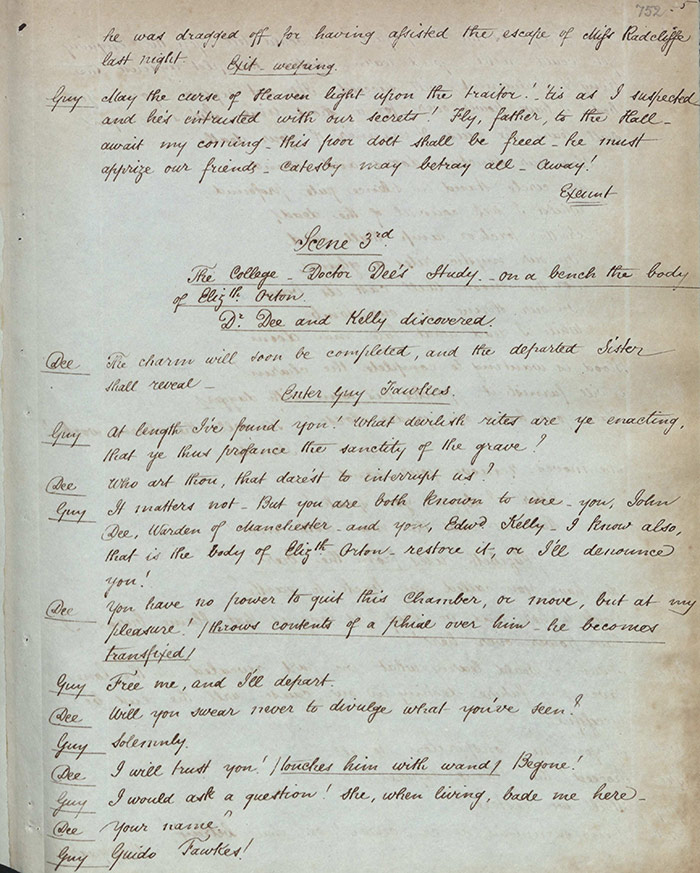

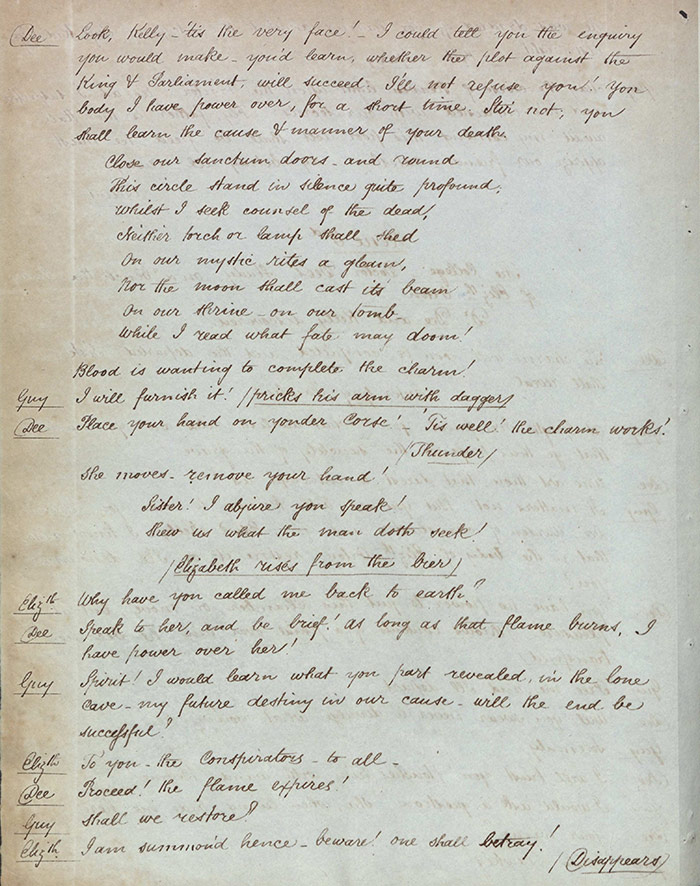

The third scene is set in Christ’s College in Manchester where John Dee performs a magical rite over the body of Elizabeth Orton with the assistance of [Edward] Kelly. Fawkes bursts in to stop him but he is ‘transfixed’ (f.752r) by Dee. When Dee learns his name, he says he can answer his query over whether the plot will succeed. Fawkes offers his blood to complete the ritual and the spirit of Orton rises from her bier. She is enigmatic but warms him of betrayal before she disappears. Excited, Fawkes demands more and Dee shows him ‘(a group of skeletons seen – pointing to Guy stretched upon the wheel)’ (f.753r). The scene closes with Fawkes describing the vision of his torture and death before he sinks to the ground.

In scene four Catesby accosts Humphrey and provokes a fight. However, Fawkes intervenes, tells Chetham to fly to Viviana’s aid. He then disarms Catesby and but ‘cannot slay a helpless wretch, or groveling worm’ (f.754r). He exits and Catesby, realizing he has been exposed, declares he will join the king’s party.

Back in Ordsall Hall, the fifth scene finds Viviana and Oldcorne mulling over their options when Chetham and Fawkes arrive to announce Catesby’s perfidy (f.754r). Heydocke then tells them that the king’s soldiers have found a barrel of gunpowder and plan to blow up the house. Fawkes leaves to intercept them.

In the final scene Clayton, Catesby, and soldiers are outside Ordsall Hall (f.755r). Clayton directs a soldier to place the gunpowder beside the building. Fawkes knocks out the soldier and in a chaotic end to the drama, Chetham kills Catesby and Fawkes fires on the barrel, blowing up Clayton and his party. Viviana swears herself for Chetham while Fawkes concludes with a bold declaration ‘The hour of vengeance is arrived – we are free!’. A ‘Grand Tableau’ ends the drama.

Performance, publication, and reception

The manuscript was submitted on 14 August 1840 by George Wilson, copyist for the English Opera House. It was referred to the Lord Chamberlain on 16 August who must have endorsed his Examiner’s concerns as a revised version was submitted on 27 August.

William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882), novelist, published Guy Fawkes, ‘an historical romance’, in Bentley’s Miscellany from January 1840. Ainsworth was also the author of Jack Sheppard (1839) which inspired The Thieves House! (1844), also included in this resource. Ainsworth’s Guy Fawkes drew heavily on John Lingard’s Catholic revisionist History of England (1819-1830) which is cited extensively in the preface. The key point made by Ainsworth is that the Gunpowder Plot emerged explicitly from a culture of financial extortion and oppression by Scottish nobles on English Catholics sanctioned by James I. Ainsworth’s novel then—and the play it inspired—need to be understood within the context of Whiggish tradition of tolerance and Catholic Emancipation. Ainsworth stated ‘One doctrine I have endeavoured to enforce throughout, – TOLERATION’ (xi).

The novel was published in three volumes by Richard Bentley in August 1841 and the stage version was intended to coincide with this event. The play’s action is based, somewhat loosely, on the events of the first volume.

A review dated 27 August 1840 in the Morning Chronicle refers to the first performance as having taken place on 24 August although the resubmission of the manuscript for licensing is dated 27 August. It is plausible that the resubmission was simply misdated – Wilson perhaps should have written 17 rather than 27, for instance. There is also the more tantalizing possibility that the licence was sought after the fact, the manager having agreed to make the desired changes and the Examiner being satisfied with those assurances: it may that Stirling’s considerable output served to reassure the Examiner that his was a safe pair of hands in terms of revisions. However, there is no correspondence or other evidence to support this theory.

The Times (26 August 1840) noted that ‘The drama of Guido Fawkes was produced last night with success, the objections of the Lord Chamberlain having been removed’ but refrains from any further comment – perhaps a comment in itself from the conservative publication. The review in the Morning Chronicle offered a more sustained analysis and, while it fell short of enthusiasm, it was very impressed by the John Dee prophetic tableaux: ‘The entire scene […] is one of the most effective we have ever beheld, and ought, if there were nothing else good in the drama, to ensure a succession of crowded audiences.’ Nonetheless, the writer found it ‘impossible’ to predict the viability of the drama as although there was a good-sized audience, there were ‘not more than forty or fifty applauding, and about two hissing’. The Literary Gazette (29 August 1840) opined, somewhat cheekily:

The formidable Guido Fawkes, after having, merely in MS., terrified the Lord Chamberlain out of his chair and given the Young Licenser of dramas such a twist as will make him remember (the fifth of November and) the office he holds to the last day of his life, was produced on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, &c without any ill effects whatever. This extraordinary fact must either have proceeded from the people in authority having discovered and countermined the author’s plot; or from the author’s never entertaining any dangerous plot at all: which we cannot tell.

There were a number of performances over the following two weeks (it was staged on 26, 28 August and 1-4, 7-10 September) which suggests it was a fair success.

The play was not published.

Commentary

The manuscript is devoid of any explicit indication of the censorial emendation we typically see on other manuscripts. The original manuscript has ‘Referred to the Lord Chamberlain 8/16/40’ inscribed on its title page. This suggests that the general tendency of the drama was sufficient to warrant the Examiner, John Mitchell Kemble, just in office a few months, to seek the views of his employer.

John Russell Stephens identifies social unrest in the 1830s and 1840s (e.g. Chartism, Reform agitation) as explaining the refusal of authorities to license plays based on ‘plots, conspiracies, and social upheaval’ such as Guido Fawkes (55). Stephens is surely right in this but we should also pay attention to the play’s sympathetic depiction of Catholicism—with Guy Fawkes appearing heroic on a number of occasions—which may have provoked concern on a personal level as well. When his father, Charles Kemble, was made Examiner in 1836, there were some strident objections to the appointment on the grounds of his Catholicism:

With such claimants as [John Maddison] Morton and [Frederick] Reynolds upon the list, we demand in the name of the public, what sinister, private, and corrupt influence has been at work to introduce this cowardly Jesuit into an office under a Protestant King, where he has thus the uncontrolled exercise of working Papist influences? (The Age [30 October 1836], cited in George Colman the Younger, 301)

Since John Mitchell Kemble contemplated taking holy orders in the Anglican church, he was spared the taint of popery. Yet the memory of his father’s treatment in 1836 surely registered with him the rancour that religion could leave in its wake and may have left him wary of its capacity to rouse a playhouse audience.

The revised version – submitted 27 August 1840 (less than two weeks after the original was submitted on 14 August) has one prominent change, as noted by Stephens. The first scene of the revision has these few lines of dialogue removed:

1st Citizen: A sad day this my masters – sorrowful times that see one of our fellow townsmen given to the flames. Poor master Woodroofe! I had hoped the days of fire & faggot expired with Mary, of cruel memory.

2nd Citizen: Why is the good master Woodroofe to be burnt like a felon at the stake?

1st Citizen: Because he dares follow the faith of his father, and choose rather to part with life, than sin against his conscience. (Bell tolls) That’s the awful signal – the Virgin support him! [14 August, f.743v]

The revision has no immediate sense of violent oppression on the part of the state. It is worth noting at this point that in Ainsworth’s novel, the reference to monarchical cruelty above is actually to Elizabeth, rather than Mary.

Overall, the reader of the second manuscript will find a number of speeches that have been filled out and made more florid in many cases. There are some specific points of comparison in the manuscripts that are worth noting, primarily relating to revisions which tone down the representation of incipient violence in England. Heydocke’s exasperated observation that ‘a man may go to bed, healthy & strong, and awake in the morning, with his head under his arm‘ (14 August, f.746r) does not appear in the revised version (27 August, f.760v). Another similar example can be seen when contrasting Fawkes’s vengeful speech after Elizabeth Orton’s death in the first act with the revised lines. Here is the original version:

She’s dead – and with her, the secret of my fate! My oath is pledged, and tho’ all powers of darkness opposed, Guido Fawkes would laugh to scorn their efforts, and strike the ermined tyrant from his throne! (14 August, f.747r)

And here is the later version, without the explicit threat of upturning the social order:

She’s dead – and with her, the secret of my fate, unless, indeed, this Wizard [i.e. John Dee], whom I’ve before heard named in terms of wond’rous praise, can unfold the web. - But come what way, I will go on – my oath is pledged, and neither death or torture shall stay me from my purpose. (27 August, f.763r)

Earlier in the same scene, a speech which posits Guy as prophet of class-based retribution is also heavily edited. We originally have:

Poor sufferer! ‘tis thus they’d trample upon all who have the sin of poverty on their souls – they are ground down to better their morals – their harmless sports forbidden, lest they should become vicious – their hours of relaxation limited, for fear they grow idle – but the time will come, when every man shall sit under his own roof, and none have power to make him fear! (14 August, f.746v)

The corresponding speech on (27 August, f.762r) is considerably milder in tone.

Nonetheless, the sympathetic portrayal of Fawkes indicates a considerable shift from earlier in the century. William Henry Ireland’s The Catholic, 2 vols (London: W. Earle, 1807, for instance, refers to the Gunpowder plot as an event that would have ‘fettered Englishmen with the chains of bigotry, by giving up this land to all the horrors of relentless popery and sanguinary superstition’ (1: 26). Despite the intervention of the censor’s office, the toleration championed in Ainsworth’s novel remains in both versions of the play.

Readers may also wish to reflect on the much more graphic speech given in the revised manuscript by Fawkes after witnessing Dee’s prophetic visions: compare (14 August, f.753r) to (27 August, f.769v). This may simply be Stirling writing in a more expansive mode. Alternatively, it may reflect officialdom’s desire that the price of rebellion be made clear and unequivocal.

Further reading

The Adelphi Theatre Calendar: A Record of Dramatic Performances at a Leading Victorian Theatre

https://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/mgmt.htm

William Ainsworth, Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason (London: Richard Bentley, 1841).

[available on archive.org]

Philip V. Allingham, ‘Edward Stirling (1809-94): Dramatist, Adapter, Actor, and Stage Manager’, The Victorian Web http://www.victorianweb.org/mt/adaptations/stirling.html

Jeremy Felix, George Colman the Younger, 1762-1836 (New York: King’s Crown Press, 1946).

[available on Hathitrust.org]

John Russell Stephens, The Censorship of English Drama 1824-1901 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 54-55.

Actors by Daylight; or, Pencillings in the Pit 41 (8 December 1838), 321-23.