The Prodigal Son; or, Parental Kindness (1828) BL ADD MSS 42893, ff. 357-58

Author

Anonymous

Plot

Given the brevity of the piece, a full transcription is offered here. Obvious printing errata have been silently corrected.

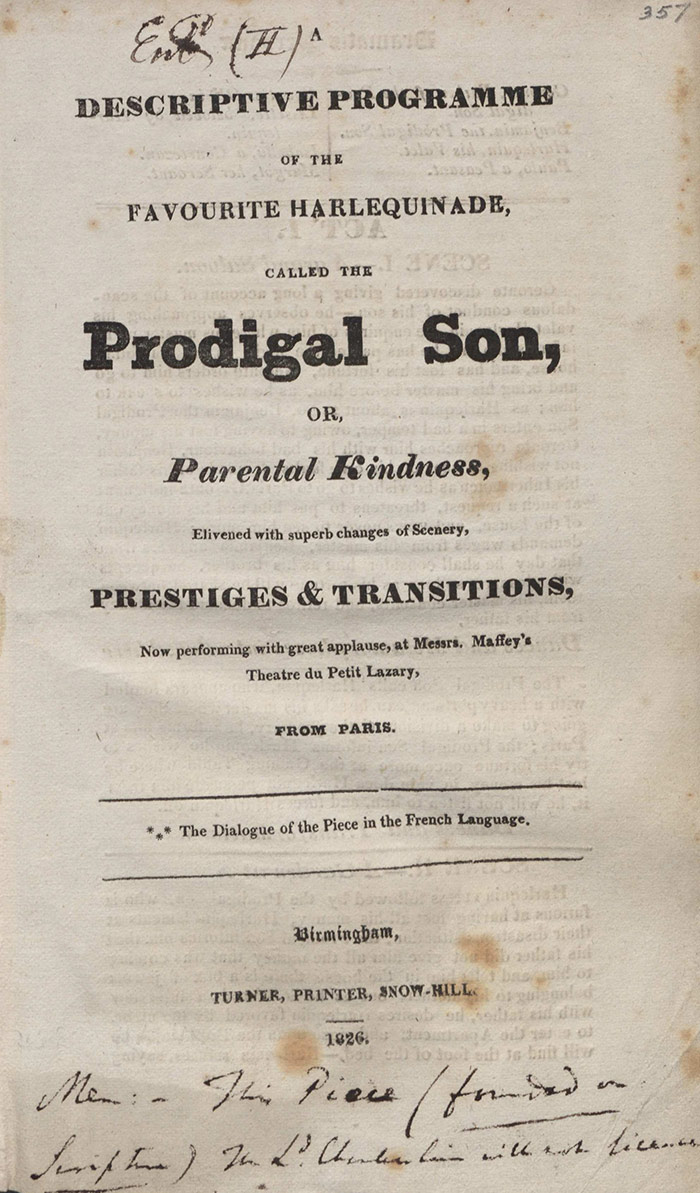

(f.357r)

A

DESCRIPTIVE PROGRAMME

OF THE

FAVOURITE HARLEQUINADE,

CALLED THE

Prodigal Son,

OR,

Parental Kindness,

Enlivened with superb changes of Scenery,

PRESTIGES & TRANSITIONS,

Now performing with great applause, at Messrs. Maffey’s

Theatre du Petit Lazary,

FROM PARIS.

*** The Dialogue of the Piece in the French Language.

Birmingham,

TURNER, PRINTER, SNOW-HILL

1826.

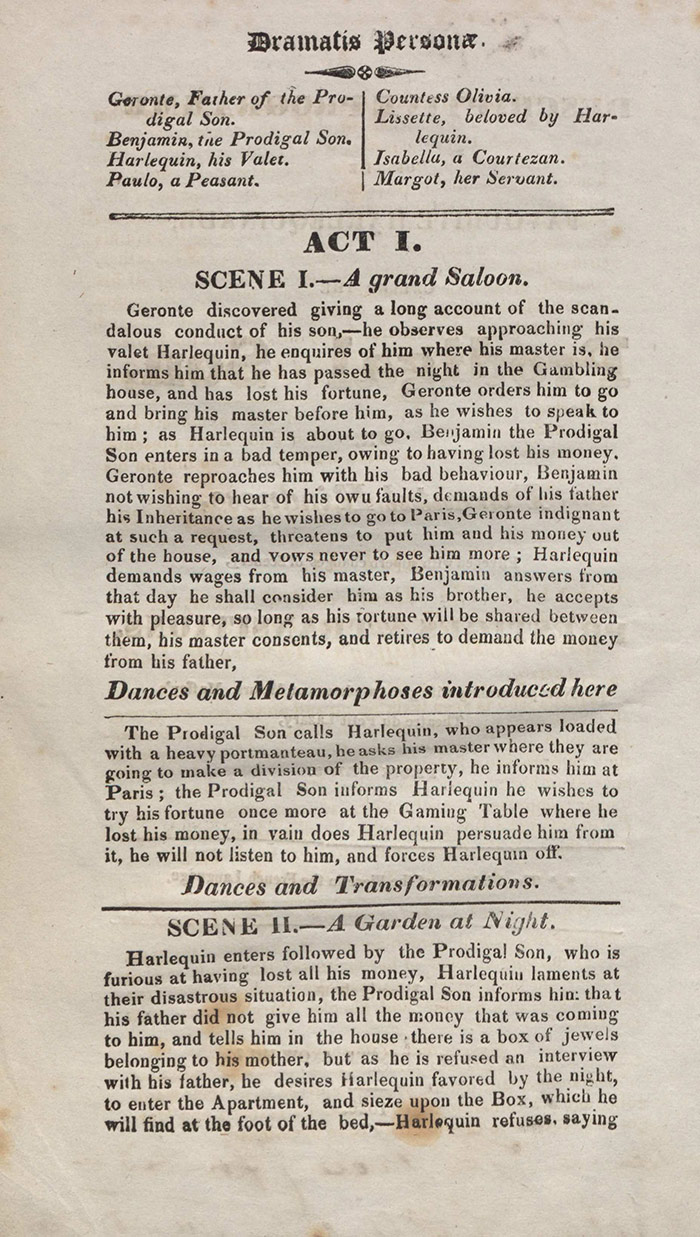

(f.357v)

Dramatis Personæ

Geronte, Father of the Prodigal Son. Countess Olivia.

Benjamin, the Prodigal Son. Lissette, beloved by Harlequin.

Harlequin, his Valet. Isabella, a Courtezan.

Paulo, a Peasant. Margot, her Servant.

ACT I.

SCENE I. ─ A grand Saloon.

Geronte discovered giving a long account of the scandalous conduct of his son, ─ he observes approaching his valet Harlequin, he enquires of him where his master is, he informs him that he has passed the night in the Gambling house, and has lost his fortune, Geronte orders him to go and bring his master before him, as he wishes to speak to him; as Harlequin is about to go, Benjamin the Prodigal Son enters in a bad temper, owing to having lost his money. Geronte reproaches him with his bad behaviour, Benjamin not wishing to hear of his own faults, demands of his father his Inheritance as he wishes to go to Paris, Geronte indignant at such a request, threatens to put him and his money out of the house, and vows never to see him more; Harlequin demands wages from his master, Benjamin answers from that day he shall consider him as his brother, he accepts with pleasure, so long as his fortune will be shared between them, his master consents, and retires to demand the money from his father,

Dances and Metamorphoses introduced here

The Prodigal Son calls Harlequin, who appears loaded with a heavy portmanteau, he asks his master where they are going to make a division of the property, he informs him at Paris; the Prodigal Son informs Harlequin he wishes to try his fortune once more at the Gaming Table where he lost his money, in vain does Harlequin persuade him from it, he will not listen to him, and forces Harlequin off.

Dances and Transformation.

SCENE II. ─ A Garden at Night.

Harlequin enters followed by the Prodigal Son, who is furious at having lost all his money, Harlequin laments at their disastrous situation, the Prodigal Son informs him that his father did not give him all the money that was coming to him, and tells him in the house there is a box of jewels belonging to his mother, but as he is refused an interview with his father, he desires Harlequin favored by the night, to enter the Apartment, and seize upon the Box, which he will find at the foot of the bed, ─ Harlequin refuses, saying

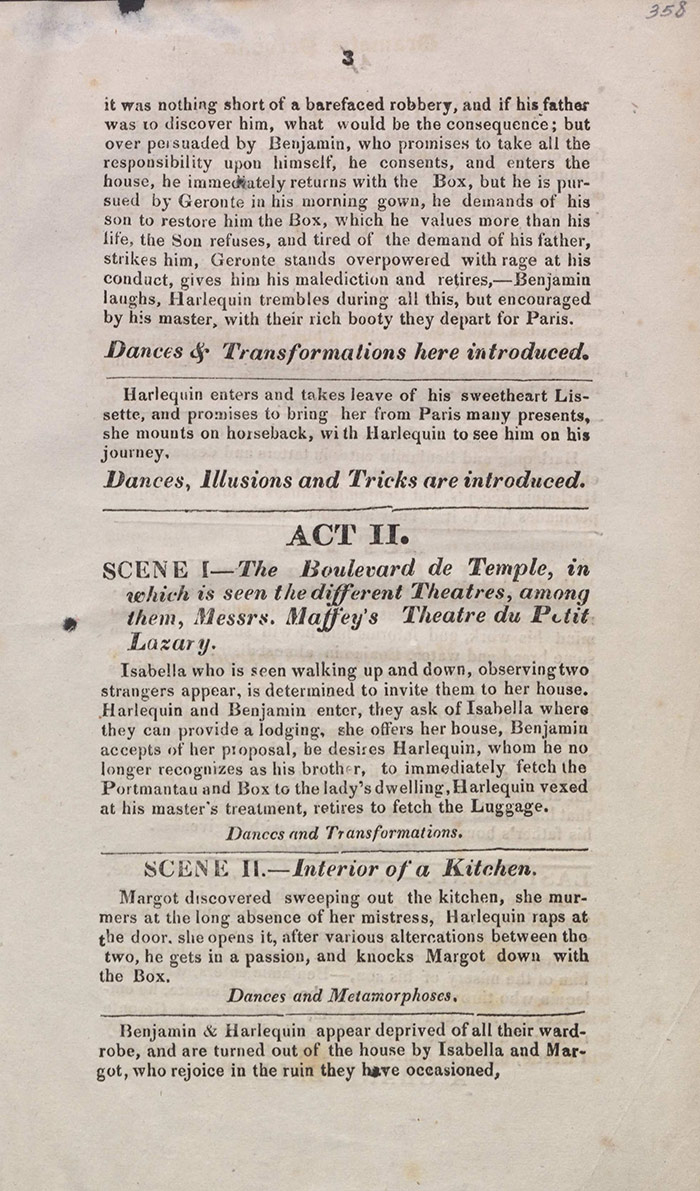

(f.358r)

it was nothing short of a barefaced robbery, and if his father was to discover him, what would be the consequence; but over persuaded by Benjamin, who promises to take all the responsibility upon himself, he consents, and enters the house, he immediately returns with the Box, but he is pursued by Geronte in his morning gown, he demands of his son to restore him the Box, which he values more than his life, the Son refuses, and tired of the demand of his father, strikes him, Geronte stands overpowered with rage at his conduct, gives him his malediction and retires, ─ Benjamin laughs, Harlequin trembles during all this, but encouraged by his master, with their rich booty they depart for Paris.

Dances & Transformations here introduced.

Harlequin enters and takes leave of his sweetheart Lisette, and promises to bring her from Paris many presents, she mounts on horseback, with Harlequin to see him on his journey.

Dances, Illusions and Tricks are introduced.

ACT II.

SCENE I ─ The Boulevard de Temple, in which is seen the different Theatres, among them Messrs. Maffey’s Theatre du Petit Lazary.

Isabella who is seen walking up and down, observing two strangers appear, is determined to invite them to her house. Harlequin and Benjamin enter, they ask of Isabella where they can provide a lodging, she offers her house, Benjamin accepts of her proposal, he desires Harlequin, whom he no longer recognizes as his brother, to immediately fetch the Portmanteau and Box to the lady’s dwelling, Harlequin vexed at his master’s treatment, retires to fetch the Luggage.

Dances and Transformation.

SCENE II. ─ Interior of a Kitchen.

Margot discovered sweeping out the kitchen, she murmurs at the long absence of her mistress, Harlequin raps at the door, she opens it, after various altercations between the two, he gets in a passion, and knocks Margot down with the Box.

Dances and Metamorphoses.

Benjamin & Harlequin appear deprived of all their wardrobe, and are turned out of the house by Isabella and Margot, who rejoice in the ruin they have occasioned,

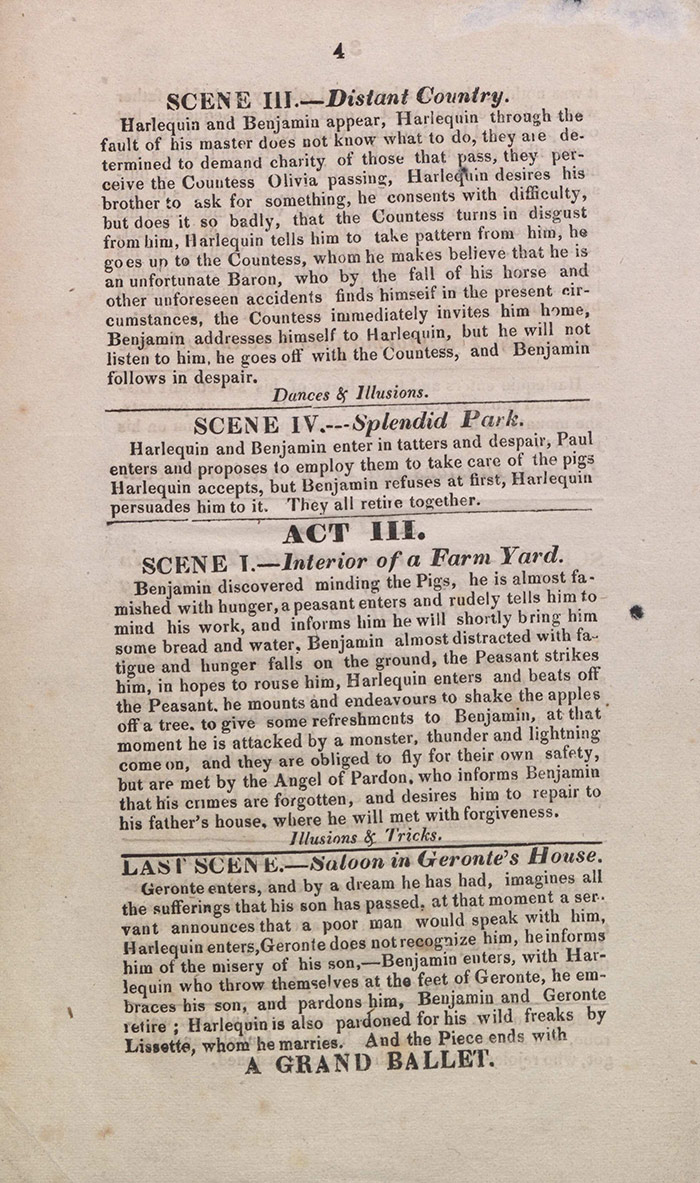

(f.358v)

SCENE III. ─ Distant Country.

Harlequin and Benjamin appear, Harlequin through the fault of his master does not know what to do, they are determined to demand charity of those that pass, they perceive the Countess Olivia passing, Harlequin desires his brother to ask for something, he consents with difficulty, but does it so badly, that the Countess turns in disgust from him, Harlequin tells him to take pattern from him, he goes up to the Countess, whom he makes believe that he is an unfortunate Baron, who by the fall of his horse and other unforeseen accidents finds himself in the present circumstances, the Countess immediately invites him home, Benjamin addresses himself to Harlequin, but he will not listen to him, he goes off with the Countess, and Benjamin follows in despair.

Dances & Illusions.

SCENE IV. ─ Splendid Park.

Harlequin and Benjamin enter in tatters and despair, Paul enters and proposes to employ them to take care of the pigs Harlequin accepts, but Benjamin refuses at first, Harlequin persuades him to it. They all retire together.

ACT III.

SCENE I. ─ Interior of a Farm Yard.

Benjamin discovered minding the Pigs, he is almost famished with hunger, a peasant enters and rudely tells him to mind his work, and informs him he will shortly bring him some bread and water, Benjamin almost distracted with fatigue and hunger falls on the ground, the Peasant strikes him, in hopes to rouse him, Harlequin enters and beats off the Peasant, he mounts and endeavours to shake the apples off a tree, to give some refreshments to Benjamin, at that moment he is attacked by a monster, thunder and lightning come on, and they are obliged to fly for their own safety, but are met by the Angel of Pardon, who informs Benjamin that his crimes are forgotten, and desires him to repair to his father’s house, where he will meet with forgiveness.

Illusions & Tricks.

LAST SCENE. ─ Saloon in Geronte’s House.

Geronte enters, and by a dream he has had, imagines all the sufferings that his son has passed, at that moment a servant announces that a poor man would speak with him, Harlequin enters, Geronte does not recognize him, he informs him of the misery of his son, ─ Benjamin enters, with Harlequin who throw themselves at the feet of Geronte, he embraces his son, and pardons him, Benjamin and Geronte retire; Harlequin is also pardoned for his wild freaks by Lissette, whom he marries. And the Piece ends with

A GRAND BALLET.

Performance, publication, and reception

The published text was submitted to the Examiner in November 1828 for performance in the Argyll Rooms on Regent Street, the little theatre started by Henry Greville and licensed by the Lord Chamberlain in 1807 (a full history and description of the Argyll Rooms can be found in the London Survey). This harlequinade was one of a number of descriptive programmes submitted on behalf of Messrs Maffey puppet company but was the only one refused a licence. The title page is inscribed ‘This piece (founded on Scripture) the Ld Chamberlain will not Licence’.

The Maffey family were a French puppeteering dynasty who had been operating from at least the late eighteenth century in Paris. They performed in Spain in 1817 and in America in 1817-18. Maffey settled in Paris in 1820 and established a theatre named Petit Lazari. In 1824 the troupe began travelling again and performed in England a number of times with great success.

According to Speaight, the 1828-29 run in London began in September and ran until May, with eighteen different plays—often a harlequinade—on display, usually a new one every week. Each night’s entertainment usually included a ballet and an animated view of famous sieges or battles. Key to their success were the transformations enabled by Harlequin’s wand (and the mechanical apparatus enabling them) such as the transformation of a table into a flying dragon. Tickets cost between 1s and 3s. (Speaight, 239-40)

Even The Times, which could never be accused of being a champion for Franophone cultural, was much delighted by the puppeteers’ skill and imaginative power:

There is a very ingenious exhibition of fantoccini at the Argyll Rooms, in which, under the influence of Messrs. Maffey, a collection of rags and wire are made to imitate human actors and actresses so closely, that some of their animated competitors may blush at the resemblance. They play a kind of parody on the Festin de Pierre, the pantomimical parts of which are done with uncommon effect; and the dialogue, although carried on in very bad French and worse English, is excessively amusing. The Arlequin of Messrs. Maffey is quite as comical as Pellegrini in Leperello. His humour is of the coarser kind; and his jokes, although they might fail if they were played by a living actor, are irresistible when they come from his wooden carcass […] The whole of the entertainment is very clever, very amusing, and well deserving of encouragement. (The Times, 22 November 1828)

The Gentleman’s Magazine 144 (November 1828) was also impressed, describing the performances as ‘wonderfully clever and varied’ and insisted they London was witnessing ‘the triumph of pantomimical and automatical talent’. It concluded that ‘many an excellent trick could be borrowed from these metamorphoses of Messrs. Maffey’s to enrich our Christmas pantomime’ (460)

As the title page notes, the performance was in the French language and this was received positively rather than as posing a problem:

Messrs. Maffey, in the sketch which they have published of their entertainment, intimate that “it is impossible they could have translated this piece into the English language,” and we congratulate them on the impossibility. It would have been insufferable if they had translated it; but it is quite delightful as they give it. (The Times, 22 November 1828).

Commentary

This is a straightforward case of prohibition on the grounds of religion. Nonetheless, despite the relative lack of complexity in this case it is an important inclusion to this resource, not least because of the remarkable longevity of the harlequin play to the British (and European) theatrical tradition.

Harlequinades were a staple of British theatre from the 1720s. Inspired by the commedia dell’arte tradition, the harlequinade was a slapstock variant and typically featured the characters of Harlequin, Columbine, Pantaloon, a Clown, and Pierrot. Harlequin is in love with Columbine; their union is threatened by her father, Pantaloon, in league with the Clown. Pierrot is a servant figure. The drama is usually resolved by some magical transformation effected by Harlequin (through his magic—and phallic—wand) that allows him and Columbine to be together. Dancing, mime, mechanical effects were all important components of this visually spectacular episodes of riot, mischief and desire.

The harlequinade became firmly rooted in Britain largely as a result of John Rich, who played the eponymous role from about 1717. He had an enormous hit with The Necromancer, or, Harlequin Doctor Faustus (Lincoln’s Inn Fields, 1723); according to John O’Brien, this had more than 300 performances before Rich’s retirement in 1753 (O’Brien, 96). More immediately, Harlequin Doctor Faustus prompted a wave of such harlequin plays in the 1720s and 1730s and made the genre a quintessential part of the British theatrical experience.

The refusal to licence a puppet show in the French language, based somewhat loosely on a Biblical story is important evidence of just how sensitive the early nineteenth-century stage was on the question of religion. We can see in earlier examples in this resource, such as The Universal Register Office (1761) and Killing No Murder (1809), that this is quite consistent through our entire period. However, although John Larpent’s touchiness on the question of Methodism was quite well known, it is perhaps George Colman the Younger who took the issue most seriously. Examples are far too many to discuss here (readers can get a good sense from John Russell Stephen’s chapter on religion) but perhaps his testimony at the Select Committee on Dramatic Literature (1832) will suffice. In this snippet, perhaps the most entertaining in the report, one can all too easily imagine the increasing tone of incredulity from the questioner(s):

The Committee have heard of your cutting out of a play the epithet “angel,” as applied to a woman?—Yes, because it is a woman, I grant, but it is a celestial woman. It is an allusion to the scriptural angels, which are celestial bodies. Every man who has read his Bible understands what they are, or if he has not, I will refer him to Milton.

Do you recollect the passage in which that was struck out?—No, I cannot charge my memory with it. I do not recollect that I struck out an angel or two, but most probably I have at one time or other.

Milton’s angels are not ladies?—No, but some scriptural angels are ladies, I believe. If you will look at Johnson’s Dictionary, he will tell you they are celestial persons, commanded by God to interfere in terrestrial business.

Supposing you are to leave the word “angel” in a play or farce, will you state your opinion as to what effect it would have on the public mind?—It is impossible for me to say what effect it would have; I am not able to enter into the breasts of every body who might be in a gallery, pit, or boxes.

But you must have some reason for erasing it?—Yes, because it alludes to a scriptural personage.

Must an allusion to Scripture have an immoral effect?—I conceive all Scripture is much too sacred for the stage, except in very solemn scenes indeed, and that to bring things so sacred upon the stage becomes profane. (Select Committee Report, 59-60)

Colman’s zeal was not terribly out of kilter with the nineteenth-century zeitgeist: Dion Boucicault told the 1866 Committee on Theatres and Regulations that an audience hissed a line from his play ‘I came to scoff, but I remained to pray’. The line is from Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village but they thought it came from the Bible (Stephens, 100).

Further reading

‘Argyll Rooms, Little Argyll Street’ in Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster Part 2 (London: London County Council, 1963), 284-327.

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp284-307#h3-0014

Select Committee on Dramatic Literature (London: House of Commons, 1832).

[available on the HathiTrust website]

Erkki Huhtamo, ‘Mechanisms in the Mist: A Media Archaeological Excavation of Mechanical Theater’ in Nele Wynants (ed), Media Archaeology and Intermedial Performance: Deep Time of the Theatre (Cham: Palgave Macmillan, 2019), 60.

John O’Brien, Harlequin Britain: Pantomime and Entertainment, 1690-1760 (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004).

George Speaight, The History of the English Puppet Theatre (New York: John de Graff, 1955).

[available on archive.org]

John Russell Stephens, The Censorship of English Drama 1824-1901 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), esp. the chapter ‘Religion and the Stage’