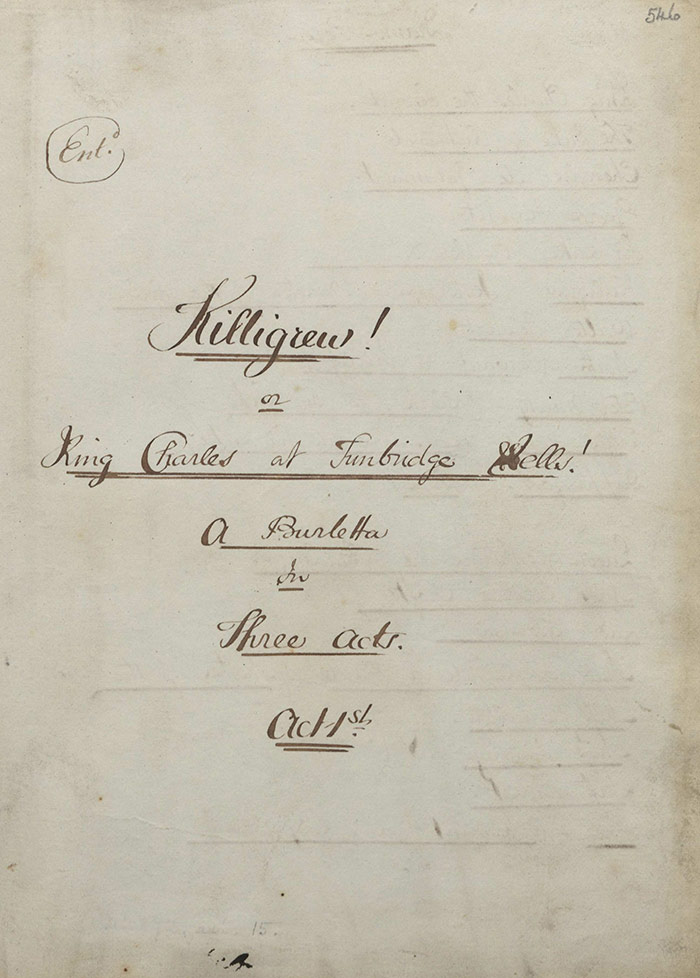

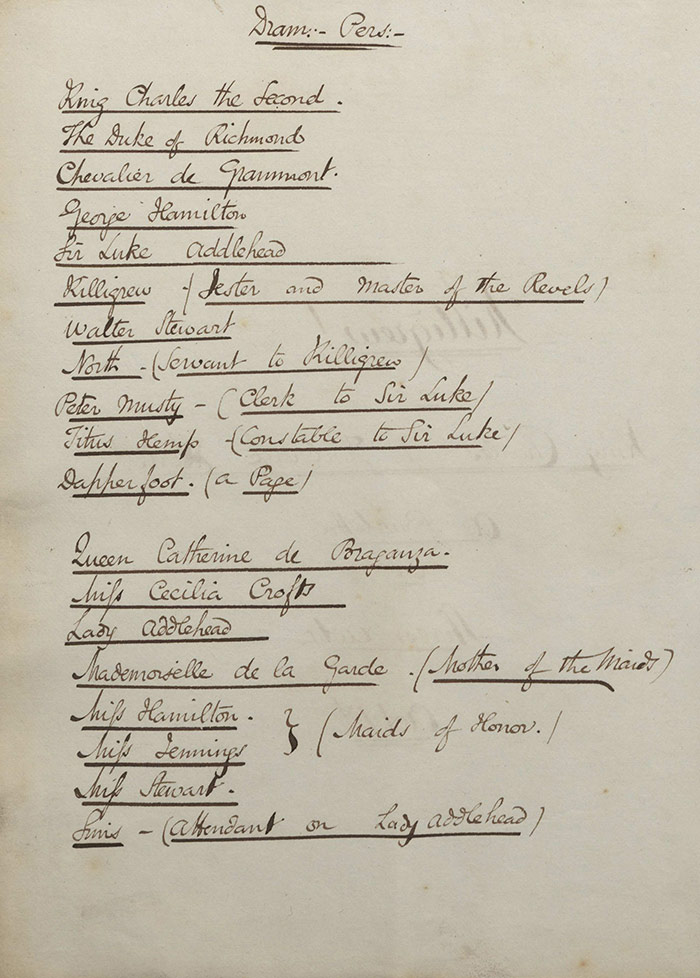

Killigrew! Or, King Charles at Tunbridge Wells! (1825) BL ADD MS 42872, ff. 546-604

Author

The authorship is uncertain. However, reviewers in The Examiner (16 October 1825) and The Drama (November 1825) assumed it was William Thomas Moncrieff (see Tom and Jerry).

Plot

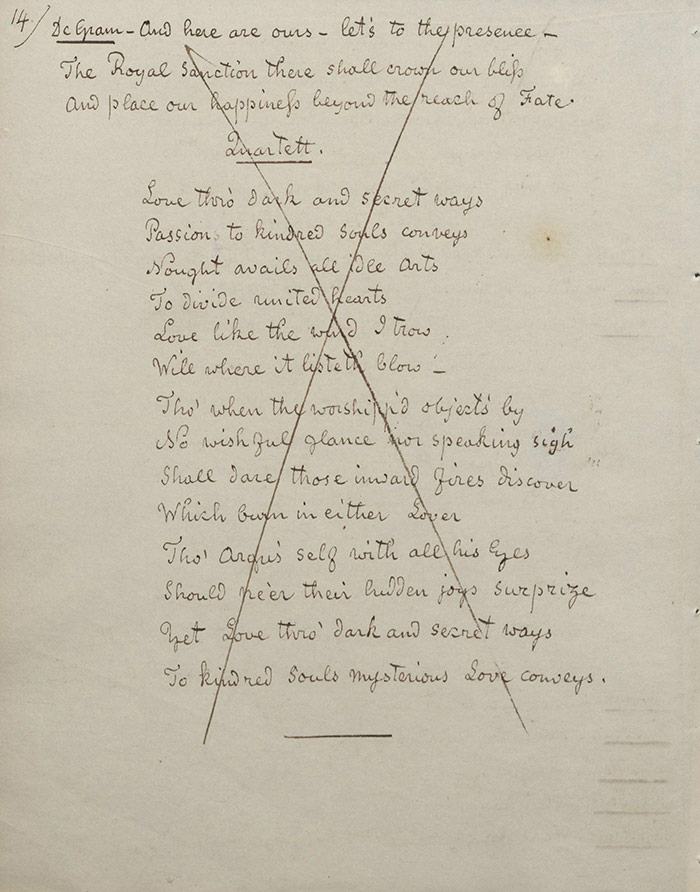

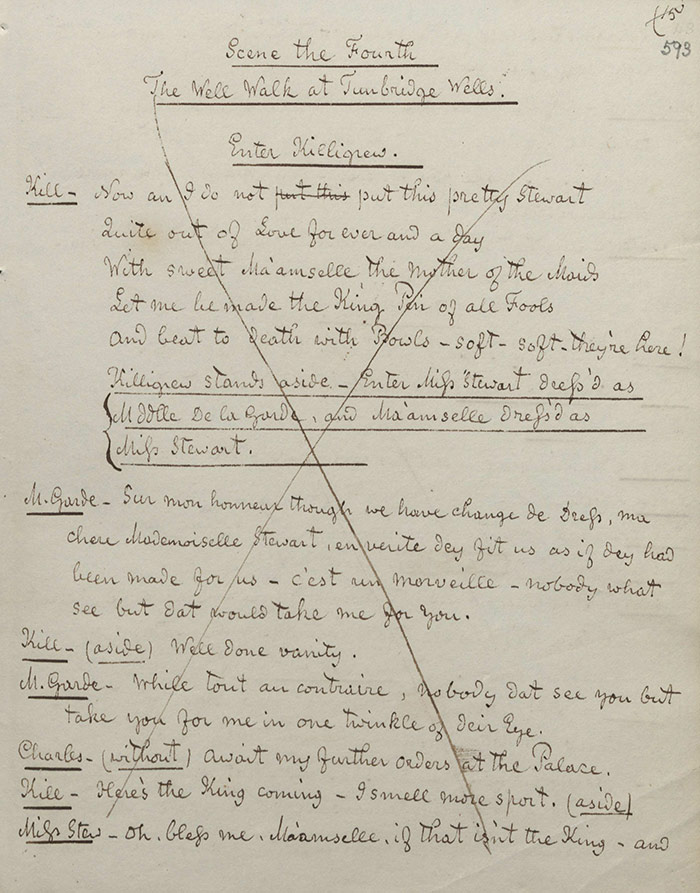

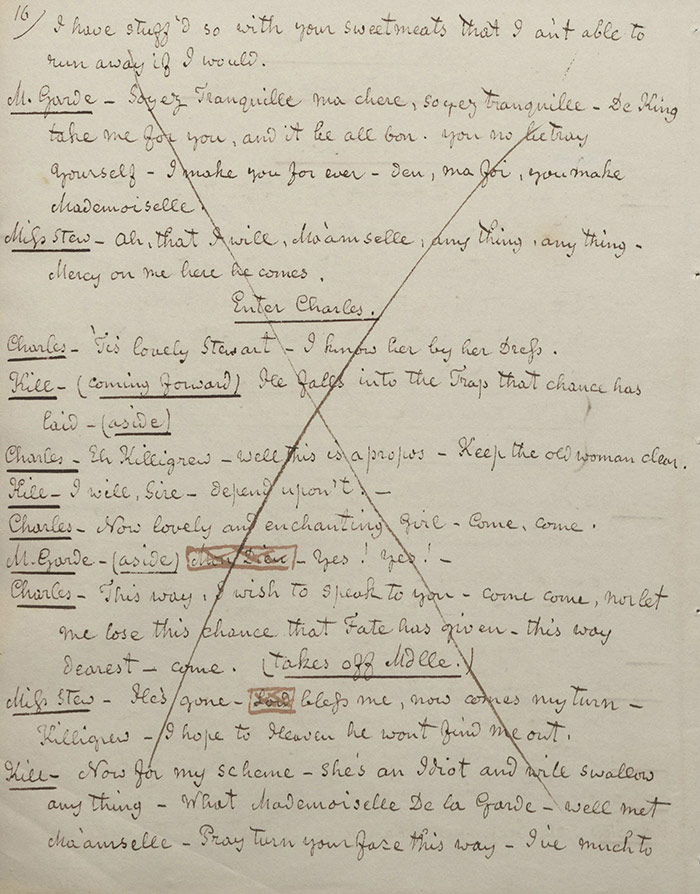

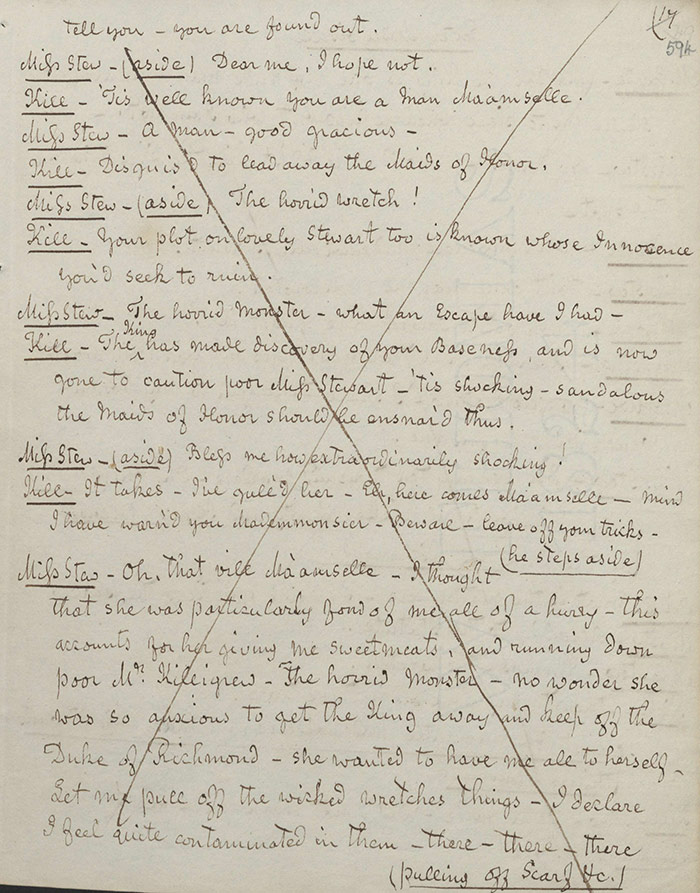

This plot synopsis includes a number of substantial scenes that appear to have been excised by a managerial/authorial hand for dramaturgical rather than censorship reasons (presumably to shorten the play).

Act I

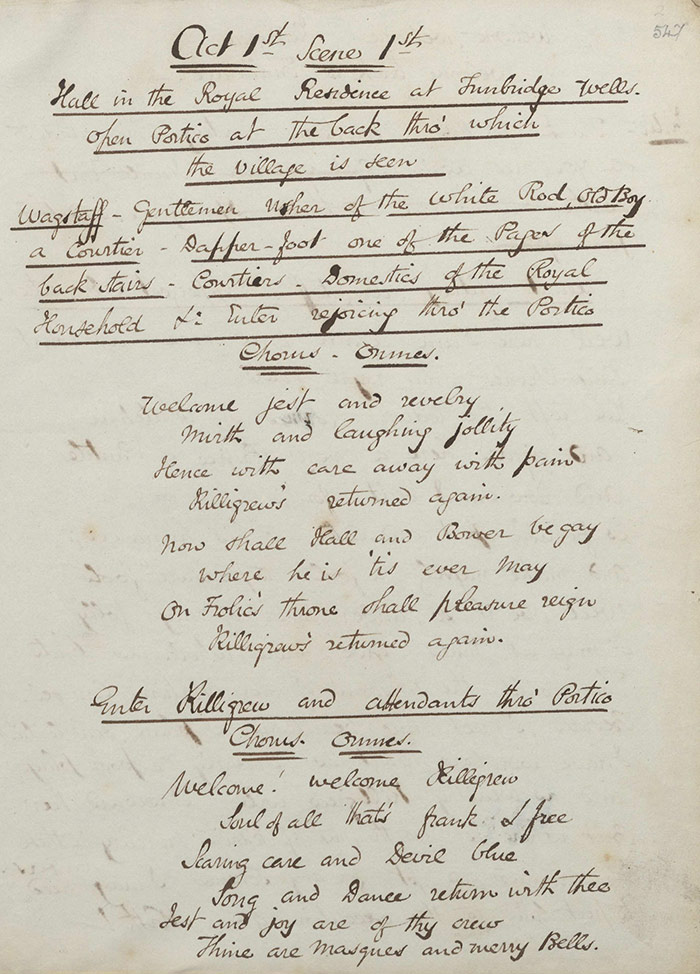

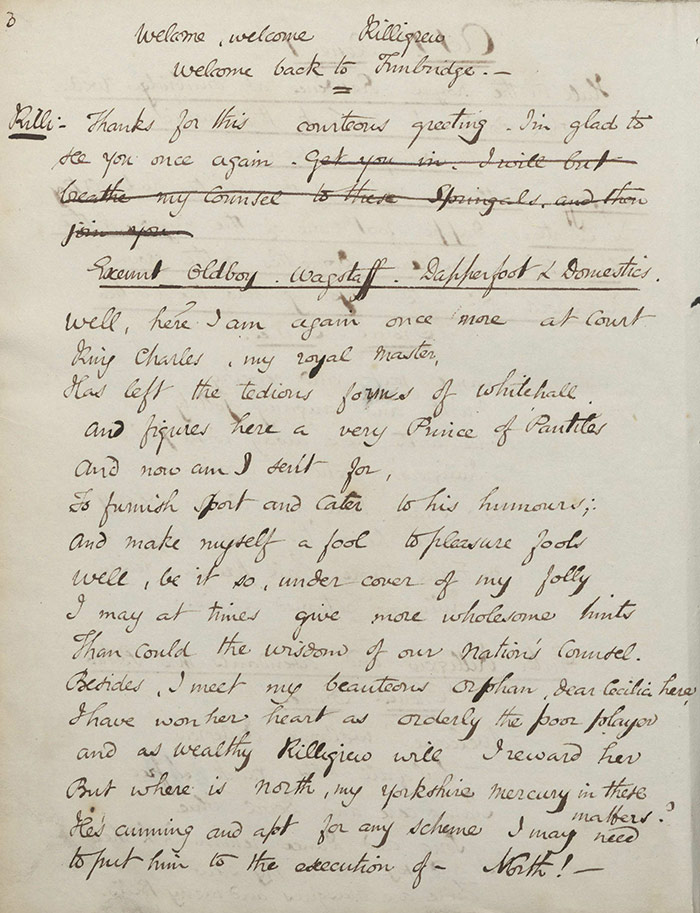

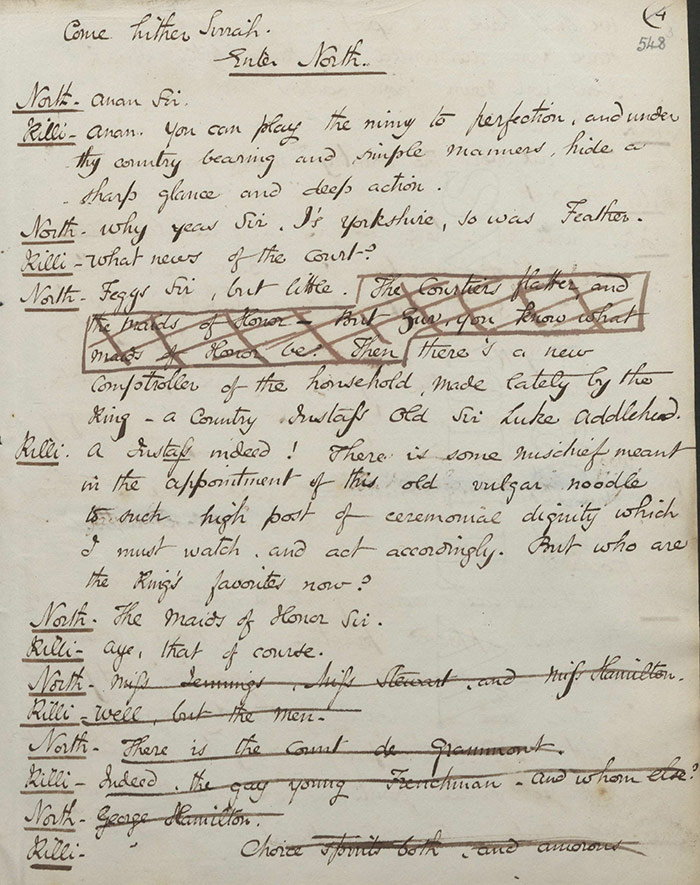

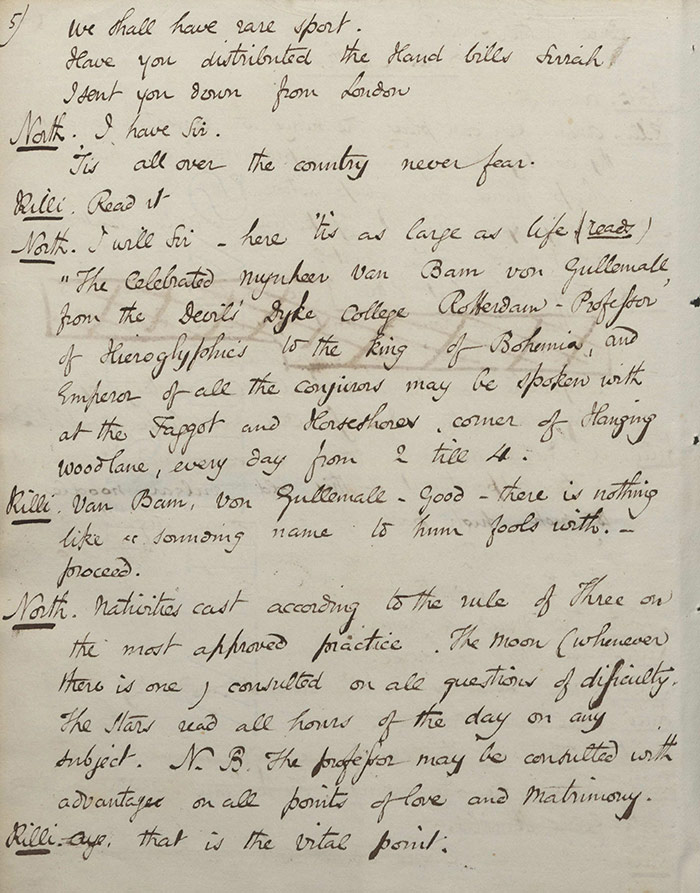

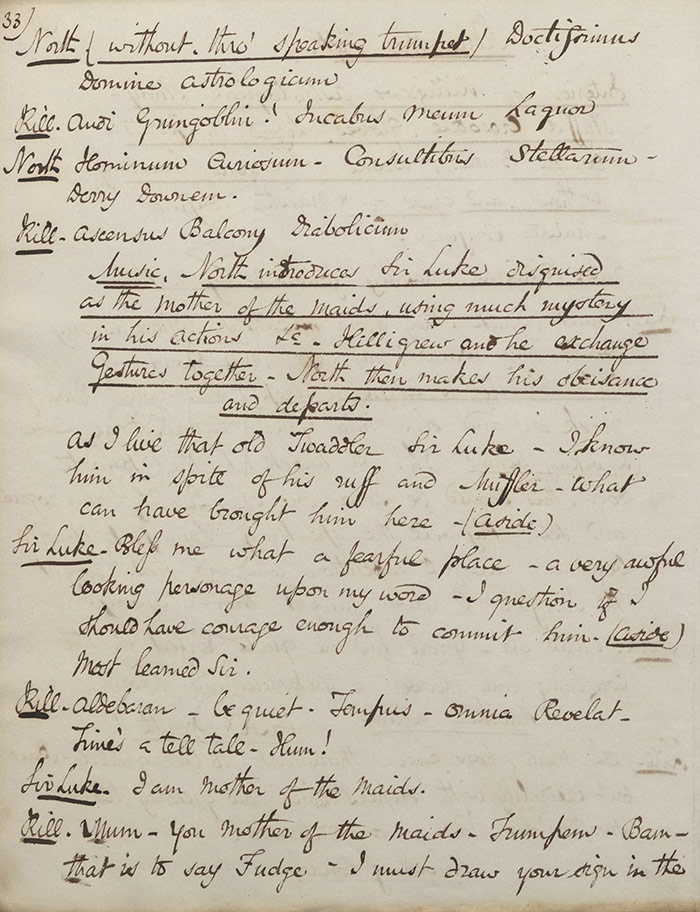

The opening scene sees Killigrew return to the royal residence at Tunbridge Wells at King Charles’s request where an assembled chorus gleefully greets him (f.546r). Killigrew’s servant, North, a Stage Yorkshireman, tells him that Sir Luke Addlehead is the new comptroller of the household. He has also distributed handbills for Killigrew’s scam to disguise himself as a German ‘Professor of Hieroglyphics’ who can be consulted on matters of the heart in order to gull the courtiers and find out their secrets.

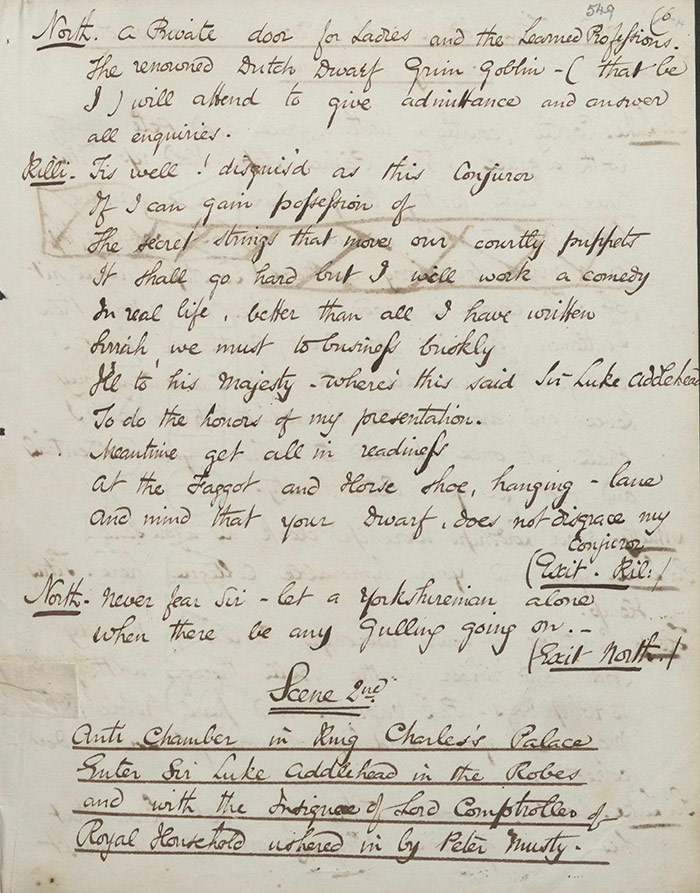

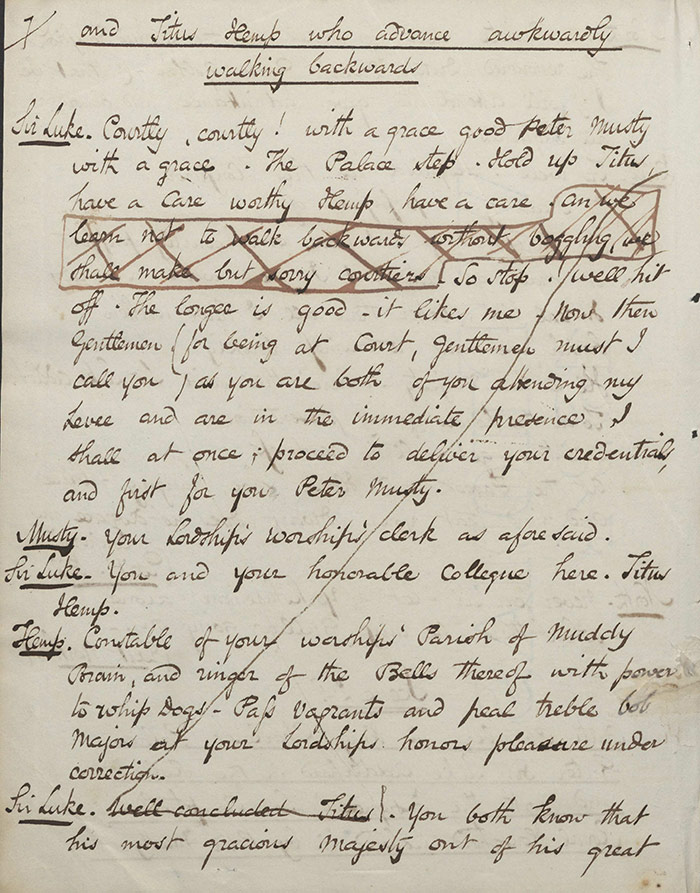

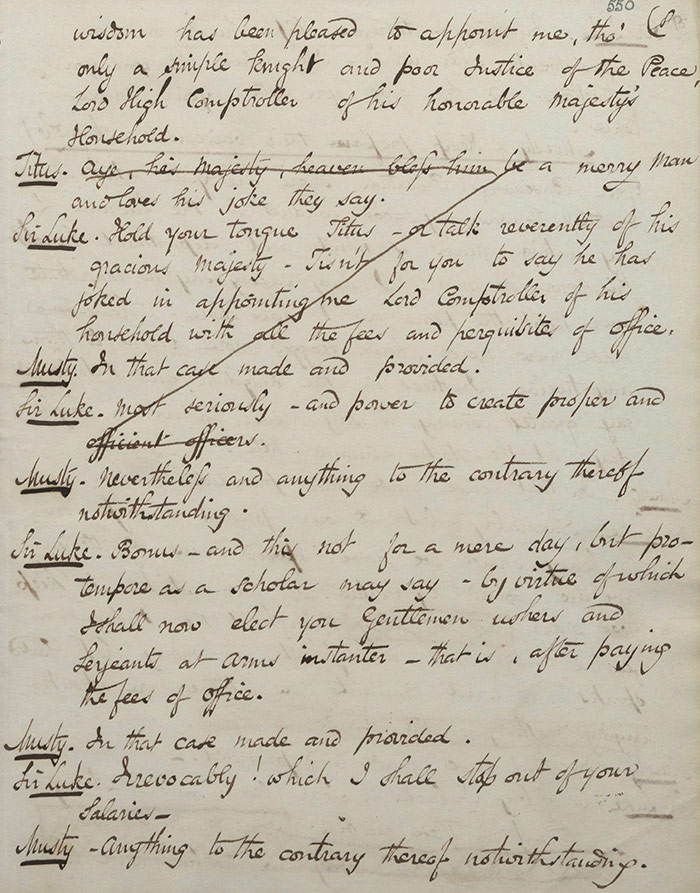

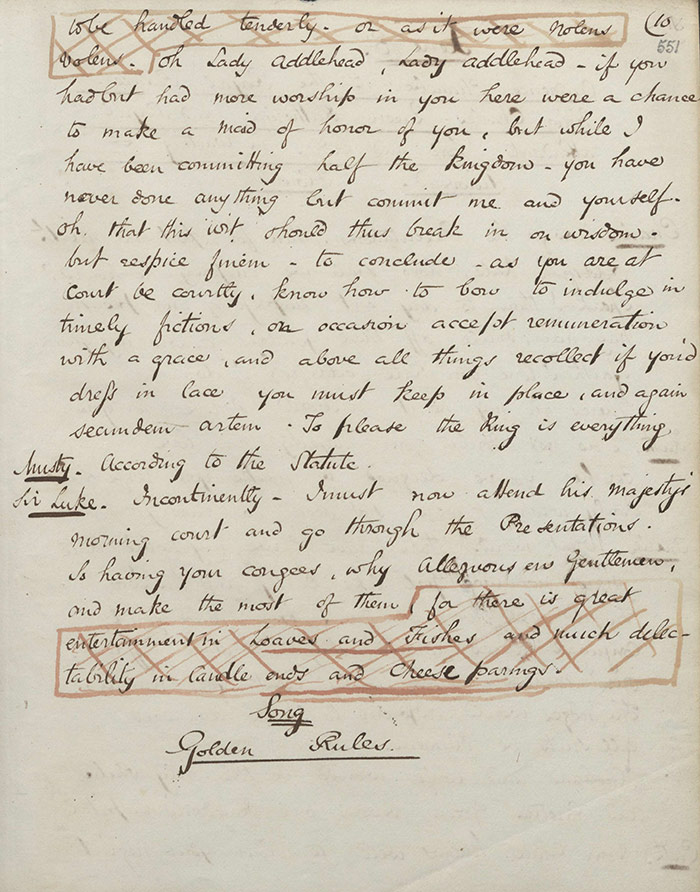

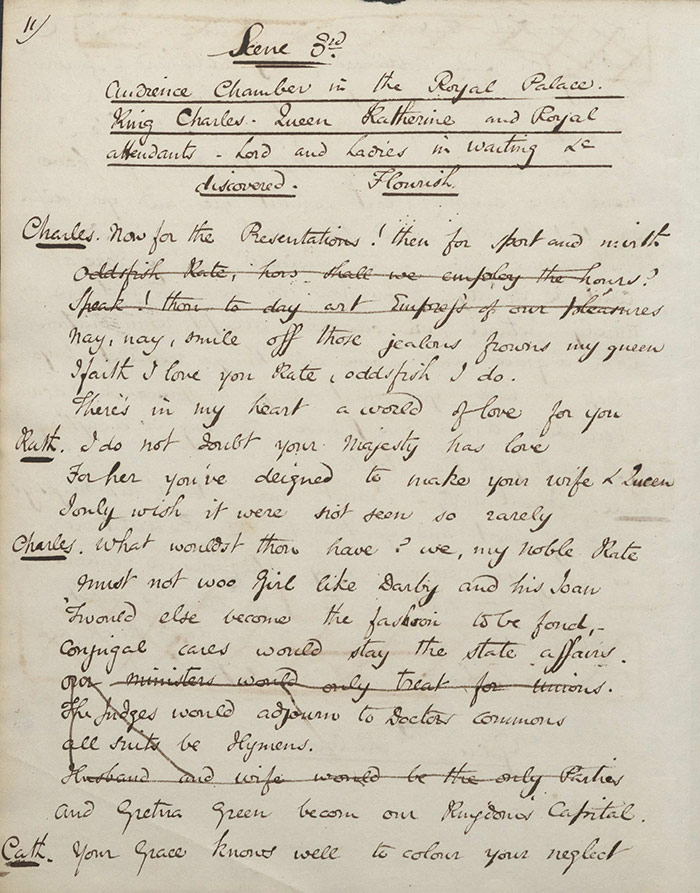

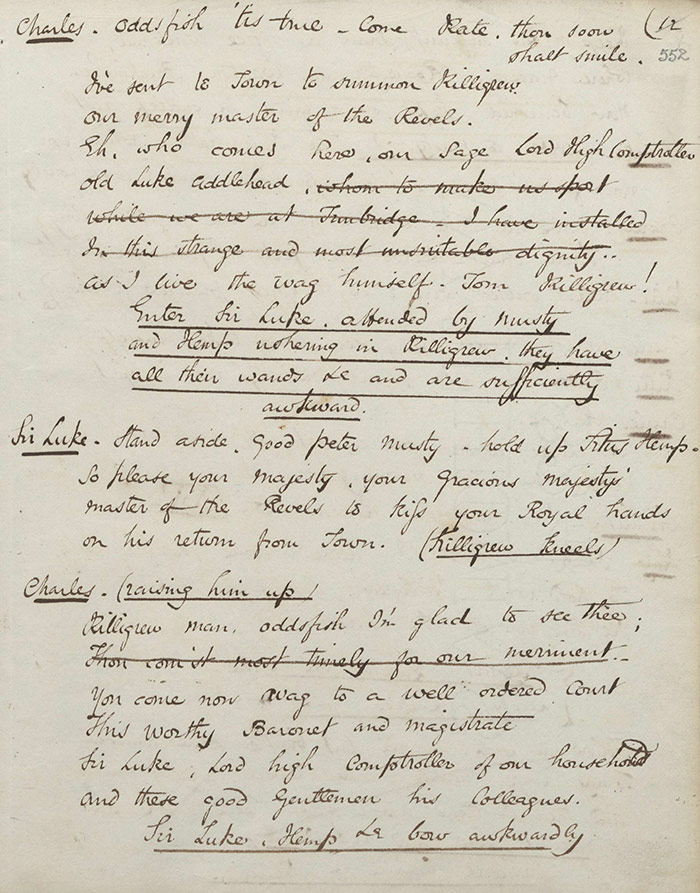

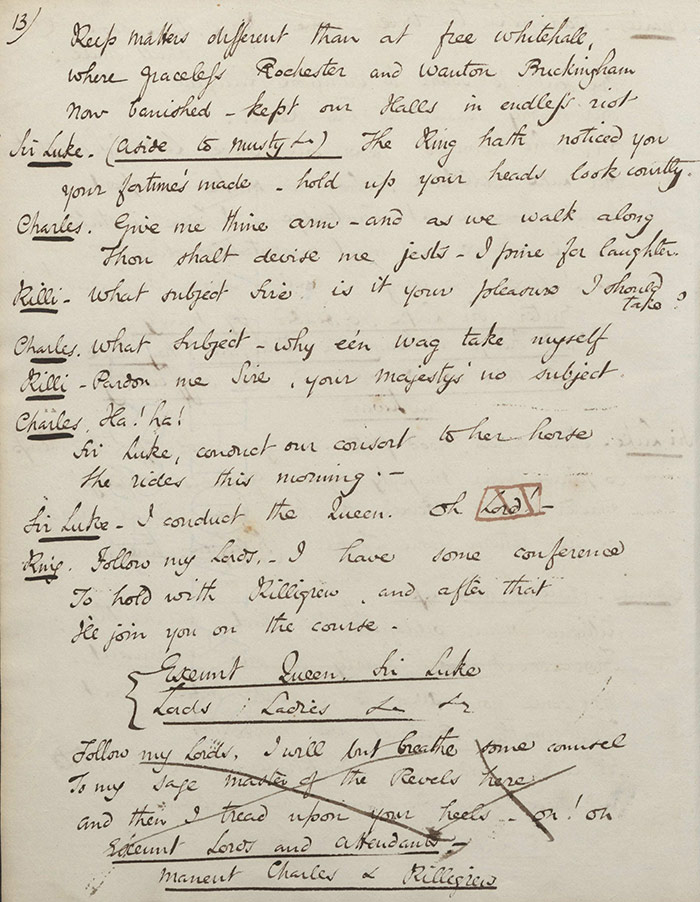

The second scene sees Sir Luke in an antechamber with Peter Musty (his clerk) and Titus Hemp (his constable) (f.549r). The trio show themselves to be pompous and foolish with Sir Luke declaring that they are responsible for keeping order throughout the palace. The third scene is in the King’s audience chamber where he is accompanied by Queen Catherine and attendants (f.551v). The king is eager for amusements and is pleased when Killigrew enters, accompanied by Sir Luke and his men. The king gets Sir Luke to escort the queen to her horse so that he can speak to Killigrew in private. He is having an intrigue with one of the maids of honour, Miss Stewart, and he wants Killigrew to devise a masque which will allow them to exchange protestations of love in front of the whole court.

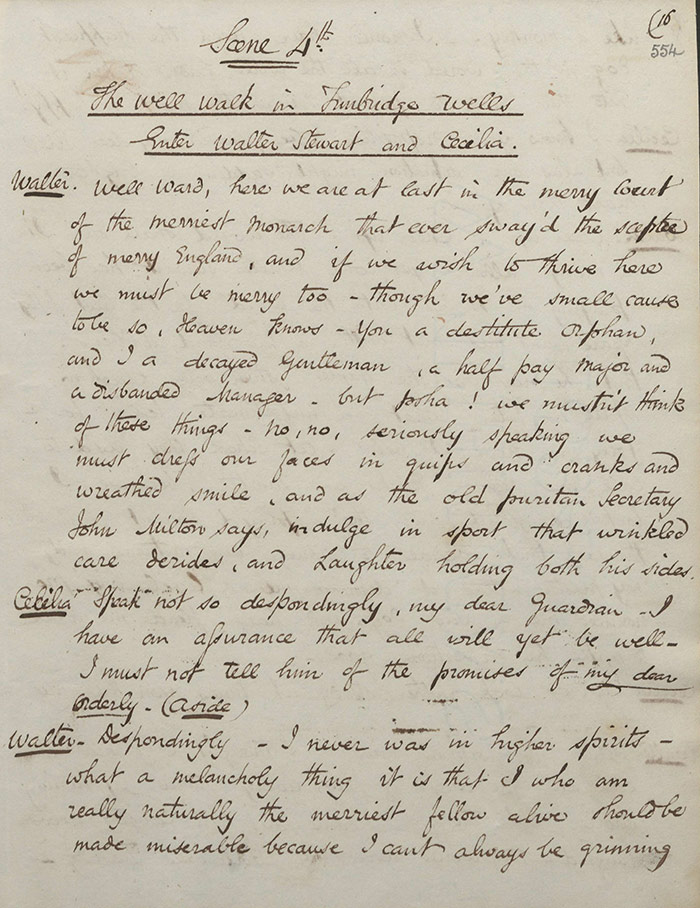

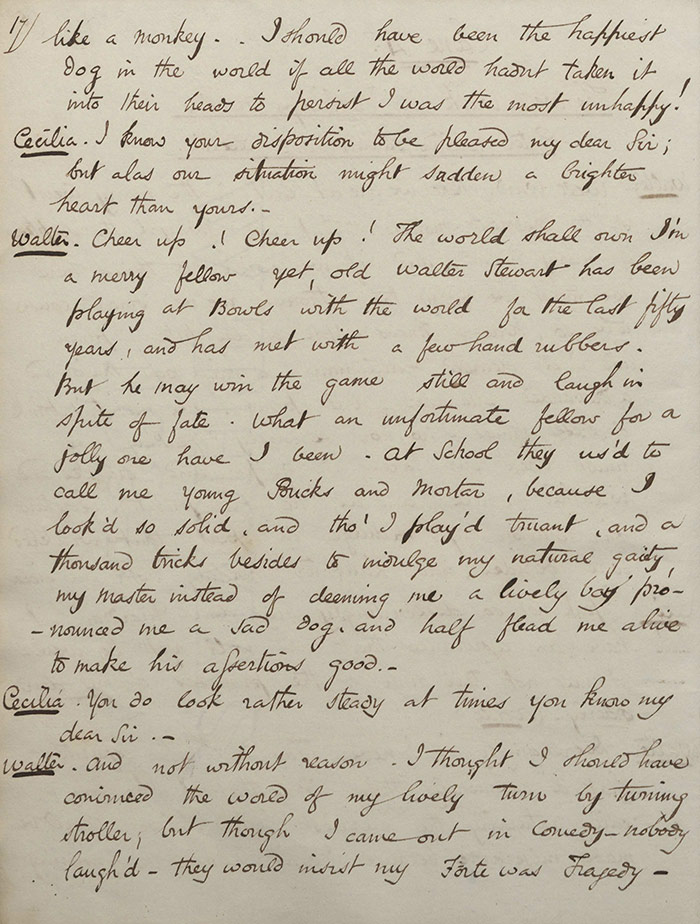

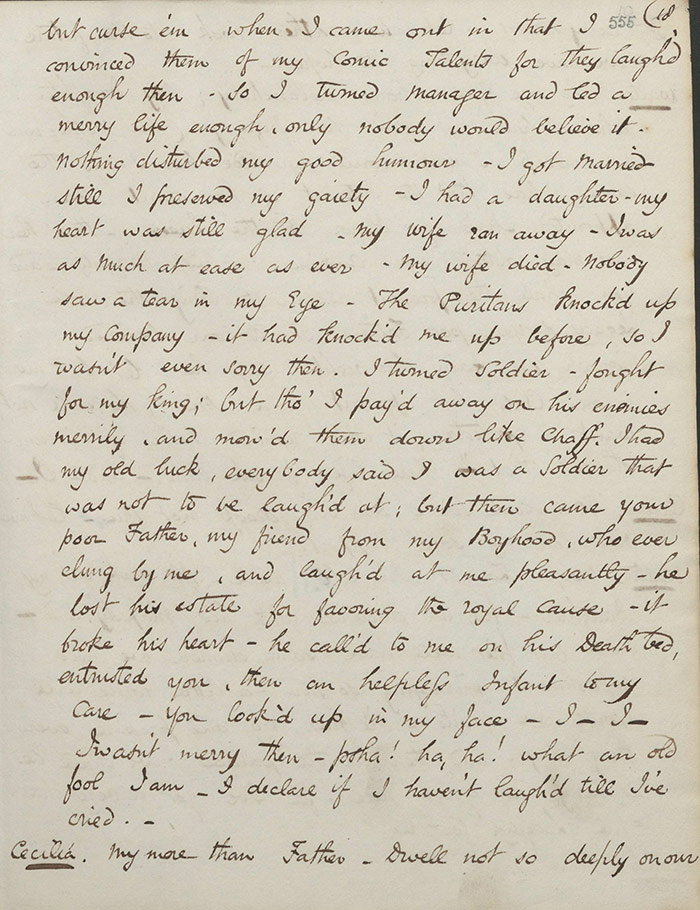

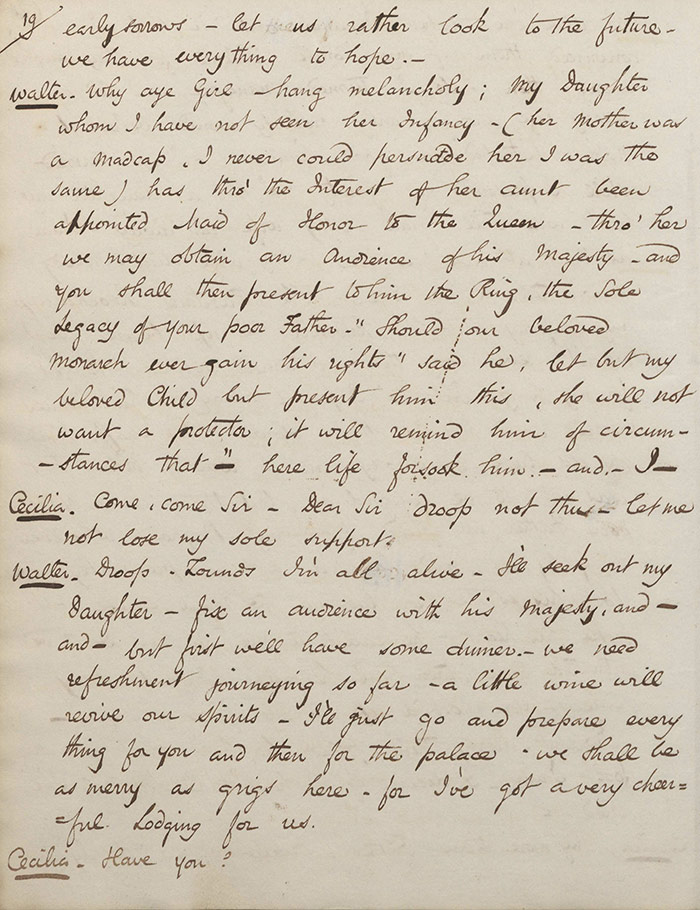

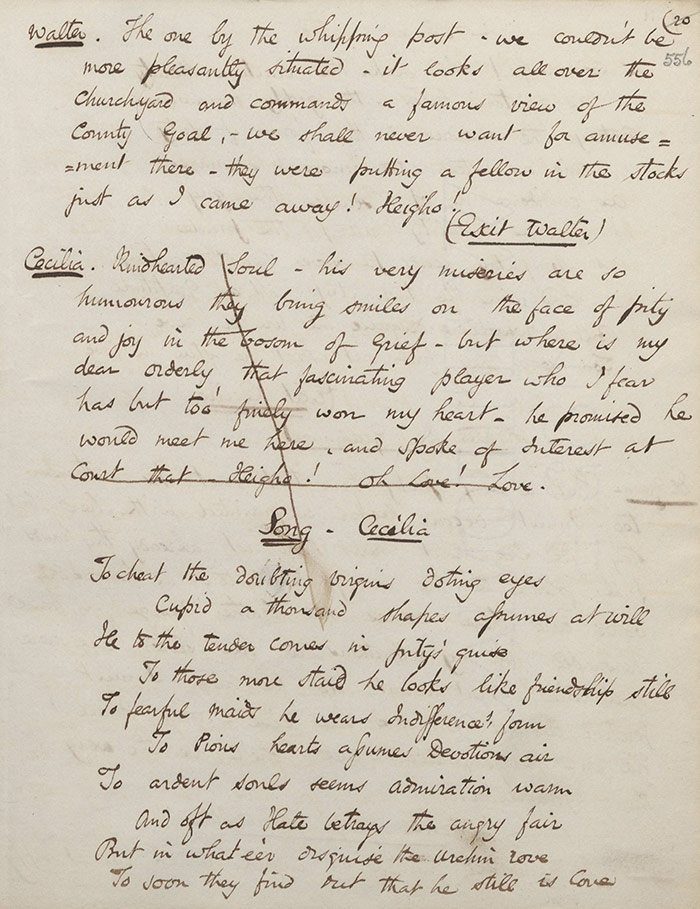

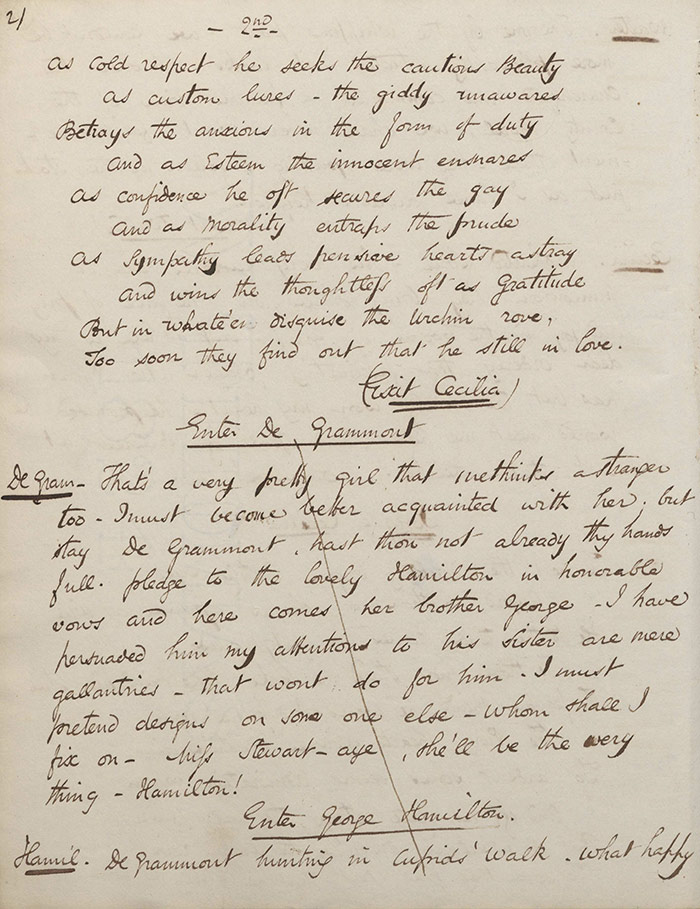

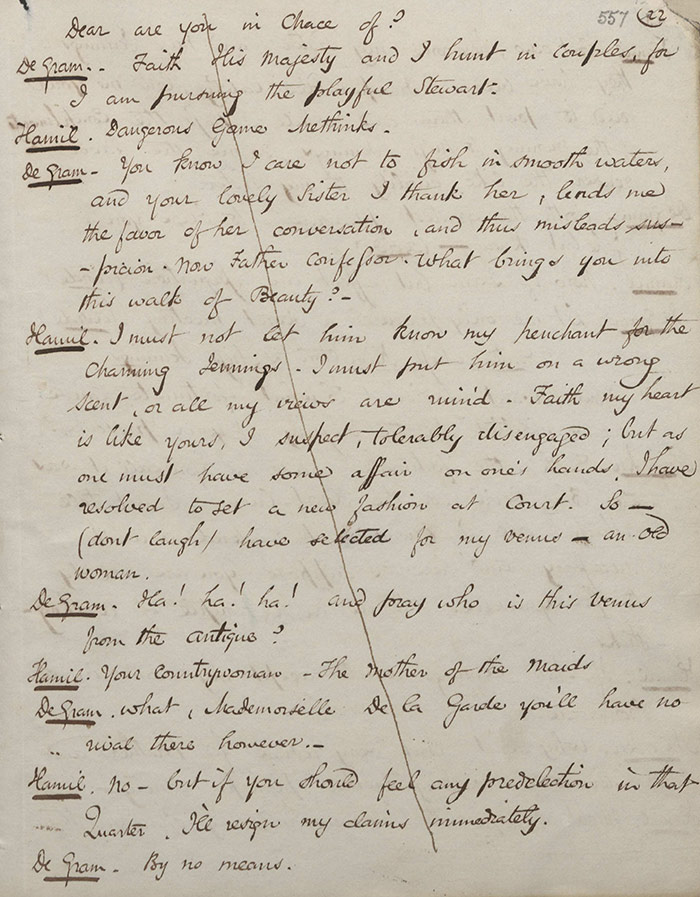

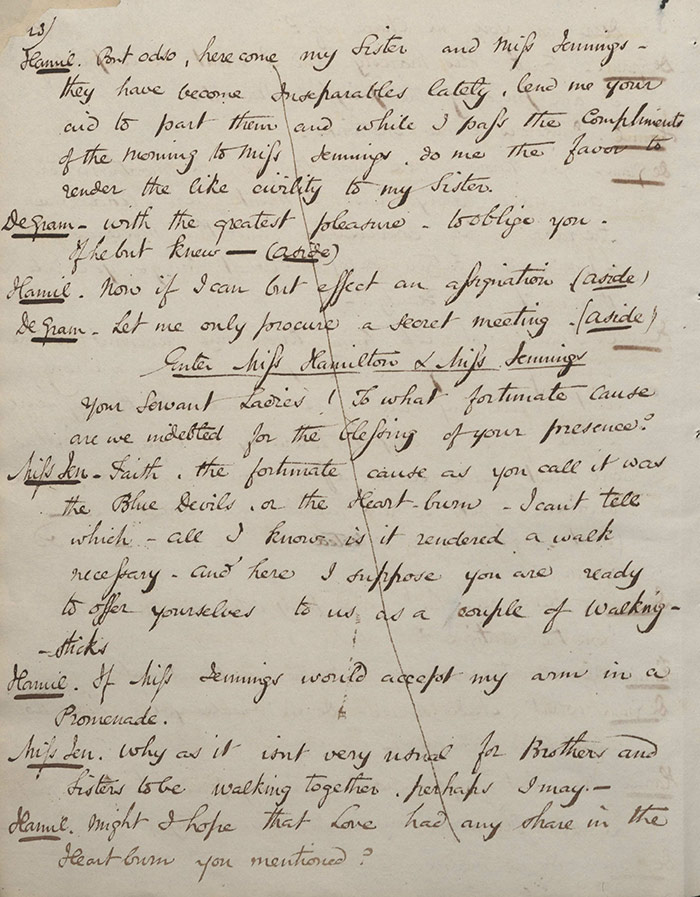

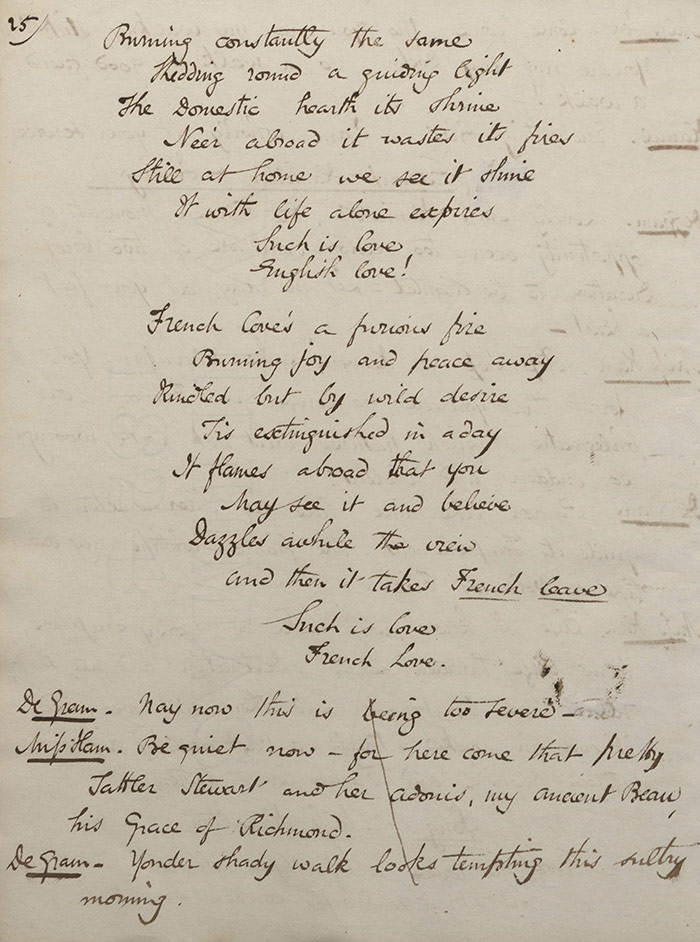

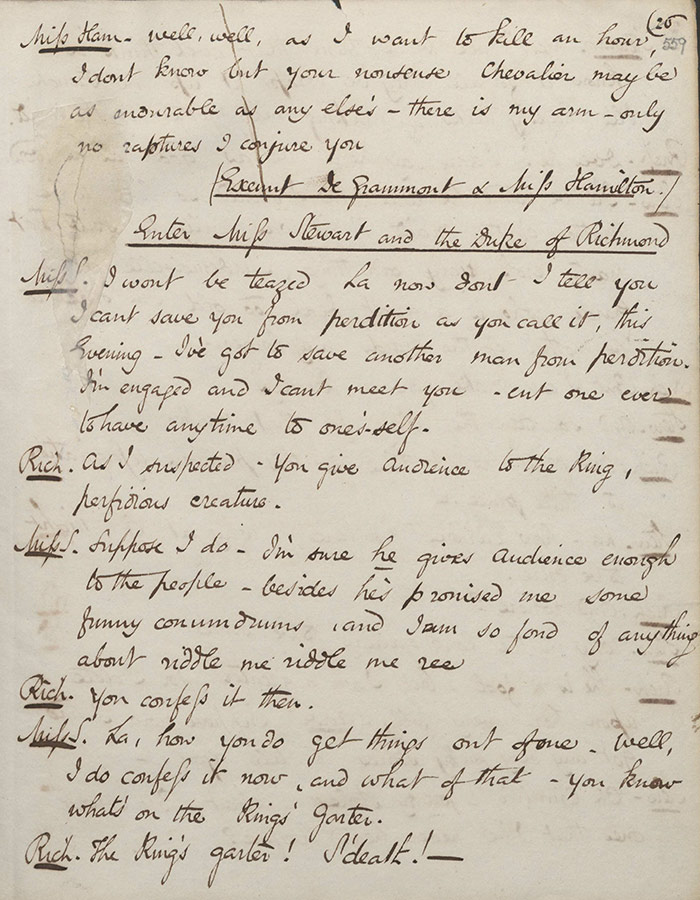

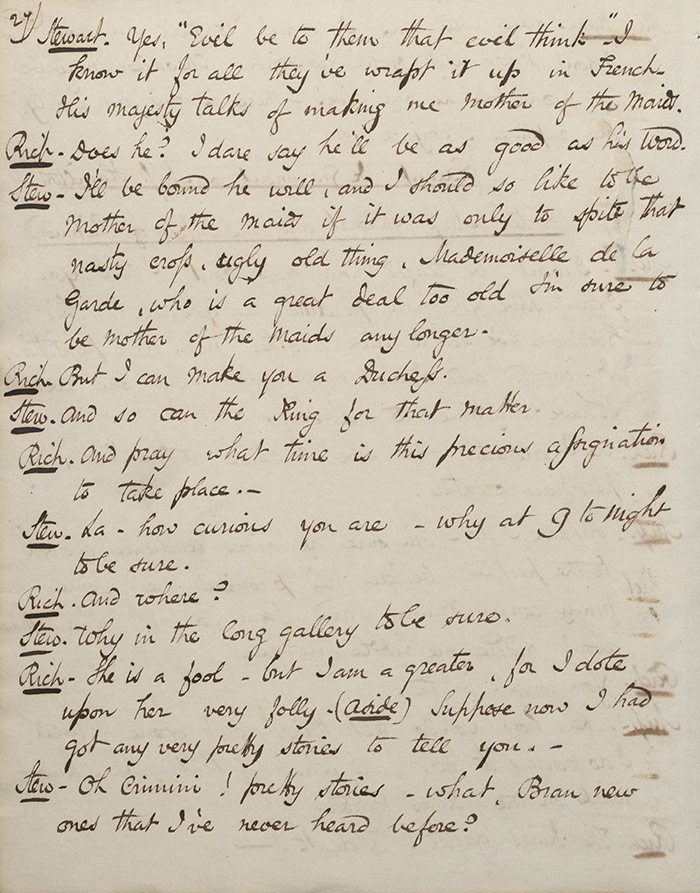

Sir Walter Stewart and his ward Cecilia are discussing how to ensure they prosper in the King’s court (f.554r). Sir Walter reveals his history as a theatre manager who had his company closed by the puritans. He has a plan to seek an audience with the king through his daughter (maid of honour to the queen and whom he has not seen since her infancy) and for Cecilia to present a ring, given her by her father and which will serve as a reminder to the king of his debt to him. She does not tell him of her assurances from her beloved Orderly that all will be well. After she exits, De Grammont and George Hamilton enter. They are determined to hide their true amorous designs from each other: De Grammont pretends that he is in pursuit of Miss Stewart while he is actually courting Hamilton’s sister; Hamilton pretends he is after Mademoiselle de la Garde, mother of the maids of honour, while he is actually in pursuit of Miss Jennings. Miss Jennings and Miss Hamilton duly enter and the men pair off with their desired ladies as Miss Stewart and the Duke of Richmond enter. The Duke is jealous of her forthcoming assignation with the king. He convinces her to meet him half an hour before the king by promising to regale her with fantastic tales of giants and dwarves but is overheard by Mme de la Garde. She is appalled and tells all to Sir Luke. The news puffs up his sense of self-importance and he vows to ‘put a stop to these goings on’ (f.561r). Not knowing the time or place of the assignation, he determines to consult with the German conjuror but disguised as Mme de la Garde, it not being seemly for the Lord High Comptroller to be seen to do such a thing. The queen then enters after he leaves and voices her suspicions of the king: she is determined to find out what is going on as well.

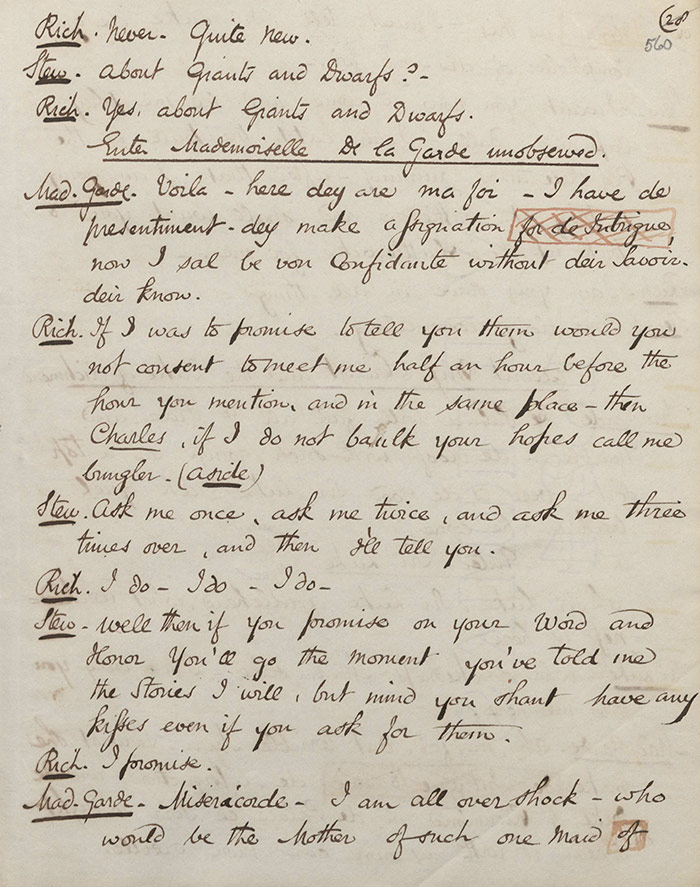

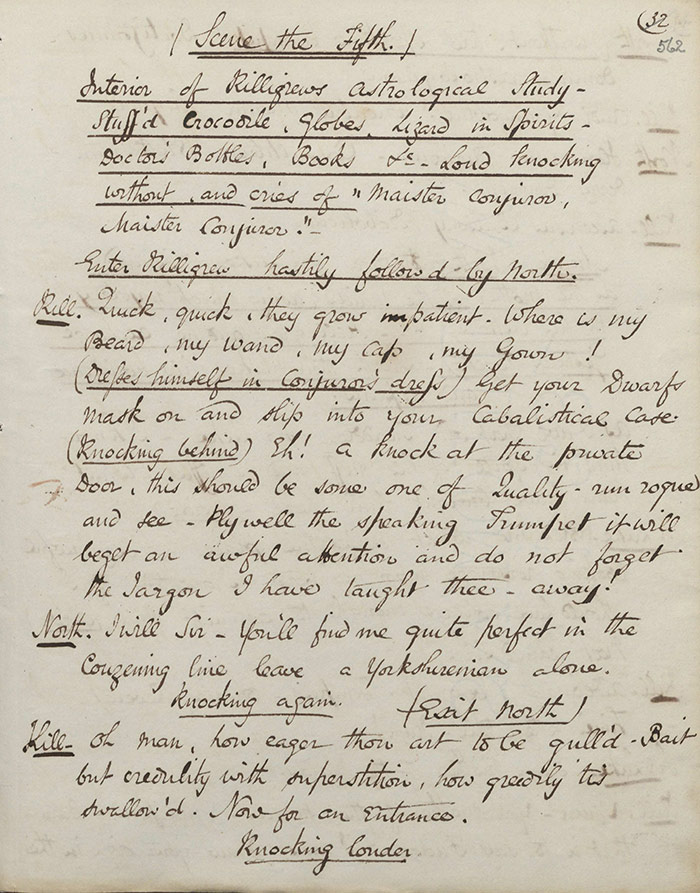

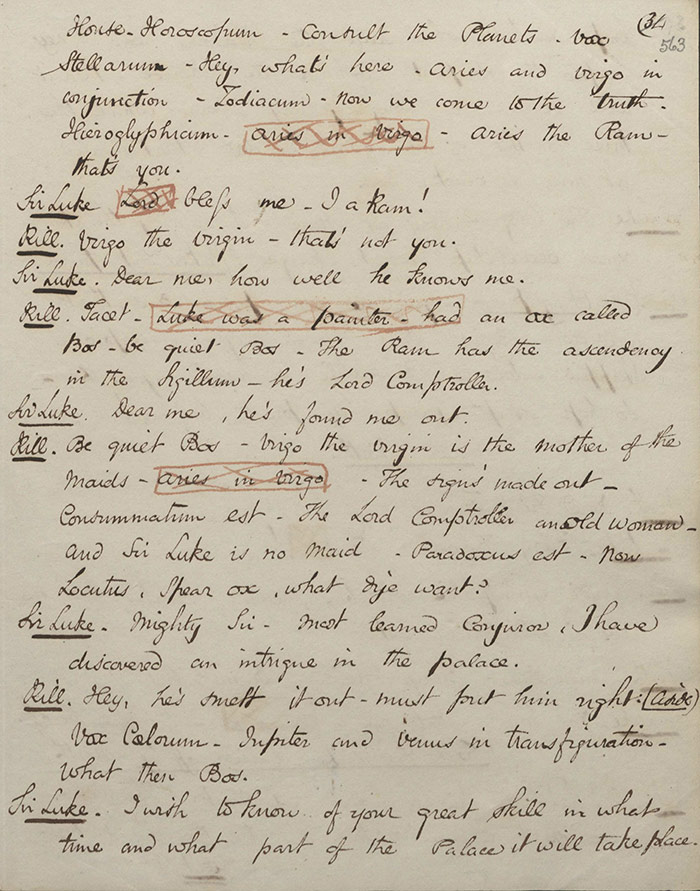

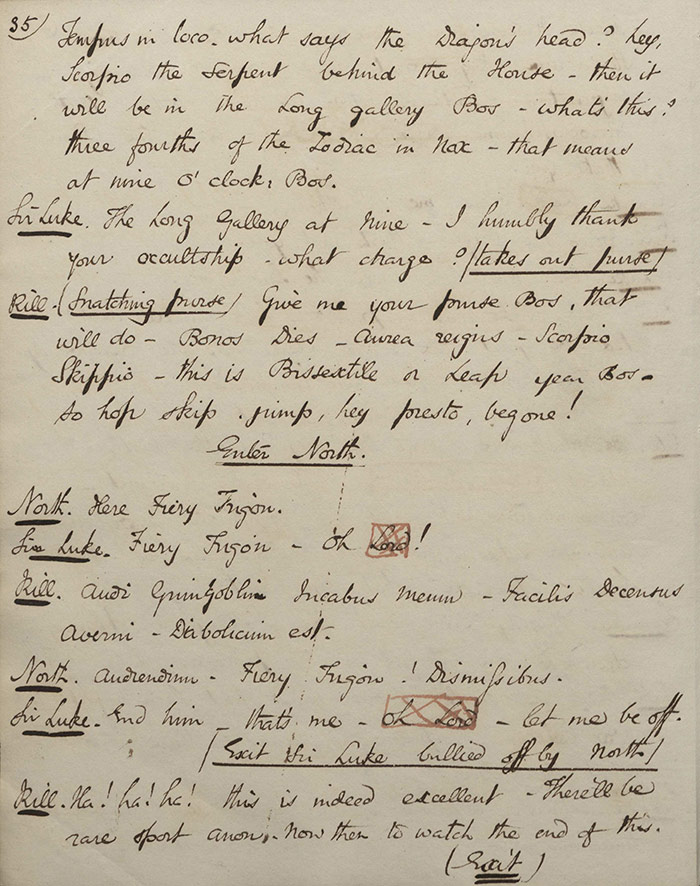

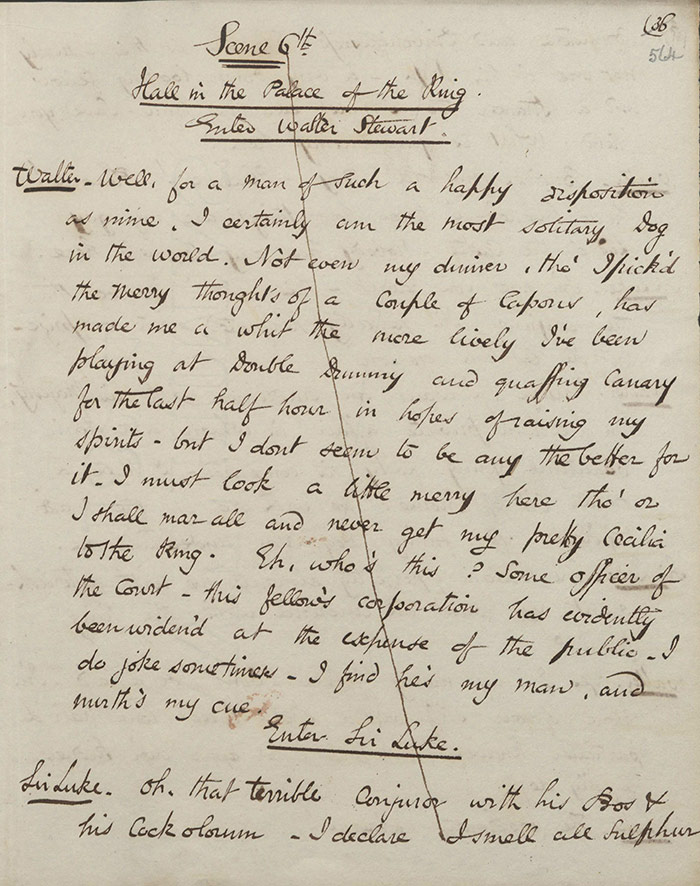

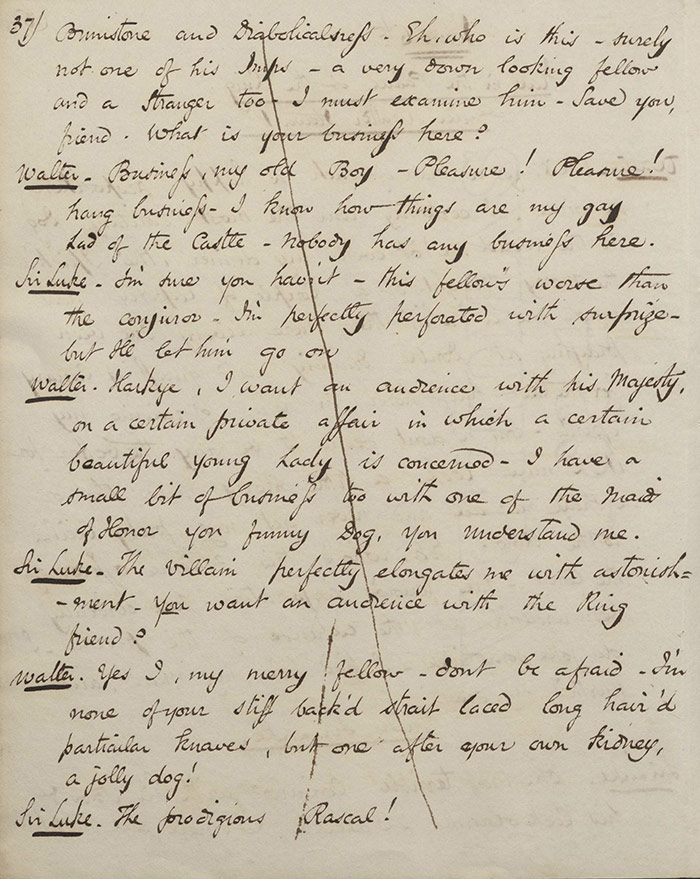

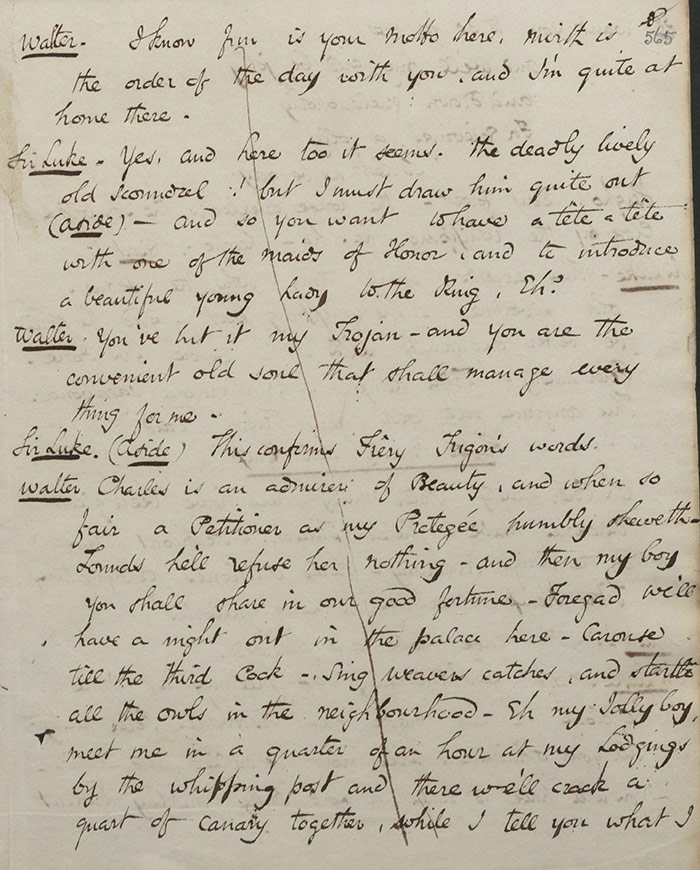

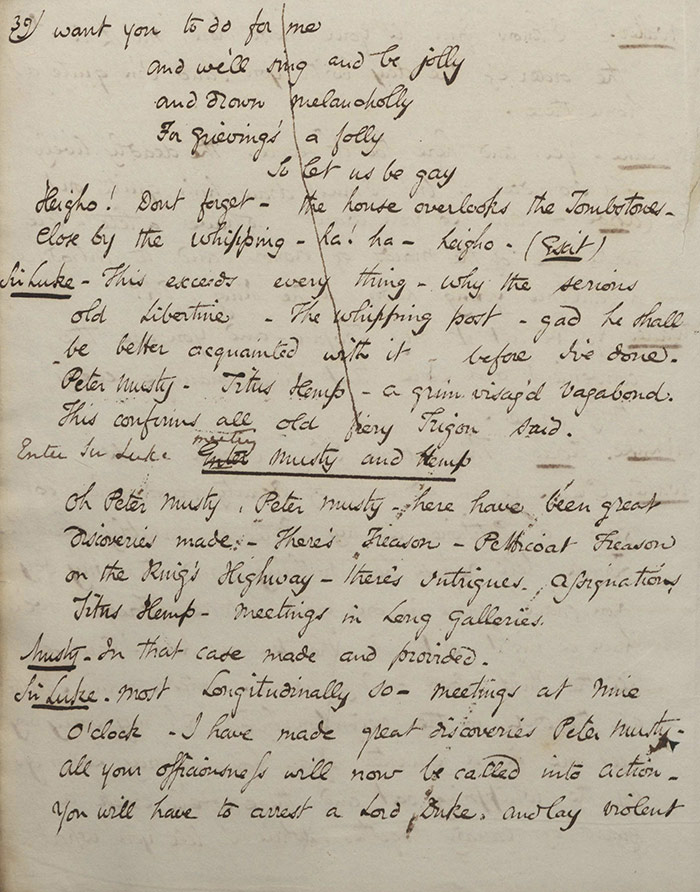

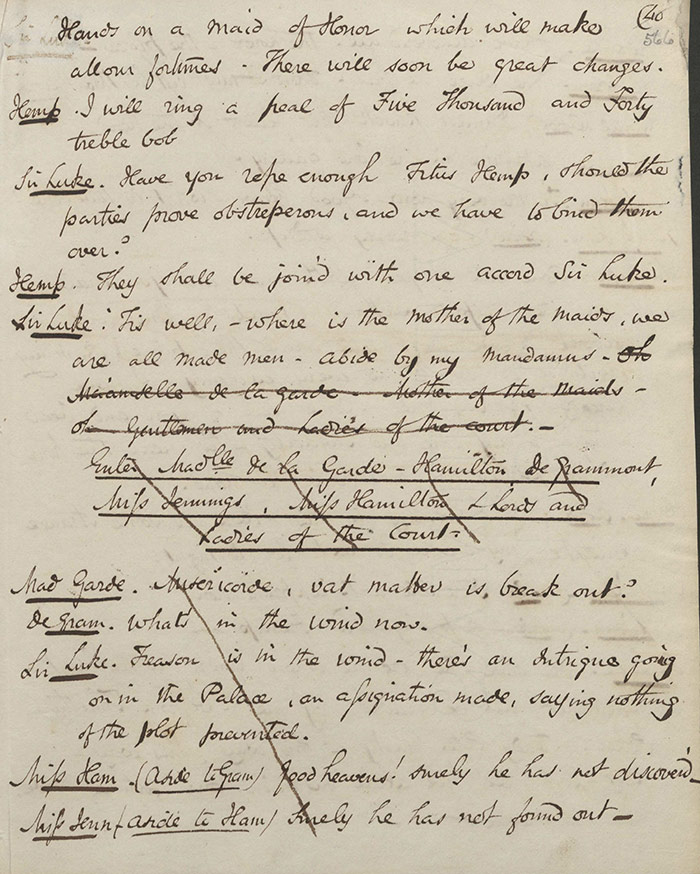

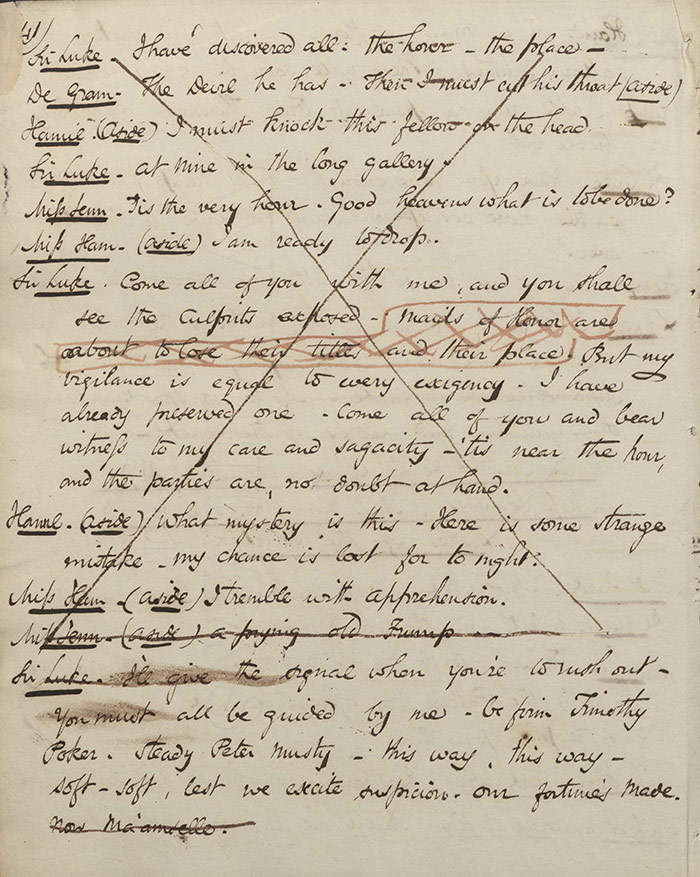

North and Killigrew are in disguise as the German Professor and his dwarf assistant (f.562r). Killigrew recognizes Sir Luke despite his disguise and tells him that the intrigue will take place at 9 o’clock in the long gallery. In the sixth scene Walter Stewart has some fun at Sir Luke’s expense by pretending that he is a ribald old man ready to supply the king with maids of honour and arranges a meeting with him (f.564r). Mme de la Garde, De Grammont, Hamilton, Miss Hamilton, Miss Jennings, and others enter and Sir Luke announces he has discovered an intrigue set to take place at 9 that night. Various parties are horrified that their plots are discovered and they are led by him to go and catch the culprits.

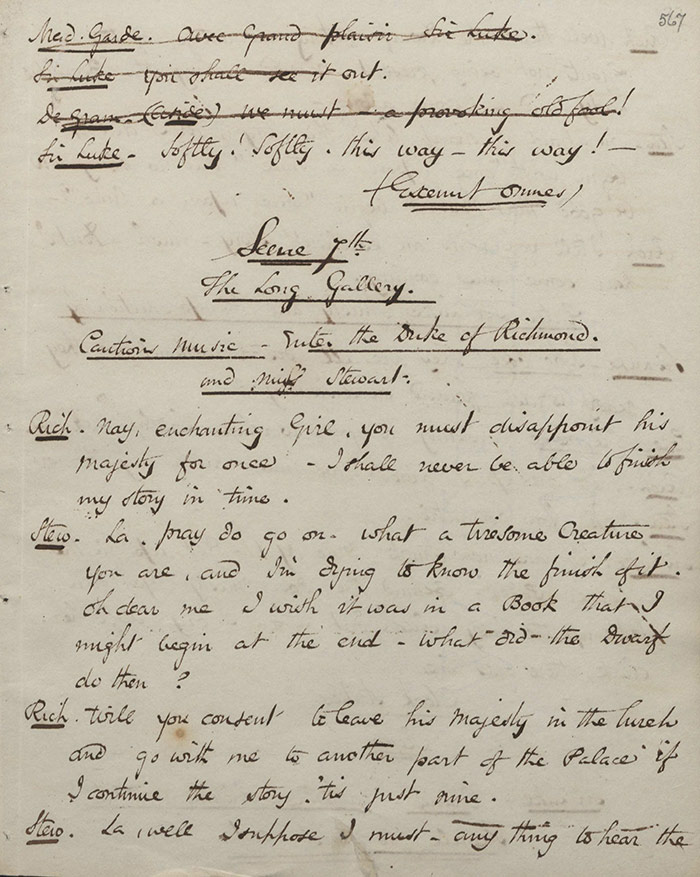

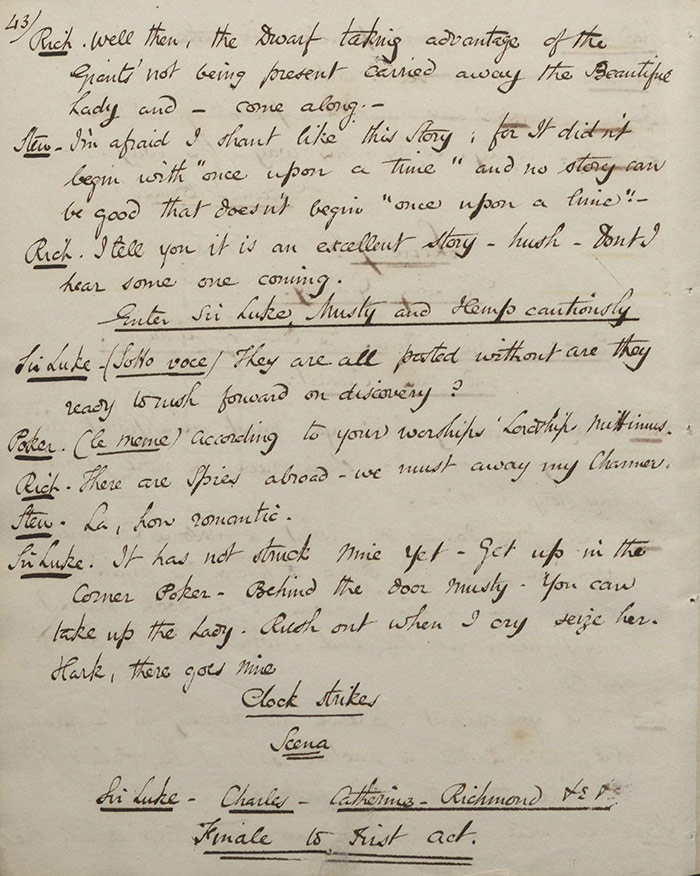

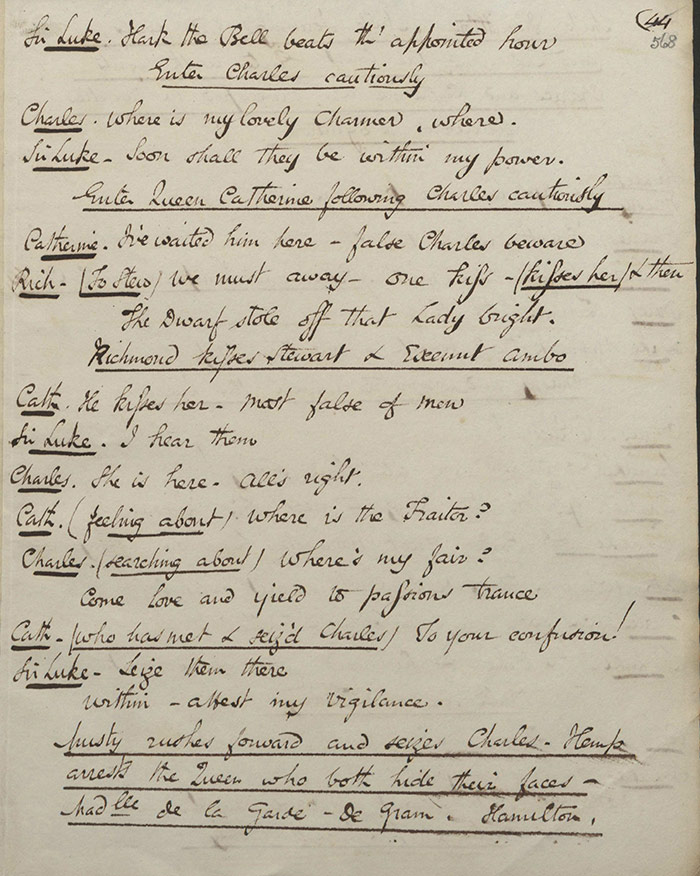

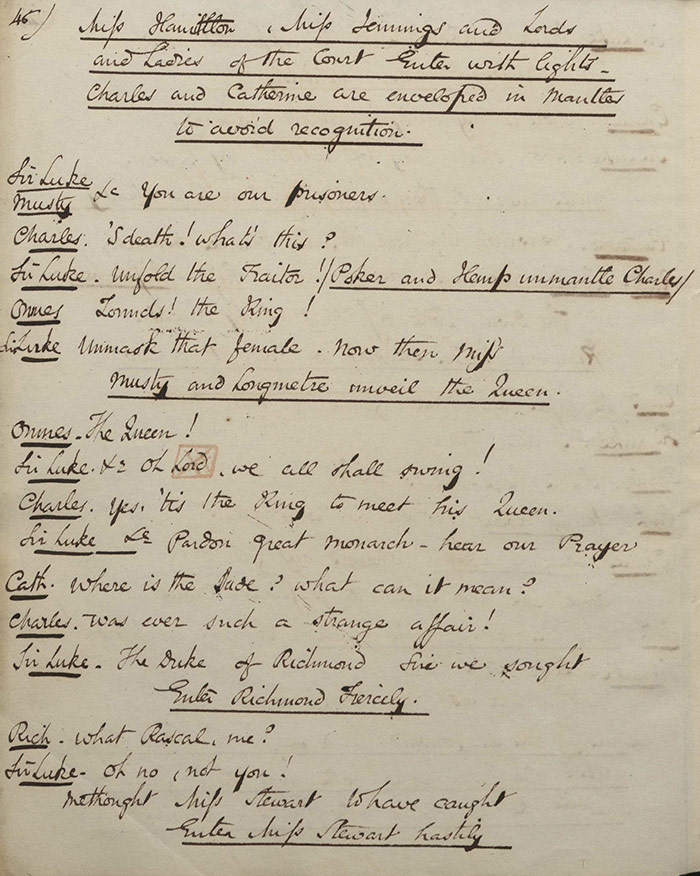

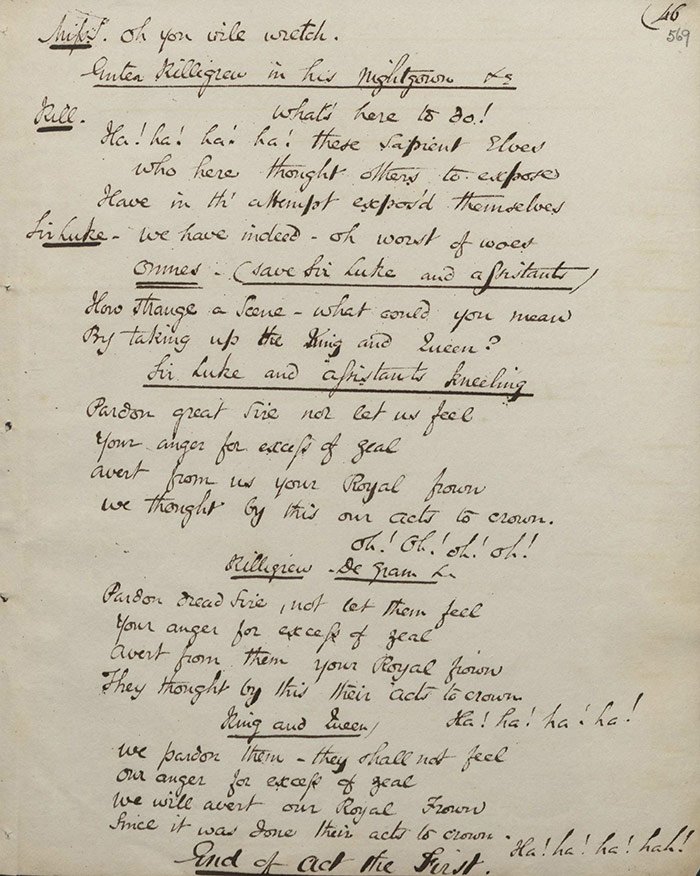

The seventh and final scene of the act takes place in the long gallery where Richmond is courting Miss Stewart, trying to get her to leave the long gallery and abandon her meeting with the king by telling her stories (f.567r). The clock strikes 9 and Sir Luke and others enter. In a madcap conclusion to the act, Richmond and Miss Stewart steal out and Charles and Catherine (who has followed her husband to catch him out) are both grabbed and arrested by Sir Luke’s men. They are then revealed to Sir Luke’s astonishment and fright but the king, amused, forgives all.

Act II

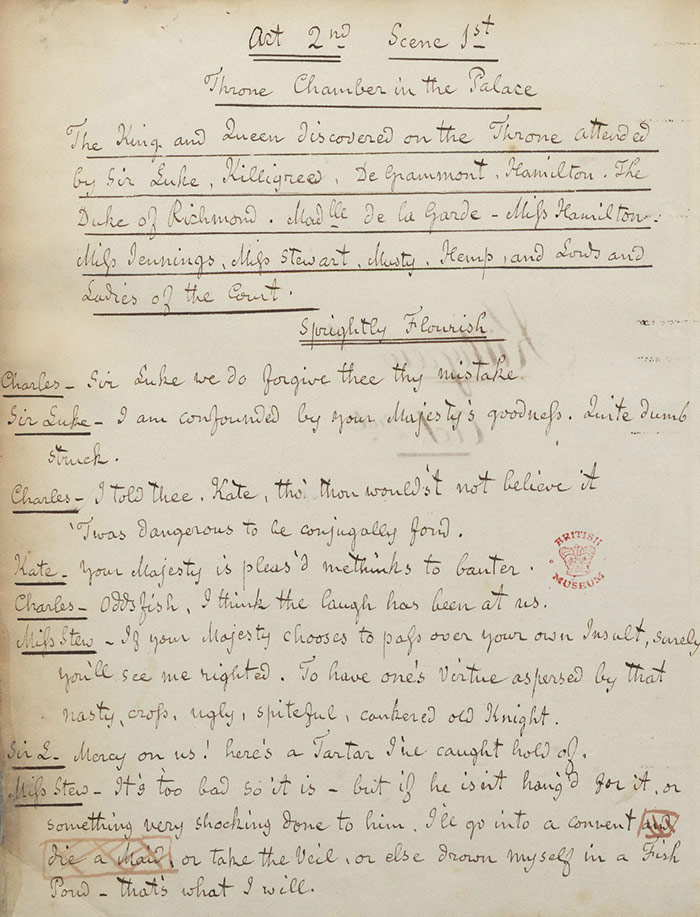

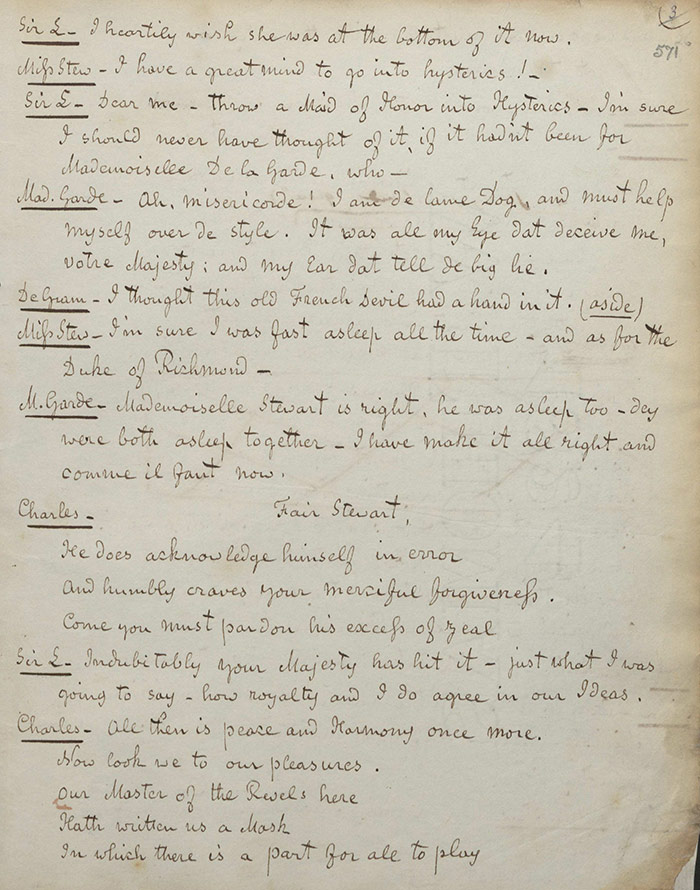

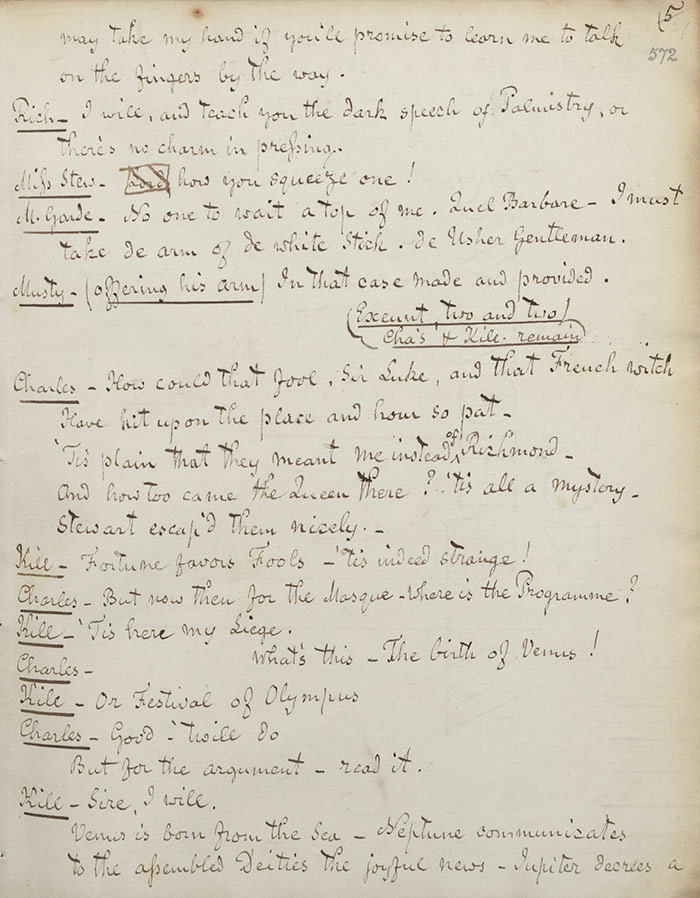

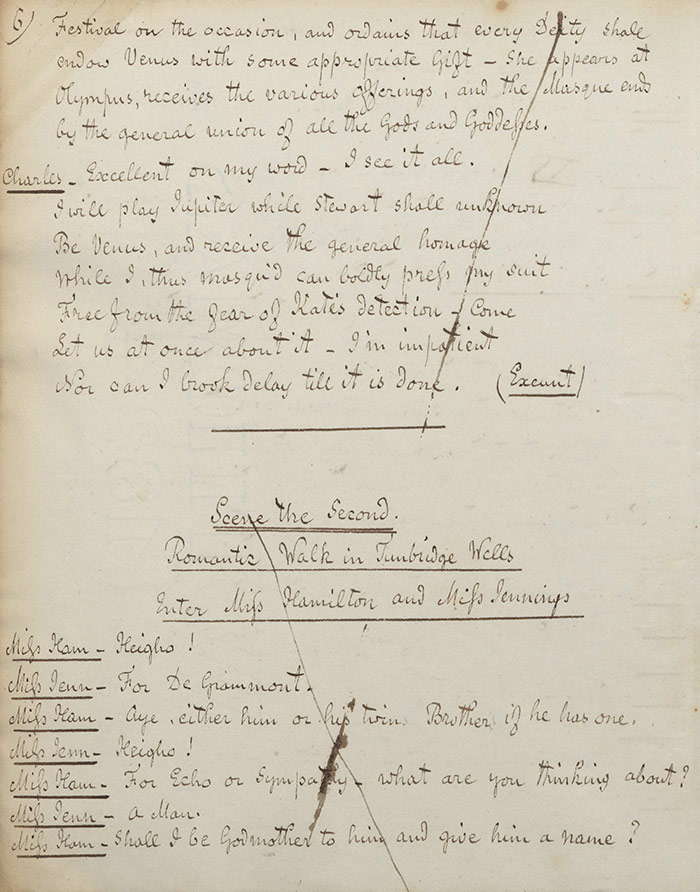

All the major characters are in the throne room where Miss Stewart is attempting to get Sir Luke punished for his error but the king laughs the incident off (f.570v). He is more interested in getting to the entertainment that Killigrew has devised. Killigrew tells him of his masque The Birth of Venus; or, Festival of Olympus and the King is delighted, planning to play Jupiter to Miss Stewart’s Venus so that he can woo her.

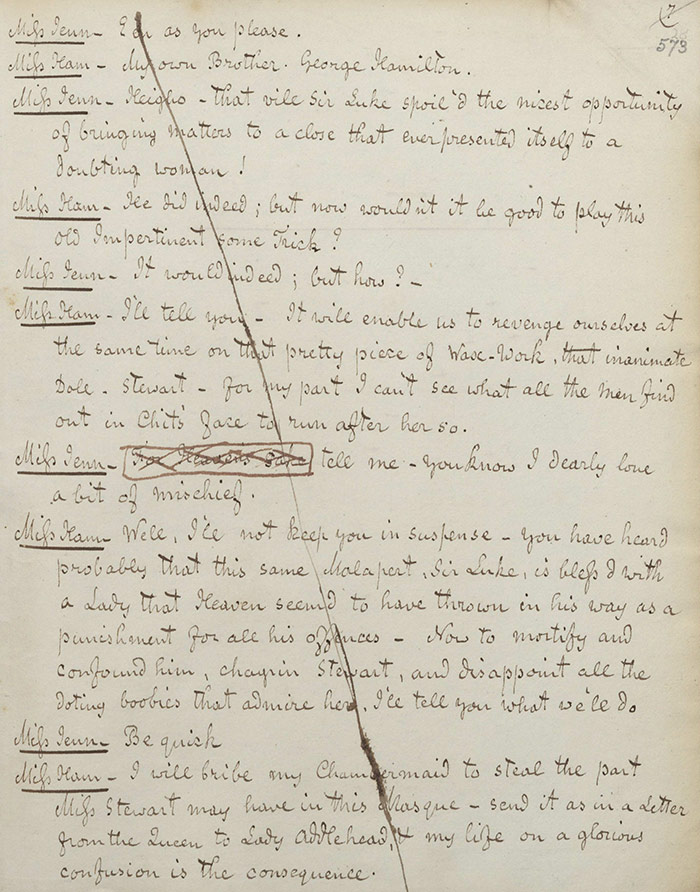

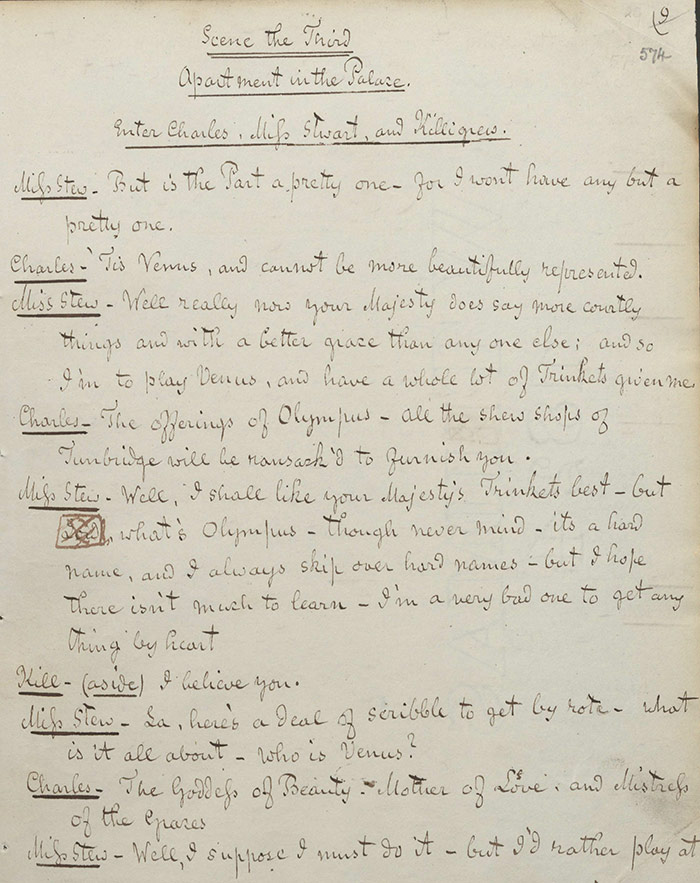

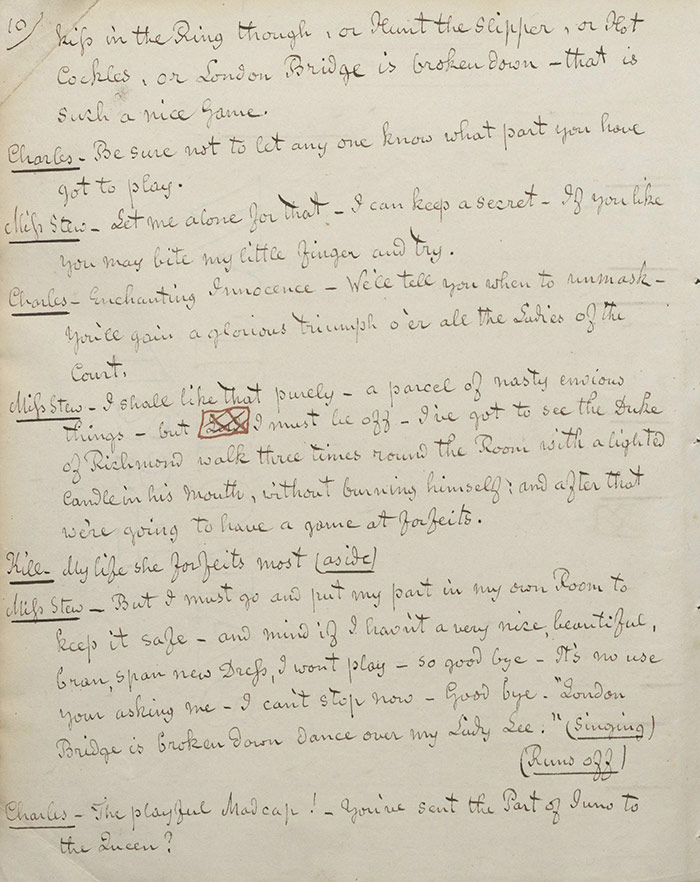

The second scene finds Miss Hamilton and Miss Jennings out for a walk and plotting revenge against Sir Luke and Miss Stewart of whom they are jealous (f.572v). Miss Hamilton will bribe her chambermaid to steal the part intended for Miss Stewart and send it to Lady Addlehead. The King, Miss Stewart and Killigrew are in the palace with the King telling Miss Stewart of her part (f.574r). She shows herself to be somewhat vain and idiotic and Killigrew’s asides note her intellectual shortcomings. Sir Luke is to play Neptune, the Queen Juno, and Killigrew is to take the part of Momus.

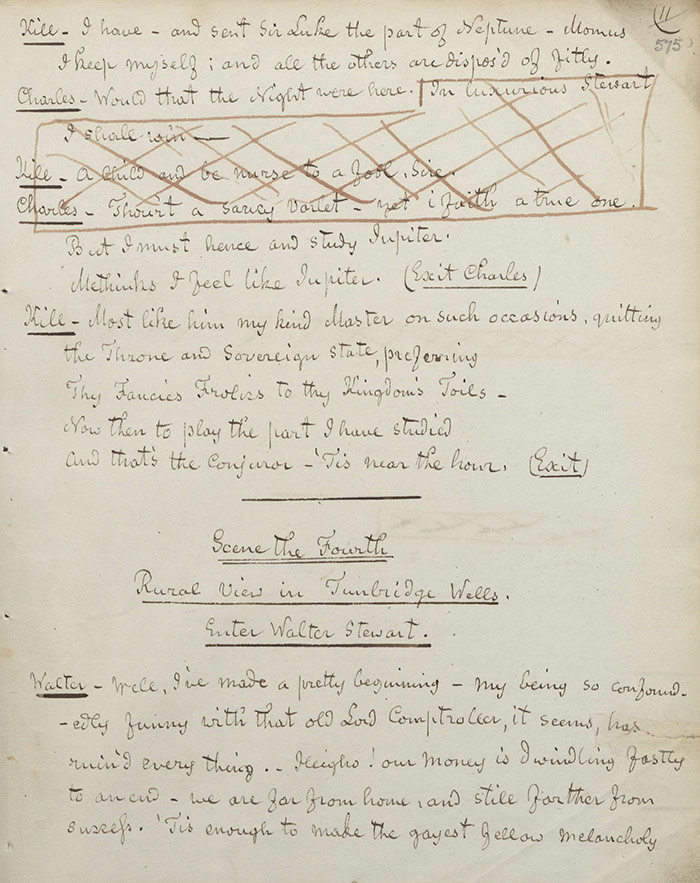

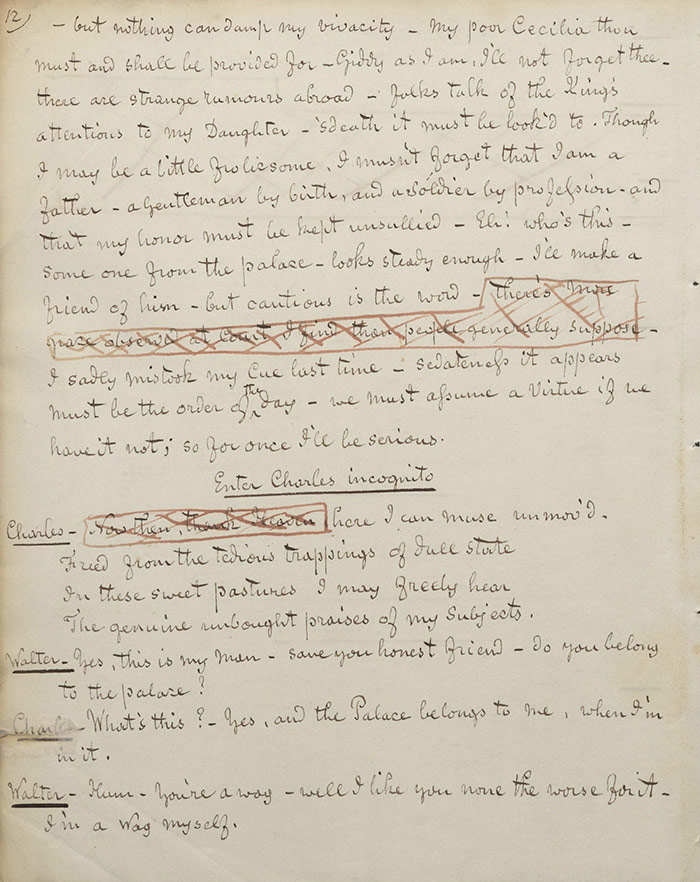

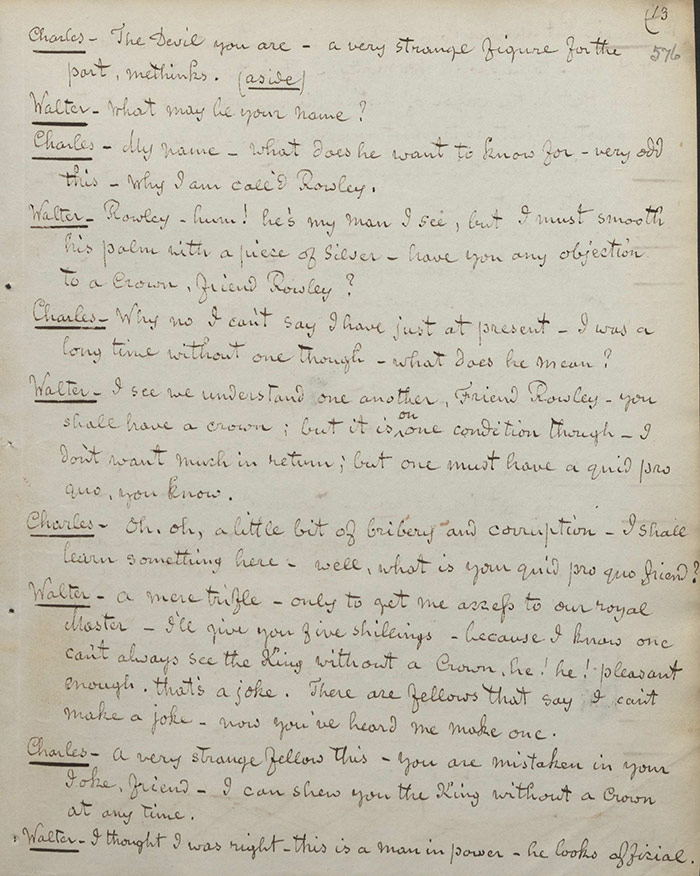

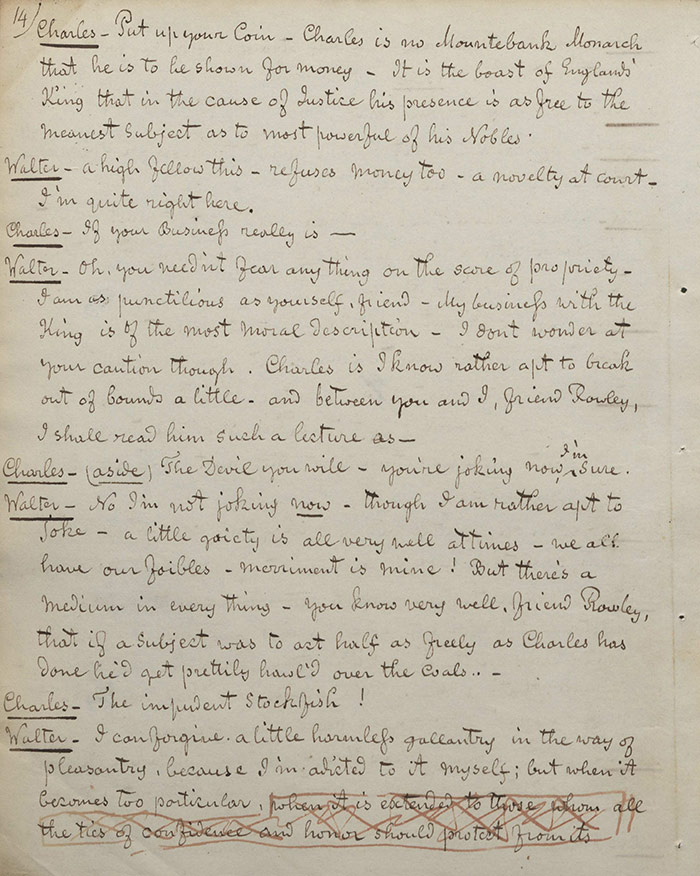

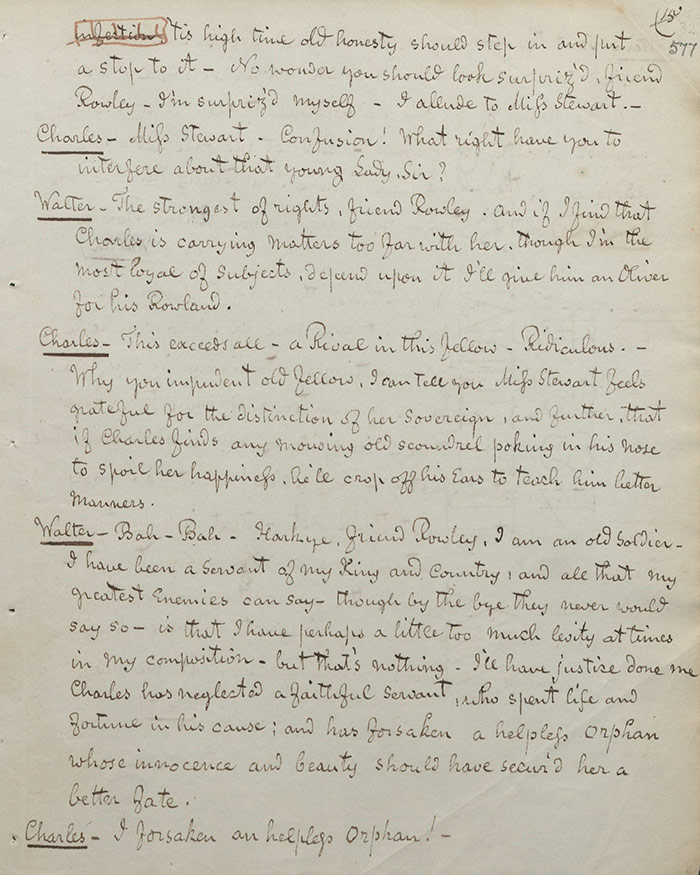

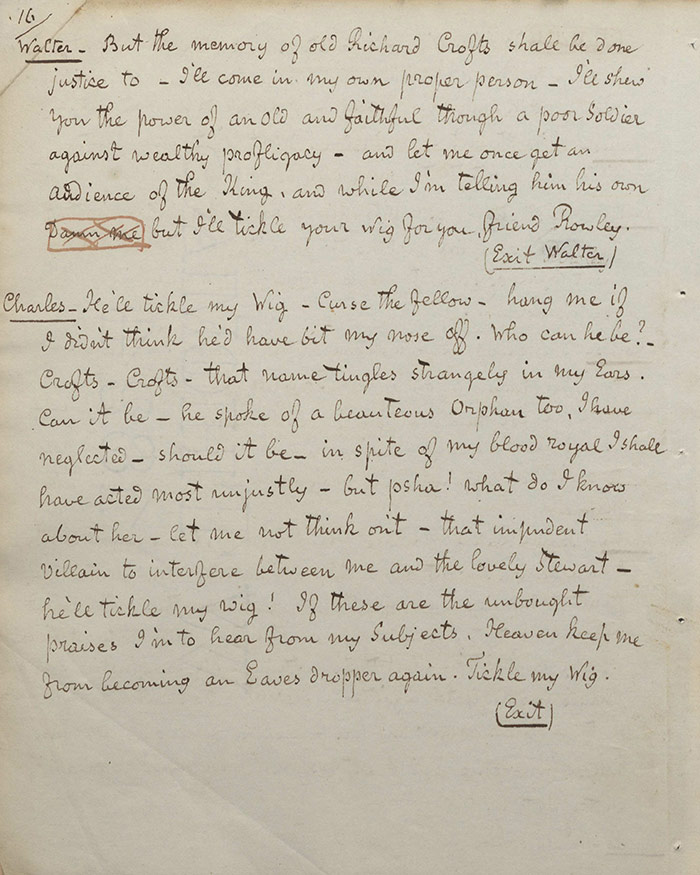

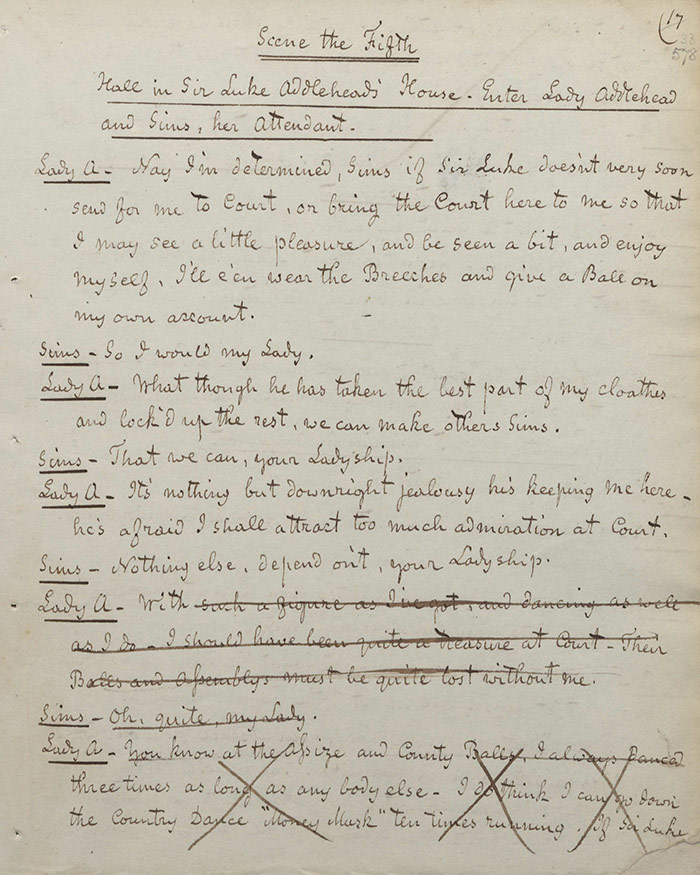

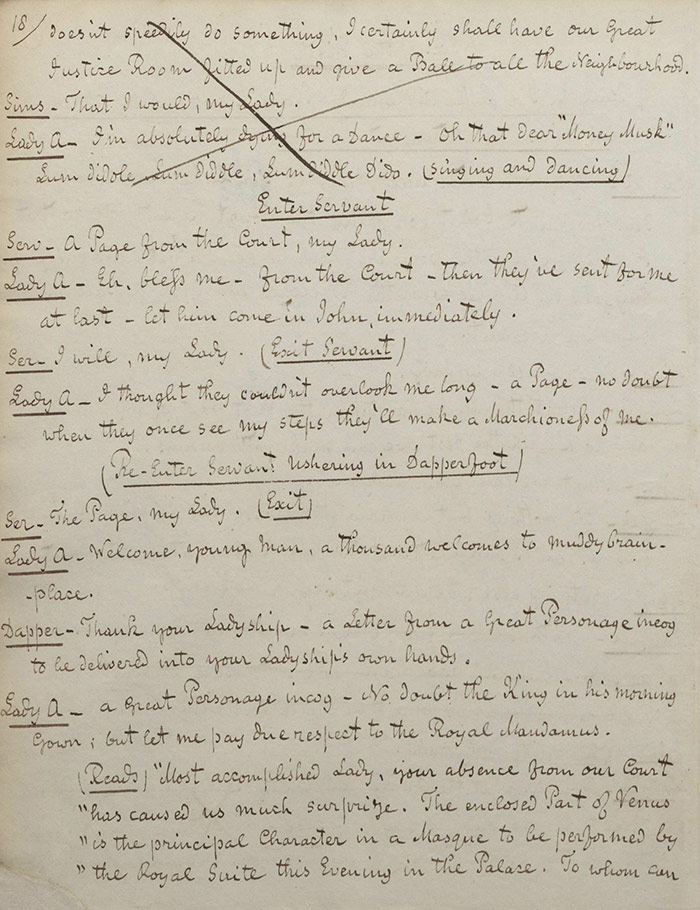

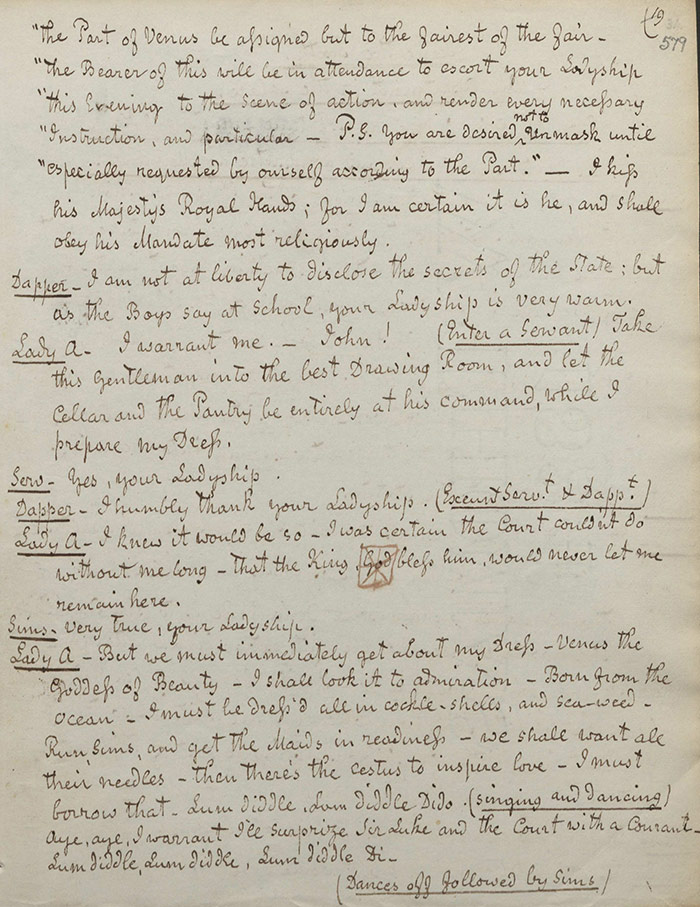

Walter Stewart is musing on his situation (f.575r). He has heard of the King’s interest in his daughter and is determined to protect her and his honour. The King enters, incognito, and becomes irritated by Stewart’s claim over Miss Stewart and the mention of unjust treatment of an orphan. Stewart insists that when the King hears the name Richard Crofts, this will get him a sympathetic hearing and exits. The name is strangely familiar to the King and he begins to wonder if he has in fact behaved unjustly to the orphan of Stewart’s tale. Lady Addlehead complains to her servant, Sirus, about Sir Luke keeping her hidden away from court where she should be leading the way at balls and entertainments (f.578r). Dapperfoot arrives from court with the part of Venus for her and she is suitably elated.

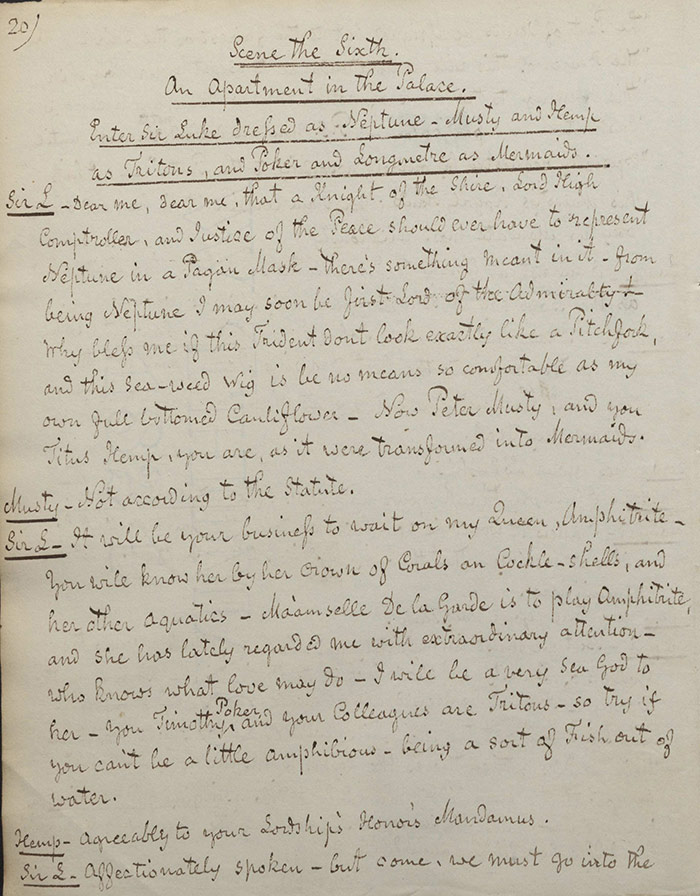

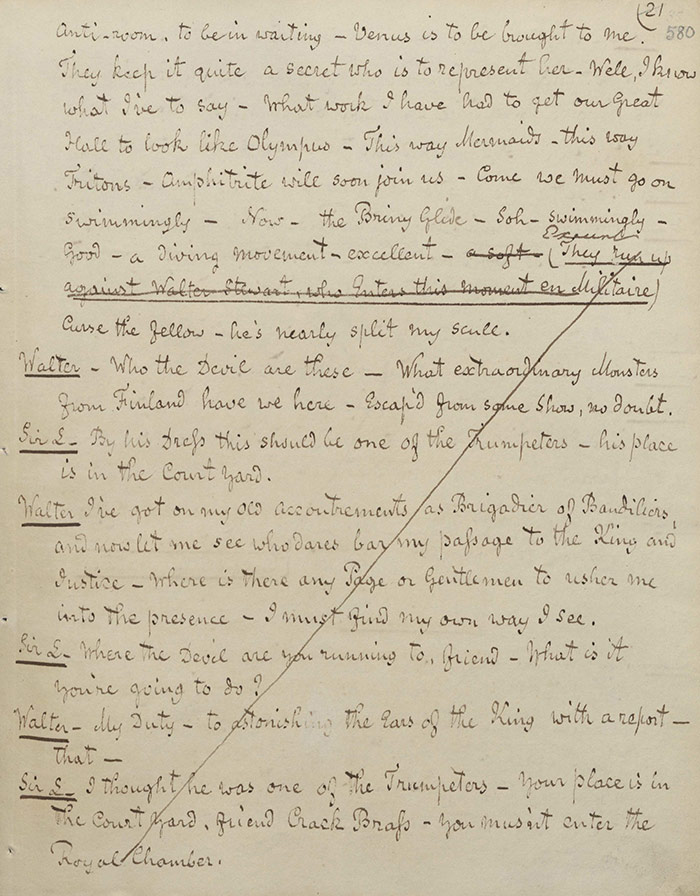

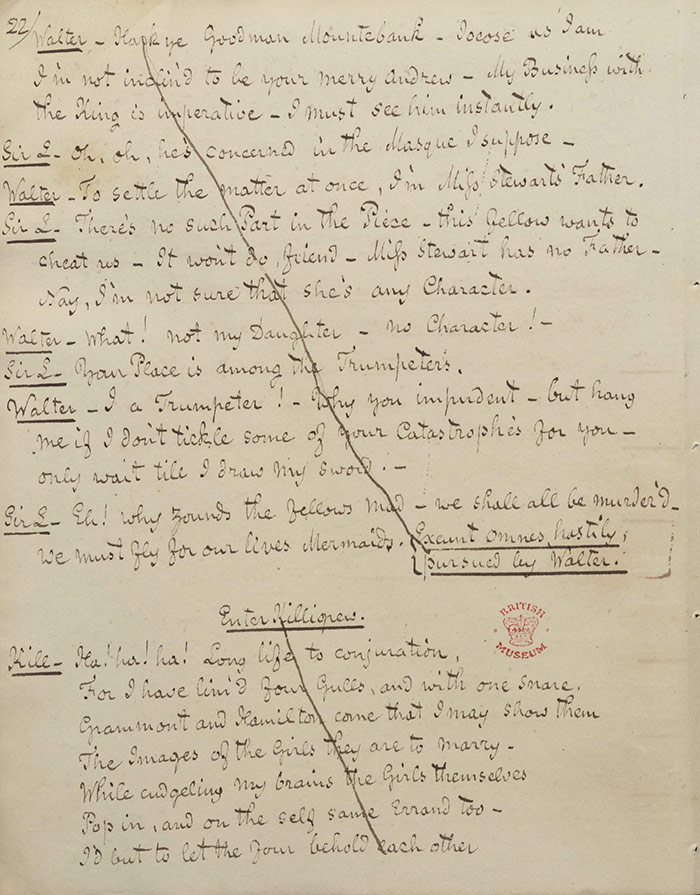

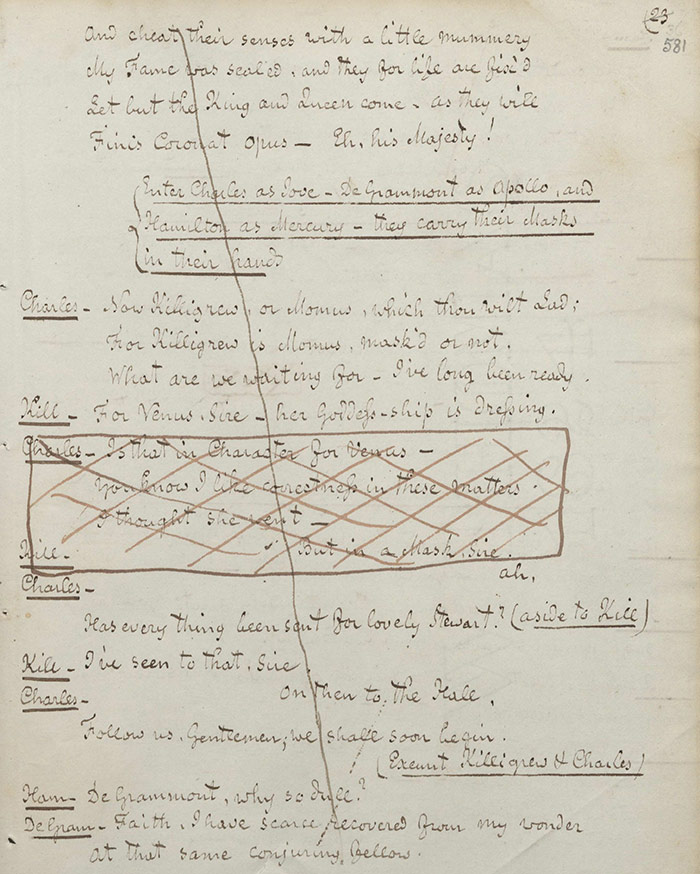

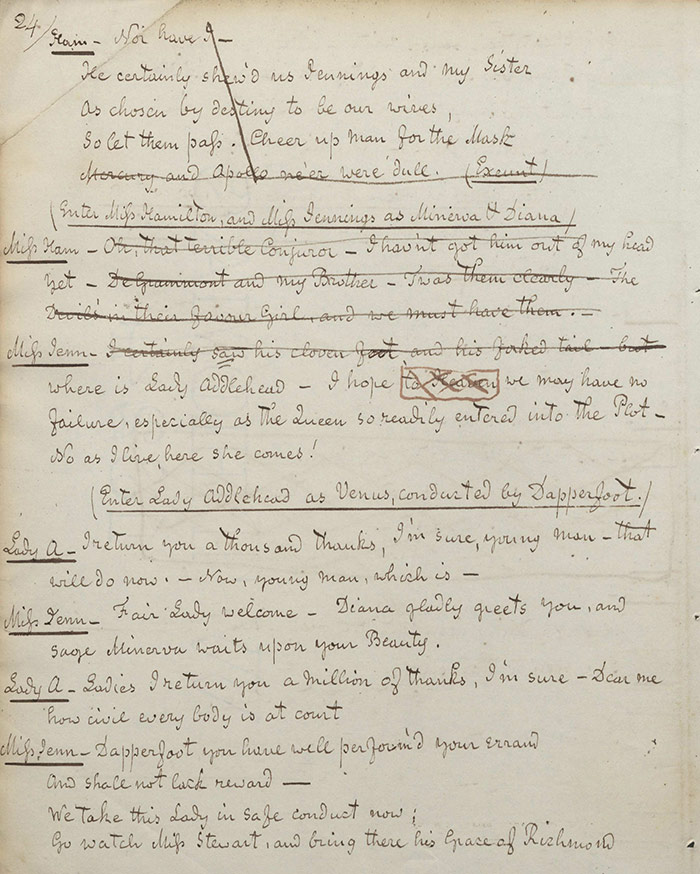

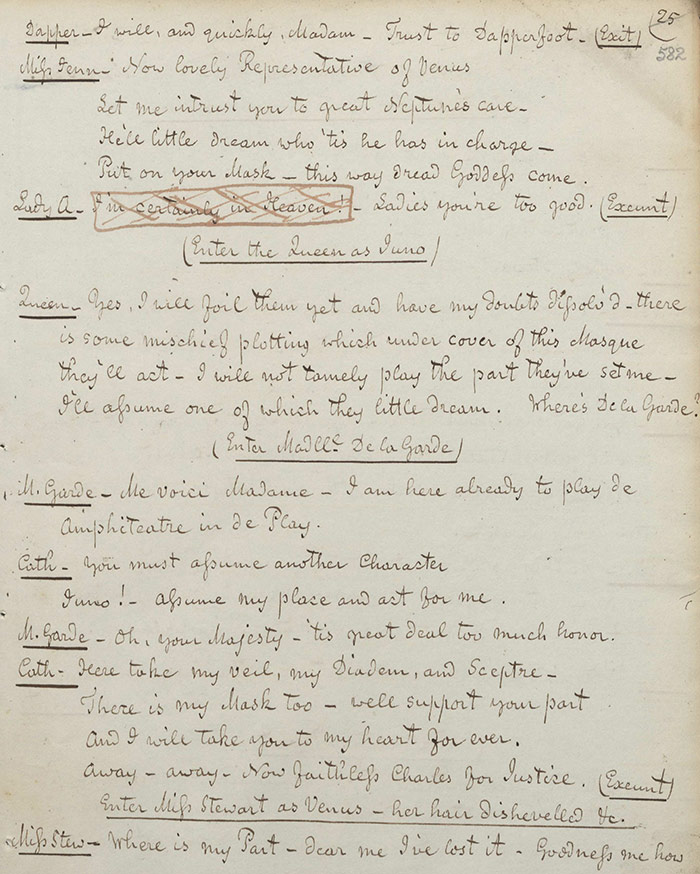

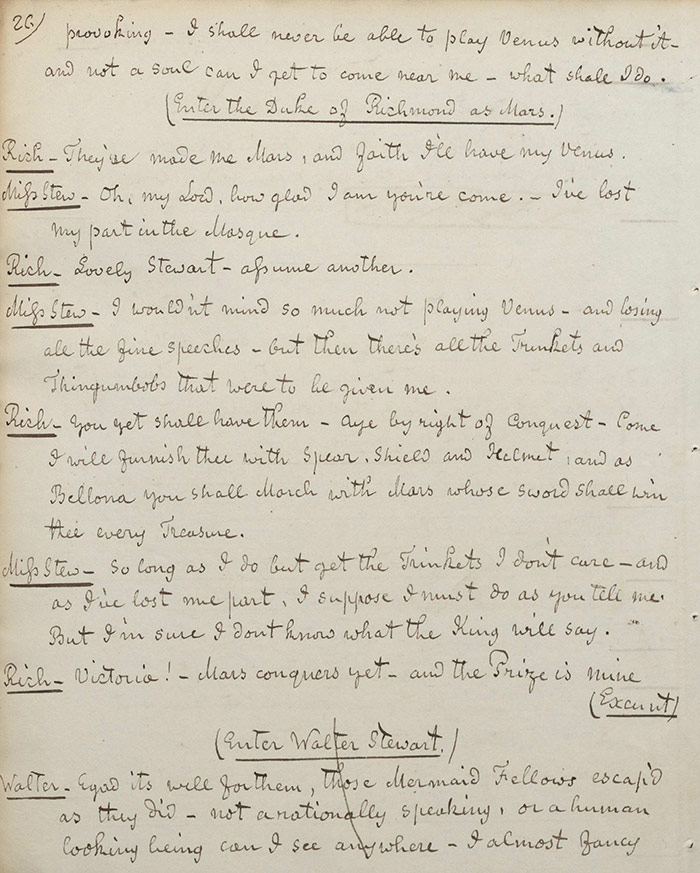

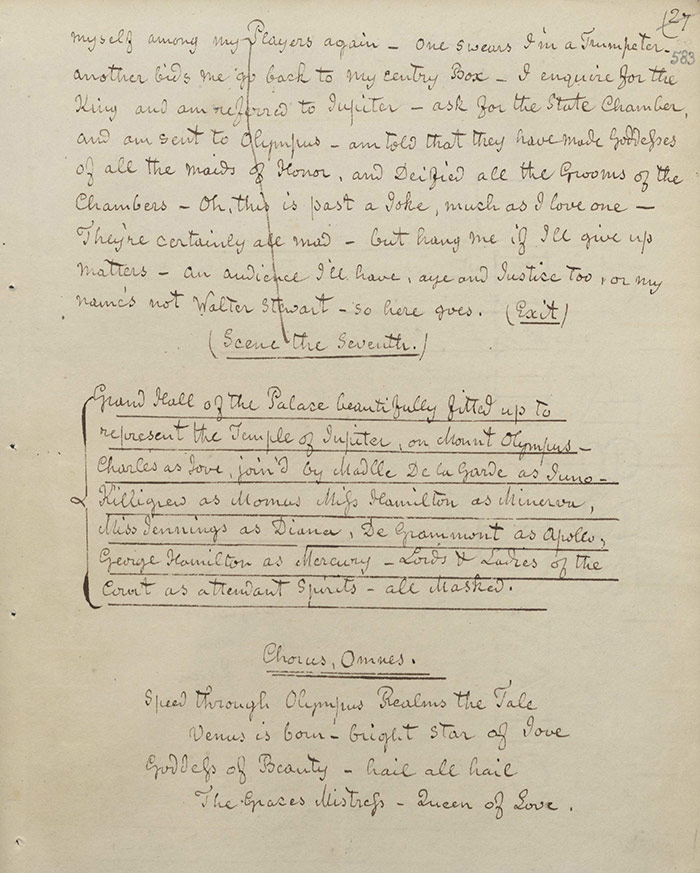

Sir Luke is dressed as Neptune with Musty and Hemp as Tritons, and Poker and Longmeter as Mermaids (f.579v). Walter enters in full military dress, determined to see the king. Sir Luke thinks initially he is a trumpeter for the masque which only enrages Walter who chases them off. Killigrew then enters and is delighted with his mastery of the revels and in the guise of the German Professor has had some fun with Grammont, Hamilton, Miss Jennings, and Miss Hamilton by showing them to each other as future husbands and wives, somewhat to their chagrin. Miss Jennings and Miss Hamilton play Diana and Minerva, and they escort a very pleased Lady Addlehead into the masque. The Queen enters and she is certain something is up and orders Mademoiselle de la Garde to take her place as Juno while she takes her role as Amphityre, Neptune’s consort. As they exit, Miss Stewart enters as Venus but she has lost her lines. Richmond enters as Mars and, by promising her the trinkets she is looking for, persuades her to play the part of his consort, Bellona, instead.

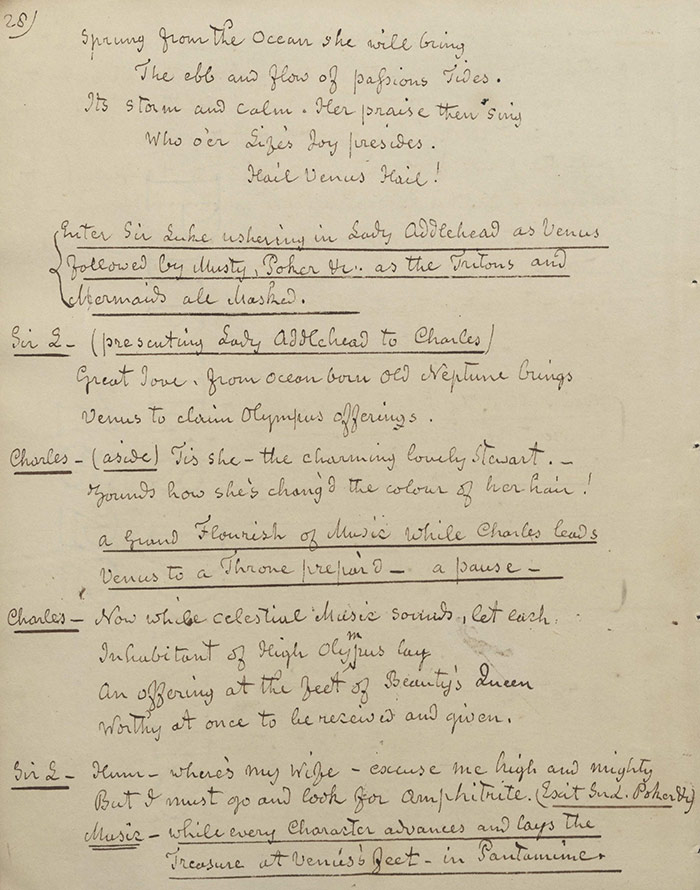

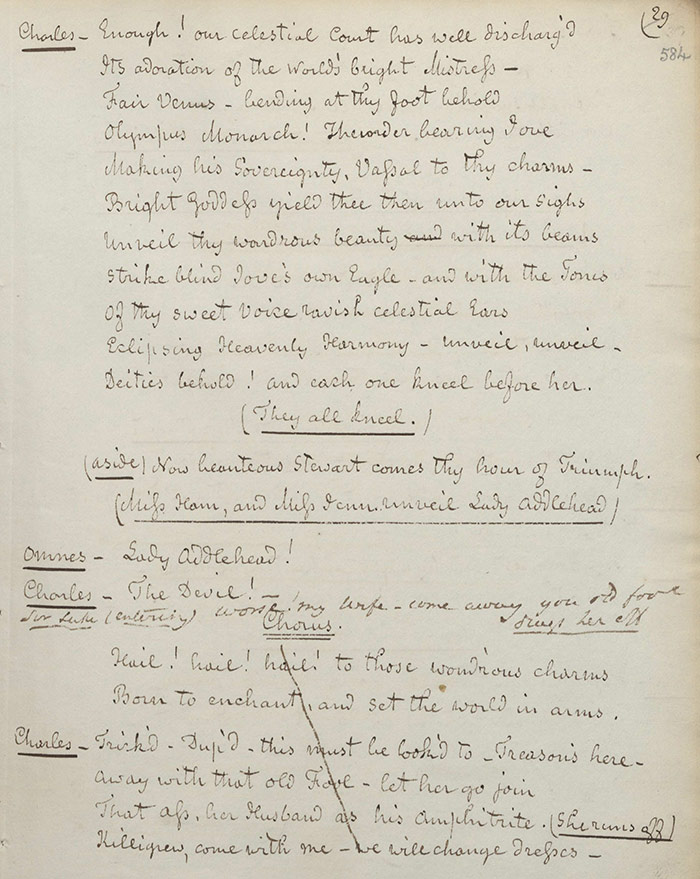

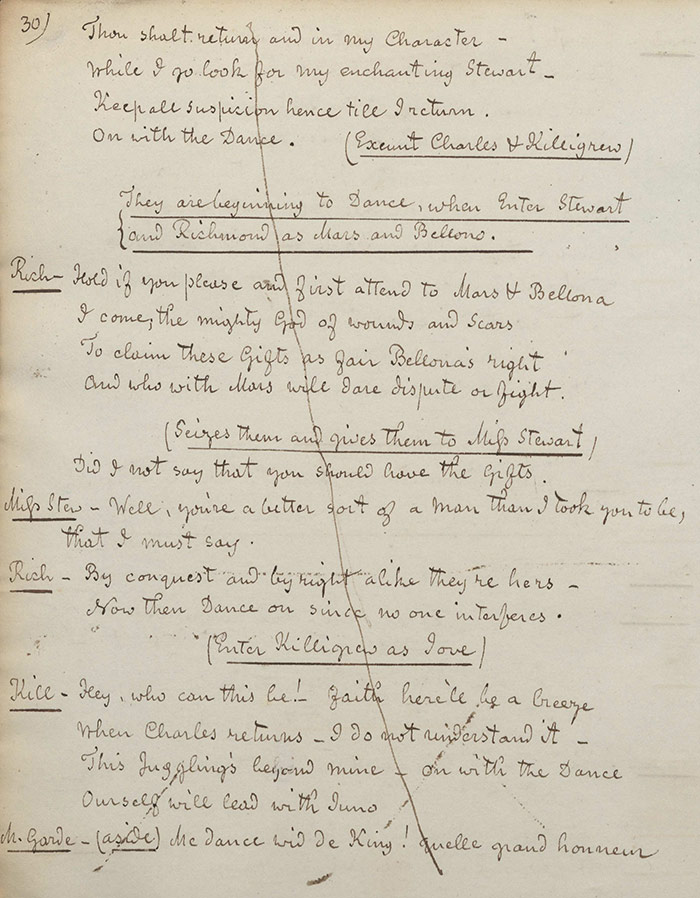

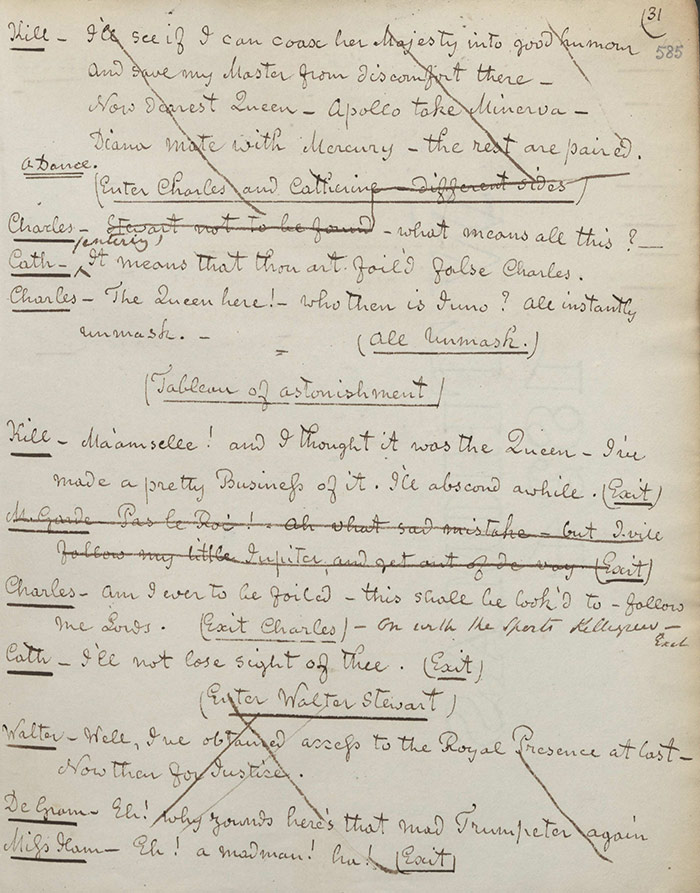

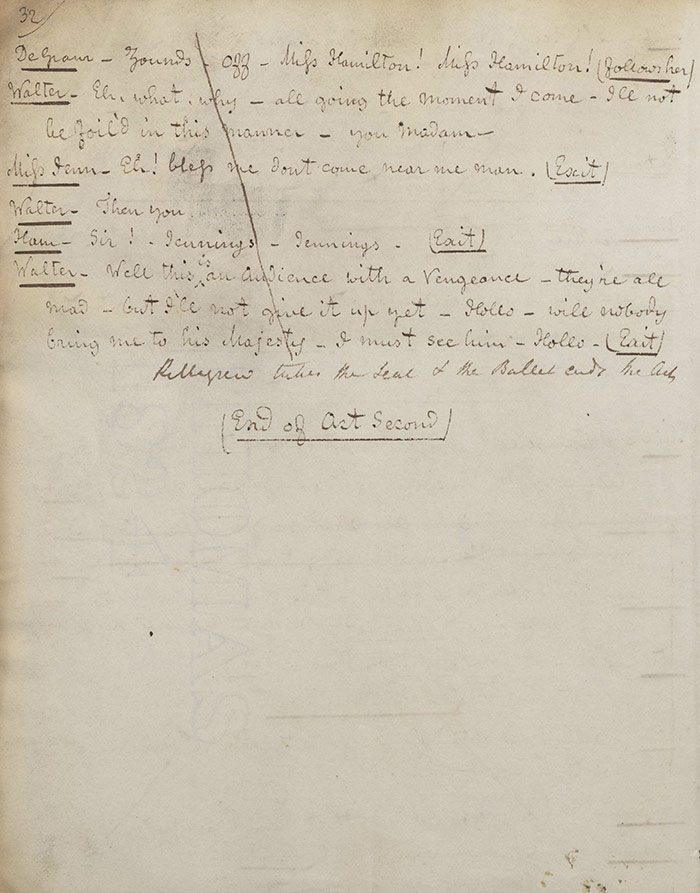

The cast is assembled in the Hall of the Palace which is set up to represent the Temple of Jupiter: King Charles (Jupiter); Mademoiselle de la Garde (Juno); Killigrew (Momus); Miss Hamilton (Minerva); Miss Jennings (Diana); De Grammont (Apollo); George Hamilton (Mercury), and others as attendant Spirits (f.583r). The action of the masque plays out with Neptune presenting Venus to Jupiter but the King’s delicious anticipation is turned to horror when Lady Addlehead is revealed. Angered, he leaves to search for her but getting Killigrew to play Jove so his absence will not be noticed. Various personages enter, exit, and are unmasked and the act ends in some confusion.

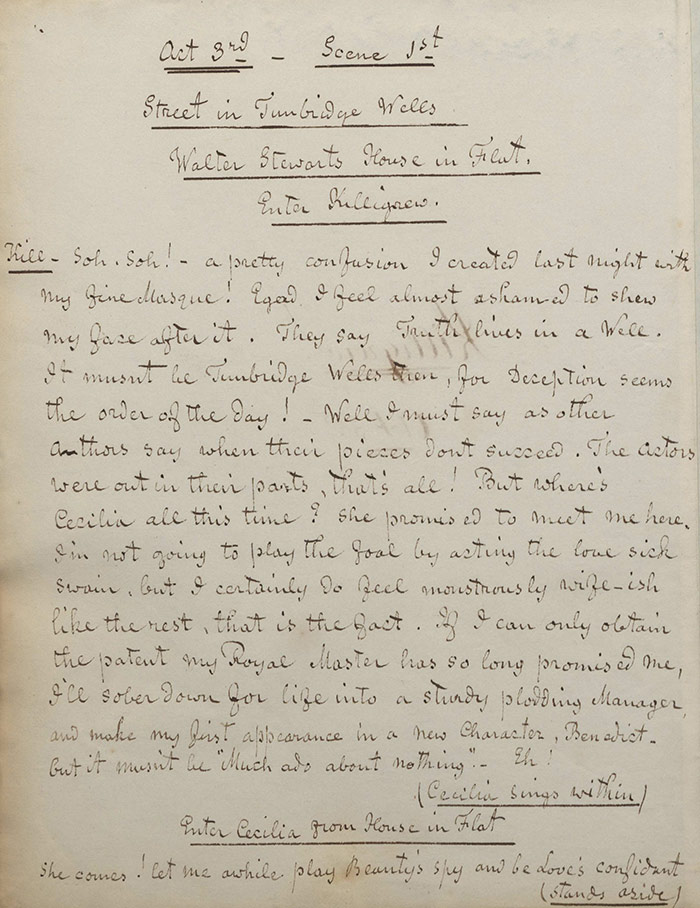

Act III

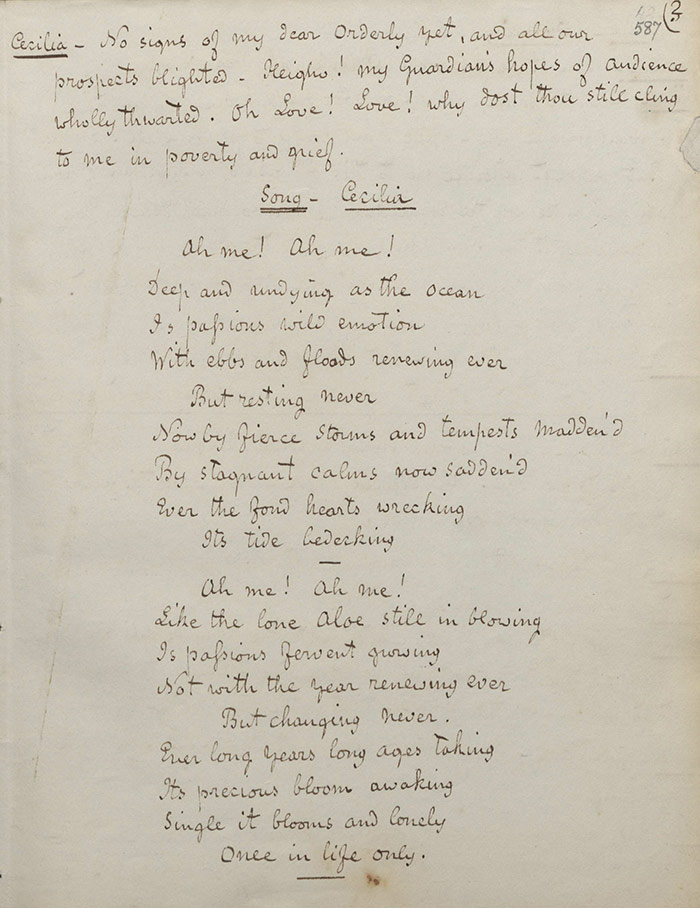

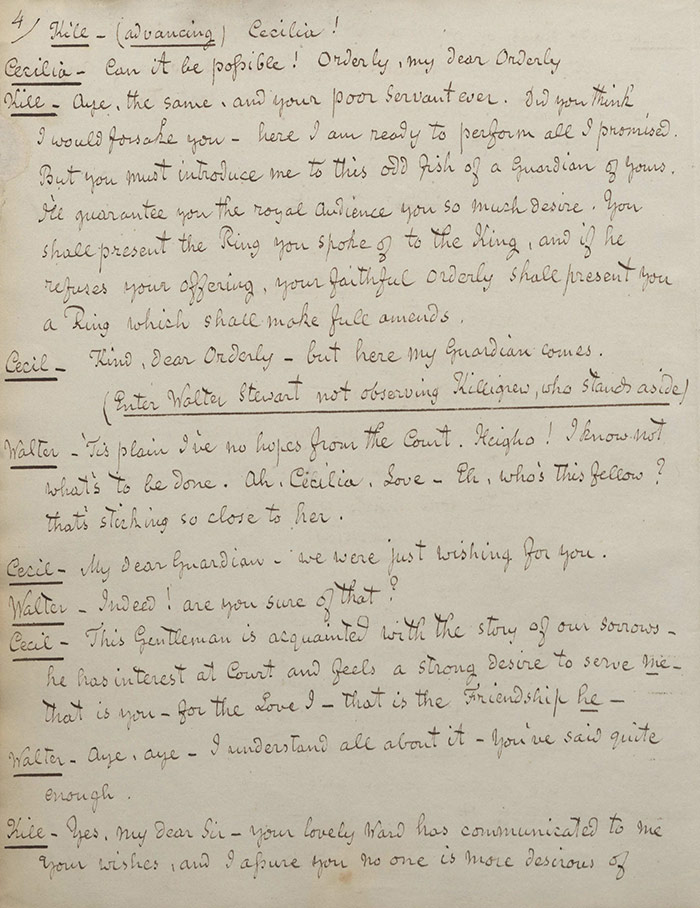

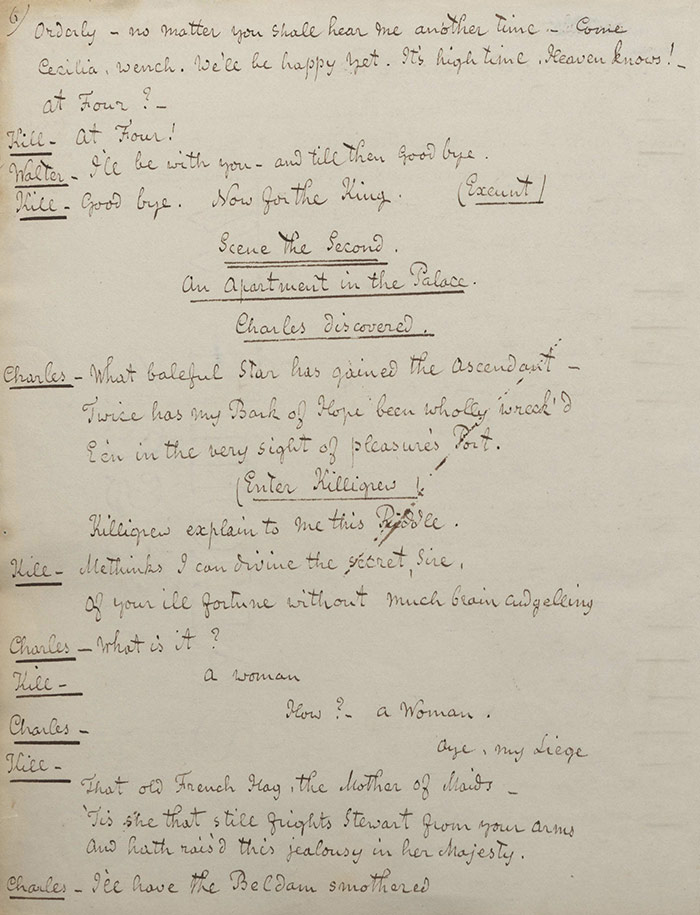

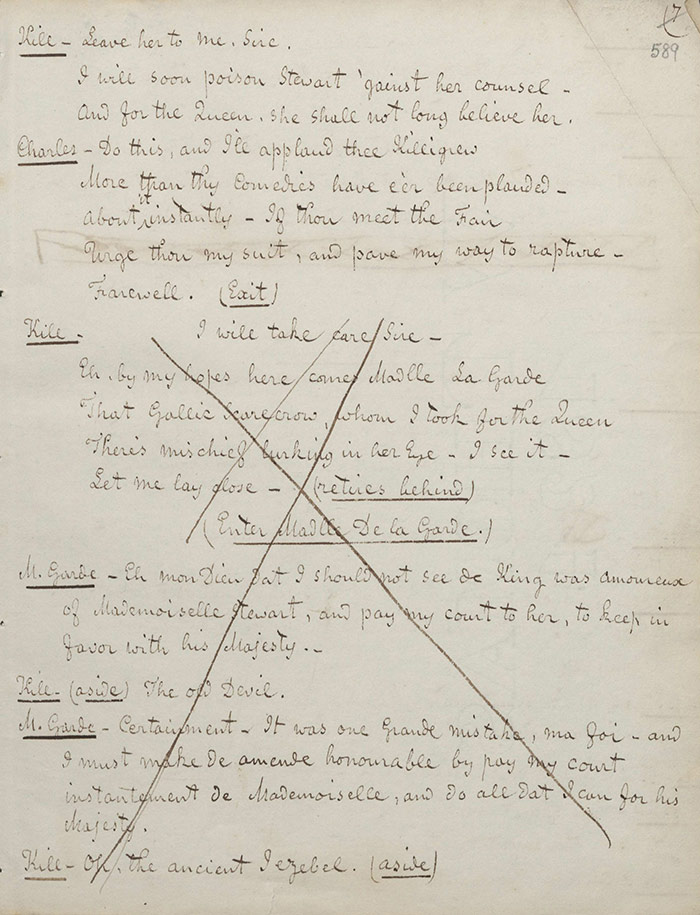

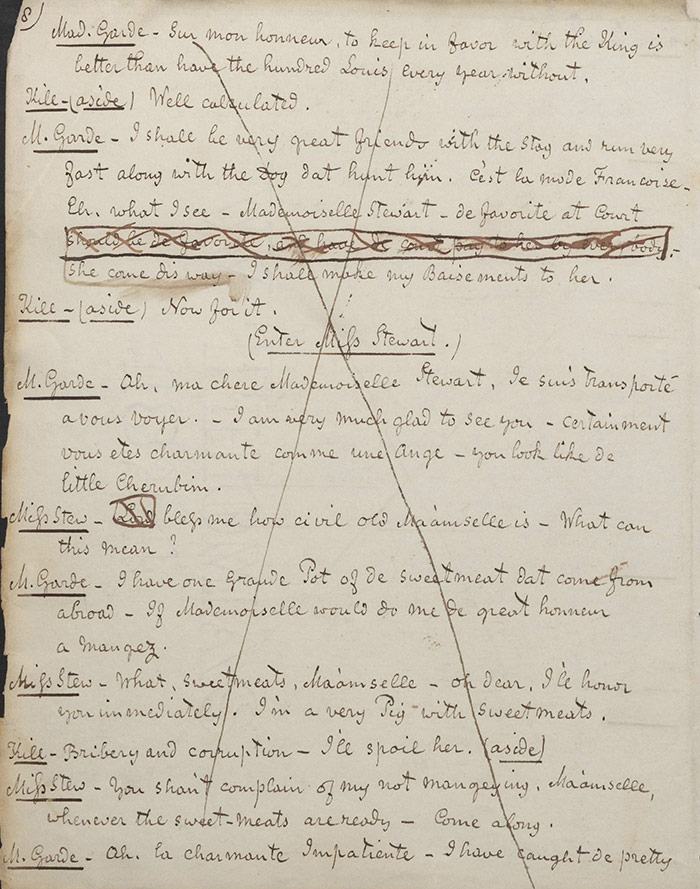

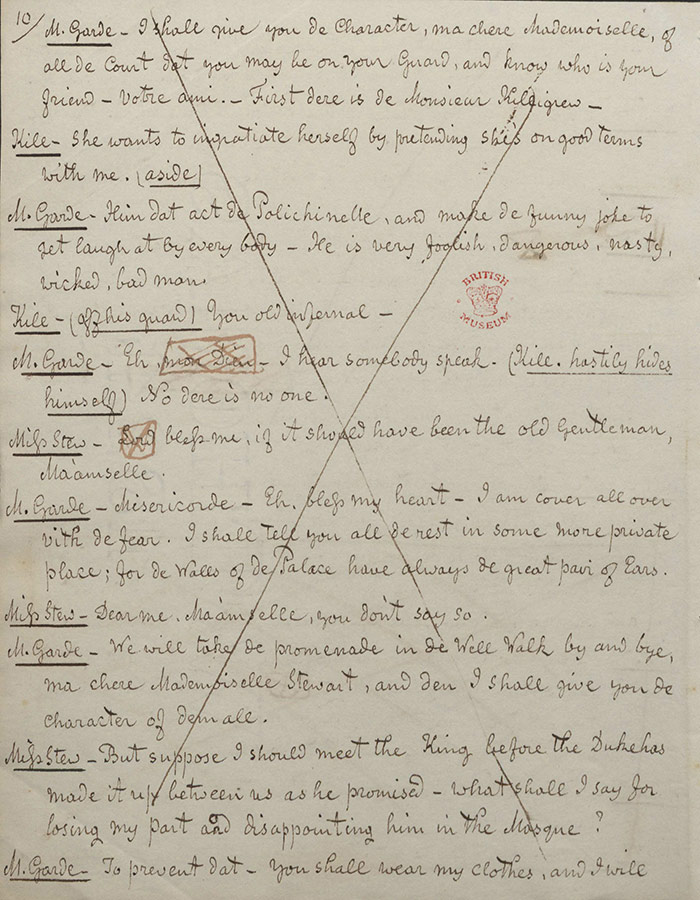

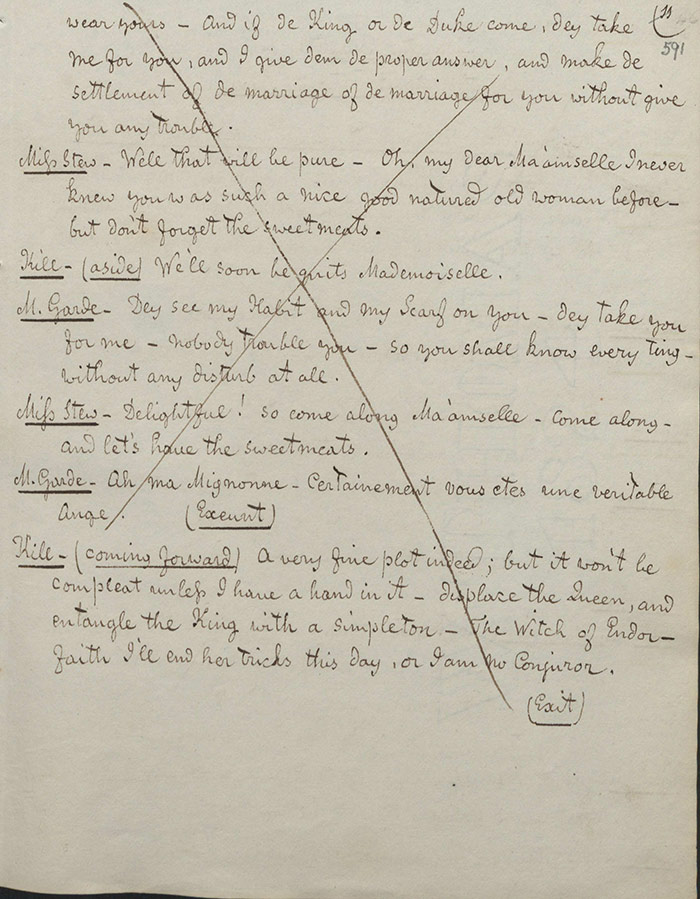

The opening scene finds Killigrew on a street in Tunbridge Wells hoping to meet his love, Cecilia, as well as extracting the royal patent long promised him by the King (f.586v). She arrives and introduces him – she knows him as Orderly – to Walter Stewart, her guardian. Killigrew tells him to be at the palace at four and he will get him an audience with the King. Killigrew convinces the King that it is Mademoiselle de la Garde that keeps Miss Stewart away from him and he promises to sort it out (f.588v). Killigrew then overhears Mademoiselle de la Garde trying to convince Miss Stewart to respond to the King’s suit and she also – to his anger – warns her against him. The two women agree to change clothes so that if they meet the King before the Duke of Richmond has a chance to make it up with Miss Stewart, Mlle de la Garde can deal with him. However, Killigrew overhears their plan.

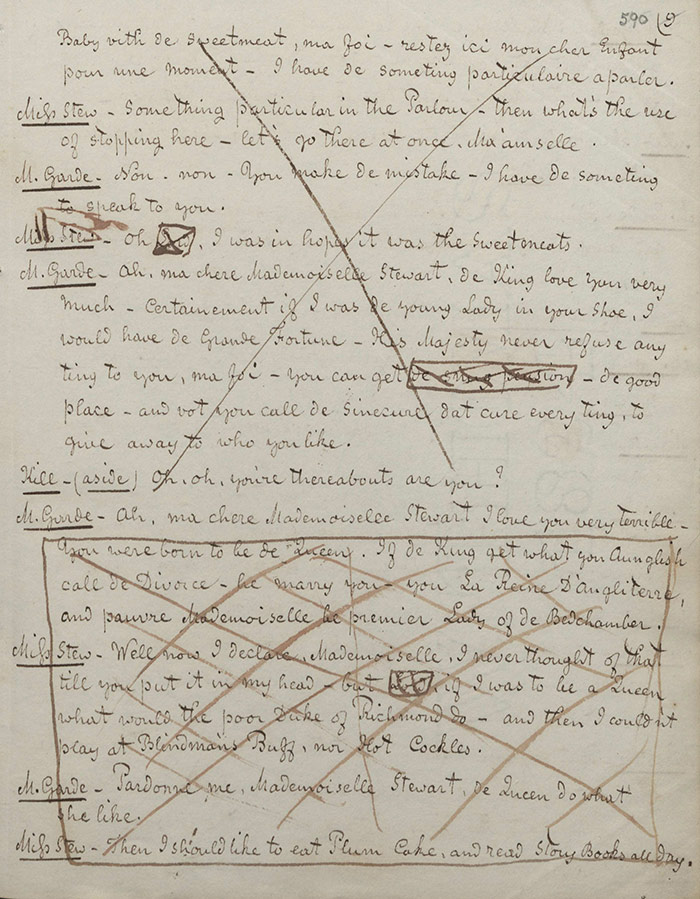

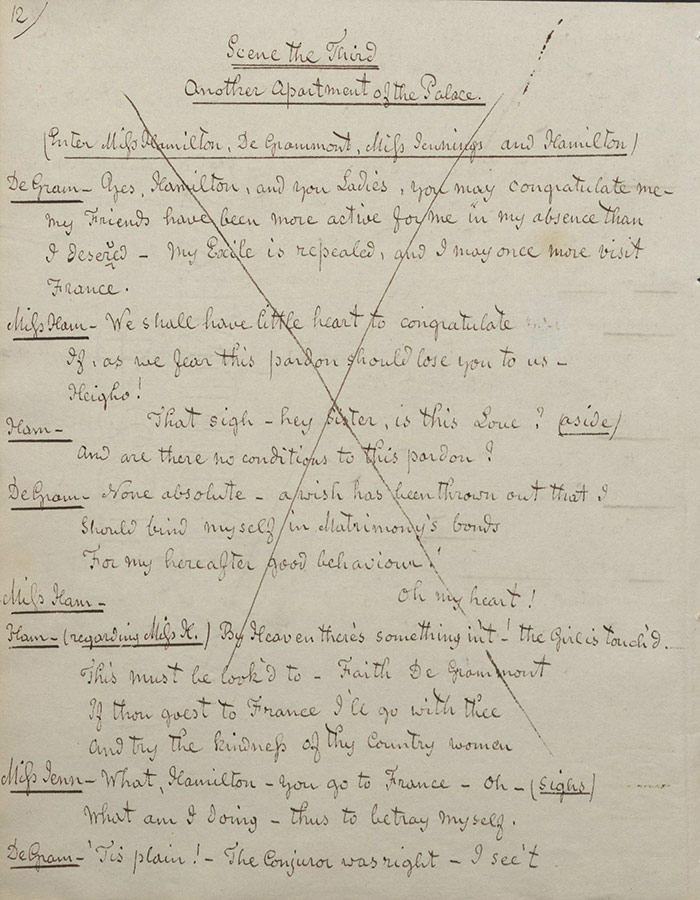

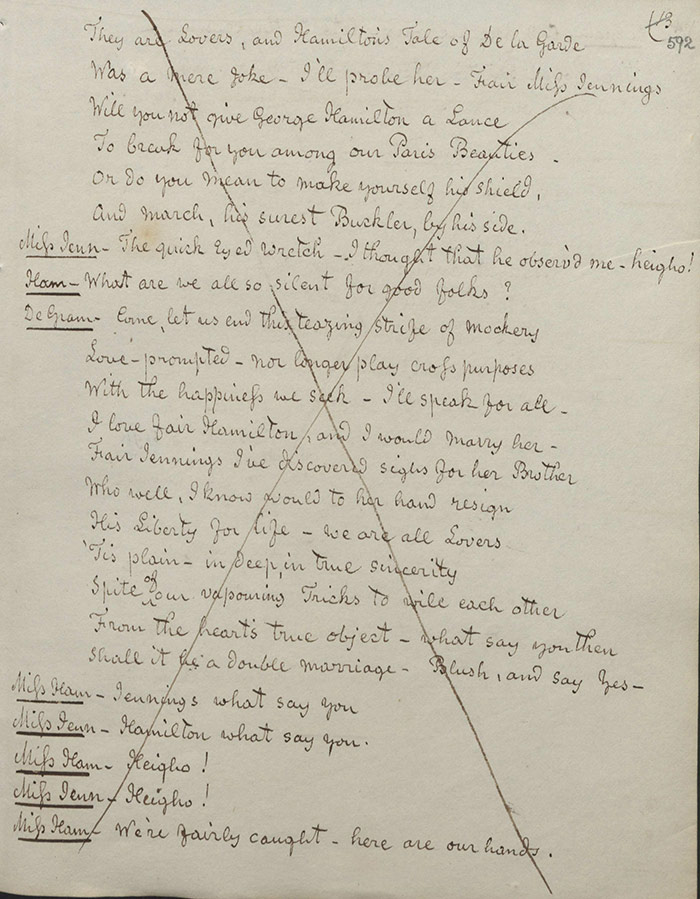

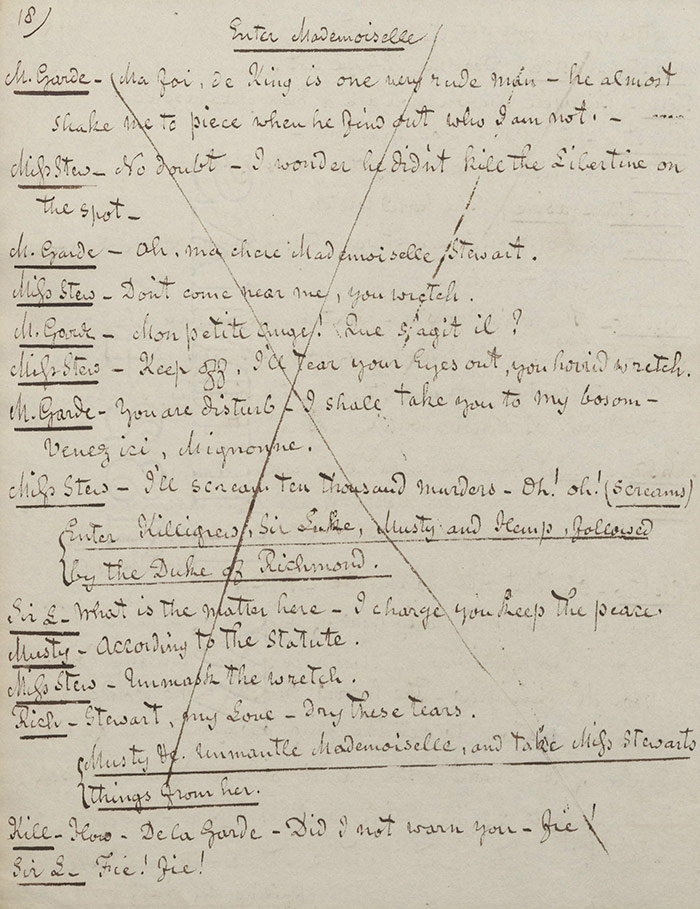

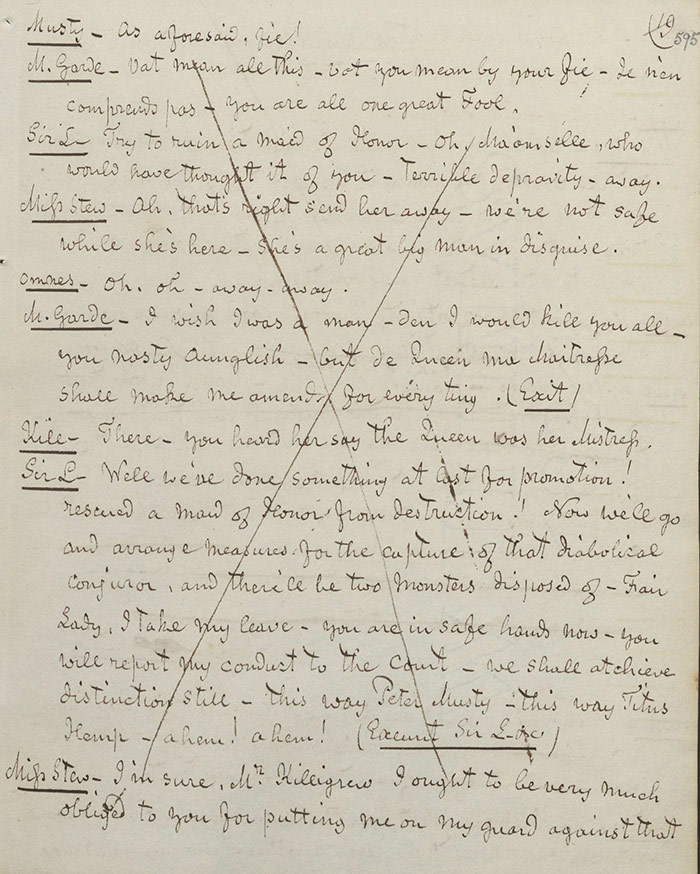

De Grammont tells Hamilton, Miss Hamilton, and Miss Jennings that he can now return to France (f.591v). This brings about a mutual admission that the pairs love each other. Mlle de la Garde and Miss Stewart are discovered by the King (f.593v). When Mlle de la Garde leads him off as planned, Killigrew takes the opportunity to convince the dimwitted Miss Stewart that Mlle de la Garde is actually a man in disguise determined to debauch the maids of honour. She believes him and when Miss Stewart, Killigrew, and Sir Luke gang up on her, she runs to the Queen for solace. The Duke of Richmond continues to woo Miss Stewart and she begins to relent, inviting him to come to her unlocked room in two hours time. Killigrew overhears and sees comic possibilities.

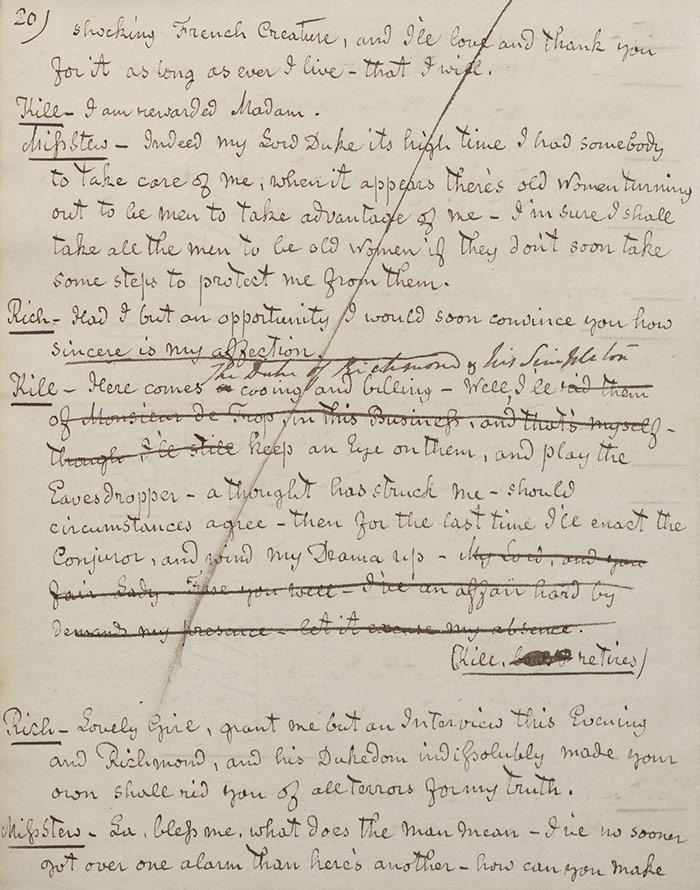

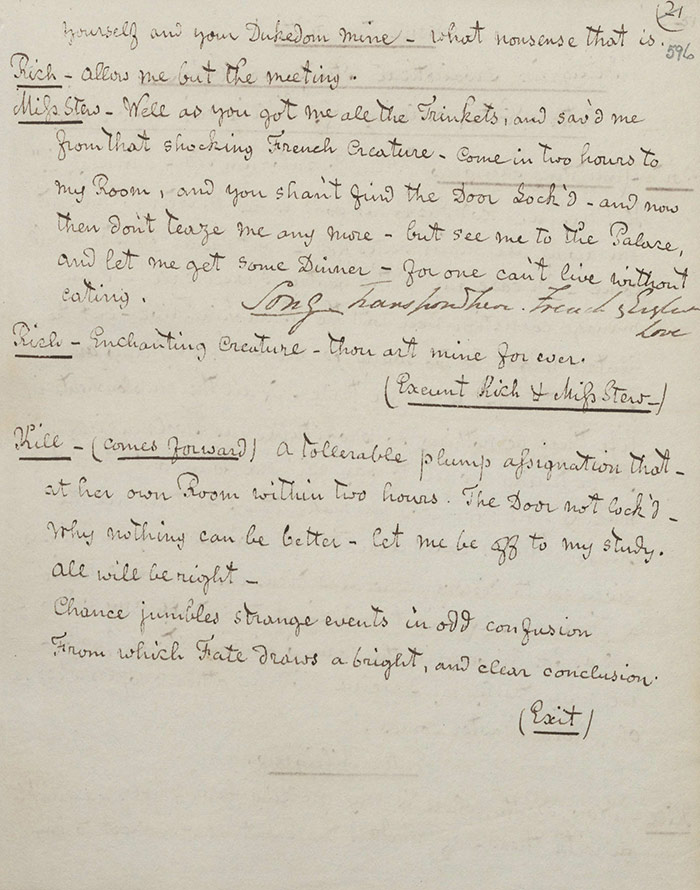

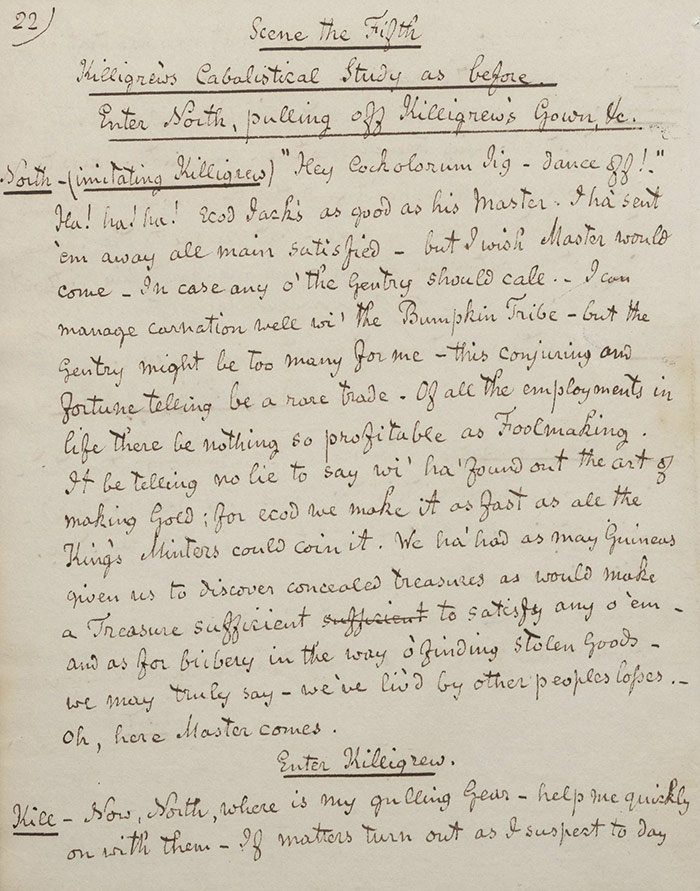

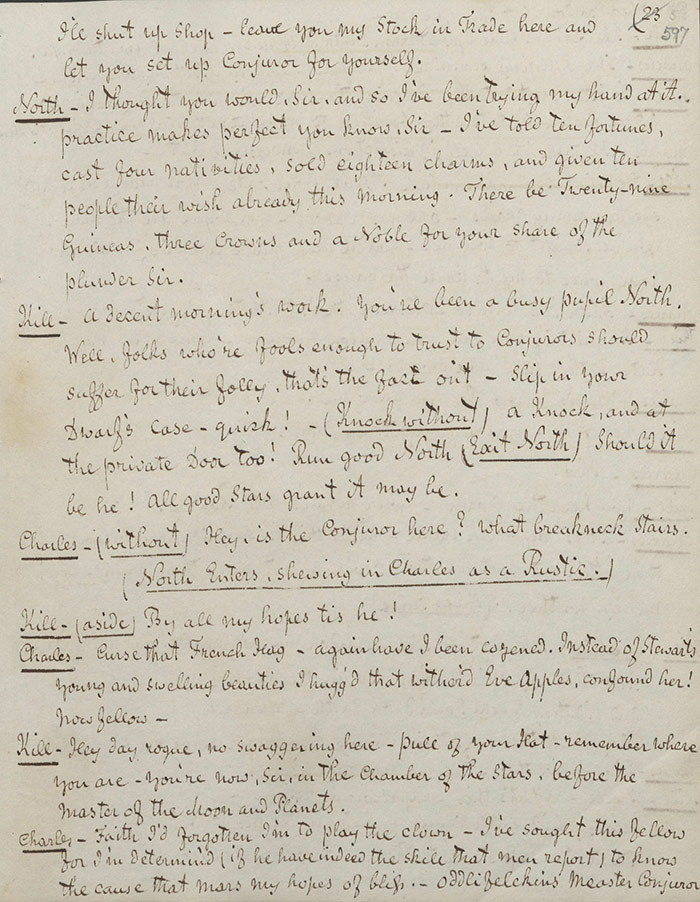

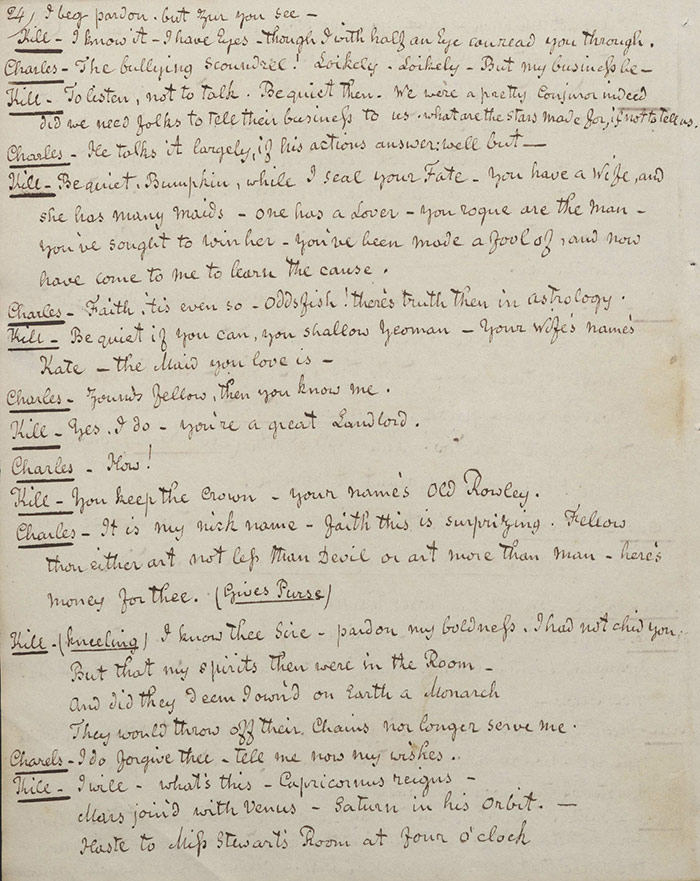

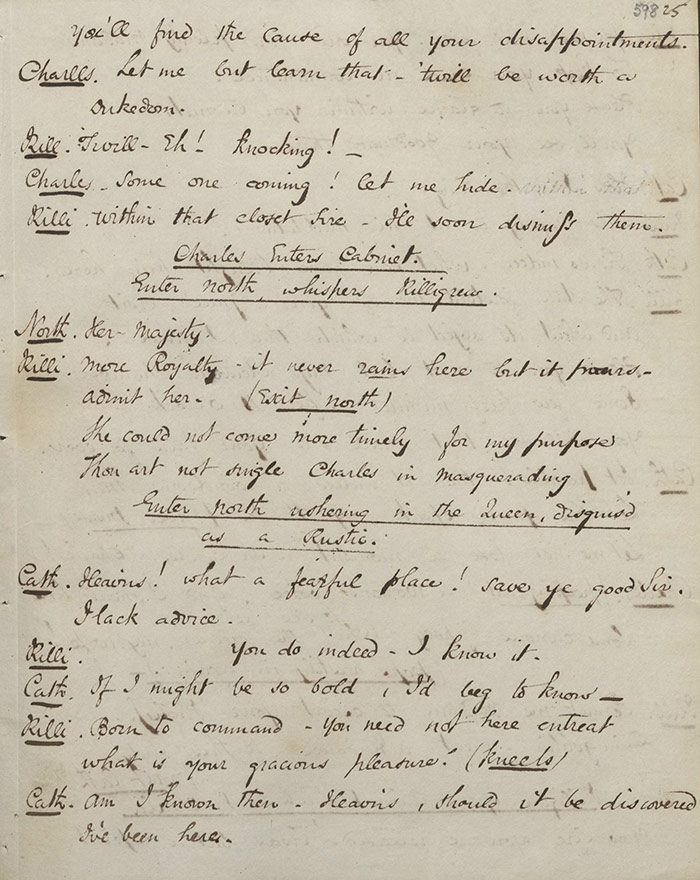

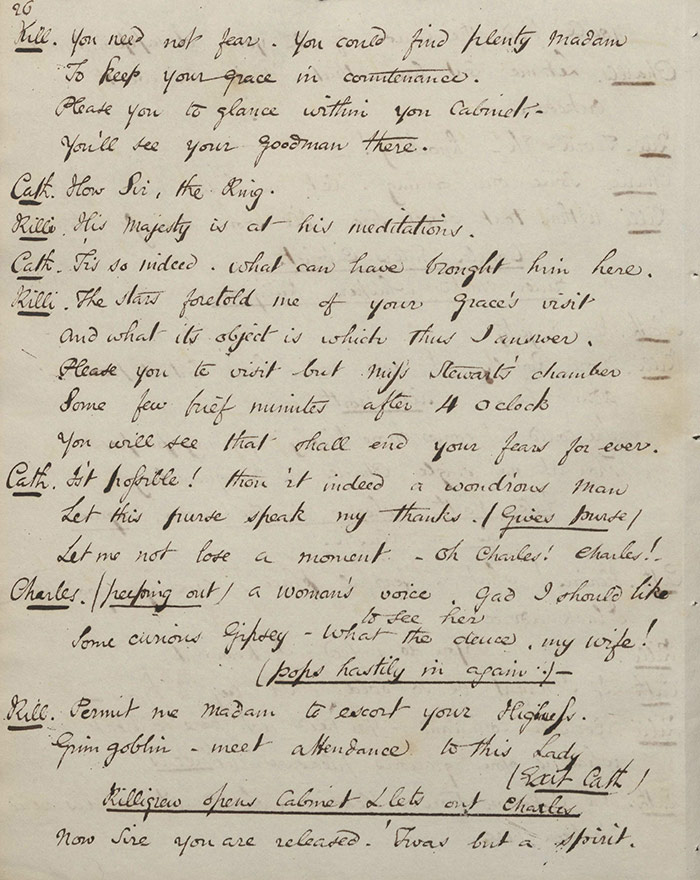

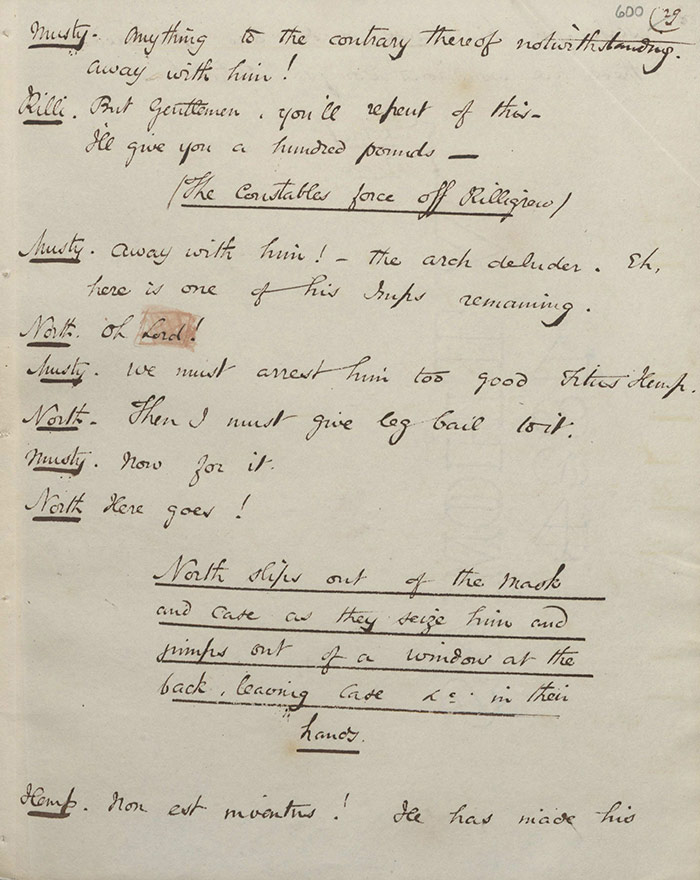

The King, disguised as a rustic but recognized by Killigrew, comes to see the German Professor (f.596v). Killigrew directs him to Miss Stewart’s room at four o’clock – to coincide with Richmond – to find the cause of his disappointment. A knock on the door sees the King hide in a cabinet as the Queen enters, also in disguise. Killigrew directs her to go to Miss Stewart’s room a little after four o’clock. After they leave, Hemp, Musty, and Constables enter and arrest Killigrew in his guise as a German Conjuror and drag him off to the court.

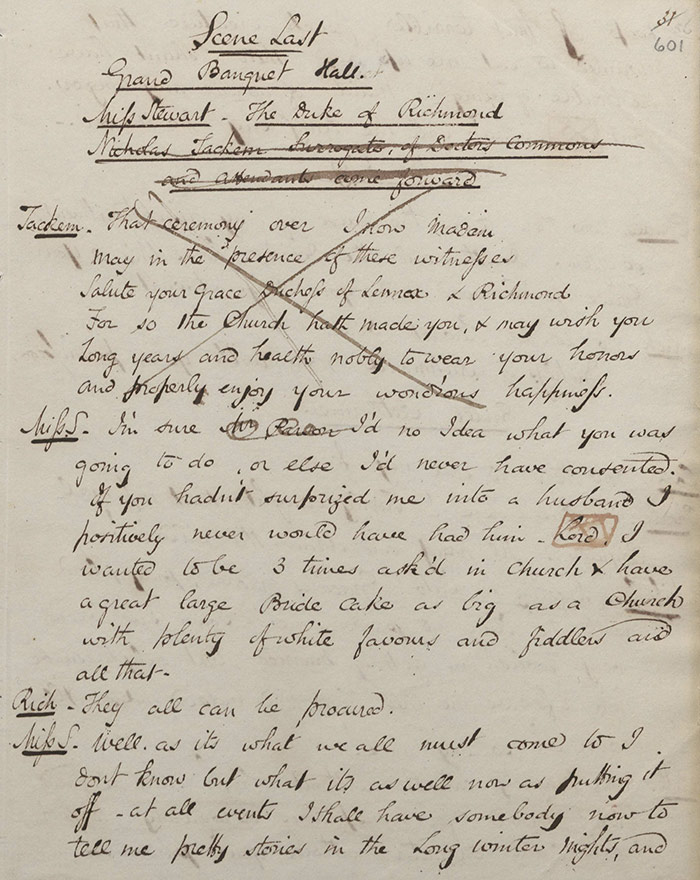

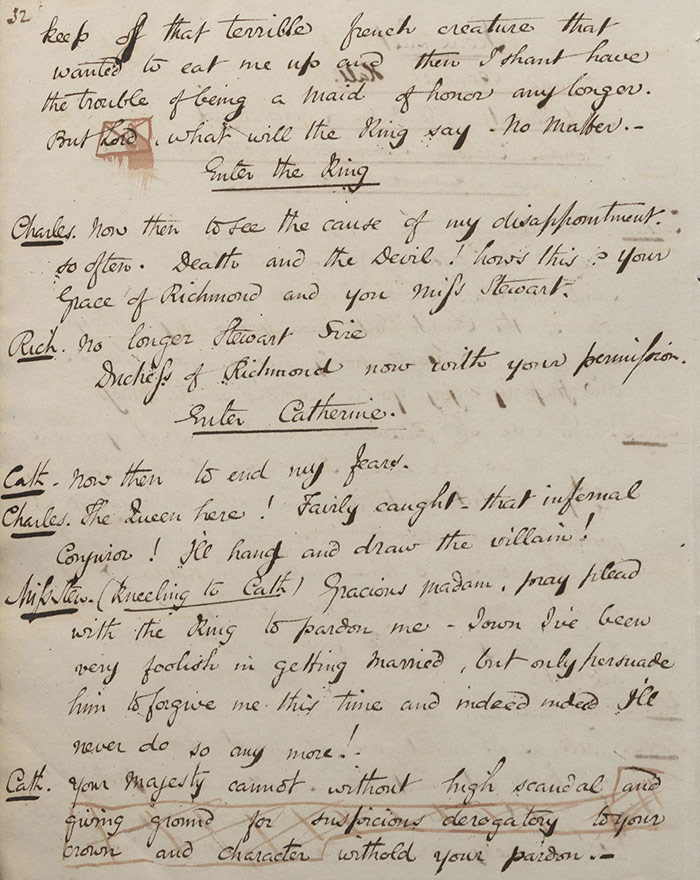

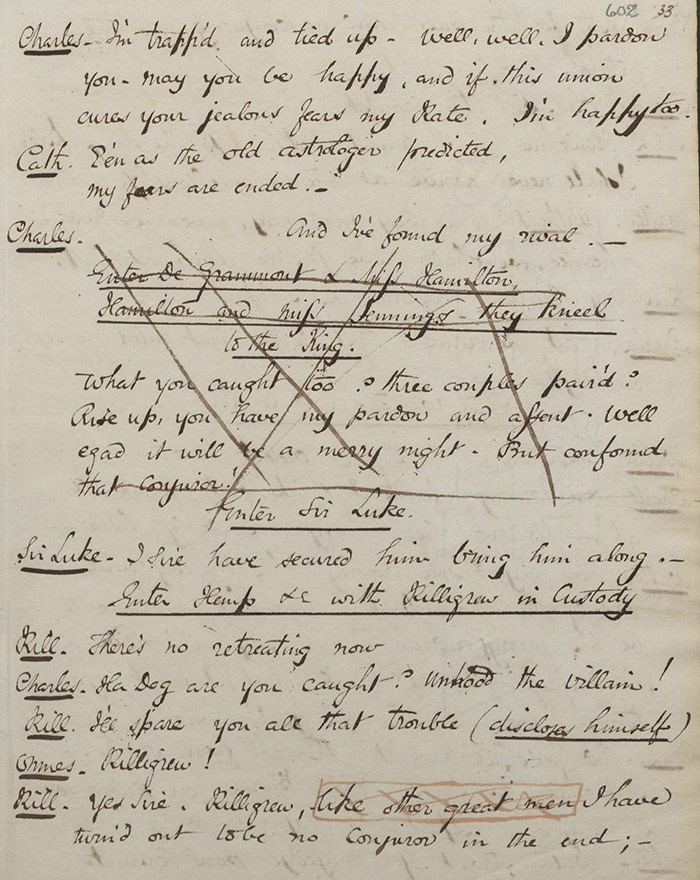

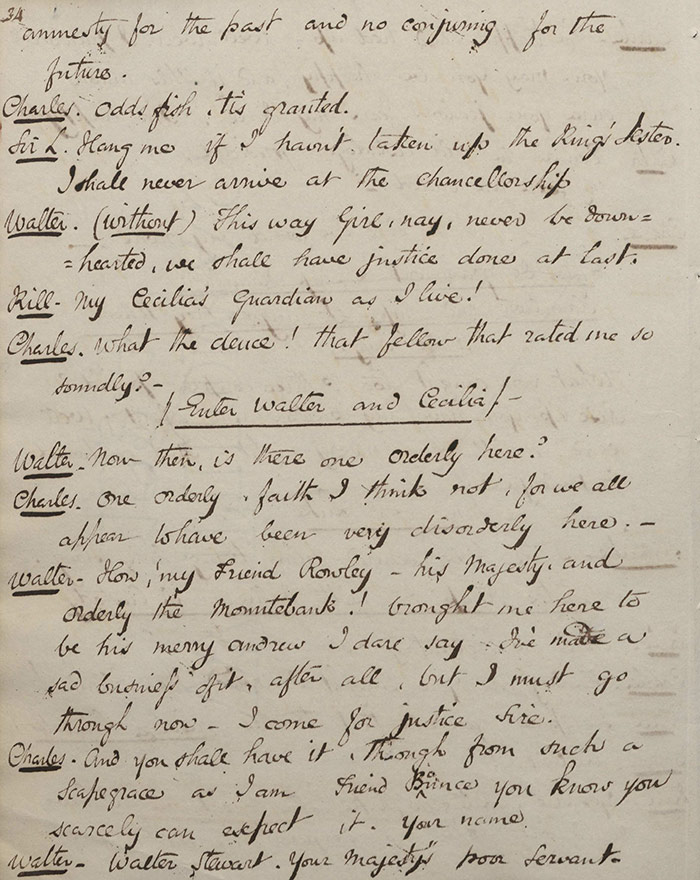

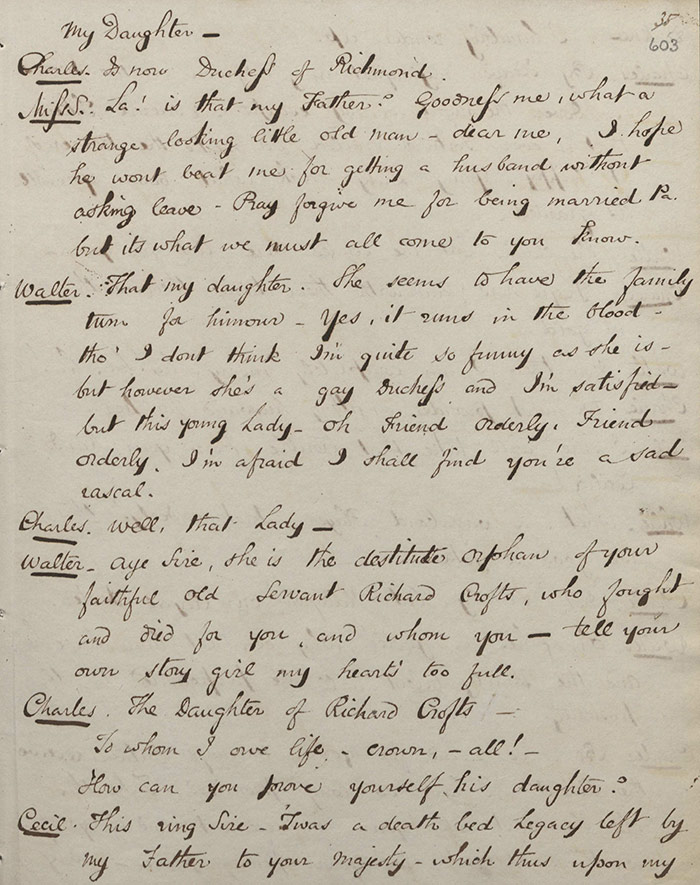

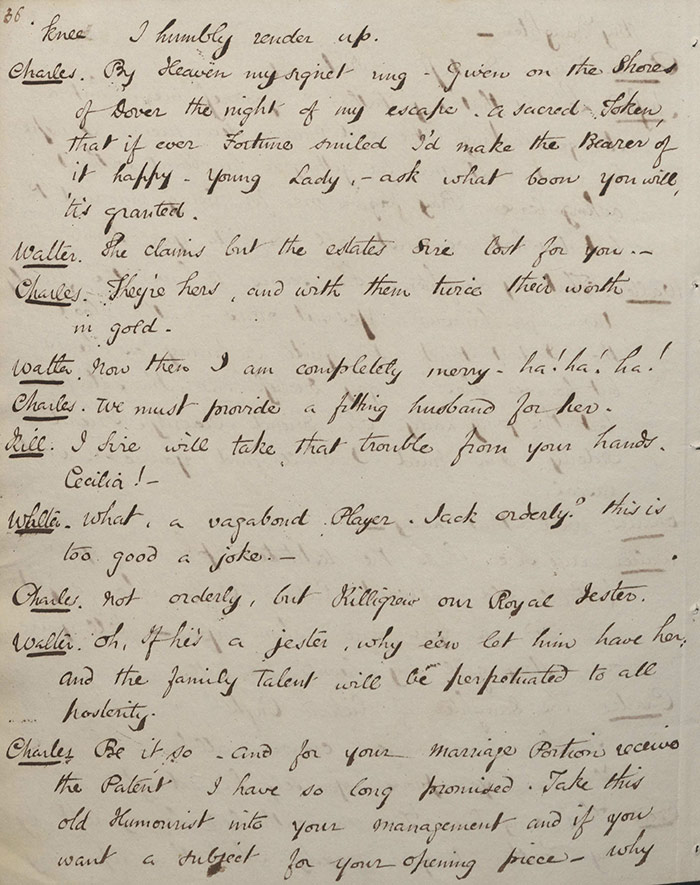

The final scene takes place just after the marriage of Richmond and Miss Stewart (f.601v). Although angered, the King is forced by the Queen to pardon her to avoid suspicions. He is also angry with the conjuror as the Queen has followed him there. Killigrew is brought before him and unmasked and forgiven. Walter appears and meets his daughter. He also pleads the case of Cecilia to the King who is moved at the sight of the daughter of Richard Crofts to whom he owes his life and crown. He approves her marriage to Killigrew, gives them the patent as a wedding gift, and suggests the recent antics as the subject of their opening piece.

Performance, publication, and reception

This was first performed on 10 October 1825 at the Adelphi theatre and was the opening drama of the season under the new management of Frederick Yates and Daniel Terry, who respectively played Killigrew and Walter Stewart. It was accompanied by a prelude The Opening Night and closing 1 act burletta No Dinner Yet. Killigrew was a considerable success that season, performed 25 times up to 14 November (The Adelphi Calendar).

The Times (11 October 1825) heralded the new management team as one that proposed ‘to place its entertainments upon somewhat a higher footing than they have hitherto occupied’. The reviewer was also cautiously impressed with the refurbishments that were carried out:

The House had been newly embellished, not without some taste, and apparently at considerable expense; fresh linings and gildings having been afforded to the boxes, lamps and chandeliers to the stage, and a looking-glass of large dimension, besides crimson cushions in abundance, to the refreshment-room.

As regards the comic burletta itself, the paper commented it was ‘founded upon some adventure, or reputed adventure, of that pleasant monarch in one of his country excursions’. ‘Upon the whole’, the review concluded of the night’s entertainments, ‘they were decidedly of a higher order than any which had been before presented at the theatre; and were received with general satisfaction by an audience crowded in all parts’. The Drama ([April] 1825) also insisted that it was ‘one of the best this theatre has produced’. The Examiner (16 October 1825) found that ‘as a piece it wants a proper connexion’ but ‘ there were several points of real comedy’.

On the other hand, Literary Gazette (15 October 1825) took a rather dimmer view, not deigning to engage with the particularities of the non-patent entertainment at all:

On Monday night the Adelphi Theatre opened under a new management. We seldom like to risk the stuff and ribaldry of the minor places of resort; and the less regret doing so in this case, since we see that the newspaper puffs state the Entertainments to be fully equal to Tom and Jerry!! Of course they must possess high attractions, if they can compare with that low and deservedly popular representation of genuine St. Giles’s life.

It is worth noting that Covent Garden also staged a comedy on Charles II at the same time (Literary Gazette, 22 October 1825). This was probably John Howard Payne’s Charles II; or, the Merry Monarch (1824).

Commentary

This three-act drama shows a number of excisions, emendations, and some insertions made in red pen by Colman. There are also a large number of significant excisions made in black pen but we can be fairly certain that these were made for dramaturgical reasons in order to shorten the piece.

The theatrical treatment of royal personages was always a delicate affair and this was particularly true for both Charles I and his son. In the case of Charles I, the rationale is fairly clear – the depiction of an executed king, particularly in the wake of Louis XVI, was never a sanctioned topic for the drama as Mary Russell Mitford and others could testify. With regard to Charles II, there was a degree of licence although, as this play shows, it was his reign’s association with licentious behavior that would make an Examiner wary.

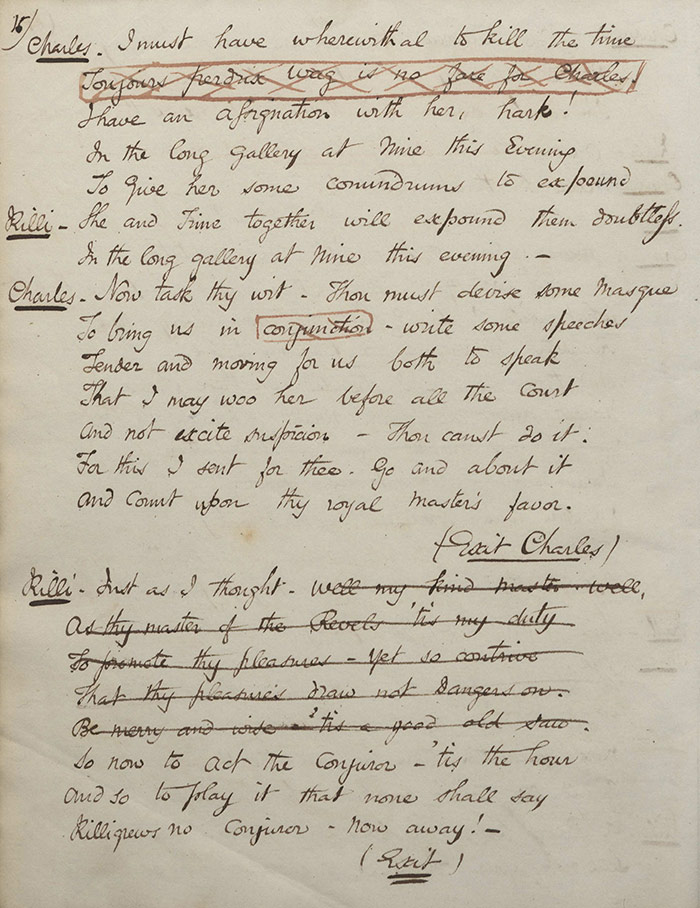

Certainly Colman was quick to pounce on passages that suggested a less than moral court. References to flattering or vacuous courtiers and, in particular, hints that maids of honour might indulge in less than chaste behaviour were removed (e.g. f.548r, f.548v, f.550v, f.560v, f.566v). Even the most oblique hint that the court was not a bastion of decorous behavior could be gone: SIR LUKE: ‘[…] we are bound by virtue of our sticks to keep good order and morality throughout the Palace’ (f.550v). When Killigrew adopts his guise as a German conjuror, his astrological trope ‘aries in virgo’ is also deemed surplus to good taste’s requirements (f.563r). When Mlle de la Garde attempts to convince Miss Stewart to capitulate to the king’s desire, a substantial speech suggesting that the king could get a divorce and that she could do as she pleased as queen is also firmly struck out (f.590r).

As for the monarch himself, Colman also exercised vigilance. The excision of Charles’s comment to Killigrew ‘Toujours perdrix wag is no fare for Charles’ (f.553v) is a little oblique but it certainly seems to point towards a taste for sexual variety of which Colman disapproved. Phrasing that suggested the physical act of sexual intercourse are removed on the same folio ‘Thou must effect some Masque To bring us in conjunction’. His lascivious desire that Venus appear unclothed in the masque is also firmly struck out (f. 581r); however, we may note that his frustrated complaint, after mistaking Miss Stewart for Mlle de la Garde, that ‘Instead of Stewart’s young and swelling beauties I hugg’d that wither’d Eve Apples’ remains unmolested (f.597r). And, even in a farce such as this, his authority could not be questioned: a reprimand from the ‘saucy varlet’ Killigrew is struck out (f.575r) as is a suggestion from Walter that he has not behaved honourably towards someone to whom he had a duty of care (f.576v-577r).

A word that seemed to bother Colman quite a bit was ‘intrigue’, which he struck out in a number of places. He removes examples on (f.560r), (f.560v), (f.561r), and (f.561v) before, exasperated, inserted a note beside the last example ‘soften the word Intrigue’. An instance of the term remains on (f.563r) suggesting that it was simply the overuse of the term that was the problem rather than simply the use of it. On the other hand, he seemed to have no issue with the word ‘assignation’ which appears on numerous occasions, and often in close proximity to ‘intrigue’. We might speculate that ‘intrigue’ hints at political as well as sexual shenanigans, and possible a causative relationship between the two, to explain Colman’s antipathy for that particular term.

As always with Colman, religious references are excised. Gone are a reference to the loaves and fishes (f.551r) and there are a large number of oaths such as ‘Oh Lord’, ‘Damn’, ‘Heaven’ ‘God’ struck out e.g. (f.552v), (f.563v), (f.573r), (f.577v), and (f.579r). Killigrew’s reference to the apostle Luke while gulling Sir Luke is also removed [f.563r]

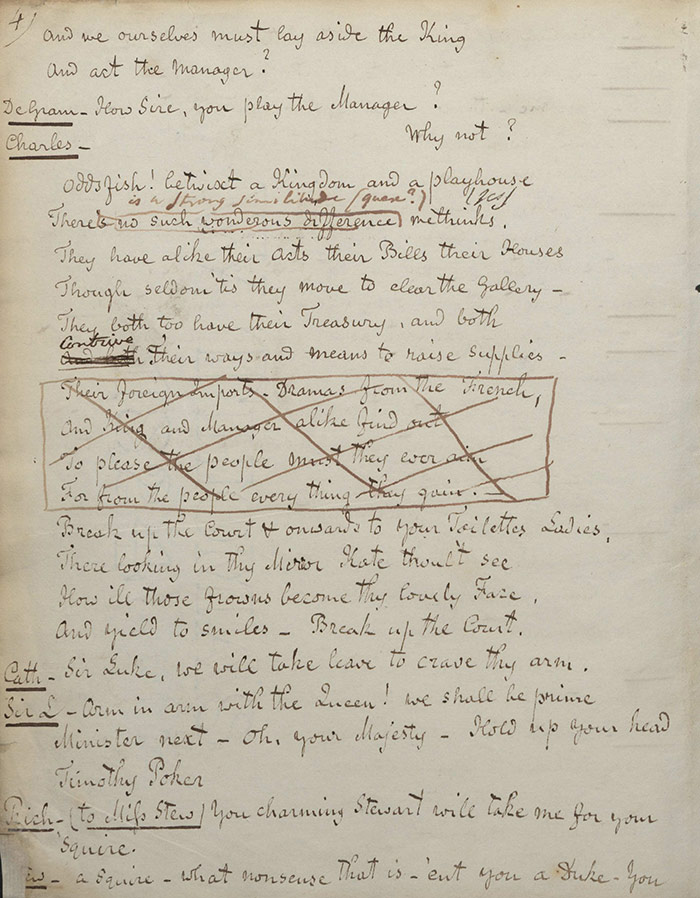

Given the topicality of the play – the granting of the royal patent to Killigrew – a speech from Charles on which Colman deployed his red pen is worth reproducing in full:

Why not?

Oddsfish! betwixt a Kingdom and a playhouse

There’s no such wondrous difference

They have alike their acts their Bills their Houses

Though seldom ’tis they move to clear the Gallery –

They both to have their Treasury, and both

Contrive their ways and means to raise supplies

Their foreign Imports – Dramas from the French, (f.571v)

And King and Manager alike find out

To please the people must they ever aim

For from the people every thing they gain.

The fascinating alternative half line offered by Colman (?) suggests that while the playhouse could not be equated absolutely with the kingdom, it was acceptable to state that there were some parallels. The deletion of references to French cultural influence and democratic principles are rather more predictable. As the drama closes, the Examiner also saw fit to excise a direct comparison that Killigrew, the duplicitous trickster, made between himself and ‘other great men’ (f.602r), trying to maintain the distinction between the worlds of theatre and politics.

Further reading

The Adelphi Calendar

https://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/m25d.htm

The Drama; or, Theatrical Pocket Magazine [April] 1825

[Periodical accessed through Proquest Historical Newspaper database which appears to have misdated the scan of this issue; title page not available to check]

John Howard Payne, Charles the Second: or, The Merry Monarch (New York: William Taylor & Co., 1846).

[available on archive.org. See also British Library, Add MS 42866 'Charles 2nd or Royal Waggery', by J. H. Payne. ff. 50-124.)