Jonathan in England (1824) BL ADD MS 42868, ff. 18-57

Author

Richard Brinsley Peake (1792-1847)

Peake was the son of Richard Peake, under-treasurer and later treasurer of Drury Lane and employed by Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Brinsley Peake is probably best known today for his Presumption, or, The Fate of Frankenstein (1824), a melodrama based on Mary Shelley’s novel. By the time he gave evidence at the 1832 Select Committee on Dramatic Literature, he believed he had written about 40 pieces for the stage (for which, unusually, he insisted he had been fairly compensated) and he identified Before Breakfast (English Opera House, 1826) to the committee as his most successful (it had a run of at least 30 nights). He wrote for the minor theatres but was also a significant contributor to Covent Garden’s repertory. He also wrote for periodicals in the 1830s and 1840s, particularly for Richard Bentley’s Bentley’s Miscellany.

Theatre historians have much to be thankful to him for his two-volume Memoirs of the Colman family, published by Bentley in 1841. He was a friend of George Colman the Younger who was, of course, the Examiner for Jonathan in England. Other literary achievements included a novel Cartouche, the Celebrated French Robber (1844). His death in October 1747 was sudden and unexpected; his popularity in dramatic circles ensured there was a public subscription and a benefit performance for his grieving family.

Plot

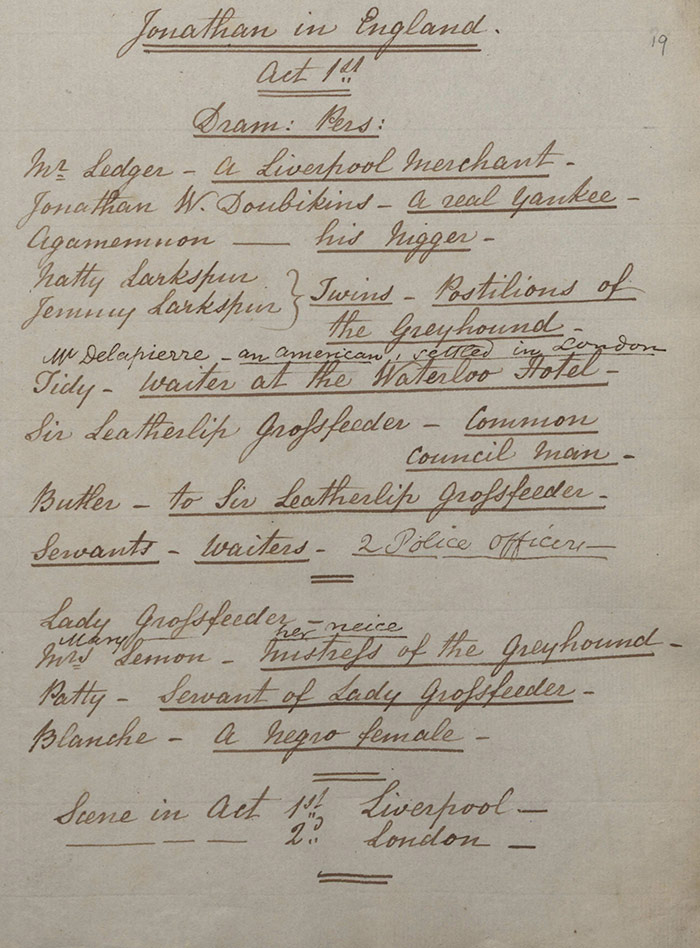

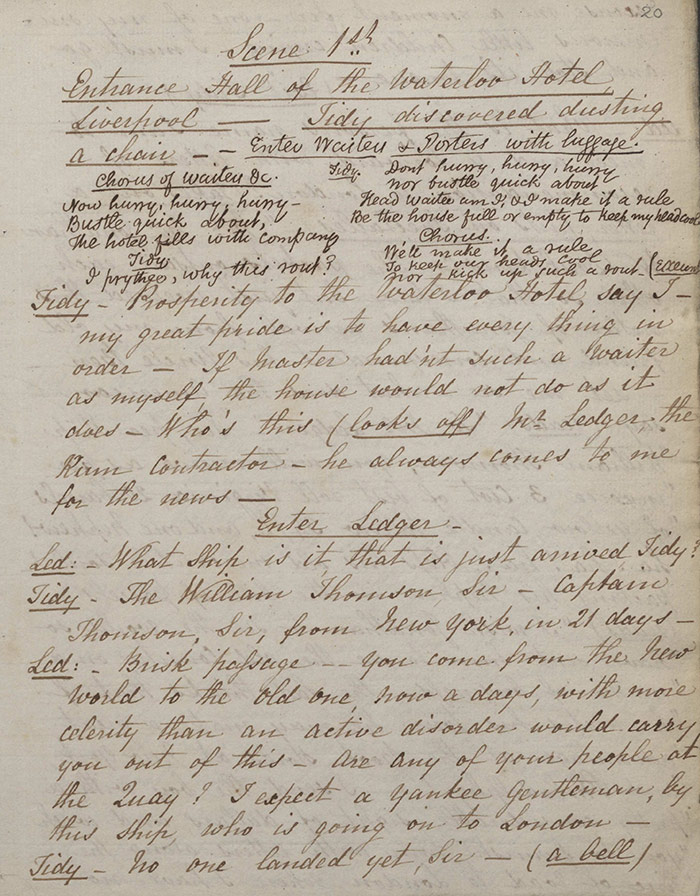

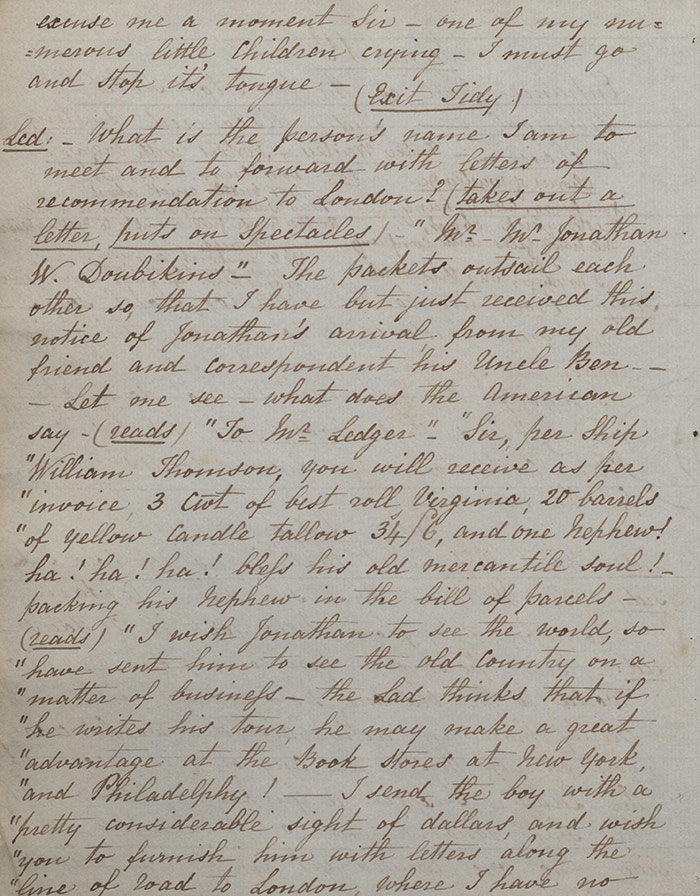

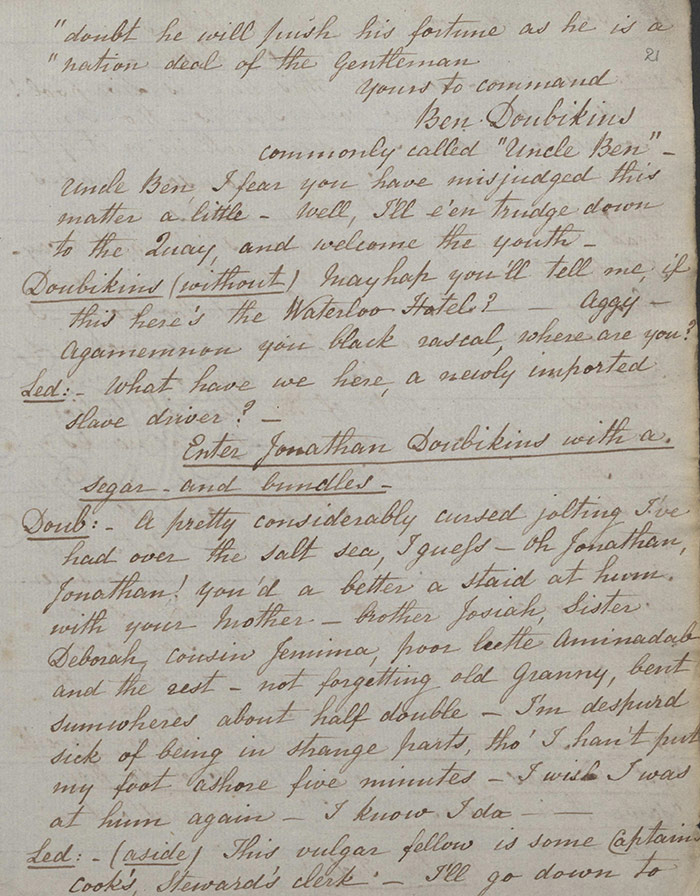

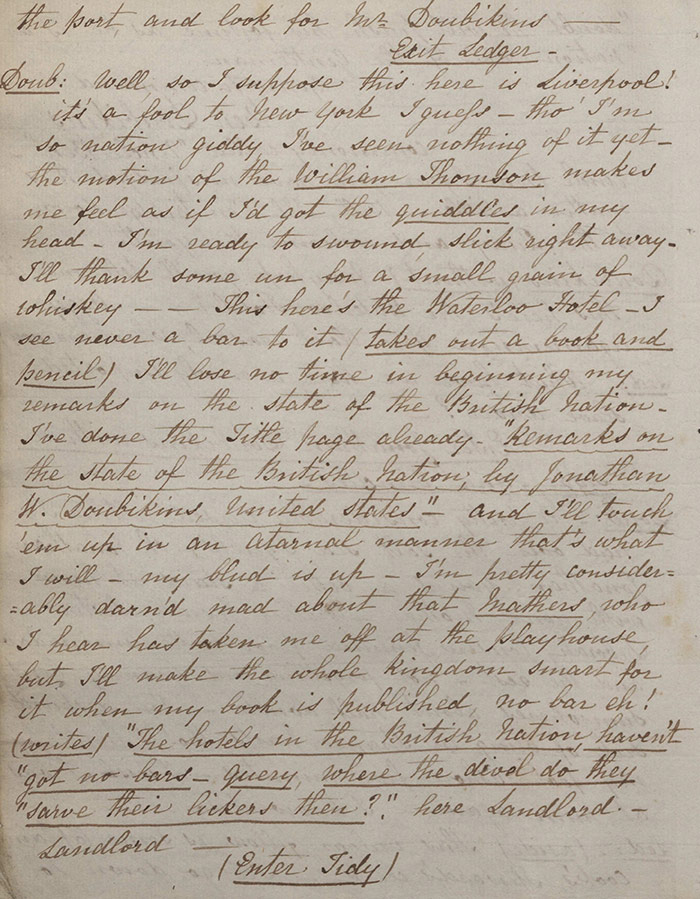

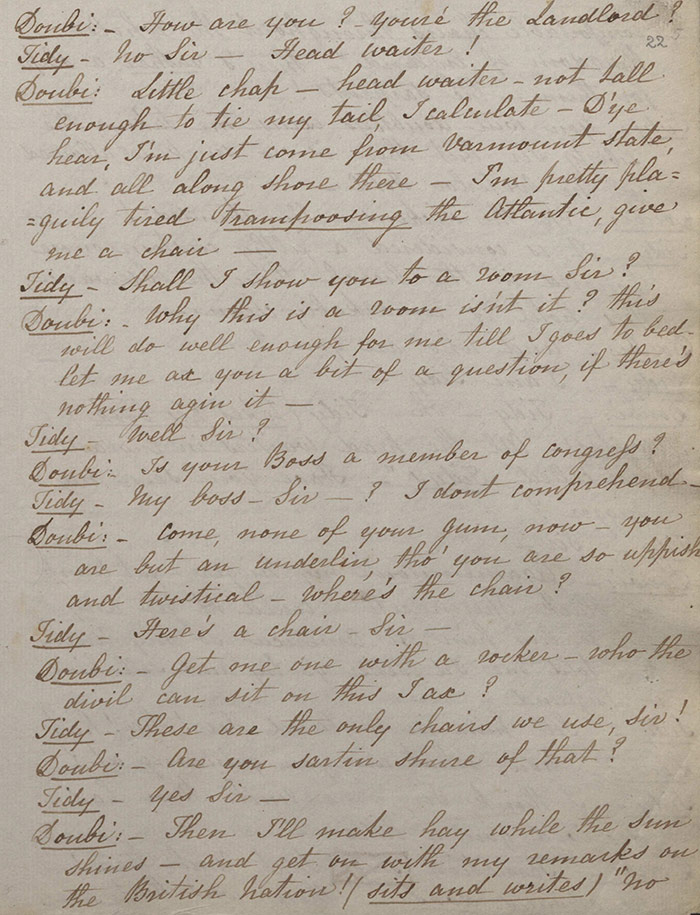

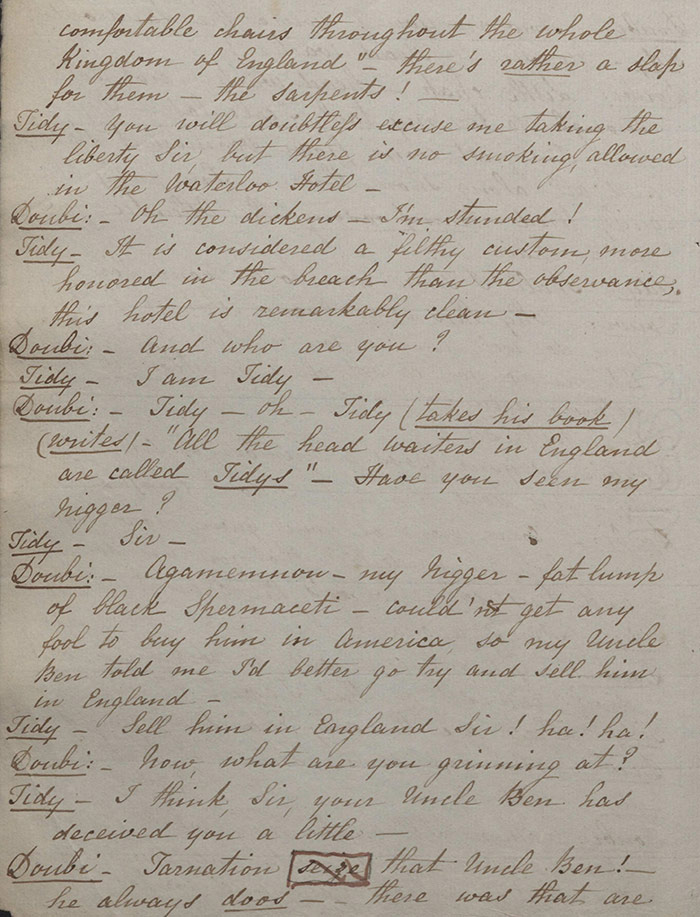

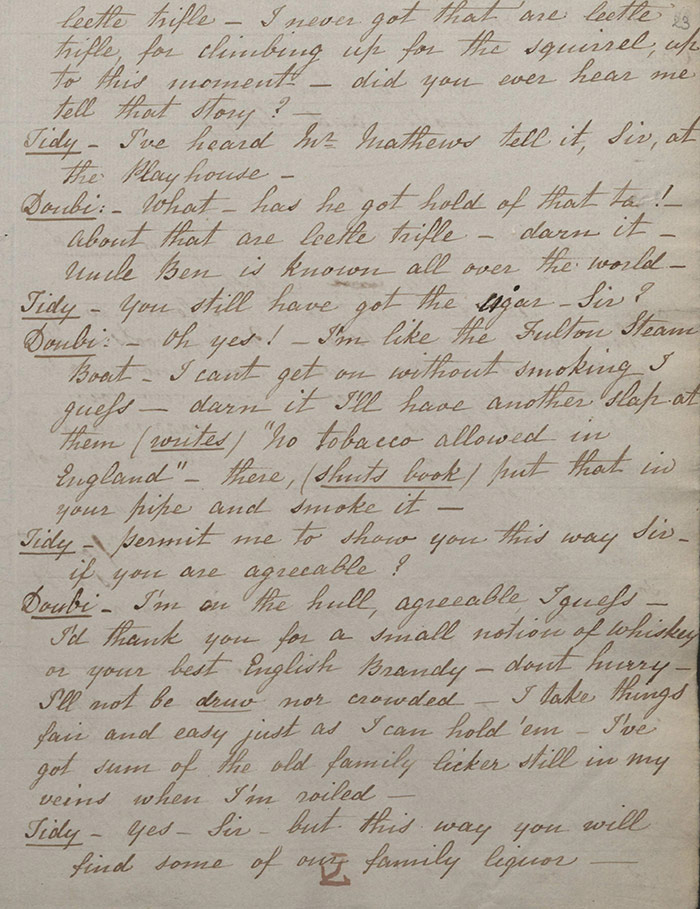

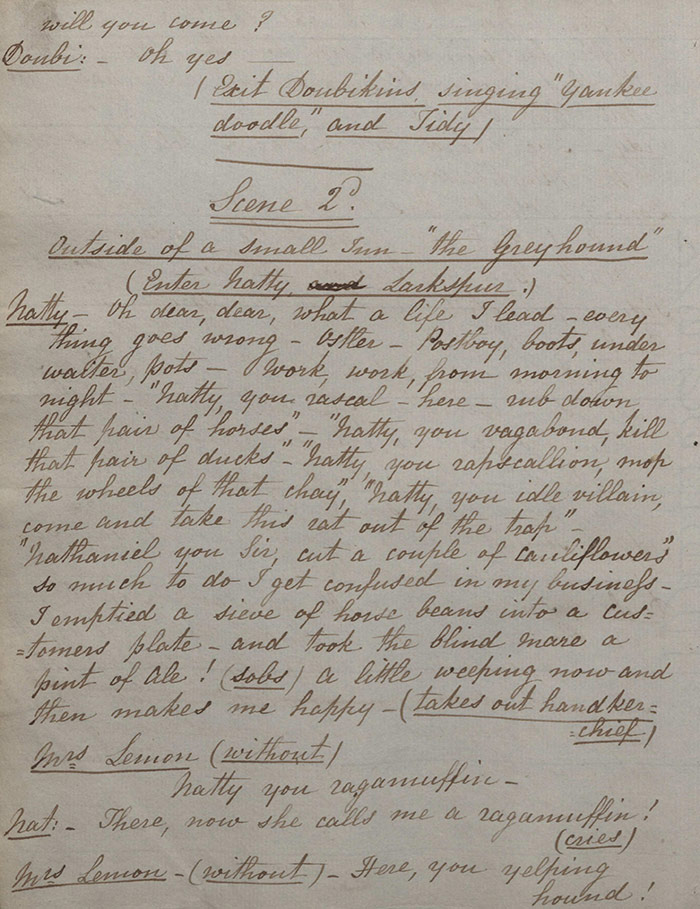

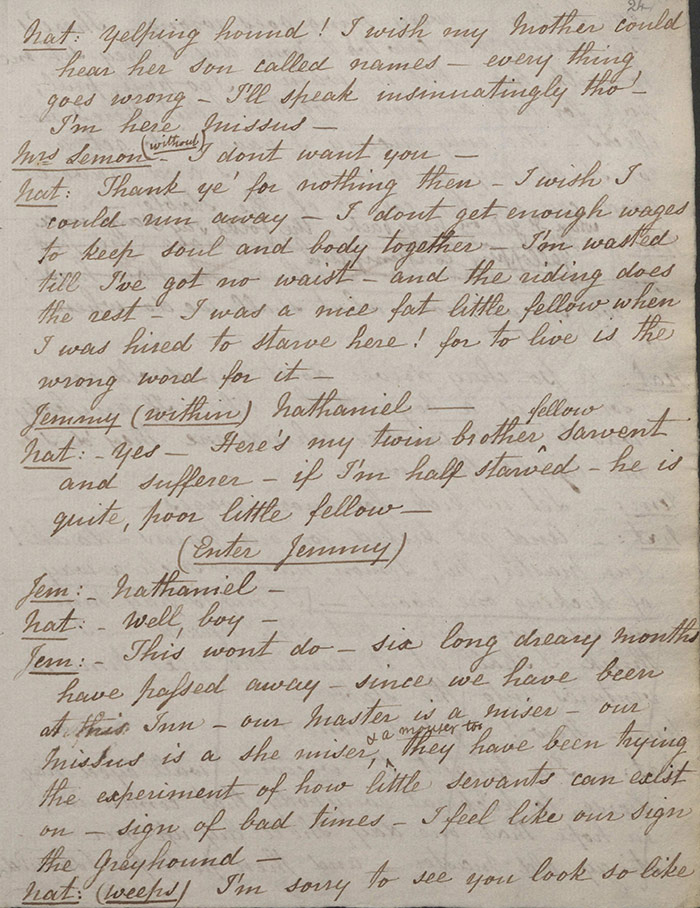

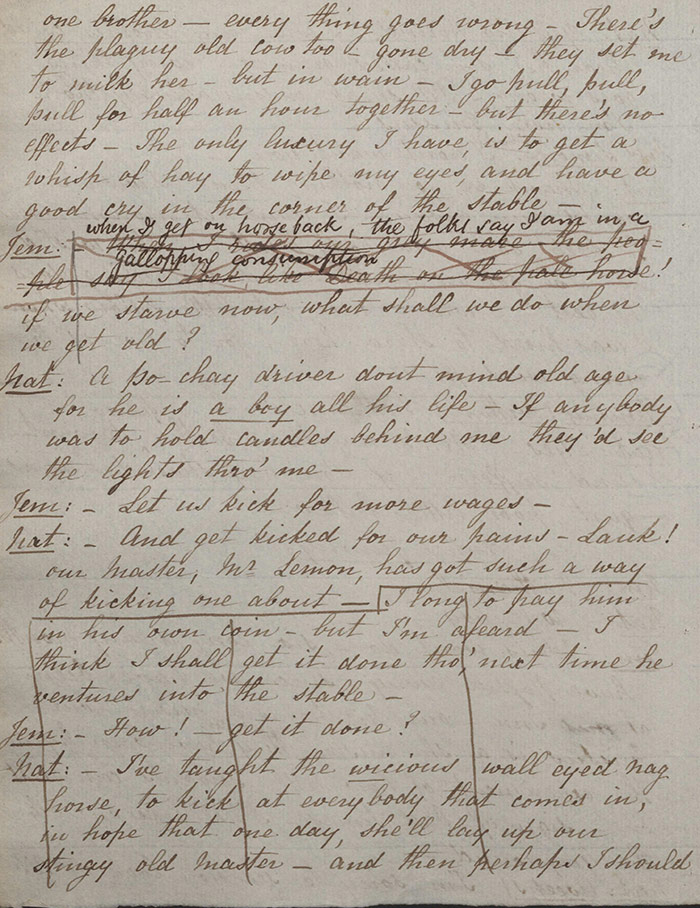

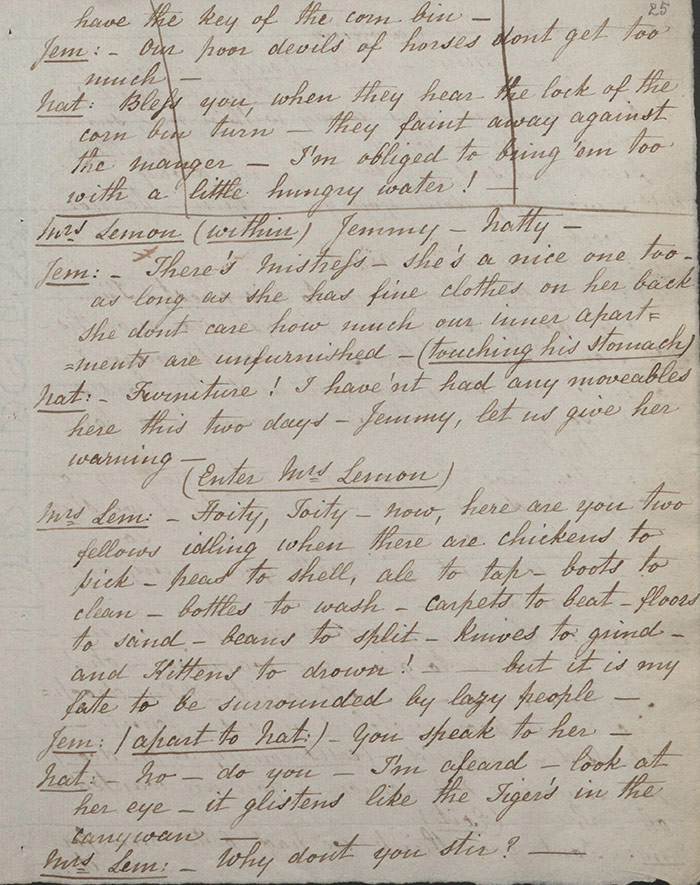

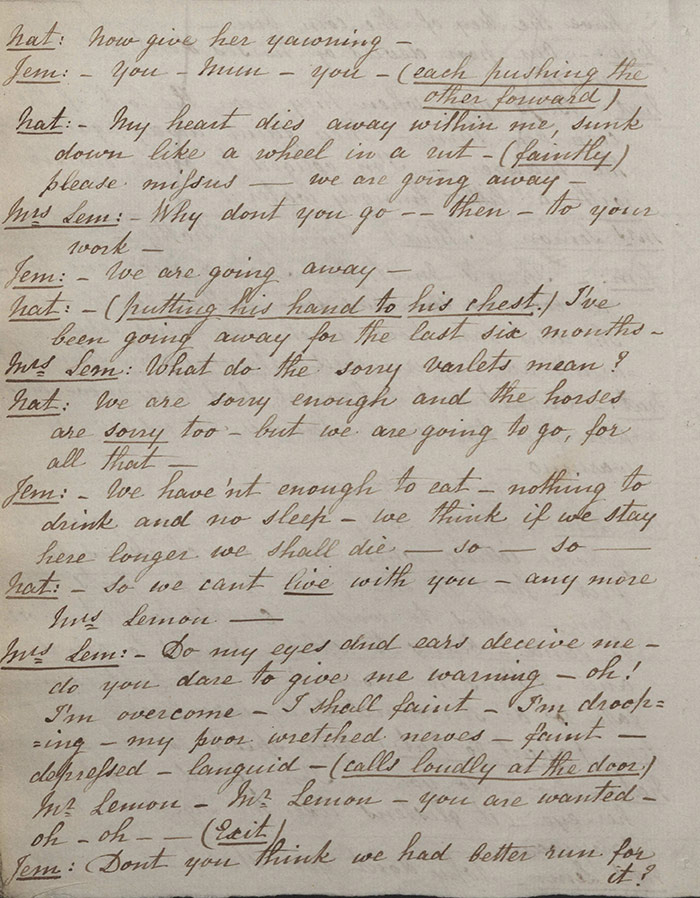

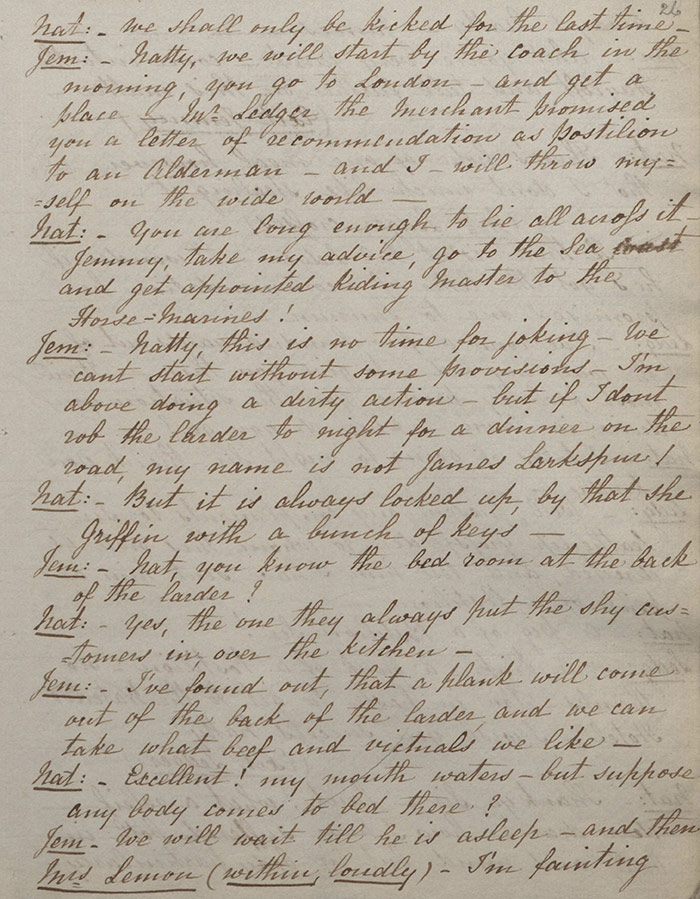

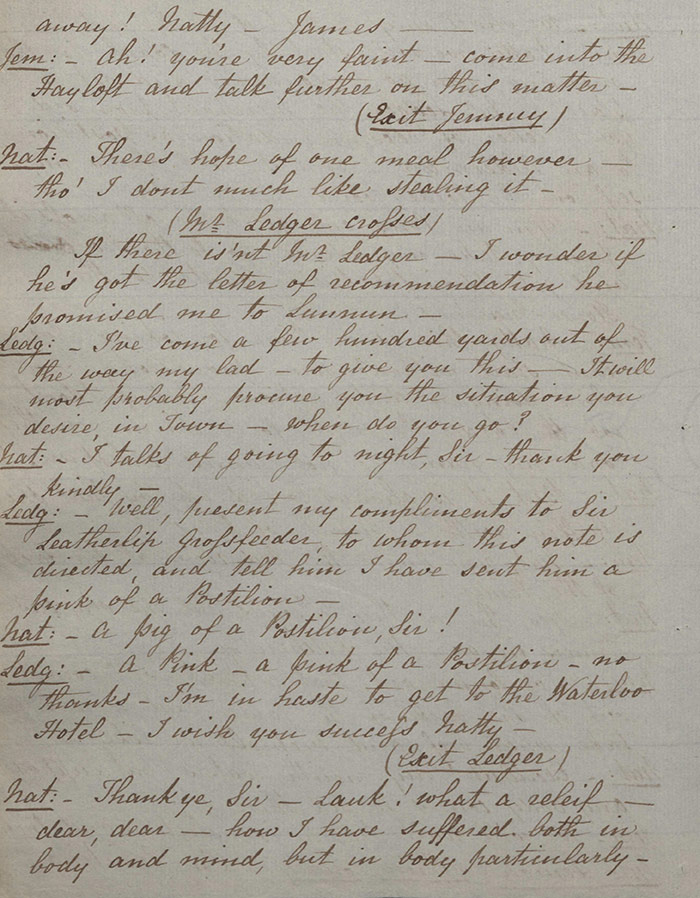

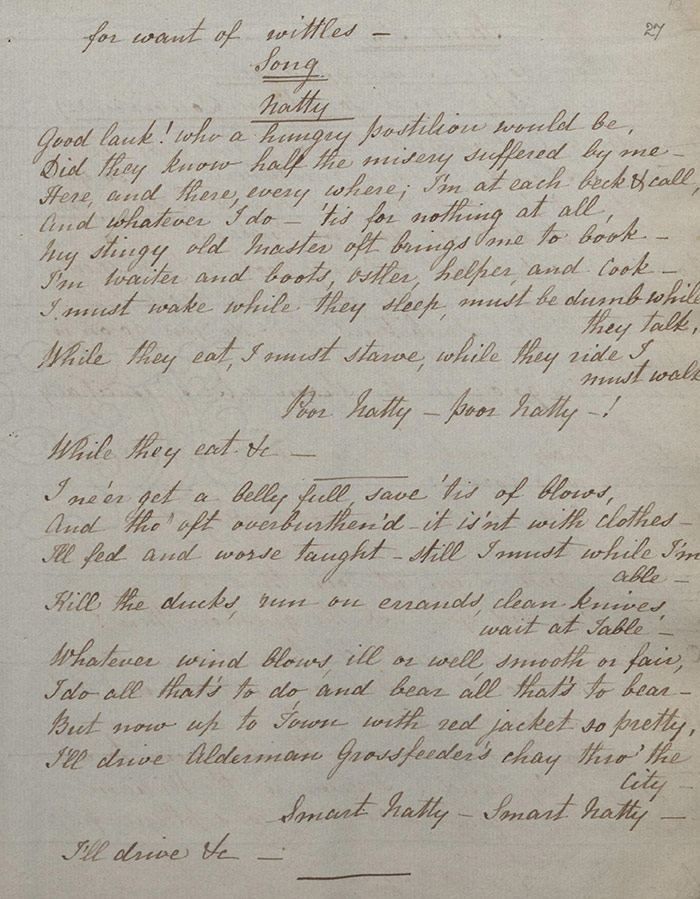

The opening scene takes place at the Waterloo Hotel in Liverpool where a waiter Tidy tells Mr Ledger that a ship from America has just docked. Ledger is expecting Jonathan Doubikins, the nephew of a friend of his. Jonathan is coming to England to see more of the world. He duly arrives but Ledger overhears his homesick speech so believes him to be of the lower orders and leaves to find him elsewhere. Tidy returns to find a disconsolate Jonathan who proceeds to record in his Observations on the British Nation various imagined shortcomings. Jonathan asks Tidy whether he has seen Agamemnon, his black slave whom he has brought to England to sell, much to Tidy’s amusement. Tidy eventually takes him elsewhere for a drink. Outside a small inn, the second scene sees Natty and Jemmy, two of the inn’s servants, bemoan their fate, working for the miserly Mr and Mrs Lemon (f.23v). They resolve to leave, plan to steal some food that night, and give their notice to an aghast Mrs Lemon. Natty is heading for London and Mr Ledger gives him a letter of recommendation for Sir Leatherlip Grossfeeder.

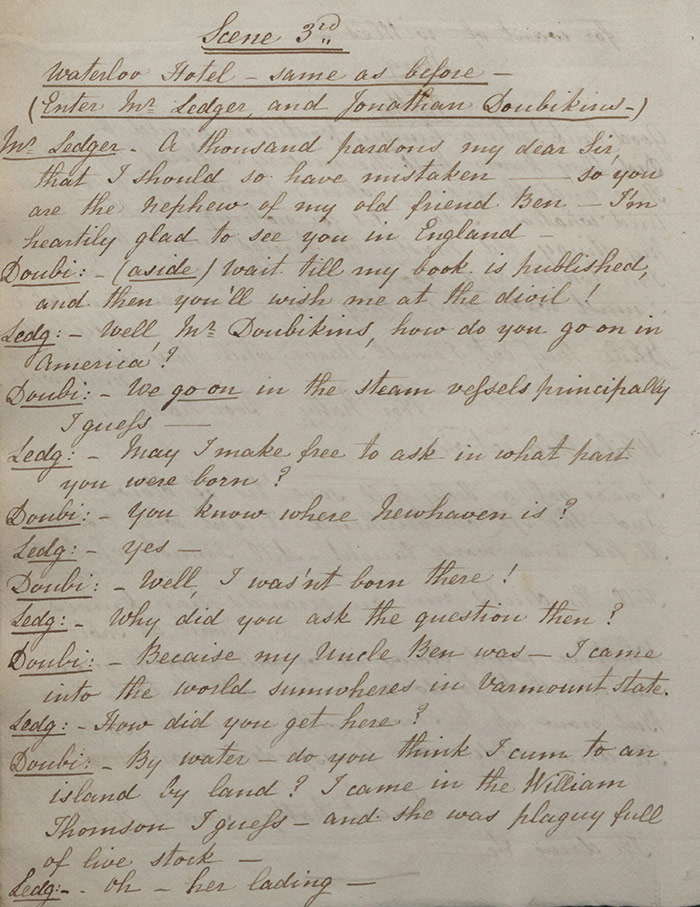

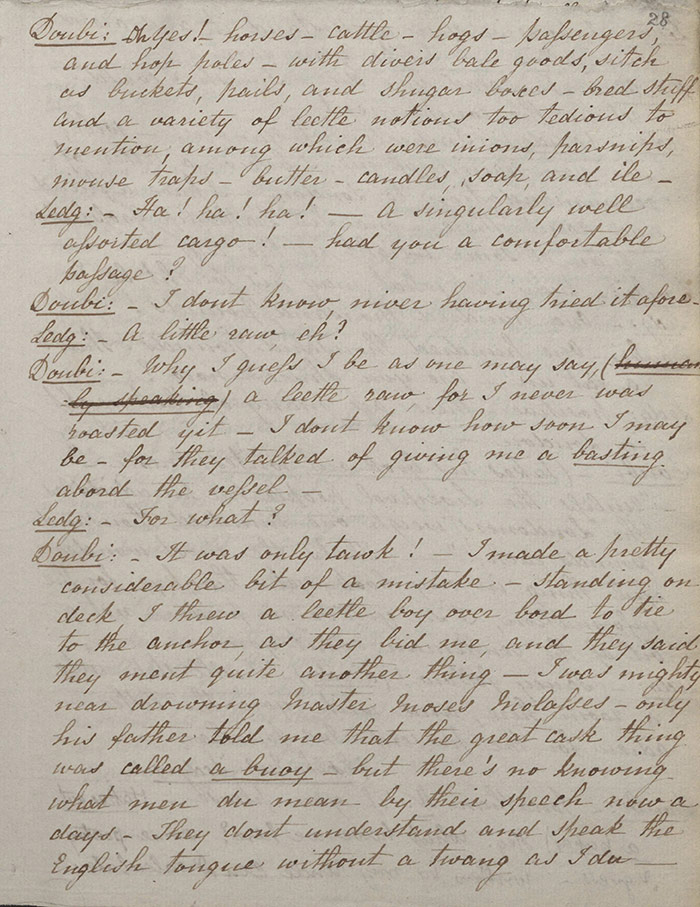

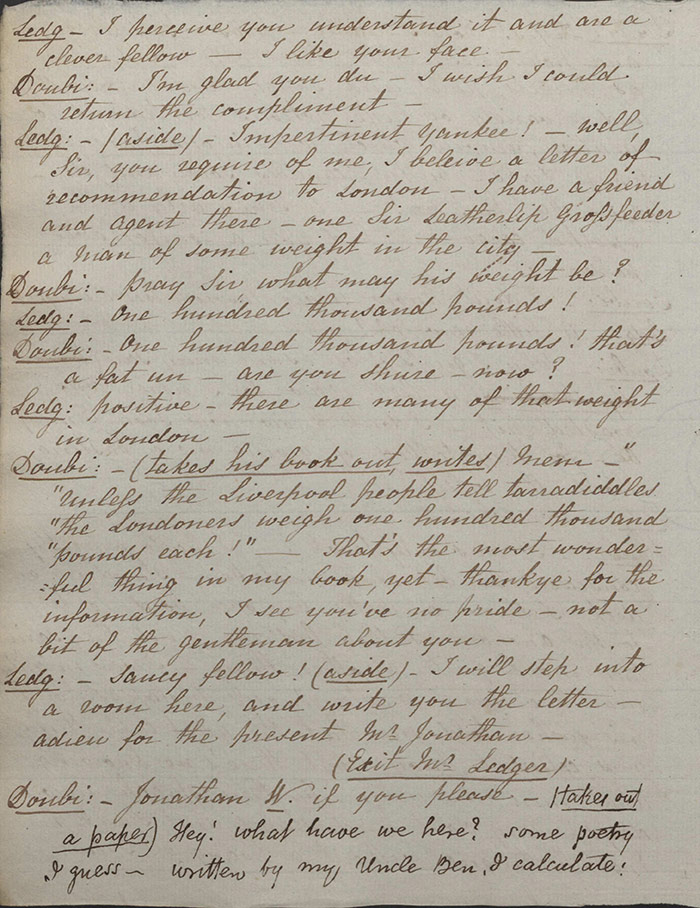

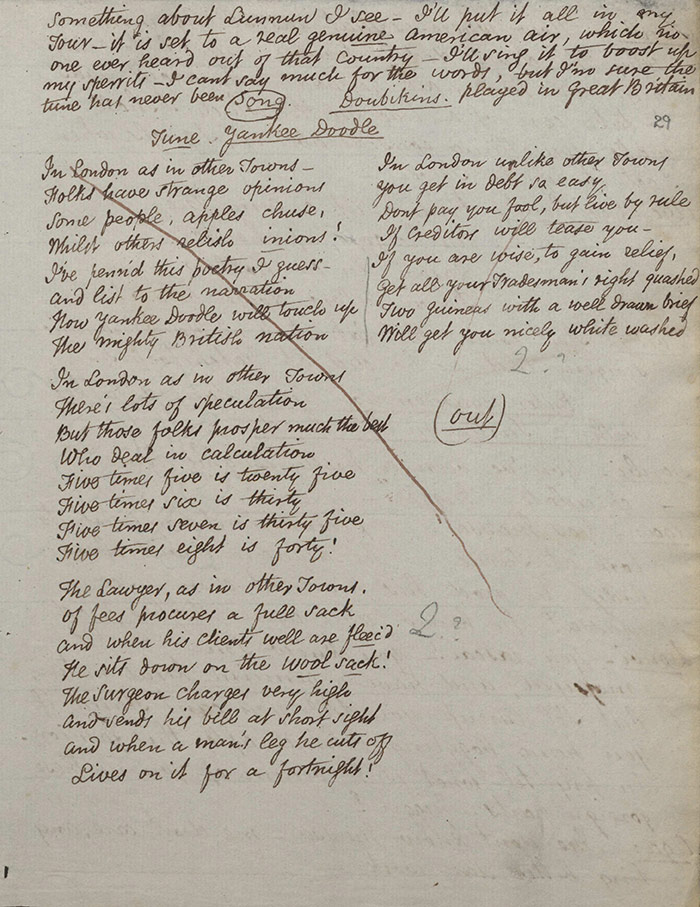

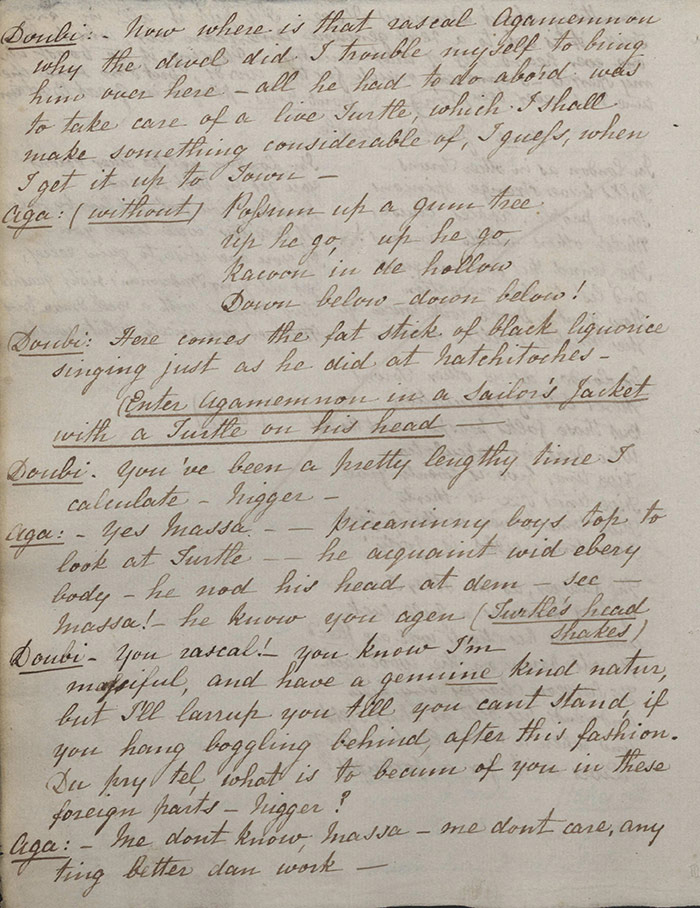

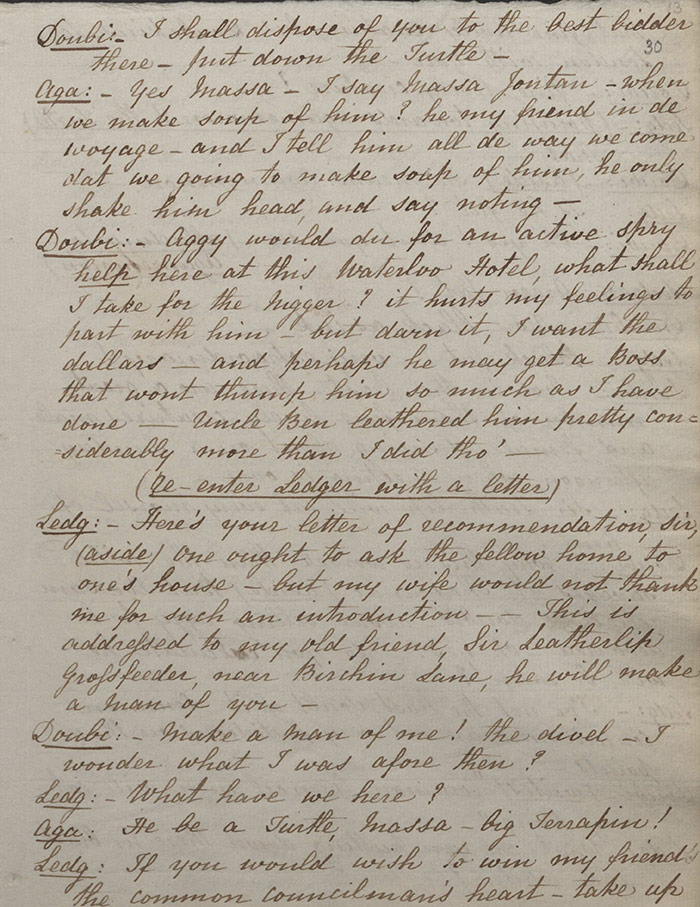

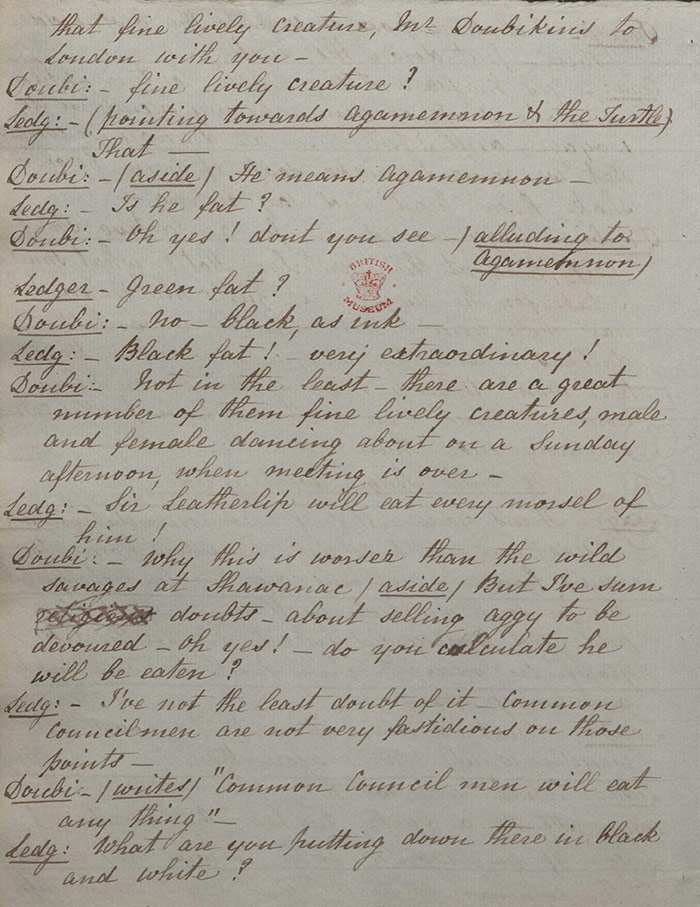

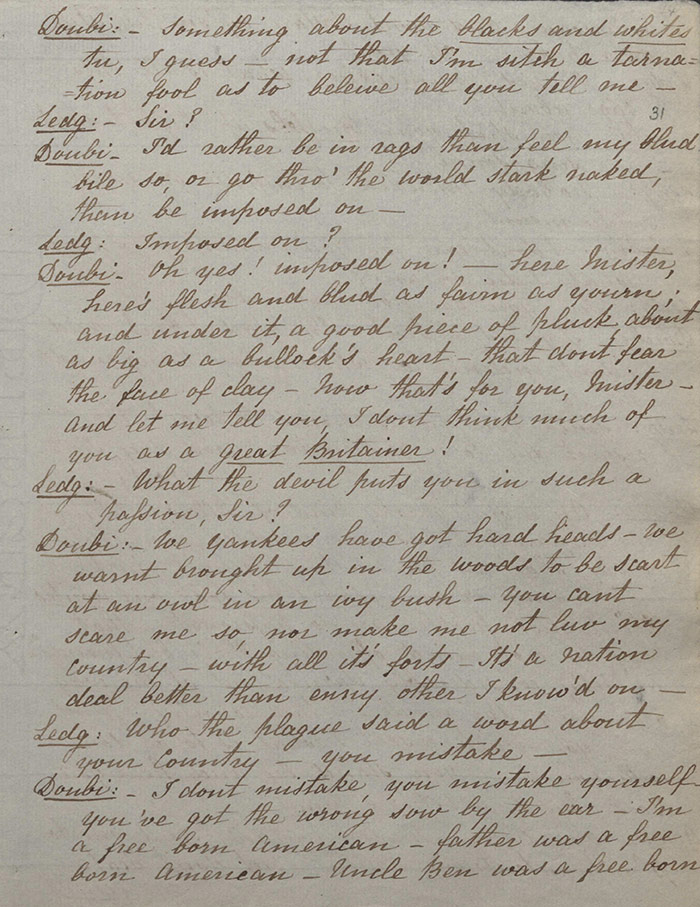

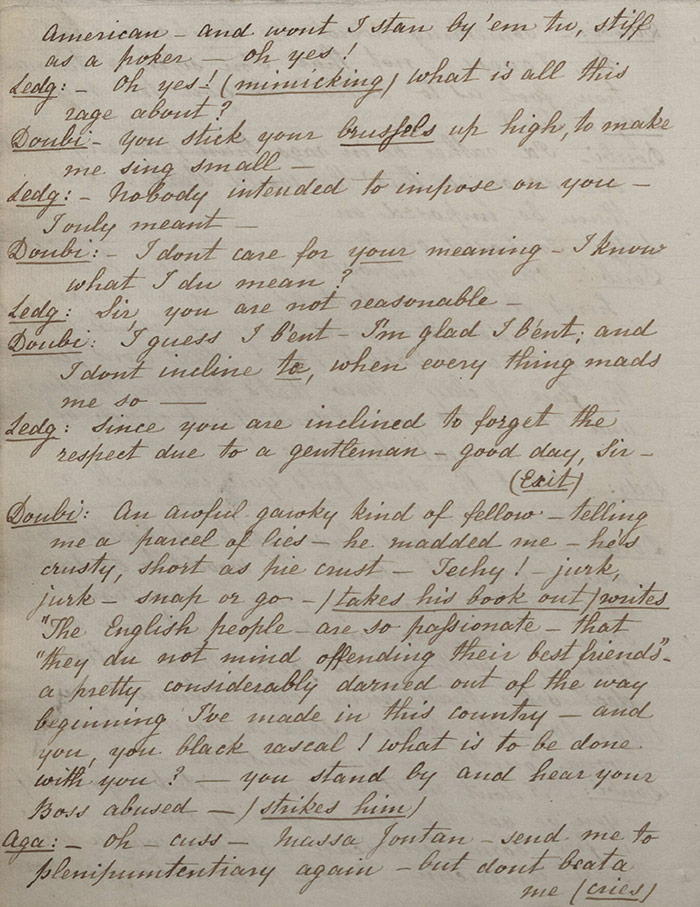

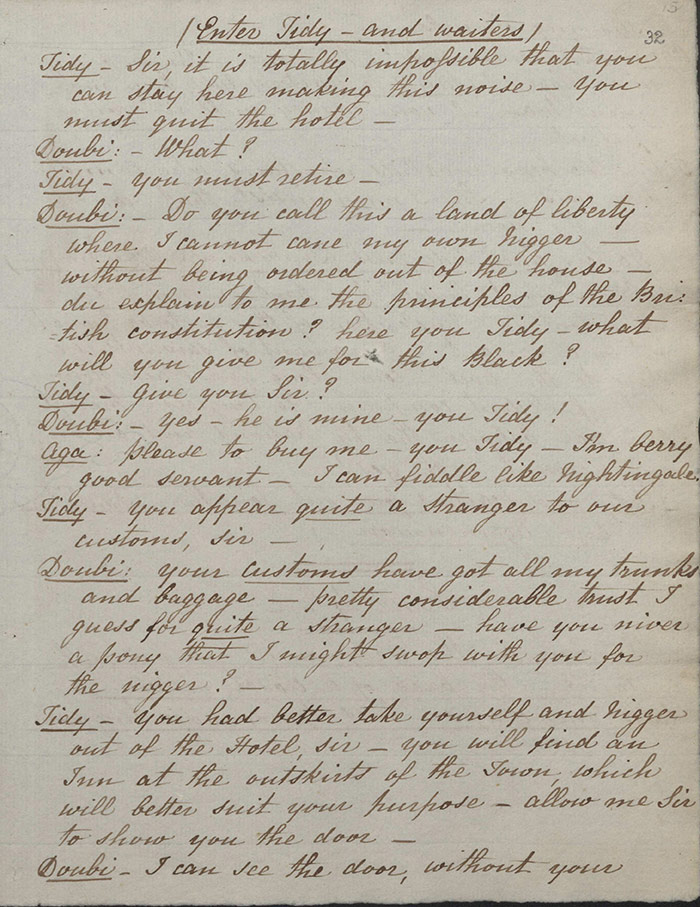

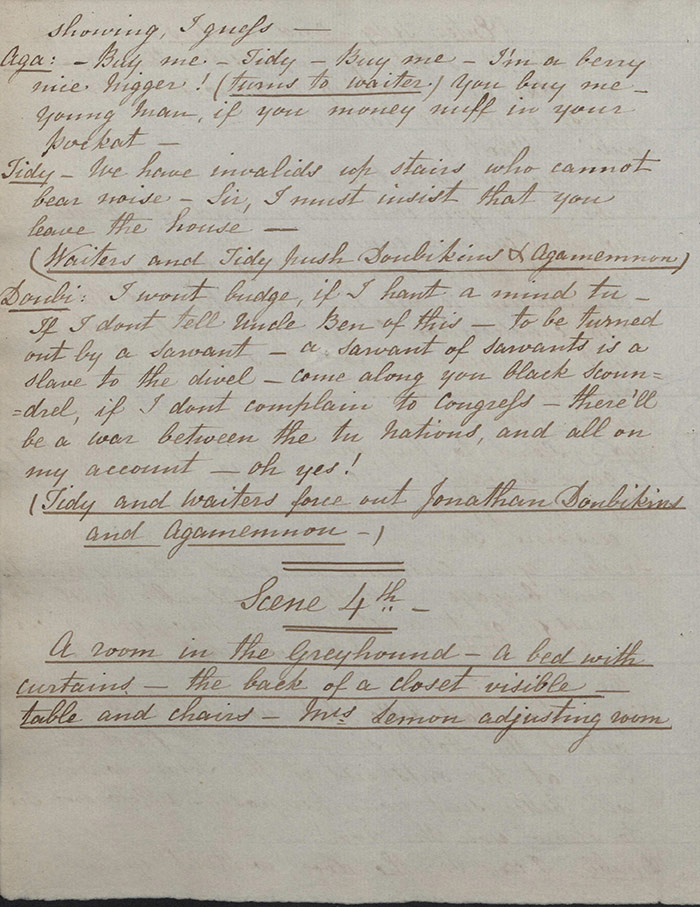

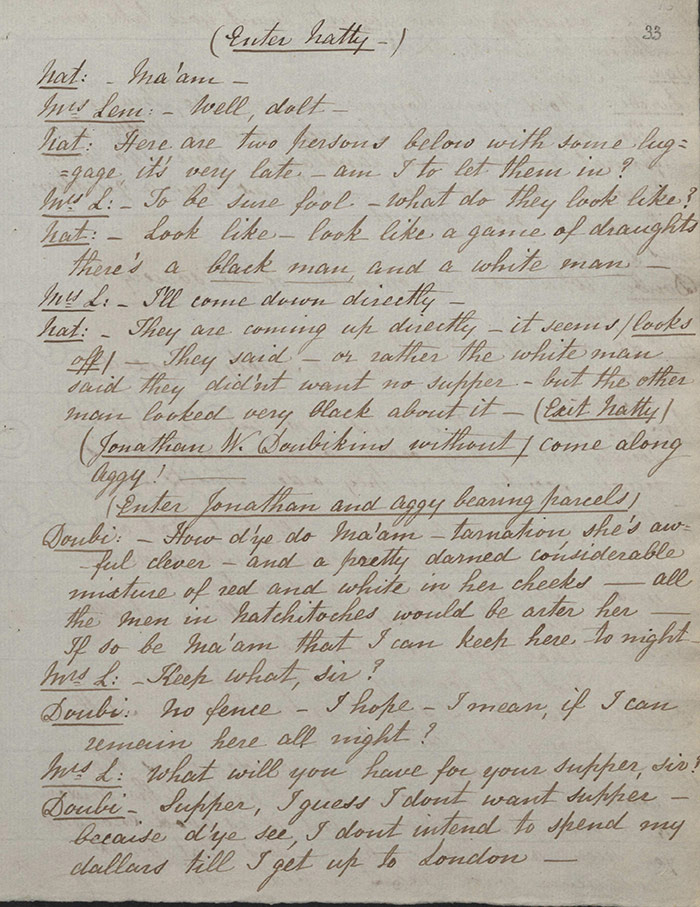

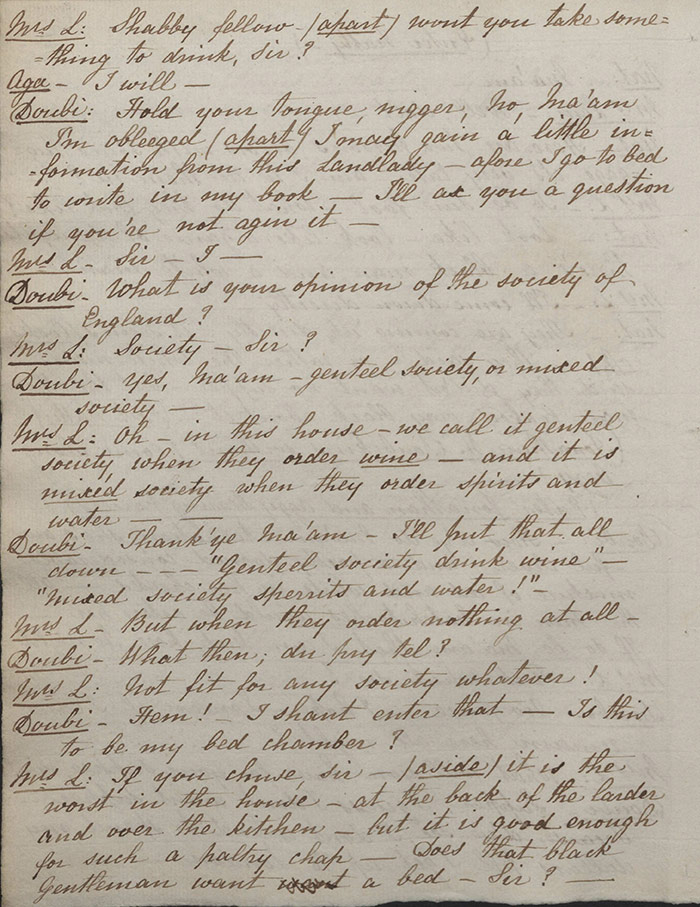

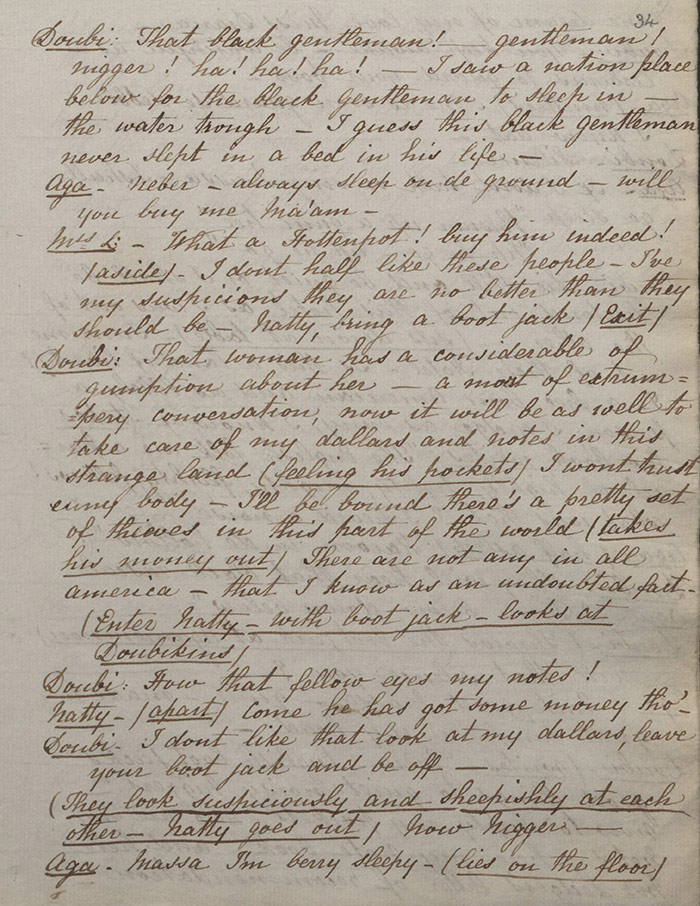

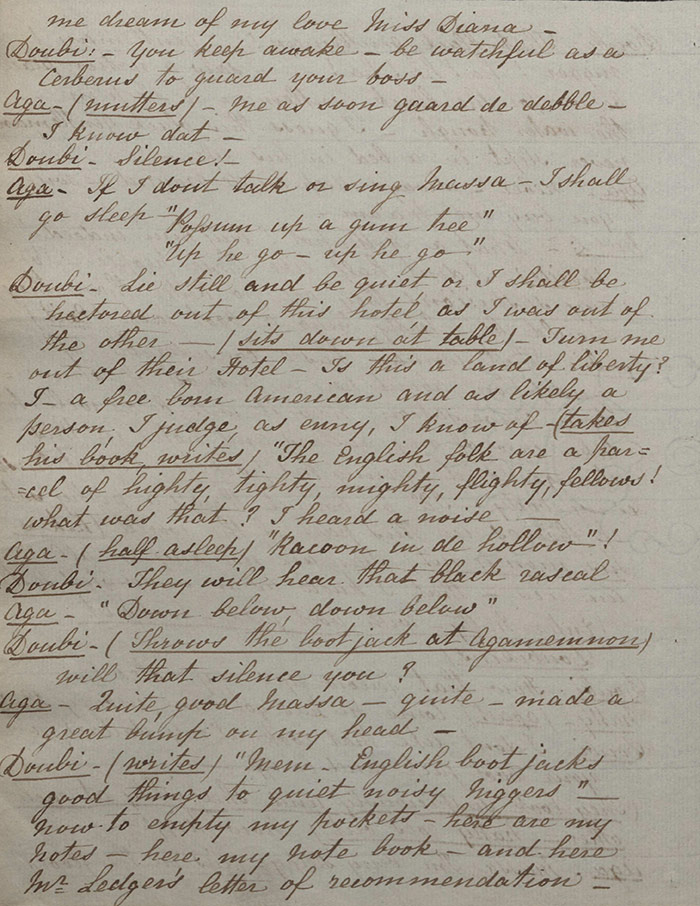

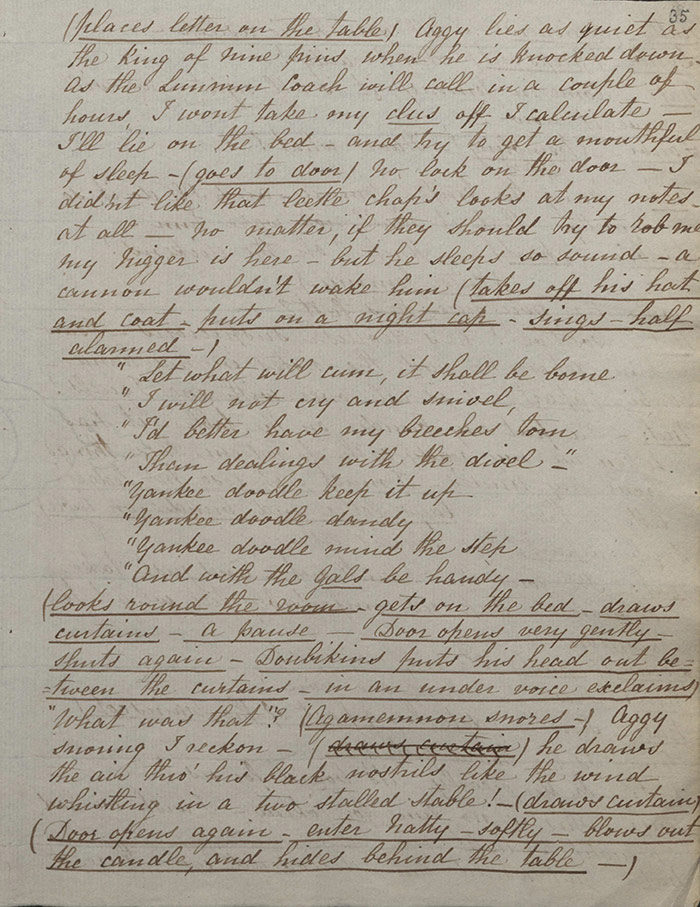

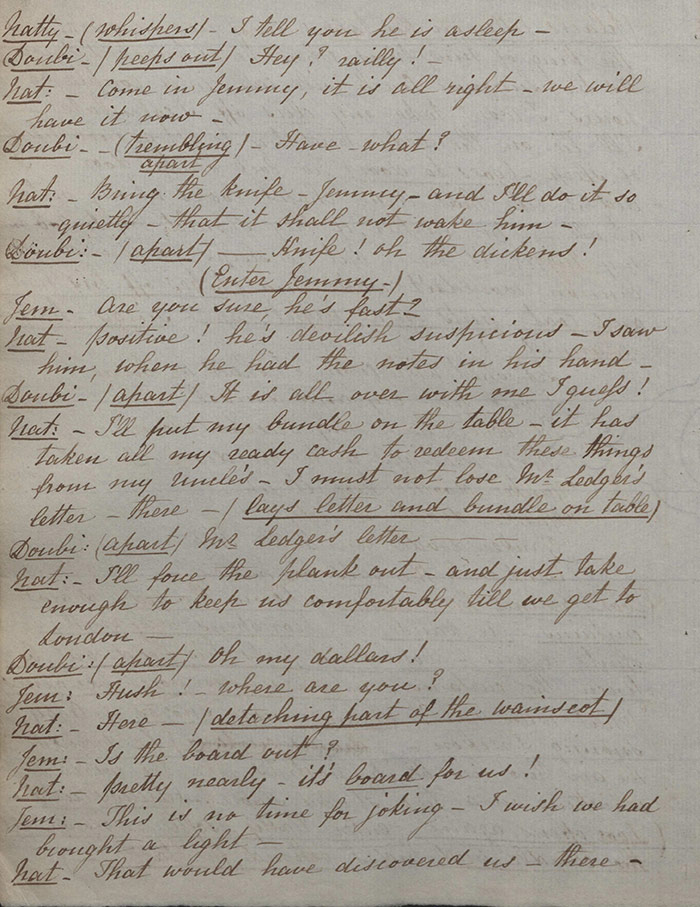

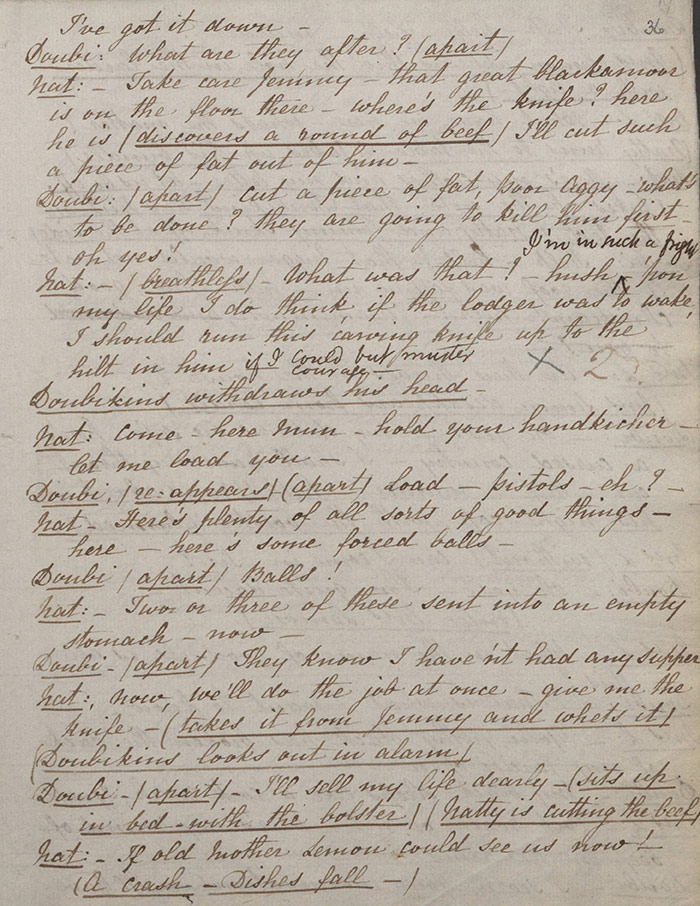

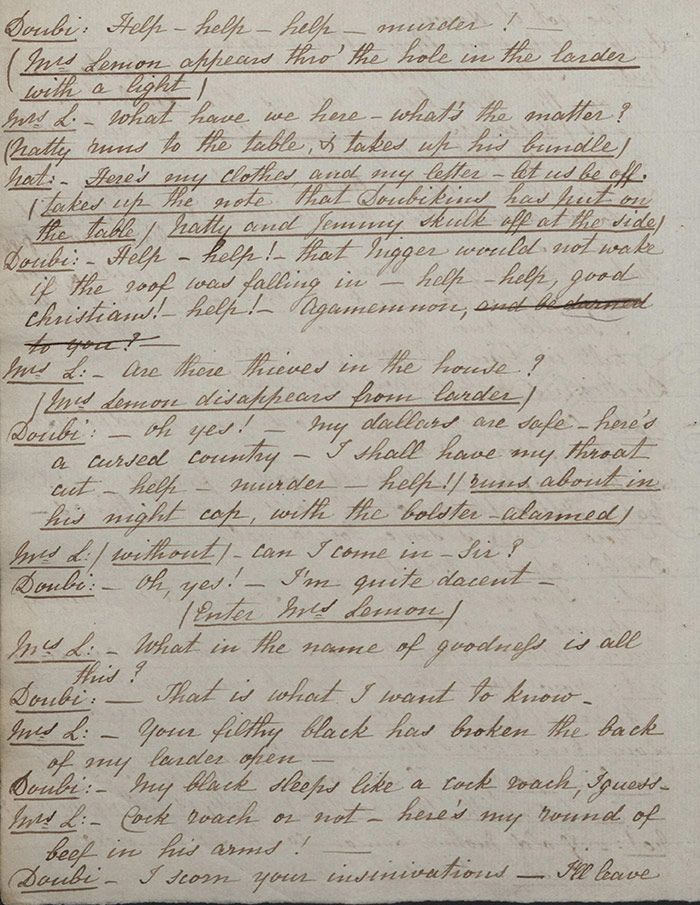

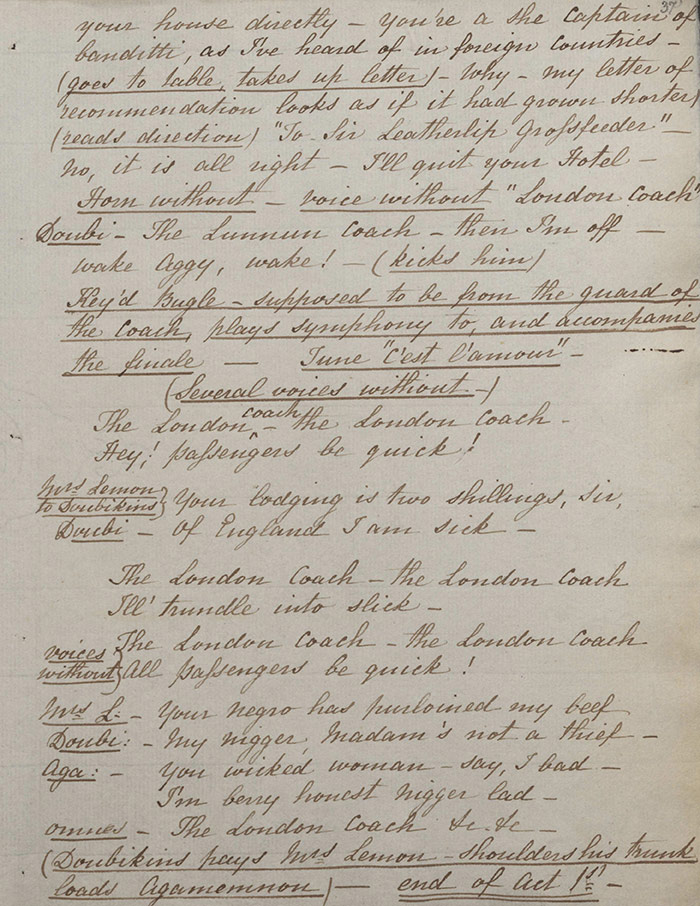

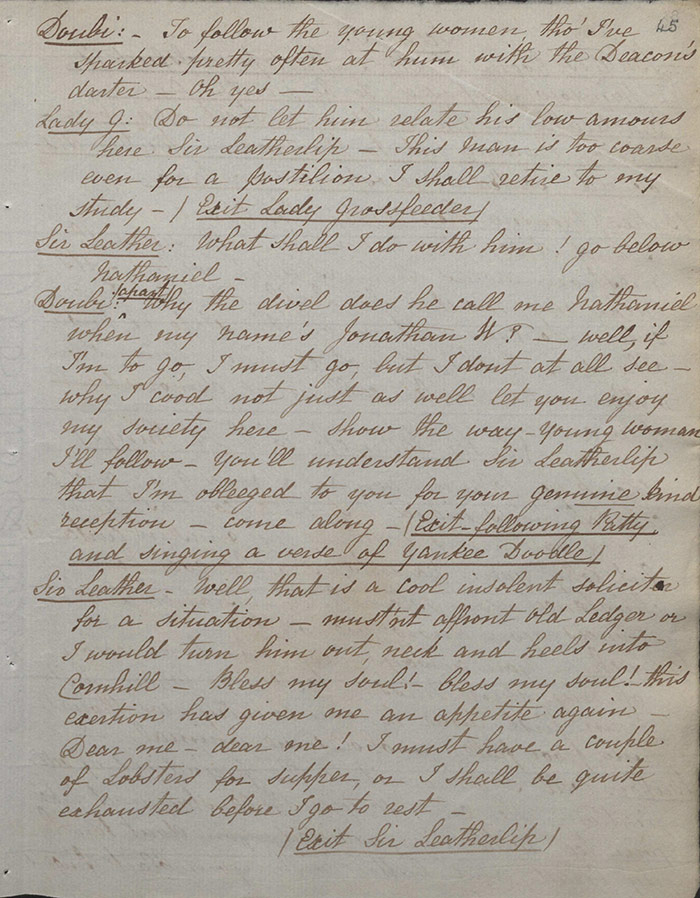

Mr Ledger returns to the Waterloo hotel and finally identifies Jonathan as the man he was looking for (f.27v). He writes him a letter of introduction for Sir Leatherlip Grossfeeder while Doubikins sings a version of Yankee Doodle. Agamemnon arrives ‘in a Sailor’s Jacket with a Turtle on his Head’ (f.31v) and Jonathan vents his frustration at his supposed laggardness. A comic exchange follows when Ledger encourages him to take the turtle to London to be eaten by Sir Leatherlip and Jonathan thinks he is pointing to Agamemnon and trying to trick him. The two descend into argument as Jonathan’s patriotic ire is raised; when he then physically chastises Agamemnon to tears, Tidy enters and asks him to desist. Jonathan retorts ‘Do you call this a land of liberty where I cannot cane my own N___ – without being ordered out of the house’ (f.32r). Tidy eventually bundles him out of the hotel. Scene 4 finds Jonathan and Agamemnon arrive at the Greyhound where Natty introduces them to Mrs Lemon (f.32v). She is underwhelmed by the brash American and gives him the worst room in the house – the one that is to be targeted by Natty and Jemmy that night. Later that night, Natty sneaks into the room but he disturbs Jonathan who causes an uproar. In the confusion, Natty escapes with some beef, Jonathan leaves the hotel as well, and the letters of introduction get mixed up.

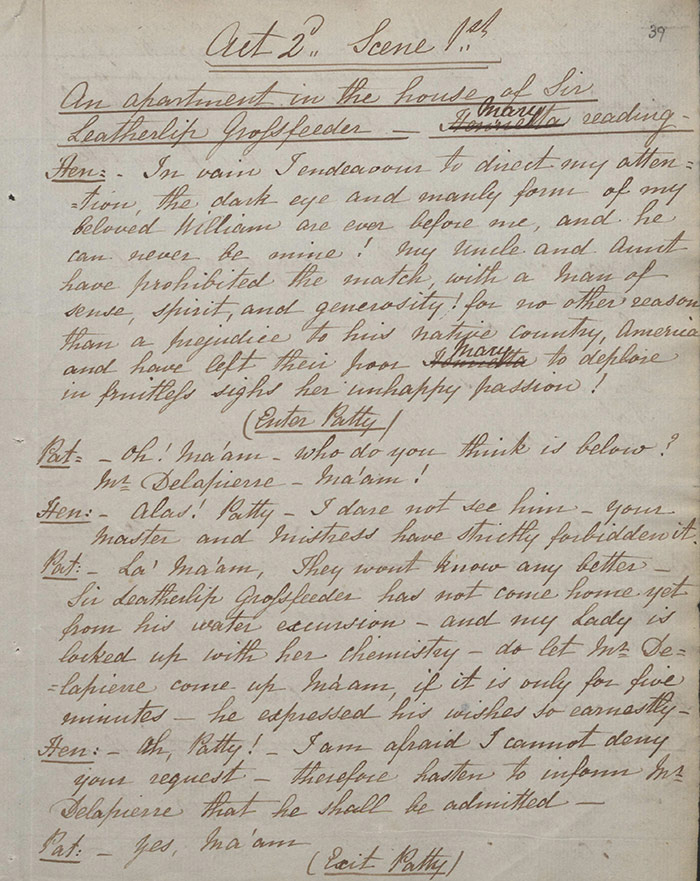

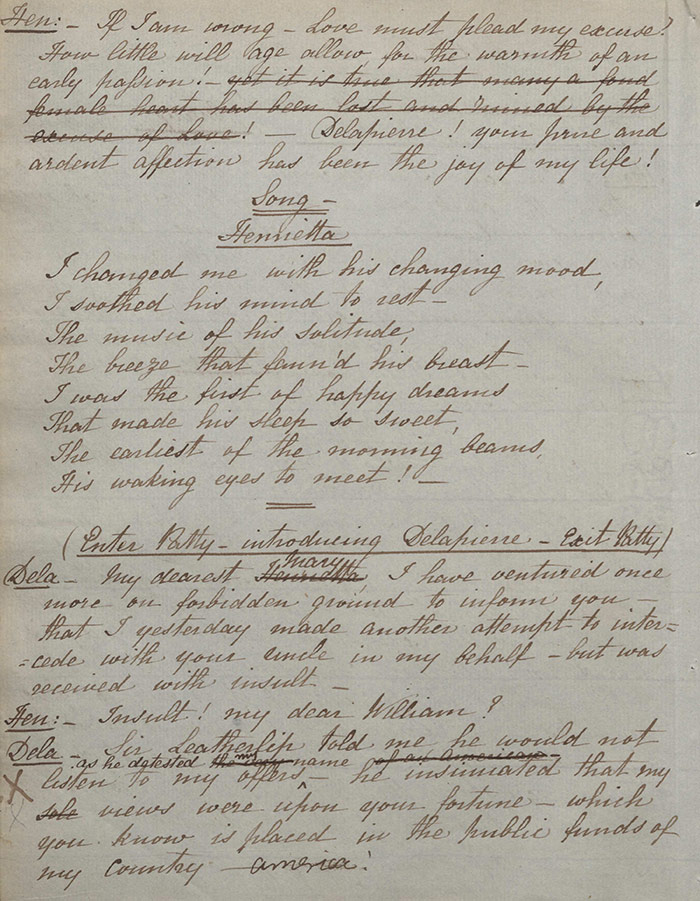

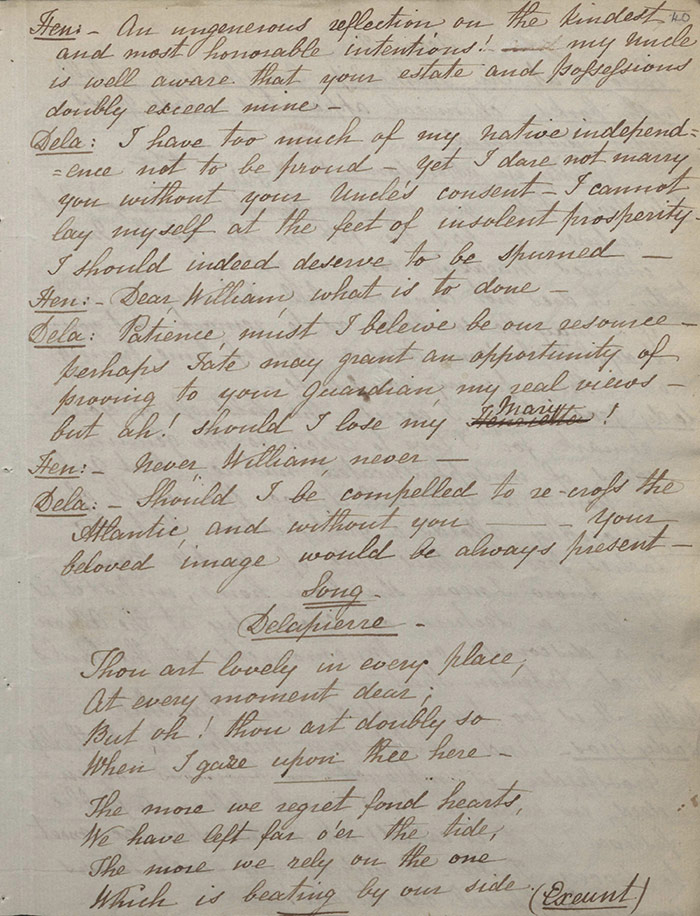

The second act begins at Sir Leatherlip Grossfeeder’s house where his daughter Mary is called upon by William Delapierre, her lover but disdained by her parents as he is American (f.39r). Sadly, he reports that he was rebuffed once again by Sir Leatherlip who believes him – erroneously – to be a fortune-hunter.

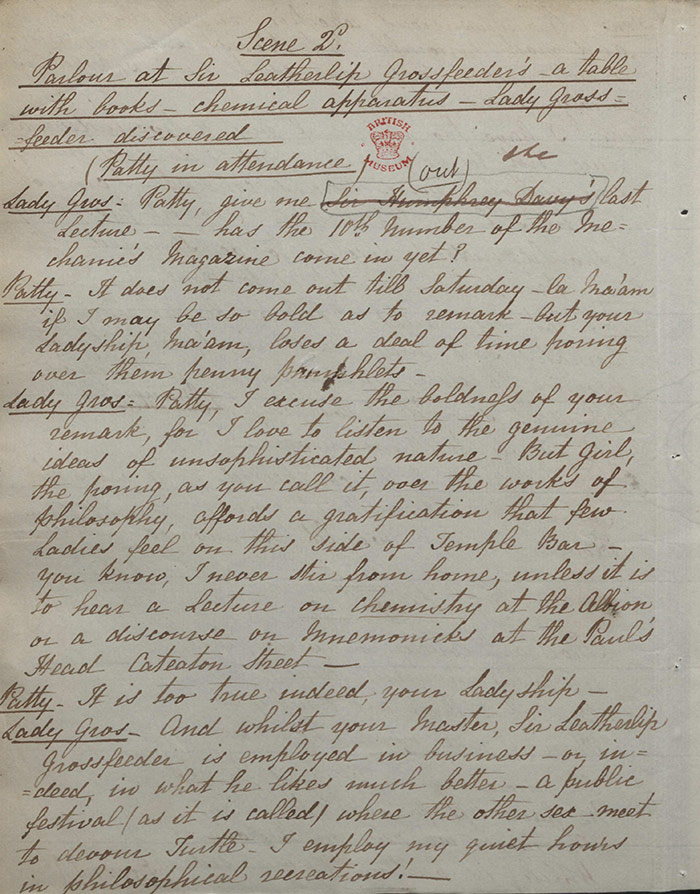

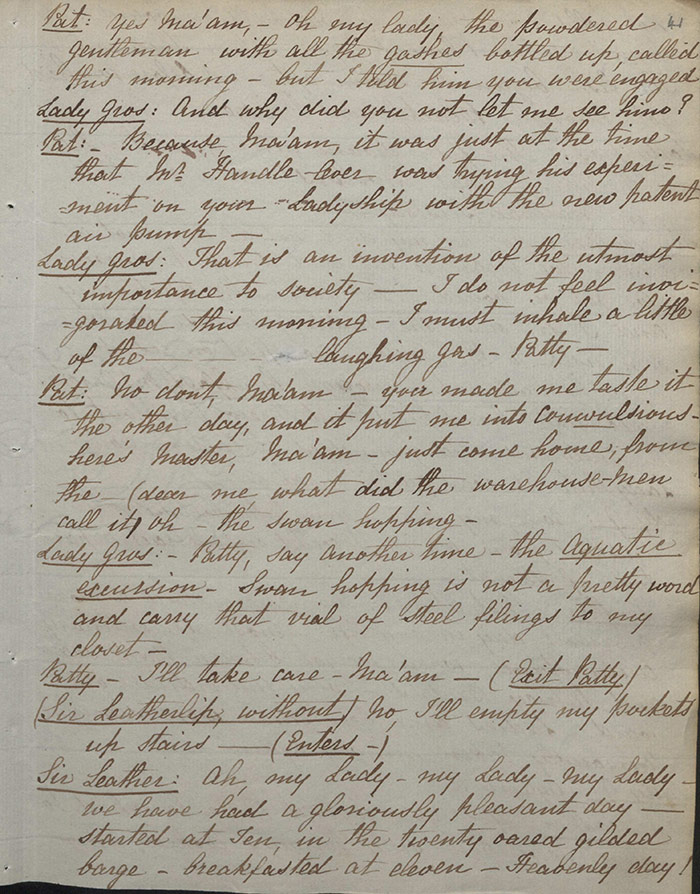

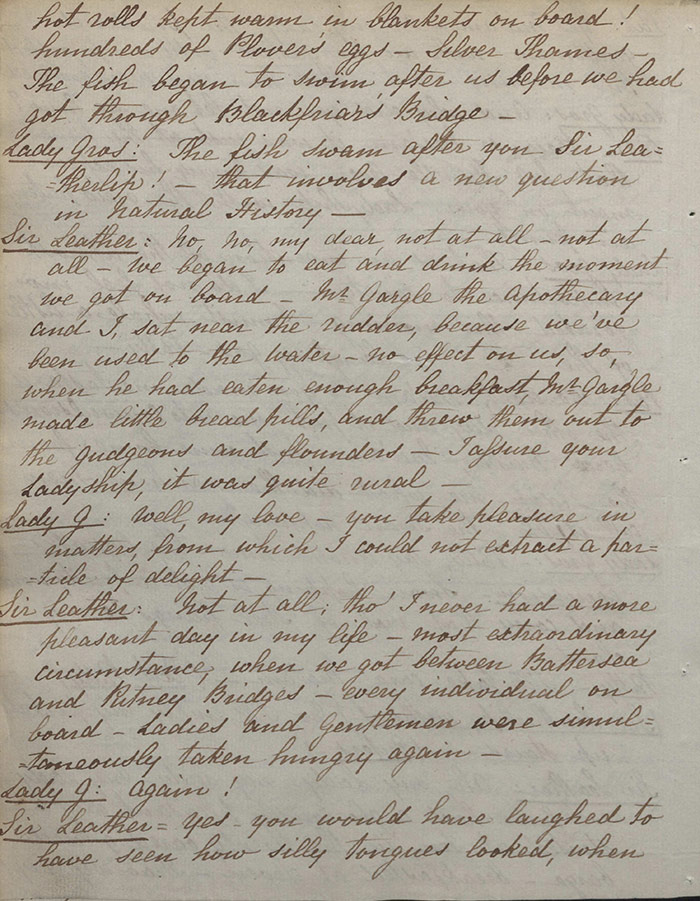

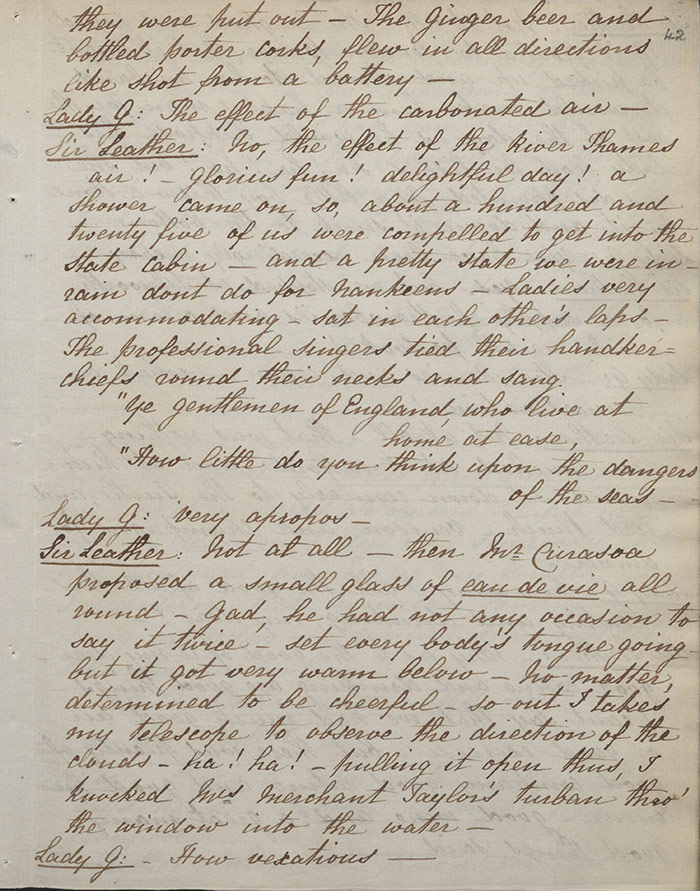

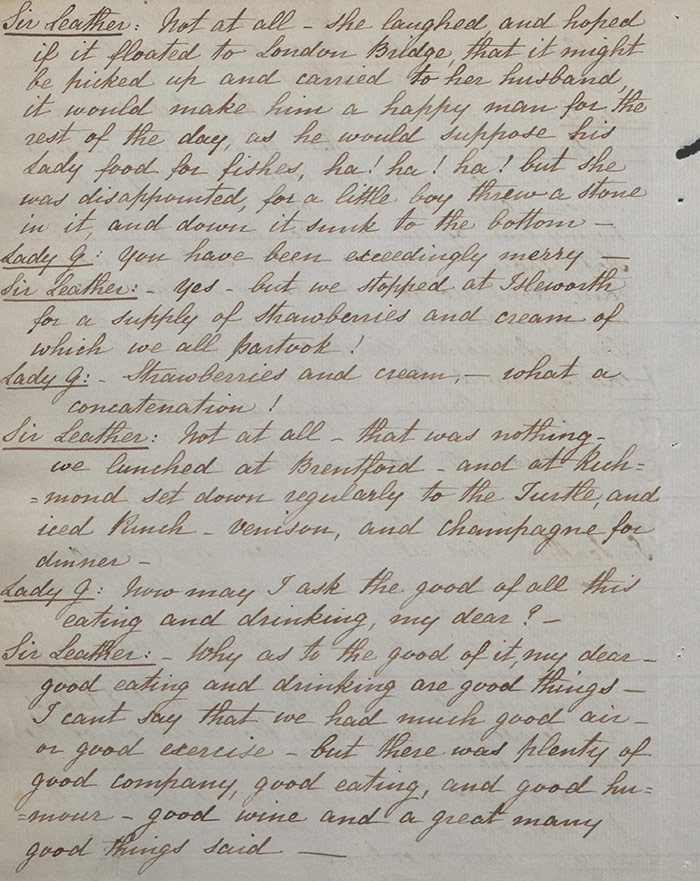

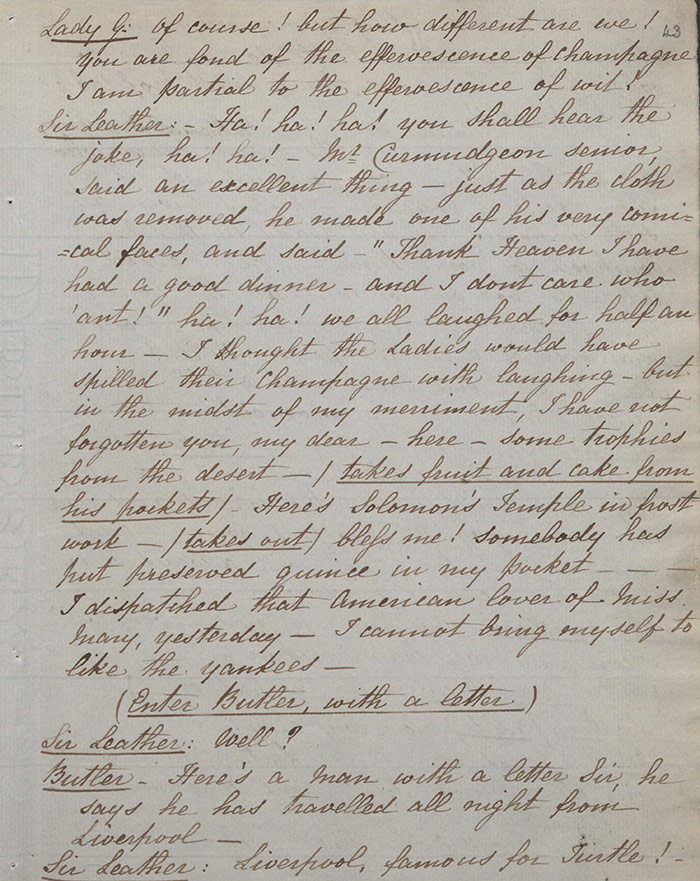

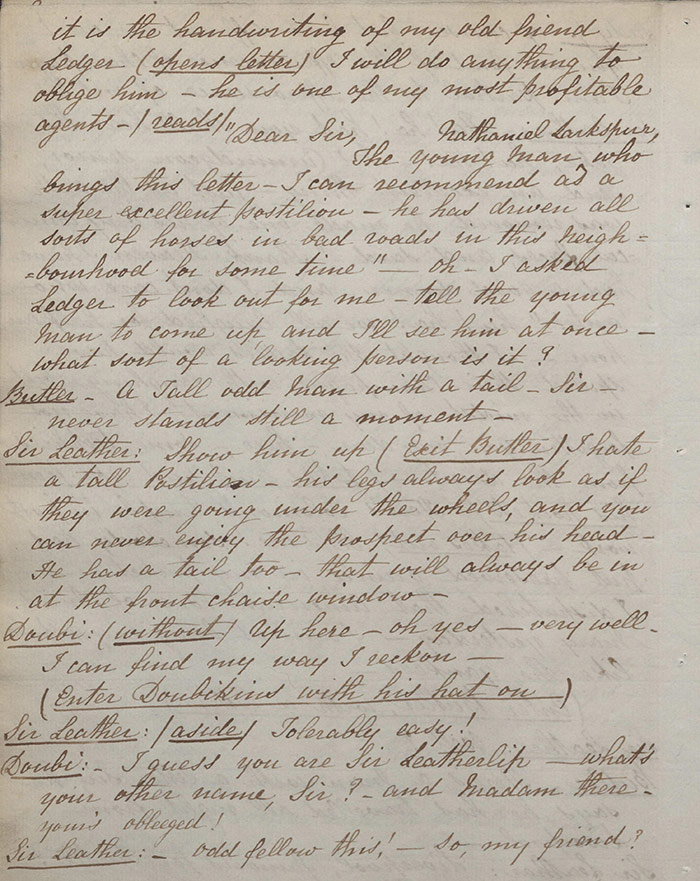

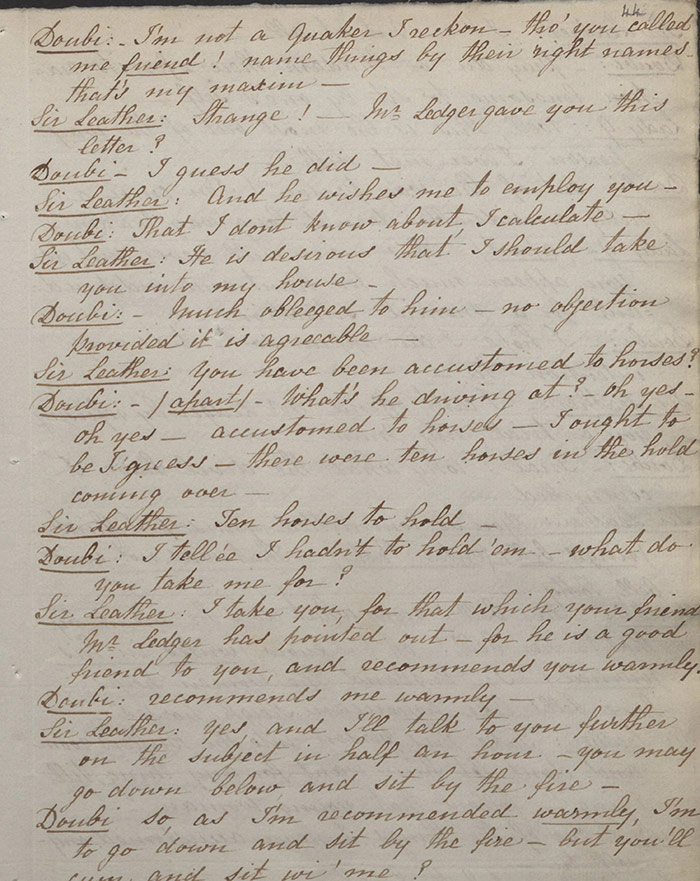

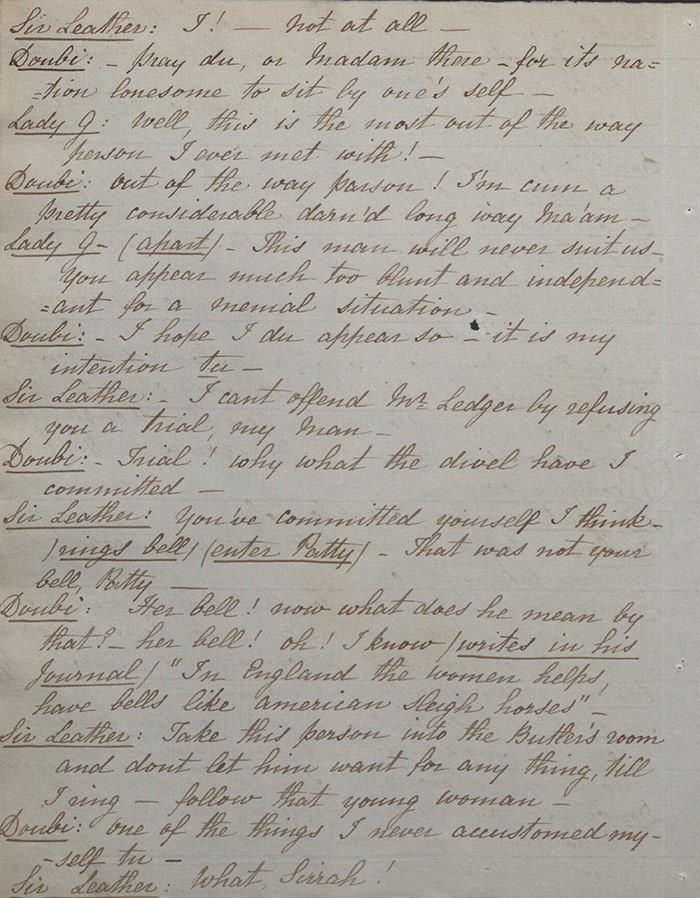

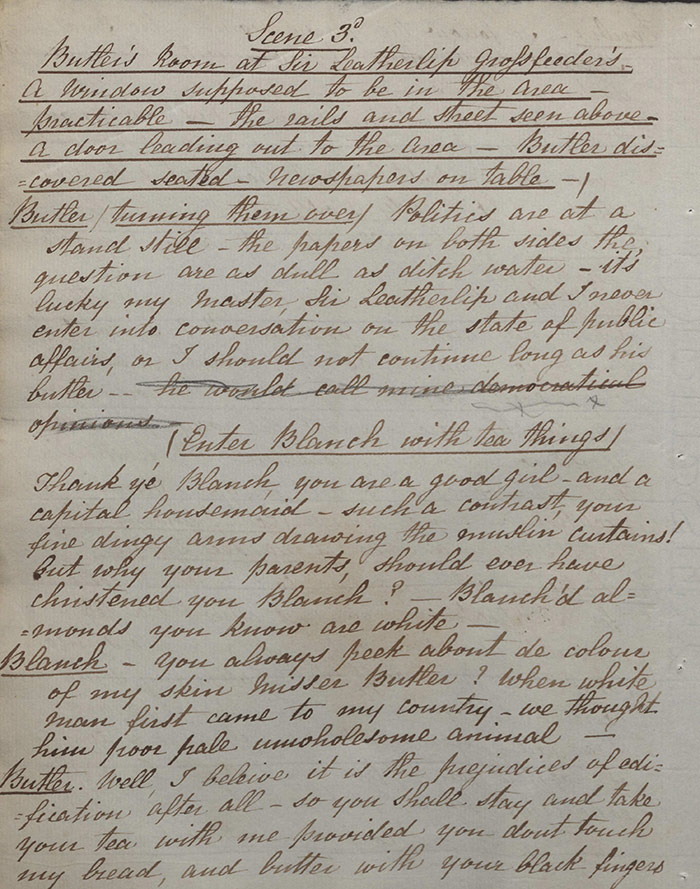

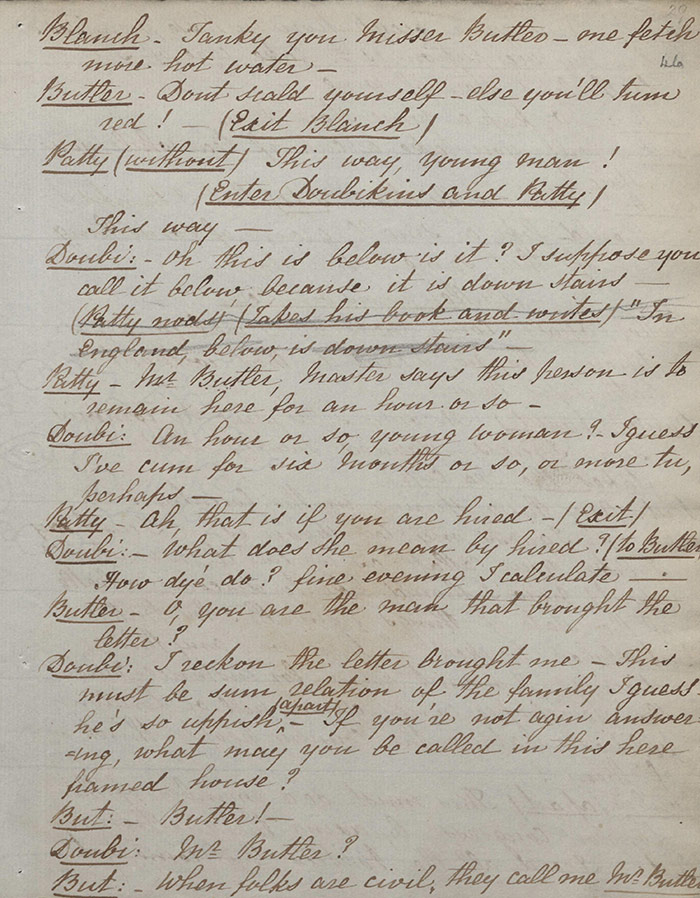

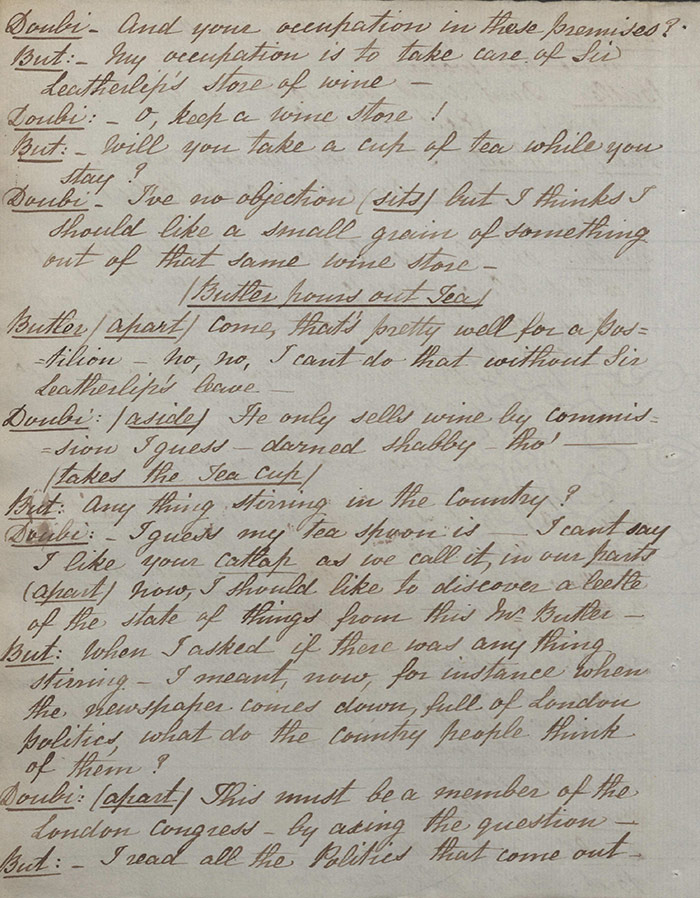

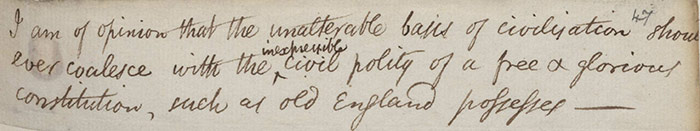

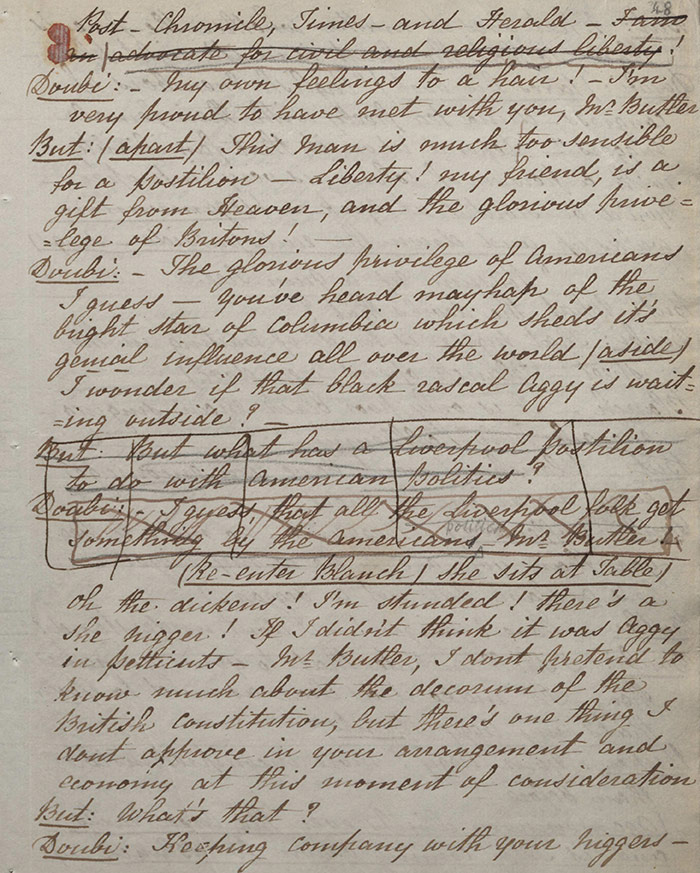

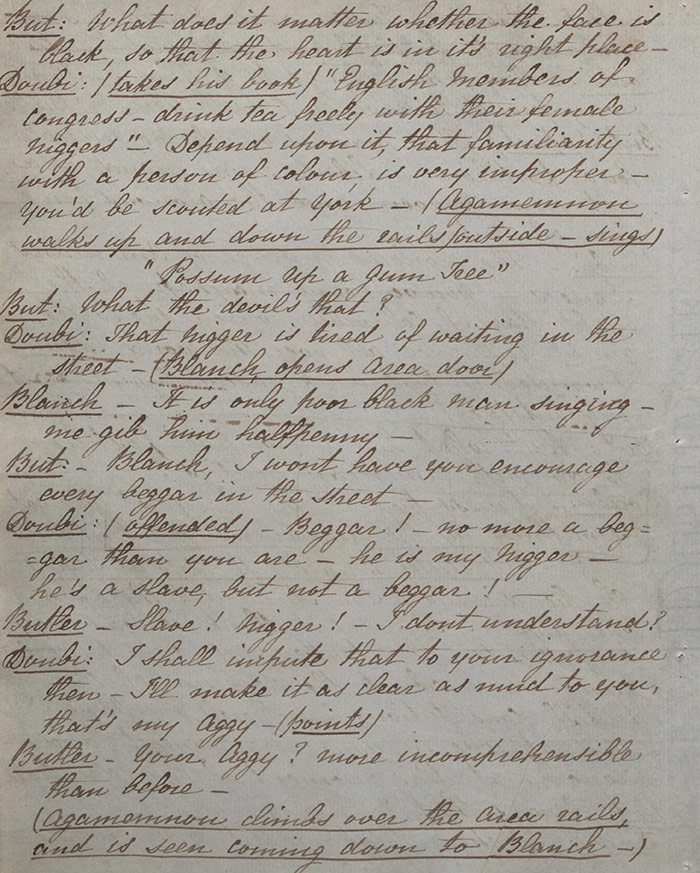

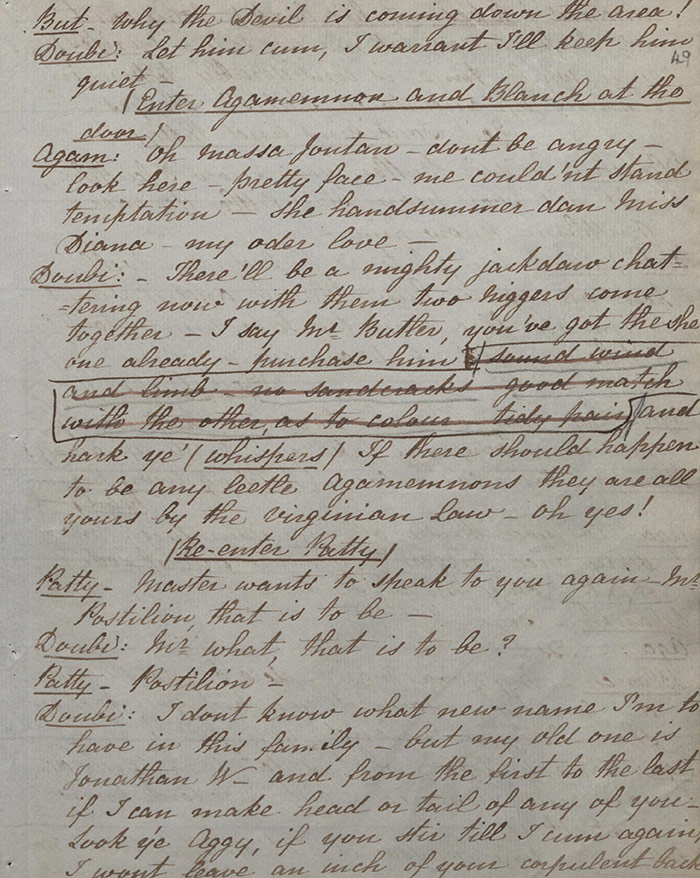

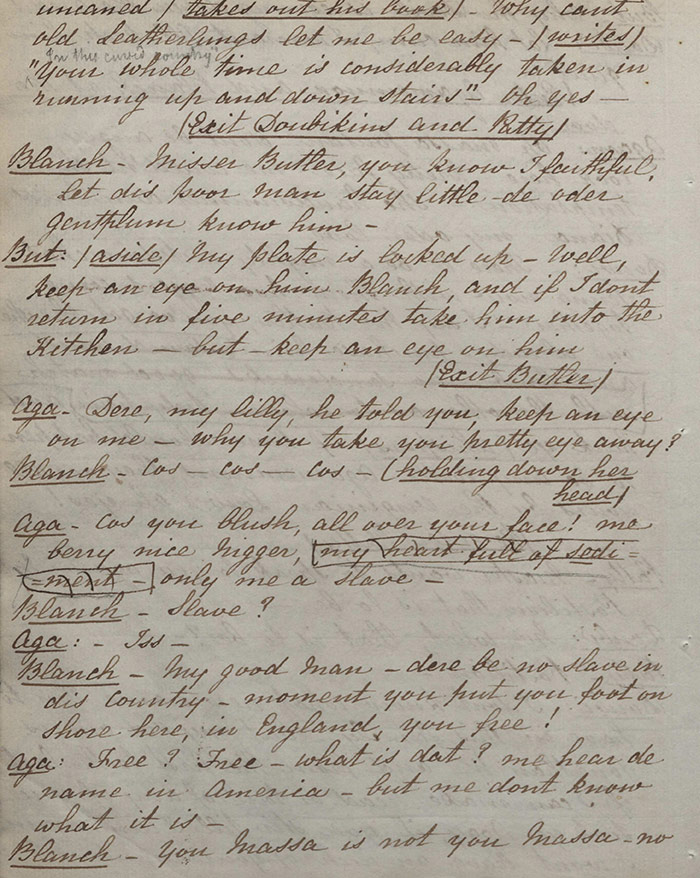

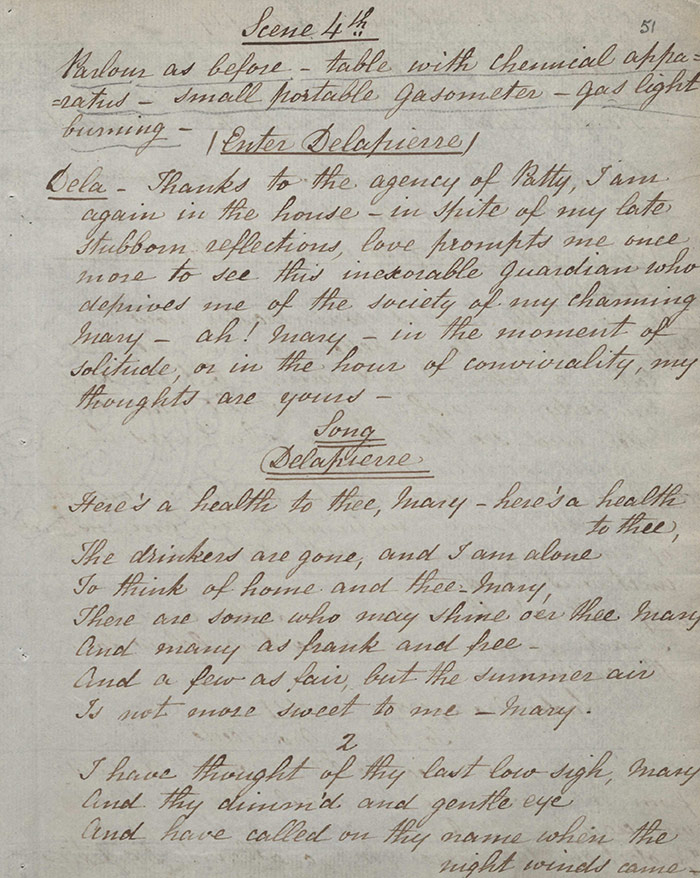

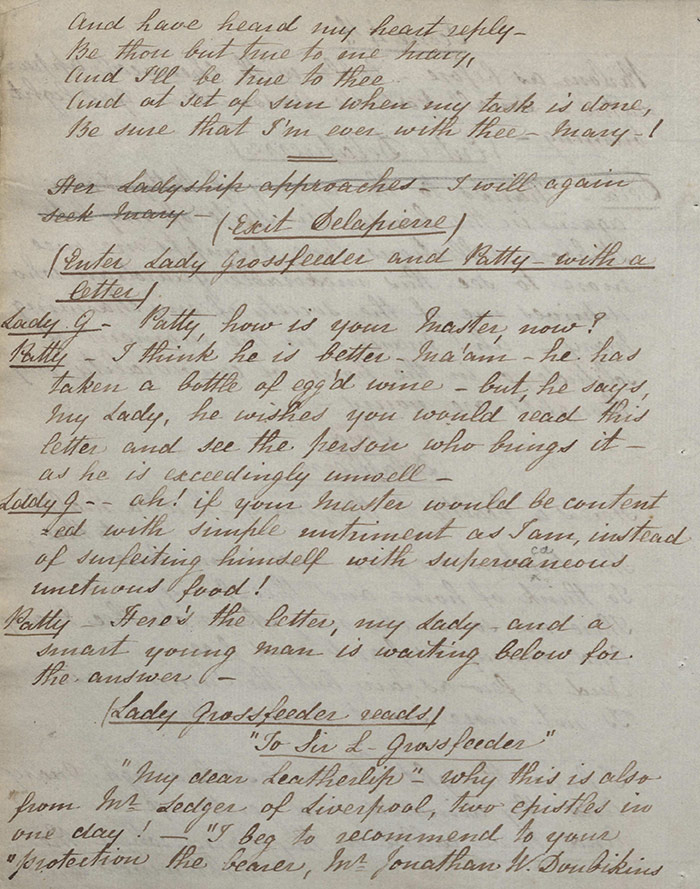

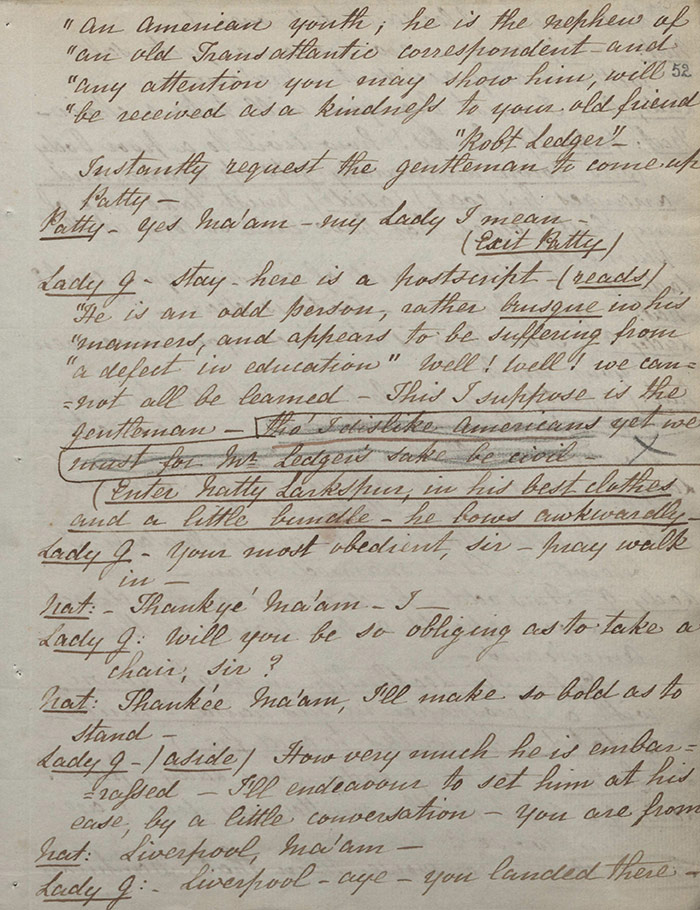

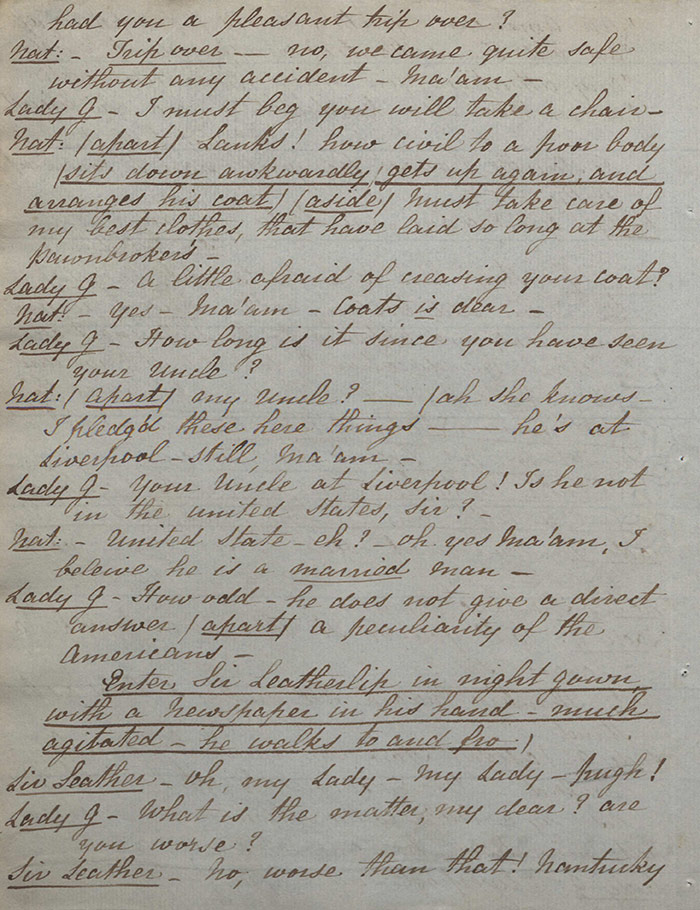

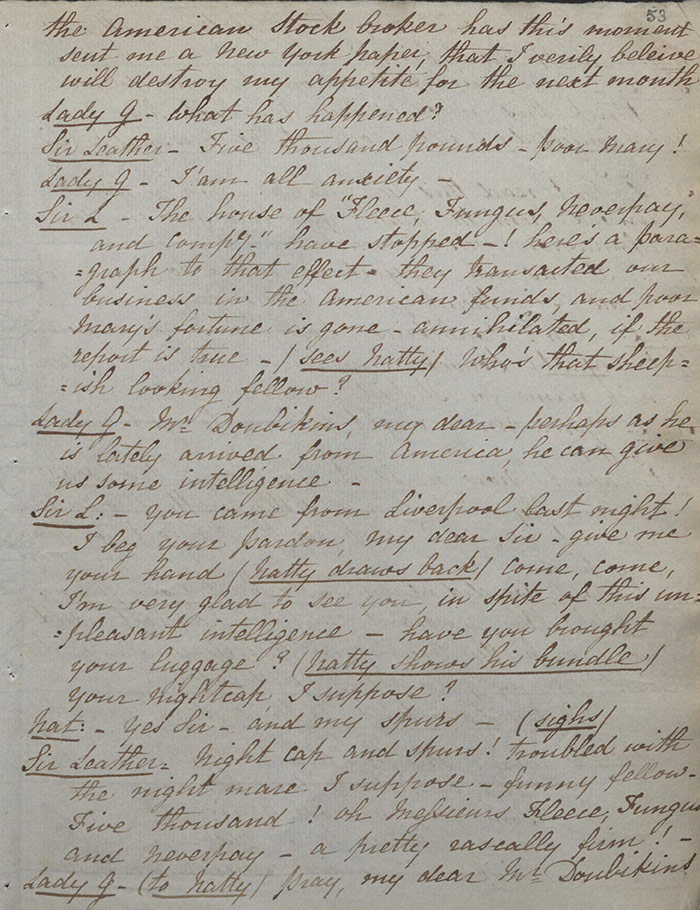

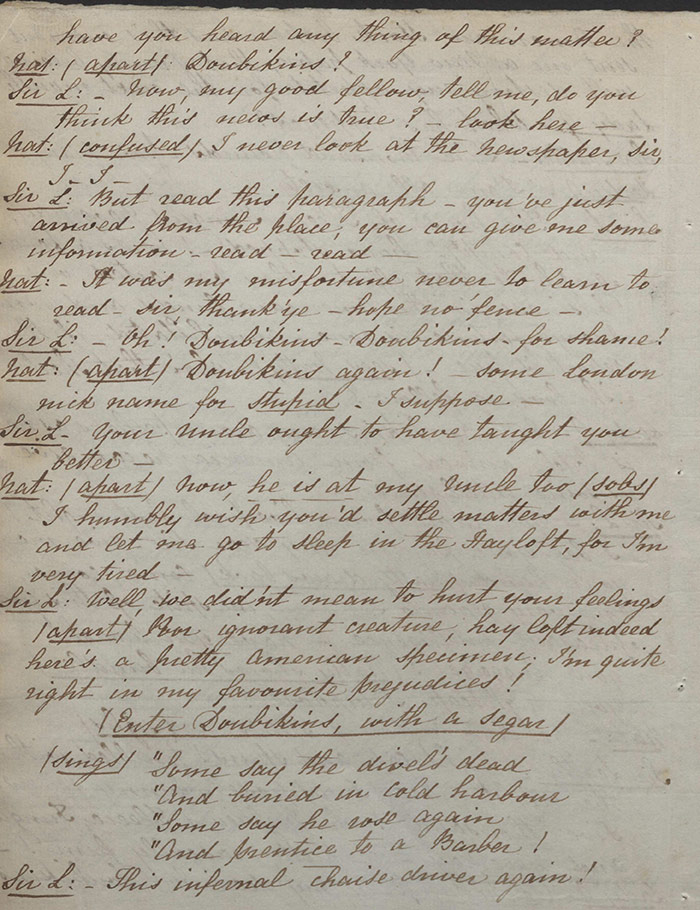

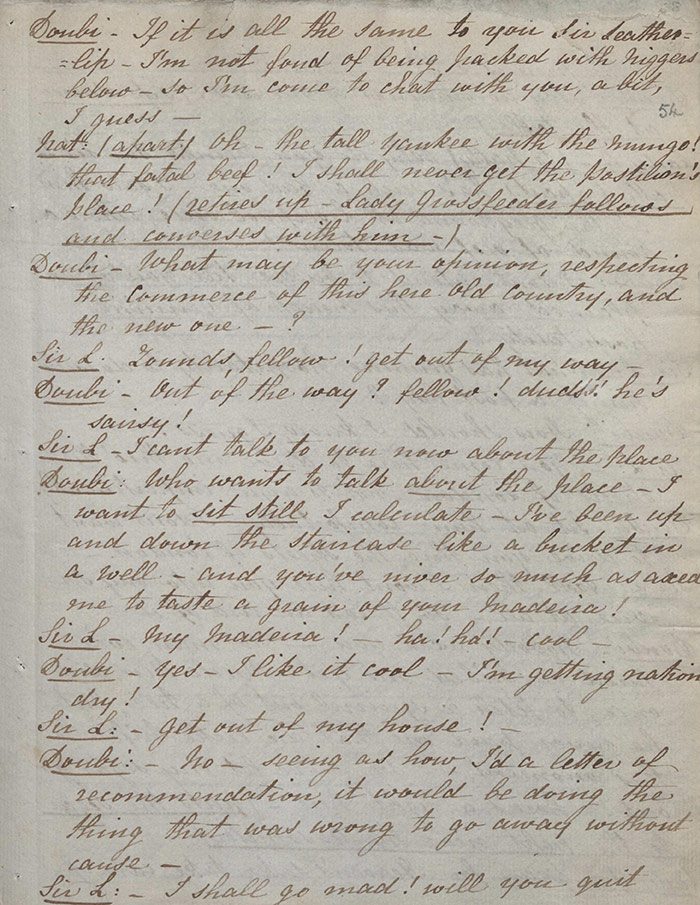

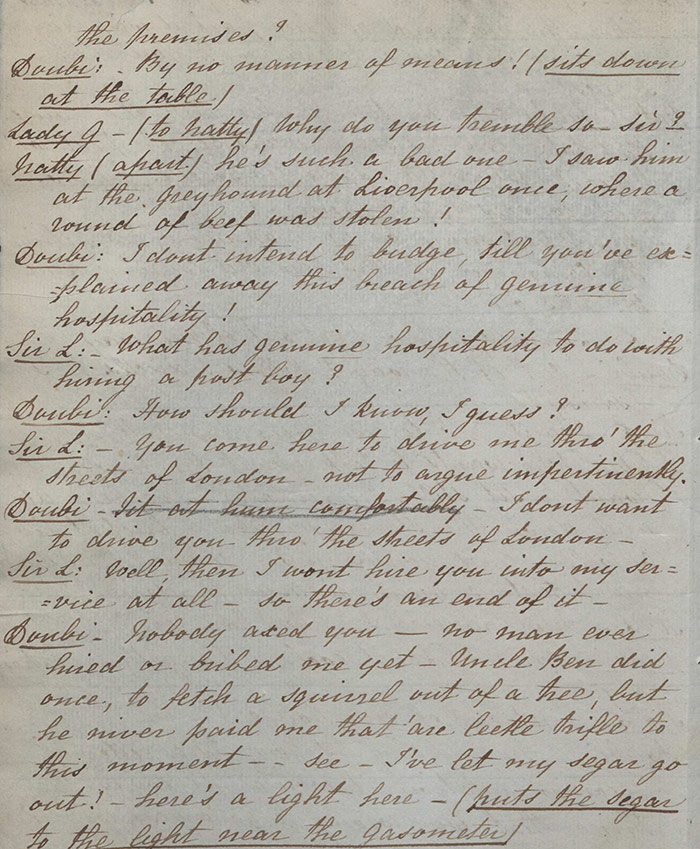

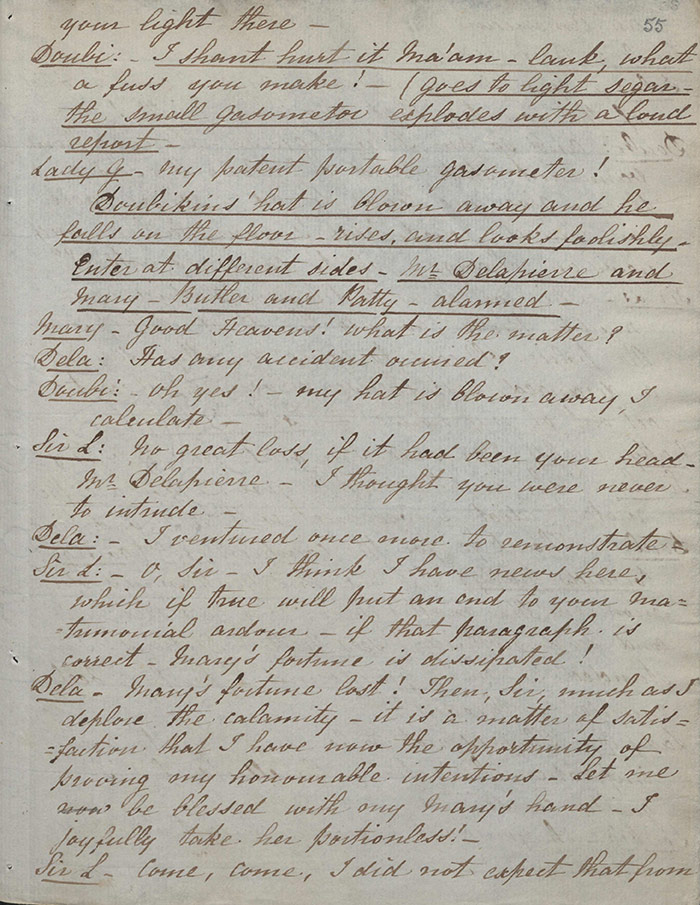

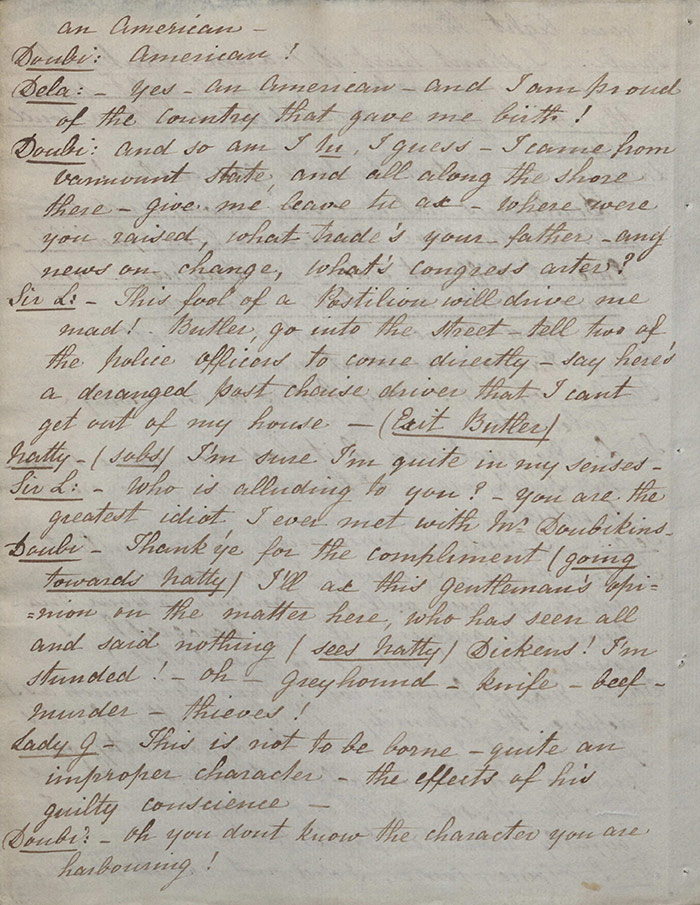

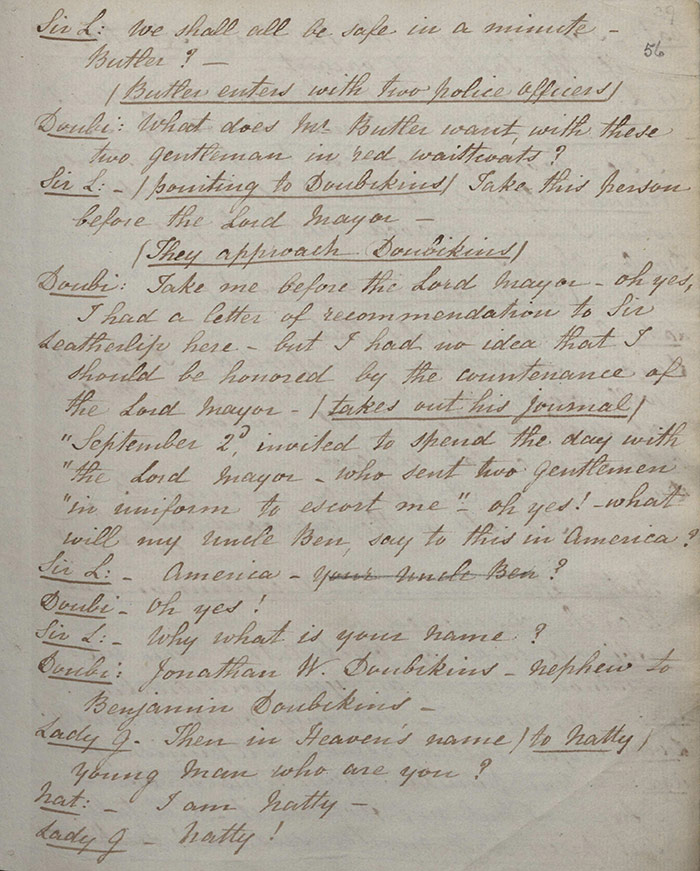

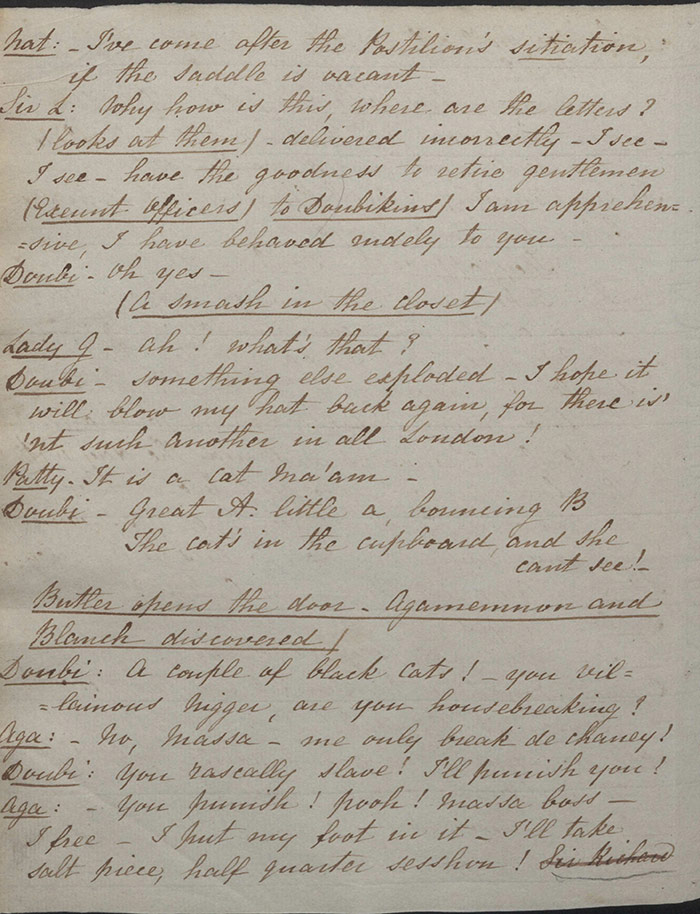

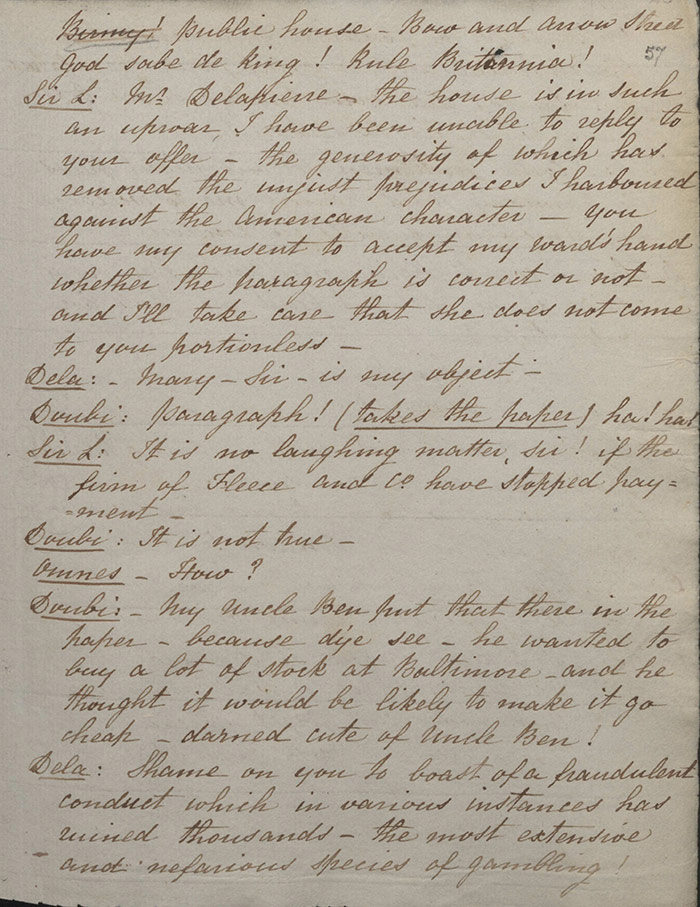

The second scene finds Lady Grossfeeder engrossed in her chemistry studies when Sir Leatherlip interrupts her with an account of his hedonistic trip on a Thames barge where he ate and drank his fill (f.40v). She comments on their differences: ‘you are fond of the effervescence of champagne I am partial to the effervescence of wit!’ [f. 43r] before the Butler announces the arrival of Natty (in fact, Jonathan). As Sir Leatherlip believes him to be there for the postilion position, the scene is understandably confused with Lady Grossfeeder shocked at Jonathan’s forward manner. But as Ledger has vouched for him, Sir Leatherlip feels obliged to give him a trial and send him downstairs. The Butler is downstairs reading newspapers when Blanch enters and he comments on her black skin colour (f.45v). Jonathan arrives and he and the Butler have a brief discussion of politics which leads Jonathan to believe the Butler is an MP. When Blanch sits down with them he is appalled. Agamemnon enters and is attracted to Blanch to the point that Jonathan tries to sell him to the Butler before he is summoned by Sir Leatherlip. Blanch and Agamemnon are left alone and she tells him that as there is no slavery in Britain, he is free. They retire together for romantic purposes. Delapierre is in Lady Grossfeeder’s chambers attempting to see Mary (f.51r). He exits when she approaches with her servant, Patty. Jonathan Doubikins (in fact, Natty) has now arrived and she interviews him at Sir Leatherlip’s request as he is ill from overindulgence. Their exchange is awkward and stilted thanks to the misunderstanding when Sir Leatherlip enters with disastrous news that Mary’s fortune, invested in American stock, has been wiped out. Jonathan enters and his dialogue with Leatherlip becomes heated: Jonathan is affronted at the other’s lack of hospitality while Leatherlip is appalled at his cocksure manner so at odds at what he expects from a postilion. Finally, Jonathan lights a cigar from Lady Grossfeeder’s gasometer which explodes. Delapierre, Mary, Butler, and Patty come running. Sir Leatherlip tells Delapierre of the change in Mary’s fortune which he rejoices in as it allows him to prove his love for her was true. Subsequently, everyone’s real identity is revealed before Agamemnon and Blanch clatter out of the closet. In a somewhat rushed ending, Agamemnon reproves his former owner before Jonathan chuckles at the paragraph which he says was inserted falsely by his uncle in order to benefit from stock speculation. He in turn is also lambasted by Delapierre for the ‘most nefarious species of gambling’ (f.57r) before Sir Leatherlip calls for harmony and welcomes both Americans to London.

Performance, publication and reception

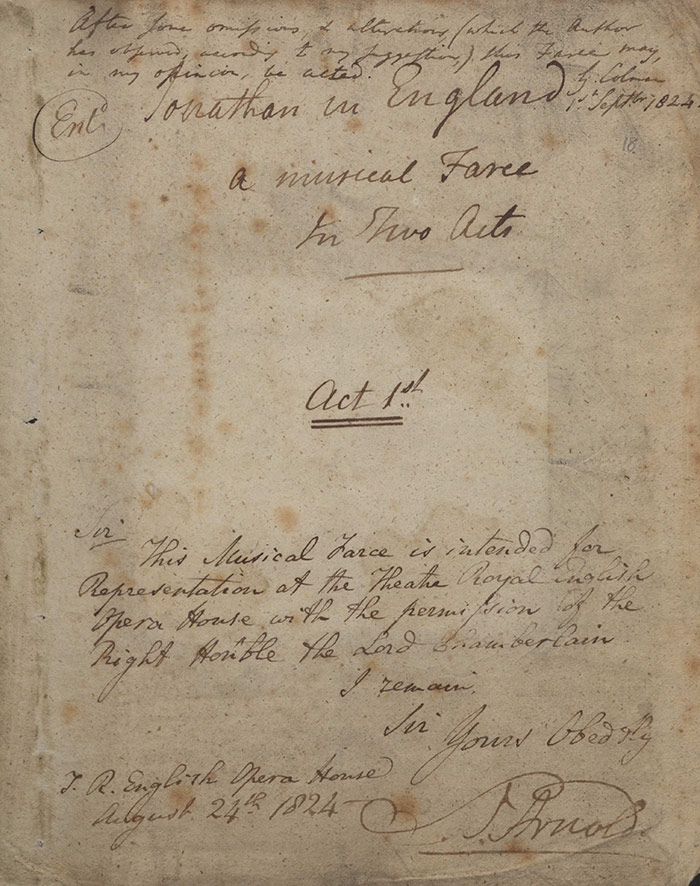

Based on George Colman’s Who Wants a Guinea? (1805), this ‘musical Farce in Two Acts’, as it is described on its title-page, was first submitted by Samuel Arnold on 24 August 1824. George Colman the Younger had been in the position of Examiner of Plays since January 1824. A note on the title page in Colman’s hand indicates that it was approved for performance after some changes had been implemented (see below) on 1 September 1824.

The comedy was first performed on 3 September 1823 at the English Opera House. The play was the second offshoot of Charles Mathews’s 1822-23 tour of America which had been very successful and established him as the leading comic actor of the day. However, while A Trip to America (1824) had pleased everyone, Jonathan in England, in which Mathew’s played Jonathan Doubikins, had a much more mixed reception.

The Times (4 September 1824) offers a succinct explanation of the problem:

A new farce, entitled Jonathan in England, was last night produced. It has been produced in Mr. Peake’s pun-manufactory, chiefly for the purpose of giving Mr. Mathews an opportunity, as Jonathan W. Doubikins, of raising a laugh at the strange phraseology of our trans-Atlantic brethren. So long as this object was fairly kept in view, the audience were unanimous in their approbation; but Mr. Peake thought proper, on more than one occasion, to make some of the characters introduce matter, which by implication reflected reproach on American ideas of independence. This side-wind censure of America, which doubtless was intended, by contrast, as a compliment to England, was received, as such illiberality always should be received, with a strong expression of disgust. It is time that the custom of satirizing every country but our own should be banished from the stage.

The Literary Gazette (11 September 1824) was also underwhelmed. Although the piece had been written expressly for Charles Mathews (Jonathan), who ‘laboured hard for its success’, Jonathan’s adventures were ‘far from satisfactory’. Over all, the comedy ‘will add nothing to Mr. Peake’s reputation’. The principal criticisms relate to over familiarity with the comic tropes and a lack of action. See also The Drama (September 1824) and the Literary Gazette (7 September 1824) for other negative assessments.

On the other hand, The Theatrical Observer (4 September 1824) found that it had ‘decided success’ despite the presence of some who ‘evidently came prepared to oppose it’. The Literary Chronicle (11 September 1824) believed that Mathews ‘kept the house in continued good order’ while the London Magazine enthused that the piece was ‘as unvarnished a caricature of the impudence, stubbornness, and freedom, of a Yankee, as a lover of the ridiculous would desire to see’.

However, the most forceful critique of the play came in a substantive essay which appeared in the European Magazine (December 1825) titled ‘Sketches of American Character’. Written ‘By an American’, it is an acerbic general attack on English ignorance of the variety of American character types and then the author homes in on the main actor:

It is high time to take Mr. M. to task. His portraiture of the Yankee, is generally misunderstood here: and he knows it. He knows very well, that a wretched caricature, which he got up, in a frolic, is received, in a pernicious way, by the multitude here; and yet, he persists in multiplying the copies. He knows, in his own heart, I say this without qualification, he knows, and has known it, for a whole year, that his Jonathan is a very poor, and very feeble counterfeit, unworthy of America, unworthy of Mr. M., as an actor, and altogether unworthy of his country. (378)

The writer then goes on to pick holes in the various mannerisms, pronunciations, and items of clothing that Mathews wears in the American character, arguing that these are not in the least truly American. By correcting these errors, the writer hopes to ameliorate relations between the two countries.

The following issue (January 1825) incorporated a lengthy rebuttal from Mathews. He disputes the accuracy of the criticism and defends his good intentions. Nor, does he believe, should he be held accountable for characters written by others. And if Americans can laugh at Stage Irishmen and Scotchmen, shouldn’t they be able to laugh at themselves? Moreover, he recounts a number of occasions where he has been present at social occasions that strengthened the relations between the two countries and has regularly praised the country.

A substantial response to this from the original writer was published in the February issue. The first two parts of this exchange were published in his Memoirs (518-549).

The play does not appear to have been published.

Commentary

There is no doubt that this play is an uncomfortable perusal for the modern reader given its plentiful use of a deeply unpleasant racial slur. The discomfort is exacerbated by the fact that much more innocuous phrases and references (to our eyes) are deemed inappropriate while this remains untouched. Nonetheless, there is something mildly consoling that the term is used in order to bolster Britain’s liberal and humanitarian credentials: Jonathan’s callous and boorish treatment of his slave Agamemnon is contrasted to British befuddlement at what other characters perceive to be uncivilized values and behaviours. The play was written shortly after the establishment of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823 in London, whose members included Henry Brougham and William Wilberforce, and this is certainly an important context for this play.

Another important context is the state of British-American relations in the mid-1820s when the question of recognizing Latin American states which had rebelled against Spain was a critical issue for Prime Minister Liverpool and his foreign secretary, George Canning. Canning recognized the independence of Buenos Aires in August 1824 (and Mexico and Colombia in early 1825) which put the Liverpool administration tacitly in line with the Monroe Doctrine, an 1823 foreign policy statement which warned against European interference in Latin and Central America.

The manuscript shows a number of emendations and excisions marked in pen and in pencil. Both authorial/managerial and Examiner edits are in evidence. There are three different types of excisions in this manuscript which bear consideration: those marked in red pen, those in black pen, and those in pencil.

The excisions in red pen are more than likely made by Colman. Notorious for his puritanical intolerance of any scriptural reference on the stage – to the bafflement of many of his contemporaries – the first deletion in red is Jem’s comment that he looks ‘like Death on a pale horse!’ (f.24v), typical of Colman. Some leaves later, we note another deletion in red where simply the word ‘religious’ is scored out of Jonathan’s line ‘But I’ve sum religious doubts – about selling Aggy to be devoured’ (f.30v). It is clear that Colman’s objections go beyond biblical or eschatological references and that any reference to or sense of the spiritual was unwelcome.

We should note a puzzling deletion in red ink on (f.22v) when Jonathan’s line ‘Tarnation seize that Uncle Ben!’ has the word ‘seize’ excised in red. This peculiar excision may be explained by a tired Colman simply deleting the wrong word, given its precedent ‘tarnation’ is a euphemism for ‘damnation’, a word with which Colman had particular issues.

Colman also used his red pen for politically problematic passages as well, objecting to a version of the ‘Yankee Doodle’ song which offered a caustic view on London life (f.29r). On the manuscript we have a diagonal red line through the entire song with ‘(out)’ written in black ink beside it. There may well be particular localized references within this satire (as suggested, for instance, by the underlining of ‘inions’); however, it is more probable that the song’s overall tendency to denigrate London’s commercial, legal, and medical circles and its suggestion that ordinary people get ‘fleeced’ by such elites was enough for it to earn Colman’s disapproval.

The use of the black pen to write ‘out’ here by Colman suggests that he made at least two passes through the manuscript. One might speculate that the first pass was used to identify egregious offences such as those against religion or a song satirizing metropolitan elites while the second pen was a more considered affair, in order to ‘sweep up’ any remaining offending passages. Certainly, it would seem that the black pen was deployed second as the note on the title-page signing off on the text ‘After the omission & alterations (which the Author has offered, according to my suggestions) this Farce may in my opinion, be acted’ (f.18r) is in black. However, we have some difficulty here as there are also excisions and insertions that are clearly managerial and/or authorial (e.g. f.28r). We might, in this instance, speculate further and settle on Peake as the hand given Colman’s reference to the ‘Author’ just mentioned and the lengthy insertion on (ff.28v-29r) which smacks more of an authorial intervention and in a hand that is different from the manager, Samuel Arnold’s, which appears on the title-page.

If both Colman and Peake (and also possibly Arnold) used black pen to mark up the manuscript, this raises interesting questions about the origin of other major excisions in the manuscript. A significant deletion occurs on (ff.24v-25r) when a number of lines exchanged between Natty and Jem are deleted which refer to training a horse to kick and ‘lay up our stingy old master’ as well getting the key to the corn bin. References to food shortages, especially corn, were never likely to be approved by the Examiner, a difficult political issue for some years at this point, although it is possible that the manager/author may also have rethought these lines before submission. Anyone with a passing knowledge of the theatre and Colman would have known that he would never sanction a reference, even one somewhat oblique, to the Corn Laws.

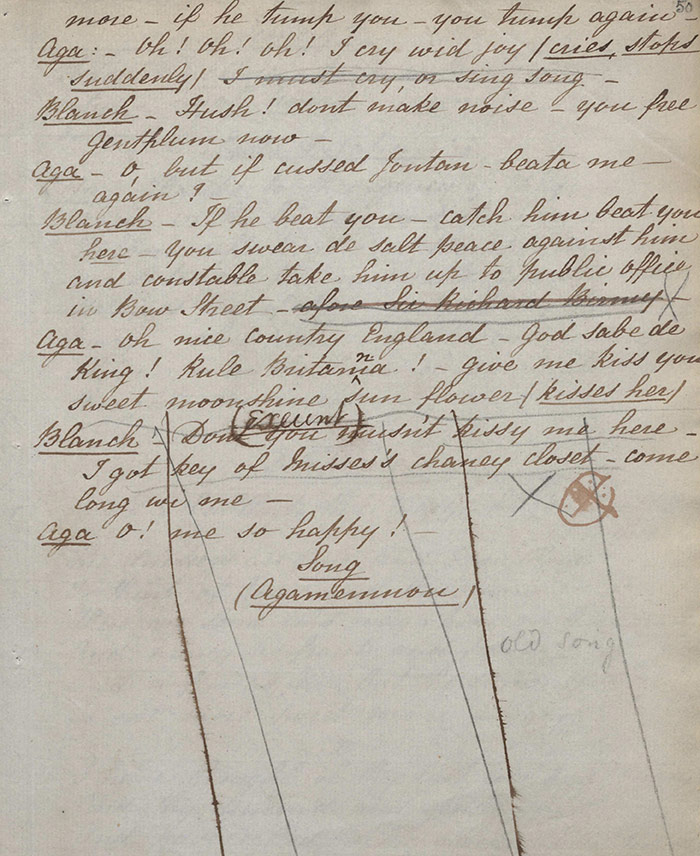

In keeping with a longstanding policy from Larpent’s day, references to real people were automatically deleted, even if neutral or approving: the chemist Humphry Davy (f.40v) and the police magistrate Sir Richard Birnie (f.50r) are two examples in this play. There is another intriguing excision, first marked on (f. 39r), where we can see that the character Mary’s name was originally Henrietta: it may of course be that this was a simple change for dramaturgical reasons but the possibility must remain that the name might identify the character with a real person for a contemporary audience, particularly given the number of references to real people in the text. Could Colman possibly be so draconian to infer that it might refer to the wife of Charles I and insist that this be inappropriate to the stage? This seems unlikely but as Mary Mitford was shortly to discover, he was ferocious when it came to the executed monarch.

To confuse matters even further, we also have a number of deletions in pencil. One of the more striking of these occurs on (f.45v) where the newspaper-reading Butler’s line ‘[Sir Leatherlip] would call mine democratical principles’ is struck through and also underlined with an ‘x’ underneath for good measure. This is suggestive as it was not marked out by Colman’s pen – red or black. Other penciled insertions suggest an authorial or managerial hand was wielding the pencil (e.g. f.46r, f.50r) so the possibility that the person making the deletion here, despite it being missed or approved by Colman, out of concern for negative audience reaction, exists. It is, of course, possible that Colman made a third pass through the text.

Some passages of text were marked out in red ink, black ink, and pencil as if to signal universal agreement (and perhaps contrition on the part of the manager/author) that these were not fit words to be spoken on the stage. We have an instance of ‘darned’ (f.36v) as well as a passage related to politics: ‘But what has a Liverpool postilion to do with American politics?’ (f.47r), probably a reference to the Prime Minister, the Earl of Liverpool although it is possibly to Canning, long associated with the city. See also the passage on politics deleted on the same folio and the replacement text inserted above. Attention was also paid to comments which passed blanket negative judgments on Americans such as that made by Lady Grossfeeder (f.52r).

A final curious deletion of red, black, and pencil is the description of Agamemnon and Blanch by Jonathan (f.49r) ‘sound mind and limb – no sandcracks – good match with the other, as to colour – tidy pair’. It would seem that even the comic mimicry of a slave sales-patter would not be acceptable in a post-abolition London. Despite this pseudo-liberal gesture, the play makes clear that black characters were also subject to embargoes as regards references to sexual activity when Blanche invites Agamemnon to join her in a closet for amorous purposes (f.50r).

As the reviews reveal, there was a mixed reaction to the play. The correspondence in the European Magazine appears to have taken its toll as Hodge has documented that Mathews withdrew the piece and never played it again (73). Public and self-censorship supplemented and exceeded Colman’s strictures.

Further reading

European Magazine (December 1825), 373-80, (January 1826), 59-67, and (February 1826), 179-87.

Francis Richard Hodge, Yankee Theatre: The Image of America on the Stage, 1825-1850 (Texas: University of Texas Press, 1964), 73-77.

Maura L. Jortner, ‘Throwing Insults Across the Ocean: Charles Mathews and the Staging of “the American” in 1824”, in Portrayals of Americans on the World Stage: Critical Essays, ed. by Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr. (Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), pp. 26-49.

Anne Jackson Mathews, Memoirs of Charles Mathews, Comedian (London: Richard Bentley, 1838-39), III, 511-53.

[available on archive.org. Hathitrust.org]

Matthew Pethers, ‘That Eternal Ghost of Trade: Anglo-American Market

Culture and the Antebellum Stage Yankee’, in The Materials of Exchange between Britain and North East America, 1750-1900, ed. by Daniel Maudlin and Robin Peel (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), pp. 83-116.

John Russell Stephens, ‘Peake, Richard Brinsley (1792–1847)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21684, accessed 5 Aug 2016]

Richard Brinsley Peake, Memoirs of the Colman family, including their correspondence with the most distinguished personages of their time (London: Richard Bentley 1841), 2 vols.

[available on archive.org. Hathitrust.org]