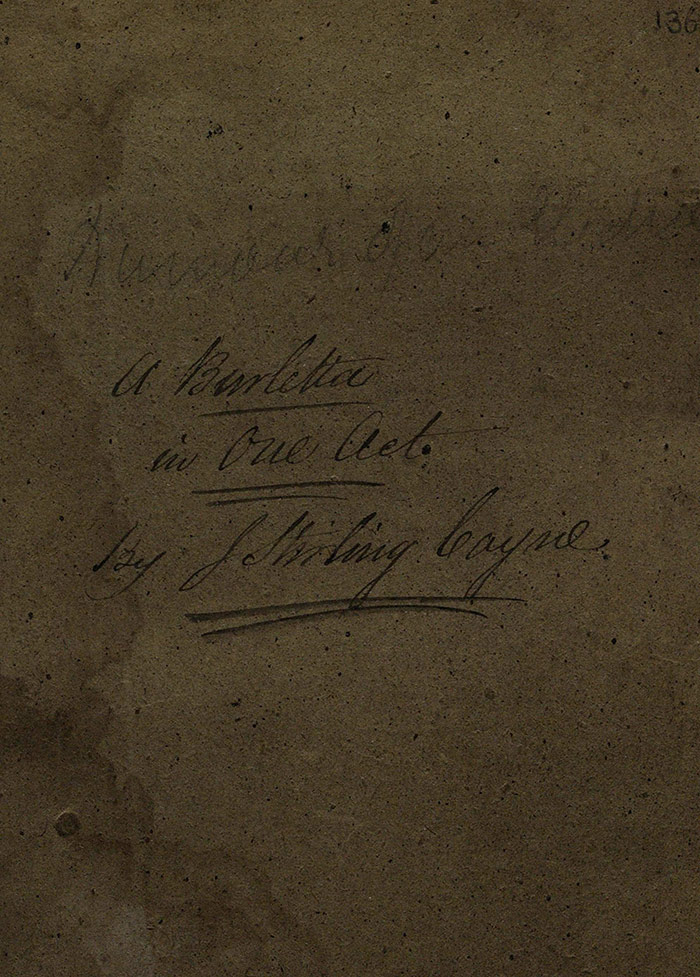

The Humours of an Election (1837) BL ADD MSS 42940, ff. 136-178

Author

Joseph Stirling Coyne (1803-1868)

Coyne was born in Offaly and schooled in Tyrone. Early success with his comedy The Phrenologist (1835) caused him to abandon a planned career in the law for the theatrical life. He went to London in 1836 with a letter of introduction from William Carleton which opened doors to literary journals. He wrote his first London comedy, The Queer Subject, for the Adelphi Theatre where it was performed in November 1836.

He was one of the original co-editors of Punch magazine with Horace Mayhew and Mark Lemon. However, Coyne was caught plagiarizing from an Irish newspaper which put paid to his contributions. Nonetheless, he continued to contribute to newspapers and journals (Irish stereotypes being a noted feature of his work); he eventually became drama critic for the Sunday Times.

Coyne wrote plays for the Adelphi, the Olympic, and the Haymarket, developing a penchant for one-act domestic farces. His greatest successes included Binks the Bagman (1843), Did you ever send your wife to Camberwell? (1846), and How to Settle your Accounts with your Laundress (1847). As well as The Humours of an Election, Coyne had censorship difficulties with Lola Montes (Haymarket, 1848): his depiction of the mistress of Ludvig I of Bavaria, who was perceived to have provoked a revolution, meant that the play was withdrawn after two nights until all royal allusions were removed. As John Russell Stephens has noted, she claimed Irish birth which did not help the play’s cause and it provides a useful point of comparison with this drama’s depiction of Daniel O’Connell.

Coyne was appointed secretary to the Dramatic Authors’ Society in 1856 and he was instrumental in developing a system of fixed performance fees for dramatists as well as ensuring rural theatres paid their dues. He wrote over 60 plays in all, some co-authored, before he died of cancer in 1868.

Plot

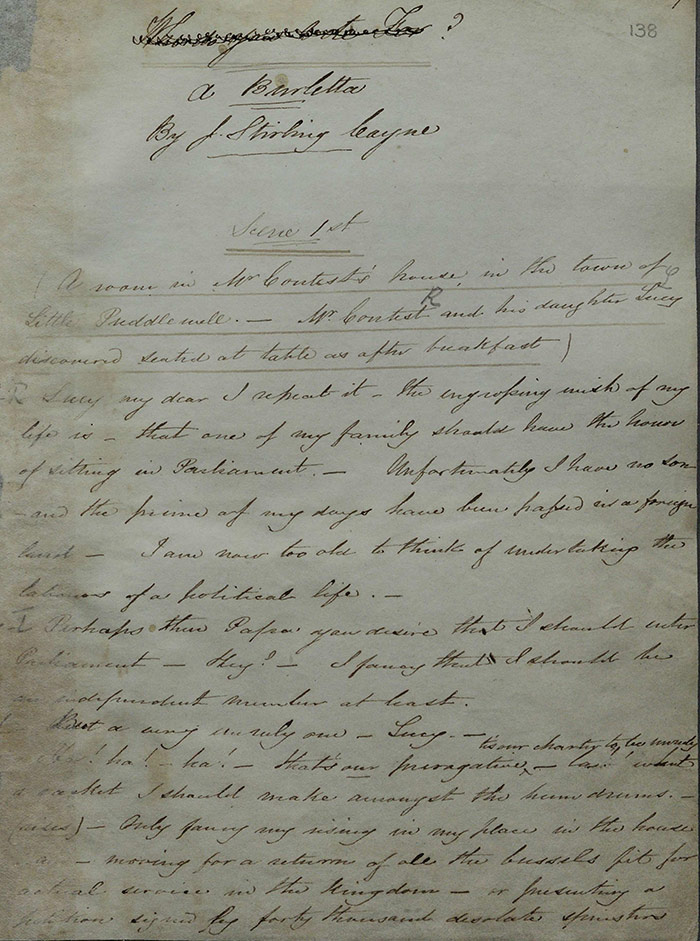

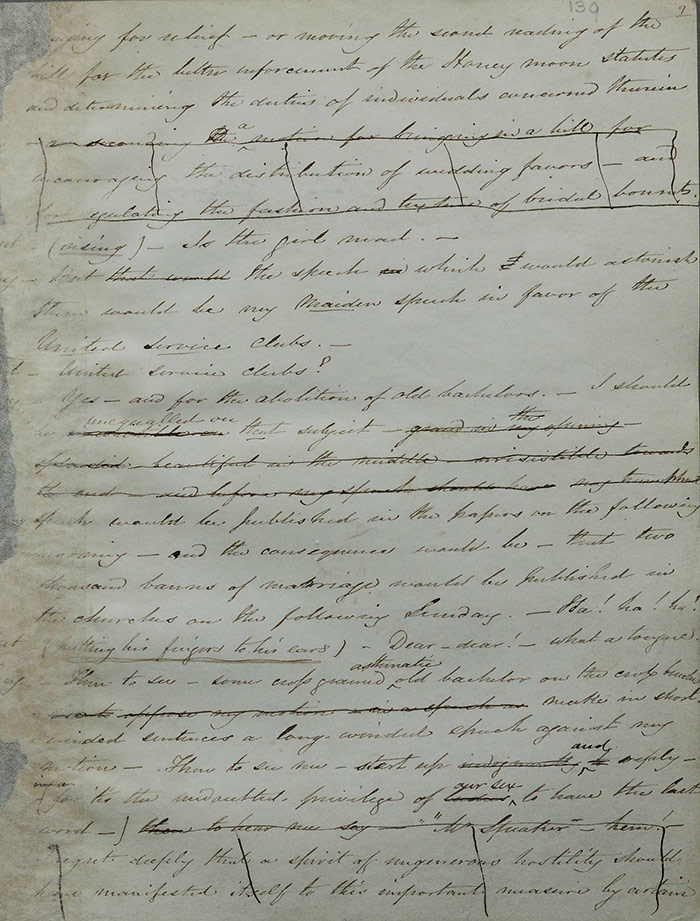

The one-act burletta is set in the town of Little Puddlewell where Mr Contest has declared that his daughter will marry no one but an MP. Lucy is distraught as her lover, Melton, is not polling well. The leading candidate, Pigwiggin, a retired cheese-monger, seems unassailable as he has the support of a duplicitous election agent, Mr Bustle. When Lucy tells Frank of her father’s decree, he is despairing but Lucy insists Pigwiggin’s populist support is easily turned around and she is determined to take action.

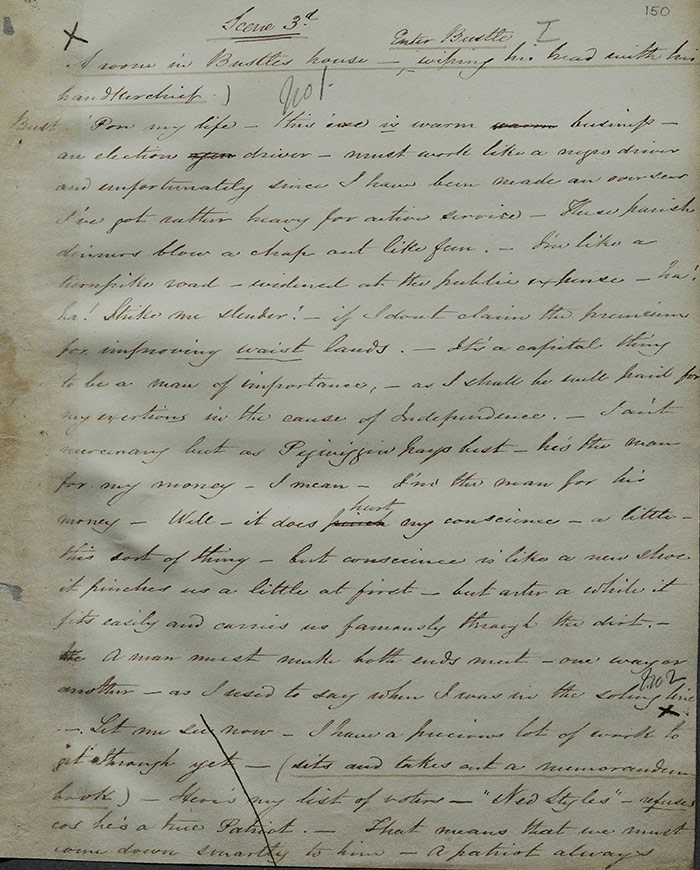

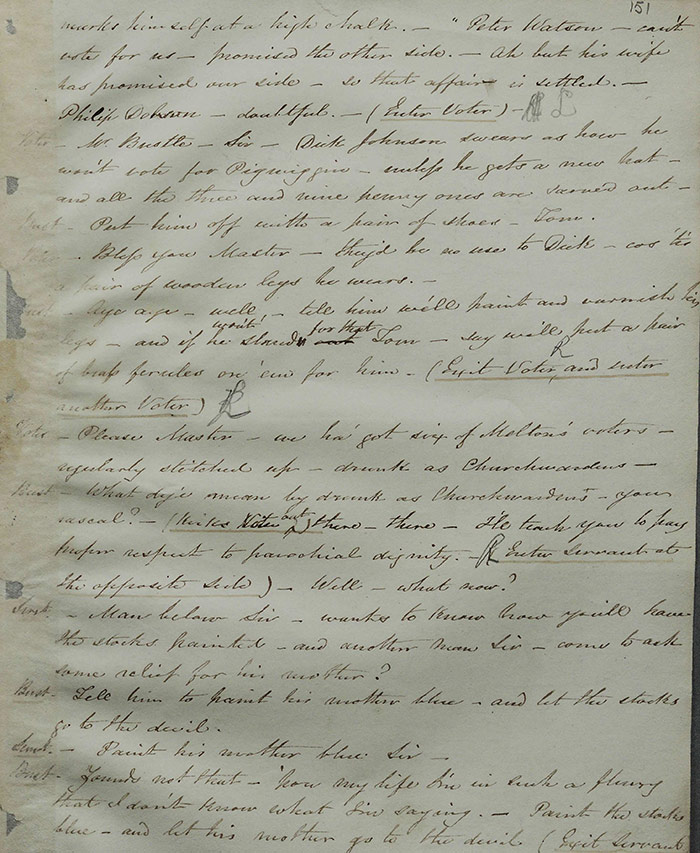

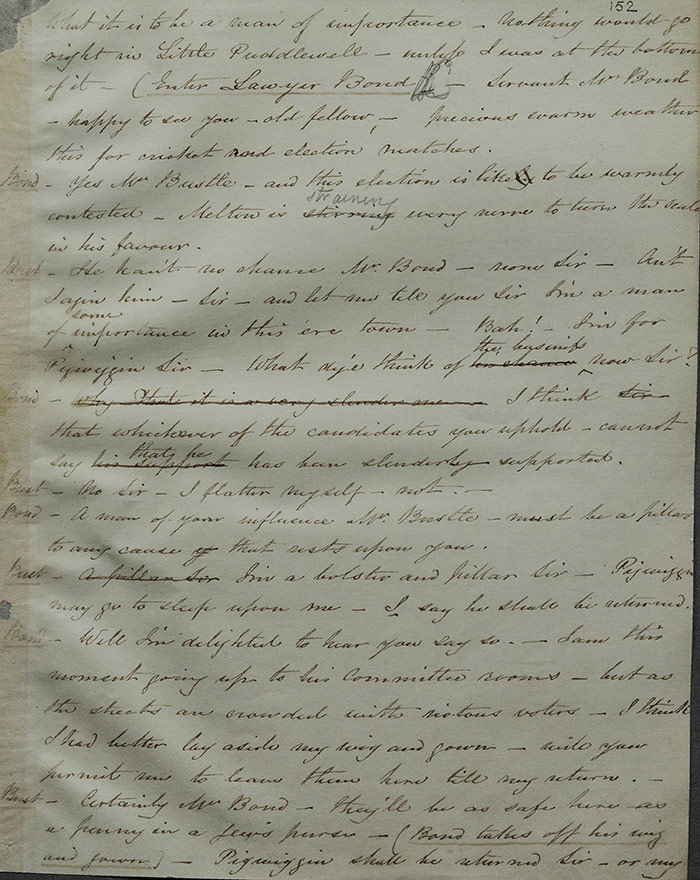

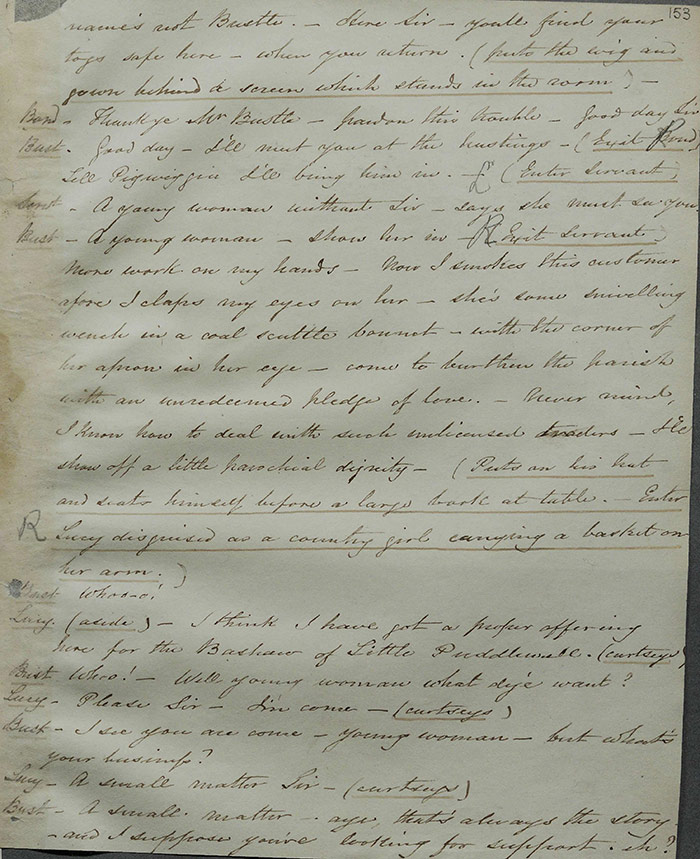

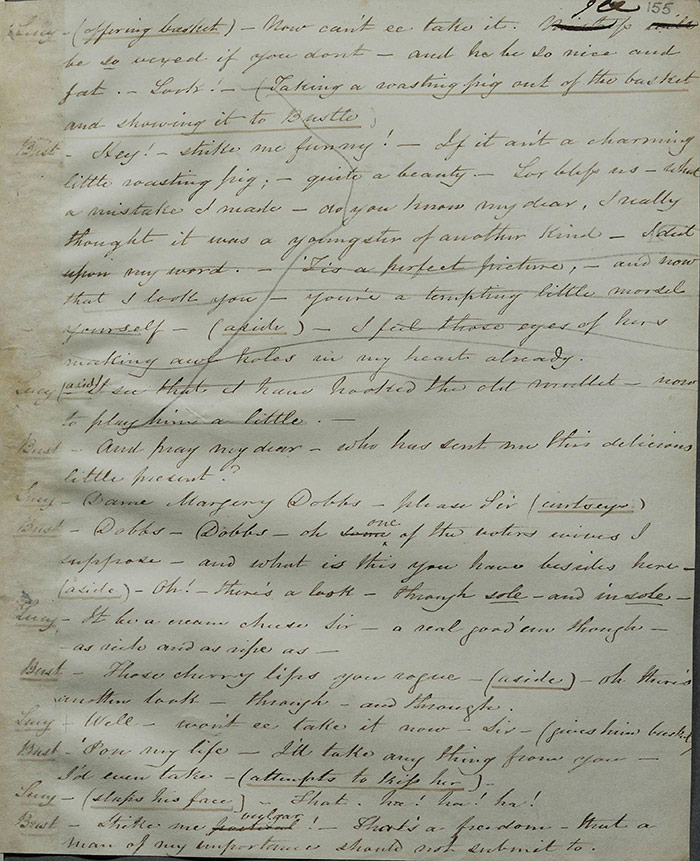

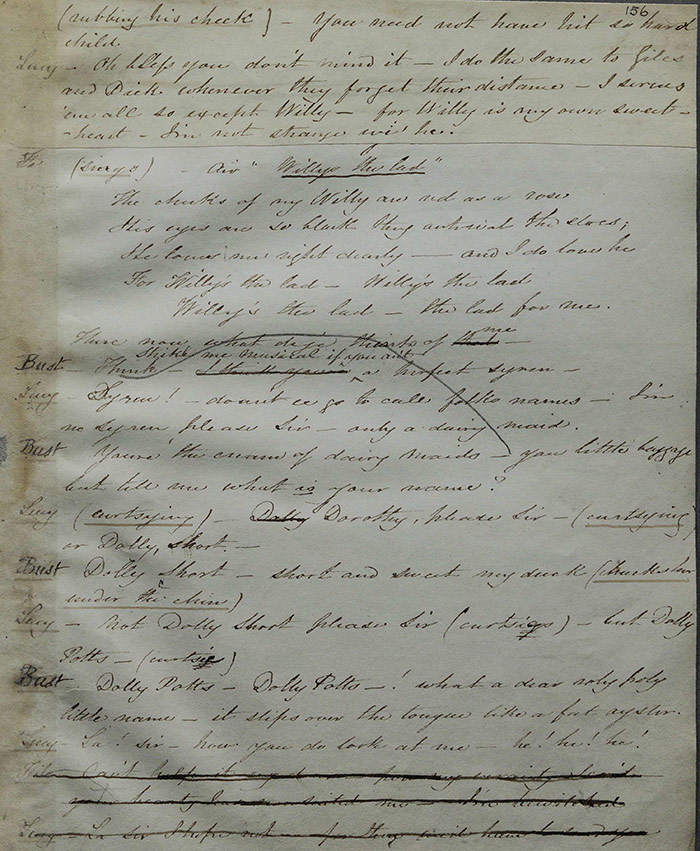

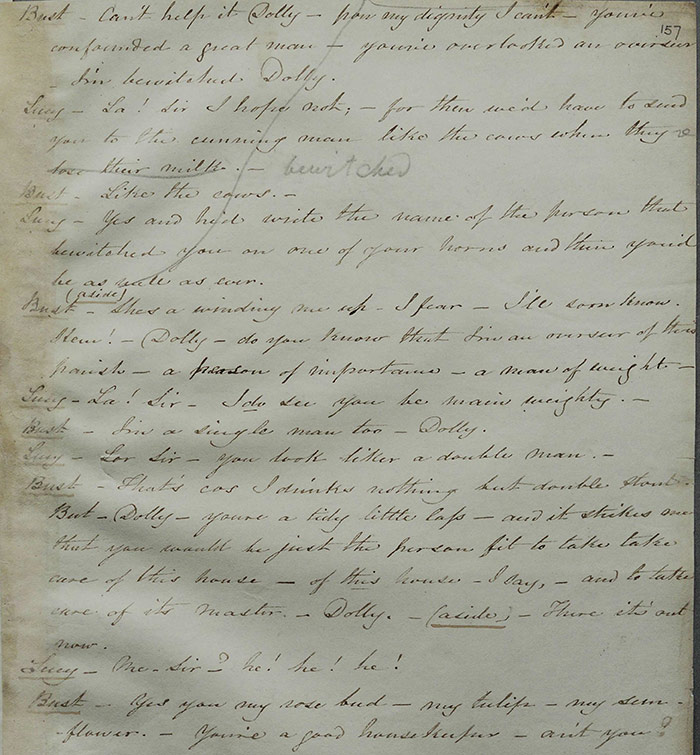

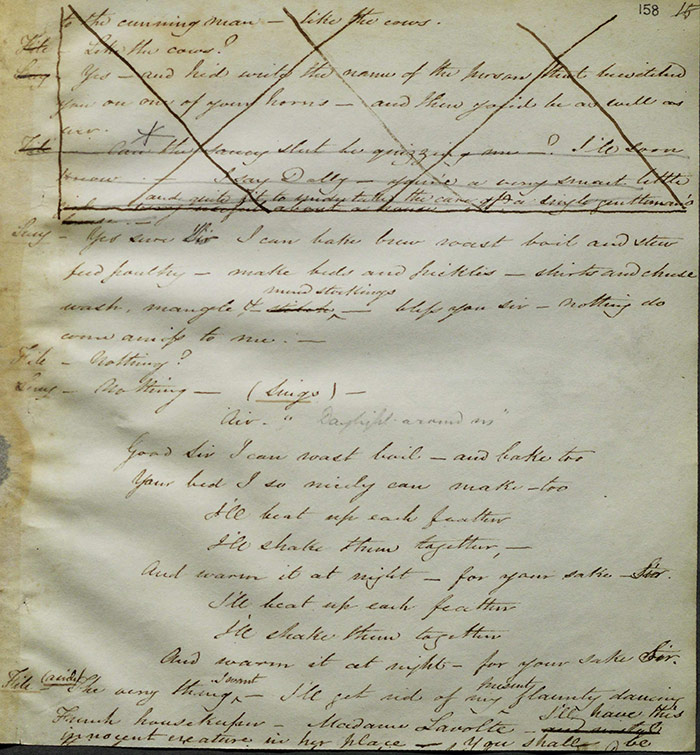

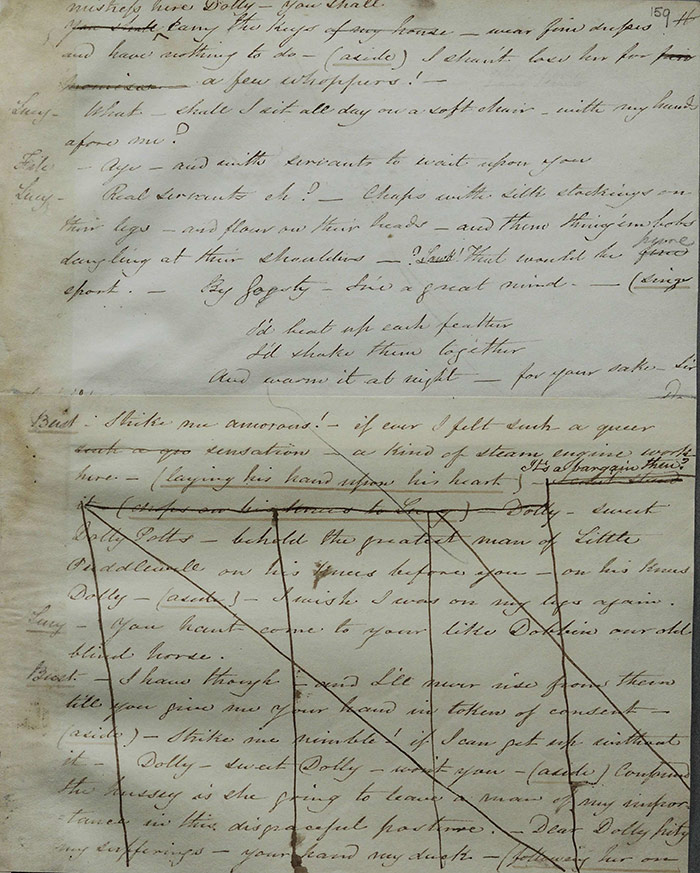

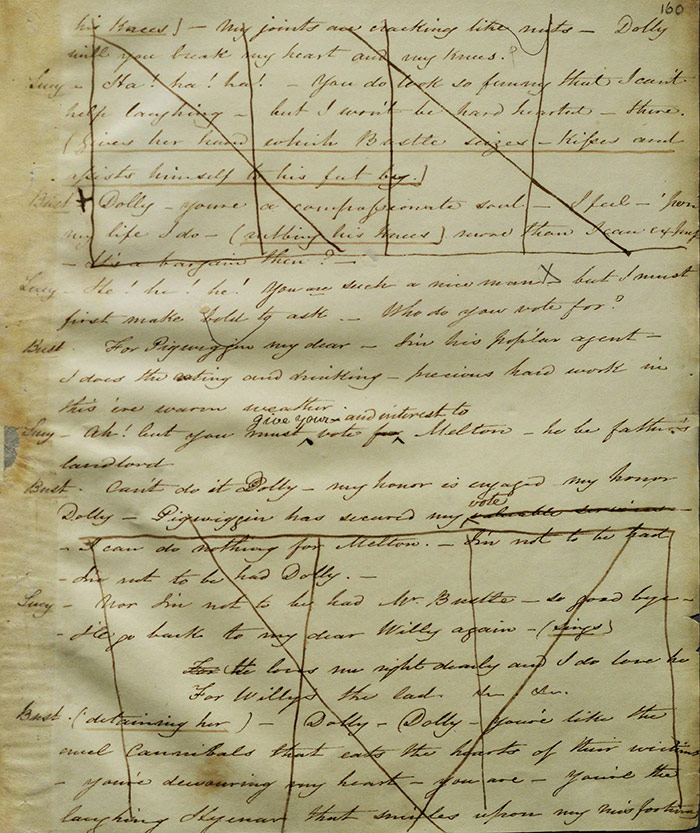

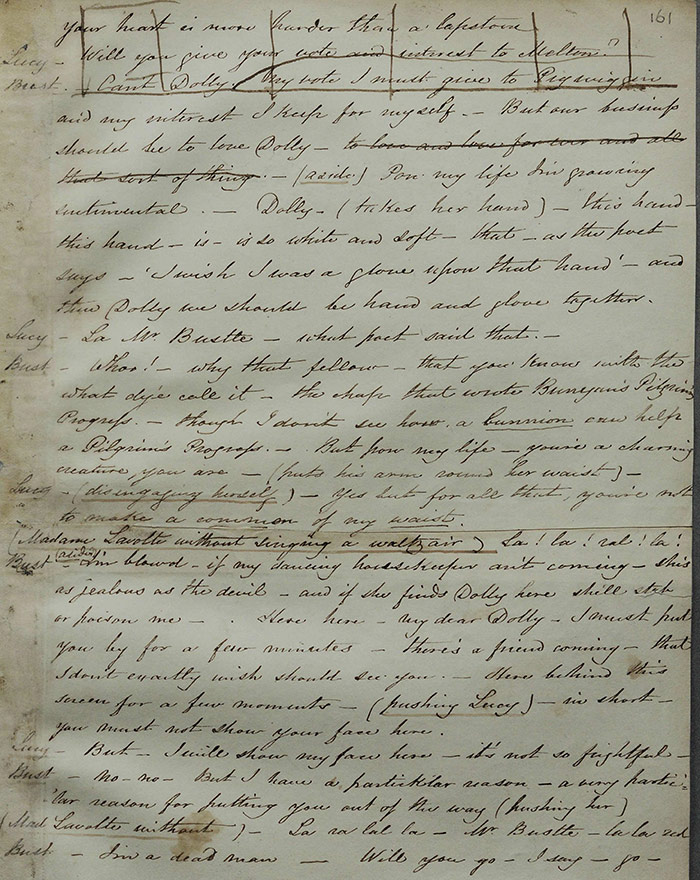

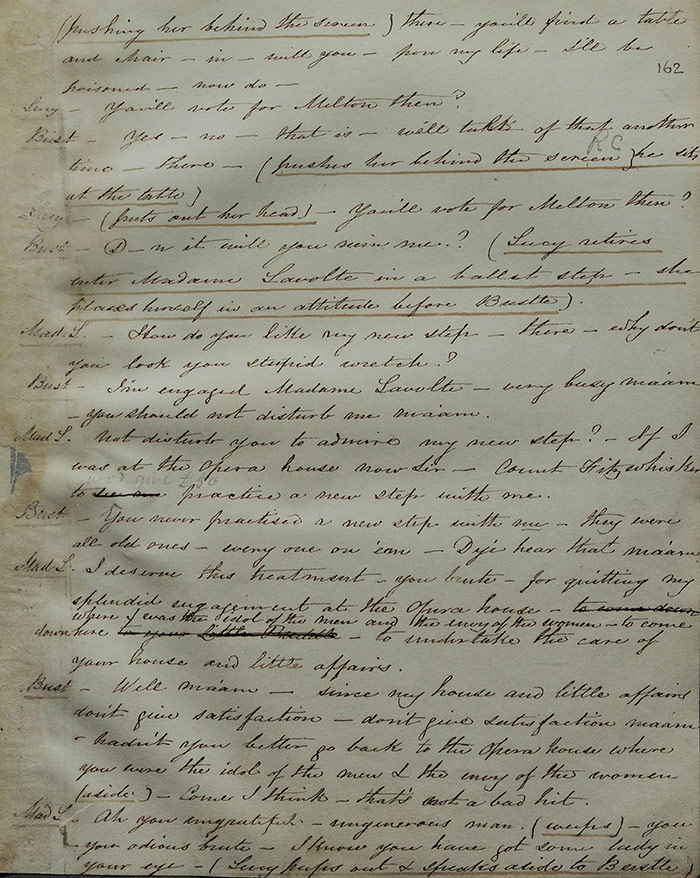

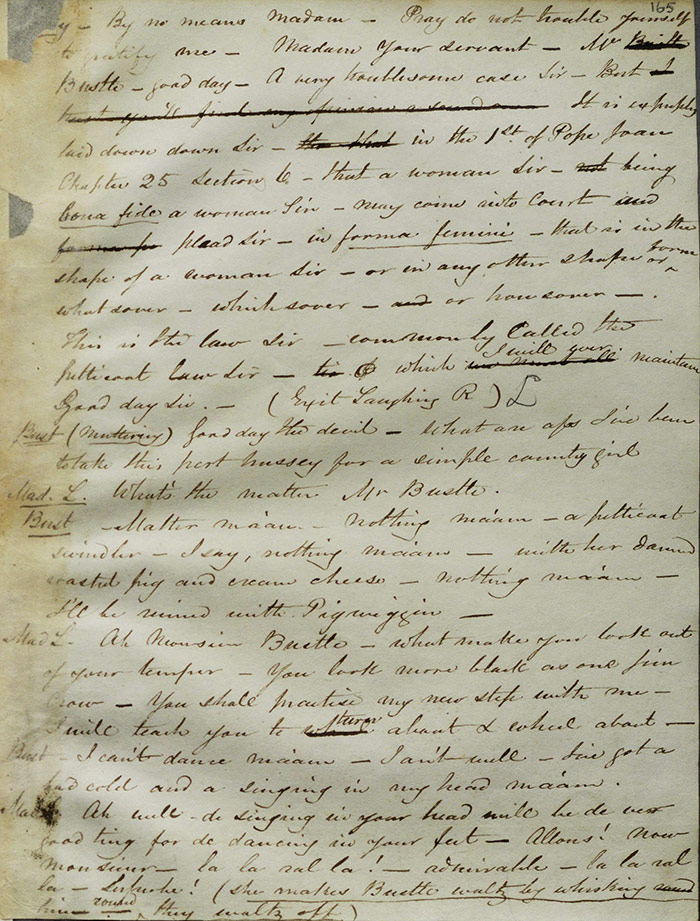

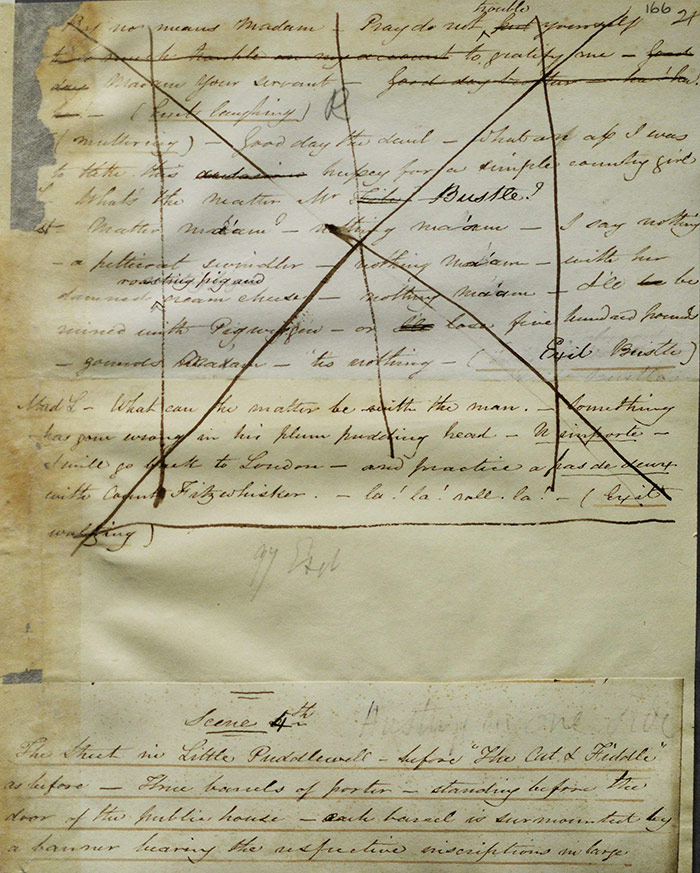

In the second scene, Bustle is busy bribing voters to support Pigwiggin. The third scene finds him dealing with further voter issues when the lawyer Mr Bond enters. Bond wants to check up on where the poll stands and Bustle reassures him all is well. Satisfied, Bond returns to Pigwiggin’s committee rooms but decides to leave his wig and robe with Bustle as the street is full of riotous voters. Bustle places them behind a screen in the room for safe keeping. When Bond leaves, a servant announces that a young lady has come to see Bustle. Lucy enters, disguised as a country girl and calling herself Dolly Potts. She is carrying a small basket. A comedic conversation at cross-purposes follows where Lucy is seeking Bustle’s support for Melton while he is convinced that she has a baby in her basket and is looking for money. Lucy then presents him with a little roasting pig as a gesture of goodwill and he realizes the misunderstanding. And now Bustle begins to lasciviously eye Lucy up. He tries to kiss her and she replies with a slap. His rhetoric gets increasingly warm and soon he is on his knees promising to make her mistress of his home. She asks that he transfer his vote to Melton, claiming that he is her (imaginary) lover’s father. Bustle refuses but continues his amorous pursuit. But when he hears his ‘dancing housekeeper’, Madame Lavolte, singing nearby, he begins to panic. He is petrified of her jealousy should Dolly be discovered. Frantic, he pushes Lucy hurriedly behind the screen. Madame Lavolte and Bustle have a spiky exchange during which Lucy betrays her hiding place by laughing. Madame Lavolte draws a dagger and rushes to uncover her concealed rival.

However, Lucy has disguised herself with the lawyer’s robe and wig and is writing at a table. Bustle’s relief at her quick-thinking subterfuge is short-lived as Lucy hands him the document to sign. It is a commitment to support Melton or forfeit £500; if he refuses to sign, she will reveal herself to Madame Lavolte. He eventually capitulates with ill grace and Lucy leaves, laughing.

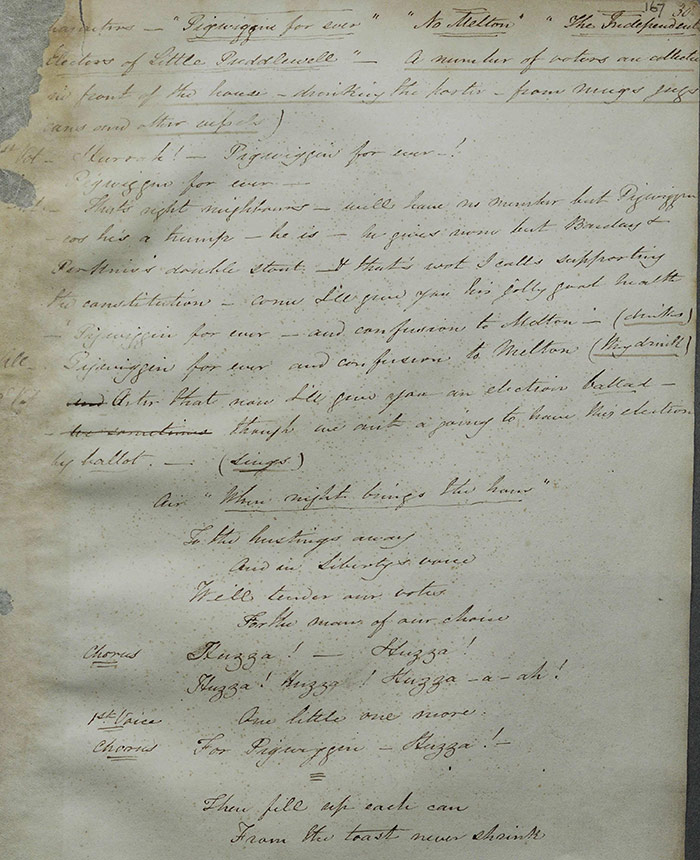

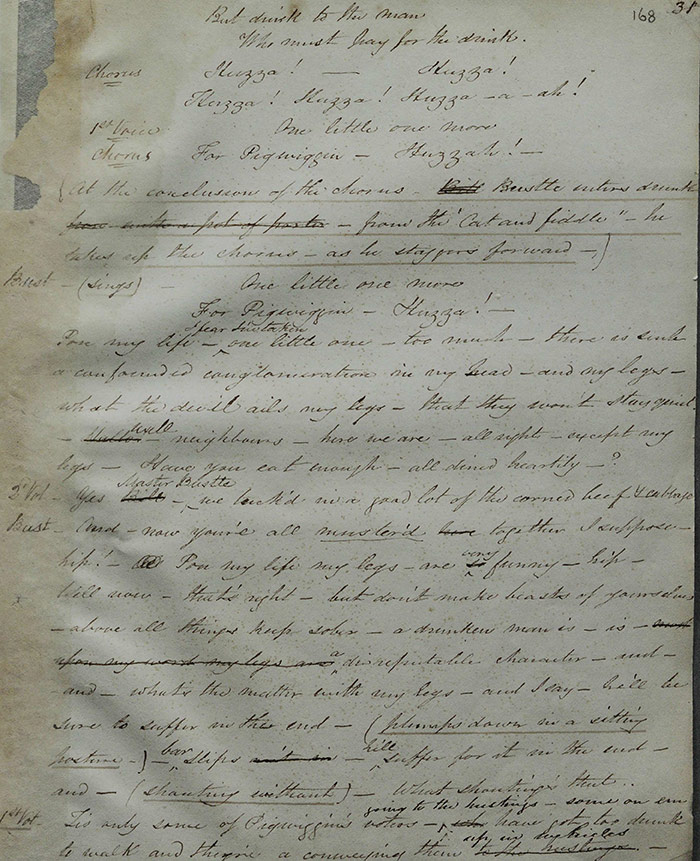

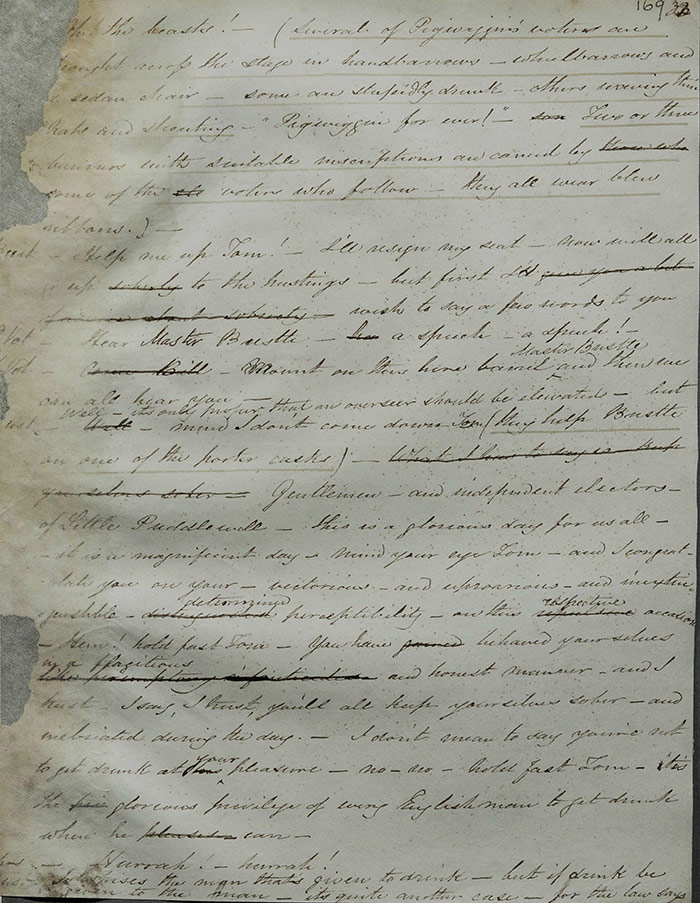

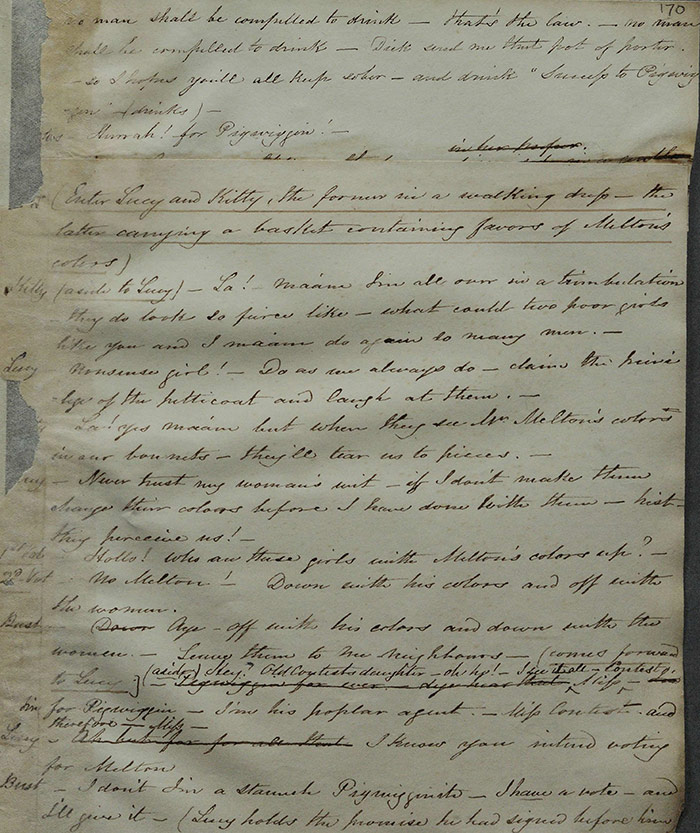

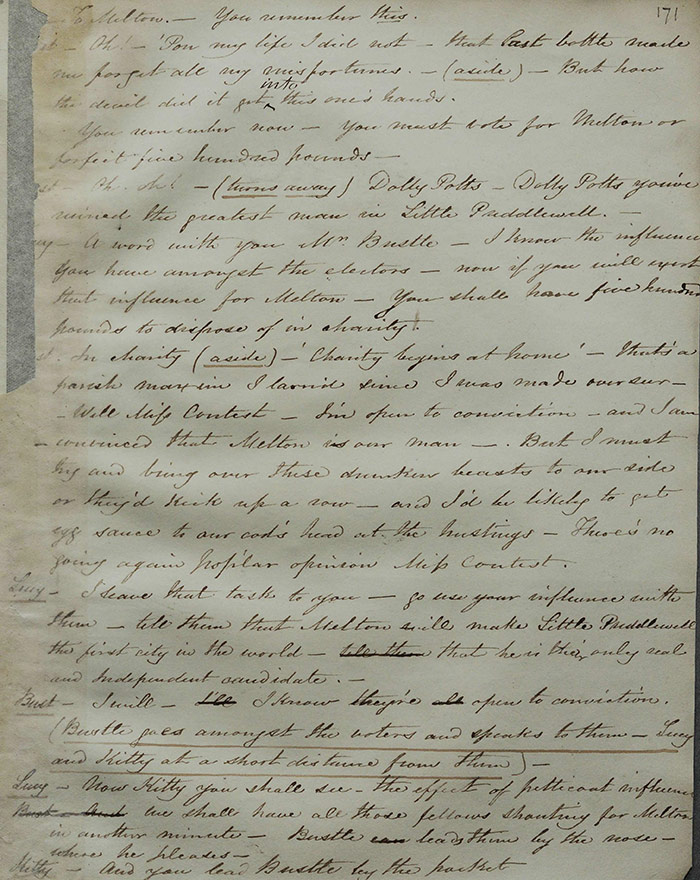

The fourth scene opens on a Little Puddlewell street with voters drinking the beer provided by the candidates. Bustle enters, very drunk (as are many of Pigwiggin’s supporters), and calls on support for Pigwiggin. Lucy and her maid Kitty (described in the dramatis personae as ‘a miracle – a lady’s maid who says little or nothing’) enter with a basket of Melton’s favours (i.e. ribbons indicating support). Kitty is apprehensive of antagonism from Pigwiggin’s supporters but Lucy is confident. Bustle steps forward to dismiss them and Lucy presents him with the document he has signed. He is forced to comply but then Lucy offers him £500 to turn the rest of the voters. Ever the opportunist, he negotiates an additional £100 and ensures the voters shout for Melton.

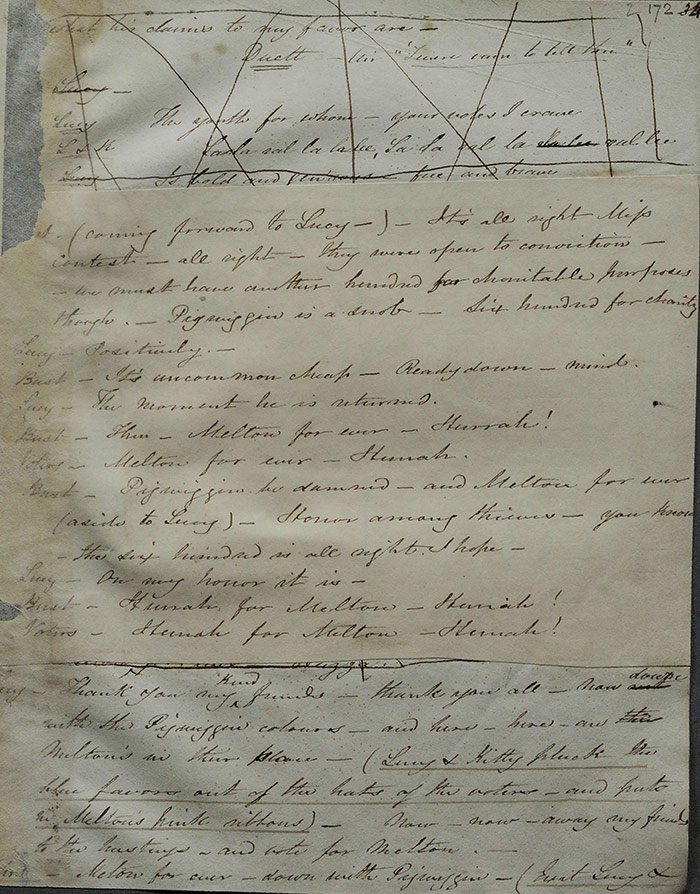

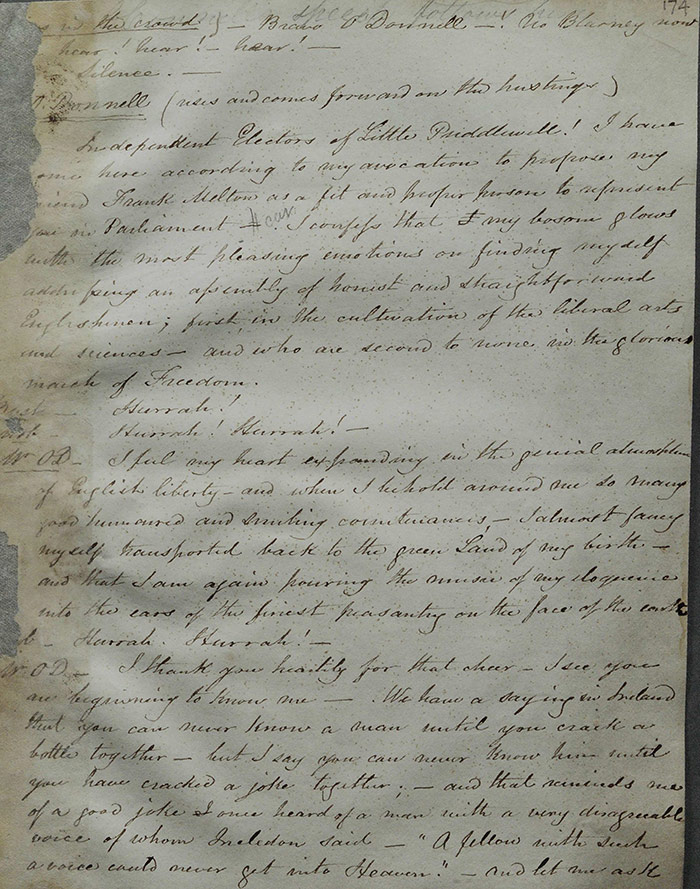

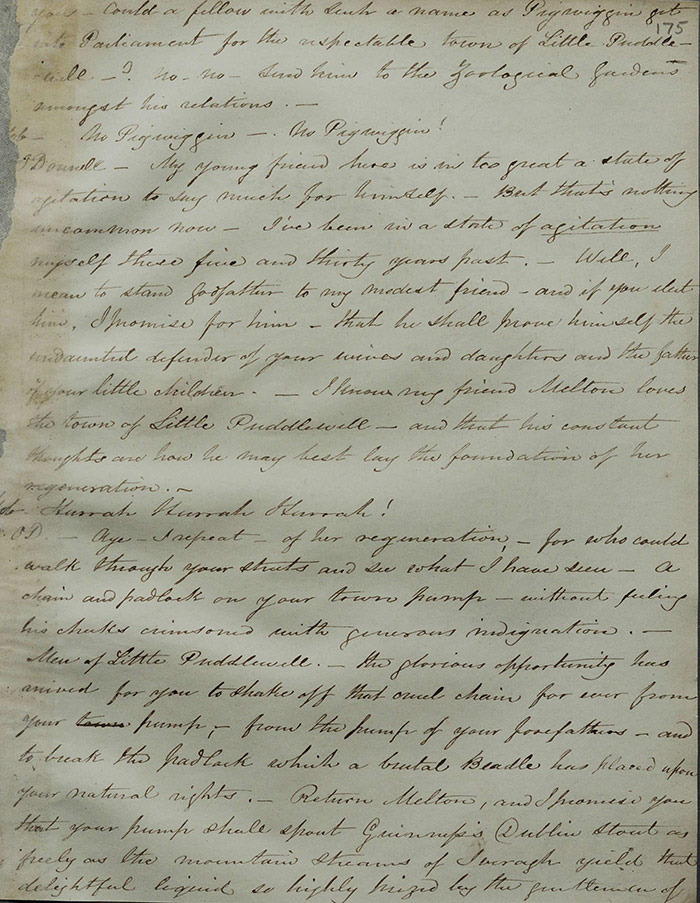

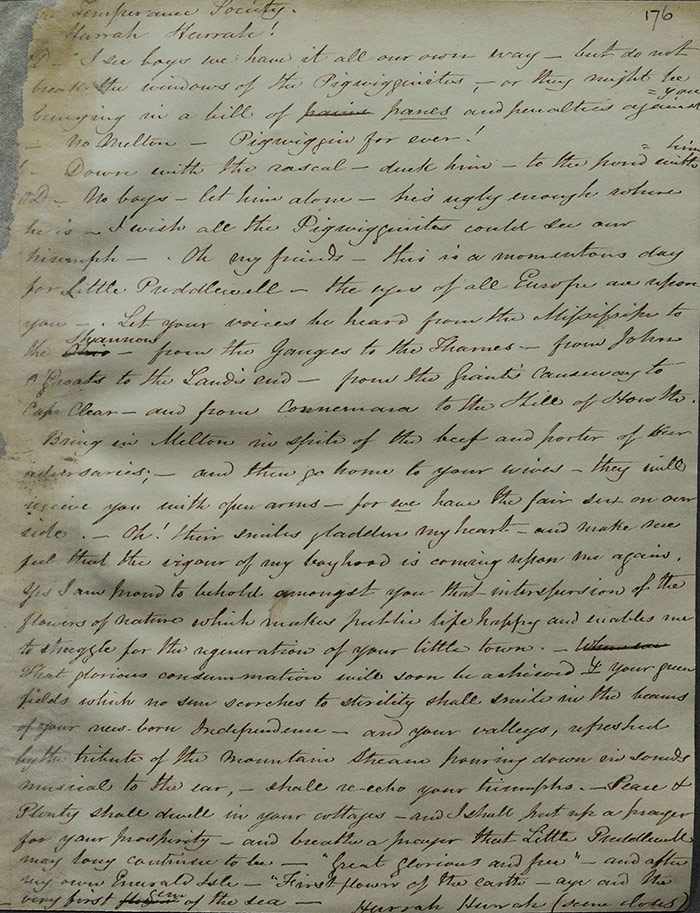

The fifth scene takes place at the hustings. The mayor presides and on one side we have Pigwiggin and his proposer Mr Lobb; on the other, we have Melton and his proposer Mr O’Donnell. Lobb speaks first – he is brief and to the point, promising a slap-up election dinner should Pigwiggin be elected. O’Donnell follows with a much more eloquent and lengthier speech. He celebrates English liberty, skewers Pigwiggin on the grounds of his silly name, before lauding Melton’s honour and love of Little Puddlewell. His powerful and exuberant rhetoric wins the crowd for Melton.

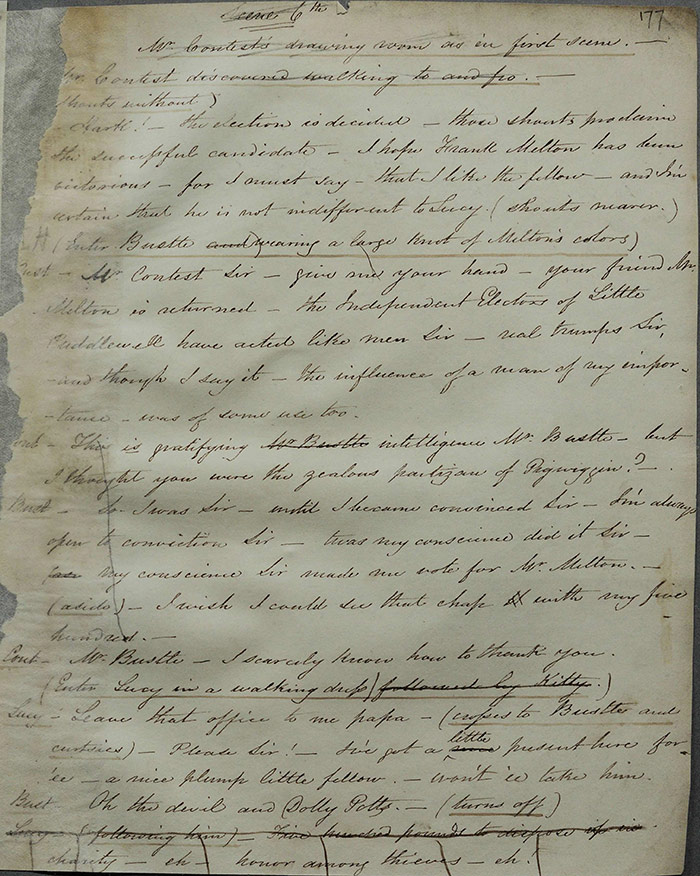

The final scene returns us to Mr Contest’s drawing room. He is delighted to hear of Melton’s success. Bustle learns that Dolly Potts was really Lucy in disguise but she stands by her promise to pay him £600. They are all reconciled and agree to dine together. The curtain falls briefly before lifting to reveal the characters disposed in a tableau inspired by William Hogarth’s Chairing the Member (1755), the fourth and final painting of his The Humours of an Election series.

Performance, publication, and reception

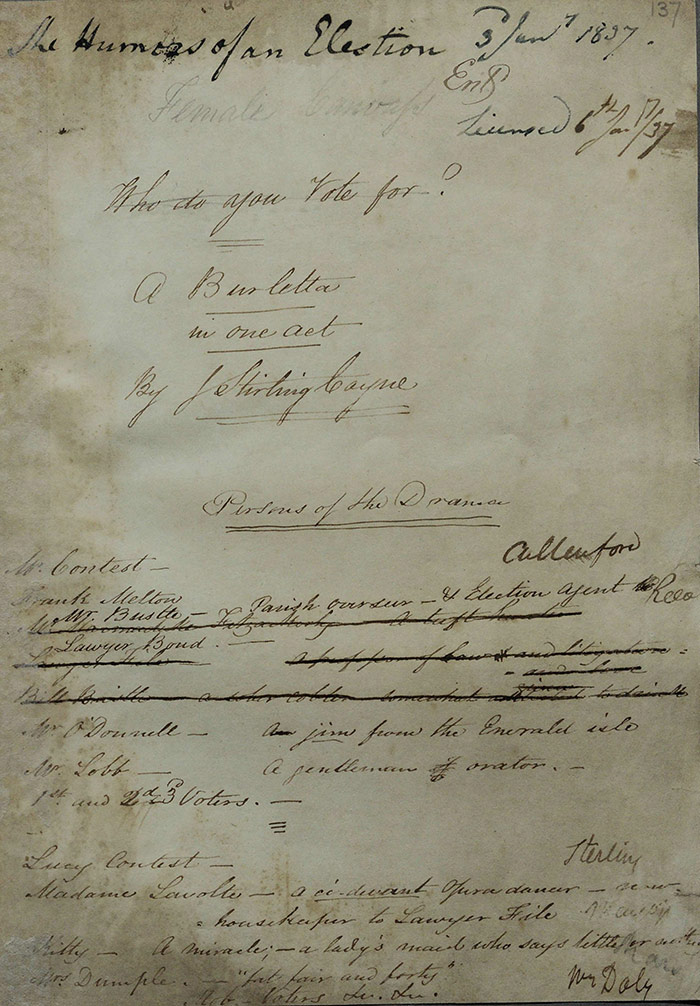

The manuscript was submitted on 3 January 1837 by Adelphi manager Frederick Yates and it was licensed on 6 January. The play was first performed on 9 January. The manuscript indicates that two other titles were also considered: The Female Canvass and Who Do You Vote For? The burletta was a resounding success and had 23 performances that season with the final performance on 4 February. It was, however, a one-season wonder as it was not staged the following season.

The reviews of the play were all positive and they all agree on the chief attraction of the piece. The Literary Gazette (14 January 1837) liked the play which it believed was produced to ‘good effect’. It was very impressed by the cast: John Reeves (Bustle) was ‘hardly ever [seen] more funny, or more perfect’. However, the writer reserved particular praise for the new Irish actor playing O’Donnell:

[…] the chief novel feature was Mr. Fitzgerald, whose imitations of O’Connell were excellent. He preserved all the originality of the agitator, without offending the politics of anyone; and Whig, Tory, and Liberal, joined in a hearty laugh at his personation.

The Observer (15 January 1837) was equally pleased with the new arrival from Ireland who was the ‘great feature’ of the farce. The reviewer argued that ‘the imitation was as close to the original as it is possible for the efforts of mimicry to bring an imitation to the likeness of reality’. There were some notes of disapproval though with the burletta being thought ‘a great deal too long’, in particular the scene between Bustle and Lucy was thought to be overcooked. The Theatrical Observer (11 January 1838) was even more effusive in its praise of Fitzgerald’s mimicry:

In the election scene Mr. Fitzgerald, as O’Donnell, addressed the electors in favor of one of the candidates, and gave a most capital imitation of the manner of the great Agitator; the roll, the swagger, the tugging at wig and neckcloth, the arms akimbo, and the easy confidence, were perfect fac similes; it was equal to any thing of the kind even the Prince of Mimics, poor [Charles] Mathews, ever did, and it agitated the sides and the hands of the audience most powerfully.

The Times (10 January 1837) was similarly impressed by the play, albeit somewhat begrudgingly. The conservative newspaper was implacably opposed to the reform agenda of Daniel O’Connell and could not resist including a jibe at O’Connell in praising Fitzgerald who produced ‘an admirable specimen of the claptrap vulgarities and tawdry configurations which bedaub the eloquence of the person depicted’.

The play was never published.

Commentary

The manuscript has a number of emendations and deletions in both pen and pencil. Unlike the other manuscripts selected, one could argue that it is a curious choice for this resource in some respects as it is unlikely that the Examiner made any of the interventions on the manuscript. Thus, its inclusion warrants some supplementary justification before we address the manuscript proper.

Charles Kemble (1775-1854) had been appointed Examiner of Plays on 27 October 1836 after George Colman’s death. The manager of Drury Lane, Alfred Bunn, was angered by the appointment, arguing—quite reasonably—that it was quite unfair to have one of the management team at Covent Garden sitting in judgement on his theatre’s plays. Whether Kemble’s conscience was troubled by this conflict of interest is unlikely but he did end his professional engagements at Covent Garden on 23 December (playing Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing). Coyne’s The Humours of an Election then is one of the first plays that he would have considered when he was fully dedicated to the Examinership and provides a useful comparison to his predecessor’s approach to the job. As The Humours of the Election suggests, Kemble saw the job as little more than a sinecure, a reward for his considerable contribution to London’s theatrical life.

John Russell Stephens has documented in some detail Kemble’s apathy toward his censorship role. After one year in the job he went abroad and delegated his duties to his son, John Mitchell Kemble. But even in the year he was in situ in London, he made little effort to stem moral or political outrage on the city’s theatrical boards, reading barely any of the manuscripts he was sent. During Colman’s tenure (he lasted until February 1840), his son deputized frequently for him and Charles Kemble arranged the formal transfer of his office to him in 1840 (Stephens, 25-27).

Rather neatly, the play also offers another contrast to Colman but this time in his capacity as a playwright. His 1784 comedy The Election of the Managers, also included in this resource, was heavily censored for its caustic representation of British electoral activities. The Humours of an Election, which takes its title from Hogarth’s mid-eighteenth century series of paintings, provides a useful window into popular perceptions of how elections operated and how they had changed over a half century. Interested readers may also wish to compare this play to The Hustings (1818; included in this resource) and Frederick Pilon’s The Humours of an Election (1780). Finally, it is worth noting that although an election did take place in 1837, prompted by the death of William IV on 20 June, this play was written and performed well before that event.

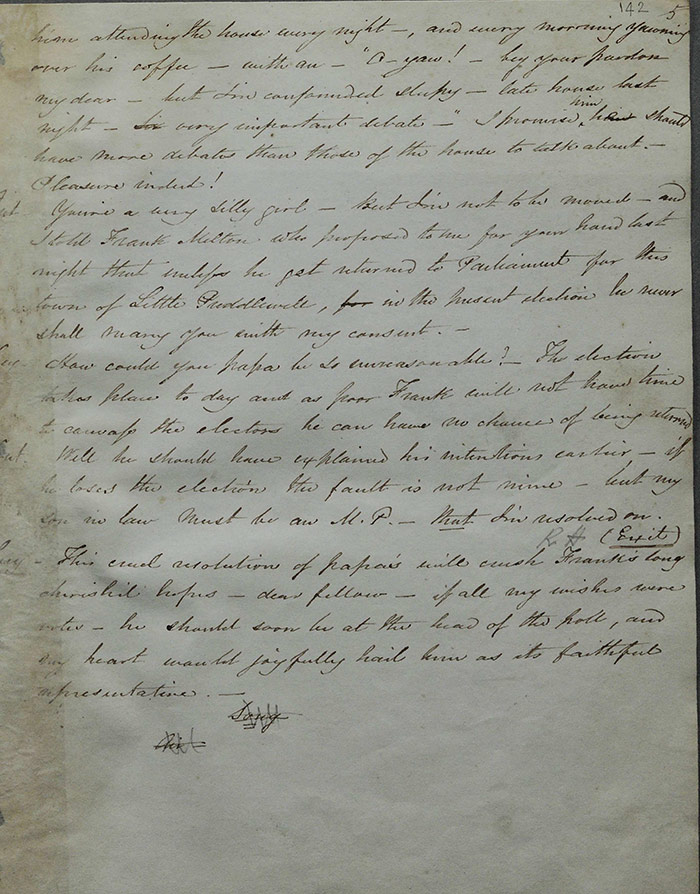

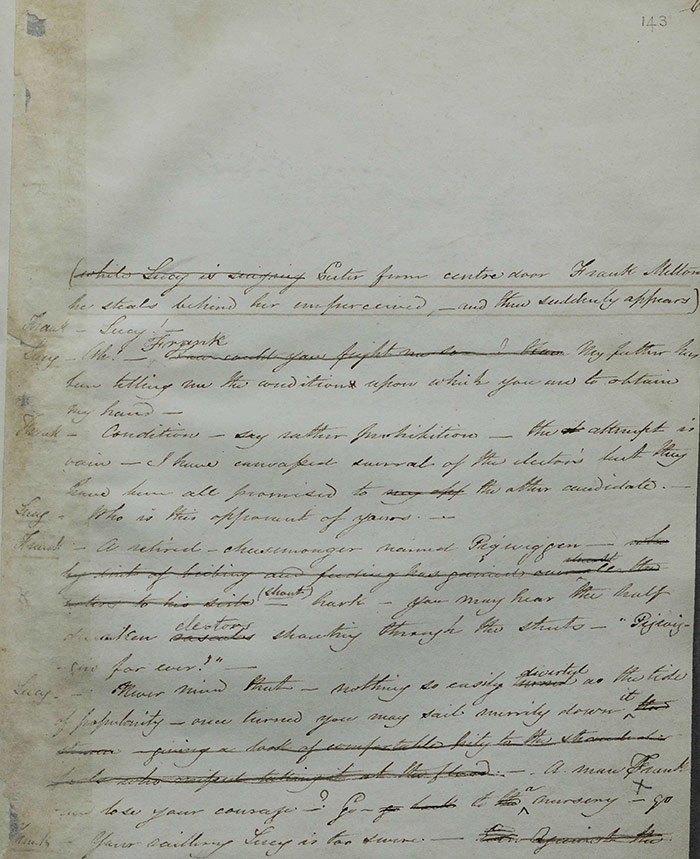

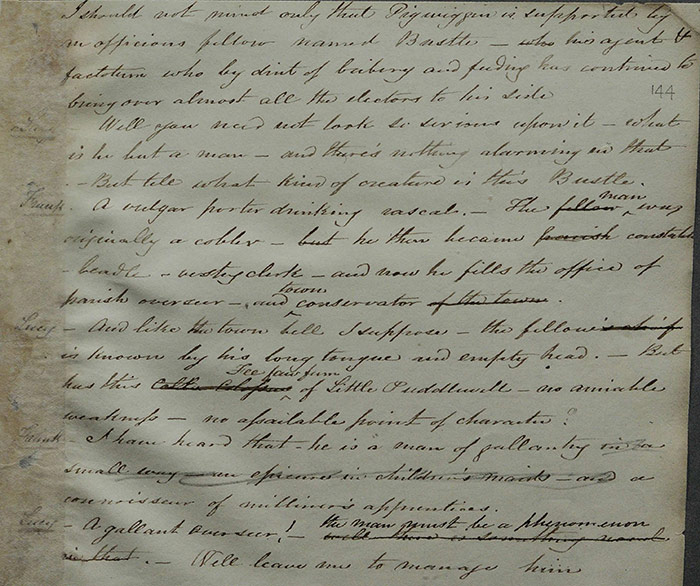

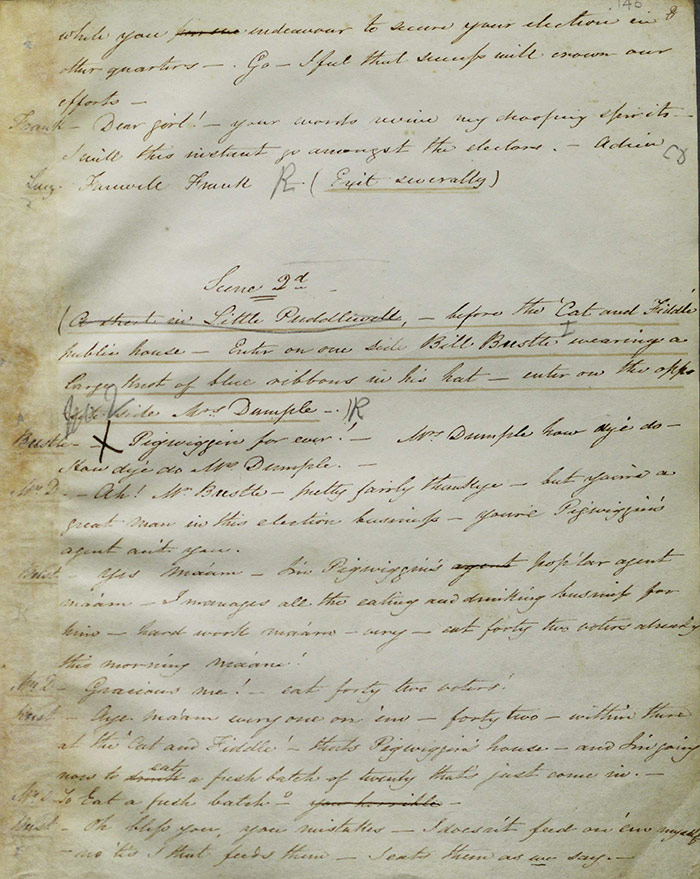

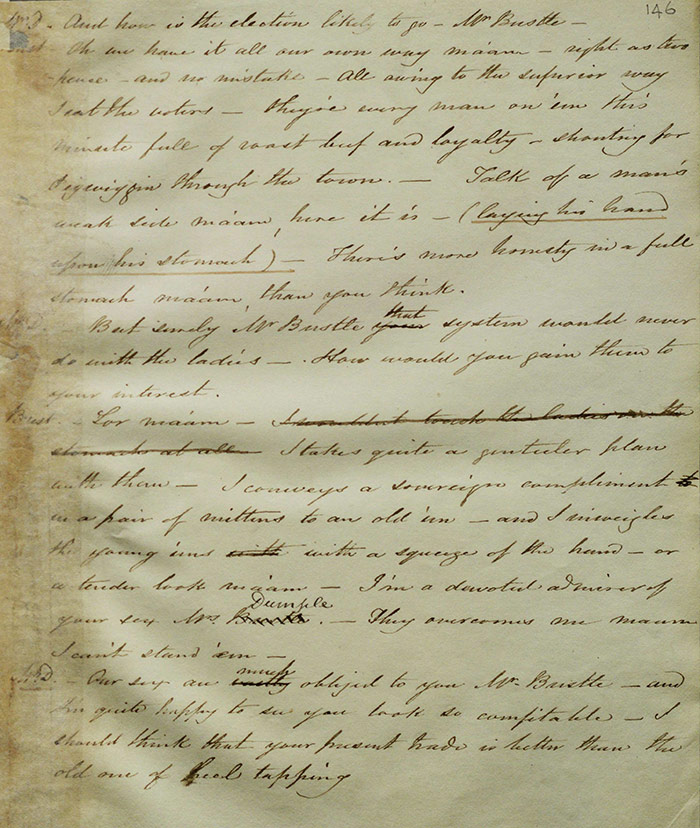

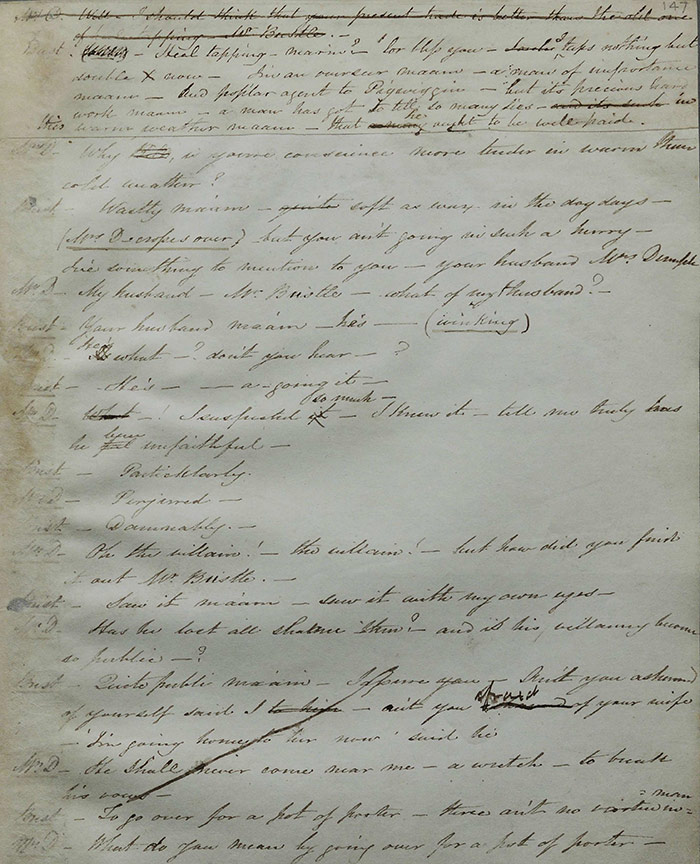

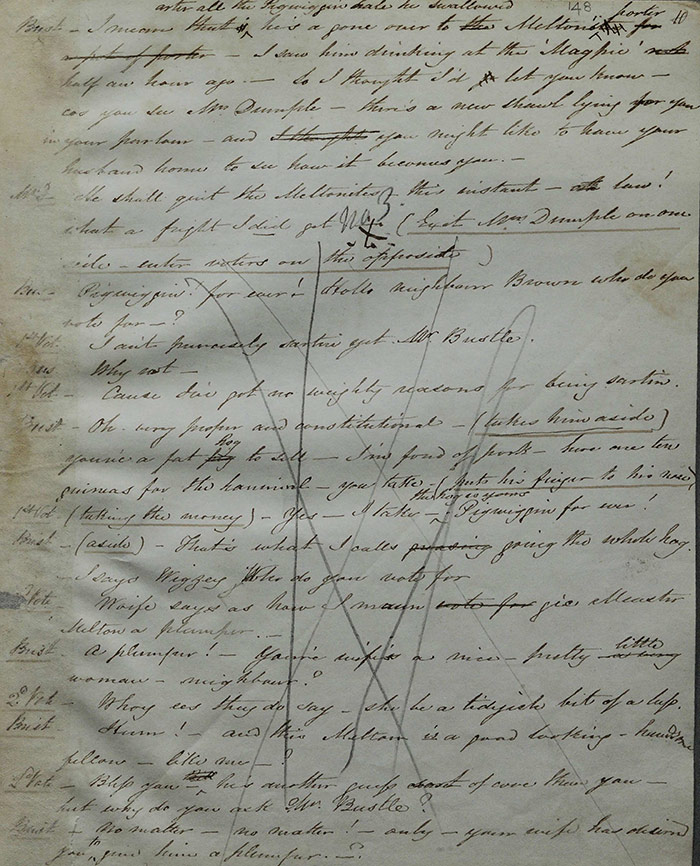

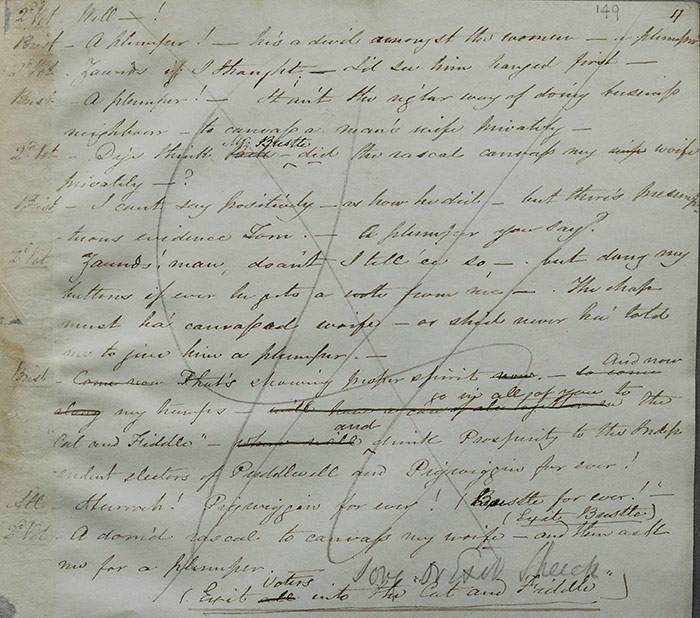

The manuscript nonetheless does possess some intrinsic interest in terms of censorship. There are probably two hands at work on the manuscript, one marking in pen and the other in pencil. The manuscript is very heavily marked throughout, and it is evident that most of the changes were driven by dramaturgical motivations, for instance, to shorten the burletta or to amend characters’ names (see the deleted folios ff.148-149 for example). The penciled emendations also introduce a number of stage directions. However, there were also some changes that may have been motivated by a concern over censorship.

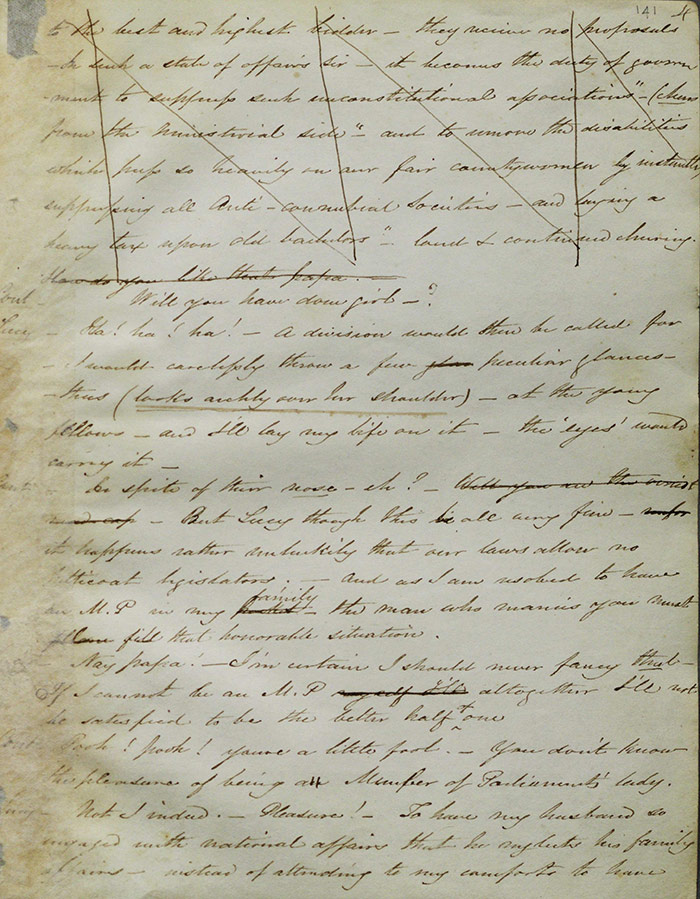

When Lucy imagines herself in parliament in the opening scene, her reference to ‘suppressing all anti-connubial societies’ among other fantasy legislative motions related to female empowerment is marked in pen for deletion (f.141). Other passages marked for removal along this line include Melton’s opinion that Bustle is an ‘epicure in children’s maids’ (f.144), marked in pencil this time. On (f.147), a little exchange between Bustle and a woman is struck through in pen, perhaps because of her vehement declaration that her husband ‘shall never come near me’ because she believes he has broken his marriage vows. Would this have troubled Kemble’s sense of propriety? It is difficult to know but the Adelphi management may have preferred to err on the side of caution, particularly in the early days of Kemble’s tenure. What the manuscript’s revisions may show, in fact, may well be the residual shadows of Colman’s much more stringent regime.

A short correction on (f.143) where ‘rascals’ is scored out and replaced by ‘electors’ might be the strongest evidence of corrections made with the Examiner’s office in mind. The retention of an anti-semitic slur at the foot of (f.152) shows us that somethings had not changed much since the eighteenth century.

Although Charles Kemble was not unduly troubled by this manuscript, it provides a very useful point of comparison between censorship regimes and, eighteenth and nineteenth theatrical representations of elections.

Further reading

The Adelphi Theatre Calendar: A Record of Dramatic Performances at a Leading Victorian Theatre

https://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/mgmt.htm

Ricorso: A Knowledge of Irish Literature

http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/c/Coyne_JS/life.htm

John Russell Stephens, ‘Coyne, Joseph Stirling (1803-1868)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6544, accessed 12 April 2019]

John Russell Stephens, The Censorship of English Drama 1824-1901 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980).