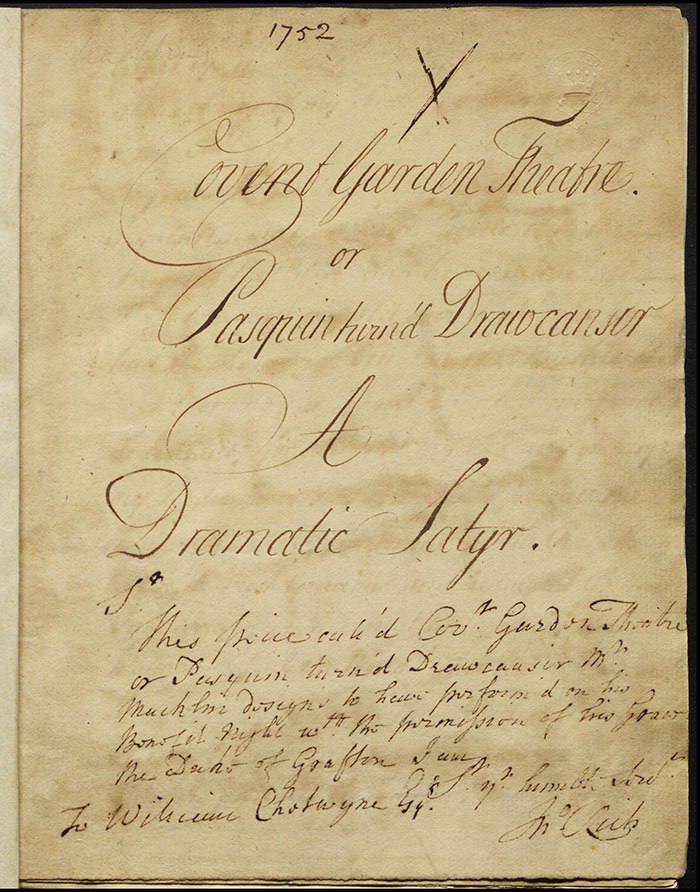

Covent Garden Theatre; or, Drawcansir turned Pasquin (1752) LA96

Author

Charles Macklin (1699?-1797)

One of the most well known Irish figures in London over the course of his remarkably long career, Macklin’s early years are a matter of some hazy speculation. After a spell at Trinity College Dublin as a ‘badgeman’, that is, a servant, he moved to England where he became a jobbing regional actor around 1720. An opportunity to take on some leading roles came about in Drury Lane in 1733 and Macklin’s career began to progress. He gained a certain degree of notoriety in 1734 when he was convicted of the manslaughter of a fellow actor after a backstage scuffle over a wig: an unexpected result of this was that he gained a taste for the law and the remainder of his career would see him involved in some high profile cases where he would represent himself.

When Macklin took on the role of Shylock in 1741, he interpreted the role in a radical fashion. Against much opposition from his colleagues and the public, Macklin consigned the buffoonish figure of recent years to obsolescence and portray a dynamic and pernicious moneylender that became his biggest success. ‘This is the Jew / That Shakespeare drew’, Pope was supposed to have commented when he saw it. It was a part he would play for almost fifty years.

While Macklin is best remembered for this career as an actor, he also penned a number of plays over the course of his career which achieved varying degrees of success. Undoubtedly, his comedies Love à la Mode (1759), The True-Born Irishman (1767), and The Man of the World (1781) were his most successful plays, registering both critical and commercial success. His other known works are Henry VII; or, The Popish Impostor (1746); A Will and No Will (1746); The New Play Criticiz’d (1746); The Fortune Hunters (1748); an adaptation of John Ford’s The Lover’s Melancholy (1748); Covent Garden Theatre (1752); and, The Married Libertine (1761).

Macklin led a rich and varied life. He spent time in Dublin, at one stage almost setting up a theatre there in collaboration with Spranger Barry, the Irish actor. He also established a ‘School for Oratory’ in London in 1754 but this was not a success. In later life he was involved with the Benevolent Society of St Patrick, ostensibly a charity but equally, if not more importantly, a networking forum for ambitious and patriotically inclined Irish in London. Always paranoid that publishing his plays would lead to him missing out on performance royalties, Macklin resisted calls to publish his plays for a long time but an edition by subscription of Love à la Mode and The Man of the World was finally published by fellow Irish dramatist Arthur Murphy in 1793 for Macklin’s benefit. An impressive £1582 was raised by a lengthy subscriber list of people from the worlds of politics, fashion, and politics, an indication of the renown in which Macklin was held. He died in 1797.

Plot

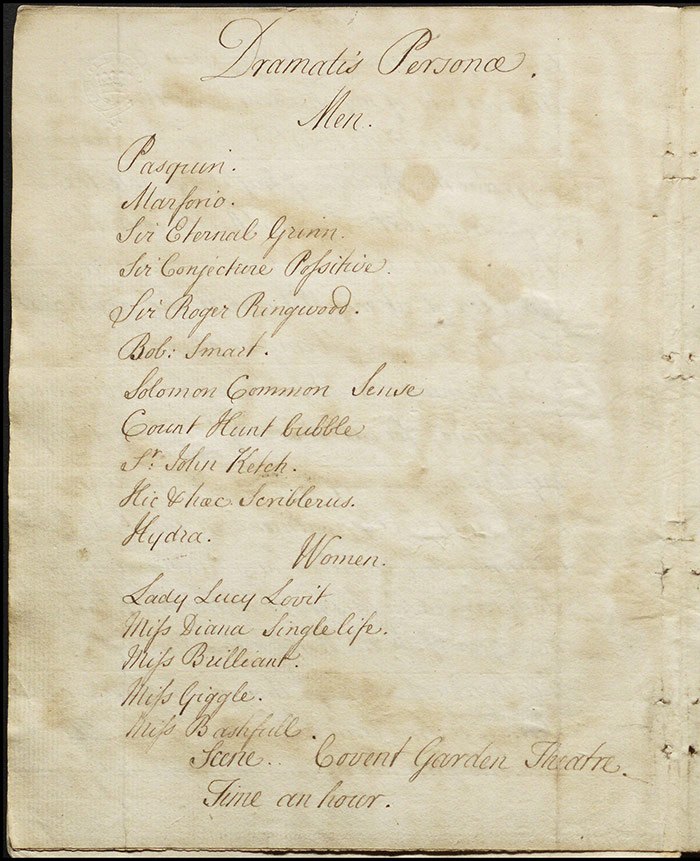

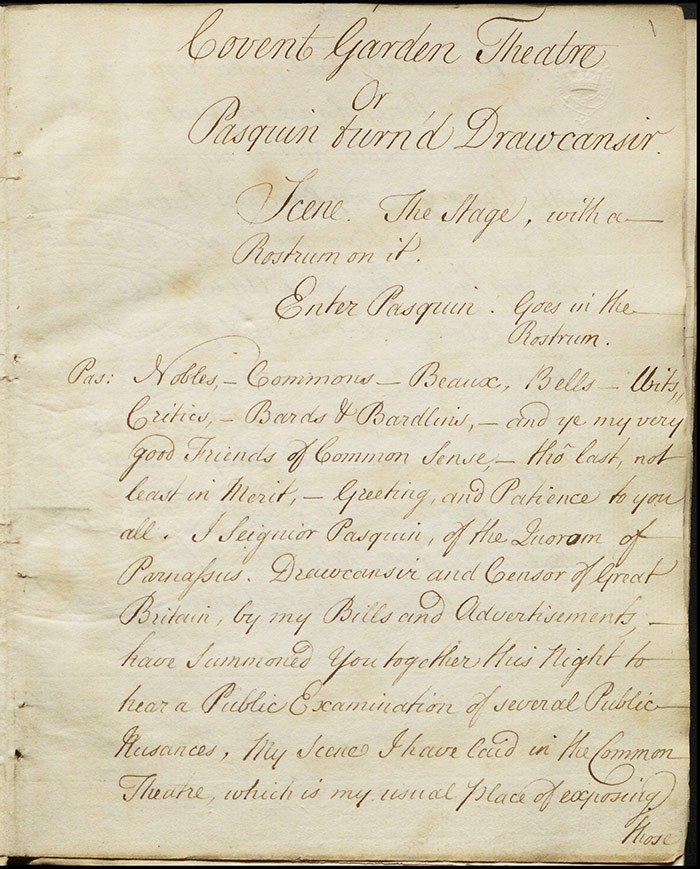

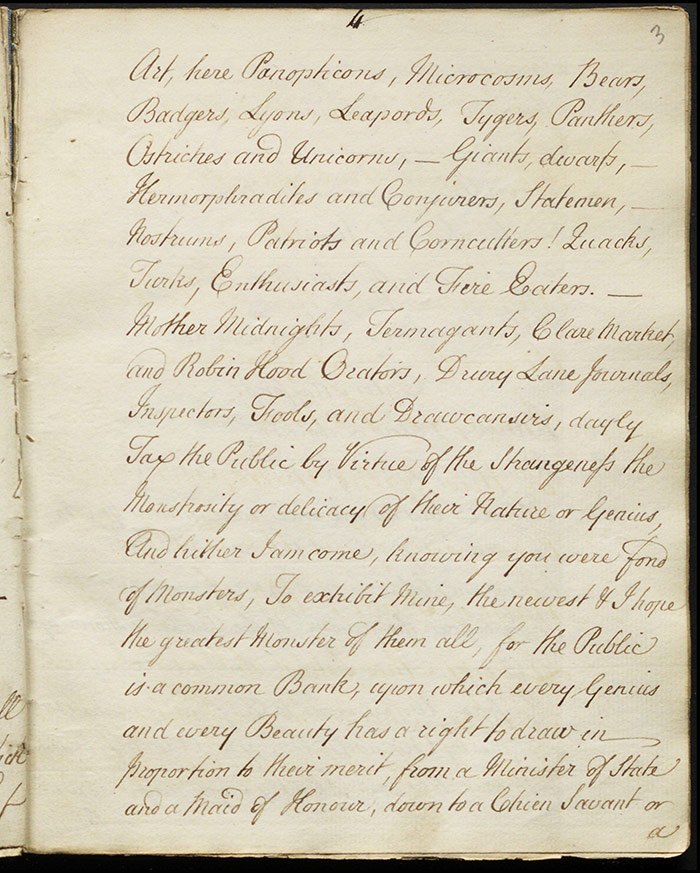

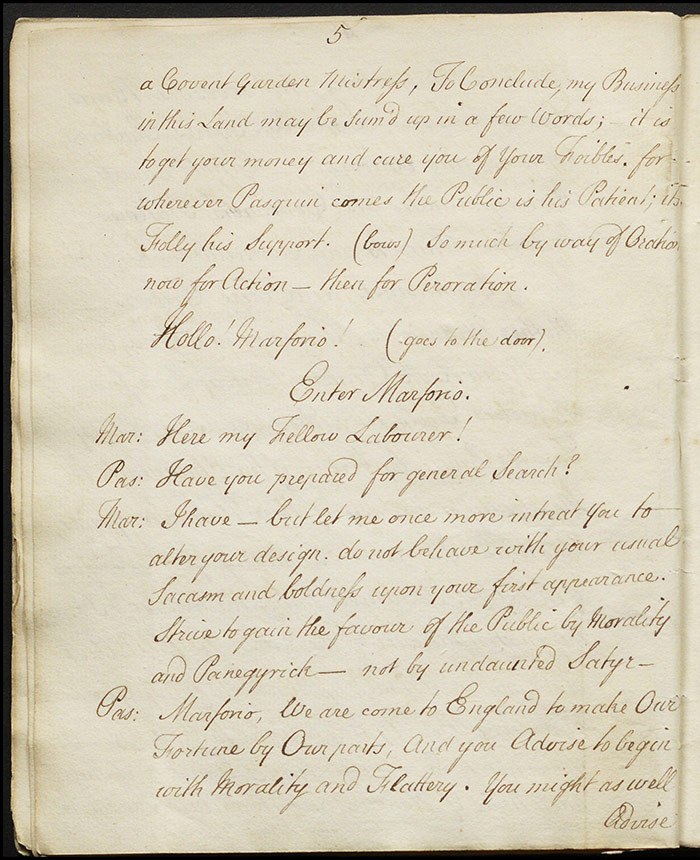

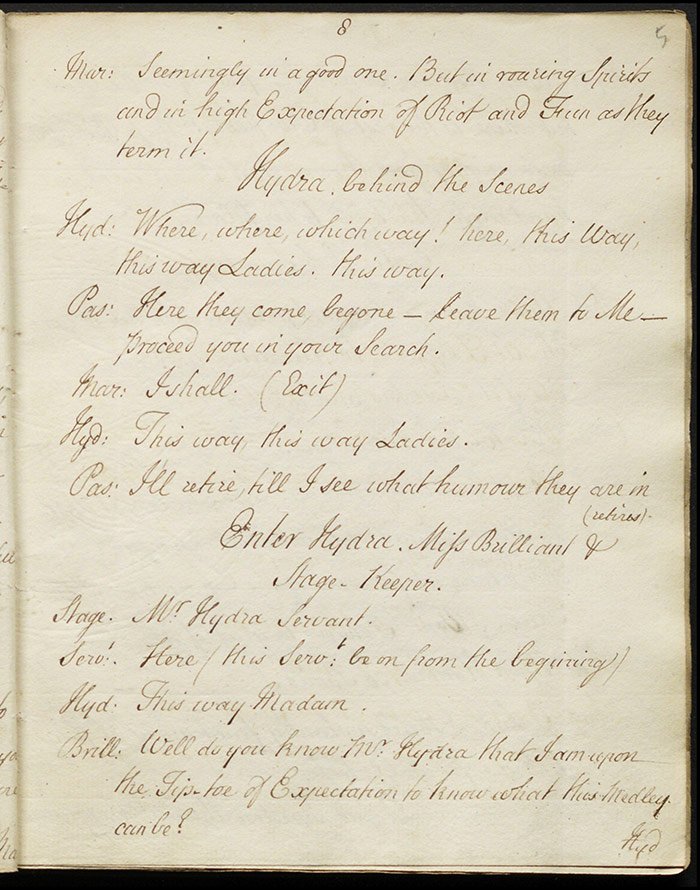

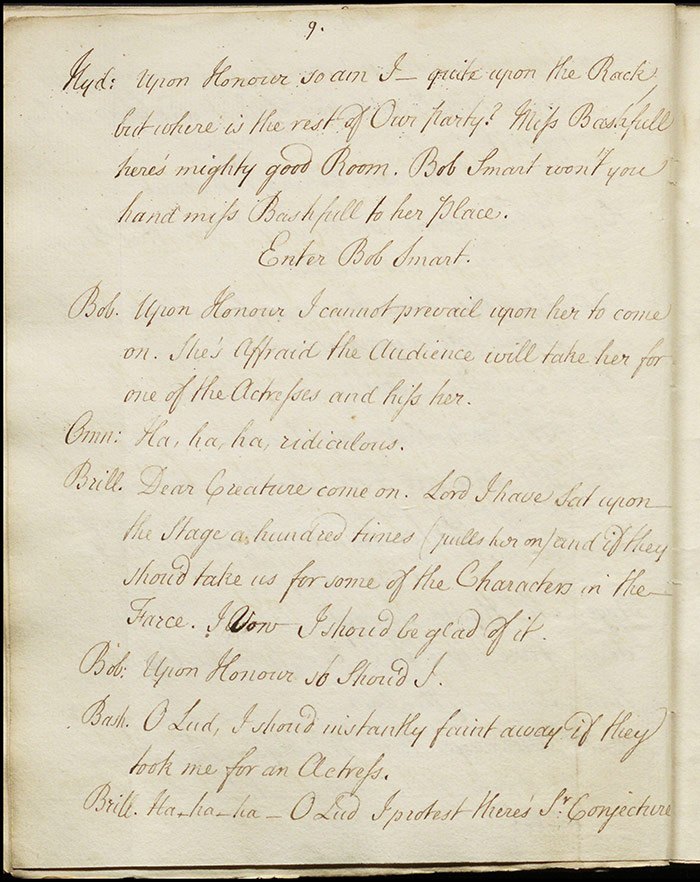

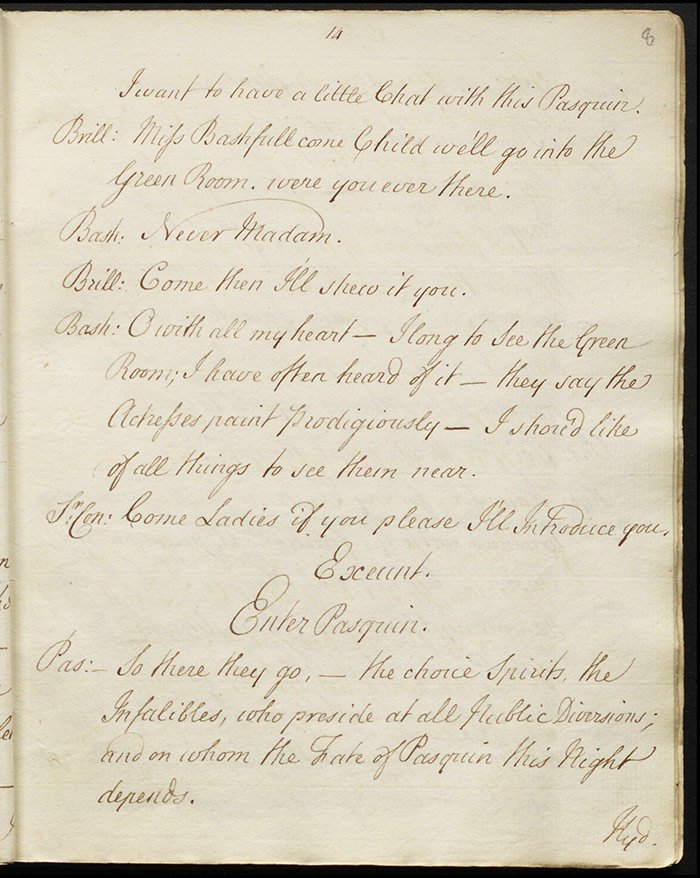

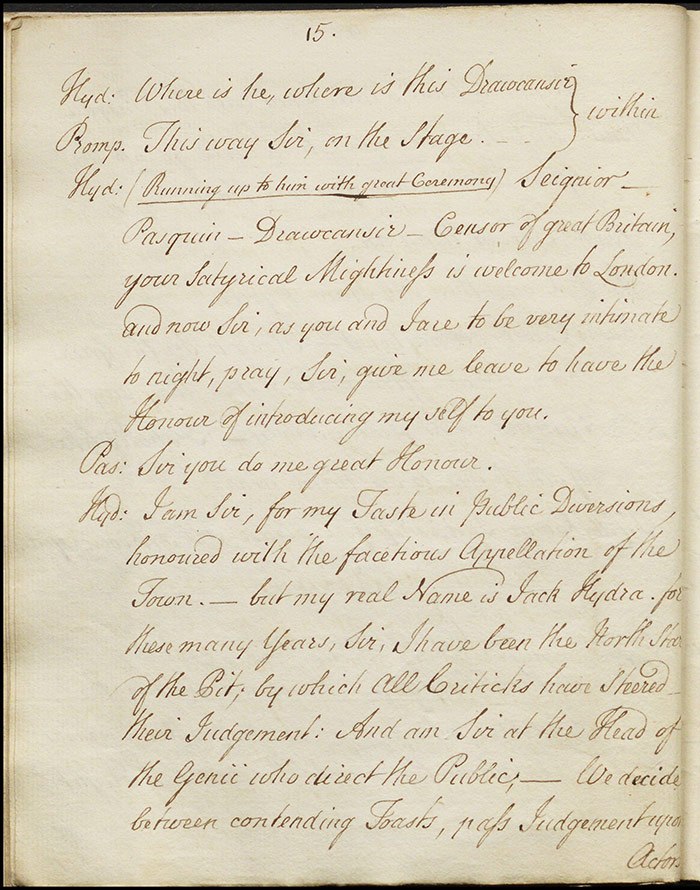

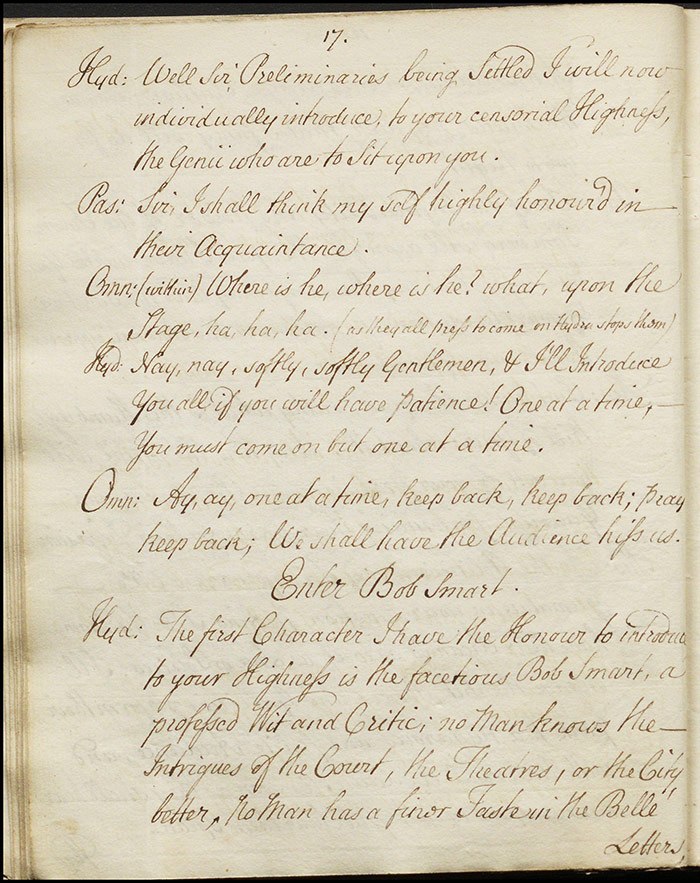

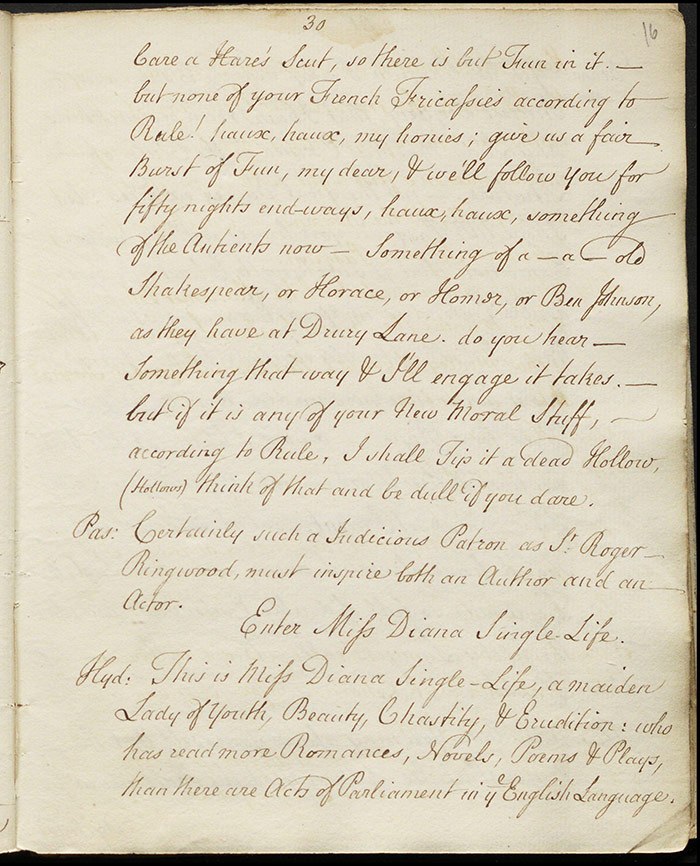

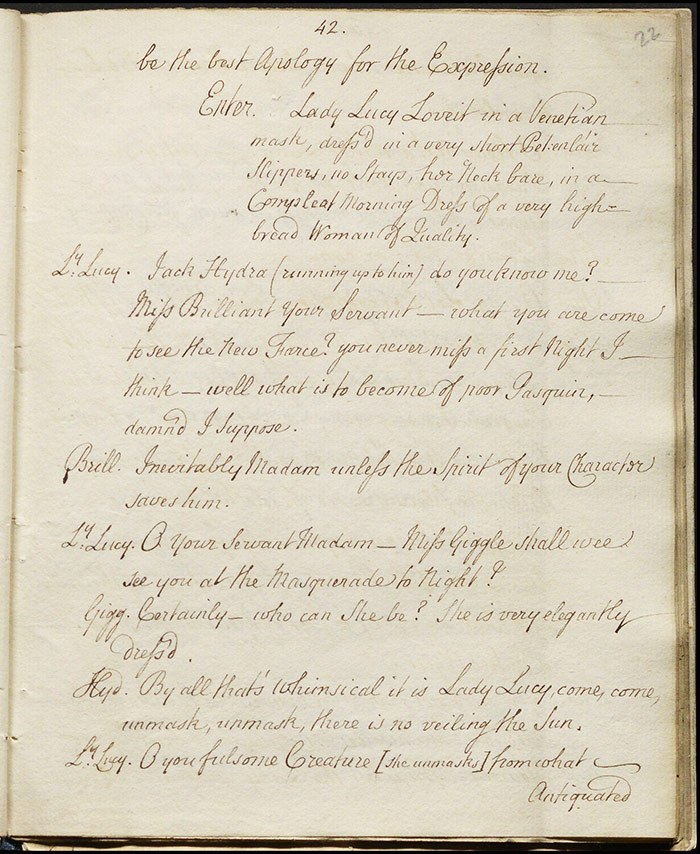

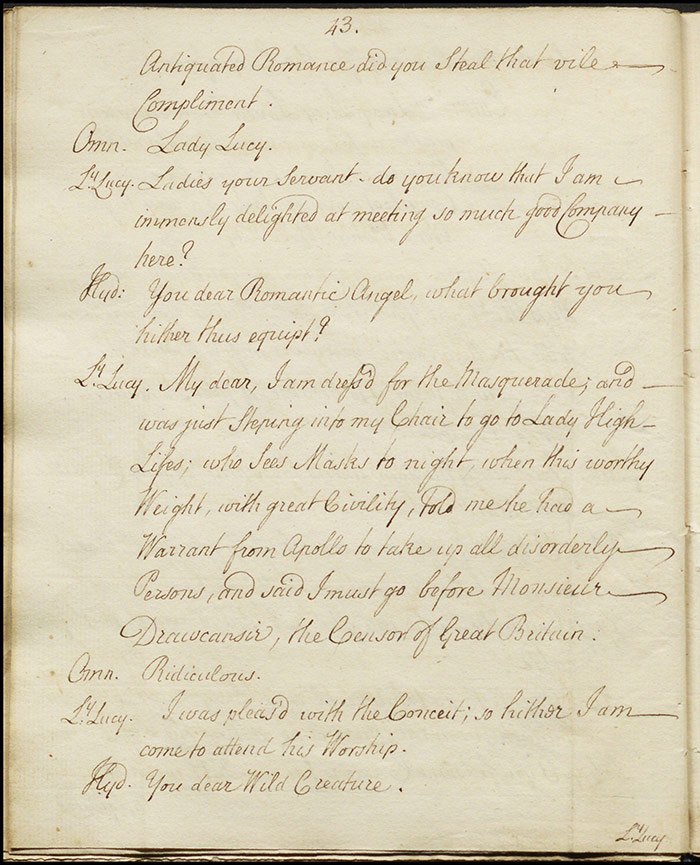

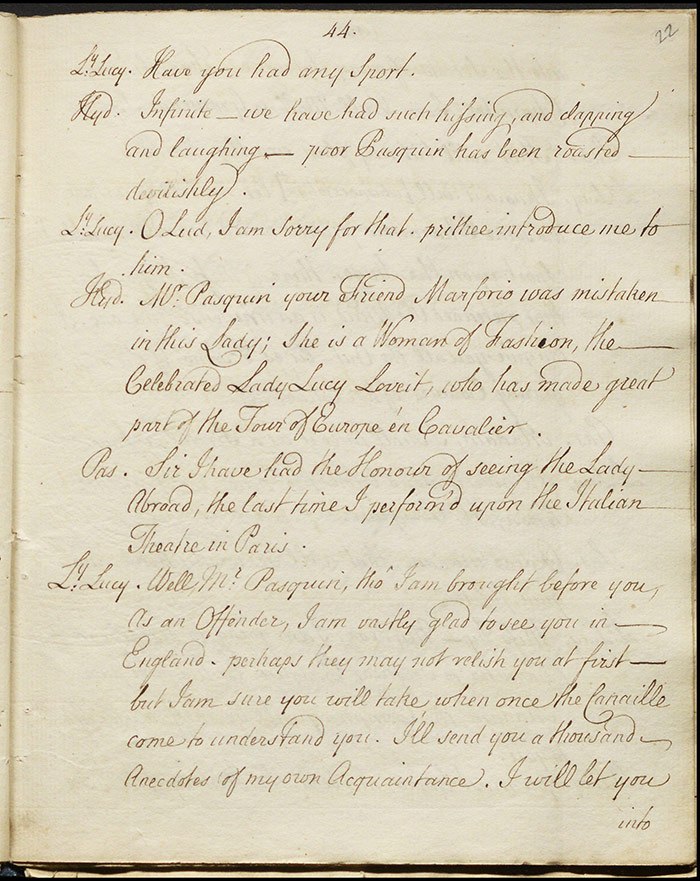

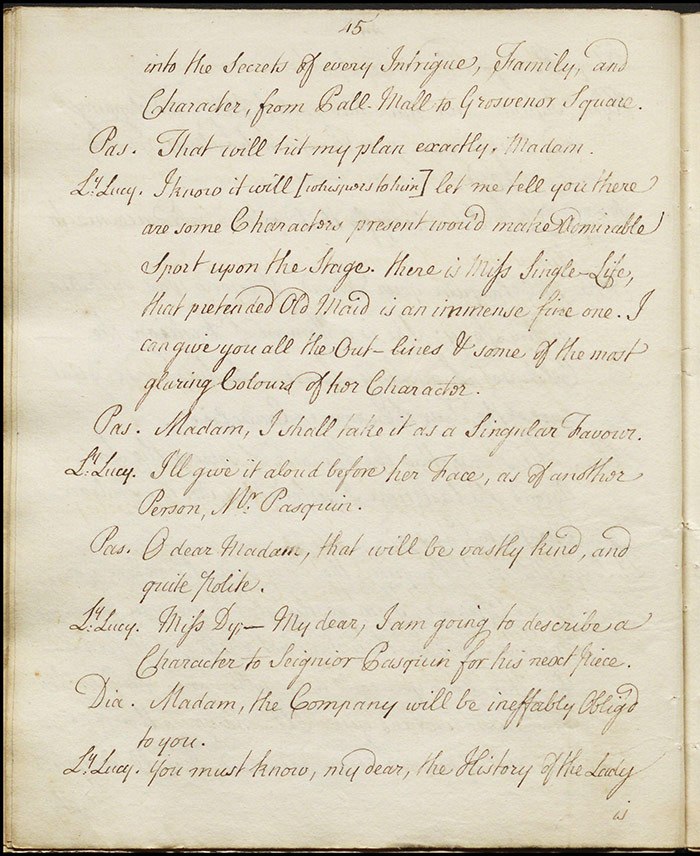

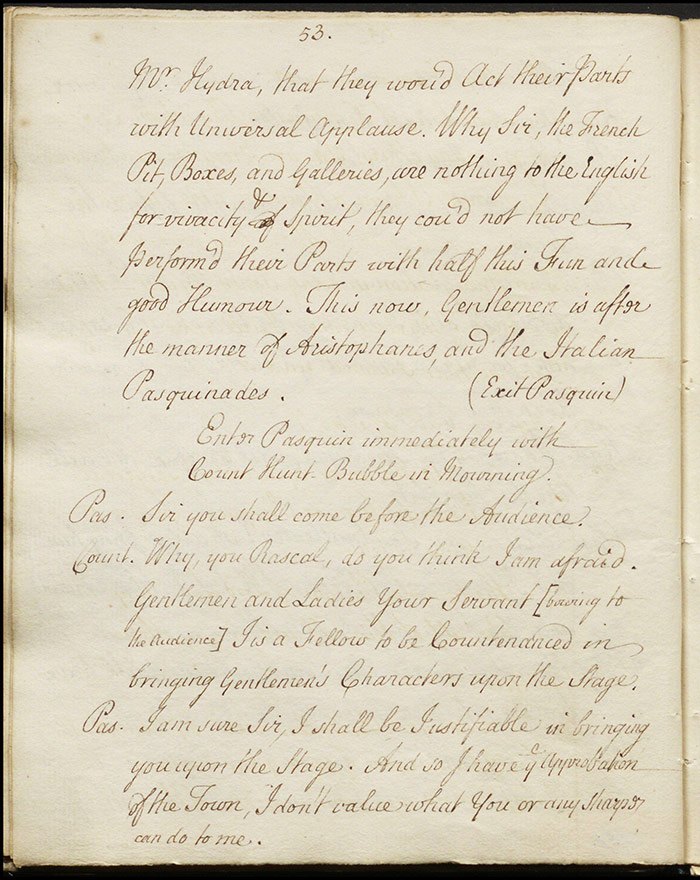

The plot of the two-act farce Covent Garden Theatre is slight. Pasquin, a self-appointed Drawcansir or Censor of the nation, surveys and ridicules a number of characters, types who represent the foibles of London’s modern life. He is assisted in this task by Marforio: both Pasquin and Marforio are names taken from the ‘talking statues’ of ancient Rome where satirical squibs would be placed at night by irreverent citizens.

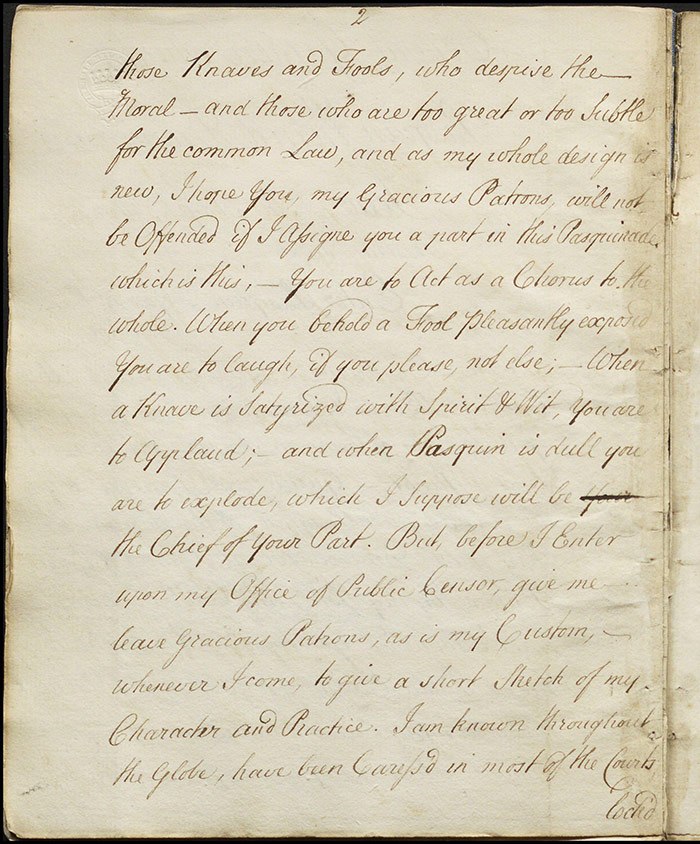

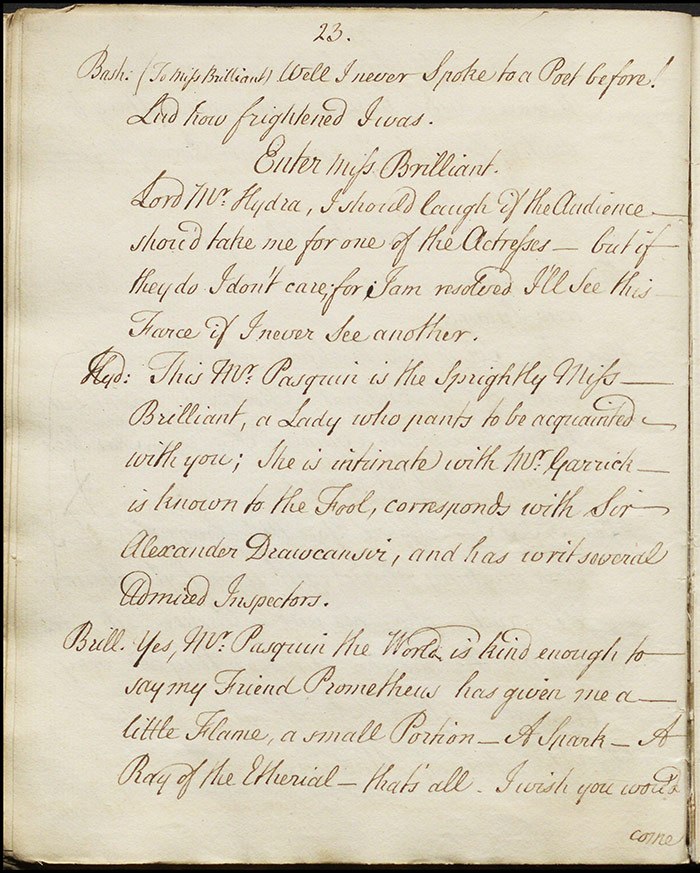

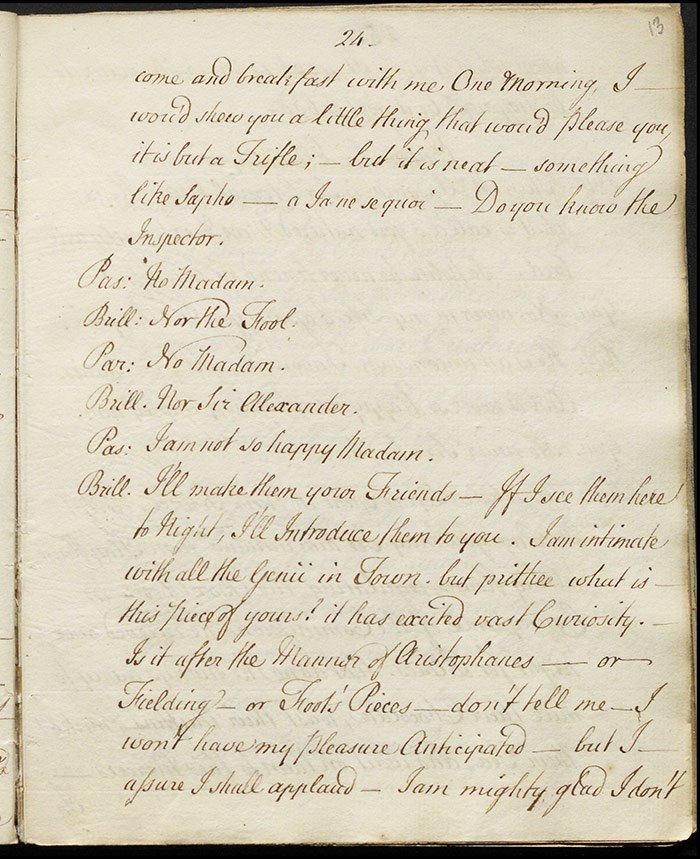

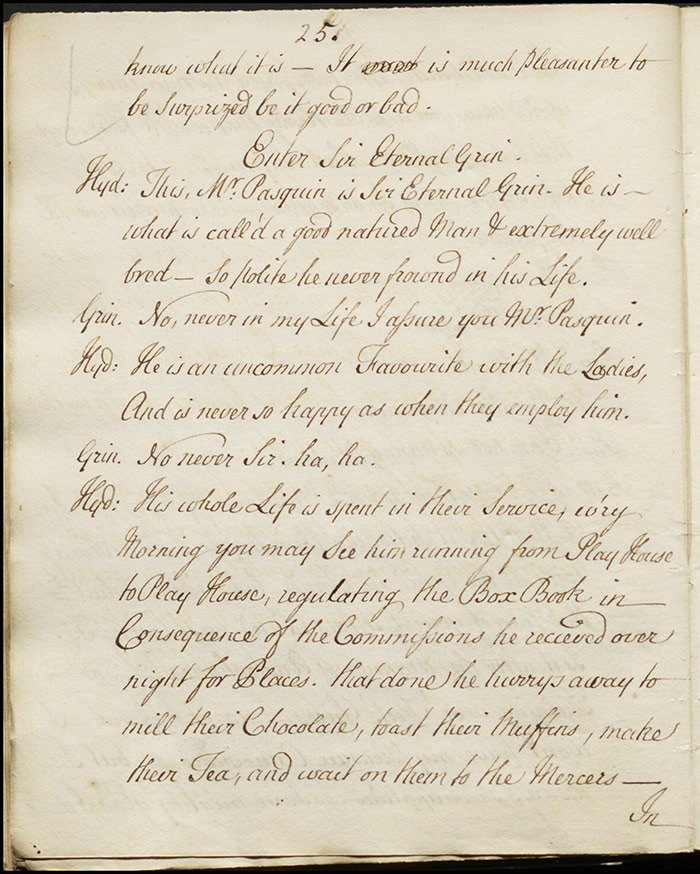

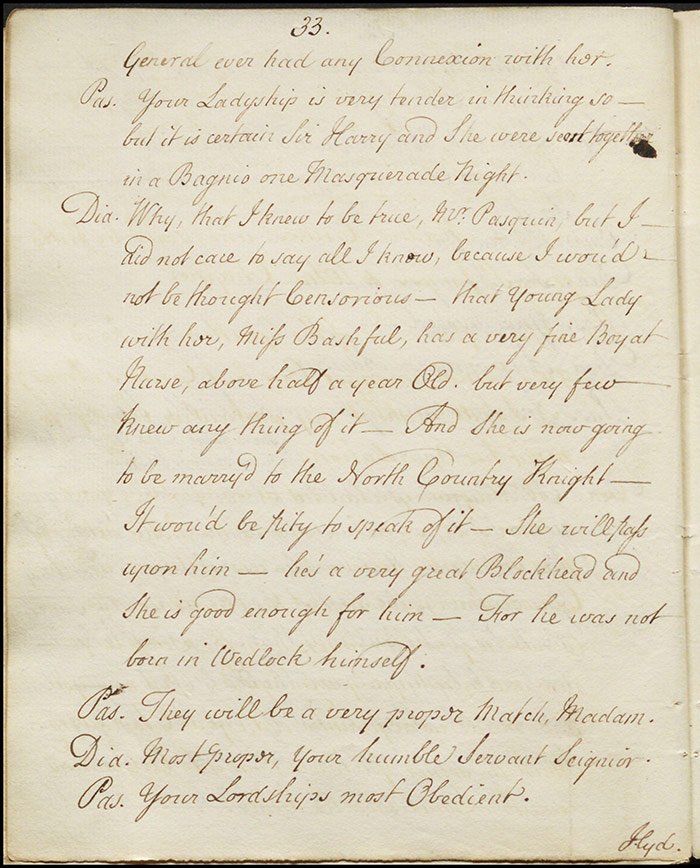

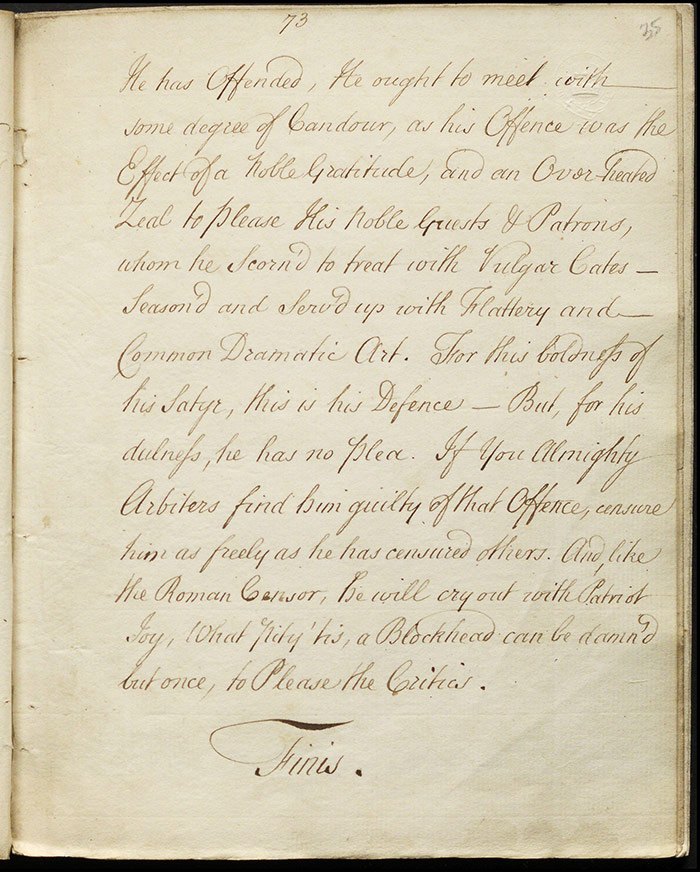

Characters who appear on stage for gentle ridicule include Miss Brilliant, Bob Smart, Sir Conjecture Positive, Sir Eternal Grin, Sir Roger Ringwood, Miss Diane Single-Life, and Lady Lucy Loveit. Sir Solomon Common Sense provides a foil to their collective inanity. There are a number of references to current topical events and people in the piece. The farce concludes with the customary obeisant gesture to the audience’s good character and taste and an affirmation of the dangers of gambling to public morality inspired by Fielding’s Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase in Robbers (1751).

Literary debts are also owed to George Villiers’s The Rehearsal (1671), Henry Fielding’s play Pasquin (1736), and his periodical Covent Garden Journal (1752).

Performance, publication and reception

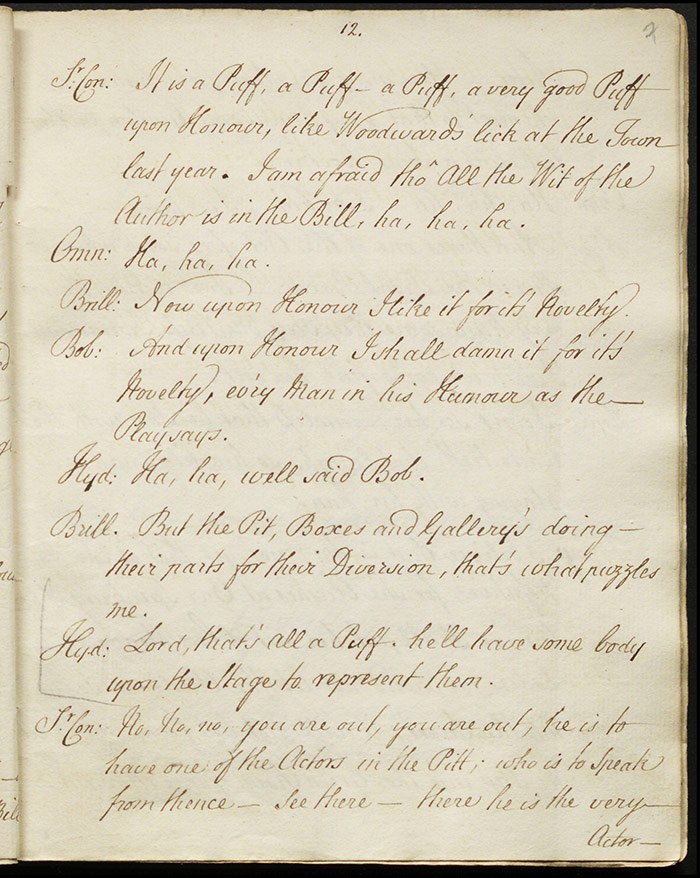

Covent Garden Theatre; or, Pasquin Turn’d Drawcansir was performed on 8 April 1752 at the eponymous theatre. The two-act farce was offered as an afterpiece to Colley Cibber’s The Provok’d Husband and was a benefit performance for Macklin who most likely played the lead, Pasquin. The farce was never repeated. While there are certainly issues with the quality of the drama, one might also observe that its failure was to a degree assured, given the extent of the censorship evidenced in the Larpent manuscript. As a piece heavily dependent on humorous references to contemporary people and events, their exclusion meant that there was little left for an audience to enjoy.

There is only one account of the production which appeared in Have at you All; or, The Drury-Lane Theatre, a periodical written by ‘Madam Roxana Termagant’, the penname of Bonnell Thornton. Thornton’s Drury-Lane Theatre (16 January – 9 April 1752) was specifically conceived in order to attack Fielding’s Covent-Garden Journal by parodying his style. Although A Condemnation, or (according to the Technical Term) DAMNATION of the Dramatick Satire, call’d PASQUIN turn’d DRAWCANSIR is ostensibly an attack on the play, it is clear that Thornton was quite sympathetic to Macklin’s efforts. For instance, one of the criticisms Termagant levels is that ‘[the piece] affronted a great part of the company, and obliged some very polite people in the boxes to decamp in a hurry, least their confusion of countenance should seem to betray a consciousness that they or their intimate acquaintance were aim’d at’ (No. 12, p. 283) which suggests that Macklin’s satire hit some of its marks.

Modern critics have paid little attention to Macklin’s plays other than Love à la Mode (1759), The True-born Irishman (1767), and The Man of the World (1781), and this farce is no exception. Esther M. Raushenbush offers the fullest treatment in a sympathetic article which provides a useful overview of the play. William M. Appleton, on the other hand, is less kind, calling it a ‘loosely-constructed, witless piece’ (95). More recently, Matthew Kinservik admits there is not much ‘in the way of comedy’ but argues that the play ‘reveals [Macklin’s] desire to write hard-hitting social satire’ (177).

Commentary

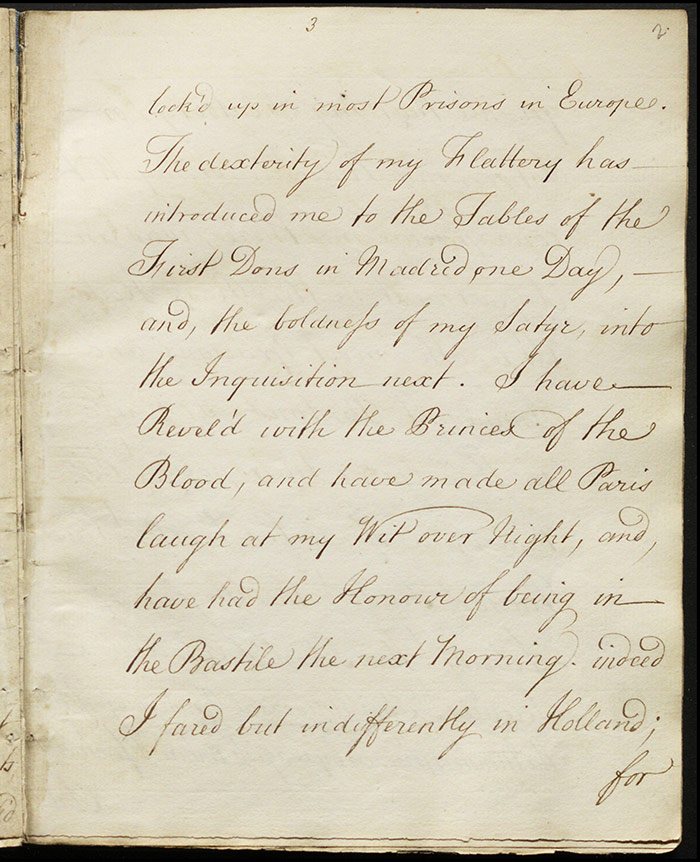

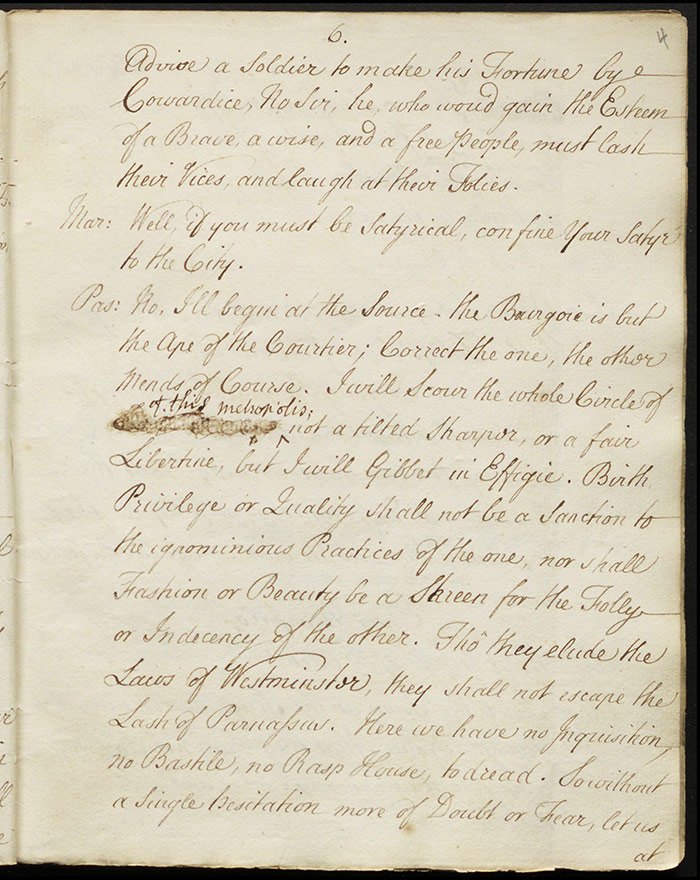

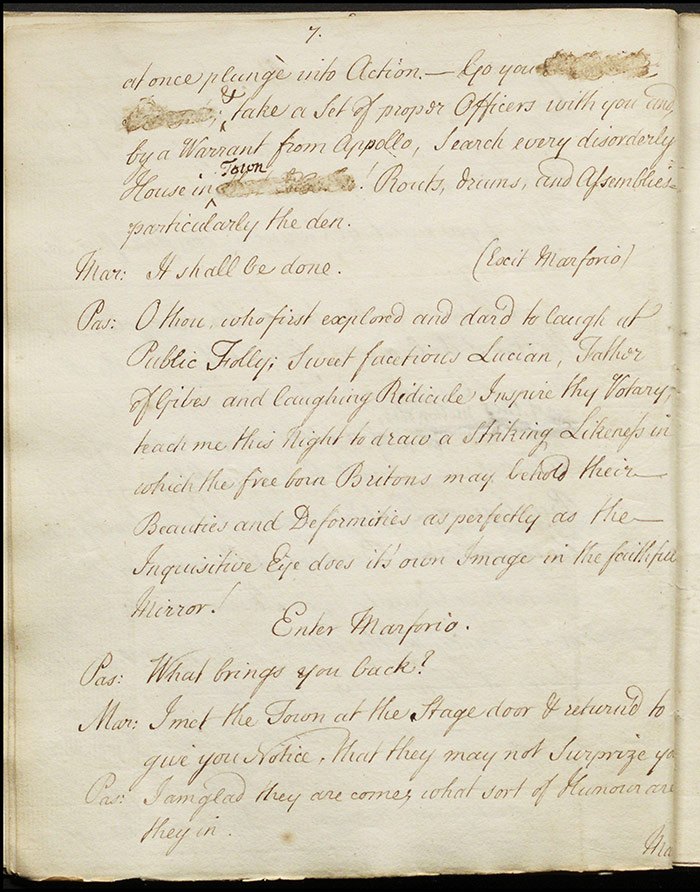

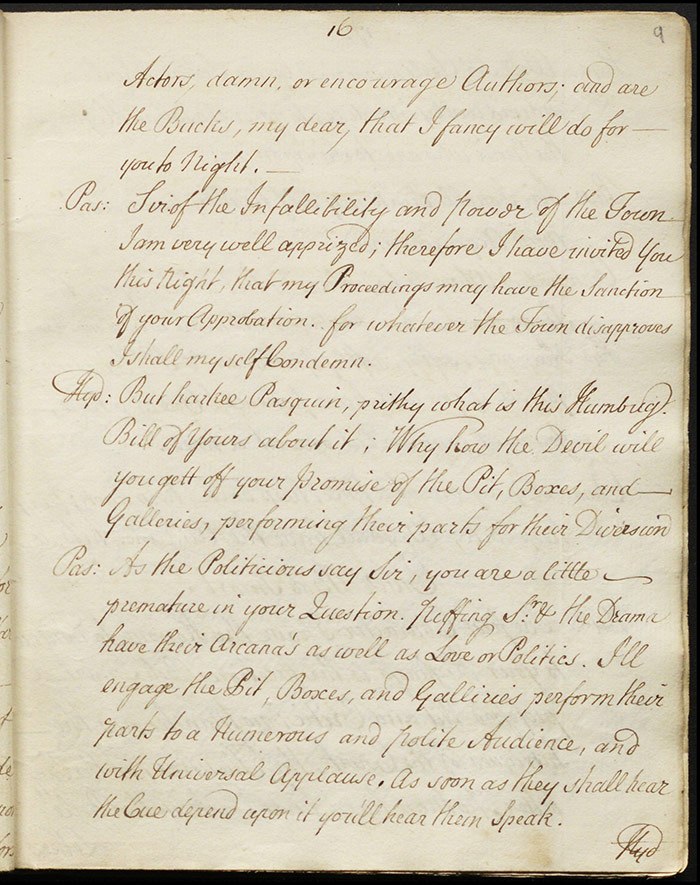

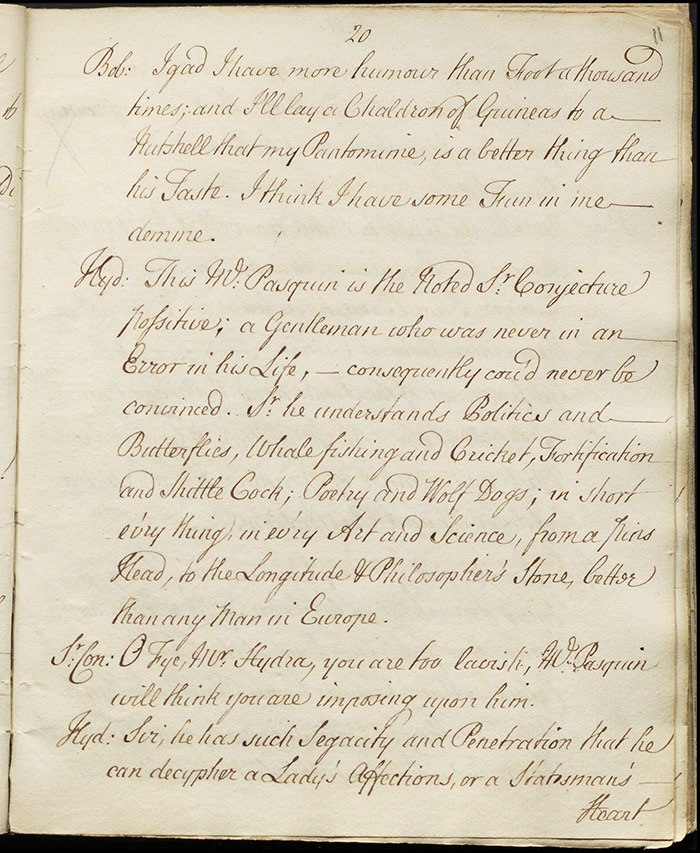

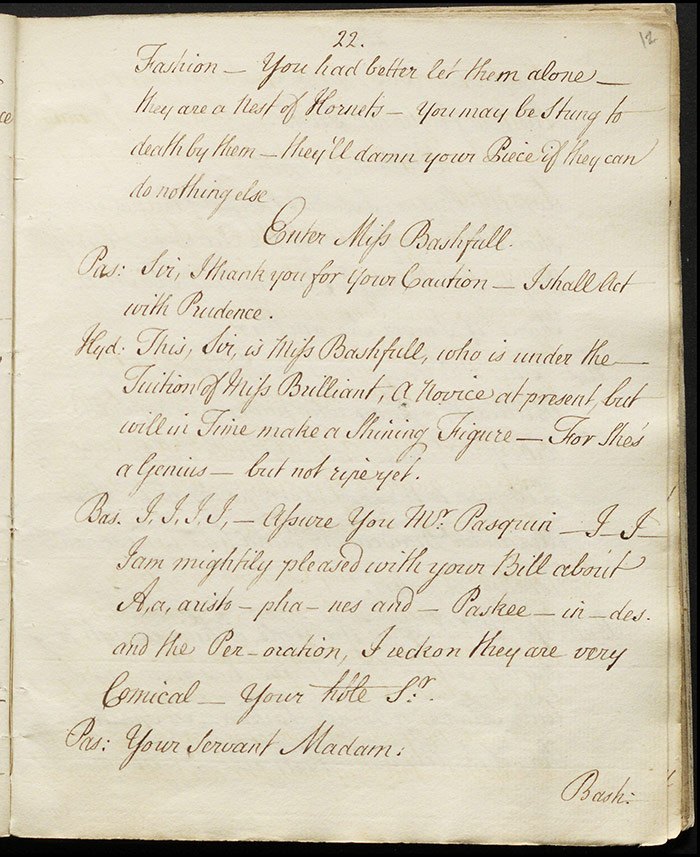

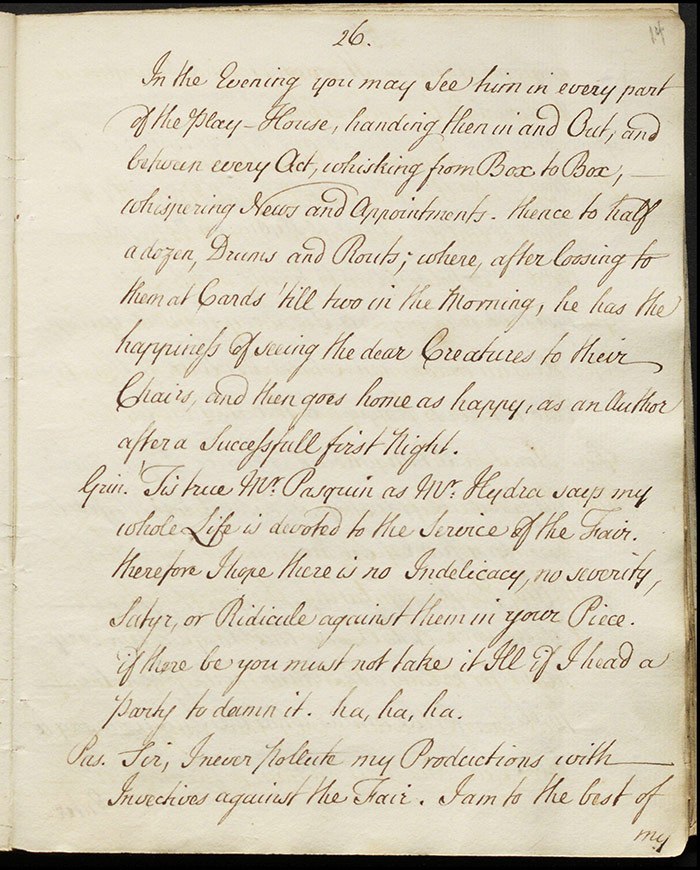

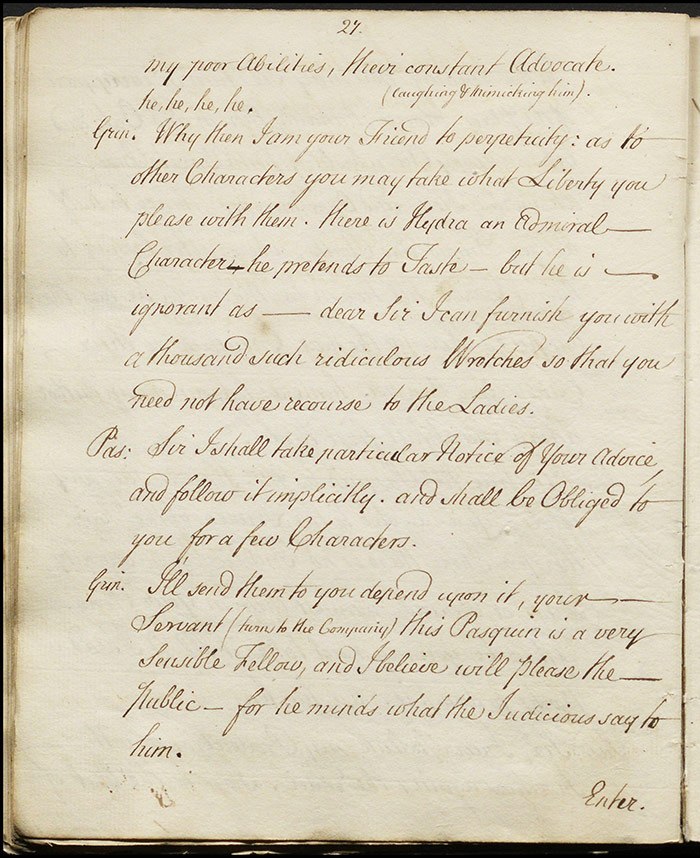

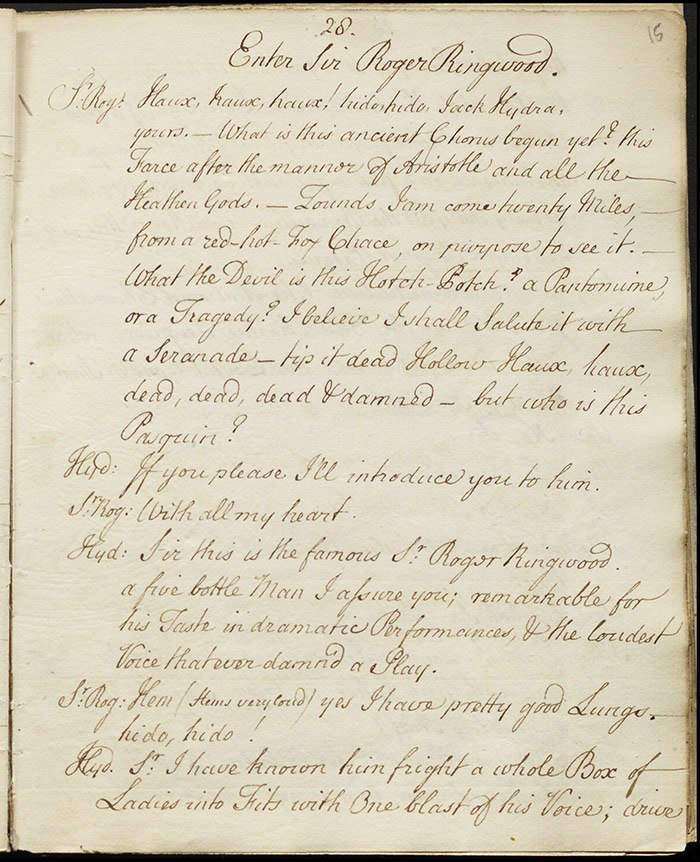

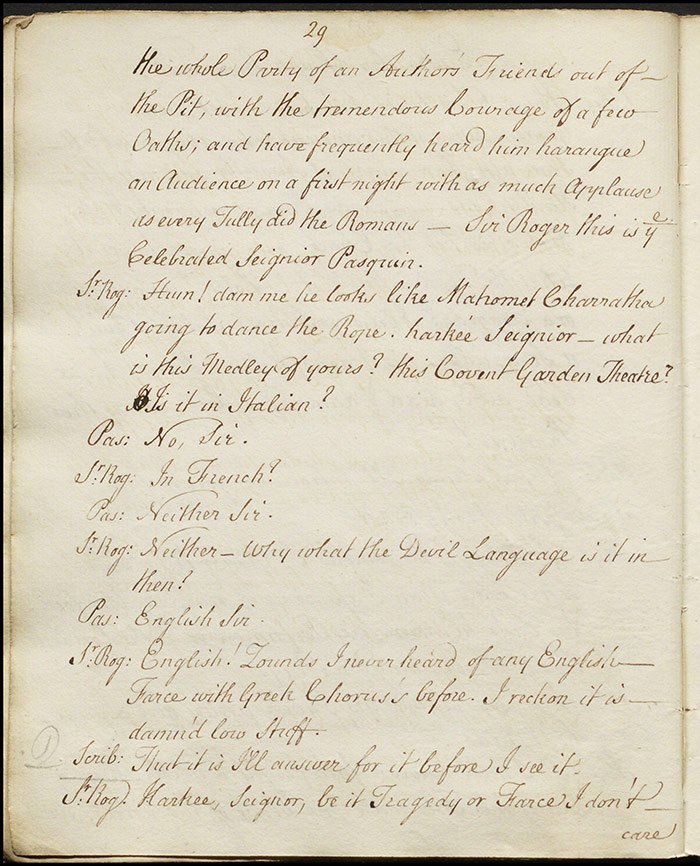

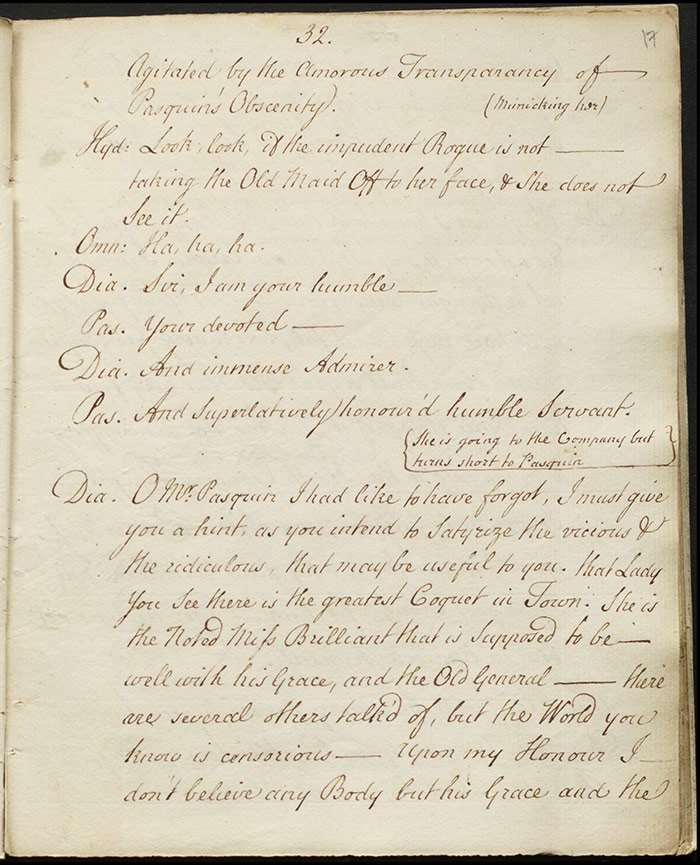

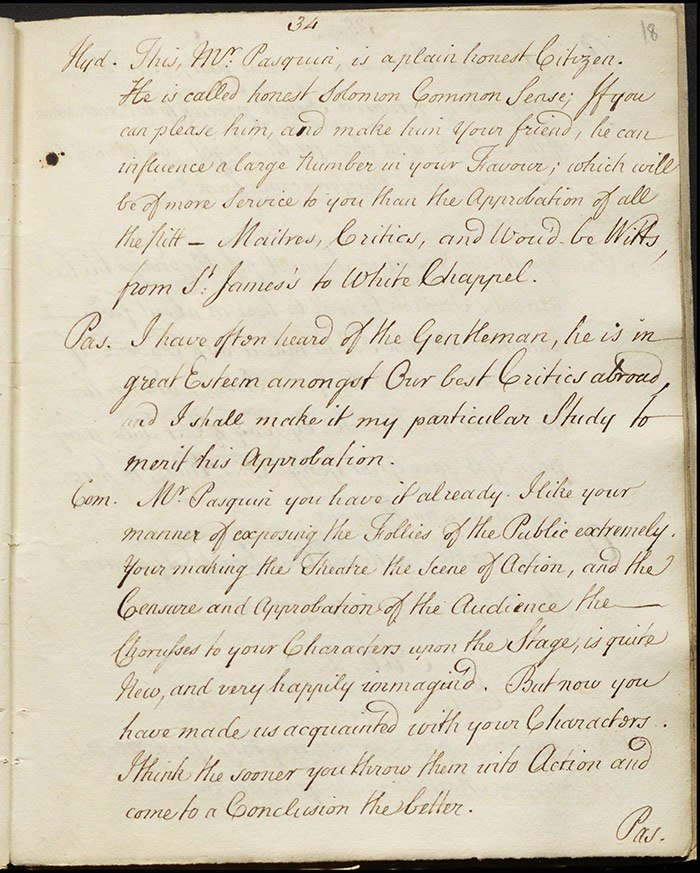

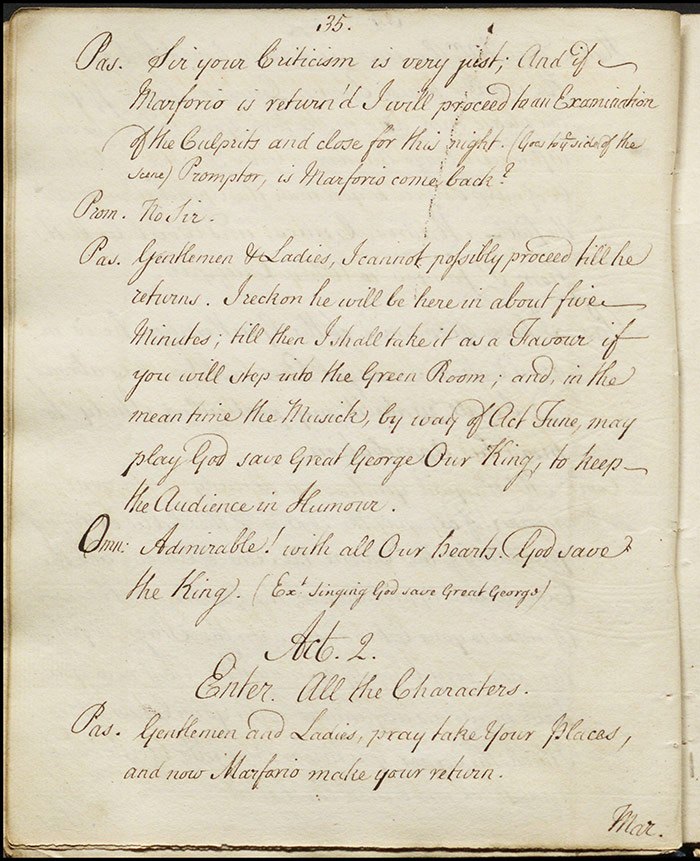

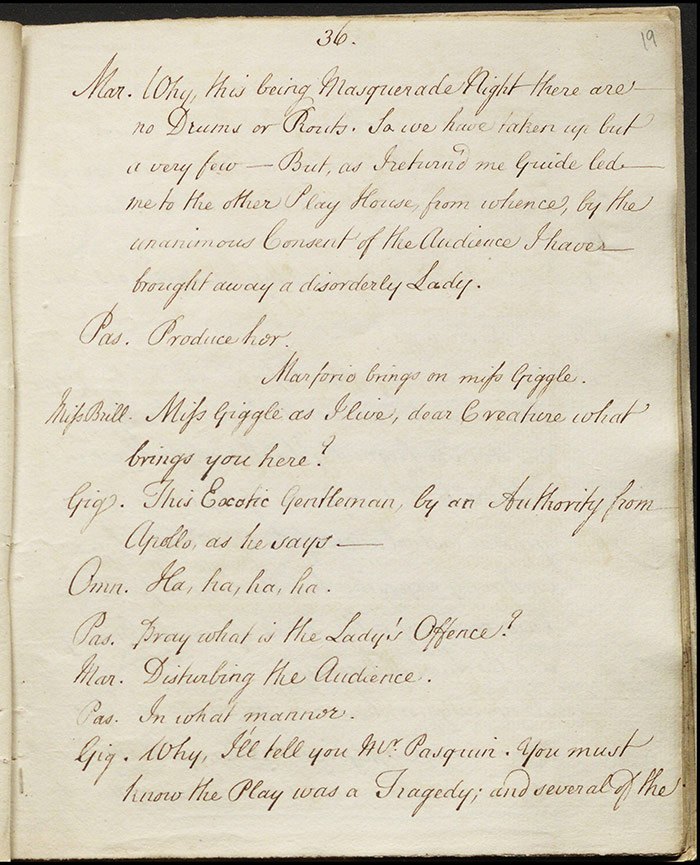

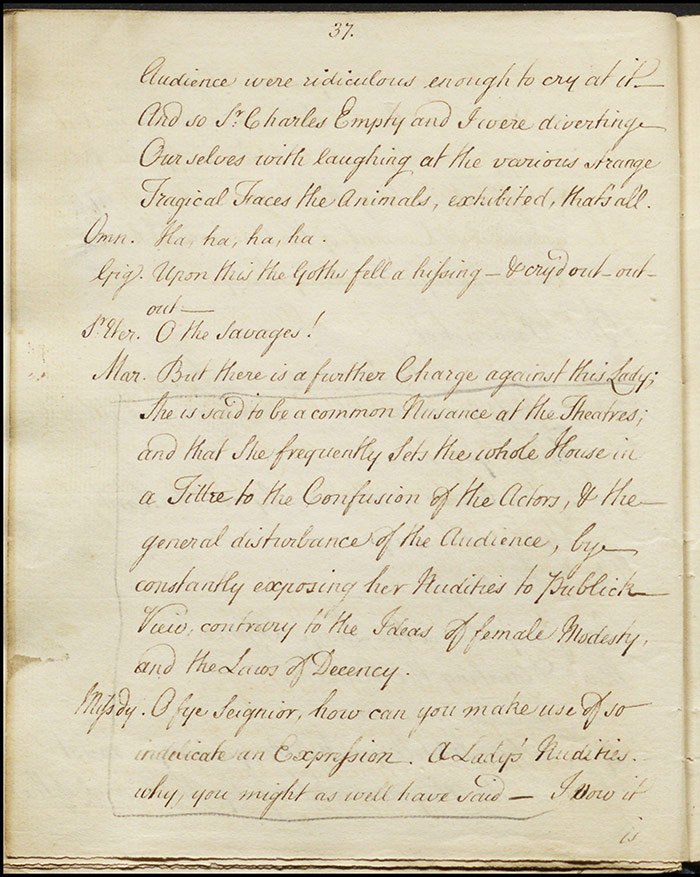

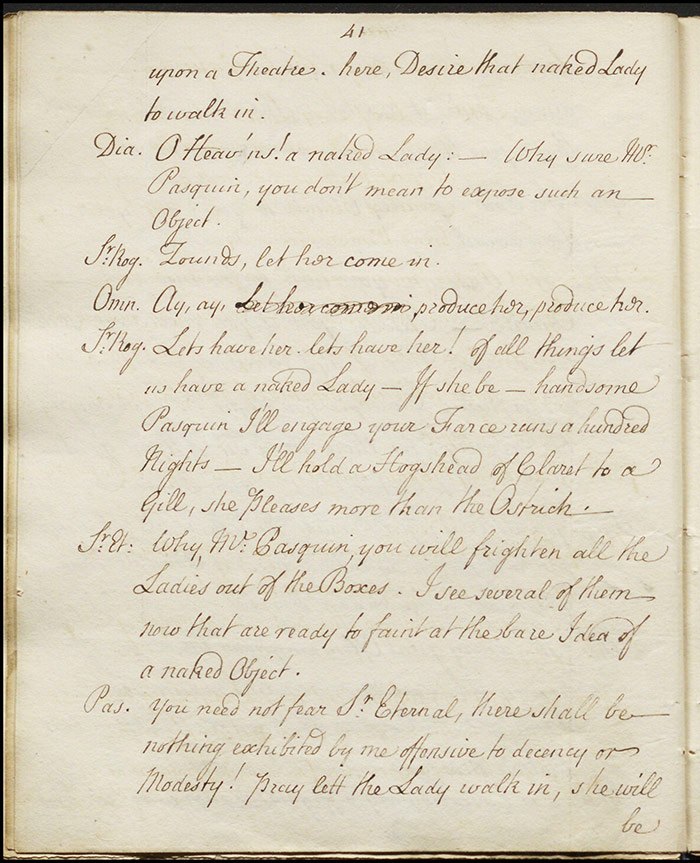

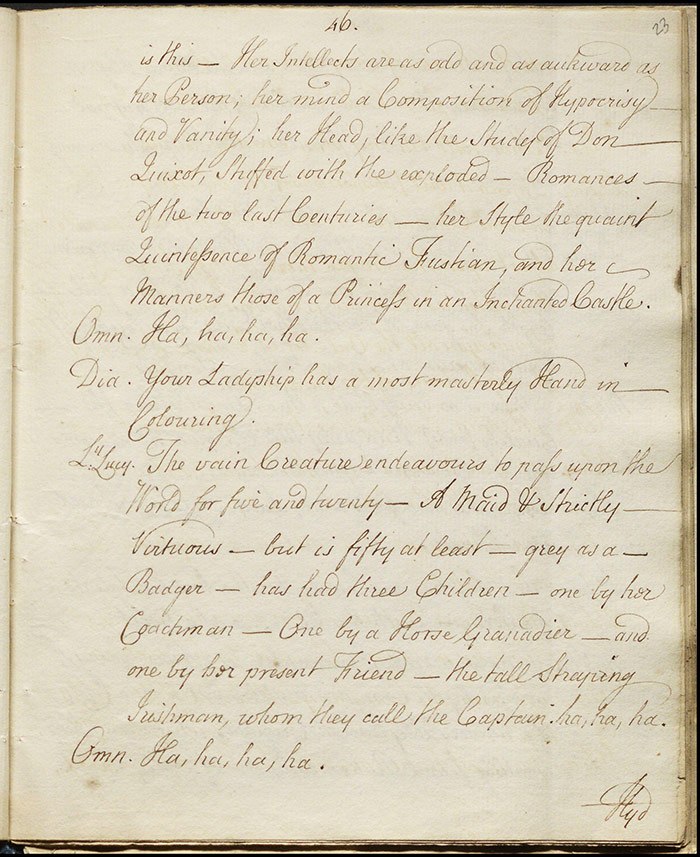

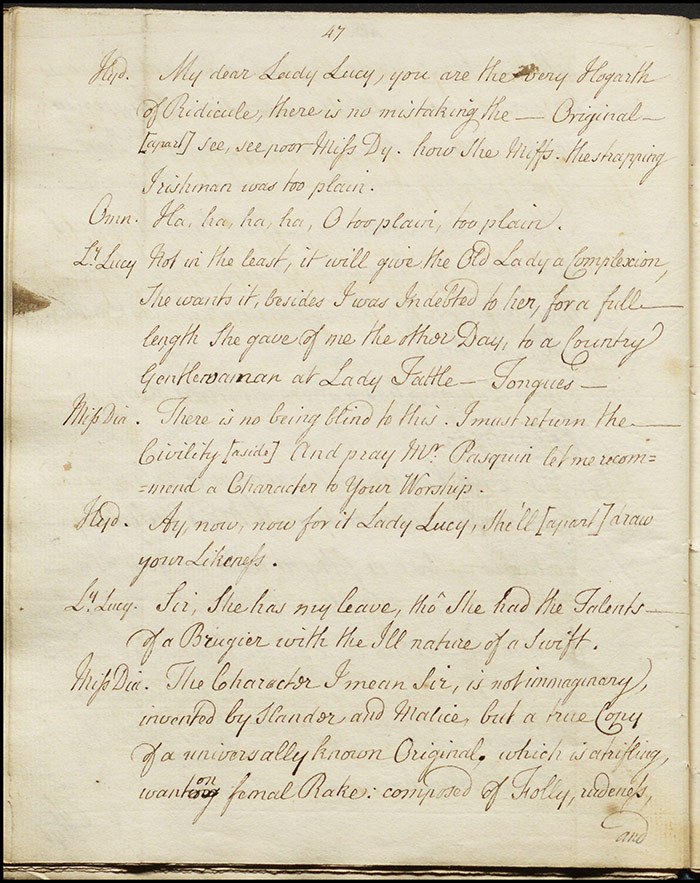

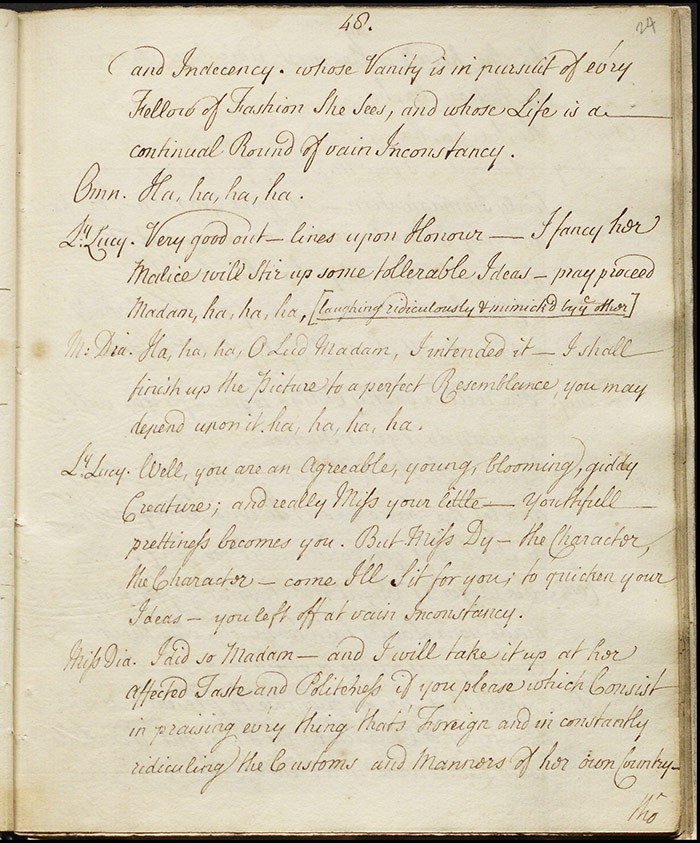

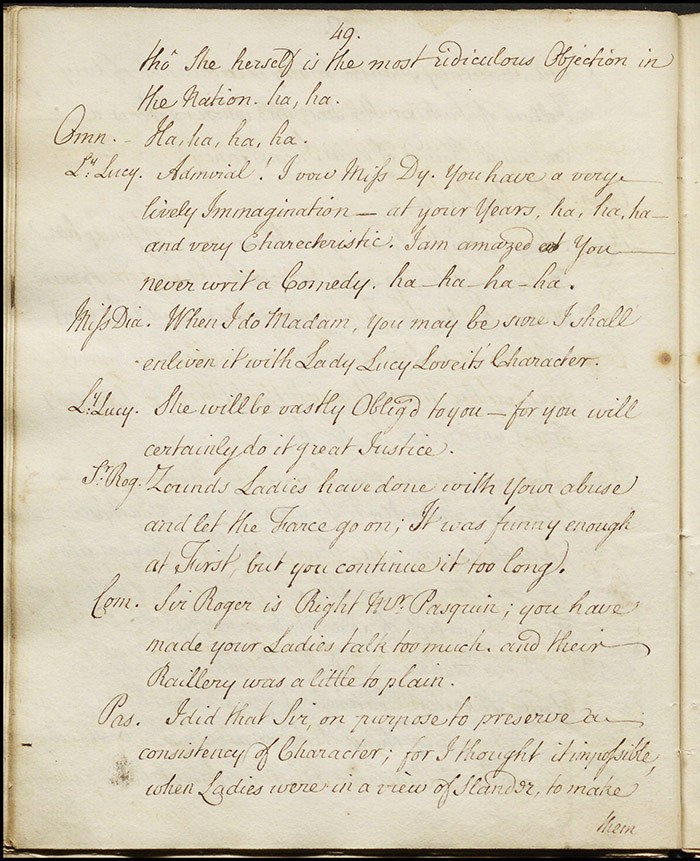

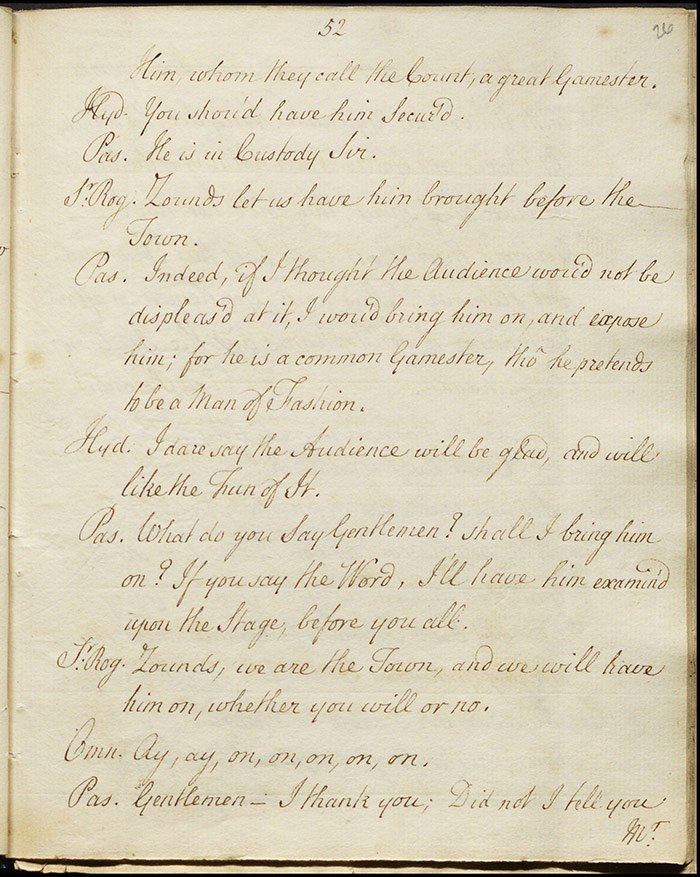

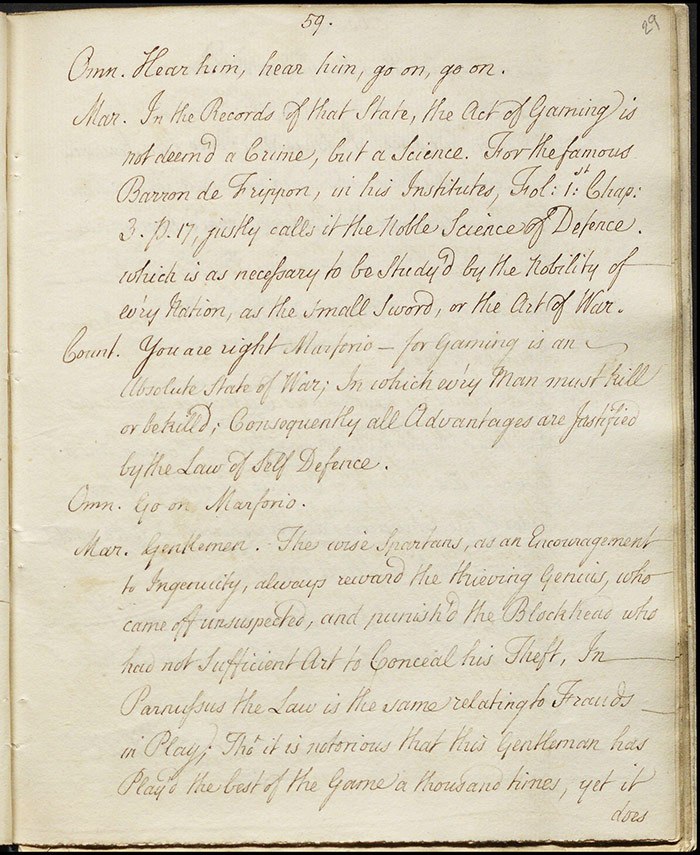

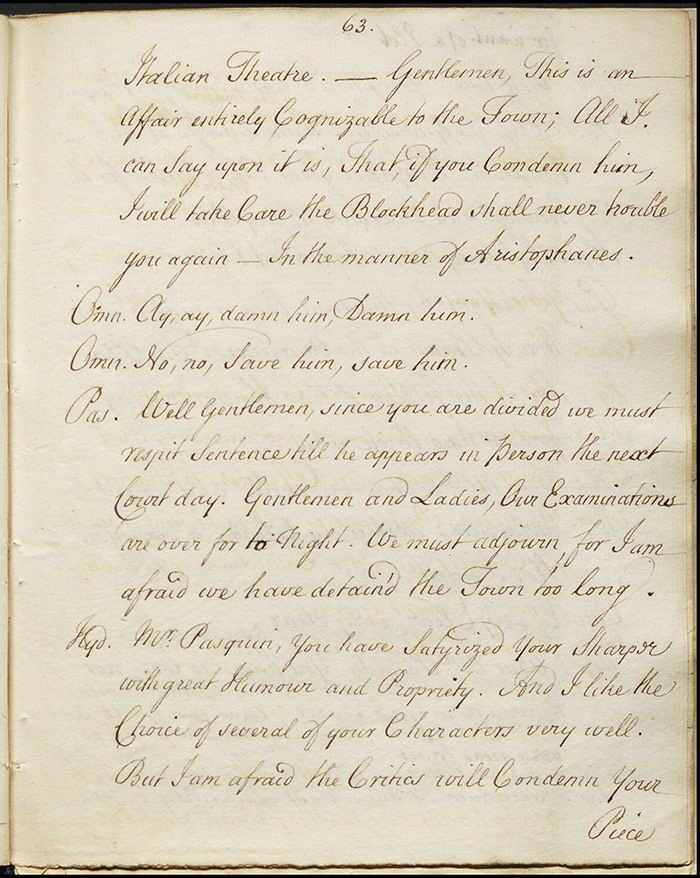

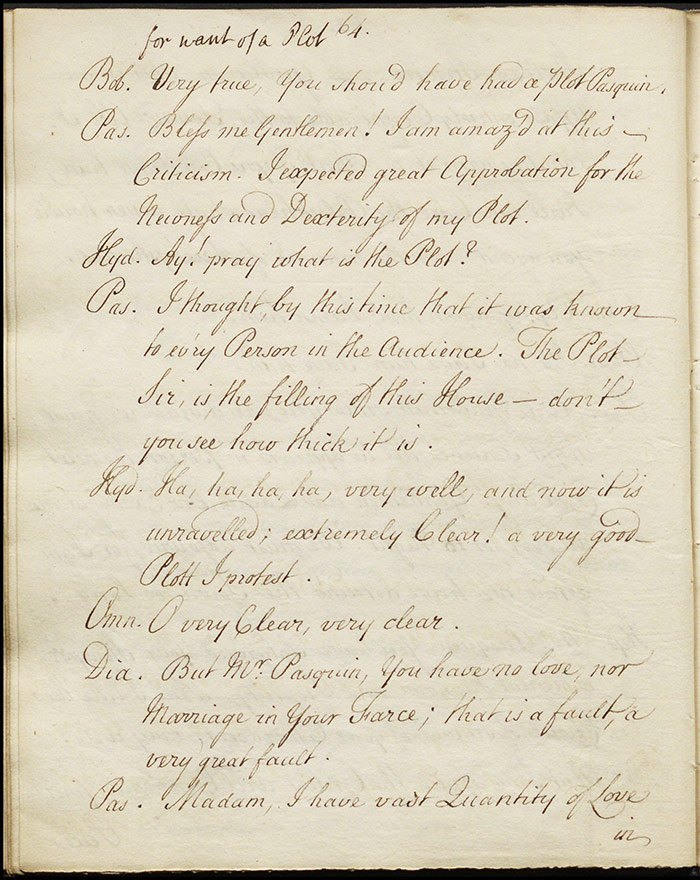

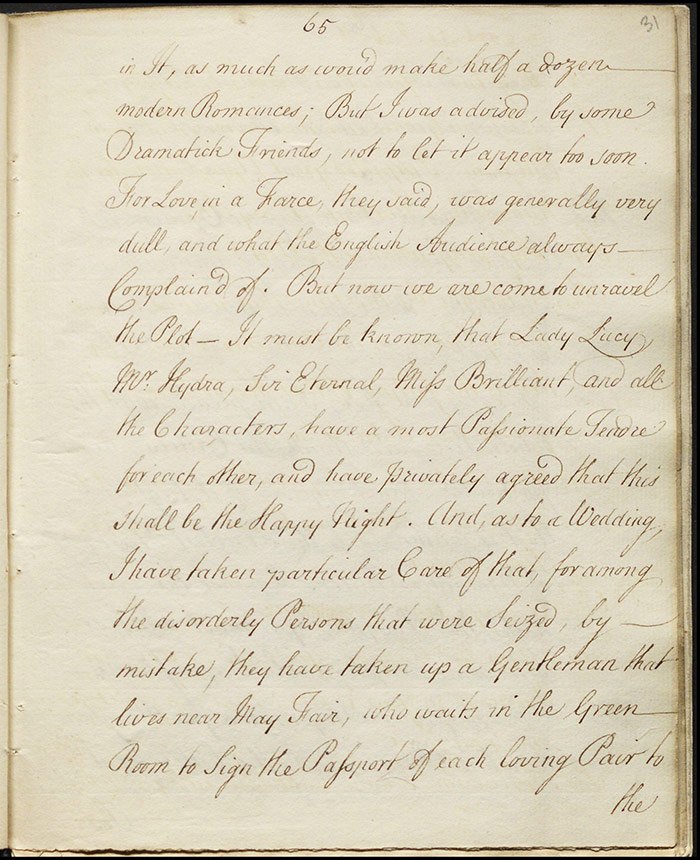

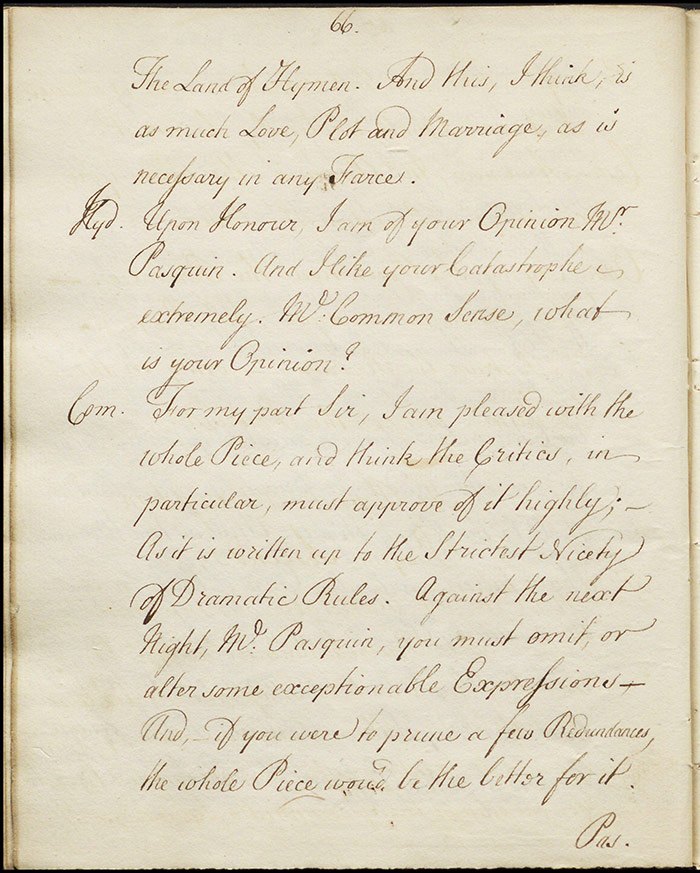

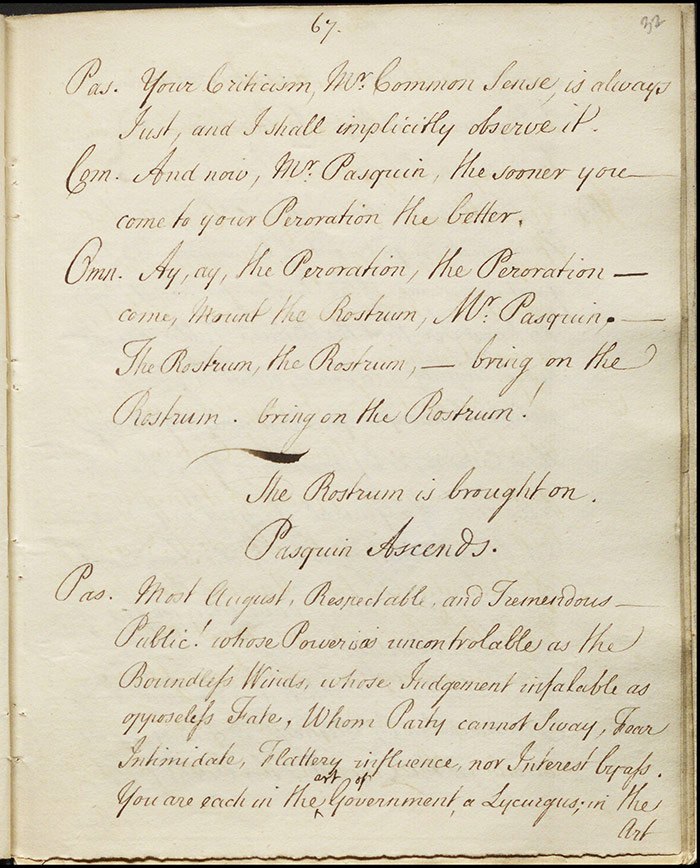

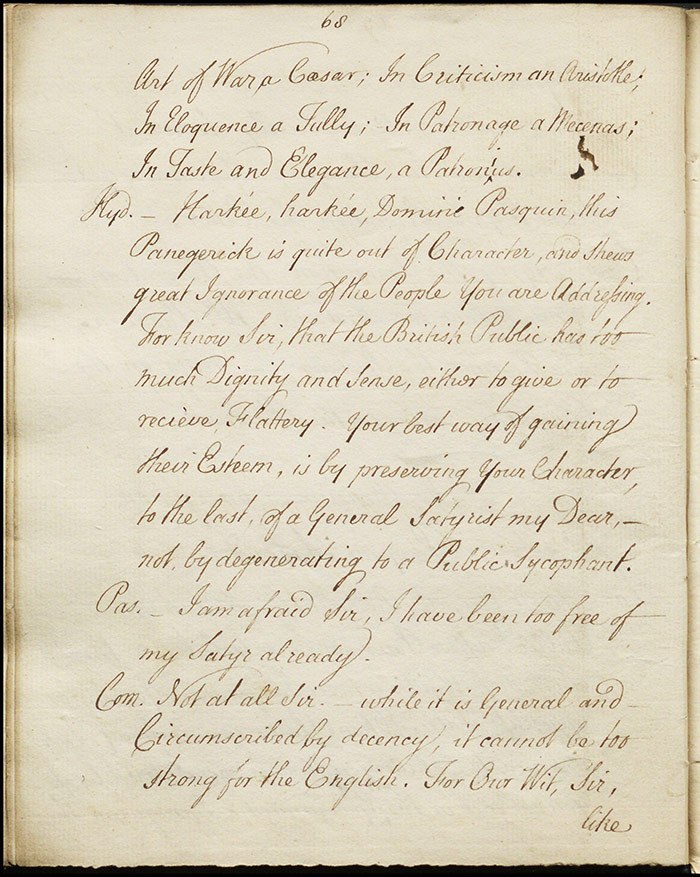

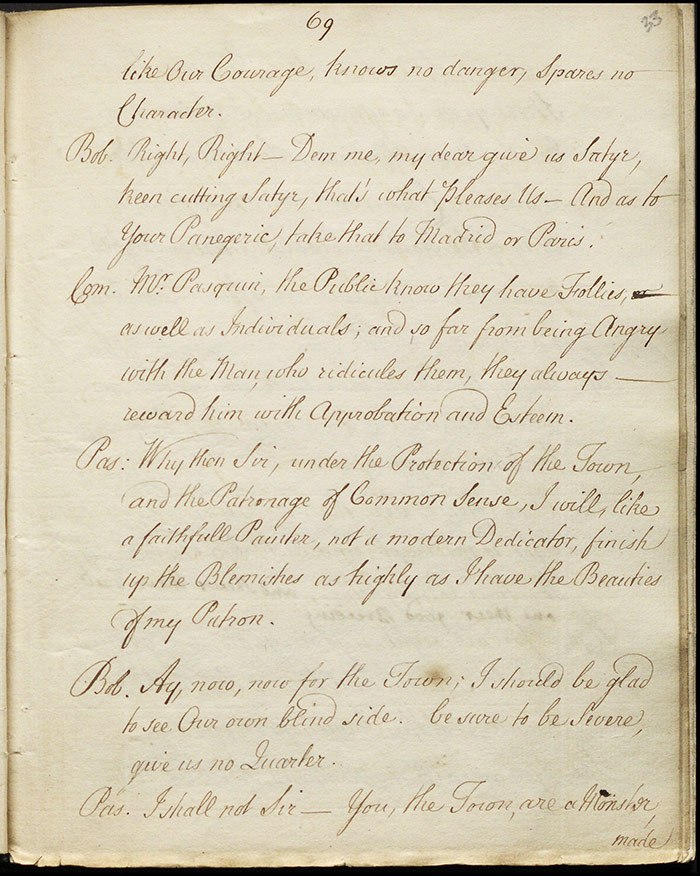

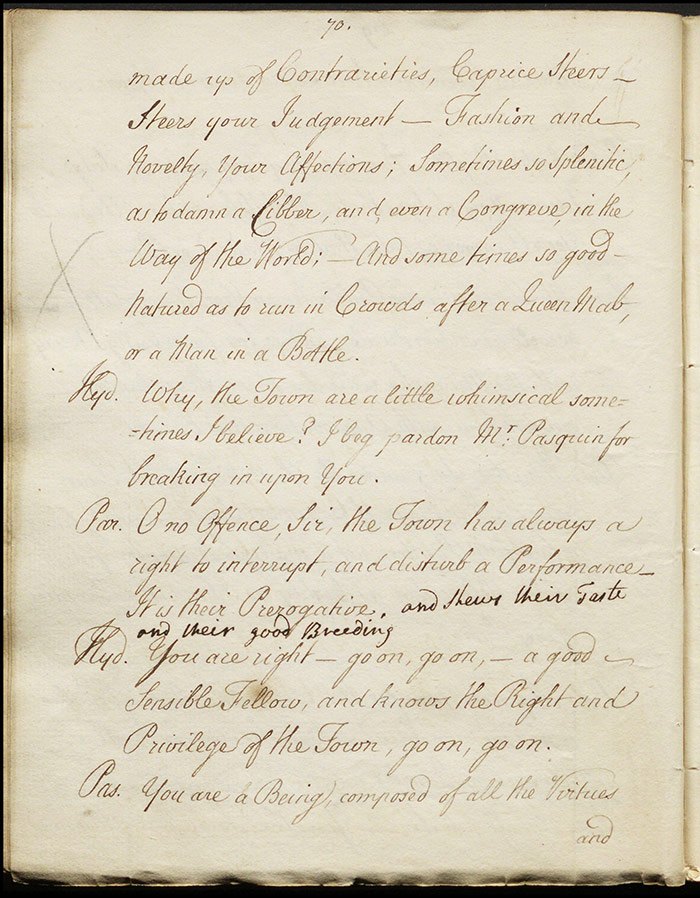

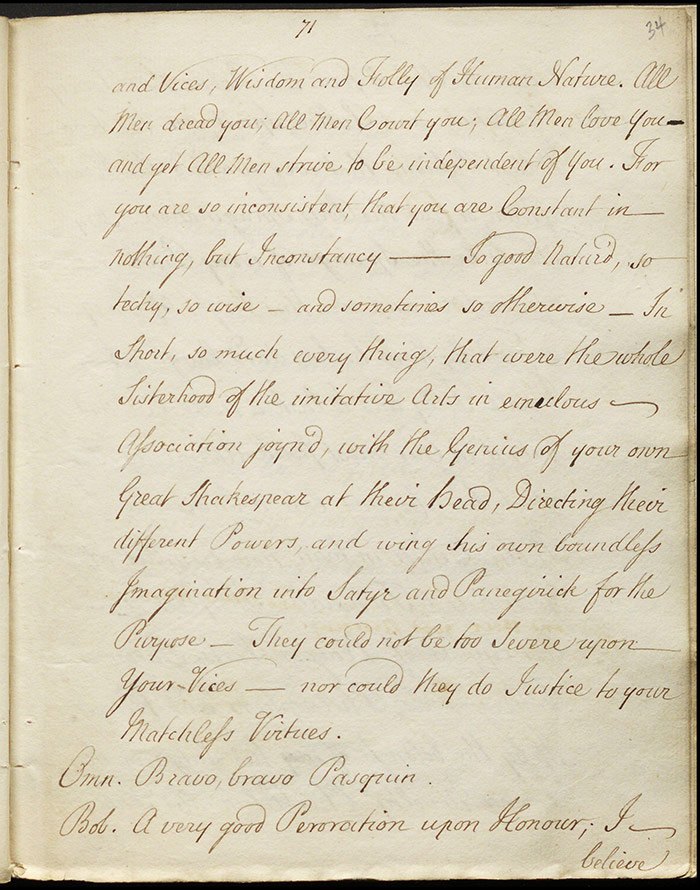

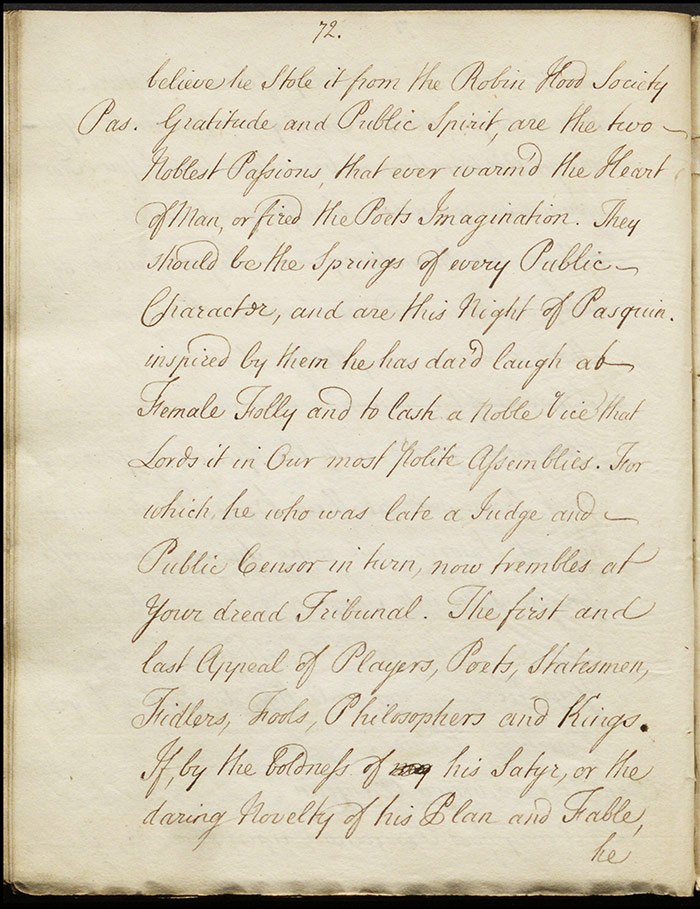

The manuscript (LA 96) shows a number of emendations and excisions in both pen and in pencil so much of the interpretive work involves determining just how many hands are at work and with which writing implement (pen or pencil). Multiple hands seem to have been at work on revising this manuscript, most likely including Macklin, John Rich (Covent Garden manager), and the Examiner of Plays (Chetwynd). There is a broad range of issues that are marked in this satire of London’s foibles: passages are censored for bawdiness, for references to real people, for disparaging lawyers and the nobility, and for an allusion to recent theatre riots.

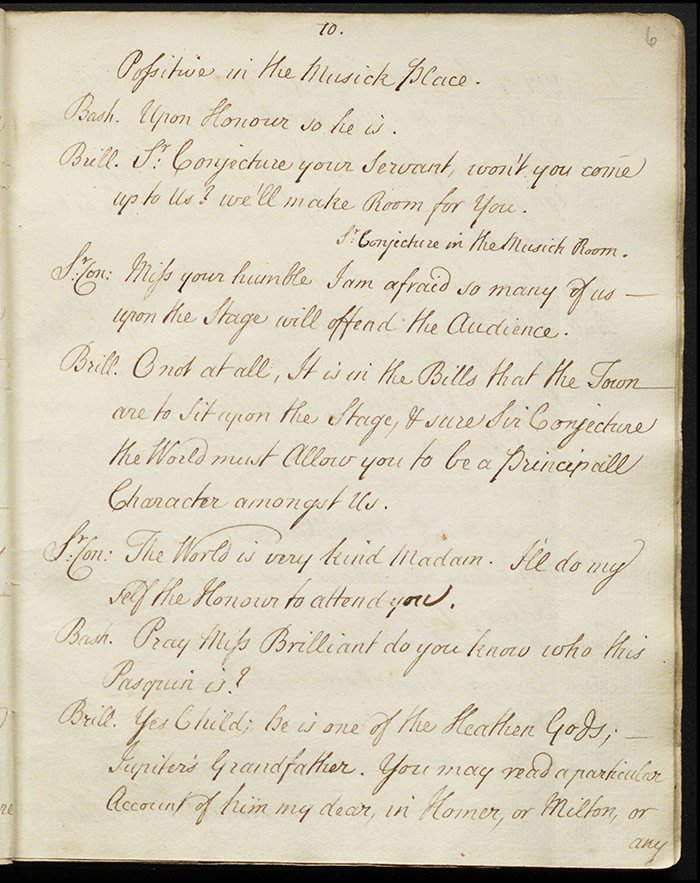

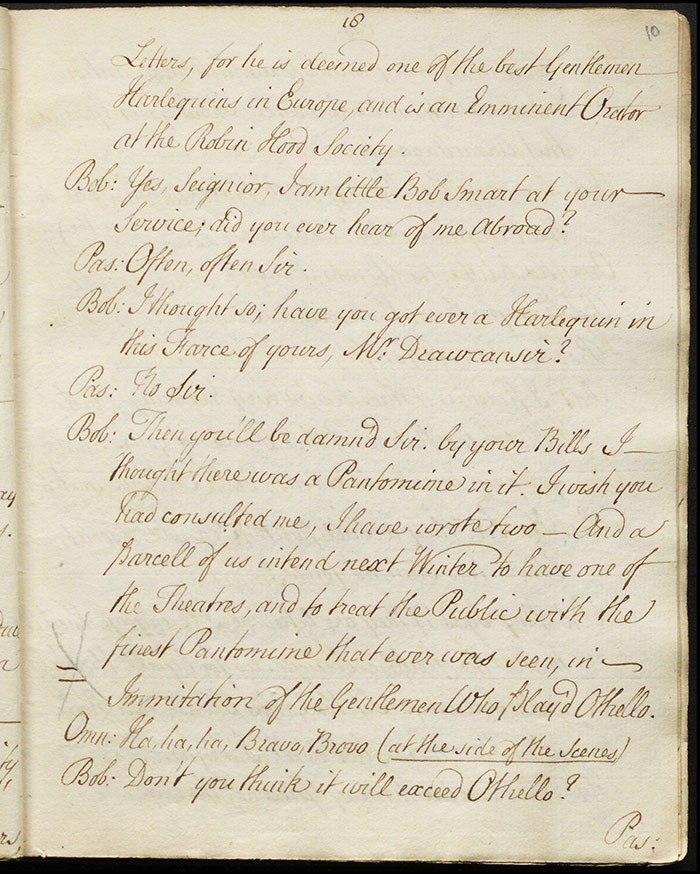

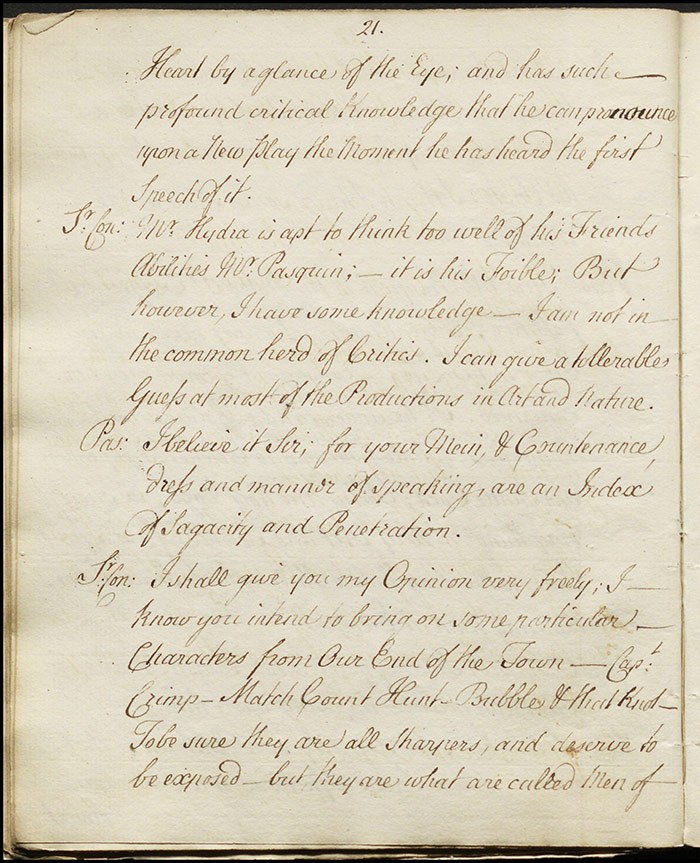

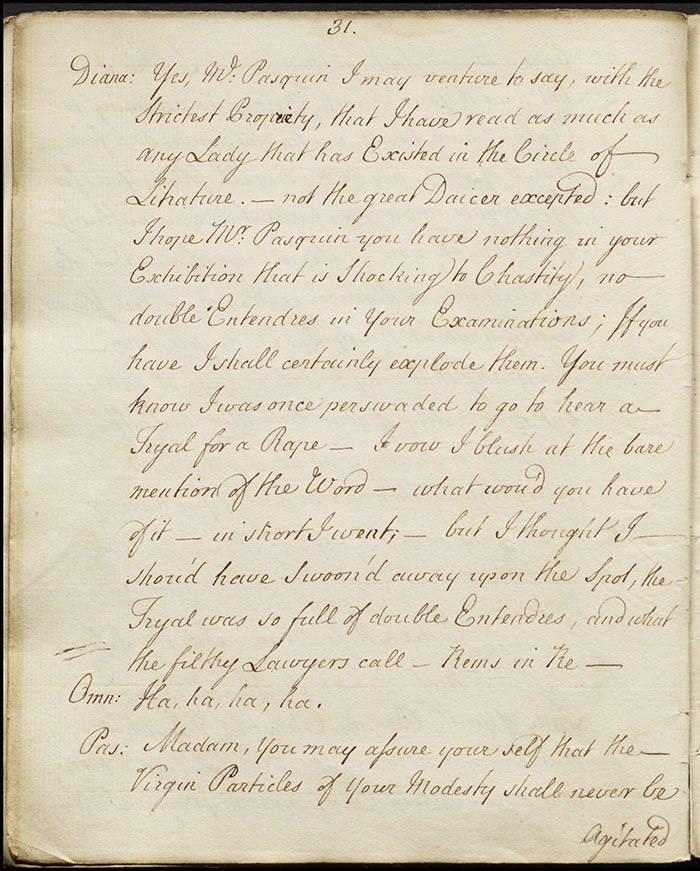

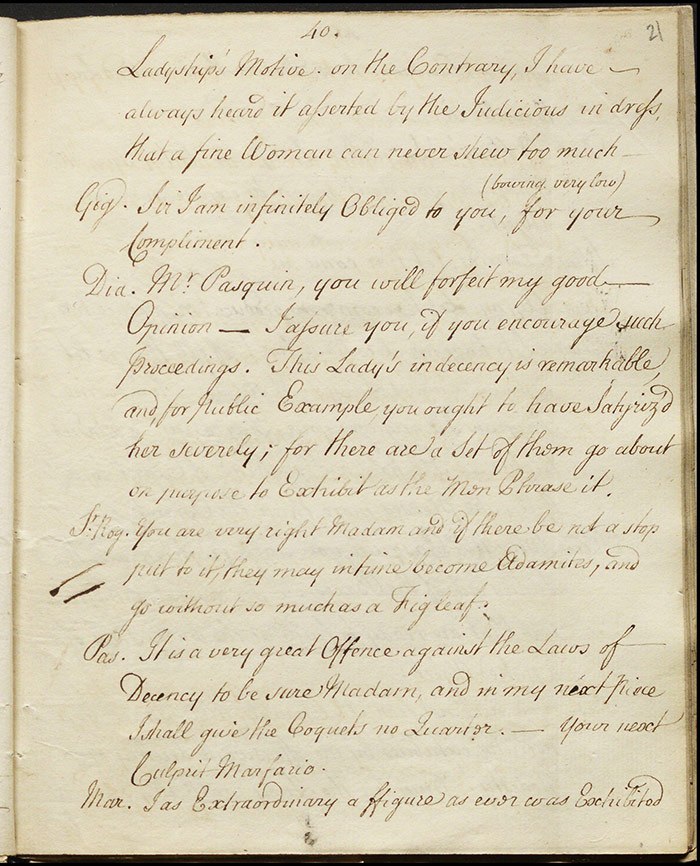

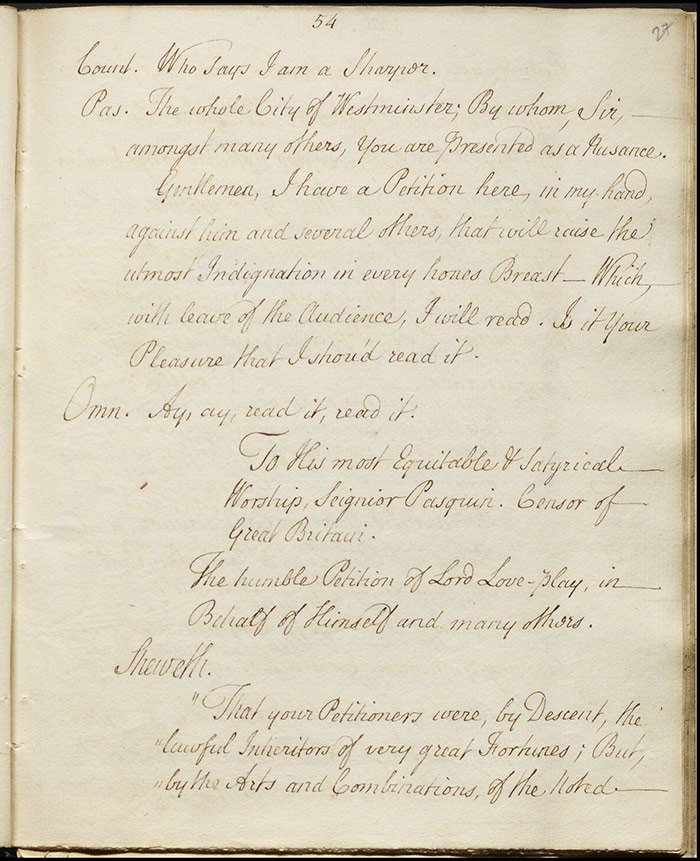

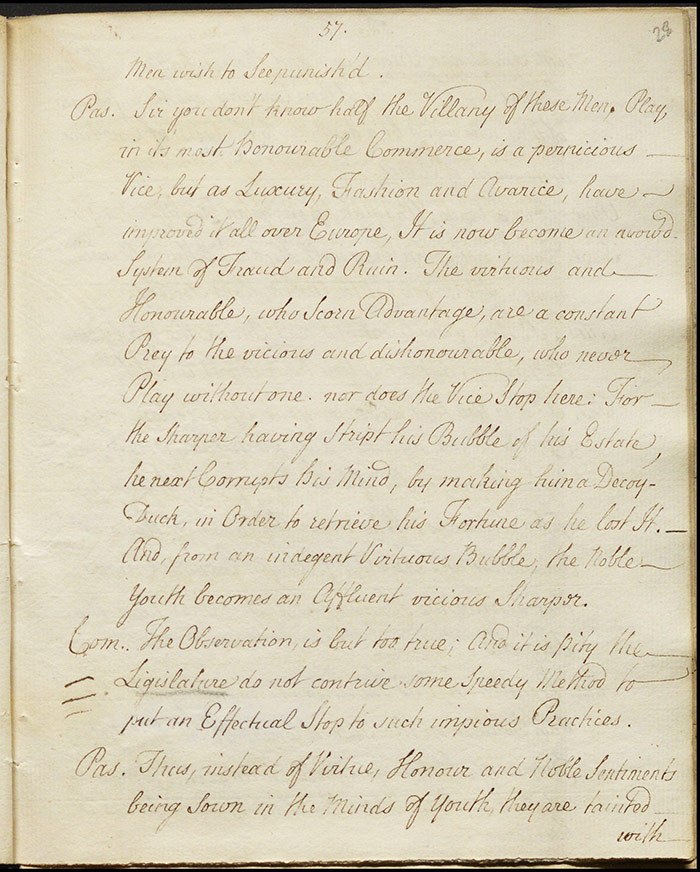

Passages that have been marked with two brief horizontal lines in pen placed in the margin include a mention of the performance of Othello staged by a group of noblemen at Drury Lane on 7 March 1751 which the character calls ‘the finest Pantomime that ever was seen’ (f.10r); a reference to ‘the filthy Lawyers’ (f.16v); a suggestion that actresses ‘might in time become Adamites, and go without so much as a Figleaf’ (f.21r); and a charge of political inaction on the part of ‘the Ligislature’ when it comes to the pernicious effects of gambling on society (f.29r). These penned emendations are likely to have been made by the Examiner. There is a distinction between them and other penned alterations which seek to suppress text entirely and/or offer editorial alterations.

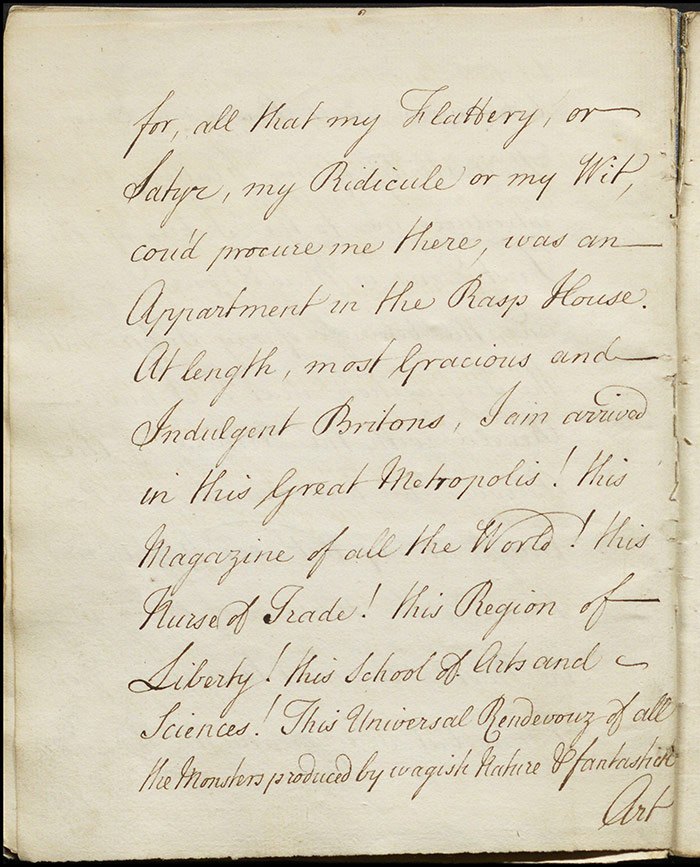

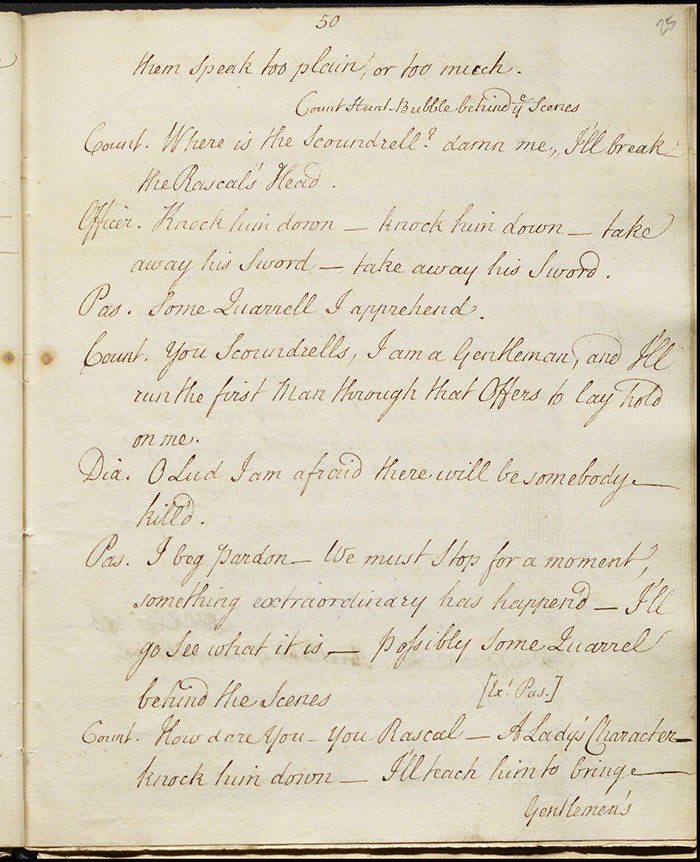

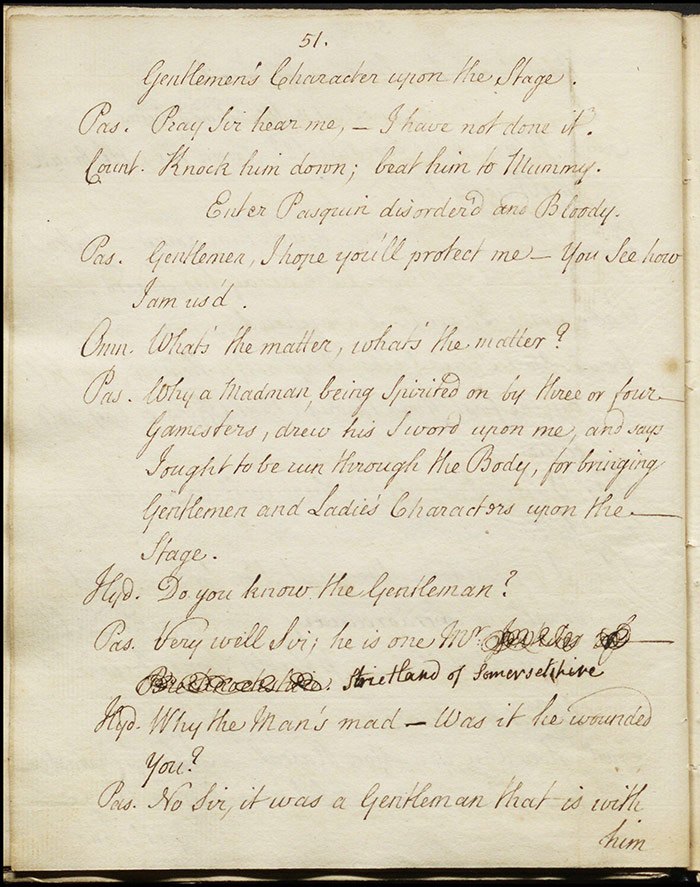

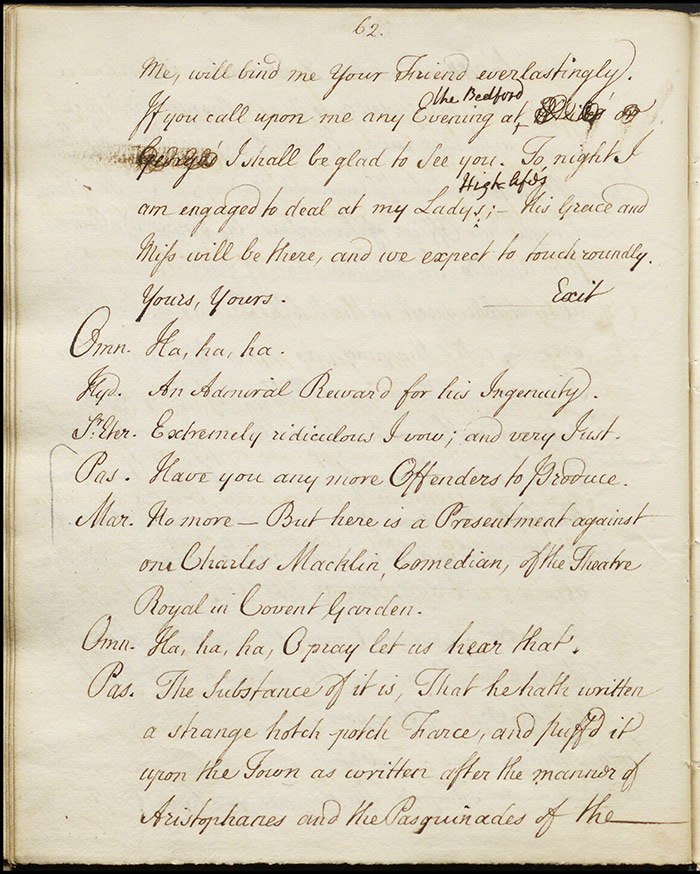

For instance, (f.1v) has a superfluous ‘your’ struck out; an innocuous editorial change that thus offers strong evidence that there is an authorial or managerial hand at play here, and one wielding a pen. On (f.4r-v), there are a number of words/brief phrases that are struck out to the extent that they are illegible and some substituted words inserted above. That the person went to such lengths to conceal the original text is suggestive: it may be that they did not want the Examiner to see how provocative the original was and thereby raise his concerns about the play’s tendencies. Some credence might be lent to this theory by examining a matching excision on (f.26v). Although there has been considerable effort to blot out the name, a careful examination reveals that Macklin is jibing one ‘Mr Jenkins of Brecknockshire’ (the crossed out name) for prudery. It is generally the case that disparaging references to real people would not be tolerated by the Examiner so the more innocuous and fictional ‘Mr Strictland of Somersetshire’ is inserted instead, possibly by Rich or perhaps even by a repentant or more cautious Macklin. It seems improbable that the Examiner would go to such lengths to obliterate the name.

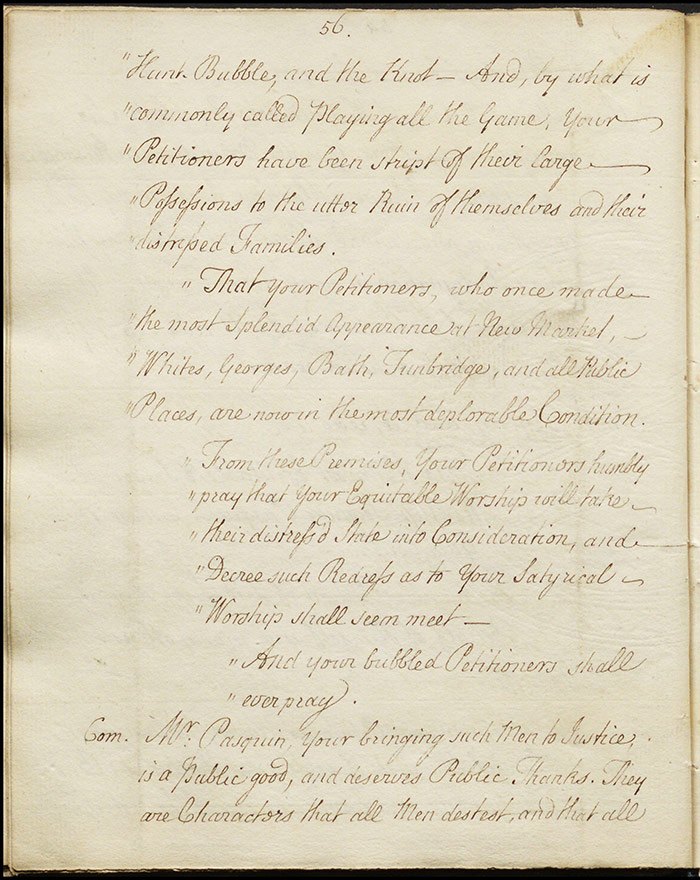

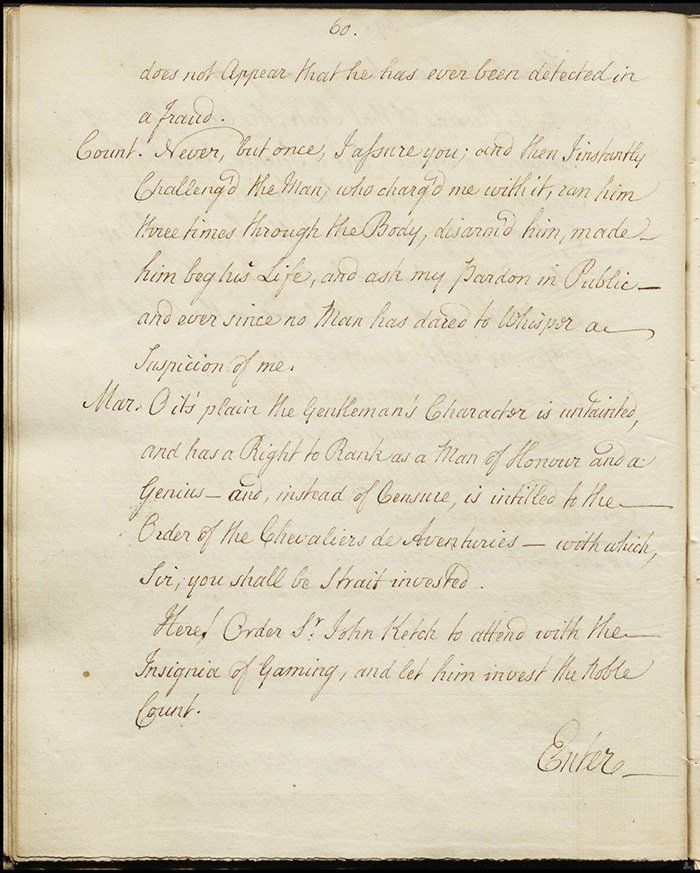

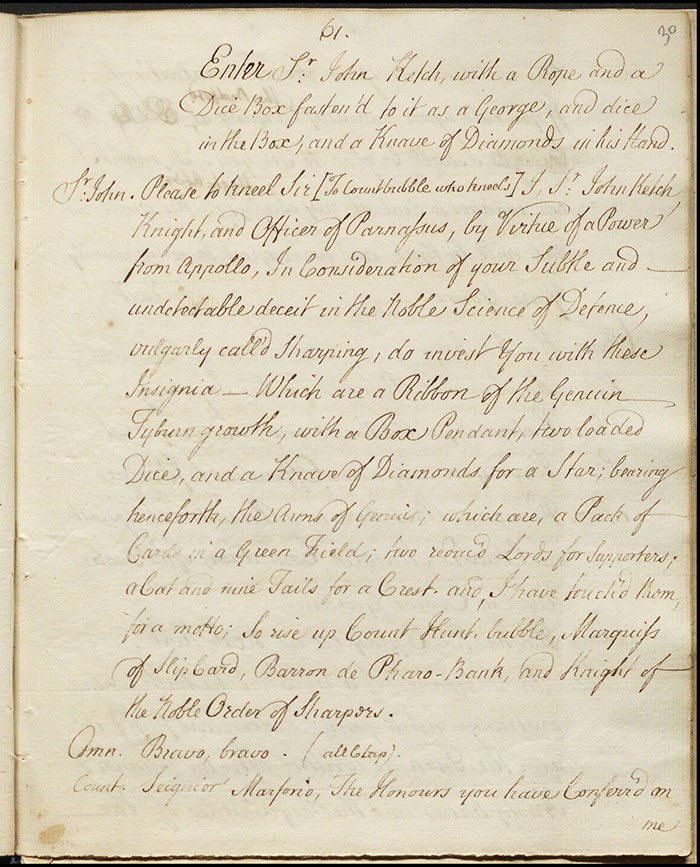

Another excision on (f.31v) might support this reading as well as helping to identify Mr Jenkins. Here, the degenerate Count Hunt Bubble’s mention that he can be found at White’s or George’s is also heavily scored out but it is also just about legible. White’s refers to the exclusive London coffee house on St James’s Street frequented by the aristocratic class and known for its heavy gambling, while George’s might refer to St George’s Church on Hanover Square (where Handel worshipped), again a site for the well-to-do. One possibility is that the Examiner would not have liked the implication that Hunt Bubble would have easy pickings on foolish and dissolute young nobles at both these venues; alternatively, it may be that the conflation of the church and gambling house gave pause and ‘the Bedford’ was inserted above, Covent Garden’s coffee-house, known for its theatrical clientele, offering a less provocative connection to the nefarious activities of Hunt Bubble.

One might well argue that George’s in fact references George’s Coffeehouse on Chancery Lane but we may note that there is also a contemporary reference to Mr Jenkins as Clerk and Sexton of St George’s, the church on Hanover Square. The possibility that Macklin was poking fun at a local character who was exercised by the threat of theatre to public morality seems plausible. An insertion on (f.35v) which augments the praise of the audience ‘and shews [the Town’s] Taste and good Breeding’ also points to some mollifying editing on the part of Macklin or Rich.

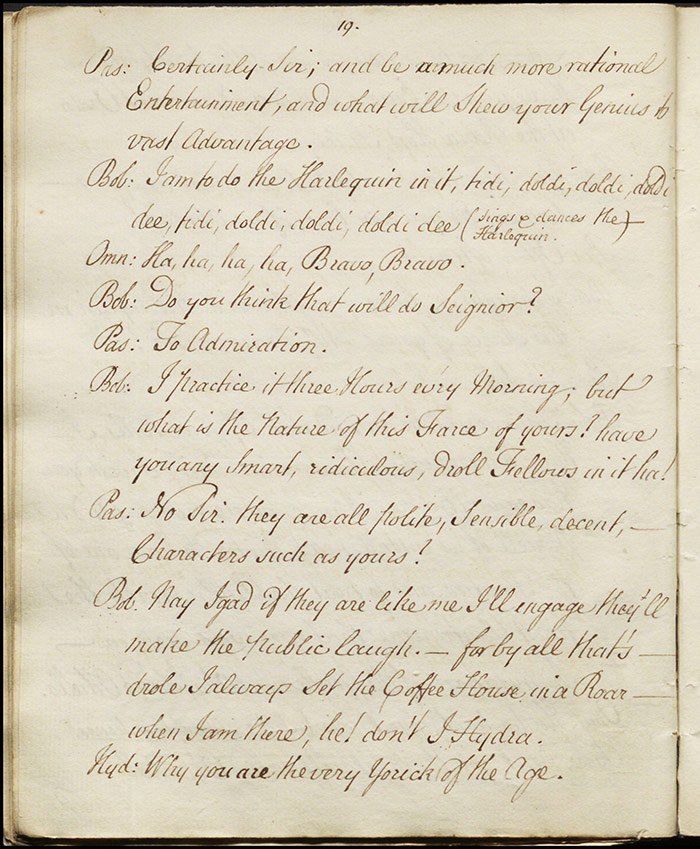

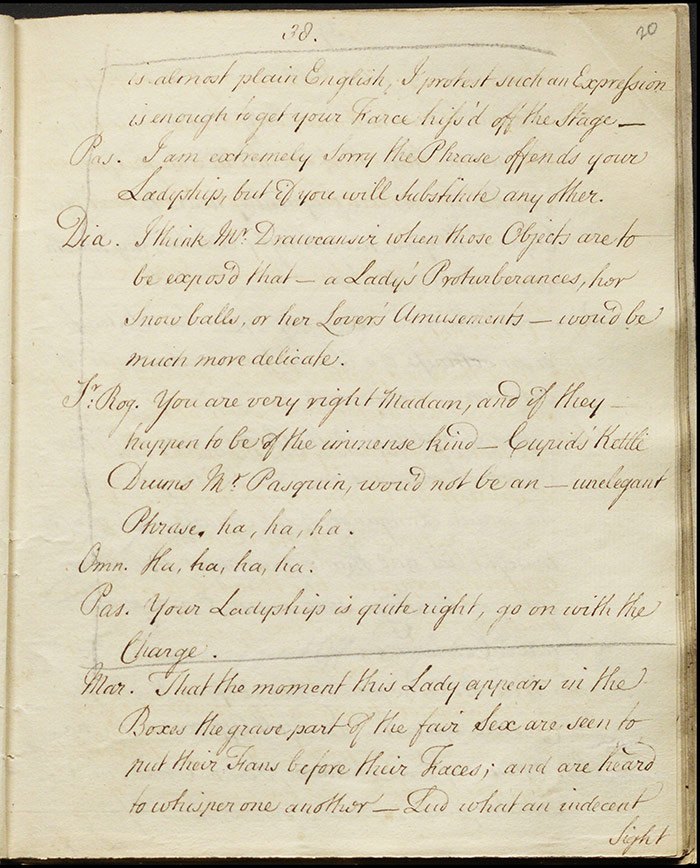

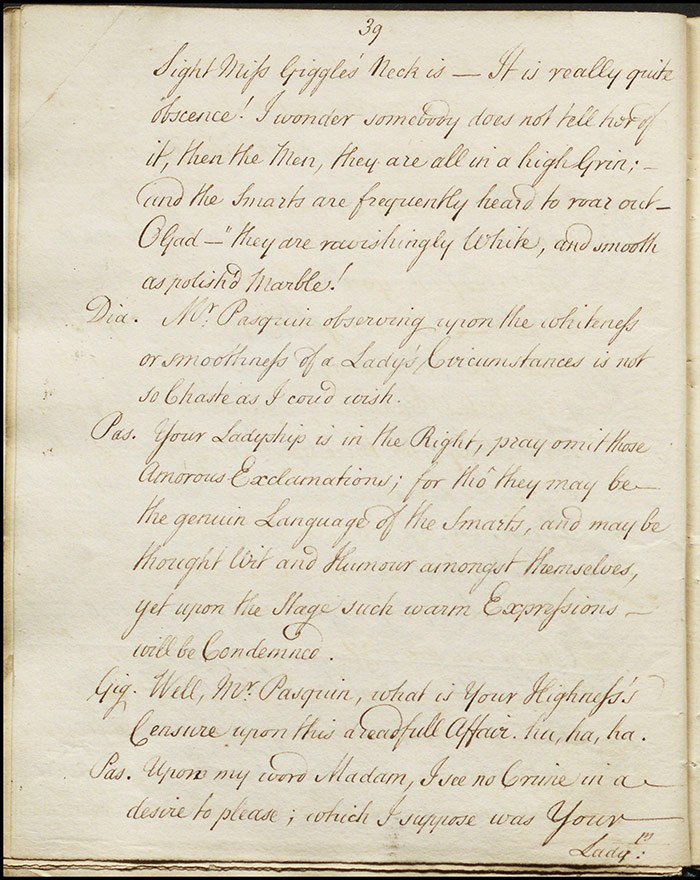

There are further complications added when we consider the pencil marks on the manuscript. Perhaps the most spectacular excision in the play is the extended reflection on female breasts that is contained within the boxed sections on (f.19v) and (f.20r). The passage, where breasts are described in various ways culminating with a bawdy suggestion from the debauched Sir Roger Ringwood that ‘if they happen to be of the immense kind – Cupid’s Kettle Drums Mr Pasquin, wou’d not be an unelegant Phrase’ (f.20r), raises further intriguing possibilities as to who is marking the text. If one accepts the premise above that the manager or author excised certain passages to the point of illegibility in order to avoid irking the Examiner, one might be inclined to argue that this passage is the work of the Examiner. The logic being that the submitters would have inserted a more demonstrative censorious expression for the Examiner’s benefit (e.g. marking the text with an ‘X’). Of course, the consequence of this line of thinking is that it suggests a rather naïve or bombastic attitude on the part of Macklin and Rich: it is puzzling to consider why they thought this material would have been deemed appropriate for the patent theatre stage.

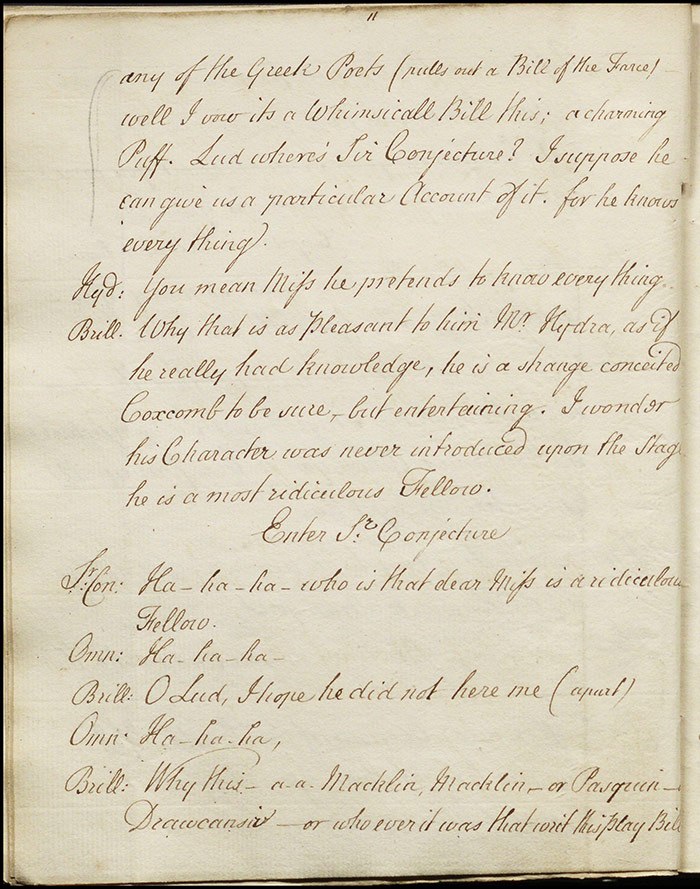

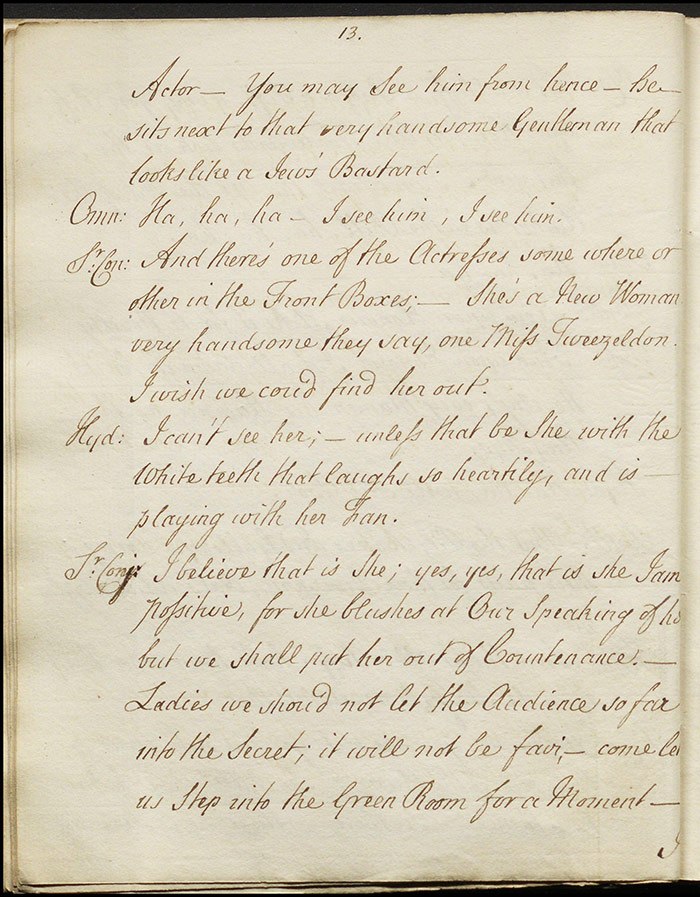

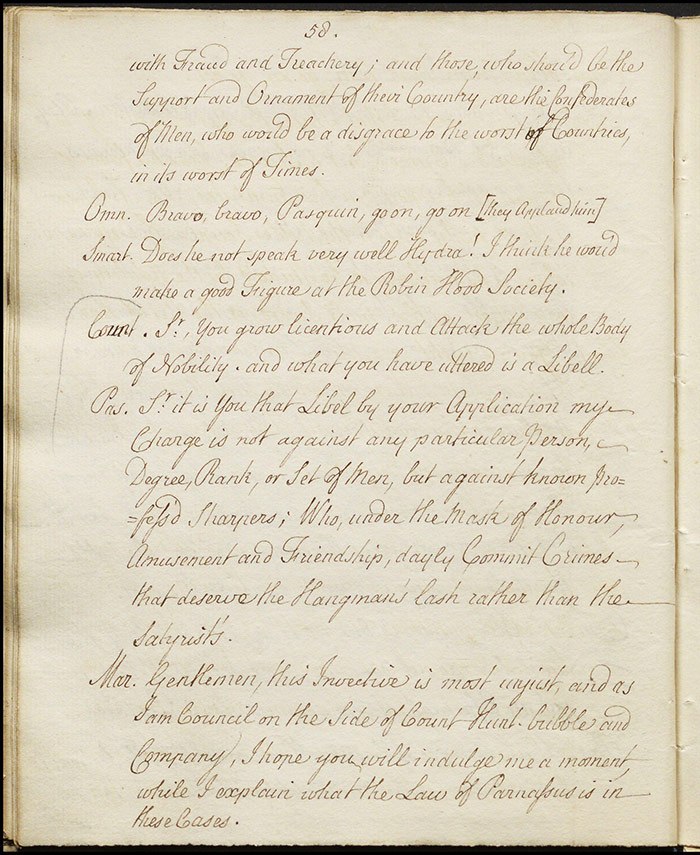

A further consequence of this analysis is the conclusion that the Examiner took two passes through the manuscript, one with pen and one with pencil. We might consider the marginal mark on (f.31v) as further evidence of this: here, a reference to ‘one Charles Macklin, Comedian, of the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden’ is marked with a penciled line in the margin. It seems reasonable to assume that Macklin or Rich would not object to a self-reference put in by Macklin and the mark is consistent with other references to people such as Samuel Foote and Henry Fielding (f.13r-v) that seem to be marked with the same style of penciled emendation (as there is no textual evidence to demonstrate the Examiner knew who penned the manuscript). Moreover, a reference on (f.29v) to Pasquin ‘Attack[ing] the whole Body of Nobility’ also seems likely to have been objected to by the Examiner.

There are three passages marked with a penciled ‘X’ in the margin which offer further puzzles. They are, as we shall see, more provocative than those listed above so the introduction of the ‘X’ might indicate the increased vehemence of the Examiner’s objections or they might indicate a second party—such as Rich— who felt that these would not likely pass the Examiner and they are thus pre-emptive actions. The first example (f.10r), the reference to the Delaval family’s Othello, is even more complicated as the relative proximity of the emendations (a penciled X and the penned double line) suggest further possibilities. Subsequent penciled X passages on (f.11r) and (f.35v) allude to Samuel Foote’s poor taste and to the Haymarket ‘Man in a bottle’ theatre riots of January 1749. It seems probable that these are allusions that might be thought jocular by theatre people but objectionable to an Examiner. Two references to puffing have also been marked by penciled lines in the margin (f.6v),( f.7r).

N.B. This manuscript was misfoliated so while the folio numbers cited here will not match up with those of the scanned manuscript in references that appear after f.22, they are correct.

The Othello performance alluded to was staged by the Delaval family who had a passion for private theatricals and were instructed by Macklin. Such was the level of interest in the 7 March 1751 Drury Lane performance that the House of Commons adjourned at 3 o’clock in order to facilitate attendance. See Appleton, 93-94.

Lloyd’s Evening Post, and British Chronicle for the Year 1758 (Jan to June [1758]), 147.

Further reading

William W. Appleton, Charles Macklin: An Actor’s Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960).

Matthew Kinservik, Disciplining Satire: The Censorship of Satiric Comedy on the Eighteenth-Century London Stage (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2002).

Esther M. Raushenbush, ‘Charles Macklin’s Lost Play about Henry Fielding’, Modern Language Notes 51:8 (1936), 505-514.

Robert Shaughnessy, ‘Macklin, Charles (1699?–1797)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2015, accessed 11 Aug 2015.