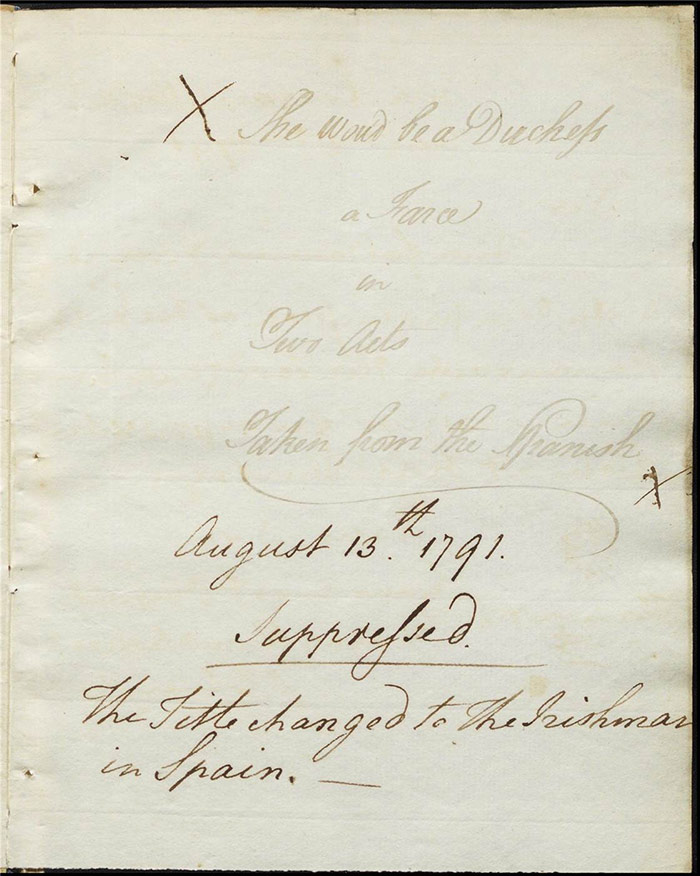

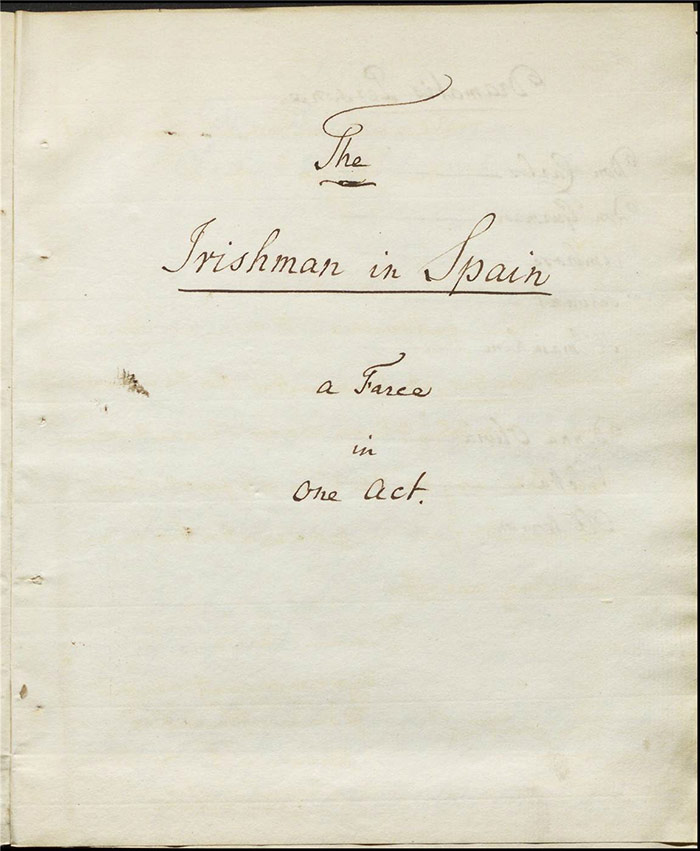

She Would be a Duchess (1791) LA 915

Author

Charles Stuart (?)

Stuart was the author of a number of slight pieces of theatre in the 1770s and 1780s. These include The Cobler of Castlebury (CG, 1779); Ripe Fruit; or, The Marriage Act (H2, 1781); Gretna Green (H2, 1783); The Distres’d Baronet (DL, 1787); The Box-Lobby Loungers (DL, 1787); and, The Stone Eater (DL, 1788). There is no further information readily available on his life.

Plot

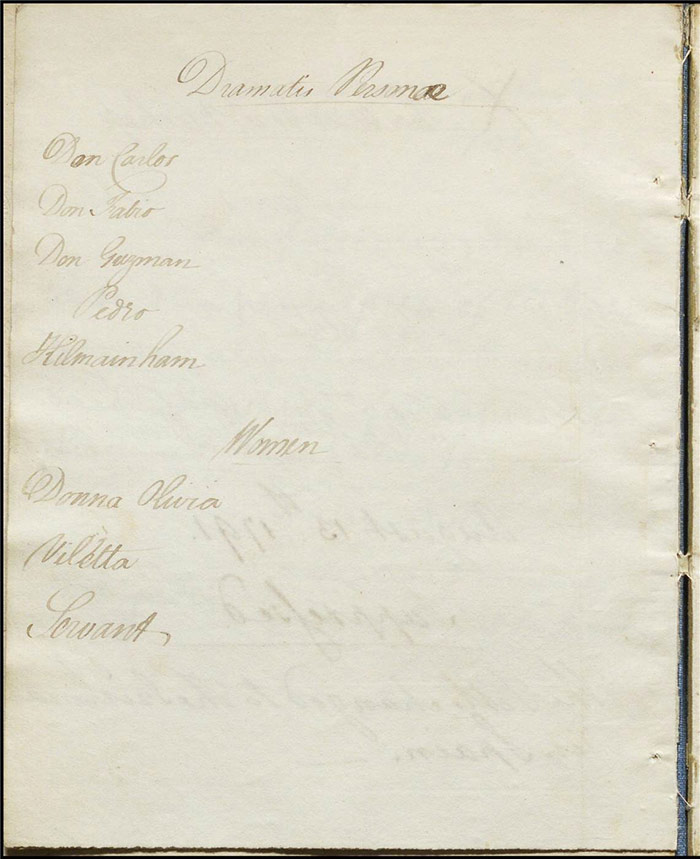

The plot of the two-act afterpiece She would be a Duchess—the original submission that was refused a licence—is given. The ‘Commentary’ briefly highlights the main plot differences between it and the one-act revision.

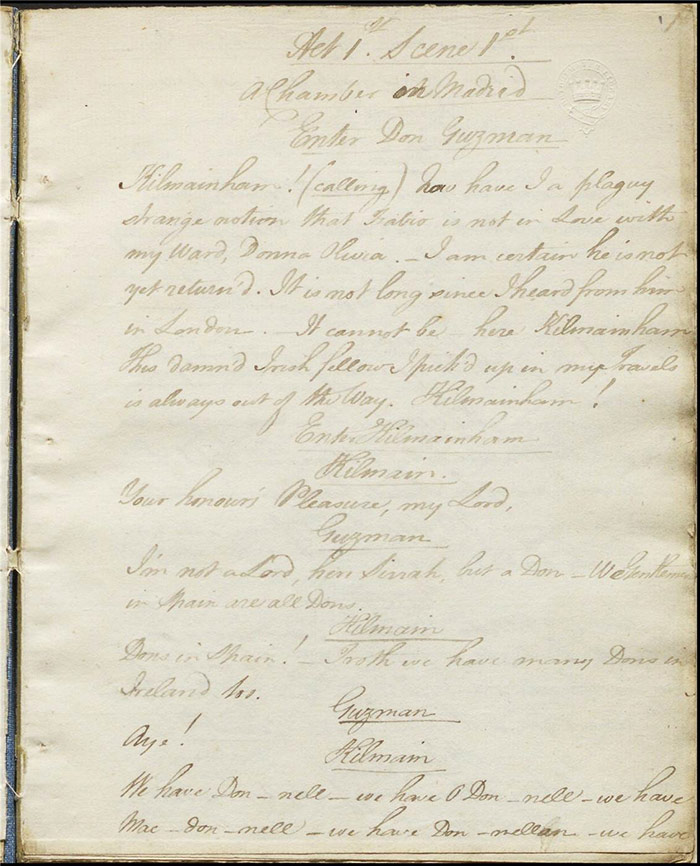

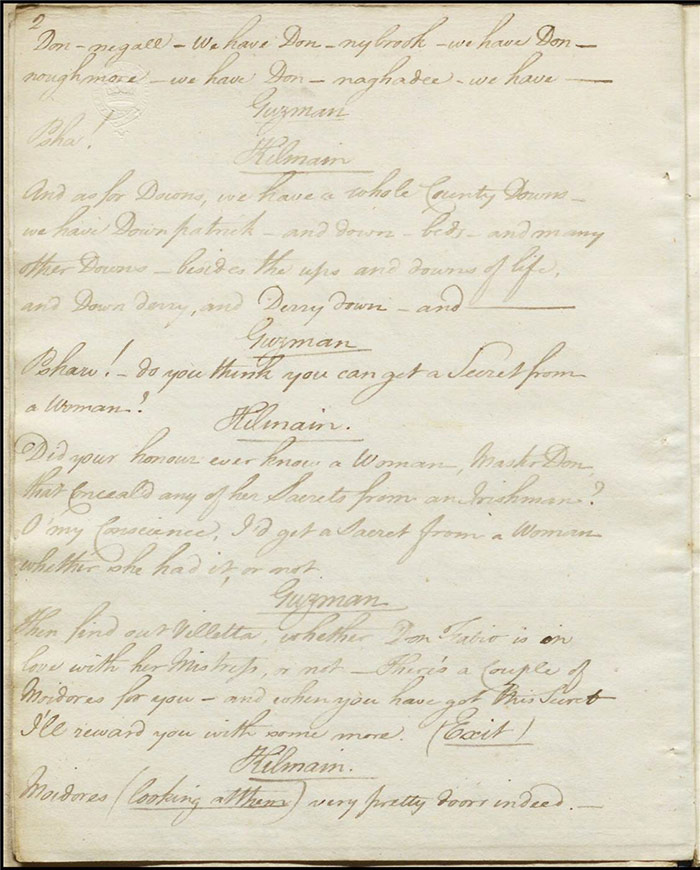

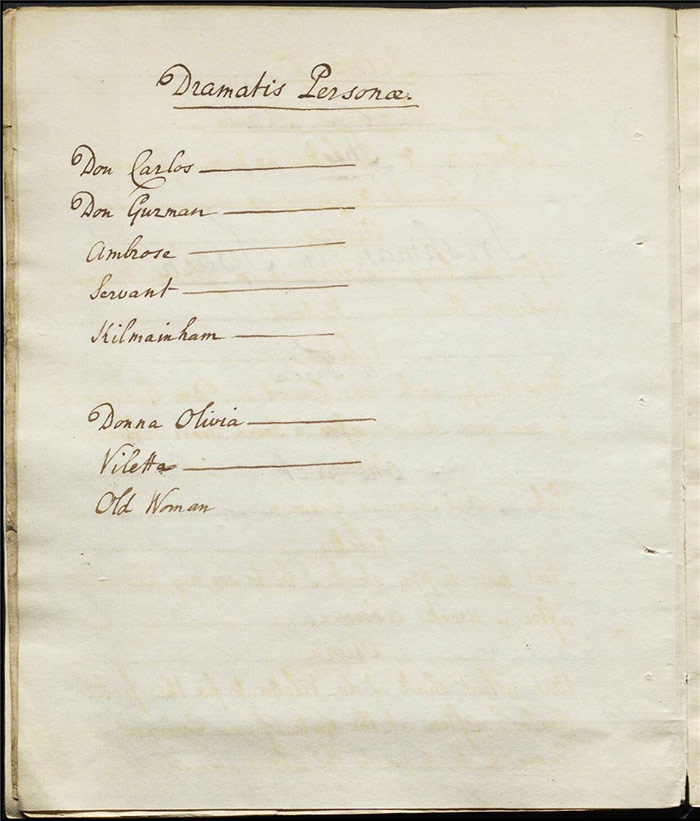

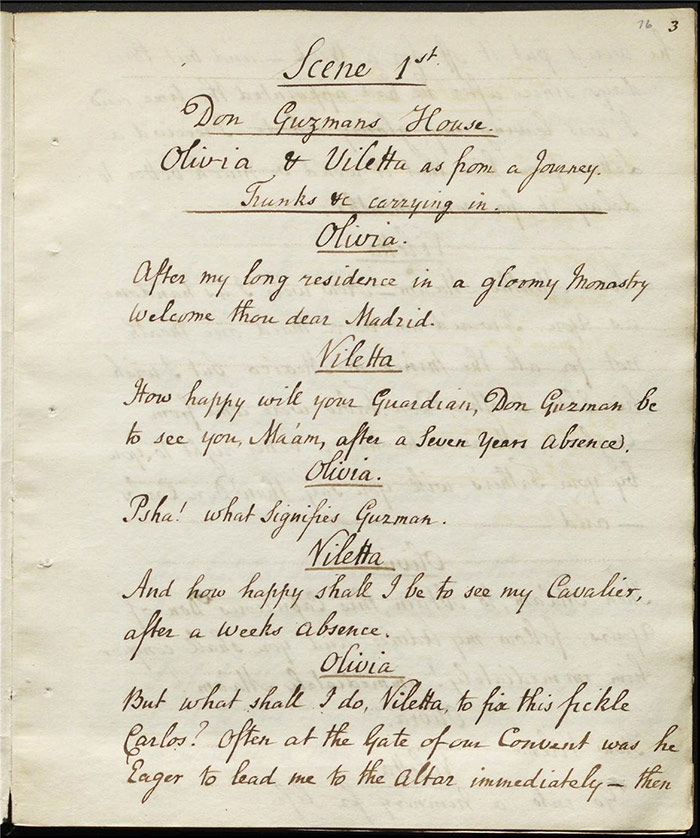

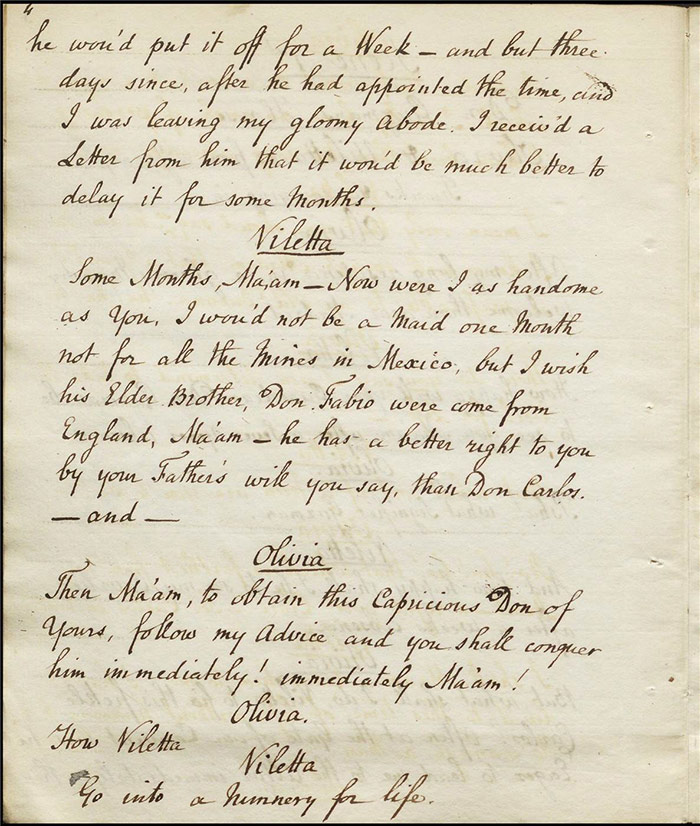

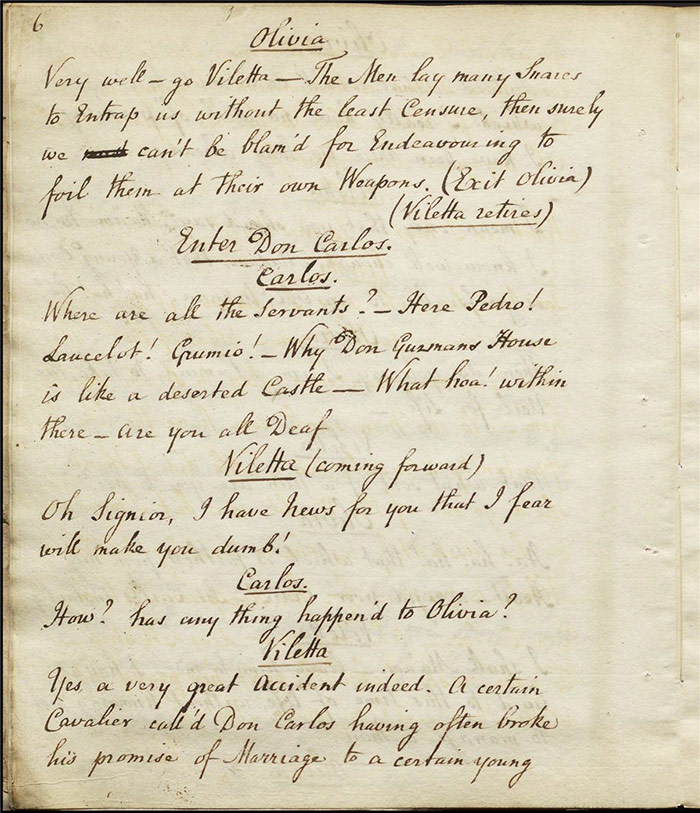

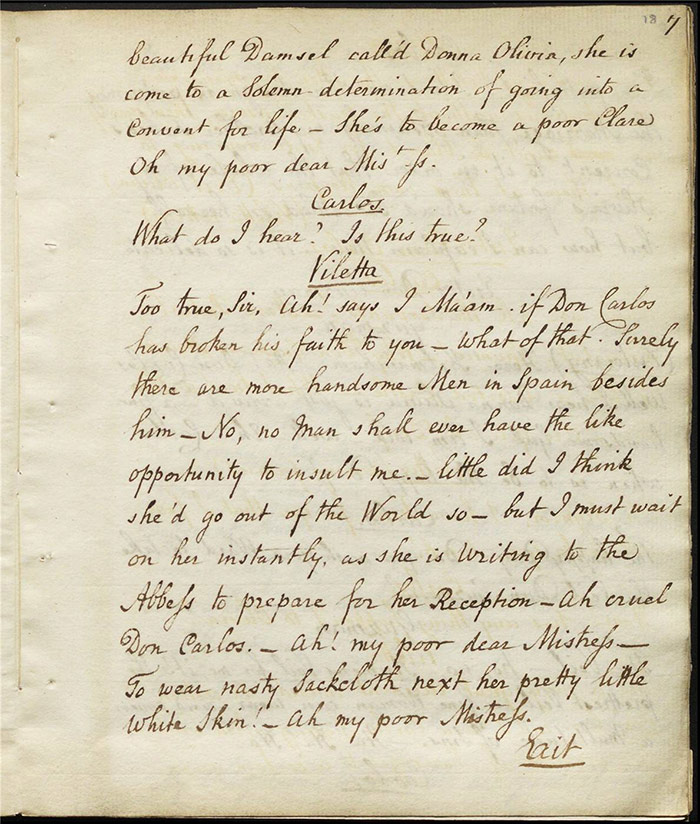

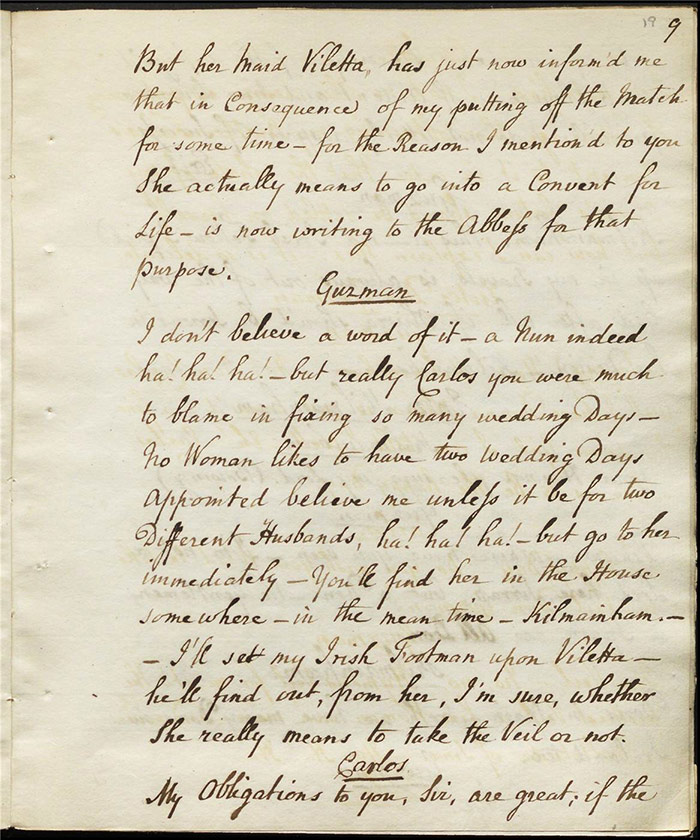

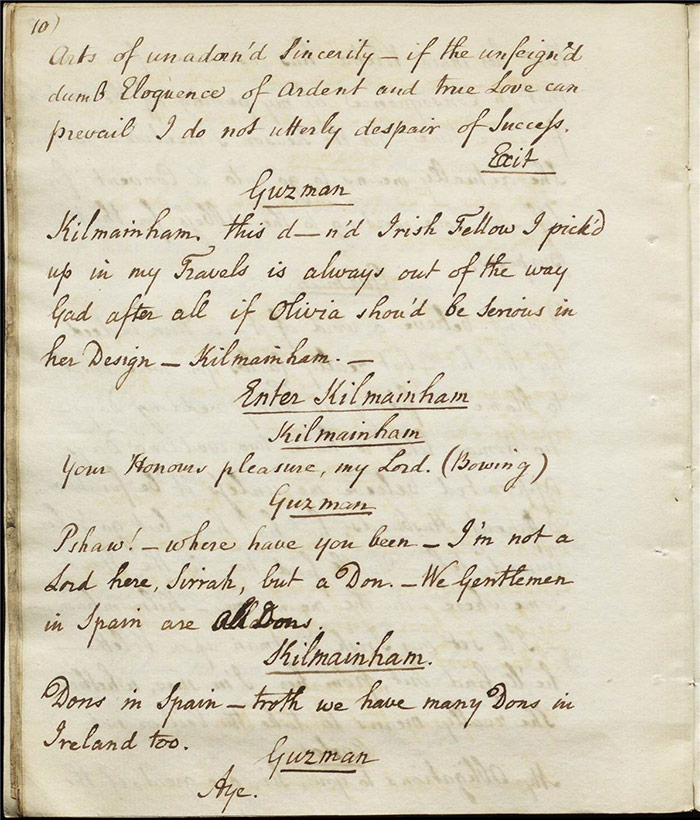

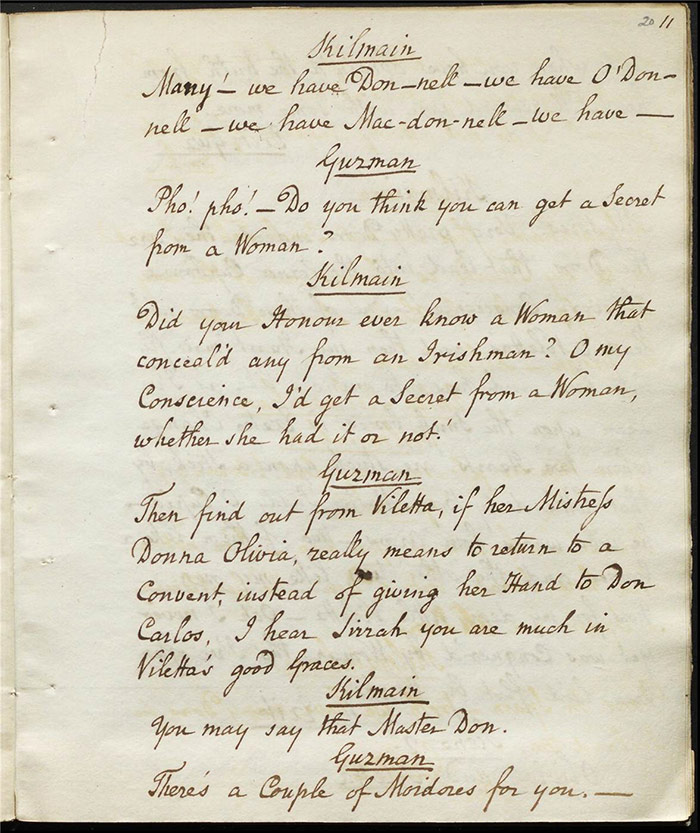

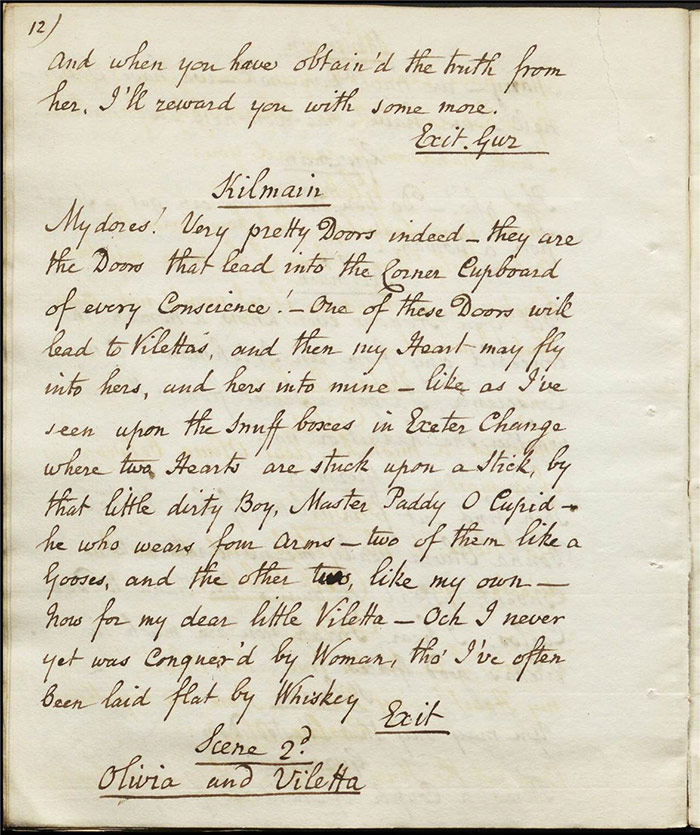

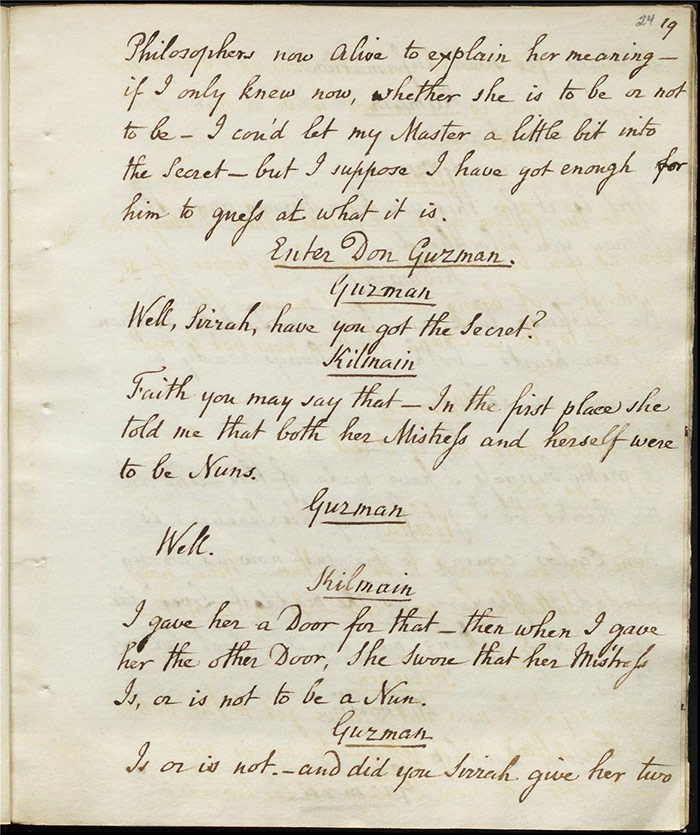

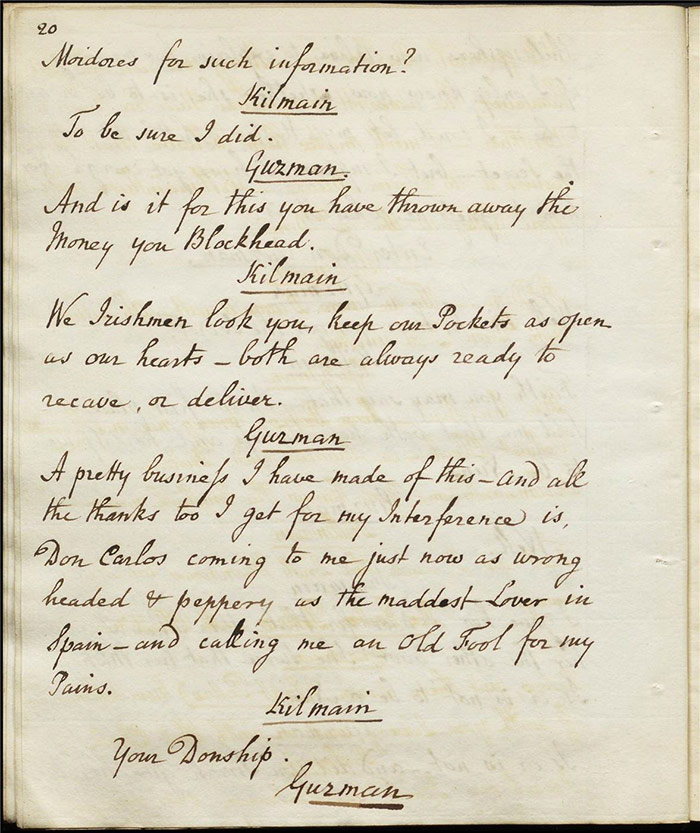

Don Guzman, fretting that Don Fabio may not be in love with his niece Olivia, commissions his Irish servant Kilmainham to discover the truth by approaching Viletta, Olivia’s maid. Olivia, however, is in love with Don Carlos but complains about his fickle nature to Viletta; they conspire to fabricate correspondence with Don Fabio in order to provoke Don Carlos to commit to their marriage. Viletta shows Don Carlos the forged letter purporting to be from Don Fabio and is enraged, promising to kill him in a duel. Viletta passes off a purported letter from Don Fabio to Kilmainham; he in turn brings it to Don Guzman who recognizes it as a forgery.

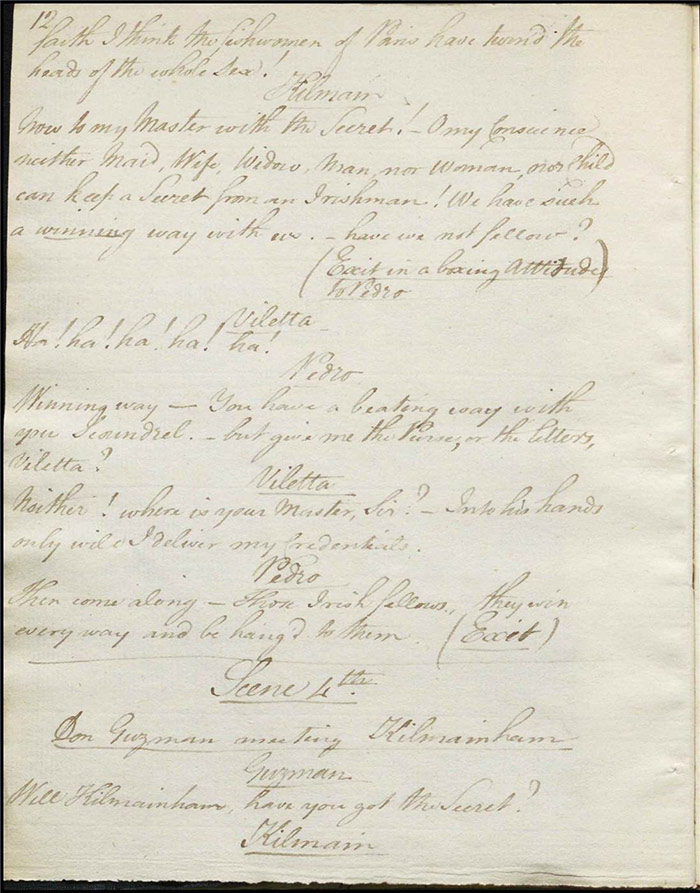

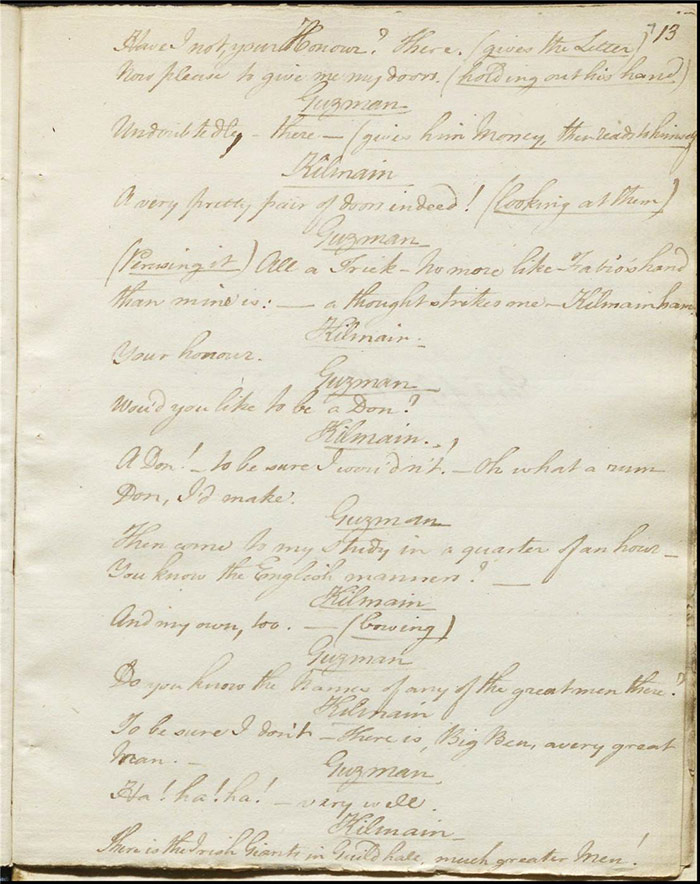

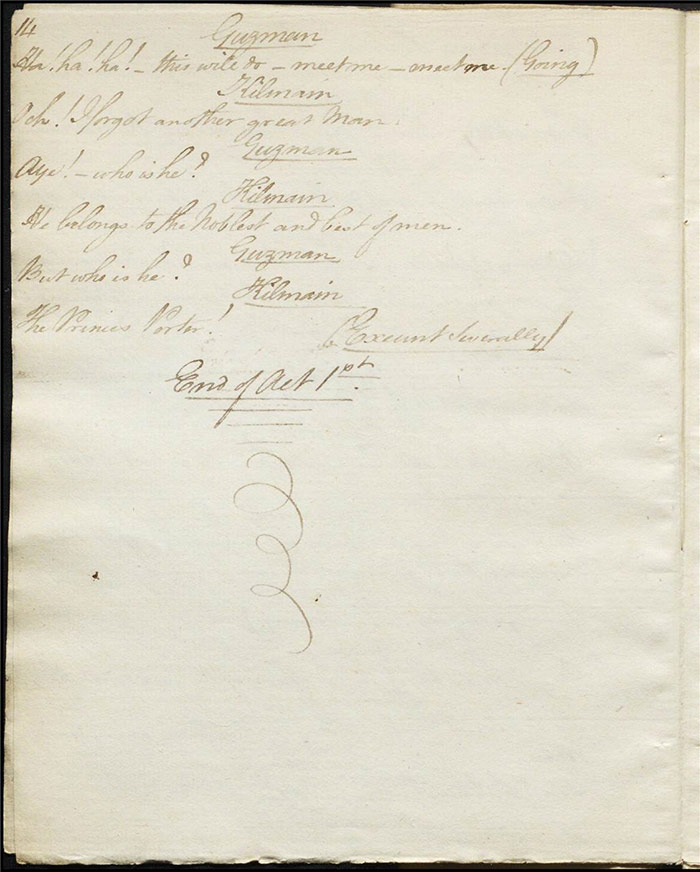

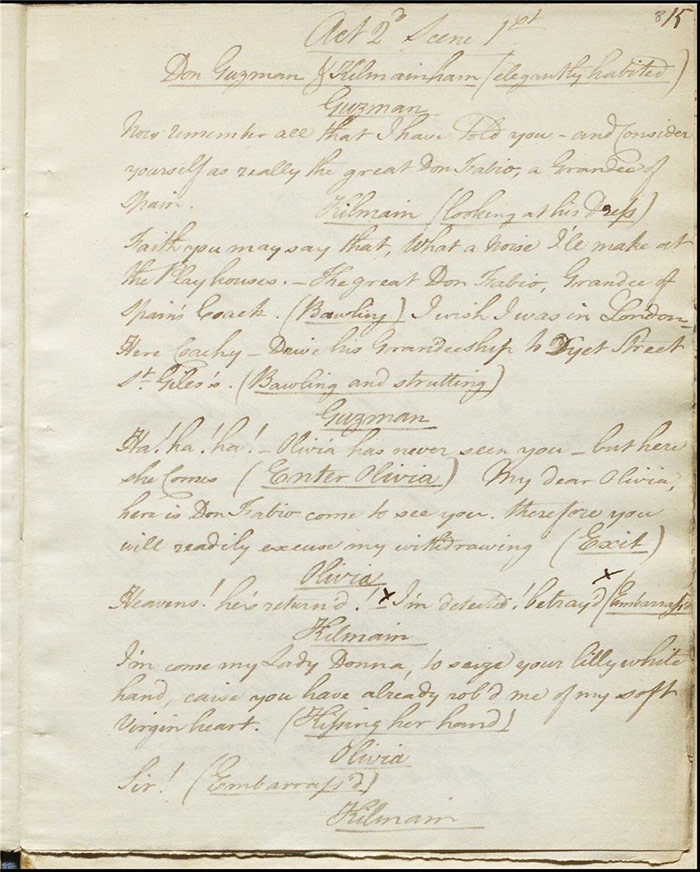

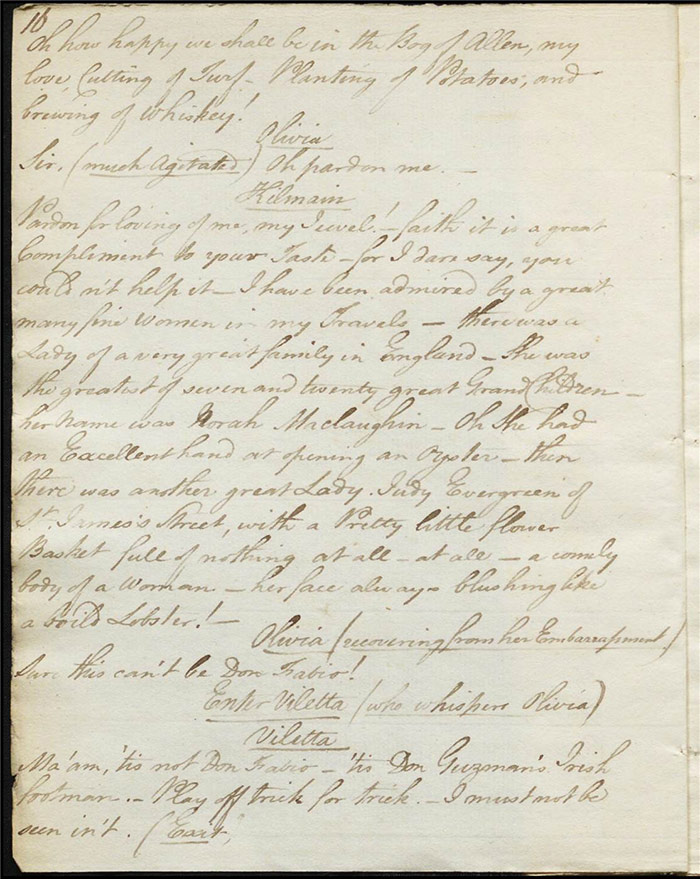

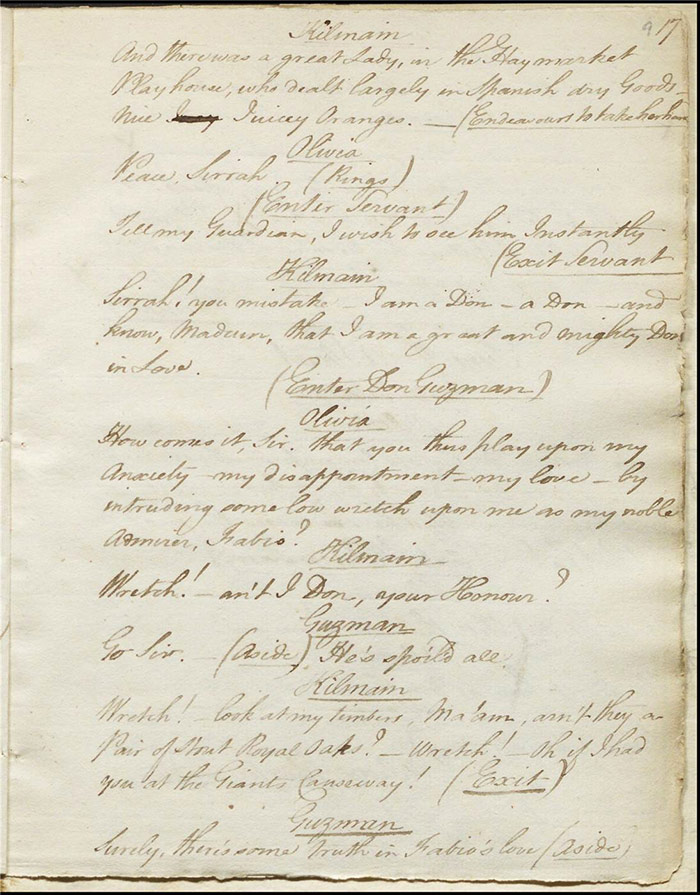

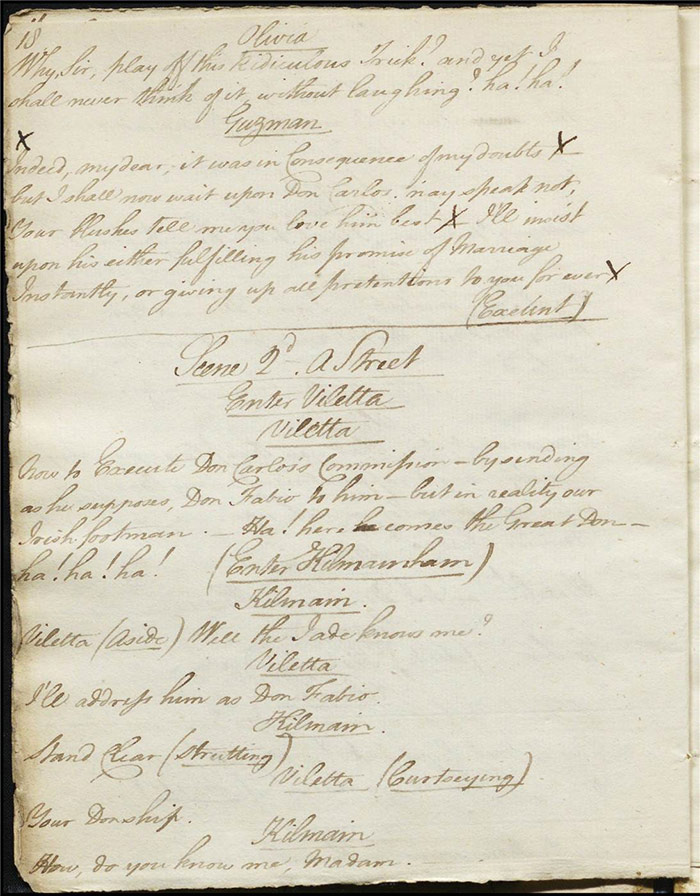

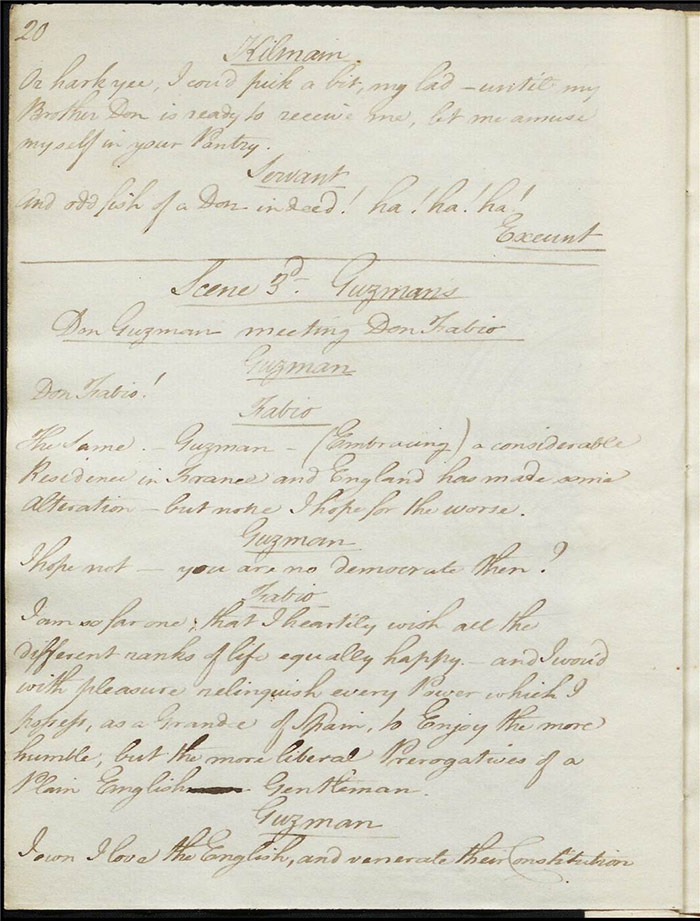

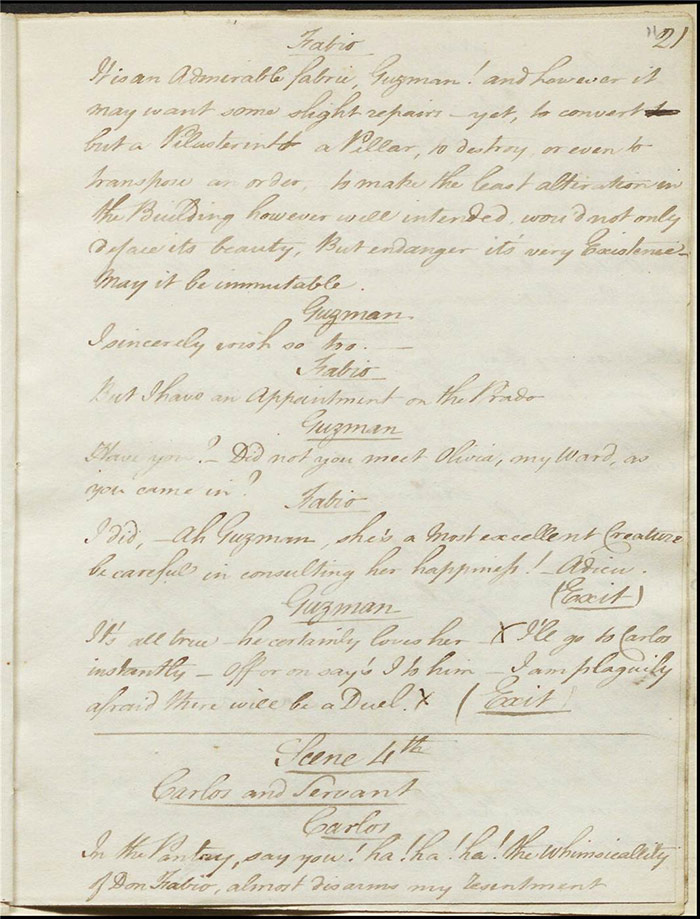

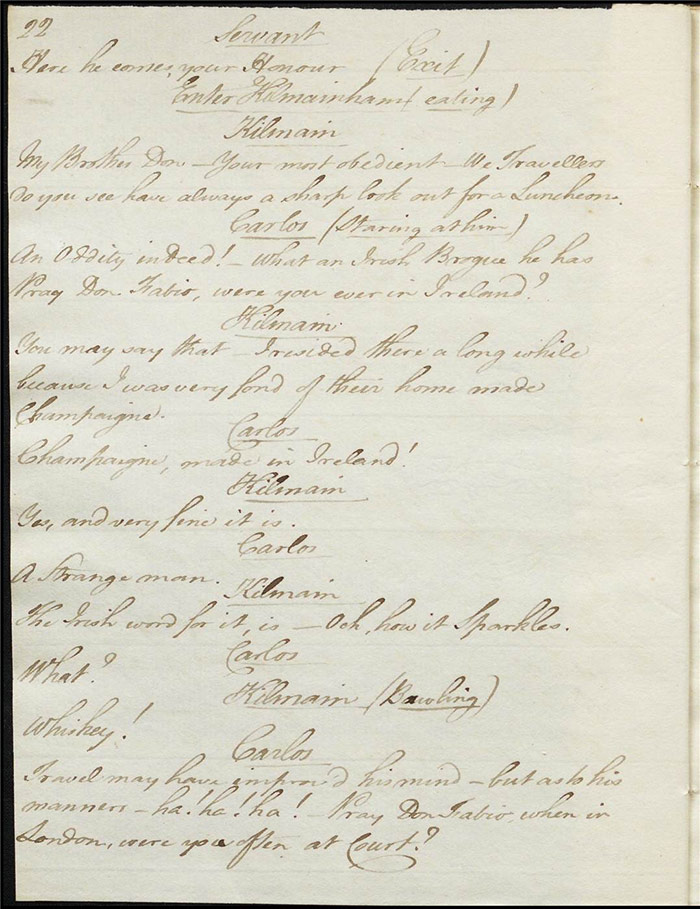

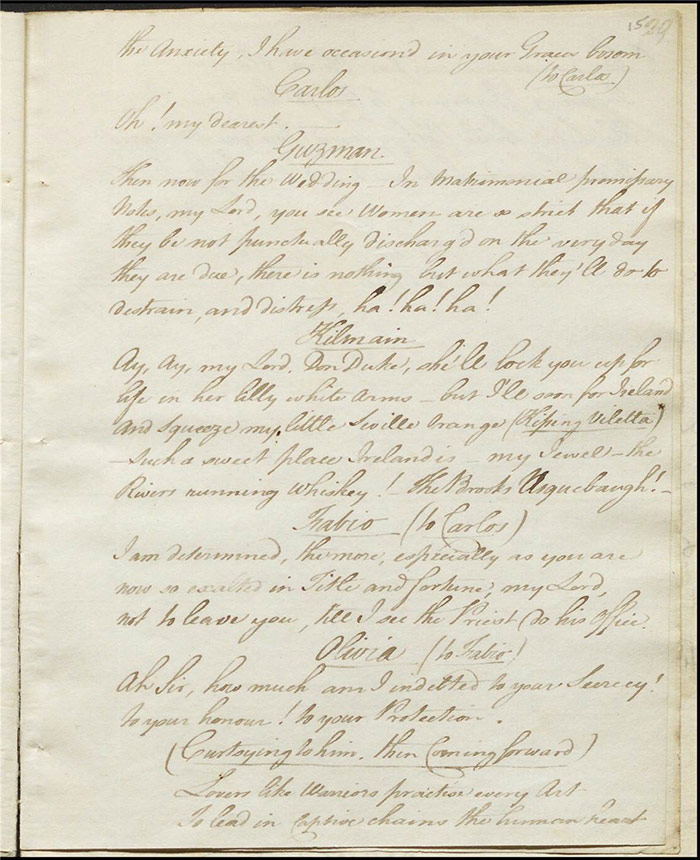

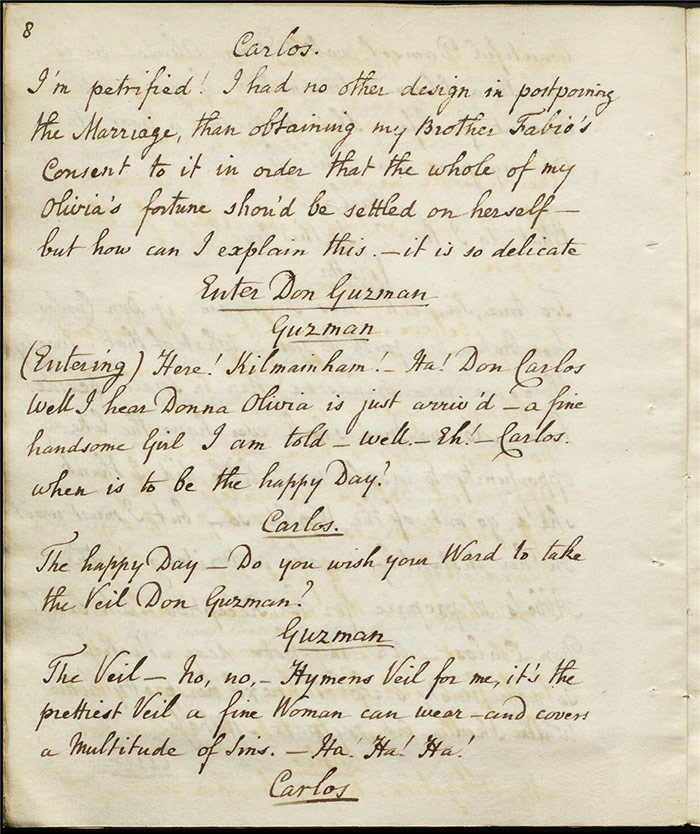

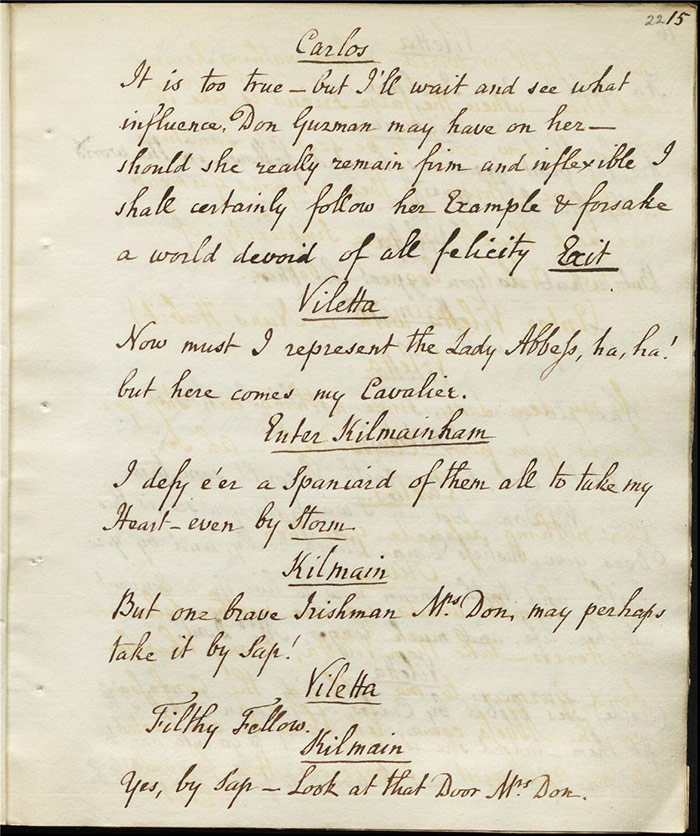

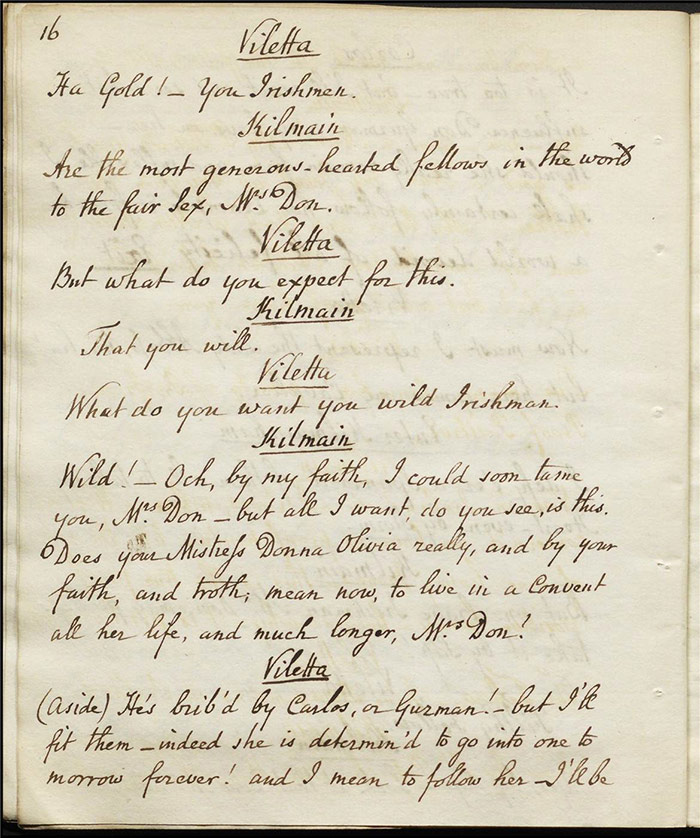

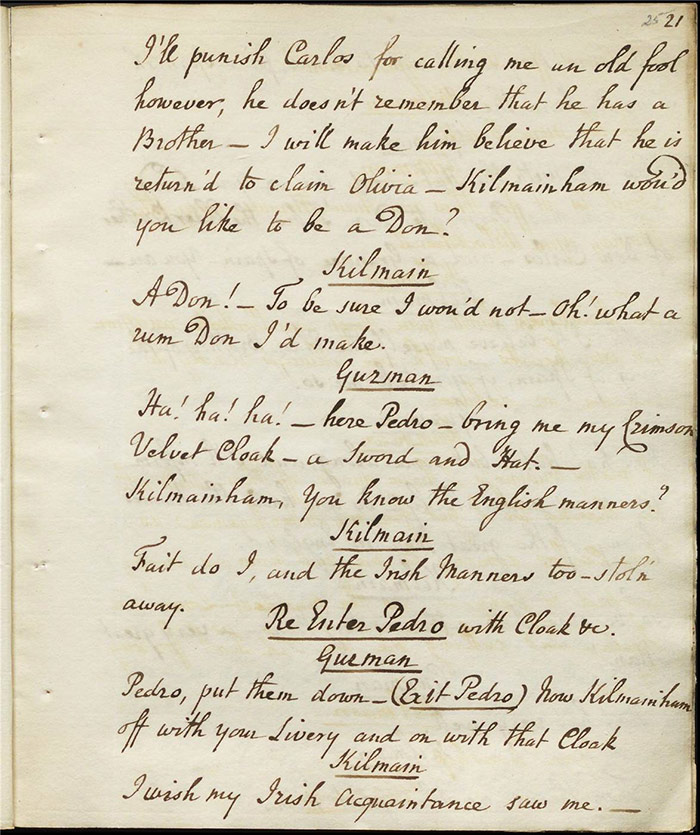

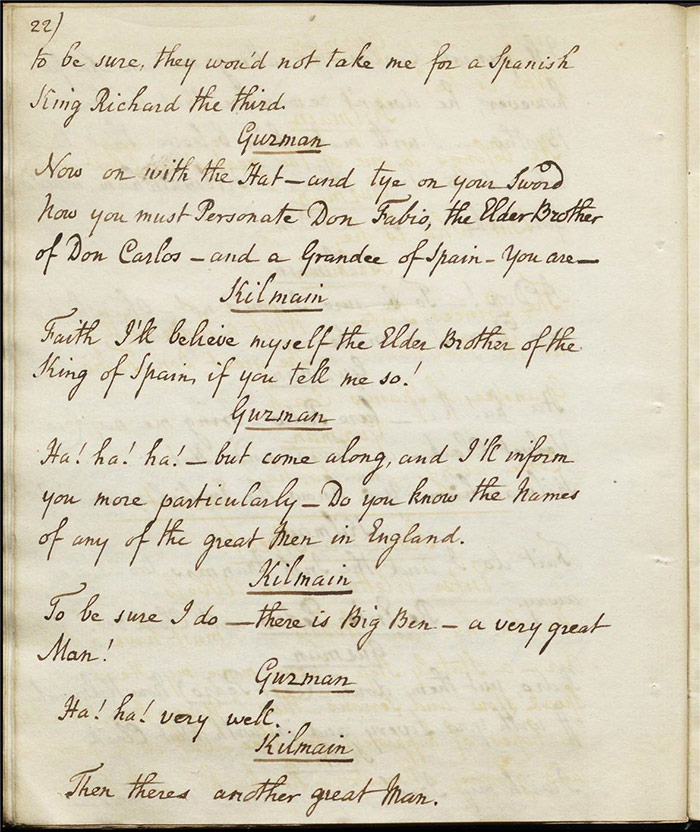

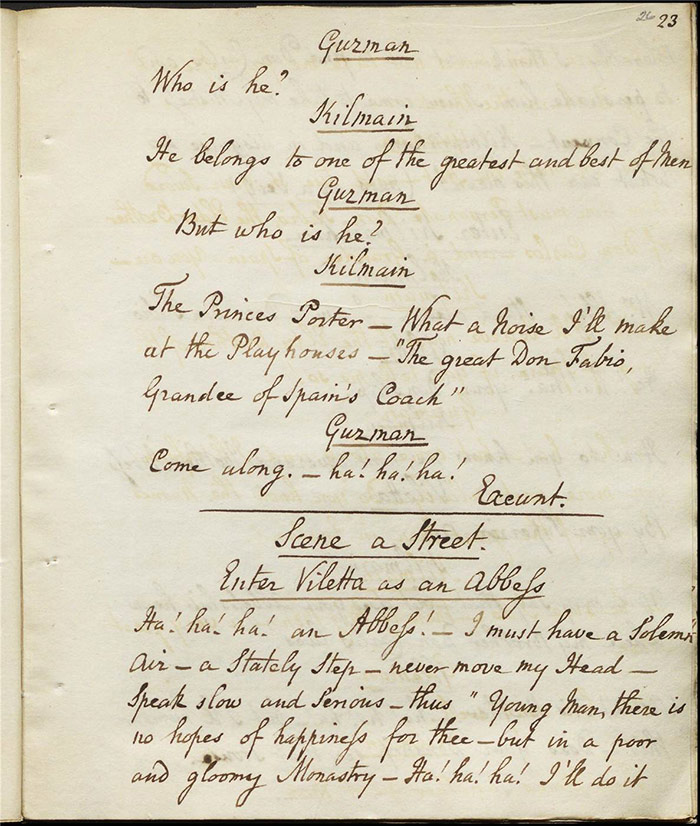

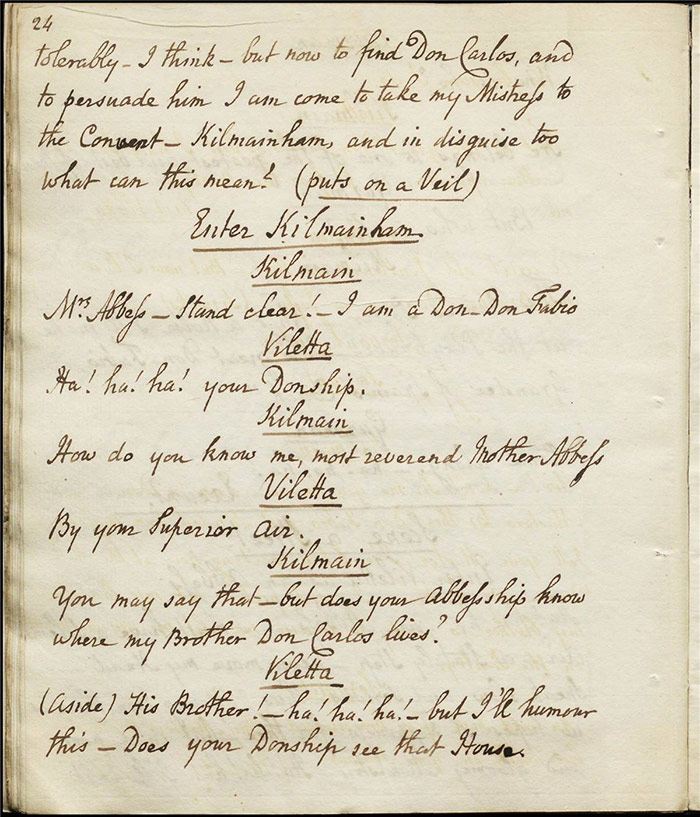

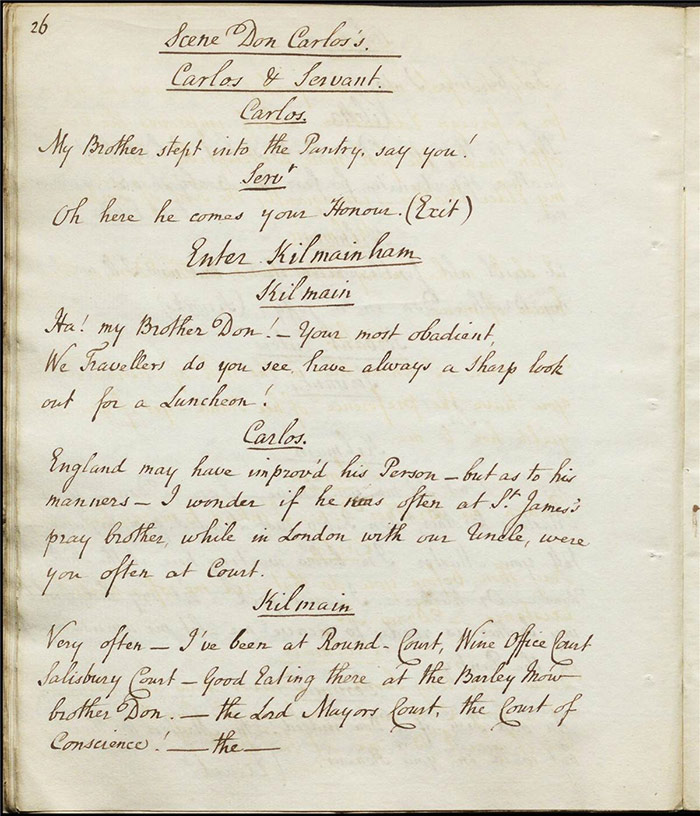

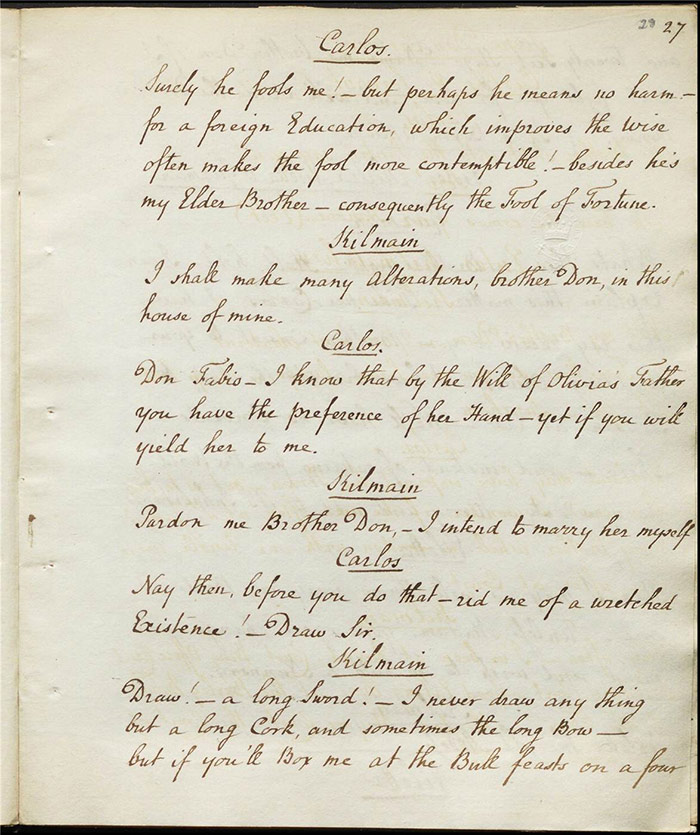

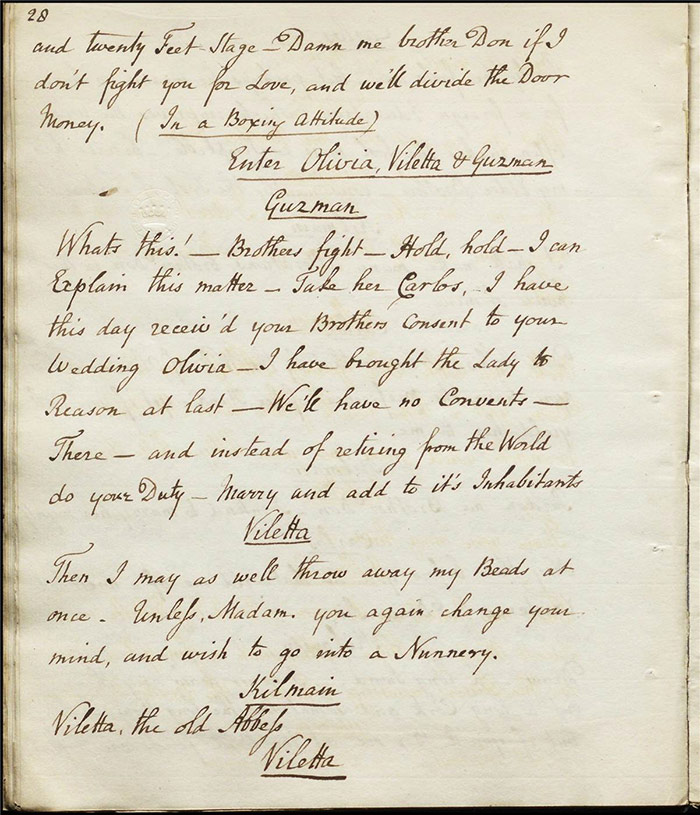

Don Guzman, deciding to have some fun at the start of the second act (f.8r), dresses up Kilmainham as a Spanish nobleman and introduces him as Don Fabio to Olivia. His stage Irish bluster, however, betrays the deceit and she berates Don Guzman. He tells her he will now put pressure on Don Carlos to fulfil his promise of marriage or give her up. Don Guzman and the real Don Fabio—returned from England—praise the English constitution, although Don Fabio observes ‘it may want some slight repairs’ (f.11r). Meanwhile, Don Carlos has met Kilmainham, still in the guise of Don Fabio. When Kilmainham tells Don Carlos he is in love with Olivia, the Spanish noble draws his sword but is stopped by Don Guzman who identifies Kilmainham as his servant. Don Fabio promises Olivia his help and the final scene sees Don Carlos commit to the marriage. He also hears word that his uncle is dead and he is now a duke, making Olivia a duchess.

Performance, publication and reception

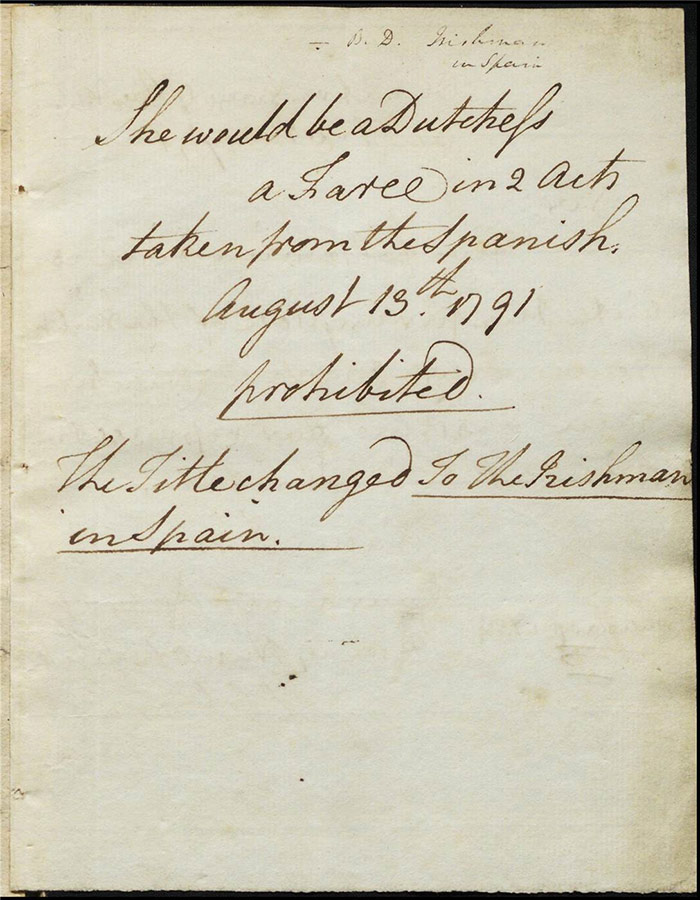

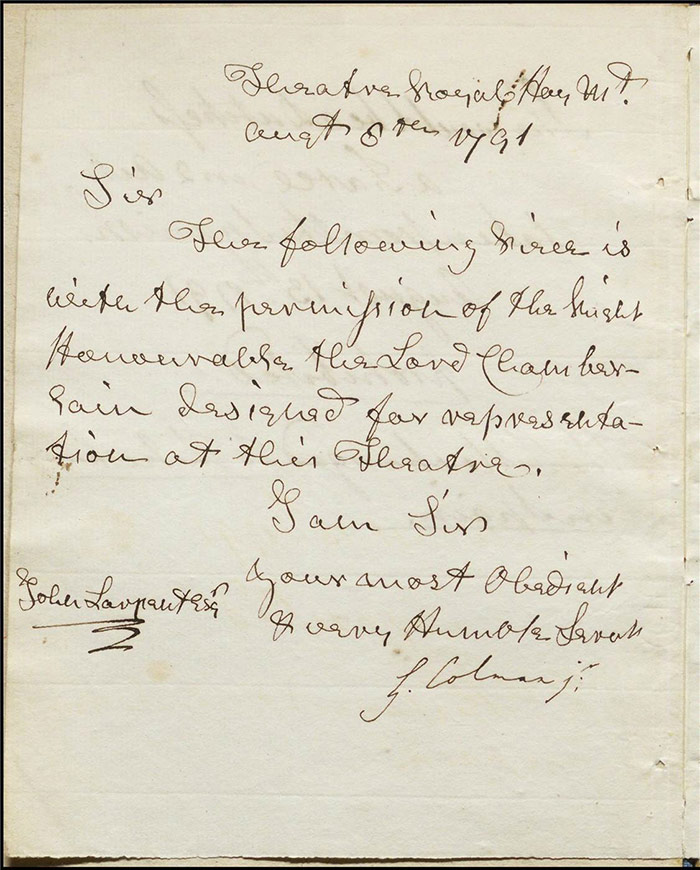

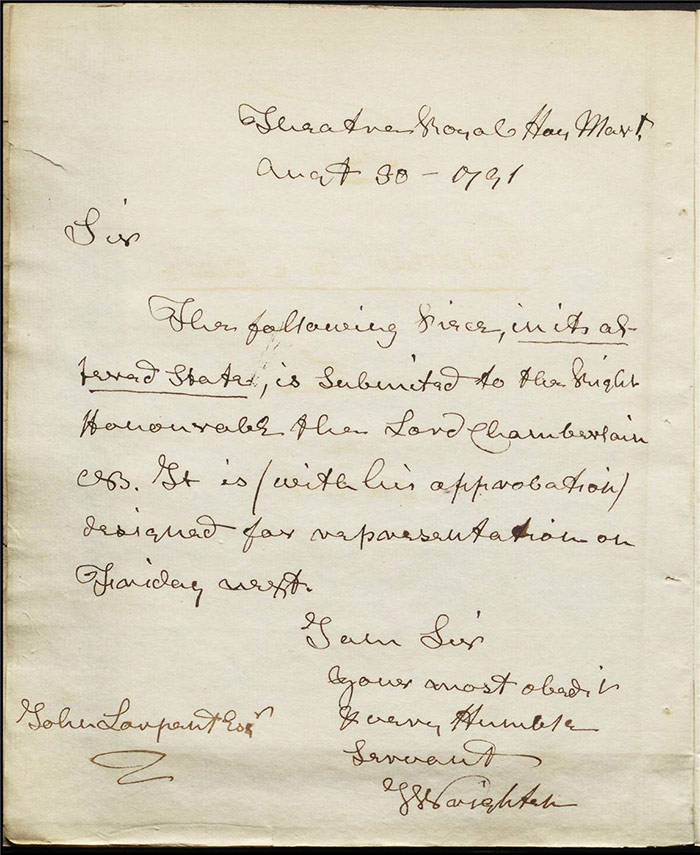

The manuscript for She would be a Duchess was submitted by George Colman on 8 August 1791; Larpent refused it a licence on 13 August. However, the play was nonetheless staged on the night of 13 August at the Haymarket; it is possible that Colman did not receive Larpent’s verdict and, blithely assuming all was ok, went ahead. It is also possible, given the sensitivity of the subject matter, that a hastily cut version was performed that evening and further performances delayed until the licence was received. There is some circumstantial evidence from the newspaper reviews to support both readings. The play, retitled The Irishman in Spain,was resubmitted to the Examiner on 30 August and officially approved. There were three subsequent performances that season on 2, 3, 9 September.

The reviews are unanimous in dismissing the piece as inconsequential. Many of them attribute the poor quality of the drama to the intervention of General John Gunning (see ‘Commentary’) and profess a degree of sympathy for the author.

The Public Advertiser (15 August 1791) was delicate regarding the Gunnings and gently outlines that the play was ‘originally founded on some topics that have of late engrossed much of the conversation of the fashionable world’. Yet it is unequivocal on the effect of the censorship: ‘Under these circumstances, it would be unfair to make any observations on the FARCE, in the mutilated state it was exhibited to the public on Saturday evening. It created some laugh [sic], and some disapprobation’.

The Star (15 August 1791) was not so reserved, informing its readers that the play ‘alarmed the feelings of General GUNNING; in consequence of whose interference the piece was considerably altered, and its title changed’. As a result, the paper suggested that it was unfair to ‘treat the farce with any sort of critical severity’ even if ‘The audience expressed such pointed disapprobation, that the piece was not announced for another representation’.

The only newspaper to bring the broader politics of the 1790s into its assessment was The World (15 August 1791). After snorting that ‘There was nothing that deserves the name of plot!’ in the play, it stated disapprovingly that

The introduction of politics into dramatic composition was pointedly reprobated. Don Fabio was to have pronounced an eulogium upon the British Constitution—he said it was a glorious fabric, but wanted some repairs—the people thought otherwise, so shut his mouth forever.

The Evening Mail (12-15 August 1791) was the most critical of the newspapers in terms of challenging Gunning’s alleged interference. The newspaper’s sense of outrage at the General’s ‘pruning knife’ is palpable; in a passage positively dripping with incredulity, it bemoaned:

[…] wherever a word occurred which might be construed to allude to any one circumstance relative to his daughter’s affair,—such as Duchess, Duke, Marquis, matrimony, ambition, affadafits, novel writing, building castles in the air, love or hatred,—it was swept from the face of the page: so that the author, when his mangled bantling was returned, could scarcely trace one of the child’s former features.

The play was published in 1792 with a bitter preface from the author that complains that what he was left with after the Lord Chamberlain and Gunning had their way was ‘but a hasty mutilation of a Farce’ but he threatens that the play ‘in its original state, shall be published in the course of Winter, with an Address to the Marquis of Salisbury [Lord Chamberlain], and Dedicated to the Gunnings’. There is no evidence that Stuart followed through on this promise.

Commentary

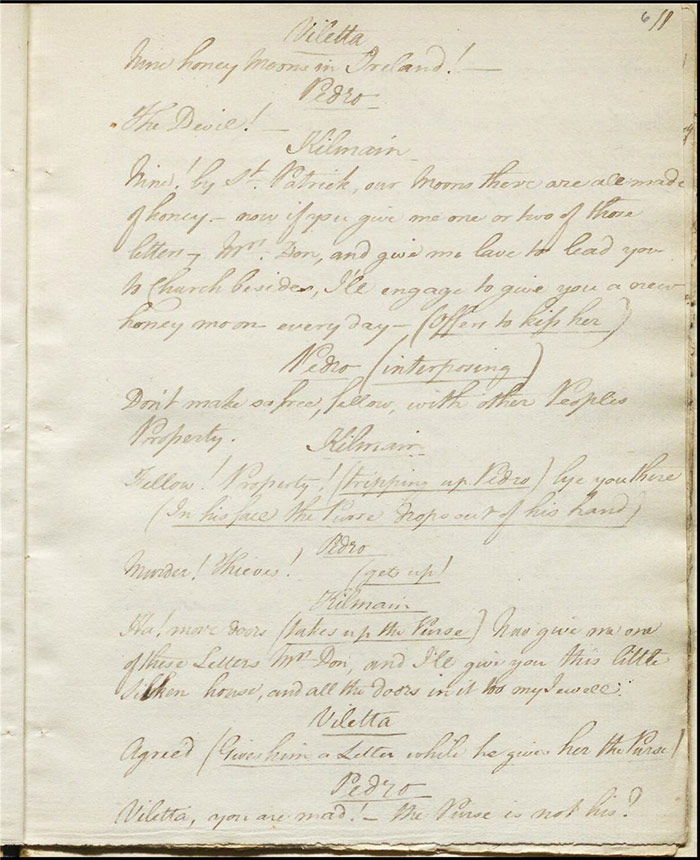

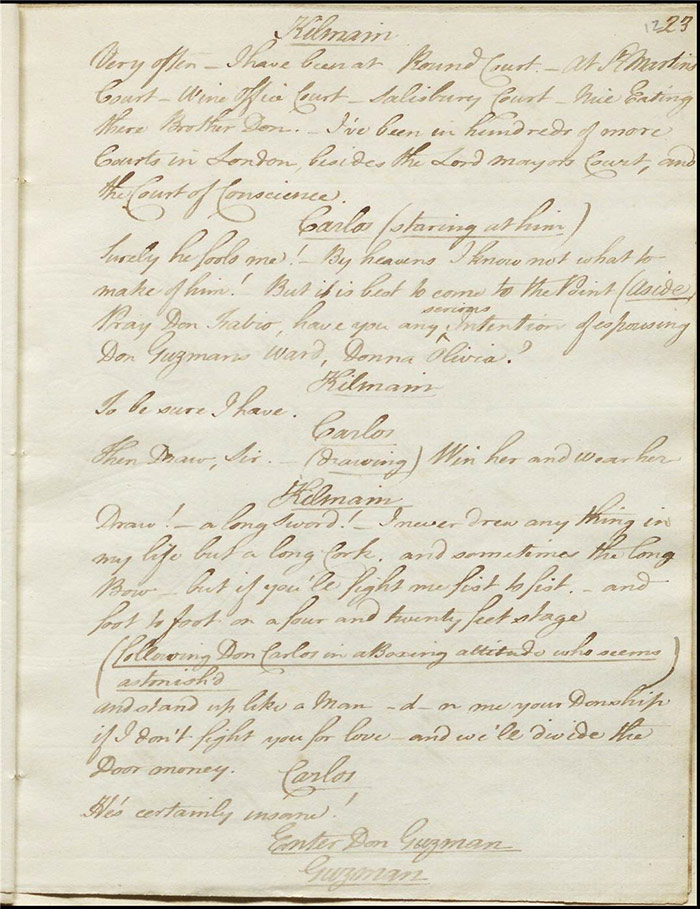

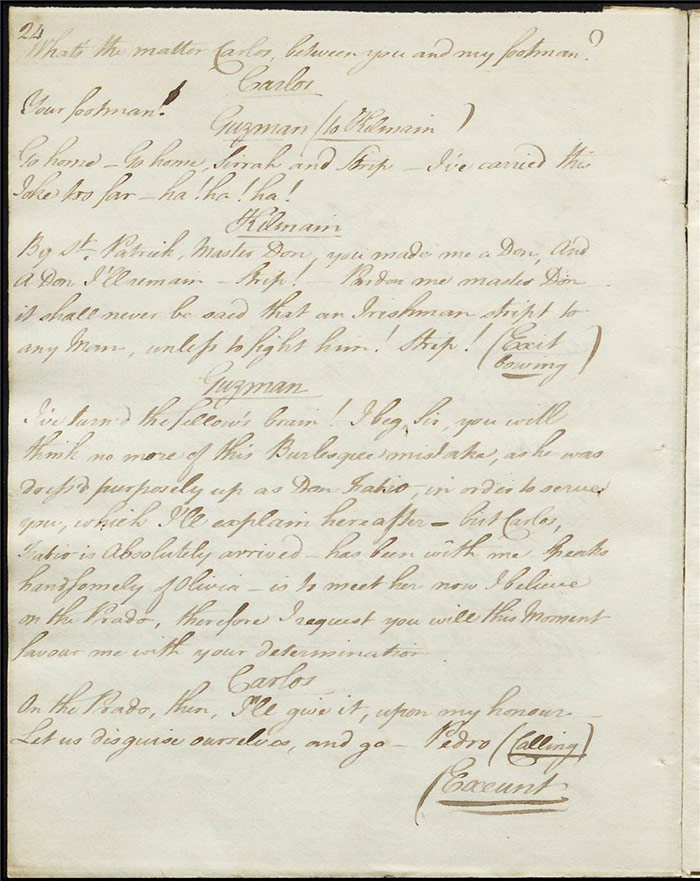

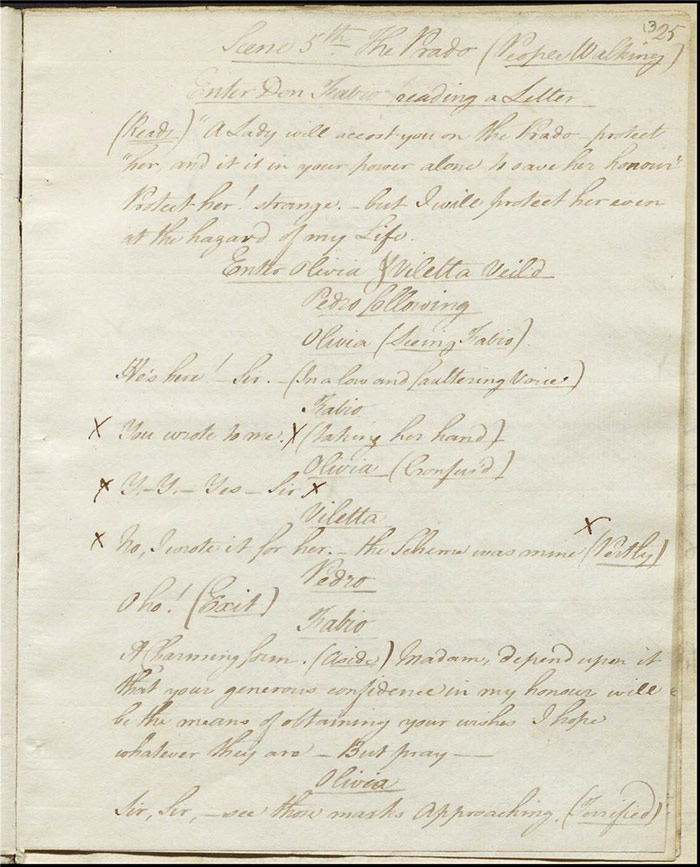

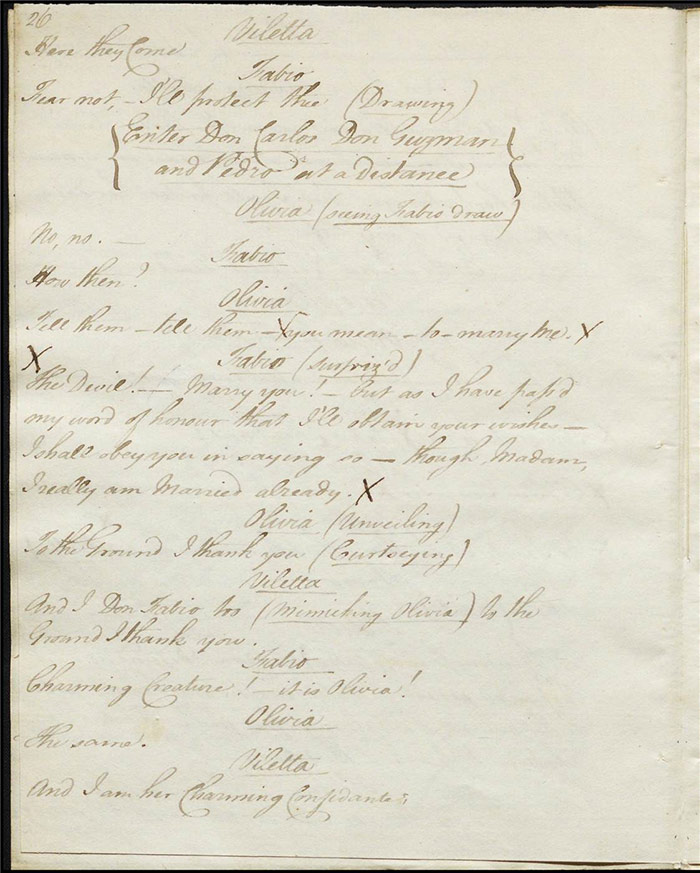

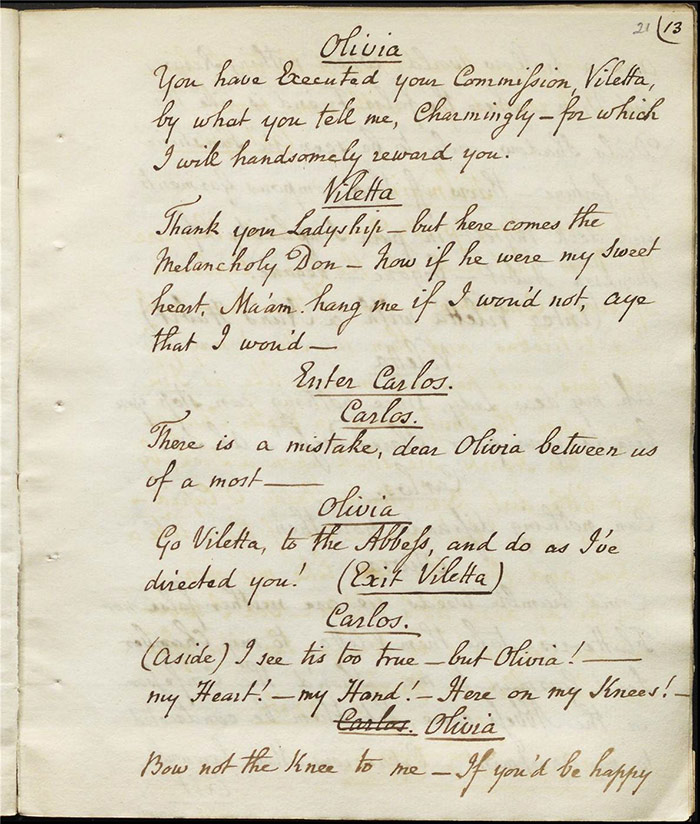

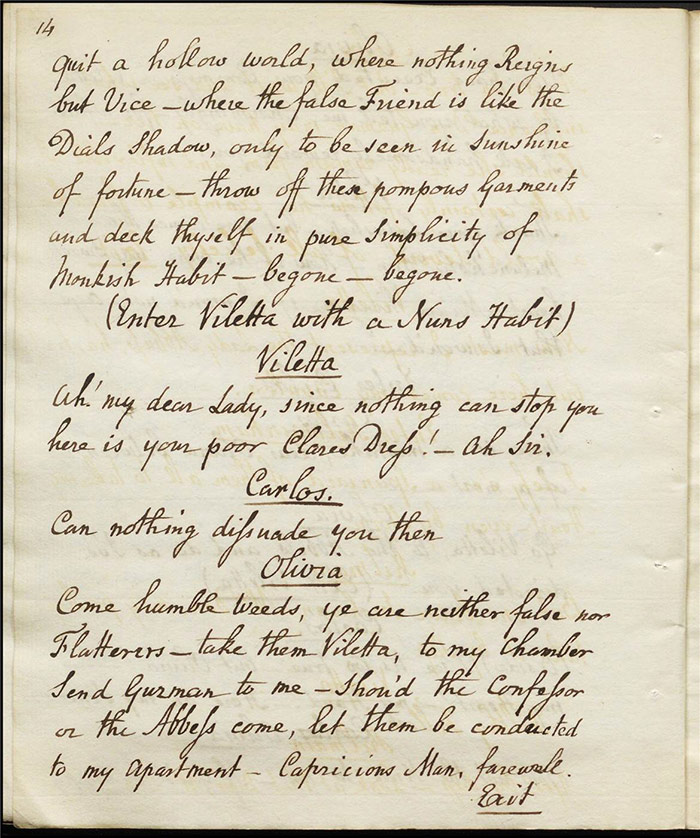

The manuscript (LA 915) shows several emendations marked in pen. Typically, the offending passages are bracketed with two small Xs. This manuscript is of particular interest as the newspapers report that General John Gunning (1742-1797) reviewed the manuscript himself, believing—correctly—that his family was the target of the play’s humour, specifically his daughter Elizabeth Gunning (1769-1823). The Gunnings moved to London in 1788 and by 1790 Elizabeth was rumoured to be of marital interest to the marquess of Blandford, heir to the duke of Marlborough. But a cloud of doubt emerged: letters supposedly from the marquess to Elizabeth were thought to be forgeries produced by either Elizabeth or her mother, Susannah, in the pursuit of an advantageous marriage. Irked by the public ignominy John Gunning evicted his wife and daughter from the house in 1791. Susannah Gunning retaliated in print (see below) and, Essex Bowen, a cousin of John Gunning, responded to her in kind. Elizabeth Gunning used her notoriety to launch a literary career, her first novel The Packet was published in 1794.

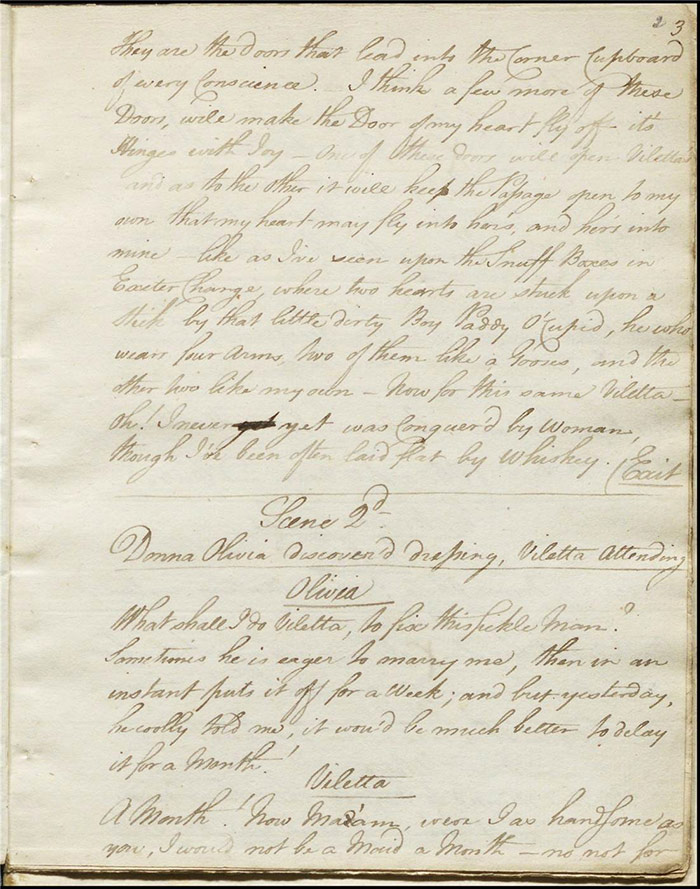

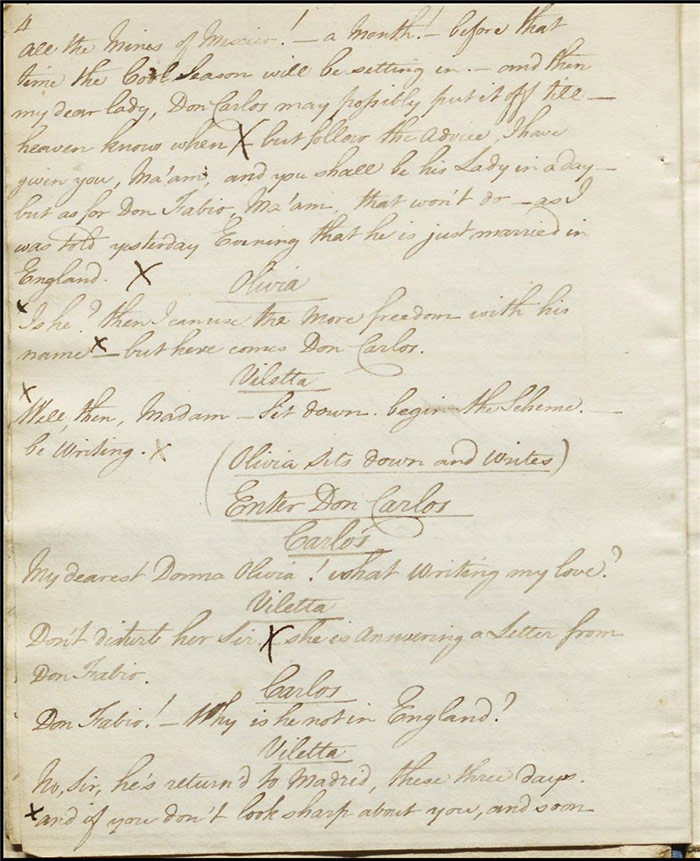

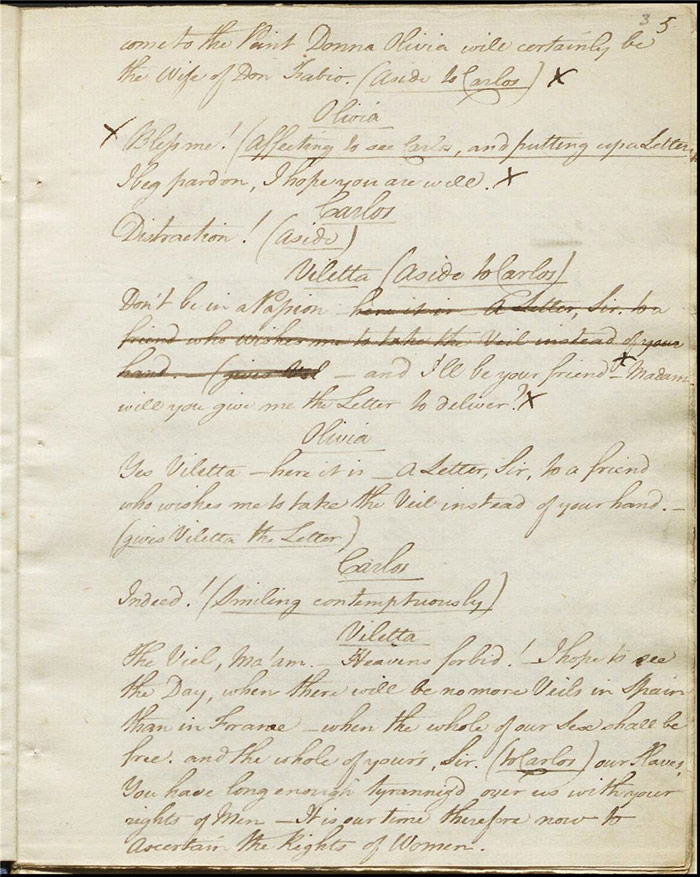

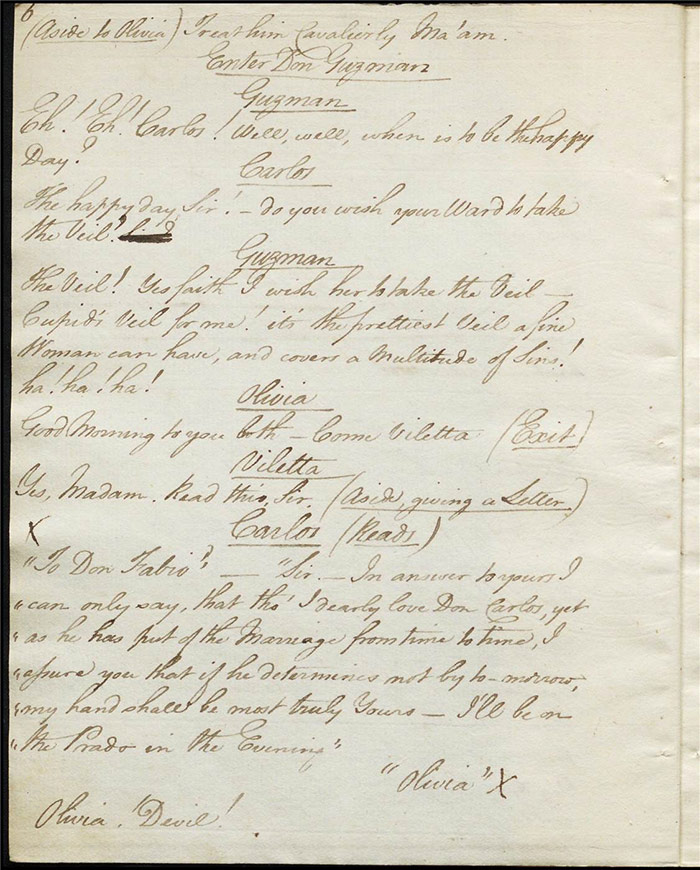

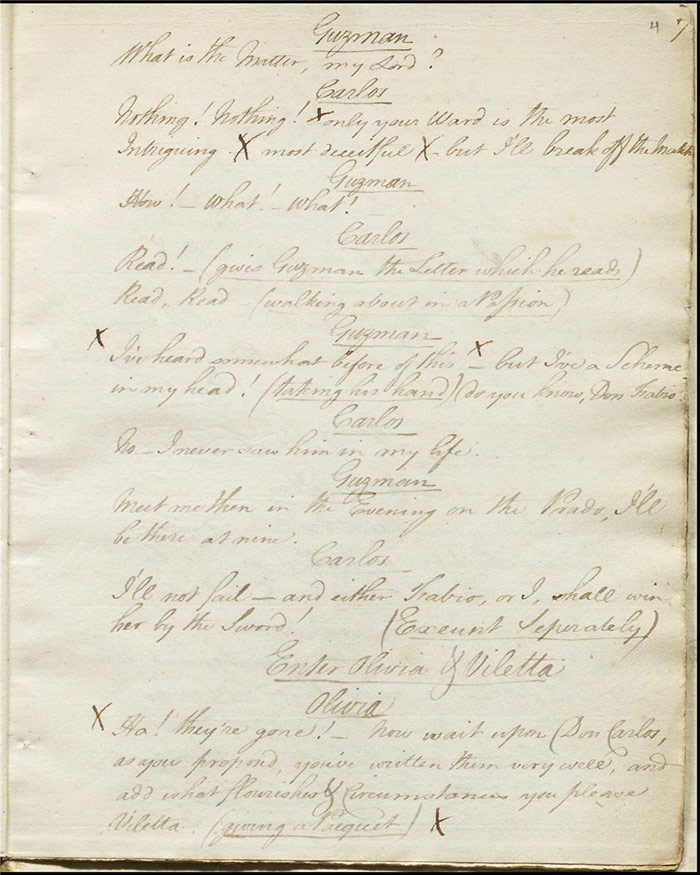

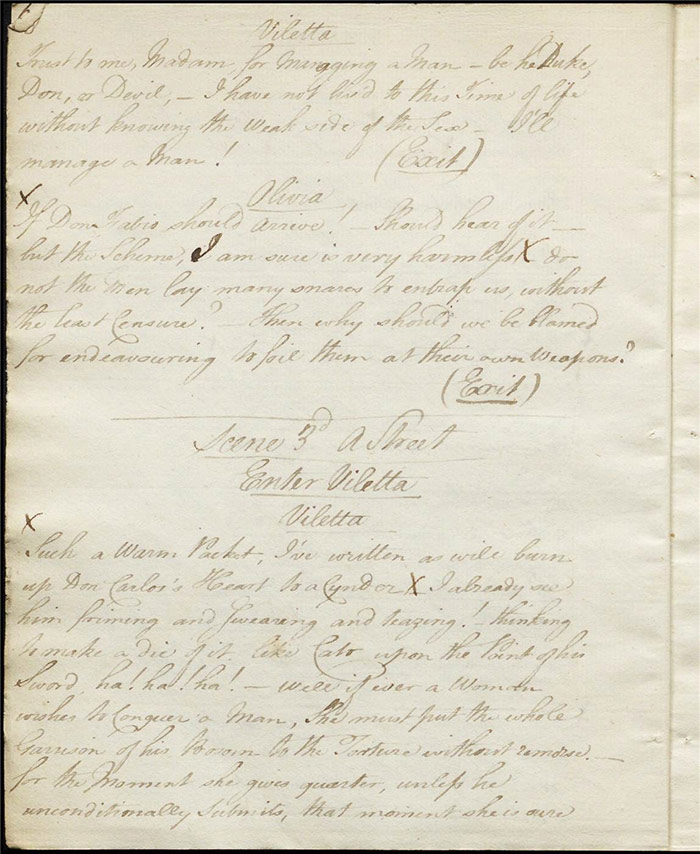

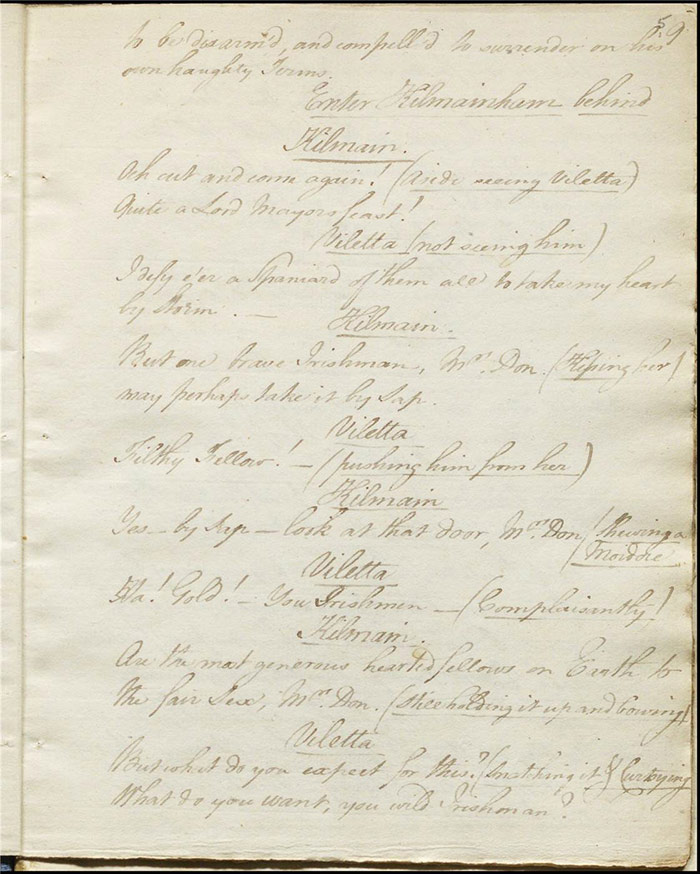

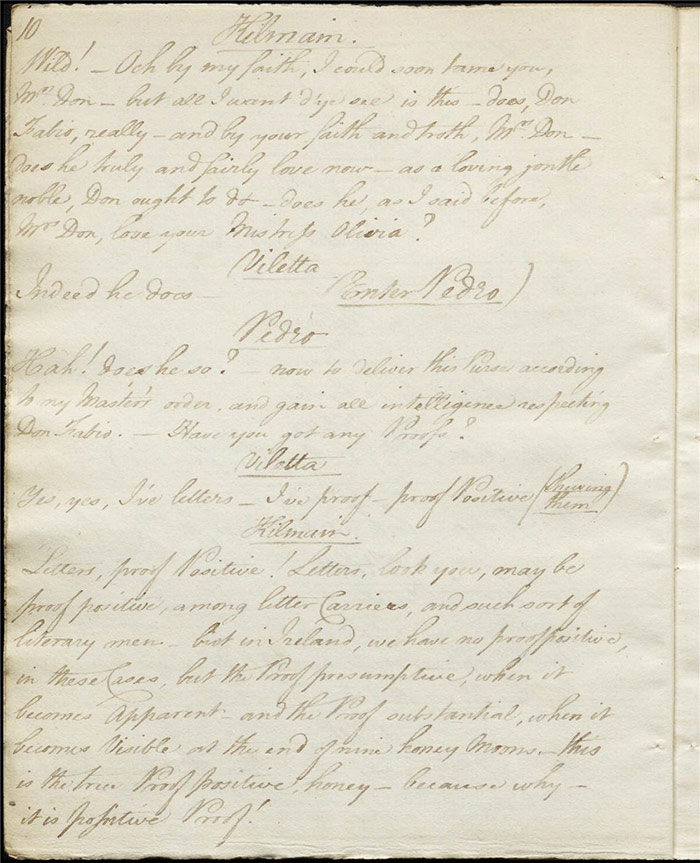

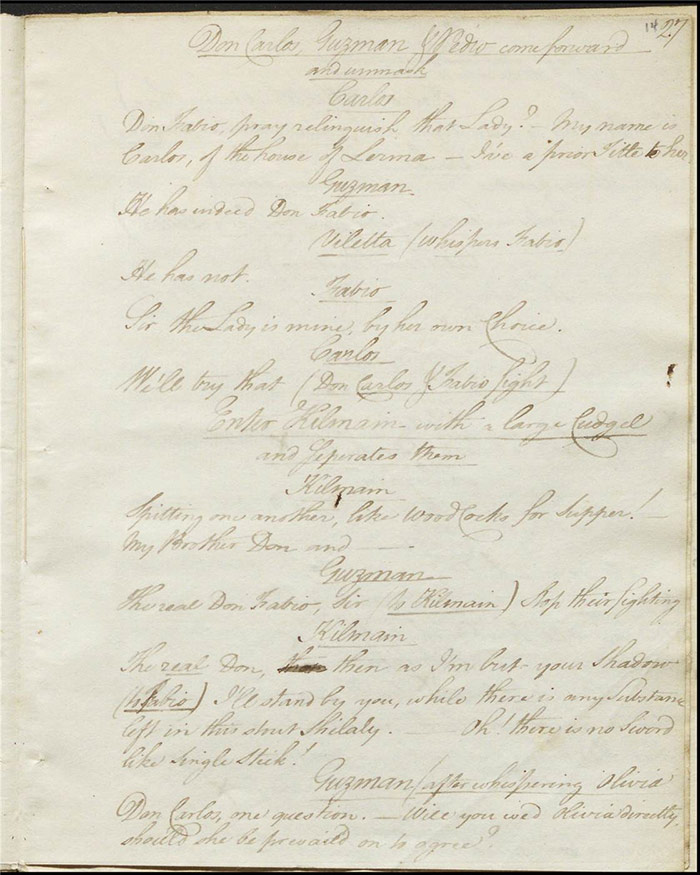

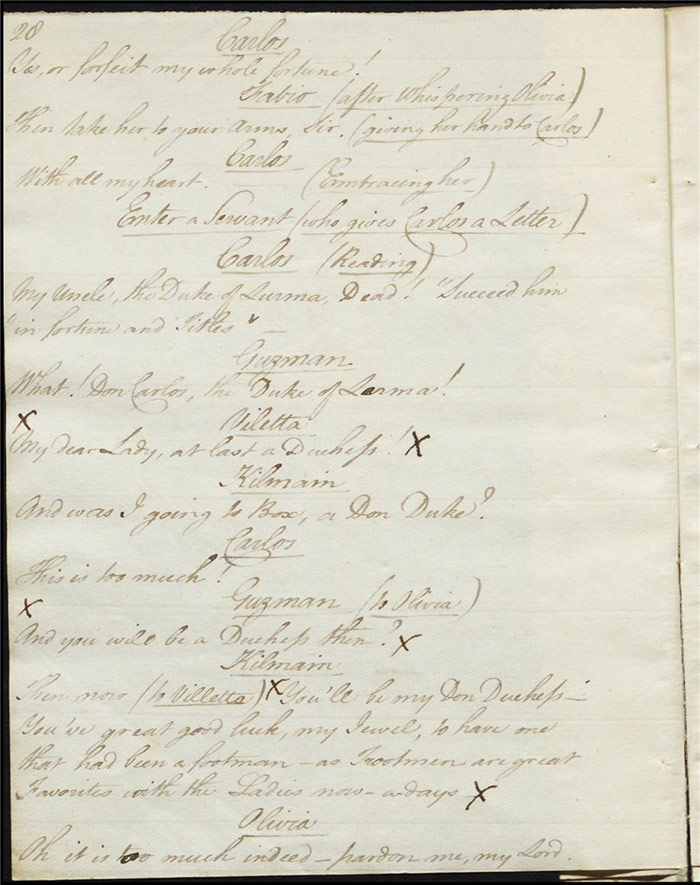

Examining the manuscript, we note that the marking of an objectionable phrase by two Xs is not typical of Larpent – compare, for instance, the penciled underlining of passages in The Hop, or, Who’s Afraid? (LA 903), the most proximate manuscript to this piece. The unusual method of marking up the manuscript may suggest Gunning had direct sight of the play but is not conclusive.

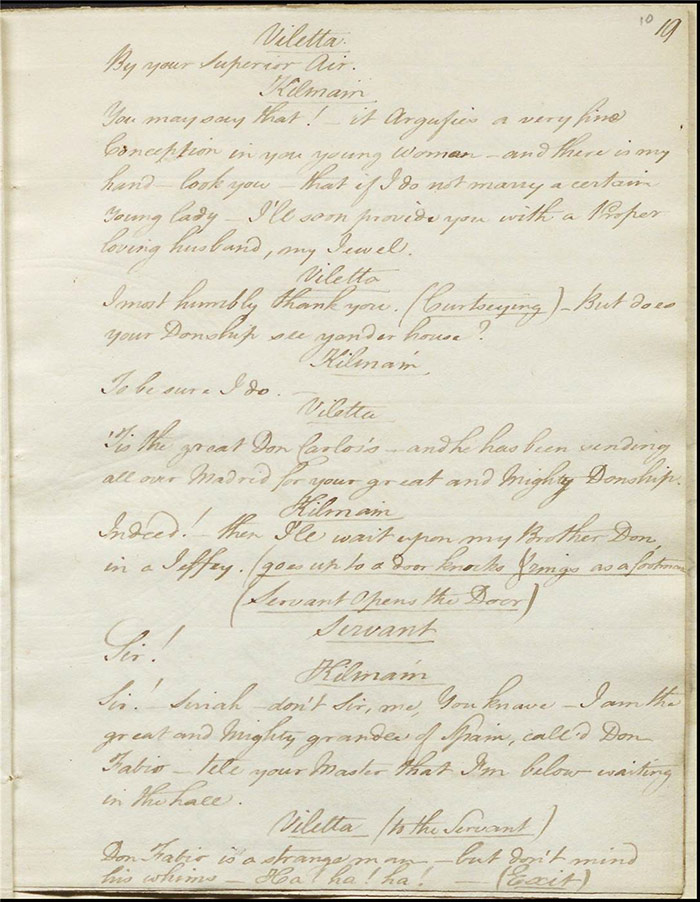

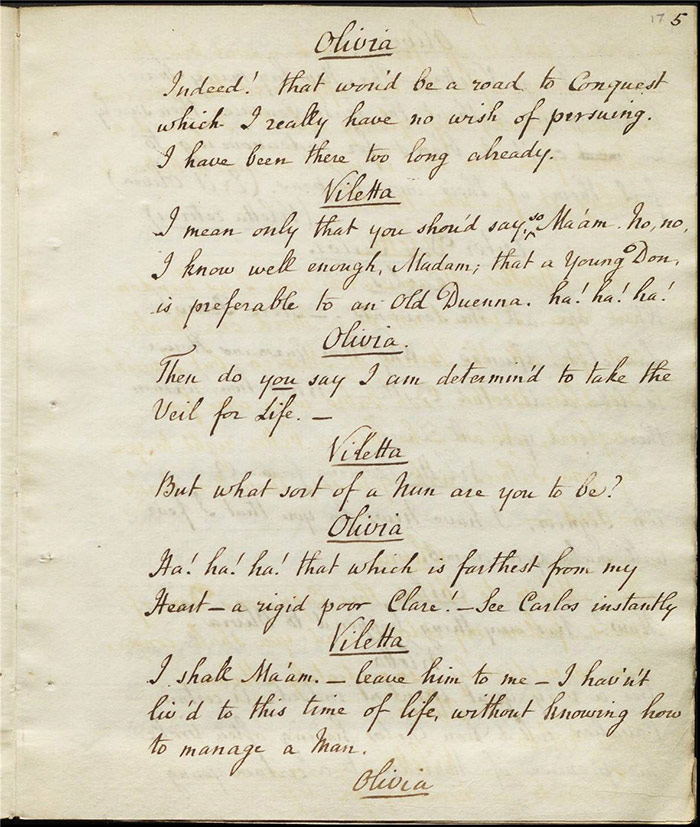

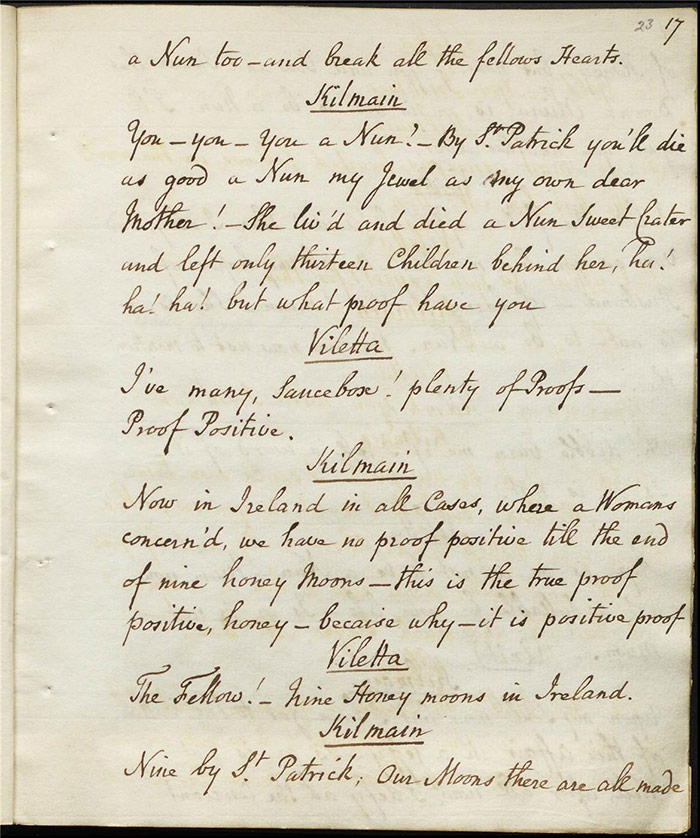

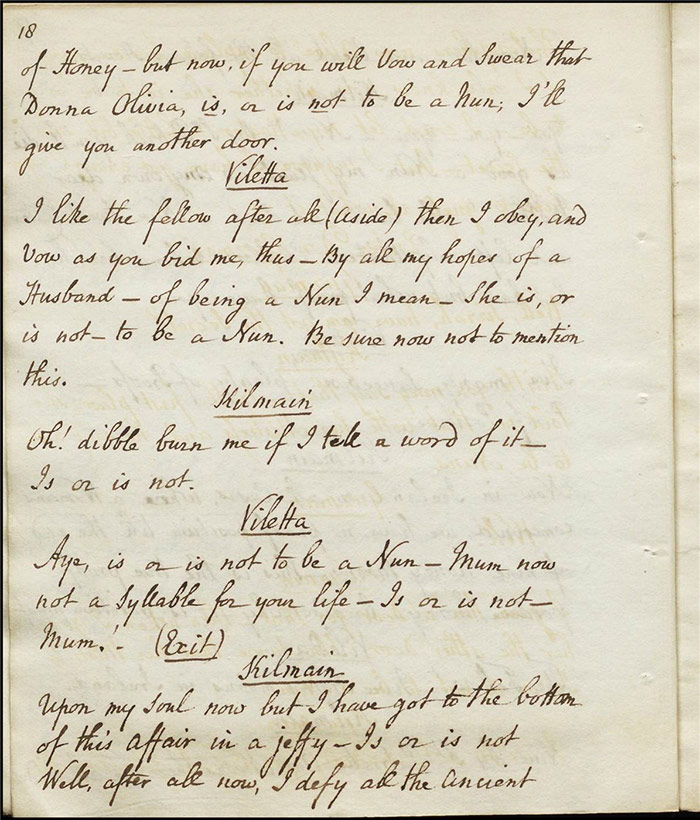

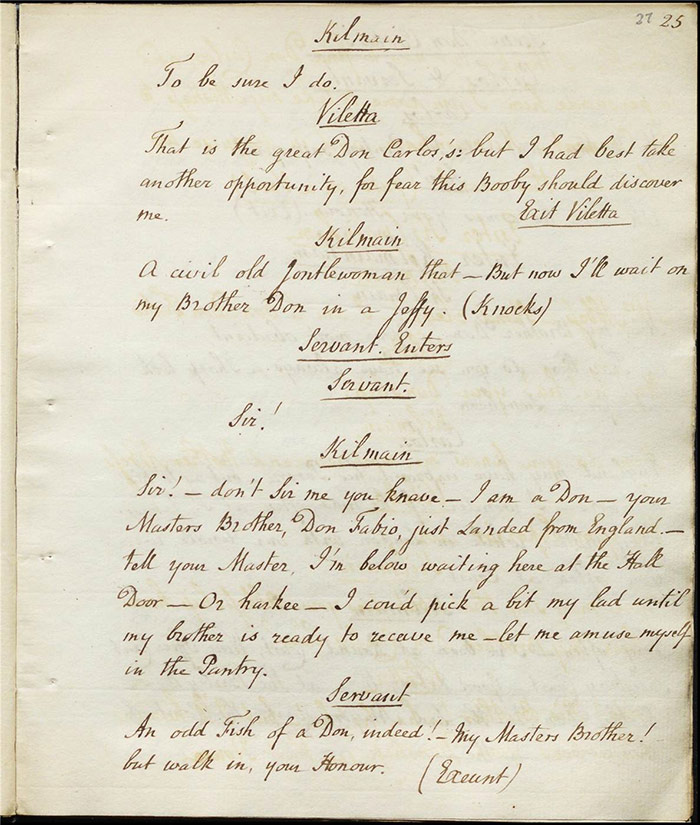

Examples may be seen on (f.2v) where references to scheming letter-writing—or any kind of epistolary activity—are marked for omission. Indeed, on (f.3r) even a stage direction—‘Bless me! (Affecting to see Carlo, and putting up a Letter) I beg pardon, I hope you are well’—was excised such was the degree of sensitivity. Further examples can be seen on (f.3v) and (f.4v).

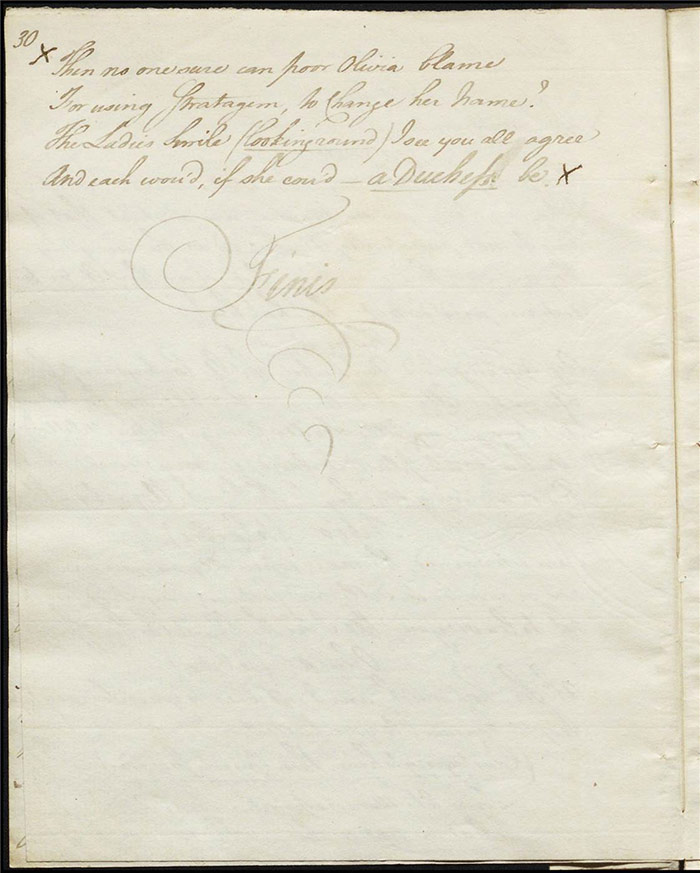

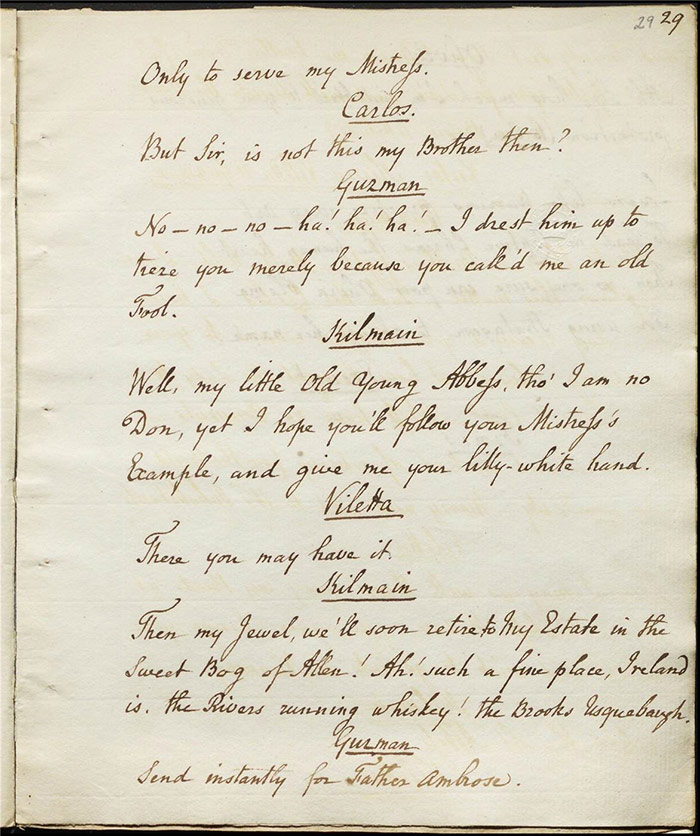

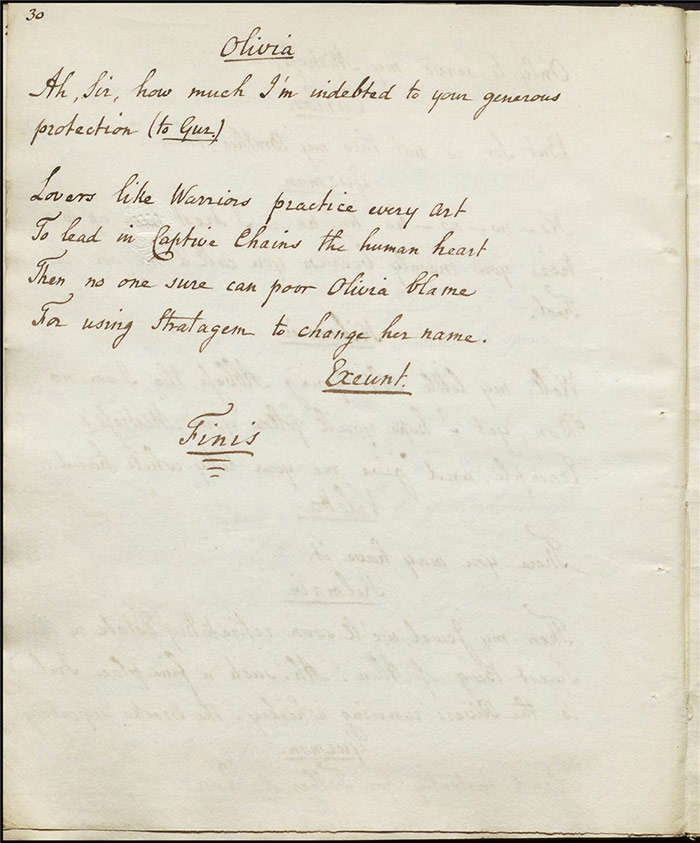

References to becoming a duchess are also systematically excised including the closing lines of the piece:

Then no one sure can poor Olivia blame

For using Stratagem, to change her name?

The Ladies Smile (looking round) I see you all agree

And each wou’d, if she cou’d – a Duchess be. (f.15v)

Guzman’s concern that the antics of the play may lead to a duel (f.11r) are also marked for deletion. Kilmainham’s stage Irish bawdiness, directed at Viletta, is also bracketed with two Xs: ‘You’ll be my Don Duchess – You’ve great good luck, my Jewel, to have one that had been a footman – as Footmen are great Favorites with the Ladies now-a-days’ (f.14v).

Other phrases that were deemed too suggestive for the stage included Don Carlos saying of Olivia ‘only your Ward is the most Intriguing – most deceitful’ (f.4r) and Olivia herself saying ‘I’m detected! betray’d’ (f.8r). One may speculate that, as these phases would struggle to be connected to the Gunning affair without the letter references, that this may indicate some over zealous interference on the part of Gunning. A final piece of suggestive evidence that it was Gunning who marked the manuscript is what he did not remove. When Don Fabio and Don Carlos extol the virtues of England, Don Fabio introduces a note of criticism, admitting that while ‘[The English constitution] is an Admirable fabric’, it does ‘want some slight repair’ (f.11r) which, as the reviews tell us, met with much disapprobation on the part of the audience. It is possible, if not probable, that the experienced eye of Larpent would have removed this mild rebuke in the volatile period of the early 1790s.

In the revised and retitled The Irishman in Spain (LA 917), Olivia threatens to become a nun if Don Carlos does not marry her. The play’s comedy unfolds as they wait Don Fabio’s permission (he is Don Carlos’s older brother in this version but does not appear onstage) for the marriage. The correspondence element of the plot is thus entirely removed. This revised manuscript bears no marks of external intervention.

Further reading

A Narrative of the incidents which form the mystery, in the family of General Gunning (London: Taylor and Co., 1791)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

Essex Bowen, A Statement of Facts in answer to Mrs. Gunning’s Letter (London: J. Debrett, [1791])

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 133-134.

Isobel Grundy, ‘Gunning [married name Plunkett], Elizabeth (1769-1823)’

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004;

online edn, May 2015 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17622, accessed 23 April 2018]

Susannah Gunning, A Letter from Mrs. Gunning, addressed to His Grace the Duke of Argyll (London: Ridgway and Boyter, 1791)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

________Virginius and Virginia (London: Minerva Press, [1792])

Charles Stuart, The Irishman in Spain (London: printed for J. Ridgway, 1791)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online and Google Books]