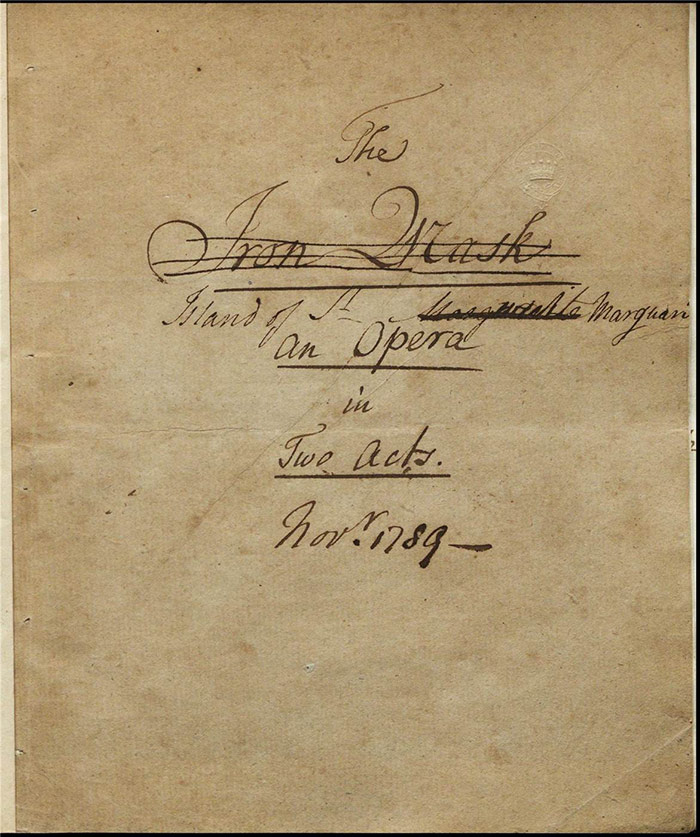

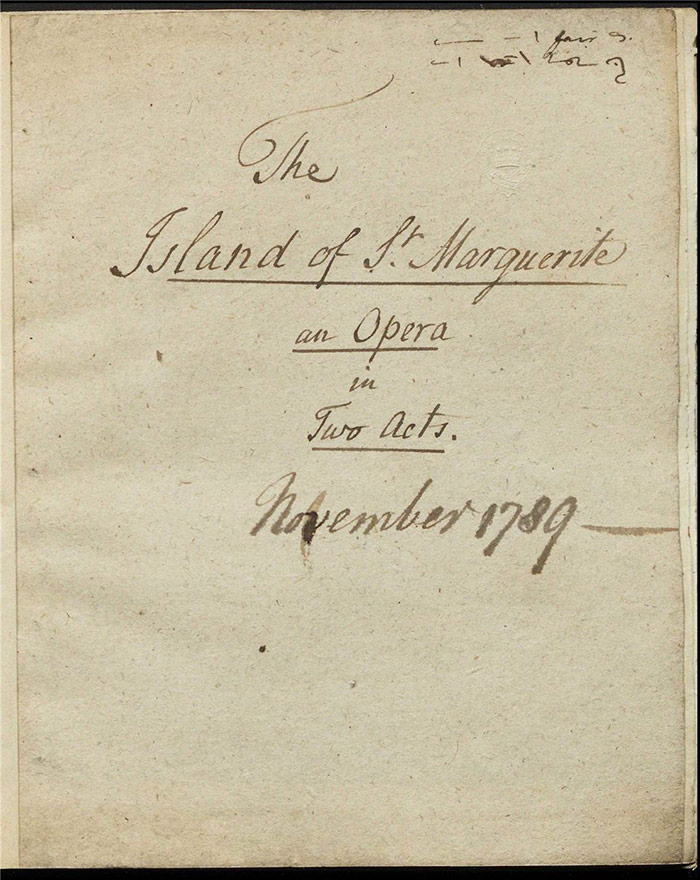

The Island of St Marguerite (1789) LA 845 / 848

Author

John St. John (1754/6-1793)

St. John was a politician and the nephew of the first Viscount Bolingbroke, Henry St. John. After his education at Eton and Oxford, he entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1765 and was subsequently called to the bar in 1770. He then pursued a political career, entering the house in 1773 as MP for Newport, Isle of Wight, and supporting the North administration. However, he was not a highly regarded parliamentarian. George Selwyn, describing one of his earlier speeches, wrote: ‘Our poor counsellor was a long while in the mud. He took too large a field upon a dry subject, the coinage ... He was sometimes out, and very dull through the whole’. James Hare noted meeting him in Paris in 1783: ‘St. John is by many degrees more stupid and ridiculous than he is in England’ (History of Parliament Online). Despite the wide agreement regarding his considerable limitations, he became surveyor of the crown lands in 1775, later publishing Observations on the Land Revenue of the Crown (1787). He exited politics in 1784. In March 1789, his first play Mary, Queen of Scots was staged at Drury Lane with reasonable success, having 9 performances. This was followed later that year—and after the events of 14 July in Paris—by The Island of St. Marguerite. St. John later published A Letter from a Magistrate to Mr. William Rose, of Whitehall, on Mr. Paine’s Rights of Men (1791); his assessment that ‘Mr. Paine’s Pamphlet is an extraordinary instance of an explicit proposal for the subversion of the whole system of Laws, Government, Constitution, and Principles of the Nation’ (12) gives a sense of his political inclinations. He died shortly afterwards in London in 1793. .

Plot

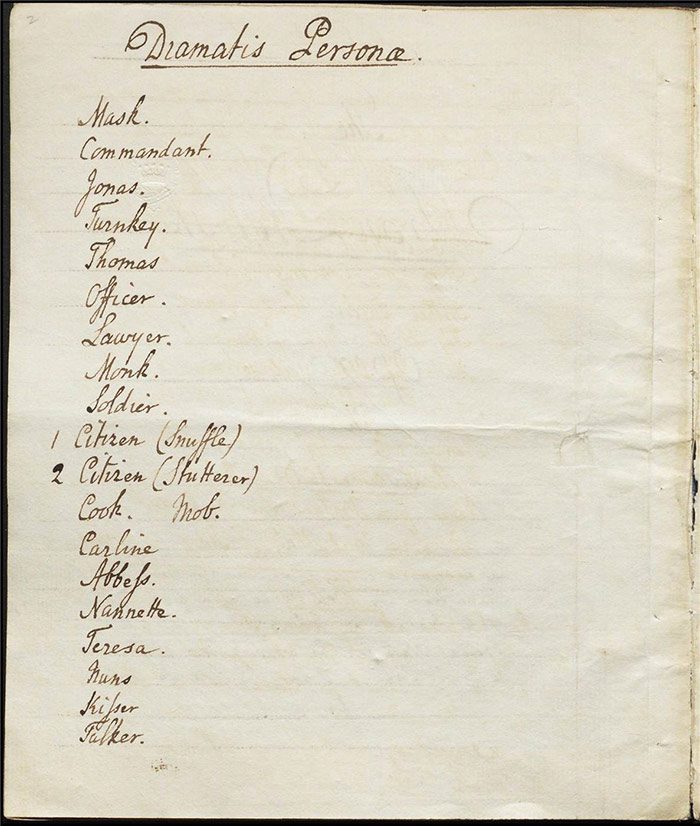

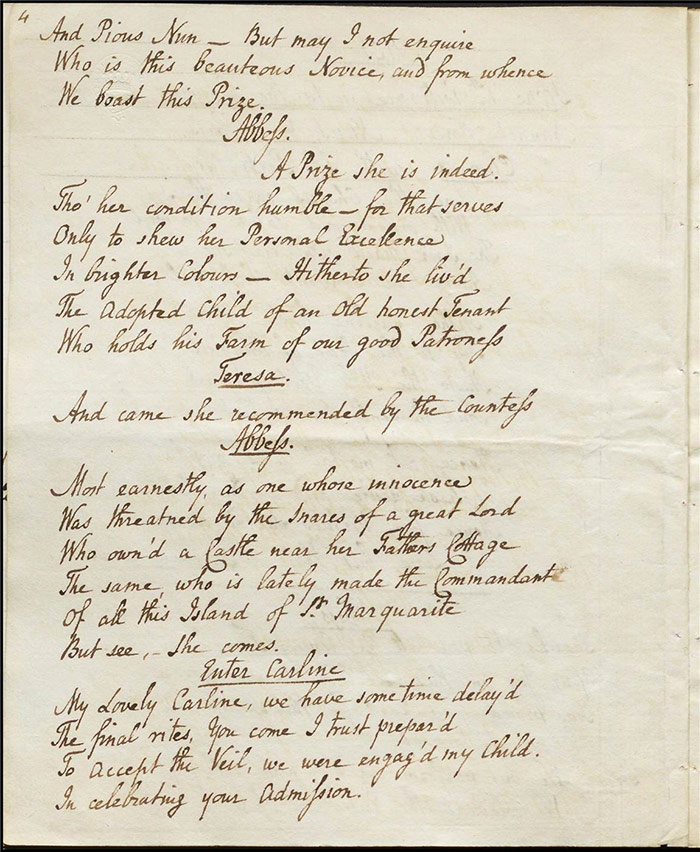

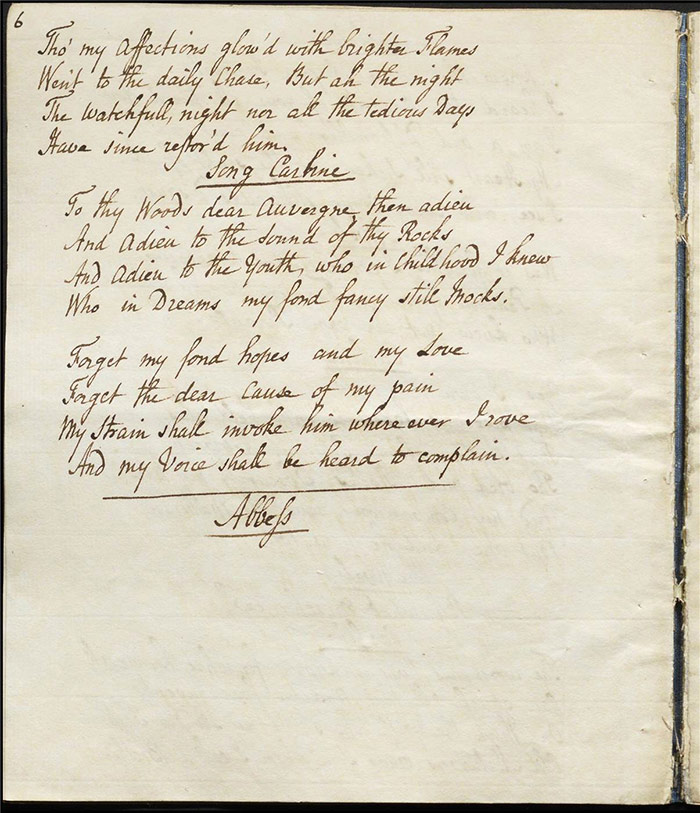

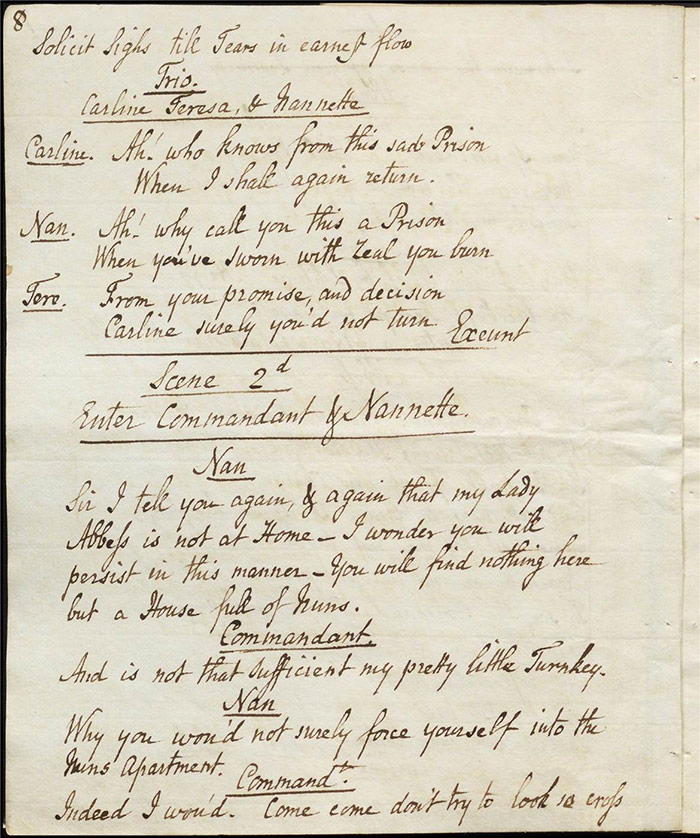

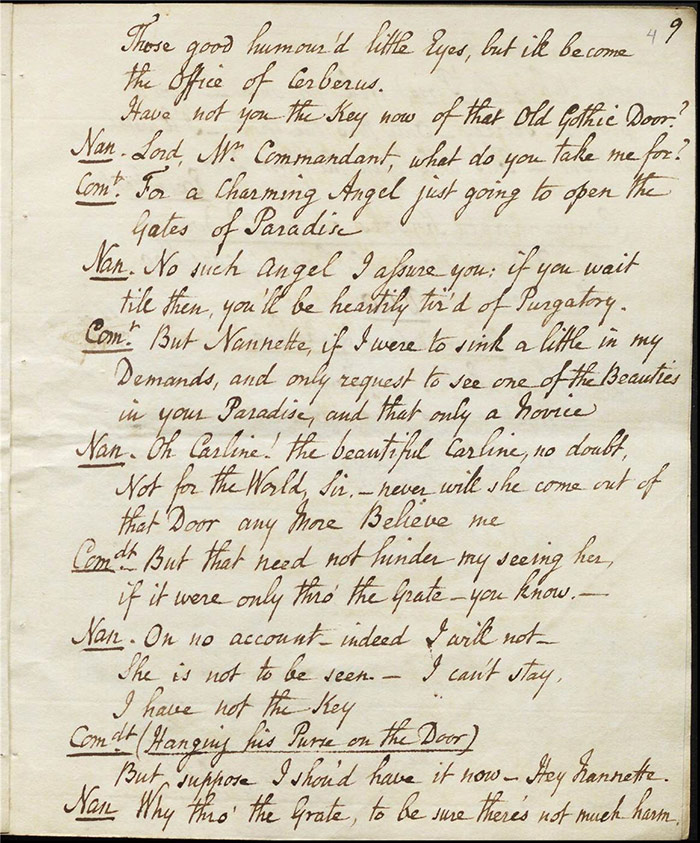

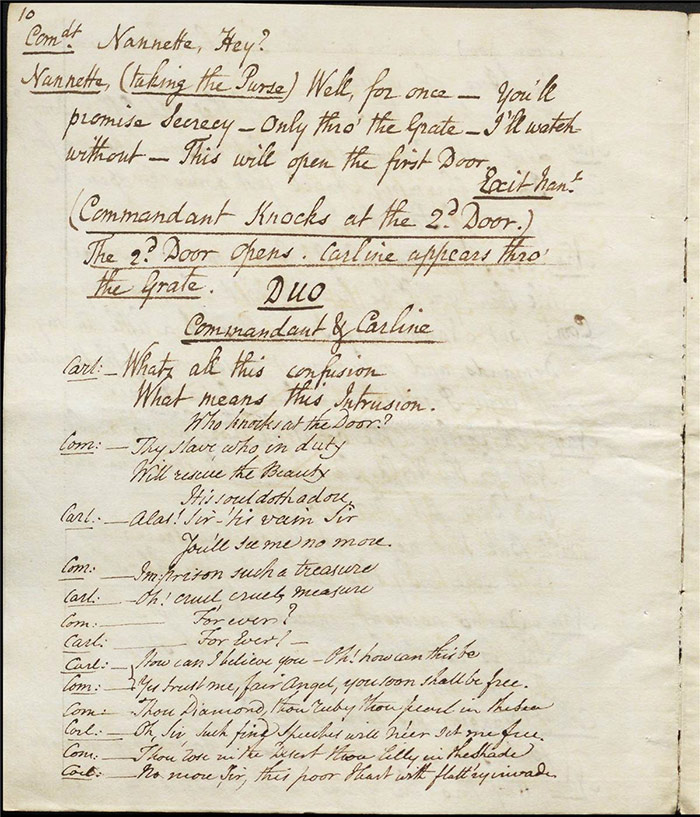

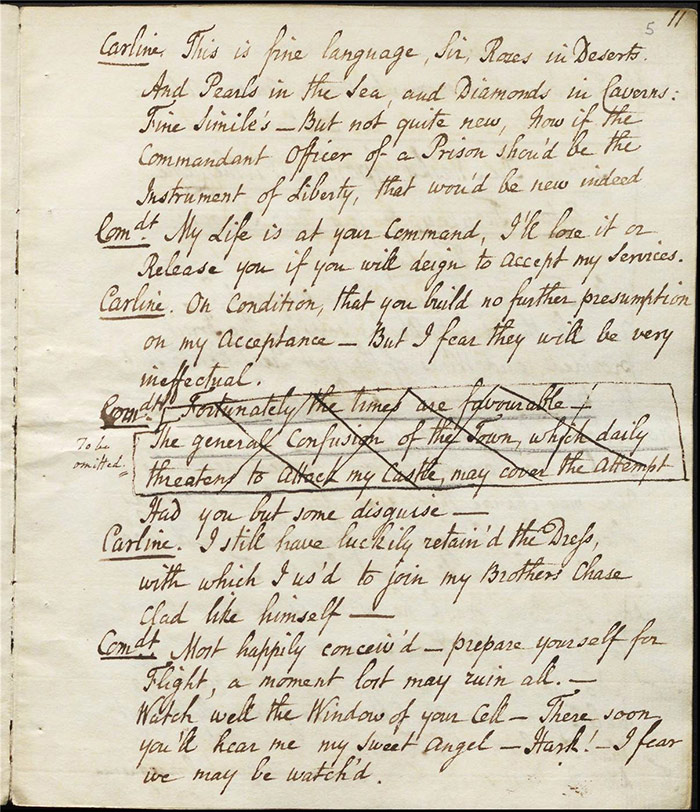

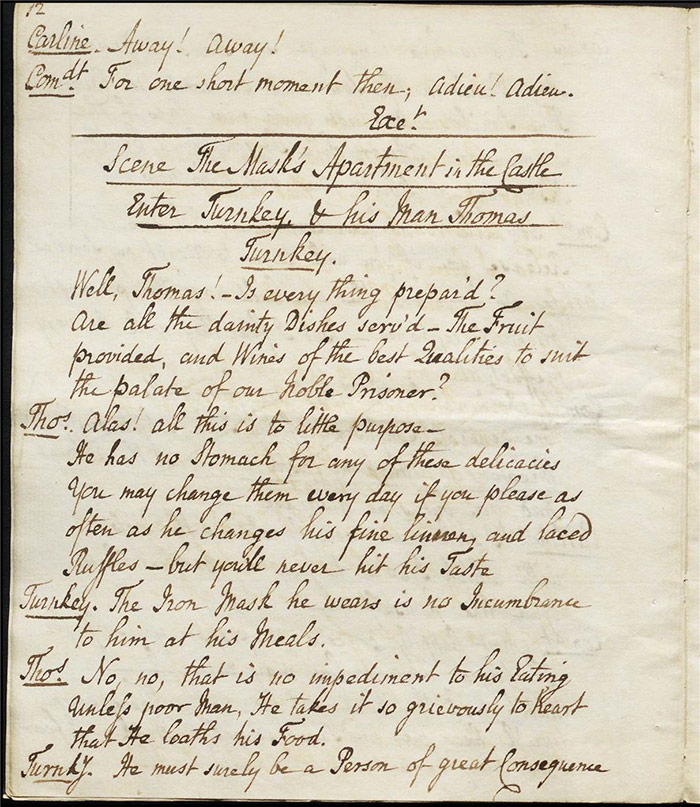

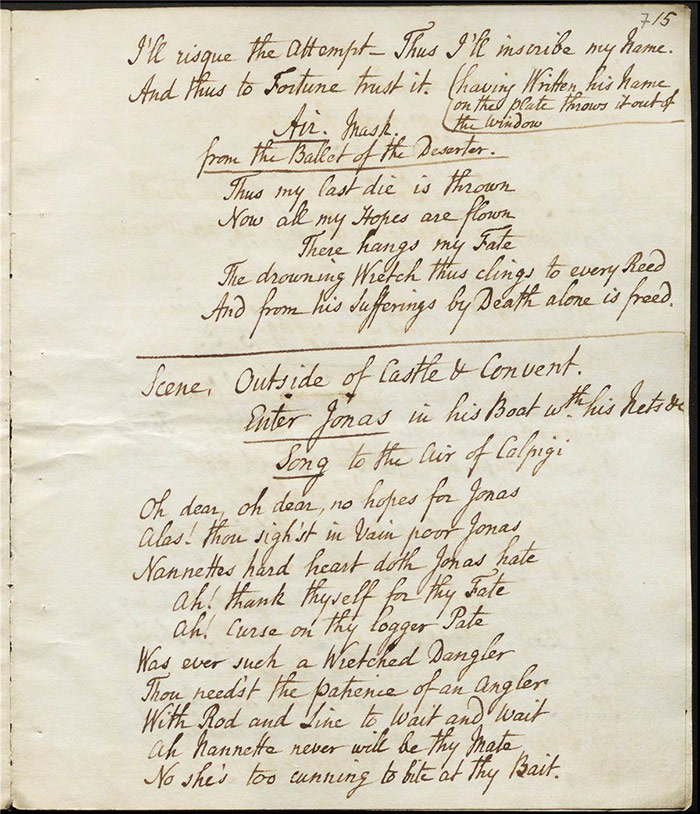

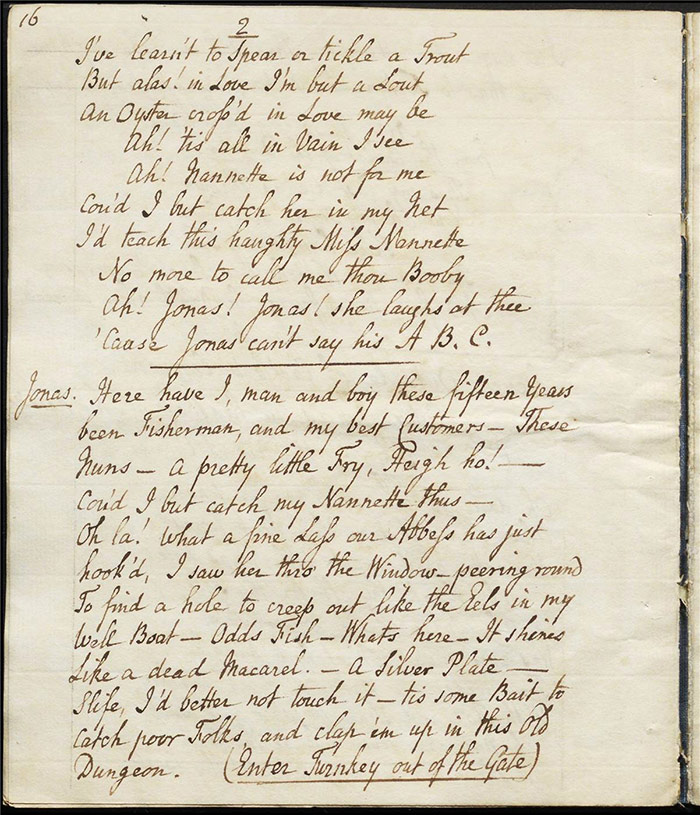

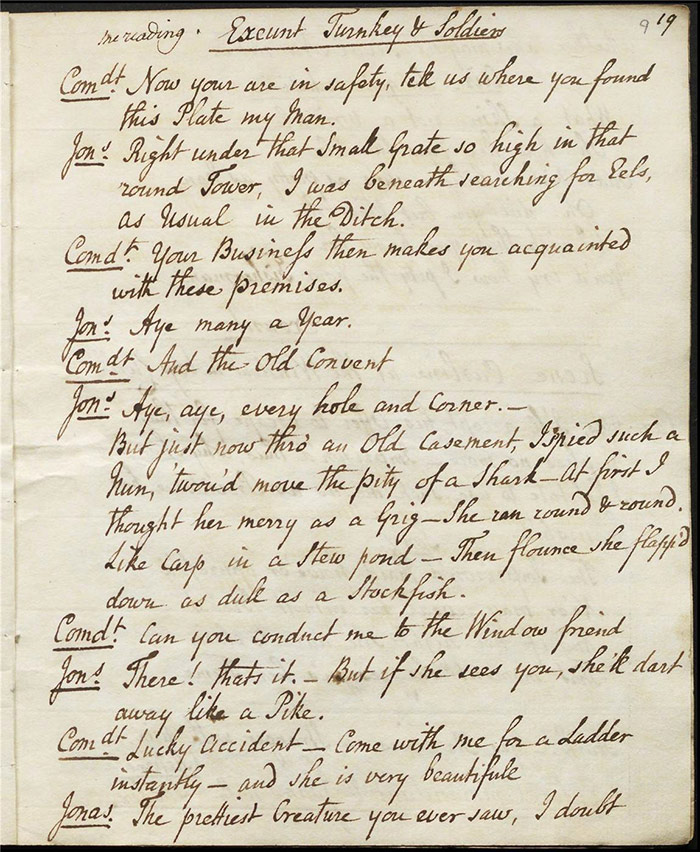

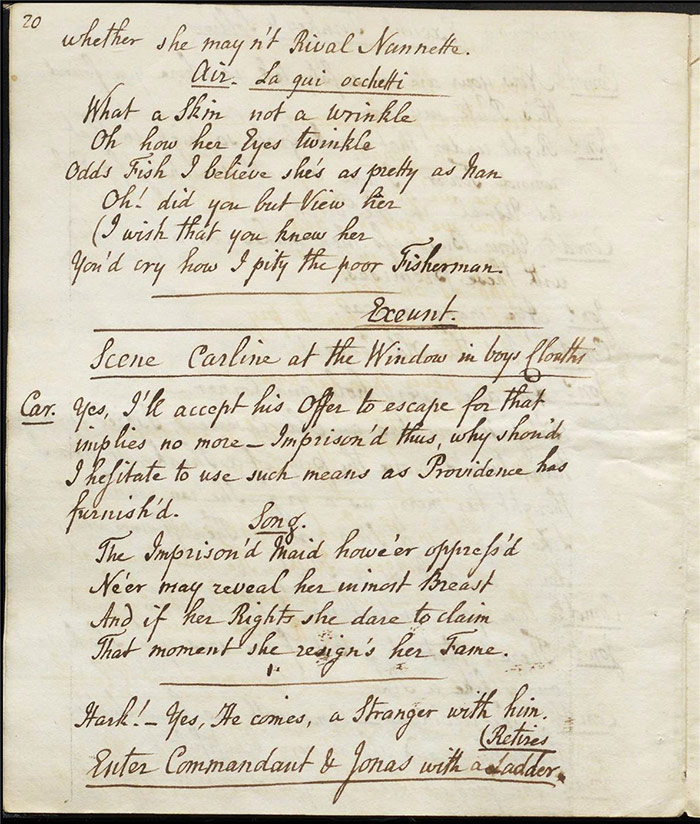

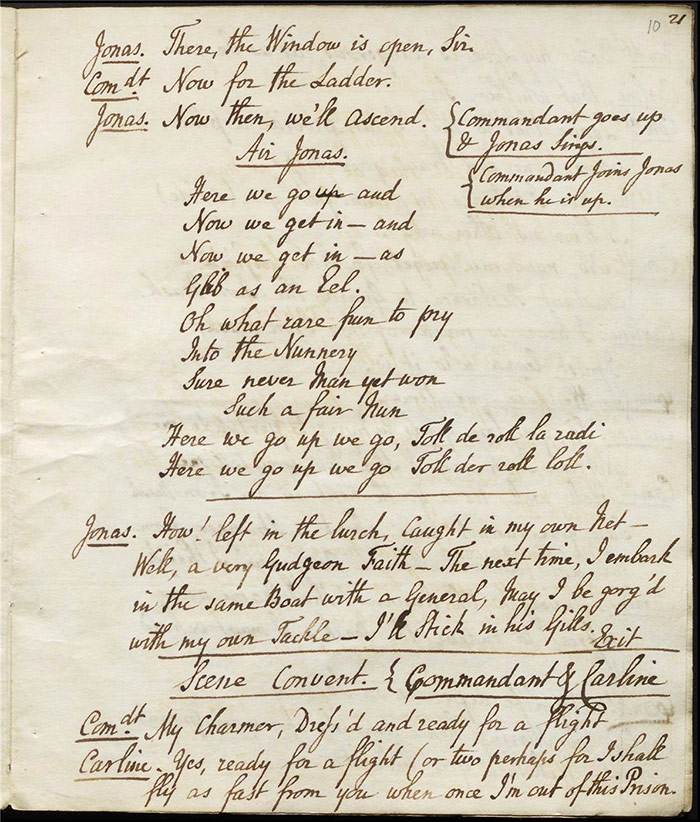

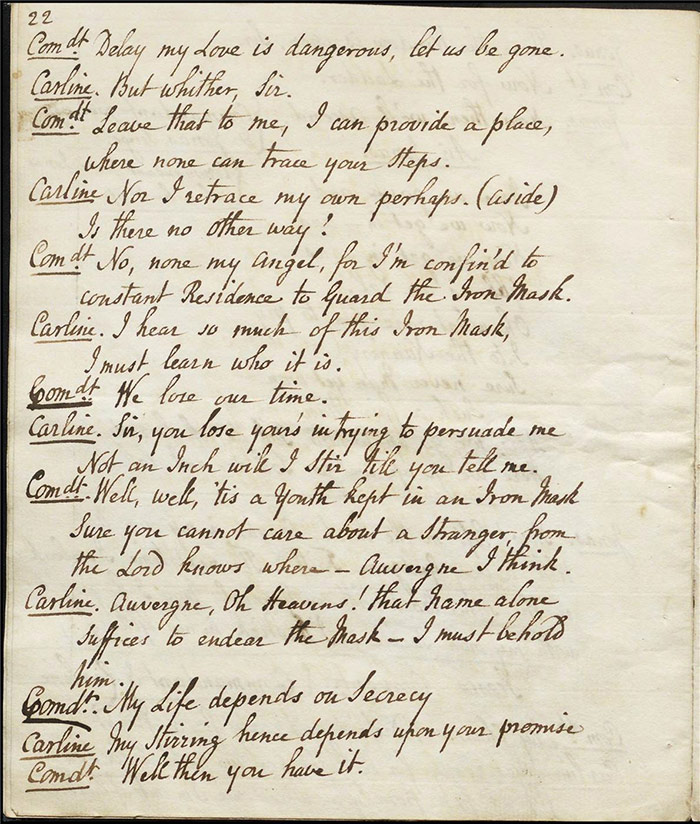

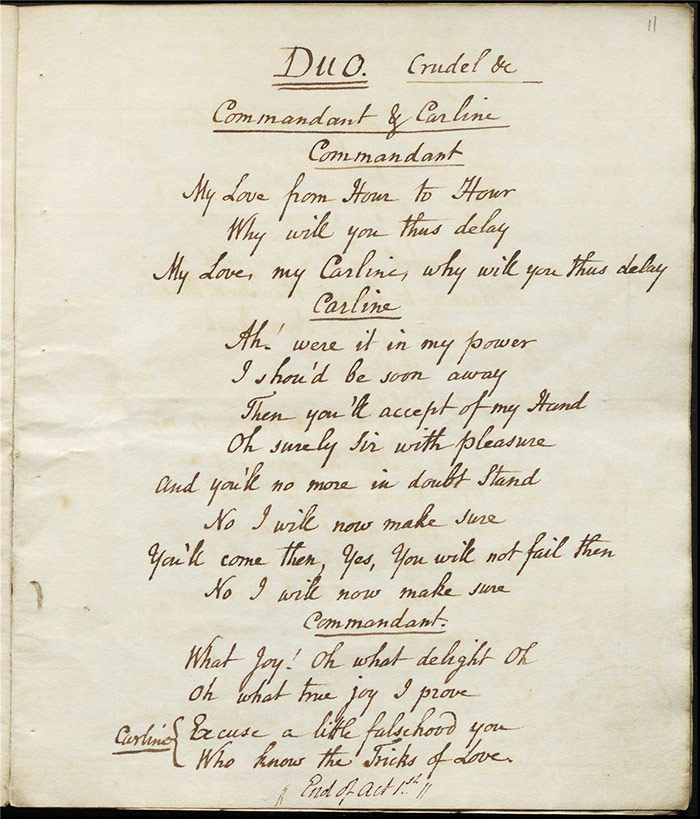

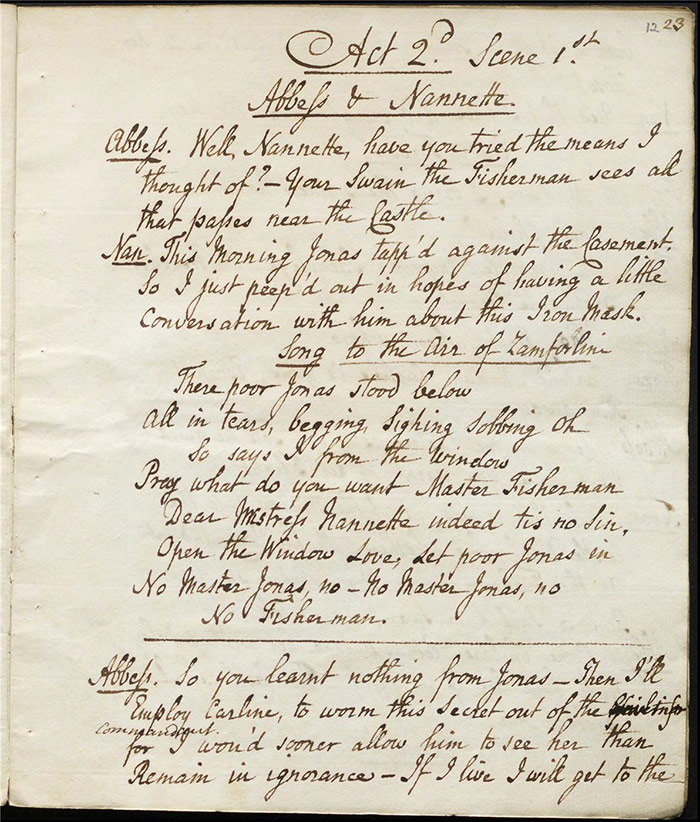

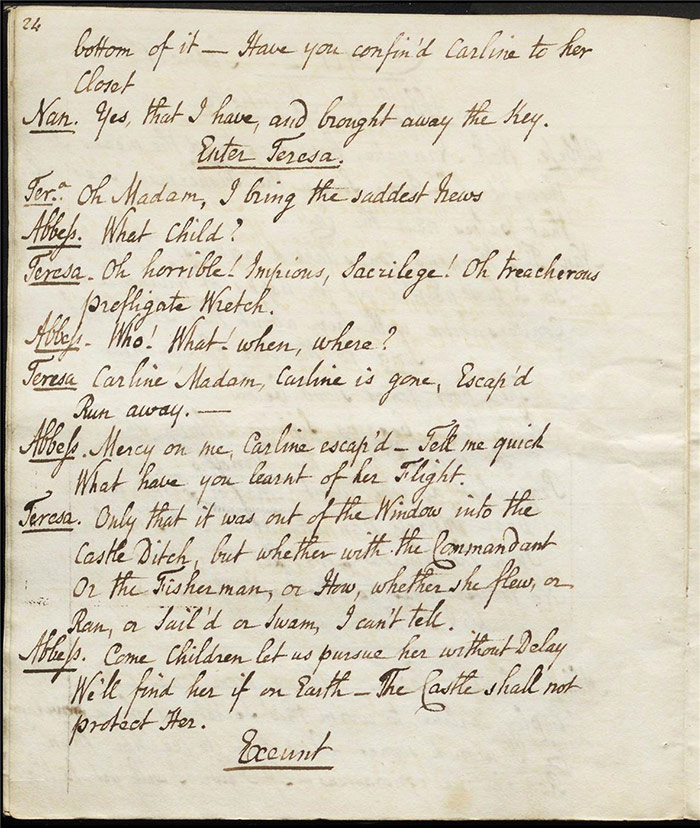

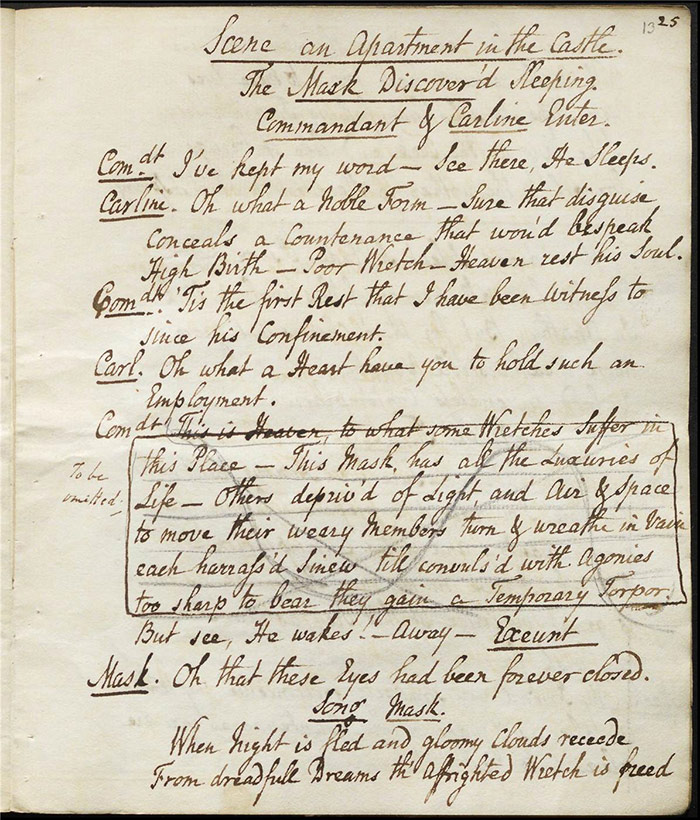

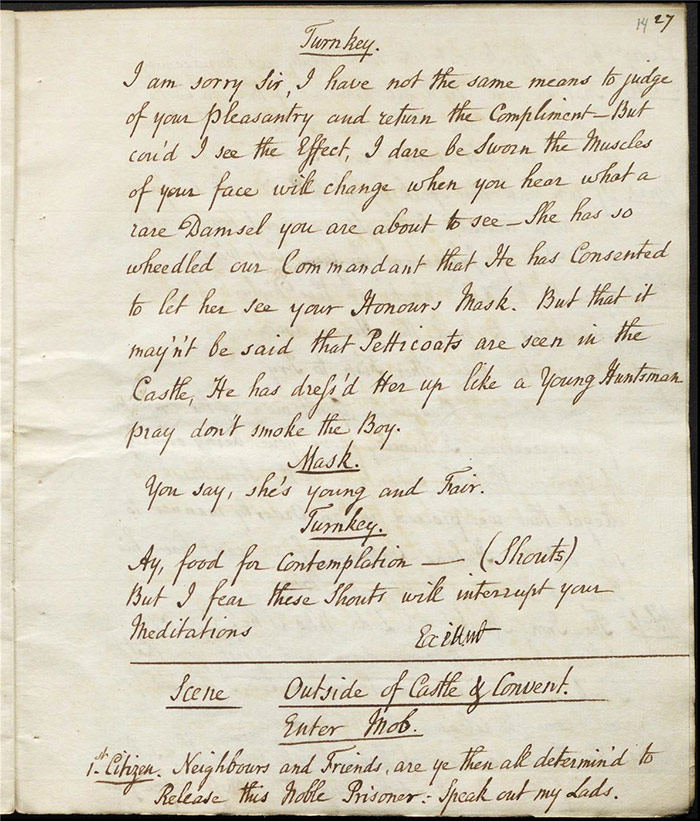

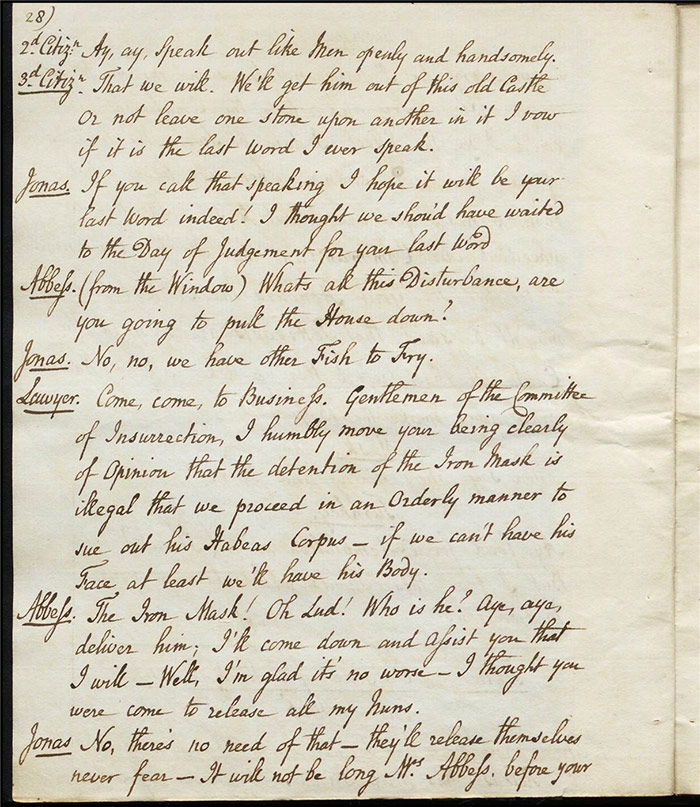

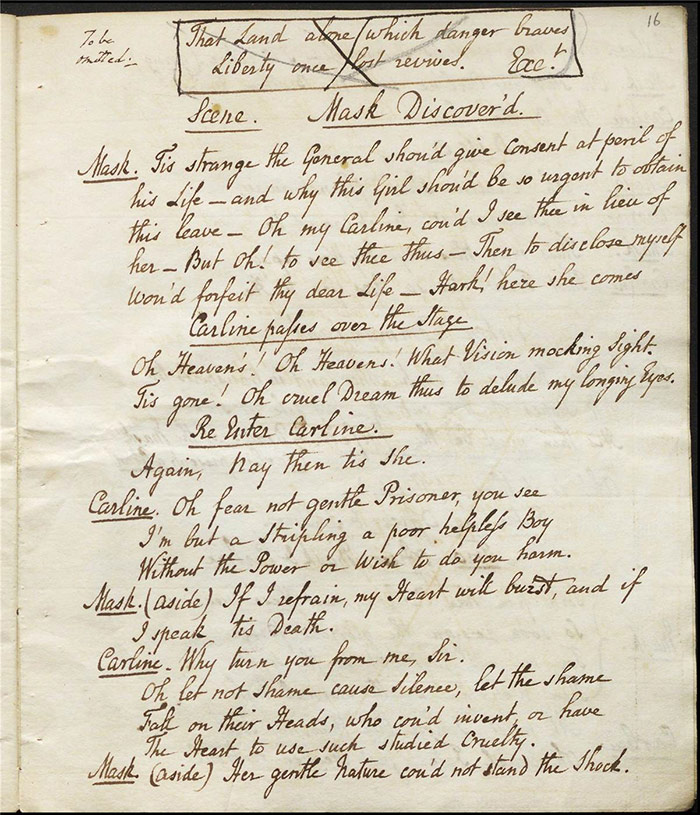

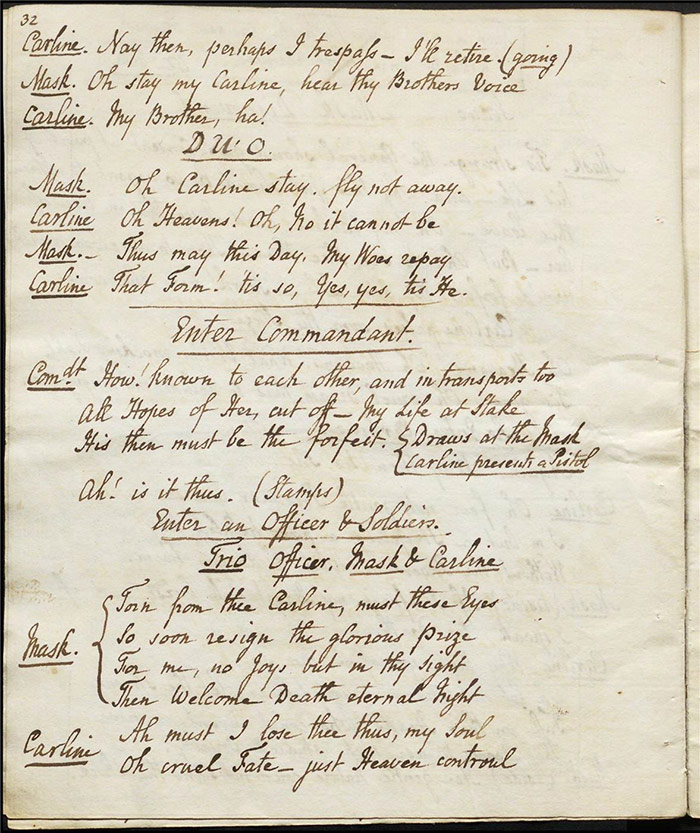

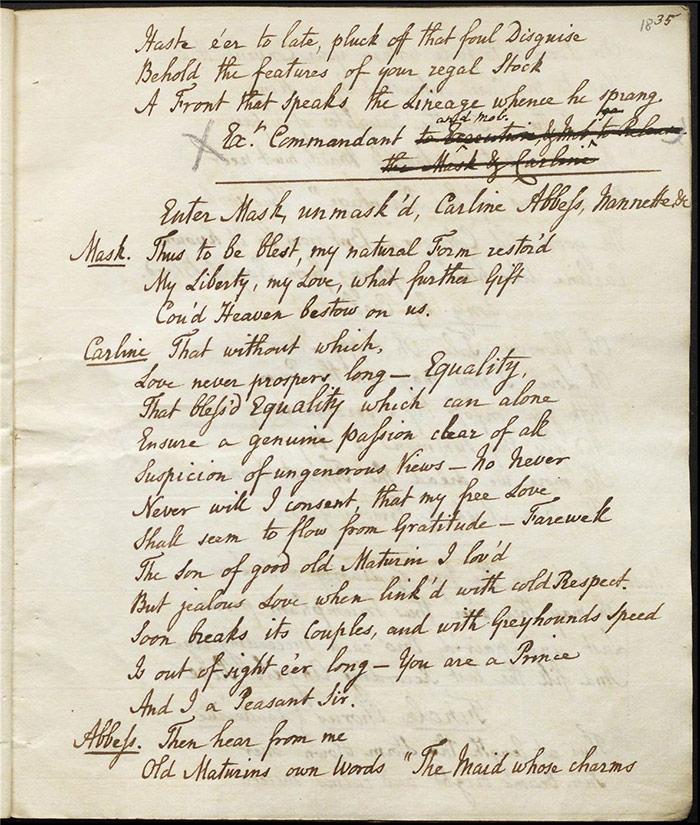

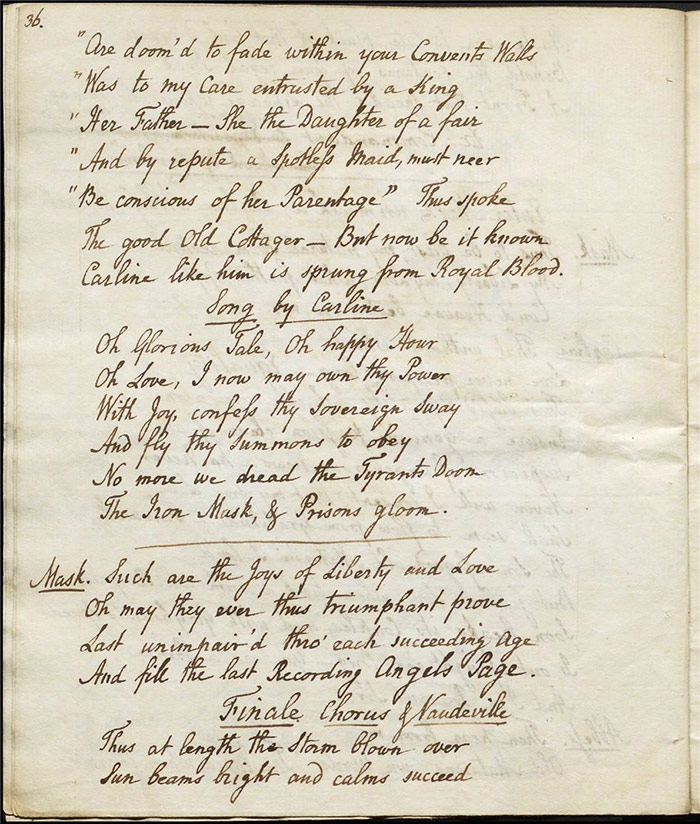

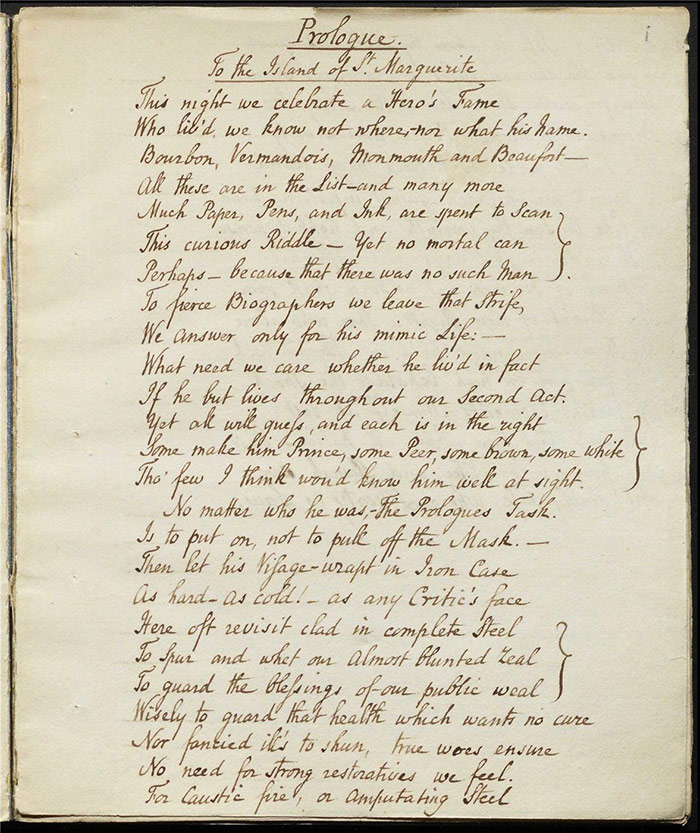

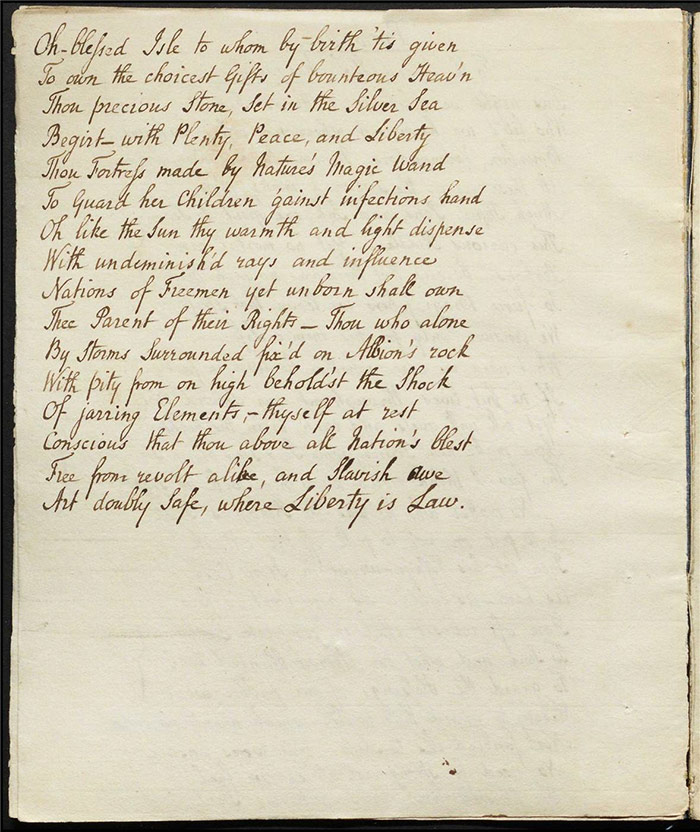

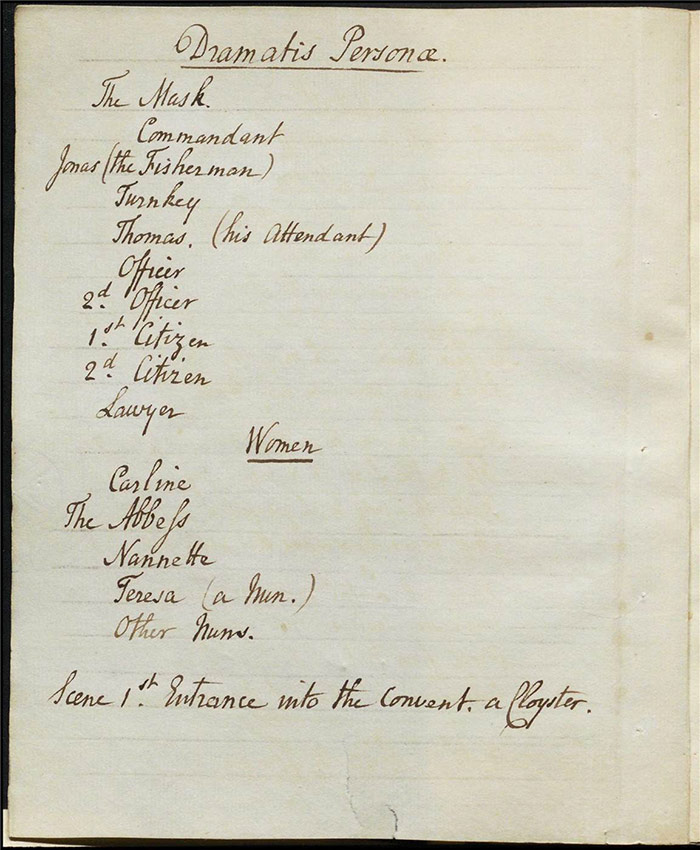

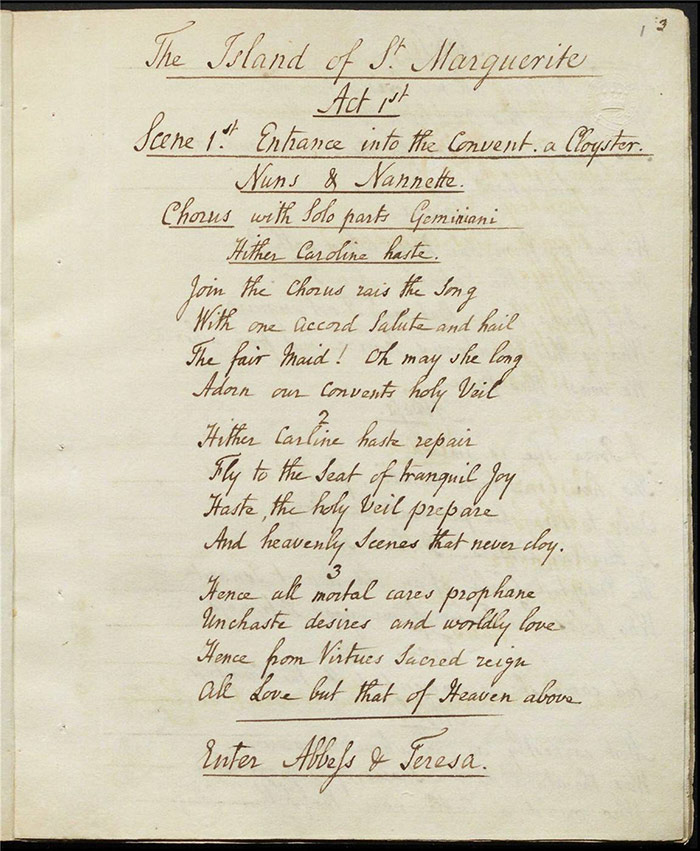

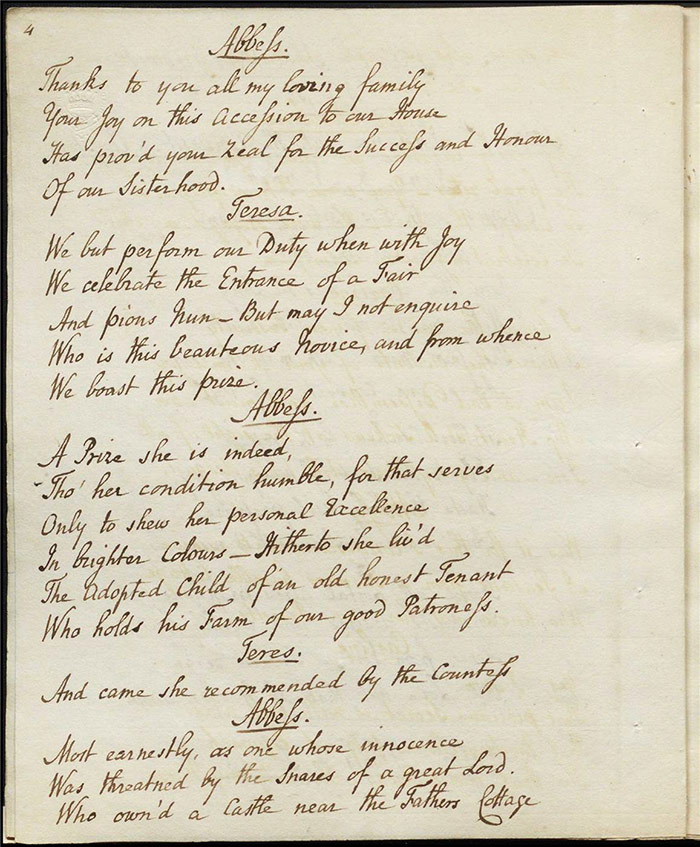

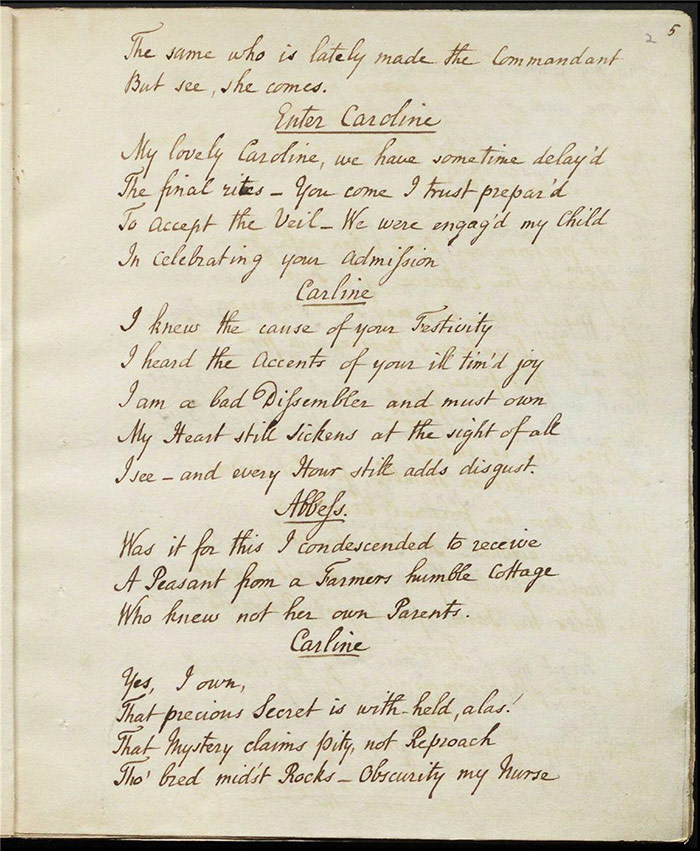

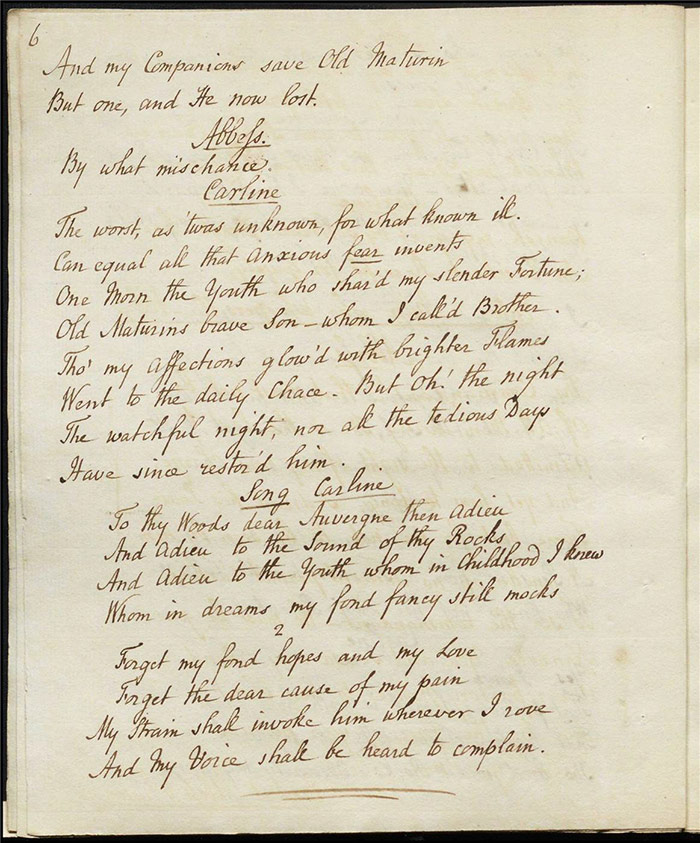

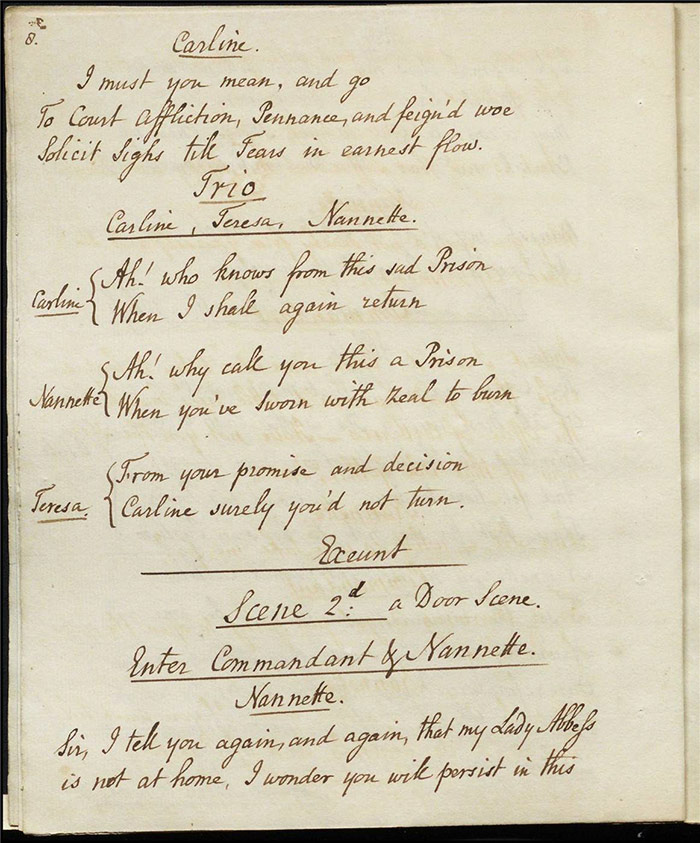

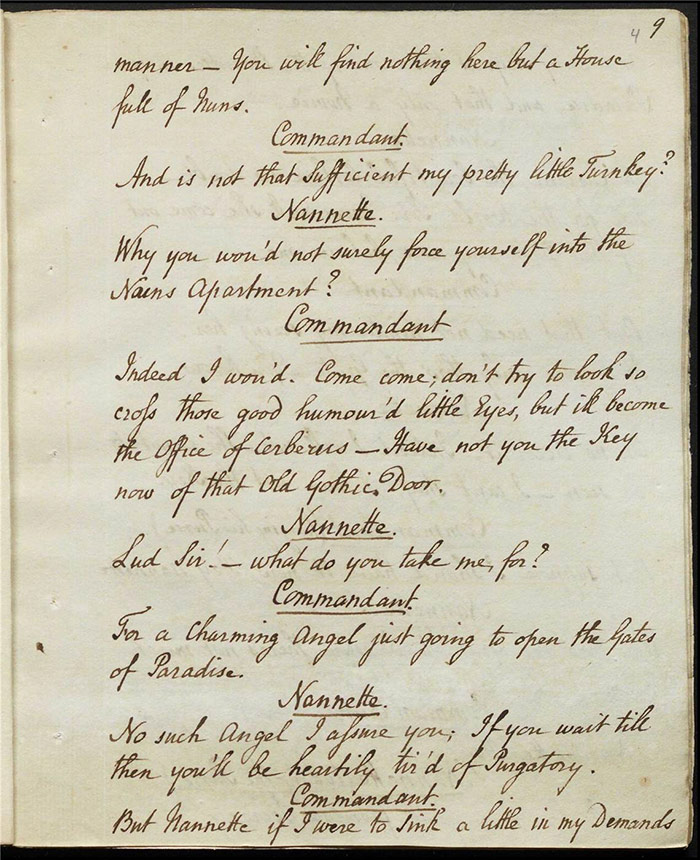

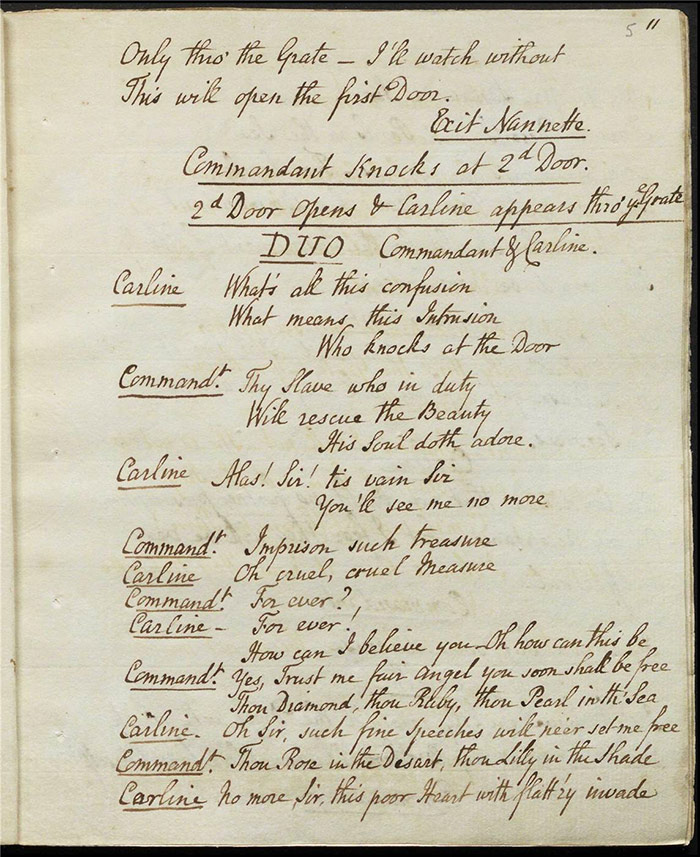

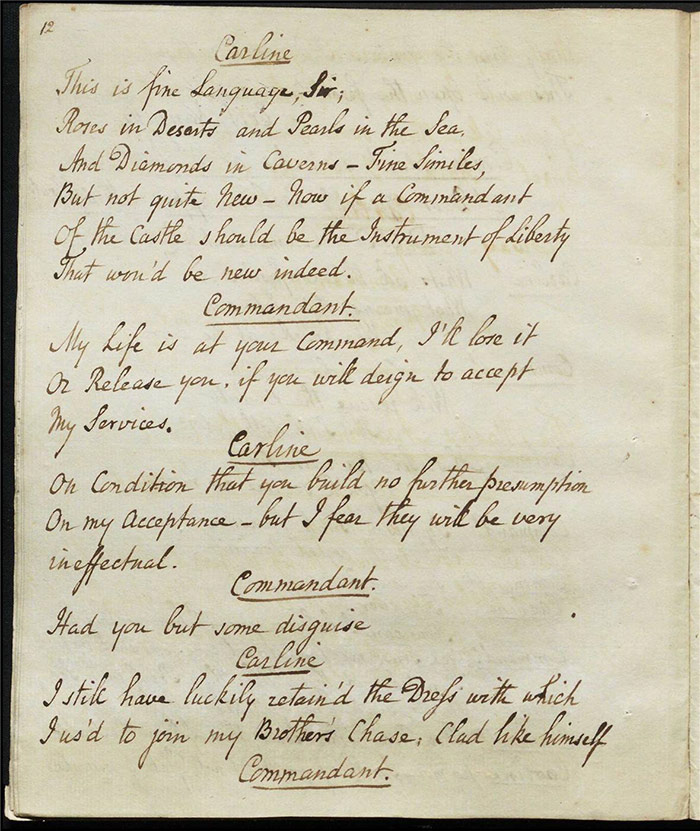

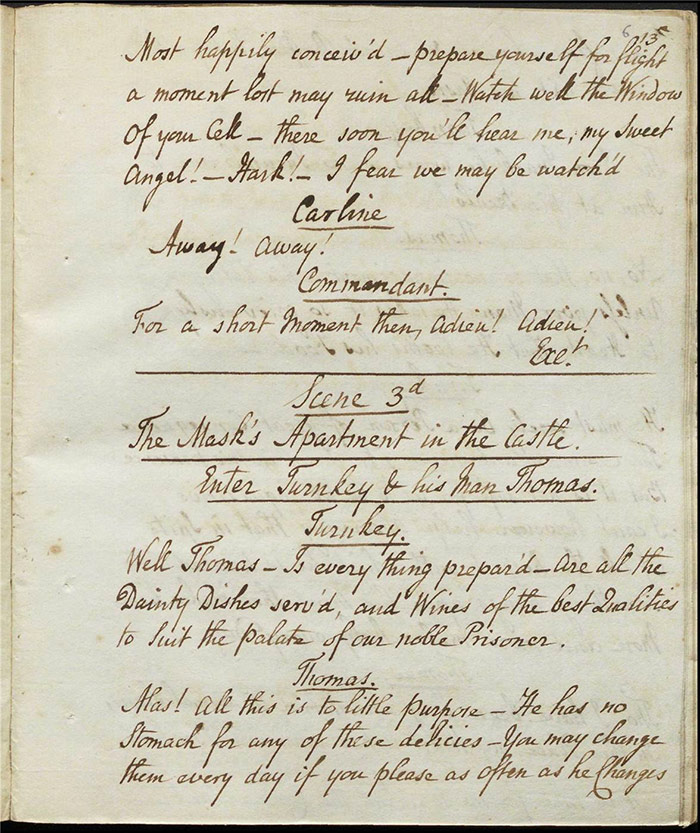

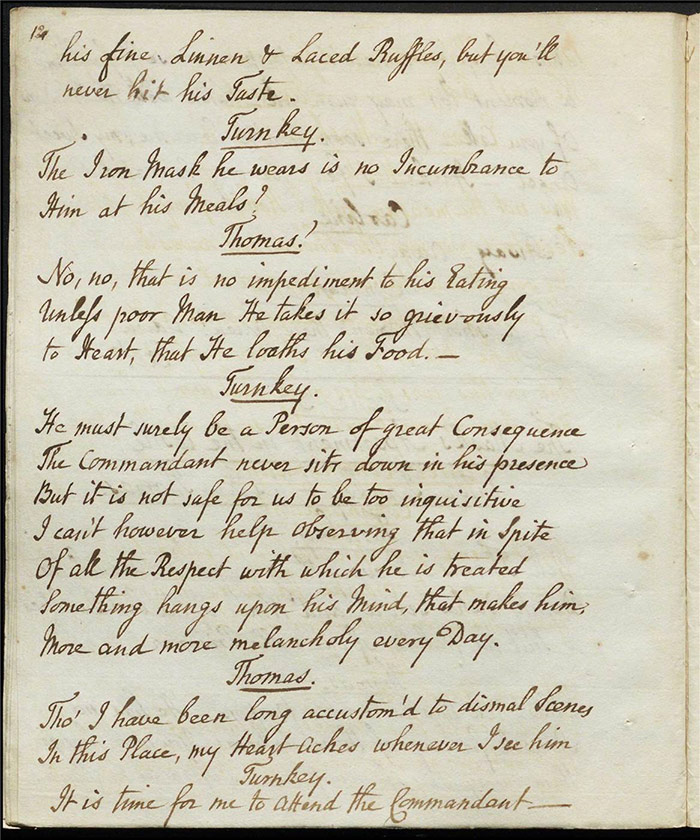

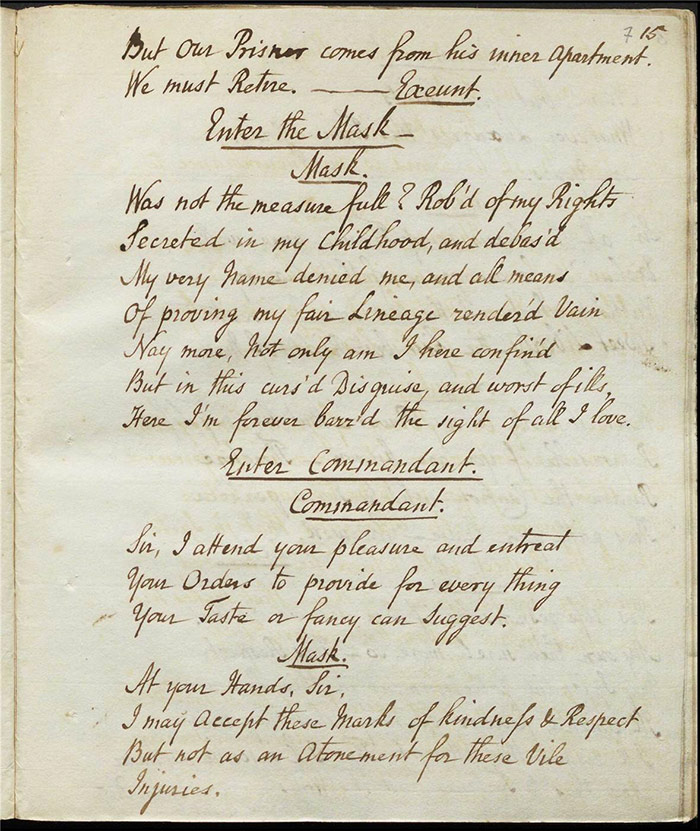

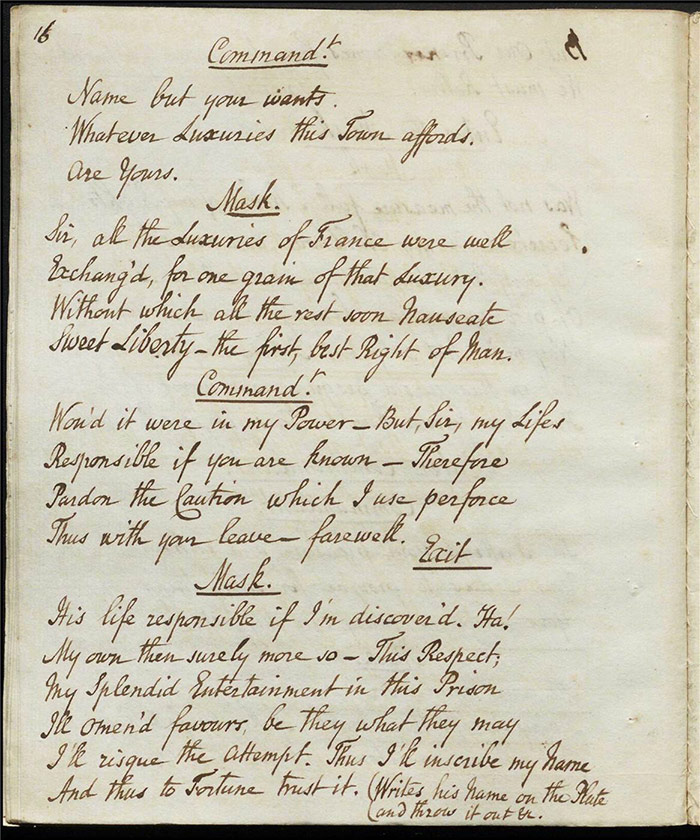

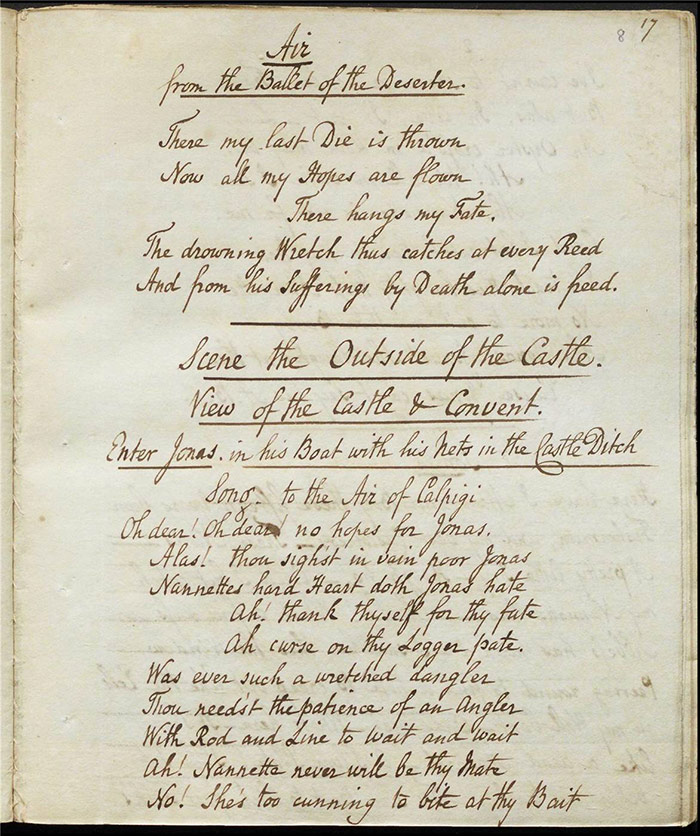

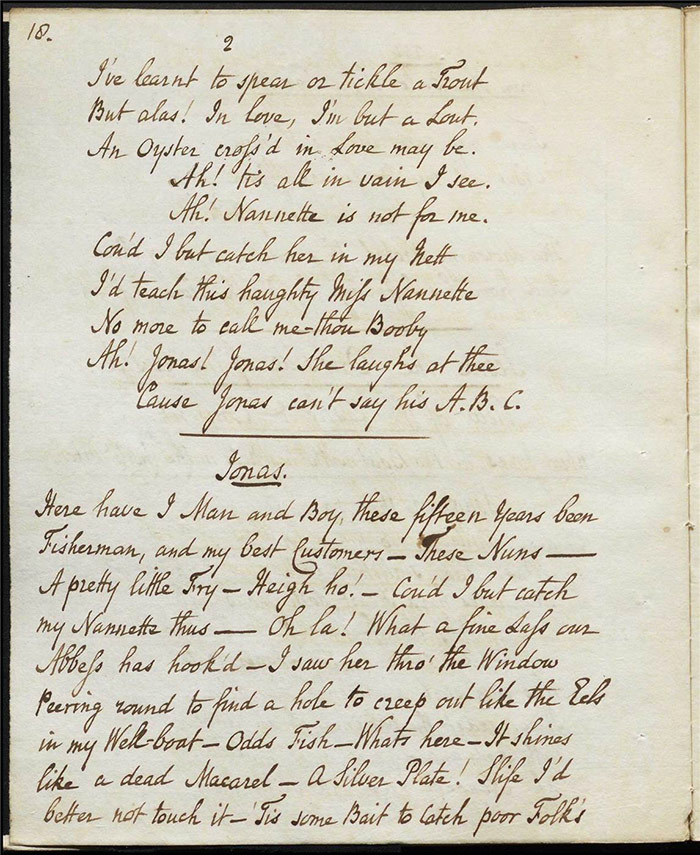

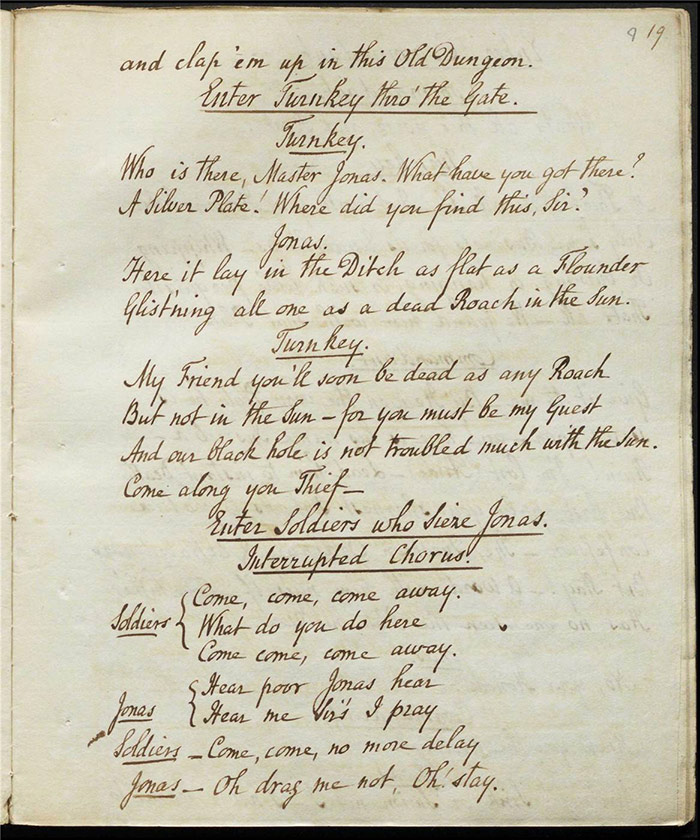

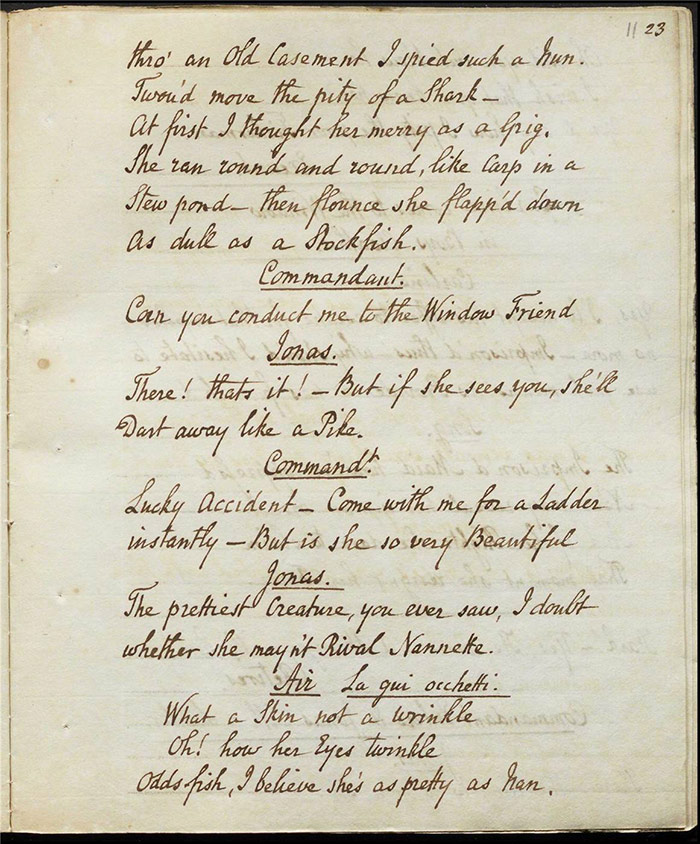

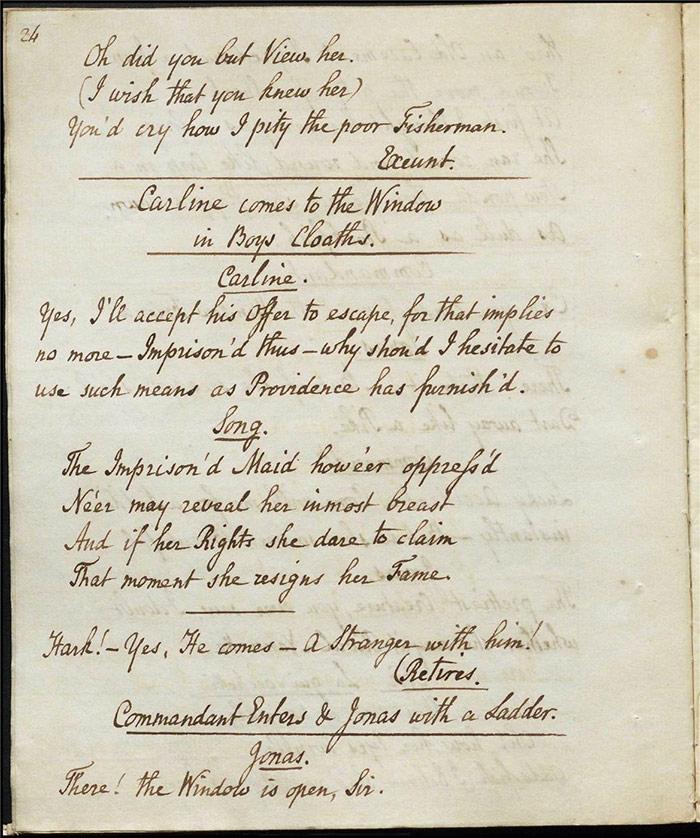

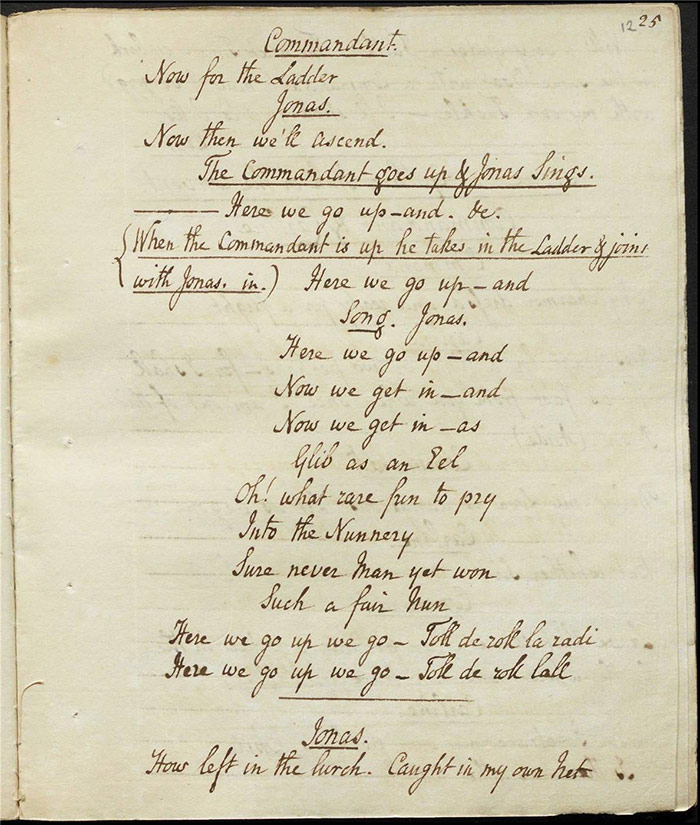

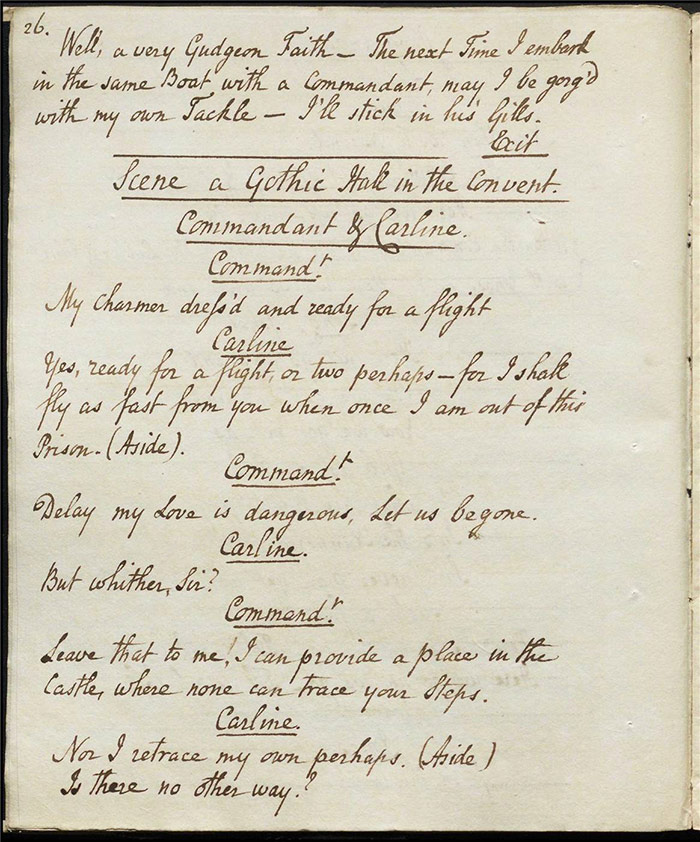

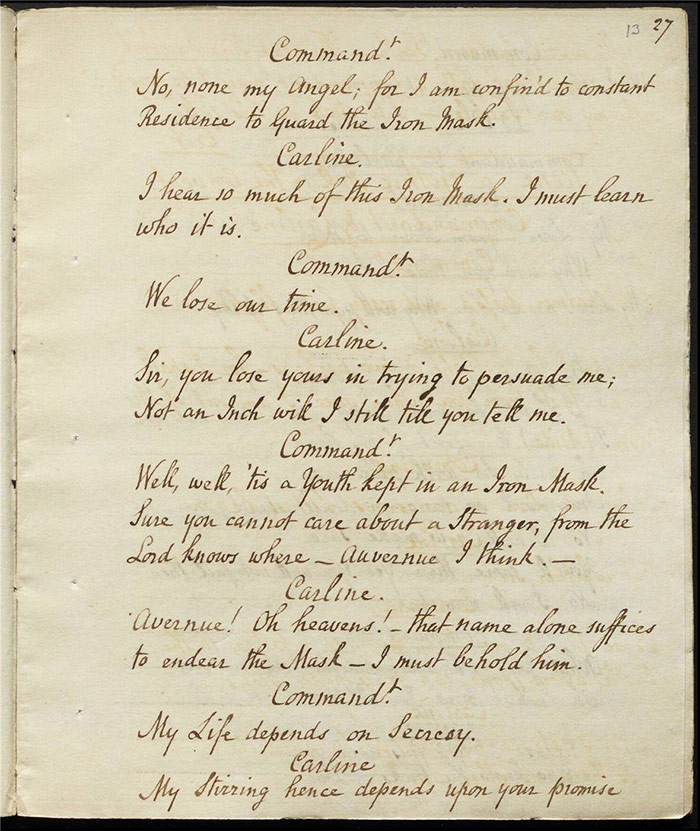

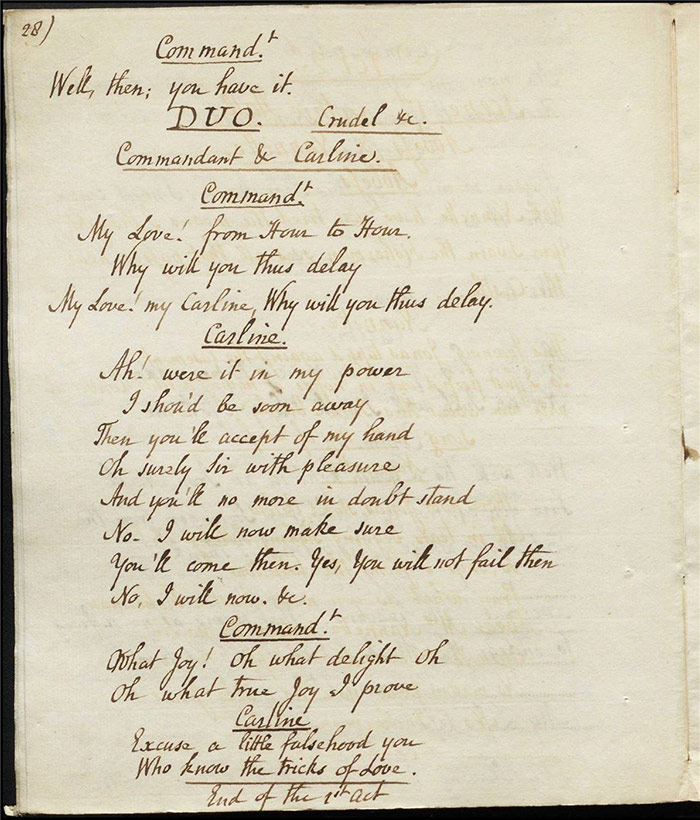

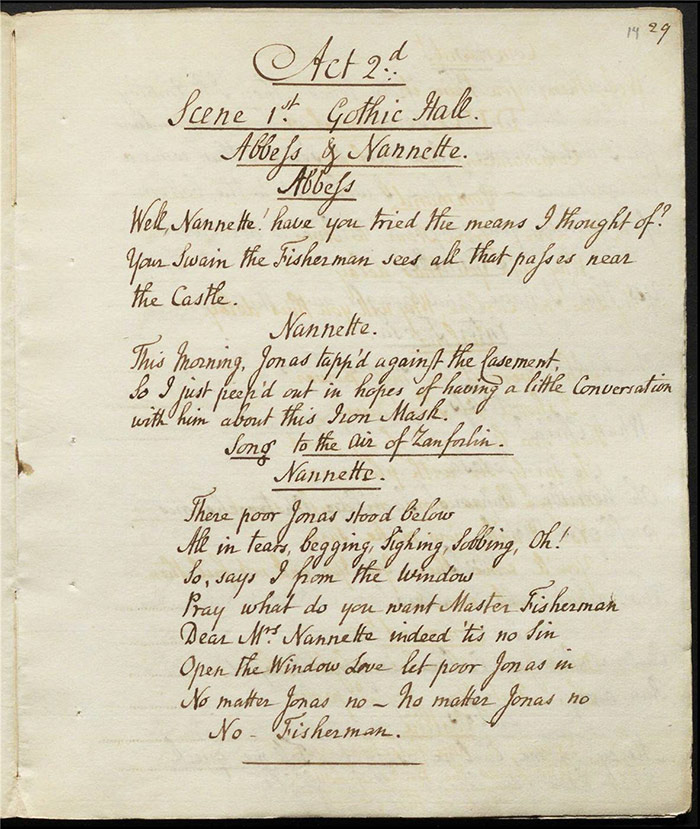

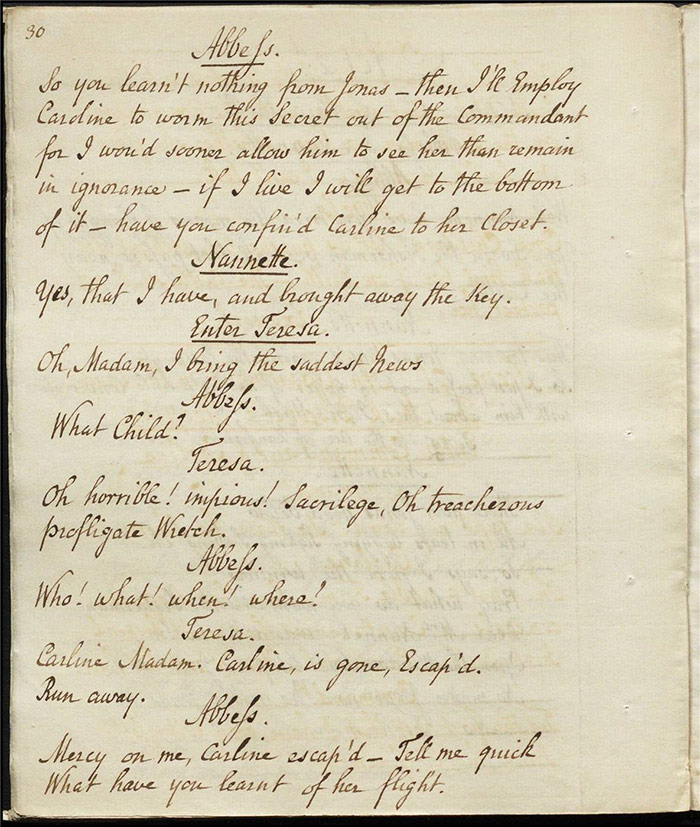

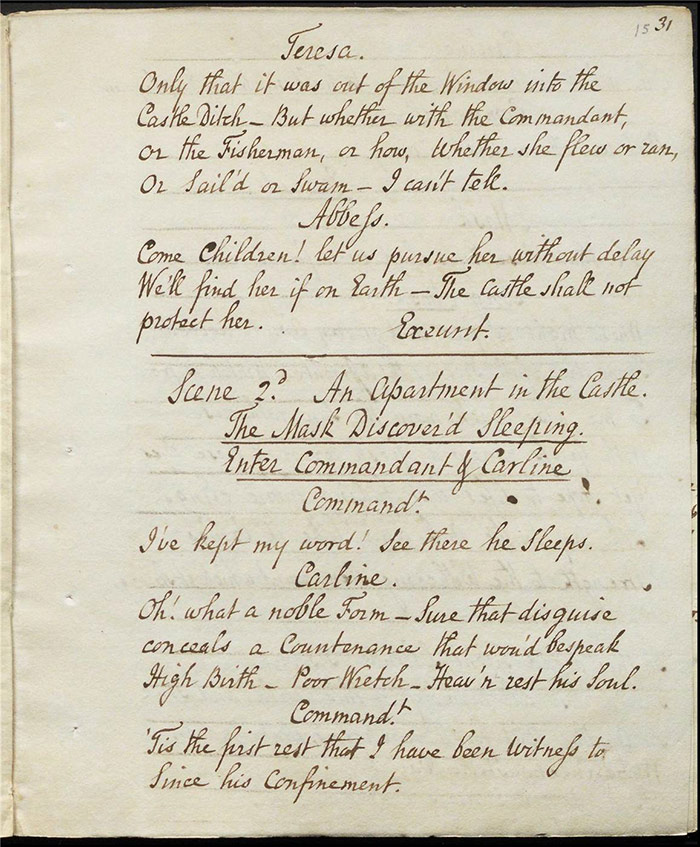

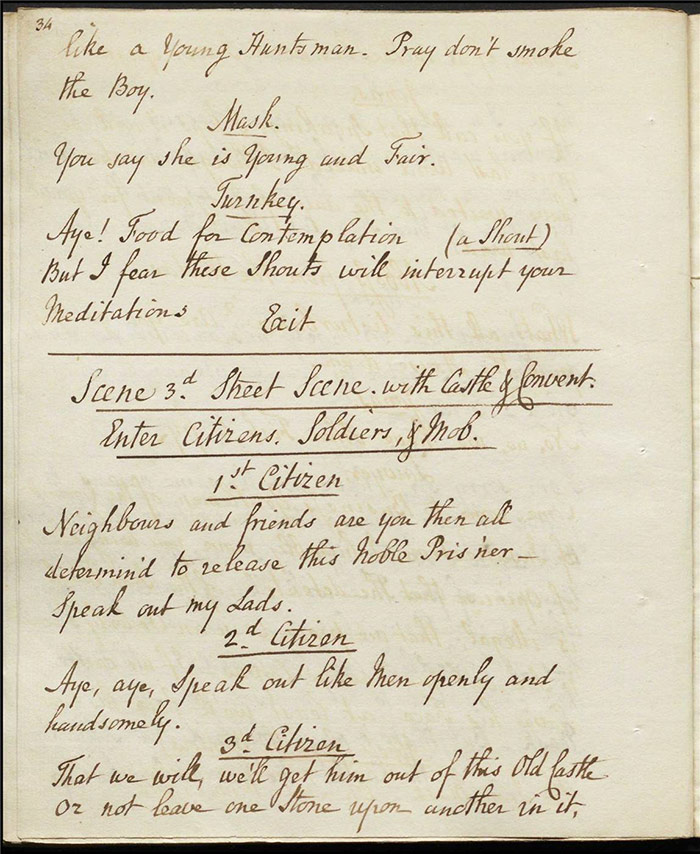

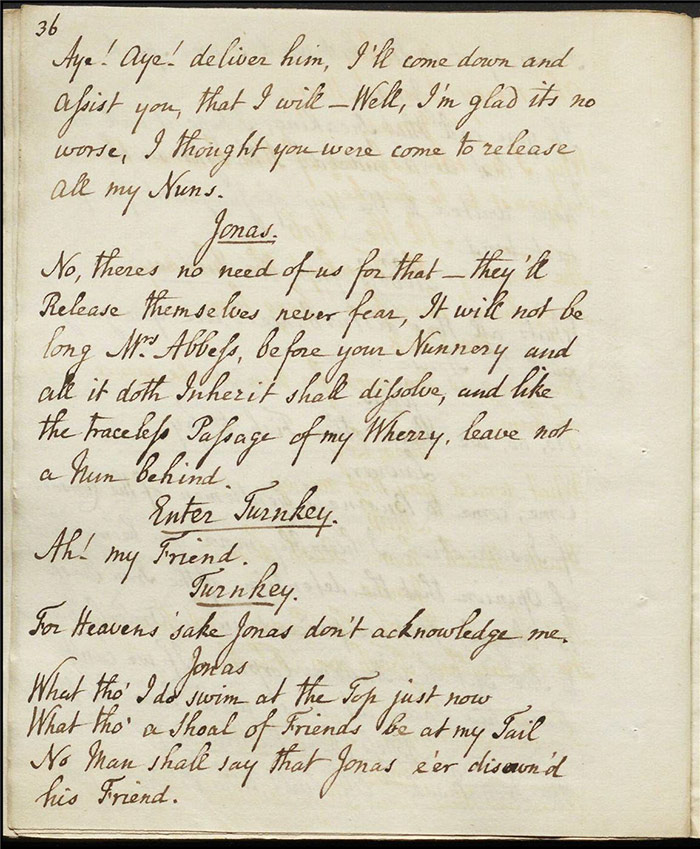

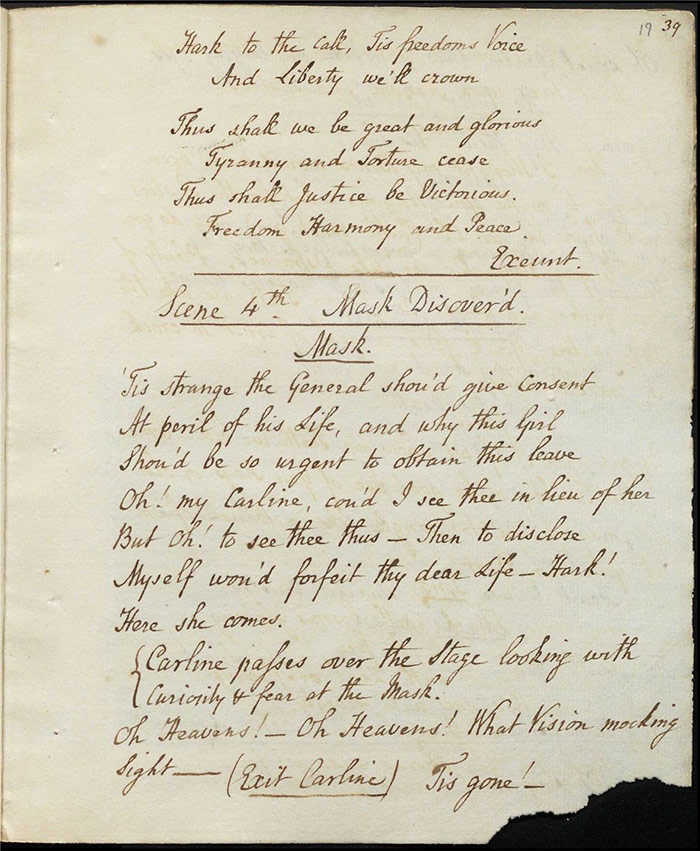

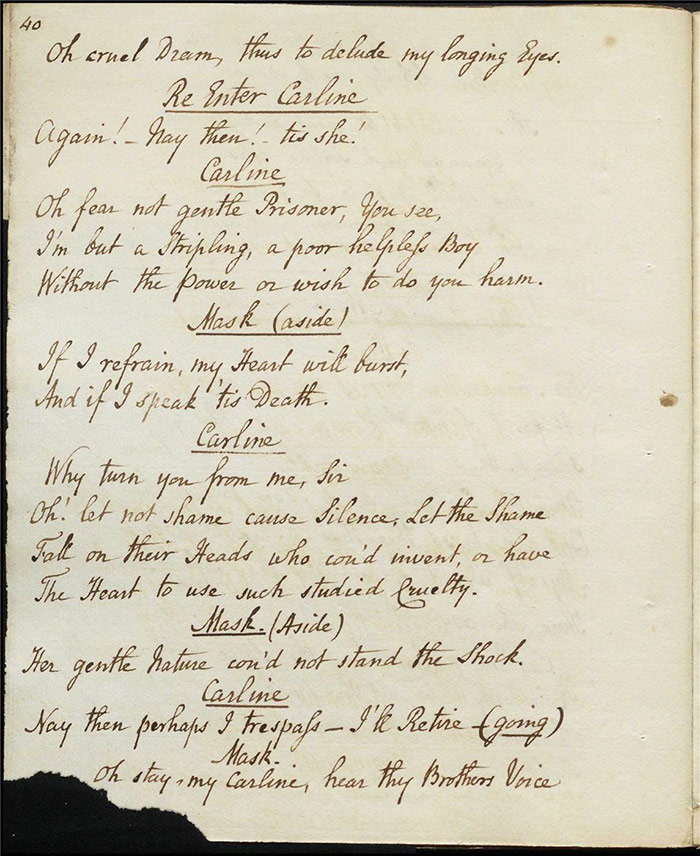

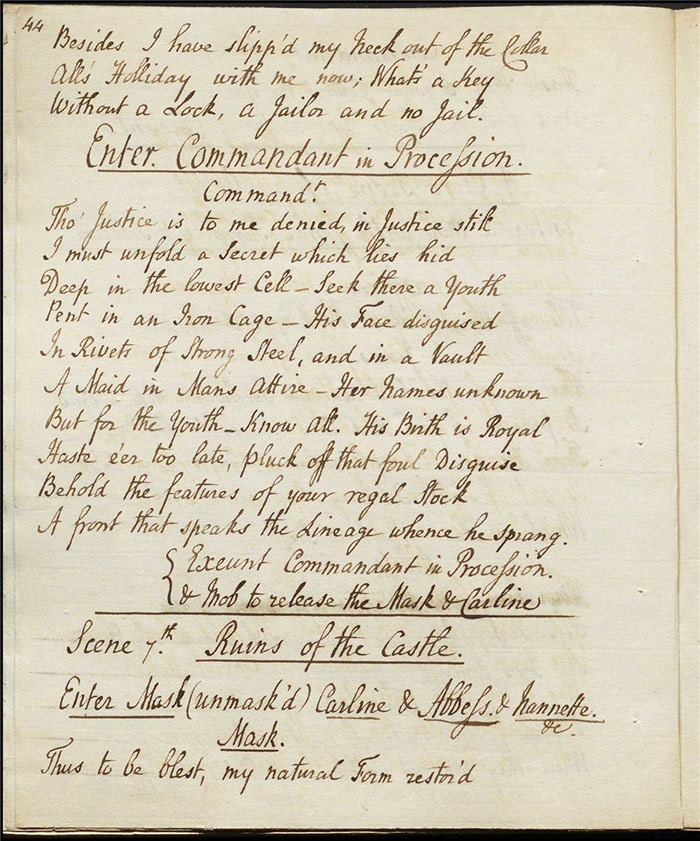

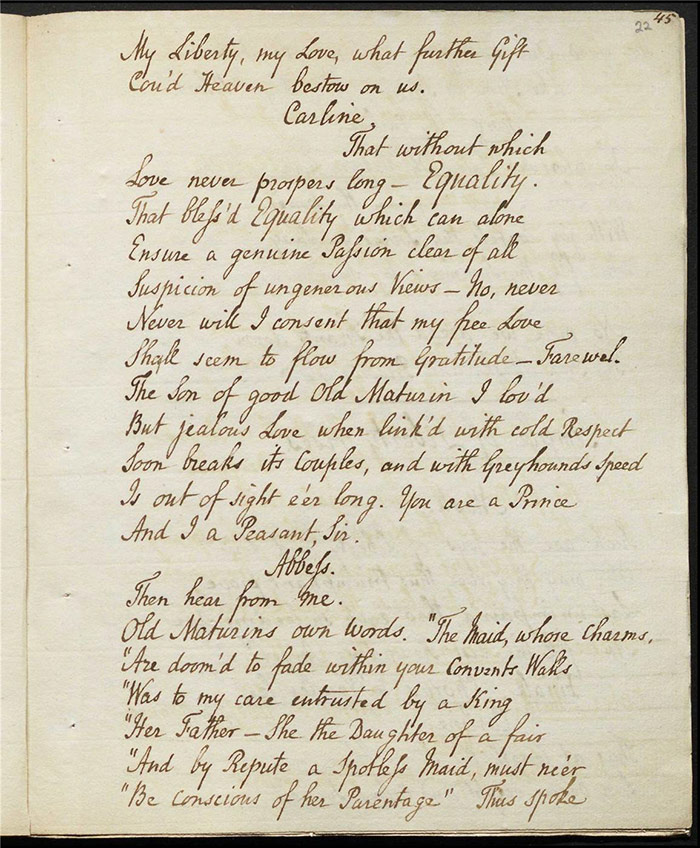

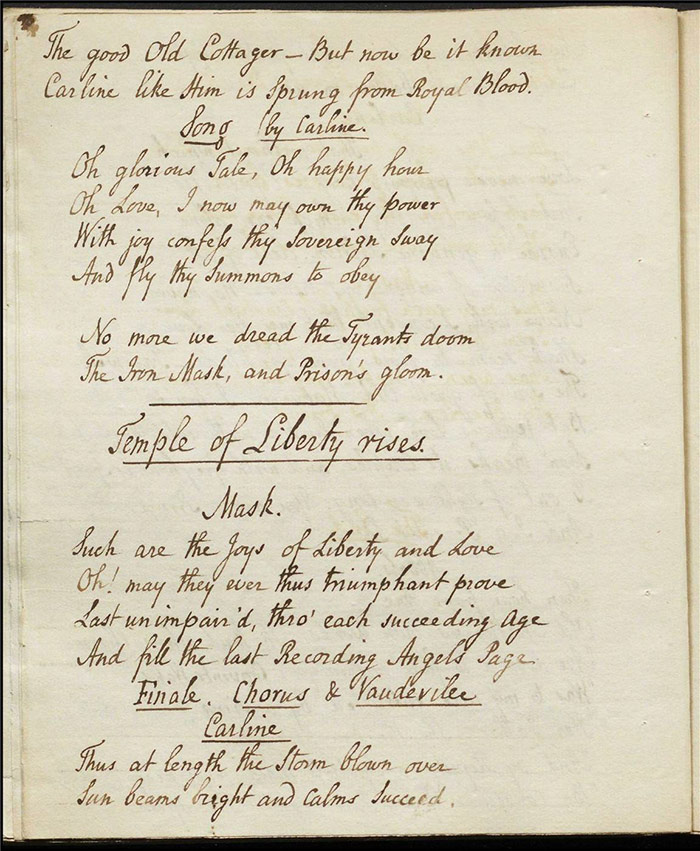

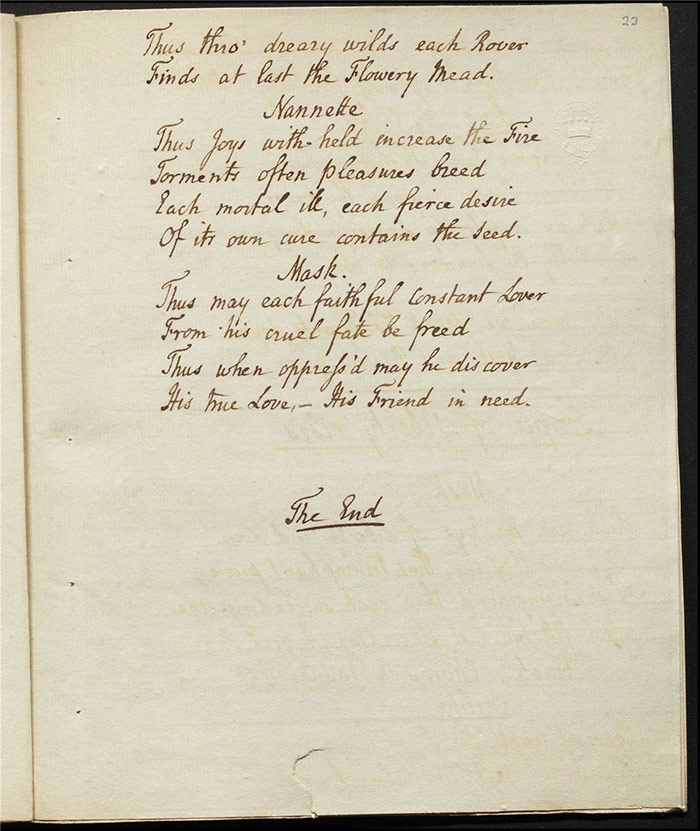

The plot of this two-act opera tells a version of the story of the seventeenth-century French prisoner known as the man in the iron mask (the piece was originally titled The Iron Mask, as the manuscript testifies). The plot here is given from LA 845; there are very minor differences in the resubmission which are noted in the commentary below. The piece begins with a convent of nuns on the titular island celebrating the arrival of a new novitiate, Carline, who has escaped the attentions of a lascivious lord living near her (although he has also become Commandant of the island). Carline is unhappy as she misses her childhood companion, the son of her guardian, Maturin. The arrival of the Commandant means she has to hide. He bribes Nanette, another nun, for a chance to view Carline through the grate. He promises to help Carline escape before he leaves. The next scene (f.5v) sees the Turnkey and his manservant Thomas bring some food and wine to the prisoner in the iron mask. The prisoner enters, bemoaning the loss of his name and inheritance. The commandant—very deferential—enters and offers him all the luxuries of the town to the contempt of the prisoner who, provoked, writes his name on a plate and hurls it out the window. The plate is picked up by Jonas, a local fisherman, who is promptly arrested for his trouble. The Commandant sentences him to death until he discovers that he cannot read. Jonas then tells him where he can find Carline’s window and they fetch a ladder. The next scene (f.9v) sees the Commandant climb into Carline’s room. She is hesitant but agrees to go if he will tell her who the man in the mask is. A duet concludes the first act. The second act (f.12r) opens with the Abbess telling Nanette she is determined to find out the identity of the man in the mask. They are disturbed when another nun tells them Carline has escaped. They all leave in pursuit. The following scene (f.13r) finds the Commandant showing Carline the man in the mask; he is asleep in his cell. They leave when he wakes up. Meanwhile, a mob has approached, led by Jonas, determined to free the prisoner. Carline and the man in the mask meet and discover each other’s identity to their great joy–he is Maturin–but the Commandant, enraged, commits them both to different cells. The mob capture the Commandant and he confesses the location and royal identity of the prisoner to them. In the denouement, Carline, like the prisoner, is also revealed to have royal blood and the path to their marriage is secured.

Performance, publication, and reception

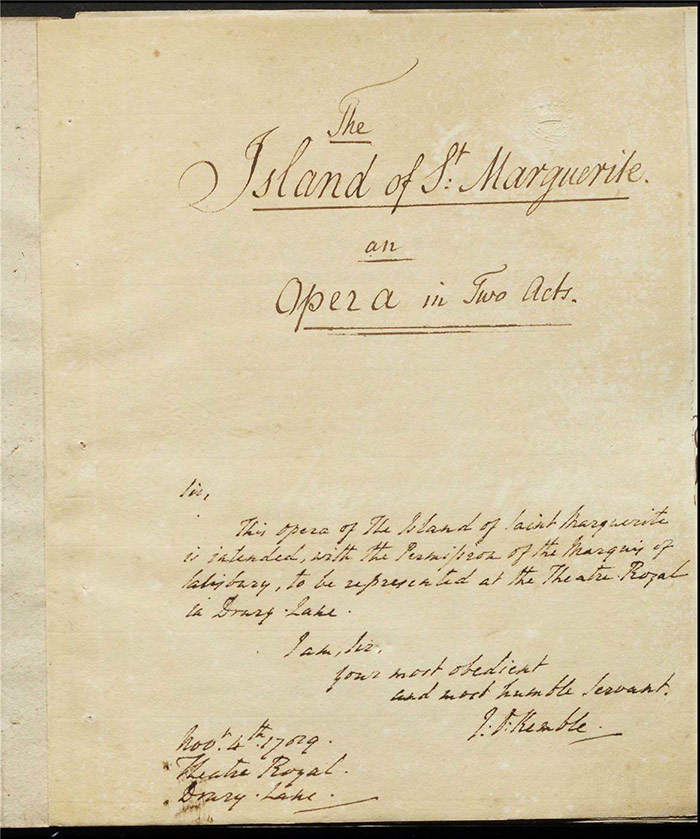

The original manuscript was submitted probably sometime in October 1789. It was resubmitted again on 21 October by John Kemble, who had taken over as acting manager of Drury Lane only a year earlier. A final, clean copy of the manuscript was submitted on 4 November. The piece was staged for the first time on 13 November and was extremely popular with 28 performances in its first season and 8 in the following season.

The Diary or Woodfall’s Register (15 November 1789)is full of praise for the songs, scenery, and performance of the actors. The review is a little more hesitant about the plot, pointing out some breaches in the ‘licentia theatrica’. However, the writer is aware of Larpent’s intervention and gives the author the benefit of the doubt;

It would be altogether unfair and invidious to enter into any elaborate criticism on an Opera, thus circumstanced; we know not what has been cut out by the Licenser, but Mr. St. John has a right to take credit for having had his piece so injured by its having been officially annalysed [sic], that it remained a caput mortuum, when it came out of the Licenser’s Crucible, the blame ought not to rest at his door.

The Morning Herald (14 November 1789) prefers to cite the Lord Chamberlain himself (to whom the Examiner reported) as the main obstacle and does so rather sceptically, even mockingly:

Objections of state ought only to be directed against the stage, where the grounds are consistent, and the necessity evident: – But where the interference is dictated by folly, and unmeaning consequence, a resistance ought to be made.

The World (14 November 1789) rather daringly explicitly links the play to the events of the French Revolution, opening its review by immediately pointing out that the island was where members of the French Parliament were sent in 1788. Nonetheless, the writer is rather underwhelmed by the opera as his pithy summary indicates:

As for the Story, it is impossible to blame it, for there is not any. — The Man in the IRON MASK is there imprisoned—there writes his name on a PLATE—there the Plate is found.—The MOB talk of rising—the GAOLER is seized—the Man in the Iron Mask is DELIVERED—and this is sung or said “Let Freedom’s bounded rage, / Fill the recording Angels lasting page.”

Despite this somewhat caustic take, there is praise for the music and the latter part of the prologue also gets a nod of approval for it ‘apostrophised Great Britain and Liberty’. With a touch of incredulity, the reviewer writes a couple of days later

FORTUNE and fashion are doing for this splendid PANTOMIME, what regard to good and gentleman-like manners would wish to do towards the quarter from which it came. — Neither the house, nor the applause in that house, could be fuller on Saturday; and this is the house that JACK built.

One imagines that it is surely John Kemble being referred to here, rather than St. John, but there is surely a touch of a sneer in any case by calling it a pantomime. Nonethless the writer has to admit that the music and the scenery ‘are a triumph of Management’. The review concludes by lauding the prologue which seems to have been widely successful.

Commentary

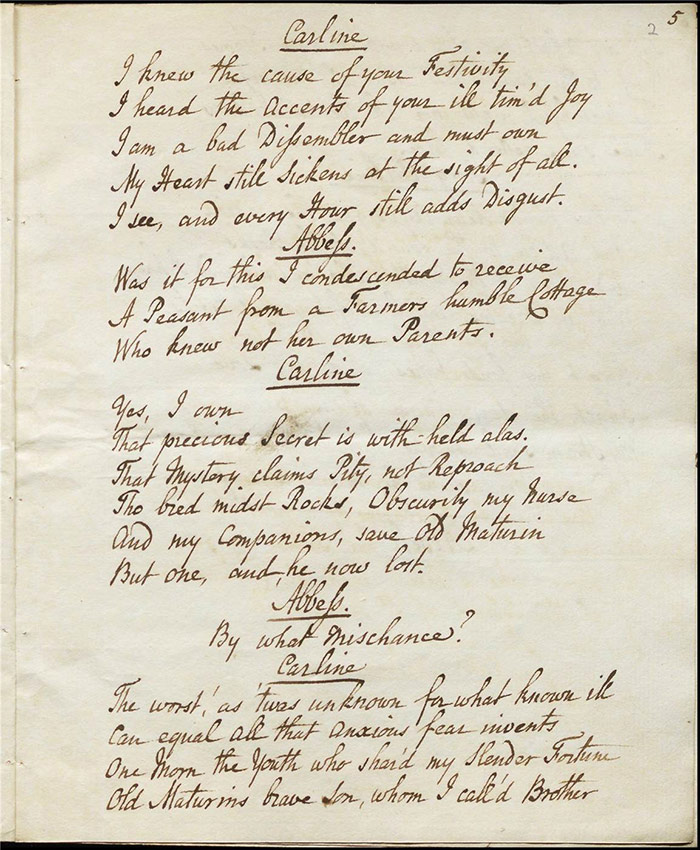

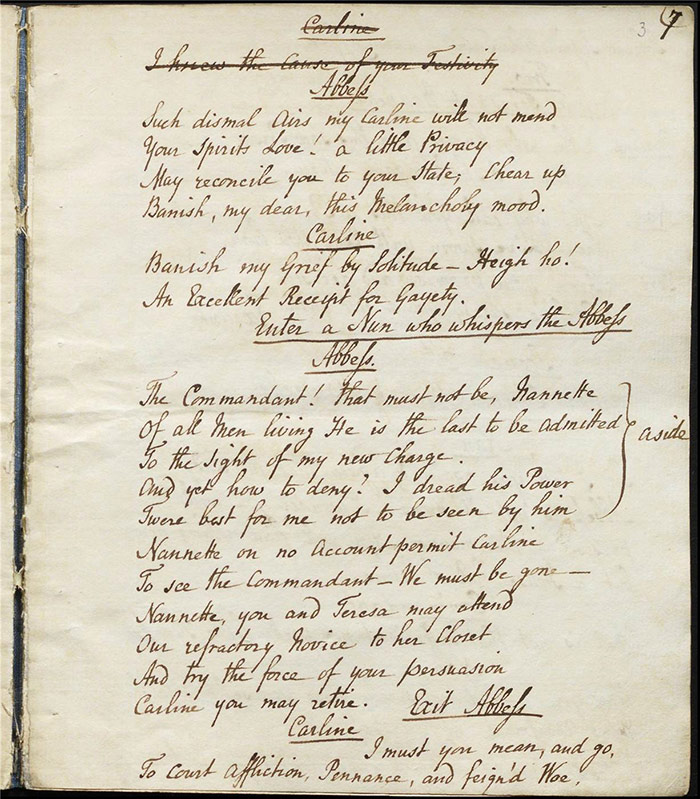

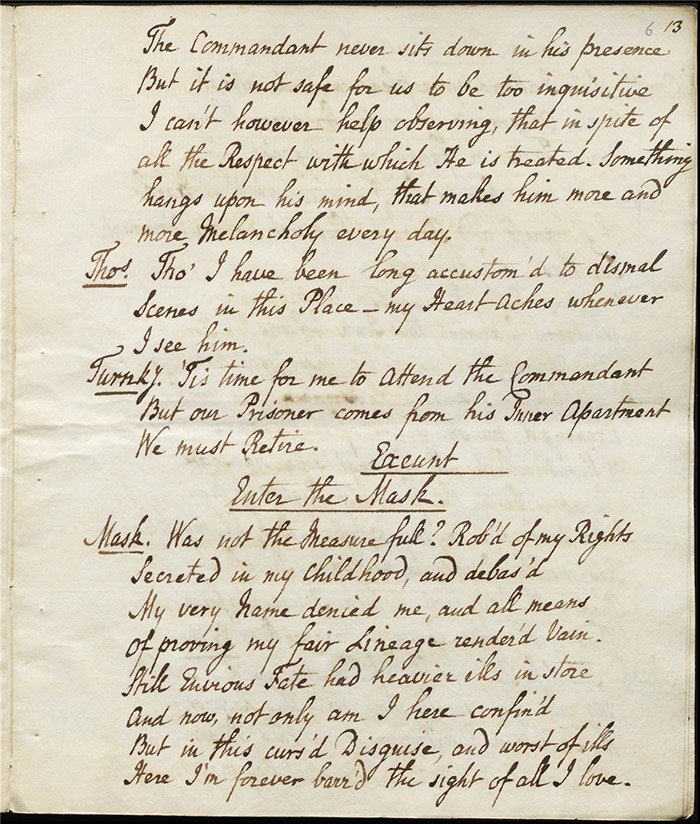

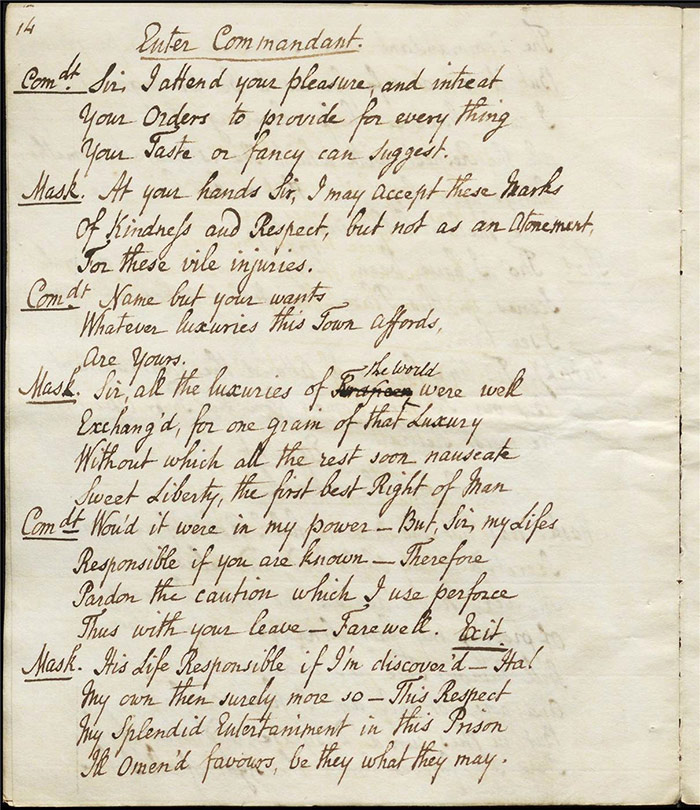

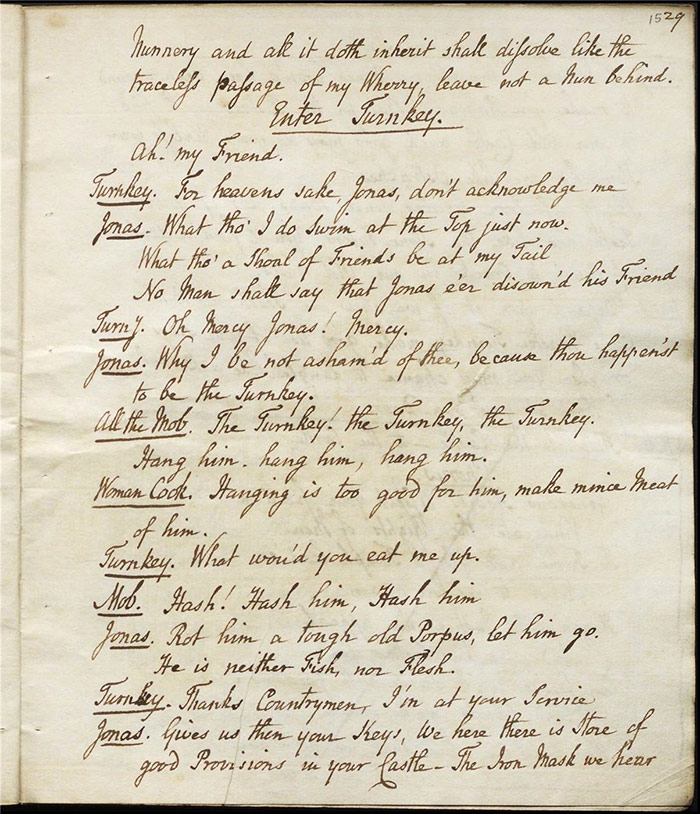

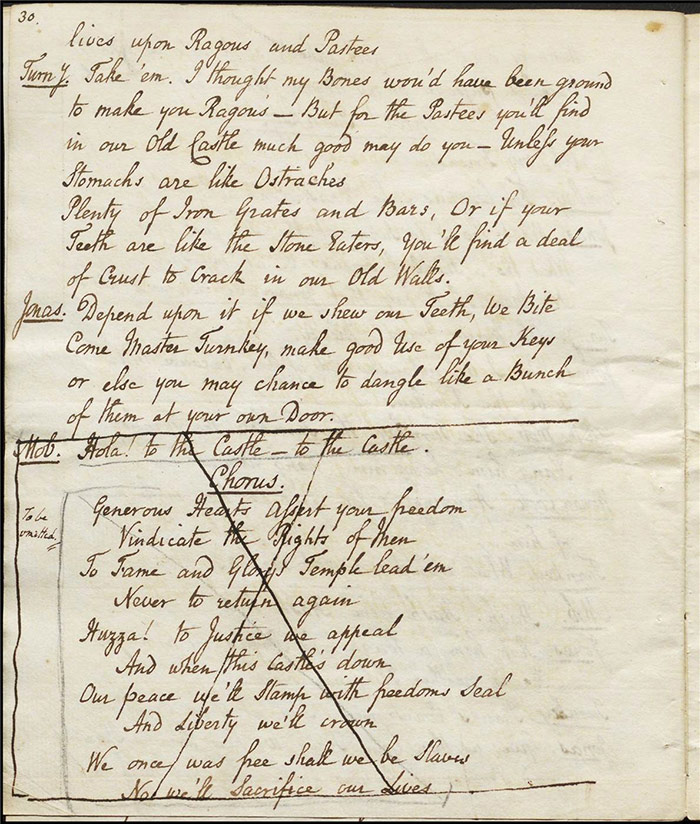

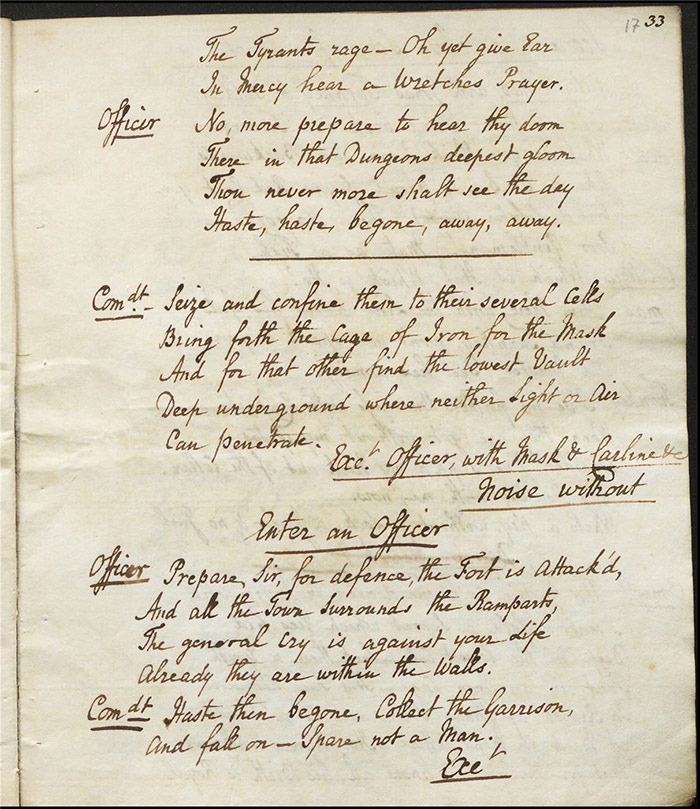

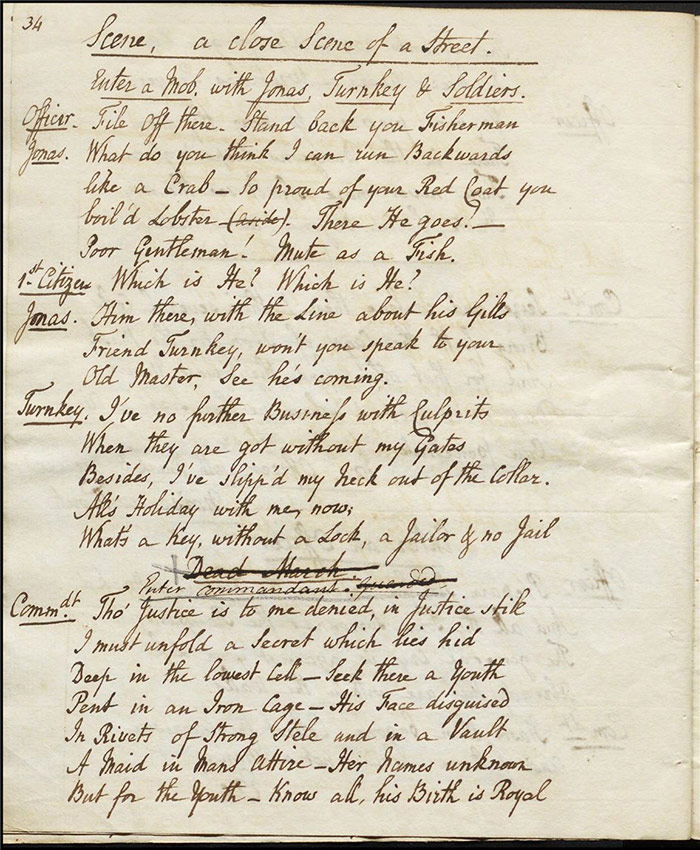

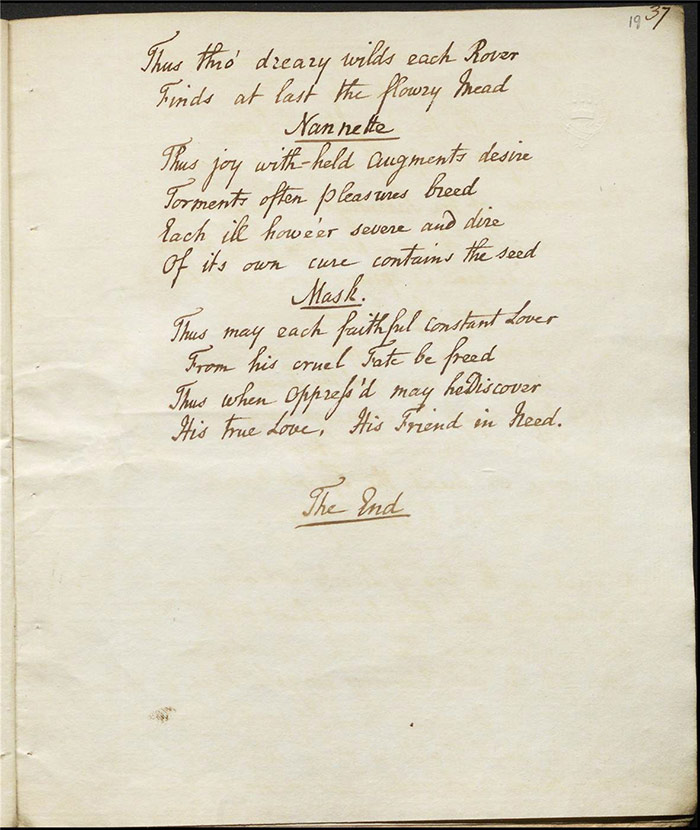

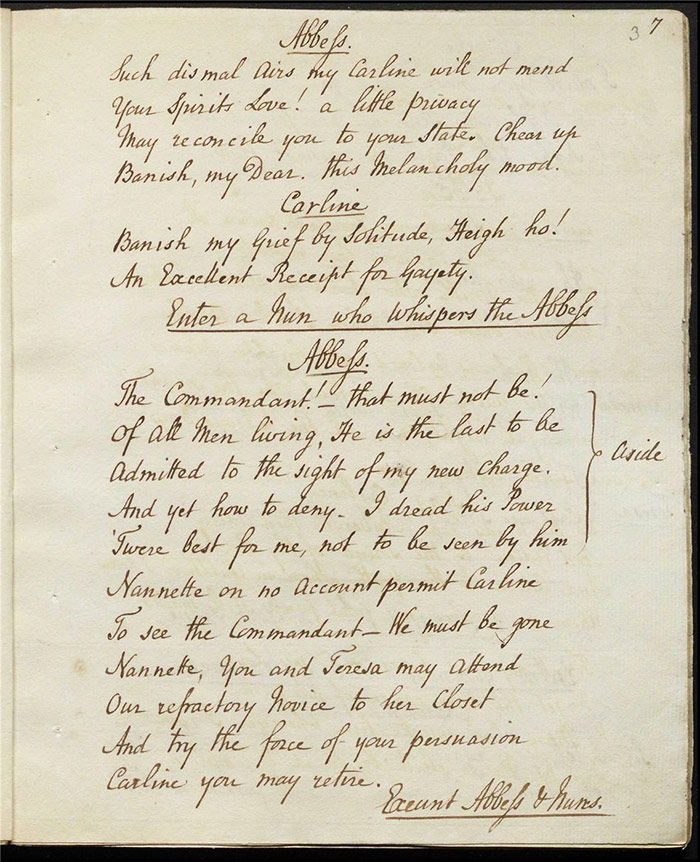

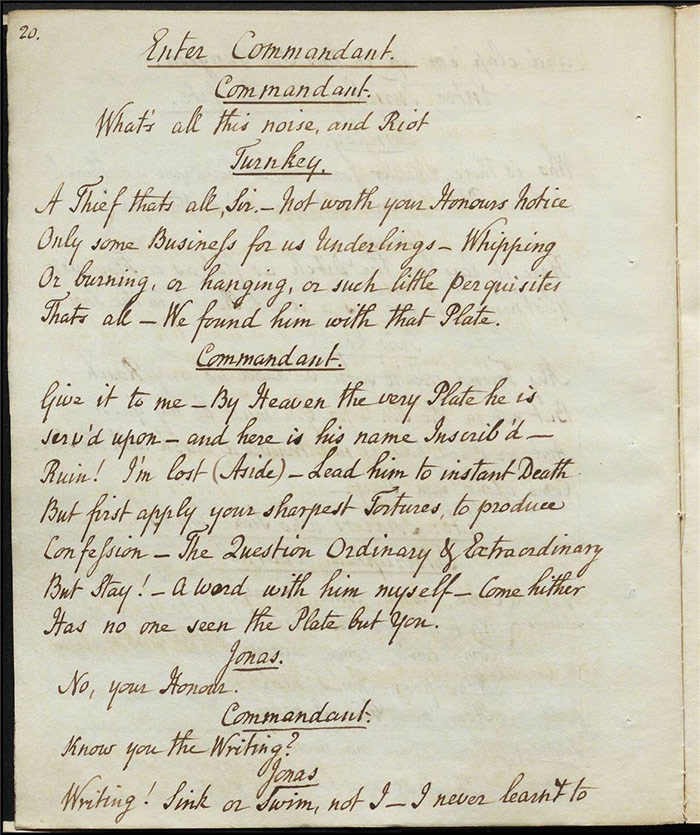

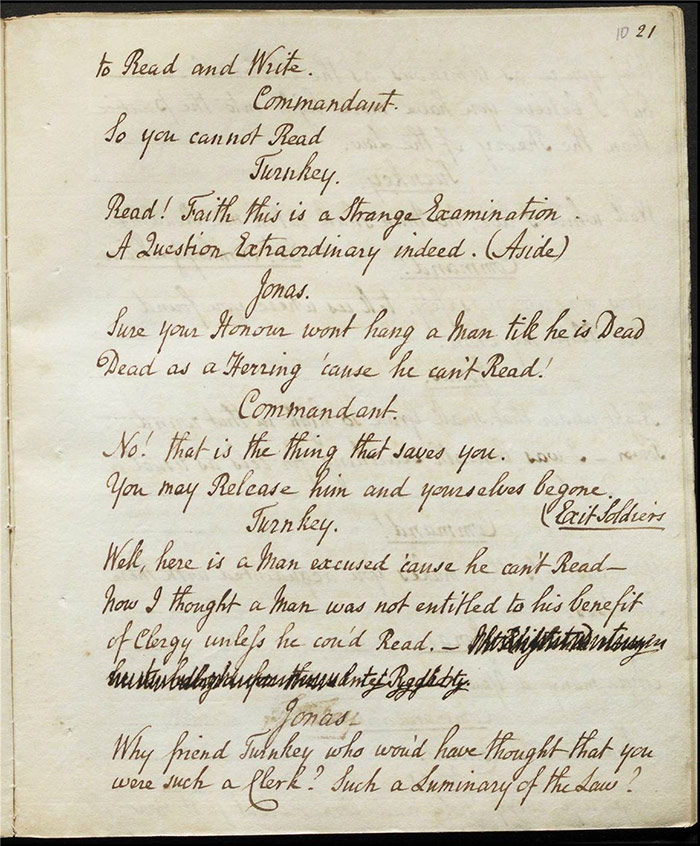

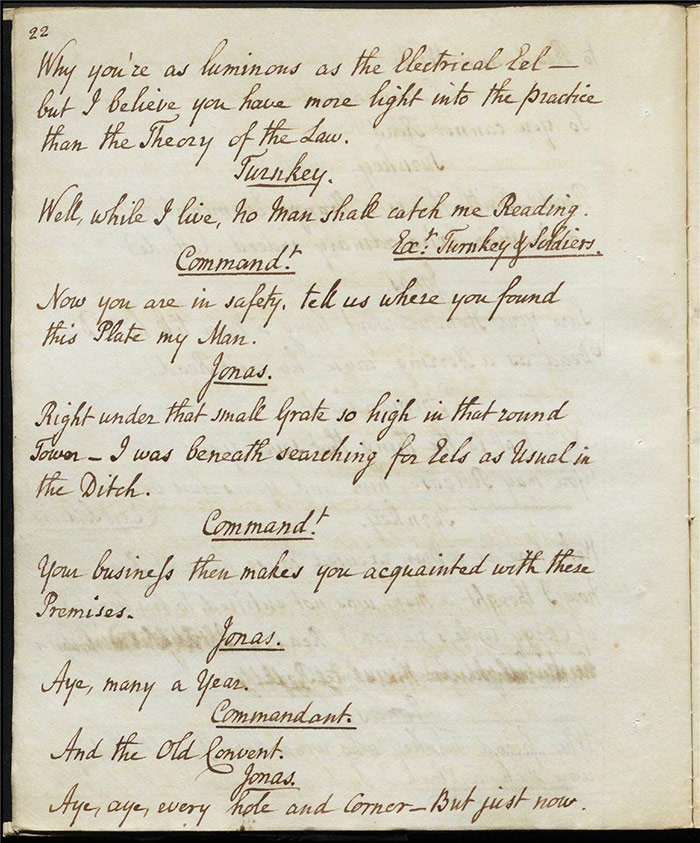

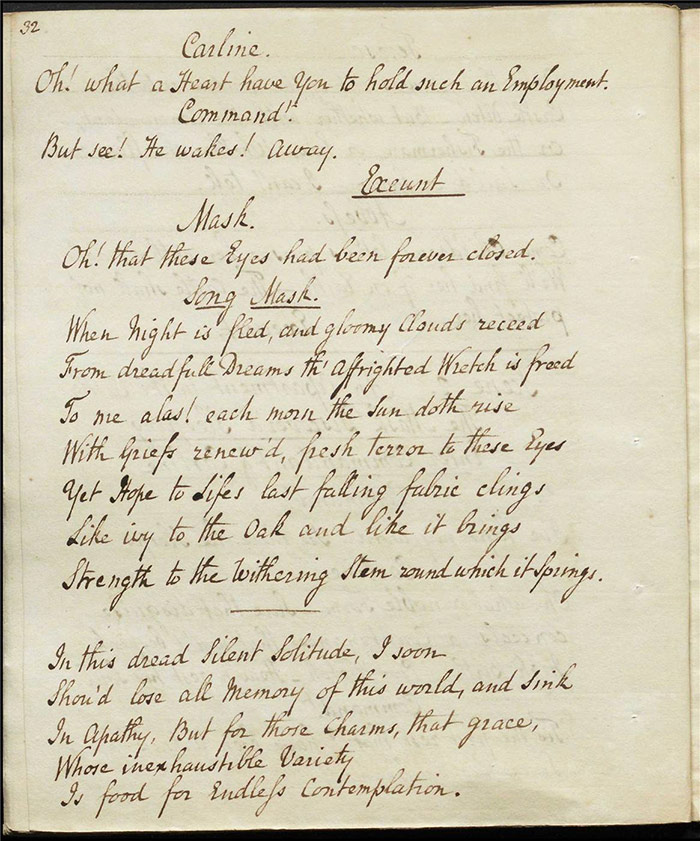

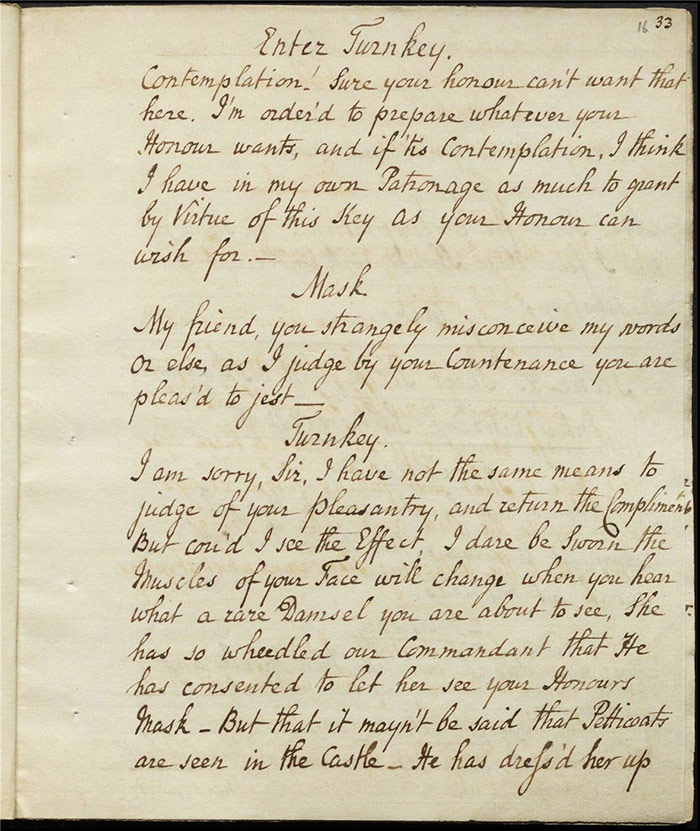

The original manuscript (LA 845) shows several emendations and excisions marked in pen and in pencil. The offending passages and phrases are underlined in pencil and boxed and crossed out with pen. It is probable that John Kemble’s hand provides the marginal instructions ‘To be omitted’ and the associated emendations in pen. Kemble’s emendations corroborate most—but not all—of the pencilled instructions to cut text, so we may surmise with reasonable confidence that the latter were provided by Larpent. The second manuscript (LA 848) is largely a clean copy but there are two deletions heavily marked in pen. One of these is a line that was already marked for excision in LA 845 but the subsequent line is one that had been passed in the original (compare LA 845, f.17v with LA 848, f.21r)).

The fall of the Bastille provoked anxieties in some quarters in Britain about mob insurgency and the threat to the social order. Such fears were commensurate with anxieties about the potential of theatre audiences to morph into mobs and, to use Helen Burke’s phrase, put on their very own riotous performances. The immediate aftermath of the French Revolution thus provides the context into which we must place the Examiner’s treatment of St. John’s play.

The first substantial excision is the Commandant’s observation: ‘Fortunately the times are favourable – The general confusion of the Town, which daily threatens to attack my Castle, may cover the Attempt’ (LA 845, f.5r). The passage is underlined in pencil and is also boxed and crossed out in pen with ‘To be omitted’ written in the margin. Although the comment strikes the modern reader as relatively benign—there is no incitement to action here—it appears that anything that might be construed as even alluding to the events in Paris was problematic. Of course, we should also observe that the Commandant’s intentions towards Carline may not be entirely pure: secondary ideas about sexual violence or the imputation that societal elites may exploit social unrest for their own selfish purposes may have been in Larpent’s mind. The speech does not appear in the resubmission (LA 848, f.5v).

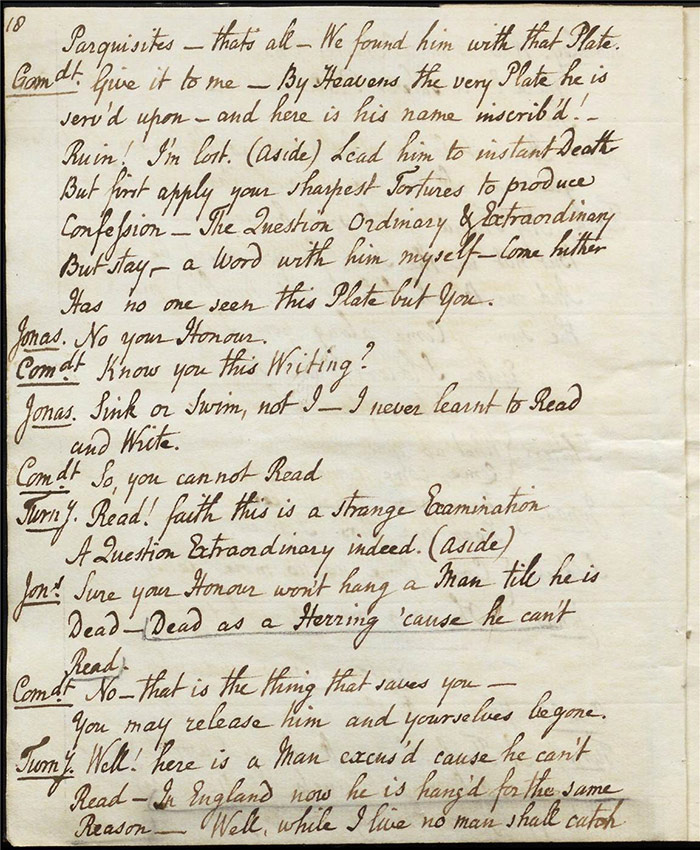

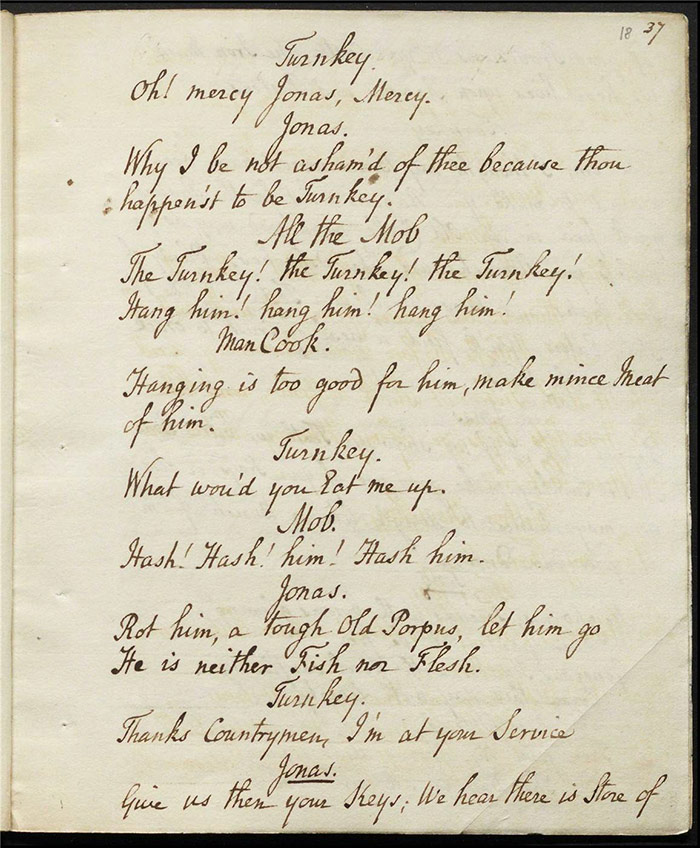

The other deleted passages are aligned along the same theme. The Commandant’s description of horrific prison conditions is marked for deletion in both pen and pencil with ‘To be omitted’ in the margin (LA 845, f.13r) and does not appear in the resubmission (LA 848, f.15v). See also the reference, underlined in pencil, to harsh English law ‘Well! here is a Man excus’d cause he can’t Read. In England now he is hang’d for the same Reason’ (LA 845, f.8v; compare LA 848, f.10r). An extended paean to the rights of men, liberty, and glory as the mob marches on the castle is emphatically boxed in pen and pencil, including a large ‘X’ through the passage with ‘To be omitted’ marked twice in the margin for good measure. It begins:

Generous Hearts assert your freedom Vindicate the Rights of Men To Fame and Glorys Temple lead ‘em Never to return again ((LA 845, ff.15v-16r)

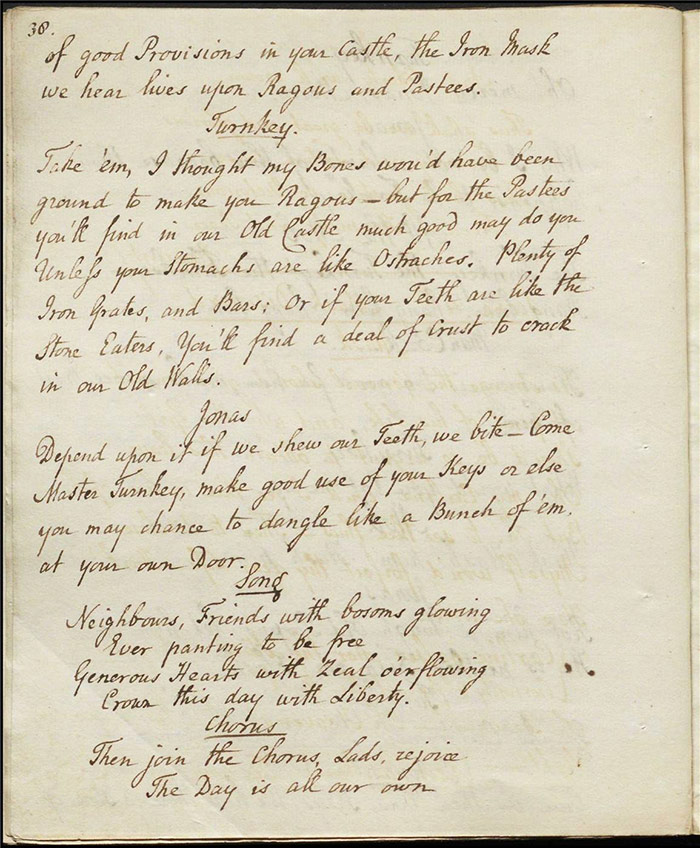

The resubmission also has a song which celebrates liberty but omits any reference to the rights of man/men or the original song’s allusions to downing castles and sacrificing lives. Perhaps critically, it is sung by Jonas alone whereby the first song was sung by the mob chorus. Here is the first stanza:

Neighbours, Friends with bosoms glowing

Ever panting to be free

Generous Hearts with Zeal o’erflowing

Crown this day with Liberty. (LA 848, f.18v).

However, we must acknowledge that an earlier reference to the ‘Sweet Liberty the first best Right of Man’ was not marked for omission, it perhaps being sufficiently nebulous for Larpent once the antecedent mention of ‘all the luxuries of France’ had been corrected to ‘all the luxuries of the world’ (LA 845, f.6v). ‘all the luxuries of France’, nonetheless, is reinserted—without intervention—in the second manuscript (LA 848, f.7v).

The addition of a ‘Lawyer’ to the dramatis personae in the resubmission provides disciplinary restraint on any sense of revolutionary fervour: his sole speech refers to the ‘Gentlemen of the Committee’, ‘illegal’ detention of the man in the mask, and habeus corpus which all lend the proceedings a legitimacy lacking in the first version (LA 848, f.17r).

In arguably the play’s most fascinating example of censorship, a stage direction indicating a ‘Dead March’ has been deleted and underlined in pen with a pencilled ‘X’ beside it as well. The music was to accompany the appearance of the Commandant ‘guarded’ and thus the implication that he was to be executed (confirmed in a second censored stage direction on the subsequent folio) it was not permitted. While it is relatively common for a song’s lyrics or an opera’s libretto to be pruned by the Examiner, it is highly unusual that a generic piece of music would not be allowed (LA 845, ff.17v-18r). In the corresponding scene in the resubmission, the Commandant enters and exits ‘in Procession’ so that any sense that his life is forfeit or indeed in peril is removed (LA 848, f.21v).

A comparison of the manuscripts with the published text will also prove fruitful. To take the final example of the Commandant’s fate, we can see a marked difference in the published version, signalling a retrenchment of St. John’s ambition. In the Commandant’s final appearance, he enters and exits, no longer ‘guarded’, rather he walks on and off stage ‘with Gentlemen’. Moreover, he is also given the opportunity to chastise and regulate the mob: ‘The day is yours, but let not frantic zeal / Transport your mind from liberty to licence; / Let justice then prevail’ (The Island of St. Marguerite, p.30). Along with the addition of the Lawyer character then, the re-imagined fate of the Commandant serves to ensure that the revolutionary tendencies of the piece are transmuted into a more modest celebration of British justice and the restoration of the values of liberty. St. John says that he submitted ‘chearfully’ although he believes more was ‘lost in spirit, than gained in decency’ (p.vi).

Further reading

http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/st-john-hon-john-1746-93

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 87-90.

John St. John, The Island of St. Marguerite: An Opera in Two Acts (London: J. Debrett, 1789)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

_____ A Letter from a Magistrate to Mr. William Rose, of Whitehall, on Mr. Paine’s Rights of Men (London: J. Debrett, 1791)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

G. Le G. Norgate, ‘St John, John (1745/6–1793)’, rev. S. J. Skedd, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/24500, accessed 21 April 2017]