The Election of the Managers (1784) LA 659 / 663

Author

George Colman the Elder (bap. 1732, d. 1794)

Colman was born in Florence, the son of the envoy to the court of the grand duke of Tuscany. His mother brought him back to London in 1733 after his father died. He attended Westminster School where he befriended Charles Churchill and William Cowper, among others, before entering Christ Church, Oxford, in 1751. He began to publish essay in The Connoisseur, a weekly publication he established with Bonnell Thornton, but his major break came when he developed a friendship with David Garrick for whom he wrote a pamphlet praising his abilities.

Garrick staged Colman’s comic afterpiece Polly Honeycombe at Drury Lane in 1760 and he had a major success with The Jealous Wife in 1761. In this same year, Colman and Thornton began the thrice-weekly newspaper the St. James’s Chronicle which had a focus on literary and theatrical anecdotes. When Garrick left London in 1763, this created an opportunity for Colman to get involved with the management of Drury Lane. He continued to write though and he had a big success in 1763 with The Deuce is in him. On Garrick’s return to London in 1765, the pair took up a collaboration again which would become The Clandestine Marriage, an enormous success when it first appeared in 1766 and recognized as one of the great plays of the century today.

Colman took a quarter share in Covent Garden on the retirement of John Rich in 1767 and was involved with the theatre for many years. He sold his share to actor Thomas Hull in 1774 for £20000. In 1776 he agreed to take over the patent of Haymarket for an annual payment to Samuel Foote who wanted to retire.

Plot

The plot of both manuscripts are largely the same. Here the plot of the original submission (refused a licence) is given. The note on ‘Censorship’ will highlight some of the main differences between the plays including, where necessary, those relating to plot.

Buckram is excited to learn that there is to be an election of the theatre managers: Laurel, from Drury Lane (who becomes Holly in LA 663), and Ivy, from Covent Garden, are to join their interest together while Bayes, from Haymarket (i.e. loosely, Colman the Elder himself – Bayes is constantly referred to as ‘Little Bayes’ and Colman was a small man able to laugh at his own shortcomings), will challenge them. Mrs Buckram has arranged for him to become the secretary of the Laurel and Ivy campaign as it would benefit his tailoring business enormously. He will set up in the Piazza Coffeehouse while little Bayes will be in the Bedford. Mrs Buckram then tells him, to his surprise, that she will be canvassing and she encourages him to call out his journeymen to vote even though they do not appear to hold the appropriate property rights to qualify.

Laurel and Ivy enter along with their campaign manager Quirk and they begin to formulate a strategy. They are joined by Canker, Blarney, Supple, and Foolio who comprise the election team. The first three contribute by, respectively, managing the newspapers, organizing election muscle to prevent the other side voting, and getting intelligence on the opposition’s plans.

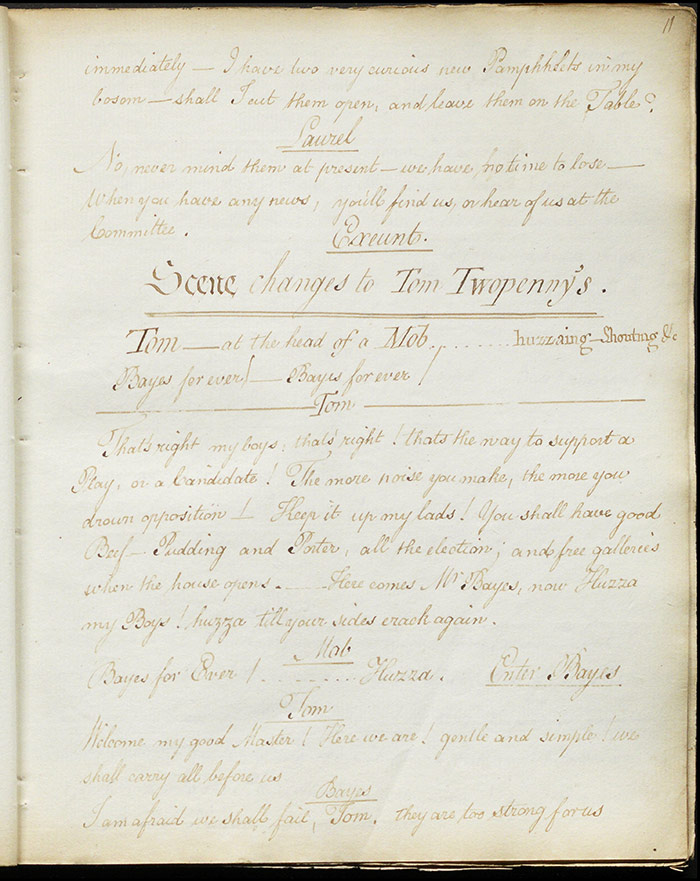

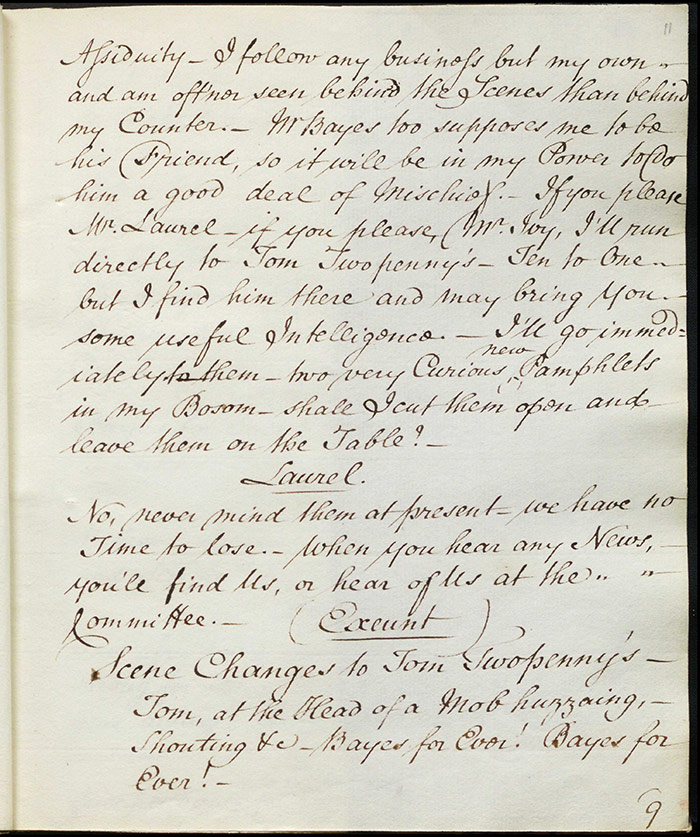

The second scene (f.11r) takes places at Tom Twopenny’s where Tom (‘a Publican, & violent Partizan for Bayes’ as he is described in LA 663 and is identified in the newspapers as representing Sam House, a real-life Foxite activist) is leading a mob. His boisterous confidence energizes Bayes, anxious about the combined power of the two other candidates. Jacky Type, a newspaper man, promises his support as well and also drives away Supple who has arrived looking for information. Mrs Dimple enters and lists the many actions she has taken in support of Bayes, particularly buying products at inflated prices to secure votes.

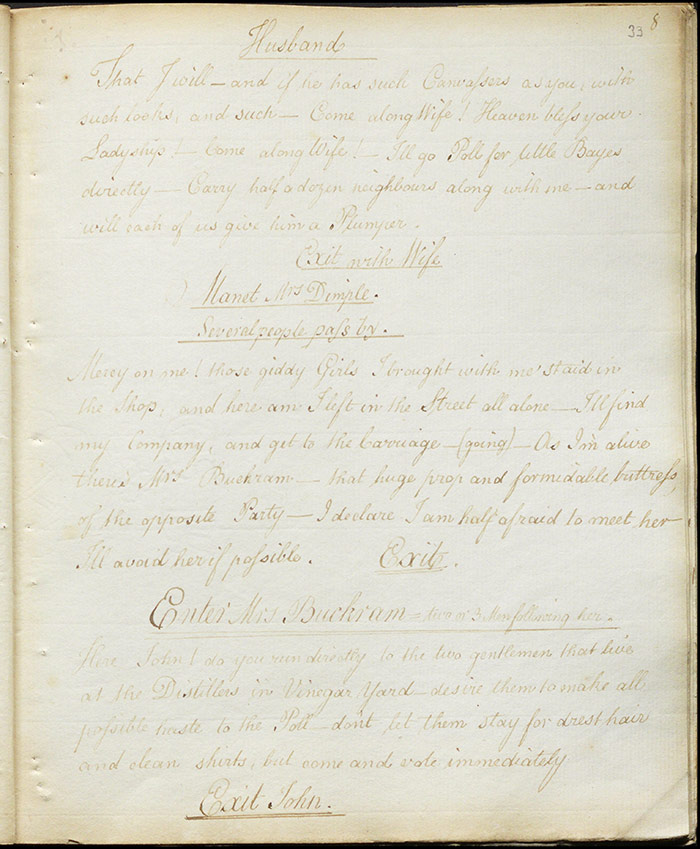

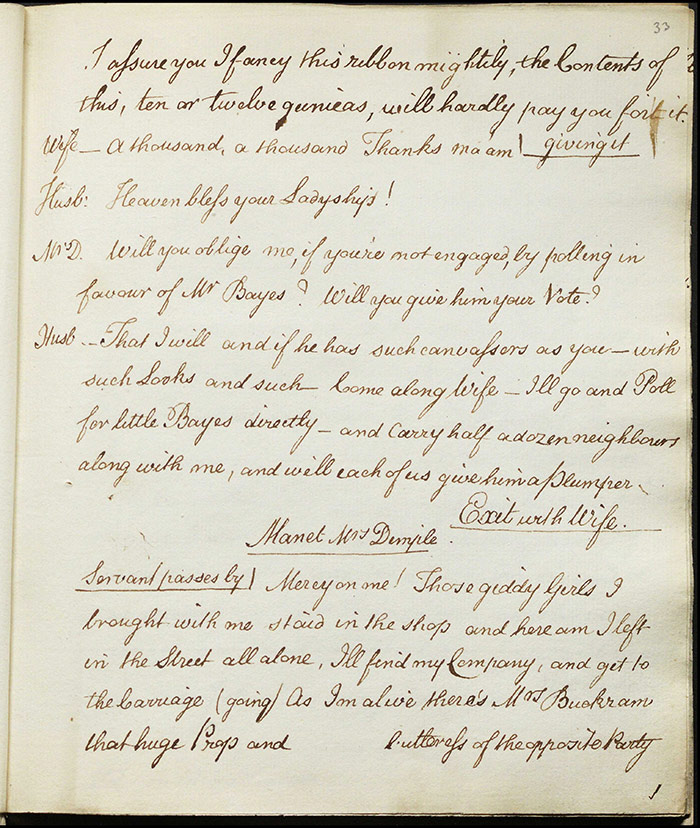

The second act (f.26r) opens on a street near the hustings. Canker is hearing varying reports on how the poll is going. Mrs Dimple manages to cajole a vote but then spots Mrs Buckram approach. The two formidable canvassers clash and exchange increasingly heated insults. Others join the fracas and the tumult continues.

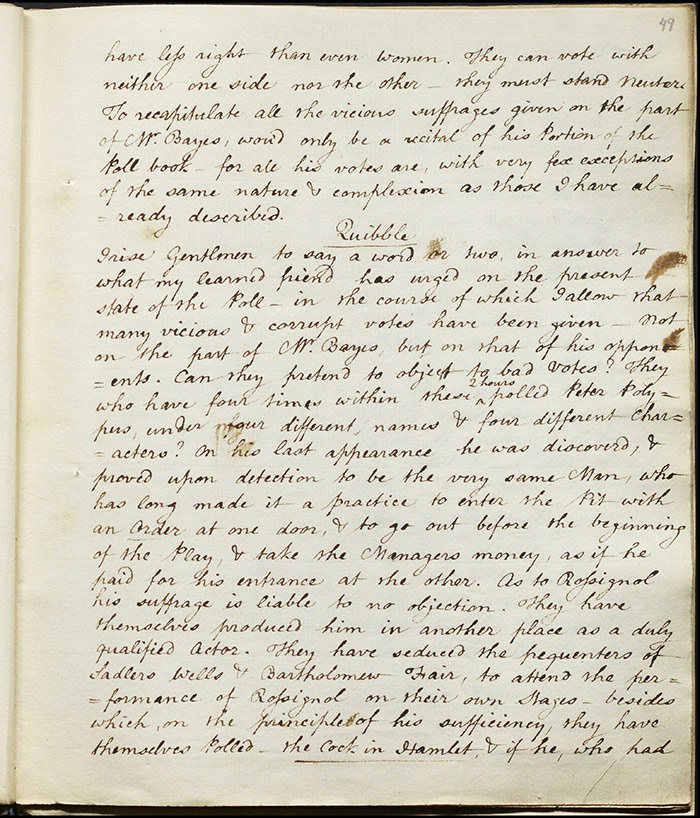

The final scene (f.42r) takes place at the hustings where Blarney delivers a lengthy speech in support of Laurel and Ivy. Counsellors Quirk and Quibble then make various accusations of voter fraud against each other’s parties. The returning officer then declares for Laurel and Ivy but this is immediately challenged by Bayes’s counsel.

Performance publication, and reception

The manuscript of this prelude in two acts was submitted by Colman on 10 May 1784 and it was intended that it would be staged on opening night of the Haymarket Theatre’s season on 28 May. However, due to the Examiner’s objections, it was not performed until a revised version was staged on 2 June and nine further performances took place that season; one of the reviews below suggests that further cuts were made in response to audience criticisms. The piece was unpublished.

The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (3 June 1781) applauds a piece that is even-handed in its politics: ‘There are female canvassers on both sides; there is abuse on both sides; there is bribery on both sides’. This was also the position of the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (3 June 1781) who believed ‘Both parties were agape for incidents or dialogues favourable, or adverse, to their particular inclinations: but both parties were in this instance disappointed, for it is impossible to discover the bias and party of the author’. A later review from the same newspaper (5 June) notes with approval that some passages have been omitted ‘that on the first representation gave offence to the over-squeamish’ but there is no indication as to which passages are being referred to here.

The St. James’s Chronicle (1-3 June 1781) is keen to applaud the play but is dubious as to the references to real people. To be precise, the newspaper is fine with references to personages such as Sam House:

But every Insinuation respecting a certain Lady of elevated Rank, and of the highest Excellence of Mind and Character, which the Author has personated by the Widow Dimple [i.e. Duchess of Devonshire], is of the utmost Importance to a Publick by which he has been ever admired and beloved.

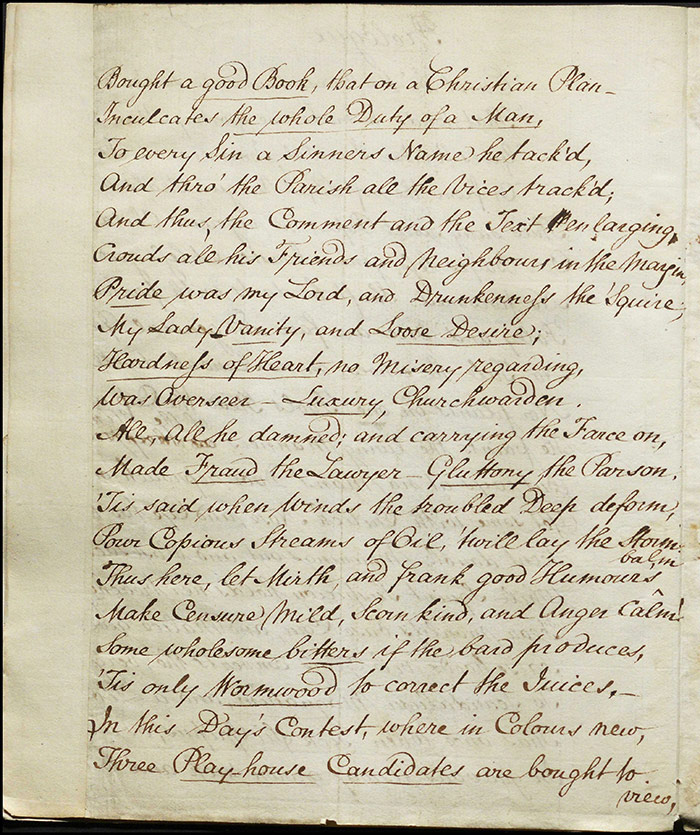

The London Chronicle (1 June 1781) is more emphatic regarding the ‘unpardonable indecencies’ where ‘respectable characters from real life are brought forward’. The writer is particularly exercised by the representation of the two main female characters and he claims that ‘The grossness of these personalities drew from the audience the strongest marks of disapprobation’. However, even this reviewer had high praise for the prologue which was roundly applauded by all the newspapers, some even suggesting it was Colman’s finest.

Commentary

The original manuscript (LA 659) shows several emendations and excisions marked in pen. Typically, the offending phrases are underlined and it is probable that these are Examiner edits although it may be the manager/author’s pen who inserts alternative text in some cases. The second manuscript (LA 663) also includes a number of passages marked in pen although in these instances the passages are typically boxed. It is striking that many of the passages highlighted for removal in LA 659 are resubmitted in LA 663 and we might speculate as to what this might mean. It may be that this is simply a breakdown in communication between Colman and his copyist who simply replicated what he had done the first time. However, there are differences in the dialogue of the two manuscripts which make this very unlikely. What is more likely is that the excisions made in LA 663 are made by Colman before resubmission to Larpent. This is supported by the different method of excision (boxing as opposed to scoring out or underlining). It also provided Colman with the ability of demonstrating to Larpent that he was taking on board the required changes. A new manuscript was required in this case as there were changes to dialogue, a prologue was added, and a song for Tom Twopenny is added.

The play’s interest from a censorship perspective derives from the satiric attacks on London’s electoral culture. To understand the interventions made, one needs to be aware of the 1784 election which saw William Pitt the Younger secure an overall majority for the first time. The election was contested between March and May and it was a particularly hard fought parliamentary election in the borough of Westminster in 1784. Charles James Fox was a sitting MP for the prestigious borough and he fought the campaign against two Pittite suporters, Cecil Wray and Samuel Hood. The borough was a two-seater but when Wray finished bottom of the pile, he called for a scrutiny, a delaying tactic which prevented Fox from taking his seat until May when parliament demanded that the returning officer call the election. The election campaign itself was marked by much rancour and, somewhat scandalously, saw the involvement of women: the Duchess of Devonshire canvassed on behalf of Pitt while Albinia Hobart did so on behalf of her cousin Cecil Wray. James Hartley can give us a sense of the indignation of some contemporaries:

The many ill-natured, illiberal, and scandalous insinuations that have been thrown out against the Duchess of D——e, on her friendly and spirited behavior during the Election for Westminster, rather indeed deserve contempt than serious refutation. Had the authors reflected on her conduct, as espousing a different cause, it might have been pardonable; but from thence to insinuate a want of virtue and modesty, which are confined to no party, betrays a littleness of mind and ideas as contracted as the narrow sphere of life in which they move. Her exertions to serve Mr. Fox have, it seems, provoked a poetaster in the newspapers to lament the degeneracy of female virtue and modesty; yet is he so ignorant of the human heart, as not to be able to judge wherein they consist. He sets out upon the most absurd principles; that is, he imagines that virtue and modesty are only to be found among the great, or else he could not condemn her as lost to those virtues, only because she visits the poor. With regard to her permitting a kiss from a butcher, it is much more likely to be false than true, and considering her, as she really is, a woman of character, there is no doubt but that she knows how to behave as such, and to repel any improper liberty that may be offered; however, our correspondent will for the present suppose it were true; to what then does the crime amount? (History of the Westminster Election), 344)

Given the regular parallels drawn between the worlds of theatre and politics, it is unsurprising that Colman saw the opportunity to draw an analogy between himself and Fox as underdogs while also revelling in the opportunity to mock the political process, exposed as being rancorous and corrupt. Equally, it is no surprise that the Examiner of Plays saw fit to suppress many of the most explicit references, particularly those that could be tied to particular individuals, such as kisses offered by the Duchess of Devonshire. Although Larpent had recently passed Macklin’s The Man of the World with much of its attack on Scottish venality intact, the incidents of the Westminster election were far too fresh in the mind and many of its principal actors still very much in the public eye for it to be unscathed. On the other hand, as the newspapers demonstrate, it was very evident to all concerned that the Duchess of Devonshire and Albinia Hobart were being mocked: an outraged London Chronicle (1 June 1781) complained that ‘Mrs. Webb being the most rotund lady in the Haymarket catalogue’ played Mrs. Buckram. Hobart’s obesity made her a target of satirists, who often compared her to a beefsteak, so there was little doubt to contemporaries as to who was being invoked.

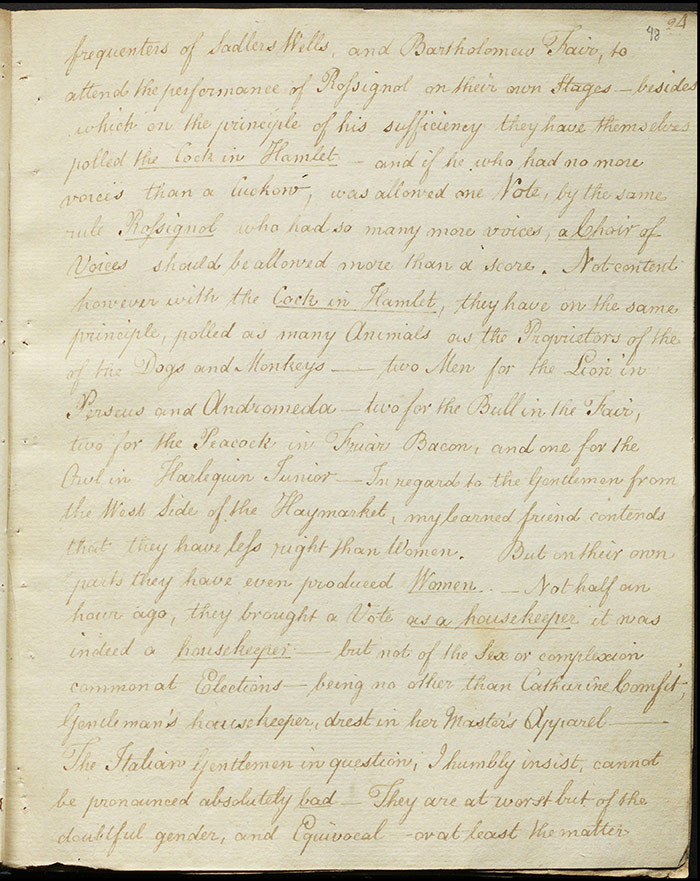

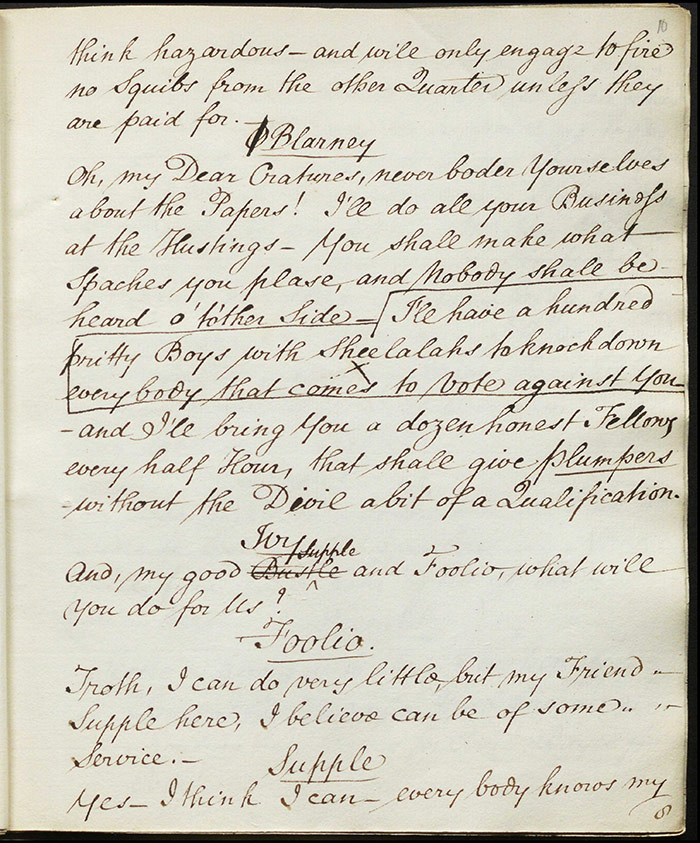

References to electoral violence and unqualified voters appear underlined on (LA 659, f.10r) when Blarney, the Irish muscle for Laurel and Ivy, declares: ‘I’ll have a hundred pretty boys with Sheilalah’s [sic] to knock down every body that comes to vote against you – and I’ll bring you a dozen honest fellows every half hour that shall give you Plumpers without the divil a bit of a qualification’ (when a voter voted for only one candidate and waived their right to cast a vote for another candidate, their vote was then strengthened or ‘plumped’). The second manuscript also marks the reference to violence for removal but leaves in the reference to the plumpers of dubious qualification (LA 663, f.10r) raising the question of whether this is an oversight on Colman’s part of whether he was trying to sneak it past Larpent.

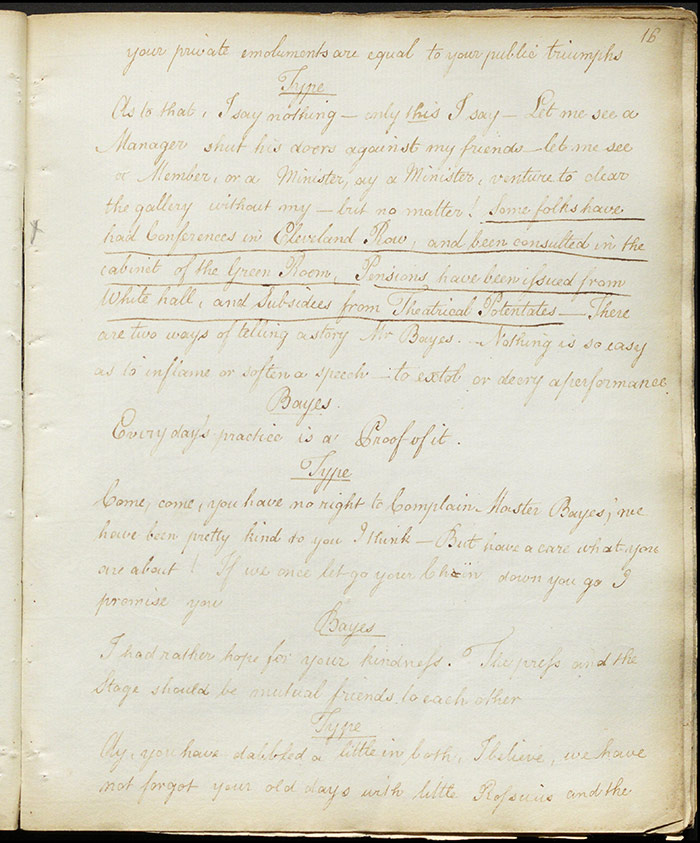

A later reference by Bayes to the king’s press being misused ‘most damnably’ is also underlined for removal (LA 659, f.12r) as are vague references to government subsidies and pensions (LA 659, f. 18r) which also reappear in (LA 663, f.18r), also marked for omission. There is a reference to ‘poor Lord Flimsey’s money’ that needs to be removed so begging the question as to the identity of Lord Flimsey (LA 659, 23r). See the same reference deleted again on (LA 663, f.23r)

There is a fascinating phrase underlined on (LA 659, f.16r) when Bayes says to his newspaper friend Jacky Type ‘Nothing like Sincerity – A Friend in Need, is a Friend indeed’. This must be a mischievous reference to Dennis O’Bryen’s play of the same name which had played at Haymarket in 1783. The play, also concerned with Fox, as I have argued elsewhere, had been the cause of a very public spat between Colman and O’Bryen, carried out in the newspapers, over the financial terms of their agreement. For Colman to include a sly dig at O’Bryen’s ‘sincerity’ in the voice of the character meant to represent himself is amusing but it does pose the question as to whether the underlining is from the Examiner (and thus Larpent recognized the dig and demanded its removal in line with the usual practice of removing references to real people) or from Colman (and thus the underlining is for emphasis). As the line reappears in (LA 663, f.19r) the underlining is almost certainly for emphasis. Whether Larpent simply missed this personal jibe—references to real people are almost always prohibited— or whether he felt O’Bryen was not worth protecting will remain a matter of speculation.

Awareness of the reference to O’Bryen’s play is also possibly helpful in reading the character of Blarney and his ‘hundred pretty boys’ and the threat of violence. Hartley describes an Irish contingent at the heart of the real-life Westminster electoral fracas just before it exploded into fatal violence:

[…] during the time of the Election, which lasted many days, an immense croud [sic] of people assembled on the Hustings, I need not tell you that there was a great deal of clamour, and of noise, as there is at all Elections; at one end of the Hustings, crying out Fox for ever, no Wray, at the other end of the Hustings, crying our Hood and Wray for ever, no Fox; some of the Gentlemen, friends to Mr. Fox, used the House known by the sign of the Unicorn, between Henrietta-street, and the end of the Hustings; at that House likewise from time to time assembled a great body of Irish chairmen, Welch porters and others, armed with sticks and bludgeons […] on one day towards the close of the Poll, a body of them were incensed, because some persons would not call out Fox for ever, and all at once as if in consequence of a signal given, they drew their bludgeons, and flew instantly on the people. (History of the Westminster Election, 381)

Hartley is recounting the opening speech for the prosecution counsel in the trial for the murder of Nicholas Casson, a constable beaten to death on 10 May 1784. The transcript of the trial, given in Hartley, is fascinating in itself but the most striking fact is that Dennis O’Brien, as his name is spelt here, is indicted and acquitted for the murder. There was then a frisson of violence around O’Bryen that Blarney echoes here: Colman, it would appear, did not forget their spat in a hurry.

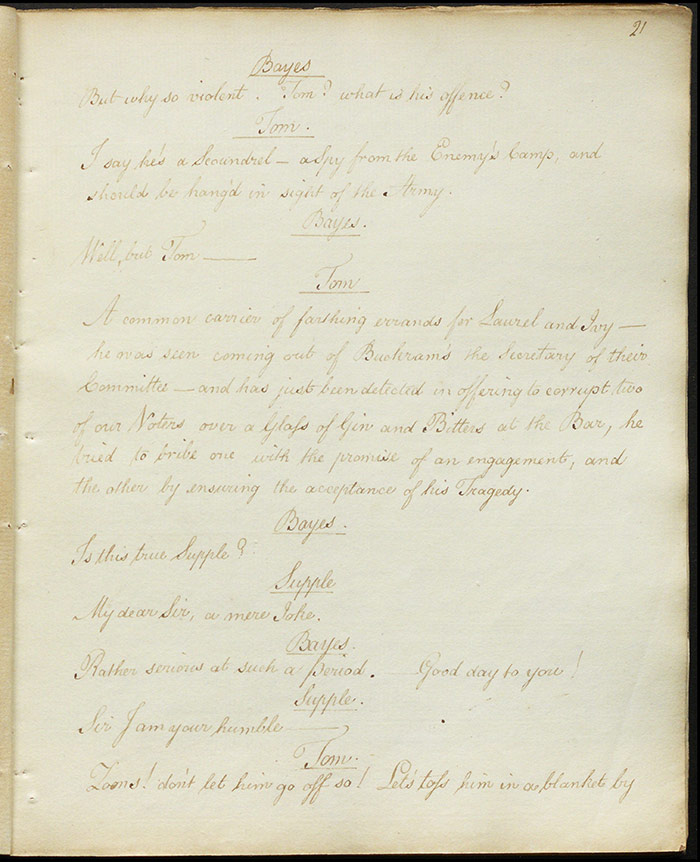

Another reference to the Fox election occurs on (LA 659, f.20r) when Tom Twopenny accuses Supple of being a rogue: ‘Search him who know’s but he has a poison’d bag about him’. This was a reference to a bag of euphorbium (first thought to be asafoetida) being thrown in Fox’s face during a struggle at the hustings in Westminster Hall on 14 February. There is also a reference to ‘Judas Iscariot’ underlined on this folio, a biblical reference rarely being acceptable. Both these references are marked for omission again on (LA 663, f.21r)

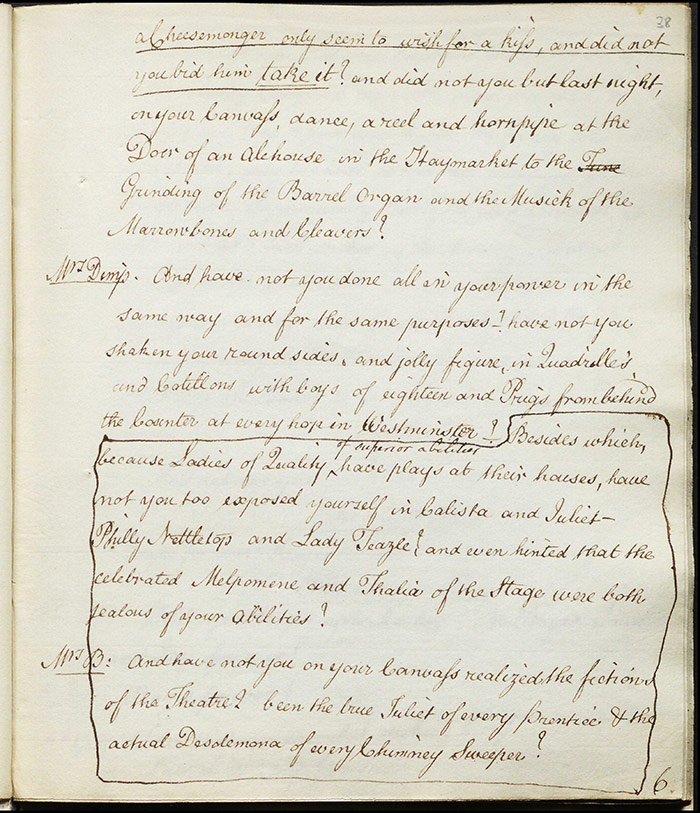

Naturally, references to the Duchess of Devonshire and her alleged ‘kisses for votes’ style of canvassing appear in the row between Mrs Dimple and Mrs Buckram. Mrs Buckram demands of her opponent ‘and there is not a Voter, qualified to take his seat in the twelve penny Gallery, on whom you have not lavished your guinieas [sic], your tears, ogles, kisses and embraces & attractions where the superscript is an insertion after the excision. Shortly afterwards, she further asks ‘did not a Cheesemonger only seem to wish for a Kiss, and did not you bid him take it?’ (LA 659, f.37r) As these marked passages appear on the same folio and one is scored out while the other is underlined, it is possible that one is from the hand of the Examiner while the other—probably the first passage—was scored out by a manager/author less confident, in hindsight, that the allusion to the Duchess would get past the Examiner. These same passages appear, also marked for omission, on (LA 663, f.37r-38r).

More deletions follow on the next folio where references to ‘Ladies of Quality’ acting in private theatricals and further references to amorous liaisons between such ladies and apprentices and chimney-sweeps are underlined (LA 659, f.38r).

Finally, there is a puzzling deletion in both manuscripts (LA 659, f.28r) (LA 663, f.28r) where it is difficult to see what might be objected to by the Examiner. It may be that this is simply an editorial cut by Colman (supported by the fact that it is marked differently in LA 659 than other Examiner cuts) but this remains unclear.

Further Reading

Olive Baldwin, Thelma Wilson, ‘Colman, George, the elder (bap. 1732, d. 1794)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/5976, accessed 15 April 2017]

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 129-132.

Dorothy George, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires, 11 volumes (London: British Museum, 1938), VI: 37, 39-40.

[on Fox and the sneezing bag]

James Hartley, History of the Westminster Election, Containing Every Material Occurrence, from its Commencement on the First of April, to the Final Close of the Poll, on the 17th of May… 2nd edition(London: J. Debrett et al, 1785).

[available on Google Books]

David O’Shaughnessy, ‘Making a play for patronage: Dennis O’Bryen’s A Friend in Need is a Friend Indeed’, Eighteenth-Century Life 39:1 (2015), 183-211.

[on Dennis O’Bryen, his relationship with Fox, and the spat with Colman]

Richard Brinsley Peake, Memoirs of the Colman Family, 2 vols (London: Richard Bentley, 1841), II: 159-62

[available on Google Books)

David Francis Taylor, ‘Theatre Managers and Theatre History’, in The Oxford Handbook of Georgian Theatre, 1737-1843 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 70-88, esp. 83-84.