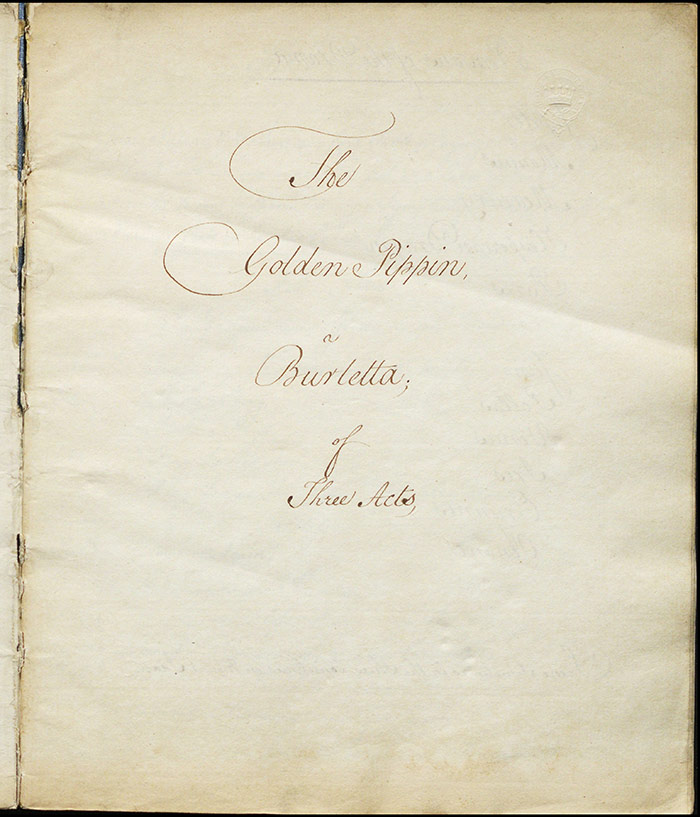

The Golden Pippin (1773) LA 330 / 339

Author

Kane O’Hara (1711/12-1782)

O'Hara was born in Sligo and studied at Trinity College Dublin, 1728-1735. O’Hara co-founded the Dublin Academy of Music in 1757, along with Lord Mornington, Garrett Wellesley, professor of music at Trinity College and father of the future Duke of Wellington. O’Hara also served as one of the Dublin Academy’s officers which met weekly at the Fishamble Street Music Hall to prepare charitable concerts.

He had his first professional success with Midas, an English Burletta which was performed at Crow Street Theatre, Dublin in 1762. The piece was a response to an Italian burletta, from the D’Amici family, which had delighted Dublin audiences in December 1761. Midas had been performed privately in 1760 and O’Hara was encouraged by Lord Mornington to respond to the Italians and bring it forward. It was a success not only in Dublin but in London where it was performed over 200 times by 1800.

The Golden Pippin was his second venture into burletta and April Day (Haymarket, 1777) and Tom Thumb (1780, Covent Garden) were to follow. His The Two Misers: a Musical Farce (Covent Garden, 1775) was an adaptation of de Falbaire’s Les Deux Avares.

Another charitable venture began in 1775 when he opened Mr Punch’s Patagonian Puppet Theatre on Abbey Street, Dublin. The theatre was a success and it moved to London in 1776 where it performed burlesques, ballad operas, and burlettas until 1781. He became blind in 1778 but he remained, as he had long been, a popular figure in Dublin society until his death.

Plot

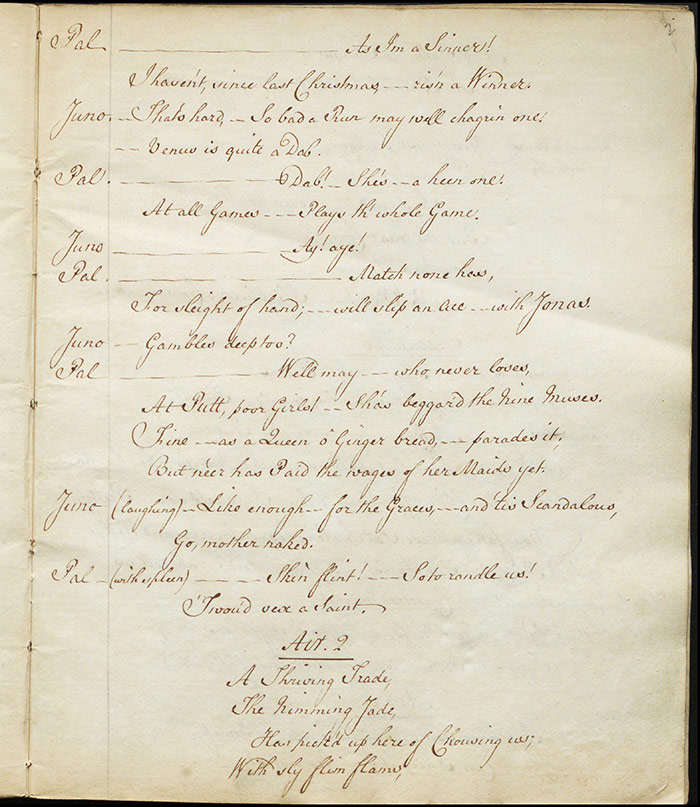

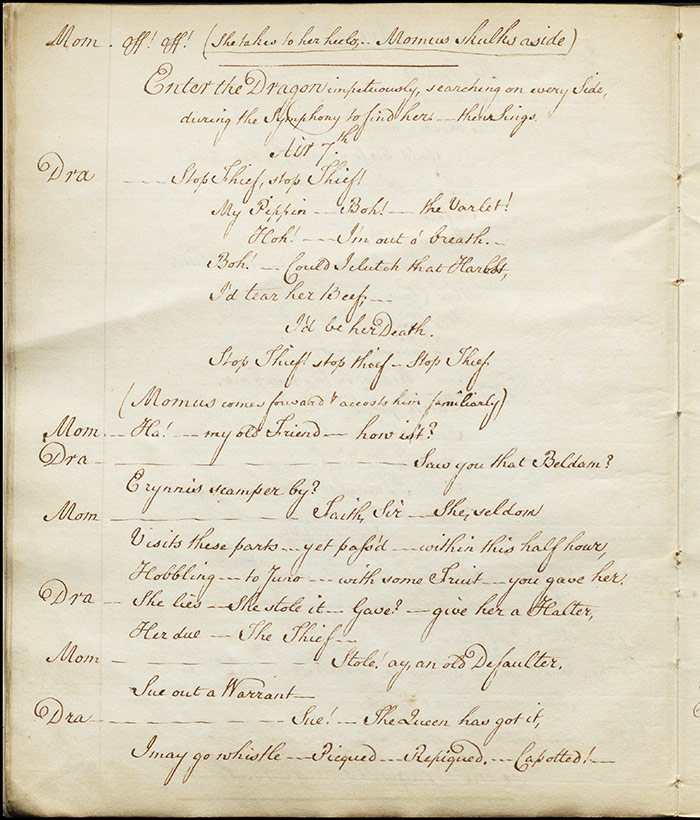

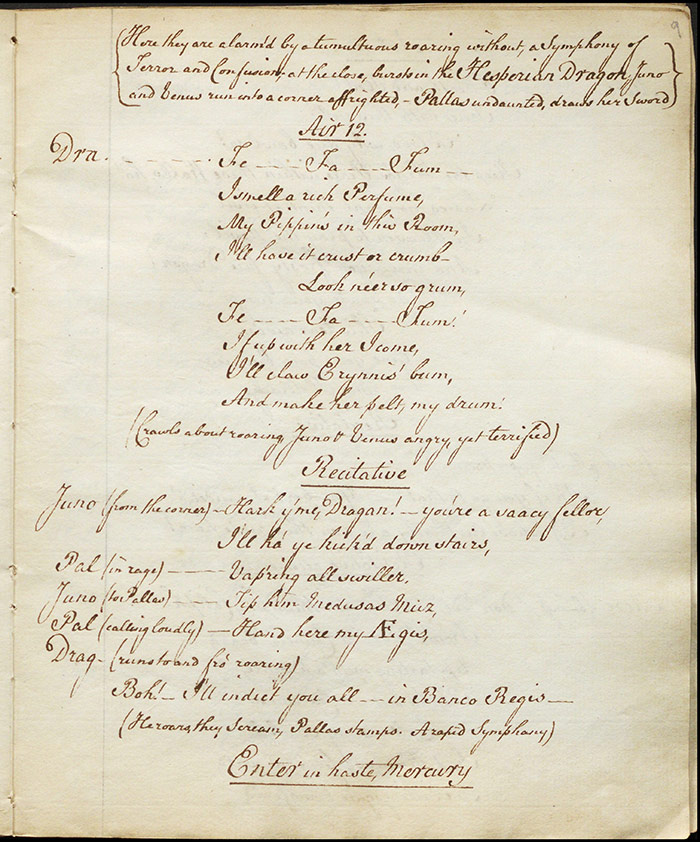

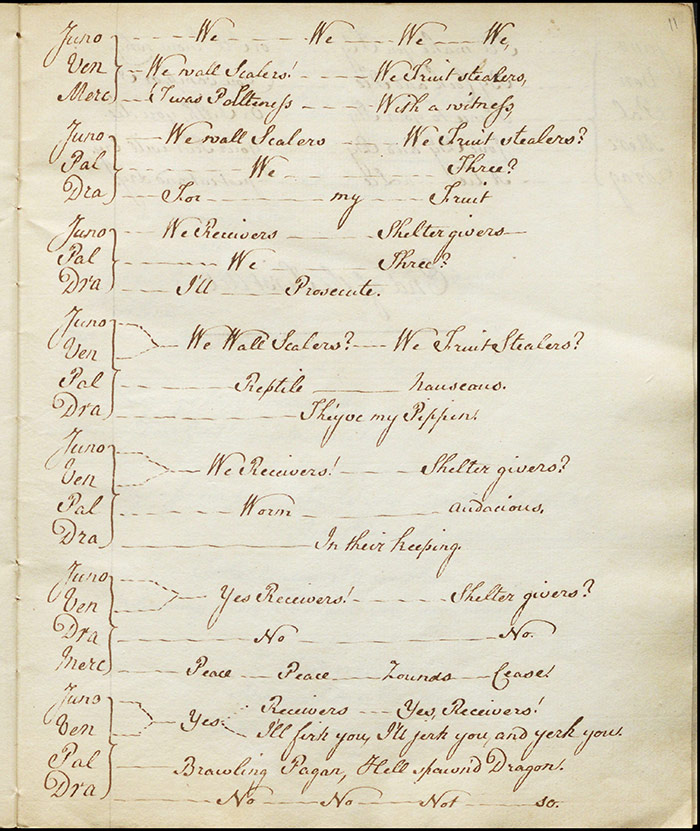

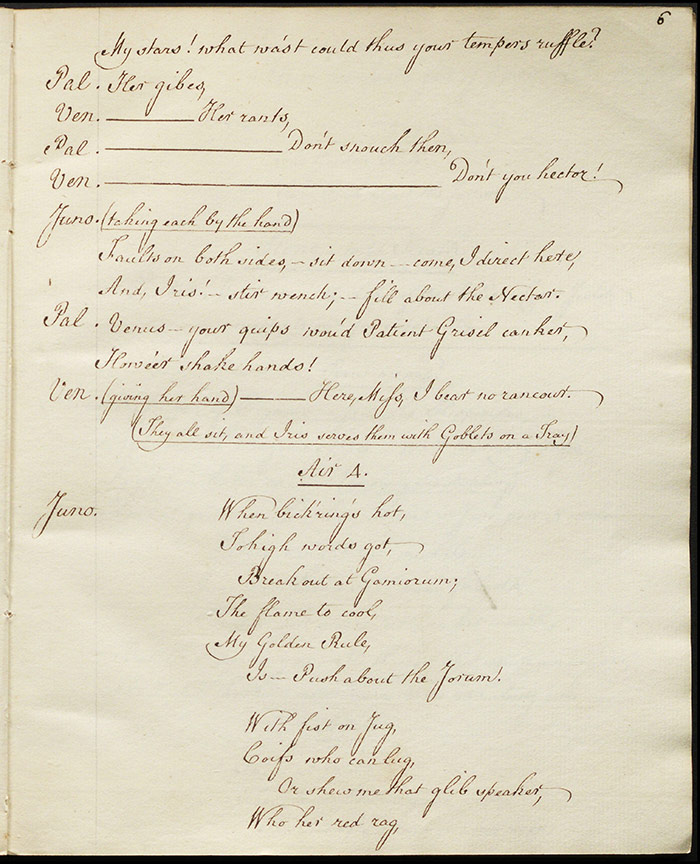

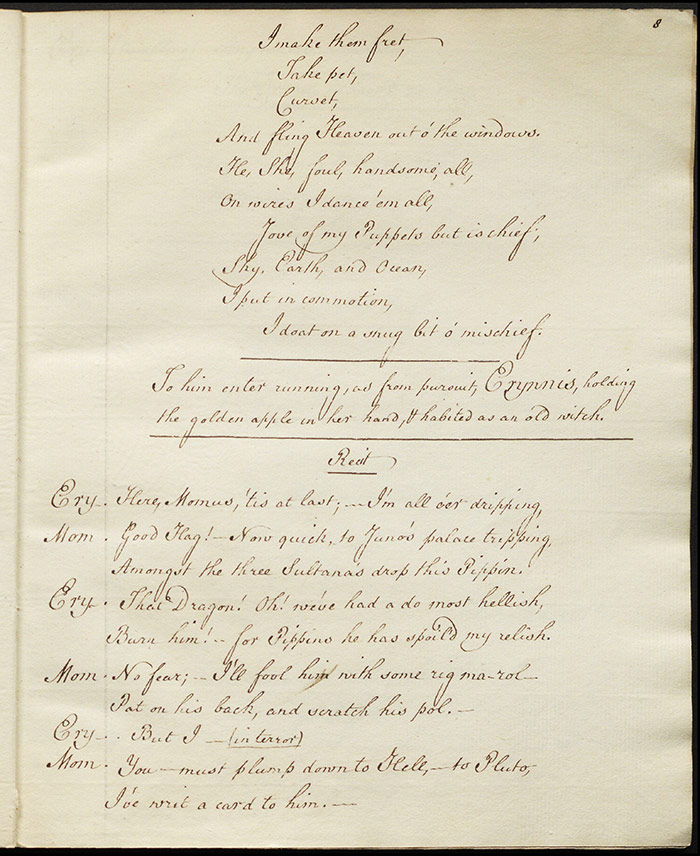

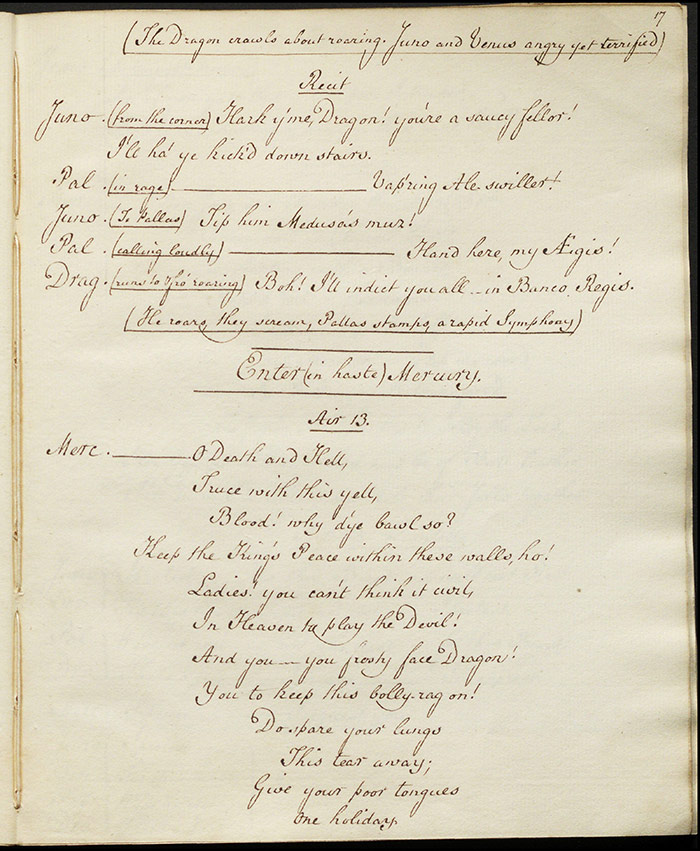

The burletta retells the story of Paris and the golden apple. Pallas, Juno, and Venus squabble after a game of cards. Momus, dressed as a jester, decides that he wants to throw the golden apple among them in order to stir up a heaven that’s ‘grown damn’d hum drum’ (f.4f). The apple duly arrives, courtesy of the witch Erynnis who has stolen it from the dragon, who is hot in pursuit in turn. After the apple is delivered to the gods and they begin to contest it, the dragon challenges them for the prize. Mercury tries to keep the peace but the first act ends in some tumult.

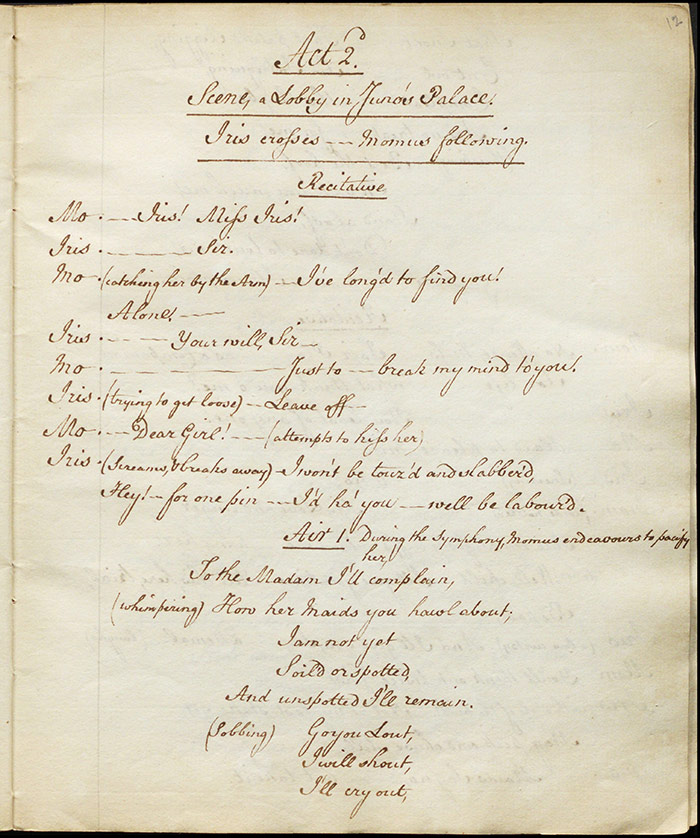

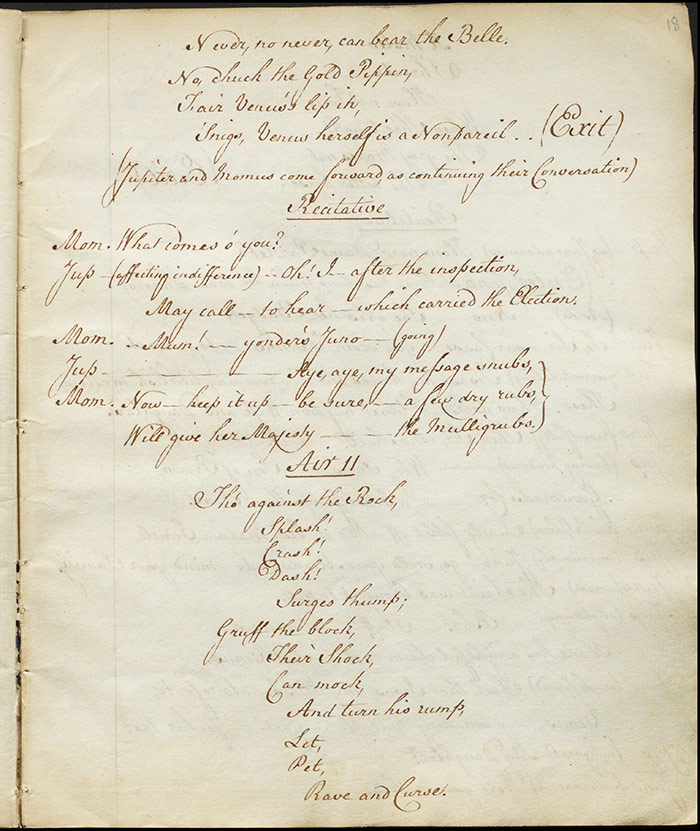

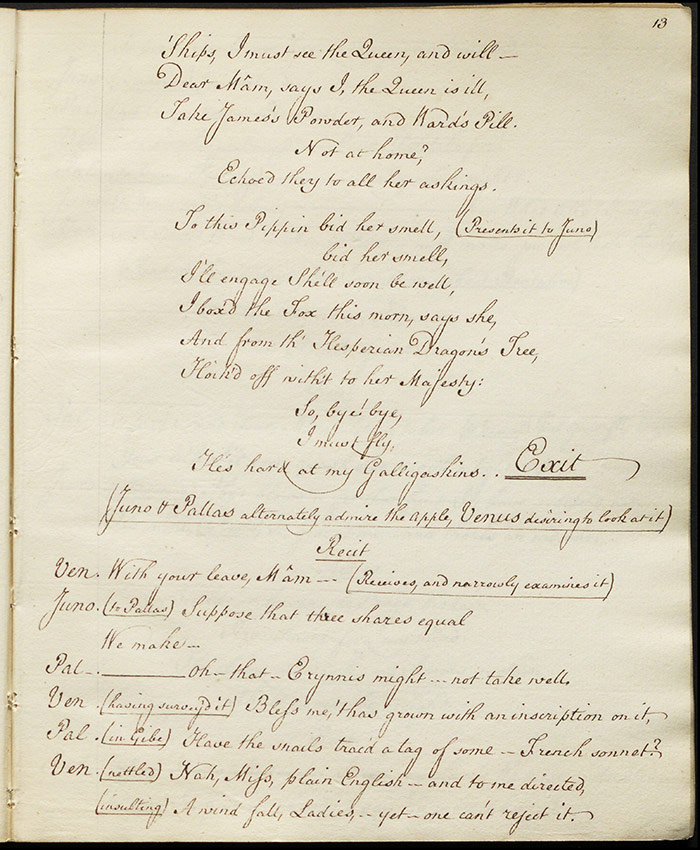

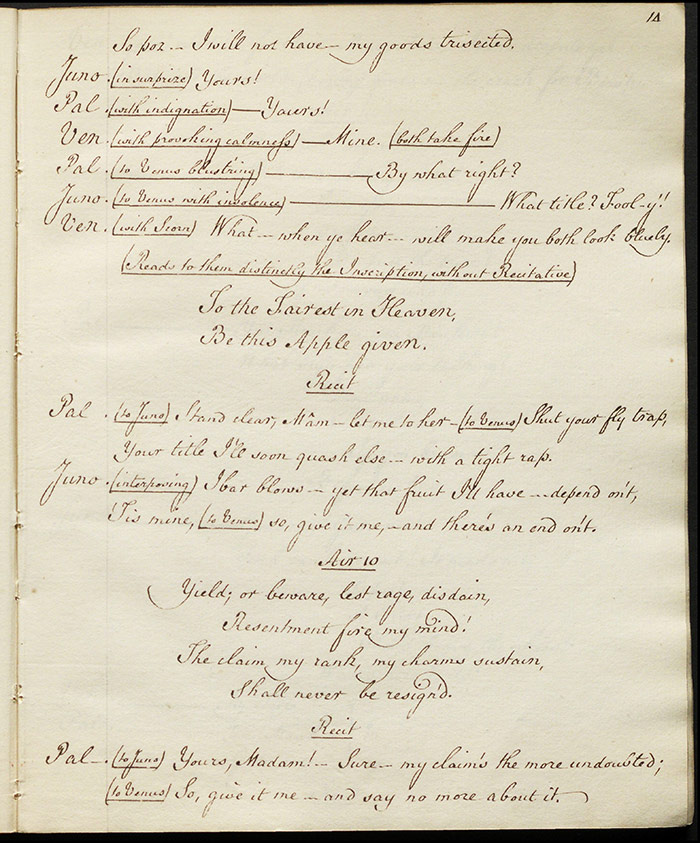

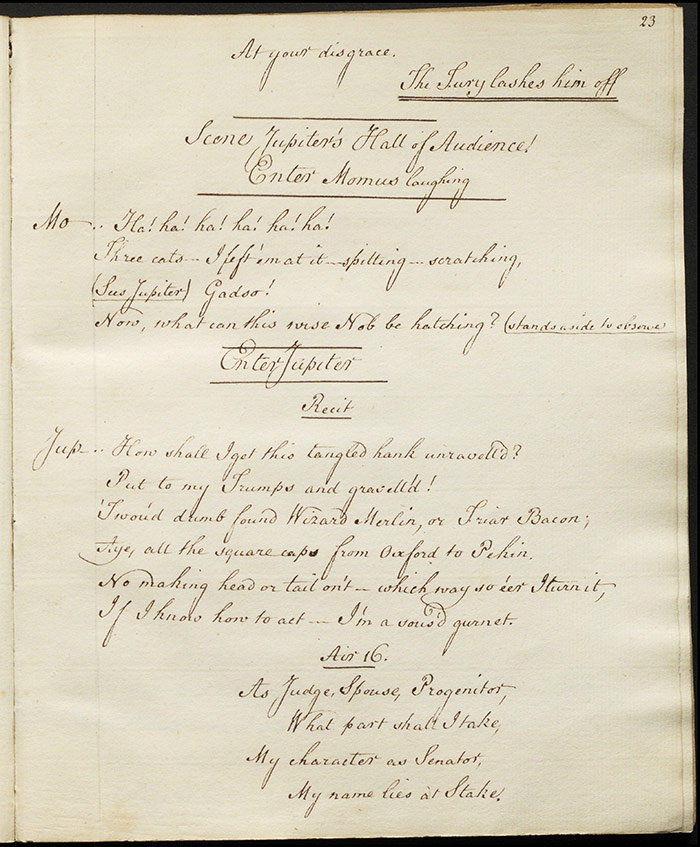

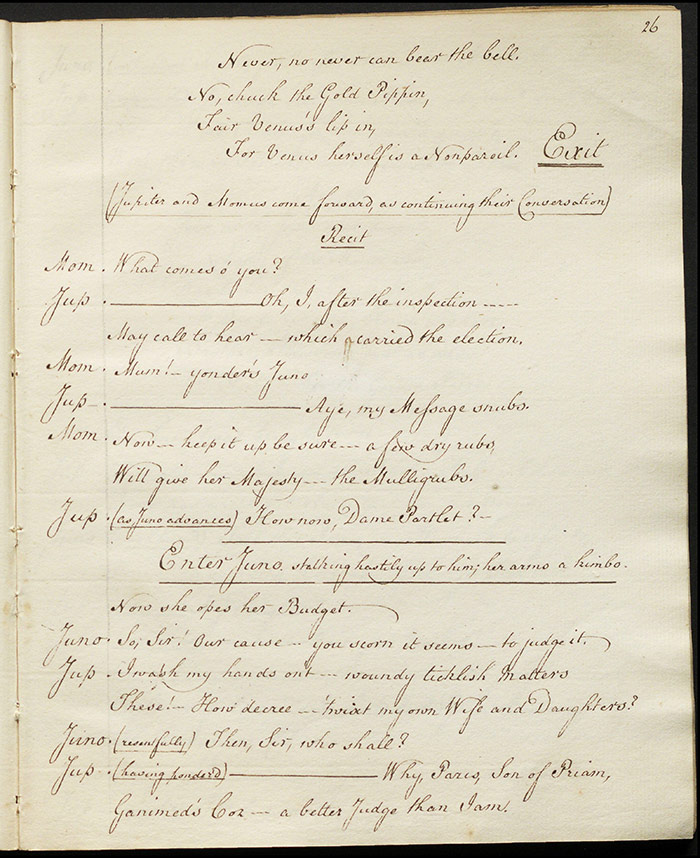

The second act (f.12r) begins with Momus trying to woo Iris, maid to the gods, unsuccessfully. The dragon has been arrested and is led off in chains by one of the Furies. On Mount Ida, Oenone the nymph is mourning the faithless love of Paris whom she has not seen in months. Paris enters ‘fantastically’ and ‘full of the most affected Coxcomical airs’ (f.14v); she is delighted but he is dismissive, acting the fop. Jupiter is unable to decide how to resolve all this clamour and Momus suggests that he ask a mortal to make the choice and Jupiter settles on Paris. The act concludes with a marital dispute between Jupiter and Juno.

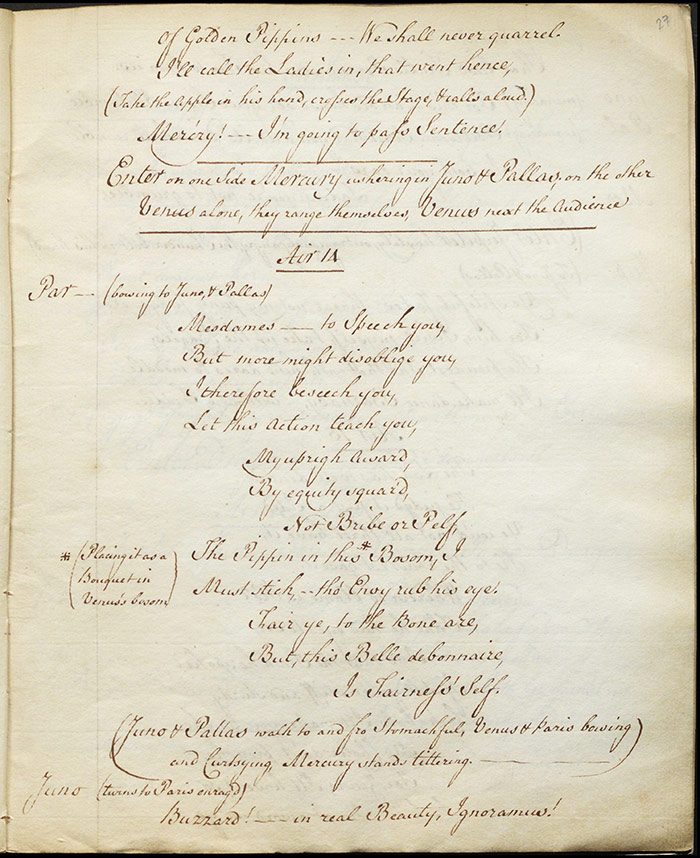

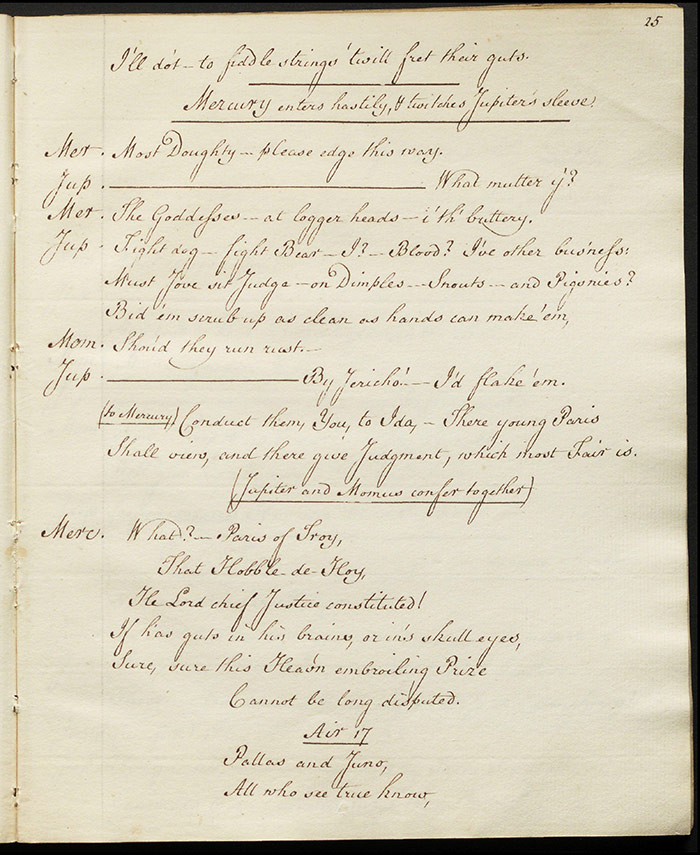

The third and final act (f.20r) sees Jupiter, in his palace, pleased with the assertion of his authority over the quarrelling women. He has put in a good word with Iris on behalf of Momus. While on Mount Ida Paris is telling the heat-broken Oenone that he is done with her. After she flees, Mercury tells Paris he is to give the apple ‘To the fairest’ (f.22r). The three goddesses make their pitch to Paris in turn and he chooses Venus. Jupiter is forced to protect Paris from the enraged losers. He commands the dragon be set free and the piece ends with a final multi-part air sung by the major characters.

Performance, publication and reception

Midas was submitted to the Examiner’s office on 5 February and ‘forbid’ on 17 February 1772 as is noted on the manuscript. The piece was resubmitted on 9 October 1772 and was first performed on 6 February 1773 at Covent Garden. Subsequent performances occurred on 8 and 9 February before the play was substantially rewritten for a performance on 12 February: the characters of Erynnis and the Dragon were omitted and the piece was cut to only two acts. The move seems to have paid dividends as there were a further six performances over the remainder of the season.

As we might deduce from this brief performance history, the initial burletta was not well received by its audiences. The newspapers are helpfully detailed as to the reasons for this lack of enthusiasm. The General Evening Post (6-9 February 1773), having witnessed two performances, concludes that it was a ‘species of composition too light for the principal entertainment of an evening’. The paper went on to insist that ‘The British nation require their drama to be as substantial as their food; whipt syllabubs will not on any account be received amongst them as a first course [i.e. a mainpiece]’. Yet we should note that the reviewer had some sympathetic words as to the inability of the audiences to appreciate the particular idiosyncrasies of both the burletta and the burlesque, observing that those critics of vulgar language being deployed by elevated characters (the Greek gods) had previously admired similar language in O’Hara’s Midas. The review sums up ‘Surely then to be charmed with the language of Midas, while we are offended with the language of the Golden Pippin, betrays more caprice than good sense, and throws no little imputation upon the candour of the opposers’.

The London Chronicle (6-9 February 1773) likewise records the audience’s disapproval of the low language of the piece ‘put into the mouths of the most dignified personages’. The writer also notes that some elements of the audience were not keen on the Dragon although no further explanation is offered. Finally, this review offers an interesting insight into theatre and audience negotiation as well as indicating how audience censorship could affect theatrical pieces on a structural level and not just in getting particular lines excised:

‘[…] though the majority favoured the piece, the contest for and against it was so tumultuous at the conclusion, that the Farce was not permitted to be performed until Mr [William] Smith (after Mr. [Henry] Woodward had attempted to speak several times) came on the stage, and informed the audience that the Burletta should be withdrawn as a piece of three acts, but that the Managers hoped that they would permit it to be played for the Author’s benefit; this proposal met with applause, and put an end to the dispute.

The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (8 February 1773) offers the most robust defence of O’Hara, arguing that it is the ignorance of certain sections of the audience that put paid to the piece’s success:

‘[…] the boxes and the pit enjoyed the laugh the piece was designed to create, and expressed great satisfaction; but the Galleries, who cannot bear to be talked to in their own style, were offended at the unchastness [sic] and indelicacy of the language, and expressed much displeasure that other Gods and Goddesses should speak as vulgarly as themselves’.

The writer goes on to argue that the audiences—or at least the uncouth elements of it—simply did not understand burlesque burletta and they were far too rigid and inflexible as regards what might be acceptable. British audiences, unlike foreign audiences, demanded either comedy or tragedy and very pure versions of both. In this, it is suggested, they were mistakenly retarding the development of British theatre:

No man in his senses would desire that burletta would take the place of the regular comedy; but surely, to create a variety, they may be occasionally produced, provided they are not absolute ribbaldry [sic], and merely give us the language, and not the fun of [washwoman]. At any rate, their station with us should be that of farce; as grotesque caricatures they should come after, not in the place of, the real comic picture.

O’Hara’s The Golden Pippin divided those who saw it but the reaction of different parts of the Covent Garden audiences reveals the complicated nature of Georgian audience responses as well as the limitations of the state-operated censorship regime.

Commentary

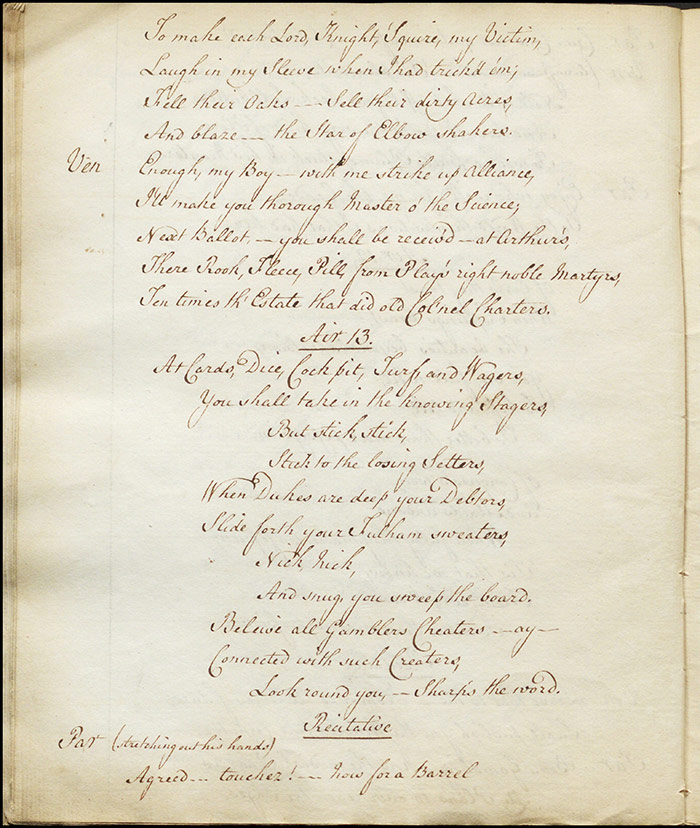

The manuscript of the first version is quite a clean copy with only one intervention. This occurs on (LA 330, f.23v) where an exchange between Paris and Juno is bracketed and scored out with a red inked pen:

Par. (tripping familiarly to kiss her) Ma’am, by your favour.

Juno (with indignation) Meat for your Lord, [I thought you better knew me.

Par. (aside) La fiere! A three pil’d Pride consume me.

Juno You’re a king’s son, but poor as a Church mouse is,

Without the Quids, high birth not worth a louse is.

Par. (aside) Home truths, morbleu!

Juno (eyeing him sharply) ] Aren’t you then not, Prince, ambitious of Pow’r and Wealth?

The excision was most probably made by Capel: the neat writing and the use of red ink is quite distinctive. The introduction of the change from ‘Aren’t you then’ to Are you not’ introduces a small element of doubt (such a minor changes suggests someone editing for reasons other than censorship) but it is possible that Capell simply could not resist the desire to correct the writing. These disparaging references to the monarchy and aristocracy were cut for political reasons; however, this was not, as Conolly has observed in some detail, not the reason for the denial of the performance licence. It seems evident then that Capel communicated his concerns to Colman through a supplementary interview or letter, a further indication that the Larpent manuscripts do not always contain the full extent of the state censor’s interventions.

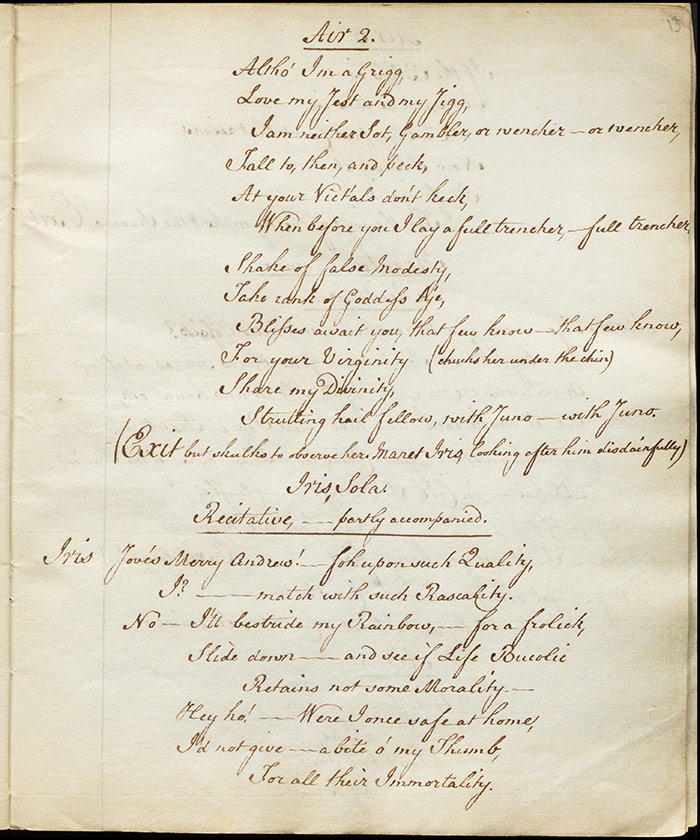

Rather, the most substantial rewriting relates to passages which were bawdy or suggestive. The line where the Dragon threatens to ‘claw Erynnis’ bum’ (LA 330, f.9r) is amended to ‘I’ll strike Erynnis’ dumb’ (LA 339, f.16r). A significant chunk of the burletta—two entire scenes in fact—have also been deleted. The first (LA 330, ff.12r-14v) has Momus attempting to woo Iris, albeit rather forcefully. The passage includes his salacious invitation to her ‘For your Virginity / Share my Divinity’ (LA 330, f.13r). Yet we might also observe that the Dragon’s line (in the second half of this scene) where he complains ‘Why did I trust a Courtier’s Promise?’ (LA 330, f.13v) is also lost in the revision so there were political elements, as well as moral, at play here. The second scene omitted is where Paris brushes off Oenone’s plea to marry him (LA 330, ff.14r-15v). Here it would seem that Capel did not like the suggestion that life at court was:

Ranting and flaunting,

Flirting and Jaunting,

Dressing Gallanting,

Routs, Balls, enchanting

All Joy and Sport. (LA 330, f.15r)

Equally, Iris’s observation that ‘Gods — Men — Trim Tram — Below — above Stairs, / No Barrel better Herring’ (LA 330, f.15v) dissolved class differences rather more than Capel was prepared to allow and does not appear in the revised version. A bawdy song from Momus which ends with Jupiter replying ‘I was a green horn then — — No Penetration’ (LA 330, ff.17rv) is also omitted from the later manuscript.

Perhaps the most significant cut is the removal of much of the decisive and lengthy exchange between Venus and Paris when she is making her case for the apple (LA 330, ff.25v-26v). Her description of Helen’s physique is forthright and proved too much for Capel:

Shes so buxom and fresh,

Such a sweet bit o’ flesh,

Ads life you’ve no Idea,

How She’s form’d to delight,

Both the Touch and the sight,

She’s a Peerless Dulcinea.

Smoother and white as an egg,

And as right as my legg,

High train’d, knows all her paces,

She’s an Olio of Joy,

Say the word, jolly Boy,

And you’re smack –– in her good Graces (LA 330, f.25v)

In summary, it is evident from a comparison of both manuscripts that Capel believed the general tendency of the burletta’s first version was inappropriate. Moreover, this tendency was suffused throughout the piece to the extent that he did not feel obliged to mark each objectionable passage separately. That he made the effort to single out one passage and delete it might indicate that he simply wanted to make doubly sure that the sanitized version would not retain these political lines: if Colman/O’Hara were concentrating on the morality of the revision, Capel needed to be sure they would remember to expunge these lines as well. Yet the performance and reception history of the play reminds us once again both that the censorship history of the play does not stop at the Examiner’s Office and that he was not able to anticipate—or perhaps was not overly concerned—about the objections of some sections of the Georgian audience. The fact that the second version—LA 339—was passed through his office without any marks or excisions at all did not prevent considerable opposition from many who attended the performances.

Further Reading

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 148-51.

Phyllis T. Dircks, The eighteenth-century English burletta (Victoria, British Columbia: English Literary Studies, 1999).

K. O'Hara, Two burlettas of Kane O'Hara: Midas and The Golden Pippin: an edition with commentary, ed. Phyllis T. Dircks (New York: Garland, 1987).