The Man of the World (1770)LA 311

Author

Charles Macklin (1699?-1797)

One of the most well known Irish figures in London over the course of his remarkably long career, Macklin’s early years are a matter of some hazy speculation. After a spell at Trinity College Dublin as a ‘badgeman’, that is, a servant, he moved to England where he became a jobbing regional actor around 1720. An opportunity to take on some leading roles came about in Drury Lane in 1733 and Macklin’s career began to progress. He gained a certain degree of notoriety in 1734 when he was convicted of the manslaughter of a fellow actor after a backstage scuffle over a wig: an unexpected result of this was that he gained a taste for the law and the remainder of his career would see him involved in some high profile cases where he would represent himself.

When Macklin took on the role of Shylock in 1741, he interpreted the role in a radical fashion. Against much opposition from his colleagues and the public, Macklin consigned the buffoonish figure of recent years to obsolescence and portray a dynamic and pernicious moneylender that became his biggest success. ‘This is the Jew / That Shakespeare drew’ Pope was supposed to have commented when he saw it. It was a part he would play for almost fifty years.

While Macklin is best remembered for this career as an actor, he also penned a number of plays over the course of his career which achieved varying degrees of success. Undoubtedly, his comedies Love à la Mode (1759), The True-Born Irishman (1767), and The Man of the World (1781) were his most successful plays, registering both critical and commercial success. His other known works are Henry VII; or, The Popish Impostor (1746); A Will and No Will (1746); The New Play Criticiz’d (1746); The Fortune Hunters (1748); an adaptation of John Ford’s The Lover’s Melancholy (1748); Covent Garden Theatre (1752); and, The Married Libertine (1761).

Macklin led a rich and varied life. He spent time in Dublin, at one stage almost setting up a theatre there in collaboration with Spranger Barry, the Irish actor. He also established a ‘School for Oratory’ in London in 1754 but this was not a success. In later life he was involved with the Benevolent Society of St Patrick, ostensibly a charity but equally, if not more importantly, a networking forum for ambitious and patriotically inclined Irish in London. Always paranoid that publishing his plays would lead to him missing out on performance royalties, Macklin resisted calls to publish his plays for a long time but an edition by subscription of Love a la Mode and The Man of the World was finally published by fellow Irish dramatist Arthur Murphy in 1793 for Macklin’s benefit. An impressive £1582 was raised by a lengthy subscriber list of people from the worlds of politics, fashion, and politics, an indication of the renown in which Macklin was held. He died in 1797.

Plot

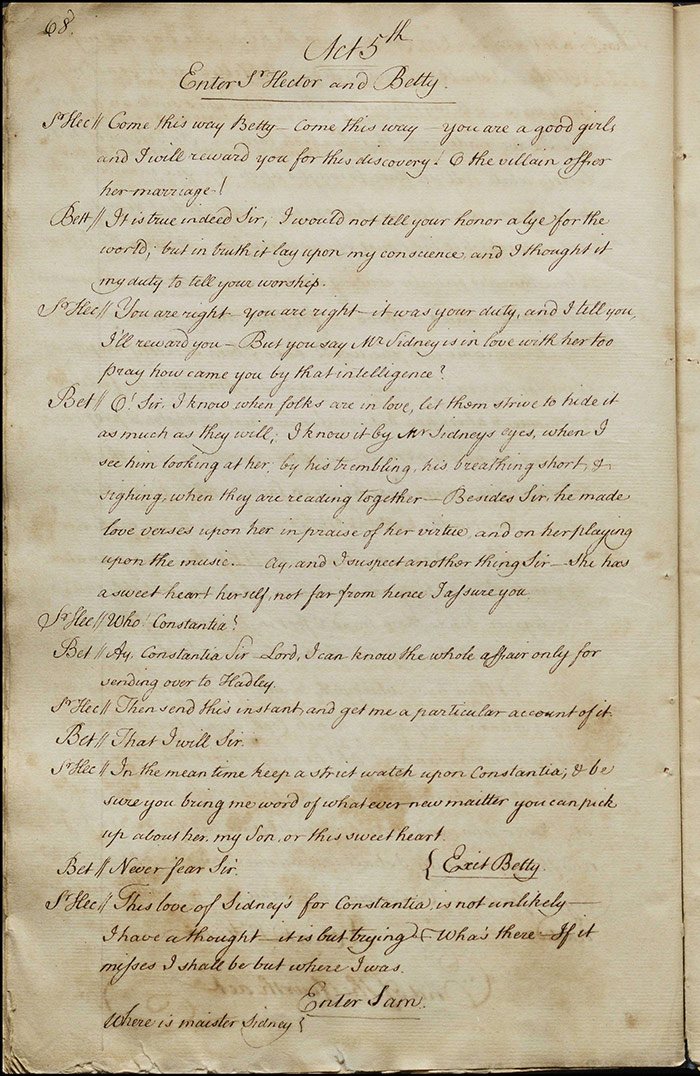

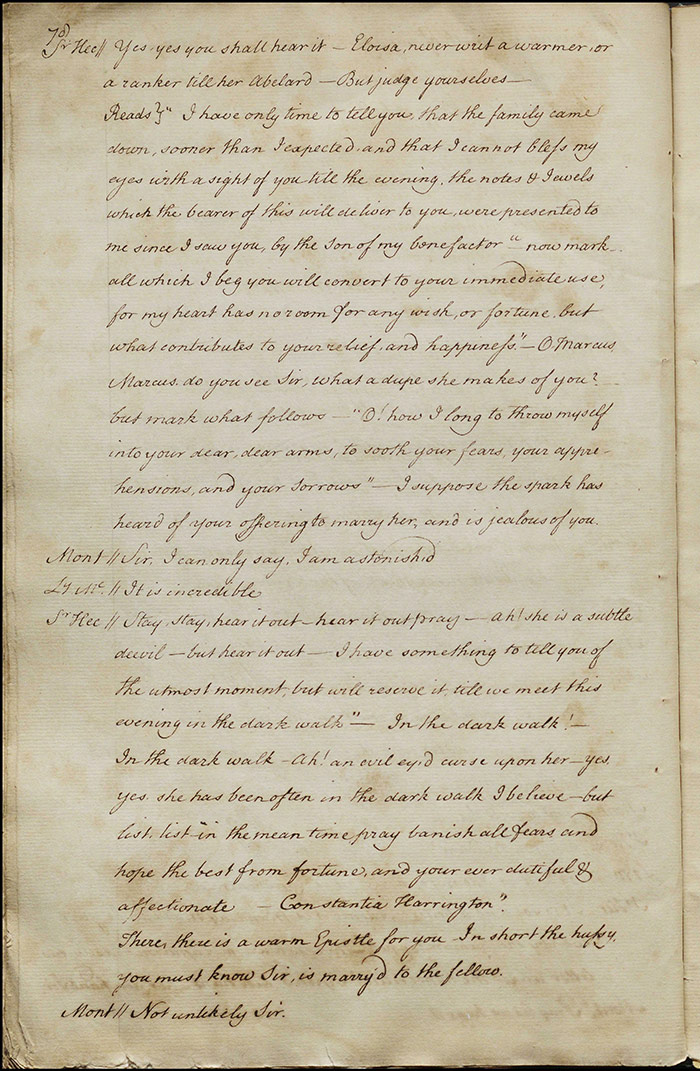

Hector MacCrafty, an ambitious and venal Scotsman living close to London, has plans for his son, Marcus Montgomery. He wants Marcus to marry Lady Rodolpha in order to advance the political and financial fortunes of the family as well as securing the interests of a Scottish cabal in Westminster. Marcus, however, is in love with Constantia, a young girl of mysterious origins. Equally importantly, he has been schooled by a virtuous tutor Sidney, who is also in love with Constantia, but hides his love from his master.

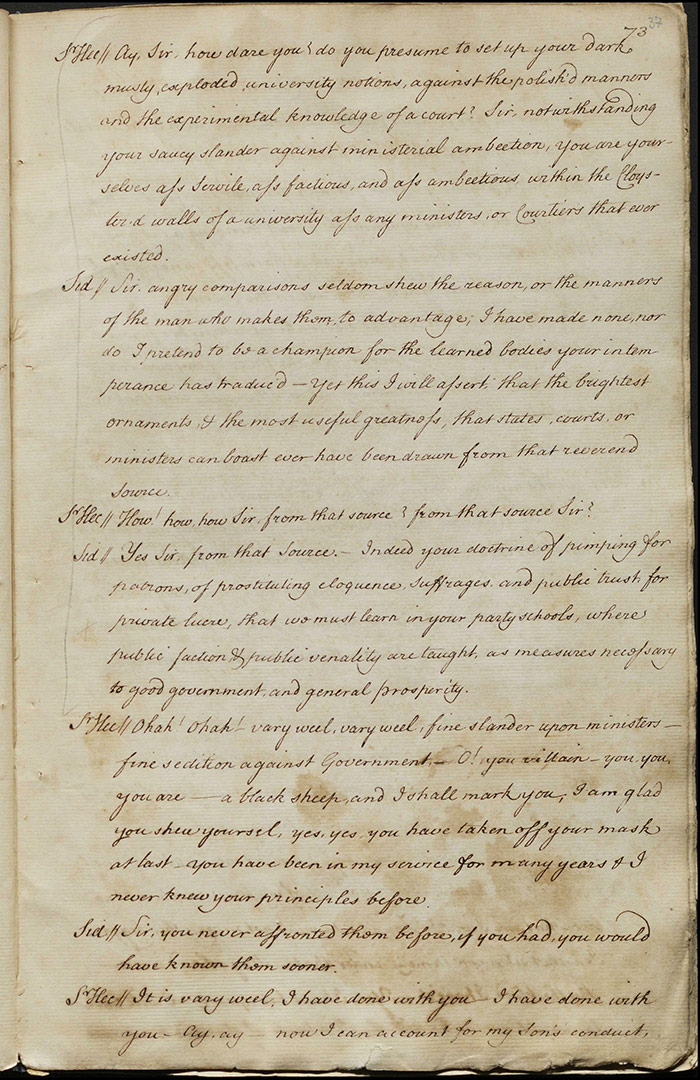

Despite enormous pressure from MacCrafty, Montgomery resists his instructions much to MacCrafty’s rage. The pair have substantial and heated exchanges on the function and nature of contemporary political life. Thankfully, Constantia is in love with Marcus too and, despite the malice of the servant Betty, the two are united at the close of the play. Constantia also discovers her wealthy father, returned from India. Lady Rodolpha marries Montgomery’s brother. MacCrafty disinherits his conspiring wife and his son but Montgomery’s virtue is unblemished at the close the play.

Performance, publication, and reception

The play was performed on 10 May 1781 at Covent Garden theatre with an epilogue supplied by Frederick Pilon and was accompanied by Arthur Murphy’s The Upholsterer (1758). It had 4 subsequent performances that season on 15, 17, 21, and 28 May. The comedy was performed regularly during the 1780s but fell out of favour in the 1790s. Macklin played the part of Pertinax MacSycophant (as Hector MacCrafty was renamed in the licensed version). A version of the play titled The Trueborn Scotchman (now lost)was performed earlier at Smock Alley theatre in Dublin in 1764. The Licensing Act did not extend to Ireland.

An account of the initial London performances is offered by Macklin himself:

The low and vulgar Scotch, the low and envious critics, the Methodists, and some ignorant, attacked the first night […] The second night, about six vulgar Scots in the gallery attacked it, a battle ensued, the English, Irish, and Welch, were full ready for such things as you may imagine, they were beat, turned out; - a Scotchman who gave the first blow, was, for the assault, sent to the round house, - bailed next morning before a justice (Cited in Kinservik, 1999)

The play garnered a lot of attention in the newspapers, unsurprising given that its political resonance was still felt to be powerful. The St. James’s Chronicle (10-12 May 1781) believed it to be a very uneven play: the language was at times ‘sublime’, at other times ‘indecent’. It draws attention to the vehemence of the attack on the Scots and described it as ‘one continued Tissue of the bitterest Sarcasms on modern Politicians’. However, should Macklin be prepared to retouch and compress the comedy, ‘it would be by much the best Play that has been produced on the English Theatres the last twenty Years’. The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (11 May 1781) witnessed a ‘very mixed reception, several passages being received with general and reiterated plaudits, and others with severe marks of disapprobation’. The writer objected to the great length of the piece and the many repetitions that marred it. He also urged the removal of the play’s many ‘gross expressions and disgusting ideas’. On the other hand, the Public Advertiser (11 May 1781) felt the piece was ‘tolerably well received’ despite also expressing reservations about some aspects of its language and sentiments. The critic was disappointed that MacSycophant remained unpunished at the end of the play but drew positive attention to the author’s politics: ‘Mr. Macklin, throughout the whole, breathes the Spirit of Patriotism, and in several Passages proves he is tolerably versed in the Politics of this Country’. The London Courant and Westminster Chronicle (12 May 1781) also offered a mixed take on the play:

The play has many beauties and many faults. The fable, though well imagined, is wretchedly conducted. For an ostentatious display of character is made to precede the bustle and business of the piece.

The characters are like the paintings of Fuzel’s, in the Royal Academy; wonderfully conceived; but execrably drawn; and the language and sentiments are sometimes imitations of the best political satires of Junius; sometimes too low and groveling for the colloquies of an alehouse.

In summary, we can observe that the play received many lengthy and thoughtful reviews; these reviews were mixed; and, the political sensibilities of the newspaper had a considerable bearing on the play’s reception.

Commentary

The case of The Man of the World is unique in the eighteenth century as the only play to be twice refused a performance license by the Examiner of Plays. There are three manuscript versions in Larpent and additional material is located in the Folger Library. As such it has attracted considerable commentary: a full consideration of the differences and revisions of the three manuscript versions and the published version is beyond the scope of this resource. The reader is directed to Macmillan and Kinservik who offer the most detailed and thoughtful analysis of the play’s multiple manuscript versions.

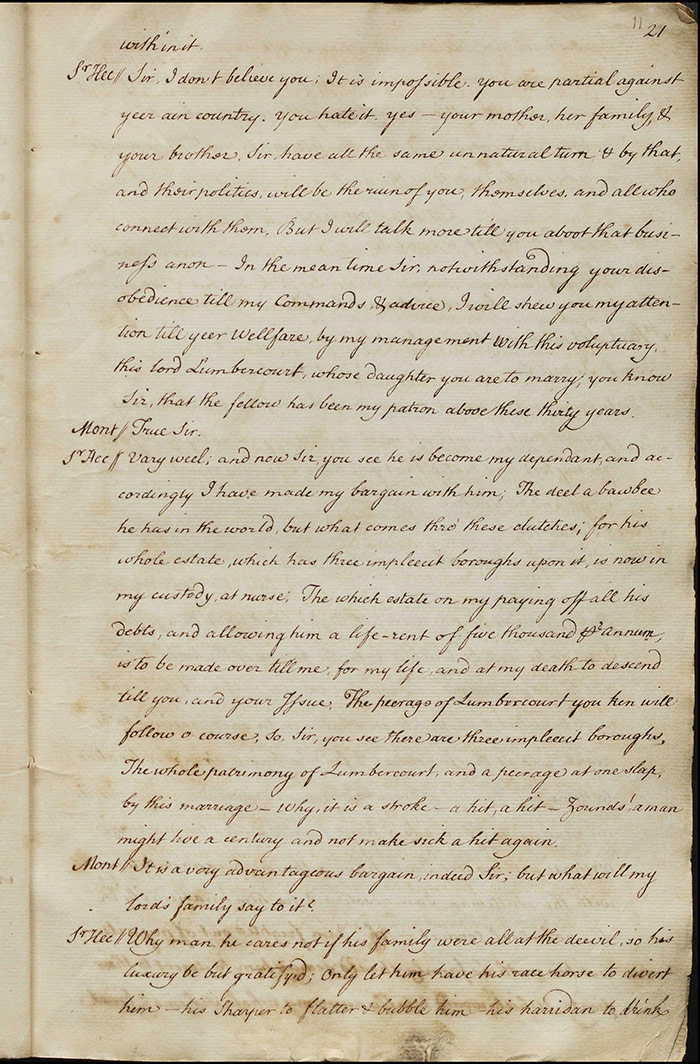

This manuscript of The Man of the World was submitted by Samuel Foote, manager of the Haymarket, on 2 August 1770 but was thought ‘Thought unfit to be licens’d’ as noted on the manuscript by Edward Capell, Deputy Examiner. It was subsequently resubmitted to the Examiner on 4 December 1779, not long after the appointment of John Larpent to the office, by Thomas Harris, manager of Covent Garden. Despite having an eloquent note appended to the manuscript (LA 500) by Macklin himself, it was again denied a license. In the note, Macklin argued:

The Author’s chief End in writing the Man of the World was to ridicule & by that means to explode the reciprocal national Prejudices that equally soured & disgraced the Minds both of English and Scotch Men. Mr. Macklin flattered himself that the Exposing of an absurd Scotch Father’s Obstinacy in national Prejudices, wou’d be such a Lesson to such kind of men as to make them less frequent in the Indulgence of those offensive, unsocial Humours.

The play was submitted a third time in 1781 (LA 558), again by Harris, and it was finally granted a license.

The original manuscript is relatively unblemished by comparison to other plays, particularly given the considerably colourful history of the play. There are numerous emendations in the margin in pencil, probably made, as MacMillan notes, by John Payne Collier. Collier, who once possessed the Larpent Collection, was sufficiently interested to mark numerous passages with penciled brackets in the margin and the occasional written comment such as ‘omitted in 4o’or ‘altered’. Both the later manuscripts are in quarto but, given that there are some corresponding comments by Collier on the 1781 copy, it is probable that he is comparing to this version (LA 558). We should acknowledge at this point that changes may have been made and noted by Collier for dramaturgical reasons rather than insisted upon by the Examiner’s office. There are, however, also a very few passages marked with an X in pencil in the margin and the strong suspicion must be that they are made by Deputy Examiner Capell.

Before offering a selection of the passages marked for alteration or omission, some sense of the political environment and Macklin’s own politics should be delineated. Macklin was a determined supporter of John Wilkes, author of the notorious North Briton, and had also attracted much notice for the anti-Scottish sentiment of his earlier play Love à la Mode (1759). There was much suspicion of Scottish political and cultural influence in London and there was a specific Irish element to this in the wake of the Ossian controversy. Macklin’s play then was an explicit critique of Scottish political power and corruption in London and this was a topic of such political sensitivity that it was a remarkably ambitious piece to submit for licensing.

Most of the passages that attracted attention emerge from the exchanges between the corrupt Hector MacCrafty and his virtuous son, Marcus. An instance which Collier marked ‘much altered here’ is found when Sir Hector mocks his son’s liberal education on (f.17v). Before they have their second significant encounter in Act 4, MacCrafty insists that ‘must cure him of his poleetical candour, patriotism, ministerial independency and aw such nonsense’ which is marked ‘omitted’ by Collier (f.31r). The pair have a frank exchange of views which continues through (f.31v-32r) where Montgomery’s condemnation of the ‘venal ambition of the times’ meant that significant alteration and adjustment was required.

There are also references to the corrupt lawyers (f.28r), corrupt ministers (f.36v)-(37r), and ecclesiastical corruption (f.37v). The latter two are also marked with a small ‘X’ in the margin which may be Capell. The only other penciled X appears in an early speech from Sir Hector on (f.10v) which closes:

Sir, Scotchmen, Scotchmen Sir, wherever they meet throughout the globe should unite & stick together; as it were in a political phalanx – For Sir, the whole world hates us, and therefore we should love one another.

The explicit claim that the Scottish were organized in a cabal and the use of the military image may help explain why there are so little interventions by Capell on the manuscript. The language may have been deemed so outrageous and indicative of the play’s tendency as a whole that there was no need for further mark-up: the play was going to be rejected from that point onwards and Capell may have felt further commentary superfluous.

Further reading

W.W. Appleton, Charles Macklin: an actor’s life (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961).

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), passim.

Matthew J. Kinservik, ‘New Light on the Censorship of Macklin’s The Man of the World’, Huntington Library Quarterly 61:1/2 (1999), 43-66.

_____ Disciplining Satire: The Censorship of Satiric Comedy on the Eighteenth-Century London Stage (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2002), esp. 184-194.

Dougald MacMillan, ‘The Censorship in the Case of Macklin’s The Man of the World’, The Huntington Library Bulletin, 10 (1936), 79-101.

David O’Shaughnessy, ‘bit, by some mad whig’: Charles Macklin and the theatre of Irish Enlightenment’, Huntington Library Quarterly 80:4 (2017).

Robert Shaughnessy, ‘Macklin , Charles (1699?–1797)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2015 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/17622, accessed 20 April 2017]