The Platonic Wife (1765) LA 244

Author

Elizabeth Griffith (1727-1793)

Griffith was the daughter of Thomas Griffith, actor-manager of Smock Alley theatre in Dublin. She made her debut at that theatre in 1743. She married a farmer from Kilkenny, Richard Griffith, in 1751 in a ceremony that had to be kept secret from Richard’s father who wanted his son to marry money. The couple’s impecunious situation led Elizabeth to pursue a literary career and she wrote her first play, a tragedy, Theodorick, King of Denmark, in 1752. The play was not staged but it did attract a subscription list of close to 500 names on publication. The following year she moved to London and performed minor roles at Covent Garden theatre.

She stopped acting after becoming pregnant with a second child and Richard’s business interests collapsed around the same time. Forced into desperate action, the Griffiths published their courtship correspondence as A Series of Genuine Letters between Henry and Frances in 1757. It went through a number of editions and there were follow-up publications. After a period in Ireland, the Griffiths returned to London in 1764 where Elizabeth pursued a career as a playwright. After the negative reaction to The Platonic Wife (see below), she produced some successful domestic comedies such as The Double Mistake (1766) and The School for Rakes (1769) with some assistance from David Garrick.

Griffith was also a novelist and she wrote three epistolary fictions that were developed from her courtship letters: The Delicate Distress (1769), The History of Lady Barton (1771), and The Story of Lady Juliana Harley (1776). They make explicit her belief that novels could be tools of moral instruction. She also wrote dramatic criticism, essays of instruction for women, and a noteworthy collection of short stories, Novellettes, selected for the use of young ladies and gentlemen, written by Dr Goldsmith, Mrs Griffith (1780). She also completed a large amount of translation work during her career.

All her hard work was the means by which her son, Richard Griffith, was able to join the East India Company where he was enormously successful. He brought his parents back to Ireland in 1782 and they both died peacefully on his Kildare estate.

Plot

The advertisement to the piece attributes the play’s plot to L’Hereux Divorce (the happy divorce), one of Marmontel’s Contes Moraux. There is also a debt to Griffith’s earlier Henry and Frances in the depiction of an assertive and educated female character. The play is essentially a meditation on modern marriage and the mutual expectations of husband and wife. While there is considerable weight put on female propriety and obedience, scrutiny is also applied to the behaviour of men, both within and without the context of marriage.

The play opens with Lord and Lady Frankland separated. Lord Frankland is dismayed at his wife’s demand for overly romantic declarations of love which she has gleaned from her reading of novels. For her part, Lady Frankland is irked by his indifference towards her. Both of them remain in love and regret what has happened. However, Clarinda, a former lover of Frankland’s, and Lady Fanshaw, her spiteful friend, are determined to exploit this rift and tempt Lady Frankland into infidelity. The conspirators goad Sir Harry Wilmot (a rake) and Sir William Belville (an honourable man, suffering from unrequited love) into attempting to win her favours but she is virtue personified and rebuffs them. Finally, they are manipulated into a duel over her.

The subplot revolves around Charles Frankland, the younger brother and heir, and his passion for Emilia, a wealthy heiress and friend of Lady Frankland. He is also determined to bring Lady Frankland down to prevent the marriage producing any issue and depriving him of his brother’s fortune.

Desperate, Charles Frankland plans the rape and possible murder of Emilia to sate his passion, aided by Fontange, a French maid. Patrick, the loyal Irish manservant of Sir William, exposes the plot to Lord Frankland. Lord and Lady Frankland are reunited at the close of the play, both having learnt from their experience and promising to value each other more in the future. Sir William and Emilia also declare their love.

Performance, publication, and reception

The five-act comedy was first performed on 24 January 1765 at Drury Lane theatre. There were five subsequent performances on 25, 26, 28, 29, and 31 January.

Reviews were generally negative and paid particular attention to Griffith’s gender. The Monthly Review (1765) opined:

The town was so candid and indulgent as to bear with the imperfections they could not but discern, in this unfortunate production of a female pen, during a run of six nights. We will not show ourselves less courteous to the ingenious lady, by too rigid an examination of a performance she may wish to forget (XXXII, 155).

The London Chronicle or Universal Evening Post (24-26 January 1765) sniffily summed up: ‘In a word, want of knowledge of the business of the stage, and of conduct in the piece, seem to be the greatest faults of the female author, who has nevertheless shewn herself a great mistress of sensibility and of agreeable dialogue’. The Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (26 January 1765) closes its review with the same sentiments (and words, in fact) but also comments more specifically:

This piece, though it abounds with many just thoughts and fine moral sentiments, is yet very deficient in the business of the stage; the audience are kept too long in suspense, and the plot opens greatly too slow. The unities of time, place, and action are all broken.

Praise was directed at Catherine Clive, and her engaging delivery of the epilogue was given much of the credit for the play being announced for the following night. Both the prologue and the epilogue were published in many of the newspapers.

The play was published in late January 1765 by W. Johnston and T. Davies. An edition was also published in Dublin for Peter Wilson et al.

Commentary

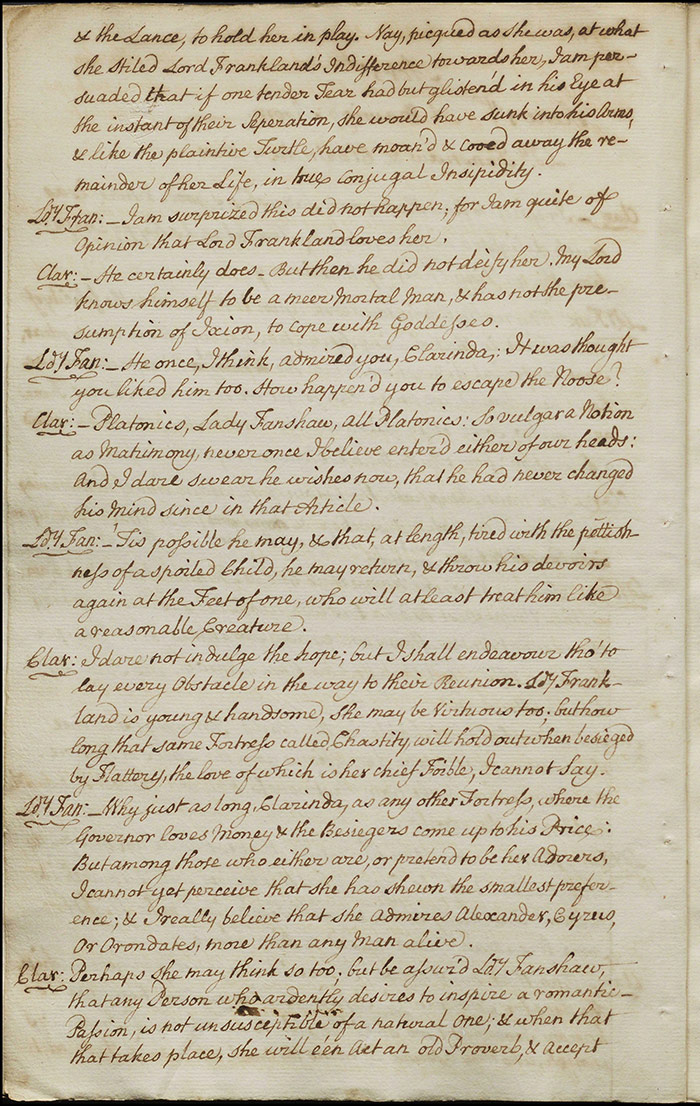

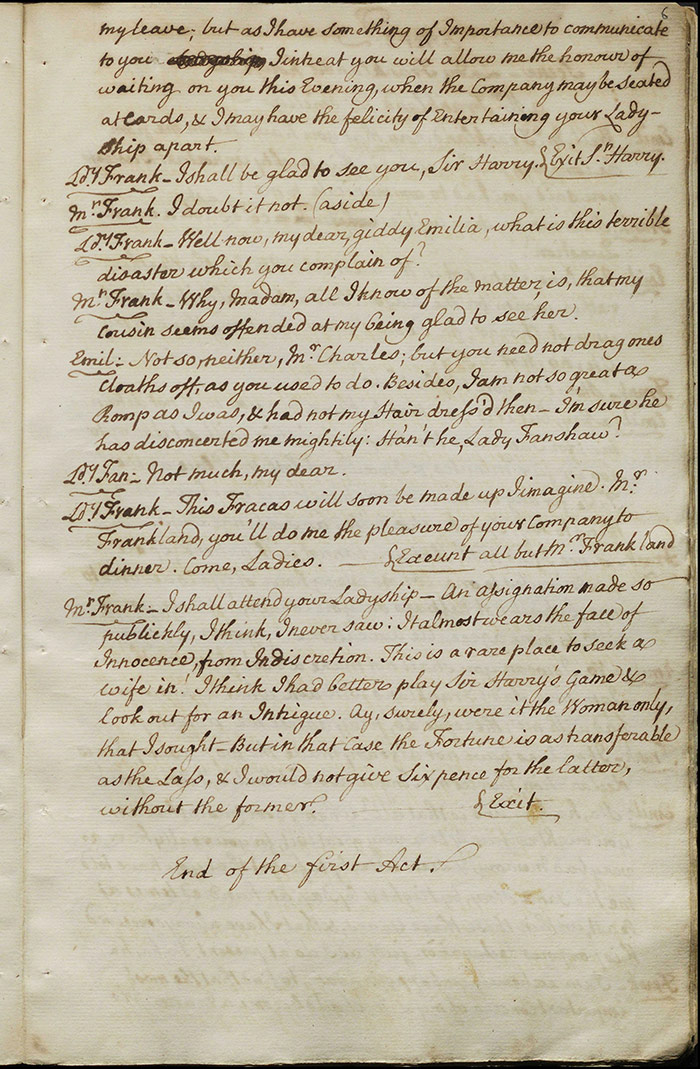

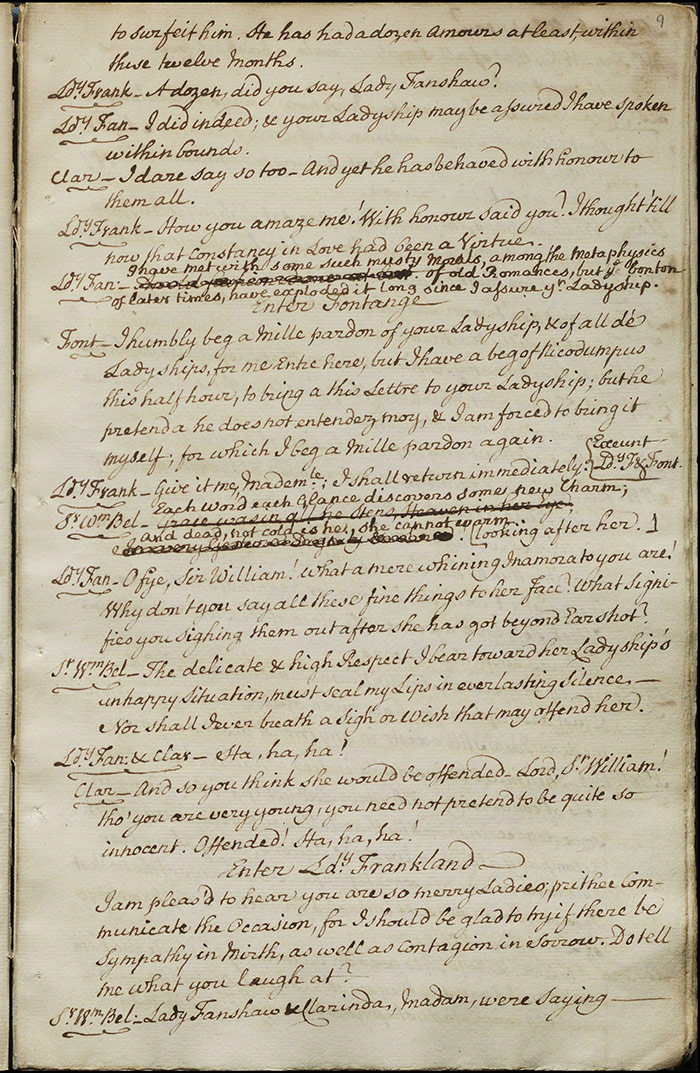

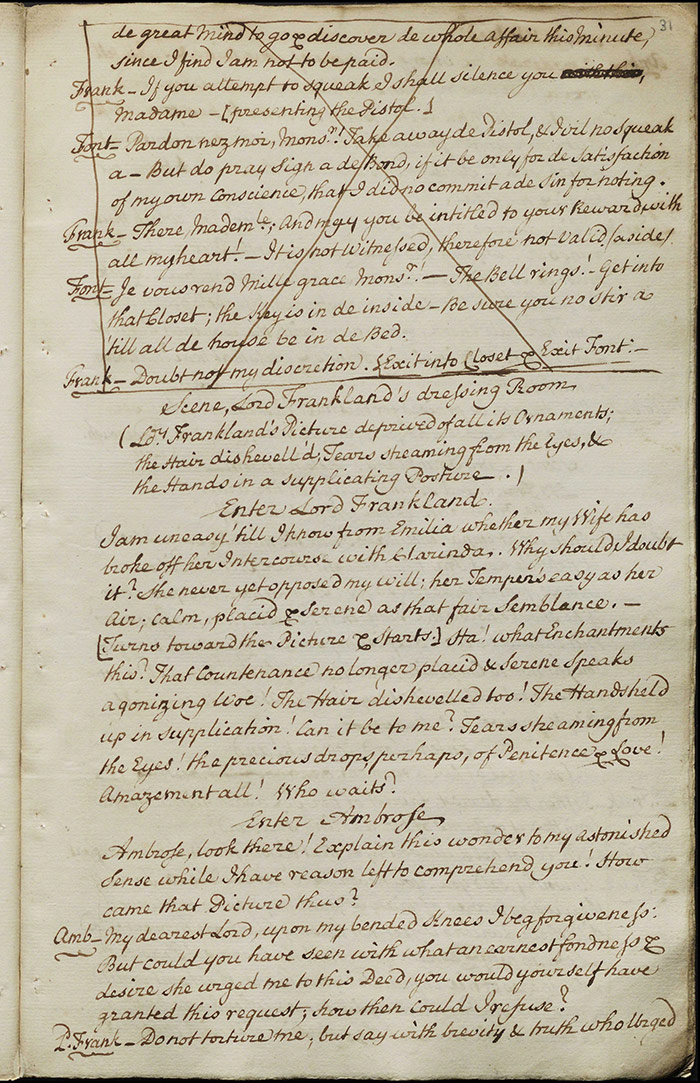

The manuscript shows a number of emendations and excisions made with pen. There are also replacement passages pasted in above earlier text as well as a number of deletions made by the copyist due to error. As usual there is difficulty in determining the author of those interventions related to censorship: some may be made by the Examiner, others by the author manager. However, the case of this particular play is striking as we have a public statement from Griffith, spurred into action by the hostile audience reaction on the play’s opening night, indicating that she made cuts for subsequent performances. The play then has both a pre-performance and a post-performance layer of censorship applied to it.

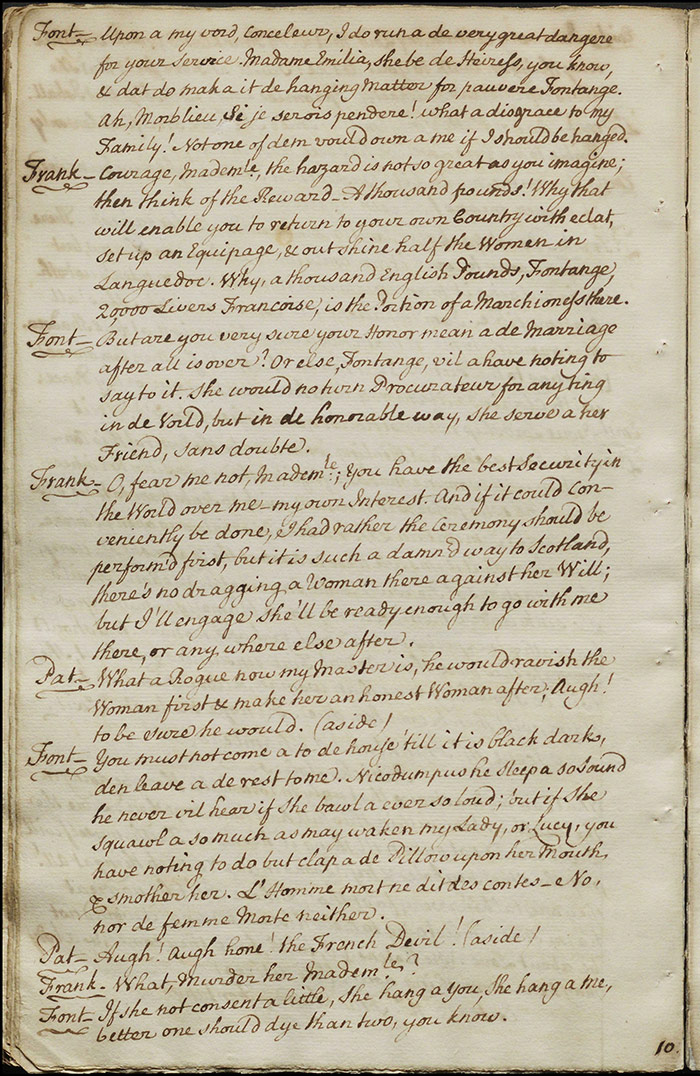

In terms of the pre-performance censorship, we have the evidence of the manuscript. There are not many of these excisions and they are not out of the ordinary. Religious expression is struck out on (f.3v) when Nicodemus, a servant character, says ‘Ise just as soon shake hands with the Devil’s Cloven Foot’ and the phrase ‘hug an hedgehog’ is interlineated by way of replacement.

When Emilia asks Lady Frankland to step into the next room to hear the ‘last new Song of Brent’s that your Ladyship seem’d fond of’ (f.10v), it seems an innocuous reference which suggests that references to real people on stage was always to be frowned upon, even when positive. However, this case is slightly more complicated as Charlotte Brent (1734-1802) was the star soprano singer for the rival Covent Garden theatre who had begun her career in Smock Alley in 1755 when she may have overlapped with Griffith. It would appear that a manager, anxious not to promote his main competition, removed a generous act of professional female solidarity.

The desperate closing lines of the second act from Frankland are also struck out with pen: ‘To Men’ o’erwhelm’d with Vice, or Misery’s force / A Pistol always is a sure resource’ (f.11r). It is presumably the suggestion of suicidal ideation that is at issue here although the association of class and rapacious sexuality and extreme debt may also have contributed to the removal of the lines.

The play was met by some hostility on its opening night. According to Griffith, the criticism was driven as much by her gender as it was the quality of the piece. She placed the following article in the Public Advertiser (28 January 1765):

The unkind Treatment, if she may be allowed the Expression, which this Comedy met with on Thursday Night, has given her the highest Concern, not for the Attack on her Character as a Writer, but as a Woman, the Imputation of Indelicacy being certainly the most cruel, and she flatters herself, the most unjust that could possibly have been urged against her. She is far from presuming to dispute or contend with the Public, she receives their Correction with Submission, and hopes she may be thought to have shewn proper Attention to it, by striking out every Passage in the Representation, which they seemed to think exceptionable. Her only Motive for introducing low Characters into the Piece, which was first written without them, was from an apprehension that the Performance might be deemed rather too grave for a general Audience, but she hopes that the Change brought on that Account, will be obviated to those who are kind enough to read the Comedy with that Candour and Indulgence which the first Attempt of a Female Writer, wholly in experienced in Theatrical Composition should claim.

We might first observe that while Griffith’s implicit claim that she is getting particular critical attention as a female writer is borne out by the newspaper and periodical reviews cited above, it is also the case that Oliver Goldsmith received equally hostile audience reaction some years later in 1768 for the depiction of low characters mixing on stage with more genteel folk in The Good Natur’d Man. Nonetheless, the primary question here is how to determine what kind of changes were made. The only way this is possible is to compare the Larpent manuscript with the published version. While it is often the case that the author uses the published version as an opportunity to restore cuts made by the Examiner (sometimes including an indignant protestation of innocence), a comparison of the two versions of The Platonic Wife does not suggest that this is the case here.

A full comparison is not possible here but there certainly are examples where changes were not requested by the Examiner or the manager but were nonetheless made for the published version. In Act 4, Charles and Fontange conspire to assault Emilia. She is worried that he will not marry Emilia after he rapes her and the discussion is quite explicit. Frankland breezily states ‘if it could conveniently be done, I had rather the Ceremony should be perform’d first, but it is such a damn’d way to Scotland, there’s no dragging a Woman there against her Will; but I’ll engage she’ll be ready enough to go with me there, or any where else after’. Fontange, anxious about being hanged, demands that if Emilia makes noise that he should ‘ clap a de Pillow upon her Mouth, and smother her’ (f.21v). Frankland thinks that the violence may be unnecessary and that Emilia may comply but Fontange warns that Emilia ‘would die rather than let a man see her tye her Jartiere’ (f.22r). All of these references are unmarked in the manuscript but are removed in the published version which is a much briefer and more demure exchange (p. 62). Fontange’s insistence on murder is shocking indeed and that it is a French servant urging an English member of the gentility exacerbates it. Erotic images of tying garters and Frankland’s casual reference to raping Emilia into submission may also have provoked an audience reaction. In Act 5, Sir Williams’ indignant reference to the attempted ‘Rape & Murder of [Emilia]’ (f.32v) is also tempered down to ‘the absolute ruin of [Emilia]’ (p. 92).

In the play’s advertisement, Griffith admits that she had ‘perhaps, too adventurously hazarded [the public’s] criticism and censure’; the published version indicates that she took decisive action to redress the situation.

Further reading

Elizabeth Eger, ‘Griffith, Elizabeth (1727–1793)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/11596, accessed 10 April 2017]

Elizabeth Griffith, The Platonic Wife (London: W. Johnston and T. Davies, [1765])

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

Betty Rizzo, introduction, Eighteenth-century women playwrights, ed. D. Hughes (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2001), vol 4: Elizabeth Griffith.

_____, ‘“Depressa Resurgam”: Elizabeth Griffith's playwrighting career’, Curtain calls: British and American women and the theater, ed. M. A. Schofield and C. Macheski(Athens: Ohio University Press, 1991), 120–42

_____, ‘The Other Elizabeth Griffith’, in Teaching British Women Playwrights of the Restoration and the Eighteenth Century, ed. Bonnie Nelson and Catherine Burroughs (New York: MLA, 2010), 120-135.