Spanish Bonds; or, Wars in Wedlock (1823) LA 2361

Author

Anonymous.

Plot

[Act 1]

The two-act farce opens with a row between Donna Elvira and her husband Don Alvais. She has received a letter informing her that their daughter’s fiancé, Don Felix, due to arrive from Madrid that night, is already married. Don Alvais refuses to believe it and insists that nothing be said to Isabella until he has spoken to Don Felix. He is convinced that the letter, purporting to be from Don Felix’s wife, is ‘an absurd fabrication’ (f.4r). Donna Elvira is deeply perturbed and refers to Don Felix as a vampire. She shrugs off her husband’s objections and goes to show Isabella the letter despite his admonitions of marital obedience.

[Scene 2; f.6r]

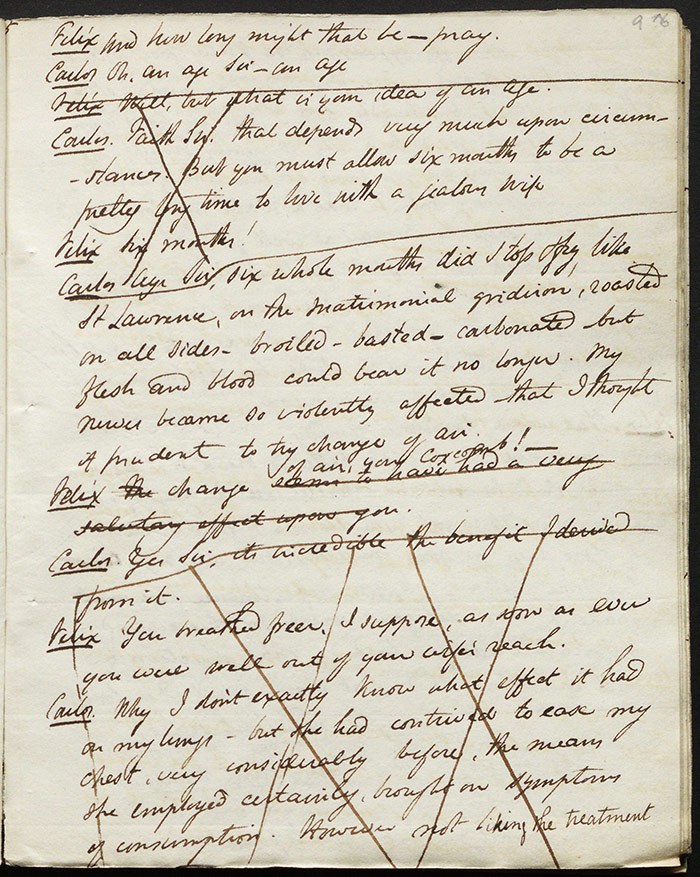

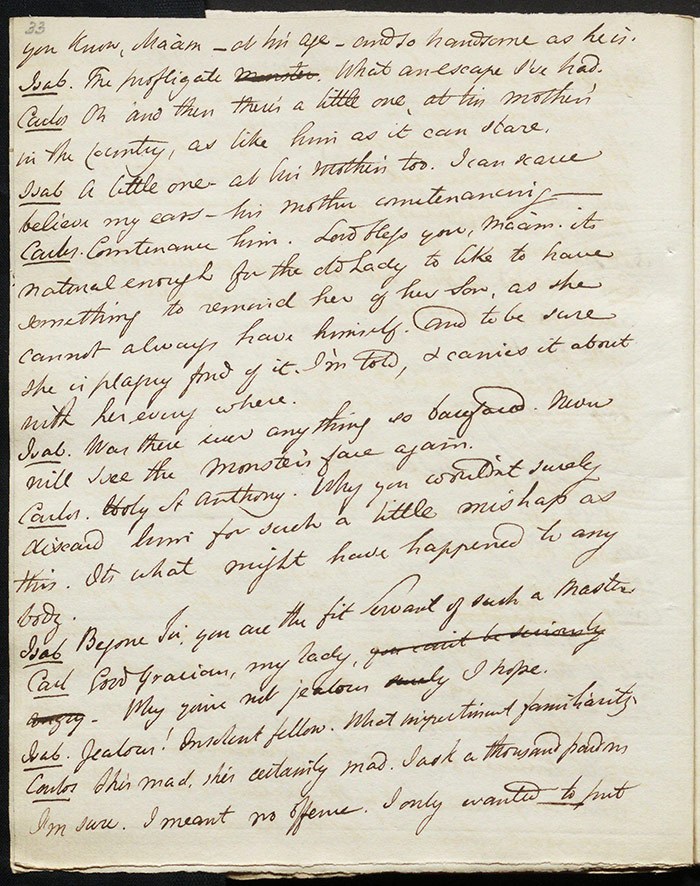

Don Felix is travelling through a wood with his servant Carlos. They are looking for a miniature portrait of Don Felix that he has dropped, one requested by Isabella. They discuss her as they search: Don Felix feels she is a little jealous; Carlos believes this means she should be avoided at all costs. Such is Carlos’s vehemence regarding the marital state, Don Felix probes him about his own marital experiences. Carlos reveals that he lived with his wife—also jealous—for only six months before absconding. Exeunt.

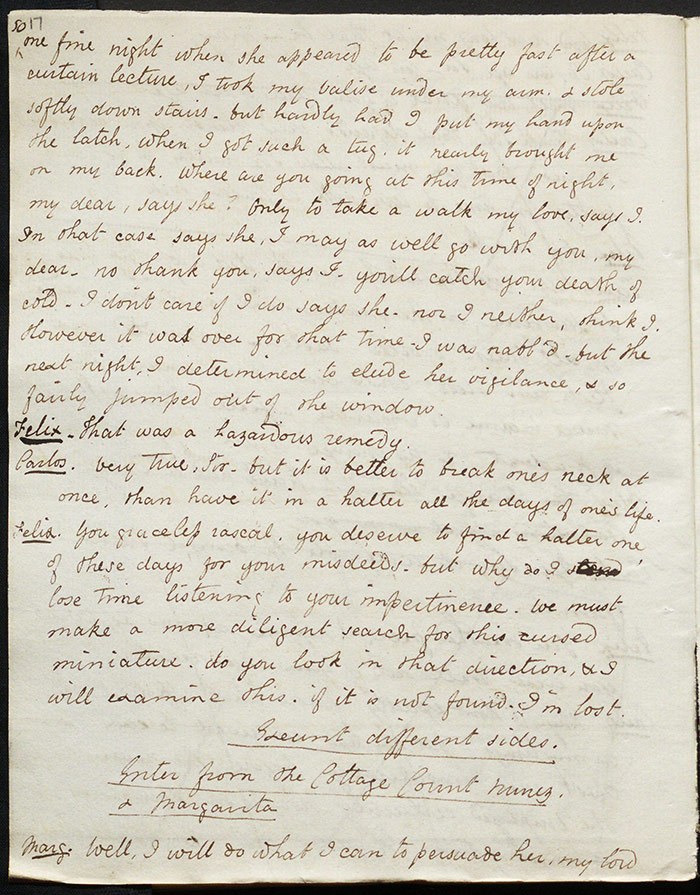

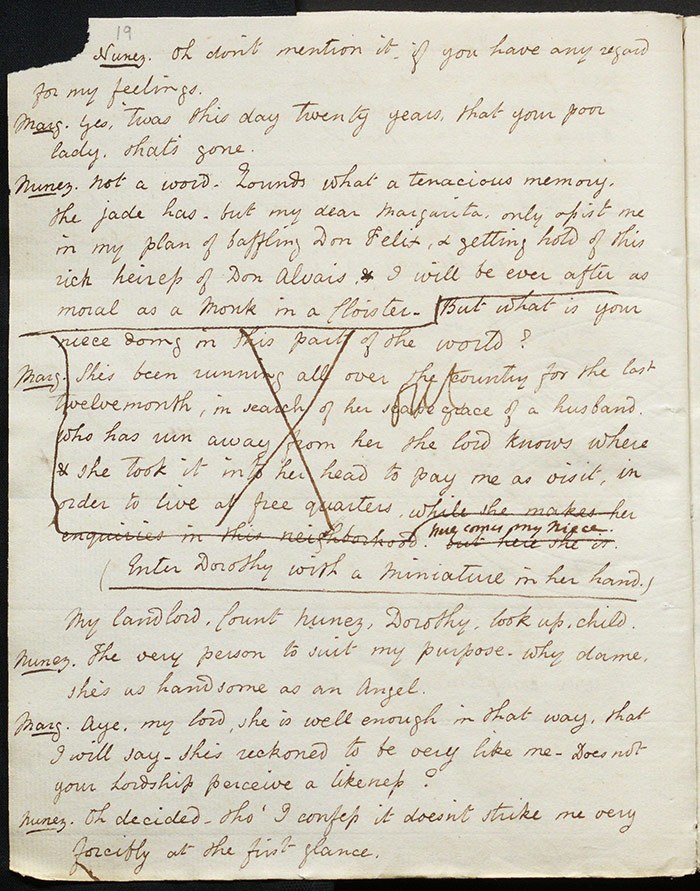

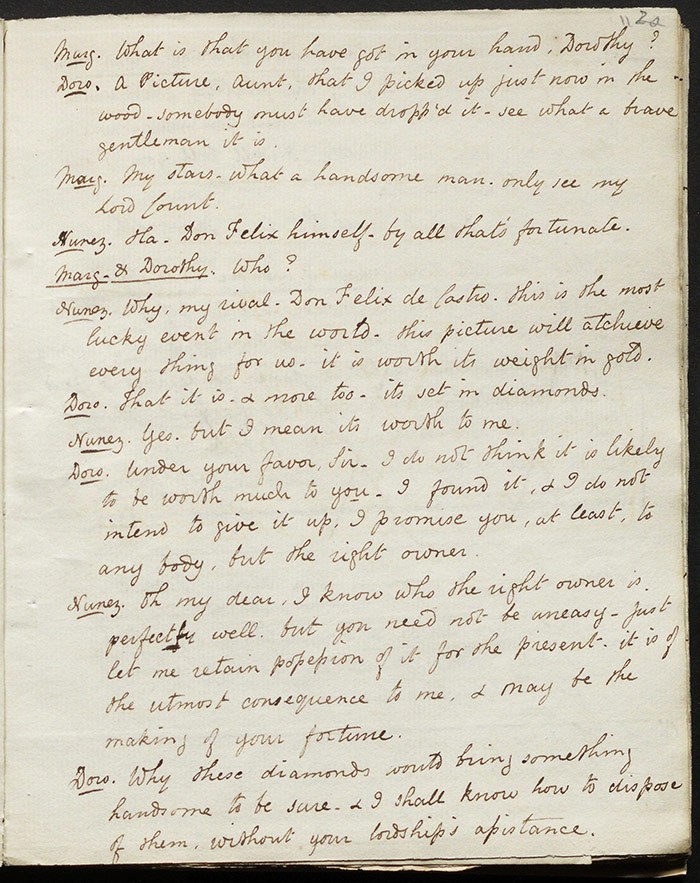

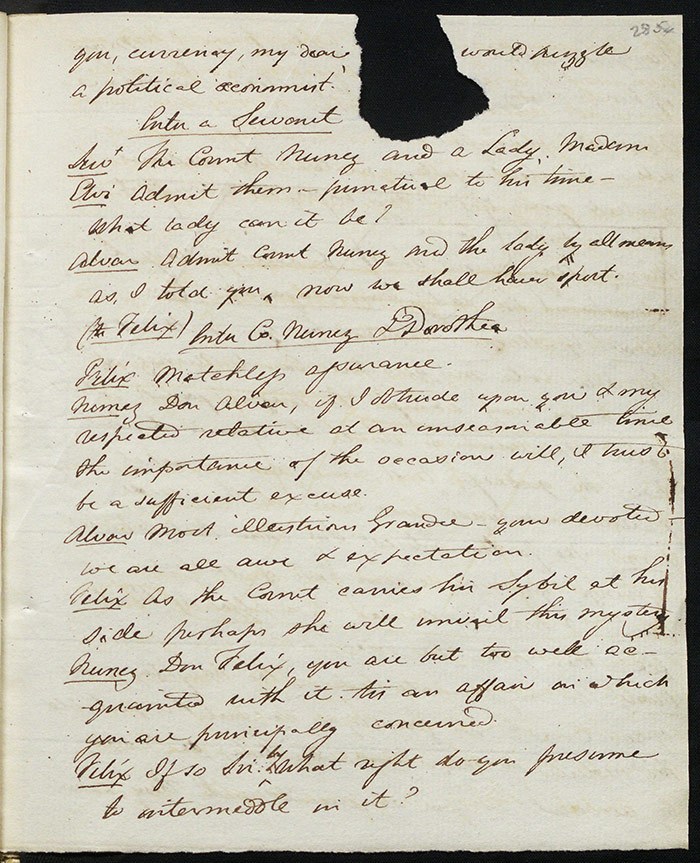

Count Nunez and Margarita enter from a cottage. Count Nunez is asking for her assistance to scupper the marriage between Don Felix and Isabella. He wants her niece, Dorothy, currently searching for her own husband, to go to Don Alvais and Donna Elvira and pretend to be already engaged to Don Felix, making him out to be a would-be bigamist. Dorothy enters. She has found the miniature and wants to return it to its rightful owner, being of an honest disposition. Count Nunez and Margarita exit so he can fill her in on the detail of the plan. Dorothy remains and is determined not to be exploited in aid of his nefarious plans.

[Scene 3; f.11v]

Isabella, at home and supported by her parents, is recovering from a fainting fit. Donna Elvira wants Isabella—who has just heard the news about Felix—to marry Count Nunez. This terrifies her and enrages Don Alvais; they proceed to list his many physical shortcomings. Don Alvais insists they hear Felix out, just before he arrives. When Felix enters he is lambasted by the two ladies to his bemusement. The act ends with him following them off, looking for an explanation for their hostility.

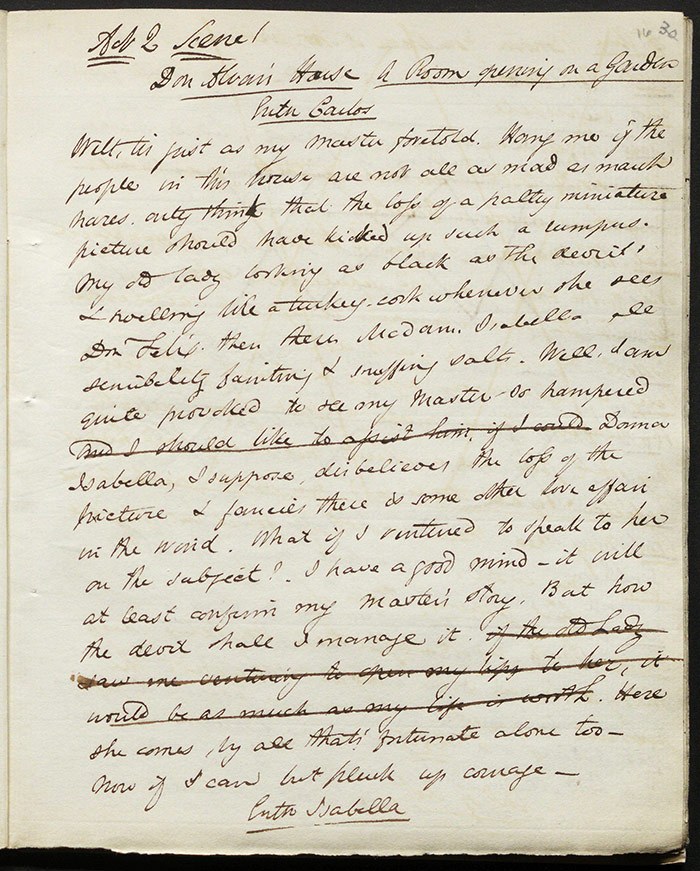

[Act 2, Scene 1; f.16r]

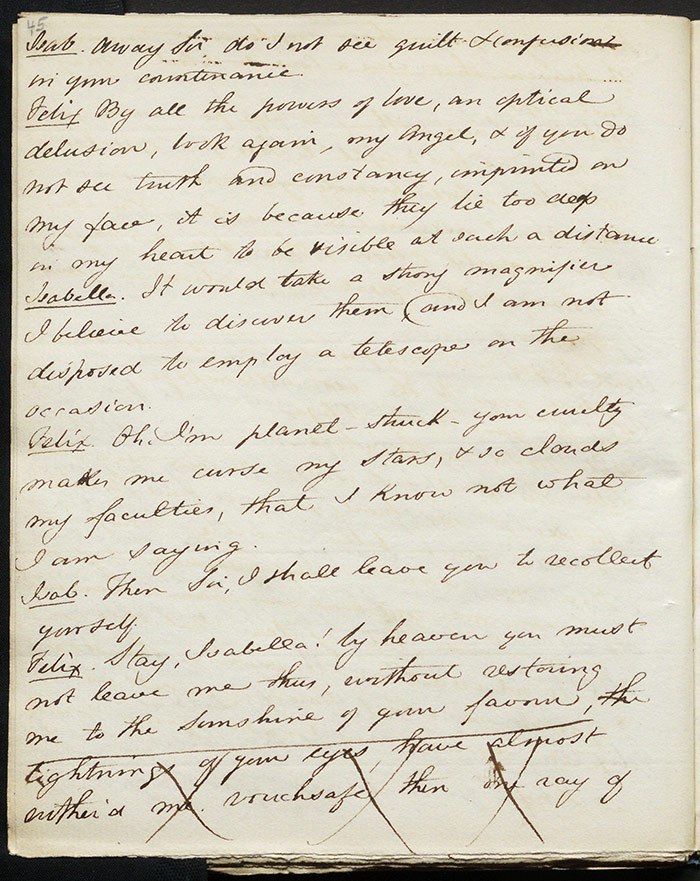

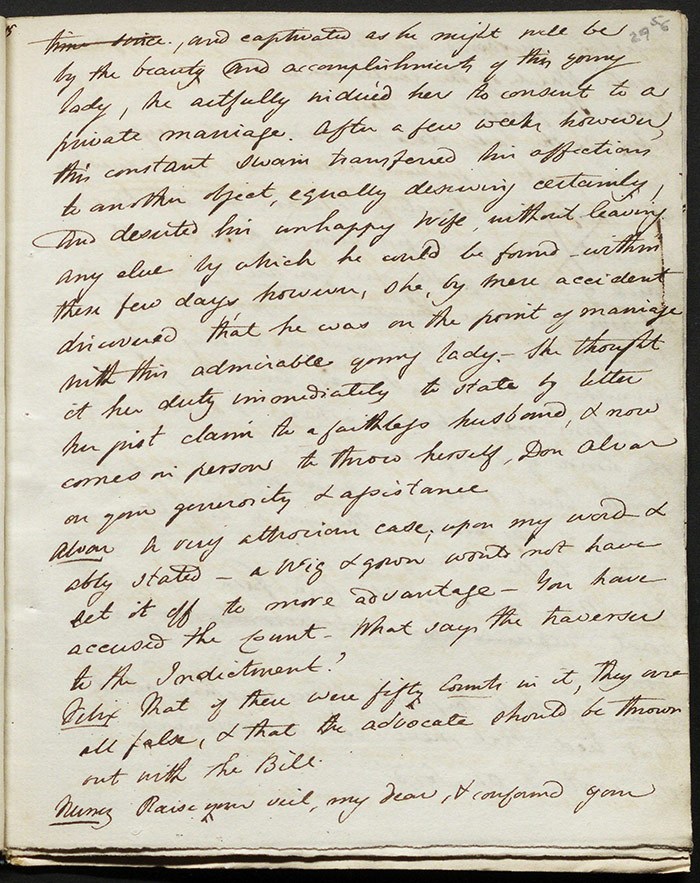

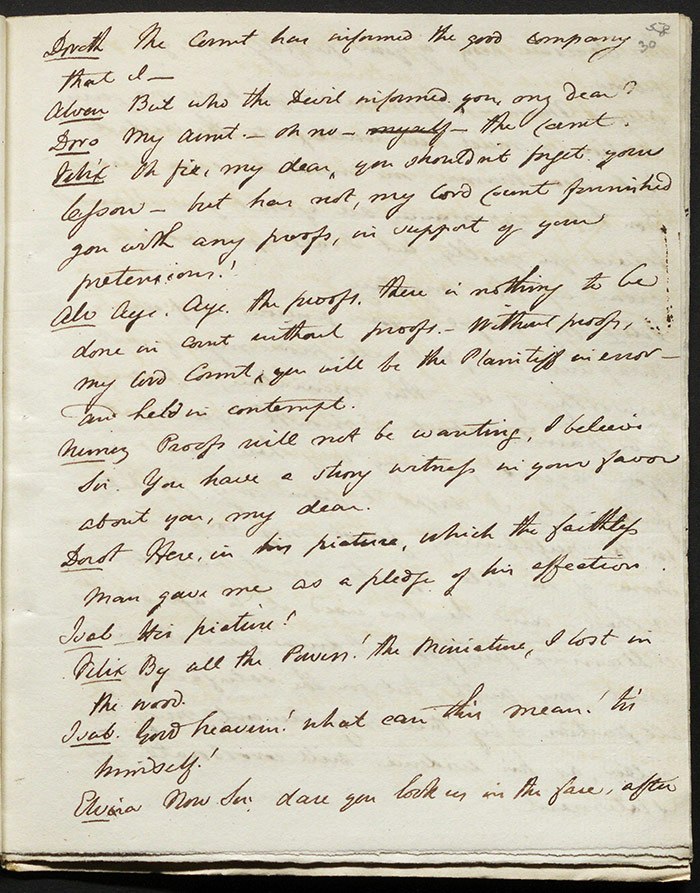

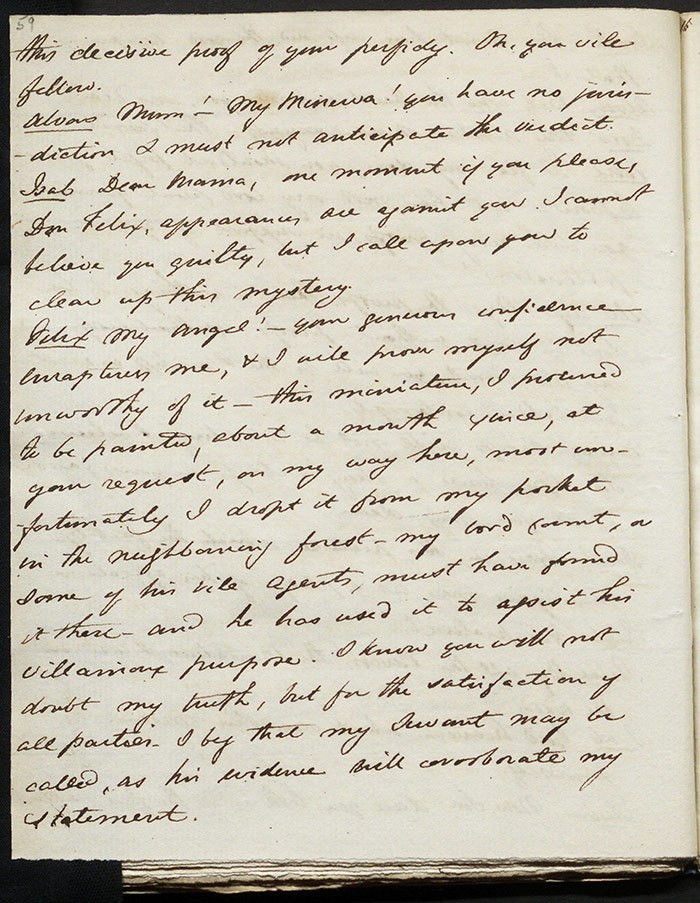

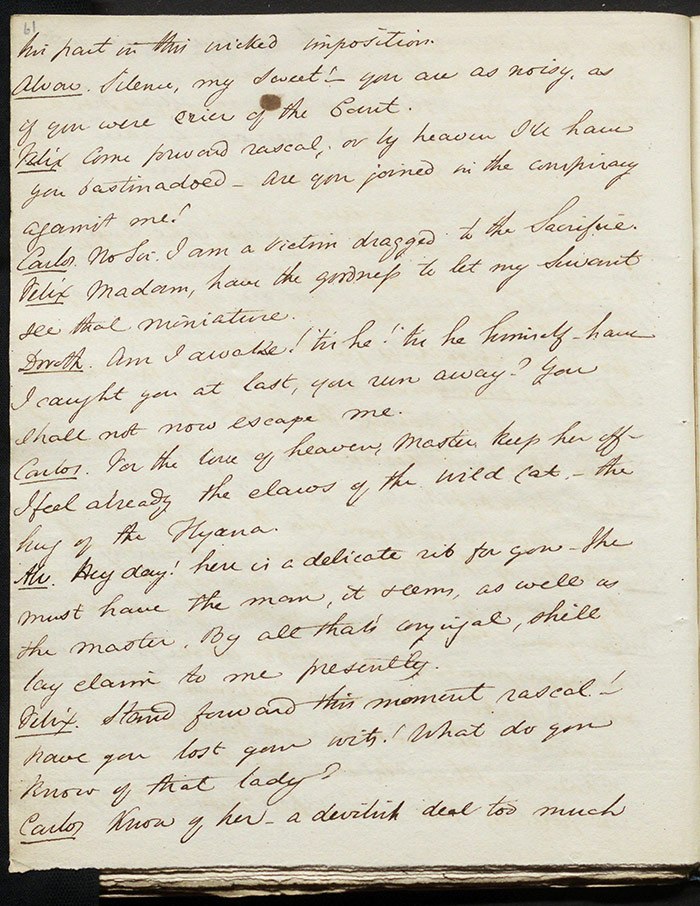

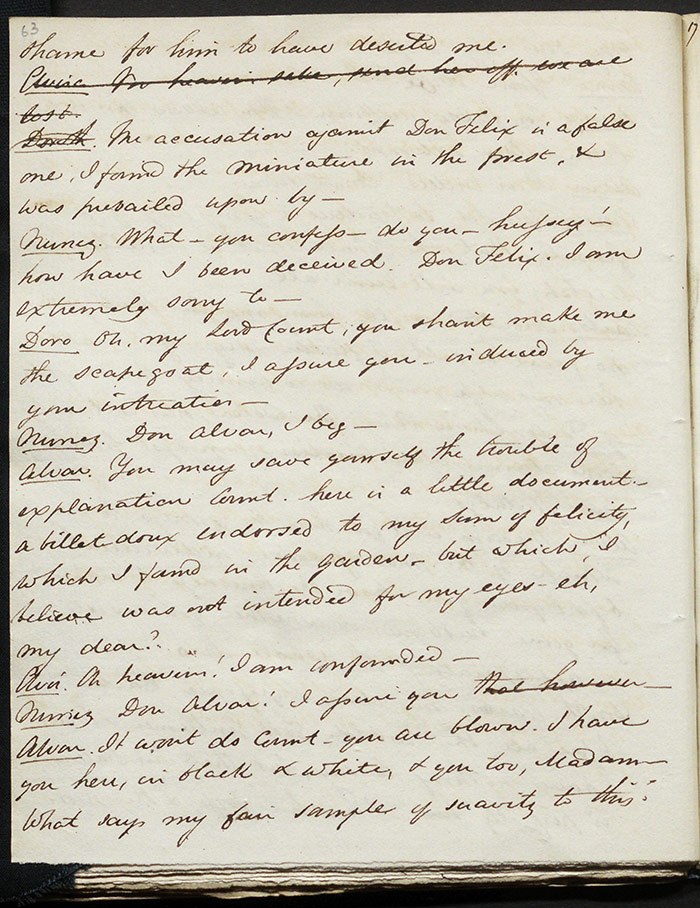

Carlos apologizes to Isabella, confessing that the story is all true and that they were hoping to keep it from her until after the marriage. Naturally, he is talking about the lost miniature; she, of course, believes he is talking about the alleged marriage of Don Felix. The conclusion of this comic exchange sees the truth come out. Isabella is much relieved but resolves to have some fun at Felix’s expense. They exit separately and Dons Alvais and Felix enter. They have also ironed out the misunderstanding. Don Felix spots Isabella and resolves to go to her. Don Alvais tells him not to let on to her they know the truth so they can also have some fun. Elvira enters and she is appalled that the wedding is going ahead, unaware that the accusation of bigamy has been disproved. She spots Isabella and Felix and tries to intervene but Don Alvais restrains her. Isabella and Don Felix resolve their pretended differences but then Elvira breaks free and disrupts the scene. She and Don Alvais row. The arrival of Count Nunez and a lady is announced. They make their accusations and Dorothy produces the miniature as evidence. Isabella wavers and Felix calls in Carlos to corroborate his story. He spies Dorothy, his deserted wife, and his ensuing uneasiness makes him a suspicious witness to Elvira. Carlos then lays claim to Dorothy and the ensuing fracas sees Count Nunez leave under threat of a ducking. The remaining characters are reconciled and the play ends.

Performance, publication and reception

The anonymous farce was staged on 3 August 1823 at the Haymarket Theatre. It was not published. This was its only performance and it was not well received. One can speculate that the play was so seriously marred by the stripping out of key passages which might have amused a contemporary audience that failure was inevitable. Excerpts from some reviews are offered below.

A new farce called “Spanish Bonds, or Wars in Wedlock”, was presented for the first time on Saturday evening, and a more paltry and wretched production could not have disgraced the boards of a patent theatre. – It were unnecessary, and equally impossible on our part, to submit to our readers any thing like an outline of the business; for, exclusive of the continued and excessive disapprobation manifested in the first and during the whole of the second act; we could not discover the least point, situation or humour, that could possibly be maintained. LISTON, as Don Alva, the father of Isabella (Mrs. CHATTERLEY) and husband to Donna Elvira, (Mrs. JONES,) did as much as his talent would admit of; but the torrent was too powerful to be conquered, and the curtain fell amidst the vociferations of “shame! off! off! &c. LISTON came forward at the conclusion, but the purport of his address was wholly inaudible. – The house was excessively crowded.

The Mirror of the Stage; or, New Dramatic Censor Vol. III, No. I

(4 August 1823), 9

On the 2d of July, a farce in two acts, called “Spanish Bonds, or Wars in Wedlock,” was consigned to “the tomb of the Capulets.” I had ventured to offer my opinion, that unless the author, who was perfectly incognito, could be prevailed on to make some material alterations in the piece, which I pointed out, - it could not be long-lived; but my advice was treated as obtrusive, and totally disregarded.

The Reminiscences of Thomas Dibdin, 2 vols

(London: Henry Colburn, 1827), II, 265

The dialogue was better than that of farces in general – and approached nearer to the dialogue of comedy than was desirable: - a farce ought to be upon “the touch and go” throughout; and its language should rush on helter skelter without halting to parry point or defend itself. Comedy has the night before it. But farce is short-lived – flits about the midnight hour – plays late and deep – and ought to have its quick wits about it.

[…]

Readers, we forgot to tell you it was damned – and as a farce, deservedly, wholesomely, well damned! – There were snatches of wit, gleams of humour, which we could have wished to see spared; but as there is no damning to order, - no letting the better part turn King’s evidence, - we were compelled to see the whole lost. The farce was called “Spanish Bonds,” because they rose but to fall, we presume, for we could see no other reason. 1

The London Magazine VIII

(July – December 1823), 322.

- The allusion is to a financial collapse of Spanish bonds related to the 1823 war with France and a large financial crash of Latin American bonds.

Commentary

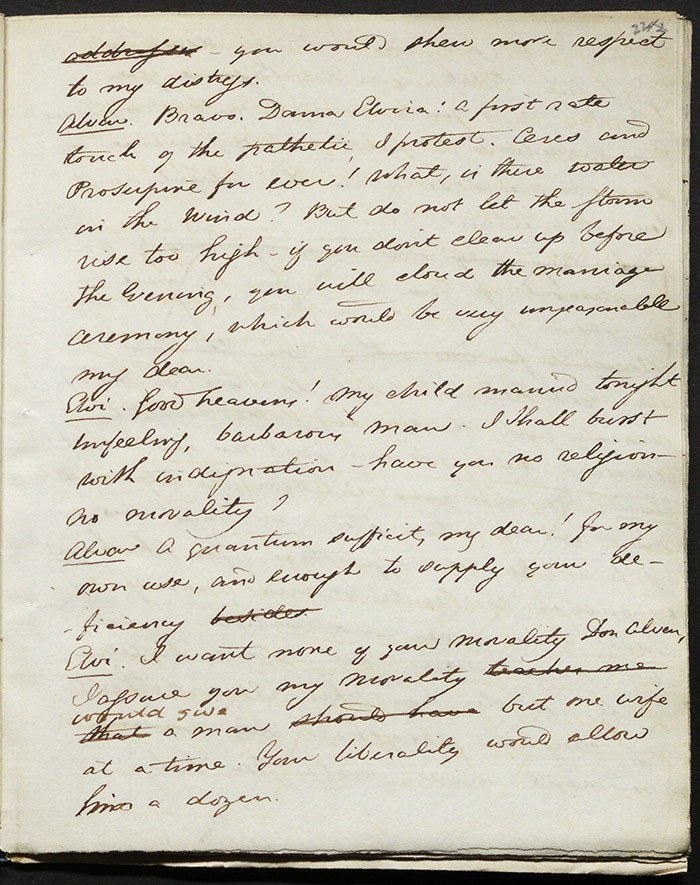

The manuscript (LA 2361) shows a number of emendations and excisions marked in pen. Both authorial/managerial and Examiner (Larpent) edits are in evidence. Many of the Examiner passages are easy to identify as these passages are boxed and crossed out with a large ‘X’ with and marked ‘out’. Censored passages suggest that the Examiner believed the play was alluding to a current scandal involving Frederick, Duke of Cumberland. An unusual feature of this play is that the entire epilogue – a rather lengthy one at that – has been excised by the Examiner.

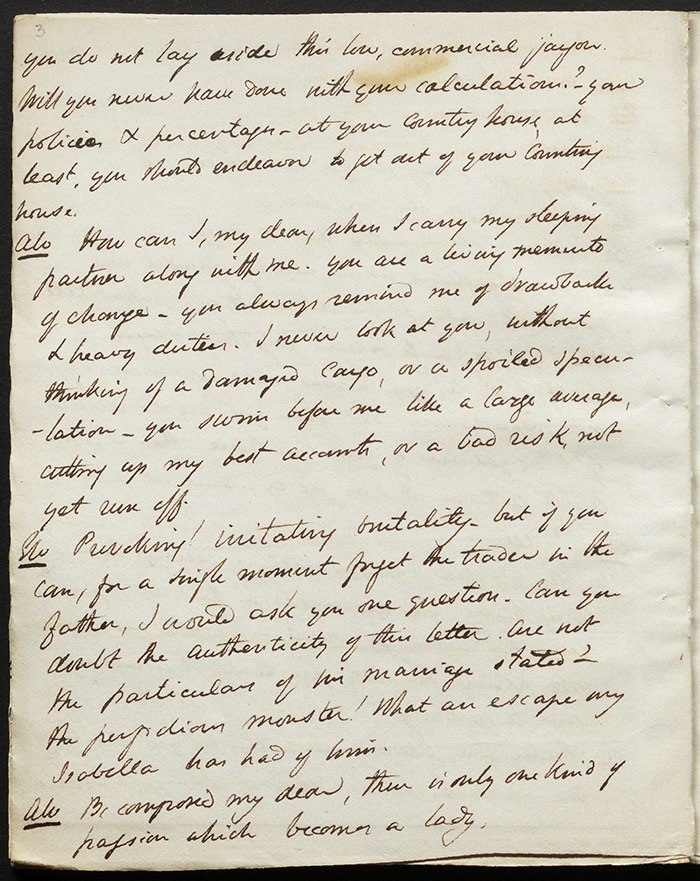

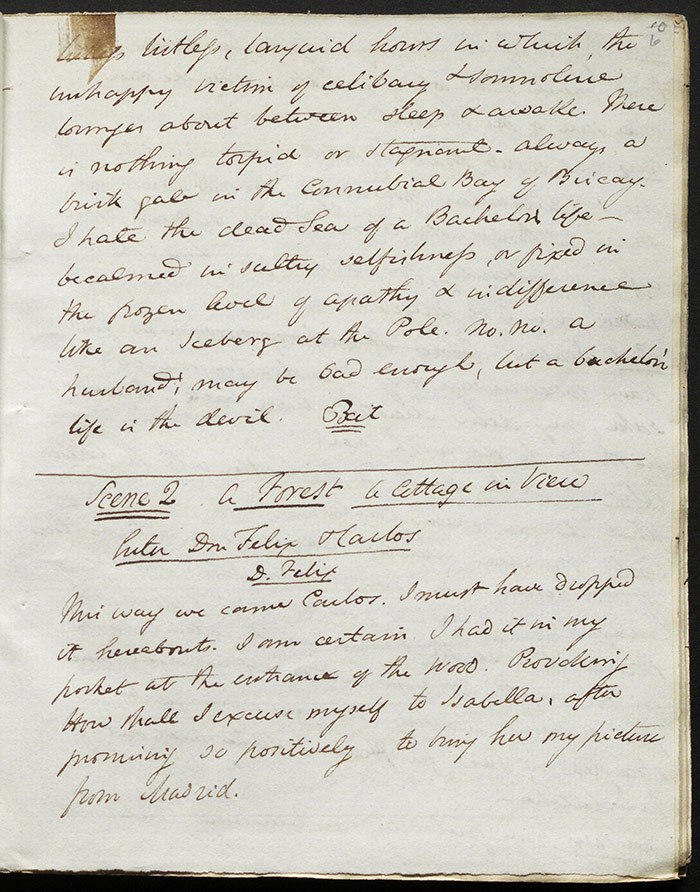

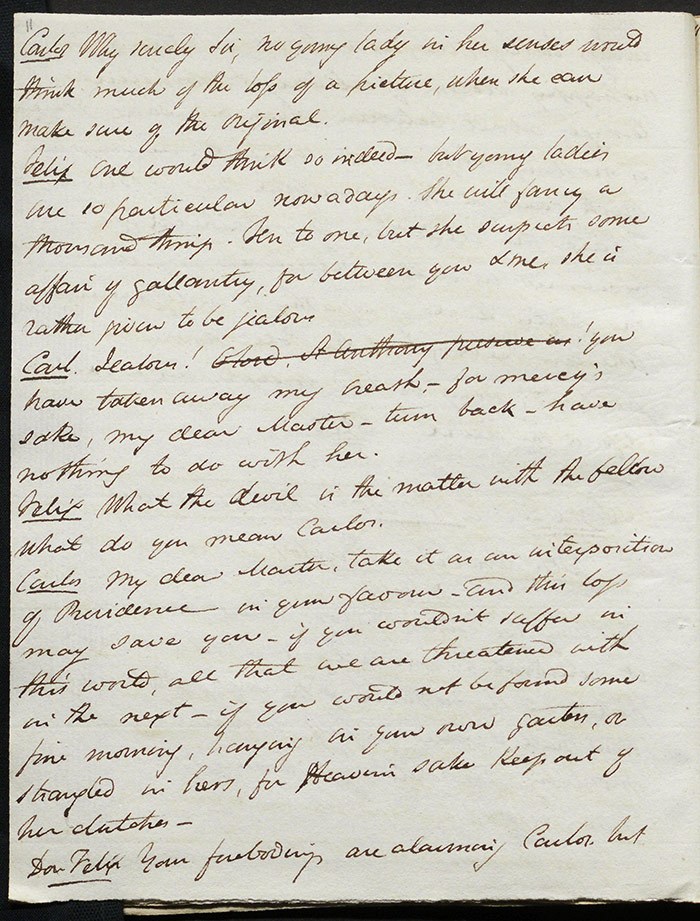

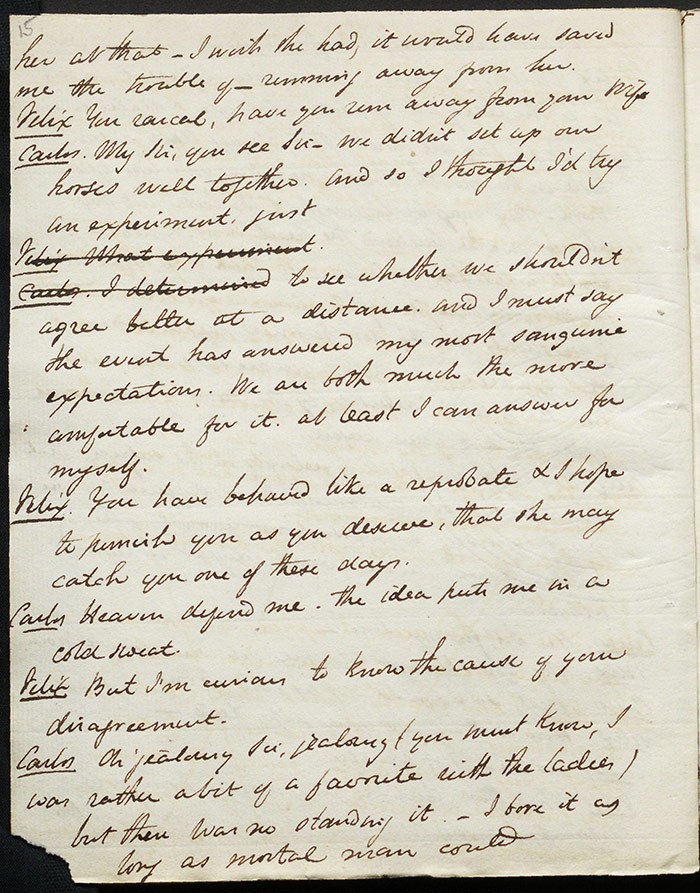

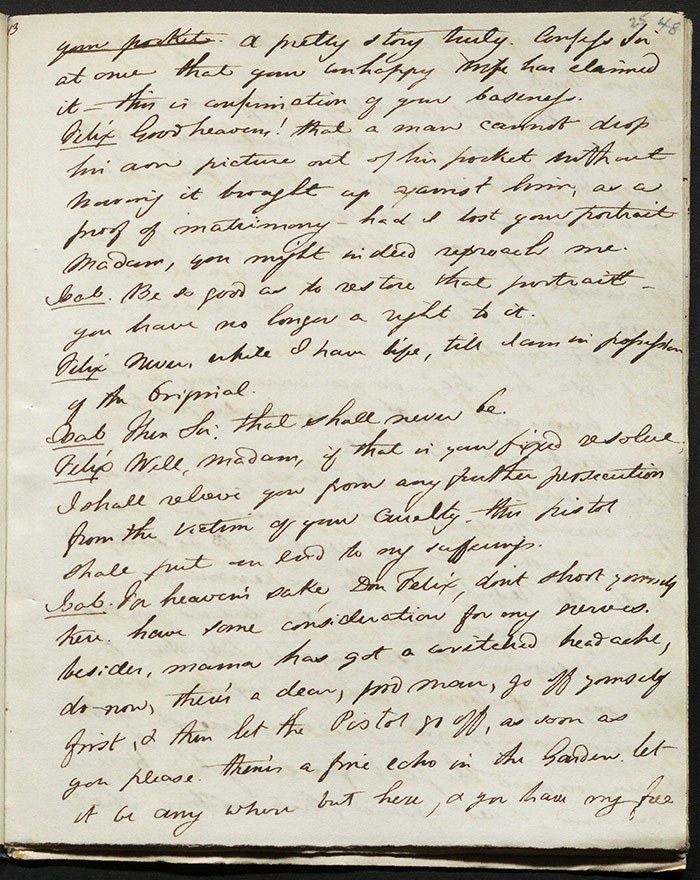

Significant passages marked by the Examiner appear on (f.3v), (f.4r-v), (f.10v), (f.11v), (f.12v), (f.15v), and on (f.34v) - (f.36r), the epilogue. Some context is required to make sense of these excisions.

On 18 June 1823, just six weeks before the performance of Spanish Bonds, Sir George Noel moved that a petition from Olivia Wilmot be referred to a parliamentary Select Committee. Wilmot, who styled herself the Princess of Cumberland, claimed that she was the daughter of Frederick, Duke of Cumberland and brother of George III. She had first made the claim in 1817 but when George III died, the matter escalated. Wilmot dressed her servants in royal livery, placed royal arms on her coach, and called herself Princess Olive. Moreover, she stated that she was a legitimate heir, the child of a secret marriage between her mother and the duke in 1767 which would have made the duke a bigamist when he married in 1771. A number of documents were offered as supporting evidence. Sir Noel’s plea was rebutted by Sir Robert Peel who, in an acerbic and witty speech, pointed out the rather large holes in the story to the great amusement of the house and the matter was dismissed without division.

That this mini-scandal was being referenced in the farce seems more than probable. The Examiner marks a reference to ‘bigamy’, the ‘happiness of a child’, and the ‘honor of his family’ on (f.3v). Don Alvais’s scepticism that ‘Don Felix is mad enough to believe that any woman with a tongue in her head […] would sit down quietly & contentedly & see her husband married to another’ (f.4r) similarly failed to make it past the Examiner. This passage is curious as Elvira, as the dialogue continues, speculates that Don Felix is, in fact, a vampire. The word is repeated a couple of times and the entire passage is marked ‘out’ (f.4v). It is reasonable to suppose that the Examiner felt that the audience might have detected further aspersions on the royal family in this label. It is a term of opprobrium repeated on (f.15v), accompanied by some invective from Isabella and Elvira, and again the passage is marked for omission by the Examiner.

Despite the general tenour of the reviews, there is certainly some evidence of wit in the play as the main plot and the subplot are connected to the Wilmot affair. So while Felix could be mapped onto Frederick, Dorothy—who is a sympathetic character—corresponds to Wilmot. Her mother, Margarita, suggests the parallel: ‘She’s been running all over the country for the last twelvemonth, in search of her scape grace of a husband who has run away from her the lord know where’ (f.10v). Needless to say, this observation was also found objectionable by the Examiner and marked for omission as was Dorothy’s speech shortly afterwards, echoing her mother’s complaint: ‘Heighho. What a lot is mine – condemned to spend my life in seeking for a worthless husband, whom I shall not be able to keep when I have caught – yet in spite of every thing, I cannot help loving the dear, ungrateful, good for nothing fellow’ (f.11v). The allusions become a little bolder as the farce continues. A speech on (f.12v) attacking Count Nunez’s character concludes, playing on ‘grandee’ by calling him ‘a grand D, in the Alphabet of Blockheads’. The speech is struck ‘out’, the Examiner deciding that this was perhaps too close to ‘grand Duke’ for comfort.

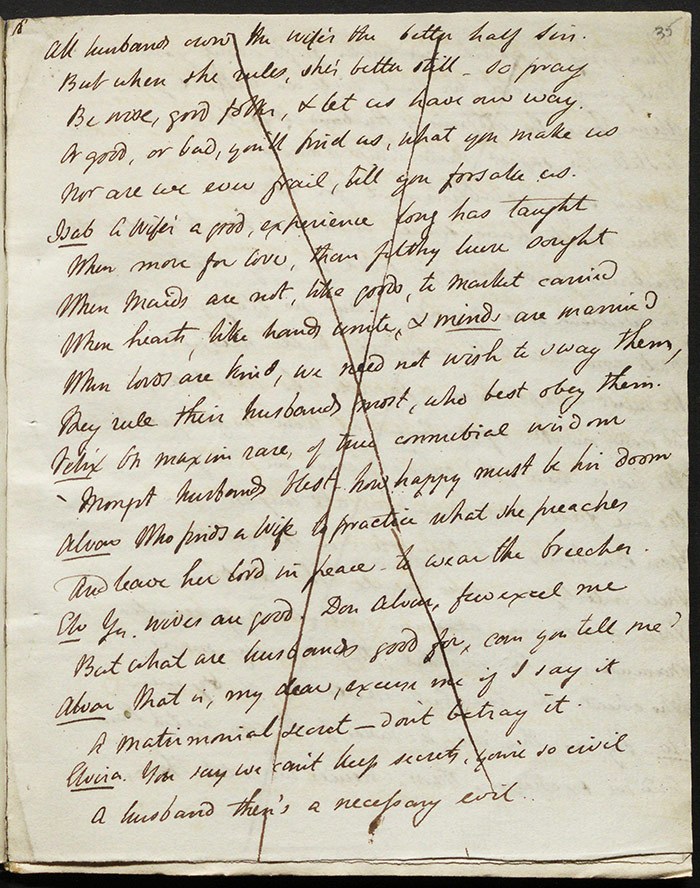

The Examiner suppressed the epilogue, in which the characters reflect on the benefits or otherwise of having a wife, in its entirety, a most unusual occurrence (f.34v) - (f.36r). It may well be the case that the Examiner did not want the subject of marriage to be discussed directly in a way he felt might reference the Wilmot case. Alternatively, it might be that the feminist thrust of these lines, spoken by Isabella, were too feisty for his liking.

A wife’s a good, experience long has taught

When more for love, than filthy lucre sought

When maids are not, like goods, to market carried

When hearts, like hands unite, & minds are married (f.35r)

Elvira has some caustic comments on the qualities of husbands that might also have proved too provocative: ‘But what are husbands good for, can you tell me?’ and ‘A husband then’s a necessary evil’ (f.35r). Alvais has a cynical perspective on family which might also have upset the Examiner: ‘Brats come like Bills presented - & tho’ heedful / We must accept them, & provide the needful’ (f.35v). Moreover, a series of attacks on bachelorhood are made, culminating in ‘Husbands, when kind, are beauty’s, virtue’s rampires / But all you sly, old Bachelor’s are Vampires’ (f.36r).

On first glance, a number of passages look like they have been excised by the Examiner (as they have also been boxed and marked ‘X’) but one can determine by the way the marker carefully prunes the text and the nature of the dialogue that these are authorial/managerial edits. Examples can be found on (f.9.r), (f.18v) and (f.27v). One might also be tempted to speculate that the crossing out of ‘O lord, St Anthony preserve us!’ on (f.6v) was the work of an Examiner who was adverse to religious references on stage but the oath is repeated on the very next folio, suggesting this was a literary decision rather than an error on the Examiner’s part. A reference to a vampire crossed out on (f.14r) is ambiguous: we have already seen that the Examiner is not in favour of this term but the nature of the excision (i.e. crossed out text) is more in line with those made by the author/manager.

Further reading

The Morning Chronicle, 19 June 1823

K. D. Reynolds, ‘Serres , Olivia (1772–1835)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25106, accessed 10 Sept 2015]

Olivia Wilmot Serres, The life of the author of the Letters of Junius: the Rev. James Wilmot, D.D. (London: Sold by E. Williams, 1813)