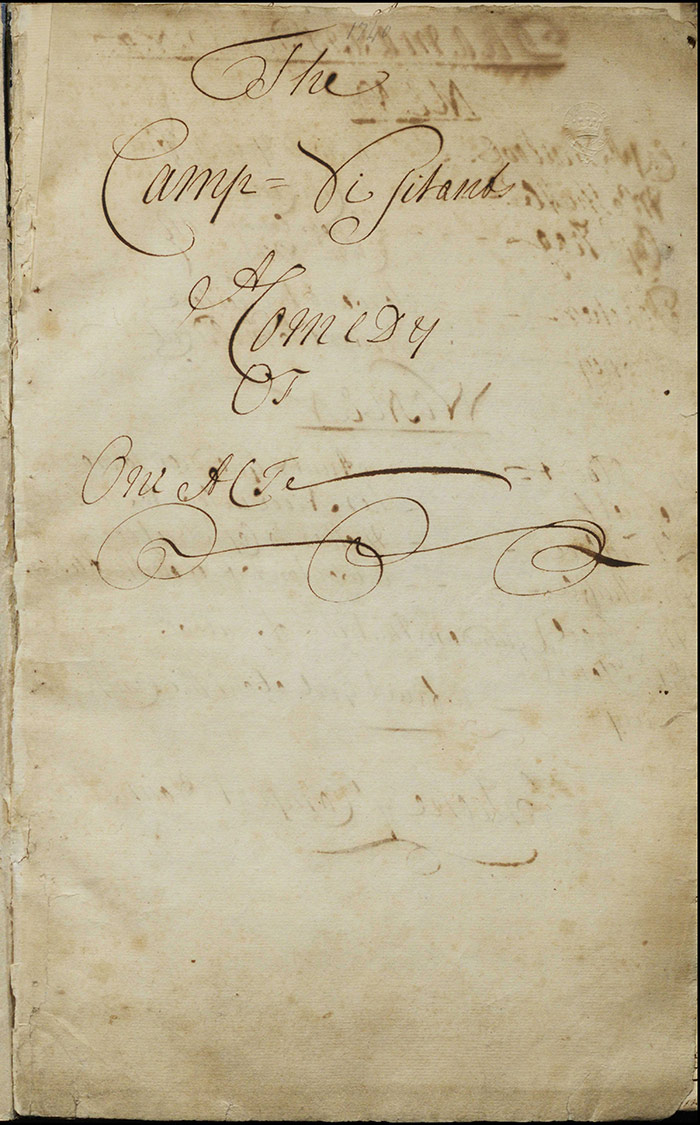

The Camp Visitants (1740) LA 23

Author

James Miller (1704-1744)

Miller was from Dorset and after a brief stint as a working for a merchant, he attended Wadham College, Oxford. He was eventually ordained and became lecturer of Trinity Chapel, Conduit Street and Preacher at Roehampton Chapel, both in London. However, his ecclesiastical career would always be impeded by his theatrical interests, he was even chastised by his bishop, Edmund Gibson, on this score.

Miller authored The Humours of Oxford (DL, 1730) while at university and one can get a sense of his provocative style from the comedy’s depiction of dissipated university life, including a sketch of a university fellow based on the then warden of Wadham. Theophilus Cibber commented that ‘as it was a lively representation of the follies and vices of that place, procured the author many enemies’ (V: 332). In 1731 he published Harlequin-Horace which attacked pantomime and opera.

Miller’s popularity also took a hit after his The Coffee House (1738), an afterpiece which was perceived to have satirized Dick’s Coffee-House at Temple Gate, a favourite of the Templars. The Coffee House featured a Bayes character, perhaps meant to represent Richard Savage, according to a Samuel Johnson anecdote. There is also a censorial excision relating to the Spanish conflict where Bawble mourns the loss of castrato Farinelli, who had recently departed London for the Spanish court: ‘O cruel Spain will Nought Suffice / Will nought redeem this lovely Prize? / Take all our Ships, take all our Men, / So we Enjoy but him again’ (LA 3, f.6r; two large Xs in the margins indicate the last two lines are prohibited). The idea that English military valour would be so mild as to be undermined by the loss of Italian opera resonates with representation of the British military in The Camp Visitants.

Miller’s writing became ever more political. Leaving aside The Camp Visitant, he produced a number of works which attacked the Walpole ministry. The Larpent manuscript of Art and Nature (1738) has a jibing reference to the pro-Walpole newspaper The Hyp-Doctor scored out (LA 2, f.16r). His scathing poem Are These Things So? (1740) was voiced through the persona of Pope and asked whether Walpole might be ‘the fatal Cause of Britain’s Shame, / The Spend-thrift of her Freedom and her Fame?’ The poem caused something of a sensation and a number of replies were penned including one from Miller himself where Walpole confidently voices The Great Man’s Answer to satiric effect.

Miller also translated a number of works by Moliere in collaboration with Henry Baker and went on to adapt a number of French dramatic works for the London stage. He wrote a libretto for a successful oratorio Joseph and his Brethren (1744) and his oppositional stance was again evident in the portrayal of Joseph as a pure political leader, unlike Walpole. Miller’s adaption of Voltaire’s Mahomet was staged in 1744; however, he needed someone else to complete it due to illness and he died on the third date of its run.

Plot

[Scene 1]

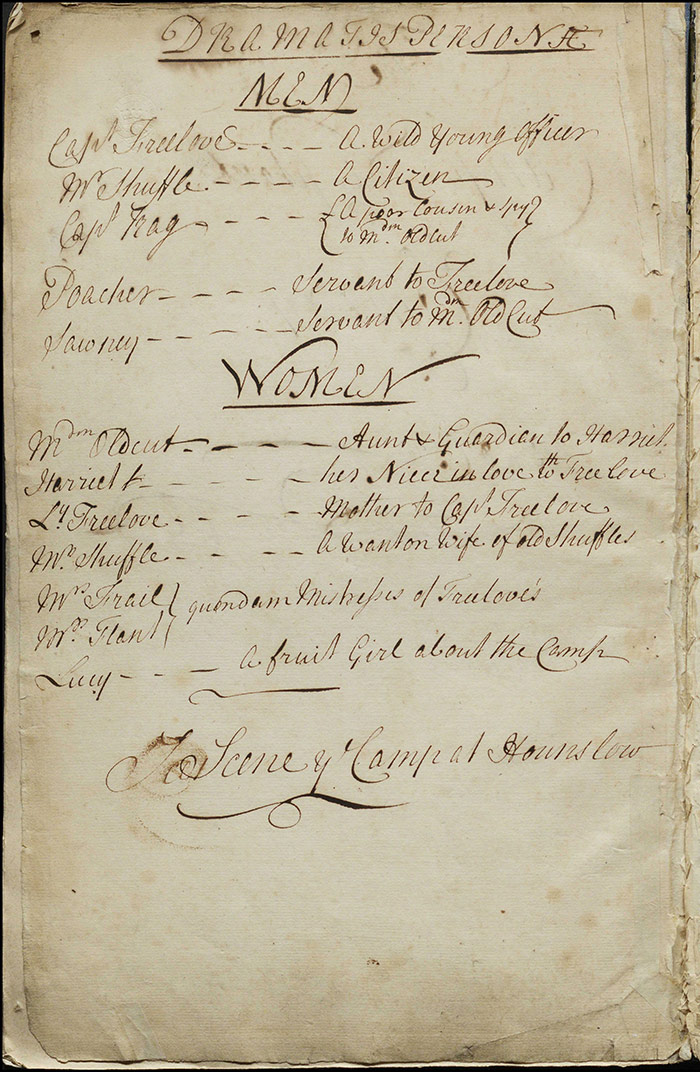

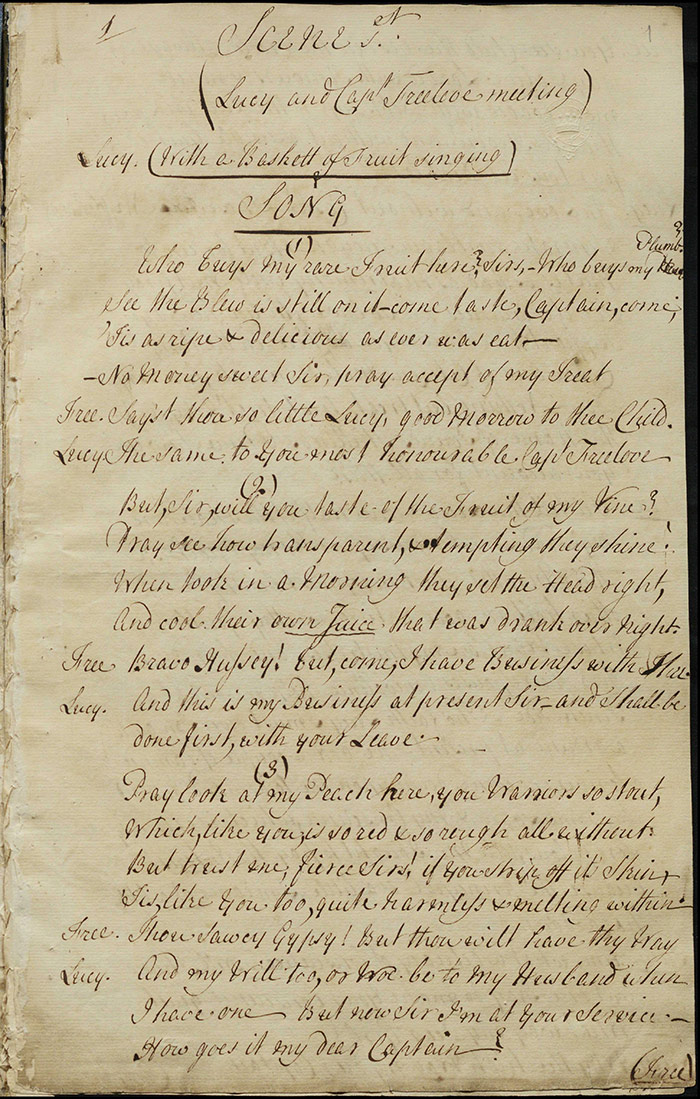

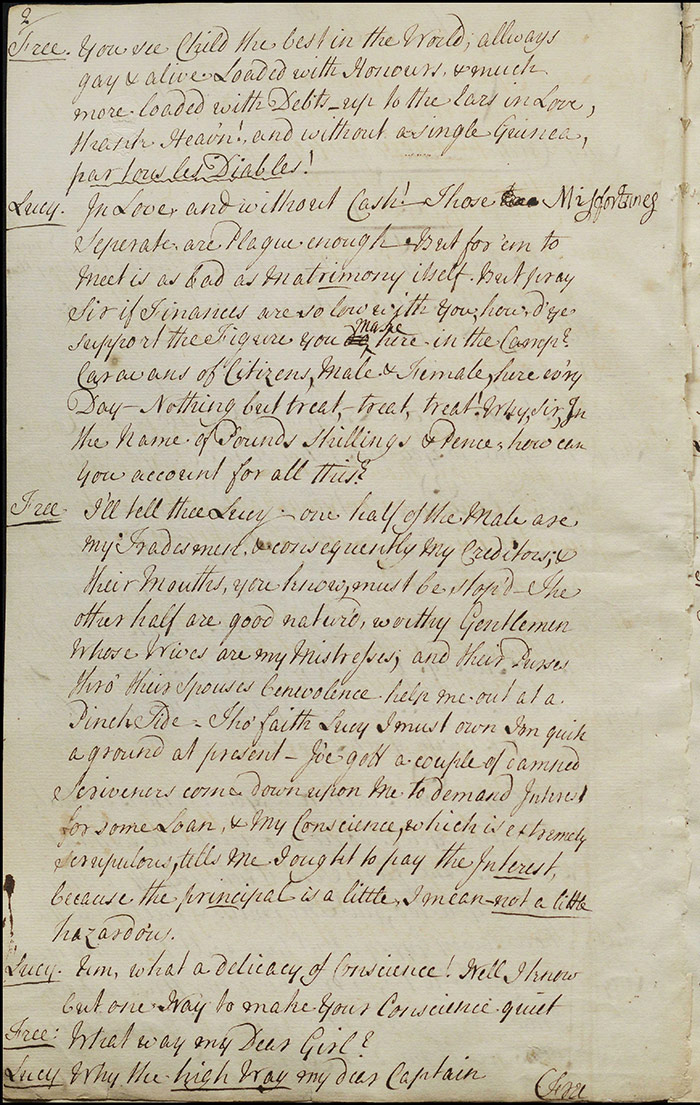

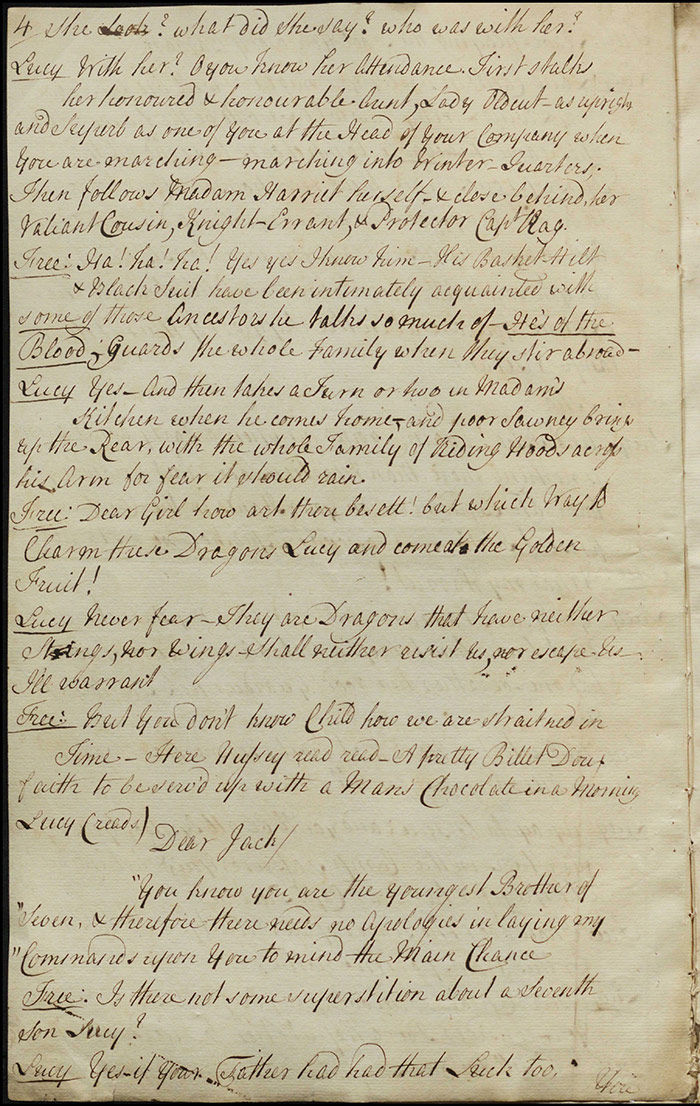

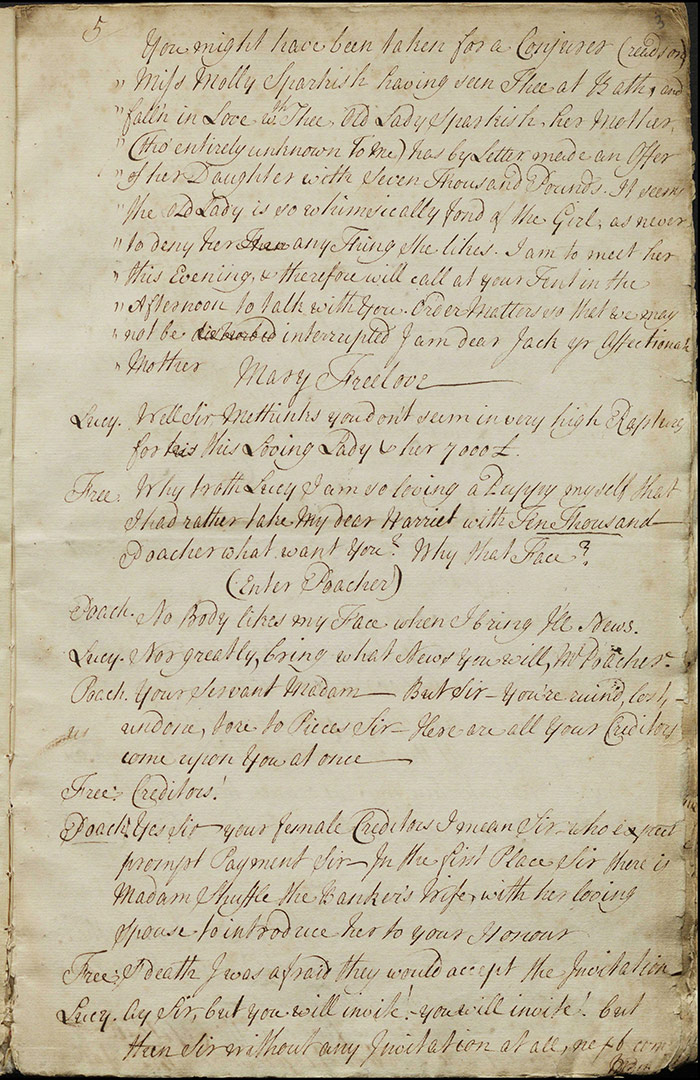

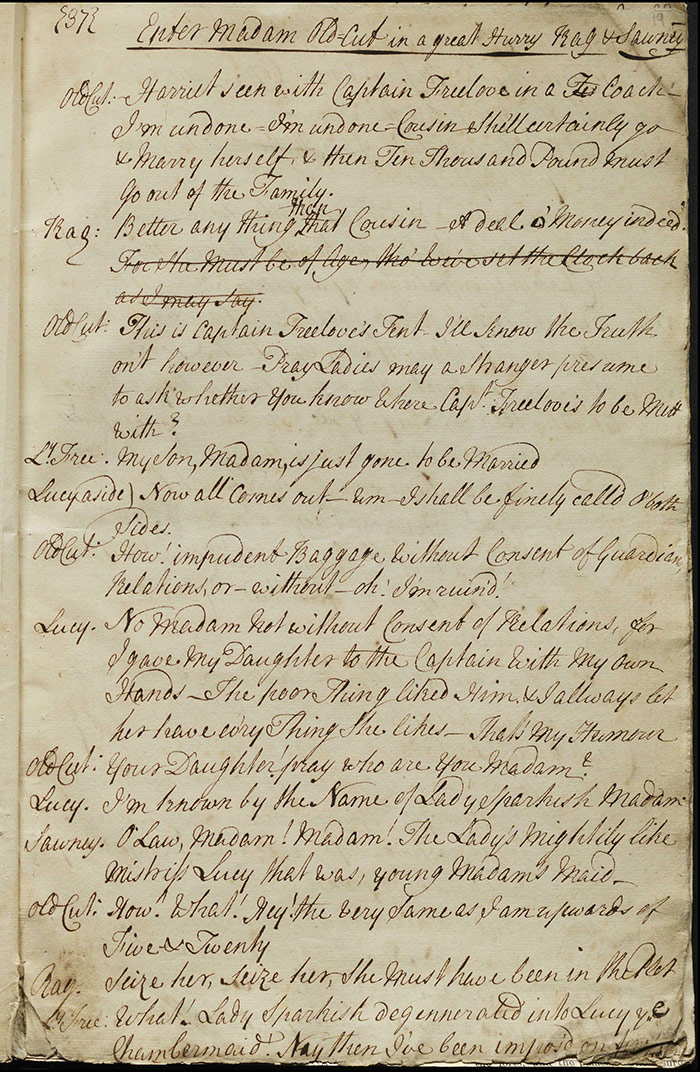

Lucy, a fruit girl, arrives to the camp to sell her wares to the soldiers when she is met by Captain Freelove who tells her he is doubly unfortunate to be in debt and also in love. She tells him that his lover—and her former mistress—Harriet is in the camp looking for him, accompanied by her aunt and guardian, Madam Oldcut, and Oldcut’s Scottish cousin and spy, Captain Rag. However, Freelove has just received a letter from his mother, Lady Freelove, to say that he has an offer of a wife, Molly Sparkish, with £7000 that she is coming to discuss with him. Enter Poacher. He brings bad news that other ‘female Creditors’ (f.3r) of Freelove’s have arrived in the camp: Mrs Shuffle (and her banker husband Shuffle), Mrs Frail, and Mrs Flant (i.e. Flaunt). Exeunt.

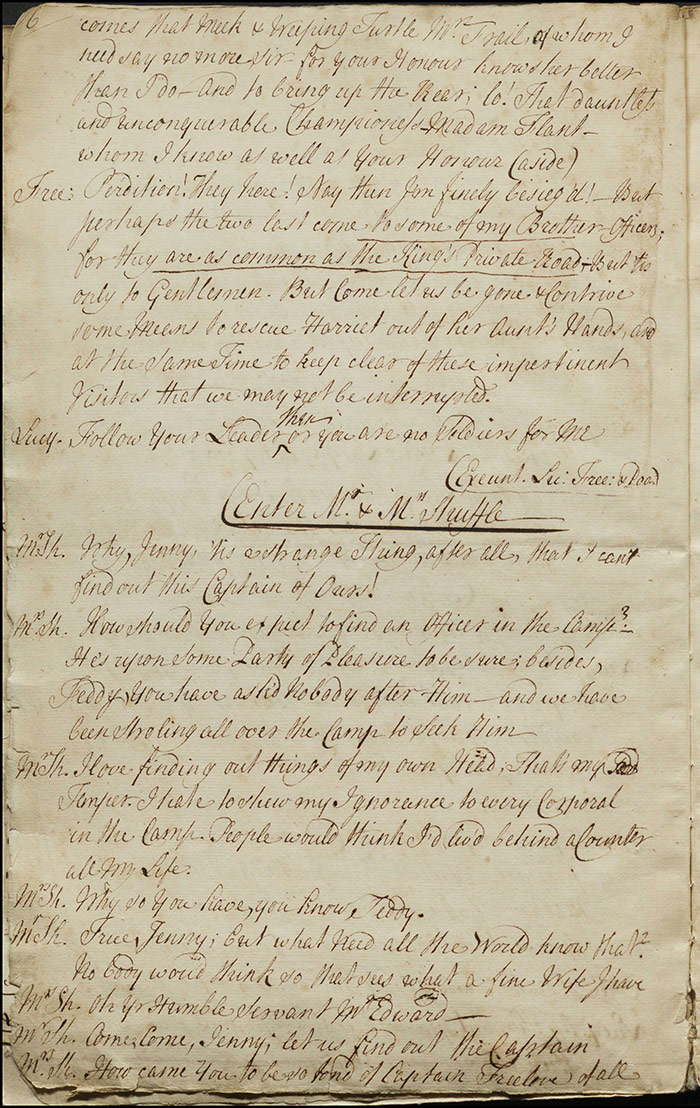

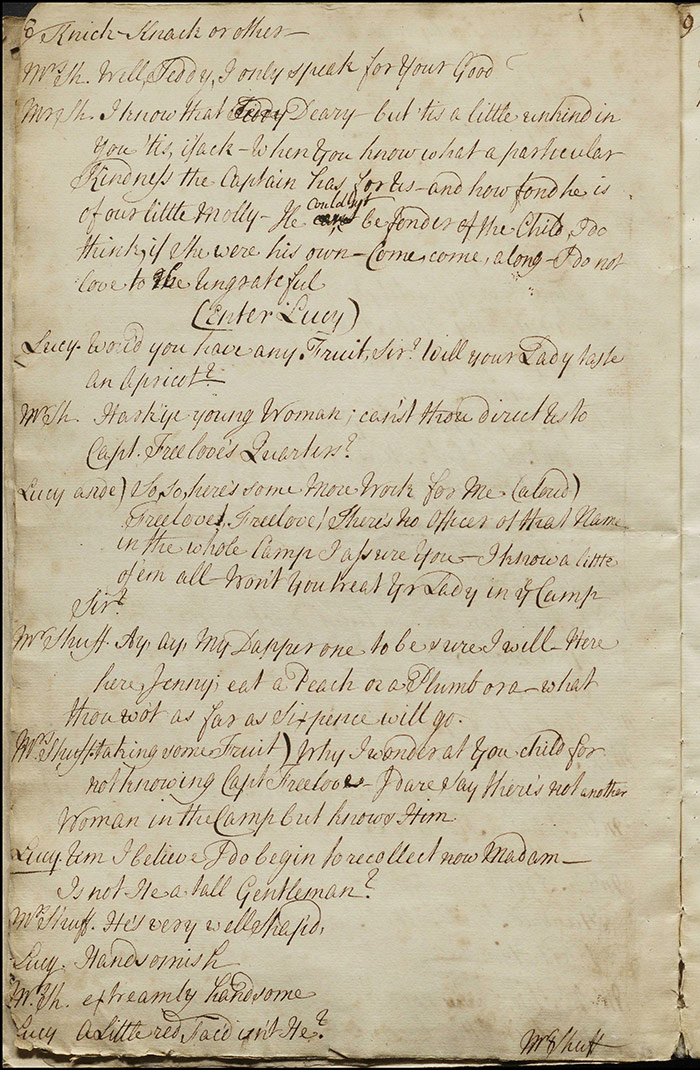

Enter Mrs and Mrs Shuffle. Shuffle waxes lyrical about Freelove’s care and hospitality of Mrs Shuffle and is delighted to be able to visit in return. She is more nervous about meeting him with her husband and reminds Shuffle of the £200 they lent him but Shuffle dismisses this as a bagatelle. As the conversation develops, Shuffle reveals that he considers Freelove a suitable husband for his daughter, Molly. Enter Lucy who tries to confuse and distract them from finding Freelove, eventually telling them that he has left the camp for Hounslow due to illness. Mrs Shuffle, panicked, decides to go to Hounslow immediately while Shuffle, more skeptical, continues to search the camp.

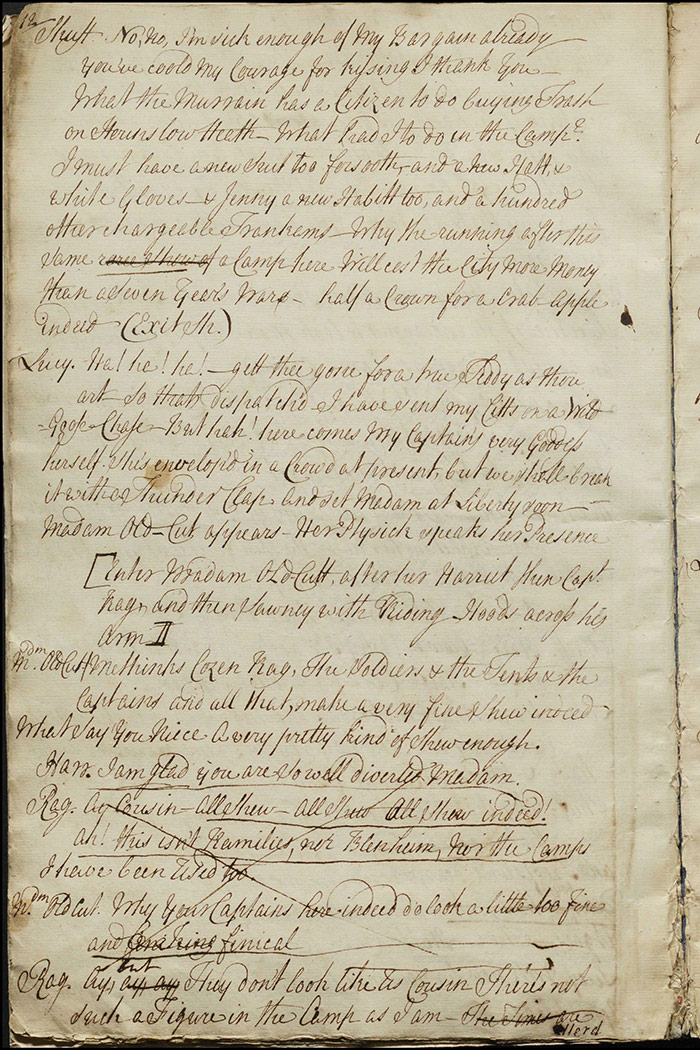

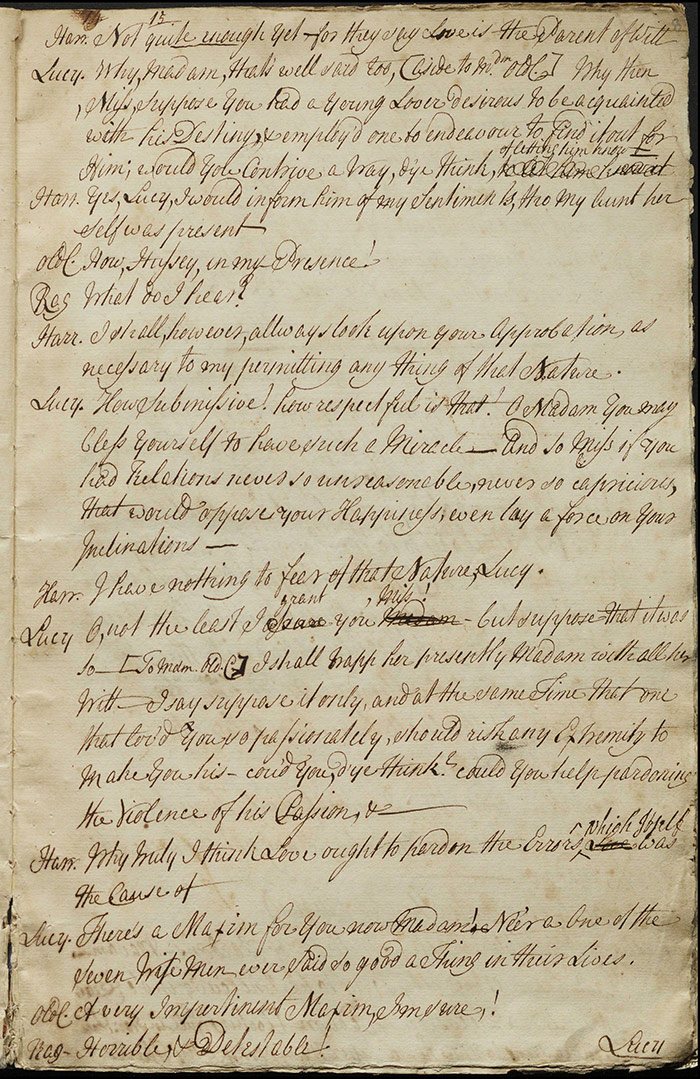

Exit Shuffle and Mrs Shuffle and enter Madam Oldcut, Harriet, and Captain Rag. Lucy manages to let Harriet know that Freelove is getting married but asks her to hear him out. Mrs Oldcut recognizes Lucy and demands they stop whispering. Lucy and Harriet continues to discuss love in front of Oldcut and Rag, somewhat to their elders’ consternation. Harriet indirectly signals to Lucy to tell Freelove that she is open to hear him out.

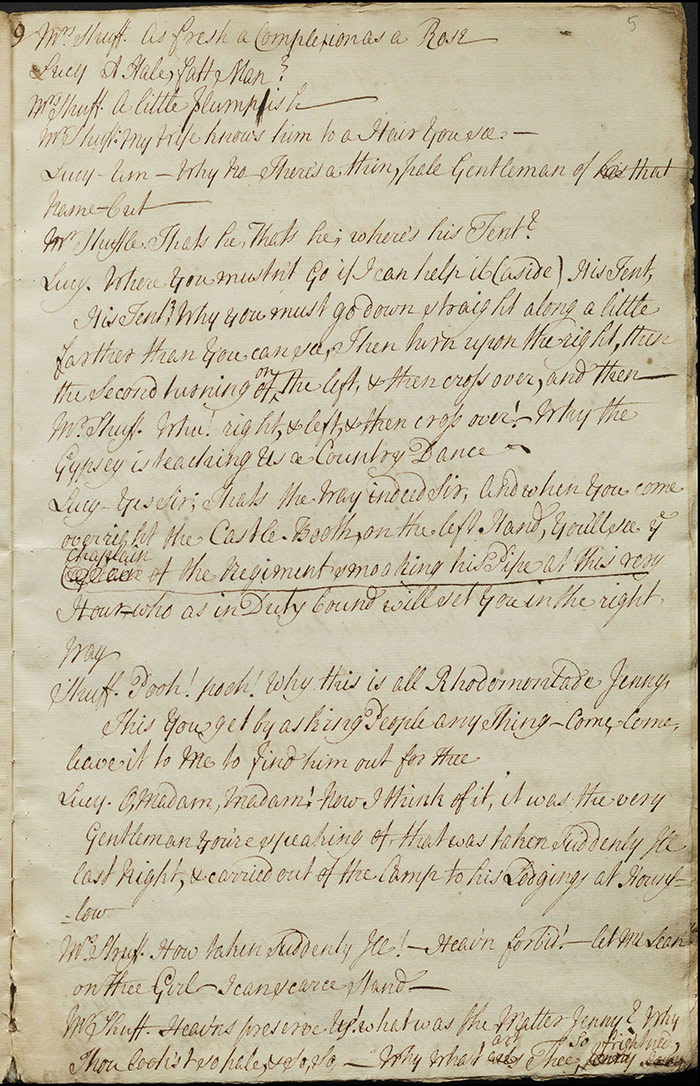

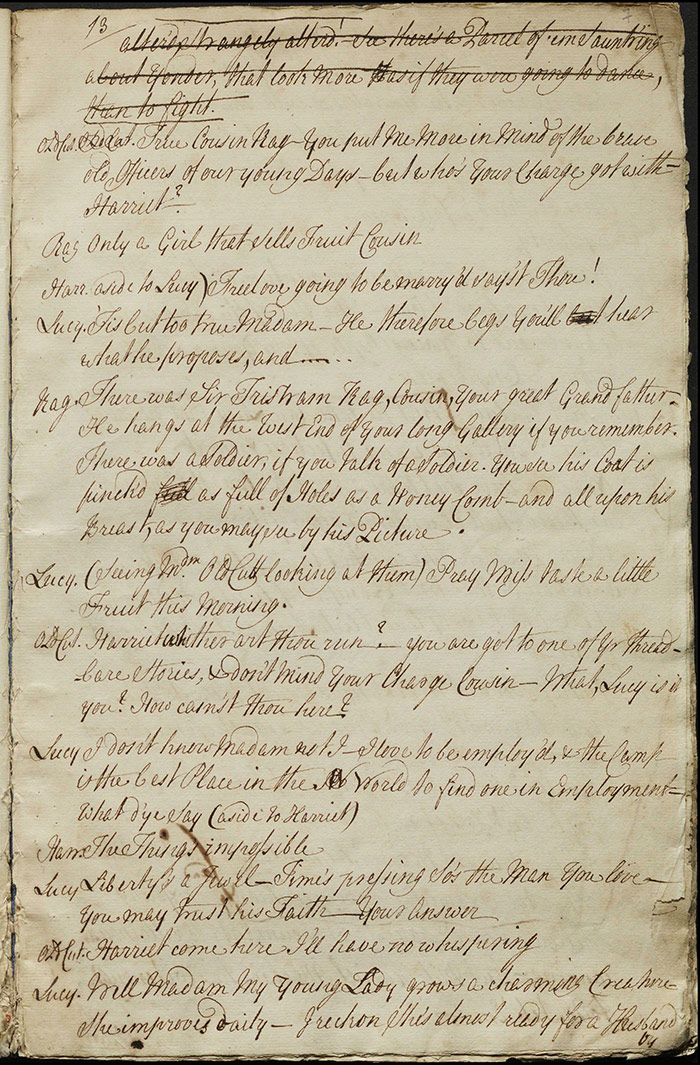

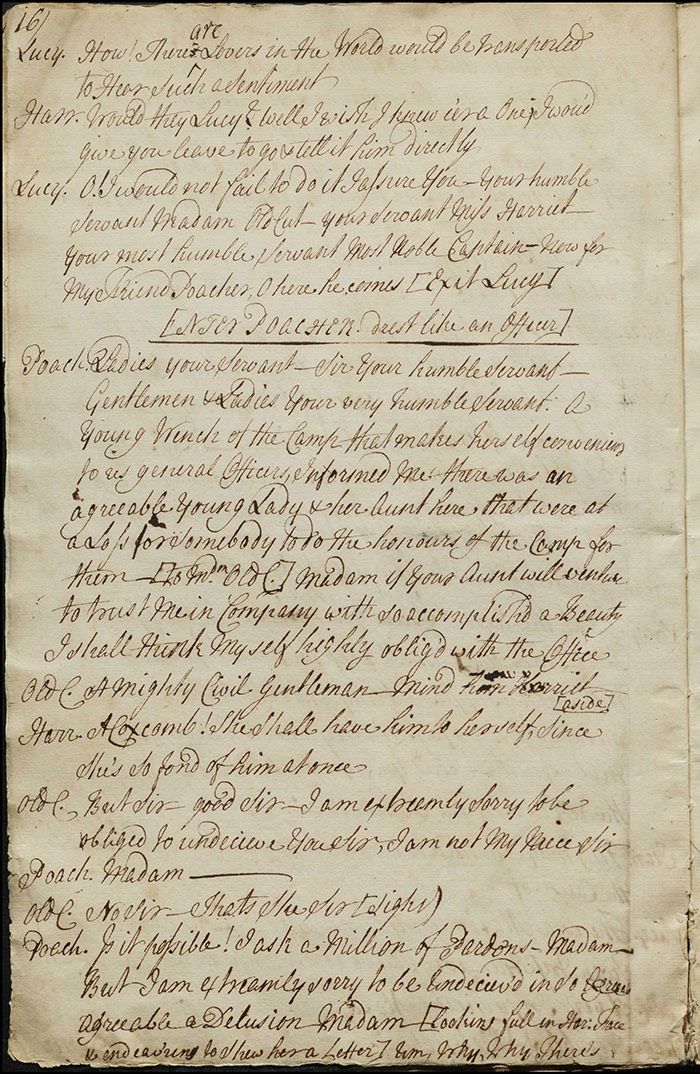

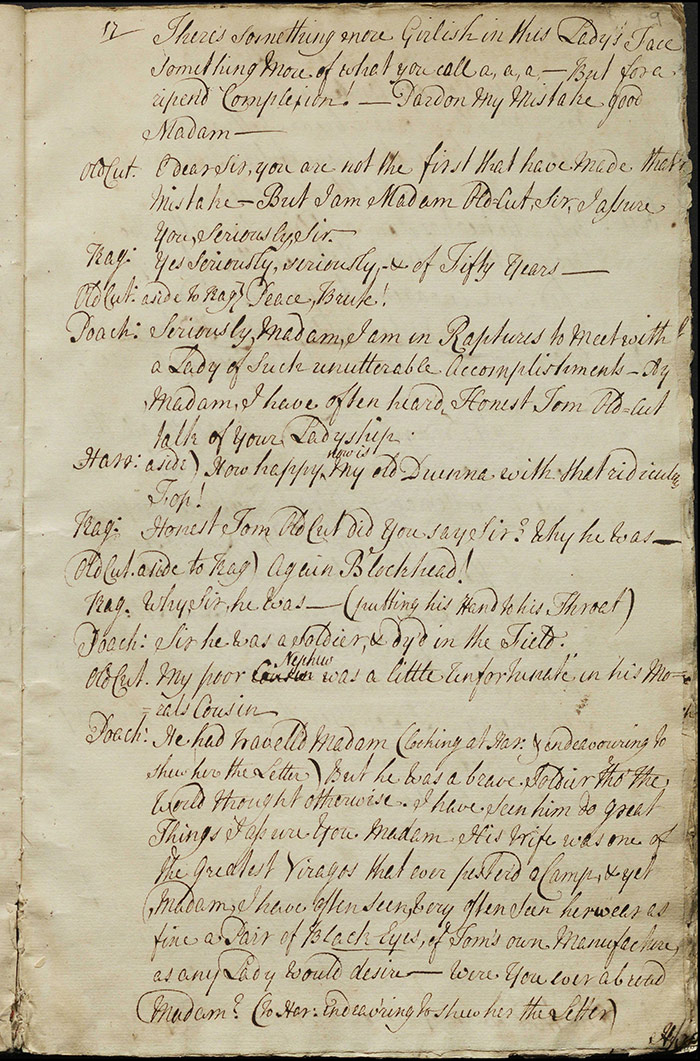

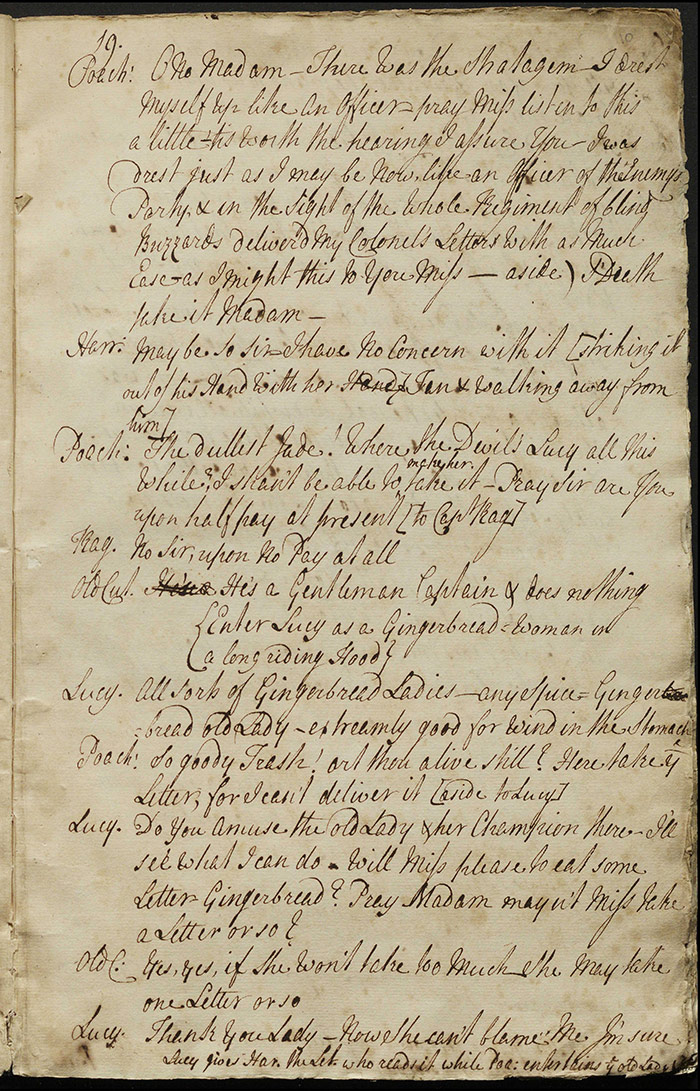

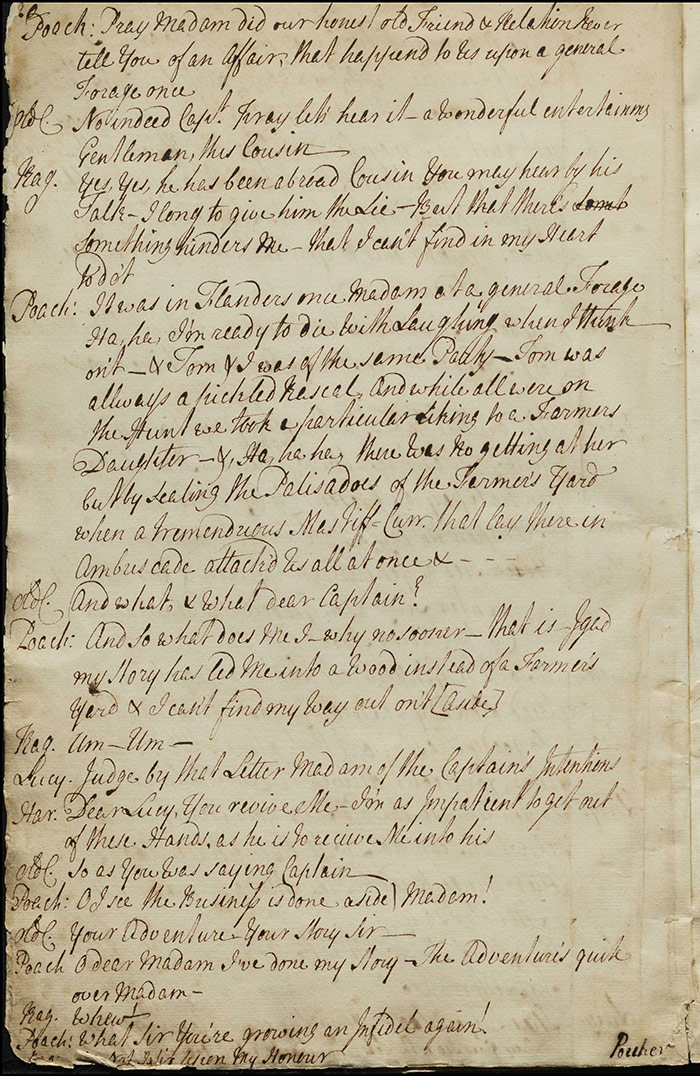

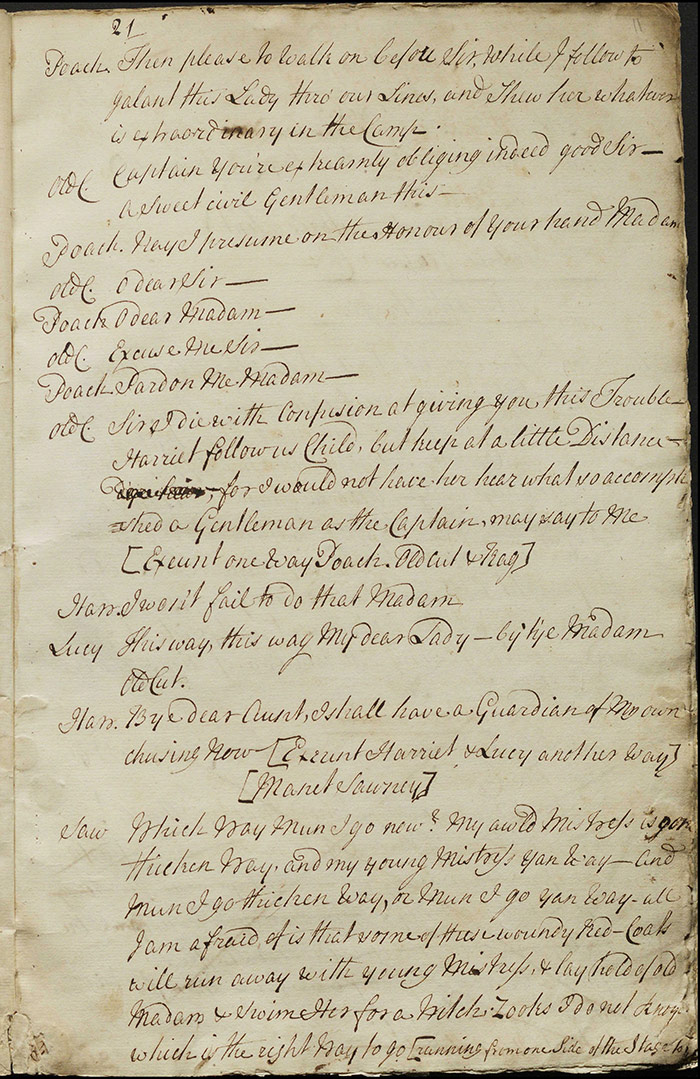

Lucy exits and Poacher enters, dressed like an officer. He charms Mrs Oldcut by identifying her as the niece and offering to show her round the camp. His coxcombery delights her but does not deceive Harriet. As he continues to talk to Mrs Oldcut about her nephew, the soldier Tom Oldcut, he tries to pass a letter to Harriet to no avail, she being underwhelmed by him. Enter Lucy. Poacher passes the letter to her in exasperation she manages to gives it to Harriet as Poacher distracts Mrs Oldcut. The letter galvanizes Harriet and she is determined to get to Freelove. Poacher, who has thoroughly charmed Mrs Oldcut, offers to escort her through the camp. She is delighted and even asks that Harriet keep a little distance: ‘for I would not have her hear what so accomplished a Gentleman as the Captain, may say to me’ (f. 11r). Exeunt Poacher, Oldcut, and Rag one way, Harriet and Lucy another. Manent Sawney who gives a brief confused speech about which party he should follow to comic effect.

[Scene 2] (f.11v)

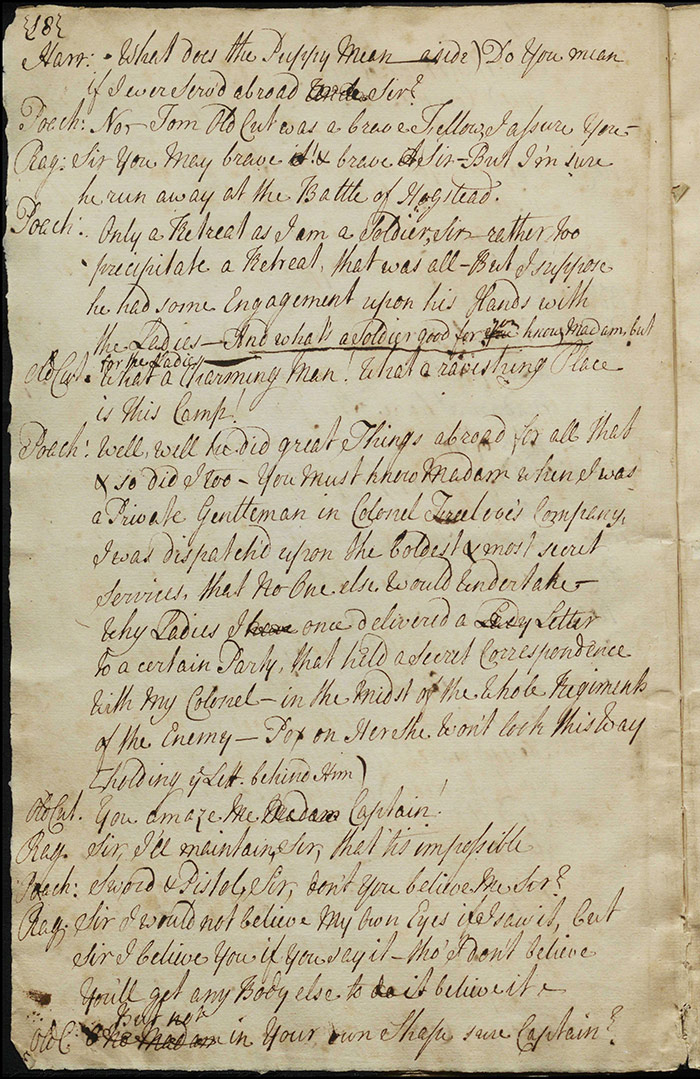

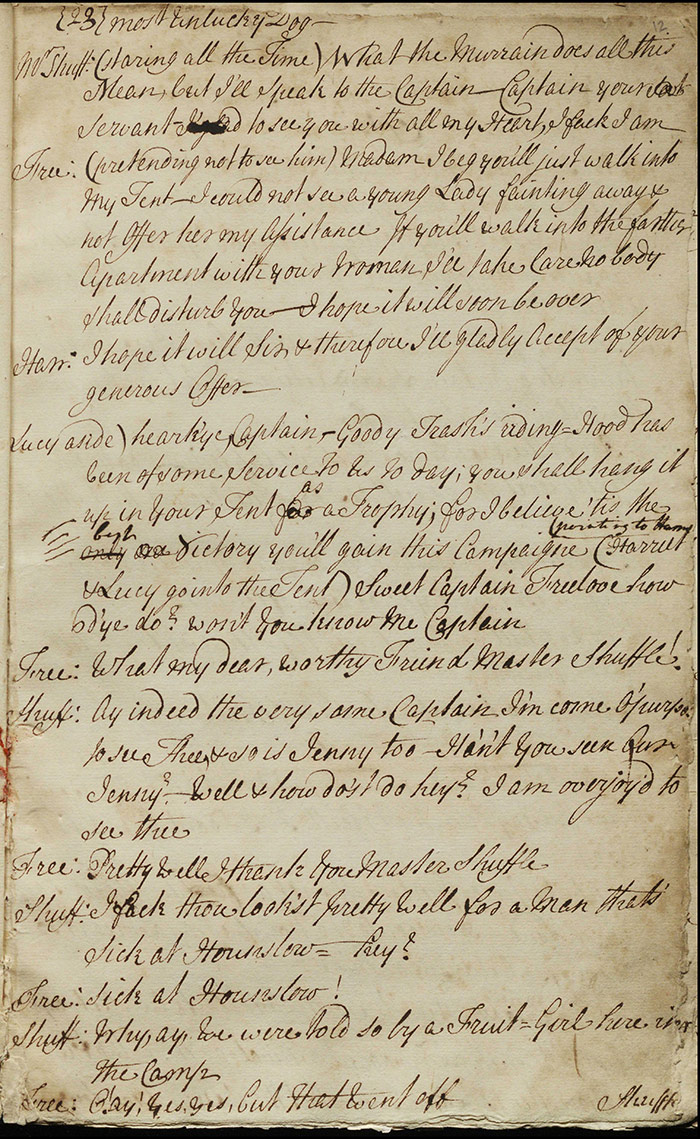

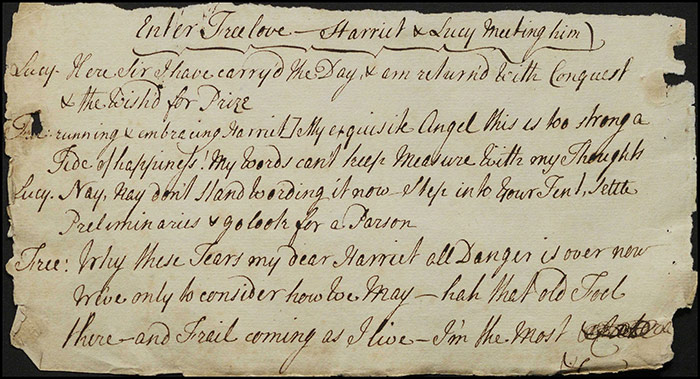

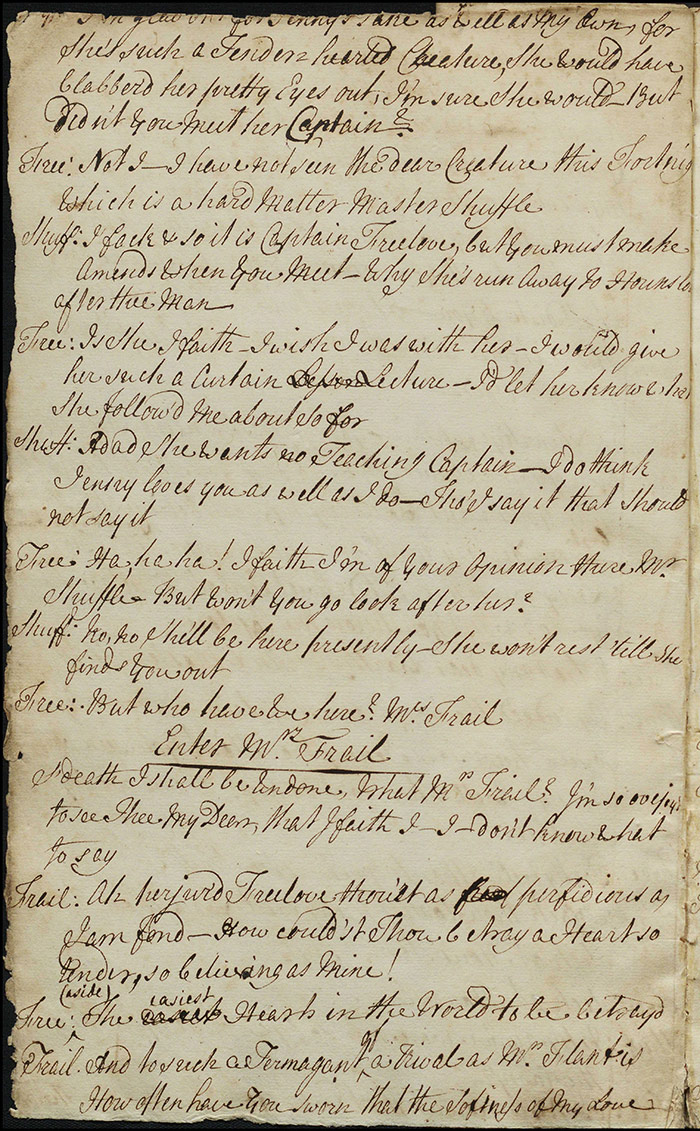

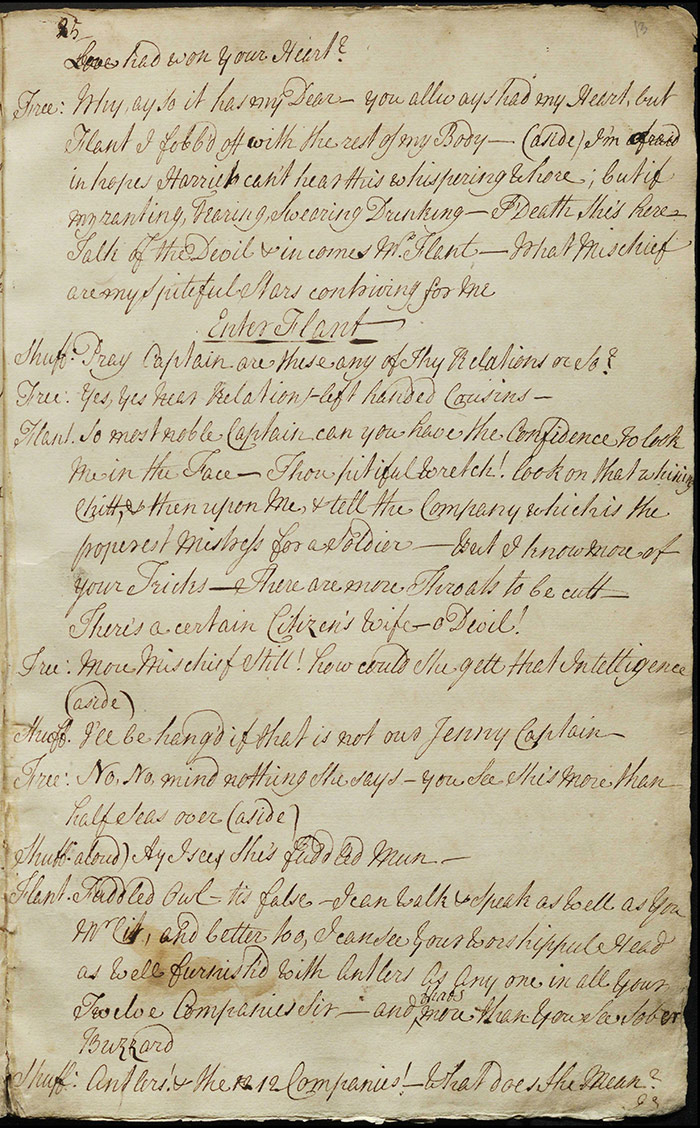

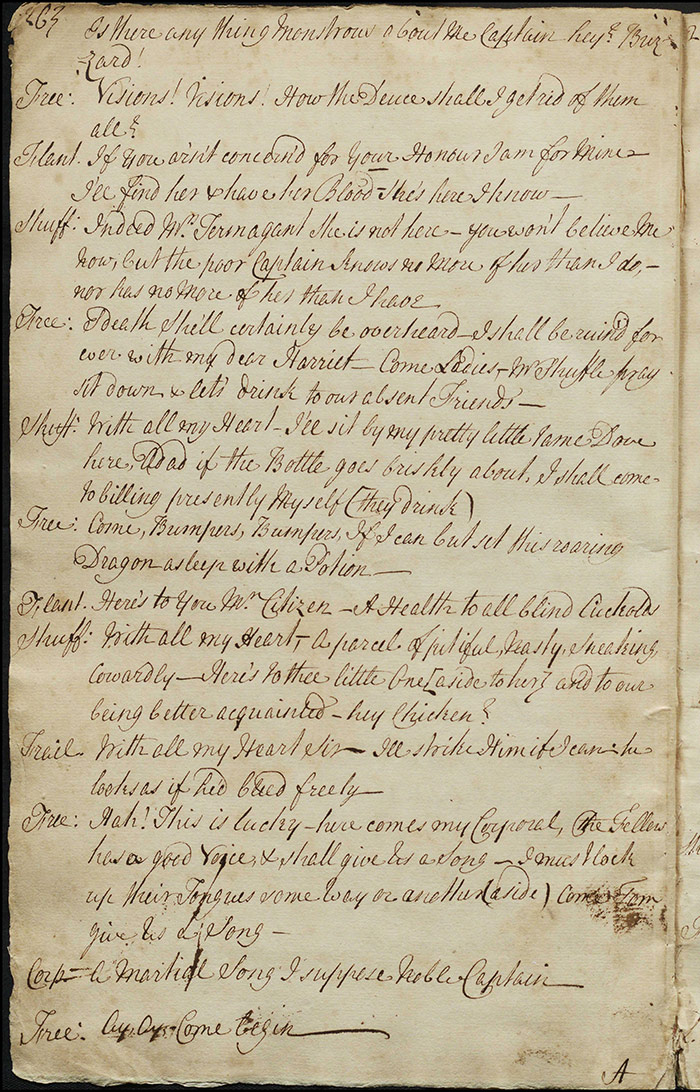

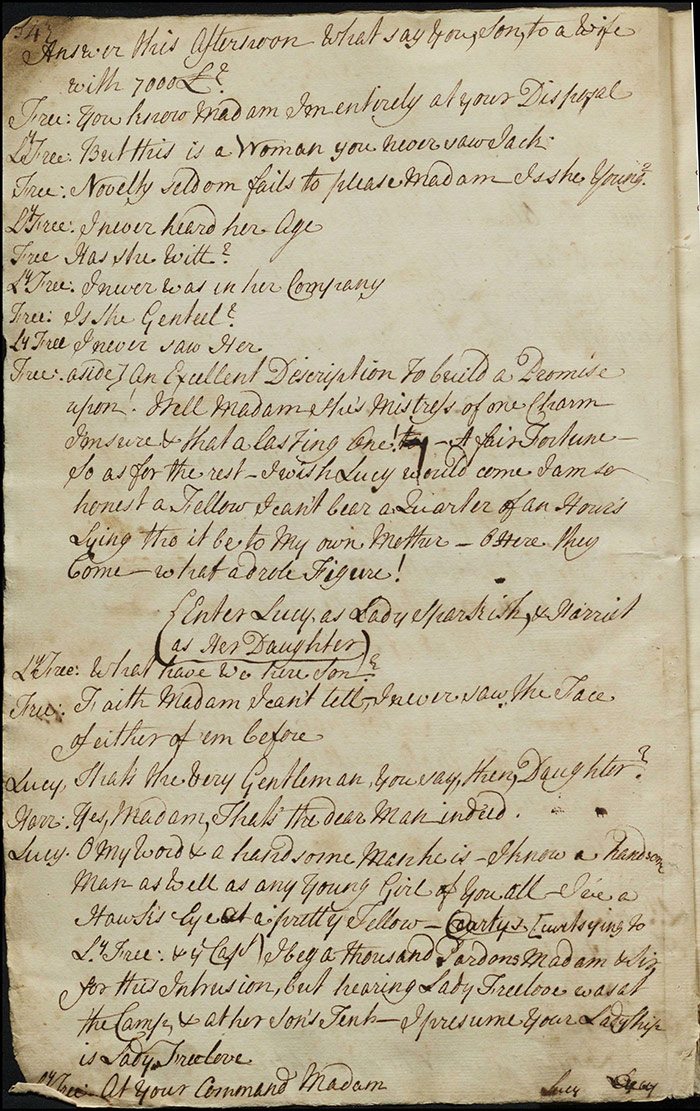

Inside Freelove’s tent. Enter Mr Shuffle. He passes comment on the empty tent. Enter Freelove and Harriet and Lucy meet him. Freelove and Harriet rejoice as Shuffle looks on in amazement and then interjects. Freelove, pretending he cannot hear him, escorts Harriet into the back room of the tent, pretending that she has fainted. Shuffle greets Freelove again, surprised to see him looking so healthy and puzzled he did not meet Mrs Shuffle in Hounslow. Mrs Frail enters. She berates him for spurning her for Mrs Flant; he is nervous over whether Harriet can hear her. Enter Mrs Flant who also begins to abuse him. Freelove explains her away to Shuffle by suggesting she is drunk and tries to stop his companions from speaking through drink and song. Lady Freelove enters. She is amazed at the proceedings and Freelove pretends that he is the unwitting victim in this debauched scene. Enter Poacher, dressed as an office. Freelove addresses him as Captain Fossett and Poacher plays along, his feigned drunkenness eventually repels Lady Freelove who exits. Shuffle also leaves with a view to seducing Mrs Frail/Flant (MS is unclear). Freelove tries to usher Harriet out but he spots Mrs Shuffle: Lucy brings Harriet hurriedly back inside the back room of the tent.

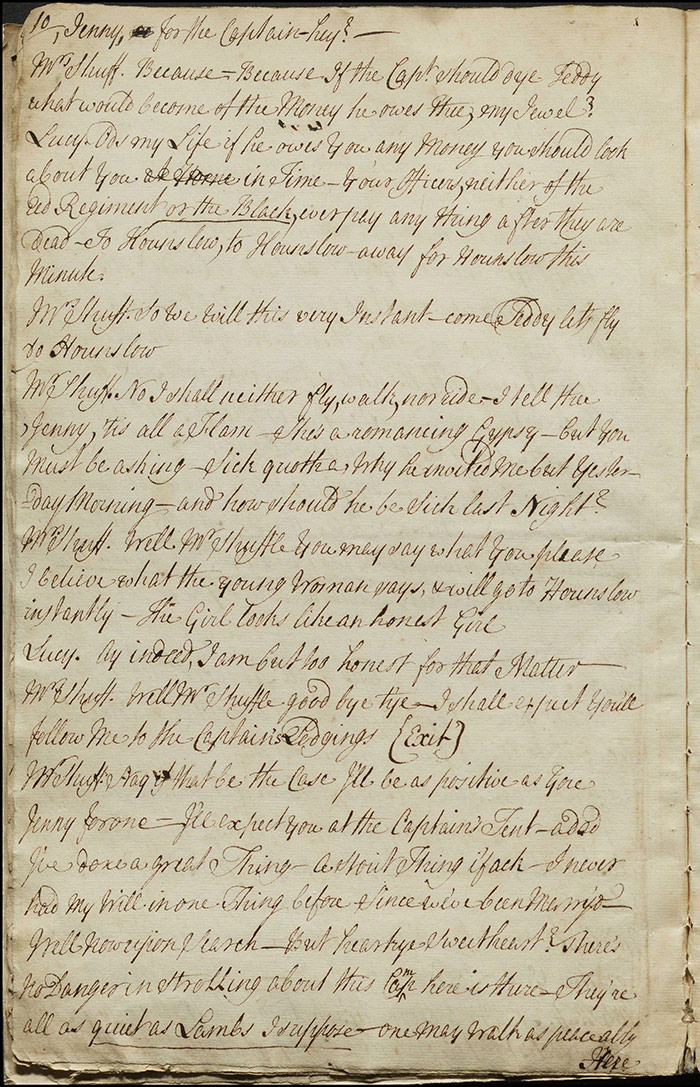

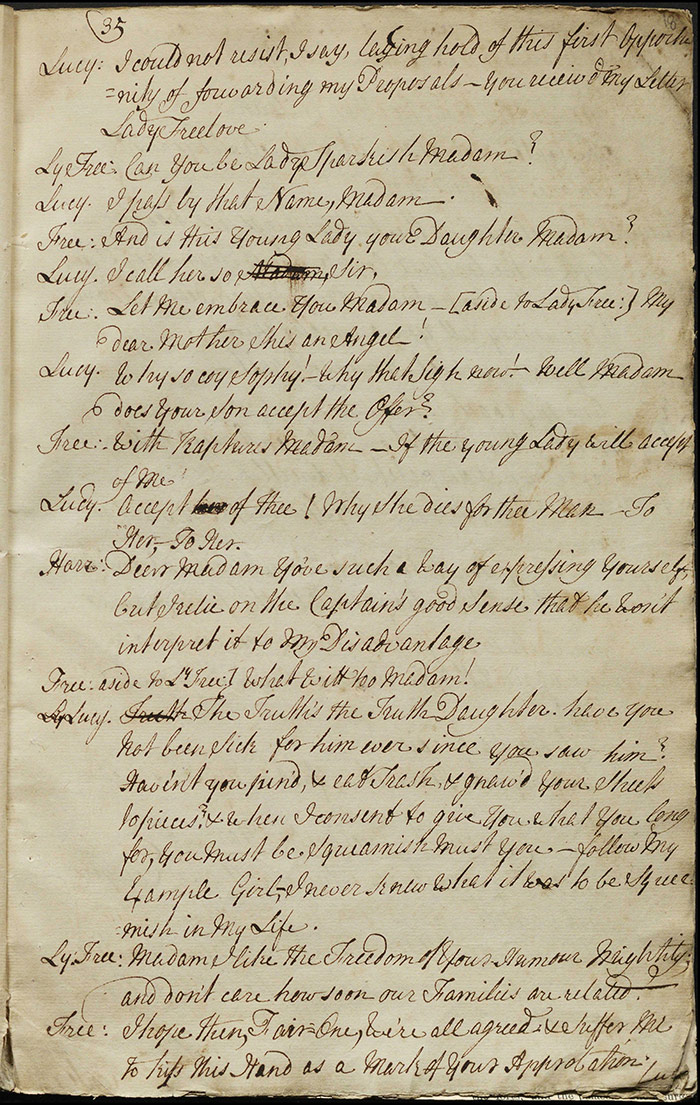

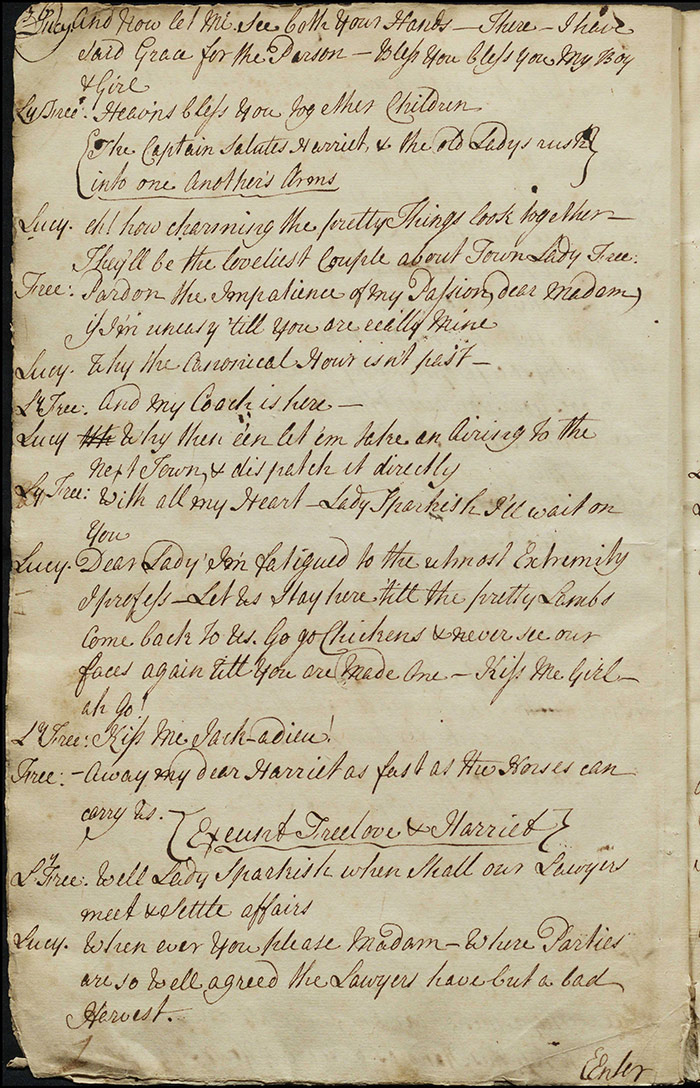

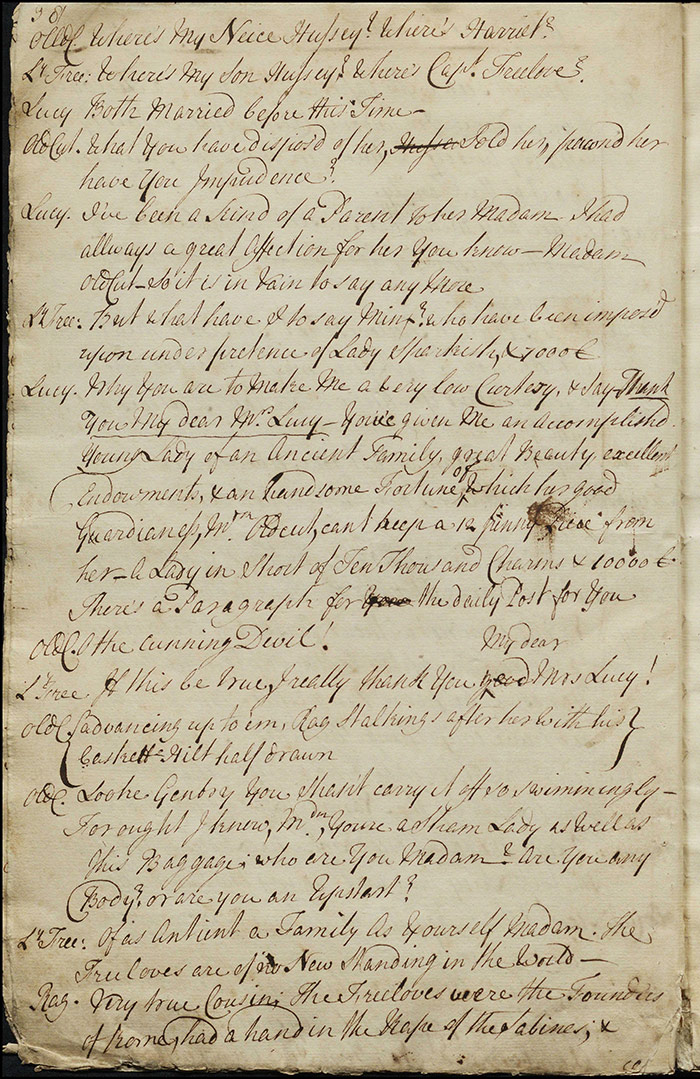

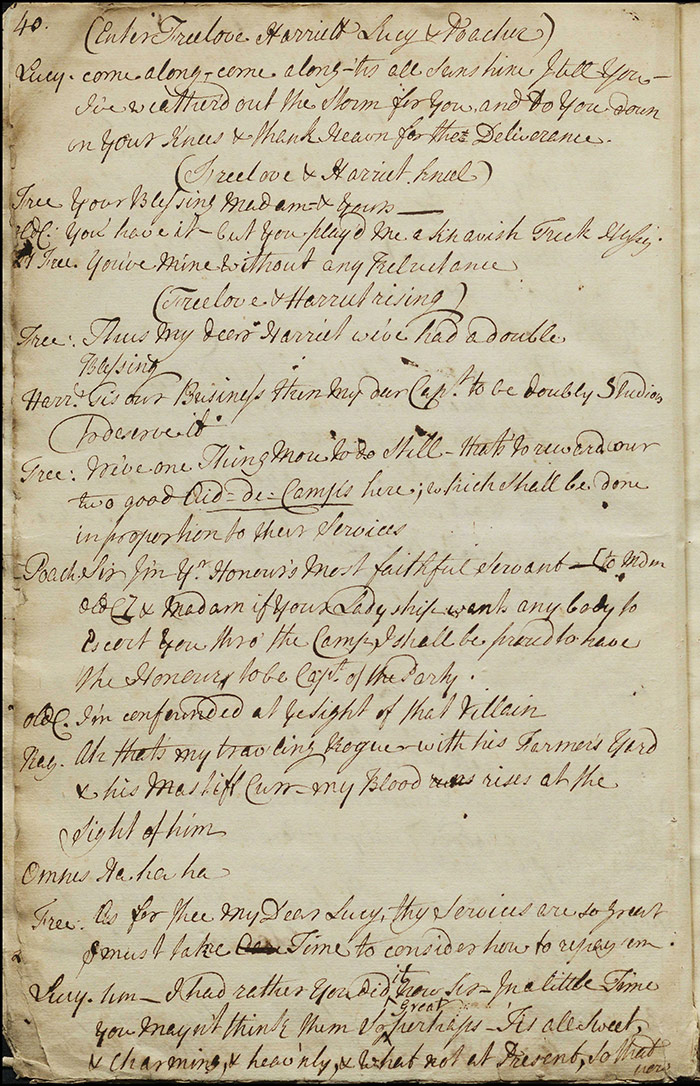

Enter Mrs Shuffle. She is peeved at having gone to Hounslow in vain but she is absolutely incensed to hear that her husband has gone off with another woman and exits. Poacher too exits leaving Freelove and Lucy alone at last. But Lucy enters to warn that Lady Freelove is arriving again. Freelove looks to Lucy again and she brings Harriet off to put a plan into execution, instructing Freelove to agree to whatever his mother demands. Enter Lady Freelove. As anticipated by Freelove, she brings up the question of marriage to Lady Sparkish’s daughter and her £7000. He asks some questions by Lady Freelove knows little of her. Enter Lucy and Harriet, disguised as Lady Sparkish and daughter. The ploy works and Lady Freelove encourages the pair to go and get married at once. Exeunt Freelove and Harriet. Enter Madam Oldcut, Rag, and Sawney. Oldcut has spotted her niece and the plot is exposed. Both mothers lambast Lucy but are mollified when they learn of each other’s wealth and blood. Lucy brings the lovers back in and all are reconciled. The play ends with a song from Lucy.

Performance, publication, and reception

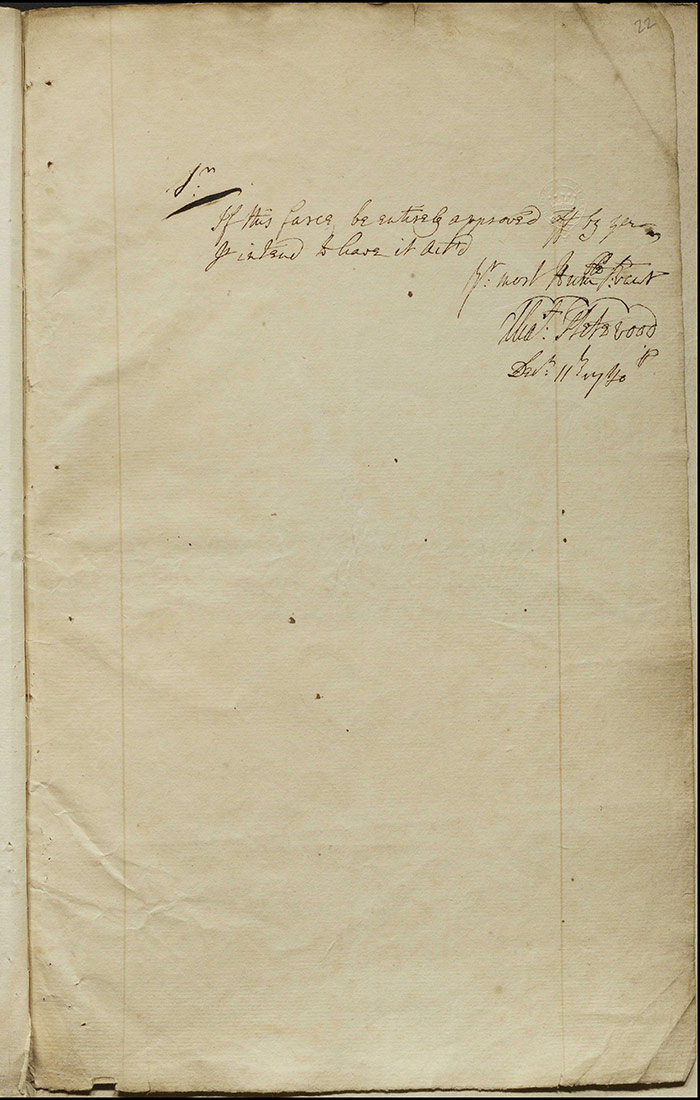

It is probable that this play was refused a licence: it was not performed nor was it ever published. There is no explicit condemnation of the piece marked on the manuscript as might be expected so there is a small possibility that the play was approved but simply deemed too controversial to stage by the manager.

Commentary

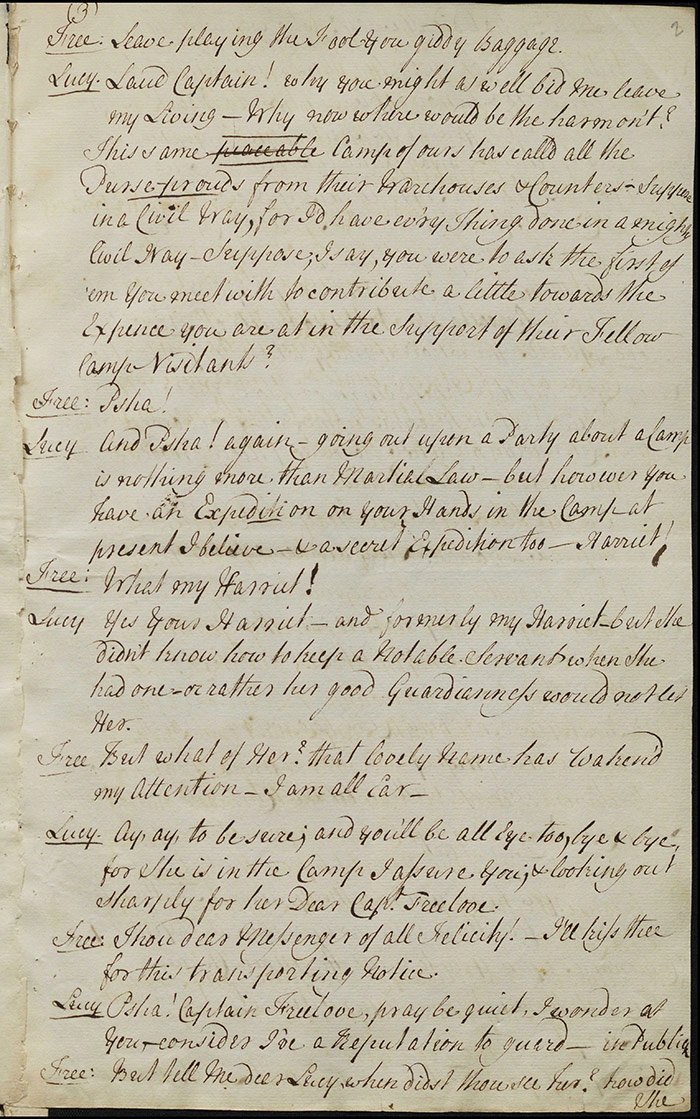

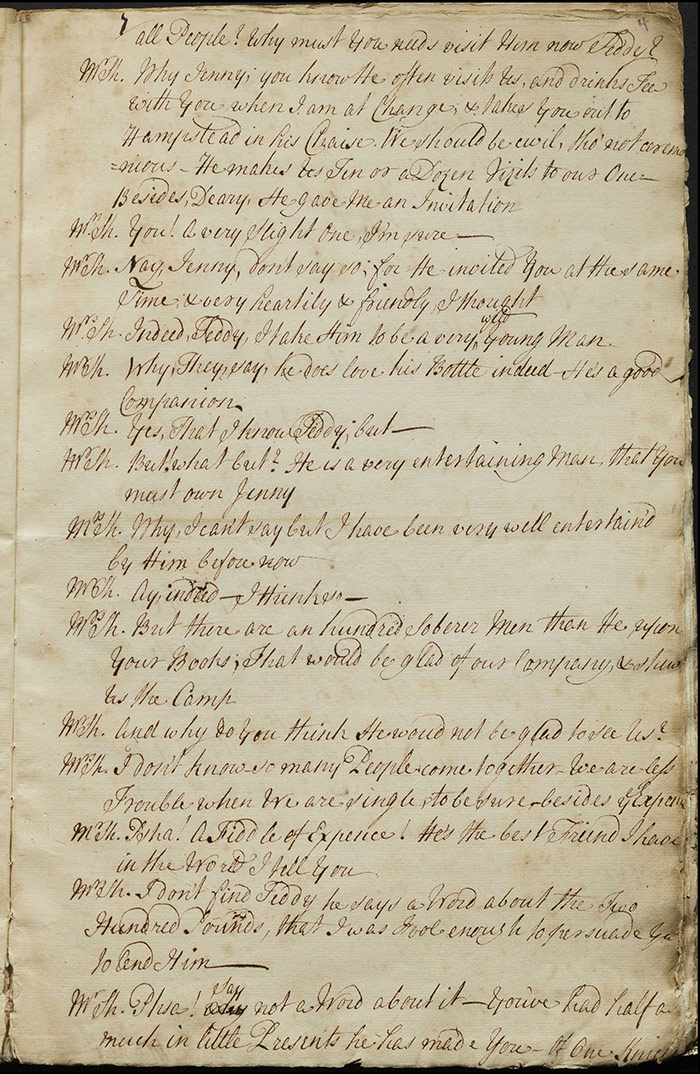

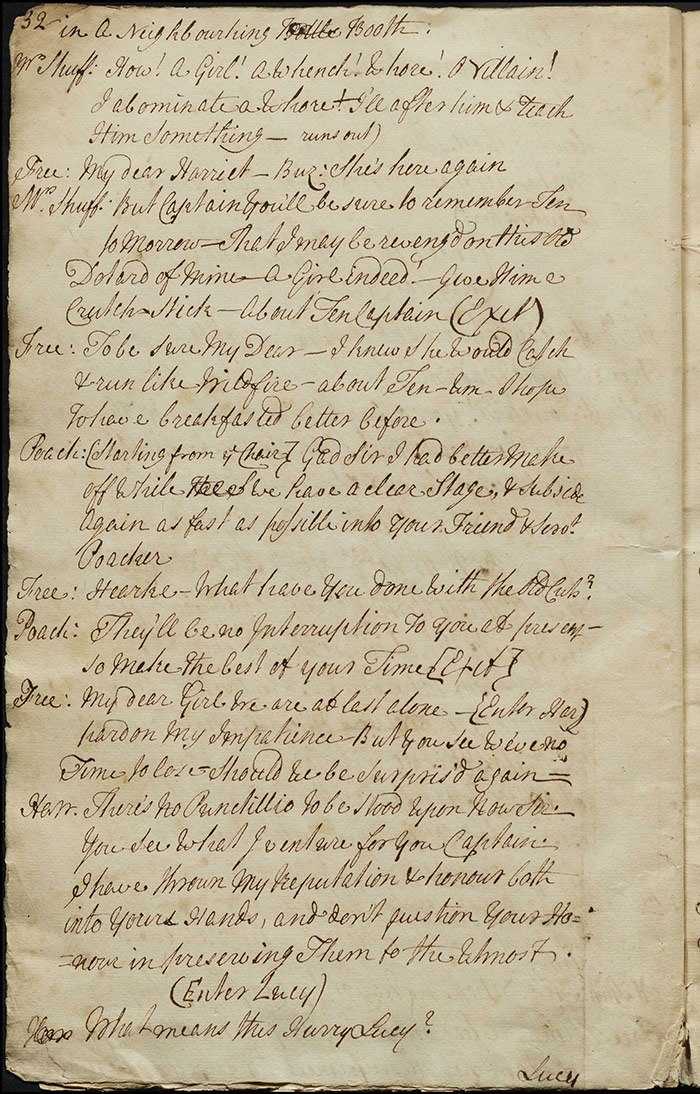

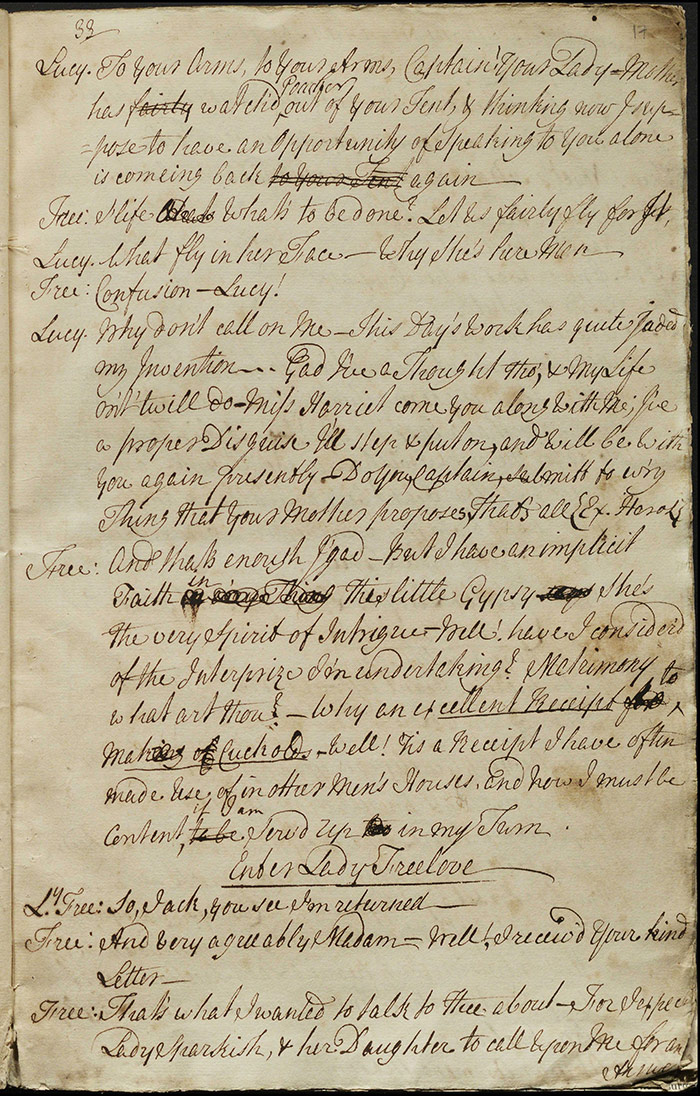

The manuscripts (LA 23) shows a number of emendations and excisions marked in pen. It is probable that there are both managerial and Examiner edits in evidence although it is difficult to distinguish one set of edits from the other. The play’s interest from a censorship perspective stems from the repeated attacks on camp culture and the effect this is represented to have on Britain’s military potency. This was a topic for which Miller had already drawn the attention of the Examiner in his earlier play The Coffee House (see Author note) but here the attack is rather more sustained. The play was performed during the War of Jenkins’s Ear (1739-1748), a Spanish-British conflict sparked by trade disputes in the Caribbean between the two countries (see also the notes for Britons Strike Home). Hence it is no surprise to find the Examiner sensitive to comments disparaging the military.

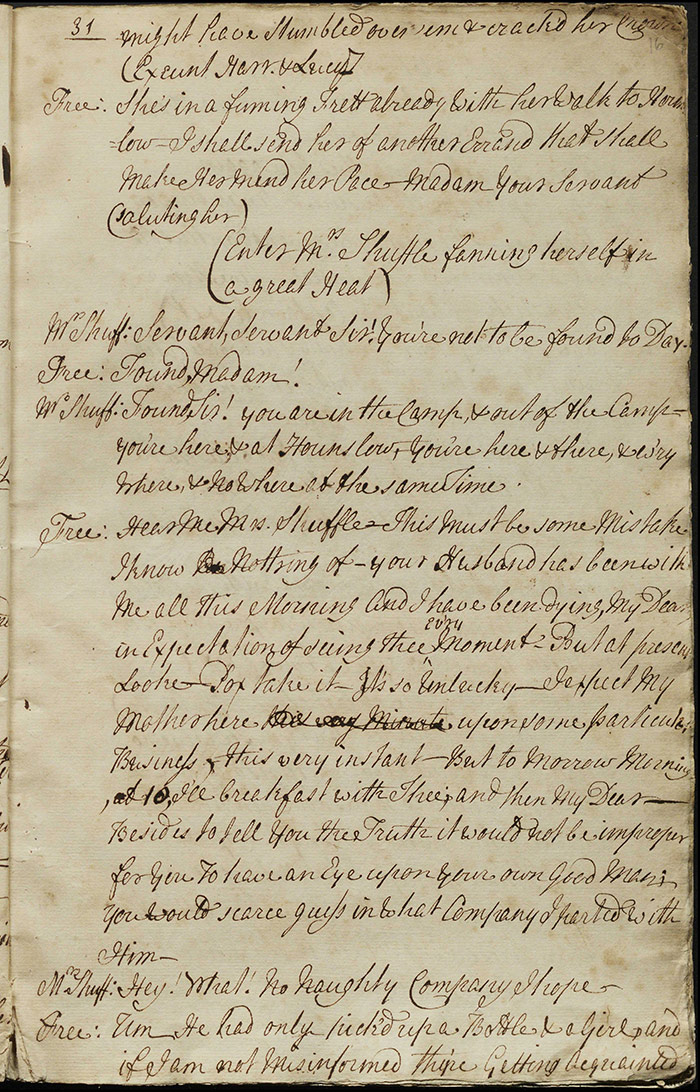

The difficulty in unpicking the various edits that can be traced on the manuscript is that there are examples where text is marked with multiple horizontal lines in the margin, examples of text underlined, examples of text scored out, and examples of text that are both underlined and scored out. It seems probably that this means at least two pens are at work, the Examiner and the manager, but who is doing what, and in what order they are doing it, is more difficult to discern.

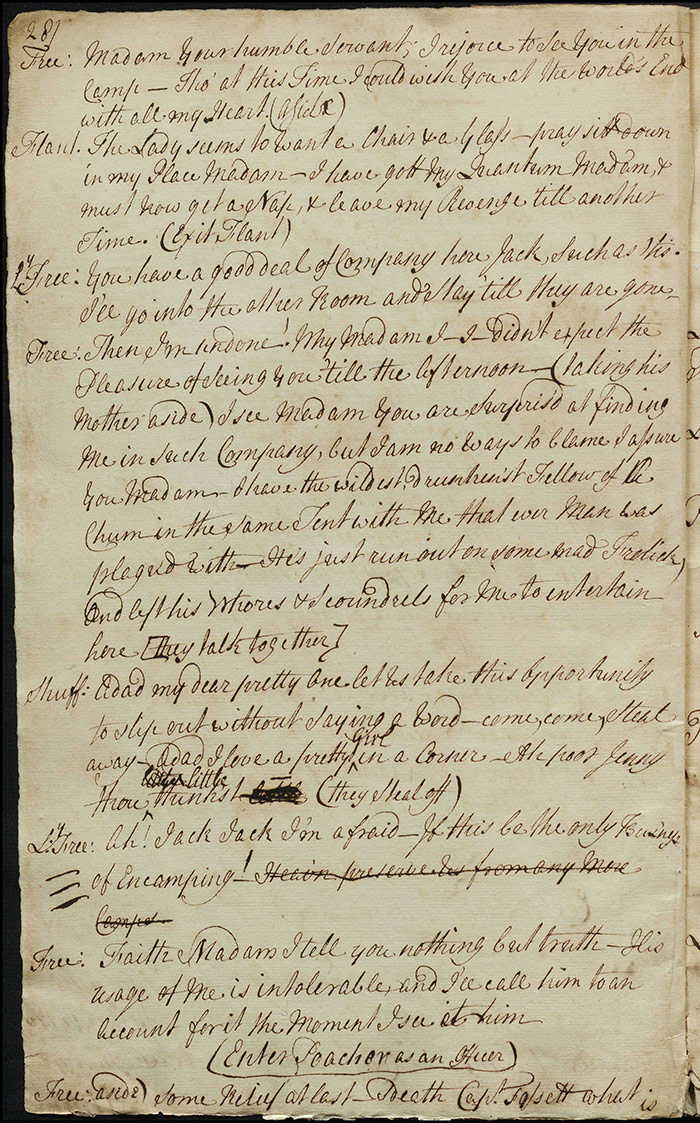

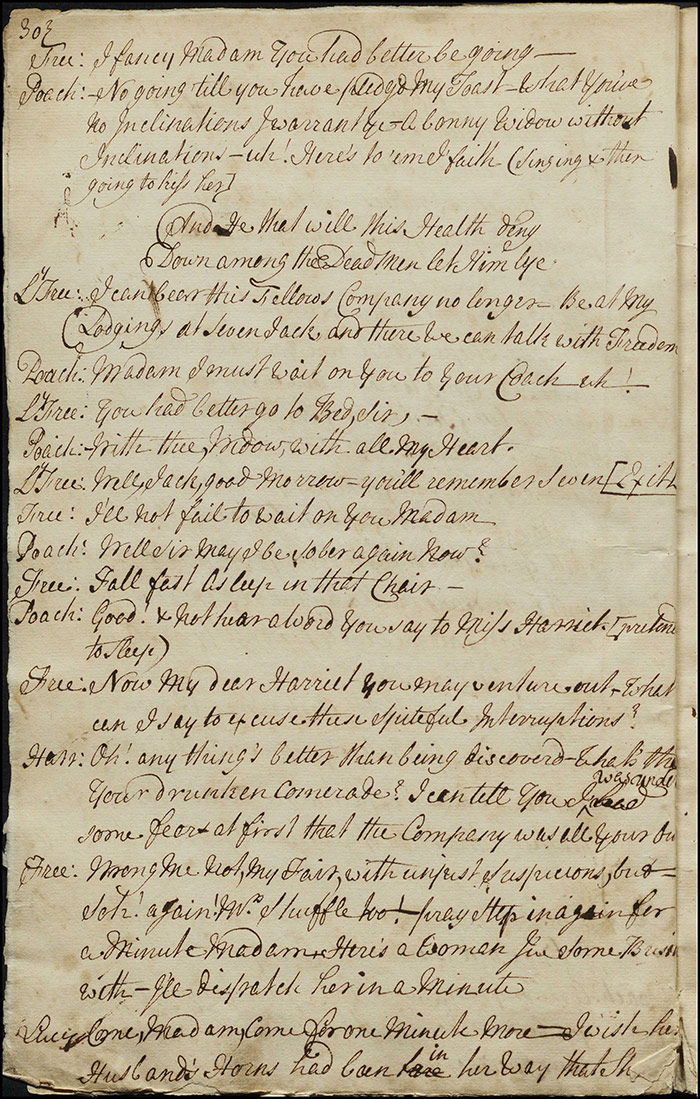

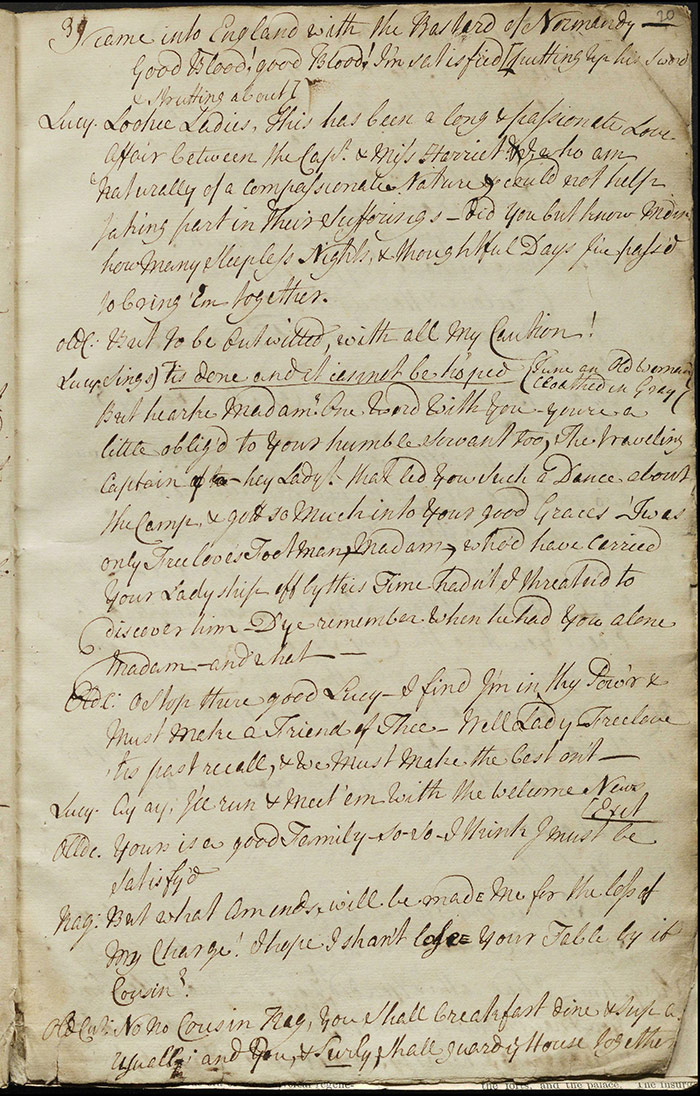

One might reasonably speculate that the Examiner marked those passages with multiple horizontal lines in the margin. If it had been the manager, it seems more likely that he would simply have struck out the text by way of editing. Marking the text in the margin seems commensurate with simply indicating such sentiments were not permissible for public performance. The first passage so marked occurs on (f.11v) where Shuffle’s comments on the absence of soldiers in the camp were clearly felt to be disparaging Britain’s readiness for conflict in the wake of attack. The following folio (f.12r) has a comment from Lucy similarly marked. In an aside to Freelove, she quips that the conquest of Harriet will be ‘the only Victory you’ll gain this Campaign’. In this example, the ‘only’ has been crossed out and ‘best’ inserted above by way of replacement. This suggests that the manager felt that this modification would appease the Examiner (i.e. soldiers could pursue sexual gratification and fight at the same time) or perhaps that the manager anticipated the objection, made the change, but that the Examiner was still not satisfied. We cannot be sure but it is helpful in suggesting that we might think of the words struck out as being by the manager’s hand. The example on (f.14v) is similar in that the text is both marked by lines in the margin and struck out: ‘Heav’n preserve us from any more Camps’.

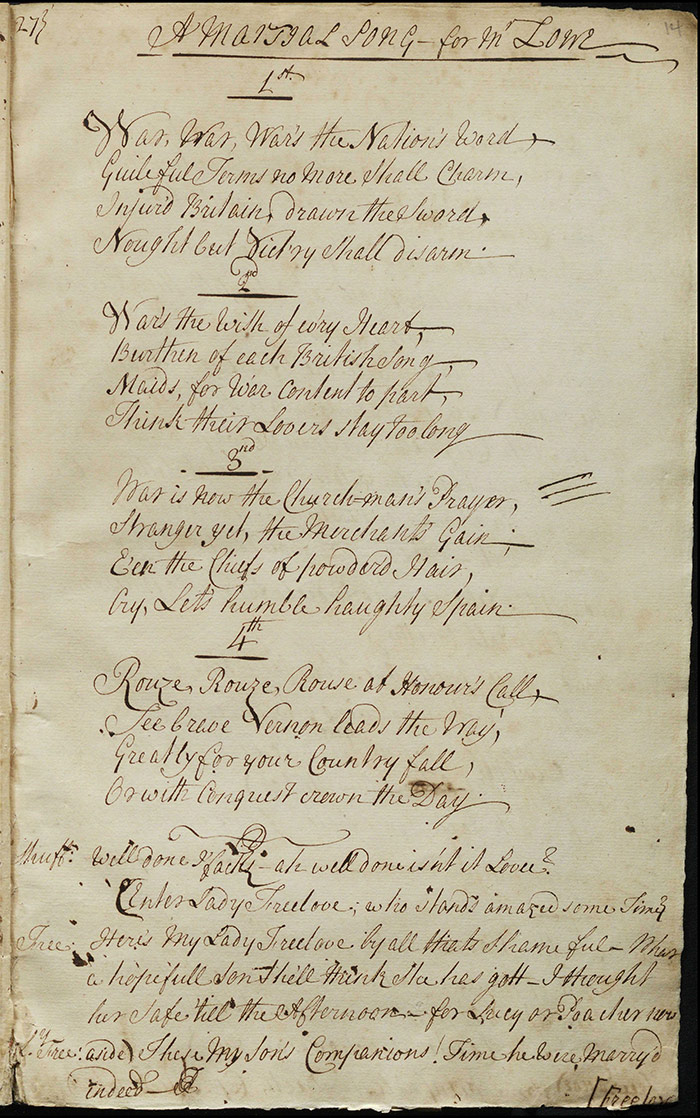

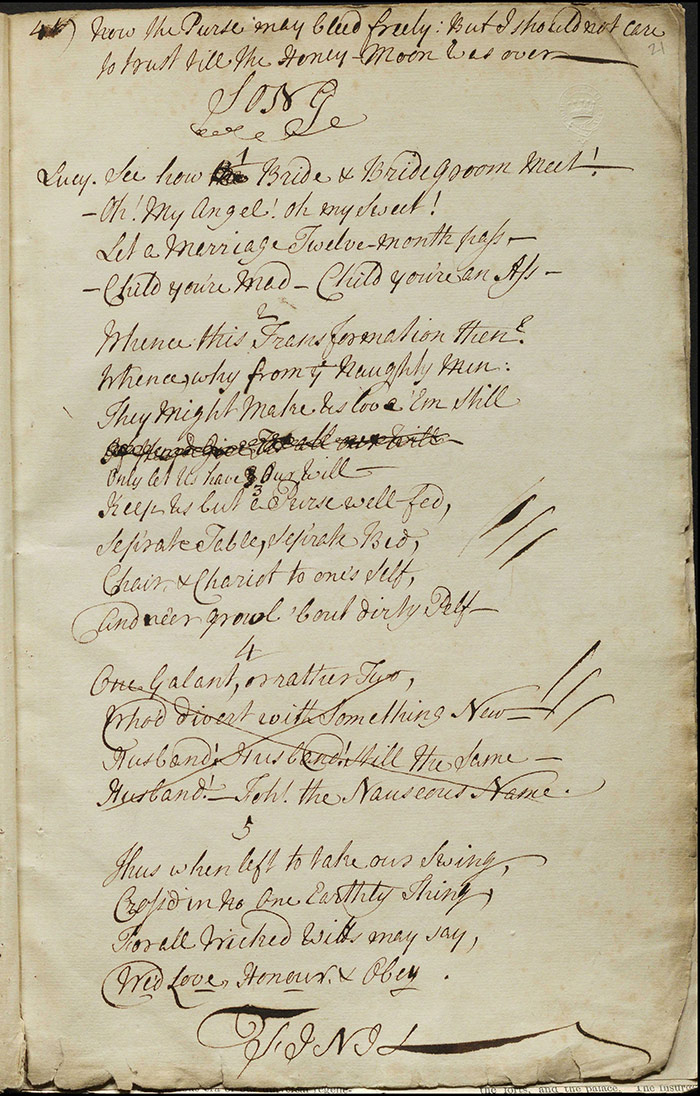

There are two further passages marked by the Examiner’s lines in the margin which occur in songs. The first are lines from a song delivered by Freelove’s corporal: ‘War is now the Church-man’s Prayer, / Stranger yet, the Merchants Gain –’ (f.14r). That war would lead to profiteering from vested interests was understandably a sentiment that would be deemed off-message by the Examiner even if it was couched in an otherwise rousing and patriotic song. The final example of what we might confidently assume to the Examiner’s intervention occurs in Lucy’s song that closes the play (f.21r). The song is a humorous reflection on the marital condition after the initial excitement has waned. Two verses were deemed unacceptable:

Keep us but a Purse well-fed,

Sep’rate Table, sep’rate Bed,

Chair & Chariot to one’s Self,

And ne’er growl ‘bout dirty Pelf

One Galant, or rather Two,

Who’d divert with something New –

Husband, Husband still the same –

Husband! – Foh! The Nauseous Name.

It is suggestive in this final example that the second verse is also scored out (with a large ‘X’ through the lines) while the first verse is left simply with the Examiner’s horizontal lines in the margin. The idea of female extra-marital sexual activity is certainly more radical than a reference to a couple leading separate lives so we might understand the hierarchy suggested here. It is possible that the distinction being drawn here might indicate that the manager was hoping to engage the Examiner on the issue. In other words, he would argue for the retention of the first verse but accepted that the second was beyond the pale. Certainly, there is evidence later in the century that managers and authors were prepared to challenge and query the decisions of Examiner so it is certainly possible that this occurred here as well.

The question of underlined passages is rather more vexed. We must acknowledge that there are a number of instances where underlining is used simply for emphasis: there are a number of such examples on (f.1v) where words such as ‘matrimony’, ‘principal’, and ‘high way’ are underlined with brief assertive marks and in sentences where such emphasis would make dramatic sense. However, there are also instances of underlining which seem to constitute editorial intervention. The French phrase ‘par tous les Diables’ is underlined with a shaky and uneven long mark, very different to those made for emphasis. It is unsurprising to see references to devils marked for omission. There is a more ambiguous example on the (f.1r) where Lucy sings the opening song and plays on the bawdy innuendo of her selling her ‘fruits’:

But, Sir, would you taste of the Fruit of my Vine?

Pray see how transparent, & tempting they shine!

When took in the morning, they set the Head right,

And cool their own Juice that was drank over Night.

The underlining here seems somewhat shaky as per ‘par tous les Diables’ and so we might be inclined to think that the play on male and alcoholic spirits is being pounced on by the Examiner. That said, we must acknowledge that it may be underlining for emphasis in order to ensure the bawdiness was understood. Another later example of the lewd mindset of soldiers is also marked for removal ‘And what’s a Soldier good for you know Madam, but for the Ladies’ (f.9v).

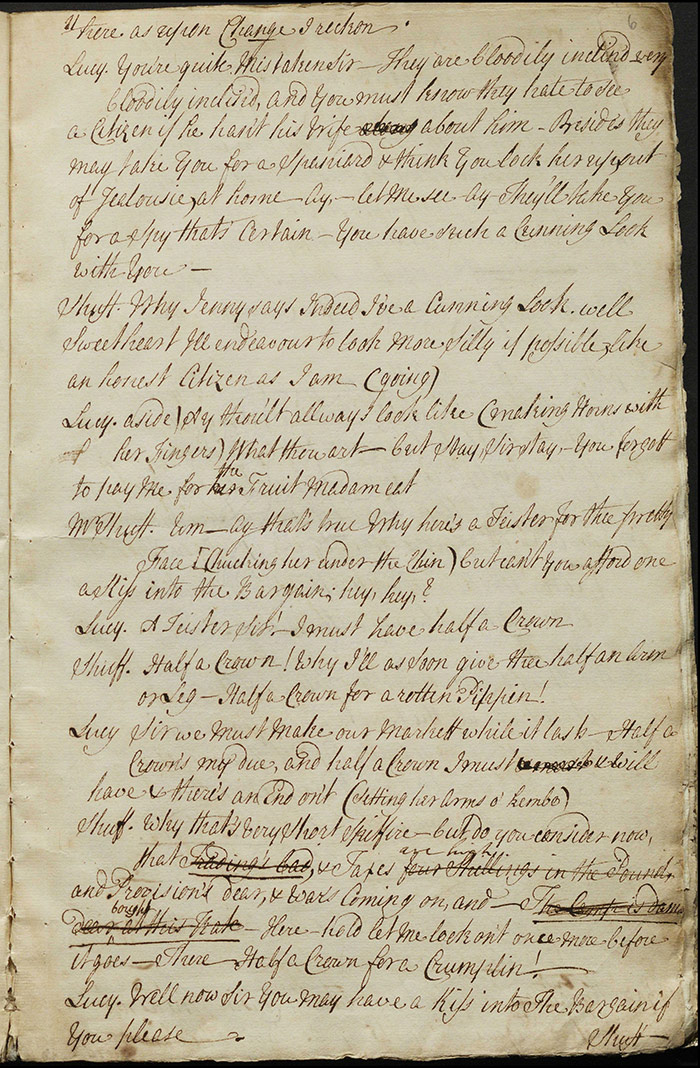

There are other examples of underlining (sometimes also struck out) which appear to be clear cases of Examiner intervention: references to ‘This same peaceable Camp’ (f.2r); the soldiers being ‘as quiet as Lambs I suppose’ (f.5v); ‘this same raree shew of a Camp’; and, a speech from Rag highlighting the theatrical nature of the camp and how this represents a degeneration from past British military glory: ‘All Shew – All Shew All Shew indeed! Ah! This isn’t Ramilies, nor Blenheim, not the Camps I have been used too’ [sic] (f.6v).

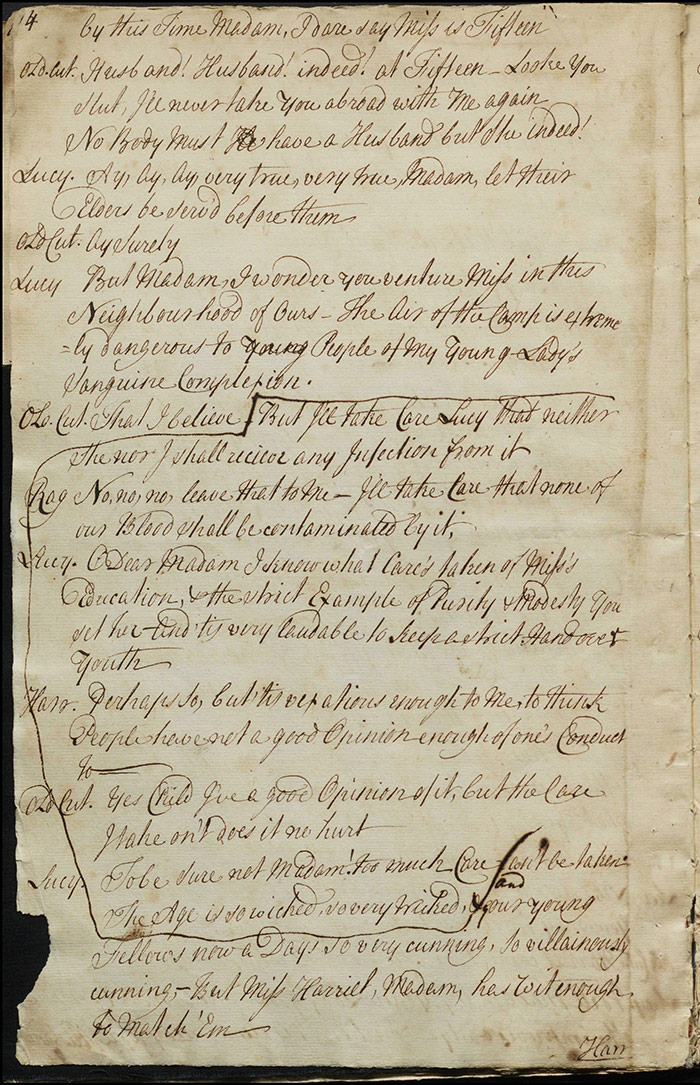

There is one quite lengthy section of dialogue where references to fears of infection from the camp, contamination, and the wickedness of the age are also marked (f.7v). In this case, the entire section is marked off from the rest of the play, rather than being struck out or underlined but this is simply because of its length.

Finally, we may also note that references to poor economic conditions in the country, implicitly linked to the war with Spain, are also marked for removal: ‘but do you consider now, that Trading’s bad, & Taxes are high four Shillings in the Pound’ [….] The Camp’s dam dear at this Rate’ (f.6r). This particular passage is worth careful scrutiny as there seems to be two hands at work (one underlining and one scoring out) with overlapping but distinctive perspectives on what could be said or not. Why, for instance, would someone believe that referencing high taxes would be ‘better’ than spelling out a precise figure?

In brief, the Examiner is exercised by any suggestion that these camps are sites of sexual promiscuity or that they represent a waning military potency. Equally, the suggestion that the camps are little more than theatrical pageantry is unwelcome.

Further reading

Theophilus Cibber and Robert Shiells, The lives of the poets of Great Britain and Ireland, 5 vols (London: R. Griffiths, 1753).

P. J. O'Brien, ‘The life and works of James Miller, 1704–1744’, PhD diss., U. Lond., 1979.

Paula O'Brien, ‘Miller, James (1704–1744)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2005 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18724, accessed 30 March 2017].

Gillian Russell, The Theatres of War: Performance, Politics, and Society, 1793-1815 (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1995).