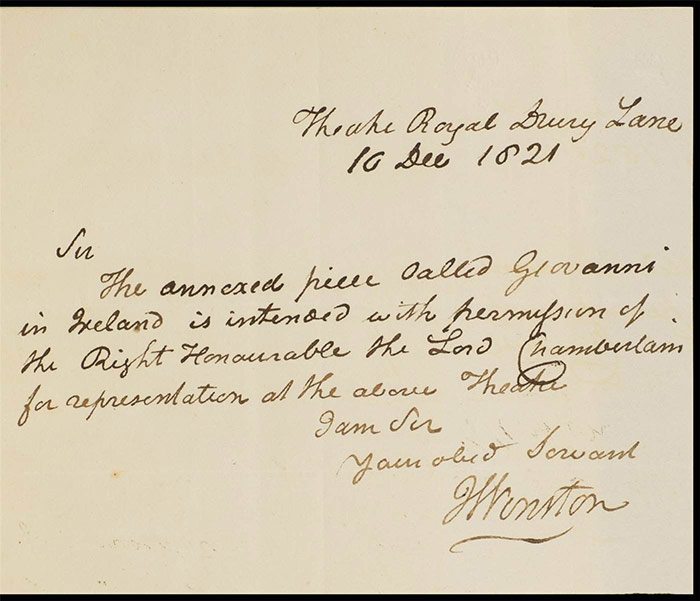

Giovanni in Ireland (1821) LA 2267

Author

William Thomas Moncrieff (1794-1857)

Born William Thomas Thomas in London he began his working life at a law firm. He wrote theatrical criticism for some London publications before meeting Robert William Elliston, then in charge of the Olympic Theatre, around 1815. He had a major success with Giovanni in London (1817) in which Madame Vestris (Lucia Elizabeth) played the main part as a breeches role. There was a distinctly erotic tinge to her performance which proved commercially successful (Moncrieff testified to the Select Committee that ‘They put a lady in it with a pair of pretty legs, and that will always draw 80l at half-price’ (Select Committee Report, 178). He regretted the scandalous elements of the piece and claimed that it was played at Drury Lane against his wishes (he appears to have had no issues with the Olympia performances). He further claimed that he was told he would have to get an injunction costing £80 to stop it which provides a useful parallel with Byron’s Marino Faliero.

He became manager of Astley’s Circus and had a significant success there with The Dandy Family (1818). He wrote for other minor theatres such as the Adelphi and the Coburg. His adaptation of Pierce Egan’s Life in London titled Tom and Jerry was performed at the Adelphi in 1821. It was an enormous, if controversial hit, and the Lord Chamberlain himself came to see it due to the concern over its morality. He then wrote under contract for Elliston of Drury Lane for three years. Giovanni in Ireland was produced then but The Cataract of the Ganges (1823) is his standout production of this period.

Moncrieff continued to write for London theatres through the 1830s with his adaptations of novels being a notable feature. These included Sam Weller (1837; Pickwick Papers), Jack Sheppard (1839), and Nicholas Nickleby (1839). Moncrieff estimated he wrote about 200 dramatic pieces over his career but only about half of these were printed. The end of his life was marked by debt, poverty and near blindness. He died in 1857.

Plot

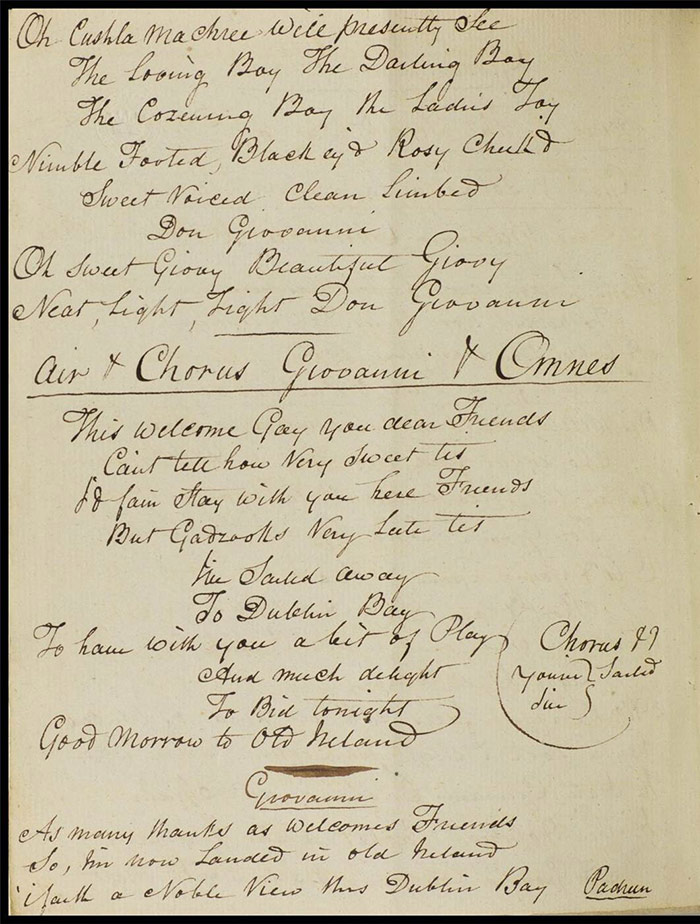

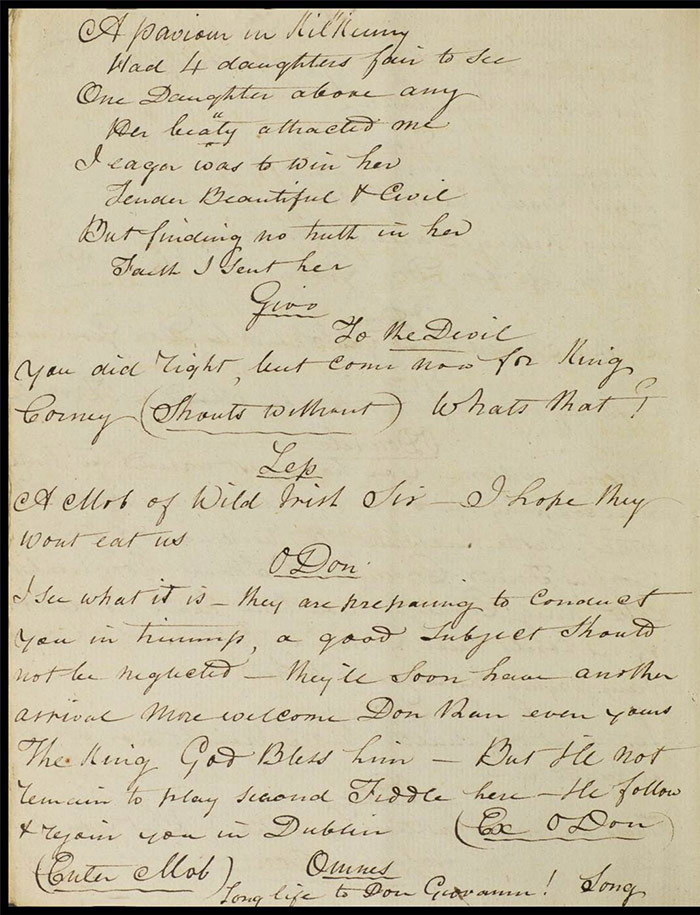

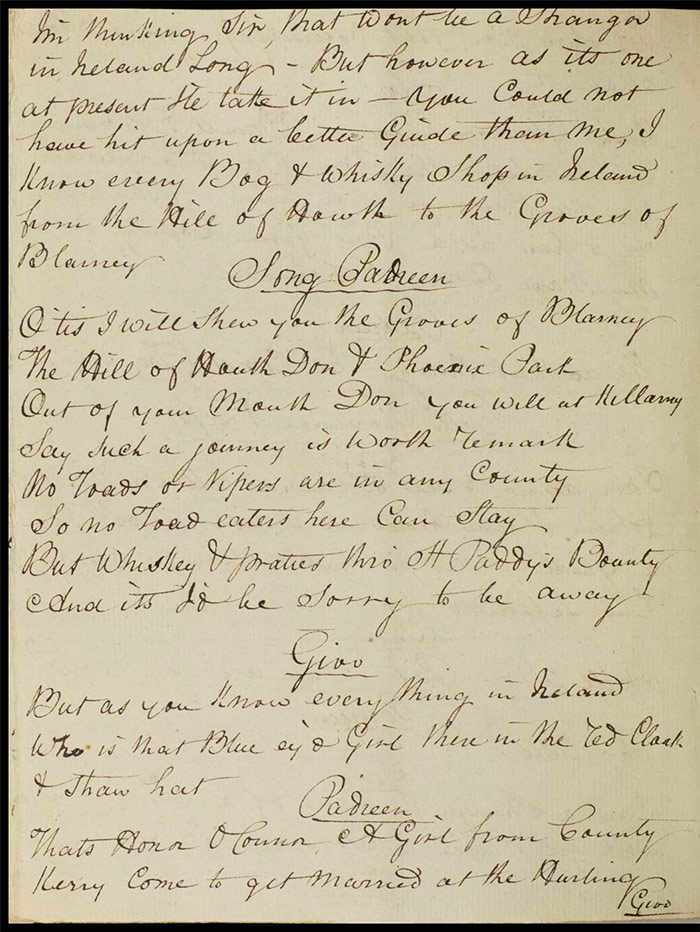

Giovanni and Leperello land at a pier in Dublin Bay from a packet ship. He has come to witness the visit of George IV. O’Donnell greets him and undertakes to bring him to Castle Rackrent to meet King Corney and his niece Glorvina. At Castle Rackrent, Glorvina laments the decline of the palace and of King Corney (f. 4r). She complains of the attentions of the taxman and church tithes to Corney. Father Joss announces the arrival of Giovanni and his party. Giovanni is smitten by Glorvina and she and O’Donnell are tasked with bringing him around Ireland.

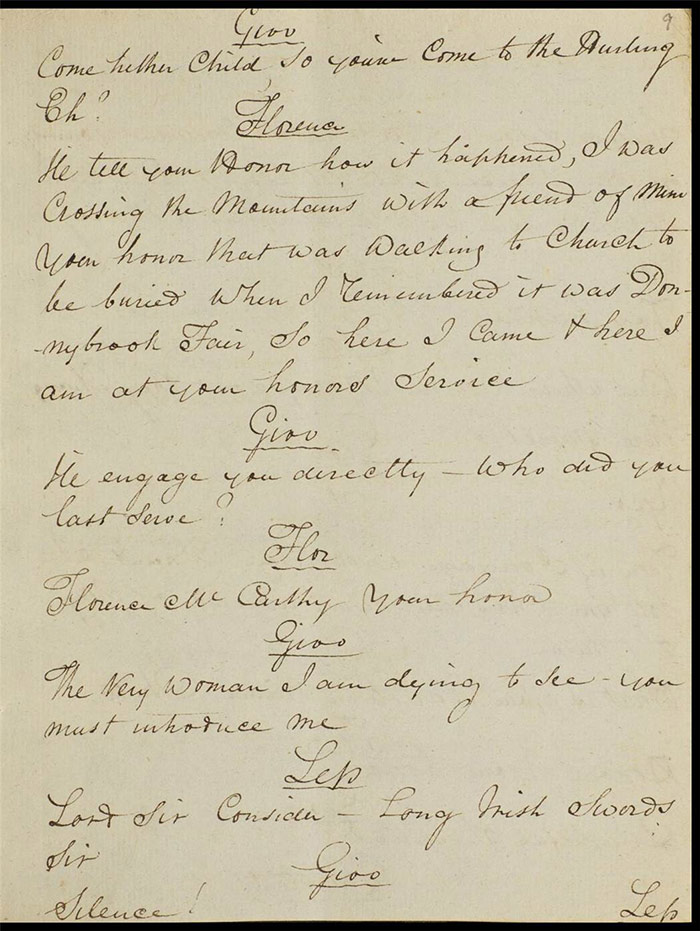

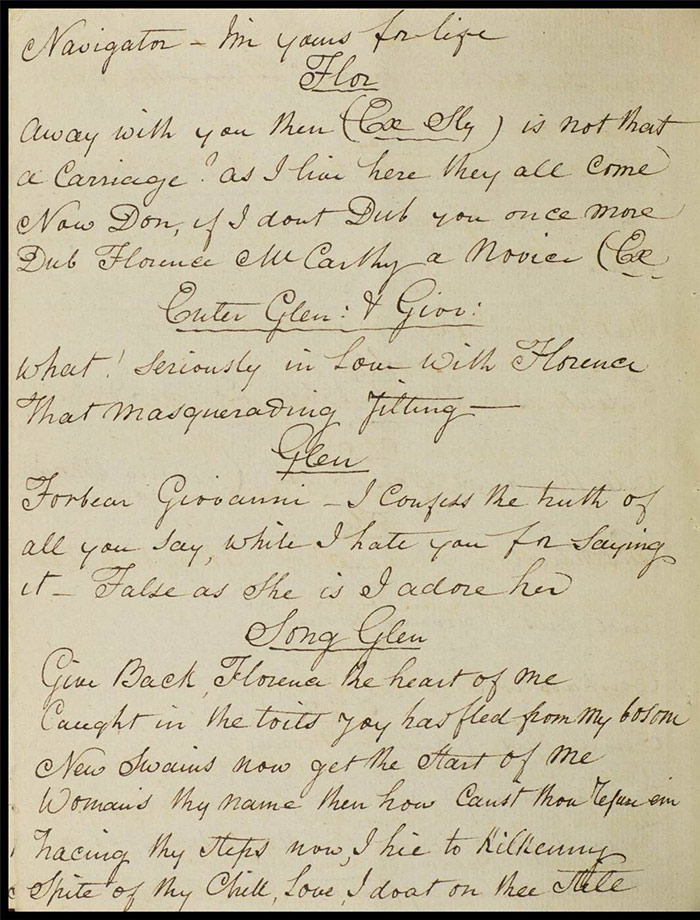

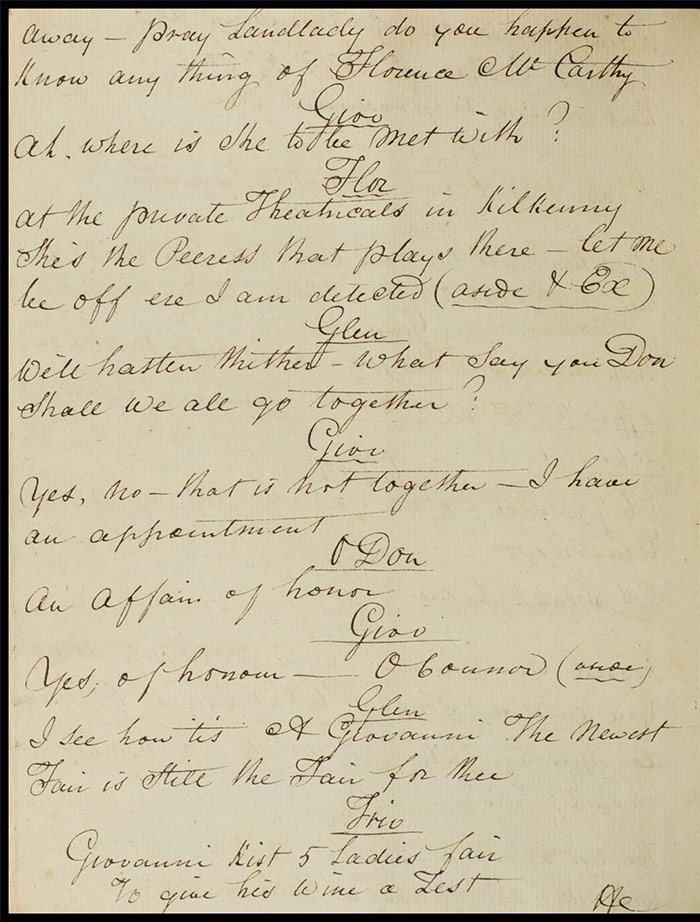

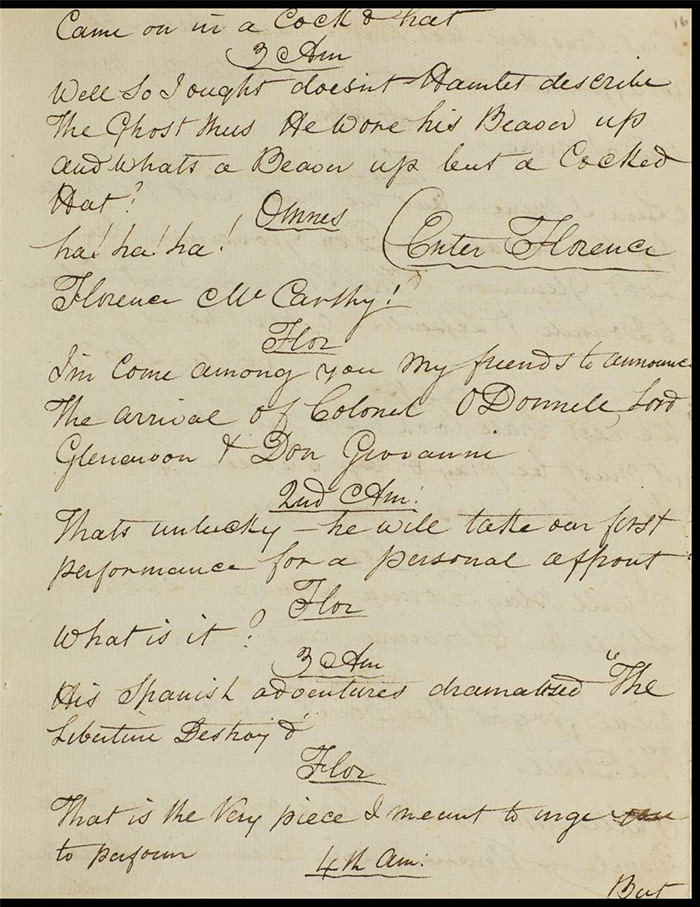

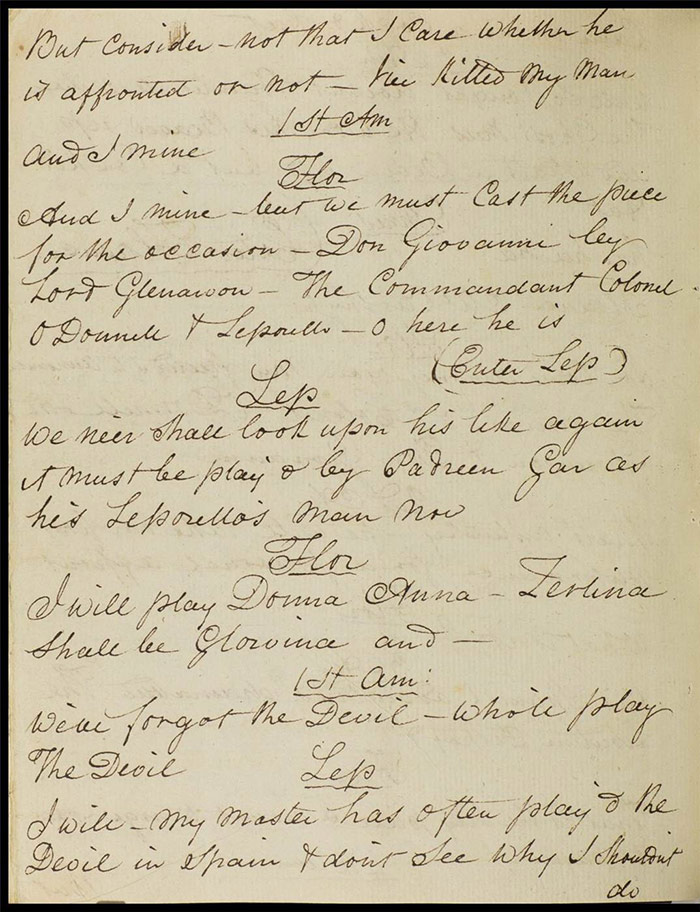

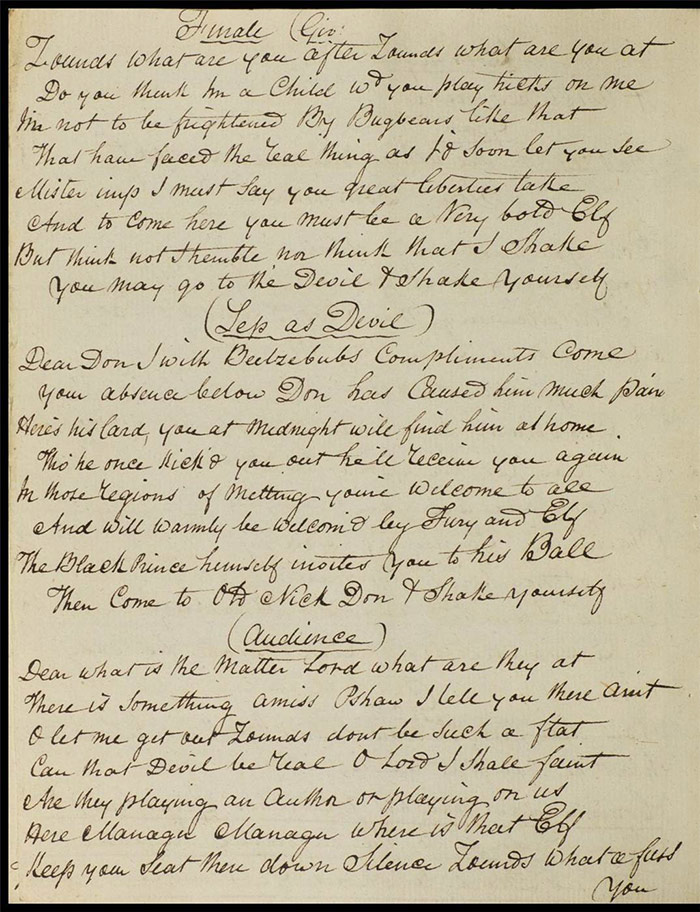

Padreen Gar is at Donnybrook Fair and is met by Florence McCarthy (f. 7v). She asks him to introduce her as Honor O’Connor from Kerry, a potential guide to Giovanni, O’Donnell and Glorvina. Giovanni and Leprello enter and look to Padreen for a guide. He introduces Florence as Honor and a marriage is proposed between her and Leprello. Florence meets Simon Sly, whisky shop owner and Glenarvon and Giovanni enter with Glenarvon in love with Florence (f. 10v). She pretends to be the landlady and tells them that Florence will appear in private theatricals in Kilkenny (where Giovanni has already engaged to meet Honor O’Connor). In a Kilkenny green room for private theatricals, Florence announces the arrival of O’Donnell, Glenarvon and Giovanni to blustering amateur actors (f.15r). They will play ‘The Libertine Destroy’d’ with Glenarvon as Giovanni, Florence as Donna Anna, Glorvina as Zerlina etc. Giovanni is in the audience as Corney watches him (f. 17r). He is so agitated he ends up jumping on stage and attacking Leparello who is playing the Devil.

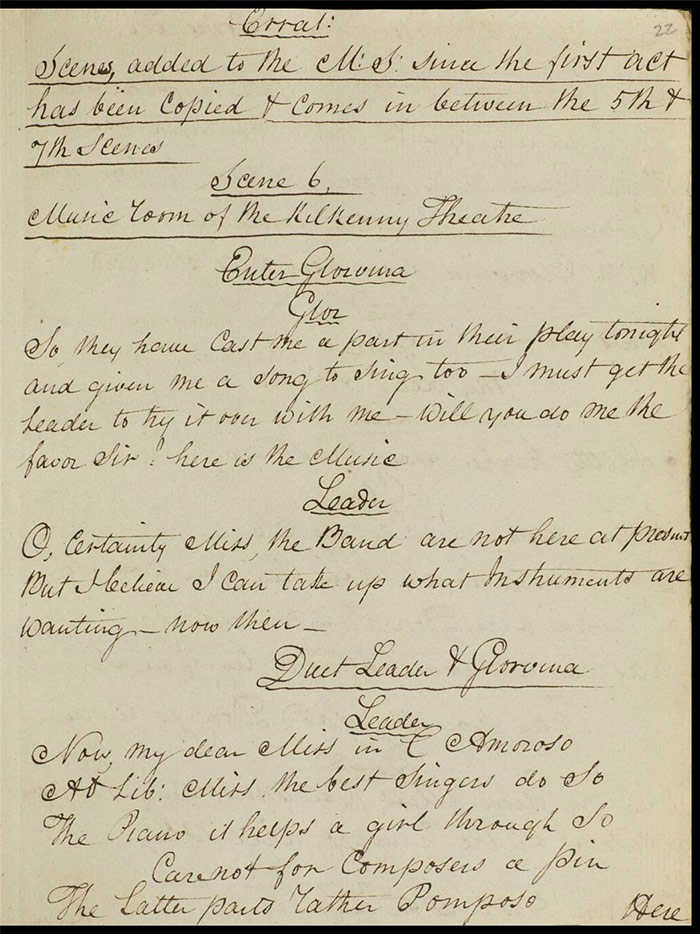

[There are errata and some additional material to Scene 6 added in (ff. 19r-23v).]

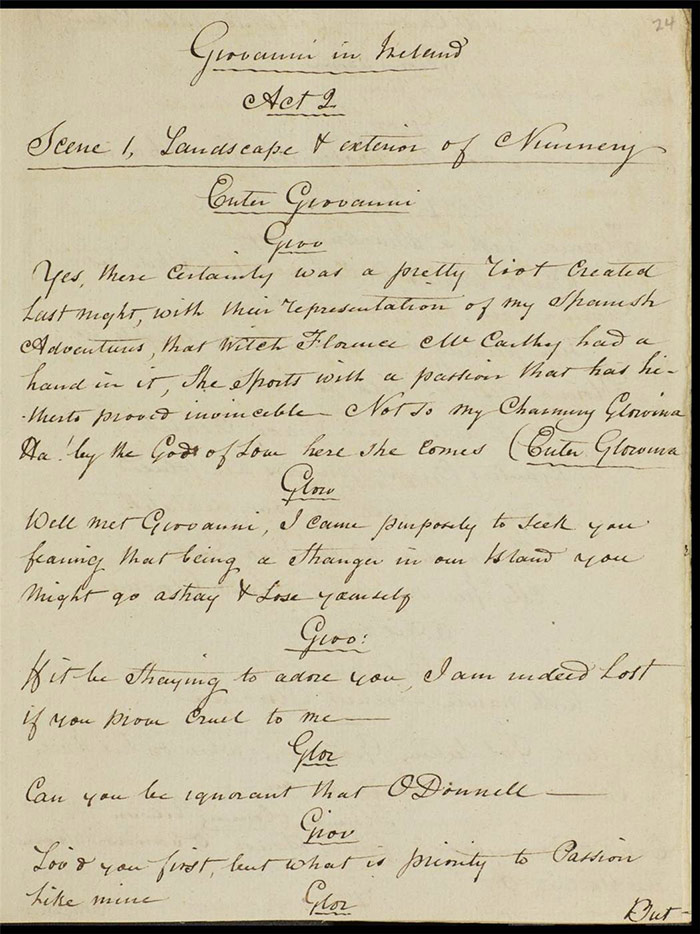

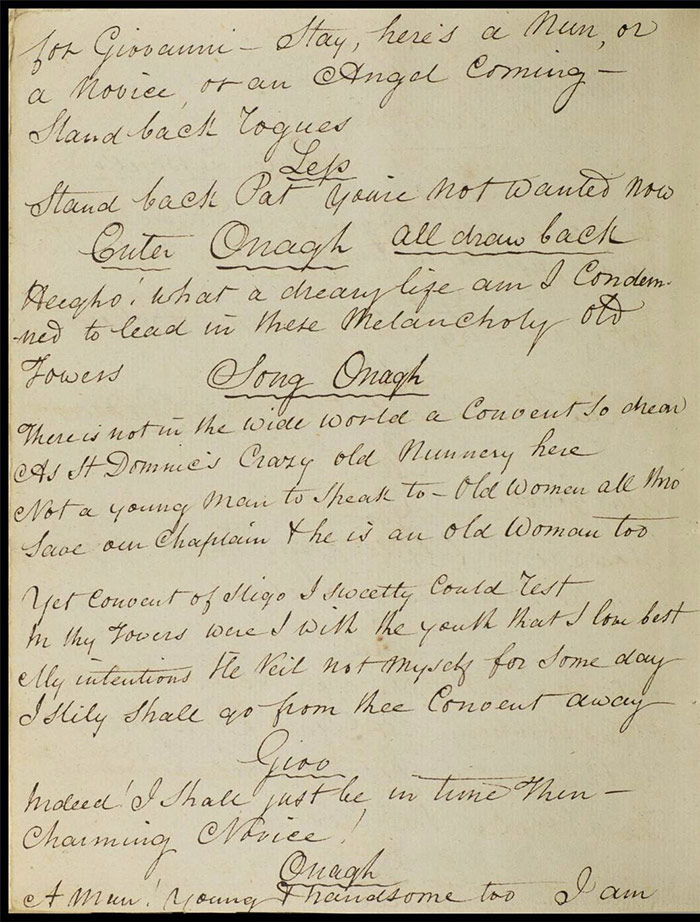

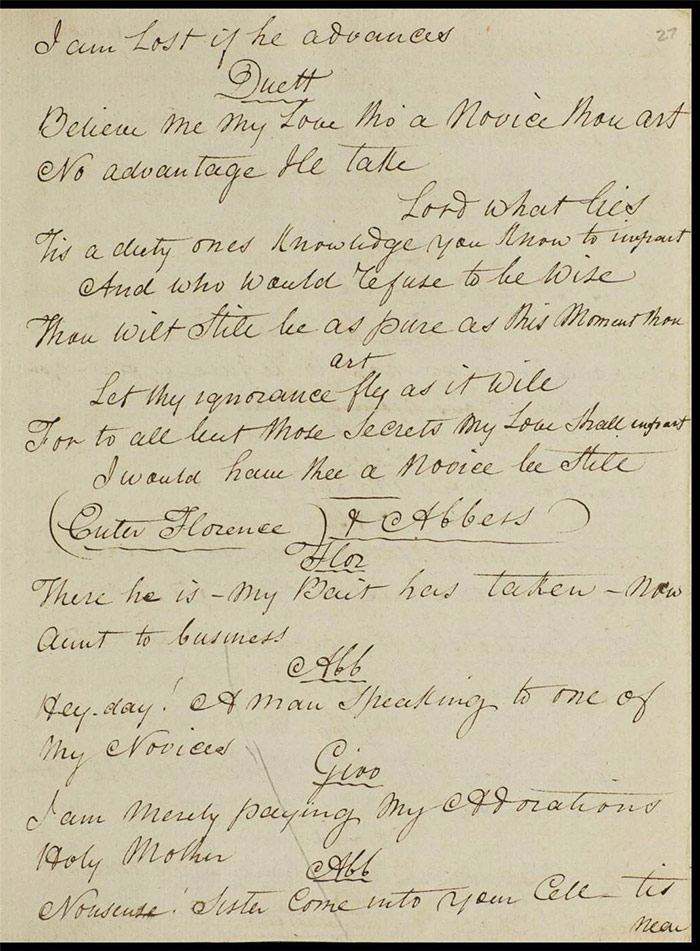

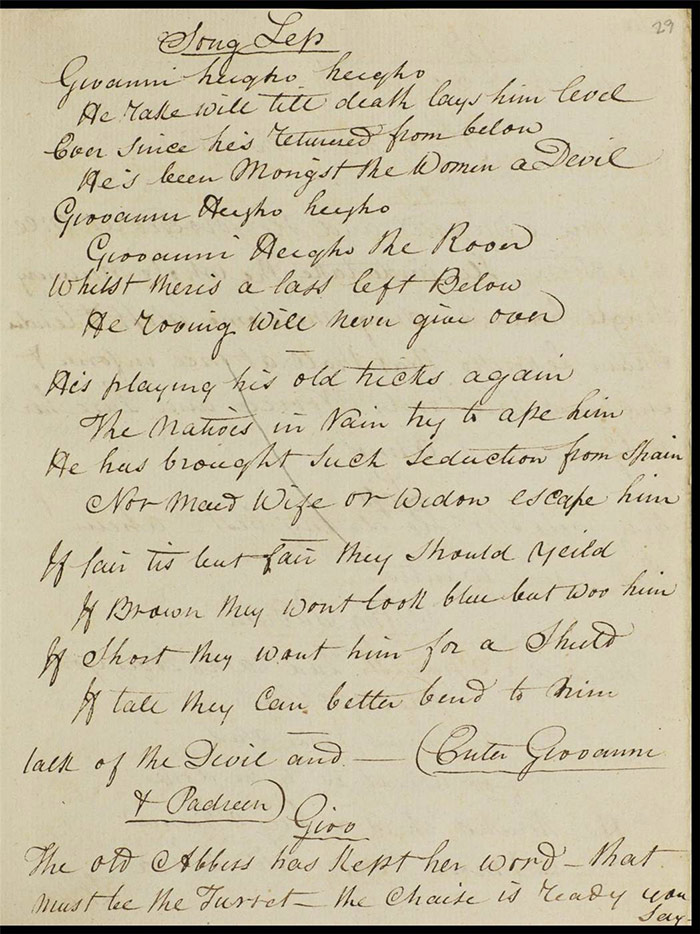

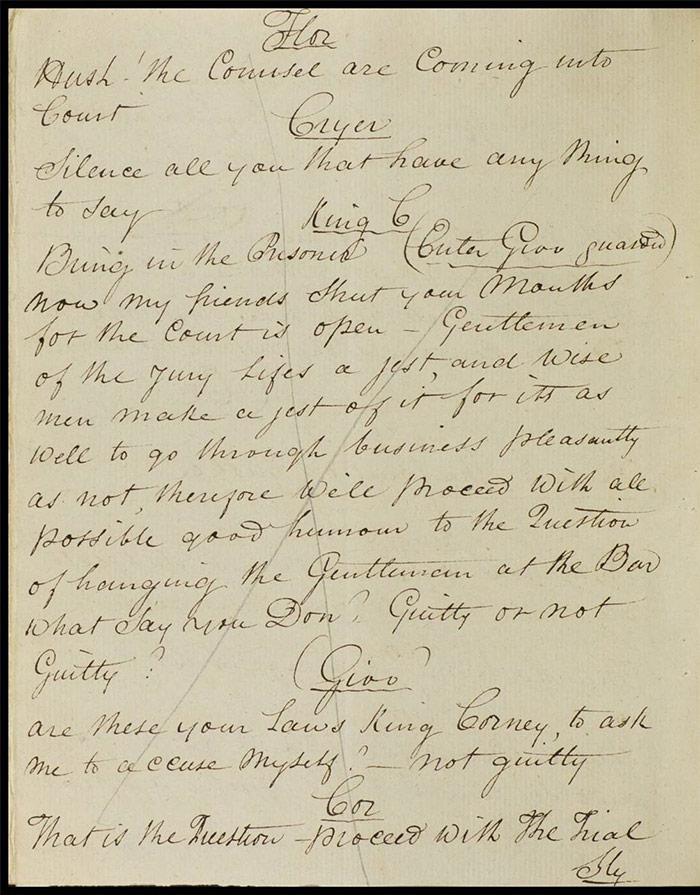

At the opening of act 2, outside a nunnery the next day, Giovanni declares his love for Glorvina but Florence interrupts in her guise as indignant Honor O’Connor (f. 24r). Giovanni says he loves all. O’Donnell and Glenarvon enter and are angered; they threaten a duel before exiting. Onagh, a novice, enters and is attracted by Giovanni but then the Abbess enters to put an end to it. But Giovanni convinces her he wants to pay his adoration to the Virgin and he gets in as the Abbess is taking instructions from Florence. Giovanni serenades Onagh who leaves her room to come down to him (f.28r). The convent is in flames and Giovanni leads Onagh and Leporello away. Florence has engineered the arrival of O’Donnell and Glenarvon (f.31v). They see Giovanni arrive with a veiled Onagh and they assume she is Florence or Glorvina; they are angry for the perceived faithlessness. Giovanni is detained by constables and Onagh is unveiled. Florence castigates O’Donnell and Glenarvon for their jealousy. They all agree to return to King Corney’s palace for Giovanni’s trial. Padreen sings the charge against Giovanni at his trial while Leporello offers a musical defence (f.35r). Giovanni also sings in his own defence but Corney sentences him to death. Corney encourages him to confess; he does so in song. The arrival of the King in Ireland inspires Corney to grant him a reprieve as long as Giovanni reforms. The conclusion sees all on stage singing patriotically together.

Act 3 ‘Consists of the Processions & ceremonies of the Installation of the Knights of St Patrick’ (f.42v)

Performance, publication, and reception

The manuscript was submitted to the Examiner’s office on 10 December 1821. There is no mention of the piece in Anna Larpent’s diary although she does note that Larpent met the Duke of Montrose in town on 13 December and that the Lord Chamberlain was ‘pleased’ (Anna Larpent’s Diary, 13 December 1821) . It is unclear whether the pair discussed Moncrieff’s drama—or indeed if it prompted the meeting—but it seems probable that they would have talked about it, given its topicality and references to a royal visit to Ireland.

The drama was first performed on 22 December 1821 at Drury Lane Theatre. The Morning Chronicle (24 December 1821) noted that the audience response was rather mixed: ‘A contest commenced at an early period of the evening which continued to the end with little intermission’. And although the reviewer felt that the applause was ‘predominate’ , the ‘malcontents were persevering to the last’. The review states that the disgruntlement was due to the excessive length of the first act and an absence of dramatic coherence between the scenes. The disapproval extended even to the scene of the king’s arrival to Dublin and the installation of the Knights of St Patrick with the writer hinting mysteriously that ‘some might attribute their [negative] reception to another cause’. Overall, the review is positive with particular applause for the music and scenography:

Nothing could be more magnificent than the Procession which advances from the platform in the pit, and the Music of the Full Band as they advance mid-way, had an effect which may even call sublime. Another splendid feature was the grandeur of the scenery. The opening scene, which represents a view of the Bay of Dublin by moonlight, and the arrival of the Holyhead packet, is as beautiful as it is correct; and the pantomimic display of the coast, scenery, and voyage from Dunleary to Milford Haven, reflects great credit on the Artists of the Theatre.

The Times (24 December 1821) was much less measured in its response, damning the play’s ‘burlesquing of royalty’ with vitriol. Leaving aside the issues with dramatic sense, the reviewer here was troubled by the politics of the representation at this time:

To speak of it as a dramatic production would be a waste of time, and would prove a want of sense. It is a mass of incongruities, not only beneath criticism, but beneath contempt. It is an outrage on sense and taste. The time at which it has been produced must not, however, pass unnoticed. If “the management” had put off the exhibition until something like tranquillity prevailed in Ireland, it would have been well, though the piece could not, at any period, be successful. But is it not insulting to Irish feeling to have this mummery of joy brought forward, when every heart shudders at the accumulation of distress and misery, and the consequent accumulation of violence and crime, by which the sister country is disfigured?

The writer has to admit to the merits of the music and the singing as well as the scenery but has further criticism of the misrepresentation of Sackville Street (Dublin’s main thoroughfare, now O’Connell Street) and the burlesquing of the king’s arrival there. For this journalist, the piece was utterly damned at its conclusion.

Nonetheless, the drama was performed again on 26 December. The Morning Chronicle (27 December) remarks that it was much altered but that this did not stem opposition; the writer is far from sanguine about its prospects. Predictably, The Times (27 December) continued its assault:

The house, to the credit of the public taste, was wretchedly attended. There was a “beggarly account of empty boxes;” and the most delicate lady might have ventured into the pit without the least apprehension of having her gown ruffled.

A notable element of this second performance was the heavy security presence that was noted by this reviewer, allegedly to shut down opposition to the piece, indeed it was management’s attempt to censor the audience’s censorship. The reviewer comments sardonically on the ‘very liberal…issue of orders [ie free tickets]’ to the police:

Many of those Bow-street officers—those excellent judges of dramatic merit—were furnished with admissions, and used their best efforts, not only to uphold the piece, but to prevent less interested spectators from expressing their unbiased opinion. “The management,” it is pretty clear, intend, if possible, to force this piece on the public

There was even a scuffle between one objector to the drama and a constable who sought to stop him. The audience member brought a complaint against the constable for tearing his shirt; details of the legal proceedings can be found in The Times (28 December). Another performance followed on 29 December and, according to The Times (31 December), the ‘reception[was] so stormy as to be paralleled only by the O[ld]. P[rice]. Row’. The noise and opposition was such that Elliston was obliged to announce that the piece would be withdrawn. However, further performances followed on 1 and 4 January before it appears to have been supplanted by its predecessor Giovanni in London with performances on 8, 21, and 24 January.

The failure of Giovanni in Ireland was a disaster for Elliston as there had been enormous expense incurred with the scenography, expenses that explain the attempt to shut down opposition. The earlier success of Giovanni in London, which gave Madame Vestris one of her greatest successes, meant that this failure was not anticipated. Despite this failure, the ‘Giovanni’ fad was to continue for a little longer: Vampire Giovanni James Robinson Planché (LA 2197; Adelphi January 1821); Moncrieff, Giovanni in Botany; or, the Libertine Transported! (LA 2281; Olympic, 16 February 1822); and, The Death of Don Giovanni; or, The Shades of Logic, Tom and Jerry (LA 2389; Olympic, 8 Dec 1823).

Theatre historians are fortunate with regard to this play as there is a rich, if one-sided, correspondence available at the University of Rochester. The correspondence—from Moncrieff to Elliston—explains that the reviewers’ complaints about the bizarre plot contortions stems partly at least from the significant rewriting that had to be done and this is corroborated in Memoirs of Robert William Elliston:

This piece was originally projected by Moncrief, but with the view of rendering it as perfect as possible, the MS. was sent to Mr. James Smith, the Hon. G. Lamb, and others, for the benefit of their suggestions. The gallifmaufry passed through half a dozen hands; and, like the knife, which one while had a new handle, and at another a new blade, its identity at last was entirely lost. (308)

Extracts from the correspondence—which is wholly available online—are included below. The extracts do not tell the full story as the letters also reveal that Moncrieff was under the strain of a court case as well as considerable financial difficulties in January as he was negotiating his piece with Elliston. We do learn, however, that Elliston seems to have been sceptical about the number of Irish characters in it as well as having misgivings about the court scene. The first version of this play was complete by January and Memoirs of Elliston reveals that it was in rehearsal in the summer when Elliston decided to expand Moncrief’s original conception:

During the time this drama was in rehearsal, the King made his visit to Ireland, and was present at the “Installation of the Knights of St. Patrick.” This coincidence was deemed fortunate; so that, at a very considerable additional expense, Elliston determined to embody, in his new piece, a representation of this imposing ceremony. (308)

By November their relationship seems to have deteriorated: Elliston seems to have accused Moncrieff of putting off the completion of Giovanni in Ireland due to his writing commitments to other theatres, a charge that Moncrieff denies. But we can see from the extracts of the correspondence below, one-sided correspondence though it might be, how invested Elliston and Moncrieff were in Giovanni in Ireland.

[Jan 1821] [University of Rochester ref: 5183]

In the first place do you plan to do anything with poor Giovanni, and can I be of any assistance – in the next place, have you any employment for me

4 January [1821] [ref: 5178]

I am ardently trying to hear from you about the Second act of “Giovanni in Ireland” may write fully by return & let me have also what M.S. you have of the opera when is Kenilworth coming out

8 Jan 1821 [ref: 5112]

In answer to your letter of remarks accompanying the 1st Act of Giovanni in Ireland” I beg leave to submit the following comments

In the first place I am excessively gratified to hear you do not intend to make a first Piece of it. It would have been highly improper and dangerous and I am of the opinion you ruin’d the success of Justice by doing so.

That the Piece wants curtailment is self Evident writing without having an opportunity of seeing what I had written (sending the portions to town as I completed them) I had no opportunity of knowing the quantity I wrote and was struck all in a heap at the voluminous appearance of the first Act. It is nevertheless advantageous you have all my ideas on the subject, undigested it is true, but a cool half hour, and a judicious pencil, soon remedies that. All the curtailments, at present made, are excellent – without exception When I have written as an author, I invariably read as a manager – that the sooner we get Giovanni into action the better – is clear. Nevertheless the first scene his arrival, views & introduction to O Donnell & McRory & invitation to Castle Rackrent cannot be done without. Neither can the Second with King Corney & Glorvina. nor yet can the third wholly - leading as it does to Glenarvon – they however may be much shortened some of the airs may be left out. the fancy matter floord a little - &c – King Corney need not be spoken with the Brogue certainly not nor yet many others though the Irish Idiom may be preserved. The Blunder about Mrs Bland I regret exceedingly yet know not how it can be remedied – The impossibility of making Padreen a Yorkshire boy you will see when you read the second act which I want down directly having two or three alterations to make Owney Sullivan can be Darby Tully McRory perhaps Mickey Donoughoo through the agency of Florina – Teague O’Higgins need not be an Irishman but merely a slang sailor. In writing an extravaganza, the most difficult of any composition for the Stage you must take along with the nicety of inventing Ludicrous situations without becoming ridiculous – or more properly – proper ridiculousness. In this as in most of the Pieces you find many things for which the Stage has no precedent. It is no use doing what has been done before only novelty will draw. The Insolvent scenes of Giovanni in London the [Morning?] and Mountebank scenes of Rochester – are their principal attractions yet who did not tremble at them at first. It is the same with my Pantomimes I make my openings complete Burlettas - and I am right though not every one does not think. I have thought it necessary to [MS torn] do many bold and out of the wa[y] [MS torn] in this Piece – the event will Justify [MS torn] will either be completely damned or be [torn MS] Twin of its London Brother – and those [I] take it are the Pieces you want not negative nine night [illeg]. The number of Irish characters is easily gotten over. I am aware the Piece is startling at first sight – but you possess courage – look at it boldly – grapple with it determinedly and I think the Result will repay you your Labor and anxiety.8 Jan 1821 [ref: 5150]

Decision and daring made Bonaparte master of the World – The Government of a family a Theatre and a Kingdom [must] be monarchical – hesitation – and [illeg] of various Counsellors must ultimately prove the bane of every^ thing Great ! You know the Latin adage “tot homines quot sententiæ” and too many alterations of any thing raised according to Plan must spoil it. The Idea of leaving out the Trial scene staggers me – when so many serious Trial scenes have appeared is it not worth while to hazard a comic one – Surely Giovanni deserves a Trial Curtail as much as you wish but pray dont leave out a scene and break through the regular chain of communication that runs through it though my piece be madness there is method in it – dont take that away or we shall be mad indeed – I send back the first act with some curtailment in addition to those you have made – Dash at the second and trust to chance make Own[y] Sullivan be Darby Tully - in disguise Mickey Donoughoo McRory – by same rule.

8 Jan 1821 [ref: 5160]

do whatever you like with the Piece cut as much as you wish, but Mangle as little as you can - you are aware only extreme want of money would make me seek my chance for so little as £60 [Offers to sell the copyright of Giovanni in Ireland including the songs for this amount; continues by making some scenographical hints]

13 Jan 1821 [ref: 5173]

If you have curtailed Giovanni of half his fair proportions – metamorphosed Padreen into an Yorkshire boy &c &c &c. I know not what to think of his success in Public – but n’importe the Piece is yours and you are authorized in mangling it […] Heaven grant it may prove half as successful altered as I think it would unaltered.

7 Nov 1821 [ref: 5020]

In reply to your very harsh Letter of last night - I must beg to say had I patch’d up the ‘disjecta membra’ of ‘Giovanni’ as given to me after the labors of Messrs Smith & Co instead of resolutely sitting down to rewrite in a measure the whole of it you might with some justice have accused me of ingratitude dishonesty &C towards the management – but knowing the immense stake you were playing I was determined to render the Piece as certain as possible the Tale you must be aware was as tedious to me as one thrice told could be, the endless & perplexing maze of alterations I had to wander through, by no means rendered the task any more pleasant or facile – I have been a fortnight getting the Piece in the state you now have it and however vexatious the necessary delay of a day or two may have been – you had much better experience it than bring before the Public the crude tedious and improbable farrago I found my improvers had left the piece – The second act you will see I have entirely rewritten

Commentary

The manuscript (LA 2217) shows a number of excisions marked mostly in pencil but with some in pen. We cannot be certain as to whom is responsible for these interventions, perhaps particularly so in this case, given the diverse authorship of the piece. It seems probable that Larpent made some of them. It is clear from the newspaper reviews that the piece was very provocative to many in the audience. Given the parallels between Giovanni’s trip to Ireland and that of George IV in the same year, this ‘burlesquing of royalty’ as the journalist for The Times put it, was sure to attract censorial attention. The contextual issues need to be flagged to understand the cuts that were made.

George IV landed in Ireland on 12 August 1821 less than a month after his coronation. It was the first peacetime visit of a British monarch to Ireland. It was also his birthday and he was reported to have been rather drunk when he arrived. Nonetheless, he was warmly welcomed, not least as he brought some 15 hogsheads of beer for the locals with him. He spent a number of weeks in Ireland before returning home. As The Times review cited above noted, the volatility in Ireland with regard to Catholic Emancipation also needs to be considered.

George IV’s trip to Ireland also came immediately after the death of his wife, Queen Caroline, on 7 August 1821. Relations between the royal couple were vitriolic in nature and she had been refused entry to the coronation at bayonet point in July. The same day she fell ill. There was considerable public agitation at her funeral procession which passed through London – two people died – before her corpse went home to Brunswick. There was even a rumour that she had been poisoned. The elaborate writing of the piece, the cuts made to it, and its volatile reception by the public all suggest the play should be understood in the context of the unfortunate public optics of George IV enjoying himself in Ireland before his wife was even buried.

Finally, Giovanni in London (1817) to which this piece is a sequel was also a contentious dramatic event. Giving evidence at the Select Committee on Dramatic Literature in 1832, Moncrieff expressed his surprise that Giovanni in London play was performed at Drury Lane as he claimed it was only suitable for the minor theatres. He also gave evidence that he had consulted a lawyer to explore getting an injunction, as Byron had with Elliston’s staging of Marino Falieri. Finally, he claimed to have been ‘astonished’ that it had been given a licence (Select Committee, 175-177).

The most interesting excisions in the play are related to Queen Caroline. Giovanni’s seemingly chivalrous reference to Glorvina as a ‘Queen (f.6r) is marked for removal with a pencil. On the same folio, his Irish companion O’Donnell has a song listing all the places Giovanni should visit; it concludes ‘Kilbride too will just suit Giovanni / Kilpatrick Kilmanagh Kilmore / With my whack’. There is a penned ‘X’ in both margins of the ‘Kilbride’ line and the word itself been struck through in pen and pencil, and underlined in pencil. Kilbride is a bona fide village in Co. Wicklow but the allusion to Caroline’s recent death seems certain. This is followed up shortly afterwards by a group medley which ends:

Here’s to poor miss Con – Here’s to squalling Fanny

They are dead & Gone You’re in luck Giovanni

If you want a Toast to glad you now you’re Mellow

Here’s Creations boast Honest Leporello

Here’s to – Let me see – I think I’d best be giving

Our dead Loves memory, & Health to all the living. (f.7r)

This entire stanza is marked with a wavy penciled line in the margin and the phrases ‘They are dead & Gone’ and ‘Our dead Loves memory’ are also underlined. There are no pen marks, however, which suggests these references were more furtive than ‘Kilbride’. The ‘poor miss Con’ may help us connect this passage to an exchange between Giovanni and Florence McCarthy later on:

Giovanni: I dare say you were very handsome once. You must have been, for you are Comely still – I like an old woman

Florence: They are all the fashion

Giovanni: Yes, in high life. (f.13r)

During George IV’s sojourn in Ireland, he continued his quite public affair with Elizabeth, Lady Conyngham, who was in her early fifties. The ‘miss Con’ reference then seems quite explicit. There are two wavy penciled lines in the margin and the final phrase is also heavily scrubbed out with pencil.

The most substantive cut to the drama occurs in the final closing trial scene. There are substantive cuts on (ff. 35r-36v), (f. 37r) and these all relate to those passages which are the richest in legal language and imagery. The association of Giovanni with legal proceedings proved too uncomfortable for the Examiner’s sensibilities; the correspondence cited above indicates that Elliston anticipated such objections.

Other minor cuts relate to taxes and church tithes (f.4v) and sexual suggestiveness on the part of Giovanni (f.27rv) and (f.29r).

Further reading

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library, HM 31201 vol. 11, 273r.

Select Committee on Dramatic Literature (London: House of Commons, 1832), pp. 175, 178.

[available through the HathiTrust website]

George Raymond, Memoirs of Robert Elliston, comedian (London: J. Mortimer, 1845), pp. 307-9

[available through the HathiTrust website]

John Russell Stephens, ‘Moncrieff, William Gibbs Thomas [formerly William Thomas Thomas] (1794–1857)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18951, accessed 20 March 2019]

William Thomas Moncrieff Papers, D.15, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation; River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester.

[available to consult here: https://digitalcollections.lib.rochester.edu/ur/william-thomas-moncrieff-papers]