Tom and Jerry; or, Life in London (1821) LA 2262

Author

William Thomas Moncrieff (1794-1857)

Born William Thomas Thomas in London he began his working life at a law firm. He wrote theatrical criticism for some London publications before meeting Robert William Elliston, then in charge of the Olympic Theatre, around 1815. He had a major success with Giovanni in London (1817) in which Madame Vestris (Lucia Elizabeth) played the main part as a breeches role. There was a distinctly erotic tinge to her performance which proved commercially successful (Moncrieff testified to the Select Committee that ‘They put a lady in it with a pair of pretty legs, and that will always draw 80l at half-price’ (Select Committee Report, 178). He regretted the scandalous elements of the piece and claimed that it was played at Drury Lane against his wishes (he appears to have had no issues with the Olympia performances). He further claimed that he was told he would have to get an injunction costing £80 to stop it which provides a useful parallel with Byron’s Marino Faliero.

He became manager of Astley’s Circus and had a significant success there with The Dandy Family (1818). He wrote for other minor theatres such as the Adelphi and the Coburg. His adaptation of Pierce Egan’s Life in London titled Tom and Jerry was performed at the Adelphi in 1821. It was an enormous, if controversial hit, and the Lord Chamberlain himself came to see it due to the concern over its morality. He then wrote under contract for Elliston of Drury Lane for three years. Giovanni in Ireland was produced then but The Cataract of the Ganges (1823) is his standout production of this period.

Moncrieff continued to write for London theatres through the 1830s with his adaptations of novels being a notable feature. These included Sam Weller (1837; Pickwick Papers), Jack Sheppard (1839), and Nicholas Nickleby (1839). Moncrieff estimated he wrote about 200 dramatic pieces over his career but only about half of these were printed. The end of his life was marked by debt, poverty and near blindness. He died in 1857.

Plot

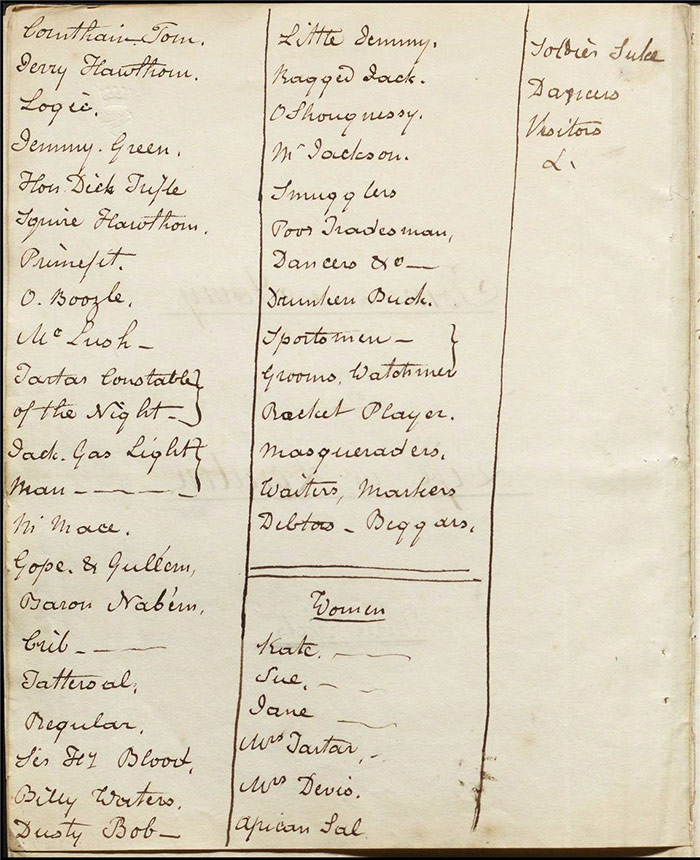

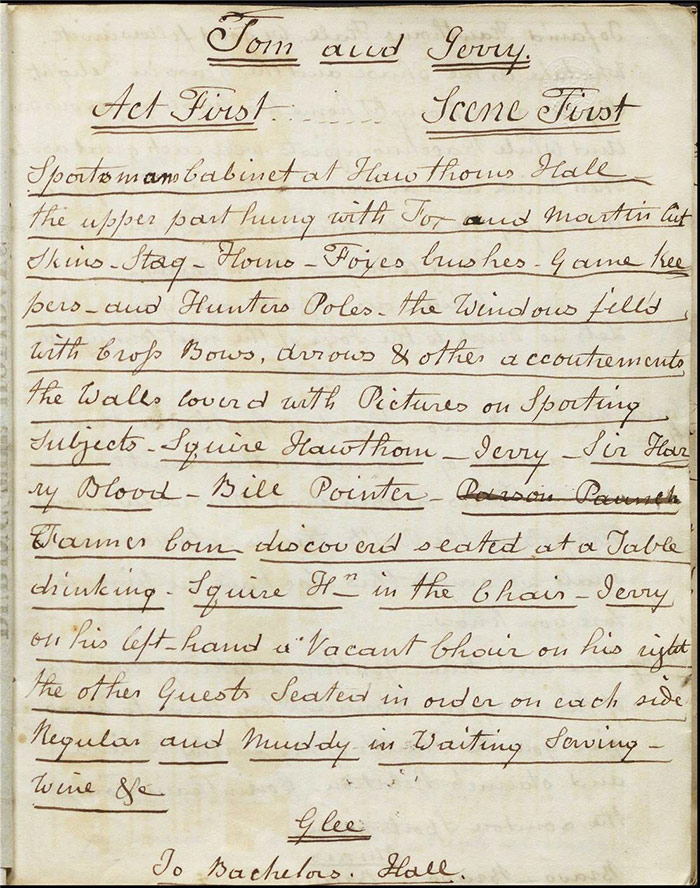

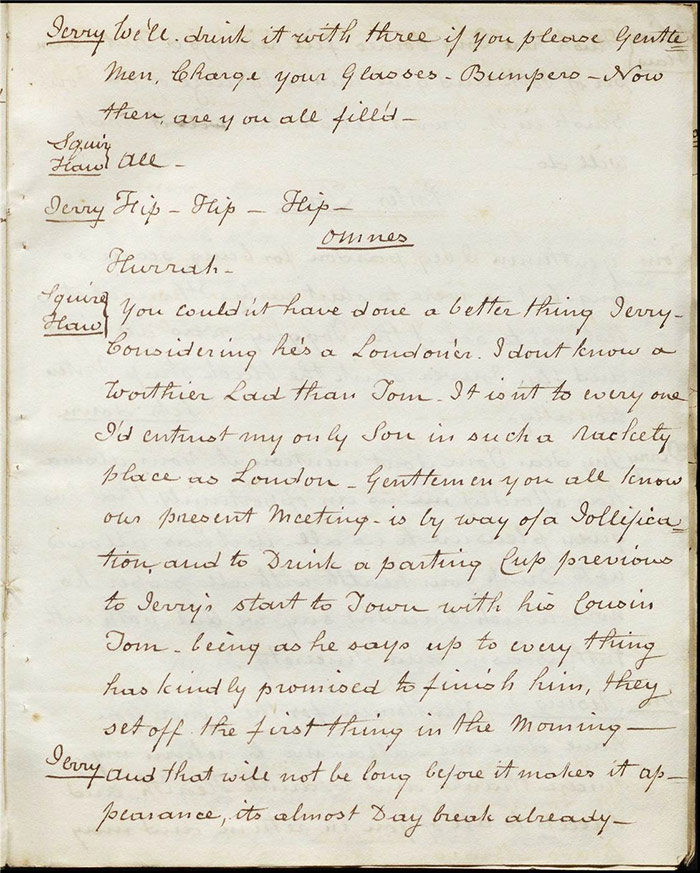

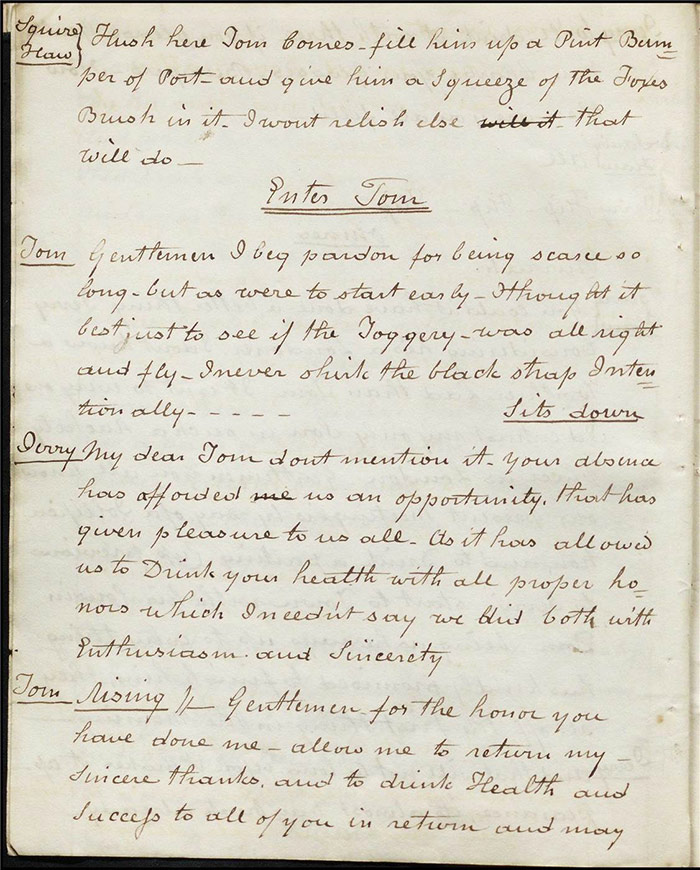

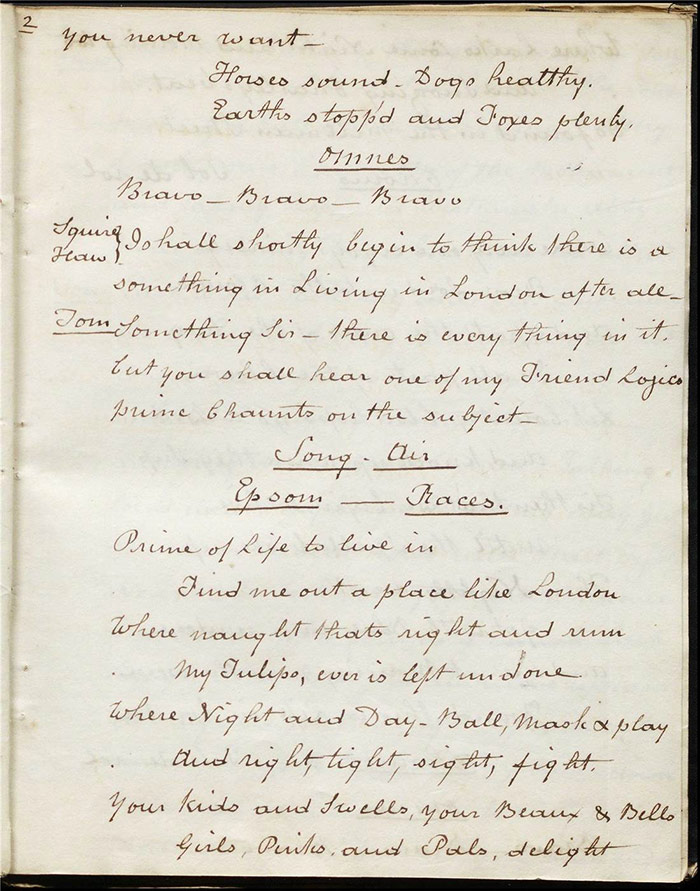

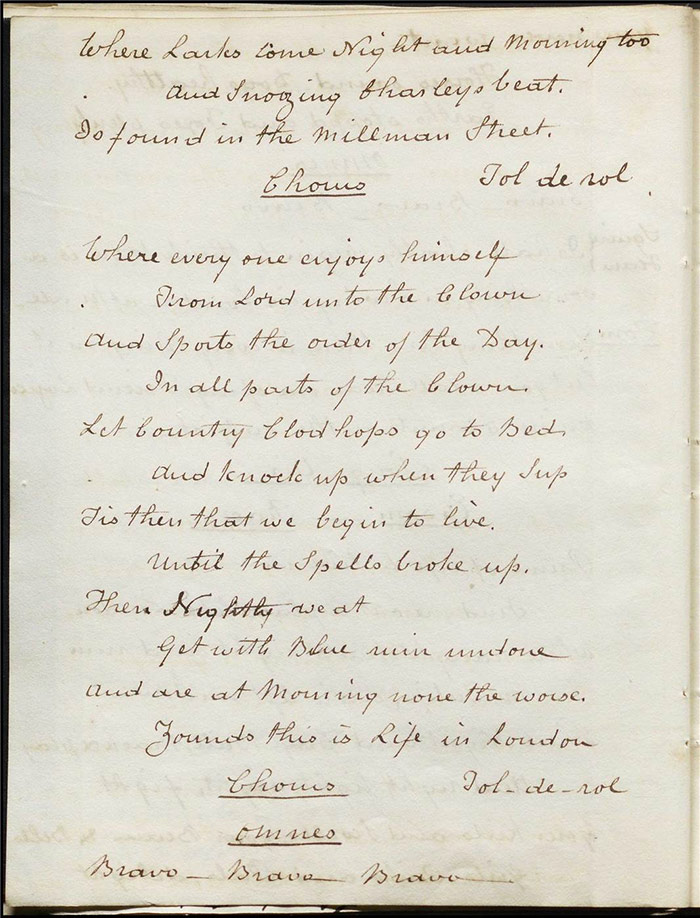

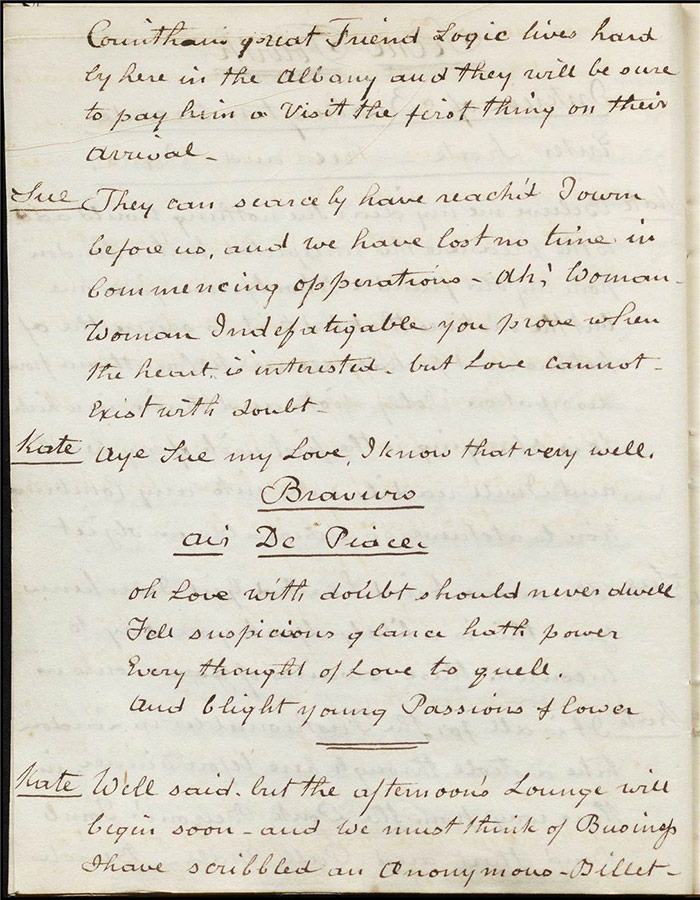

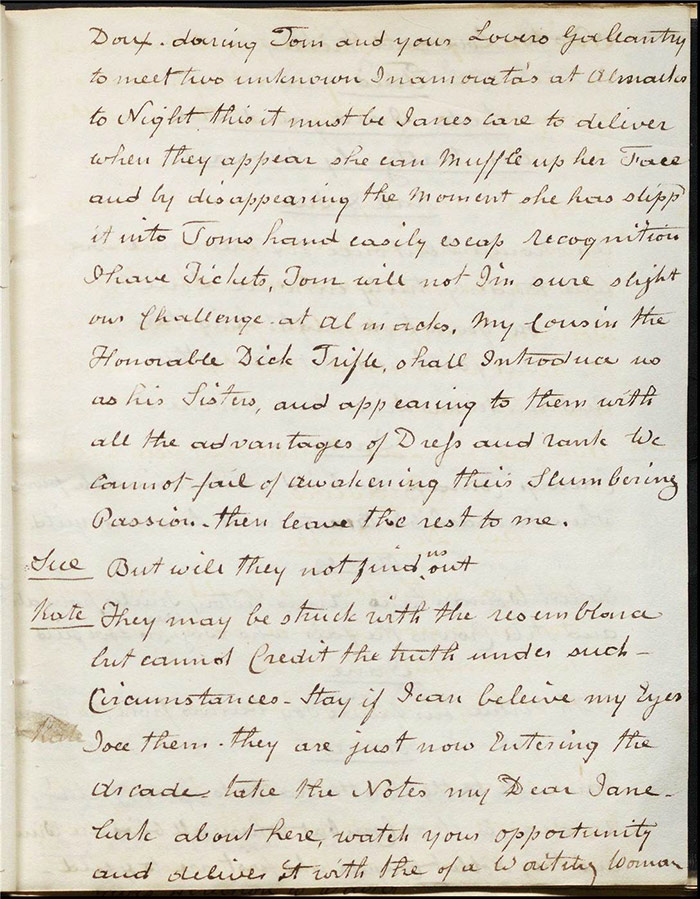

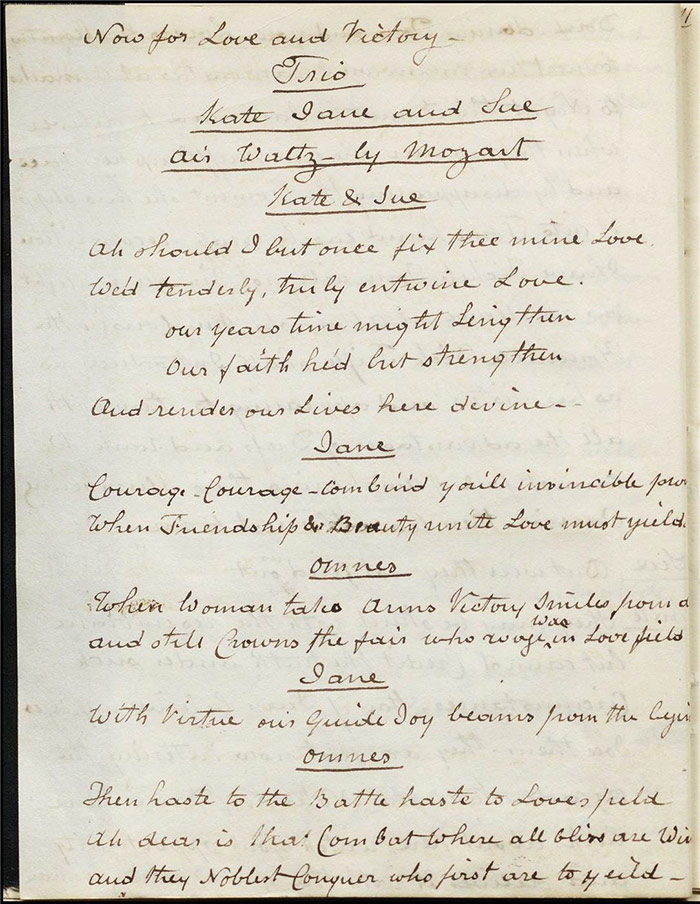

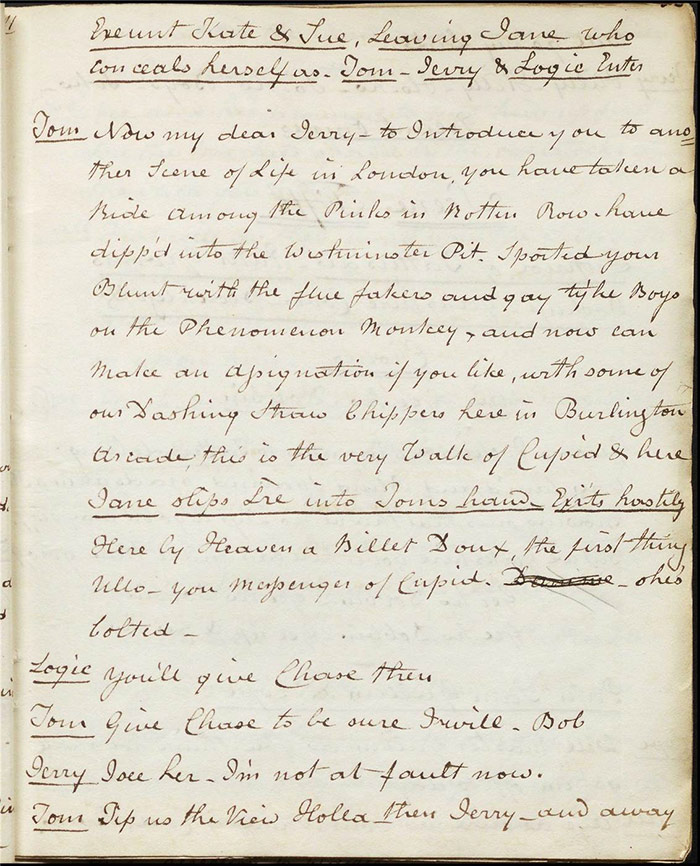

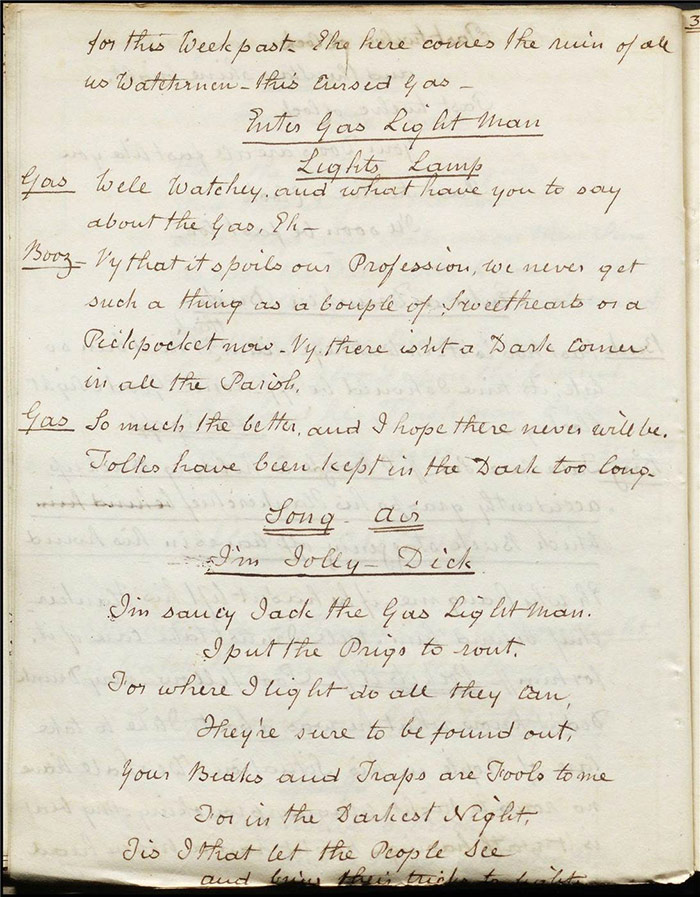

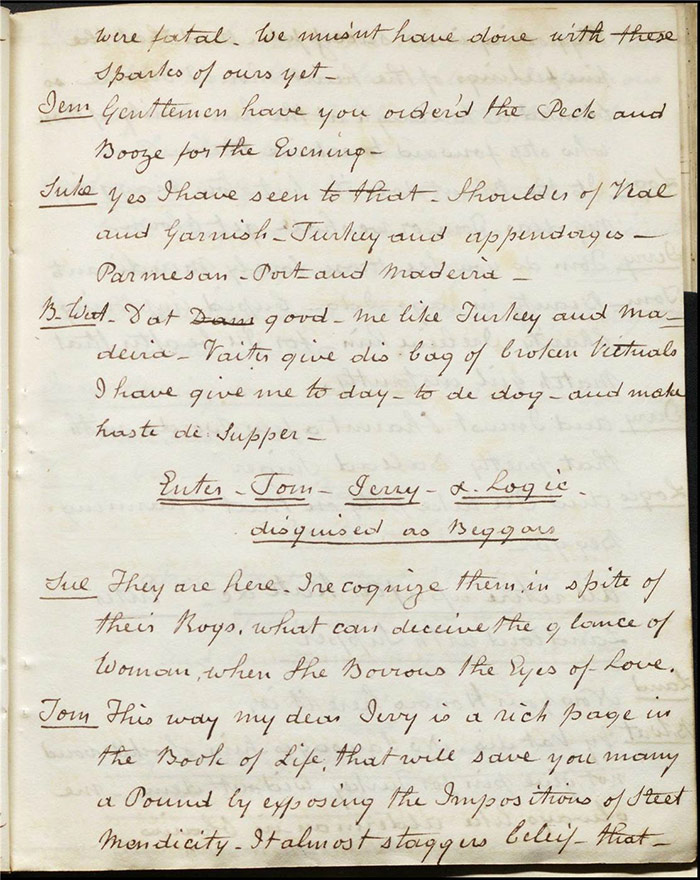

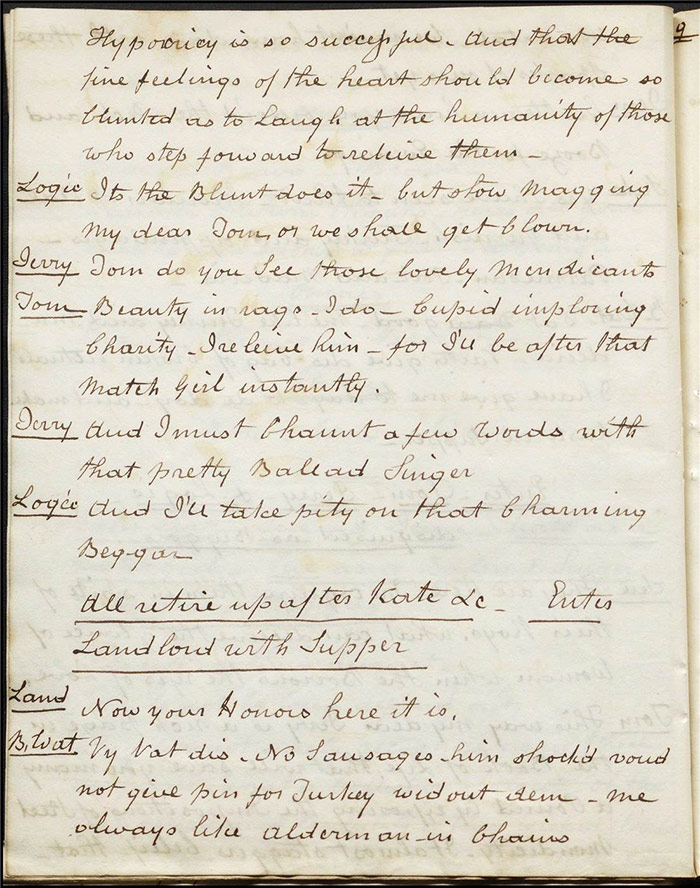

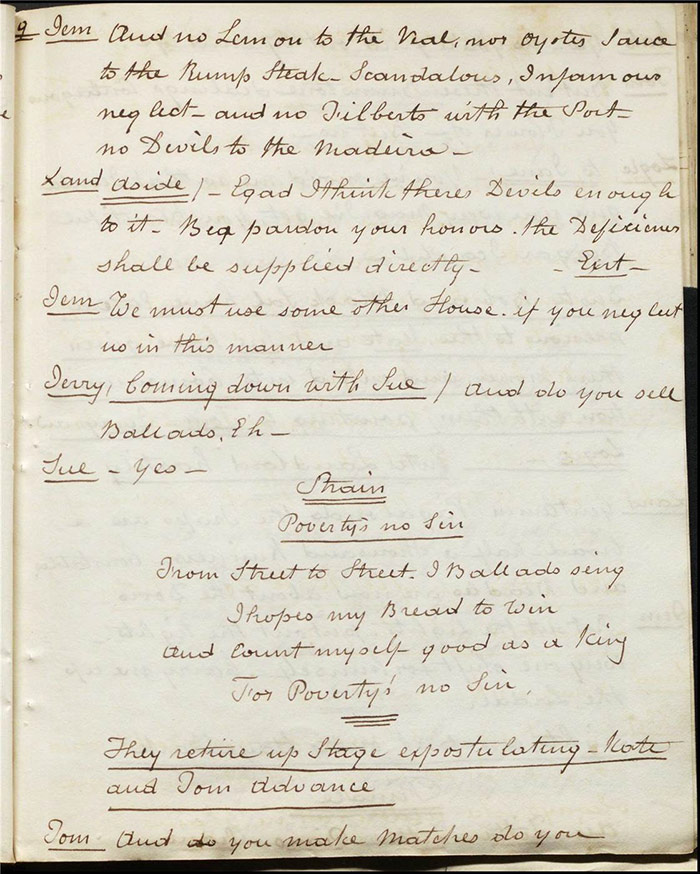

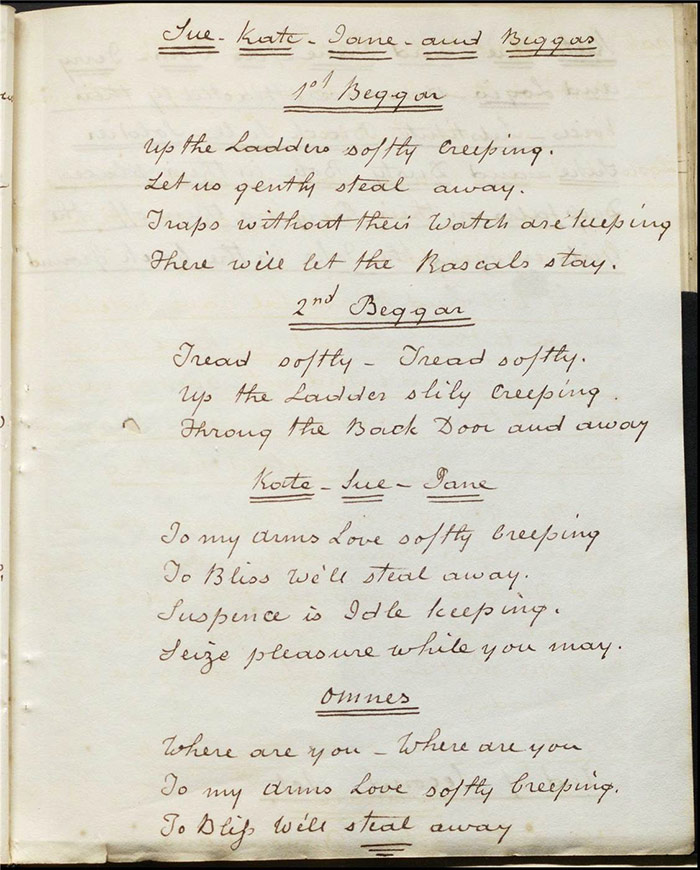

The manuscript has not been refoliated as per most of the other Larpent manuscripts so a division by act and scene is offered below.

Act I

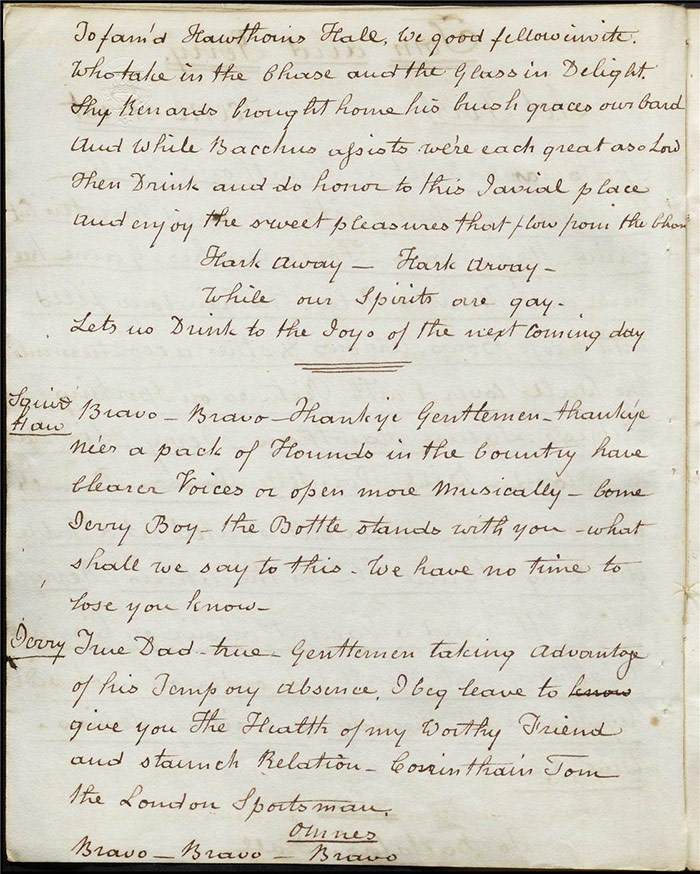

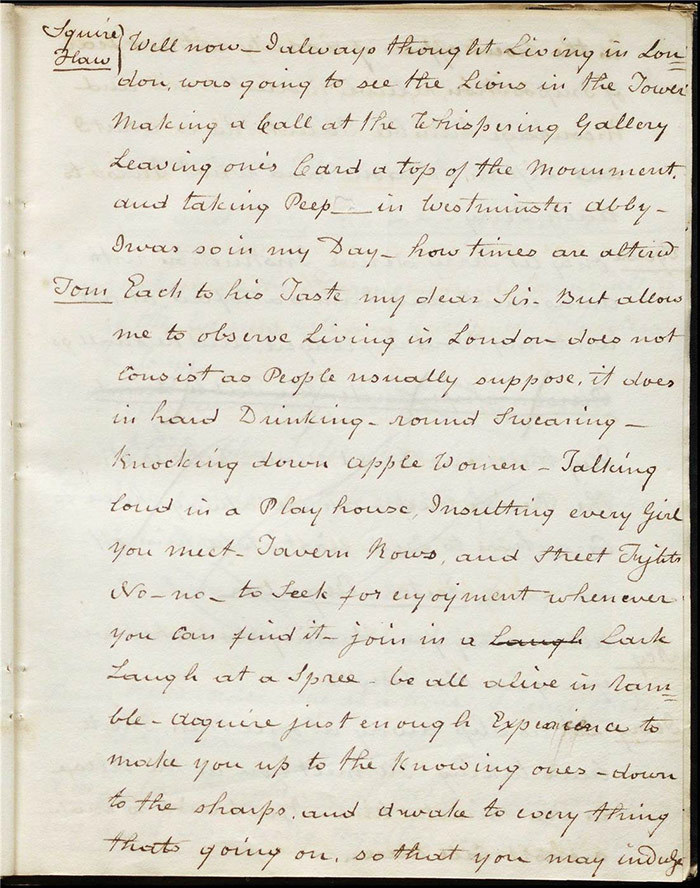

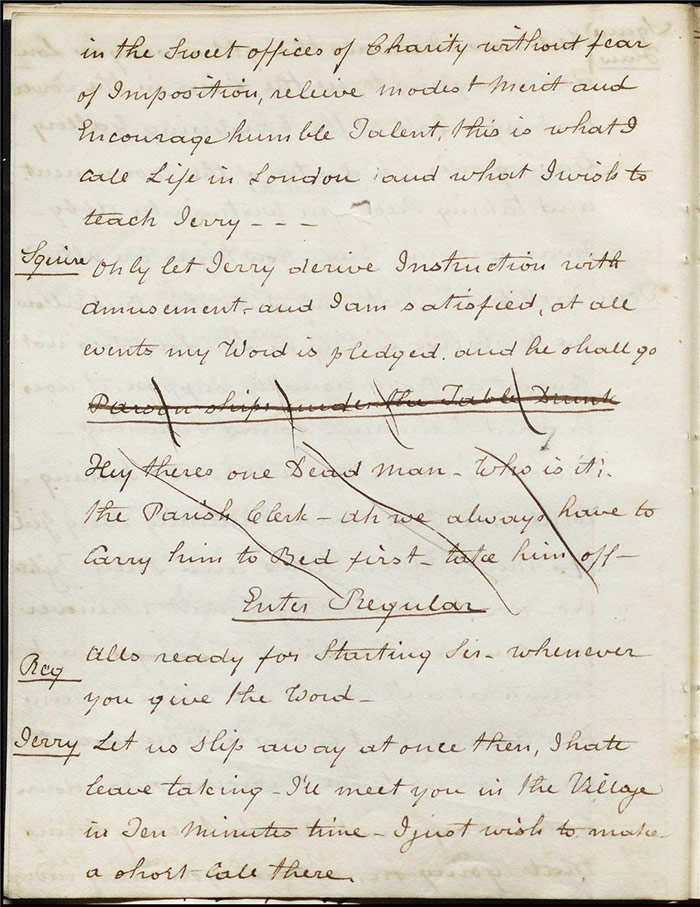

The burletta opens at Hawthorn Hall where Squire Hawthorn is having a drinking party to say goodbye to his son, Jerry, who is going with his cousin Corinthian Tom to live in London.

Scene 2

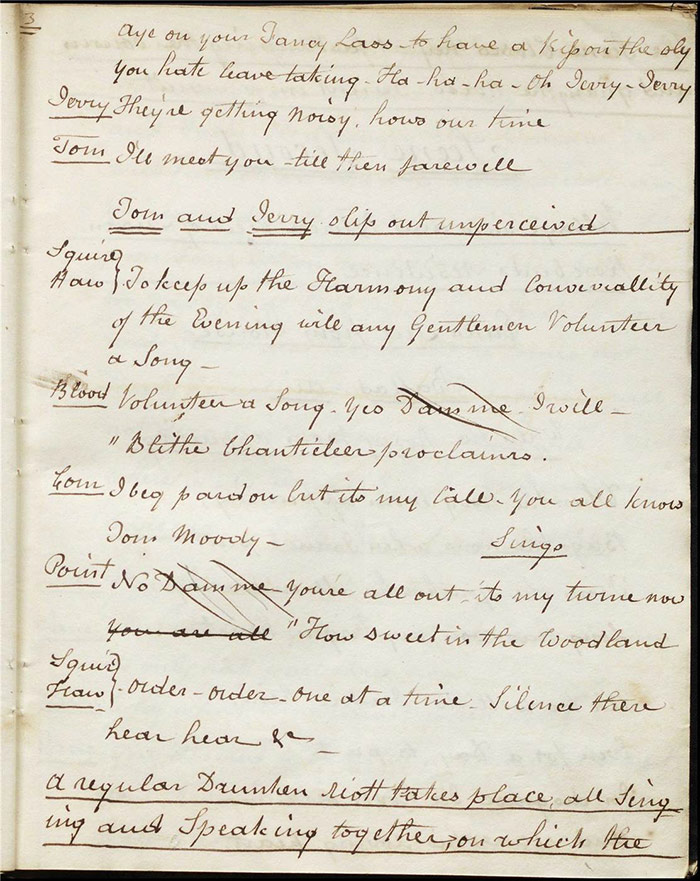

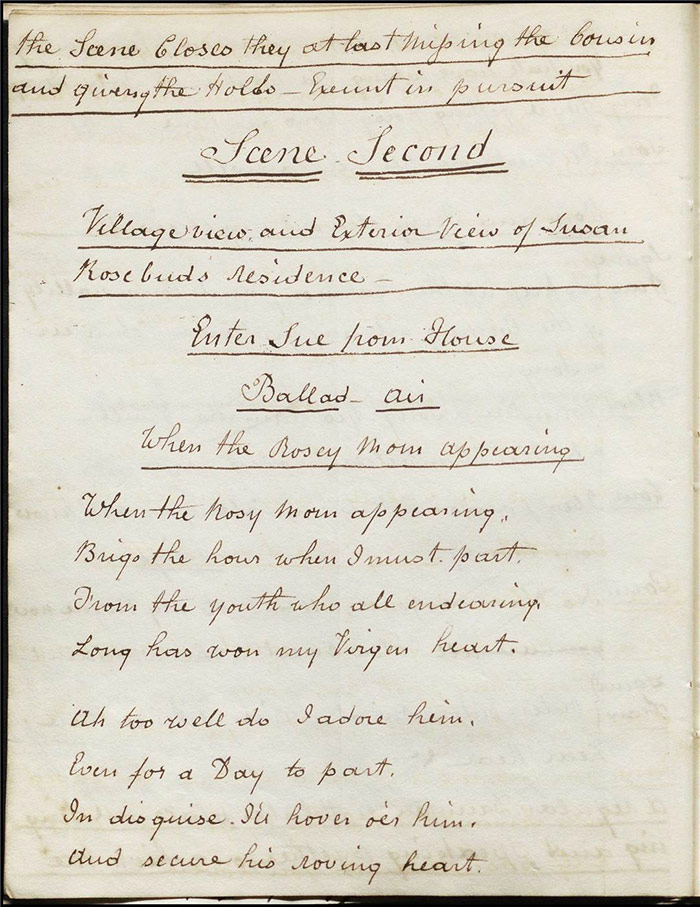

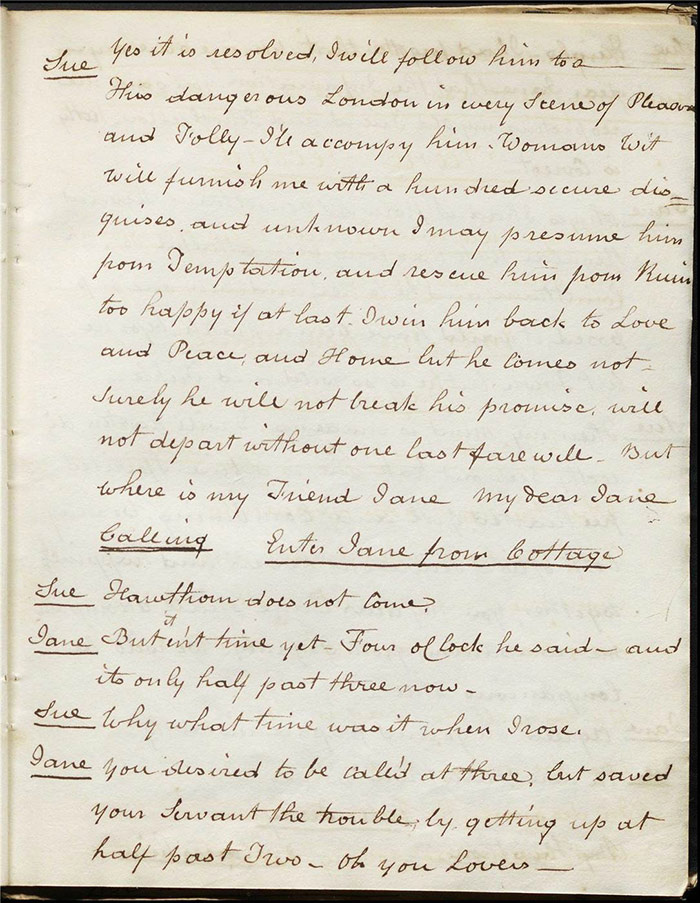

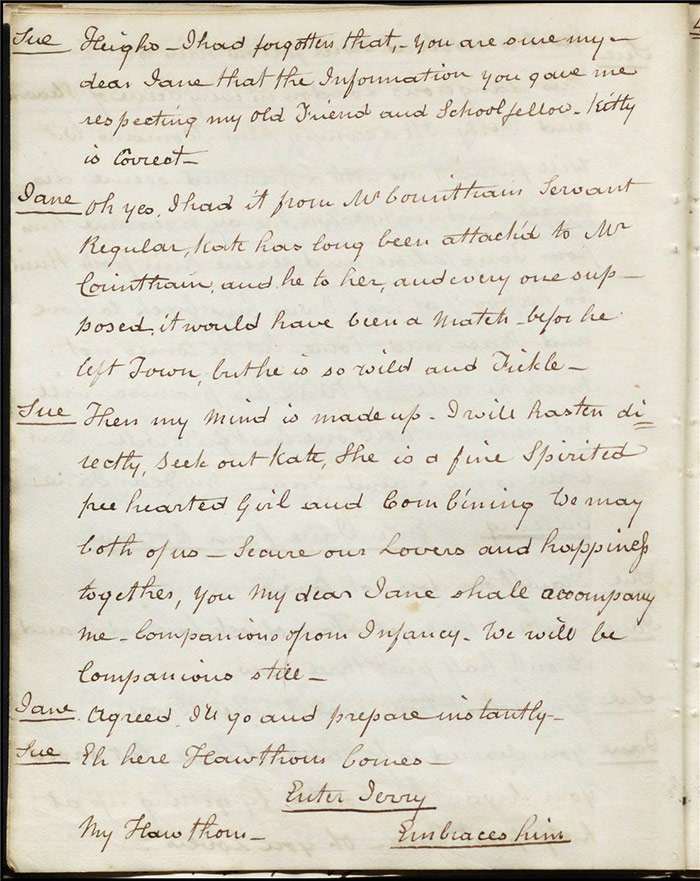

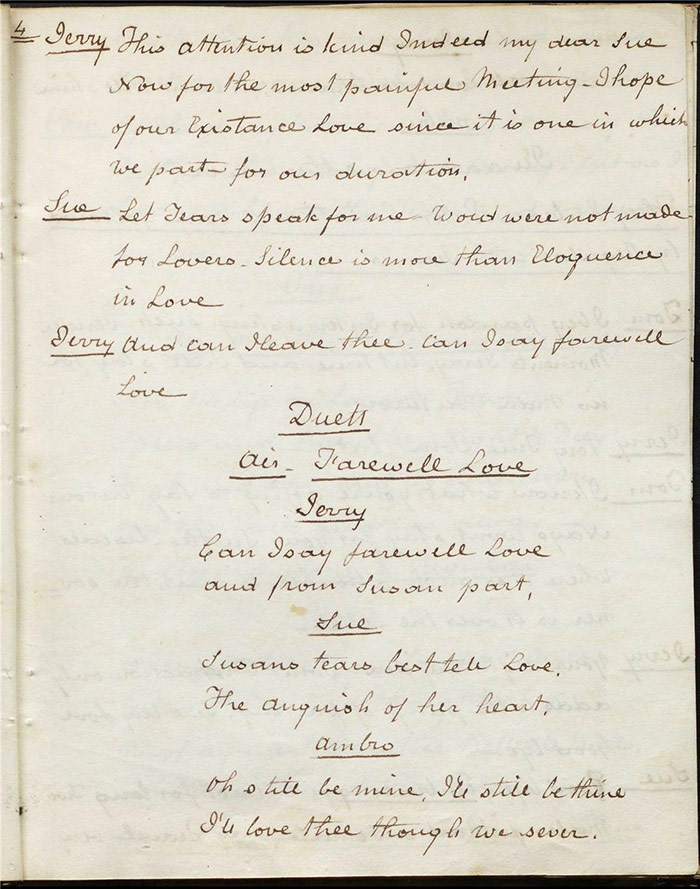

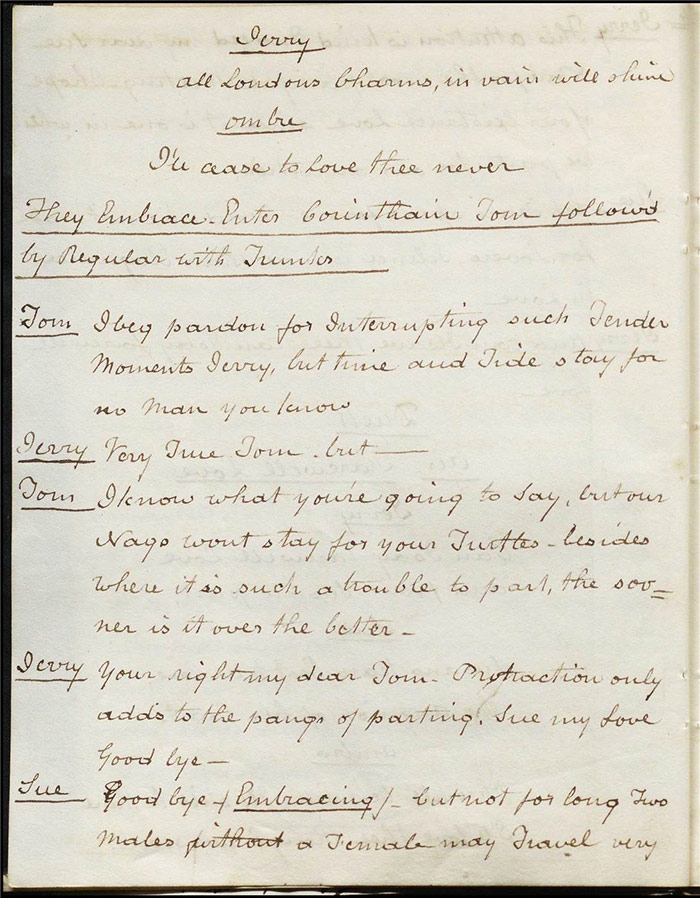

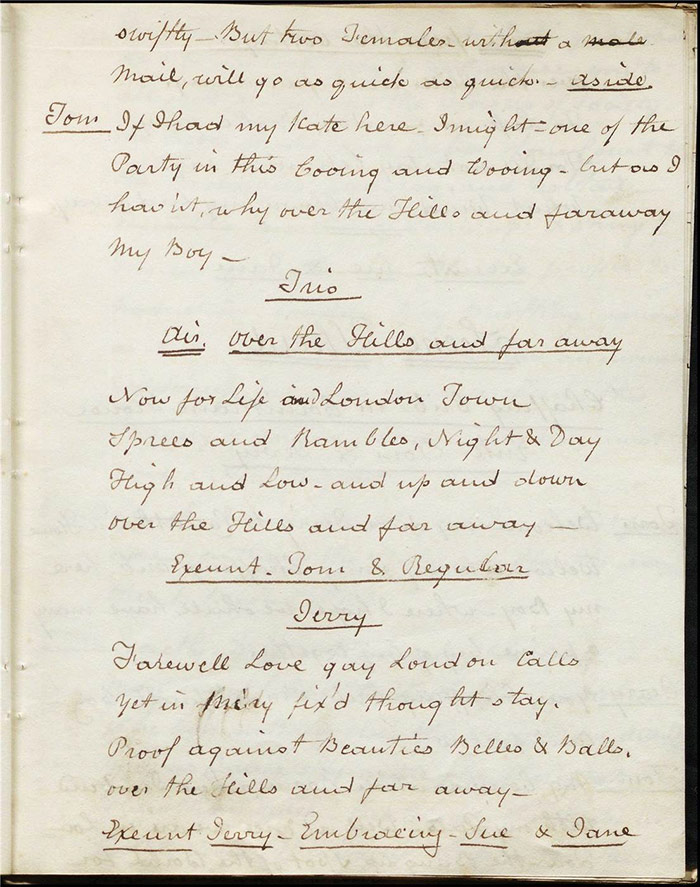

Sue Rosebud is concerned about her lover Jerry going to London. She determines to team up with her friends Kate (in love with Tom) and servant Jane to follow him to London in disguise to protect him from the excesses of London and make sure he comes home to her. Jerry comes says farewell before Tom and his servant, Squire Regular, interrupt and they leave.

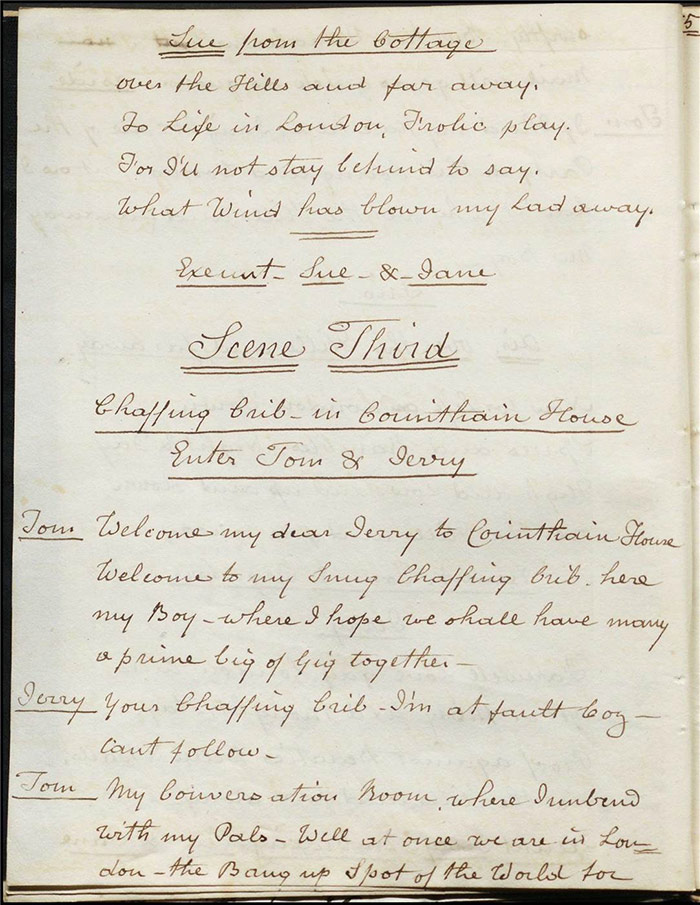

Scene 3

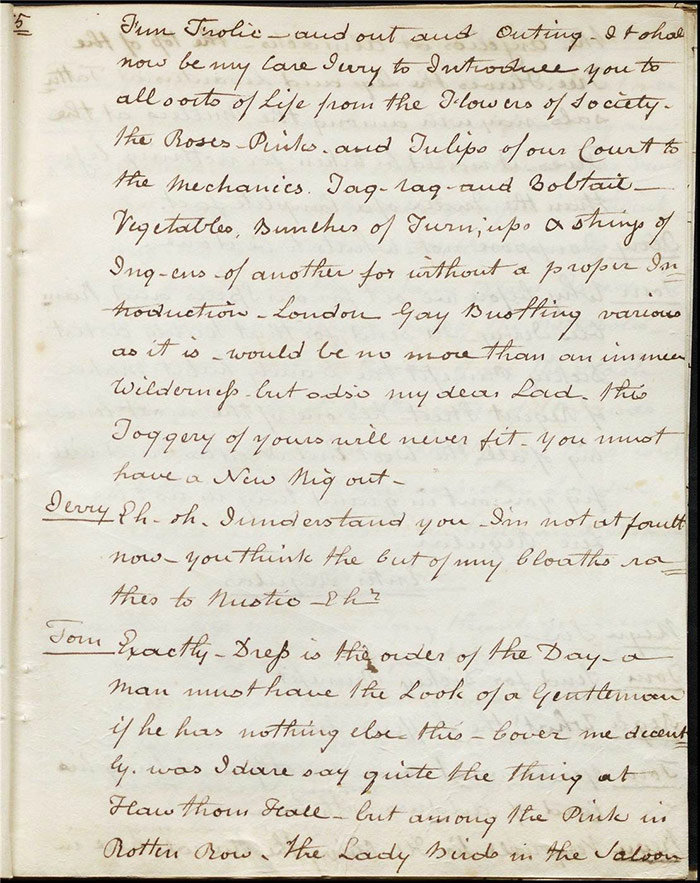

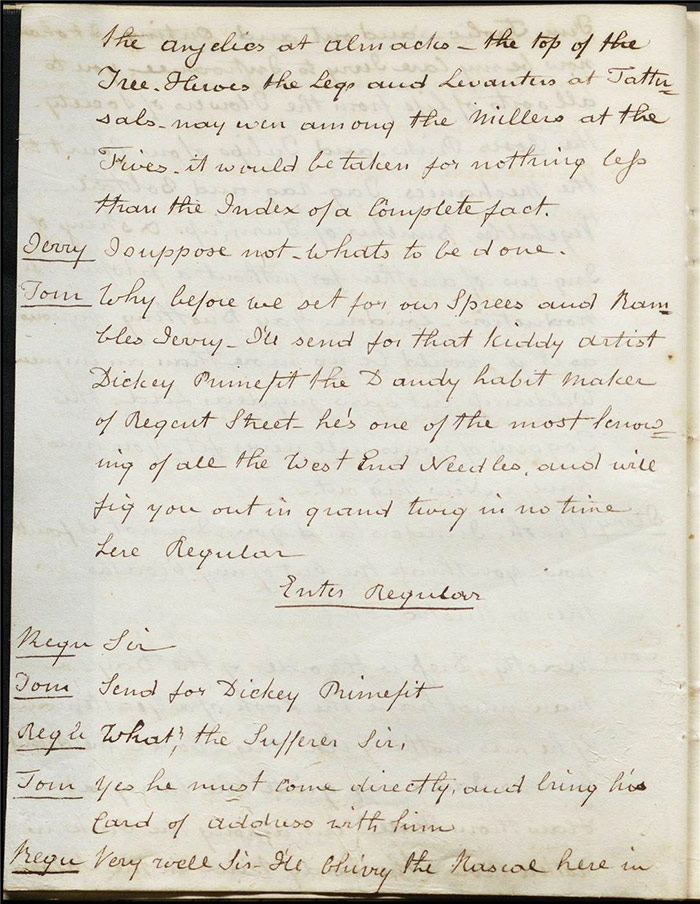

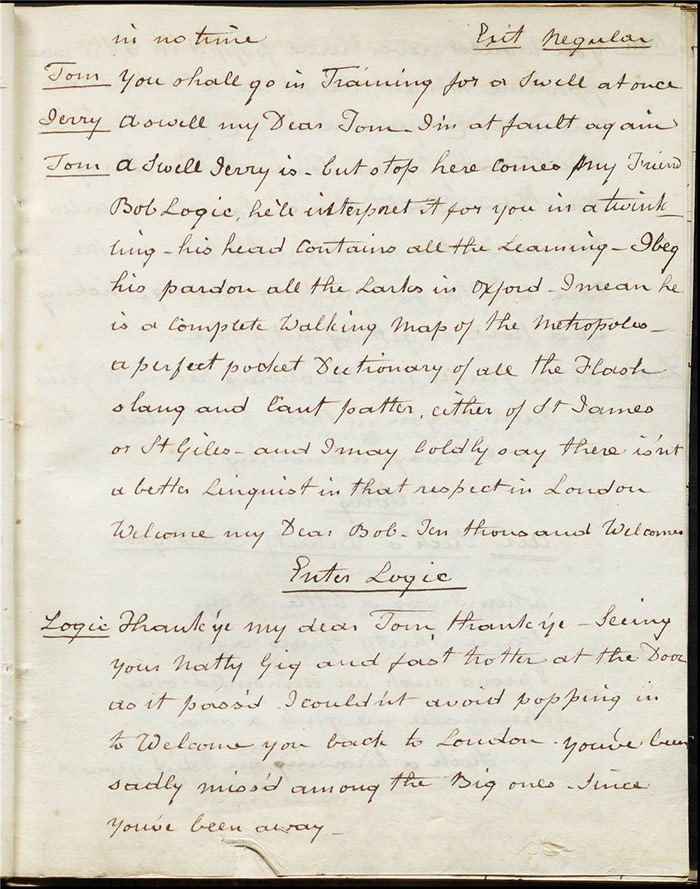

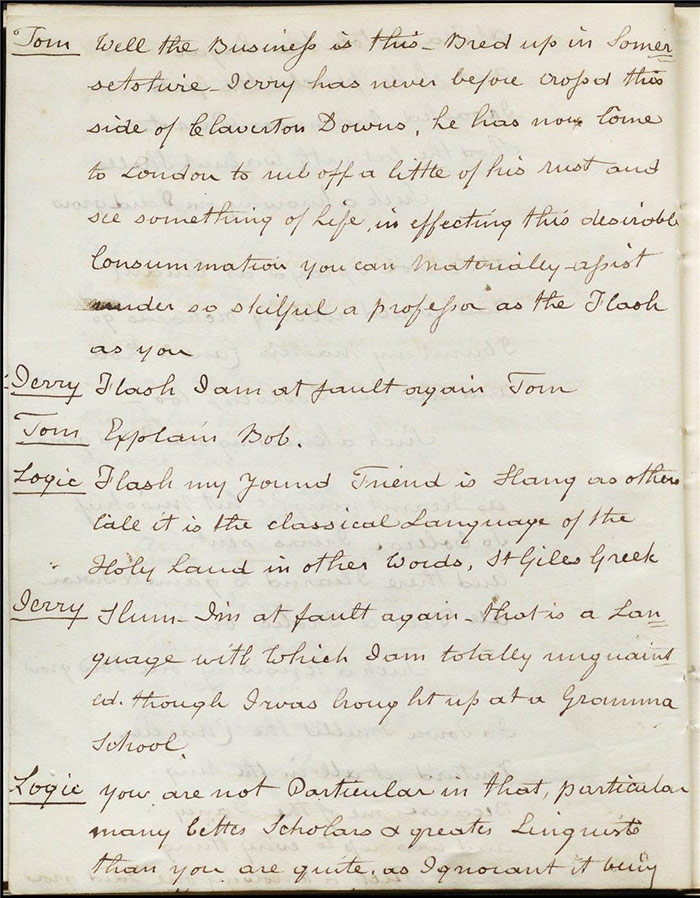

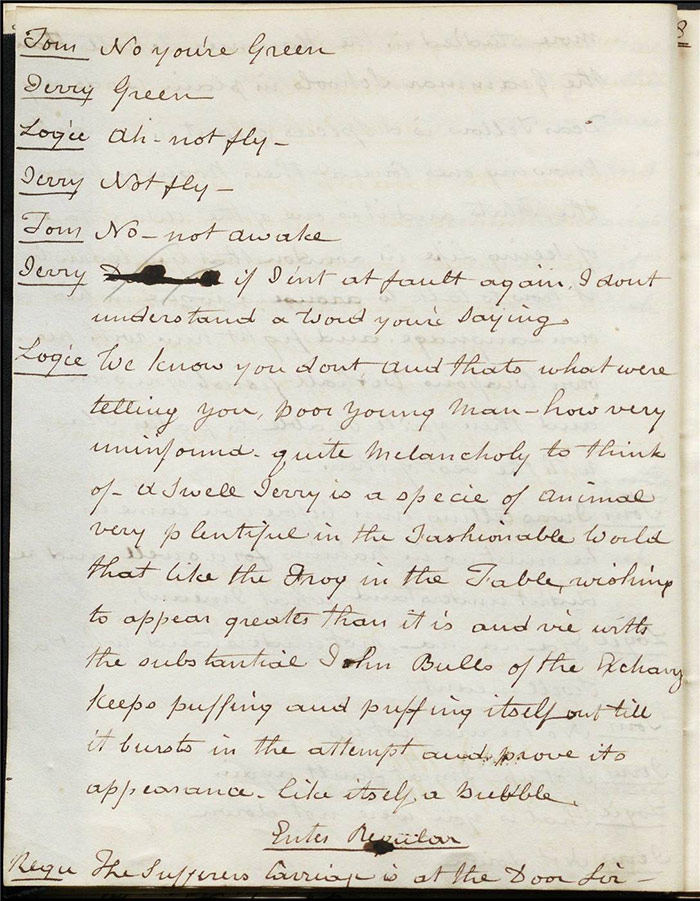

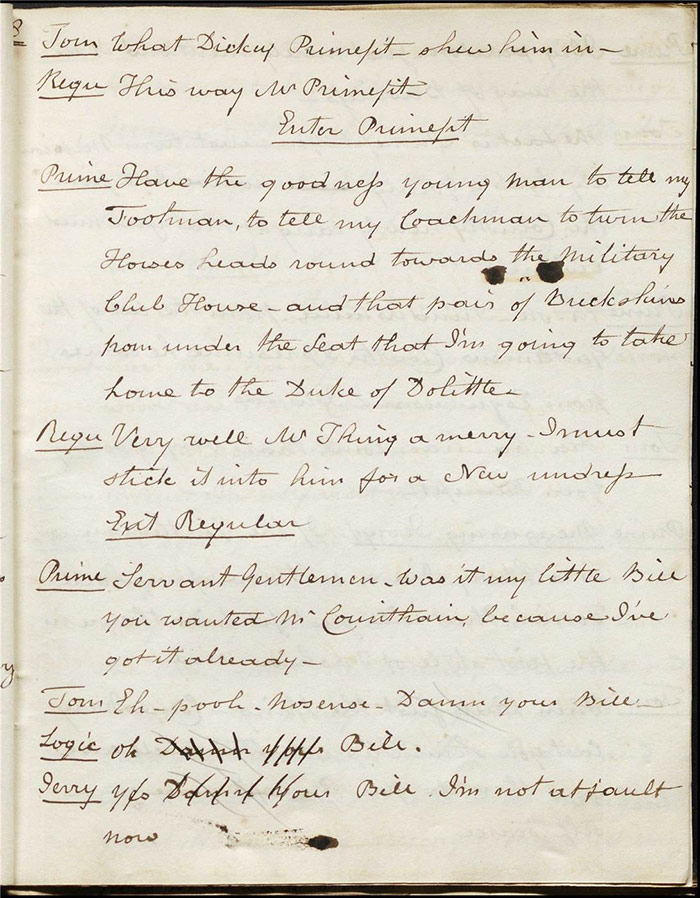

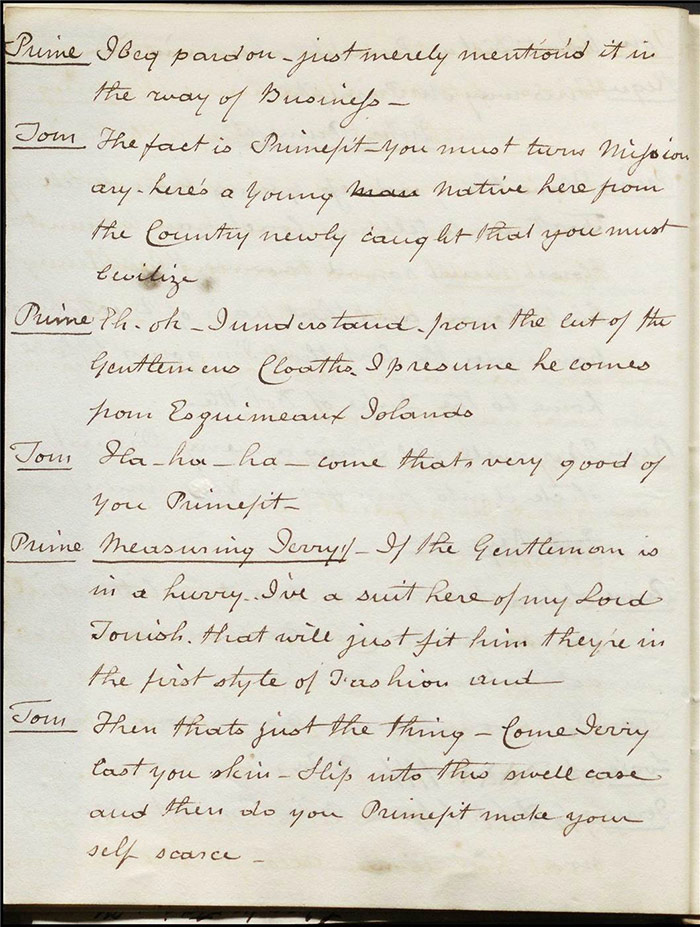

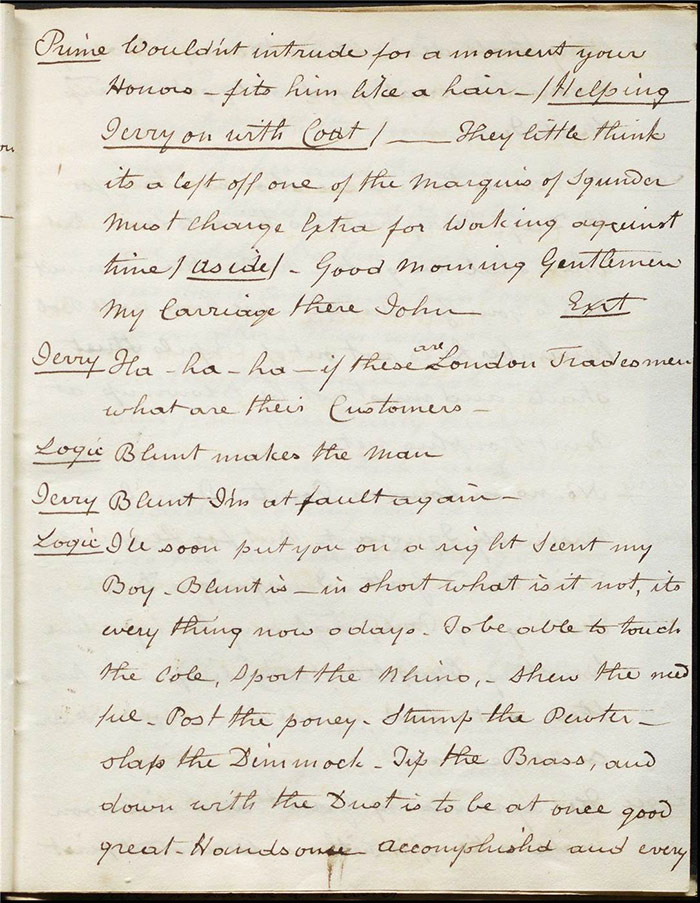

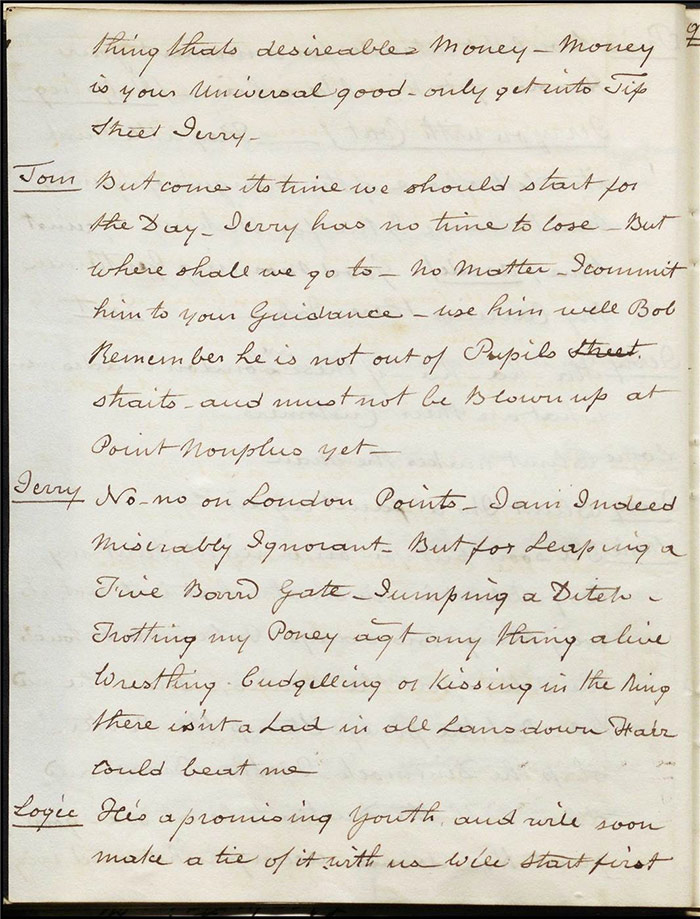

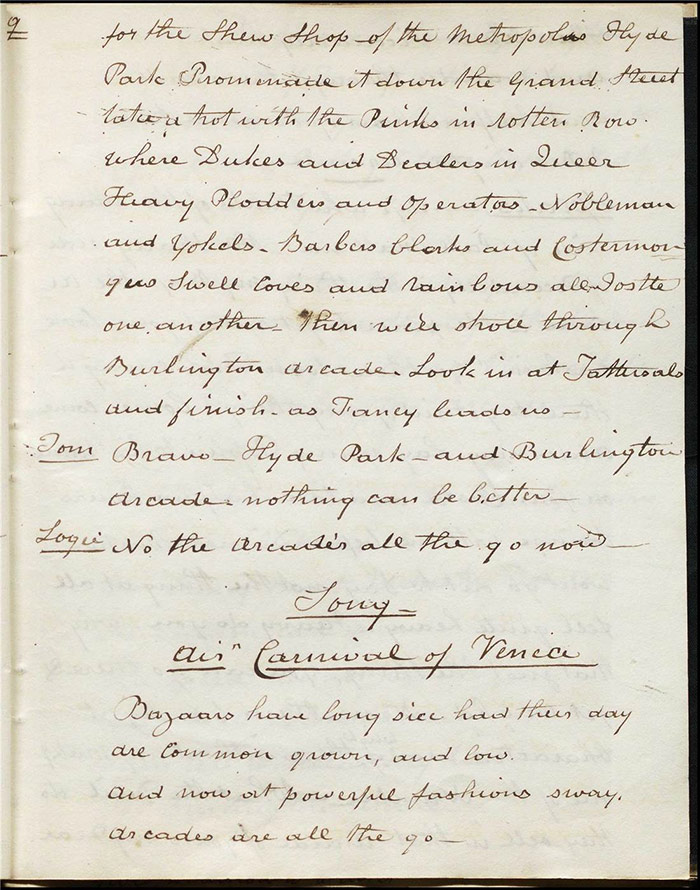

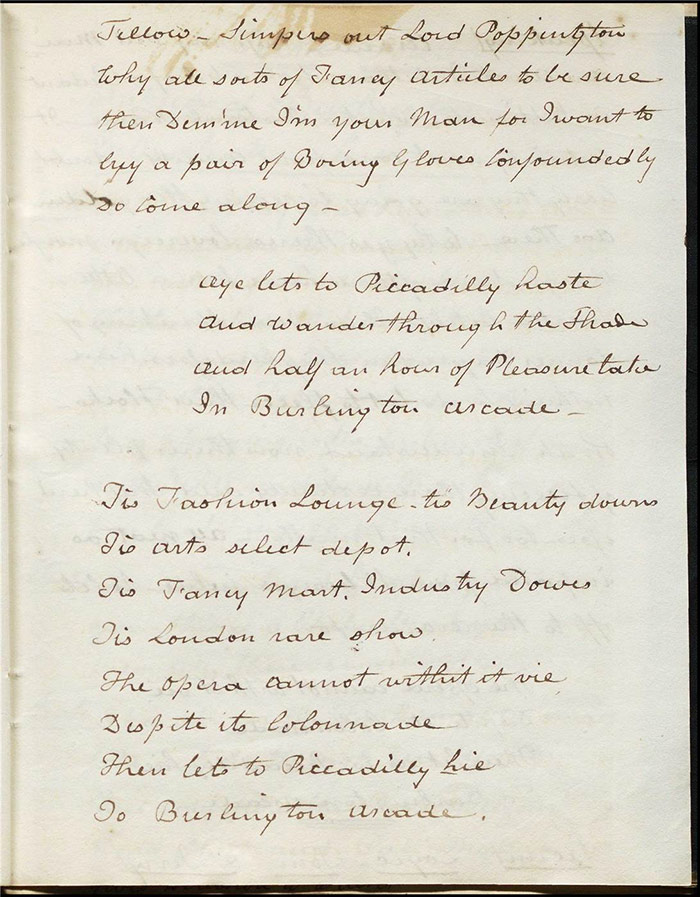

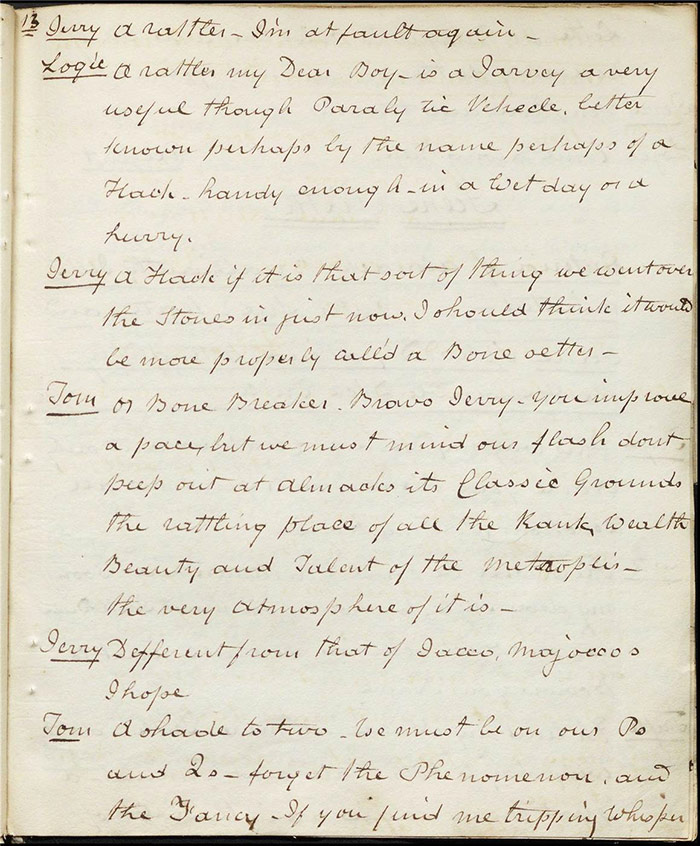

Tom and Jerry are in Corinthian House in London. Tom insists that Jerry will need more fashionable clothes appropriate for London. He calls for Dickey Primefit, the tailor. Bob Logic, Tom’s friend and fellow roisterer, calls and promises to teach Jerry ‘flash’ – London slang (this language pervades the whole burletta and is a marked feature of its success). Tom and Bob bewilder Jerry with their exchange. Primefit comes and fits Jerry with some new clothes and Bob promises to take him on a tour of London.

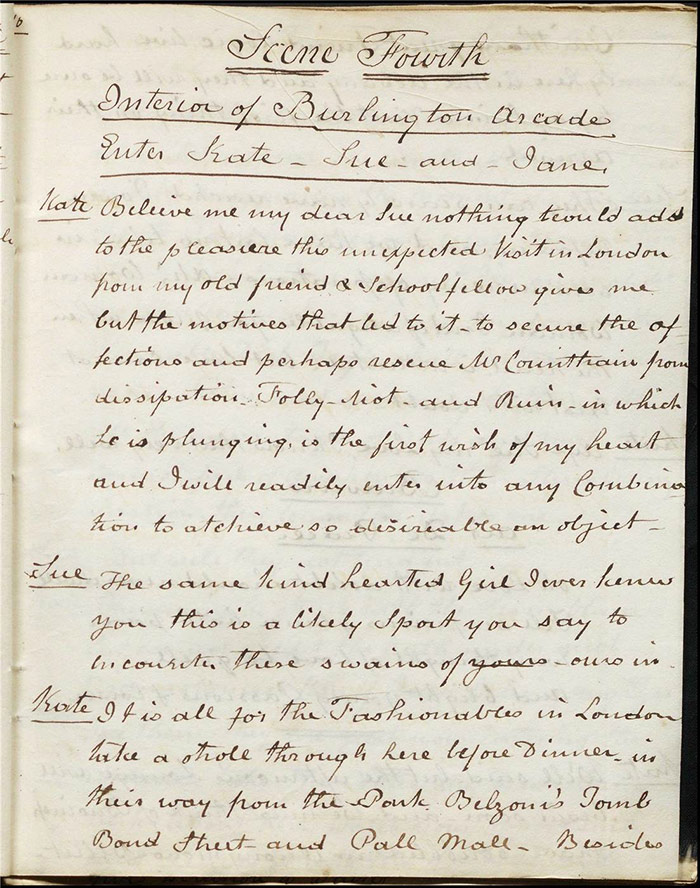

Scene 4

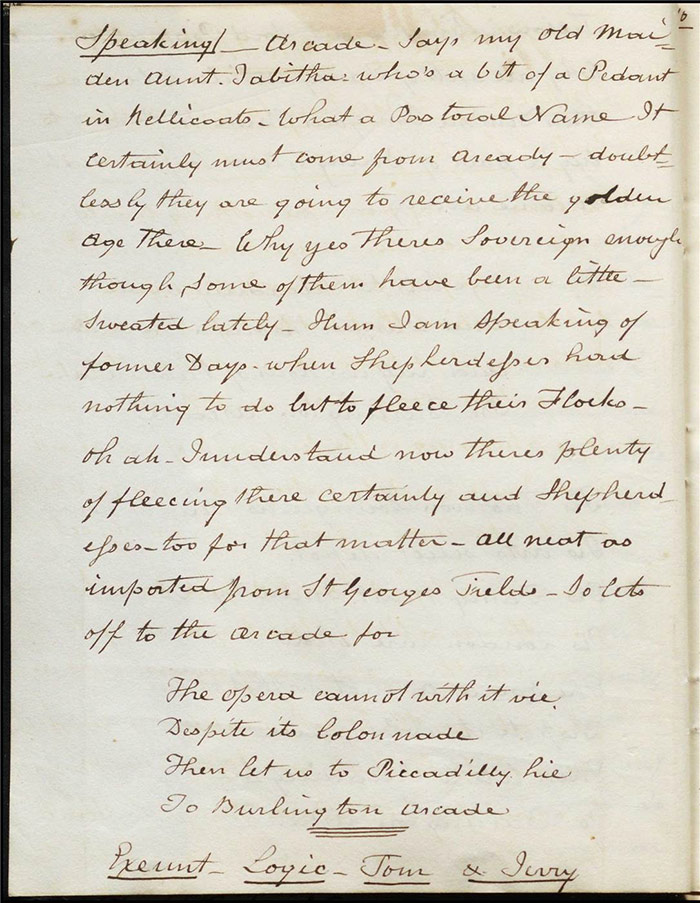

At Burlington Arcade Kate, Sue and Jane formulate a plan to rein in the men. Kate and Sue will disguise themselves as Dick Trifle’s sisters and get an introduction to them under the pretence of being attracted to them. Tom, Jerry and Bob arrive and Jane surreptitiously slips a billet doux (to entice them to a meeting) into Tom’s hand. The men chase the women.

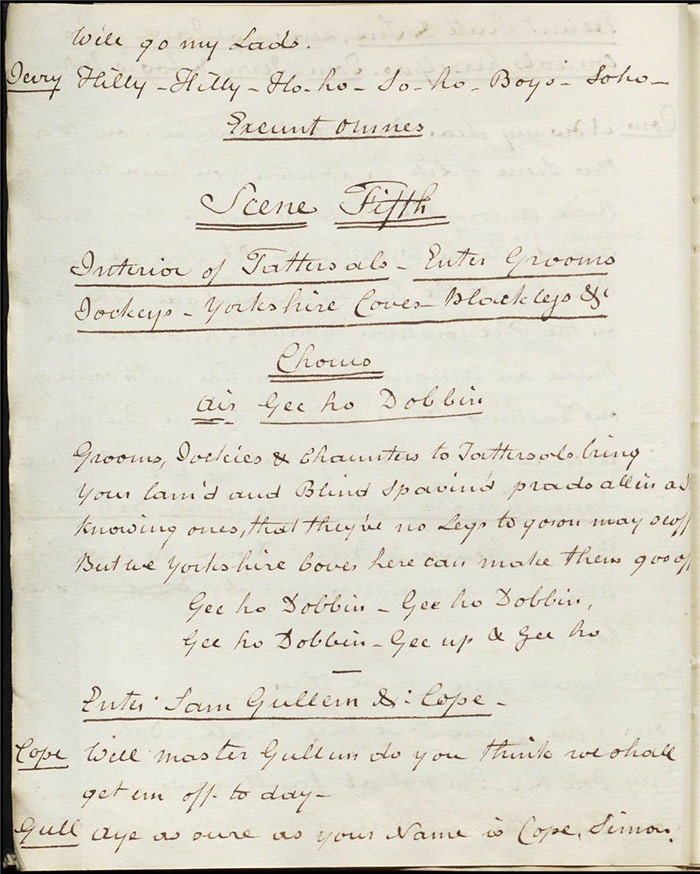

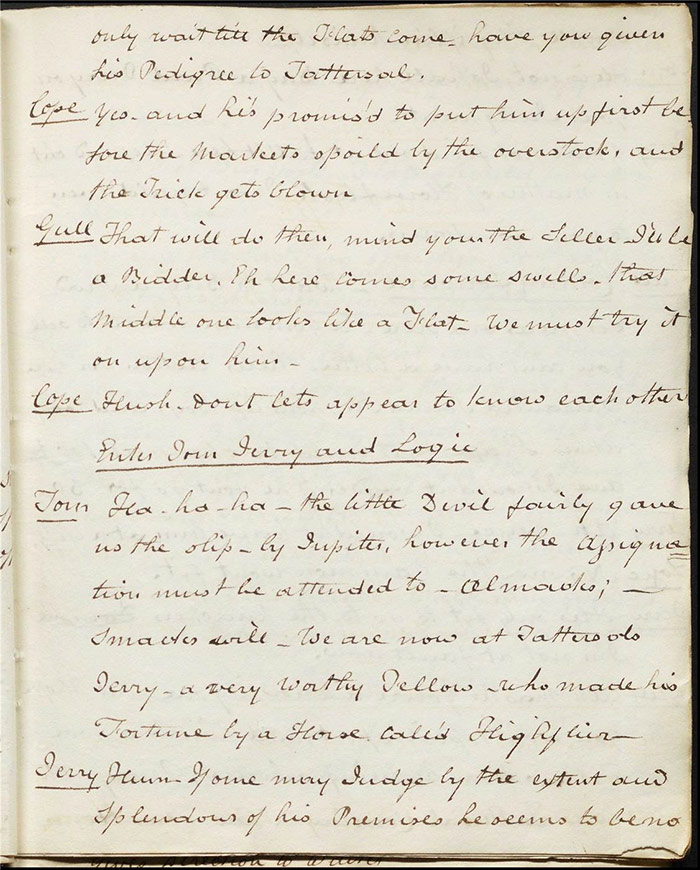

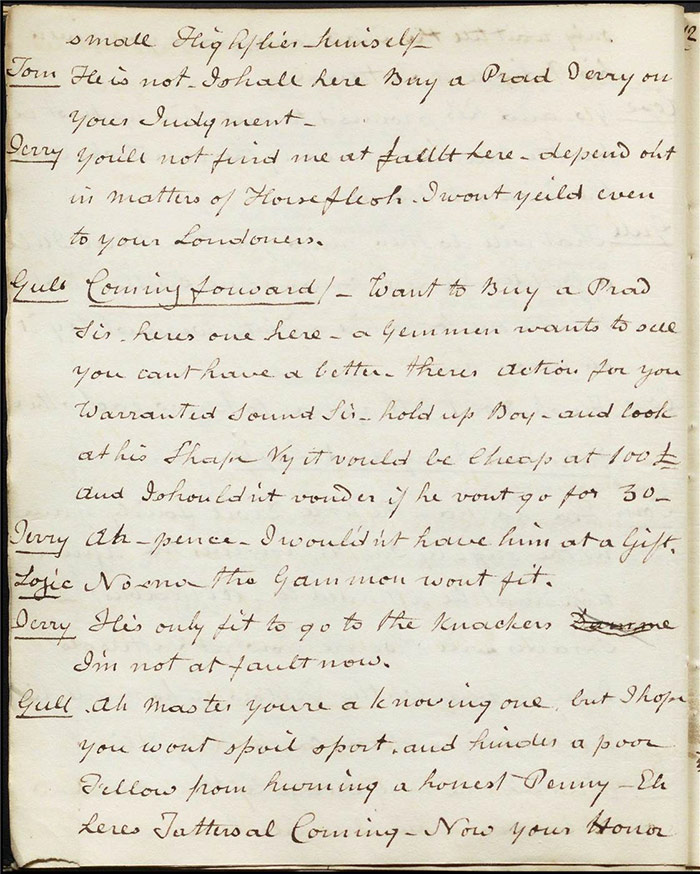

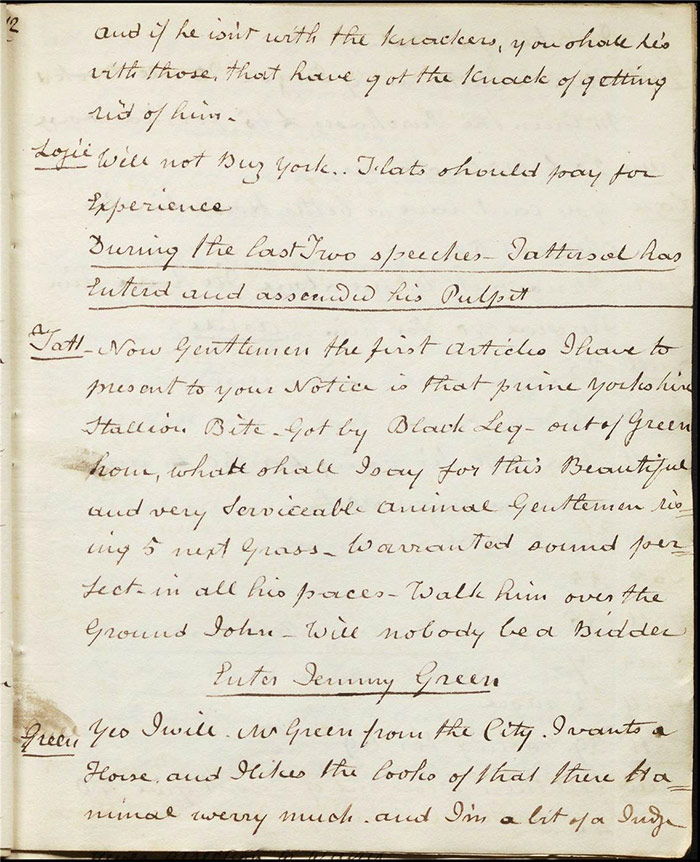

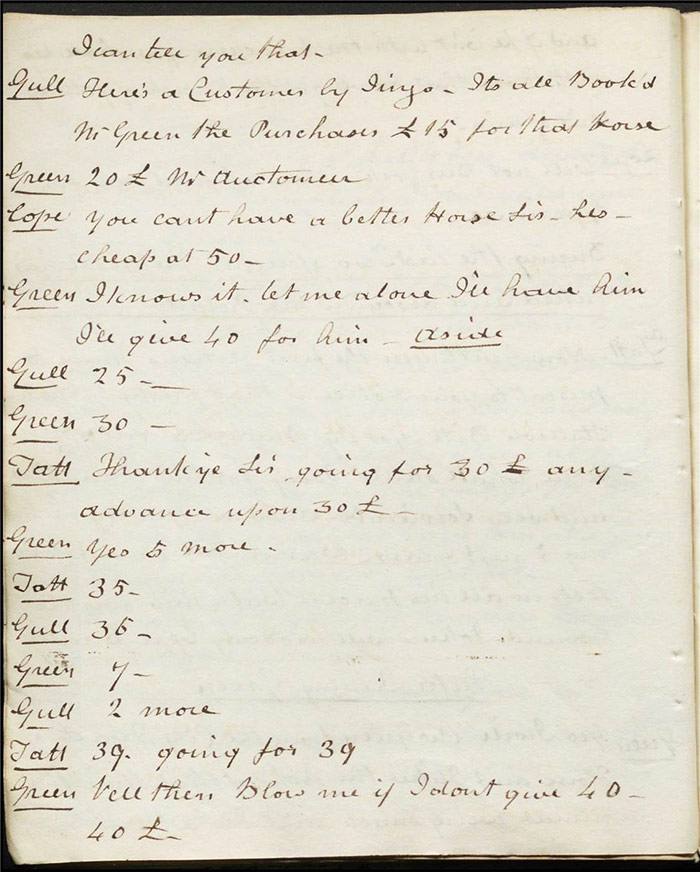

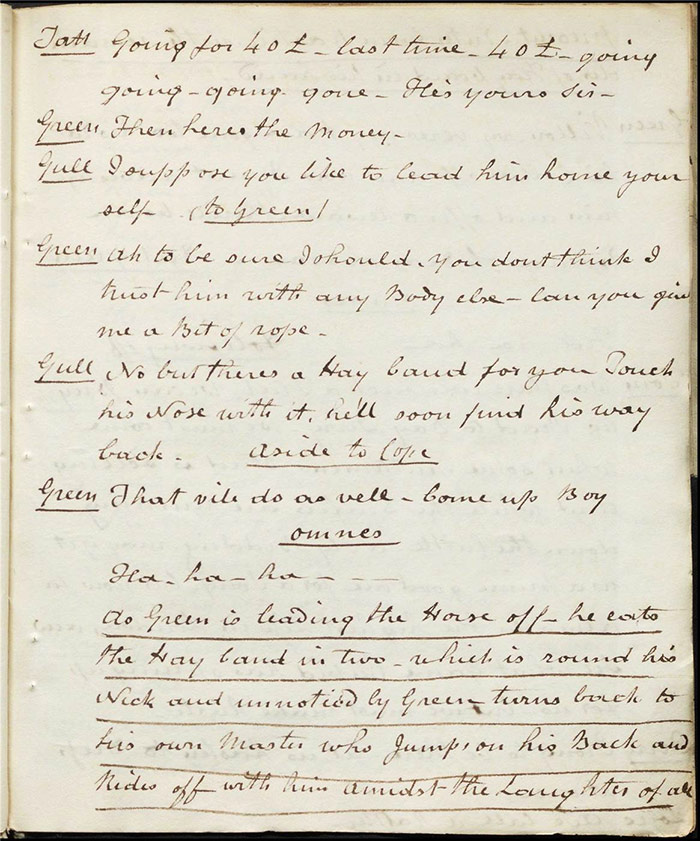

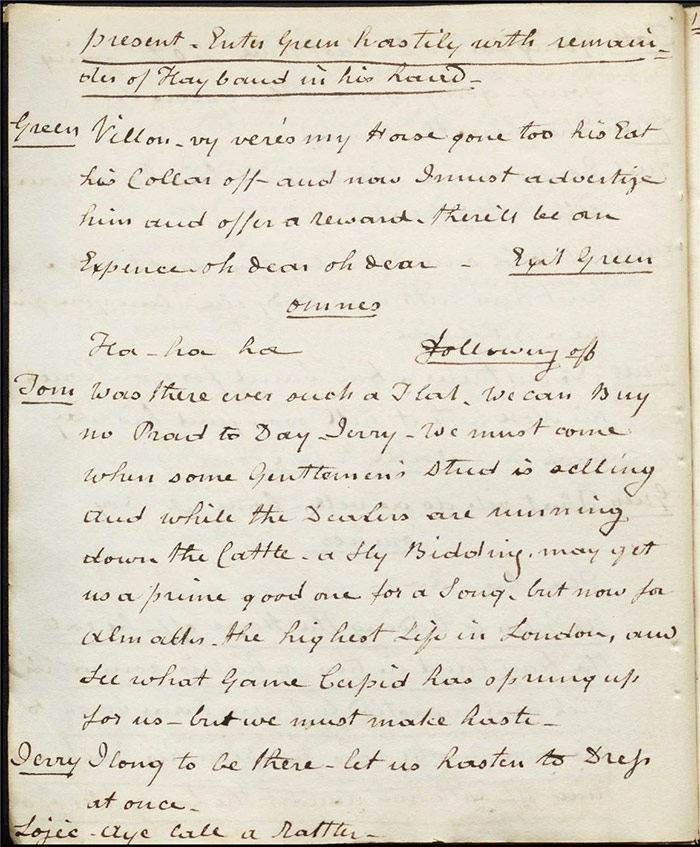

Scene 5

At Tattersal’s race horse auctioneers, Sam Gullem and Cope decide to con the approaching Tom, Jerry and Bob. Tattersal auctions a horse with Gullem’s aid and the unsuspecting buyer, Jem Green, parts with his money before the horse returns to his master. After this piece of chicanery, they decide to go to Almack’s.

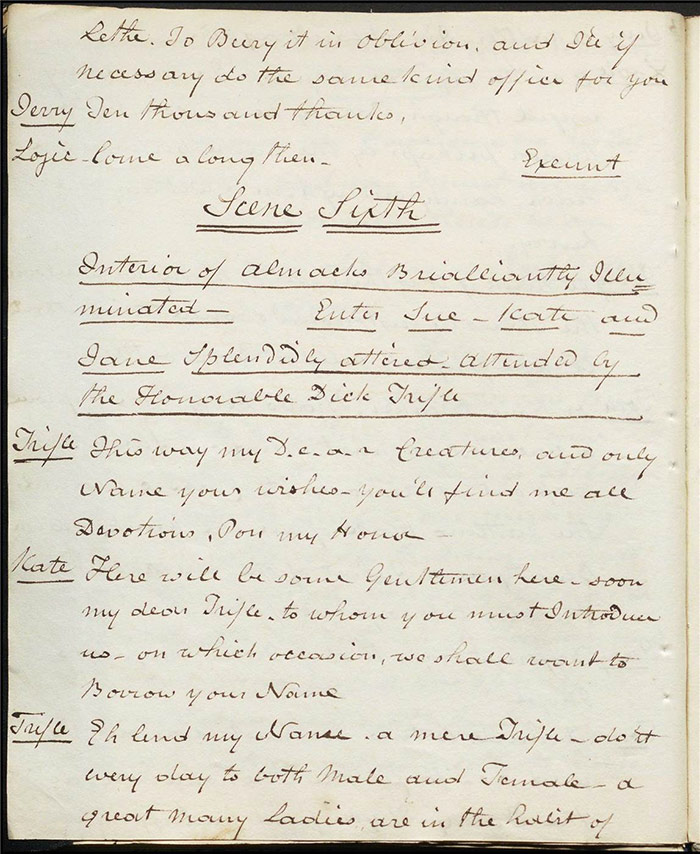

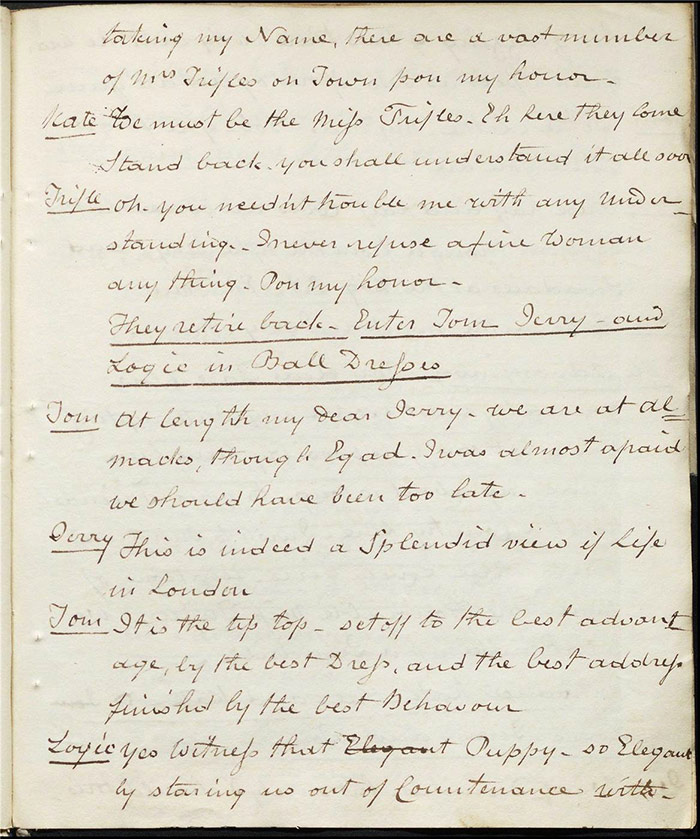

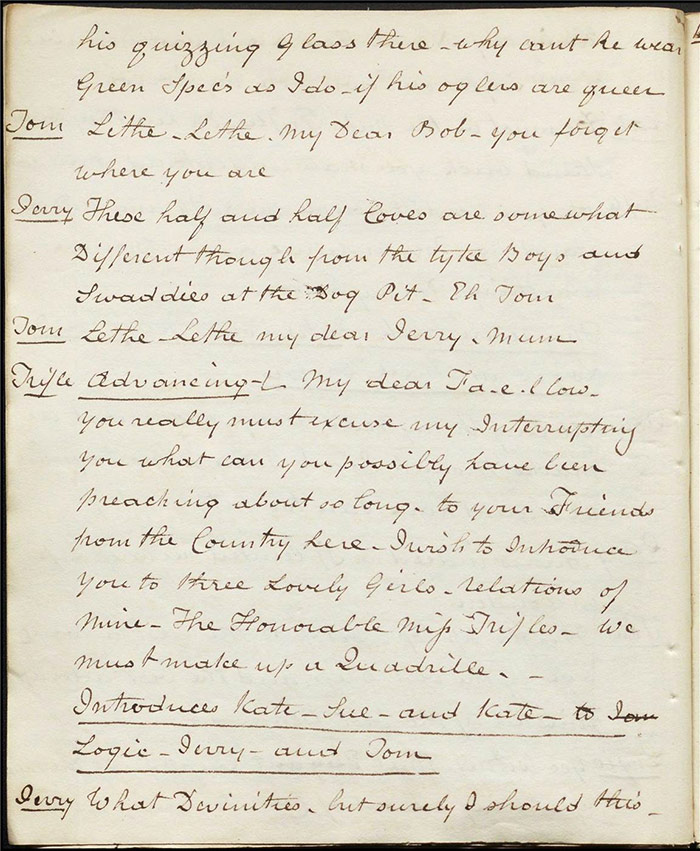

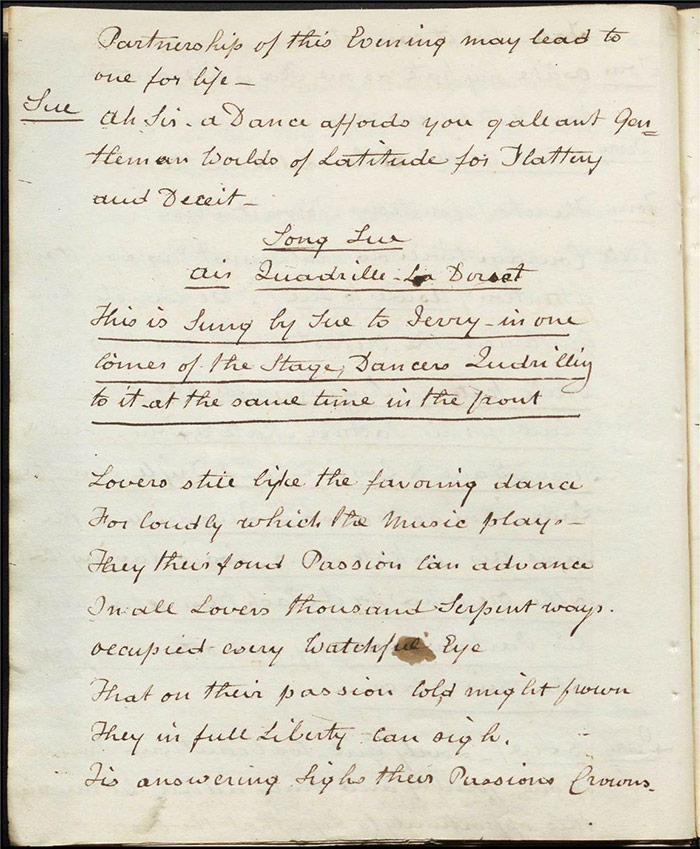

Scene 6

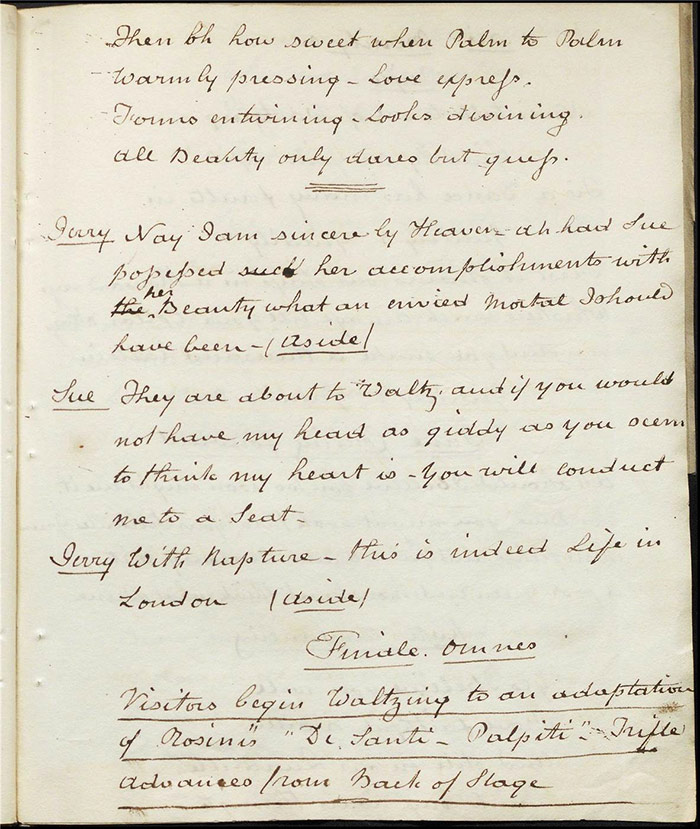

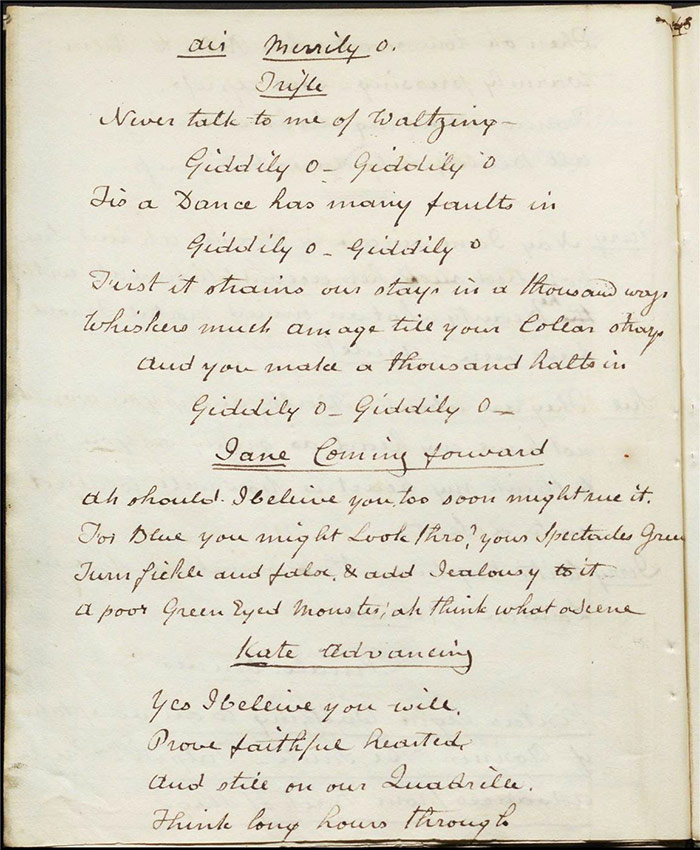

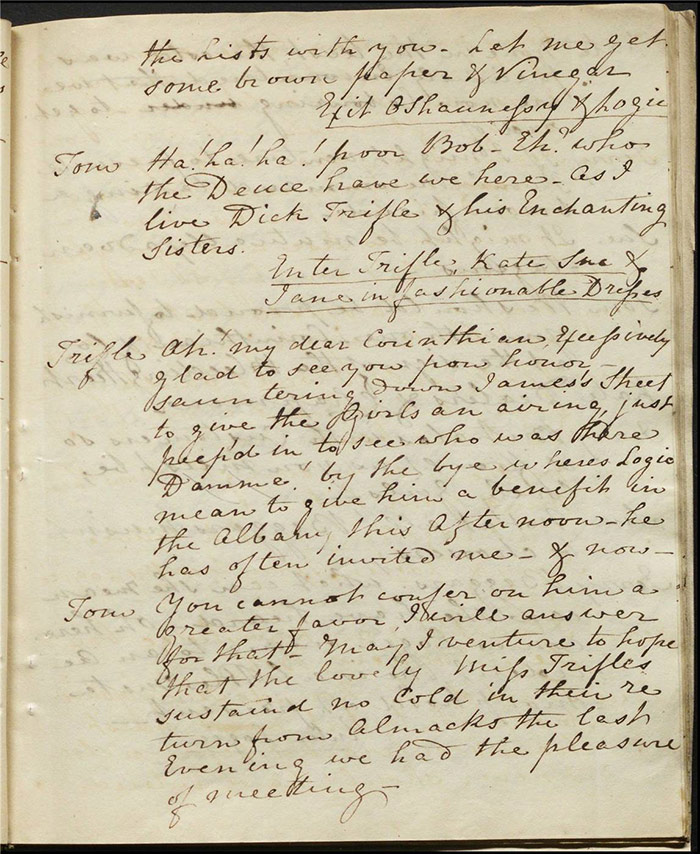

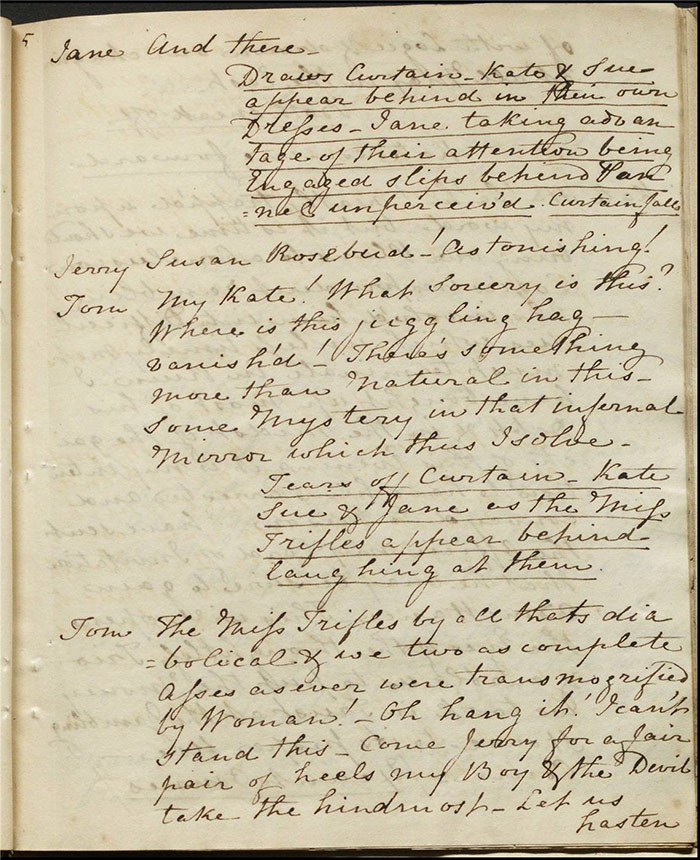

Almack’s assembly room sees Sue, Kate and Jane splendidly dressed and escorted by Dick Trifle. He introduces them to Tom, Jerry, and Bob as the Miss Trifles when they arrive. They dance a quadrille and then a waltz.

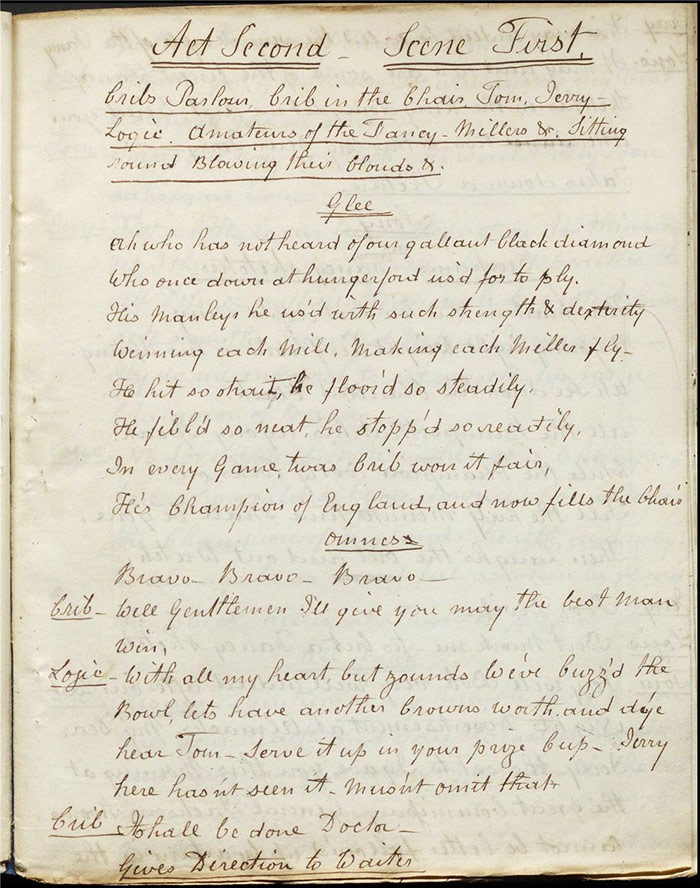

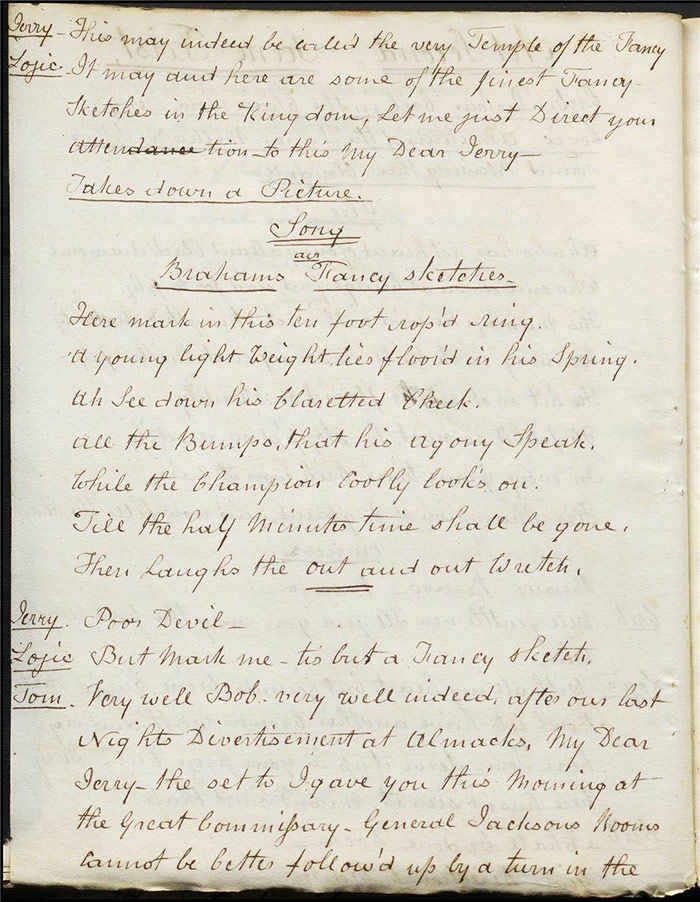

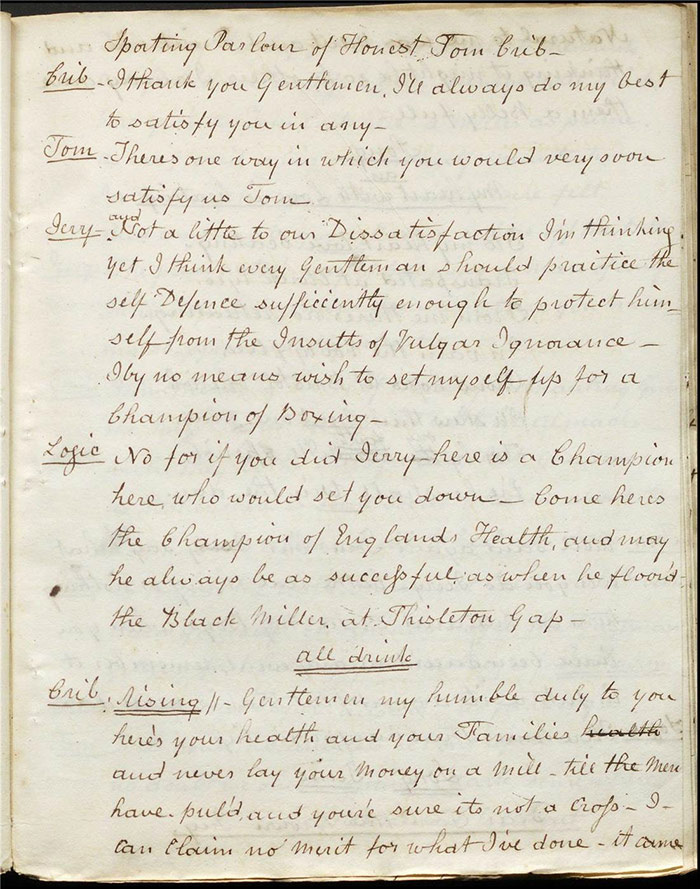

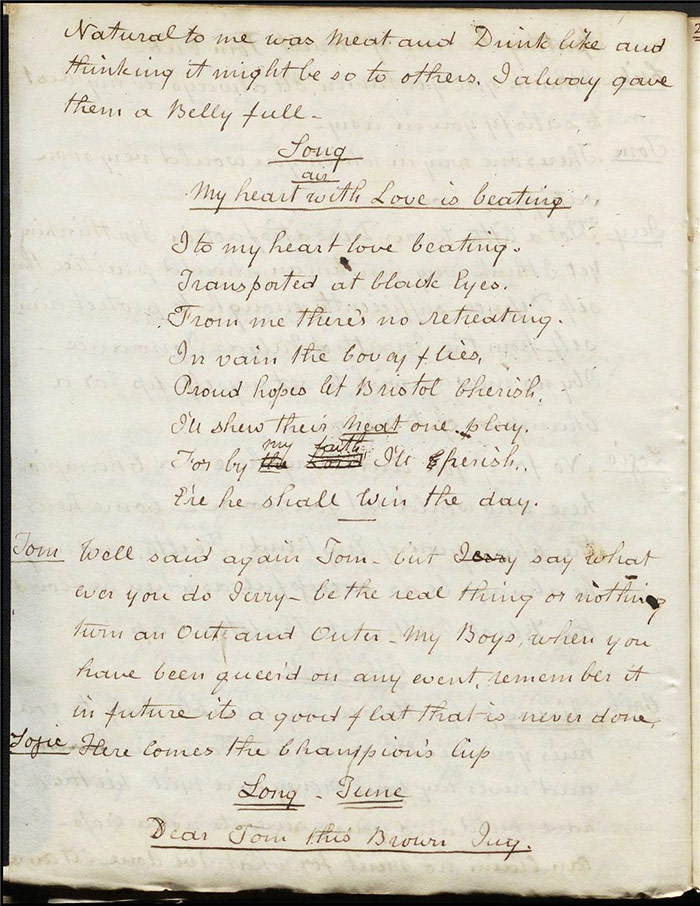

Act 2

Scene 1

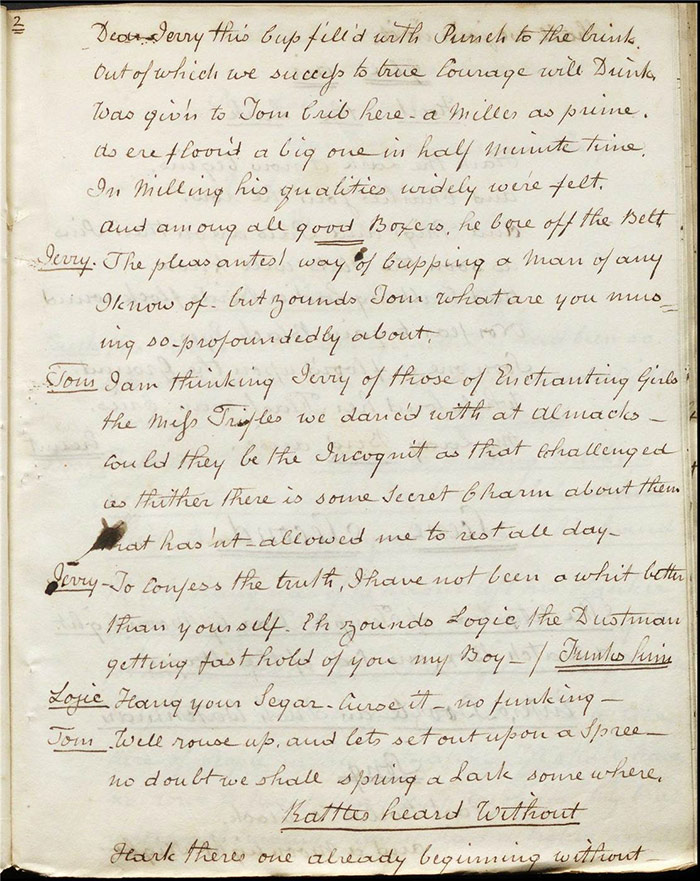

Tom, Jerry, and Bob are in the retired boxer Tom Cribb’s parlour having a drink. They cannot stop thinking about the girls they met earlier.

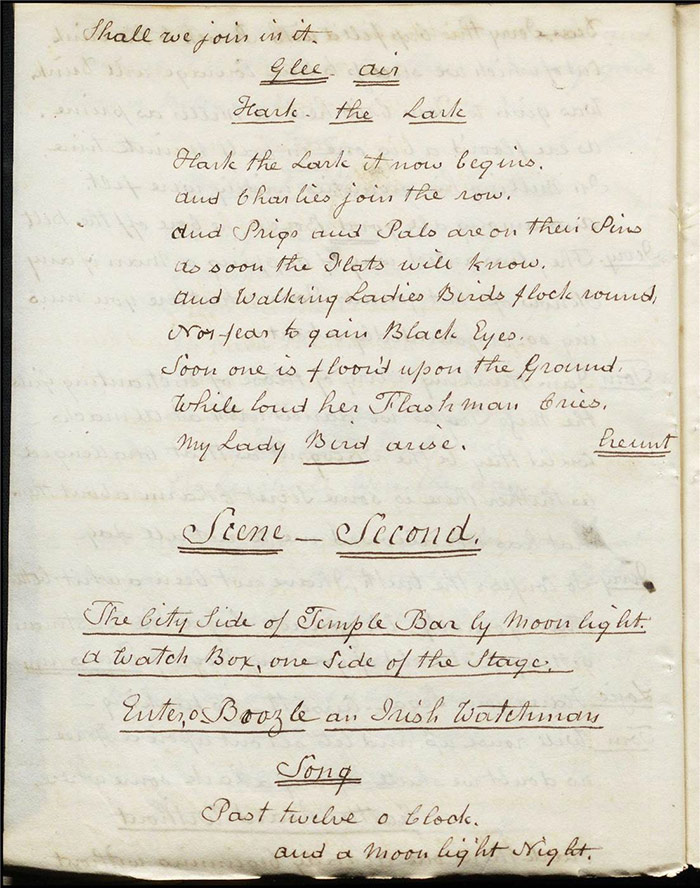

Scene 2

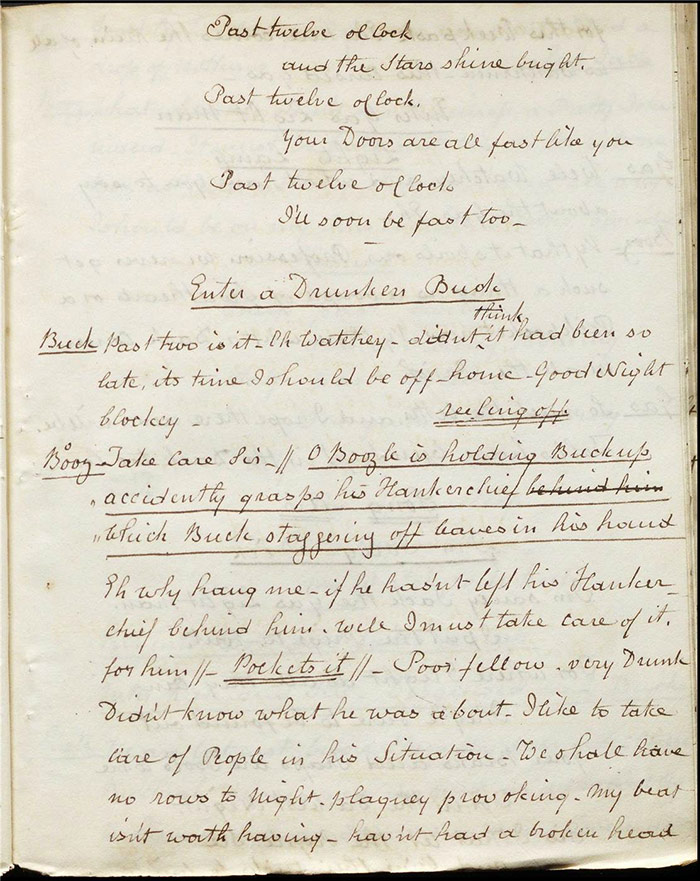

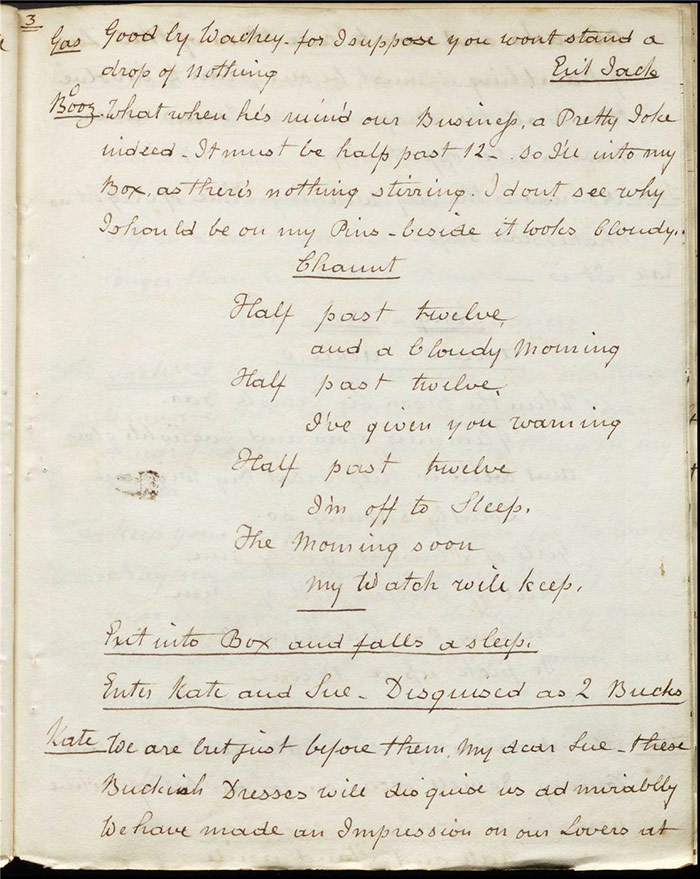

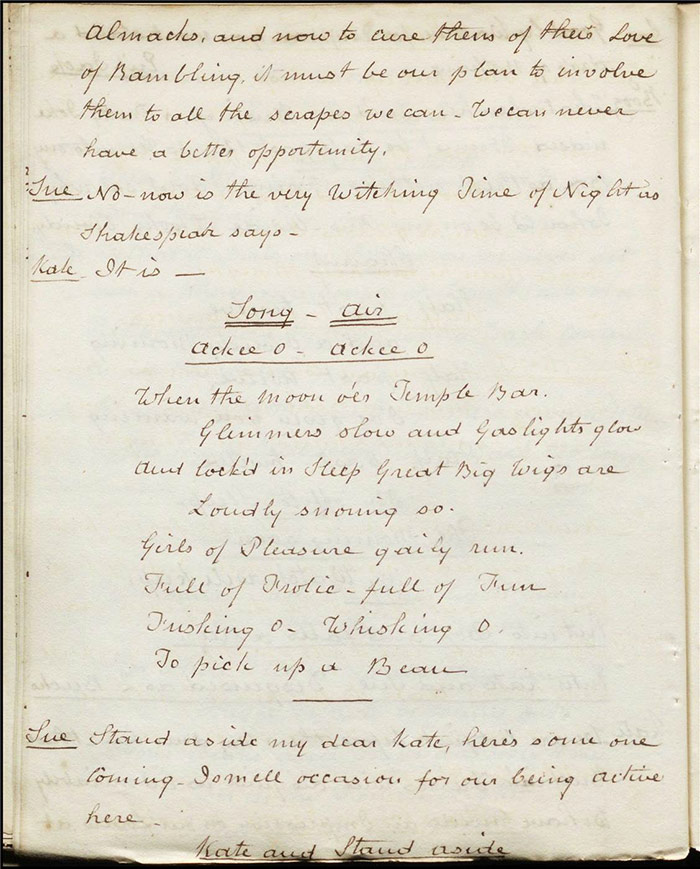

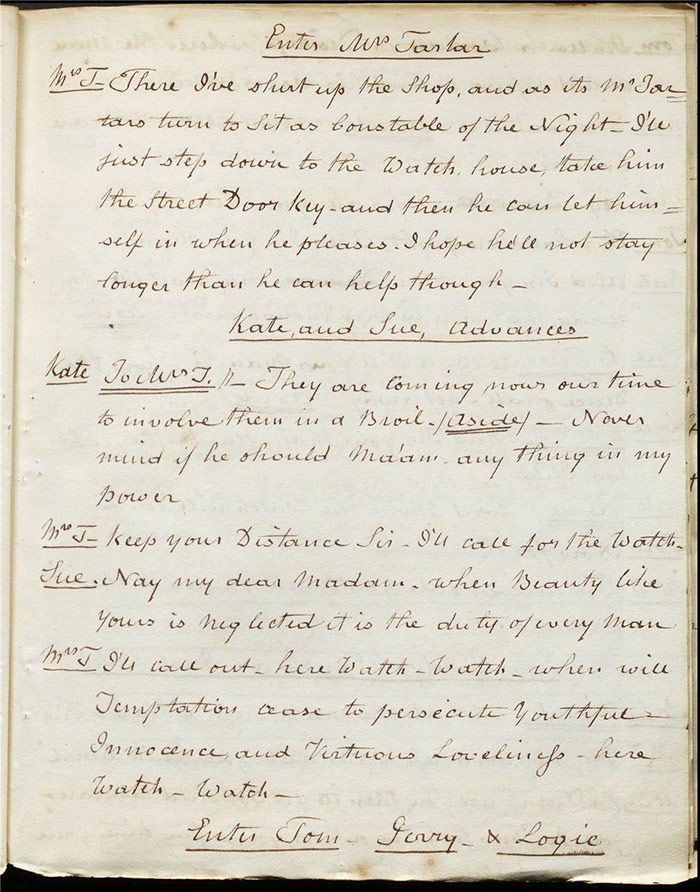

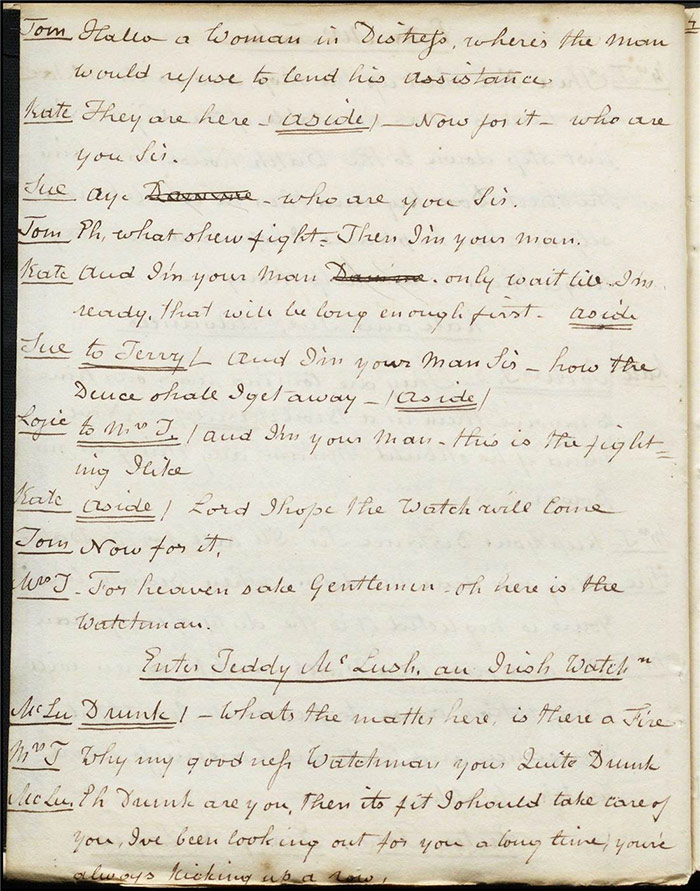

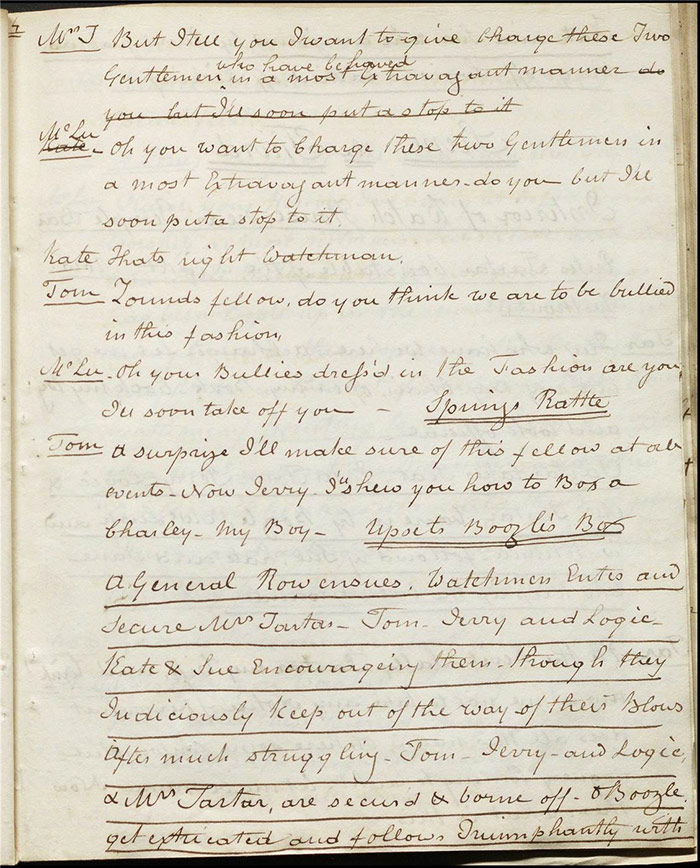

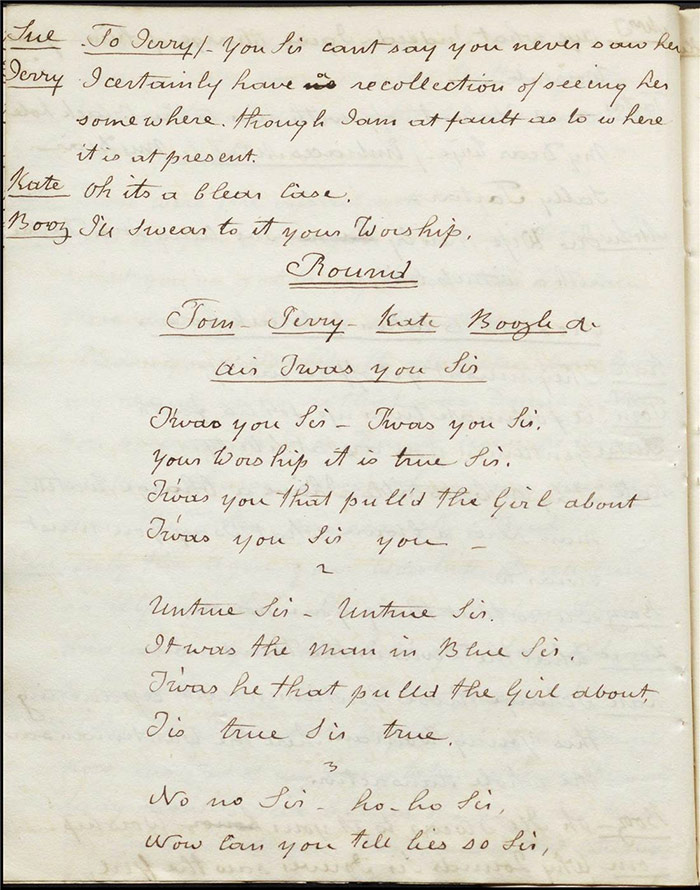

O’Boozle, an Irish watchman, is on the city side of Temple Bar and falls asleep in his watchbox. Enter Kate and Sue disguised as bucks as does Mrs Tartar who has just shut her shop. Kate and Sue spy the men approaching and decide to provoke a row by speaking suggestively to Mrs Tartar. She calls for the watch. Tom, Jerry, and Bob square up to the disguised women and then enters Teddy McLush, a drunk Irish watchman. A struggle ensues and O’Boozle’s box is knocked over. More watchmen enter and Tom, Jerry, Logic and Mrs tartar are secured and carried off. Kate and Sue follow.

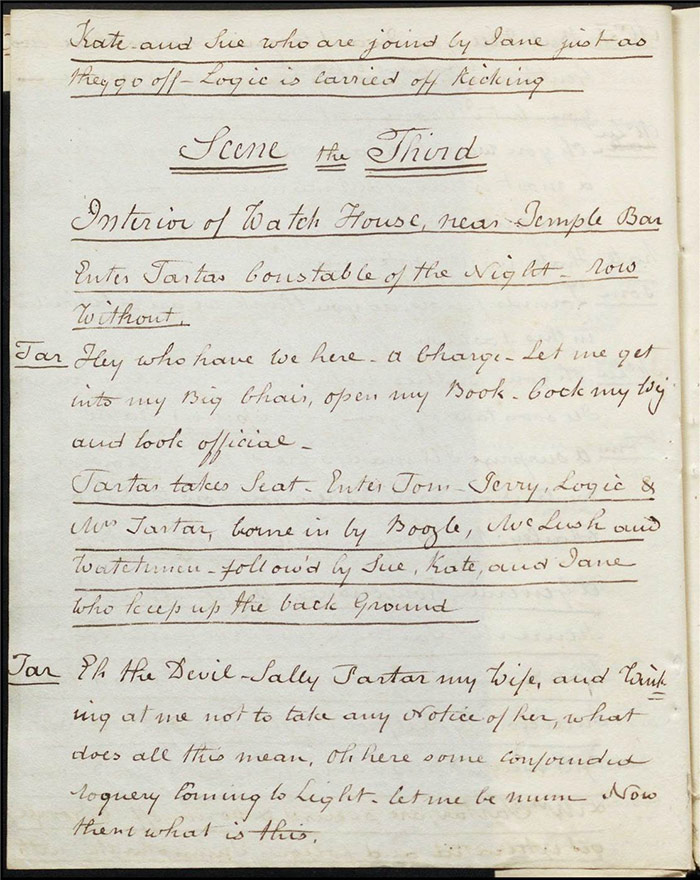

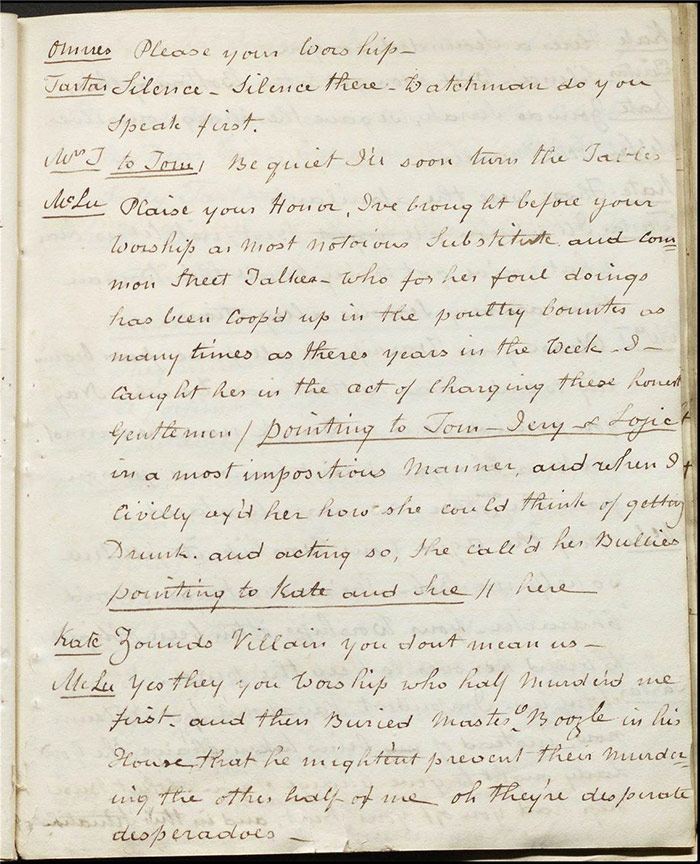

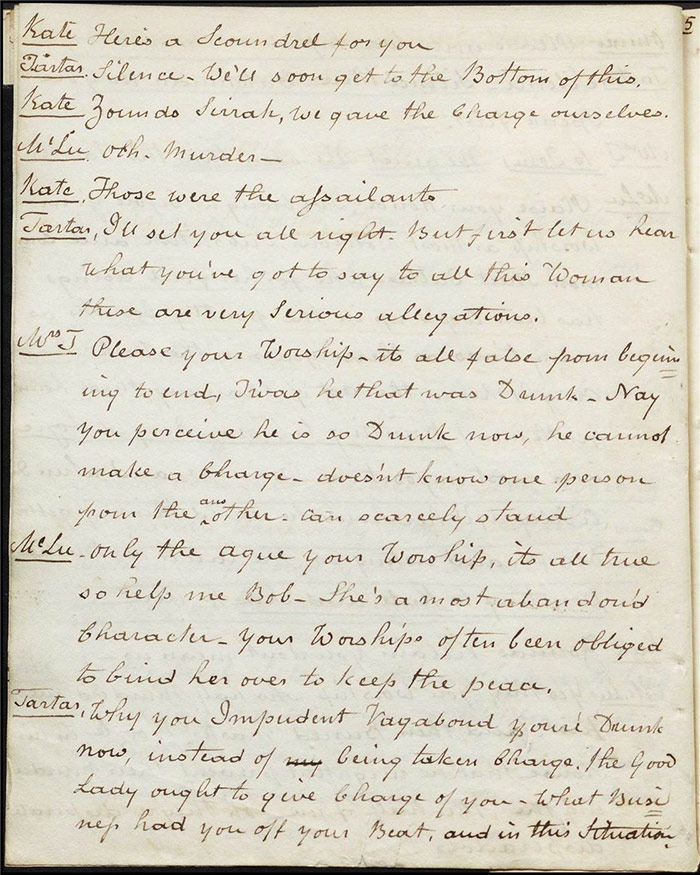

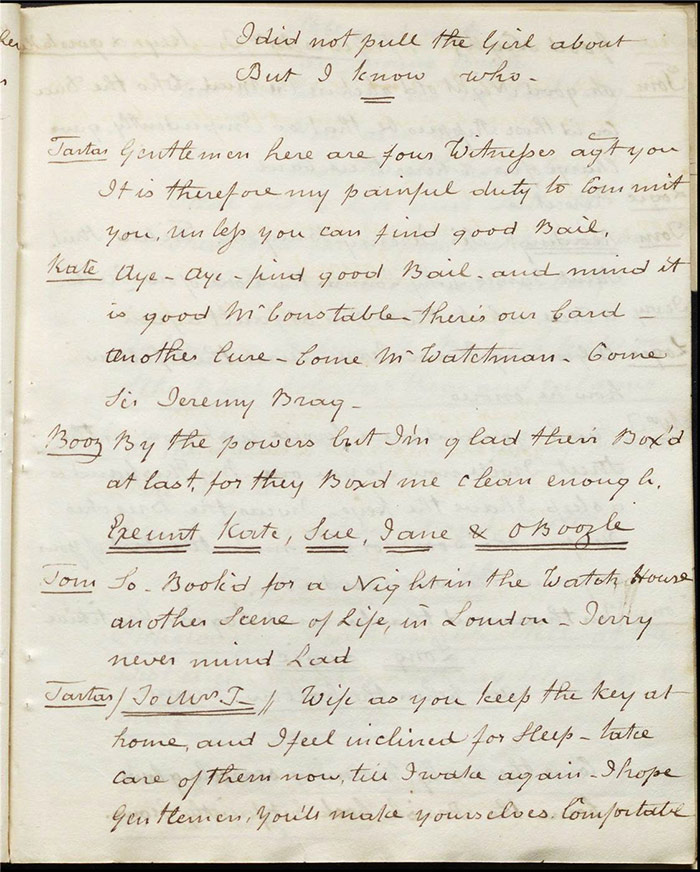

Scene 3

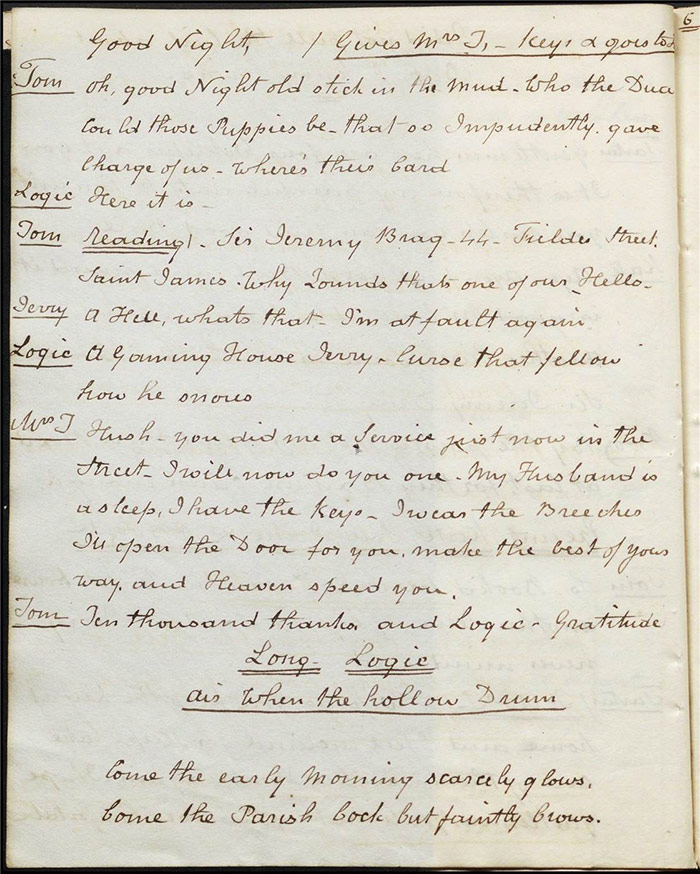

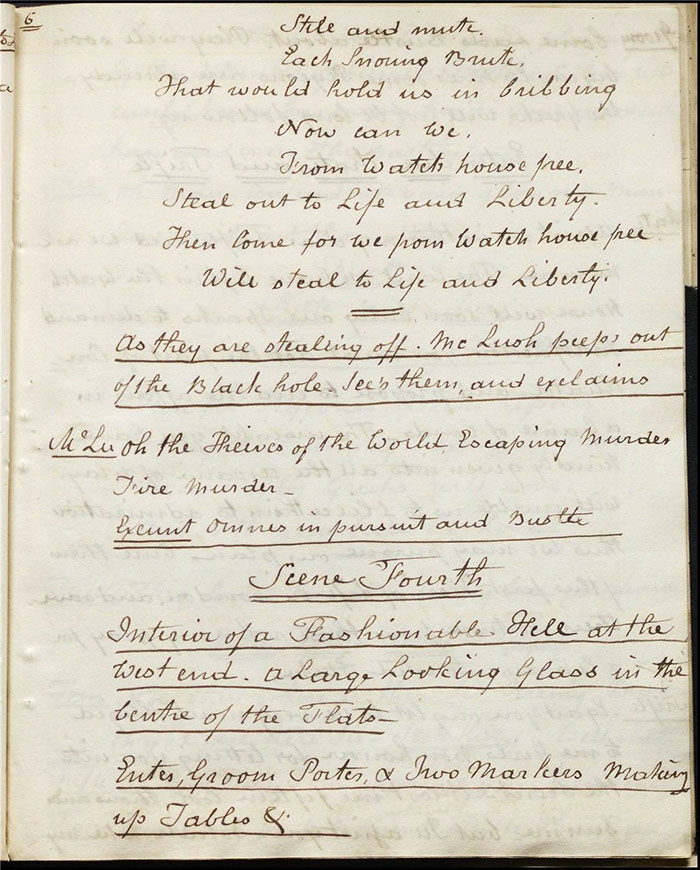

Tartar, the constable of the night is startled to find his wife being brought into the watch house. McLush, still drunk, gets all the charges wrong and is ordered to the black hole for being drunk on duty. Kate pays off O’Boozle to charge Tom, Jerry, and Bob with assaulting Sue. He duly supports her charge. They are remanded for the night and Kate and Sue exit, leaving the card of Sir Jeremy Brag who runs a gaming house. Mrs Tartar releases them when her husband sleeps.

Scene 4

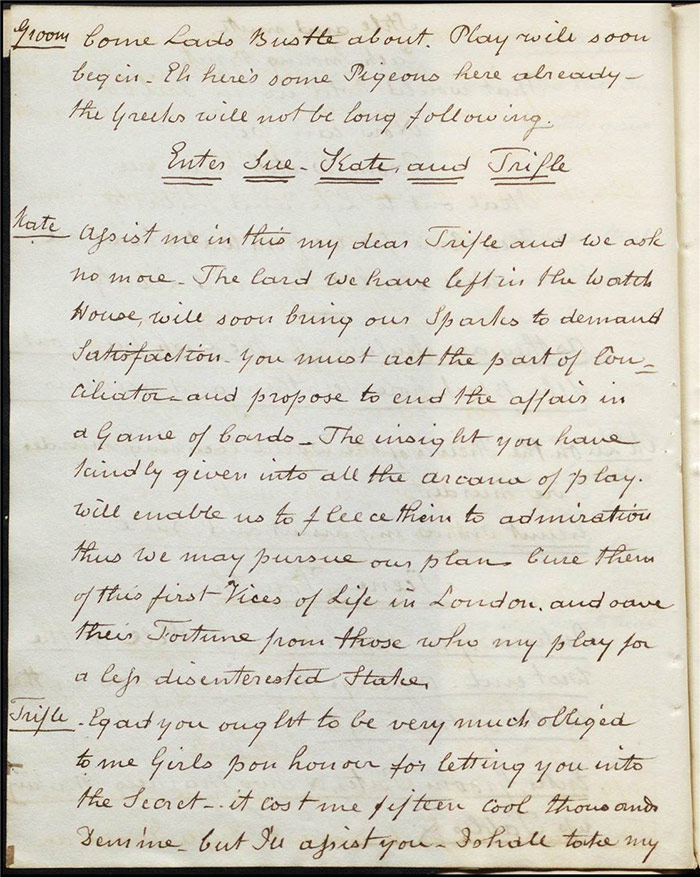

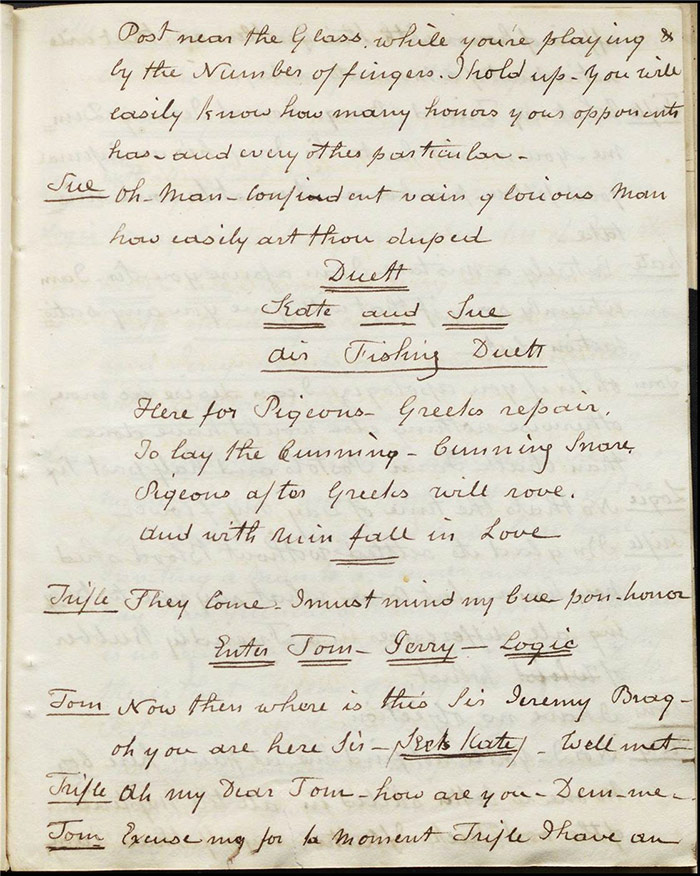

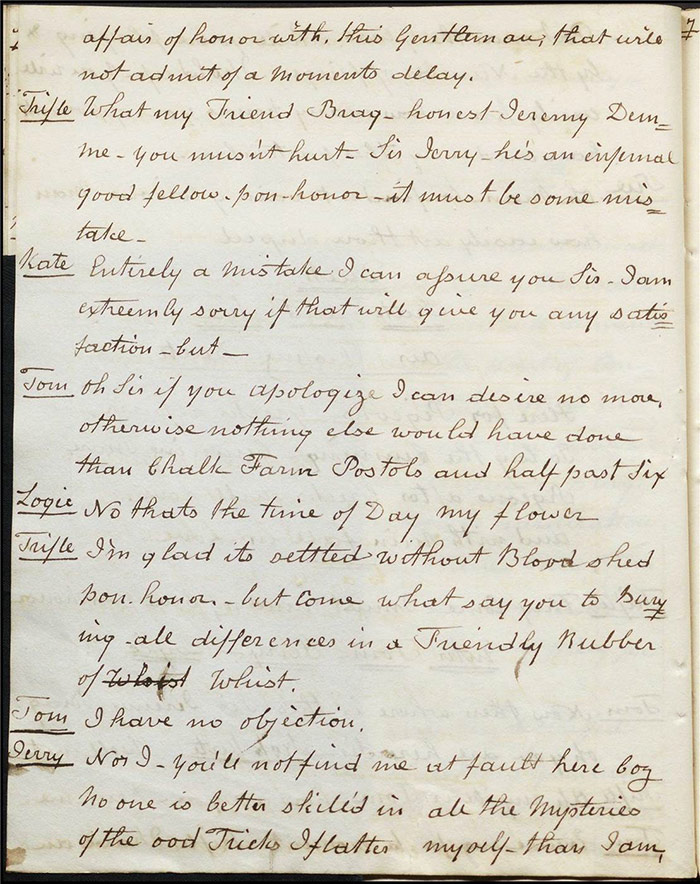

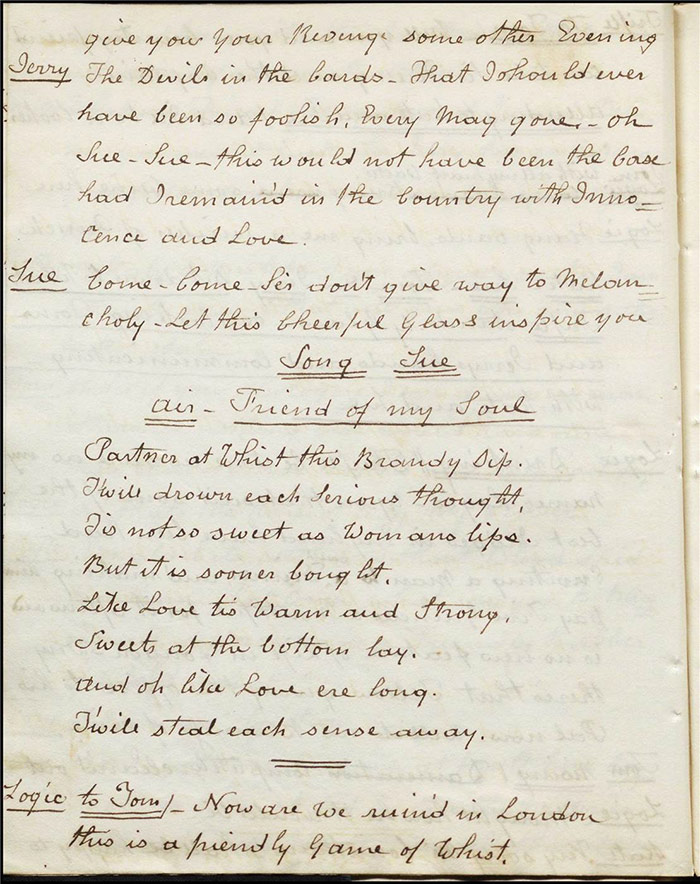

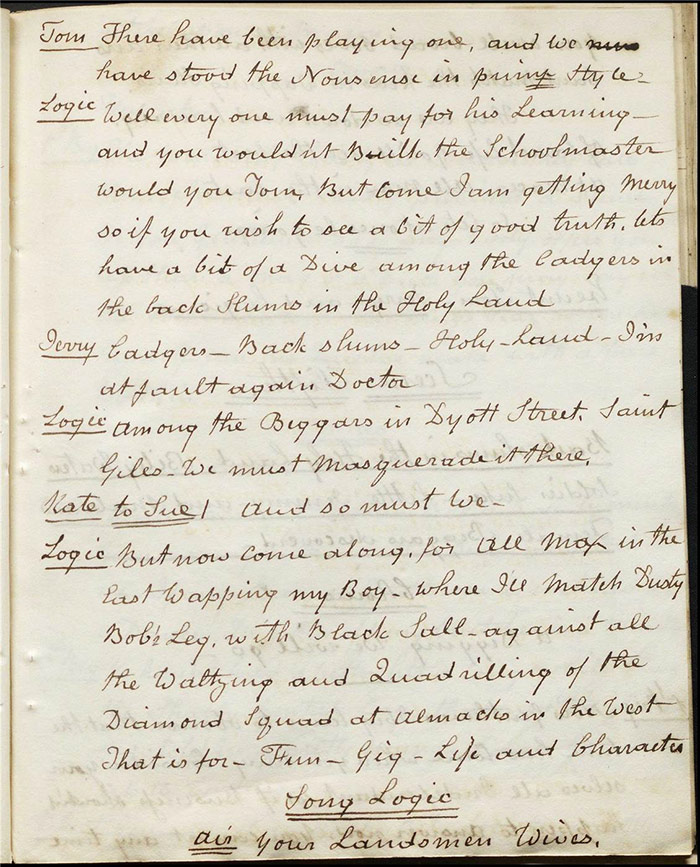

At a fashionable Hell (gaming house) in the west end, Sue, Kate and Trifle arrive. They have a plan to cheat the men at cards (using Trifle to spy using a looking glass and signal) so that they don’t lose their money to more nefarious London characters. Tom, Jerry, and Bob enter looking to settle a score with Jeremy Brag; Trifle and Kate assure them there’s been a mistake and invite them to play whist. Tom and Jerry are cleaned out and rue leaving their loves and the countryside. Logic suggest they dress up as beggars in the ‘Holy Land’ or Dyott Street.

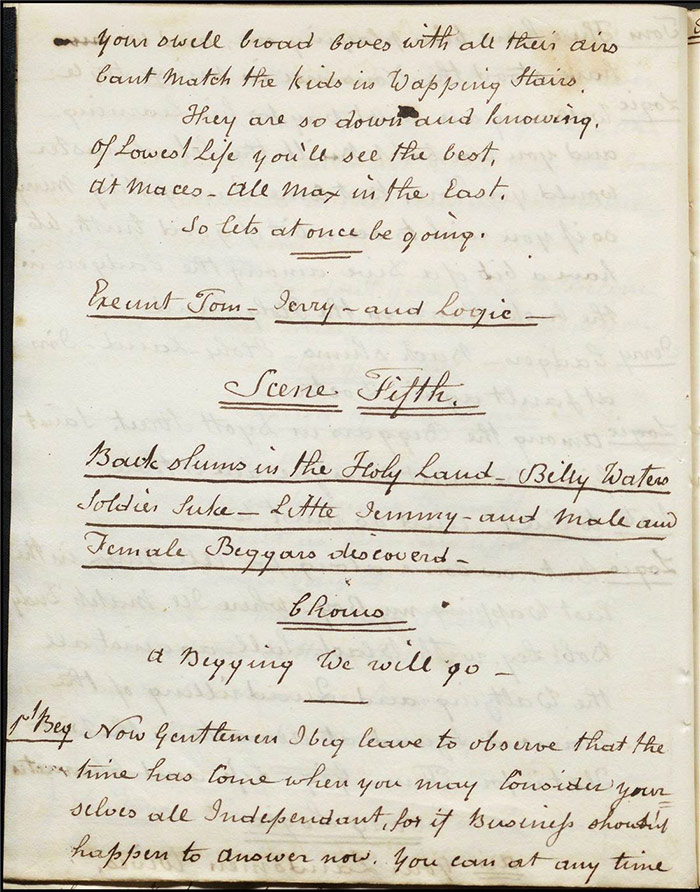

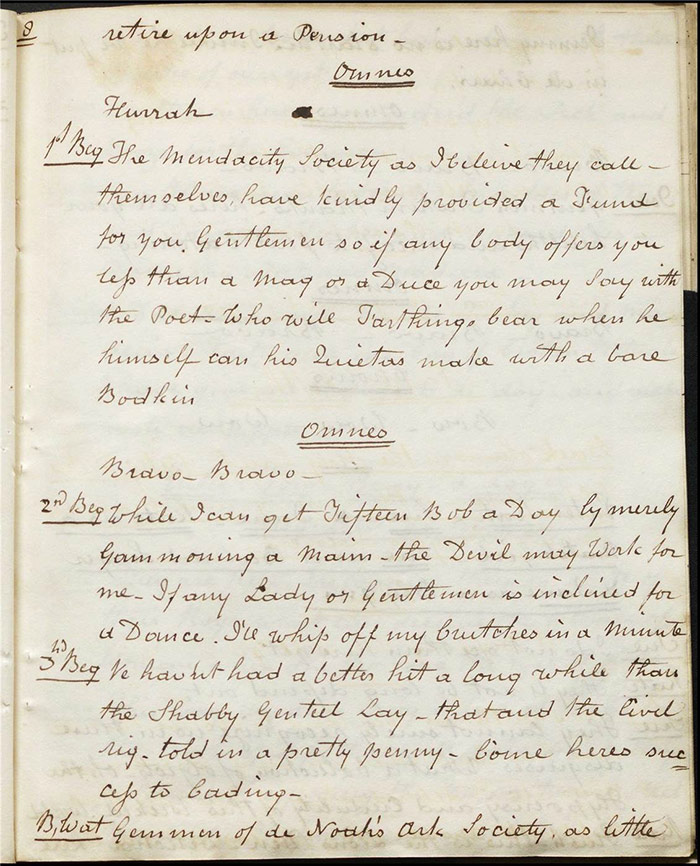

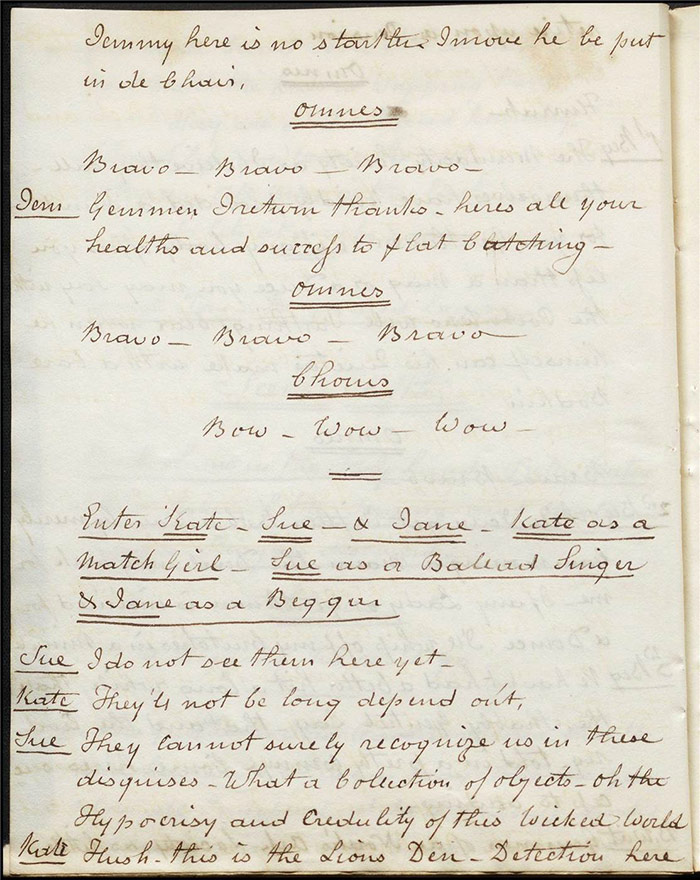

Scene 5

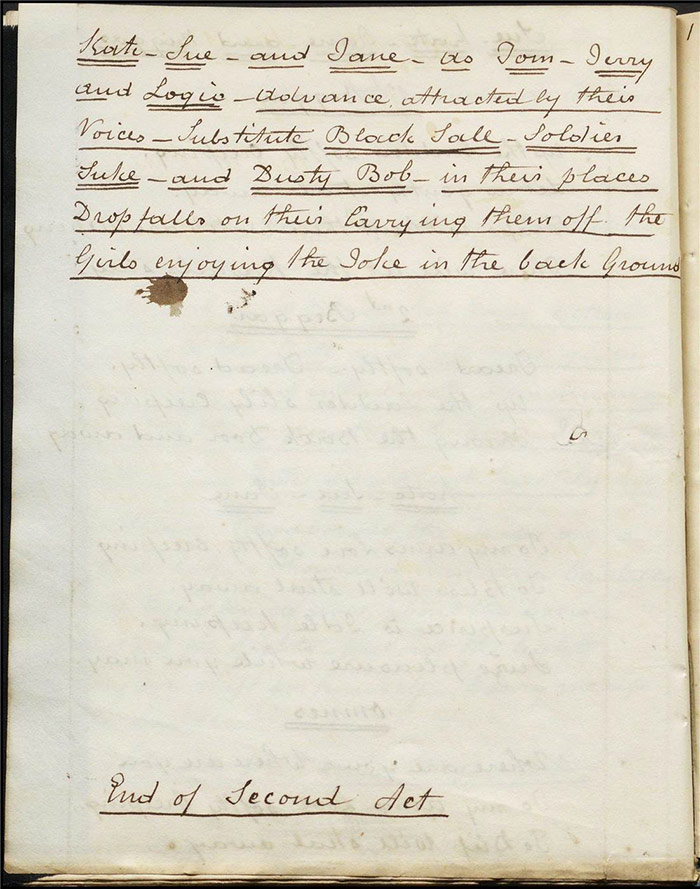

Kate (disguised as a match girl) and Sue (as a ballad singer) arrive among the beggars of Dyott Street. Tom, Jerry, and Logic arrive and the couples pair off although the men still don’t recognize their lovers. The constables arrive to shut down the beggars and in the confusion the women elude the arms of their lovers and skip off.

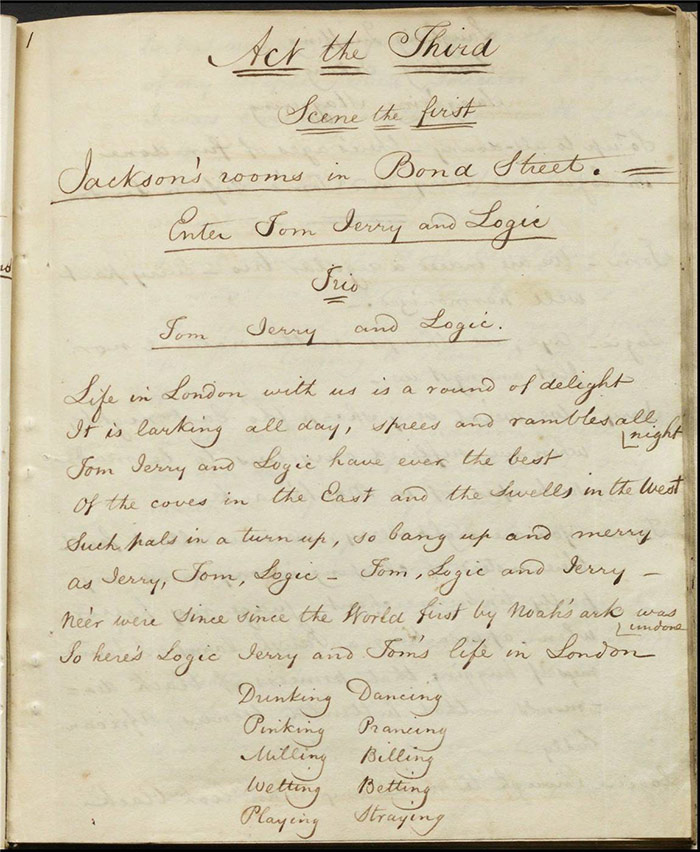

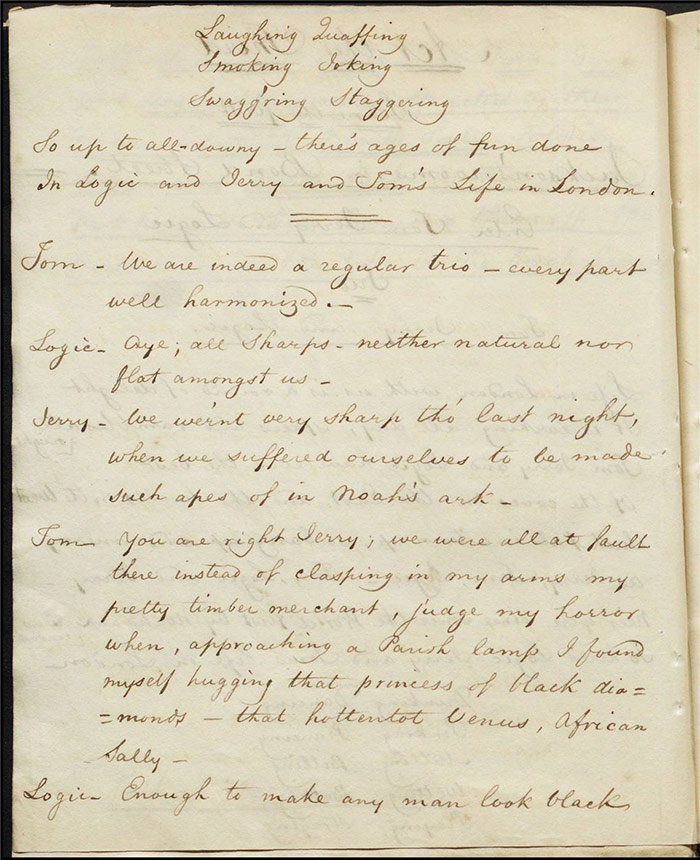

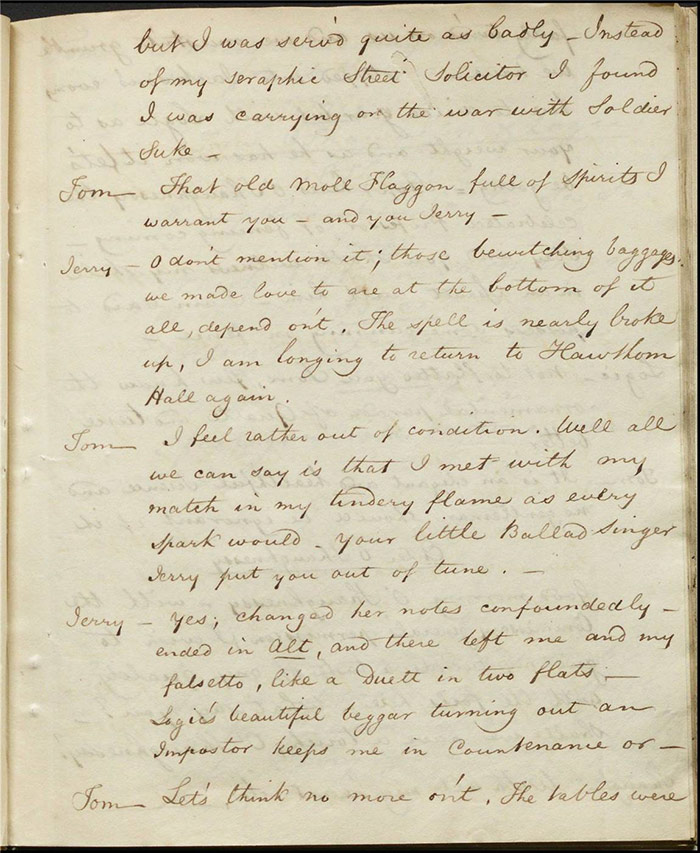

Act 3

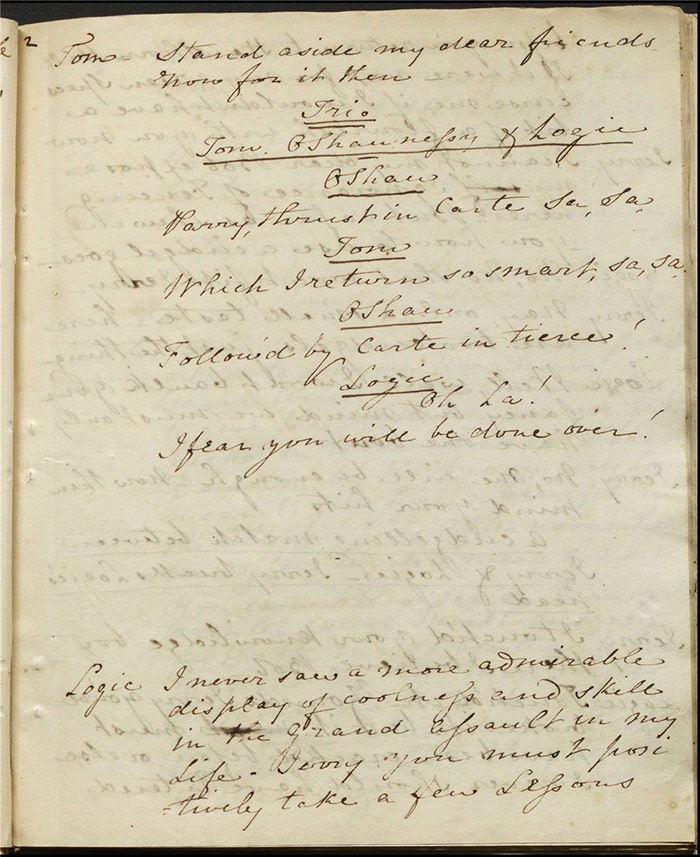

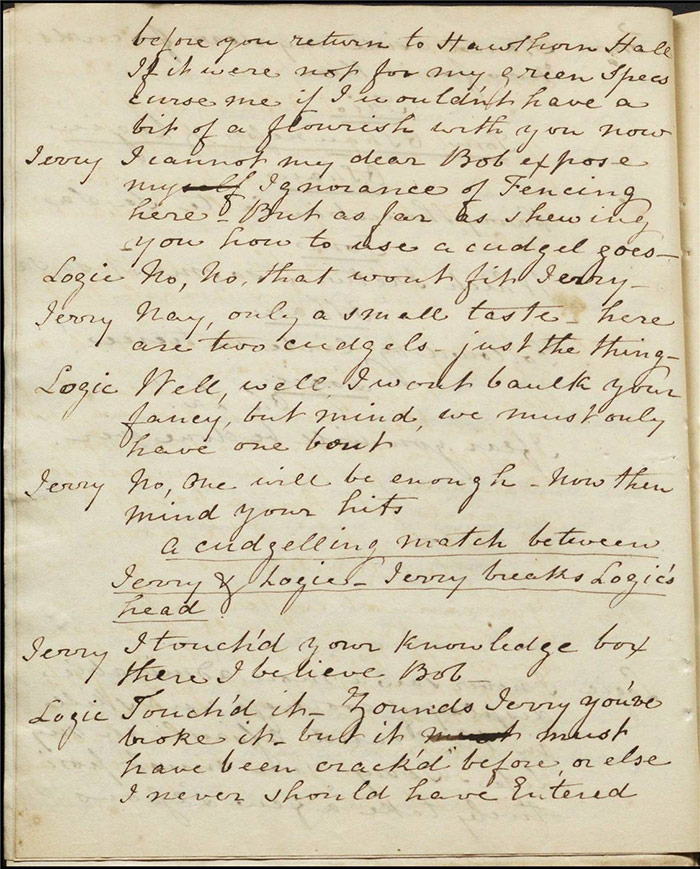

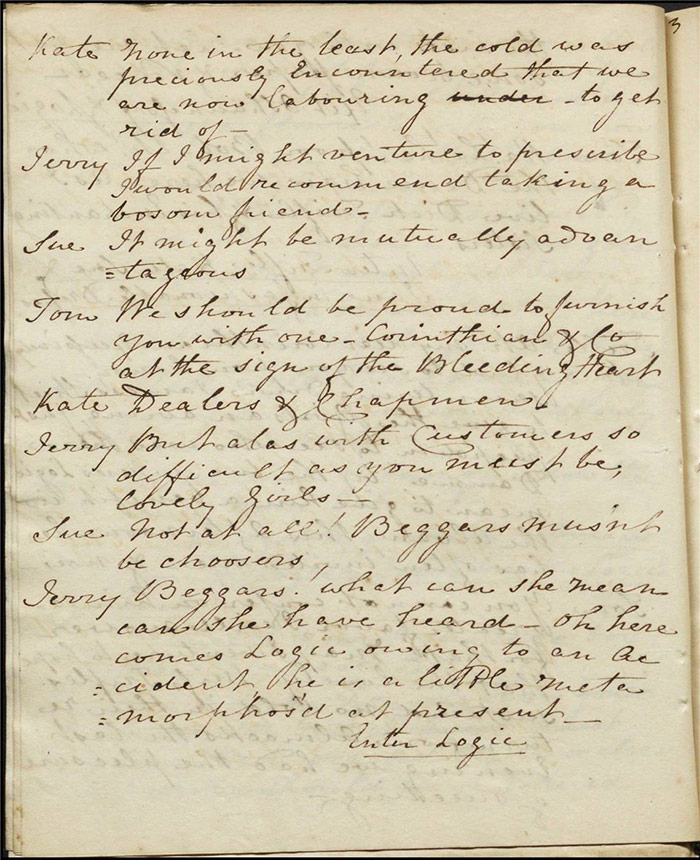

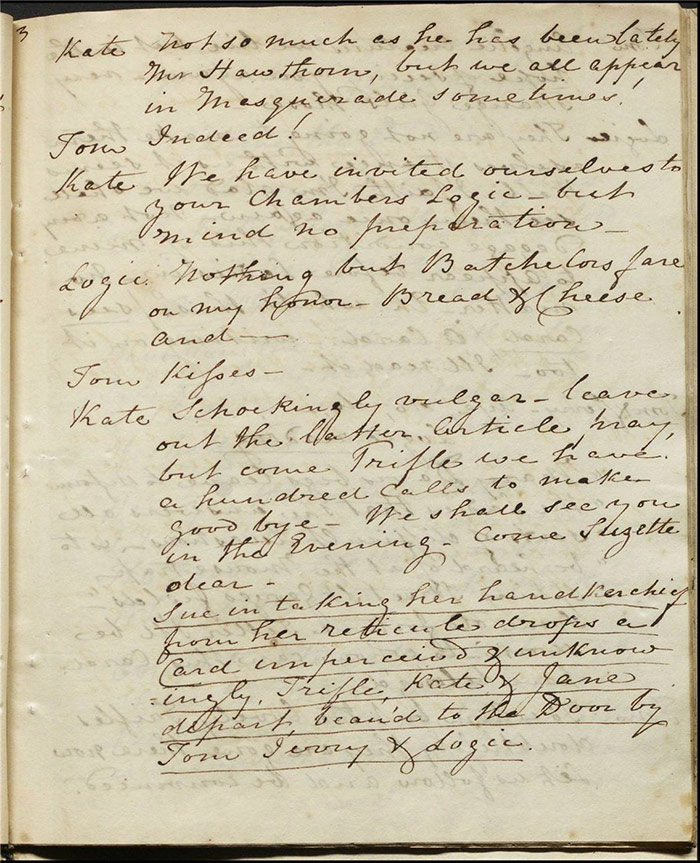

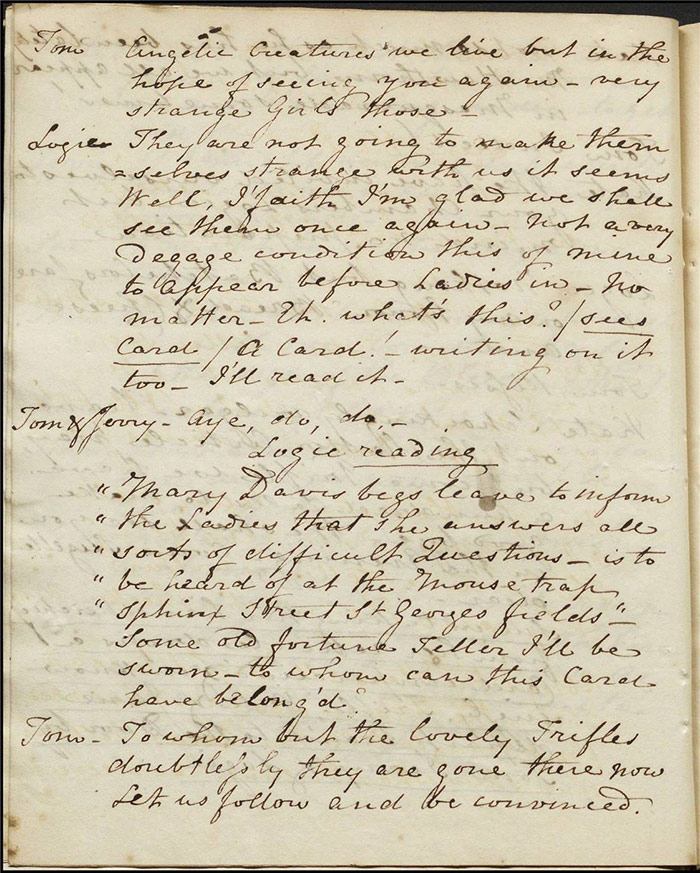

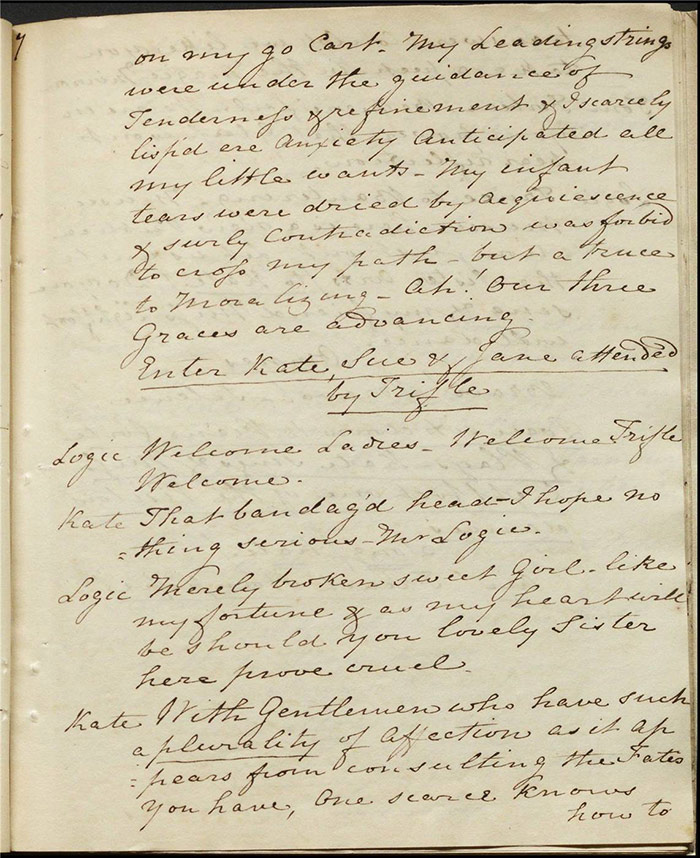

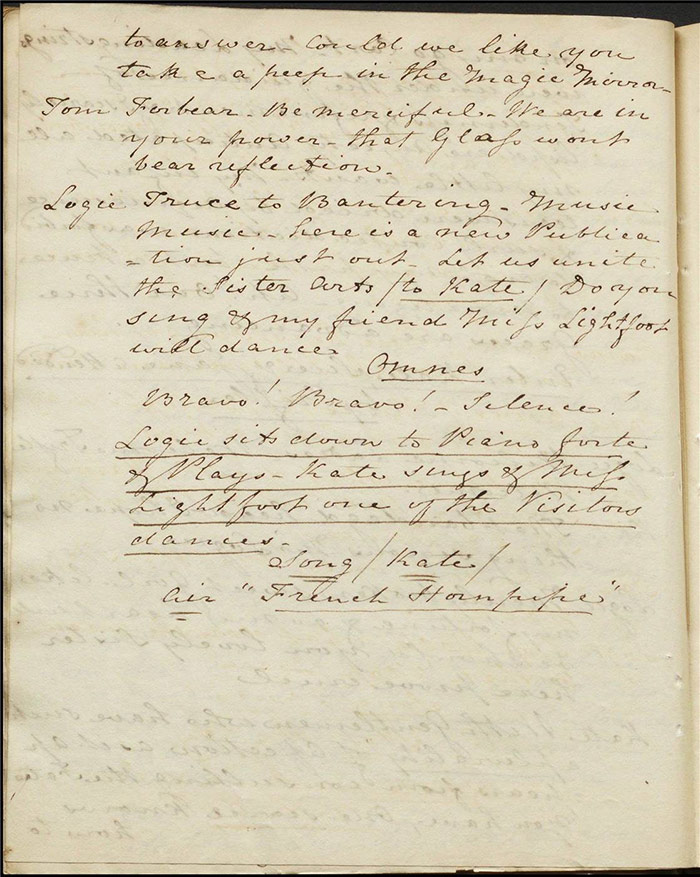

Tom, Jerry, and Logic are found in Jackson’s boxing academy on Bond Street. Tom decides to tackle O’Shaughnessy, a professor of fencing, to show his friends what he can do. Jerry and Logic then decides to have a cudgeling match. Bob takes a blow to his head. Trifle and the ladies enter. They all agree to meet later and the ladies depart. As they leave, they drop a card for a fortune teller. The men decide to go there as well.

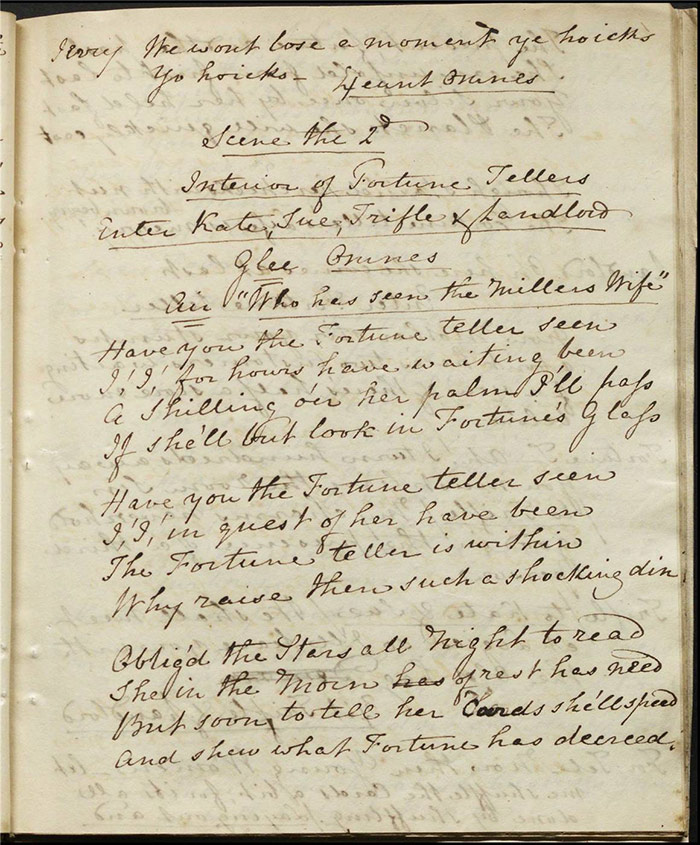

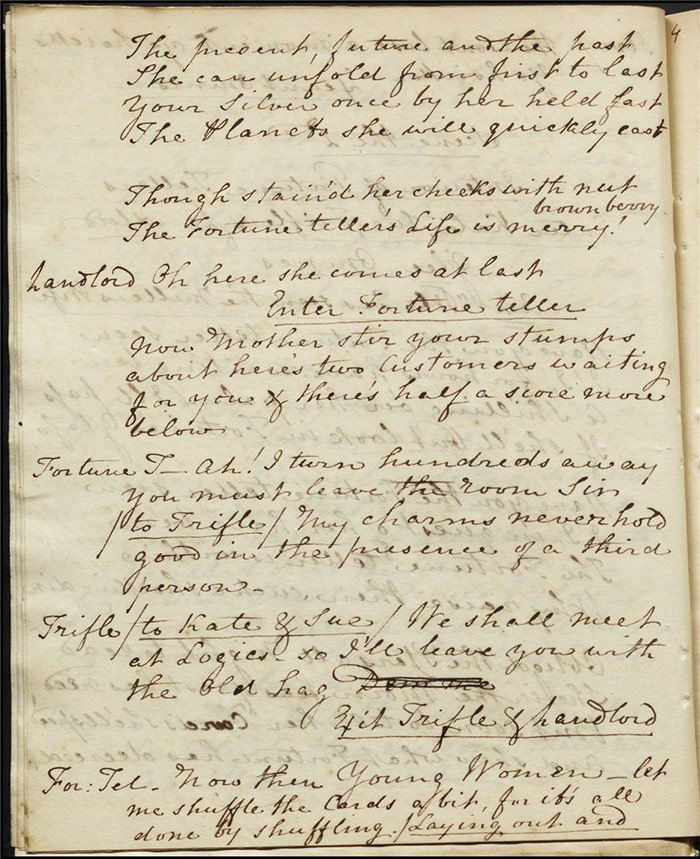

Scene 2

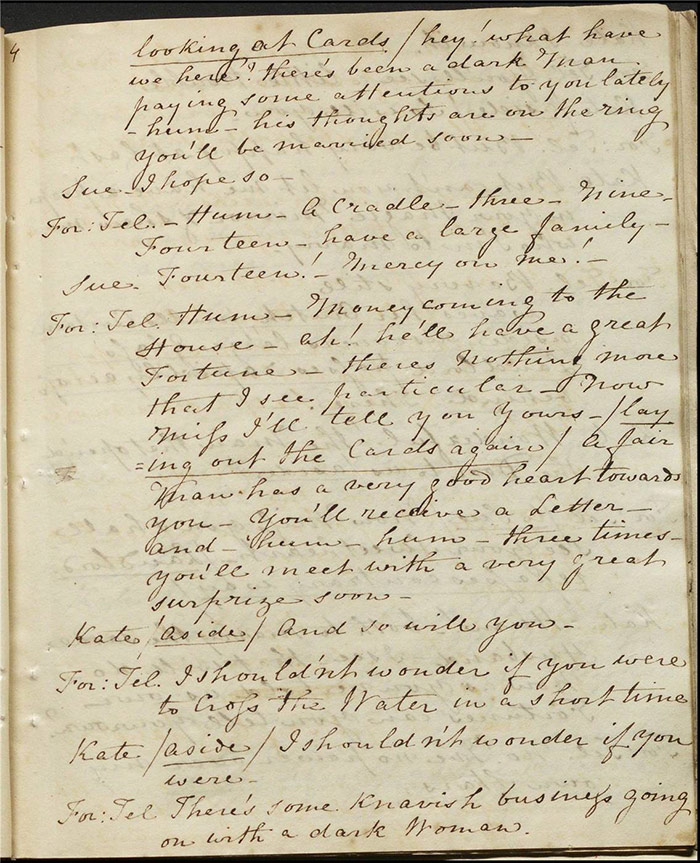

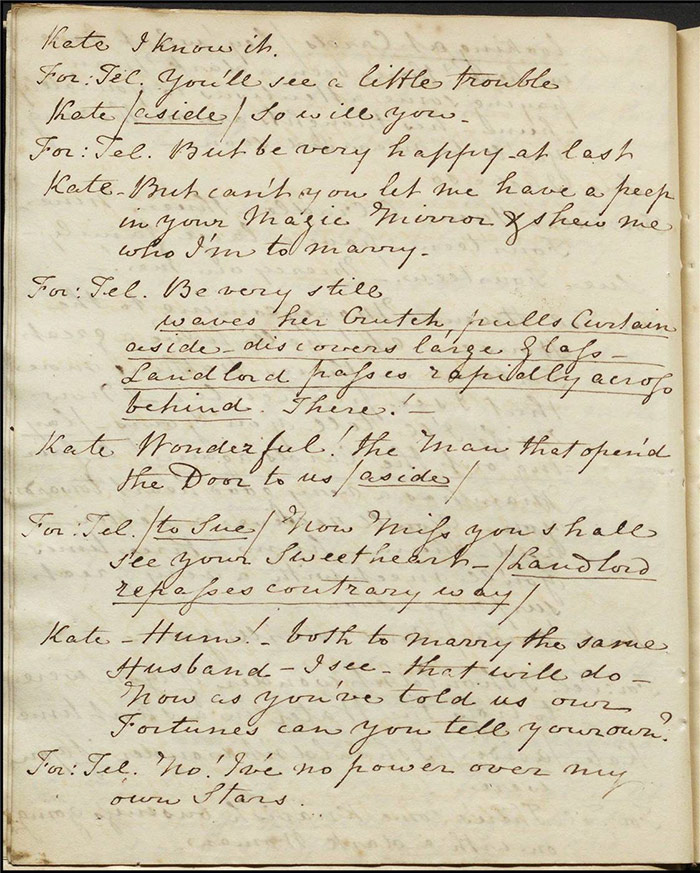

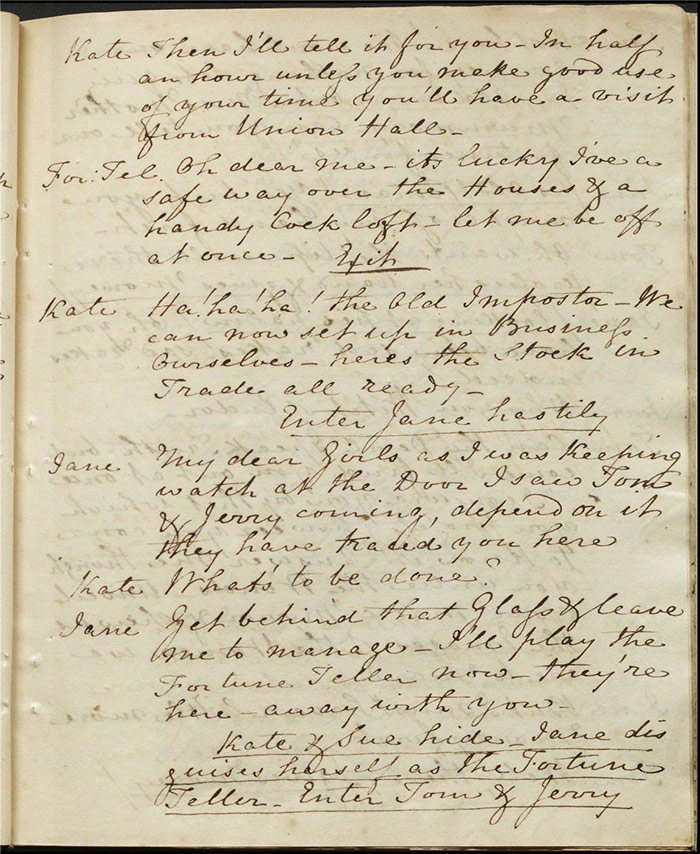

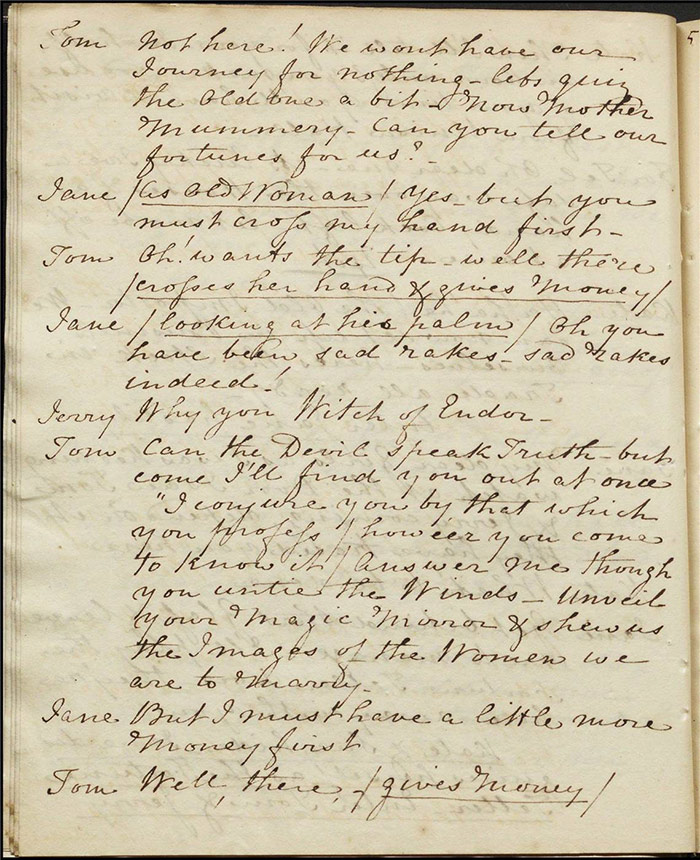

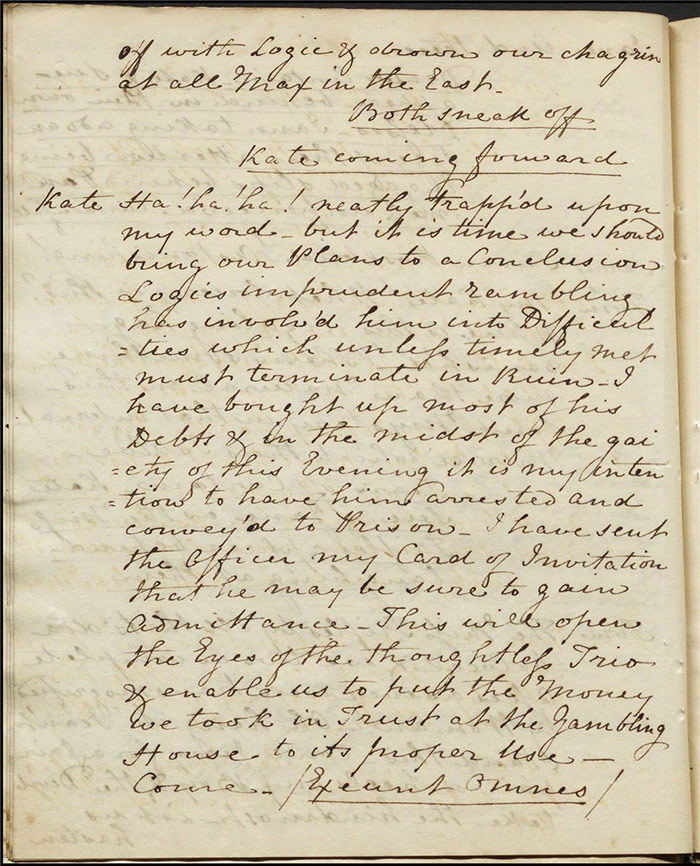

Kate and Sue consult a fortune teller who predicts the usual nonsense. They scare her off by telling her the police are on the way and they then set up Jane as the fortune teller as Tom and Jerry arrive. The ladies have some fun with them and Tom and Jerry slink off. Kate reveals that she has bought up Logic’s debts and plans to have him arrested to teach them all a lesson.

Scene 3

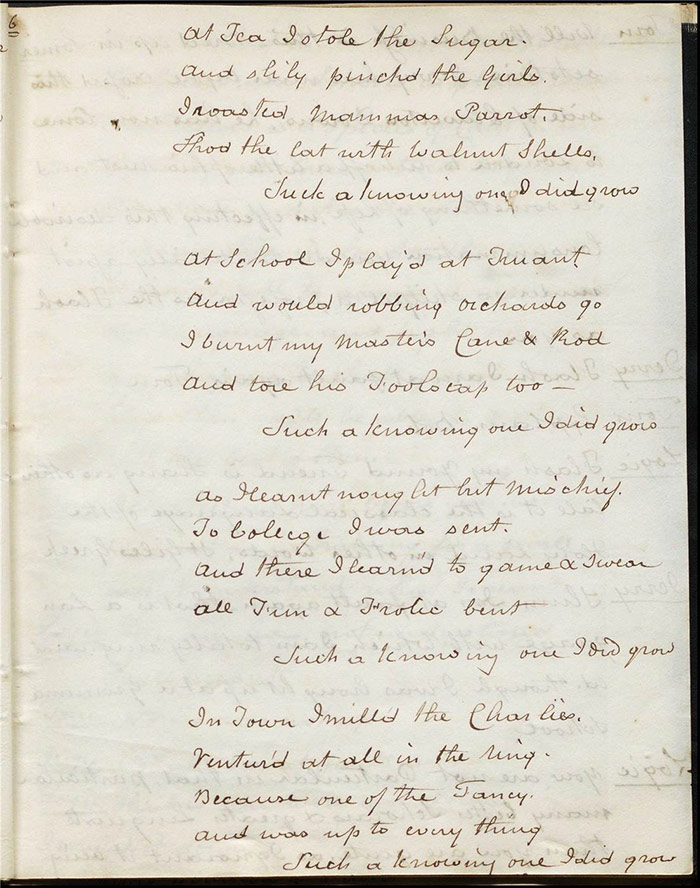

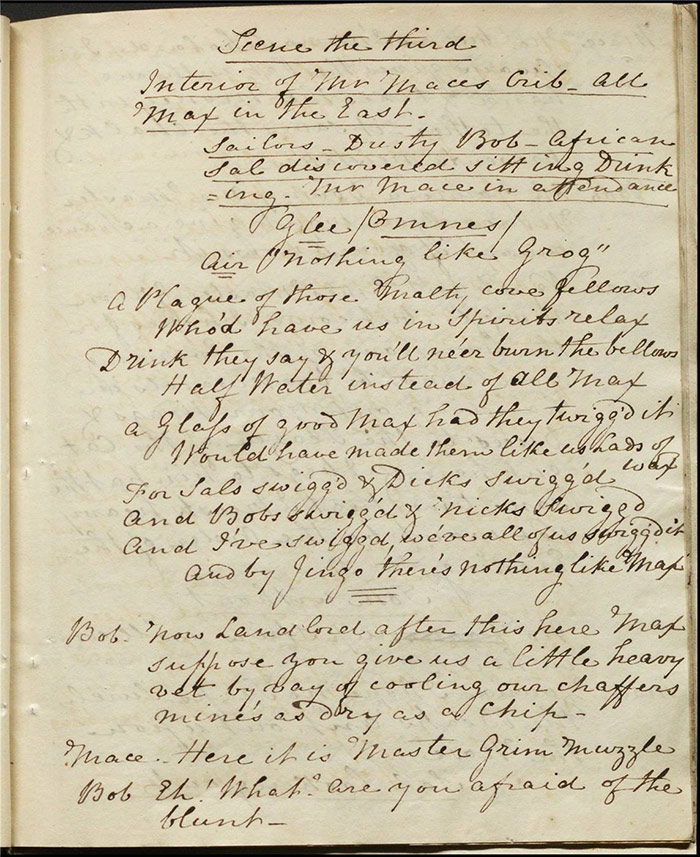

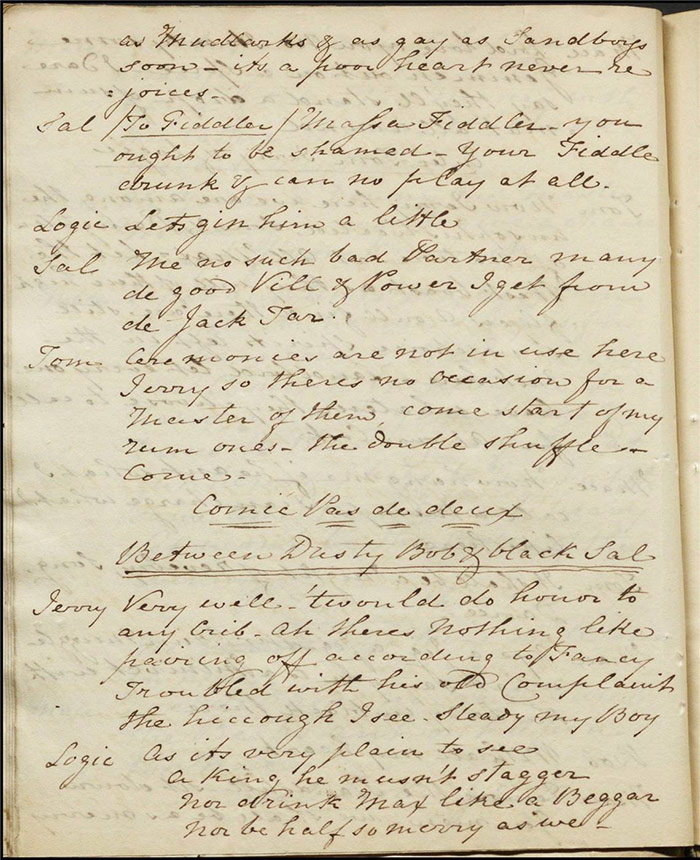

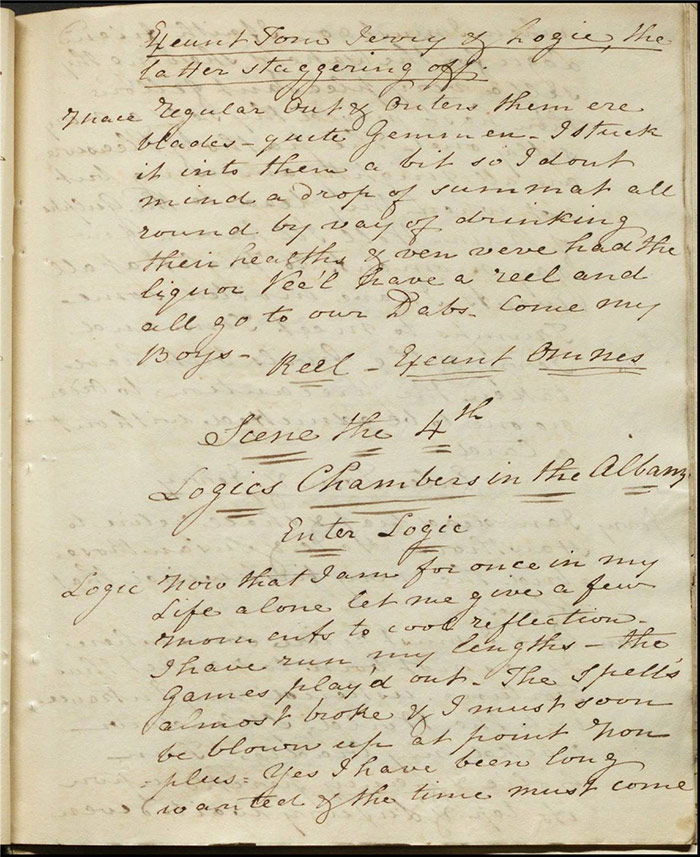

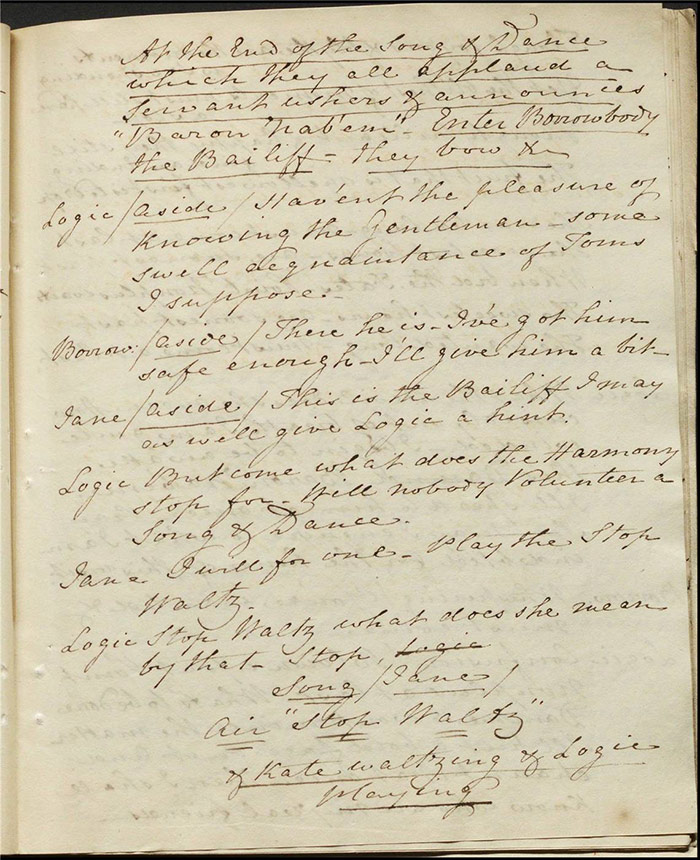

At Mr Mace’s Crib (also known as “All Max” [gin] in the East), the men partake in a scene of drinking, singing, and dancing.

Scene 4

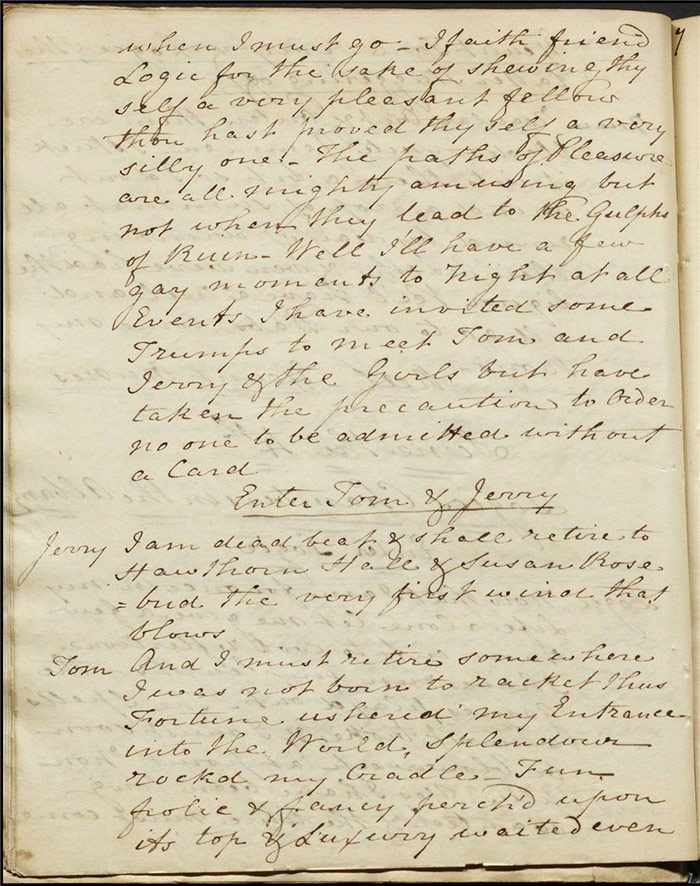

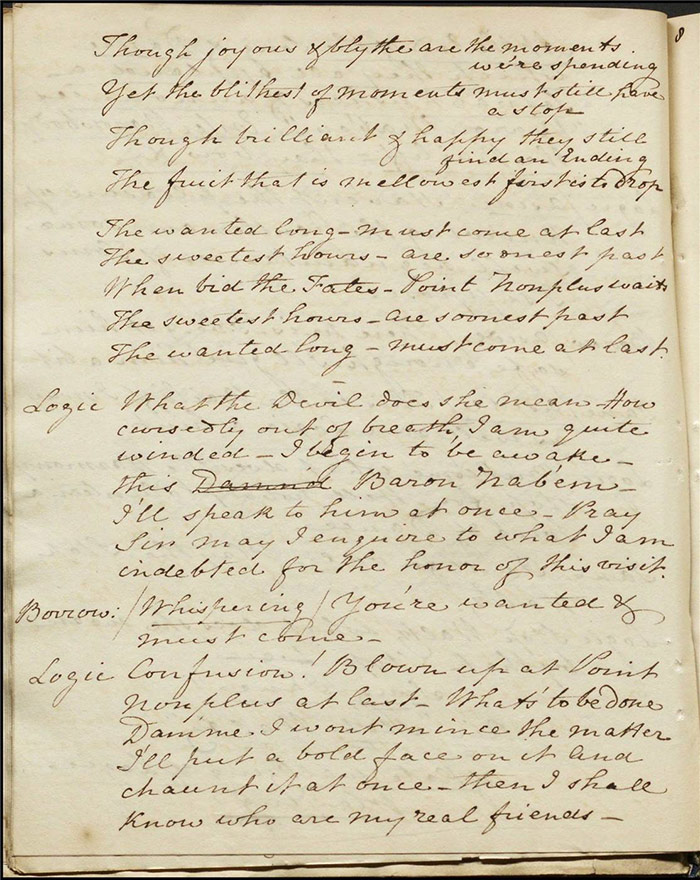

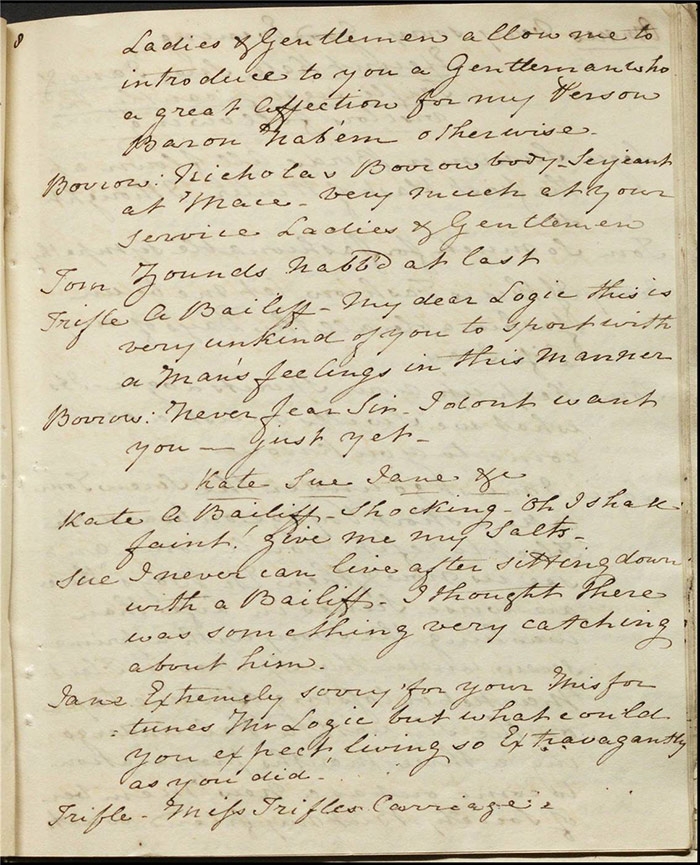

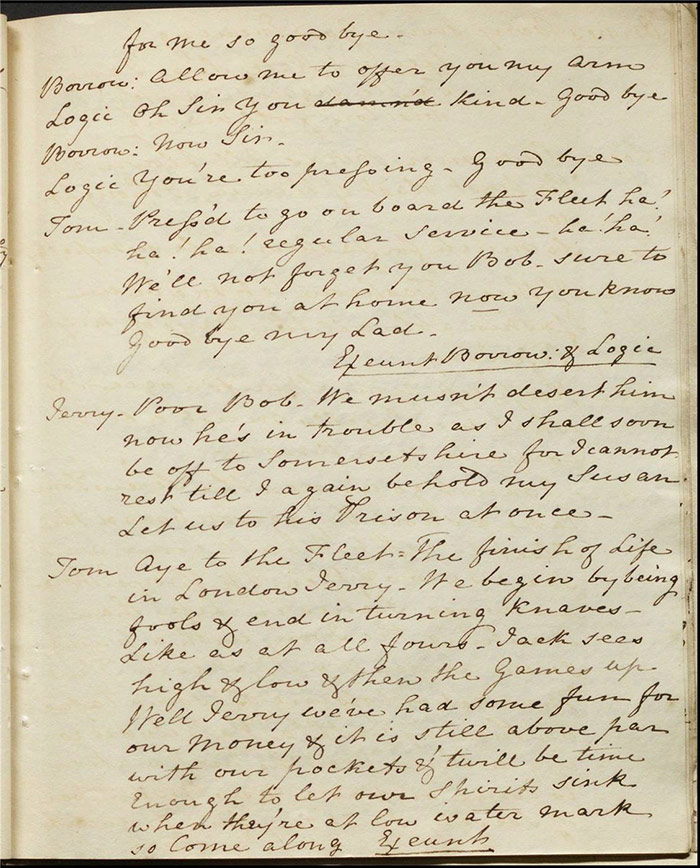

At Logic’s chambers, the three men receive the Trifles and entertain them. Borrowbody the bailiff comes and arrests Bob. Tom and Jerry follow their friend to the Fleet prison in order to help him.

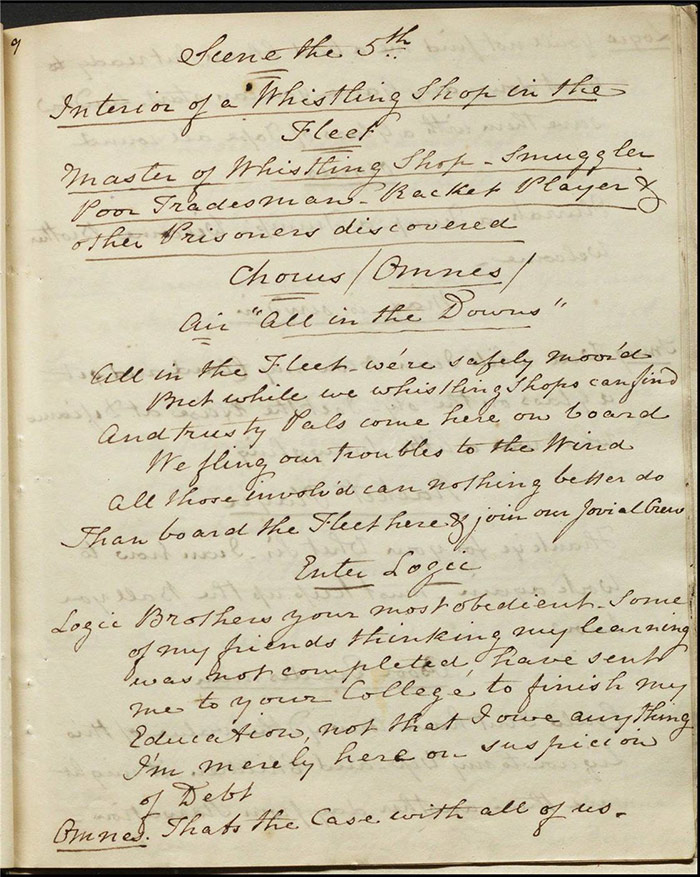

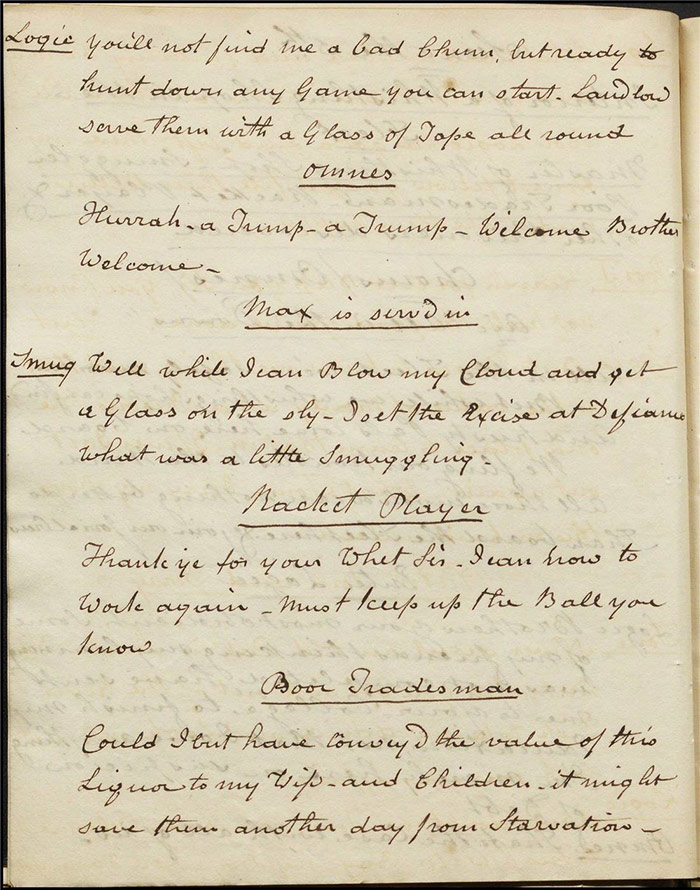

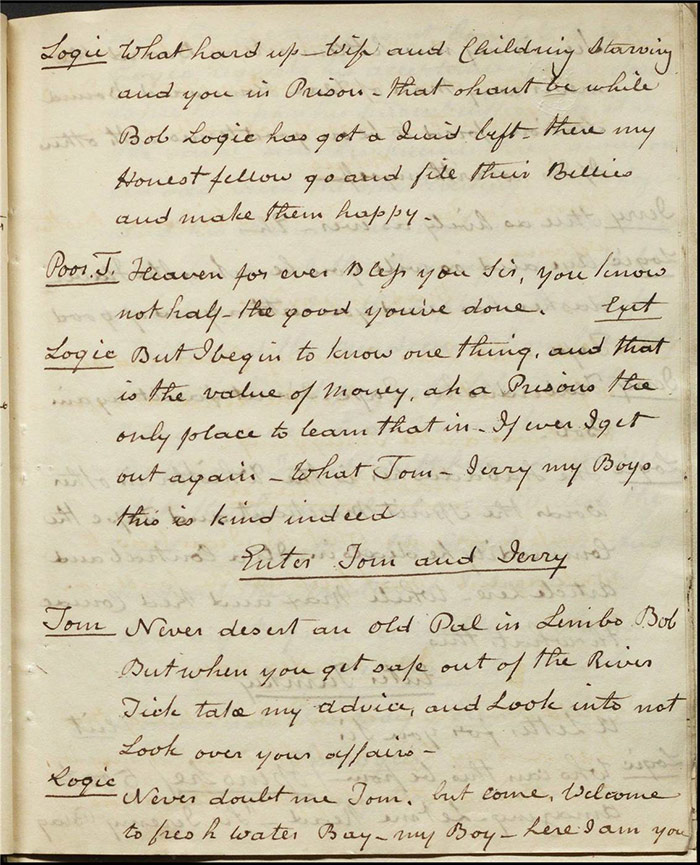

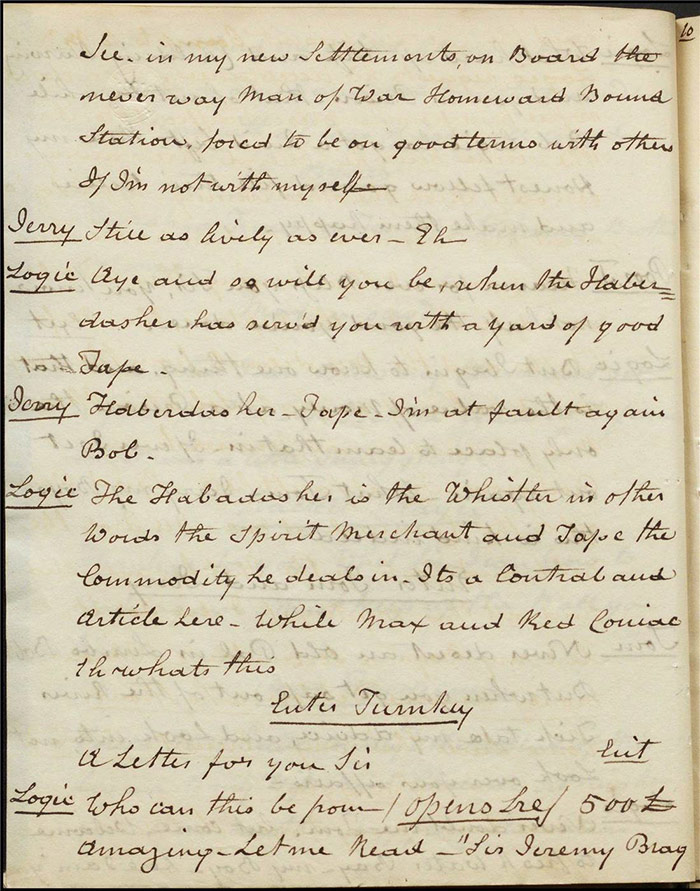

Scene 5

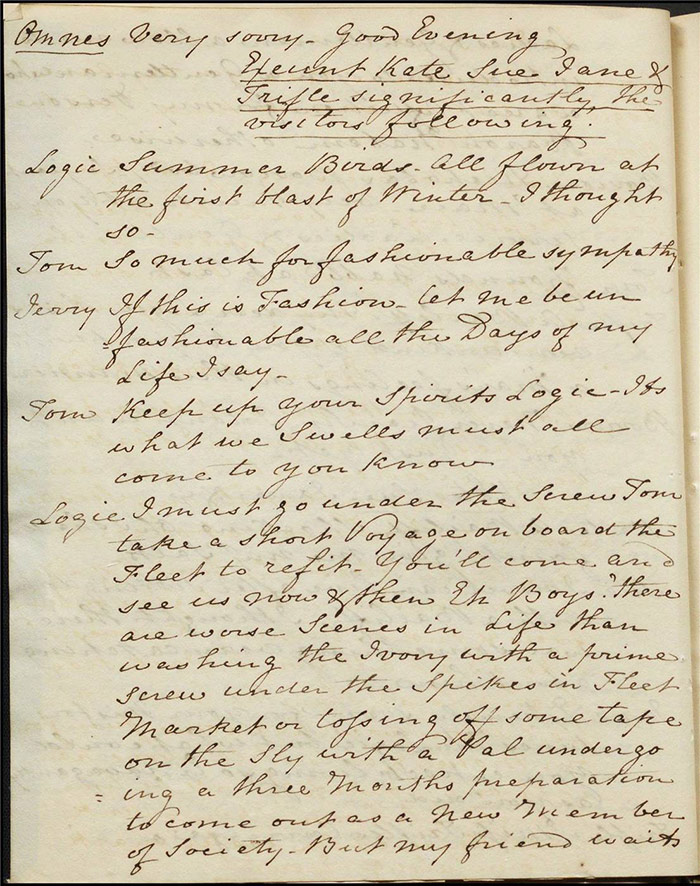

In a Fleet prison whistling shop (where liquor could be purchased), Tom and Jerry arrive. Bob receives a letter containing £500 from Sir Jeremy Brag to pay off his debts and an invitation to meet him and the Trifles at the Venetian carnival.

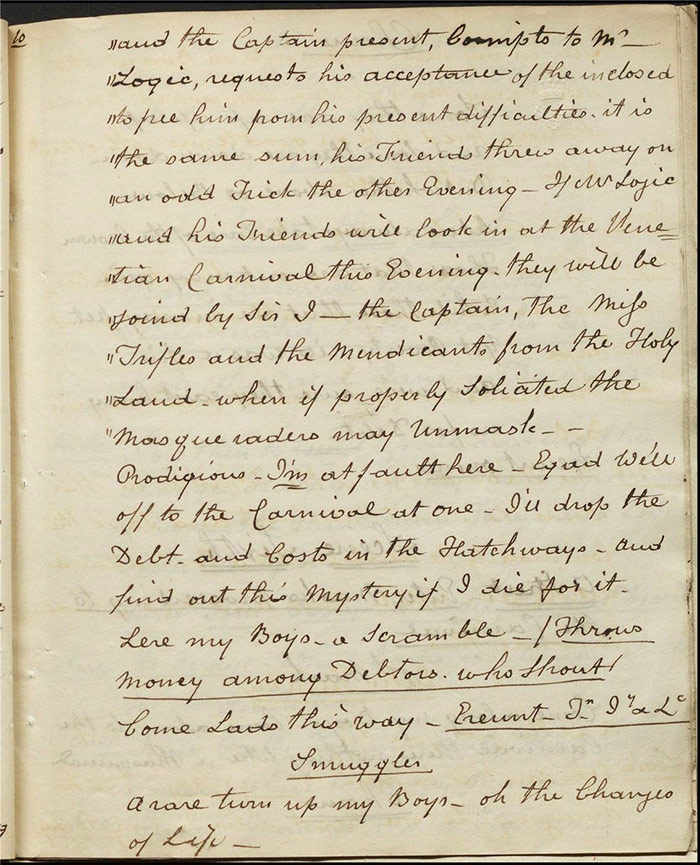

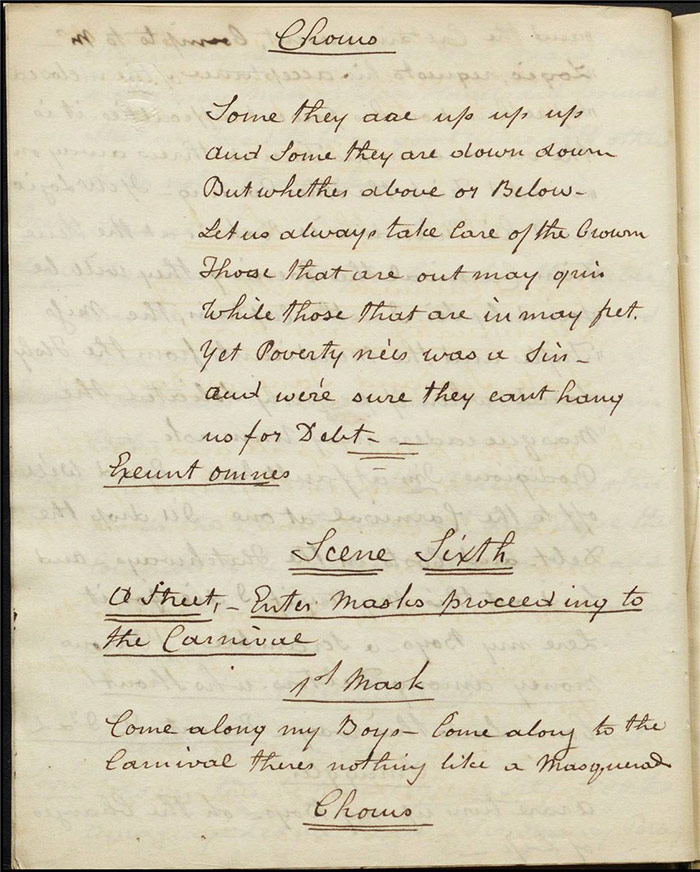

Scene 6

People in masks singing about the masquerade.

Scene 7

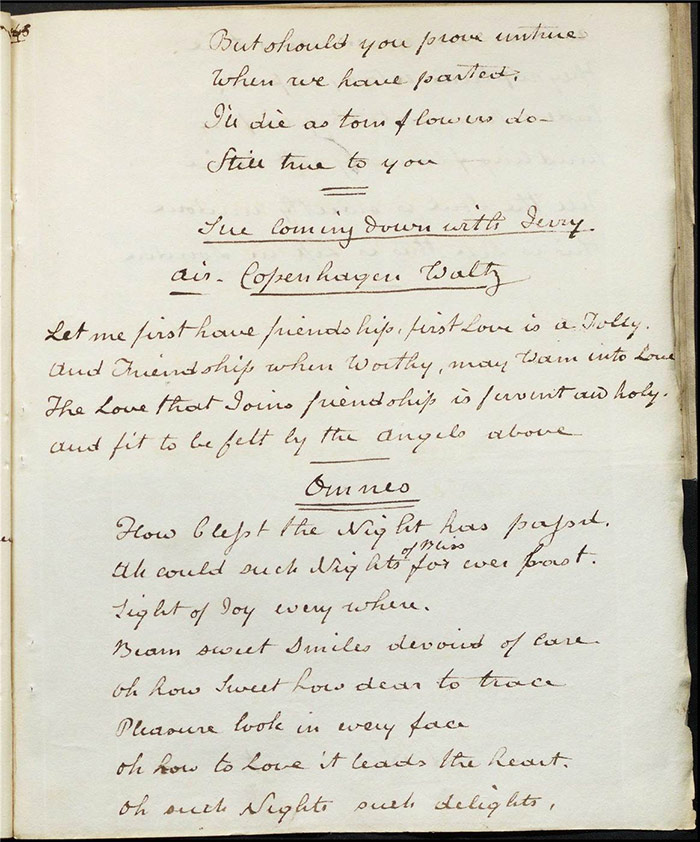

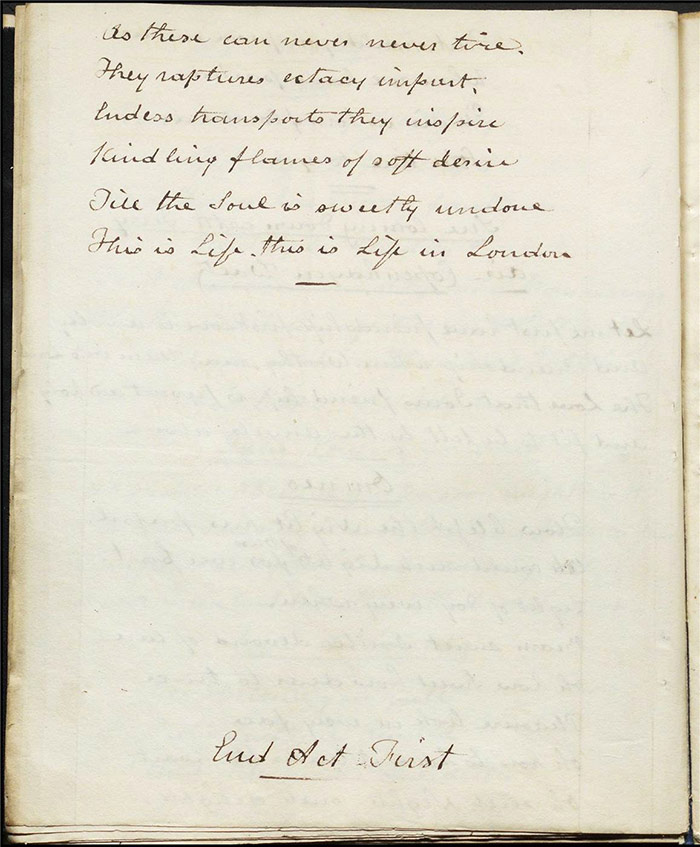

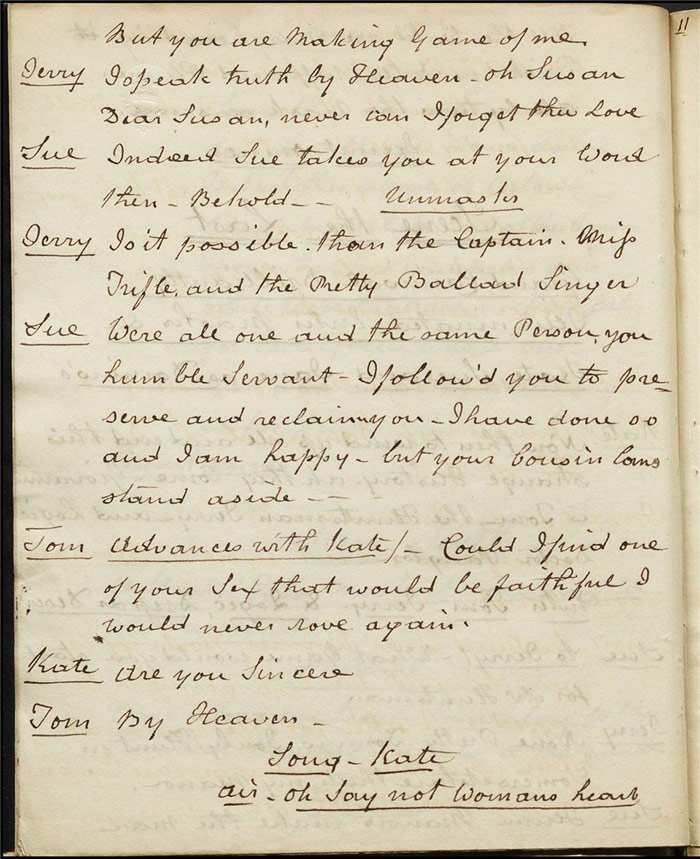

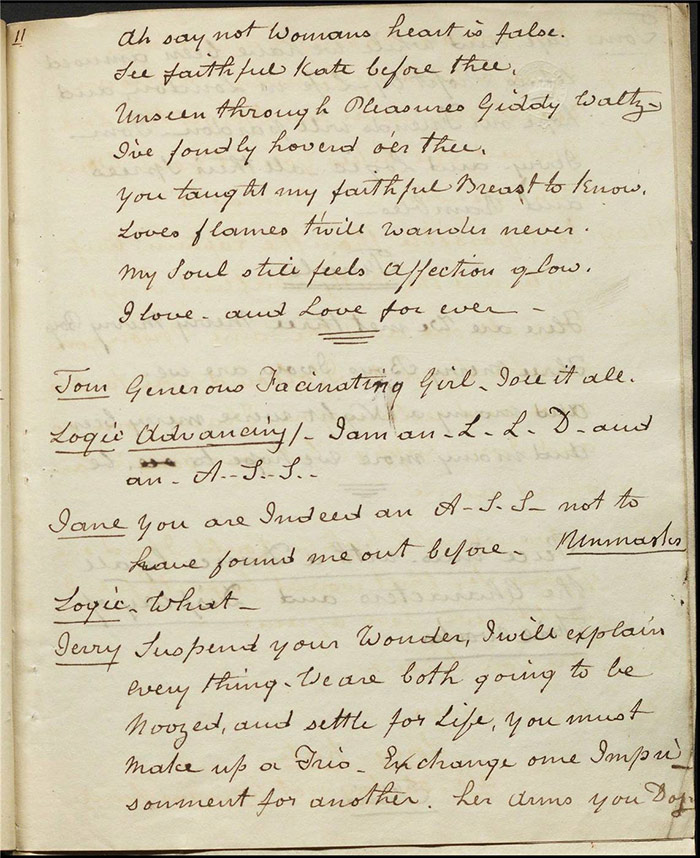

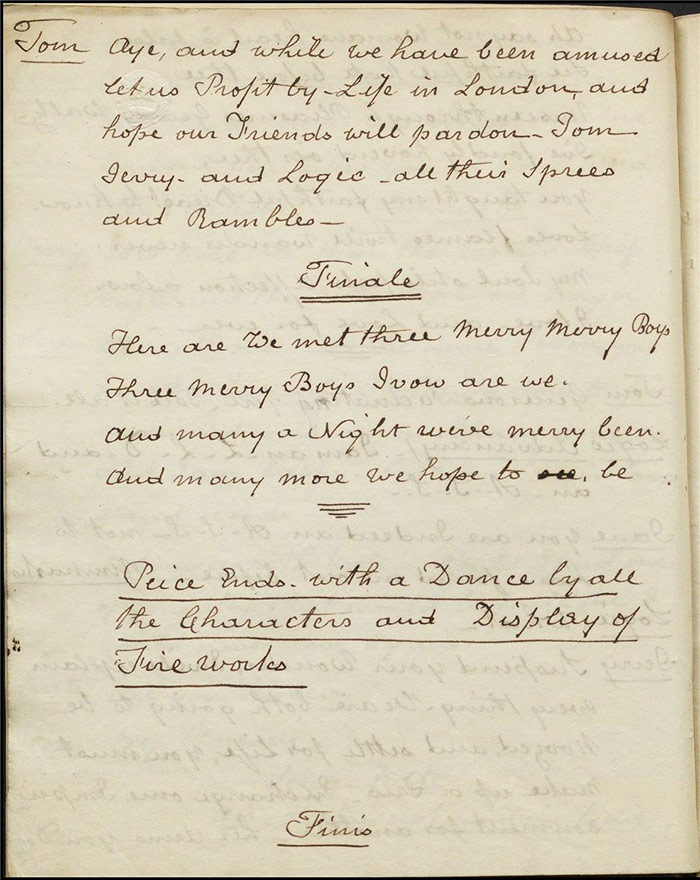

Kate and Sue reveal themselves to Tom and Jerry. They declare their mutual love. Jane and Bob are also paired off. Tom and Jerry seek the pardon of their friends—the audience—for their ‘sprees and rambles’.

Performance, publication, and reception

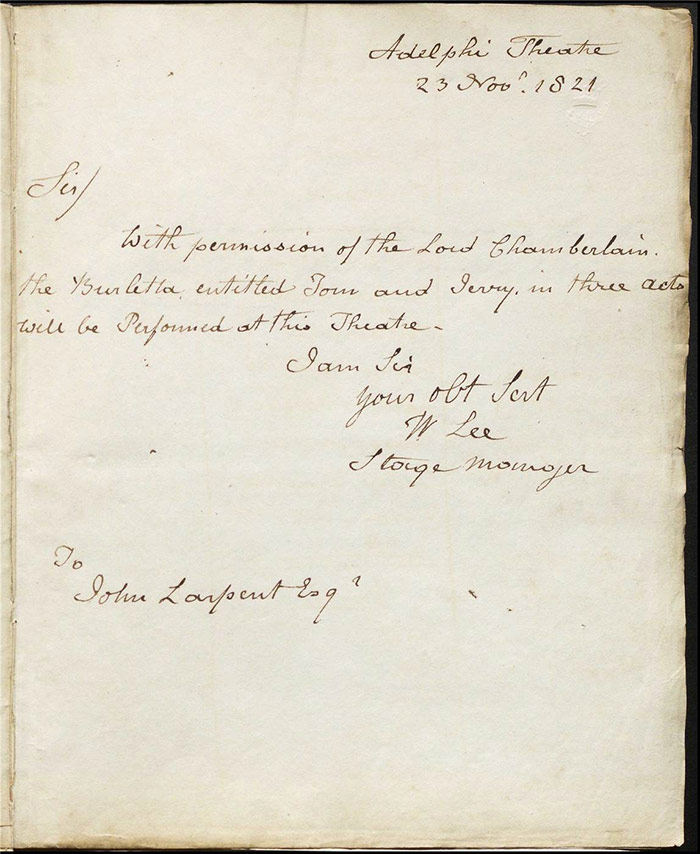

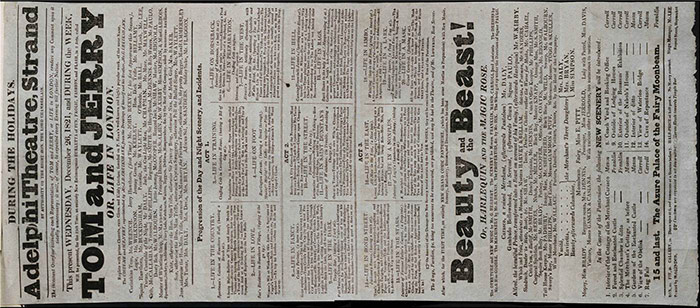

The manuscript was submitted to Larpent on 23 November by William Lee, the Adelphi stage manager. There is no mention of it in Anna Larpent’s diary. The piece was first staged on 26 November 1821 at the Adelphi Theatre advertised as a ‘Burletta of Fun, Frolic, Fashion, and Flash’ (Morning Chronicle, 26 November 1821).

The burletta was one of a number of dramatizations of Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1821). This publishing sensation, embellished by drawings by the Cruikshank brothers, took London by storm. Indeed, Moncrieff’s was not the only dramatization: the Olympia had staged its version earlier in the month and various other minor spinoffs can be detected. However, it is Moncrieff’s that was to prove most successful although one could not tell from the newspaper coverage which is sparse, to say the least.

The Morning Chronicle gave a brief but warm appreciation of Moncrieff’s efforts, describing it as a production of ‘great magnitude and splendour which does credit to the managers’. The scenery was deemed to be ‘new and excellent’ and the applause of the audience was marked by ‘unanimous appreciation’ (27 November 1821).

The Times was slow to publish its review of the burletta but it was also warmly enthusiastic. Describing it as a ‘very amusing piece’, it sums up Moncrieff’s work as:

A scenic representation of the Rake’s Progress through town, and is illustrative of the characters and customs of the different classes of society, among which the irregular habits of his life are certain to throw him at some stage or other of it.

The reviewer seems delighted by the ‘flash’ language i.e. London slang which, he writes, are ‘like the Eleusinian mysteries, are only intelligible to the initiated’. In a telling comment, he concludes by noting that the actors seem to be enjoying the fun as much as the audience (12 December 1821).

Not everyone was keen, however. The conservative weekly John Bull published some letters which were scathing on the morality of the Adelphi production. The issue for 9 December 1821 felt a ‘duty’ to warn people of the goings on at the theatre, evoking old radical demons from the 1790s:

We do not know what feelings the generality of fathers of families may have on such subjects, but for ourselves, we would no more suffer a copy of the book whence these dramas are compiled to be seen in our house, than we would a copy of “LITTLE’S Poems,” or “PAINE”S Age of Reason.”

The journalist continues in like vein, first describing Egan’s book as ‘a detailed and elaborate description of all the receptables of vice, sin, and debauchery’ and then inviting the reader to imagine ‘what this production put into action, aided by the advantages of theatrical embellishment, and animated by living performers, must be’. He lists many of the settings of the drama’s action before he demands an intervention:

[…] when one recollects that innocent girls and children are taken to these places, and are subject first to the indelicacies of the affiche [i.e. the use of the word ‘hell’ in the playbill], and next to the witnessing of scenes which the most depraved man in bettermost society would shudder at beholding, we really do think the legislature ought to interfere, and in time check an immorality which, at this particular season of the year, when the metropolis is filled with youth of both sexes, is most disgusting in its actual existence, and most dangerous in its probable consequences.

A letter from ‘A Constant Reader’ in the next issue (17 December) was very pleased with the article’s critique, agreeing that ‘a more immoral and disgusting representation was never exhibited before a British audience’. He exhorts John Bull to ‘caution the heads of families from as least permitting the females under their control from witnessing those scenes of debauchery and immorality’. The paper insists in an article that appears under the missive that it has received ‘several letters’ on the ‘filthy performance’. It calls again for the Lord Chamberlain’s intervention before slamming The Times for its indulgent review and concluding with this reflection;

What should we think of a man who took his daughter [on] a midnight walk through the blind allies of St Giles’s–taught her to listen with pleasure to the slang language of their inhabitants–and finished his paternal perambulation by taking her to a dance, or even a public masquerade at an alehouse? What father would hire a party of housebreakers and street-walkers to come to his residence, and display before his family all the cant and tricks of their trade? We should think such a parent not easily to be found on the bills of morality; and yet here, night after night, actors, whose talents (degraded and prostituted as they are) are well qualified to give effect to the performance, are suffered to exhibit con amore every species of depravity with which this immense metropolis is infested.

Despite this strong objection, the play was an enormous success. According to an edition of Egan’s Life in London published in 1869 by John Camden Hotten, a writer with interest in both slang and erotica, Moncrieff’s version ran for more than three hundred nights. Moncrieff himself recollected its remarkable popularity which was reprinted in Hotten’s edition:

[…] this piece obtained a popularity and excited a sensation totally unprecedented in theatrical history: from the highest to the lowest, all classes were alike anxious to witness its representation. Dukes and dustmen were equally interested in its performance, and peers might be seen mobbing it with apprentices to obtain an admission. Seats were sold for weeks before they could be occupied; every theatre in the United Kingdom, and even in the United States, enriched its coffers by performing it; and the smallest tithe-portion of its profits would for ever have rendered it unnecessary for its author to have troubled the public with any further productions of his Muse. It established the fortunes of most of the actors engaged in its representation, and gave birth to several newspapers. The success of the Beggars’ Opera, the Castle Spectre, and Pizarro, sunk into the shade before it. In the furor persons have been known to travel post from the farthest parts of the kingdom to see it; and five guineas have been offered in an evening for a single seat. Its language became the language of the day; drawing rooms were turned into chaffing cribs, and tank and beauty learned to patter slang (Hotten, 13-14).

Commentary

The manuscript is a relatively clean copy with minimal intervention. There are a small number of emendations marked in pen. We may speculate with a degree of confidence that these were made by Larpent; he would have been unlikely to allow the use of the ‘damme’ (see here and here) nor the representation of a drunk clergyman, the two items that motivate the excisions (see here and here).

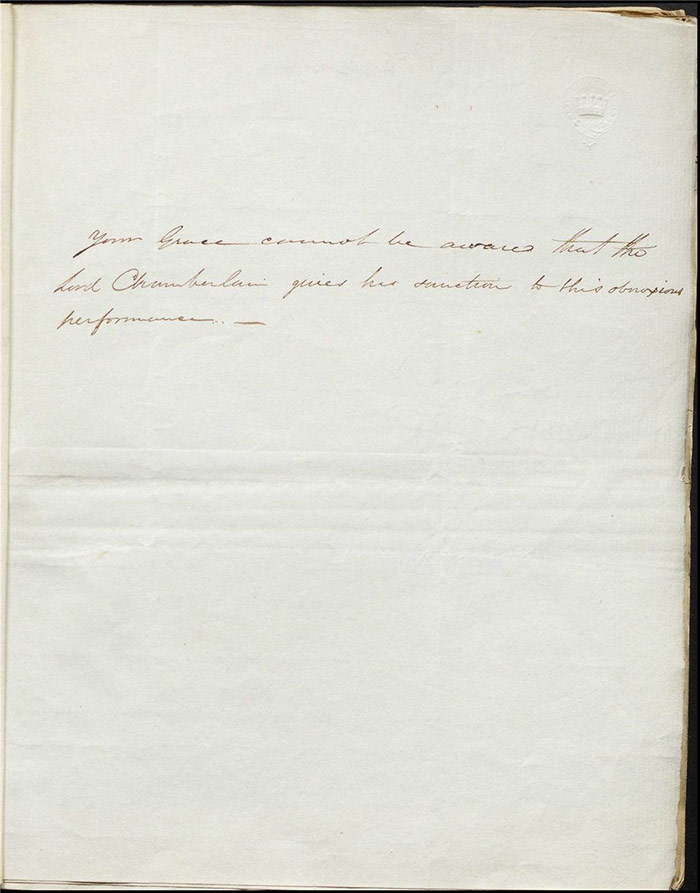

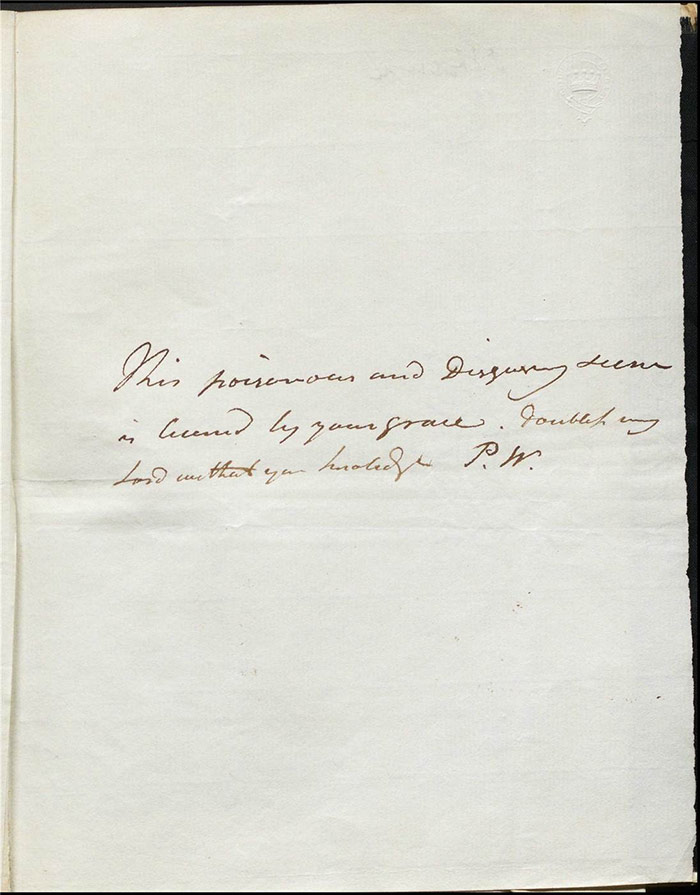

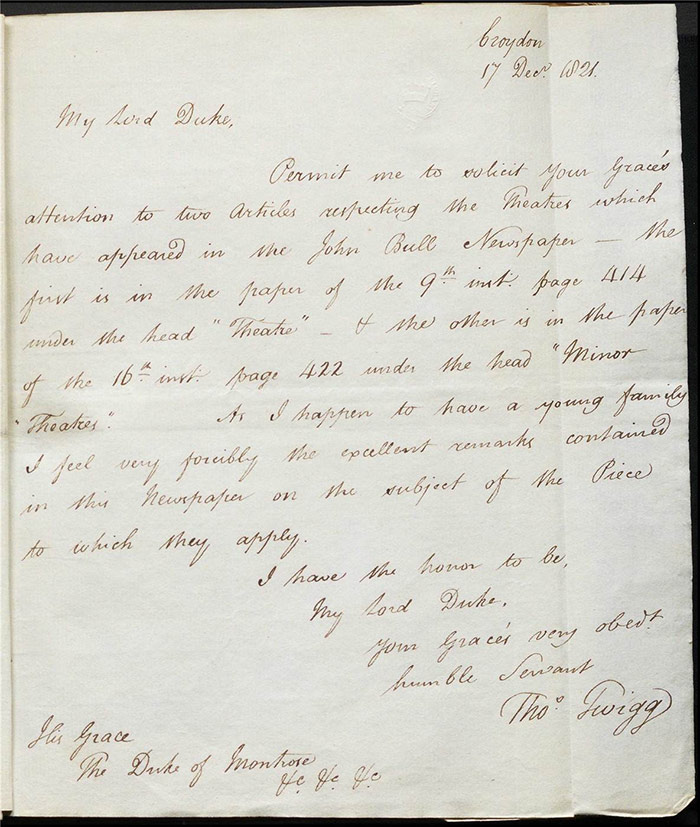

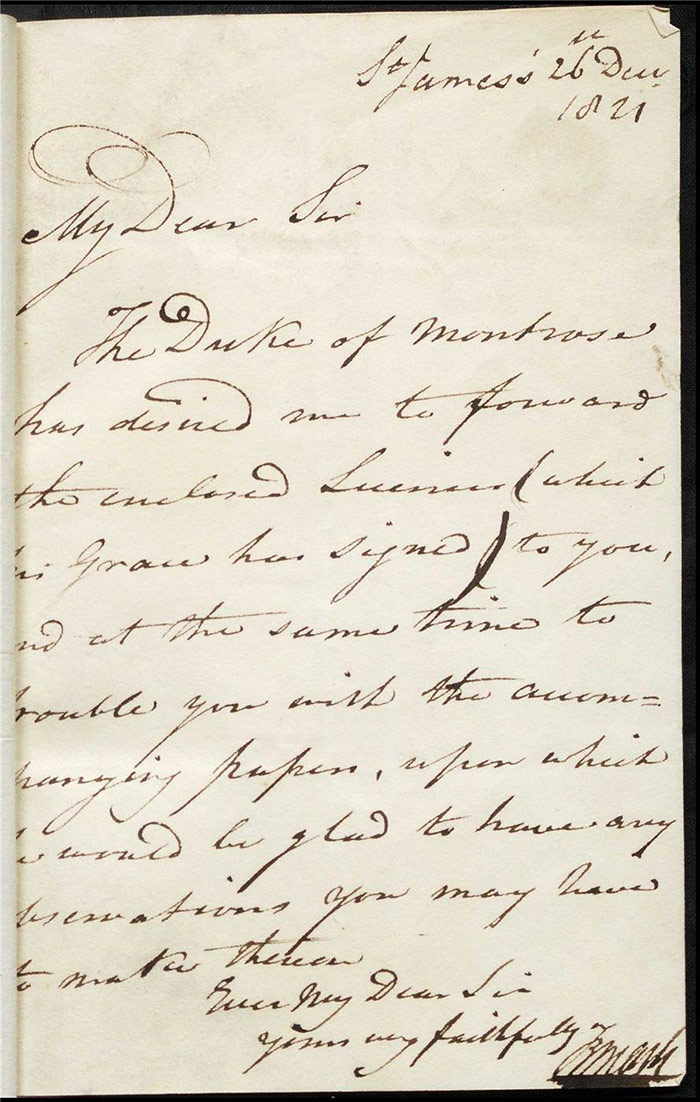

The interest of the piece in terms of censorship is the enormous popularity of the play and the strident opposition to the piece. As the John Bull states, there were certainly some who felt that the Examiner and the Lord Chamberlain had failed in their duty to public morality. The Larpent manuscript also includes further evidence of this with some comments on papers written in different hands. One individual wrote ‘Your grace cannot be aware that the Lord Chamberlain gives his sanction to this obnoxious performance’, perhaps a note written to another duke whom the author hoped would put pressure on the Duke of Montrose, Lord Chamberlain. Another individual wrote to the Lord Chamberlain himself and said ‘This poisonous and disgusting scene is licenced by your grace doubtless my Lord without your knowledge. P.W.’ Finally, Thomas Twigg wrote to Montrose on 17 December 1821, applauding the John Bull articles and adding ‘As I happen to have a young family I feel very forcibly the excellent remarks contained in this Newspaper on the subject of the Piece to which they apply’. Montrose certainly took notice of all this; his office sent a letter to Larpent on 26 Dec 1821:

The Duke of Montrose has desired me to forward the enclosed Licences (which his Grace has signed) to you, and at the same time to trouble you with the accompanying papers, upon which he would be glad to have any observations you may have to make therein.

Sadly, we do not have Larpent’s response but we do know that Montrose attended at least two performances. Moncrieff appears to have been delighted with the controversy and he had nothing to fear from Montrose despite a coordinated campaign by the Methodist community:

With respect to the cry of immorality, so loudly raised by those inimical to the success and plain speaking of this piece, it is soon answered, To say nothing of the envy of rival theatres feeling its attraction most sensibly in their Saturday treasuries, those notorious pests, the watchmen, dexterously joined in the war-howl of detraction raised against it, and by converting every trifling street broil into a ‘Tom and Jerry row,’ endeavoured to revenge themselves for the exposé its scenes afforded of their villainy and extortion—but all in vain. In vain, too, it was that the actors’ old rivals, the Methodists, took the alarm,—in vain they distributed the whole stock of the Religious Tract Society at the doors of the theatre, —in vain they denounced Tom and Jerry from the pulpit,—in vain the puritanical portion of the press prated of its immorality: they but increased the number of its followers, and added to its popularity. Vainly, too, was the Lord Chamberlain called upon to suppress it. His Grace came one night to see it, and brought his Duchess the next. (Hotten, 14)

Moncrieff argued in fact that the drama had ‘as correct tendency as any production brought on the stage’. He claimed to show the ‘obnoxious scenes of life’ in order that they be avoided and that happiness is demonstrated to be located in the ‘domestic circle’. To those who accused him of instigating the age of flash, he said ‘Any age is better than The age of cant’ (Hotten, 15).

On 2 July 1832 Moncrieff gave testimony to the Select Committee. On Tom and Jerry, he insisted that it was ‘anything but a legitimate drama’. In other words that it was only suitable for a minor theatre. When pressed, Moncrieff stated that although Tom and Jerry exhibited the manners of the time (one of the functions he had said was appropriate to the legitimate drama), ‘it was mixed up with all sorts of trash to draw an audience’ (Select Committee Report, 176).

Further reading

Report from the Select Committee on Dramatic Literature with the Minutes of Evidence (London: House of Commons, 1832)

[available on archive.org]

John Russell Stephens, ‘Moncrieff, William Gibbs Thomas [formerly William Thomas Thomas] (1794–1857)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18951, accessed 13 February 2019]

John Camden Hotten (ed), Tom & Jerry Life in London or the Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorn, Esq. and his Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom in their Rambles and Sprees through the Metropolis (London: John Camden Hotten, 1869).

[available on archive.org]

David Worrall, The Politics of Romantic Theatricality, 1787–1832: The Road to the Stage (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), chapter 6 and 7.