Marino Faliero (1821) LA 2224

Author

Lord Byron, George Gordon (1788-1824)

Byron was educated at Harrow (where he met Thomas Moore, his later biographer) and Cambridge. His first publication Poems on Later Occasions appeared in 1807. Shortly after moving to London, he suffered a scathing review in the Edinburgh Review which prompted his first significant work English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809). The same year saw him depart on the Grand Tour for two years, including a considerable period in Greece. On his return, he was beset by considerable financial difficulties. In 1812 he published the first two cantos of Childe Harold which made him a literary star.

He got married in 1815 but his wife and child left him a year later. An adversarial and very public separation took place and Byron left England. He met the Shelleys and Claire Clairmont at Lake Geneva and spent time in Venice. John Murray began to pay Byron generously for his poetry so that his finances improved in the wake of subsequent cantos of Childe Harold and his masterpiece Don Juan which began to appear in 1819.

Most of his other major dramatic works also appeared in 1821. He had long had an interest in the theatre and had written an address on the reopening of Drury Lane in 1812 (LA 1737). He became a member of the committee for Drury Lane Theatre in 1815 and was friendly with Edmund Kean, among other actors and actresses. He published Sardanapulus (an historical tragedy detailing the fall of the last supposed king of the Assyrian empire), The Two Foscari (a historical tragedy based on the fall of Francesco Foscari, another Venetian Doge), and Cain (a verse account of the biblical story) in 1821. The Deformed Transformed and Werner followed in 1824.

Byron had broken with John Murray in 1822; the publisher had been increasingly troubled by the scandalous nature of Byron’s writings. He was elected to the London Greek Committee and travelled to Greece in 1823 to fight for its independence. He fell ill there in 1824 and died. Such was his infamy, he was refused burial in Westminster Abbey.

Plot

[The Larpent text is not foliated so references are to page numbers]

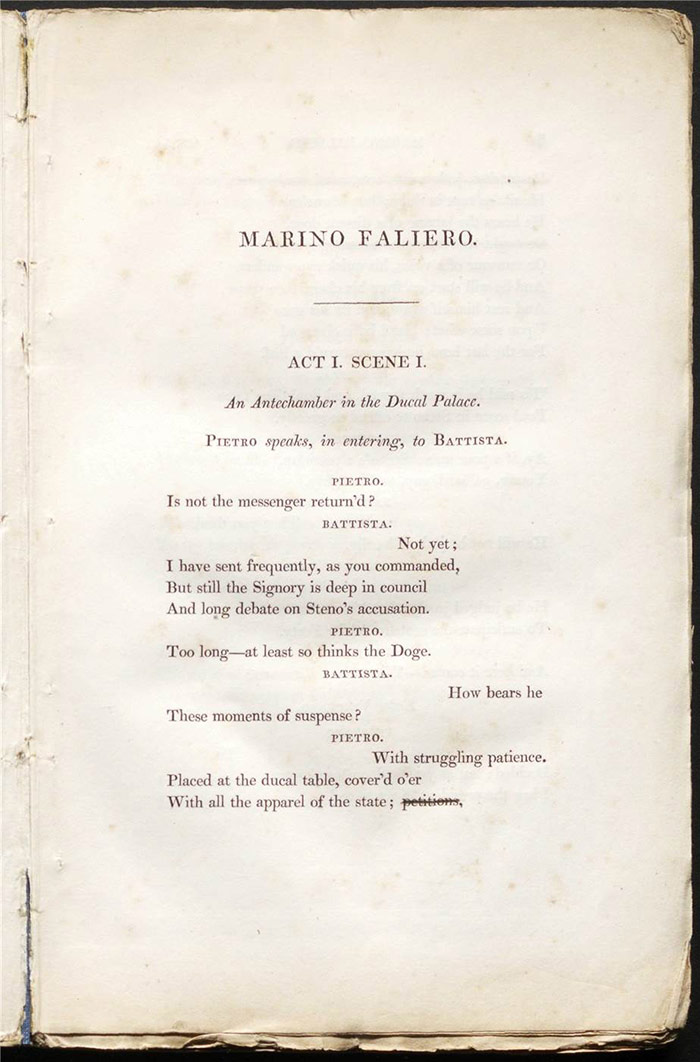

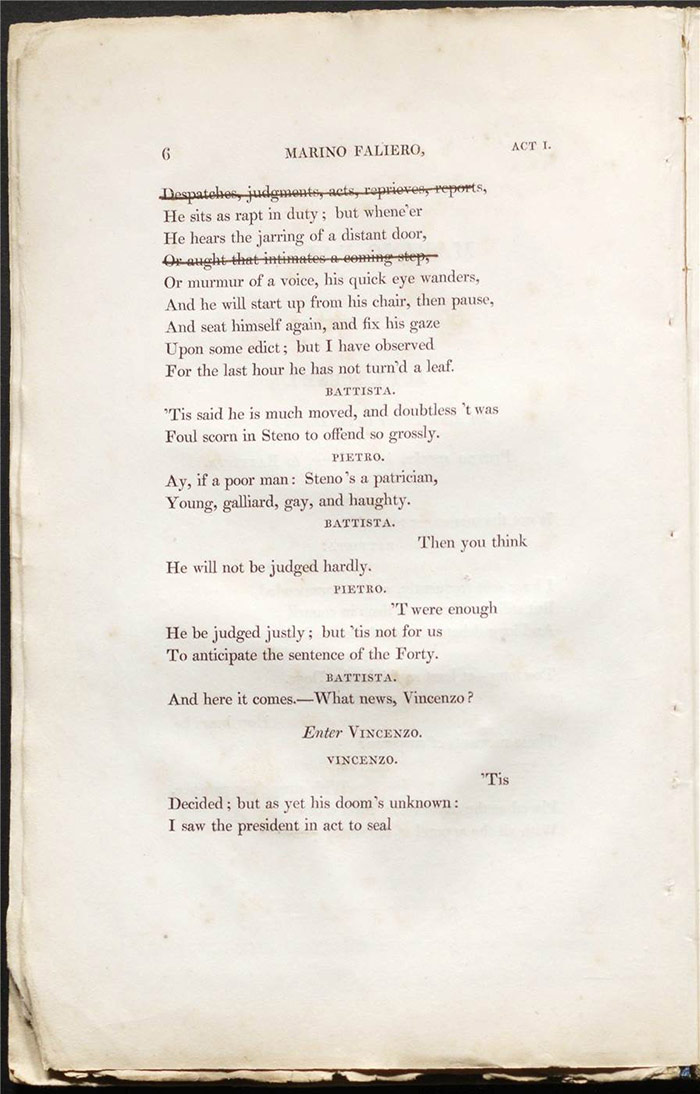

Pietro and Battista, officers of the ducal palace, discuss the Doge of Venice’s anxiety regarding a pending judgment of the Forty. This judicial body will pronounce a sentence on Steno–who is a member of the Forty–for an as yet unknown crime.

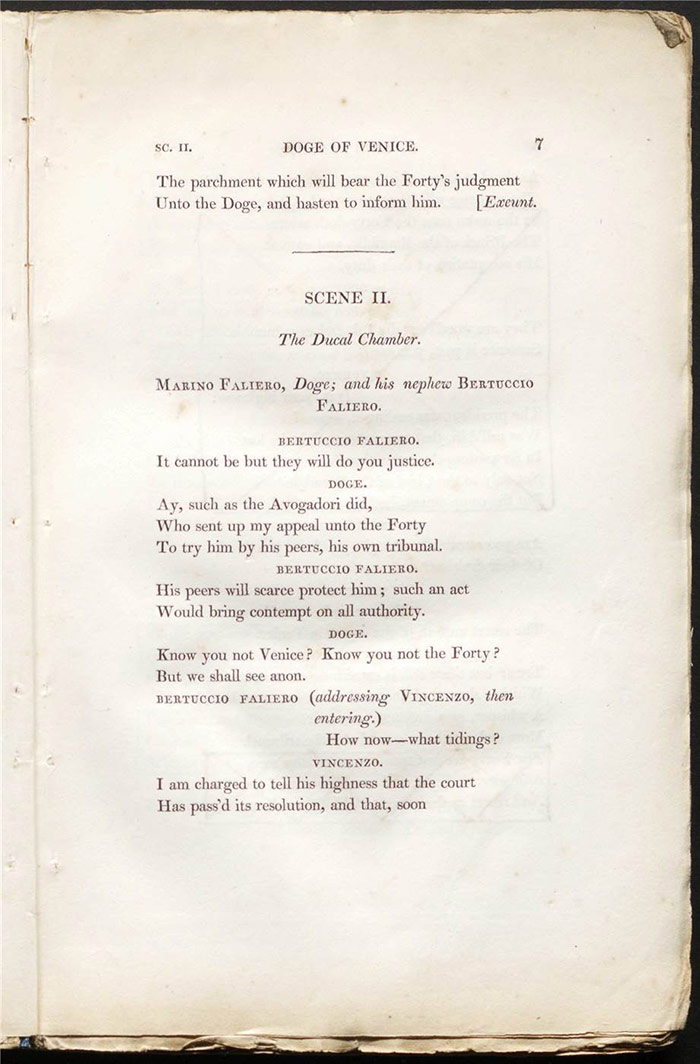

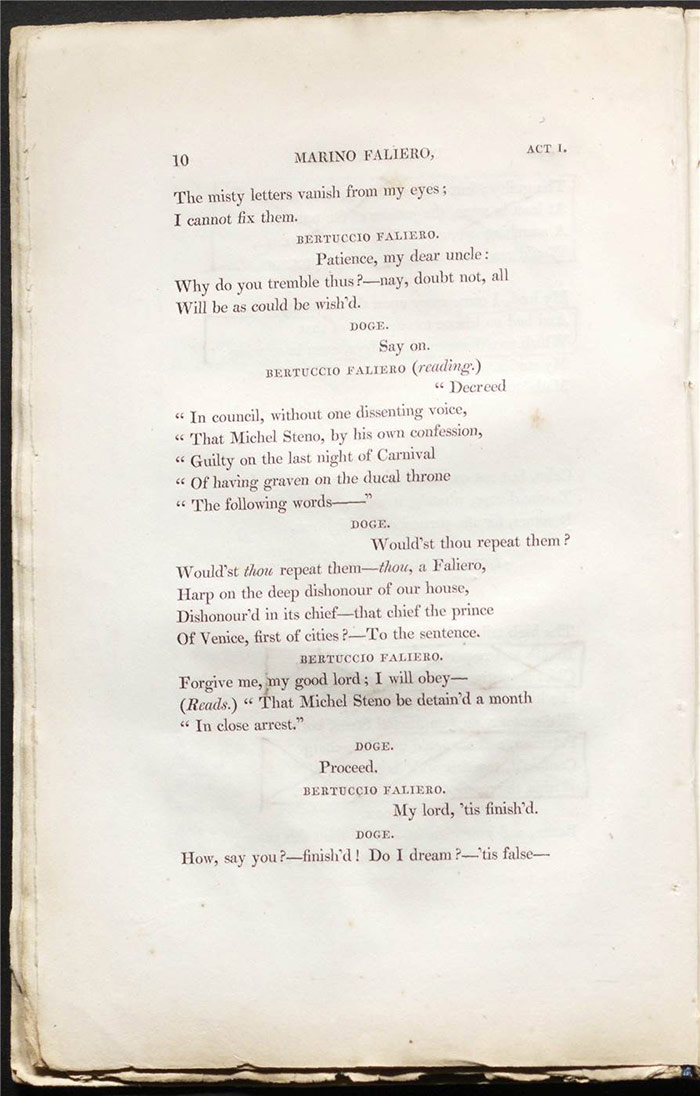

Marino Faliero, the Doge of Venice, awaits the sentencing of Steno with his nephew Bertuccio Faliero (p.7). Steno had written a public and defamatory note about Faliero’s wife, implying sexual misconduct. The Forty condemn Steno to a month’s imprisonment and Faliero is enraged by their leniency. Israel Bertuccio, who has also been wronged by a member of the Forty, Barbaro, calls on him to ask for justice. He reveals plans of a rebellion and Faliero promises to meet with them that night.

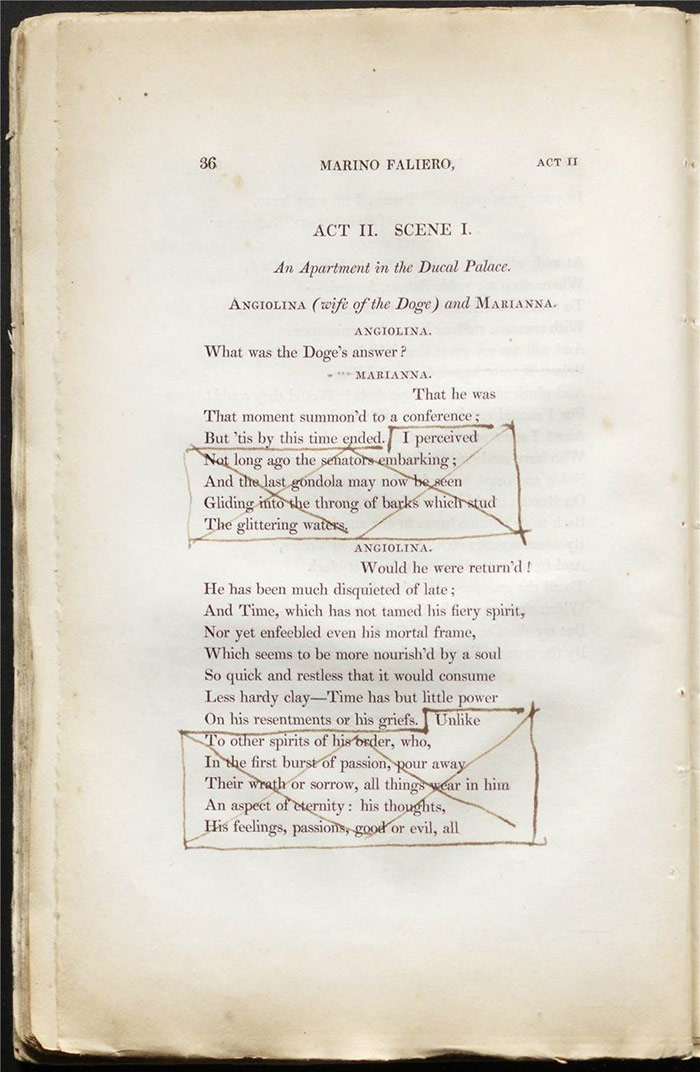

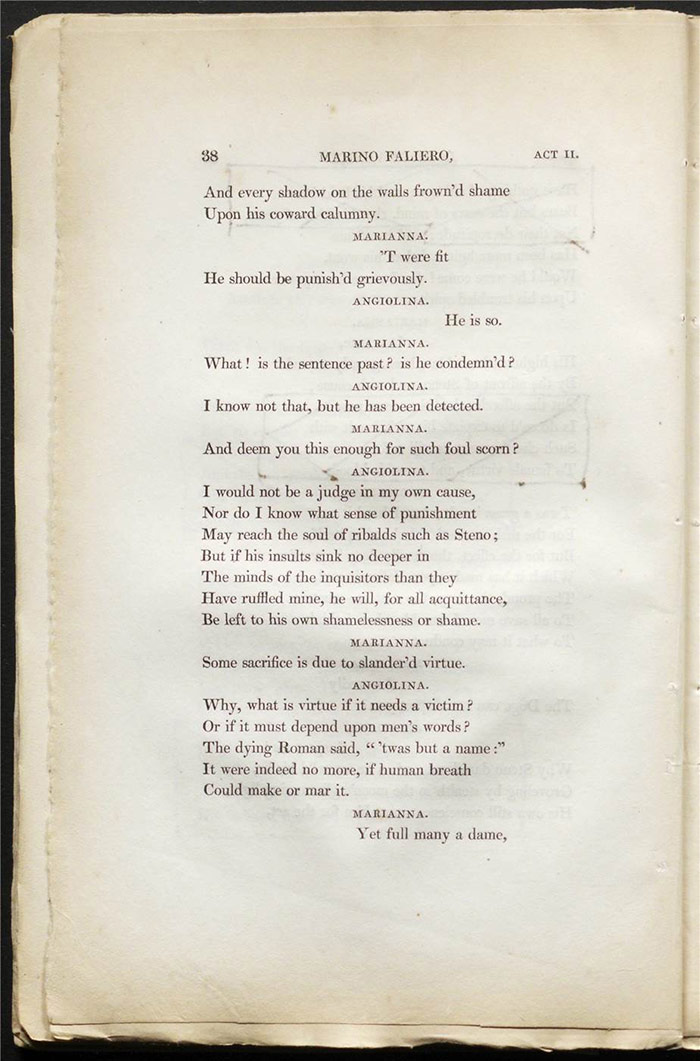

At the opening of the second act, Angiolina, the wife of the Doge, discusses events and her marriage with her friend Marianna (p.36). When the Doge enters, Marianna leaves. Angiolina tries to convince the Doge that Steno’s sentence is adequate but is unable to shake his sense of betrayal and outrage at what he sees as the dissolute nature of Venice’s institutions. Before he leaves he gives her some written instructions to read later. Philip Calendaro asks Israel Bertuccio how his quest for justice went (p.58). Israel professes contentment but holds back full explanation until a planned meeting of their conspiracy later that night. Calendaro expresses some doubts about one of their fellow plotter, Bertram, which Israel dismisses. He also tells Calendaro he is bringing someone along who he sees as a new leader, much to Calendaro’s shock and skepticism.

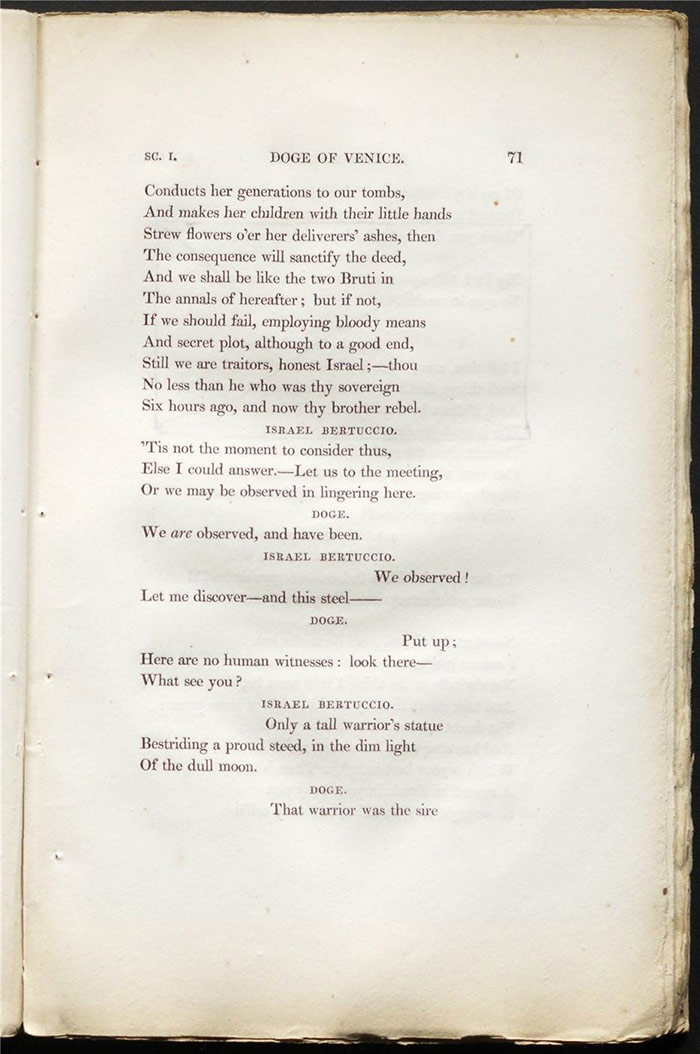

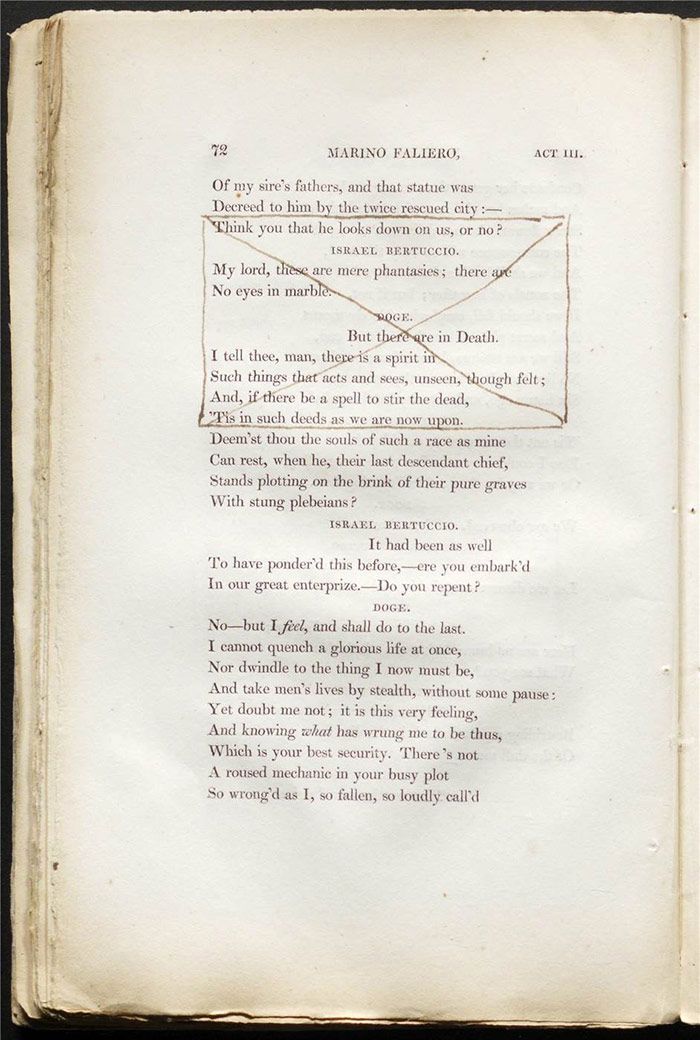

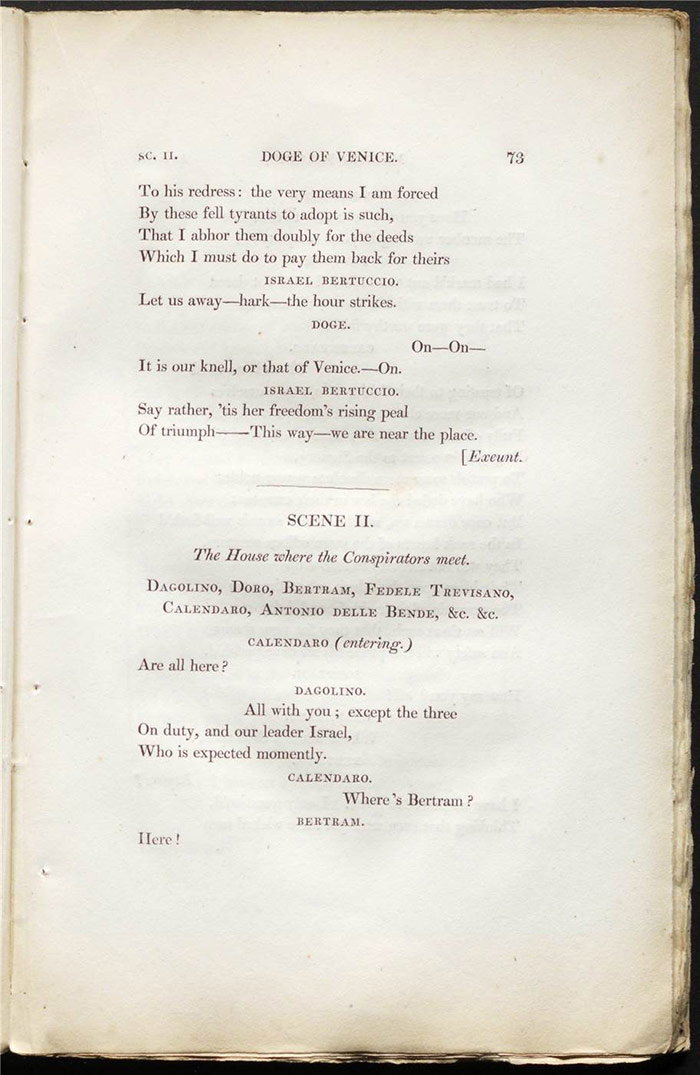

In act 3, Israel Bertuccio and the Doge meet at night and discuss the nature of their treasonous actions (p.68). Calendaro and Bertram are at the house where the conspirators are meeting (p.73). Calendaro wants to kill all of the Forty; Bertram is startled by this. Calendaro does not like Bertram’s lack of conviction. Israel Bertuccio and the Doge enter to the consternation of the group who believe that Bertuccio has betrayed them. The Doge delivers a lengthy speech detailing the degeneracy of the state and its people and the need for rebellion which wins them over. He tells them they must accelerate their plans and strike at dawn. Bertram is disturbed by the bloodthirsty rhetoric but the Doge calls for the extermination of all the patricians. They disperse to their posts of the rebellion to come except for the Doge and Bertuccio. The Doge vacillates as he remembers his friends among the Forty but then regains his resolve.

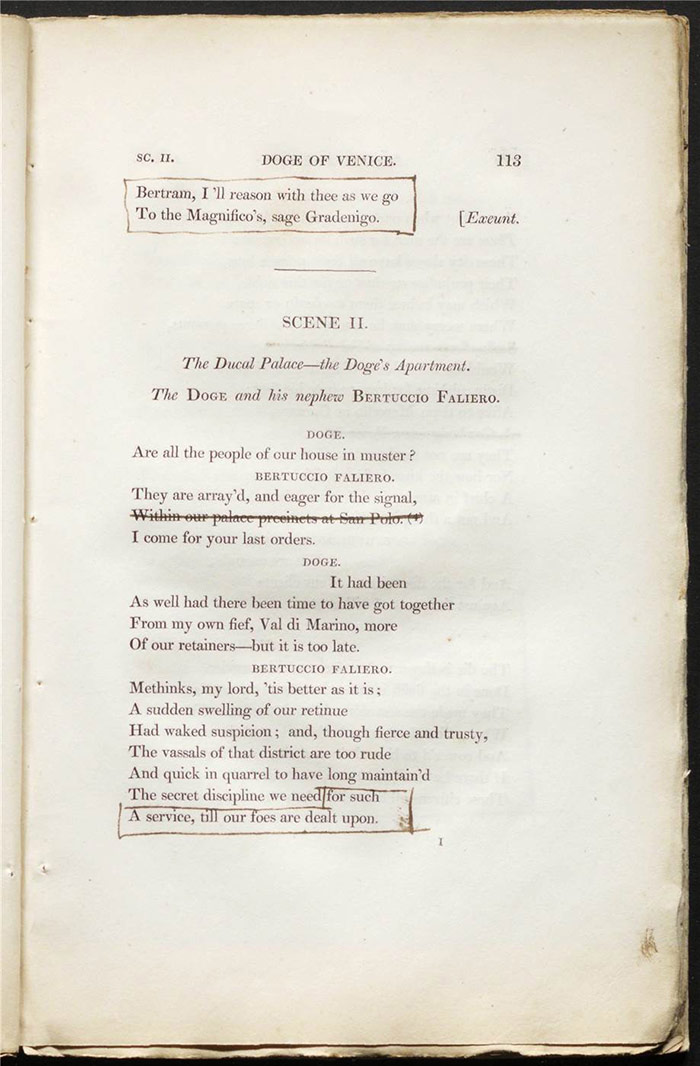

The patrician Lioni has returned home from a masquerade ball in act 4, full of anxiety and foreboding (p.97). Bertram calls to warn him about the planned rebellion, asking him not to go forth tomorrow but refusing to explain why. Lioni refuses to accept the cloaked warning and tries to force Bertram to reveal the plot. Lioni has him arrested and plans to bring him before the Doge. The Doge and his nephew Bertuccio Faliero reflect on the necessity of the action to purge the state (p.113). His nephew leaves to take part and then guards enter and arrest the Doge for high treason. His nephew is also taken. They are separated until their trial.

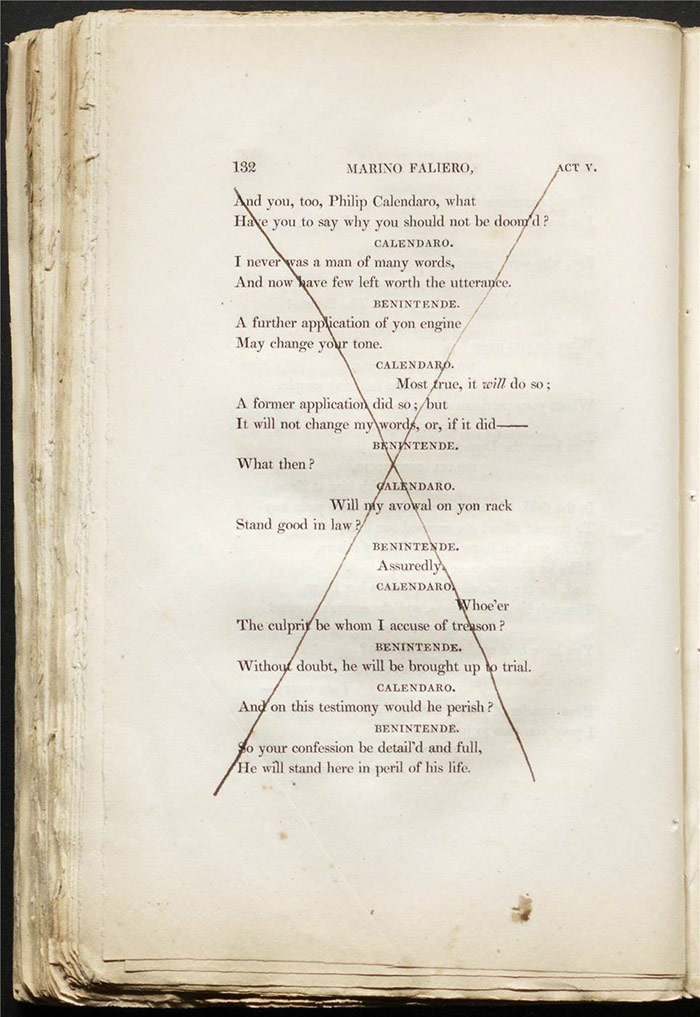

The final act finds the Council of Ten assembled to judge the traitors on behalf of the Forty (p.128). Benintende, the chief judge, asks Israel Bertuccio first about his motives and then Philip Calendaro. They are defiant and sentenced to death. Bertram asks their forgiveness which Bertuccio gives but Calendaro denies. They are led off and the Doge is then brought in for his trial. He refuses to recognize the court’s authority and returns some defiant rhetoric. But despite his wife’s interjection, he is sentenced to death. The Doge and the Duchess converse until he is called for execution (p.155). She faints as he exits. The Doge delivers a defiant speech forecasting political change before the executioner raises his sword (p.160). Some citizens have managed to gain a view of the proceedings and observe the execution (p.165). The crowds rush in the gates as Marino Faliero’s head is displayed to them.

Performance, publication, and reception

Byron’s Marino Faliero is one of the best well known plays in this resource and there has been considerable critical analysis of it. This brief survey makes no claim to cover all the ground and limits itself to pointing out the more salient facts as to the play’s conception, publication and performance. The bibliography below should also be considered only a starting point for the reader interested in exploring the complexities of this drama; a more comprehensive bibliography of recent criticism can be found with John Gardener’s essay cited below.

The play was published by John Murray on 21 April and submitted the same day to Drury Lane Theatre. It was first performed on 25 April at Drury Lane Theatre. The newspapers record that it was performed for the seventh time on Monday 14 May (The Examiner, 13 May) with another performance scheduled for Friday 18 May, indicating that it was a modest success at least in terms of the number of performances.

Anna Larpent was one of its first readers. She wrote about reading the play on 21 April 1821:

Also [reading] MS tragedy Marino Faliero it is published an injudicious story for representation. the language [illeg] for recital, not without poetic ideas, but without poetic language sometimes prosaic – the whole is so cut up for representation that I think it will prove absurd, heavy, dull the attempt at interest forced & hardly to be raised – the hero is a species of dotard Doge in a passion without the feelings & [fl]ames of resentment in Lear’ (HM31201, vol. 11, f.190r)

The Times (26 April 1821)wrote a comprehensive and rather damning review. The play was not performed, it said, but rather ‘fragments, violently torn from that noble work, were presented to the audience’. It recounts that a handbill was distributed to the audience that claimed the performance was taking place ‘in defiance of the injunction of the Lord Chancellor’ which had been requested by its ‘noble author’. This seems to have caused some excitement in the audience and indeed some consternation backstage as there was a delay in starting the play. But the play was performed to the horror of the reviewer, dismayed at the trampling of the author’s rights:

And next, if the wholesale invasion of private property and private feeling be allowed, what must we think of those who employ their literary butchers to mangle and mutilate (as in this case they have mangled and mutilated) that which they have had the hardihood to make their prize? Procrustes-like, they have irreverently lopped and disfigured the body of the Doge of Venice, to fit him for the narrow bed of torture at Drury-Lane.

The reviewer admires the play as he has read it (‘the poetry is of the highest order’) but cannot condone this version in which ‘bungling efforts have been made to compress the scenes’. The review bemoans the absence of Edmund Kean who would have ‘given life, and spirit, and energy to the scene’ (Mr Cooper, who played the Doge, was not, it seems ‘a man of exalted genius’). However, there was praise for Mrs West (Angiolina) who played with ‘great pathos’.

The Caledonian Mercury (30 April 1821) was not impressed either although it was not quite as damning. It admitted to the quality of the language, its ‘lofty thoughts’ and ‘beautiful imagery’ but not its performative qualities. If it was an ordinary dramatist, it would have been condemned but:

The name, reputation, and fashion of the author, however, carried it through triumphantly, the attempts of the malcontents—feeble in the extreme—being soon overpowered and put down by the applause of the well affected.

On the surface, at least, Byron would have happily concurred with these assessments. He wrote to John Murray (16 February 1821):

You say “the Doge” will not be popular–did I ever write for popularity?––I defy you to show a work of mine (except a tale or two) of a popular style or complexion.–It appears to me that there is room for a different style of the drama–neither a servile following of the old drama–which is a grossly erronious one–nor yet too French–like those who succeeded the older writers.–It appear to me that good English–and a severer approach to the rules–might combine something not dishonourable to our literature.––I have also attempted to make a play without love.––And there are neither rings–nor mistakes–nor starts–nor outrageous ranting villains–nor melodrame–in it.–All this will prevent it’s popularity, but does not persuade me that it is therefore faulty.–Whatever faults it has will arise from deficiency in the conduct–rather than in the conception–which is simple and severe. (Marchand, 252)

Commentary

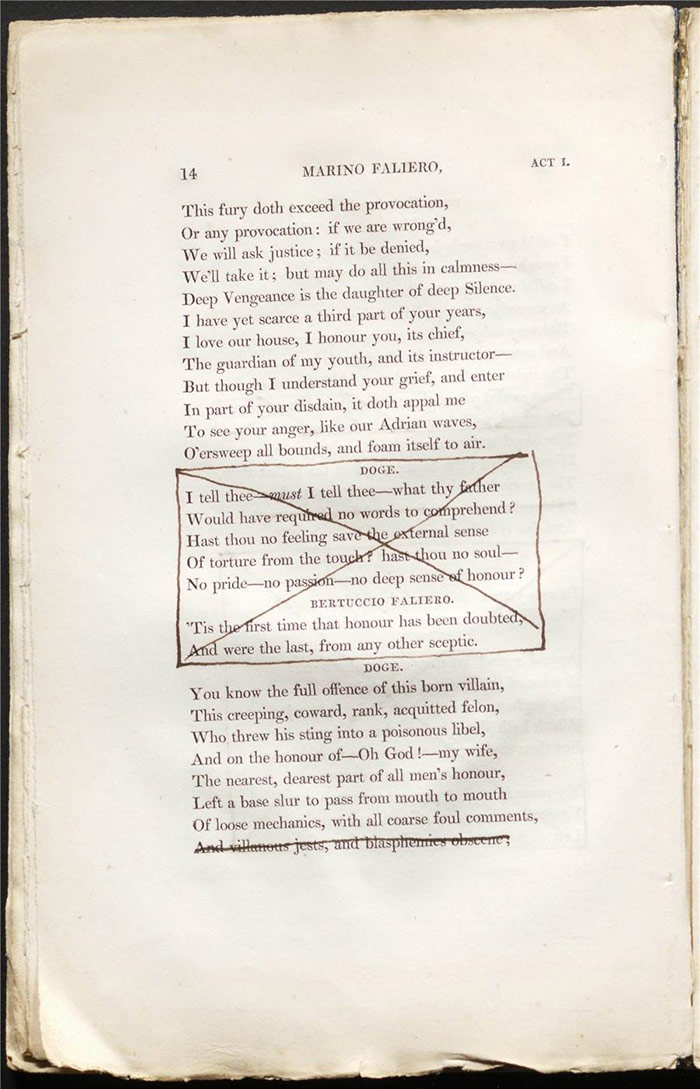

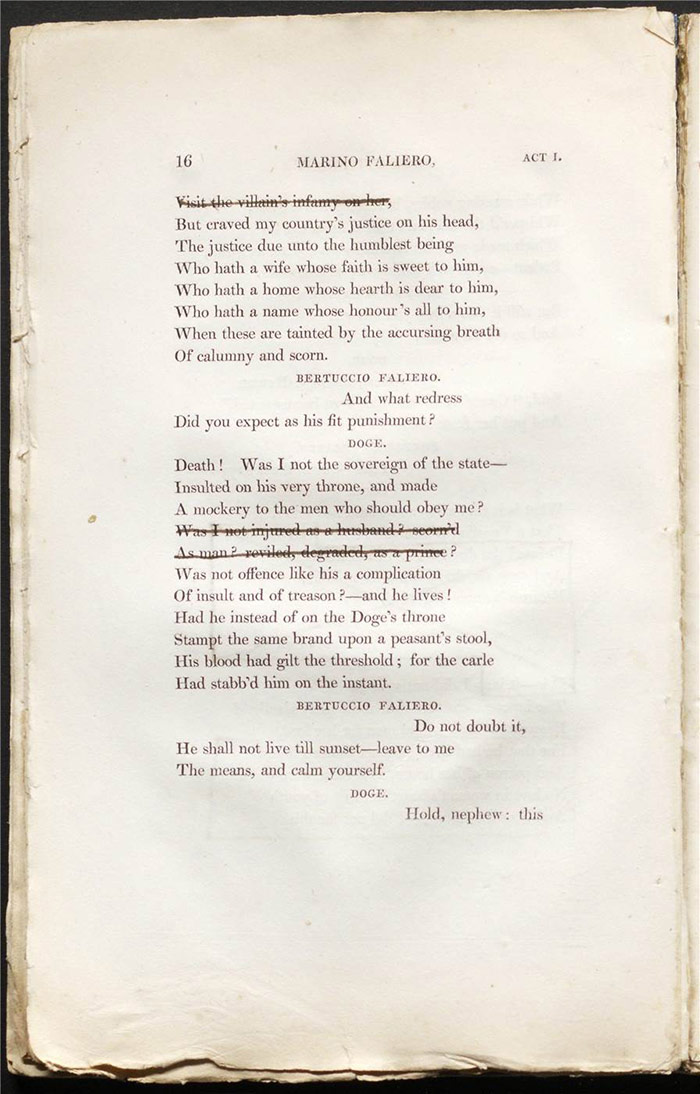

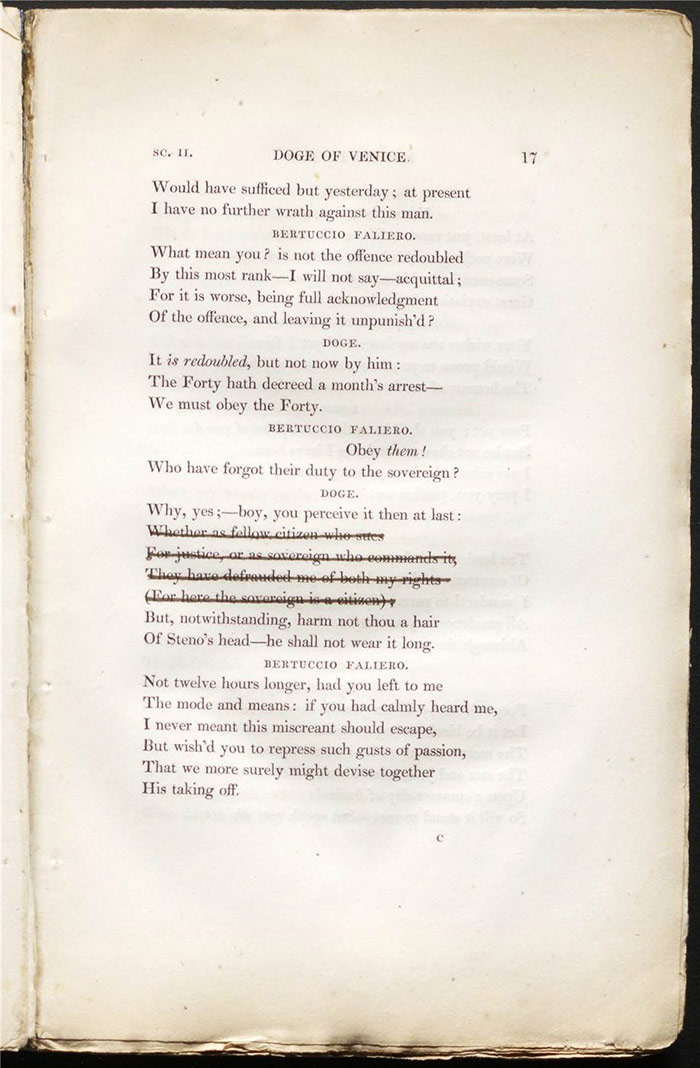

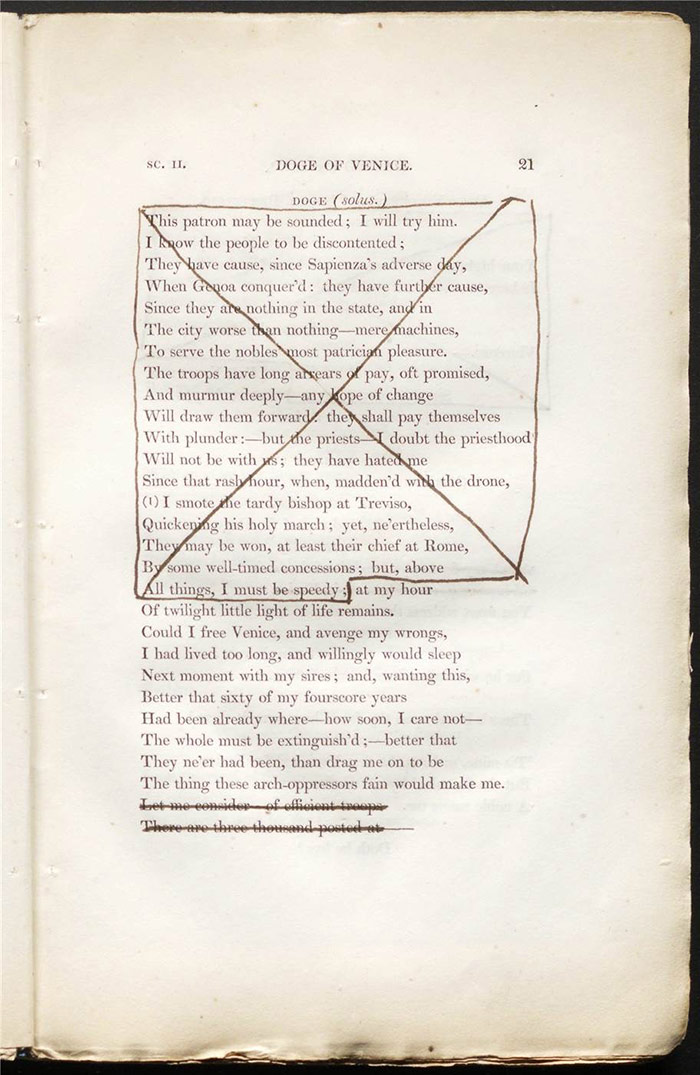

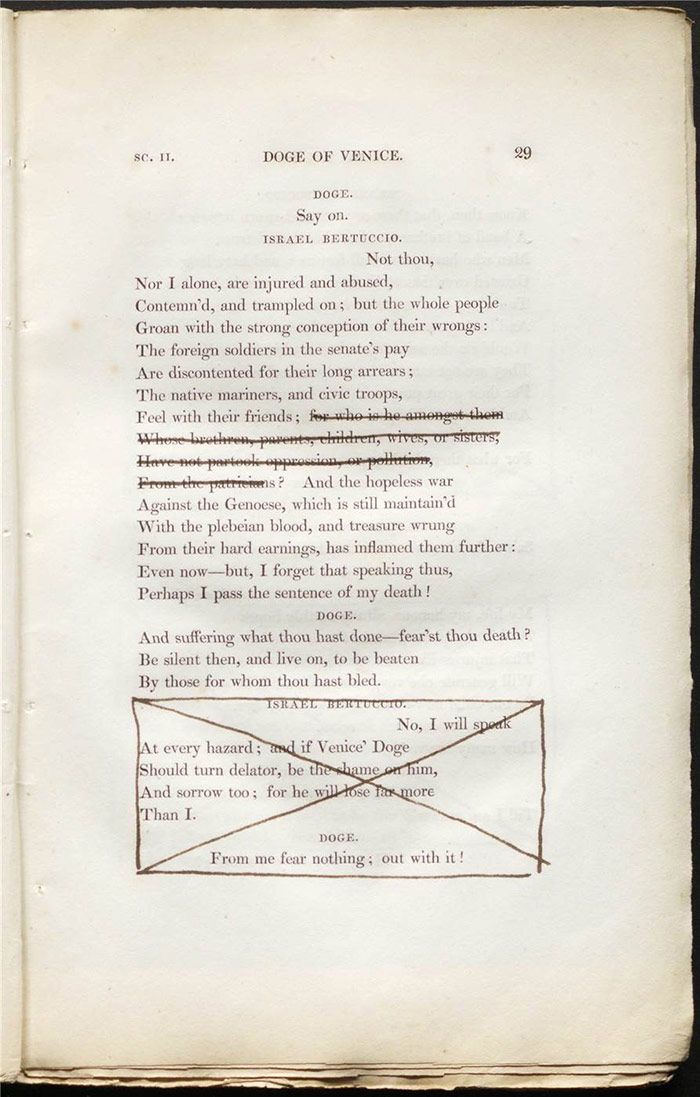

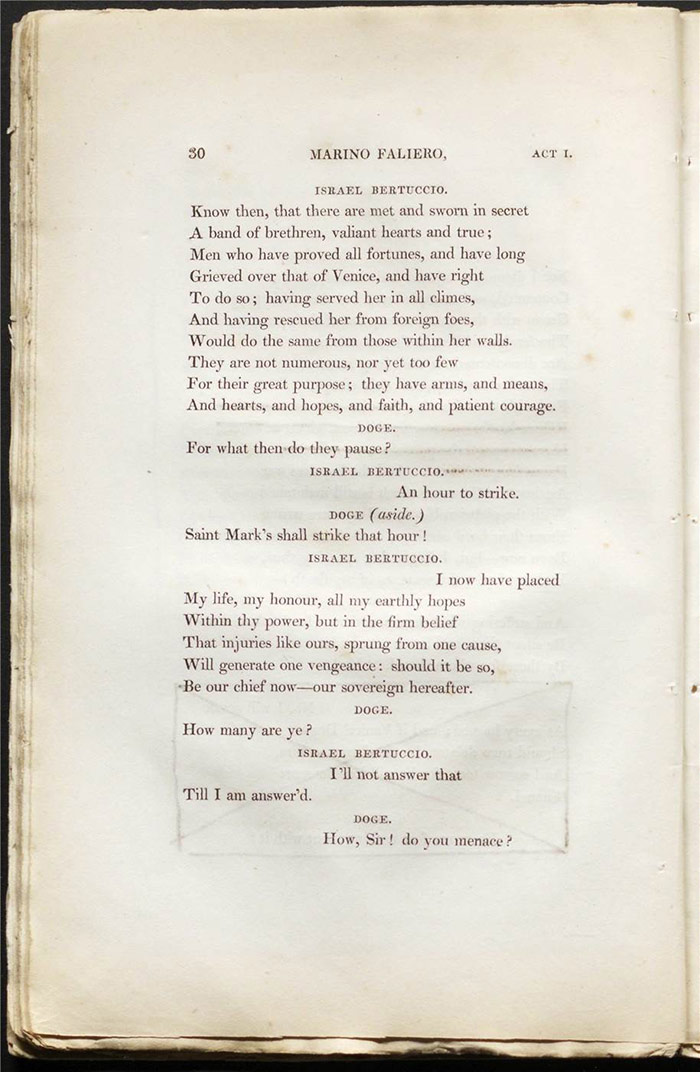

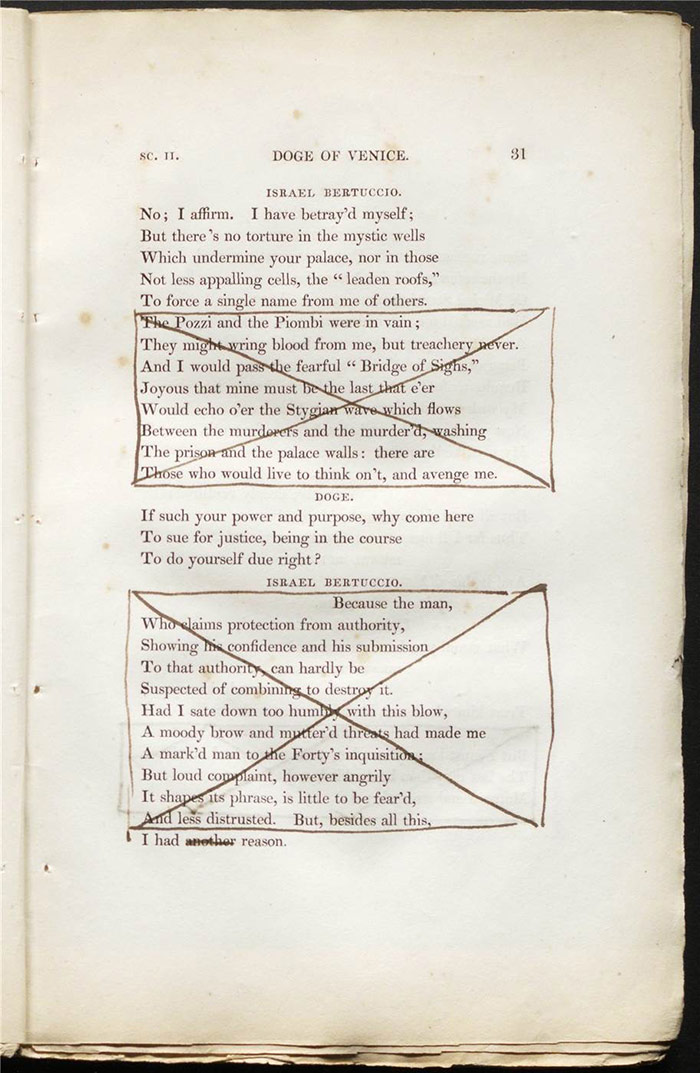

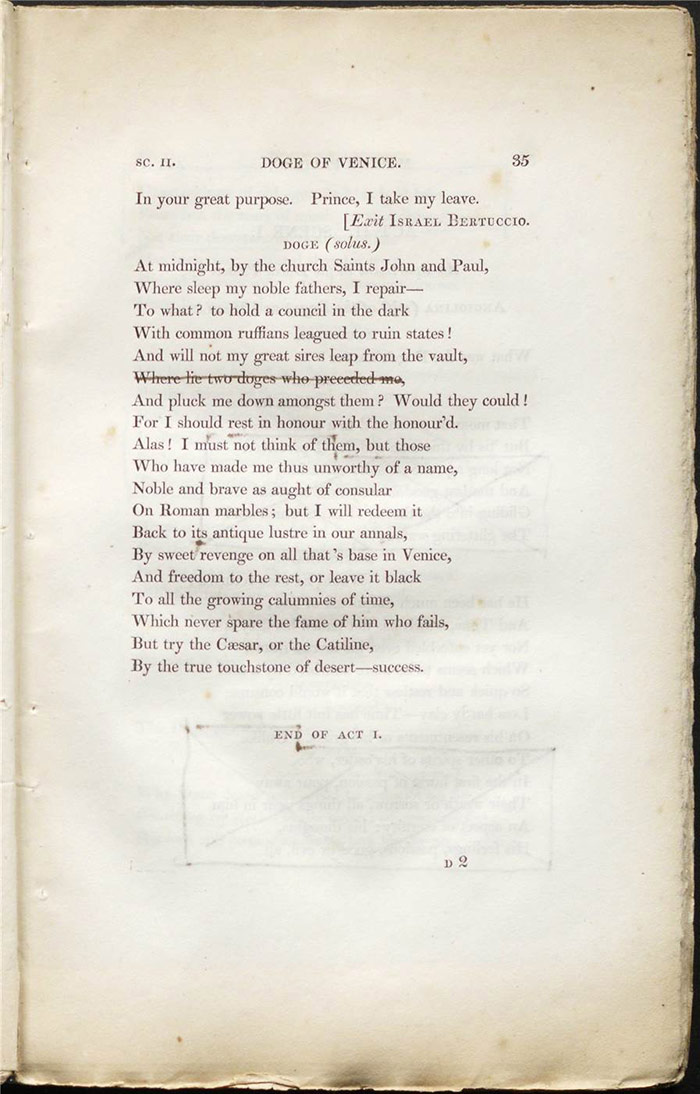

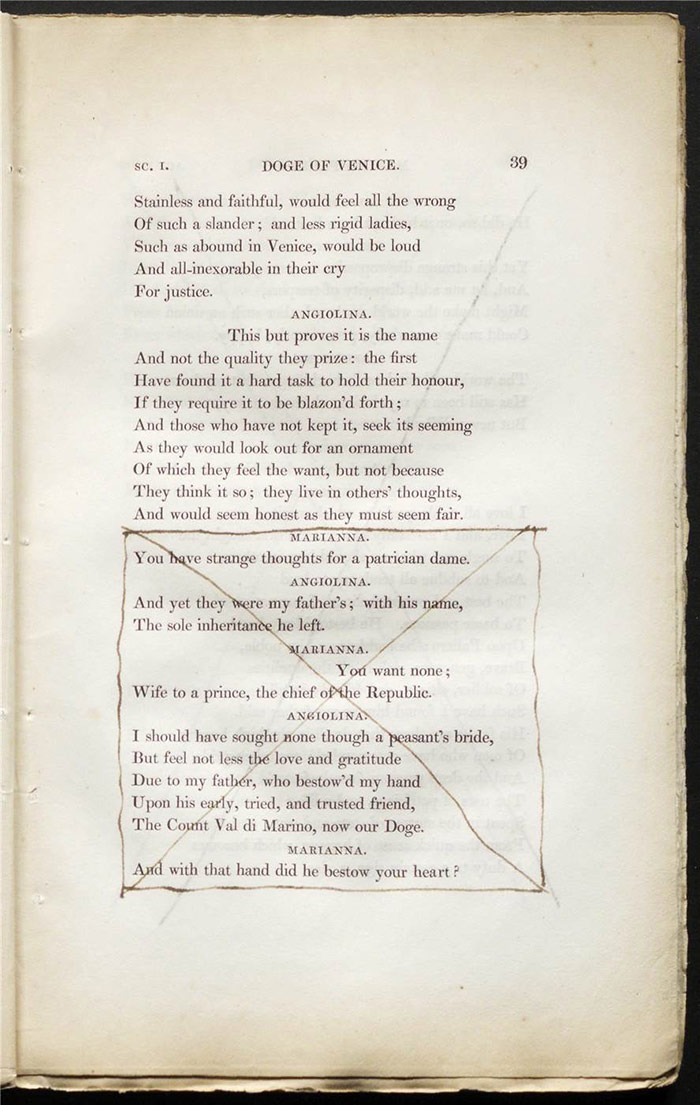

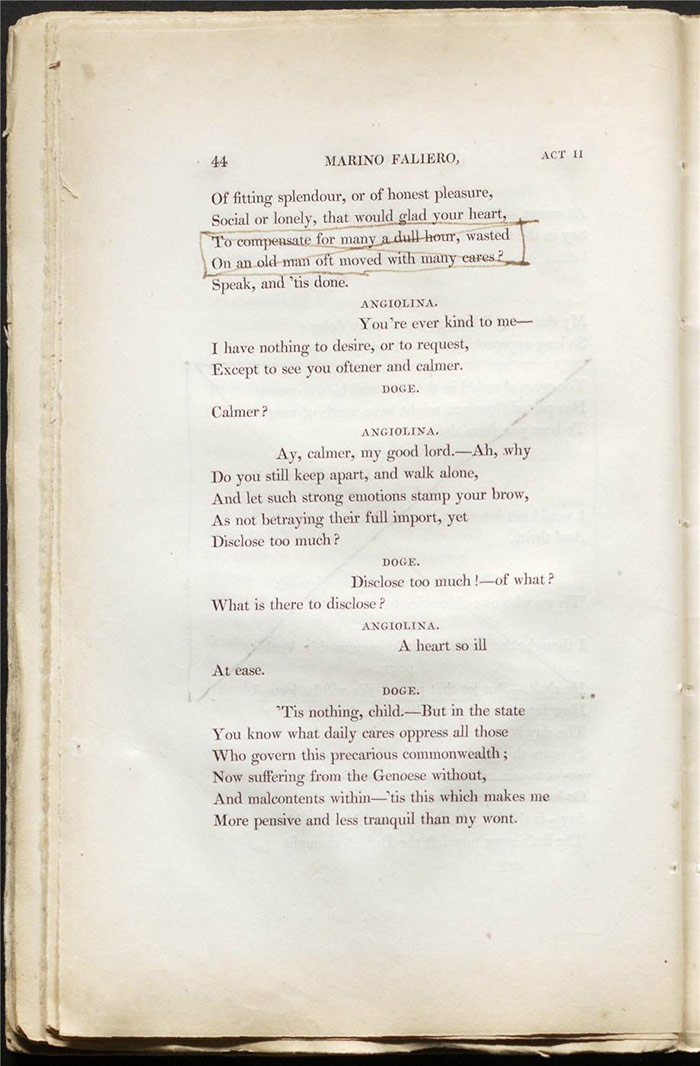

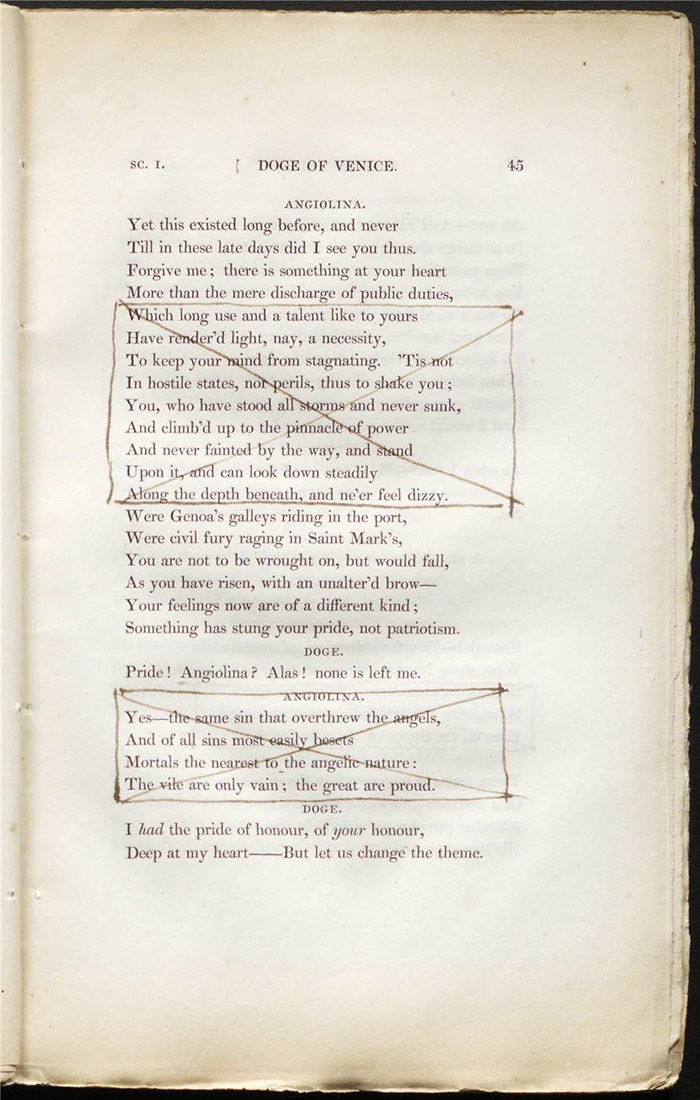

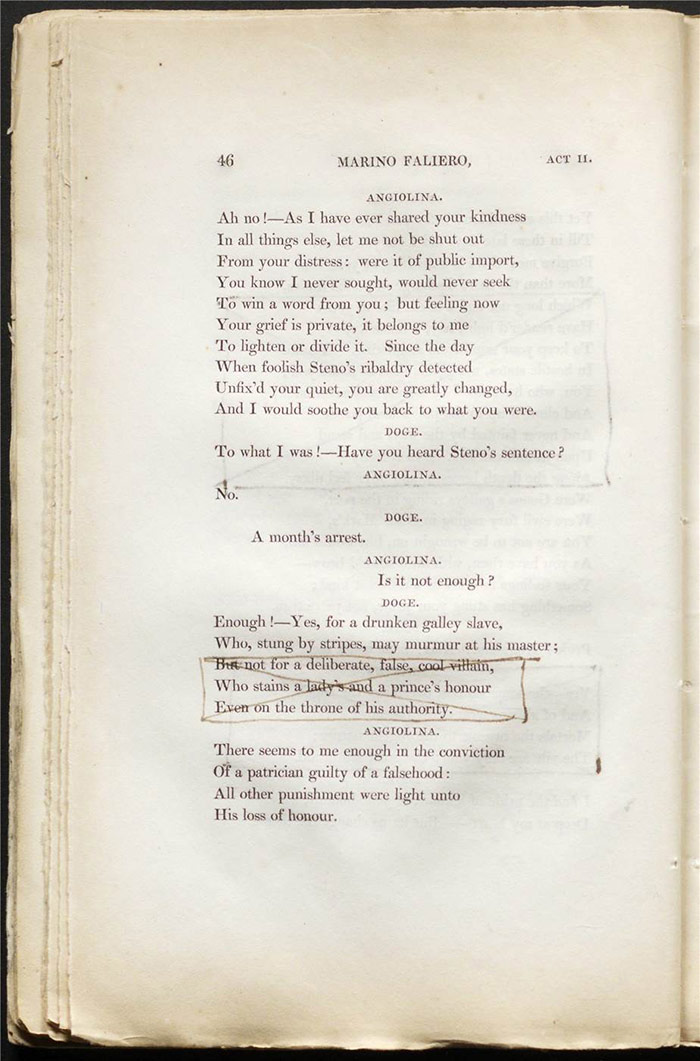

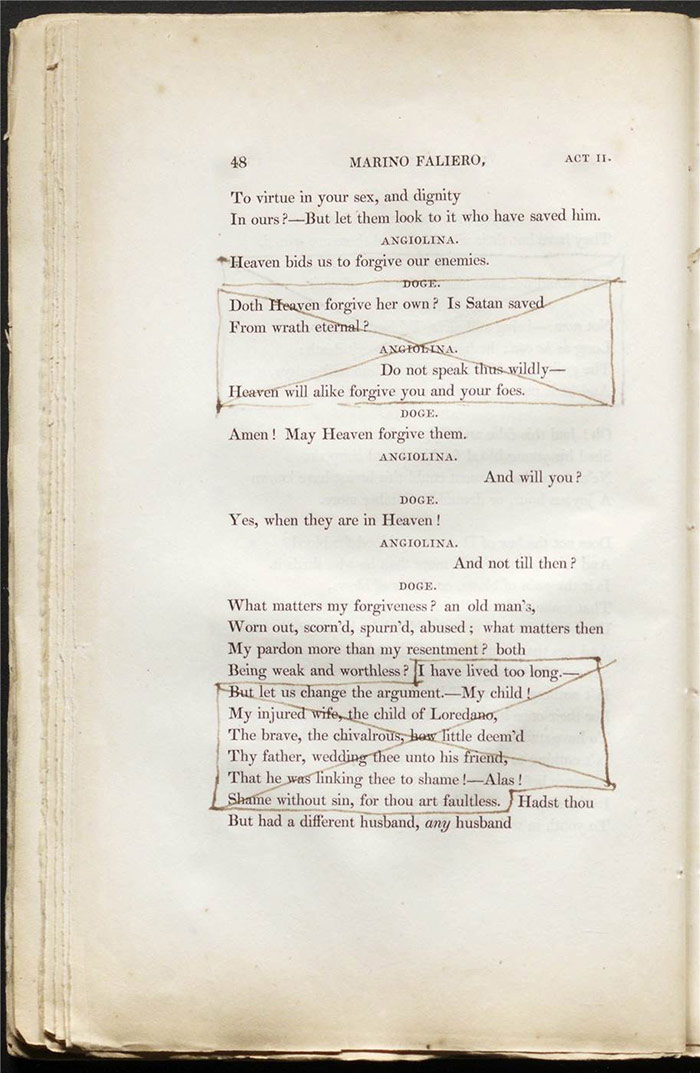

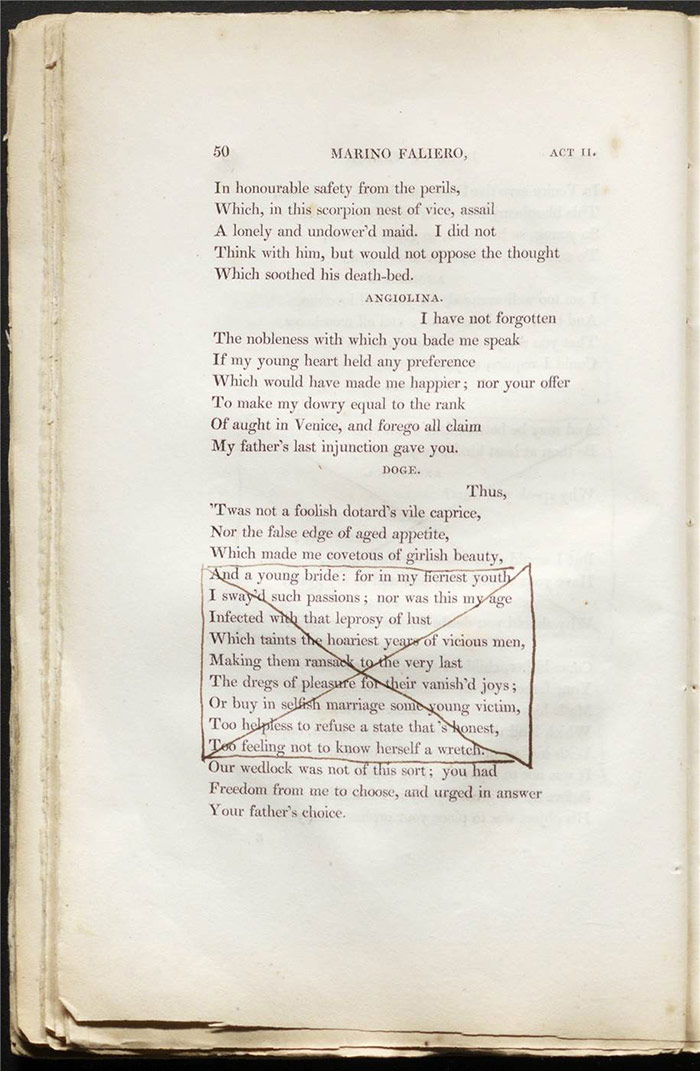

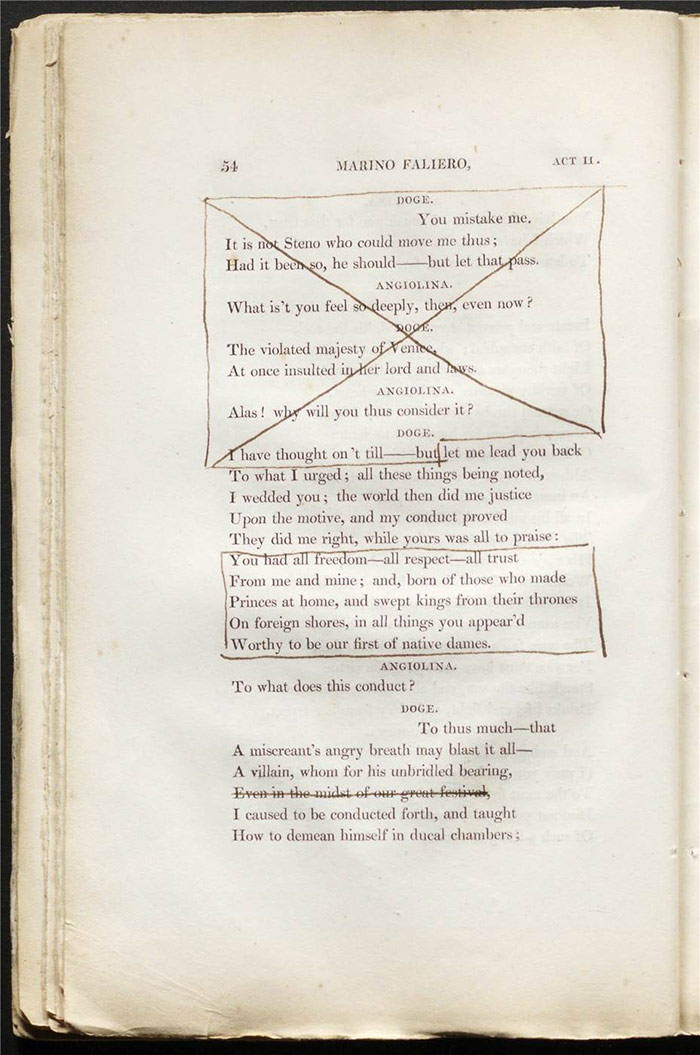

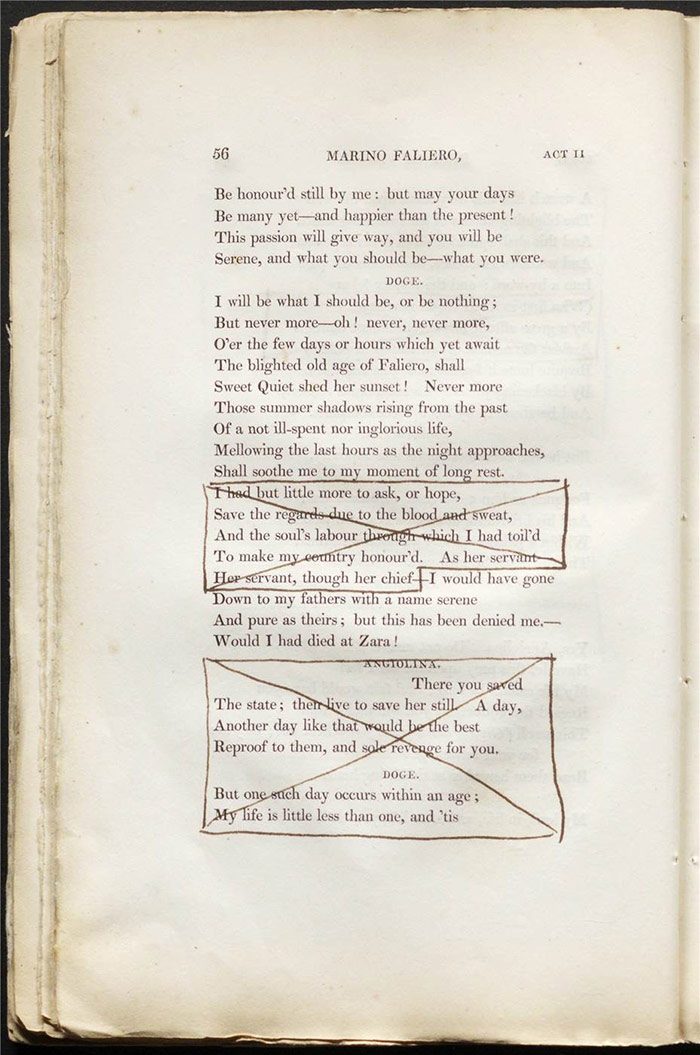

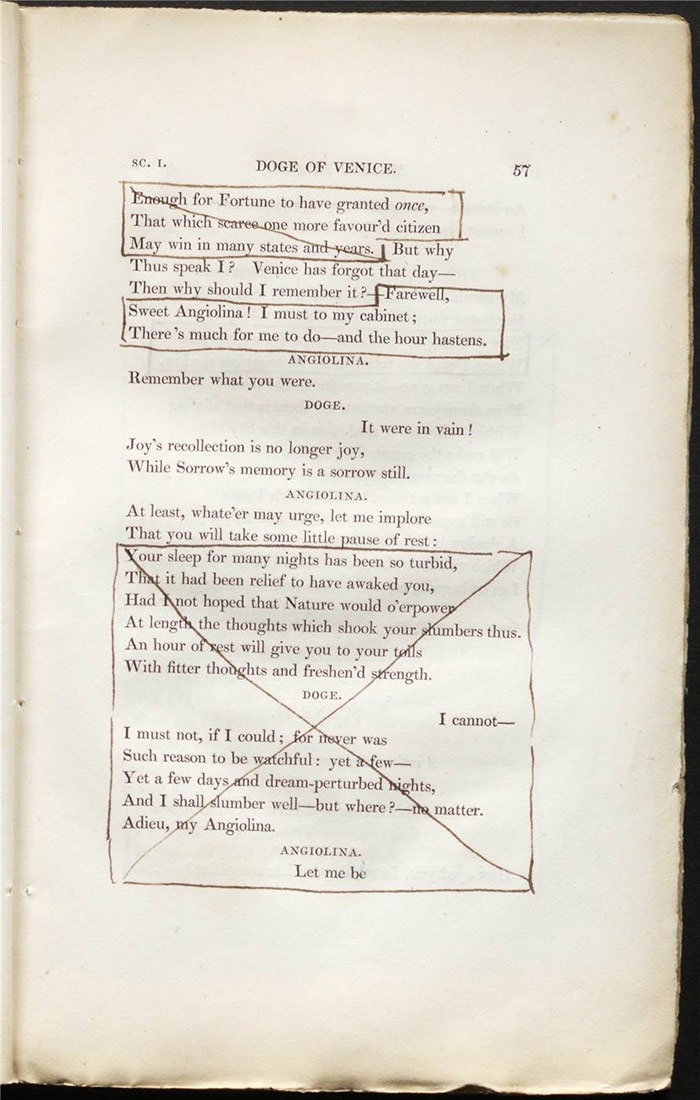

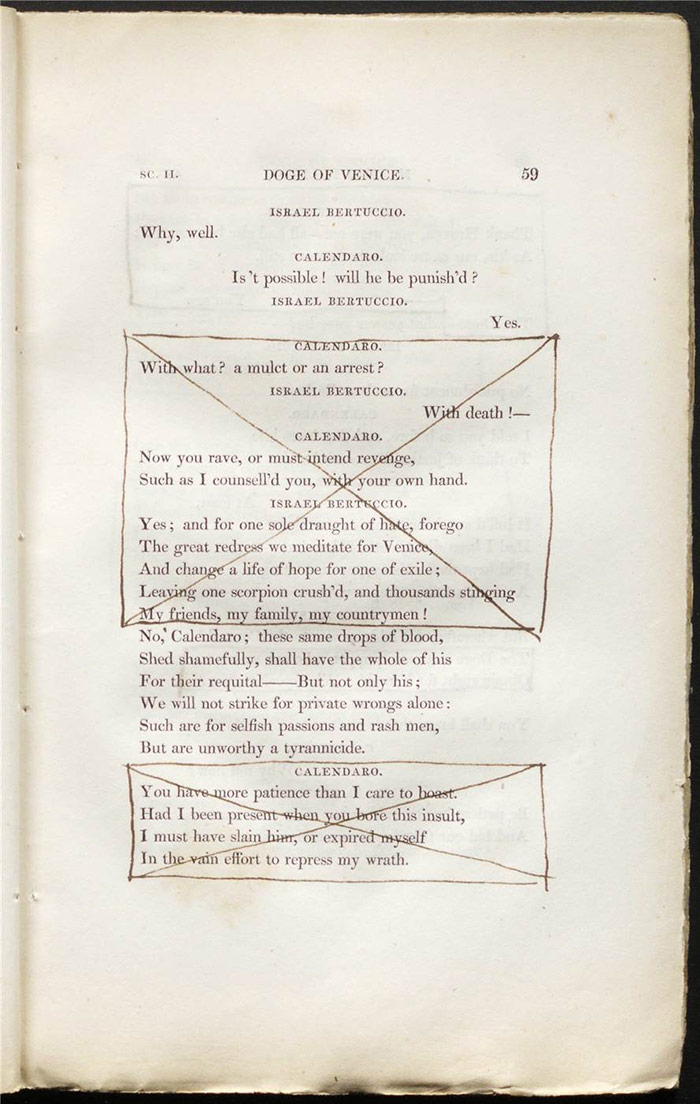

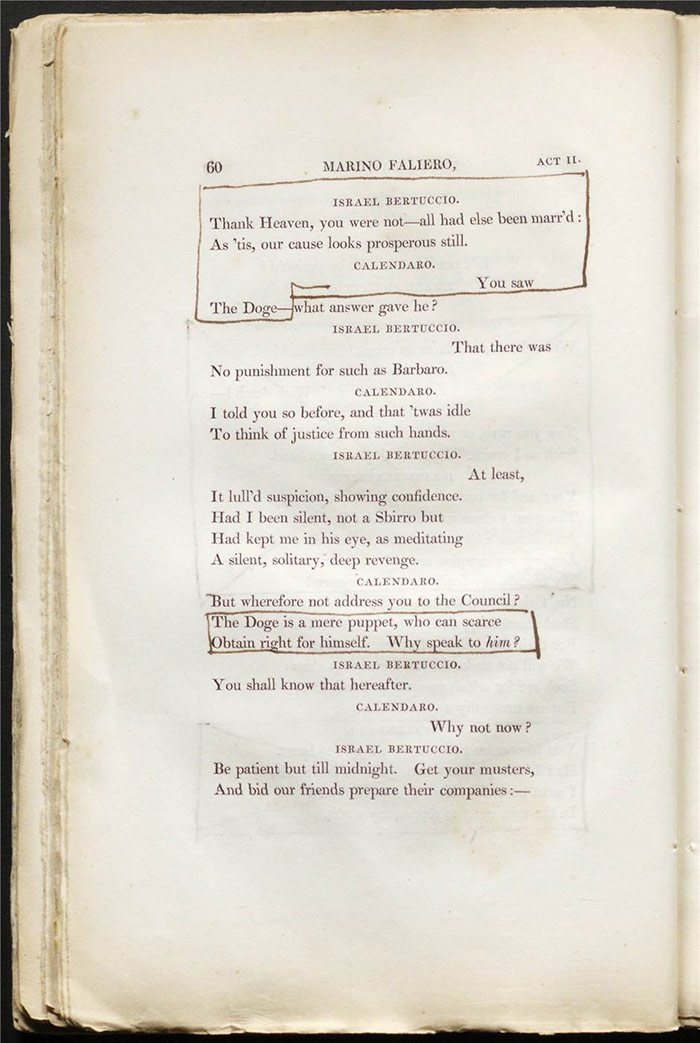

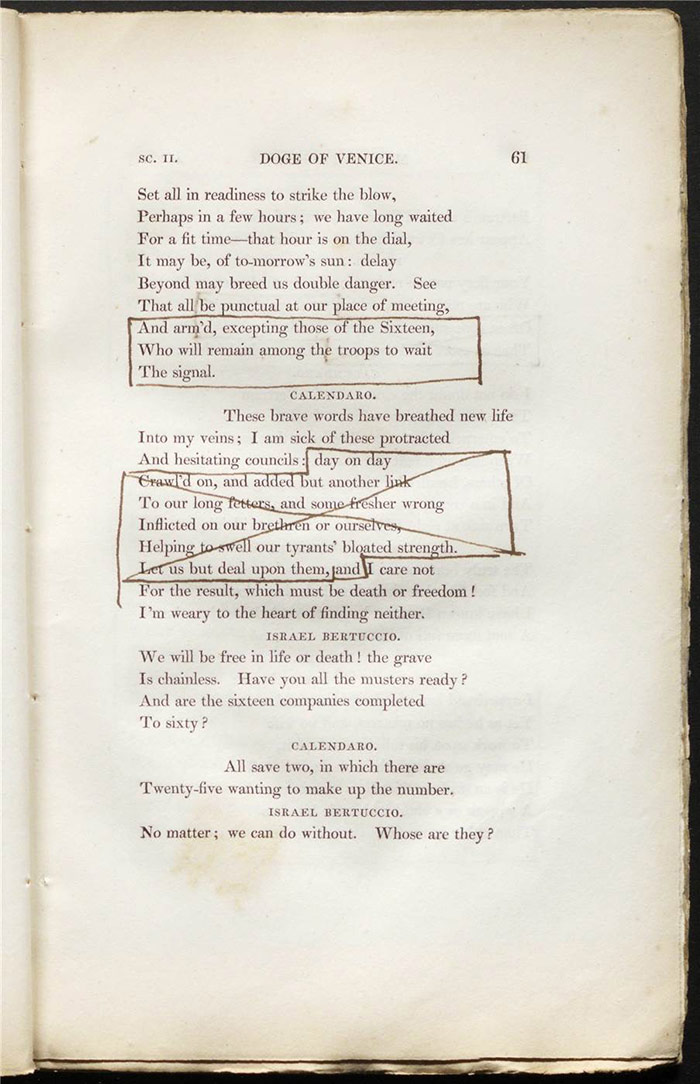

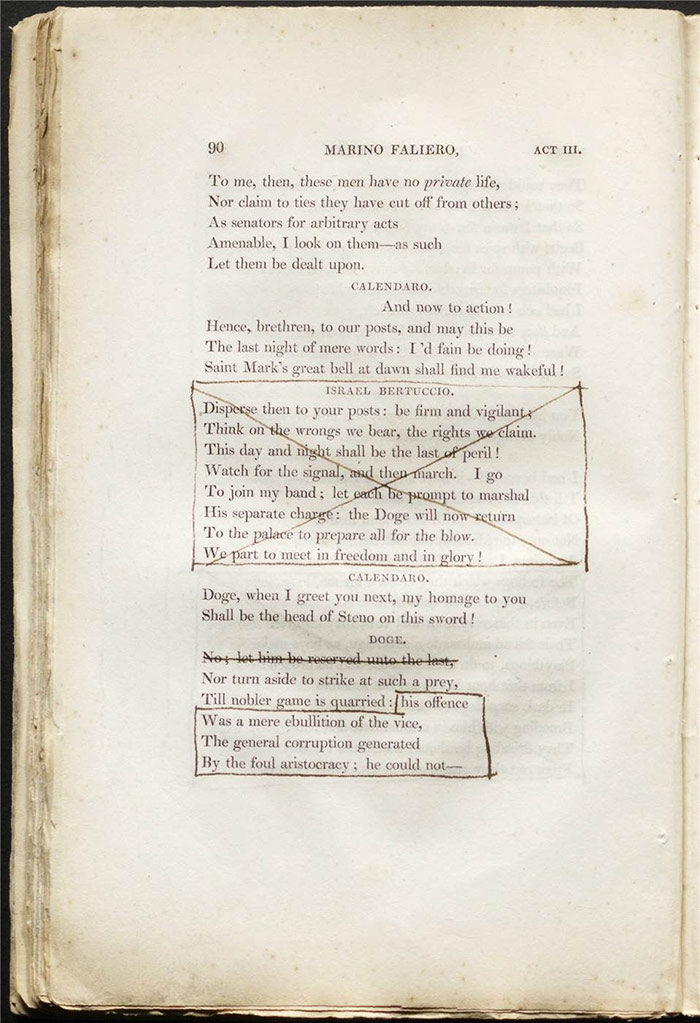

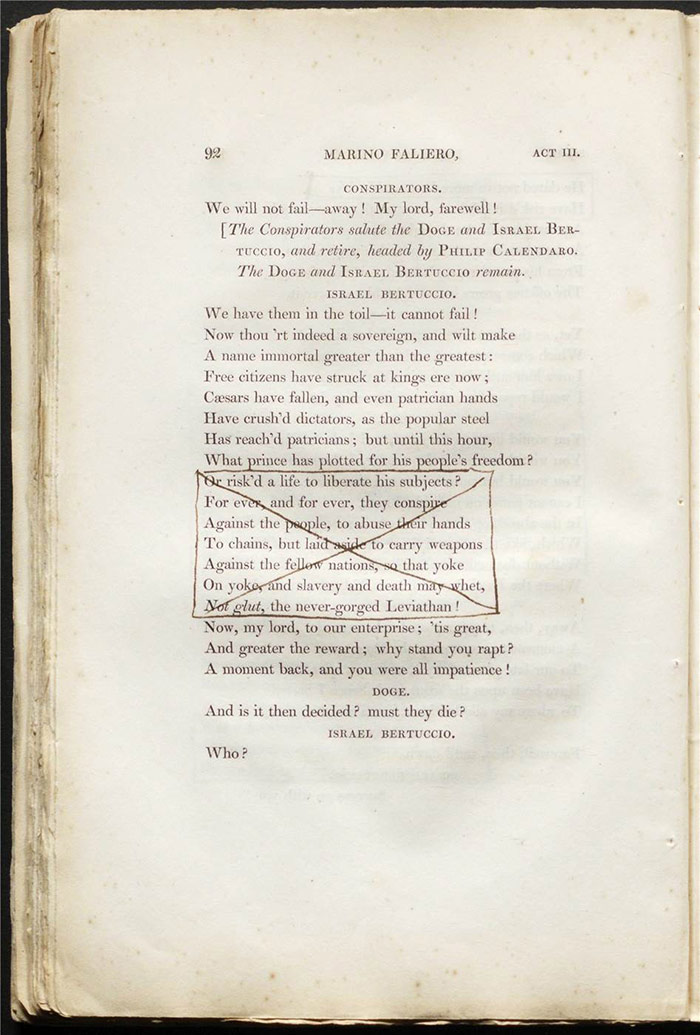

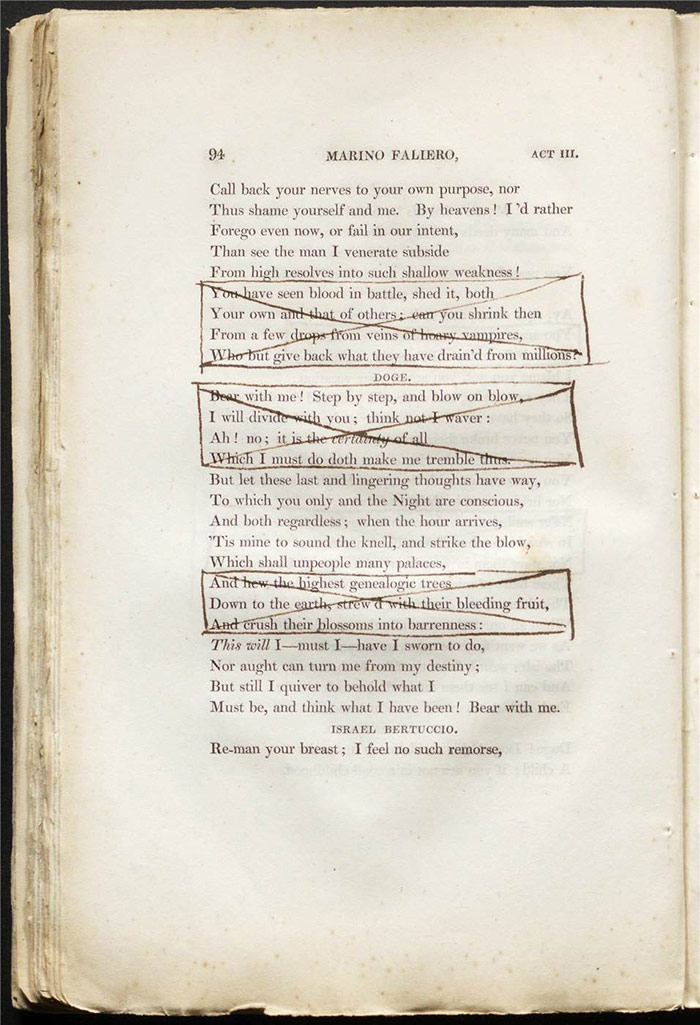

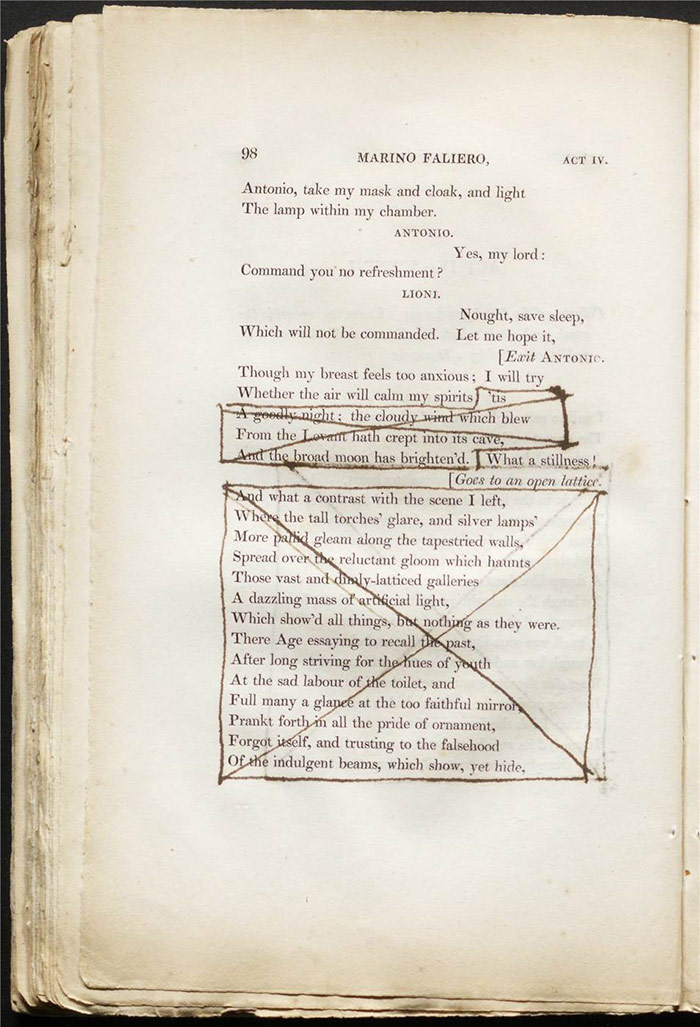

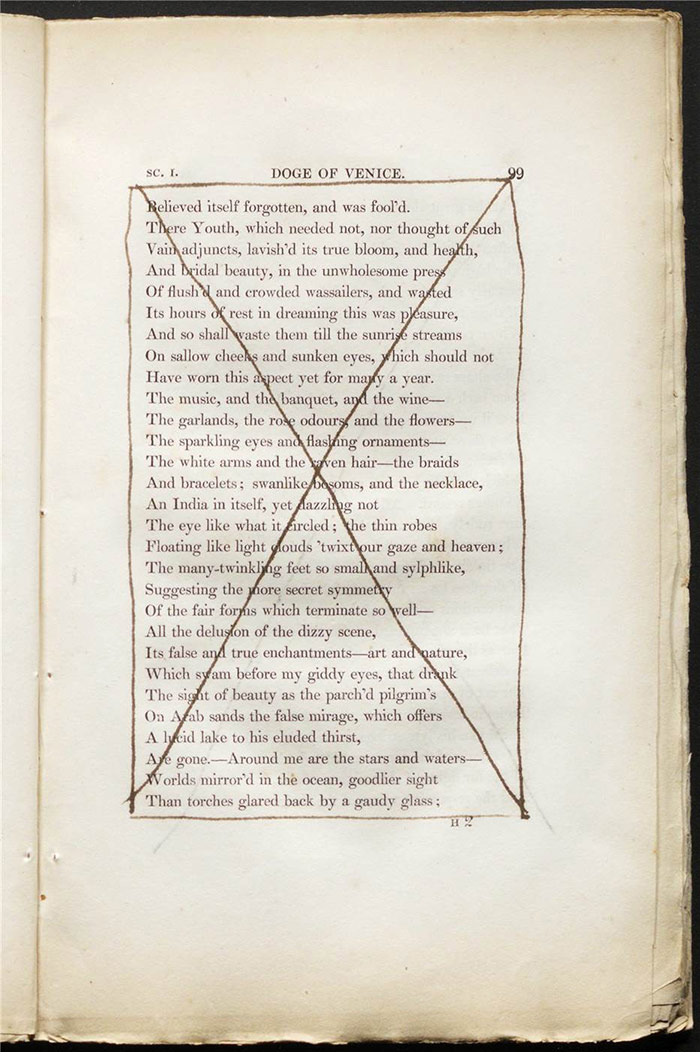

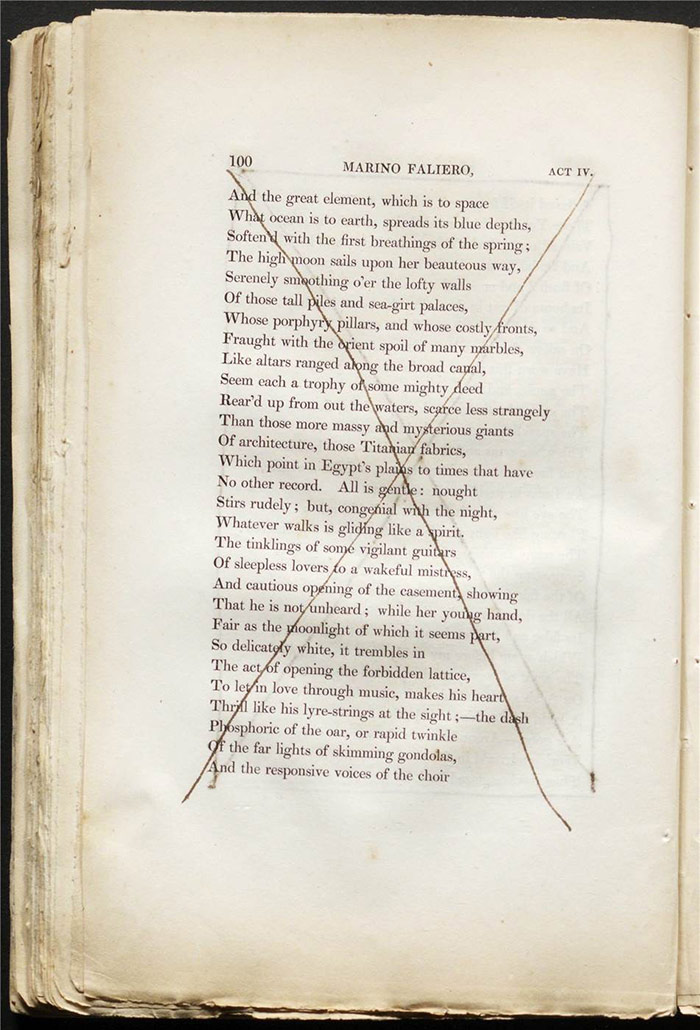

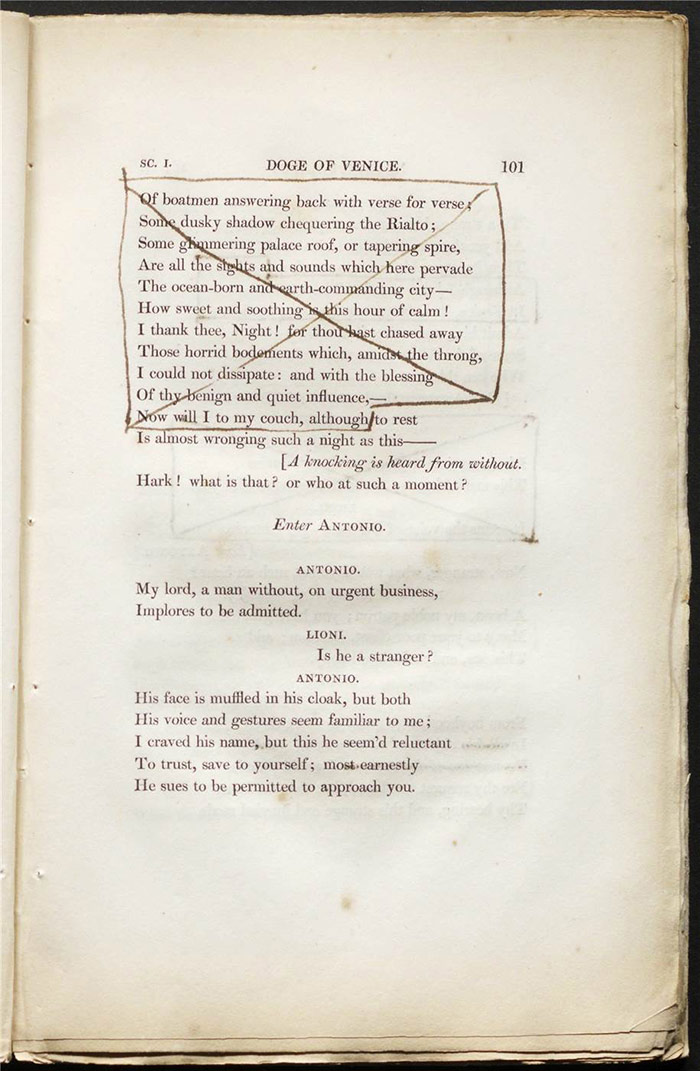

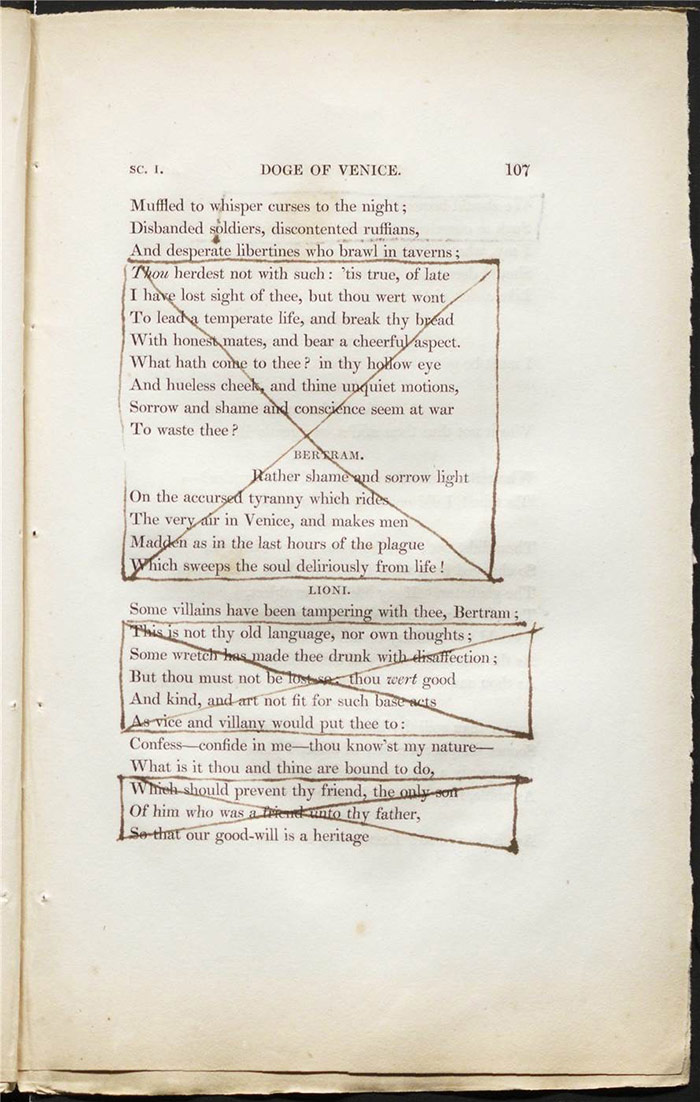

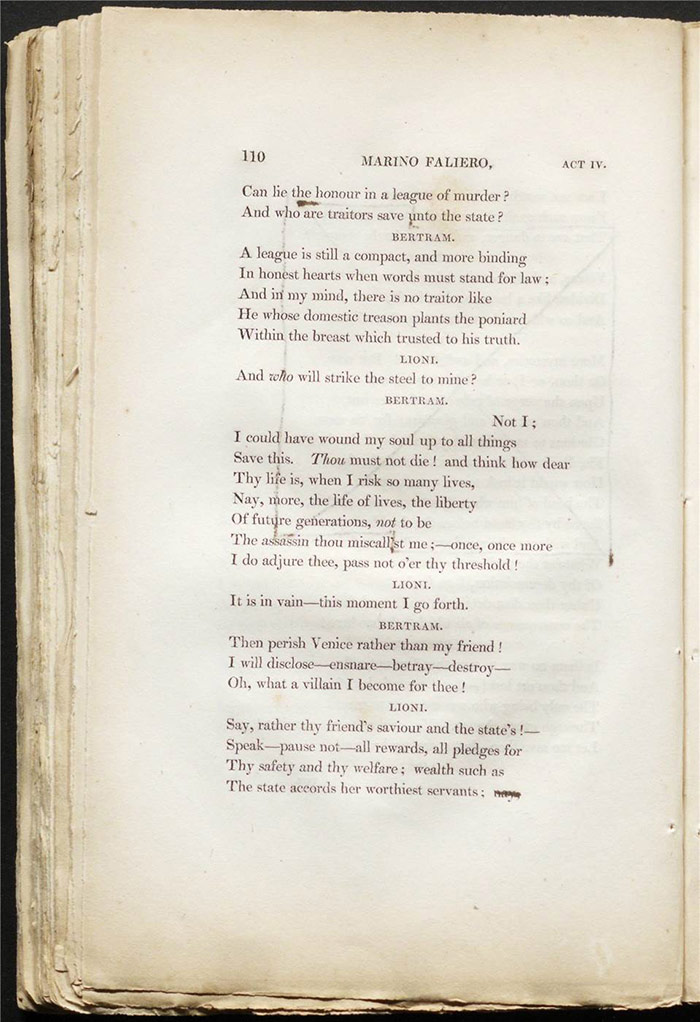

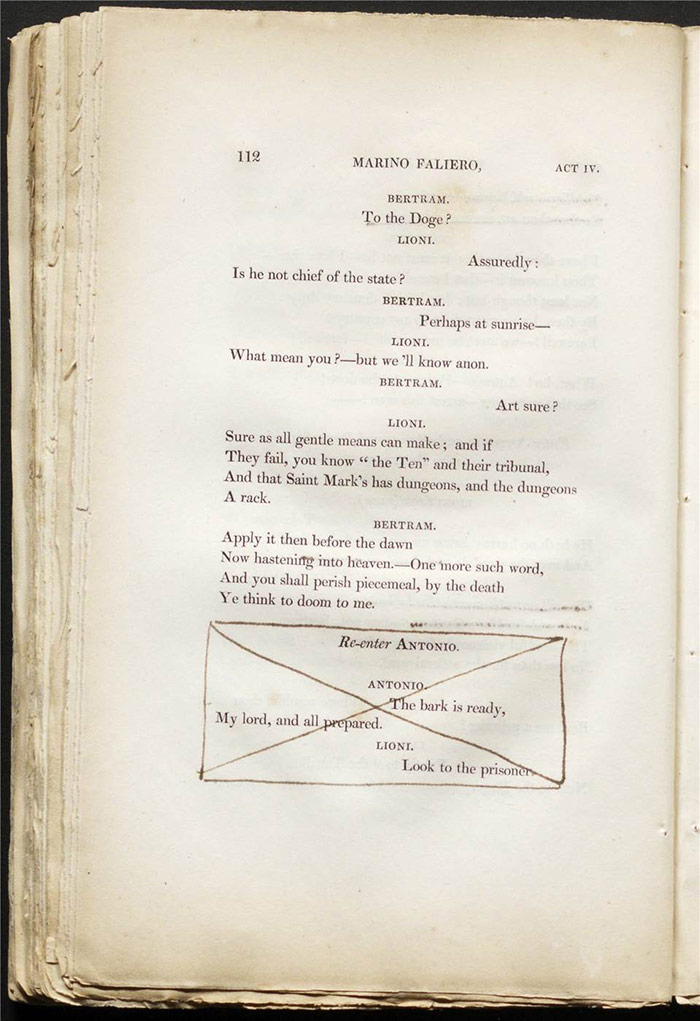

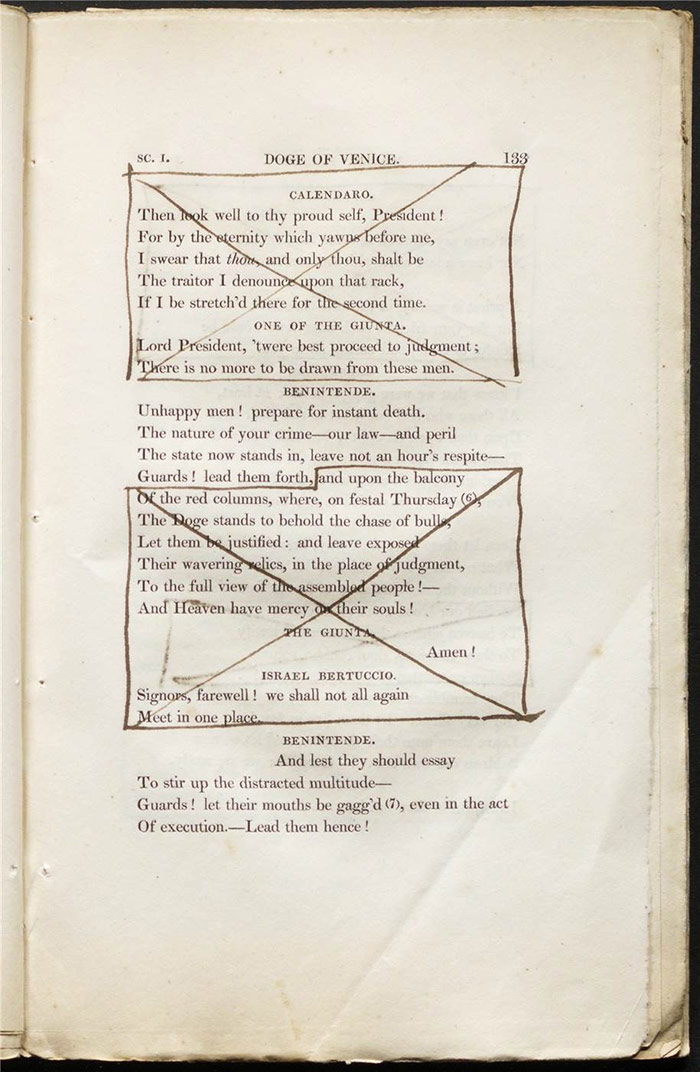

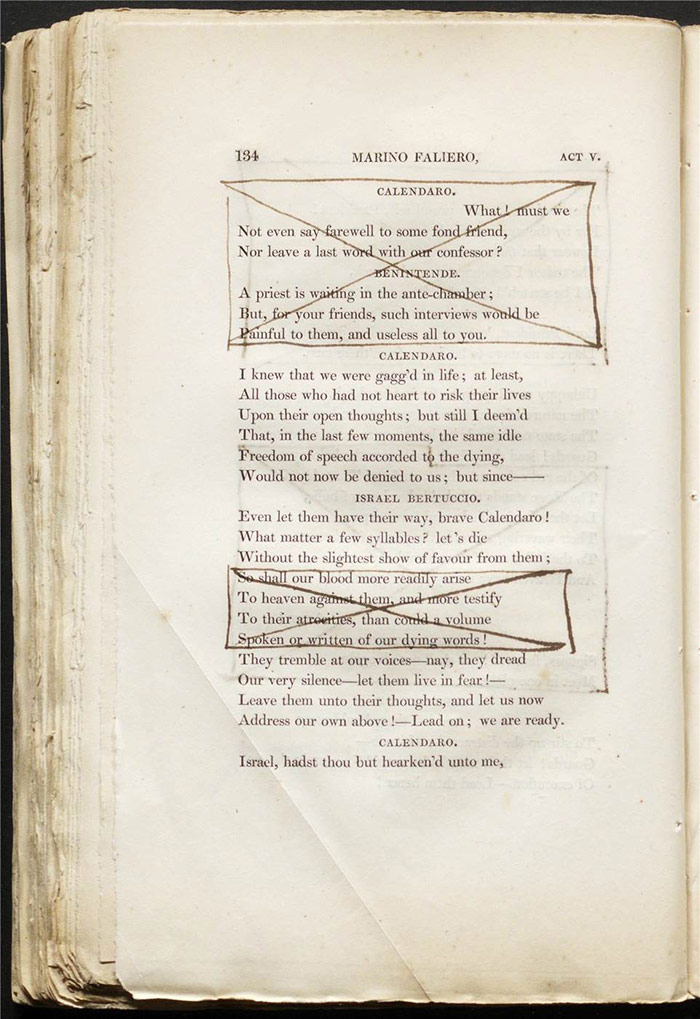

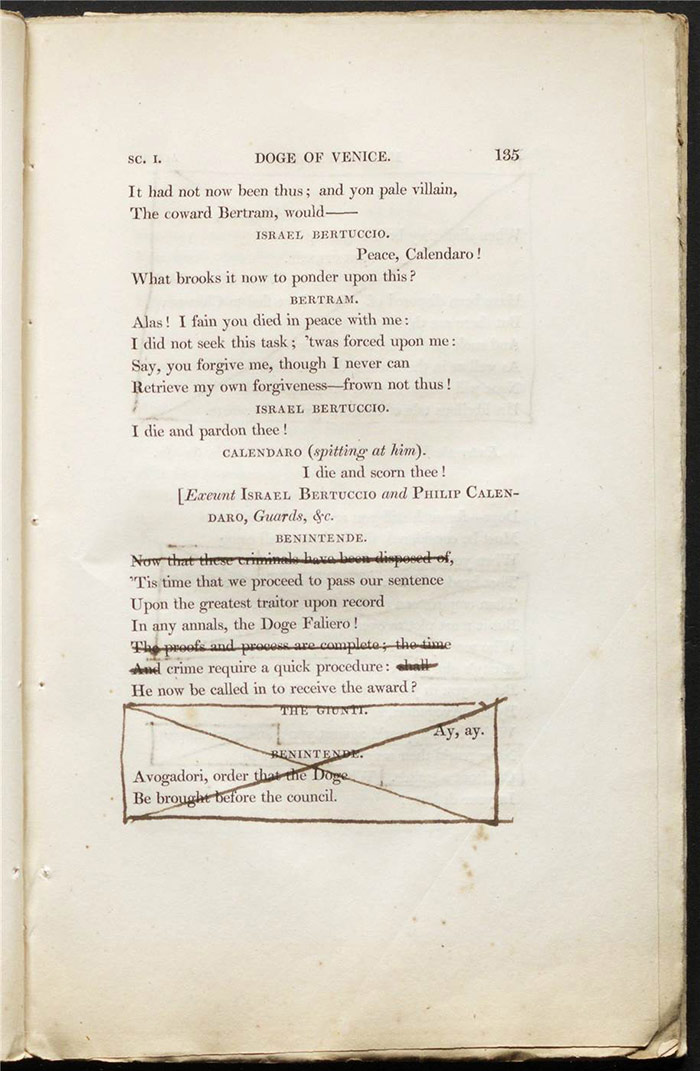

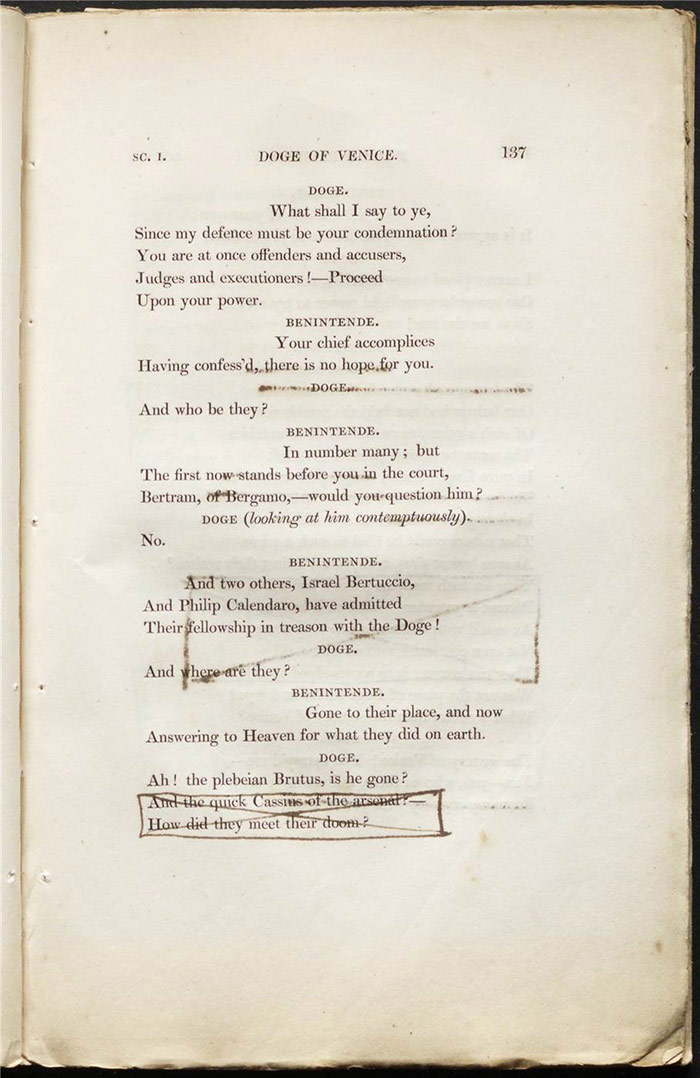

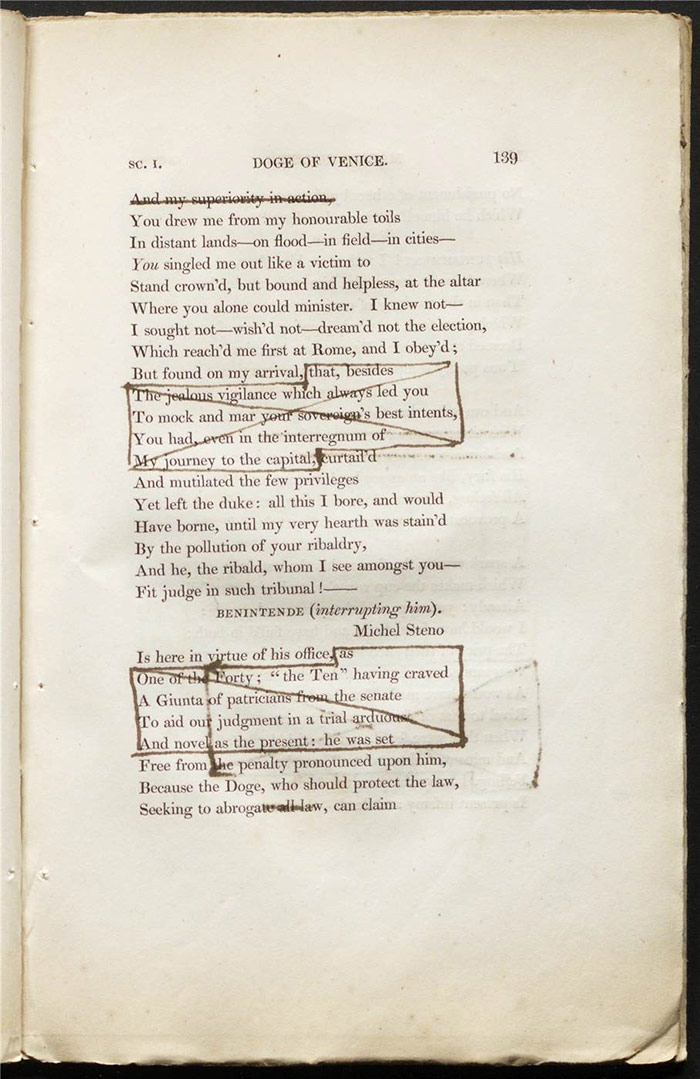

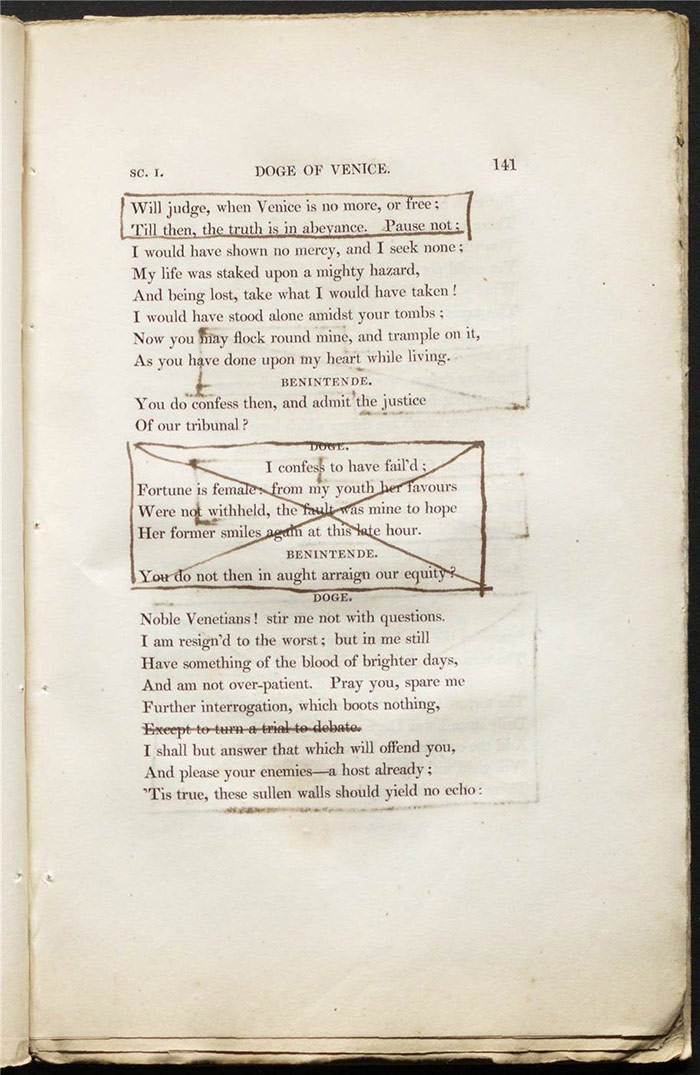

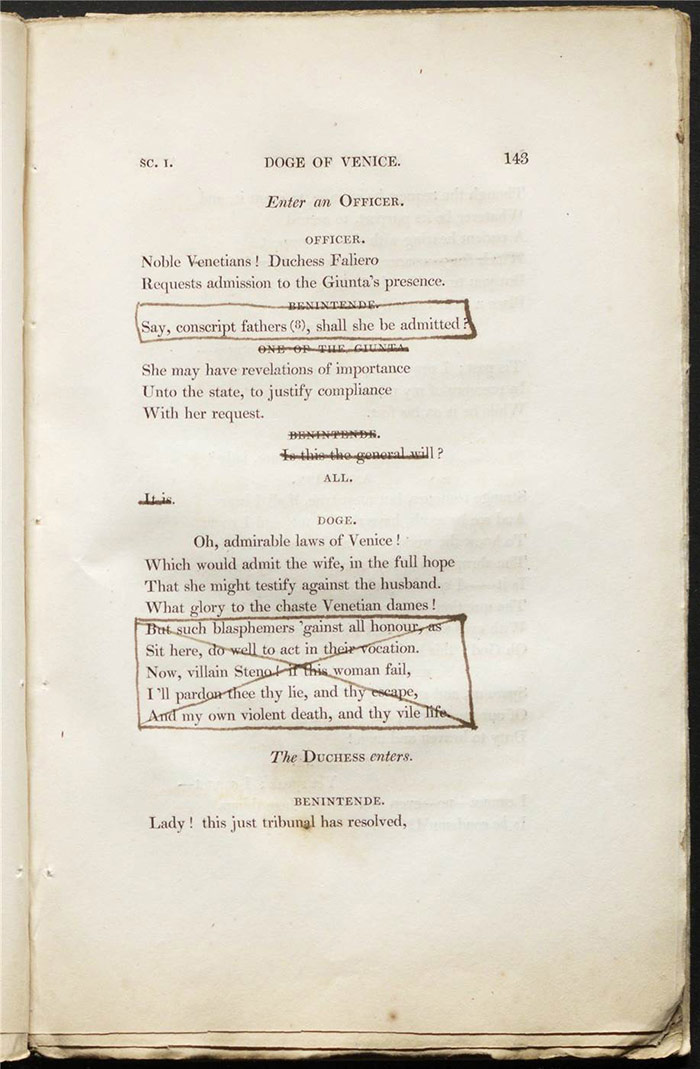

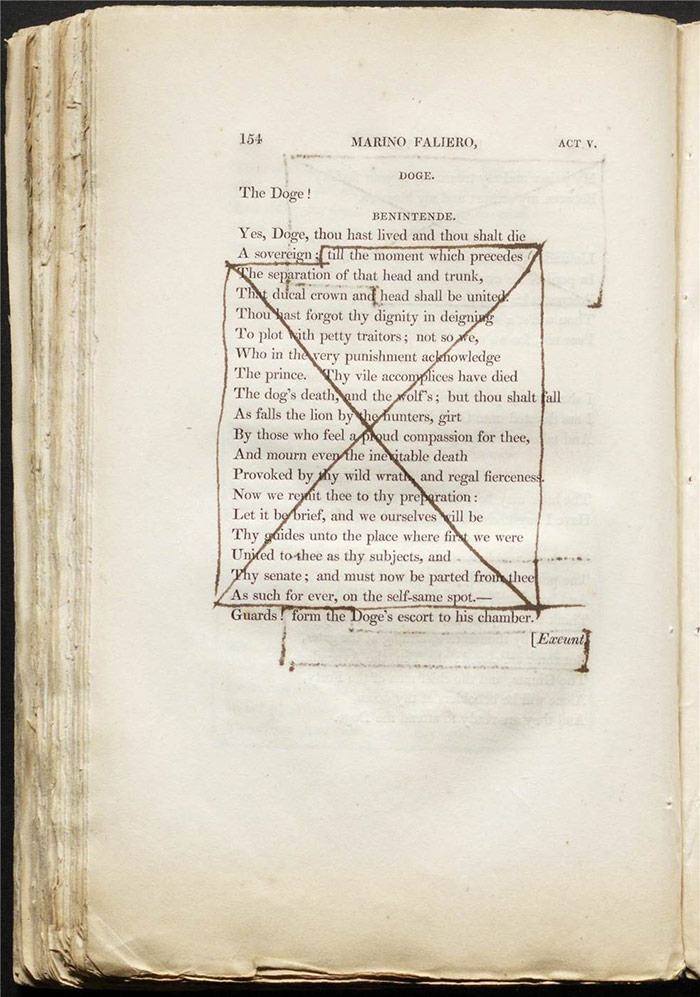

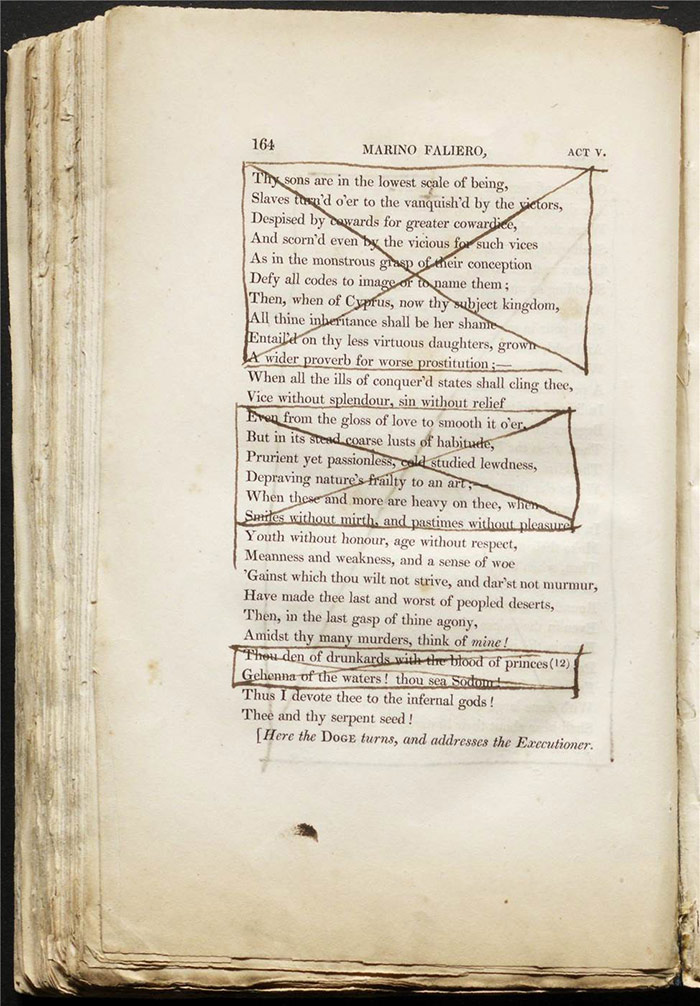

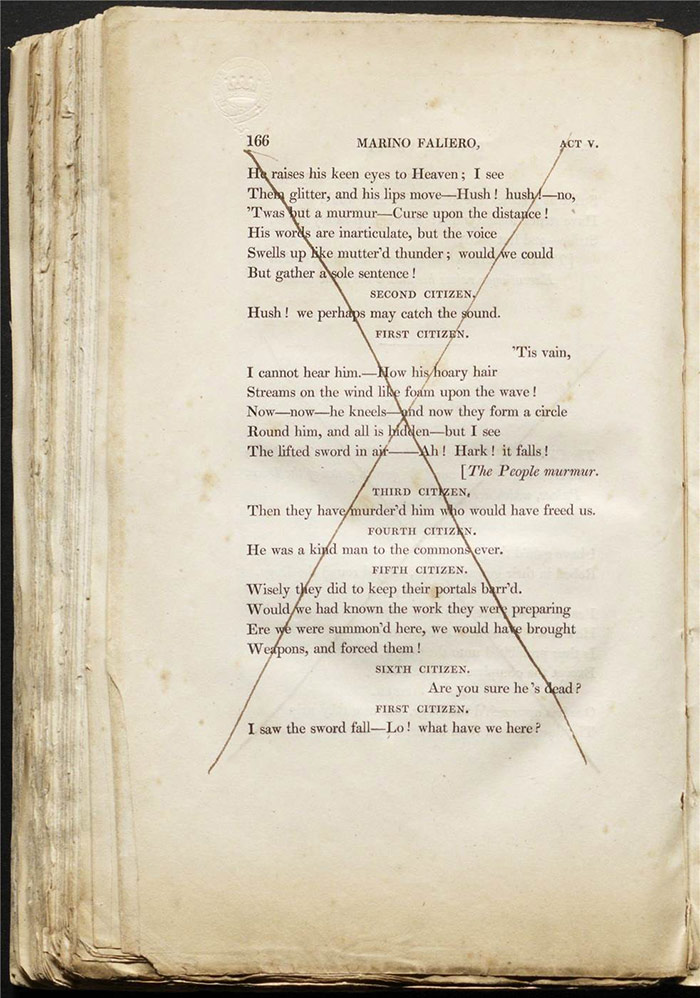

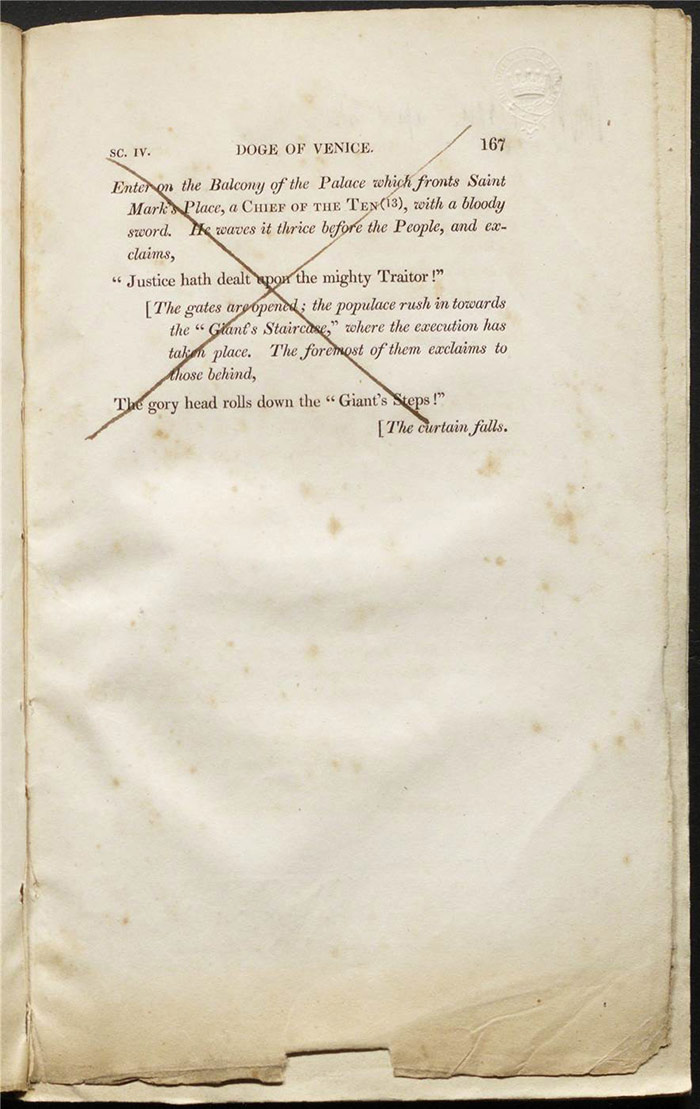

The play text (LA 2224) contains a very large number of excisions in pen. Lines of dialogue are crossed out sporadically and large block quotations are boxed and crossed out. These excisions relate in the main to political allusions and occur right throughout the text. We can be reasonably confident that Elliston is responsible for the boxed deletions. The complication is whether he is also responsible for the smaller cuts ie the lines of dialogue excised by having lines drawn through them. They appear to be from another pen and there is circumstantial evidence that Larpent is responsible; however, it is far from conclusive. Another challenging issue in relation to this play is to determine which cuts were made for dramaturgical reasons as opposed to concerns over political sentiment. Certainly, the fourth and fifth act in particular contain a number of cuts which seem motivated by a desire to cut the length of the play.

Unlike the other examples in this resource, Byron’s tragedy was published before it was performed: it was published on 21 April 1821 and performed on 25 April at Drury Lane Theatre. From the point of view of censorship, the play is also unusual in being censored on a number of fronts. Firstly, Byron himself, as is well known, tried to prohibit the performance (although critics have identified some ambivalence on his part) and was supported by his publisher, John Murray. Secondly, the manager of Drury Lane, Robert W. Elliston, sent in a copy of the play heavily excised in recognition that the play was politically incendiary. Finally, Eldon, the Lord Chamberlain, issued an injunction, after Murray’s intervention, but was argued out of it by Elliston.

It is essential to pay attention to the letter from Elliston to Larpent appended to the submitted text alongside Anna Larpent’s diary note in order to get the timeline related to the textual interventions correct.

I have been anxiously waiting for the publication of the Tragedy, which I now send to you, & which we have so curtailed that I believe not a single objectionable line can be said to exist

–

Despatch you will observe my dear Sir is to me of the greatest consequence, as all my artists will work all the night^ will be employed also all Monday night. I wish to produce it on Wednesday next, & as upon all occasions of emergency, you have been so obliging to put yourself out of the way, & this is a circumstance in which we are deeply interested, perhaps you will do me the favour to send me the licence as soon as possible, & at the same time to accept the heartfelt esteem of yours (n.p.)

The letter is dated 22 April; however, Anna Larpent’s diary entry for reading the text is 21 April. Given her diary has daily entries with dates and days noted, we may assume without much controversy that she is more reliable on this front. Moreover, Larpent’s Methodist inclinations were well known so it is improbable that Elliston would have troubled him on a Sunday. Finally, the reference to ‘Monday’ rather than ’tomorrow’ also points toward a Saturday composition.

As both these sources corroborate, Elliston made the excisions before the play was submitted. This is important as the wonderful story told in Memoirs of Elliston of how he chased Eldon around London in a hackney-coach and then on foot has led critics to believe that the amendments were made afterwards. Careful consideration of the evidence makes clear that the licence was issued on Wednesday,. This provoked Murray to appeal directly to Eldon who issued an injunction stopping the performance before Elliston dissuaded him:

[He] arrived in very time to catch his lordship by the skirts of his clothing, as he was mounting the steps of his own door. Here the defendant at once entered on the merits of his case, and his lordship declared the court sitting—Lord Eldon on the upper step, and Elliston on the pavement—the one all patience, the other all animation. The chancellor hesitated as to his previous order—Lord Eldon doubted—and Elliston redoubled the force of his argument. At length, he so far succeeded, that the judge suspended the injunction granted against the acting of the play for that night; but “Mind,” observed he, “you appear before me in the morning of tomorrow.” (Memoirs, 269)

This explains the handbill distributed at the performance: Murray had probably arranged this without knowing that Eldon had rescinded, temporarily at least, his injunction. The Lord Chancellor, the Attorney-General, Elliston and other legal actors met on 27 April to discuss the case (the detail can be read in The Times, 28 April). Elliston argued that the publication of the play meant it was fair game and further, that there was no injury done to either Murray or Byron. The opposing counsel insisted that this constituted a breach of Byron’s copyright. The subsequent performances of the play indicate that the injunction was lifted. However, tempers were still frayed: the Morning Chronicle for 23 May advertises ‘A Letter to R. W. Elliston, ESQ, Lessee of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on the Injustice and Illegality of his Conduct, in Representing Lord Byron’s Tragedy of Marino Faliero; with some Hints on the General Management of his Theatre’ with an epigraph ‘I’ll write to him a very taunting letter’ – Shakespeare Printed for John Lowndes’.

As for the internal censorship of the play itself, it was extensive. One critic has counted 1,462 lines deleted (Gardner, 483). There could be no surprise that so much of the text should be purged; as has been noted by many commentators, the play explores the tensions between Byron’s politics and class loyalties in the wake of the Cato Street conspiracy (a planned mass assassination of the British cabinet by political radicals; the plot was detected and five conspirators were transported and five more were hanged). It may also be possible to detect references to the Queen Caroline affair (she had returned to England in June 1820 seeking her right to be crowned queen; supporters rallied round her as a means to critique the king before she lost public favour). In a more general sense, there are references to corrupt judicial processes, a debauched nobility, and tyranny which would have troubled an Examiner of Plays in any scenario. The political thematics of the play are many, varied and explicit; the few examples which follow are offered as indicative highlights rather than an attempt to cover them all.

Before we come to the nature of the cuts, we shall consider the question of who was making them, particularly those lines struck through individually (as opposed to being boxed and crossed out in bulk with a large ‘X’. If we were to argue that Larpent—or indeed Anna Larpent—is responsible, we might begin by observing that the Examiner would be unlikely to let a play of this nature pass through his office unscathed, whatever Elliston might have done to reassure him in his cover letter. From what we know of Larpent and his habits, he would surely have added more excisions. Moreover, if we look at some of the cuts with a comparative eye, that is, looking at them alongside boxed cuts, we can draw some general conclusions. Firstly, these excisions might be categorized as ‘second order’ offences. Secondly, many of them are related to very mild religious references which were much more likely to be flagged by the Larpents than Elliston. Finally, they are usually much briefer, a sentence or two, sometimes just a word – again, this would be more in line with what we might expect from an Examiner.

Some examples will illustrate this argument. On p.14, the line ‘And villainous jests, and blasphemies obscene’ is struck through. It is the only line of a forceful and strongly worded speech to be deleted, probably as Larpent was uncomfortable with even the reference to blasphemy. On p. 22 these lines are similarly marked ‘Alas! my friend, you seek it of the twain / Of least respect and interest in Venice’. The ‘twain’ refers to God and the Doge and thus even the convolutedly worded suggestion that a people may not be deferential to God (and to political authority) is removed. On p.90 there is a puzzling ‘No; let him be reserved unto the last’, perhaps Larpent felt there was a Biblical feel to this line? There is a lengthy passage of almost two pages critiquing the nobility and its habits deleted on pp. 27-28 but just prior to it we have a very small excision ‘Wouldst thou be sovereign lord of Venice?’ (p.27) we might speculate that Elliston passed over this but Larpent detected an allusion to the British monarch rather than abstract political authority (see also p. 43 for the deletion of a reference to a levee). We might also confidently assert that Byron’s dangerous reputation surely fed into many of these cuts.

On the other hand, we must also admit that many of these types of cuts, particularly later in the play are groundless in censorship terms. They simply prune the text and this seems highly unlikely to be Larpent. Examples can be seen on pp. 102, 103, 111, 118, 120, 122, and 123. It is possible of course that both Elliston and Larpent made cuts of this nature. In any case, as is usual, we cannot be definitive.

We can turn now to the thematic nature of the censorship. Any reference to the judicial process, relating to the trials of Steno or Faliero, being unfair, biased or reflecting the fallibility of the judges are excised. Also eliminated are threats issued to the judiciary or any suggestion that a verdict might be challenged. Some varying examples can be found on p. 47, p. 133, p. 141. Here is one early example of a deleted speech when Bertuccio Faliero reports on the Steno trial:

The Forty are but men—most worthy men,

And wise, and just, and cautious—this I grant—

And secret as the grave to which they doom

The guilty; but with all this, in their aspects—

At least in some, the juniors of the number—

A searching eye, an eye like yours, Vincenzo,

Would read the sentence ere it was pronounced. (pp. 8-9)

Faliero’s actions are motivated by his strong sense that the Forty have disgraced themselves by their leniency towards Steno. Thus, he has many disparaging things to say about the nobility; Elliston was surely right to believe that these would not have been allowed through the Examiner’s office. Significant passages are cut on pp. 27, 45, 69, 90, and 92. Faliero’s speech to the conspirators, outlining the fallen state of Venice, is mostly removed (pp. 80-82) as are passages on the necessity for political cleansing (pp. 116-20). His final speech foretelling political change to those who have condemned him is also boxed out (pp. 163-64). Moreover, there is a strong prohibition on references to an unhappy people, city, or land or any sense that they might be subject to tyranny or that they might rebel (but see the opening of Israel Bertuccio’s speech on p. 29 for an example in this vein that surprisingly slipped through). The whole of the final scene when the people threaten to rise up (V.iv, pp. 165-67) is removed. See also pp. 21, 61, and 68.

Related to this are some excisions which are explicit references to violence, blood, or the justification of violence (pp. 76, 77, 94, 95).

There is also much care taken with references to sovereignty. The suggestion that the sovereign is a ‘citizen’ is deleted (p. 17) as well as the ‘sovereign’ already noted on p. 27. The idea that the Doge would be subject to the senate is also deemed problematic (p. 43) as is a reference to him as a ‘mere puppet’ (p. 60).

The second act exchange between the Doge and his wife Angiolina is worth particular attention. There are significant cuts to their dialogue. Some of these are related to Angiolina’s sense that her husband is now troubled and uncertain unlike his earlier self so there is a sense that this was commentary on the British monarchy (pp. 45, 57, 58). There are also a large number cut passages that refer to the queen’s character or which offer an introspective reflection on their marriage. For instance, on p. 54 the Doge tells his wife:

You had all freedom—all respect—all trust

From me and mine; and, born of those who made

Princes at home, and swept kings from their thrones

On foreign shores, in all things you appear’d

Worthy to be our first of native dames.

Similar passages on pp. 39-41, 48, 51, 52 also seem to hint back at the Queen Caroline affair and the royal marriage, and they are cut. There is a passage detailing the Doge’s early lust on p. 50 which is also removed.

Finally, we will reiterate that there are a number of cuts that seem to have been made for dramaturgical purposes. One example is the removal of virtually all of Lioni’s speech at the opening of act IV (p. 97). Evidently, this was deemed superfluous and removed. It is striking that this speech is published in the Morning Chronicle (21 April) as an example of the quality of the play’s poetry.

Further reading

Bernard Beatty and Robert Gleckner (eds), The Plays of Lord Byron: Critical Essays (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1997).

Byron, Lord, George Gordon, Marino Faliero Doge of Venice An Historical Tragedy (London: John Murray, 1821).

[available on HathiTrust.org]

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 107.

David V. Erdman, ‘Byron’s Stage Fright: The History of his Ambition and Fear of Writing for the Stage’, ELH 6:3 (1939), 219-43.

John Gardner, ‘The Case of Marino Faliero’ in The Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Theatre, 1737-1843 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 479-97.

Leslie A. Marchand (ed), Lord Byron Selected Letters and Journals (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1982)

Jerome, McGann, ‘Byron, George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron Byron (1788-1824’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4279, accessed 15 February 2019]

George Raymond, Memoirs of Robert William Elliston Comedian (London: John Mortimer, 1845), 267-75.

[available on HathiTrust.org]

Michael Simpson, Closet Performances: Political Exhibition and Prohibition in the Dramas of Byron and Shelley (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), esp. 172-89.