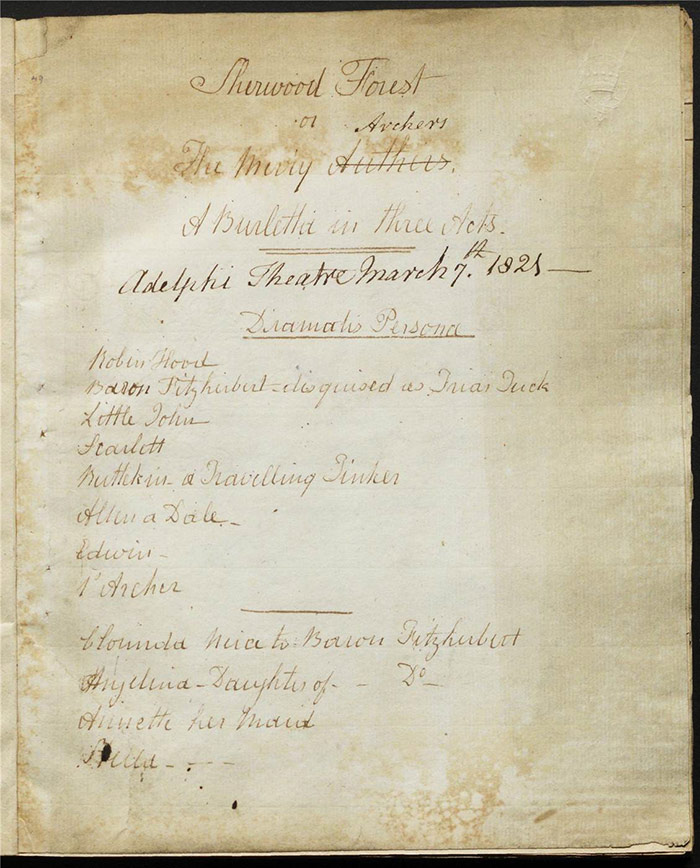

Sherwood Forest; or, The Merry Archers (1821) LA 2217

Author

James Robinson Planché (1796-1880)

Planché was a Londoner with a Huguenot background. He wrote his first play, an interlude, for a private theatre but comedian John Pritt Harley arranged to have it staged at Drury Lane in 1818. This introduction, and the support of Robert Elliston and Stephen Kemble, provided an avenue to pursue a theatrical career and The Vampire, or, The Bride of the Isles (Lyceum, 1820) was his first significant success. He spent the period 1822-1828 employed as a stock author at Covent Garden under Charles Kemble but he also continued to contribute plays to some of the minor theatres. In one of his more notable achievements, he persuaded Kemble to stage King John in historically appropriate costume in 1823 which changed nineteenth-century theatrical practice. This scholarly approach would earn him election to the Society of Antiquaries in 1829.

He jumped ship to Drury Lane in 1828 where he wrote a number of history plays, again with period costume developed from research. He contributed to Eliza Vestris’s inauguration as manager of the Olympic in 1831 and he was to be professionally involved with her subsequently for over two decades. This was a very prolific period of his career and he developed 36 pieces in seven years for the Olympic, Lyceum, and Covent Garden. He was a founder member of the Garrick Club in 1831. He gave evidence to the Select Committee in 1832 where he said that his most successful pieces of the 73 he had written to that date were Charles XII (1828), The Brigand Chief (1829), The Woman Never Vexed (1824), Maid Marian (1822), and The Rencontre (1827).

He had considerable success writing for the Haymarket in the mid-1840s and advised the royal family on historical dress for Buckingham Palace’s costume balls before he moved to Kent in 1852 to be with his daughter. He continued to write for the London theatres and returned to the city in 1854 when he was appointed Rouge Croix pursuivant at the College of Arms. In his capacity as herald in service to the Crown, Planché carried out diplomatic missions to Lisbon, Vienna, and Rome in the 1850s and 1860s. He wrote a pamphlet titled Suggestions for Establishing an English Art Theatre (1879) in support of the idea of developing a theatre which would not simply reflect public taste. His final work for the theatre were the songs for a Boucicault opera Babil and Bijou (1879). He died in 1880 and it is thought he wrote about 180 pieces for the theatre in all.

Plot

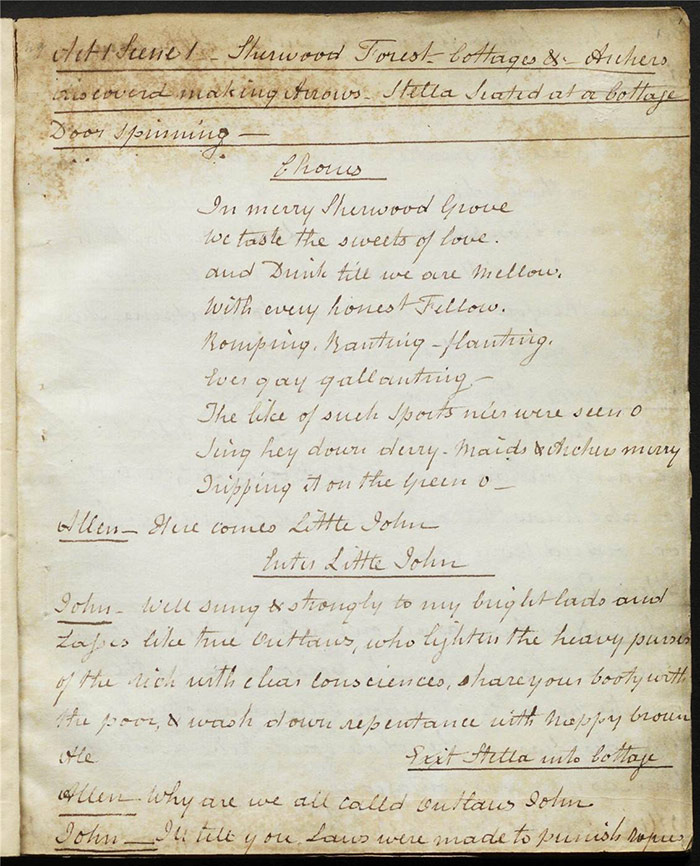

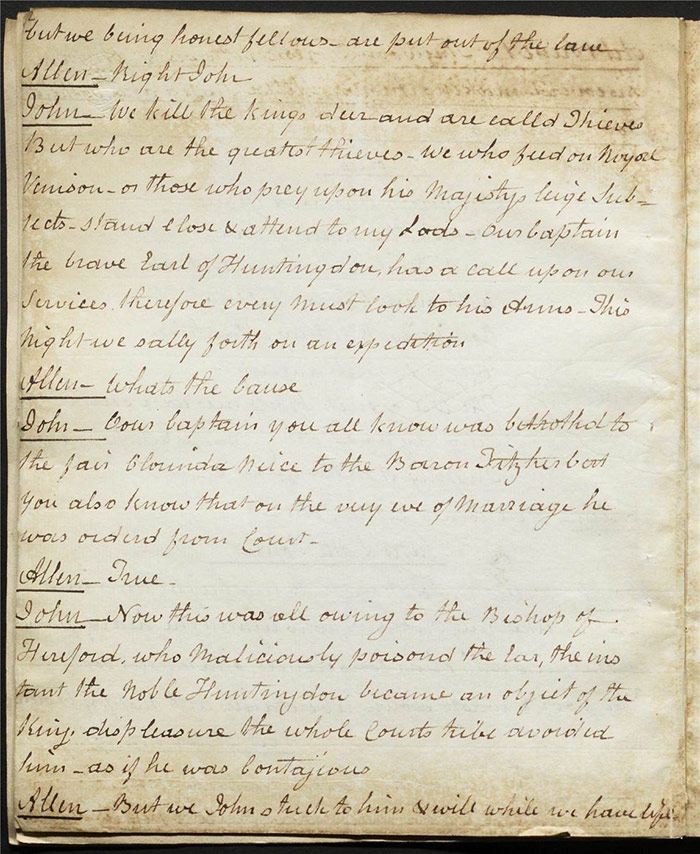

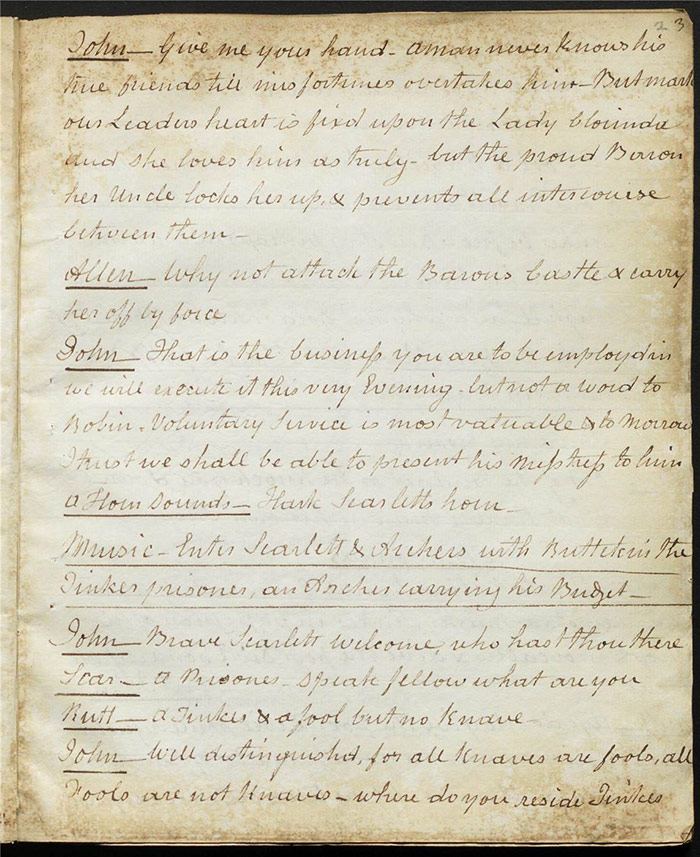

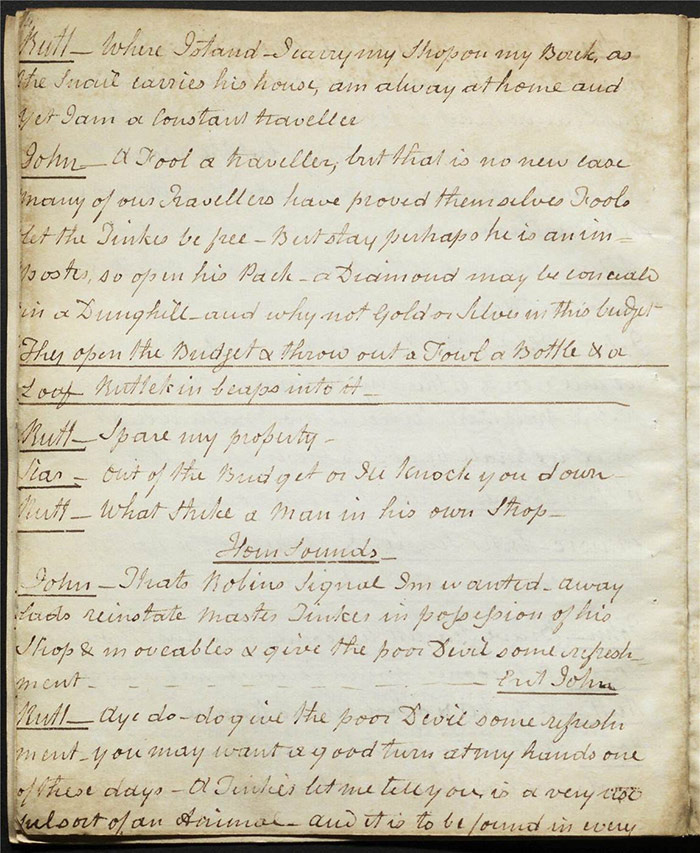

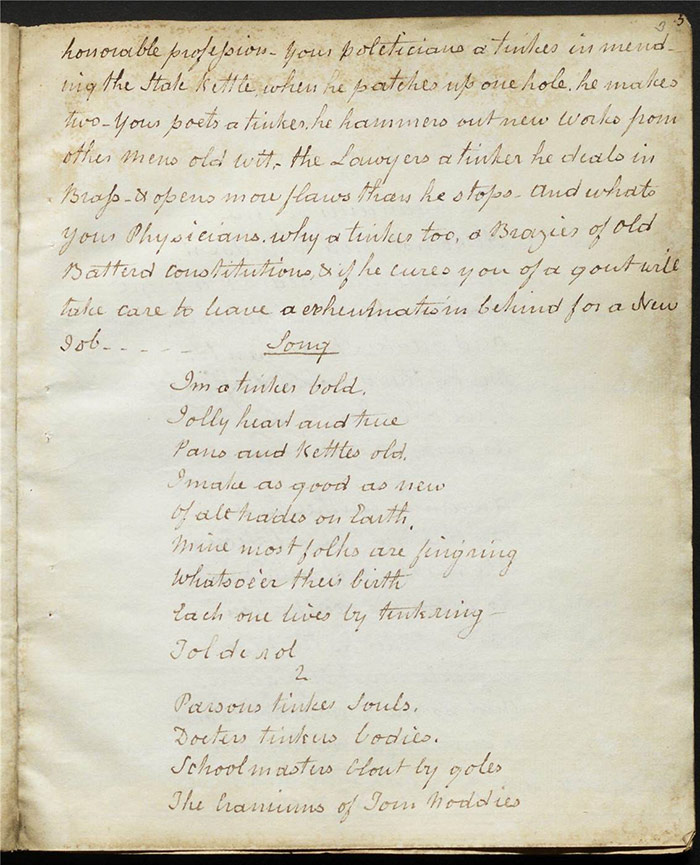

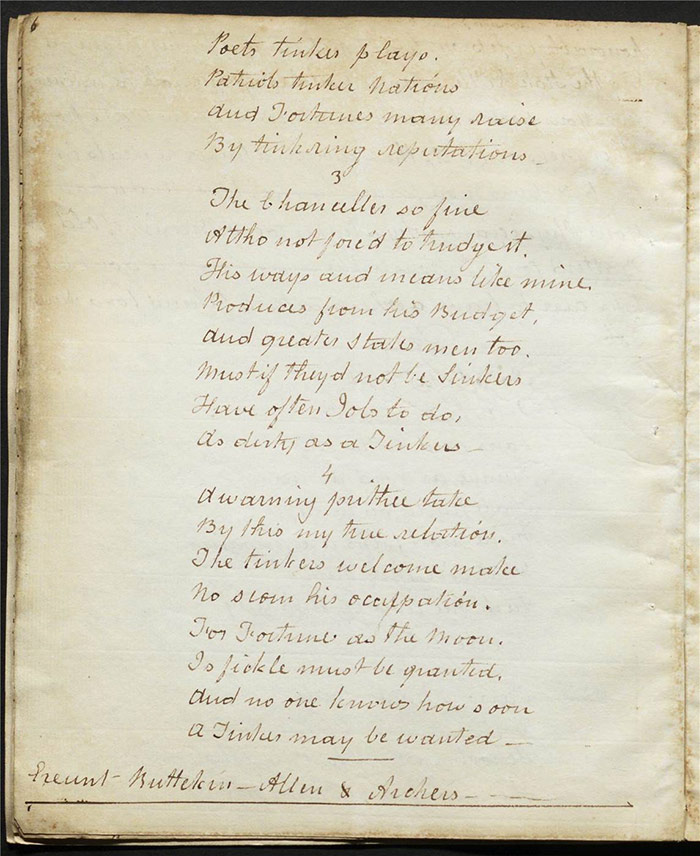

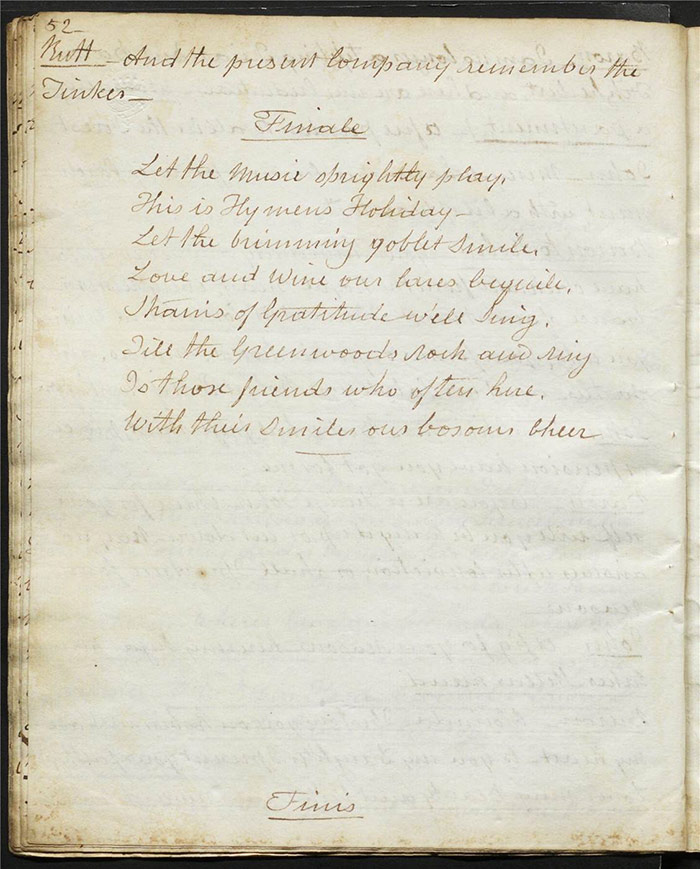

Little John arrives to the outlaw village in Sherwood Forest. He explains to his fellow outlaws that they are going to rescue the Lady Clorinda. Baron Fitzherbert, her uncle, has locked her up and away from the brave Earl of Huntingdon, now Robin Hood, because he was maligned by the pernicious Bishop of Hereford. As a result, the King has banished him from the court and he has become a renegade. Little John stresses secrecy as he wishes to surprise Robin. Will Scarlett and Archers enter with a prisoner, Rutterkin the Tinker. He is deemed harmless before Robin’s horn sounds, summoning John. Rutterkin sings a song and they all exit.

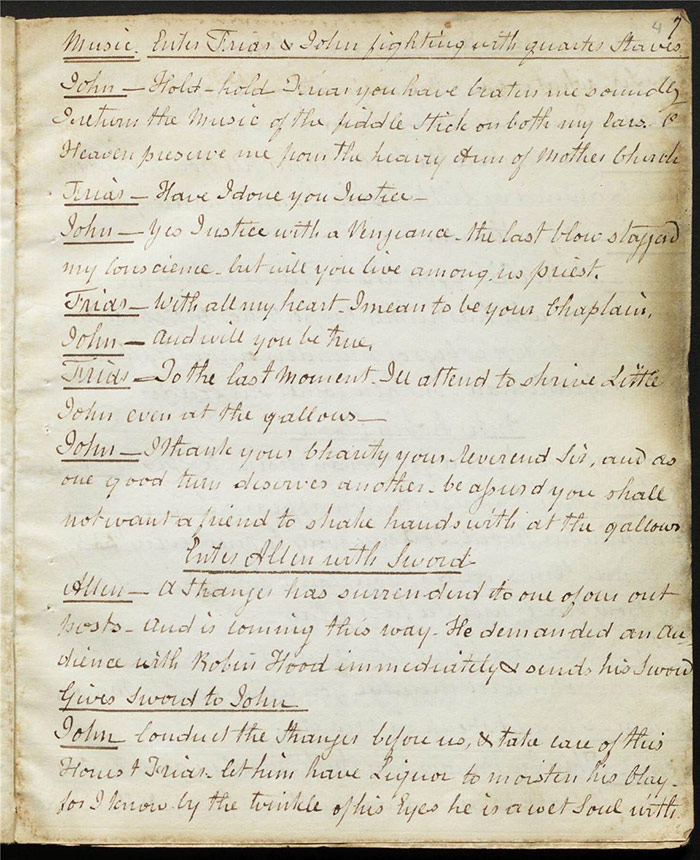

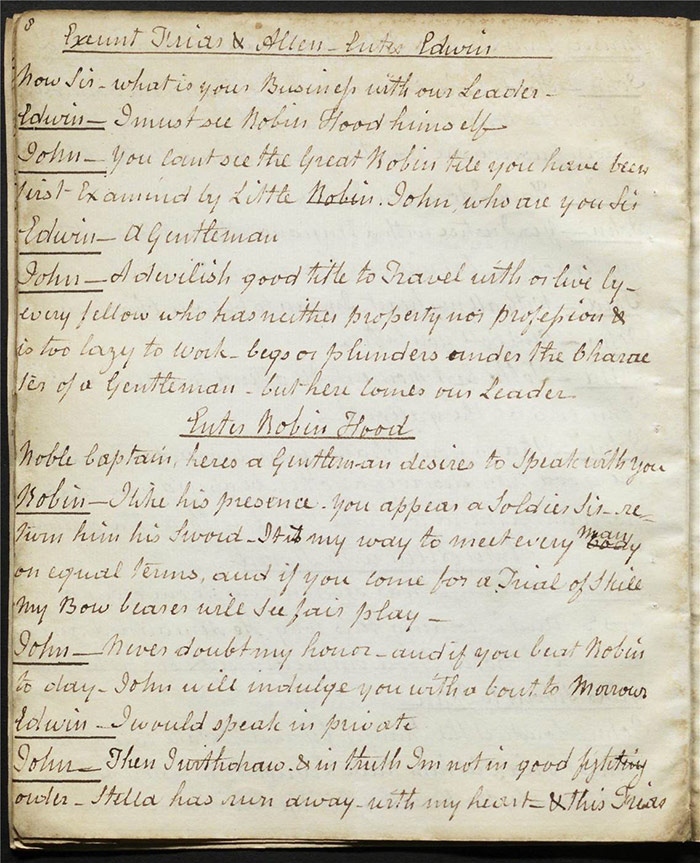

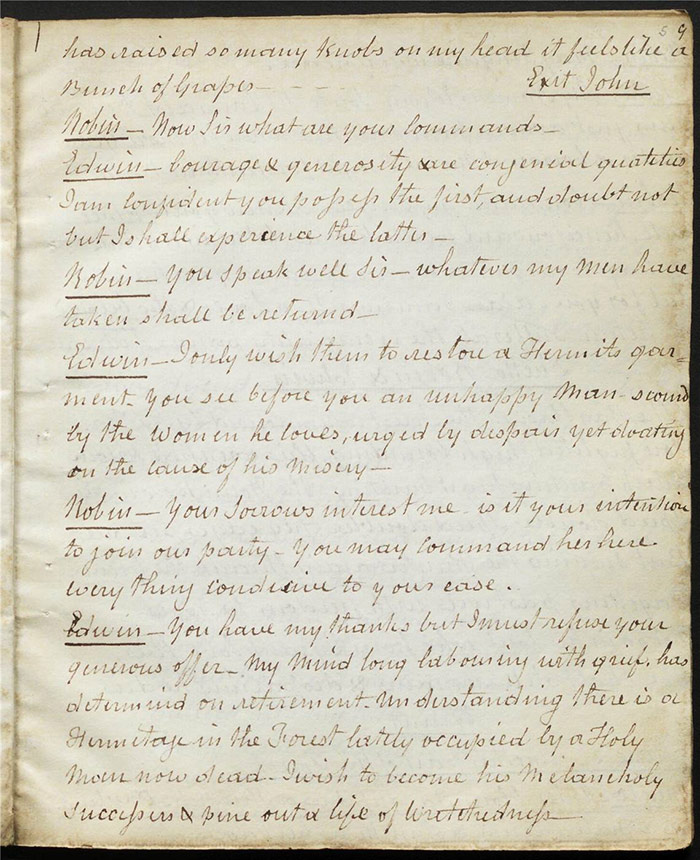

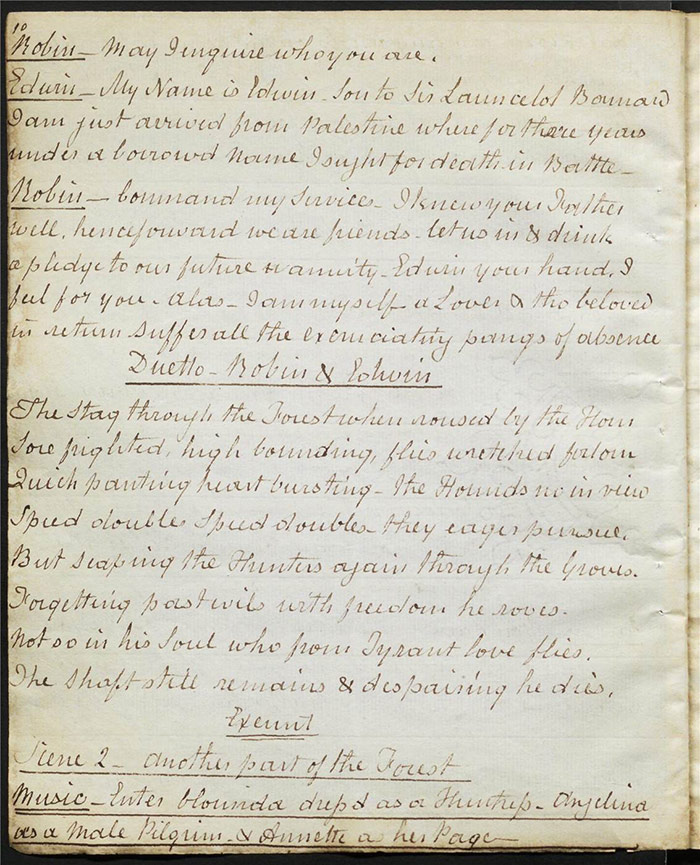

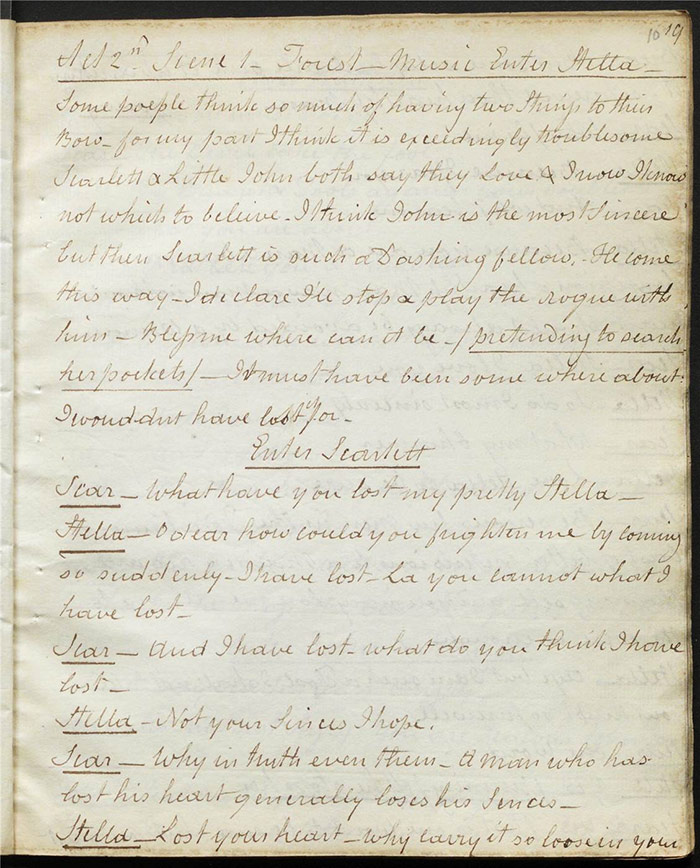

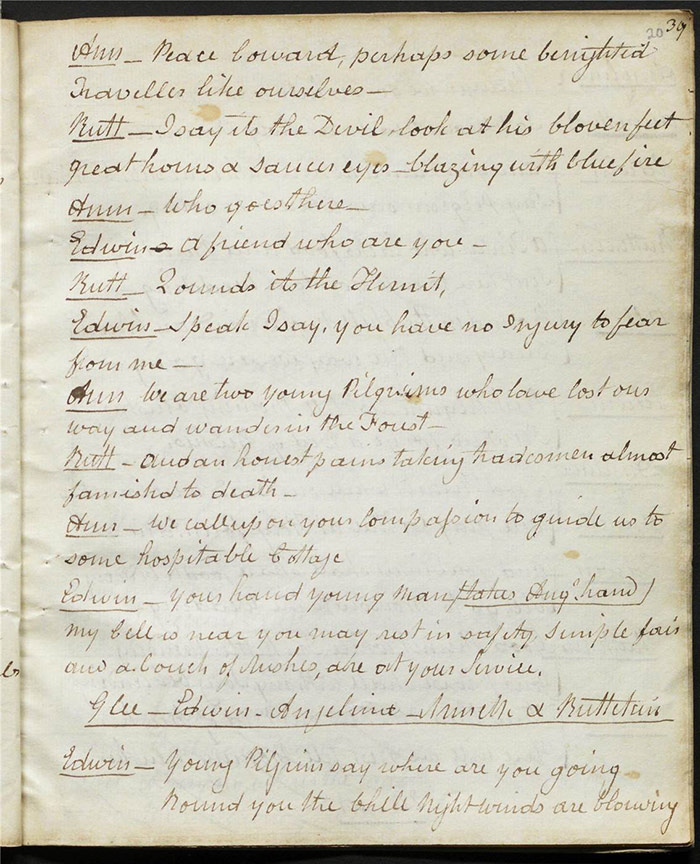

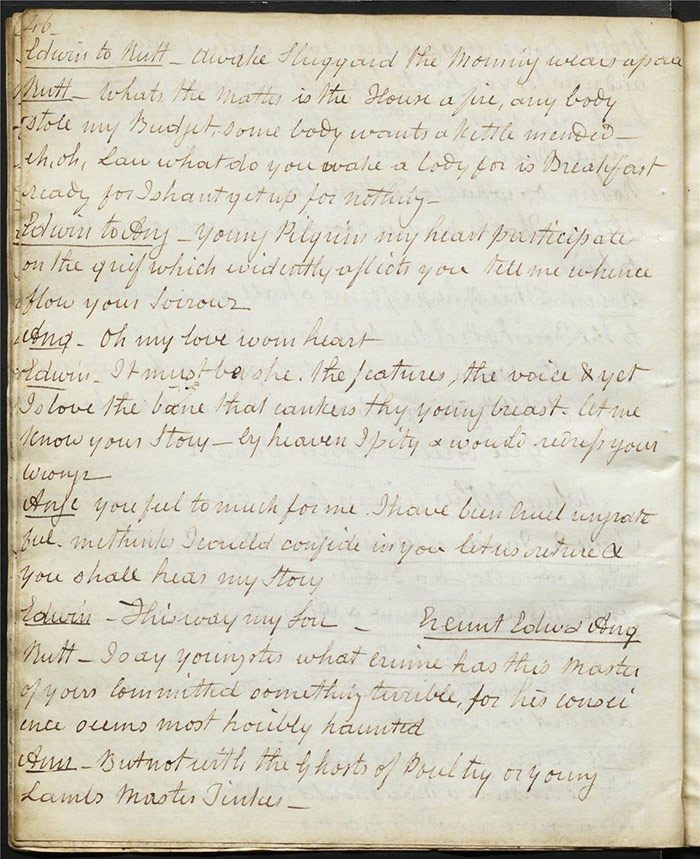

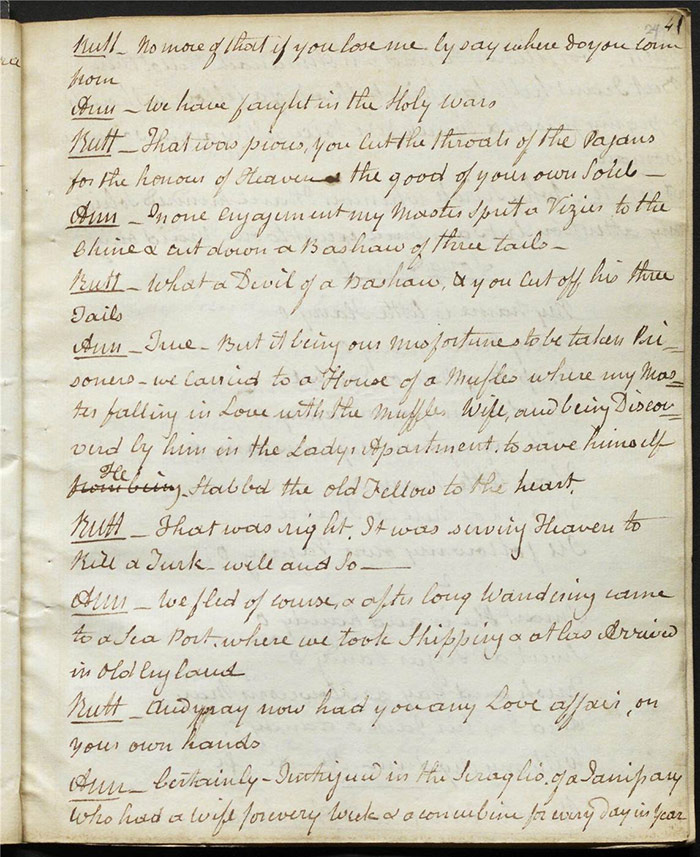

Enter John and Friar Tuck, fighting with staffs. Tuck is recruited to the outlaw band. Allen tells them that a stranger has surrendered and wished to speak to Robin. The stranger introduces himself as Edwin to Robin and begs permission to take up a dead hermit’s residence in the forest. He is a nobleman, just returned from the crusades, where he sought death in the wake of a lover’s rejection. They sing a duet.

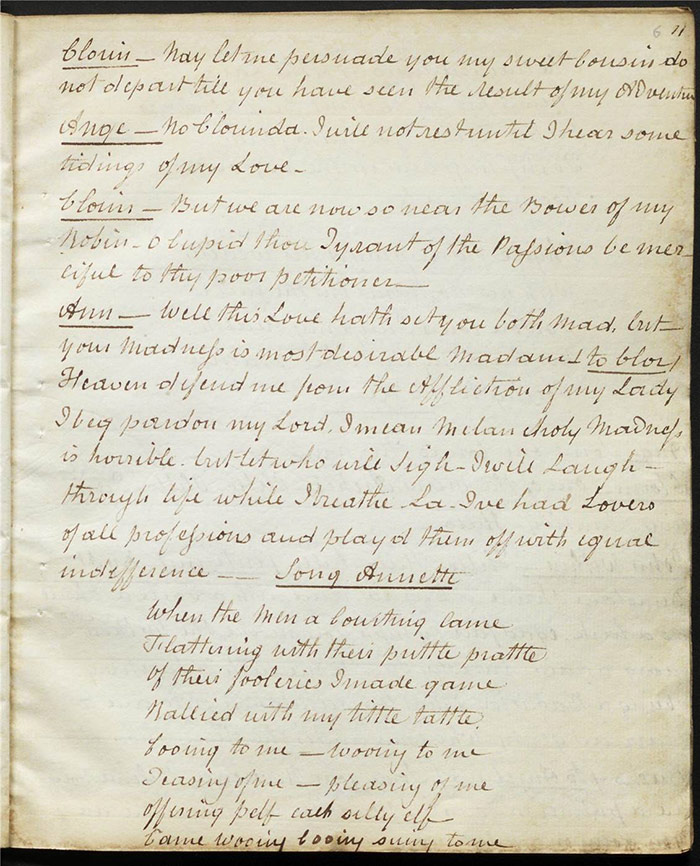

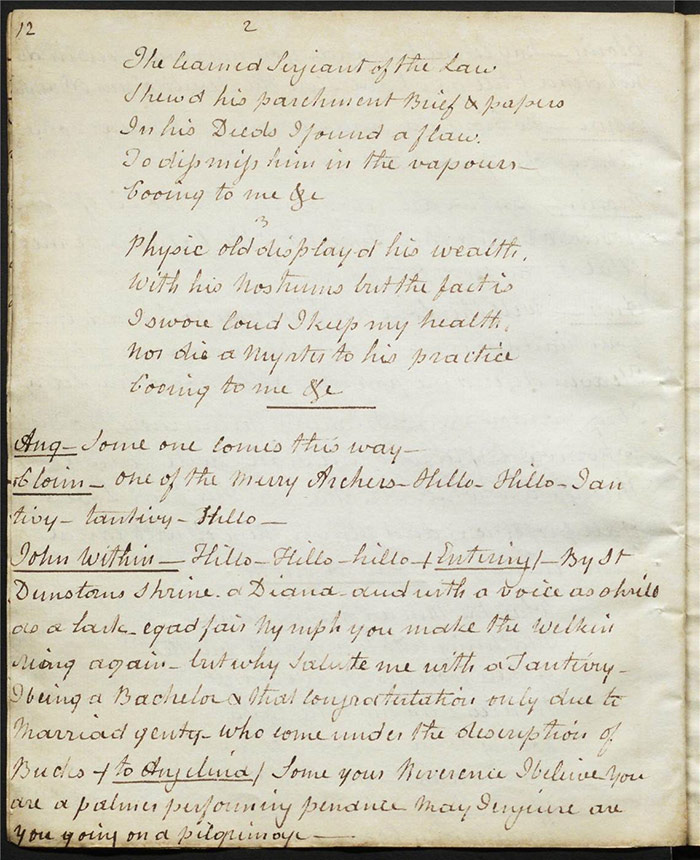

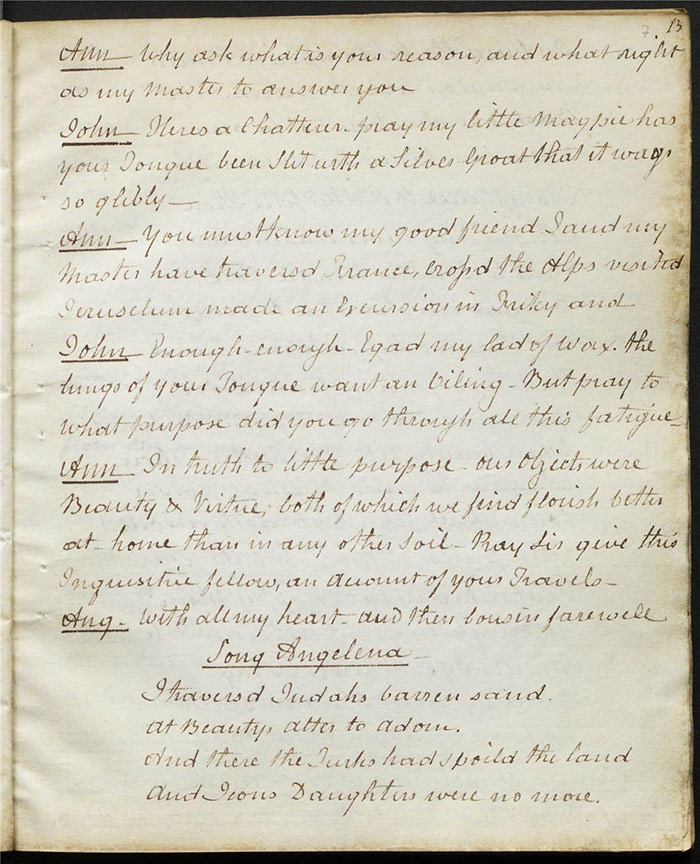

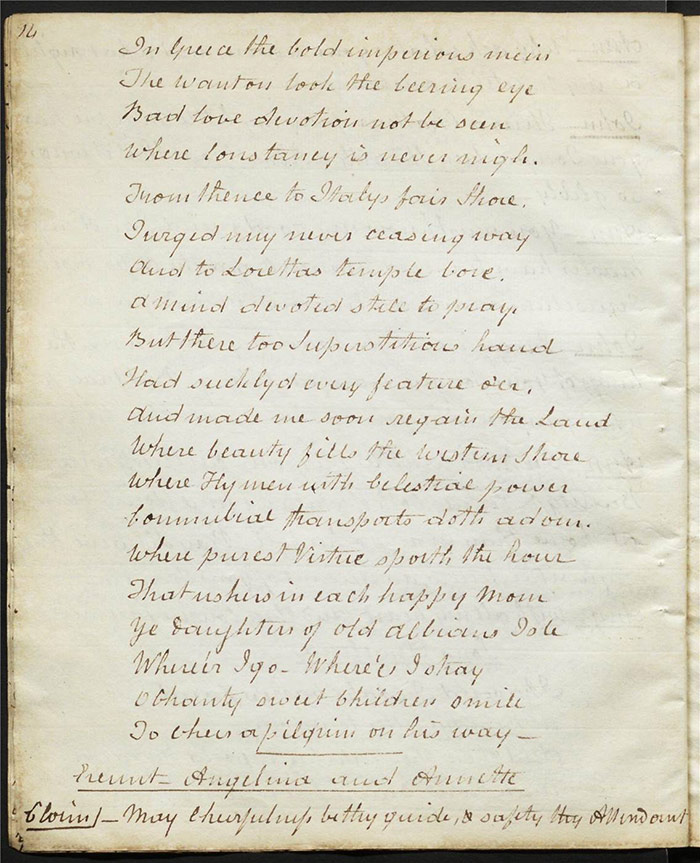

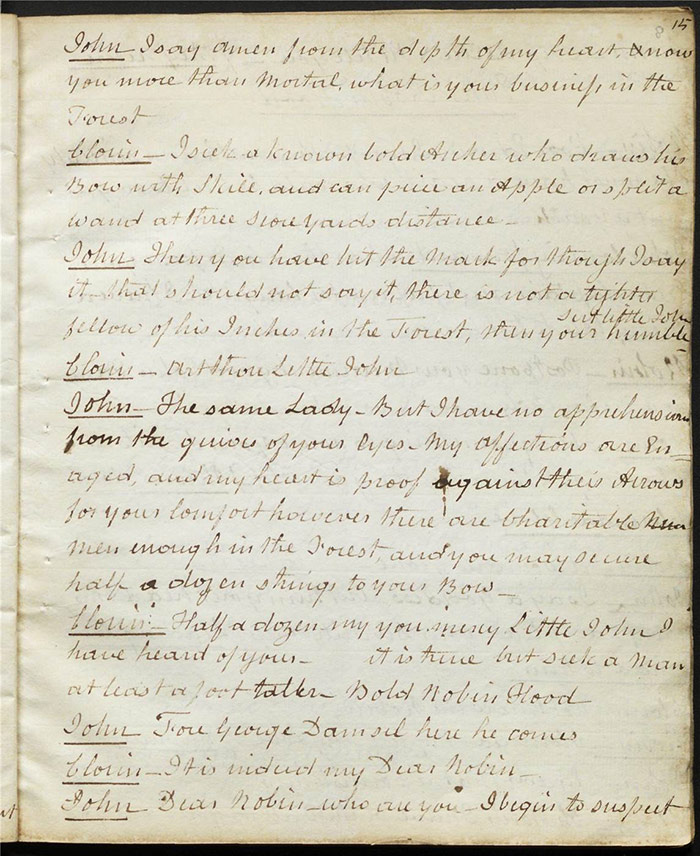

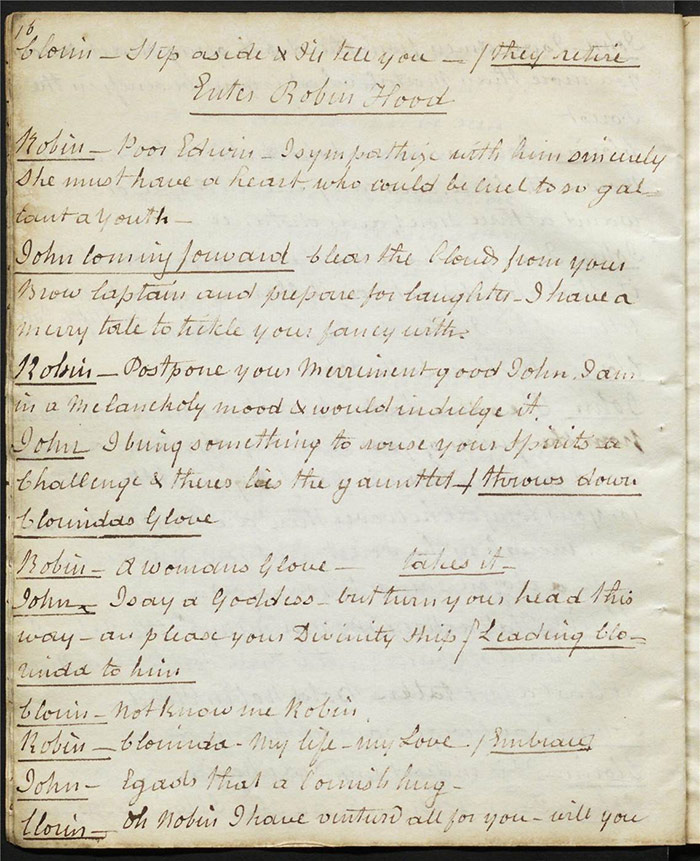

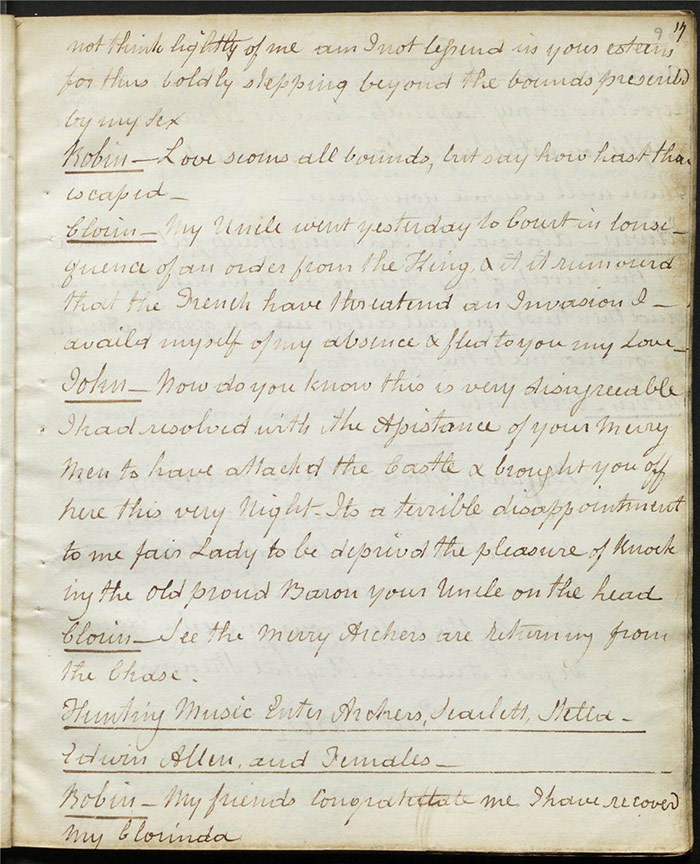

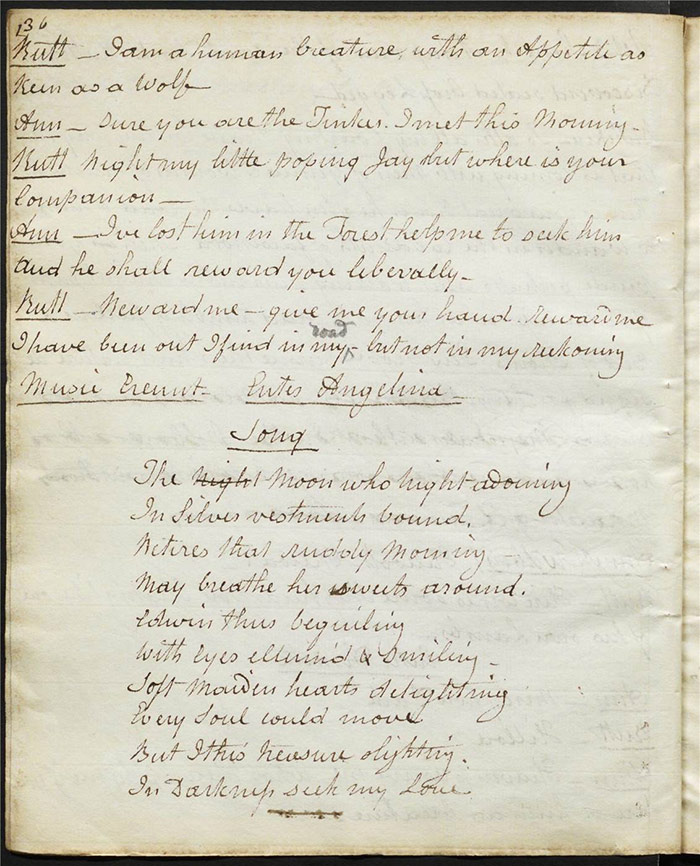

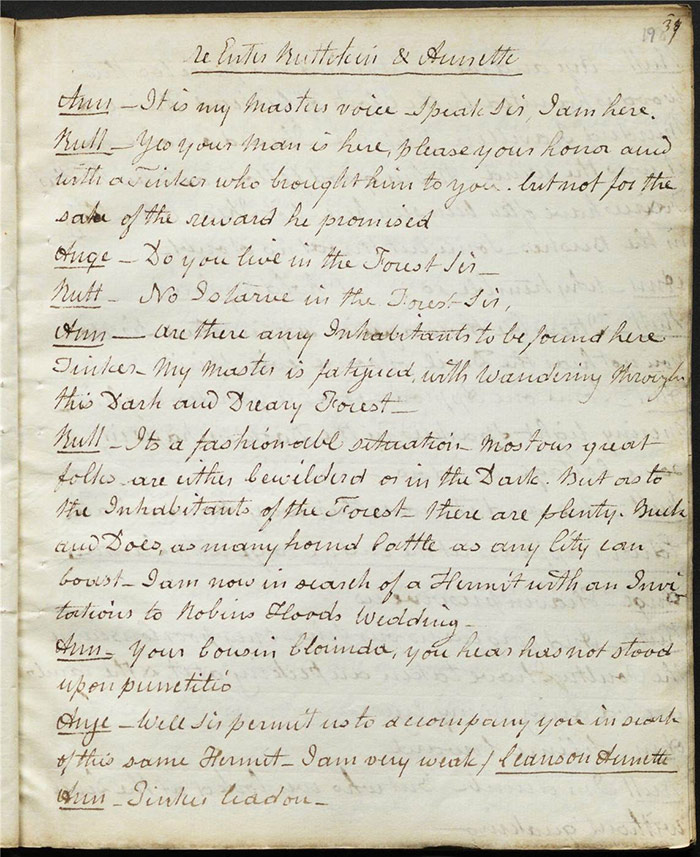

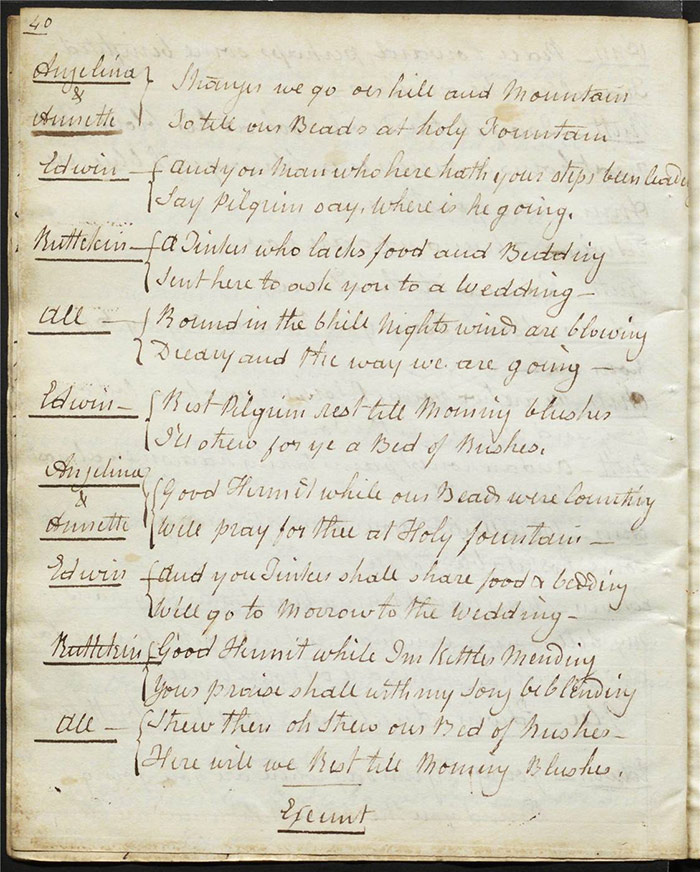

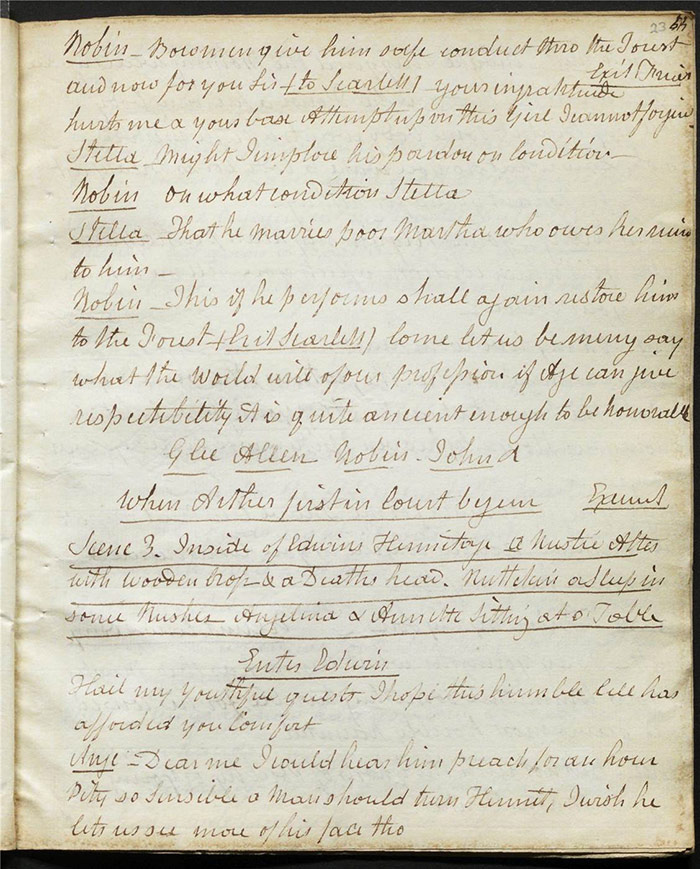

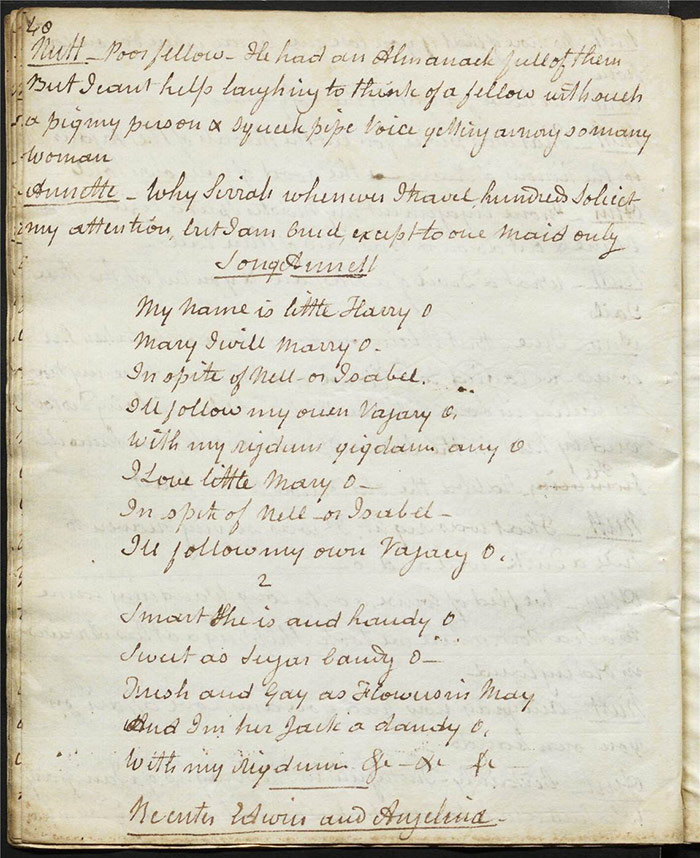

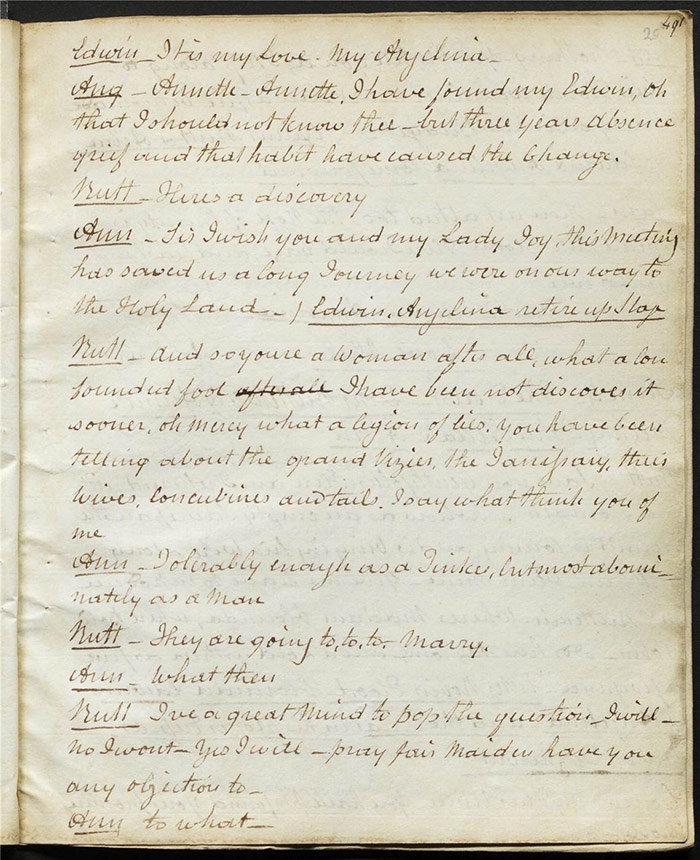

In another part of the forest, Clorinda is disguised as a huntress, accompanied by her cousin Angelina dressed as a male pilgrim, and Annette as a page (f.5v). Annette’s song attracts John. Annette tells him they have travelled through Europe and the Holy Land; Angelina follows with a song and they exit. Clorinda tells John she is looking for Robin and John begins to suspect who she is. Robin enters and the lovers are reunited. The band celebrate except for melancholy Edwin who just asks for an escort to the hermitage.

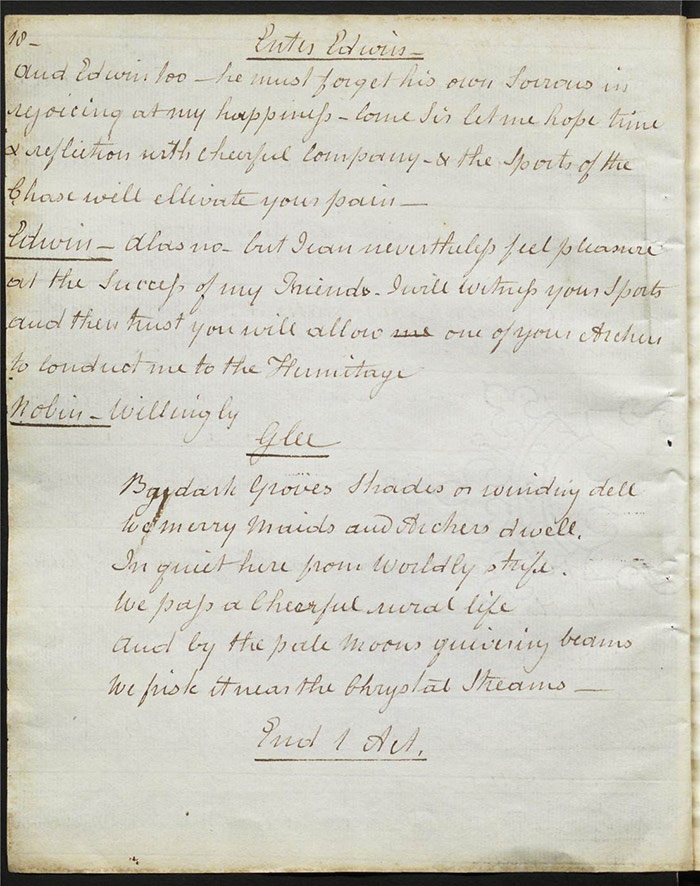

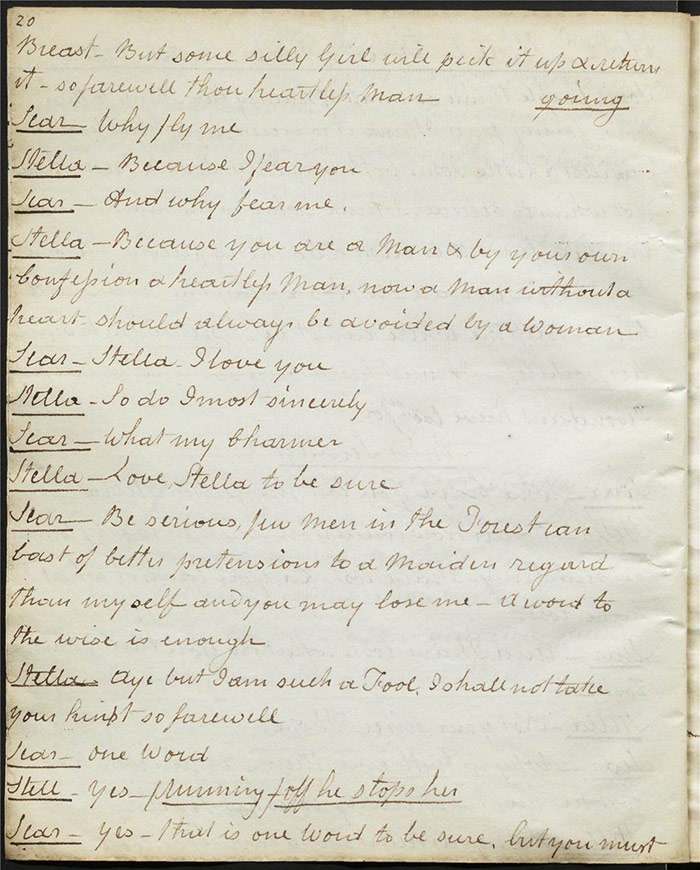

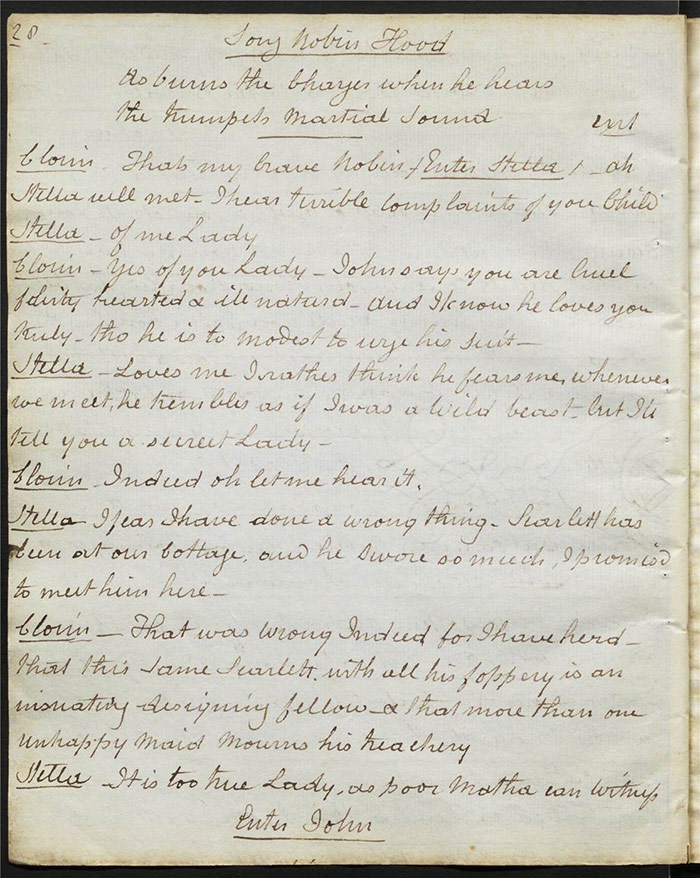

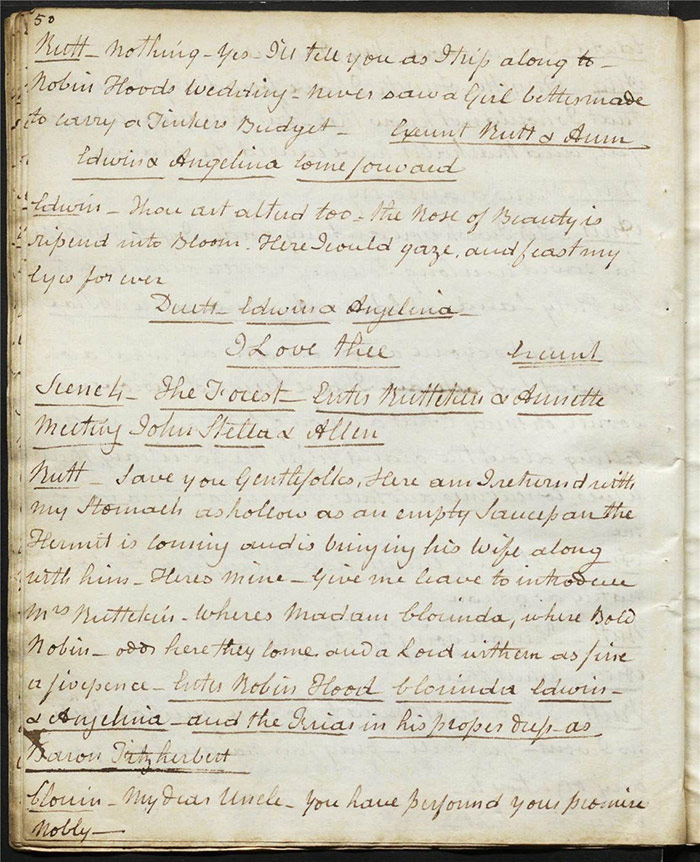

At the opening of act 2, Stella enters debating the various merits of John and Scarlett, both of whom have declared for her (f.10r). Scarlett enters and she toys with him a little before Rutterkin arrives with John. Rutterkin adjudicates their love for Stella and the rivals agree to court her openly.

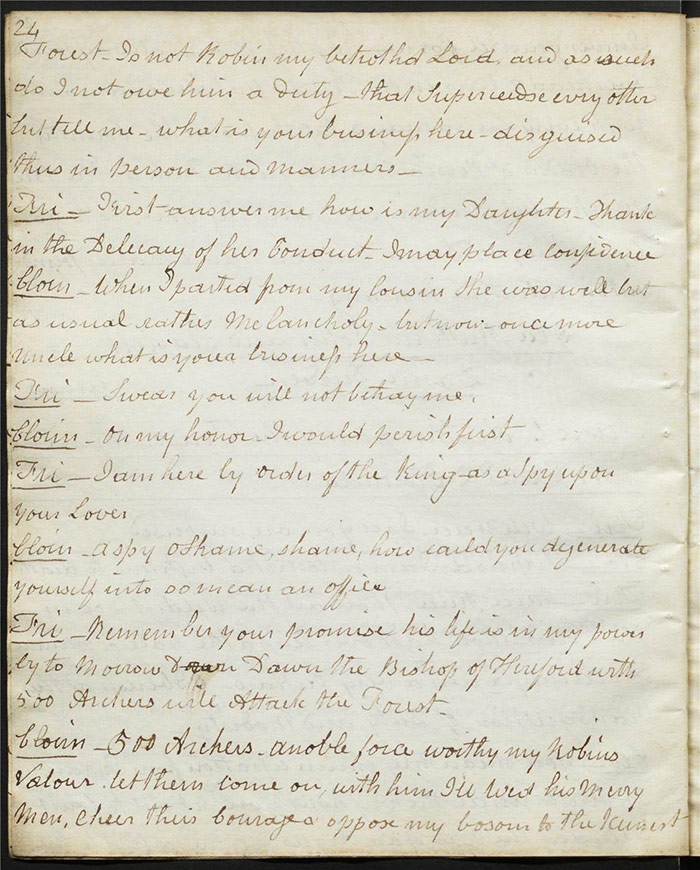

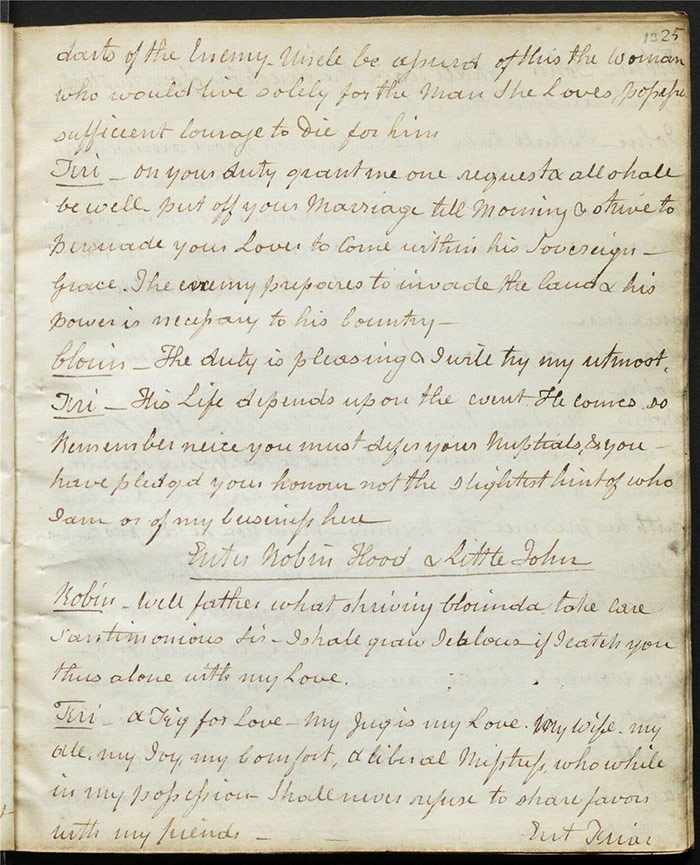

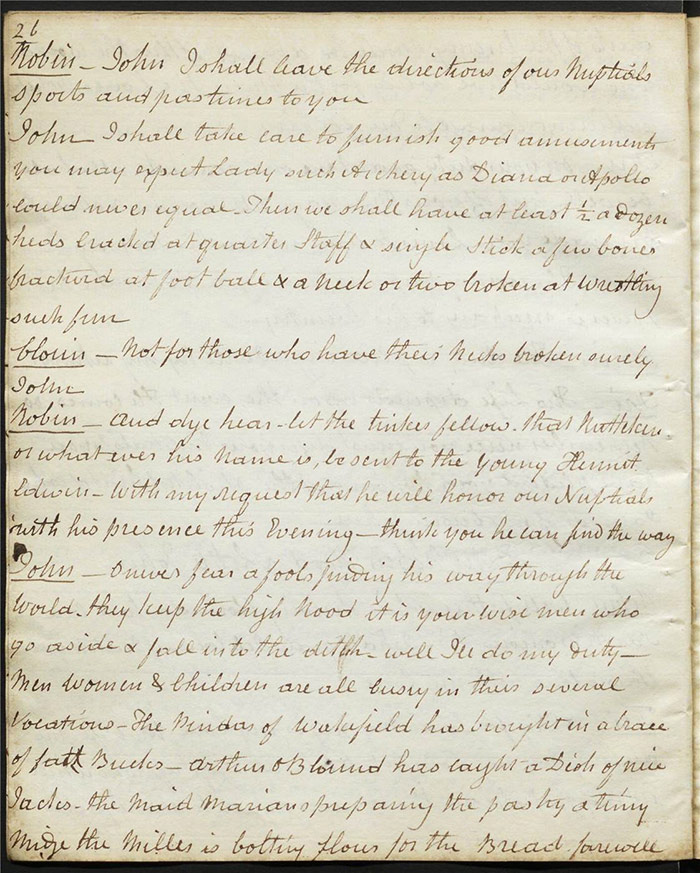

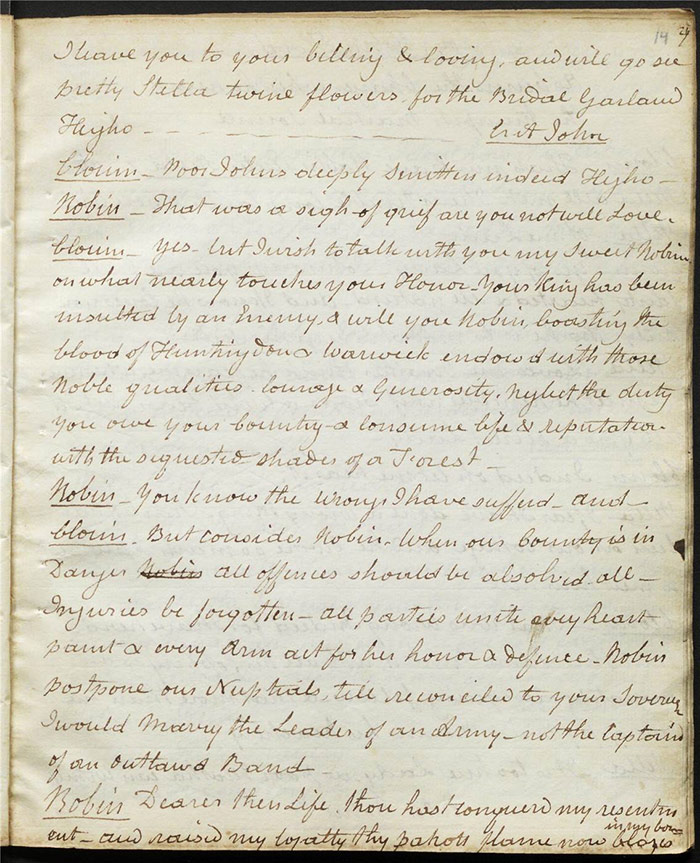

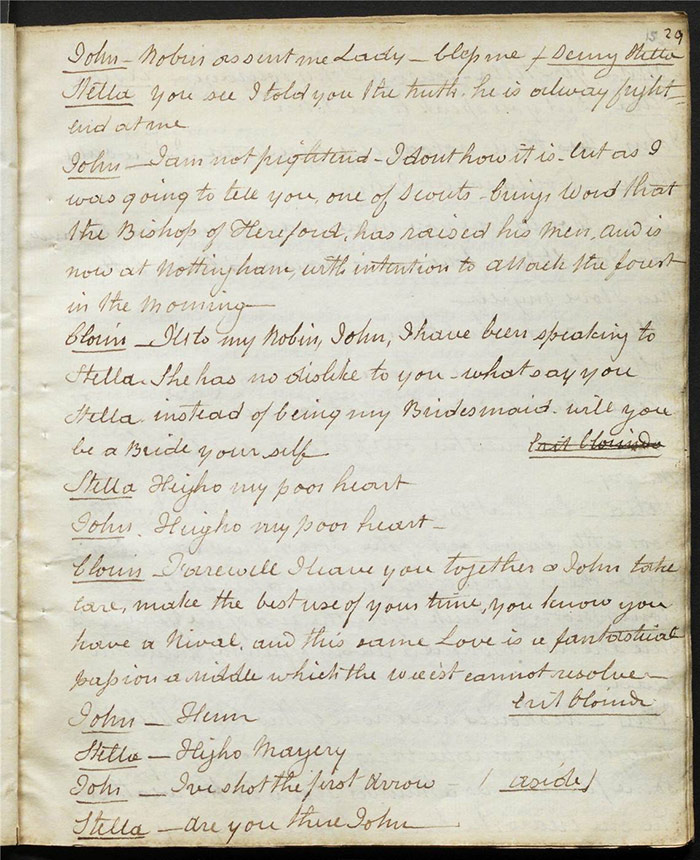

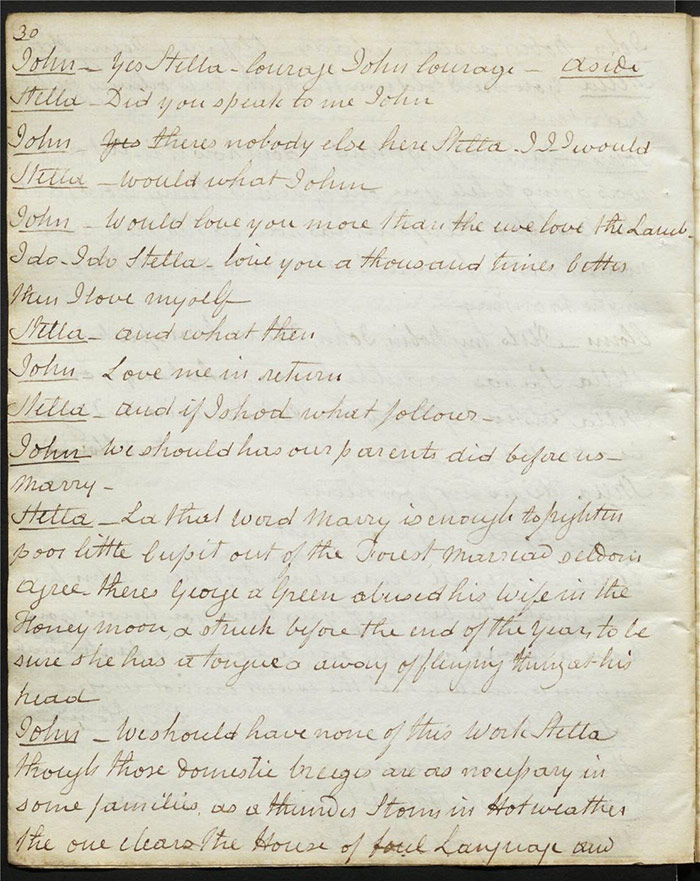

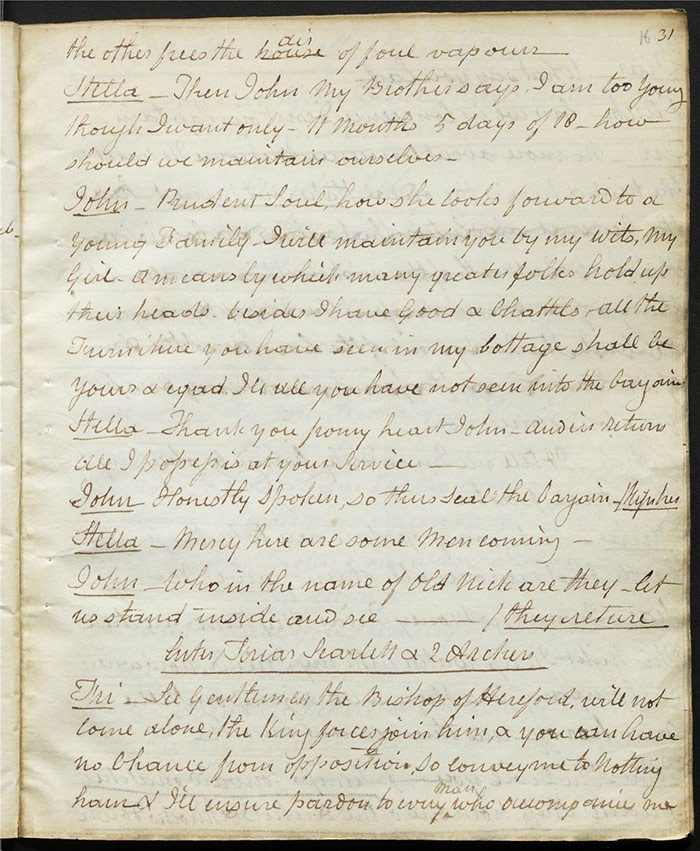

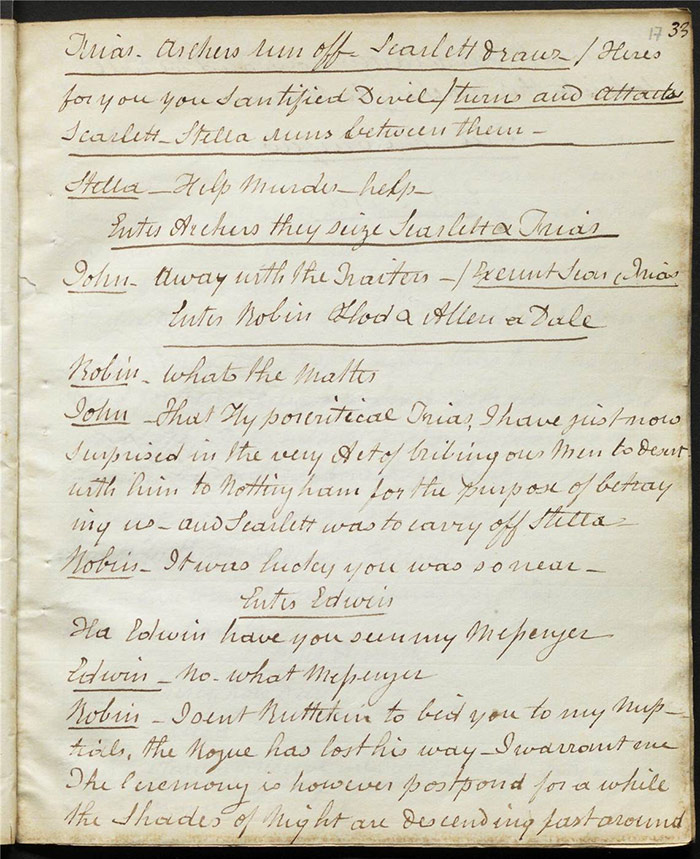

Tuck and Clorinda enter and we learn that Tuck is Baron Fitzherbert in disguise (Clorinda’s uncle and Angelina’s father) (f.12r). He reveals to Clorinda that he is there to spy on Robin and that the Bishop of Hereford is bringing 500 archers to the forest in the morning. He swears her to secrecy and asks her to postpone her wedding until the next day and to encourage Robin to come under the king’s command. She agrees and Robin and John enter, making plans for the wedding celebrations. Clorinda convinces Robin to be reconciled with the king before they marry. She then warns Stella about Scarlett’s foppery and advises her to stick with John. John and Stella then declare their love for each other. Tuck, Scarlett and Archers enter, planning to defend the forest from Hereford’s forces. But John bursts in with Archers and grab Tuck and Scarlaett, believing them to be plotting to betray Robin to Hereford.

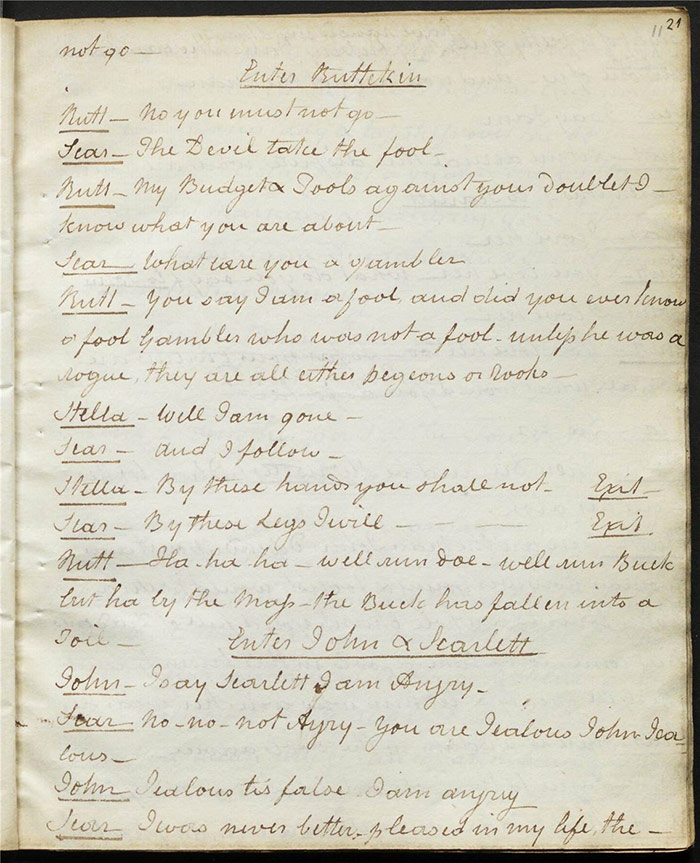

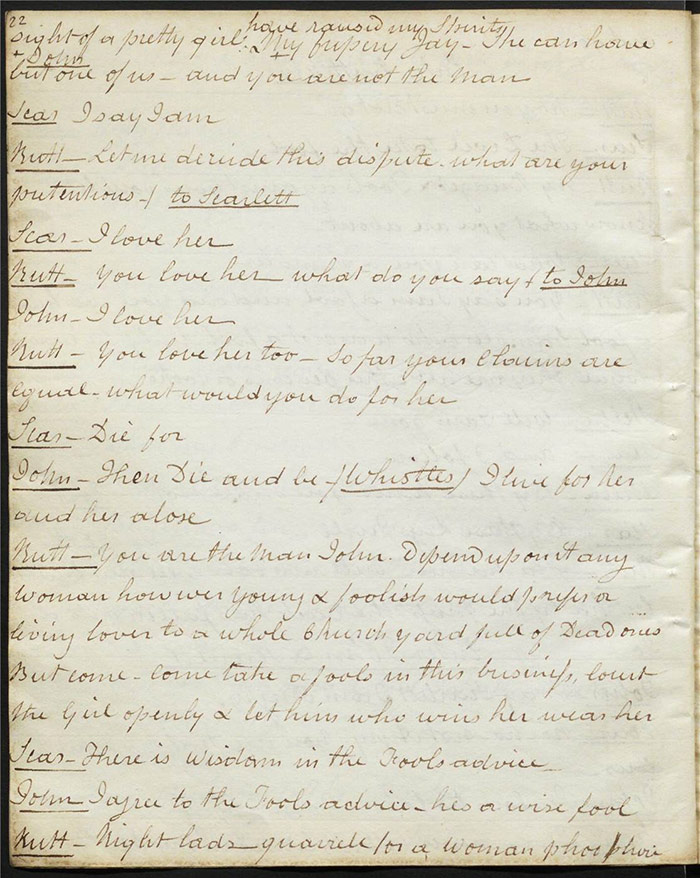

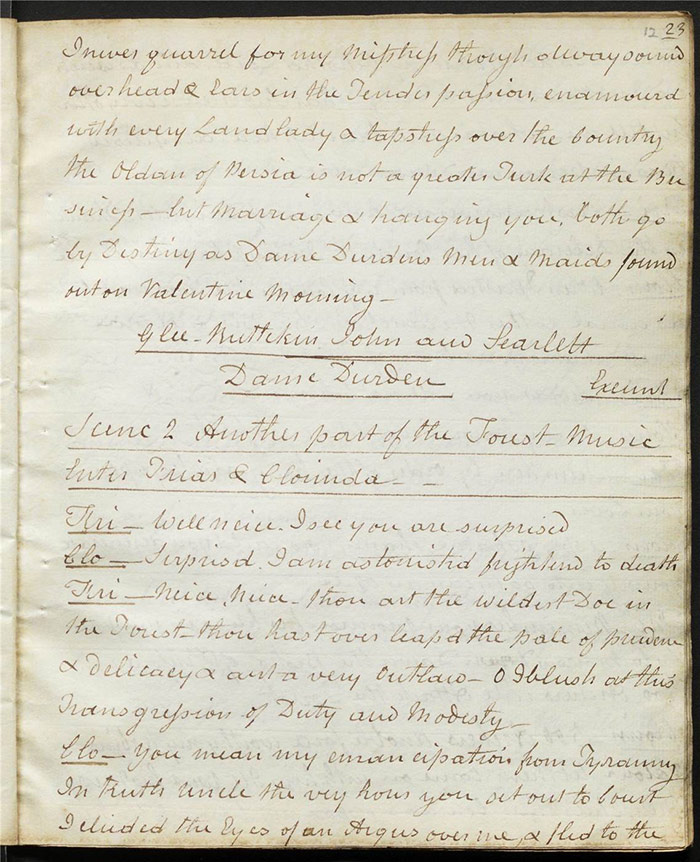

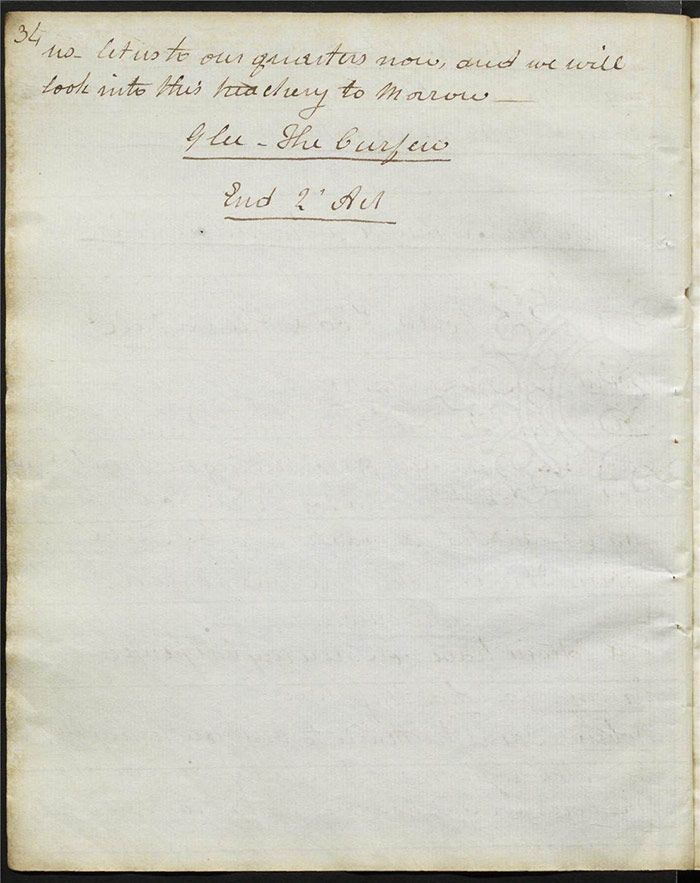

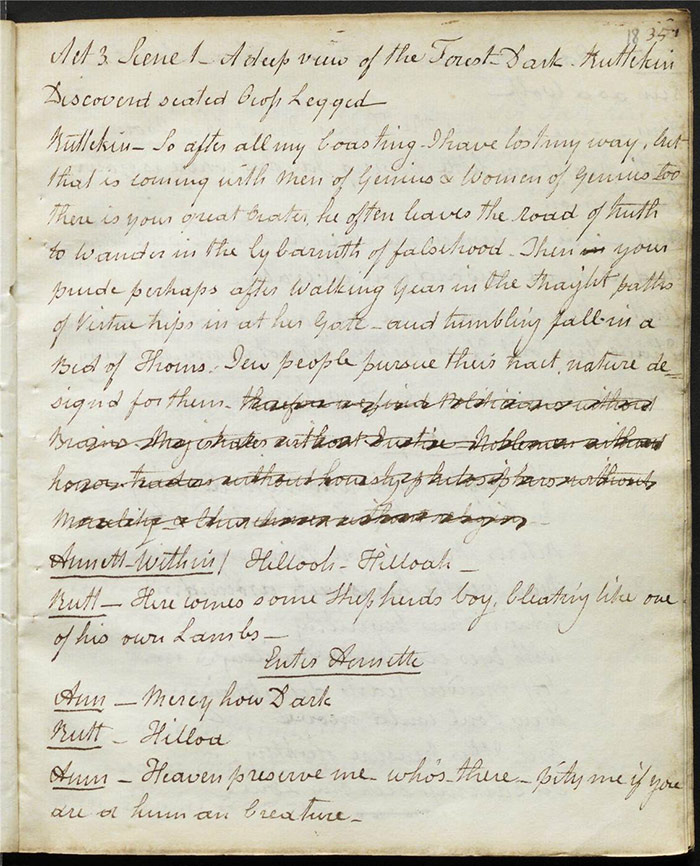

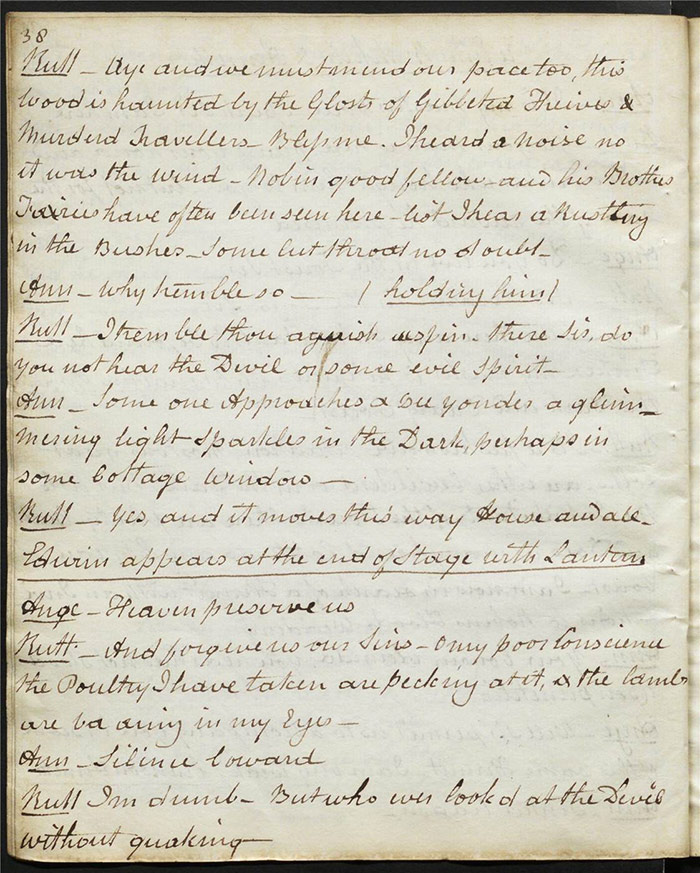

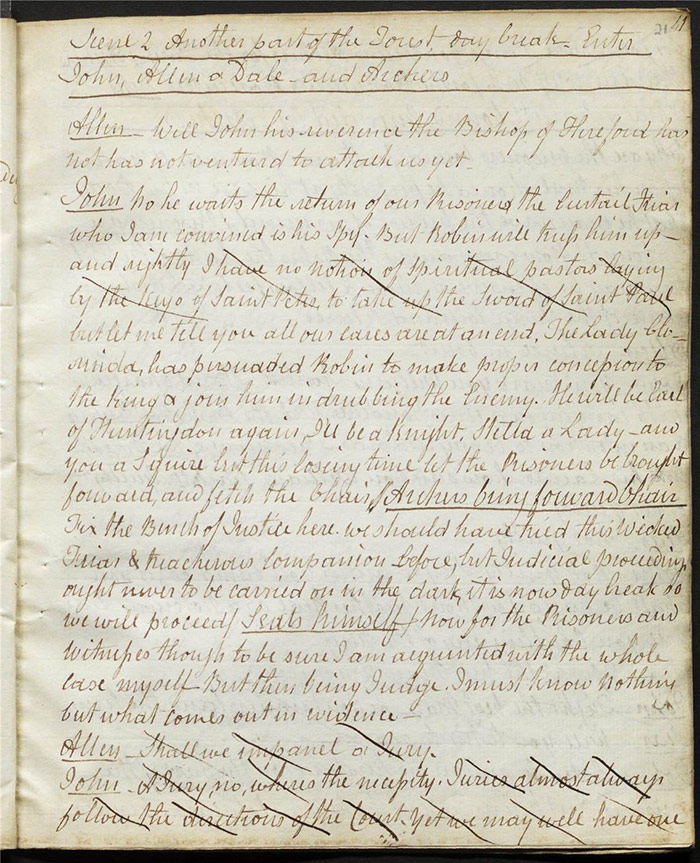

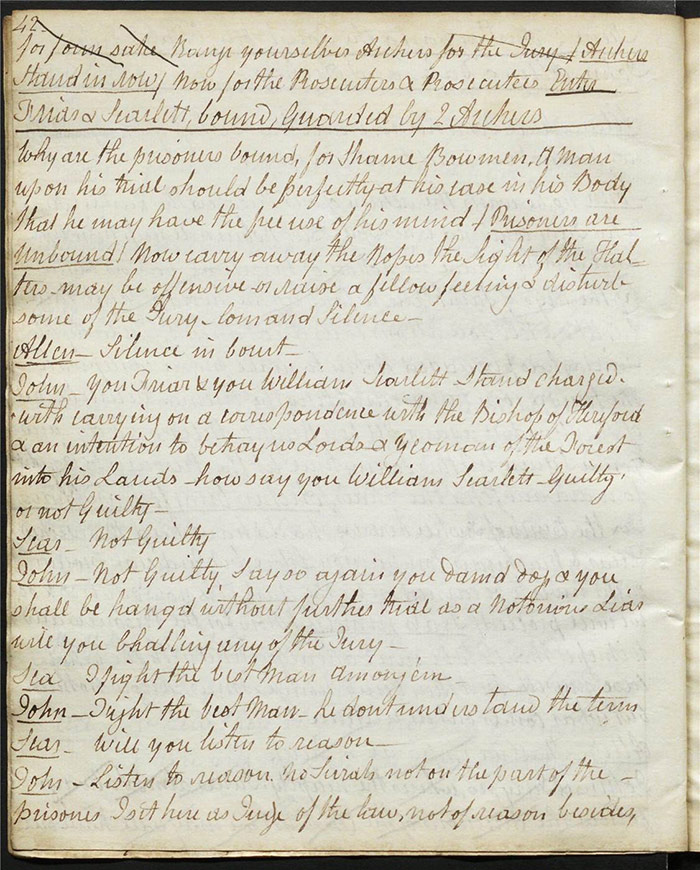

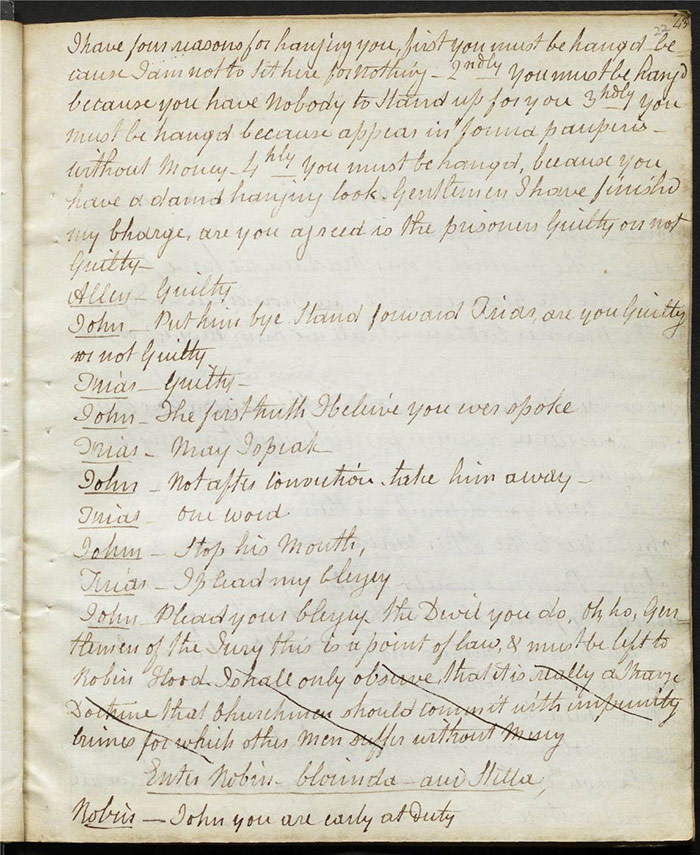

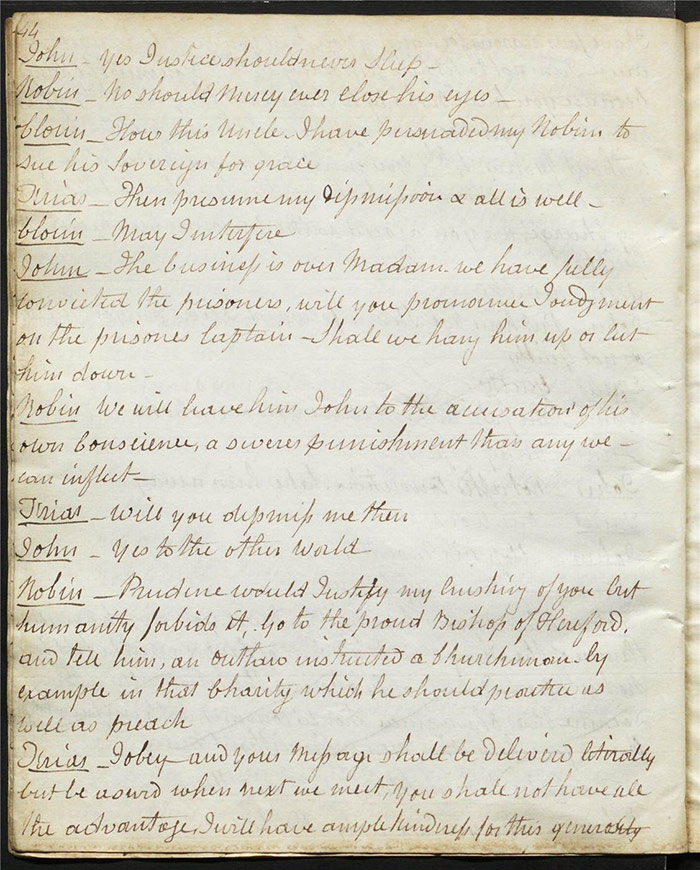

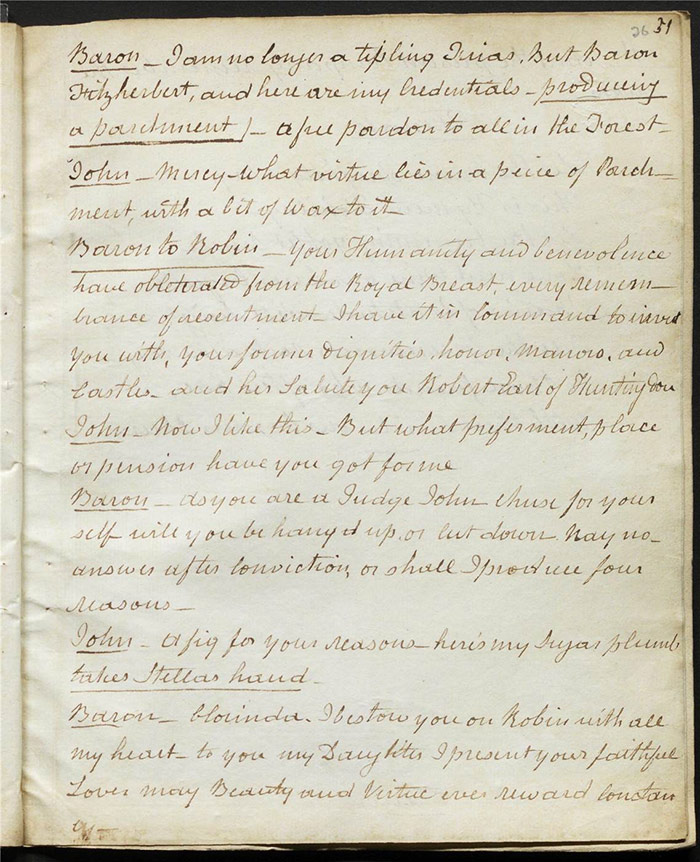

Rutterkin, Angelina and Annette meet in the forest all looking for Edwin in act 3 (f.18r). They find him and sing a song. John conducts the trial of Tuck and Scarlett and convicts them (f.21r). Robin commutes the death sentence and instructs Tuck to return to Hereford in an act of mercy. As for Scarlett, Stella intercedes and asks that if he marry Martha (who owes him her ‘ruin’) that he be pardoned. Robin agrees. Edwin hosts Angelina, Annette, and Rutterkin in his hermitage (f.23r). Despite the disguises, Edwin and Angelina discover each other and are reunited as lovers. Rutterkin fumbles his wooing of Annette. All are gathered together in the forest (f.25v). Fitzherbert enters, no longer disguised as Tuck, and produces a pardon for the outlaws. Robin is restored to his title of Earl of Huntingdon. Fitzherbert bestows Clorinda on Robin.

Performance, publication, and reception

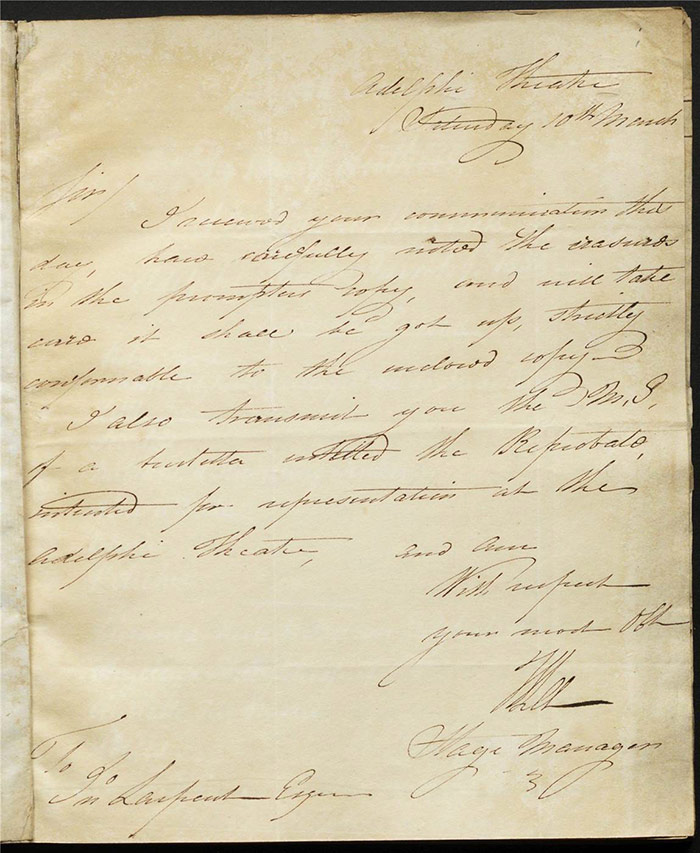

The manuscript was submitted in early March and was dated 7 March by Larpent. Anna Larpent writes in her diary for 8 March ‘Reading Farce for licencing bad enough in morals & taste’. We can be almost certain that this refers to Sherwood Forest, given the date and the licensing issues it had. We can also note that her diary relates that John Larpent was very ill at this time and was bled on 6 March when he had a ‘very bad appearance’ (f. 174r) so we may speculate that she had considerable responsibility for this licensing decision. The Larpent manuscript also includes a letter from William Lee, the Adelphi stage manager to Larpent on 10 March 1821:

I received your communication this day, have carefully noted the erasures in the prompters copy, and will take care it shall be got up, strictly conformable to the enclosed copy.

The burletta was staged for the first time on 12 March 1821 and had its sixth performance on 17 March. It does not seem to have warranted any reviews in the newspapers. Planché drew very heavily on Leonard MacNally’s Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest (LA 654; 1784). Both MacNally and Planché include the story of ‘Edwin and Angelina’ in their plots, which is taken from Goldsmith’s poem of the same name and which features in The Vicar of Wakefield. Planché’s version does not appear to have been published. He remained interested in the Robin Hood legend and he later published A Ramble with Robin Hood (1864) which suggested that Robin Hood was Robin Fitz Odo, descended from William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Odo.

Commentary

The manuscript contains a number of excised passages. There may be two pens at work as some passages are obliterated with the text struck through while there are others which are marked for deletion by a number of diagonal lines crossed through the passages. The offending speeches pertain chiefly to observations on the integrity of various branches of British institutional society. One passage is censored for religious references (to St Peter and St Paul). The general imputation of the charges made is that the outlaw life is morally superior to many supposedly upstanding facets of British society.

The censorship interest is how this figurehead for ideas of liberty and self-determintion is used to critique society. The antiquarian and reformer Joseph Ritson’s Robin Hood: a collection of all the ancient poems, songs, and ballads now extant related to that celebrated English outlaw (2 vols., 1795) had done much to firm up that association in the heady environment of the 1790s, here Planché speaks to that tradition in the 1820s.

The passages marked for removal are listed here; the rationale for their censorship is self-evident and consistent with Larpent’s mandate to safeguard British institutions:

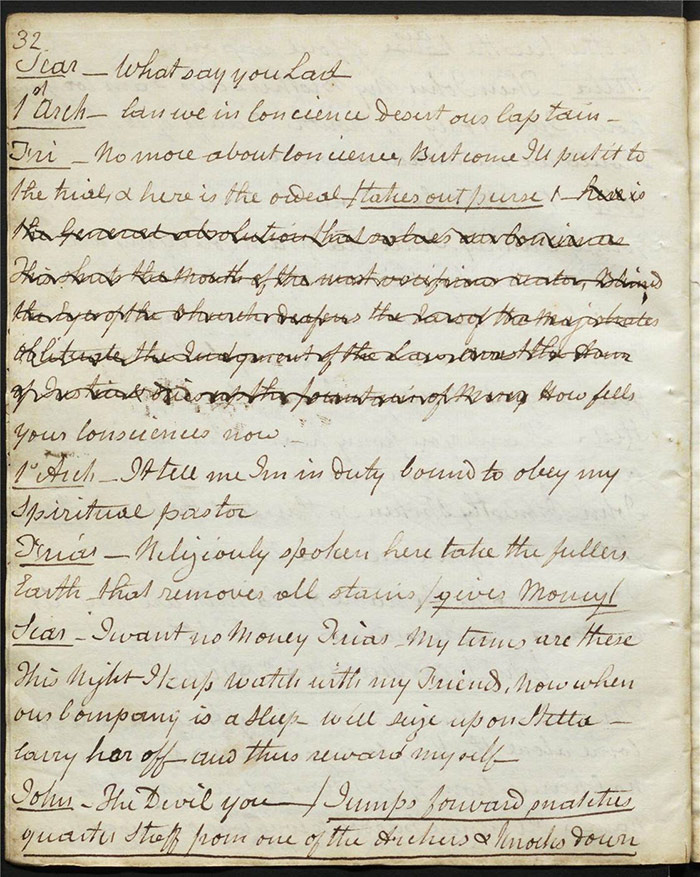

Friar: No more about conscience. But come, I’ll put it to the trial & here is the ordeal [takes out purse] – here is the General absolution that salves our Conscience. This shuts the mouth of the most vociferous orator, Blinds the Eyes of the church, deafens the Ears of the Magistrates obliterates the Judgment of the Law [arrest] the [illeg] of Justice & stop the fountain of Mercy. How feels your conscience now. (f.16v)

Rutterkin: […] Few people pursue this trait nature designed for them. therefore we find Politicians without brains - Magistrates without justice – Noblemen without honour – traders without honesty - philosophers without morality & Churchmen without religion. (f.18r)

John’ [..] I have no notion of spiritual pastors laying by the keys of Saint Peter to take up the Sword of Saint Paul.

[….]

Allen: Shall we impanel a Jury.

John: A Jury, no, where’s the necessity. Juries almost always follow the directions of the Court. Yet we may well have one for form sake. (f.21r)

John: […] I shall only observe that it is really a strange doctrine that Churchmen should commit with impunity crimes for which other men suffer without mercy.

(f.22r)

There may be interest in comparing this drama with George Soane’s The Pilgrim from Palestine (DL, 1820; LA 2143; published as The Hebrew). This also features Robin Hood and contains a number of excisions, mostly to do with religious language.

Further reading

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library, vol. 11, March 1821.

Leonard MacNally, Robin Hood; or, Sherwood Forest (London: Printed by J. Almon, 1784)

[available on HathiTrust.org]

Donald Roy, ‘Planché, James Robinson (1796-1880)’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22351, accessed 3 February 2019]

George Soane, The Hebrew (London: Printed for John Lowndes, 1820)

[available on Googlebooks]