The Hustings (1818) LA 2031

Author

Anonymous

Plot

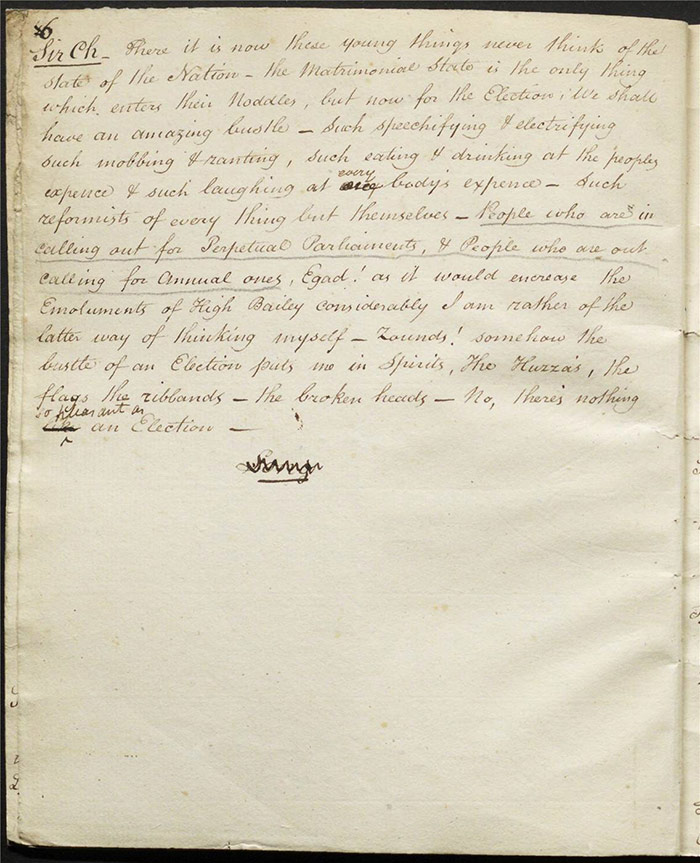

Sir Christopher Castrote, the High Bailiff of the Borough of Swallowell, is reading newspapers in his apartment [the borough is identified as Swallowell in the dramatis personae but in the text of the play, it is called Flimsymote]. There is news of an election and he calls his servant, Thomas Trusty, to get his wig and coat ready for his public duties. A crier outside announces that there are two seats to be filled and candidates need to send their documentation to the bailiff. After he addresses the crowd sternly as to their election behaviour, his niece Lucy enters. Sir Christopher tells her he has decided she shall marry one of the successful candidates rather than Mr Canvass whom she has previously promised to marry. She is distressed at the thought of breaking her word but Sir Christopher suggests that Canvass could stand for election and compete for her hand.

A servant announces the Burgesses – a tradesman, landowner, exciseman, and a funds manager – who are all pinning their hopes on the election improving their respective businesses (f.3r). When Sir Christopher asks them for their nominations, they squabble over the respective importance of their financial interests. Finally, Thomas offers himself as an honest and non-partisan candidate. Sir Christopher sends them all off to the hustings.

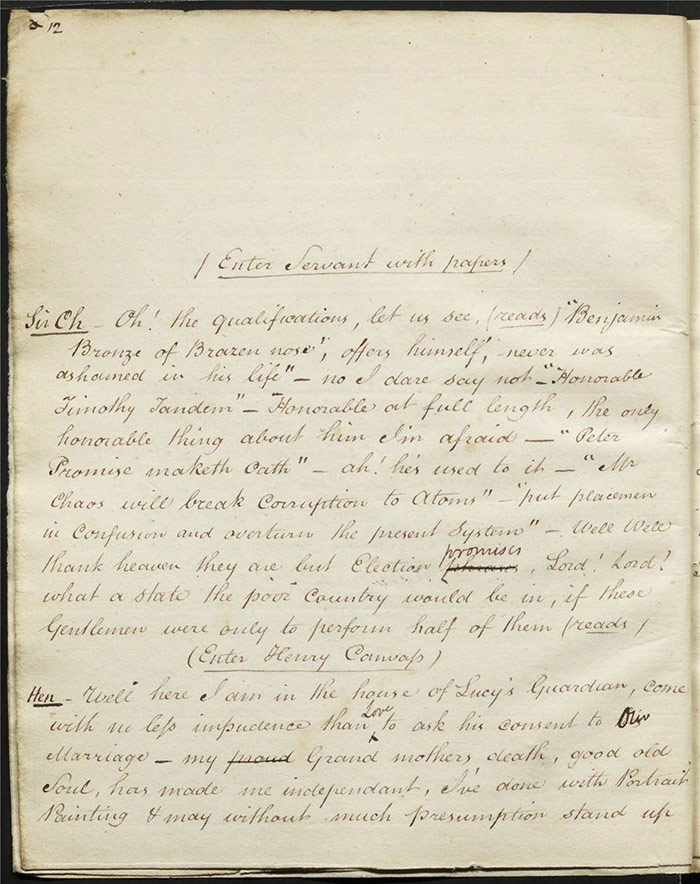

Sir Christopher is reviewing the other candidates – Benjamin Bronze, Timothy Tandem, Peter Promise, and Mr Chaos – when Henry Canvass enters (f.5v). A humorous exchange at cross-purposes ensues whereby Henry understands the Sir Christopher’s election talk as referring to his intended marriage with Lucy. He is bewildered when told she is preparing favours for all candidates; he is thus appalled by Sir Christopher’s and Lucy’s apparent libertinism. Lucy enters and explains the situation to him.

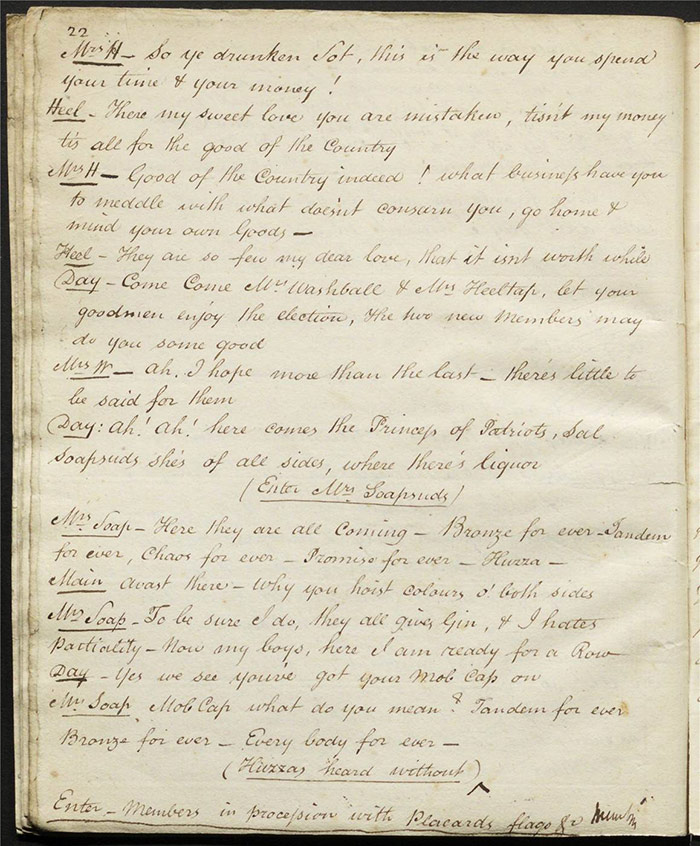

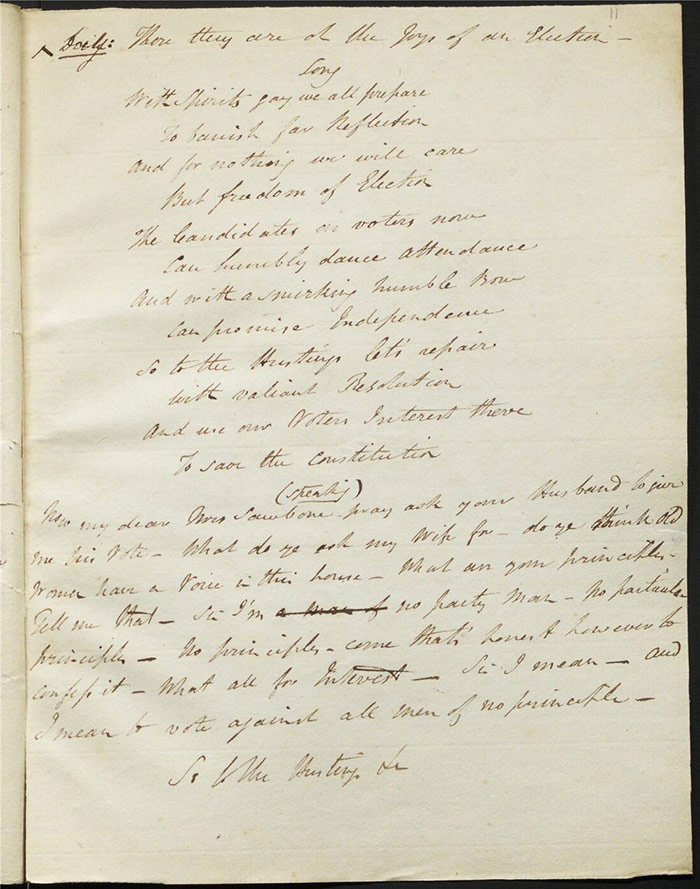

The voters are awaiting the hustings: Washball (a ‘Patriotic Barber’), Heeltap (‘Drunken Cobler’), Daylight (‘ruined Glazier’), and Mainmast (‘provisioned Sailor’), accompanied by the mob (f.9v). Their discussion further outlines how political self-interest holds sway rather than the national interest. They are joined by some of their wives and the dissolute Mrs Soapsuds who supports all parties in exchange for the gin they distribute. The candidates arrive in procession and the scene ends with a song and a raucous cacophony of hollow election pledges from all the candidates.

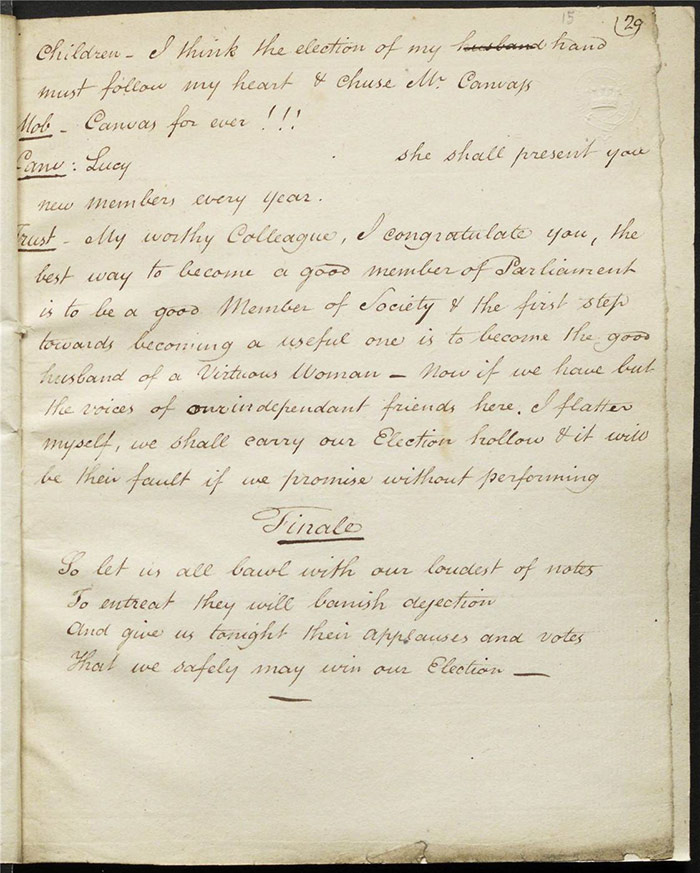

Bronze, Tandem, Promise, and Chaos give their speeches, offering a series of improbable election promises (f.12r). Trusty counters by suggesting that people need to think about personal before political reform. Canvass gives the final speech and, irked and amused by his precedents, makes a number of patently ludicrous promises which the crowd huzza. Sir Christopher declares Trusty and Canvass elected and bailiffs come and take Bronze, Promise, Chaos, and Tandem away.

Performance, publication, and reception

The manuscript was submitted by Samuel Arnold, manager of the Lyceum Theatre. It is endorsed ‘June 24 1818’. The piece – described as an ‘Operatick Impromptu’ in the manuscript – was neither performed nor published. There is no mention of it in Anna Larpent’s diary.

Commentary

This play manuscript was refused a licence. The manuscript is marked with pencil: offending passages are generally underlined in pencil or, occasionally, marked with an ‘X’ in the margin or by a line through the dialogue. These passages refer to political corruption and electoral malpractice. A reference to an actual M.P. is also marked for omission.

The context for this brief theatrical piece is the general election for 1818. Parliament was dissolved on 10 June 1818 and the election lasted from 17 June – 18 July; the final result was known on 4 August. The Tories under the Earl of Liverpool won.

As we have seen in the earlier example of George Colman’s The Election of the Managers (1784), plays which dealt in parliamentary elections could expect to be carefully scrutinized. The Westminster election in 1818 was a rambunctious affair; the newspaper reports of the hustings are colourful. On one of the hustings days, Lord Castlereagh, canvassing for Sir Murray Maxwell, was forced to take shelter in a draper’s shop ‘in consequence of the violent threats of violence offered to his person, by throwing mud and various things at him’. The ‘mob’ of 500 used the ‘most foul language and threats’ meant that the police had to be called to rescue Lord Castlereagh (Morning Chronicle, 22 June 1818). Similarly, the hustings for the City of London reported in the Morning Chronicle (23 June) states that ‘personal safety became doubtful’ at one stage.

The extent of the excisions here is considerable. As L. W. Conolly noted, it is difficult to believe that Arnold ever thought that this play would be licensed. The moral character of members of parliament comes under sustained attack. Dialogue marked for excision includes references to parliament being ‘Be-rogued’ (f.1r), Lucy saying that Canvass is an ‘honest open hearted fellow not at all fit for an M.P. (f.1v), and that ‘they [MPs] change every day’ (f.2r), a nod towards their vacillatory nature. References to dubious electoral practices were also frowned upon: ‘oaths go for nothing at Election time – (aside) except those that are paid for’ (f.1v) and the offer of a ‘plumper for any body’ (f.11v).

References to current political concerns such as annual parliaments (f.2v, f.7r), the liberty of the press, and the Corn Laws (f.11v) were also deemed inappropriate for theatrical discussion. It is worth noting that it was simply the mention of these issues that was objectionable, not a particular position for or against.

Sir Christopher remark ‘while every Hustings gives them a farce for nothing’ (f.1v), an explicit declaration of the theatricality – with connotations of disreputable vacuity – of parliamentary proceedings, was also marked for omission.

In one exchange, marked for excision, Washball and Mainmast refer to a contemporary MP:

Washball: Why we see you have been obliged to elect one new member already. –

Mainmast: Aye & tho’ its only Wood, egad it answers the purpose very well. – (f.10r)

Matthew Wood (1768-1843) had been Mayor of London 1815-1816 and then elected to the House of Commons in 1817 for the City of London. He had recently presented a Westminster reform petition on 1 June. Mrs. Washball’s thinly veiled ‘there are so many wigs want dressing’ (f.10r) was also marked for deletion. Bronze’s ‘state of the nation’ summary also proved too provocative: ‘Most worthy independant Electors – The Country is in such a State – the Parliament so bad, The Laws so villainous – the trade so unprofitable – the land so uncultivated & the whole Island so miserable’ (f.12r). It is clear why this was suppressed although the objection to Tandem’s declaration that he is ‘perfectly acquainted with every post in the neighbourhood of St James’s’ is more difficult to identify with precision, given the multiplicity of meanings of ‘post’, the word underlined in pencil (f.12v).

The final and most lengthy passage marked for omission is the conclusion of Canvass’s hustings speech. The satirical intent of this speech is biting:

I’ll do more than any of them [the other candidates], - for I’ll never sit easy in my seat till you all represent yourselves till every man Jack of you be members of Parliament – and Salisbury Plain the Parliament house - & as to Liberty – you shall have as much of it as you like, liberty to knock each other down, Liberty to go into a Butchers Shop & a Public House & take the meat & drink the Beer without paying for it, & I promise never to stop in my career, till there’s no law – no taxes, no church – no State – no nothing – but Liberty for ever –’ (f.13v).

Evidently, the satire is directed at the fatuous and glib nature of electoral promises but there is also an undercurrent – intended or not – of radicalism that damned this speech. One can only imagine that Samuel Arnold felt that the speeches were evidently so over-the-top and outrageous that there could be no real political sentiment in play; if this is the case, he was very wrong.

Further reading

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 111-112.

Kathryn Rix, ‘The General Election of 1818’, [https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2018/06/19/the-general-election-of-1818/] Accessed 5 February 2019.

‘Matthew Wood (1768-1843)’ in R. Thorne (ed), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1790-1820, 5 vols(London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1986)

[https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/wood-matthew-1768-1843] Accessed 5 February 2019.