The Dukes Coat (1815) LA 1899

Author

Unknown

Plot

At La Belle Alliance inn on a stormy evening, Henry meets his lover Pauline, the innkeeper’s daughter. Simmerkin, the innkeeper, has been forcibly recruited by Napoleon to help him fight the battle of Waterloo which took place nearby the day before.

Simmerkin has made it home safe from the battle and he laments with Henri that the French have fired the town of Hougoument on their retreat (f.3r). They are joined by Mrs Simmerkin and Pauline for wine and a toast to the Duke of Wellington who was in the inn just an hour previously with an Old Prussian Duke [presumably, this is supposed to be Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, who commanded the Prussian forces]. Mrs Simmerkin suggests that Wellington acted lecherously towards Pauline but her daughter denies that this happened and talks about how magnanimous and chivalrous he was. There is some confusion over whether he was wearing a blue or a scarlet coat which ends with them all extolling Wellington in a song.

Colonel Fitzroy arrives looking for shelter and for someone to summon half a dozen dragoons from the English bivouac at Hougoumont as he has orders from Wellington to dispatch. Henri volunteers and goes. Simmerkin is convinced that Fitzroy is Wellington by his manner, the dispatches he has and the star on his scarlet coat he is wearing but keeps his suspicions to himself and his wife. They act in an obsequious fashion to him, much to Fitzroy’s puzzlement.

Then Marshall (who fought on the French side) arrives bitterly cursing the foolishness of Napoleon and decides to pass as a Hanoverian officer of the English army. Mrs Simmerkin is suspicious and they have an exchange where she lets slip that she is hosting a ‘great man’. Initially, Marshall thinks she is referring to Napoleon but eventually discovers it is actually Wellington she imagines. Marshall sees the opportunity and hurries off.

Marshall summons his soldiers and tells them to capture the ‘Duke’ when he takes his scarlet coat from the inn (f.11r). Simmerkin, inebriated after drinking wine with Fitzroy, puts on the scarlet coat and describes the battle just when the French soldiers enter (f.12r). They seize him and there’s some verbal scuffling. Then Fitzroy enters and Simmerkin blurts out that he’s the real Duke. The French soldiers then go for Fitzroy but Henri returns just in time with the British soldiers. Everything is resolved and Fitzroy ends the play celebrating the upcoming marriage of Henry and Pauline.

Performance, publication, and reception

The play was submitted to the Examiner’s office in late August; Larpent endorsed it on 29 August 1815. The licence was refused and it was not performed. Anna Larpent wrote about the piece in her diary (29 August 1815); unfortunately, the entry is at the bottom of the page and the writing so squeezed as to be illegible to a large degree: ‘Mr L & I alone & he rather worried by [the] silly Farce of the dukes coat a foolish mistaken farrago [illeg] be [illeg] [impertinence?] [illeg] to [Ld] Ht LC about it’ (f.170r).

The legible words suggest that Larpent was sufficiently concerned about the piece to consult with the Lord Chamberlain, the marquess of Hertford. If he did, Hertford confirmed Larpent’s view and refused the licence. At the end of the month, Anna Larpent refers coldly to the play again when she records her monthly ‘Recapitulation of Employment in August’: ‘Dukes Coat. Vulgar stuff’ (f.171r).

The news came as a surprise to the author who quickly arranged to have it published. The Advertisement to the published version, dated 4 September 1815, contains a helpful defence of the drama. We may also note that the author chooses to remain anonymous.

Commentary

The manuscript (LA 1899) shows only two interventions, both made with a pencil. The major point of interest about this example of theatrical censorship is that the piece was refused a licence outright—with, it appears, no chance to rewrite—despite the relative mildness of the text. We can infer that the tone of the piece was deemed simply too discordant with the jubilant national mood and the reverential attitudes toward the Duke of Wellington.

The context for this play was the recent Battle of Waterloo, fought on 18 June 1815. The battle, in which a British-Prussian coalition defeated Napoleon’s French army on Belgian soil, marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Widespread and celebrations in Britain and beyond followed and this drama was intended to piggyback on those for Mr Raymond, probably James Grant Raymond (1768-1817), for whose benefit night this was written. The author explains that it was inspired to a degree by a French piece L’habit de Catinat. This was written by Maurice Ourry, staged in 1814, and the author of The Duke’s Coat saw the production.

The first intervention underlines an allegation of amorous behavior on the part of the alleged Duke of Wellington. Mrs Simmirkin describes to her husband an encounter between the Duke and their daughter, Pauline.

Sim: Aye but what did the English Duke?

Pau: (looks down)

Mrs S: Aye Aye hussy you may well look ashamed why would you believe it Simmirkin – he chucked her under the Chin, said she was a pretty girl – very like her mother, & gave her a kiss. (f.3v)

The drama makes clear that the Duke of Wellington is never actually in the play but Larpent must have been uneasy about any imputation of ribald behavior associated with him. The author hypothesizes about Larpent’s decision in his Advertisement:

What the offence taken against this trifle is, does not appear. That it is a mere trifle, and perhaps a dull one, I admit; but these are not, I presume, faults in a Licenser’s eyes. Is it possible that he (like the Innkeeper in the Farce) mistakes an Aide-de-Camp for the Duke of Wellington himself, and objects (as he naturally might) to exhibiting his Grace on stage? (v)

The writer is being a little disingenuous as there is certainly some mildly subversive humour is staging the possibility of such an exalted personage behaving in this way, a point he might implicitly concede by defending himself against such a charge:

The Duke of Wellington’s name is indeed mentioned; but surely the Licenser cannot think there is any indecency in mentioning that name – that glorious name which all Europe repeats with applause and admiration. (vi)

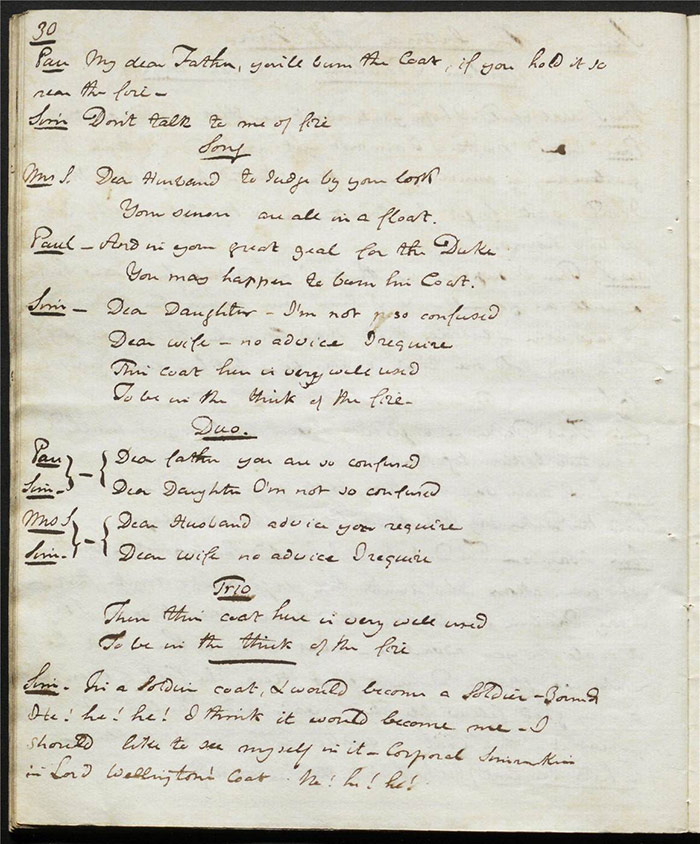

The second passage that is marked as problematic is later in the play when a drunken Simmerkin describes the battle to his family:

Sim: […] Yes here after the toils of a Glorious Day stands the Duke of Wellington – I will explain the whole affair to you – here you see – this was the order of battle – on the left here – (where Pauline stands) is my Infantry on the right (where his wife stands) are the old household troops – Myself about in the centre – My Allies advancing in the rear – well – we charge – they charge – we fly – they fly – they rally – we charge again – we rout them – but just at the most important moment a Column of the Old Guard led by the little Corporal himself – turns my flank – presses close upon me & is on the point of making me Prisoner – (f.13r)

This entire paragraph is marked with a penciled line in the margin. The Advertisement appears to address this specific point, suggesting that, on reflection, he recognized that he got the tone wrong. Nonetheless, he refuses to concede the point:

It has been suggested to me, that the Licenser may think the Battle of Waterloo too grave and tragical a subject for an Interlude: to this supposed objection I answer, that however indecorous it might be to introduce on the Stage the painful details of so recent an event, there surely can be no indecorum in omitting all such details, and in representing a little comic anecdote, which is supposed to have taken place after the battle, and at a distance from the field of action, and which is so little connected with Waterloo, that it was first told of the night after the battle of Marsaille [sic], and might be equally told of the night after the battles of Blenheim or Rosbach. (vii)

The author concludes his Advertisement by pointing out that other celebrations of the battle had not required a licence despite there being ‘indecorous dancing’, indelicate eating and drinking, with sundry abominable bumpers’, and ‘much shameful joy’. But despite his perception of unjust treatment, he is adamant that theatre censorship is ‘just and necessary’; it is just a pity, he writes, when that it is ‘exercised on trivial and improper occasions’.

Further reading

The Duke’s Coat; or, The Night after Waterloo: A Dramatick Anecdote; Prepared for representation on the 6th September at the Theatre Royal Lyceum (London: Printed for J. Miller, 1815).

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library, HM 31201

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 106-107.