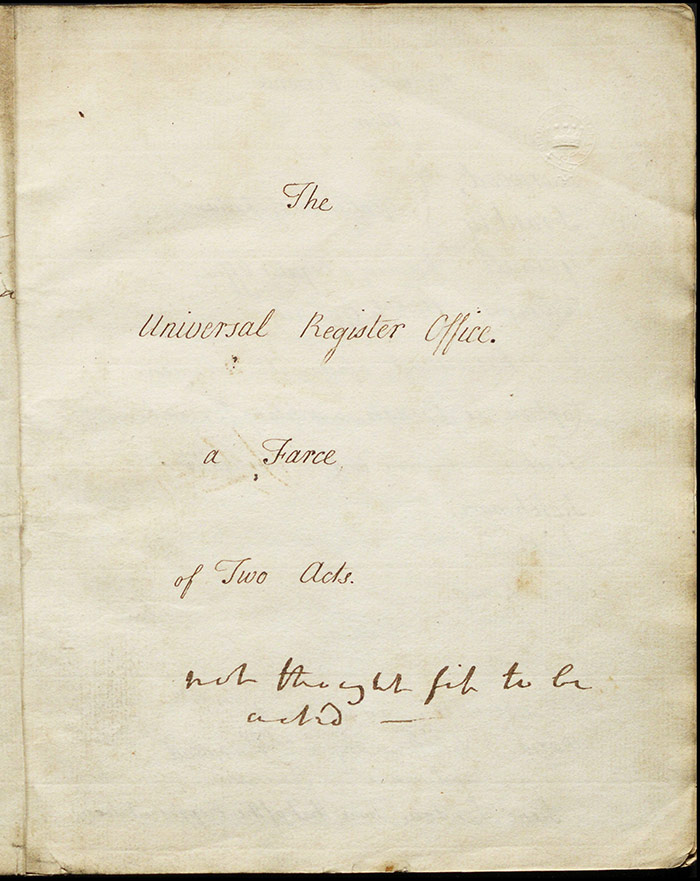

The Universal Register Office / The Register Office (1761) LA 189/196

Author

Joseph Reed (1723-1787).

Reed was born into a rope-making family in Stockton-on-Tees, co. Durham. He took over the family business, eventually running it from London. He was an enthusiastic writer and his five-act tragedy Madrigal and Truletta (mocked as a ‘truly humorous burlesque’ by Samuel Foote in his Additional Scene – see below) was his first staged work (CG, 1758). It only had one performance and was panned by Smollett in the Critical Review. Reed also contributed to a pro-Bute journal The Monitor as well as publishing a defence of Garrick from the salacious accusations of William Kenrick’s Love in the Suds (1772).

The Register-Office was not the only piece which emanated from his personal friendship with Henry Fielding: he also wrote a comic opera Tom Jones (CG, 1769) which was lauded by Fielding. He penned another five-act tragedy Dido (DL, 1767) with Garrick contributing a prologue but this did not succeed. Reed would later attack Thomas Linley in 1787 for not restaging the tragedy; it was eventually revived as The Queen of Carthage in 1797 (DL).

Plot

The plot of both The Universal Register Office and The Register Office are largely the same. Here the plot of the original submission (refused a licence) is given. The note on ‘Censorship’ will highlight some of the main differences between the plays including, where necessary, those relating to plot.

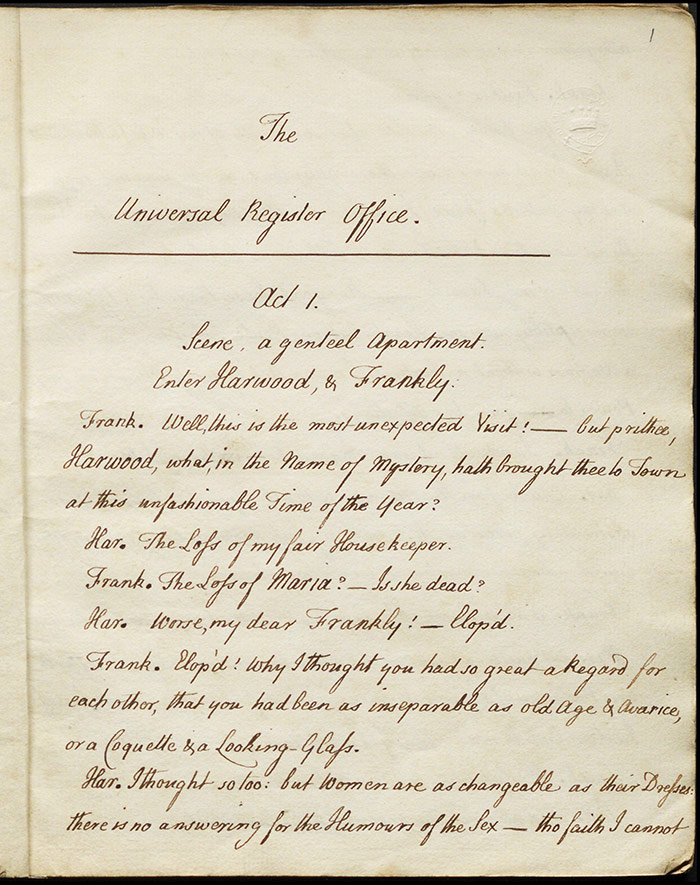

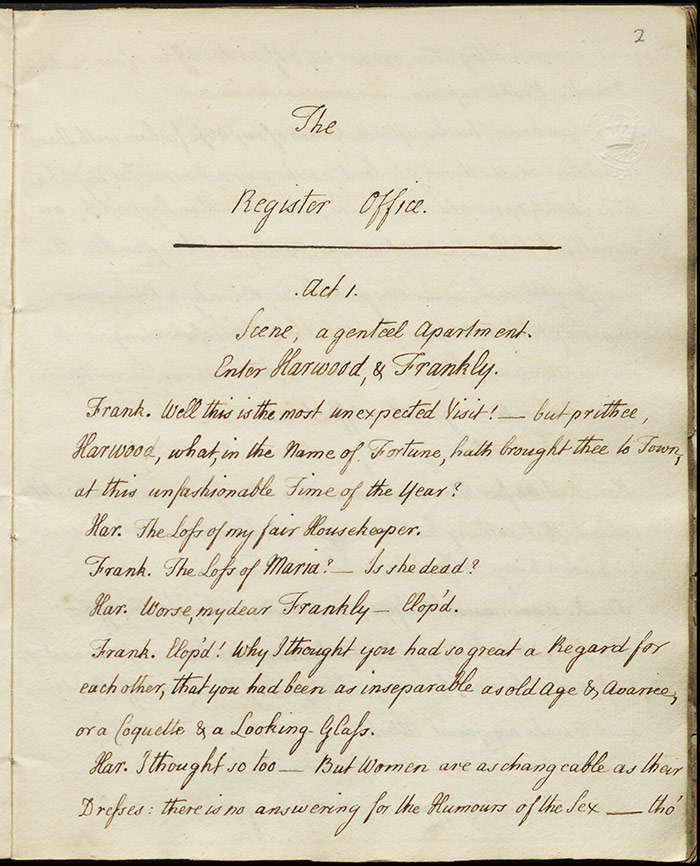

Act 1

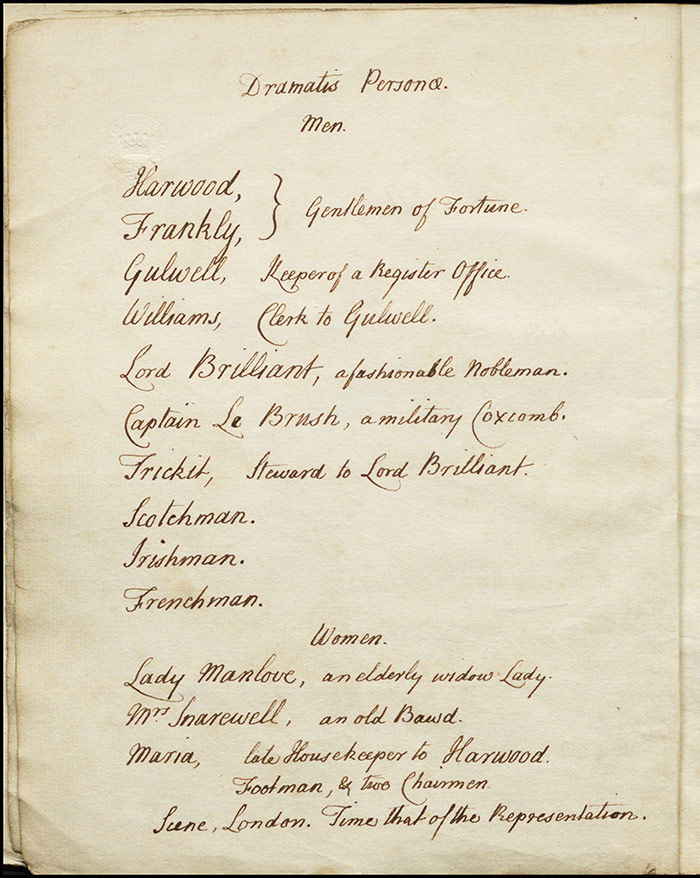

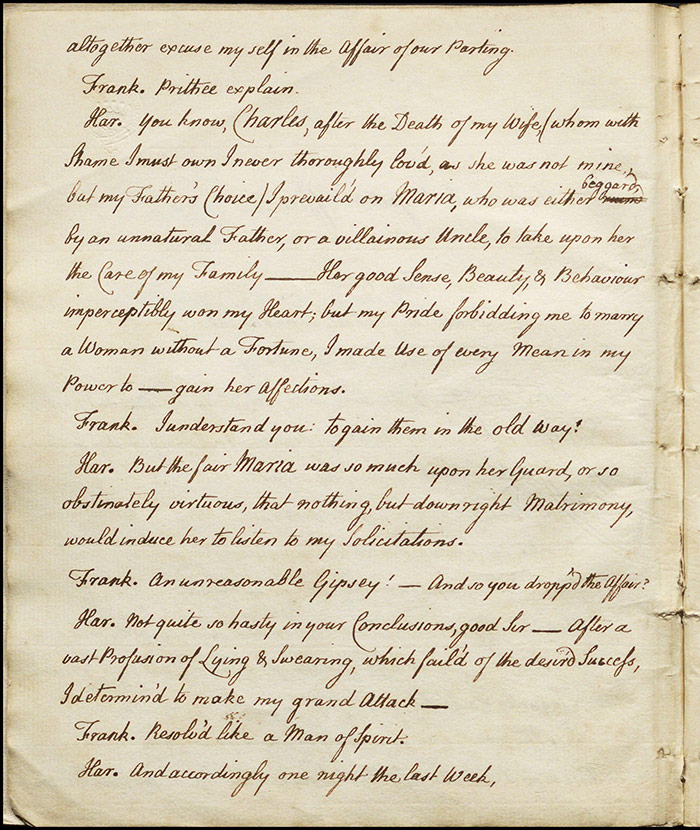

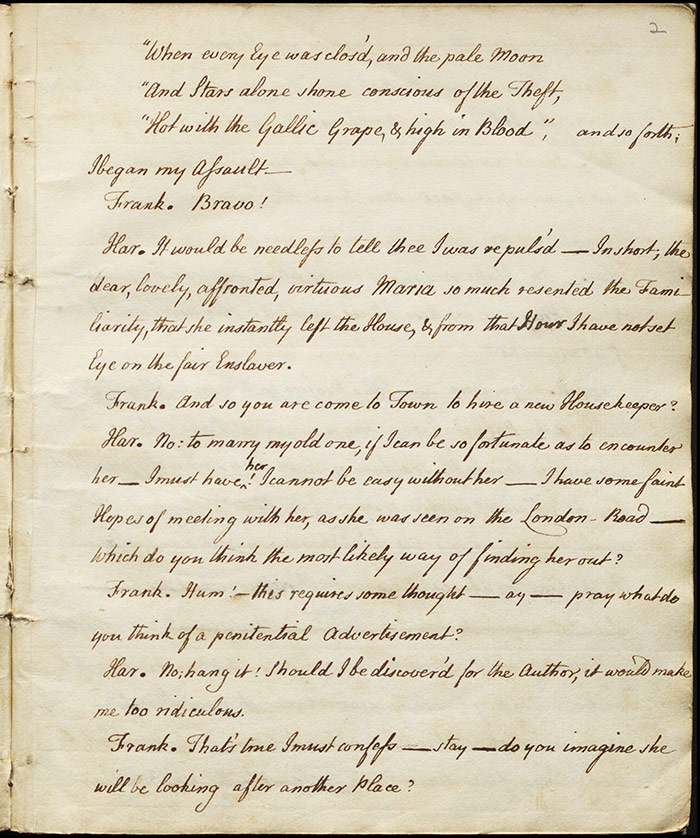

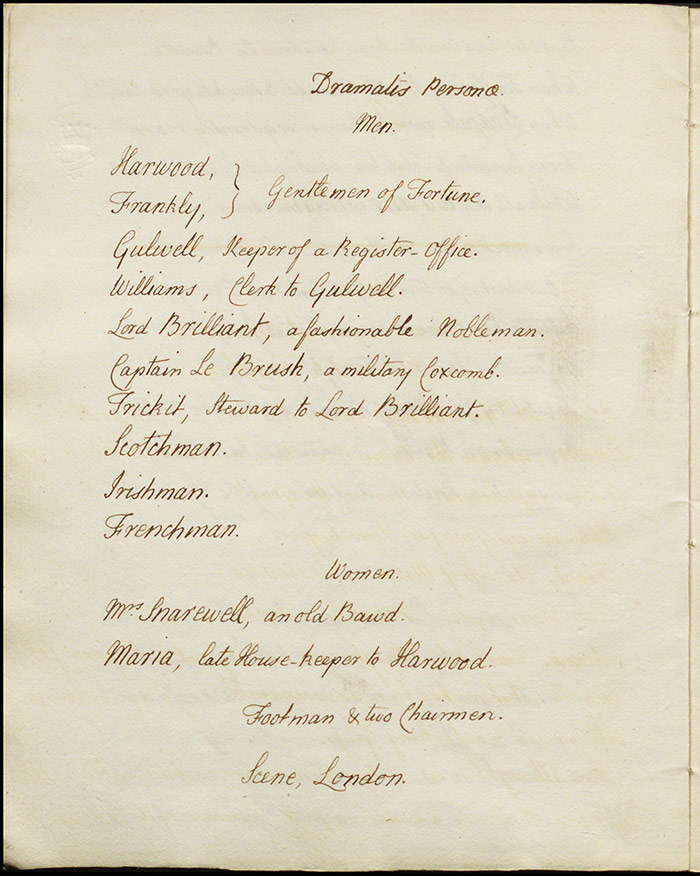

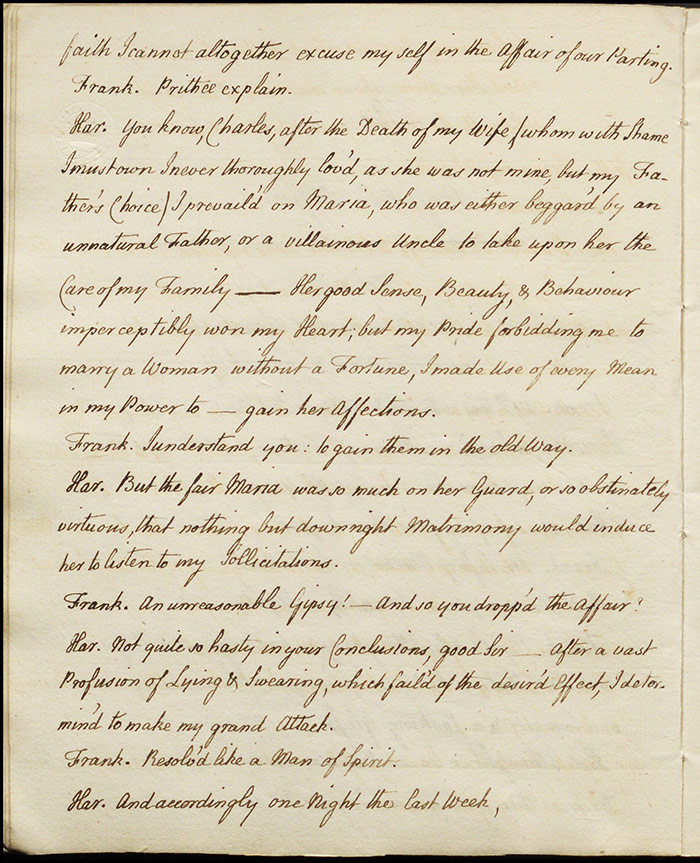

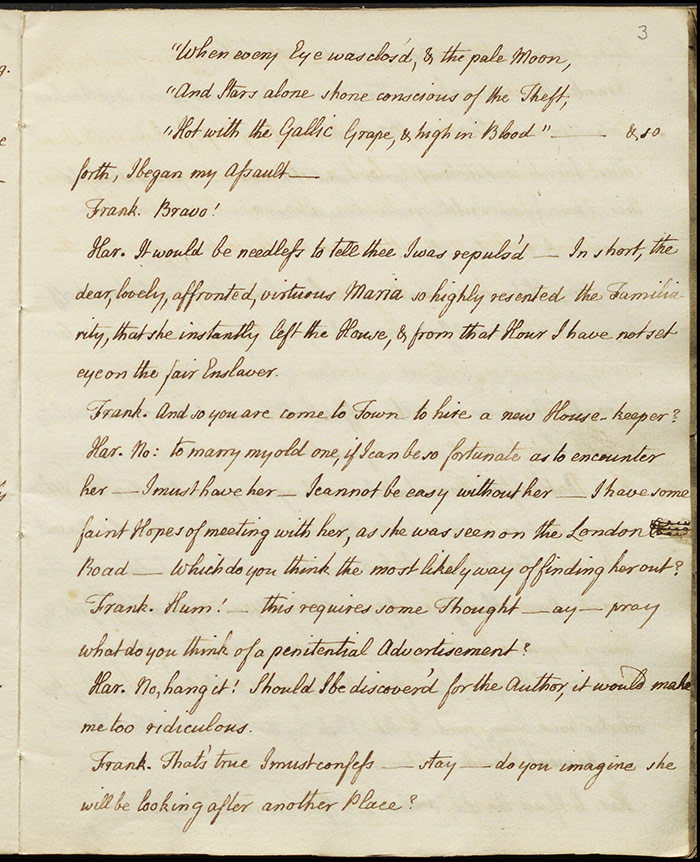

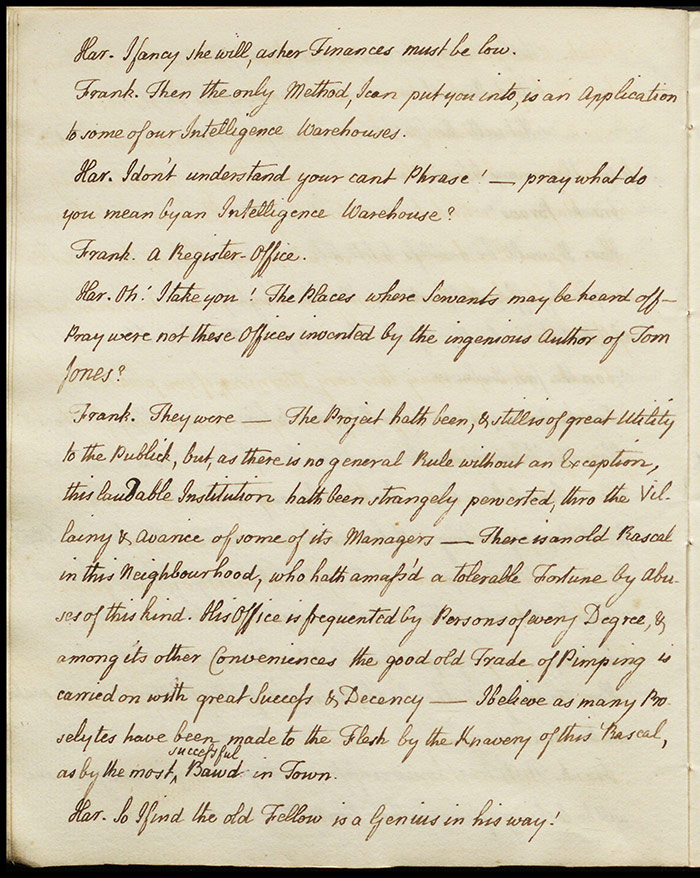

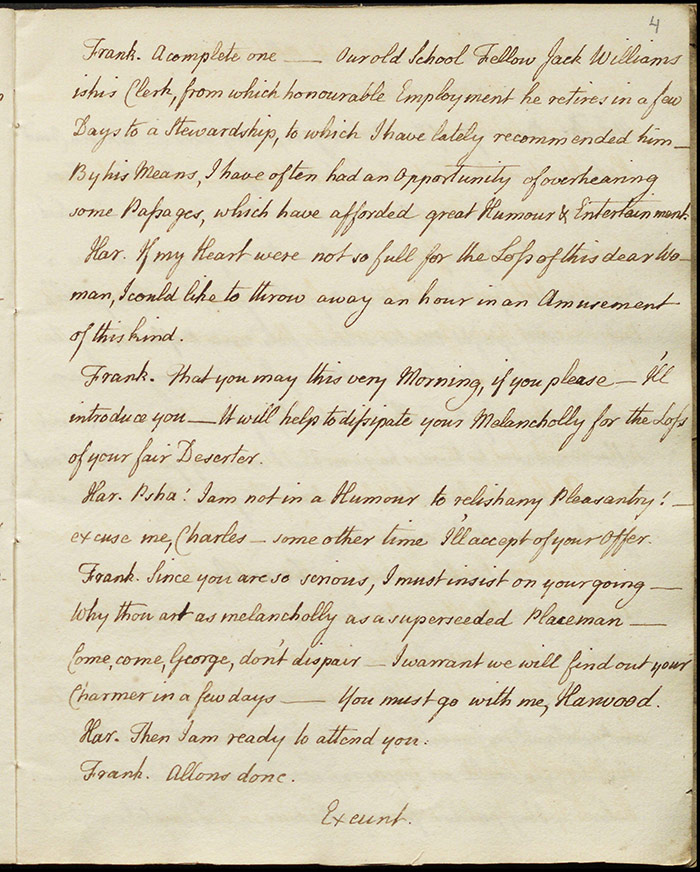

George Harwood and Charles Frankly, ‘Gentleman of Fortune’, are in an apartment. Frankly is surprised to find Harwood come to town at this unfashionable time of year but Harwood relates that he has come in search of his beautiful housekeeper, Maria. After he attempted to rape her, she fled the house and came to London. Penitent, he now wishes to marry her. Frank commiserates and suggests he go to the register office to cheer himself up: their old school friend Jack Williams works there as the clerk and can let them listen in on clients.

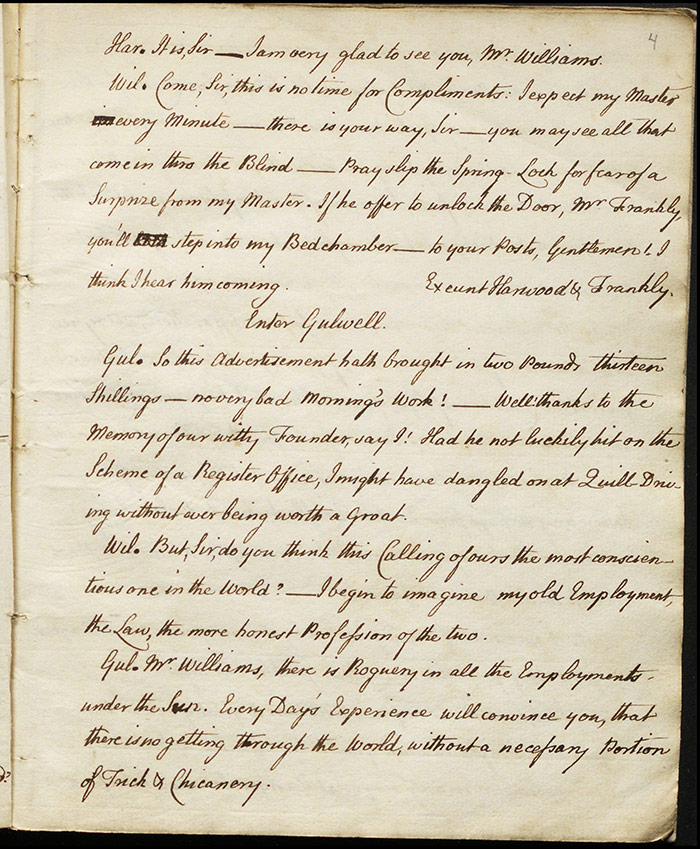

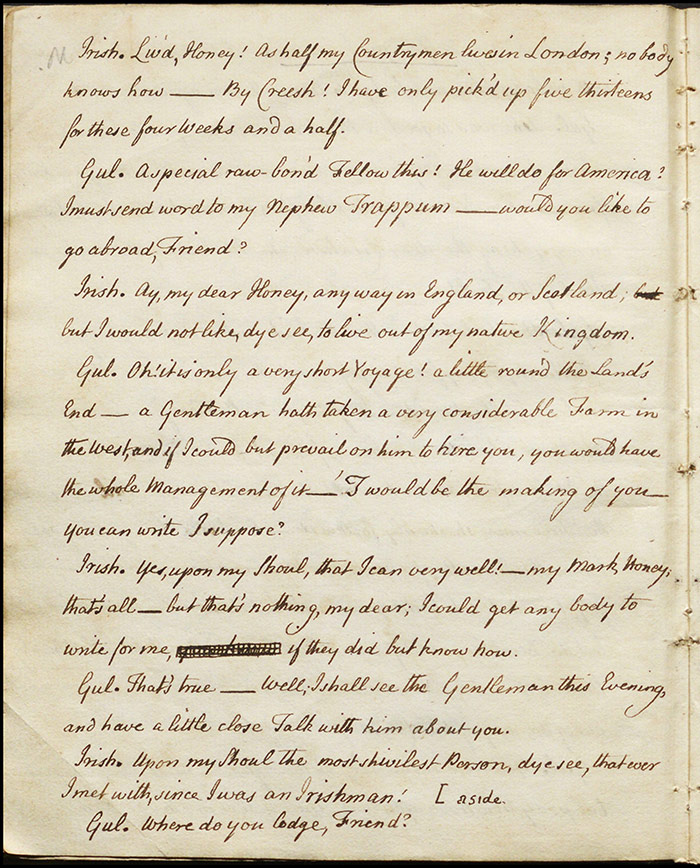

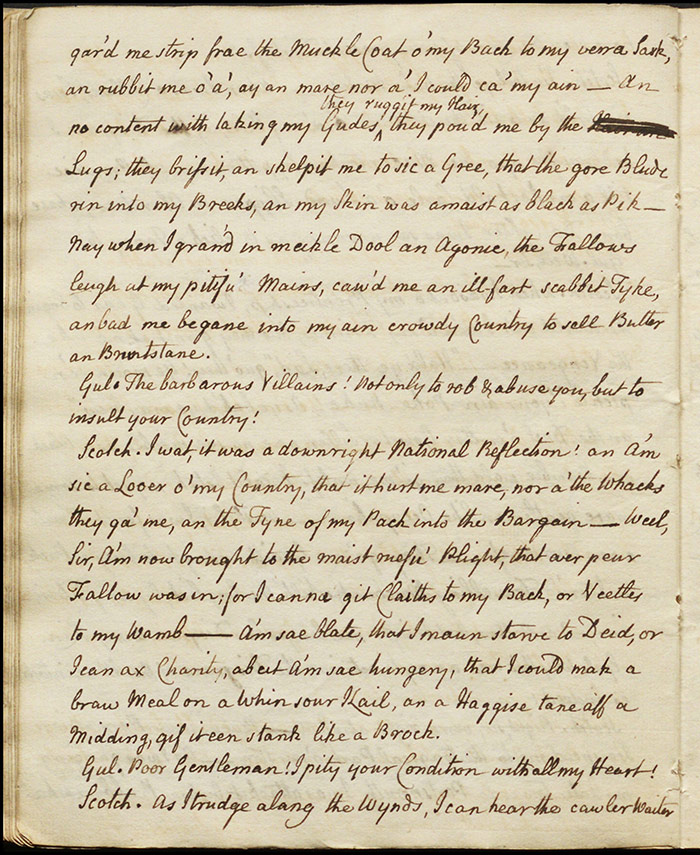

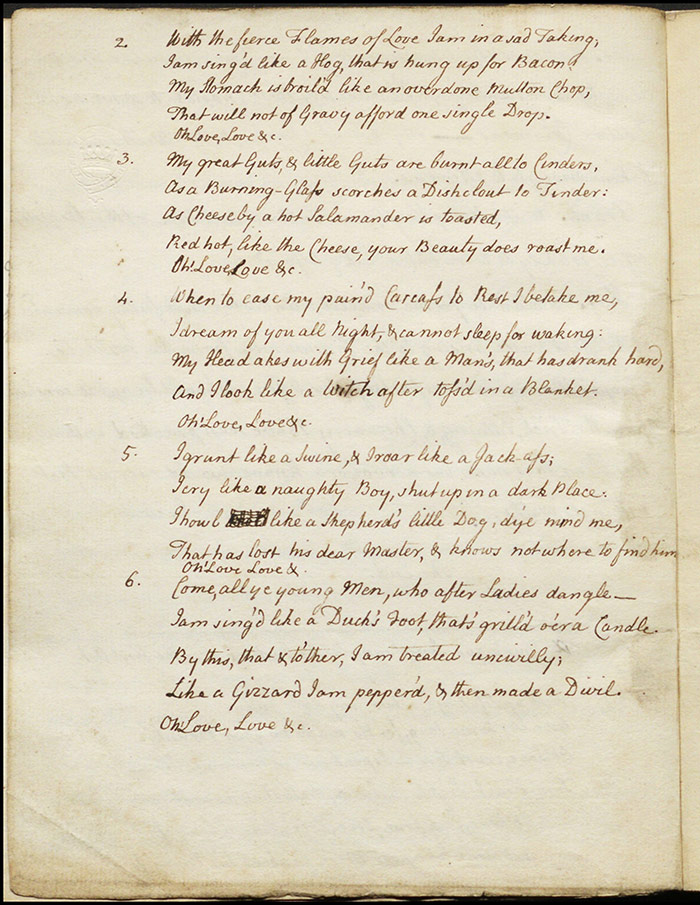

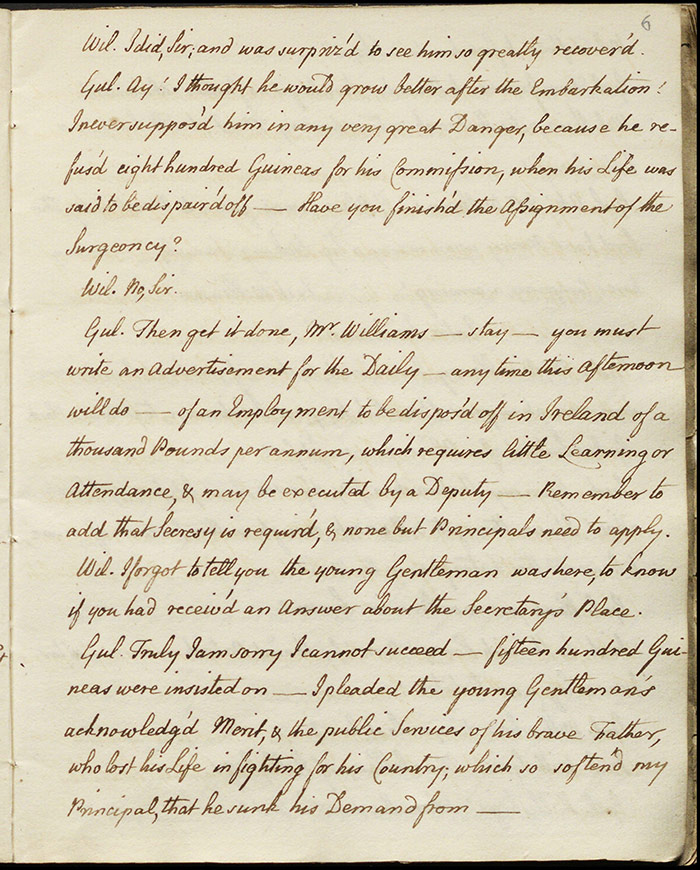

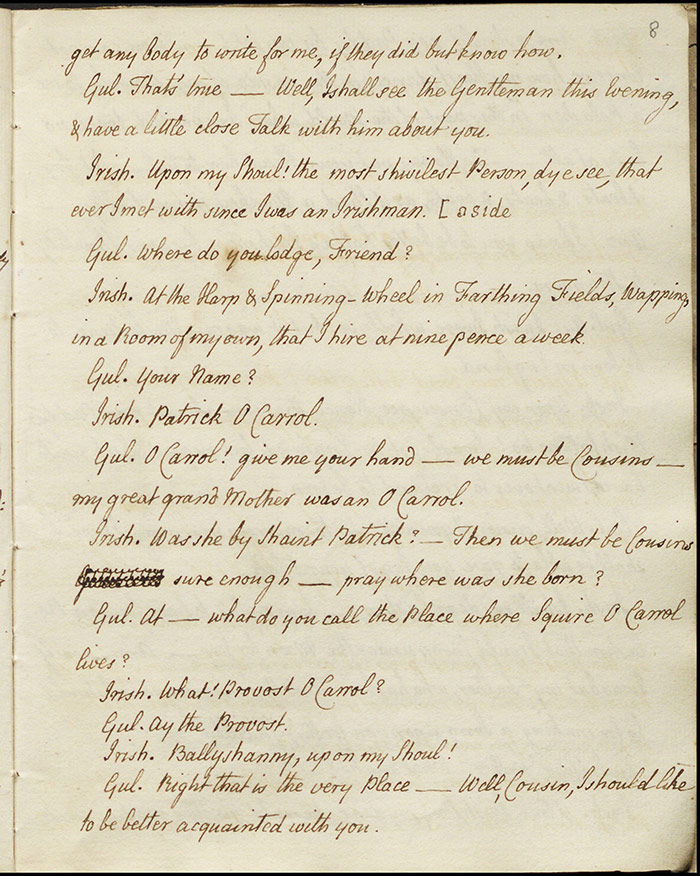

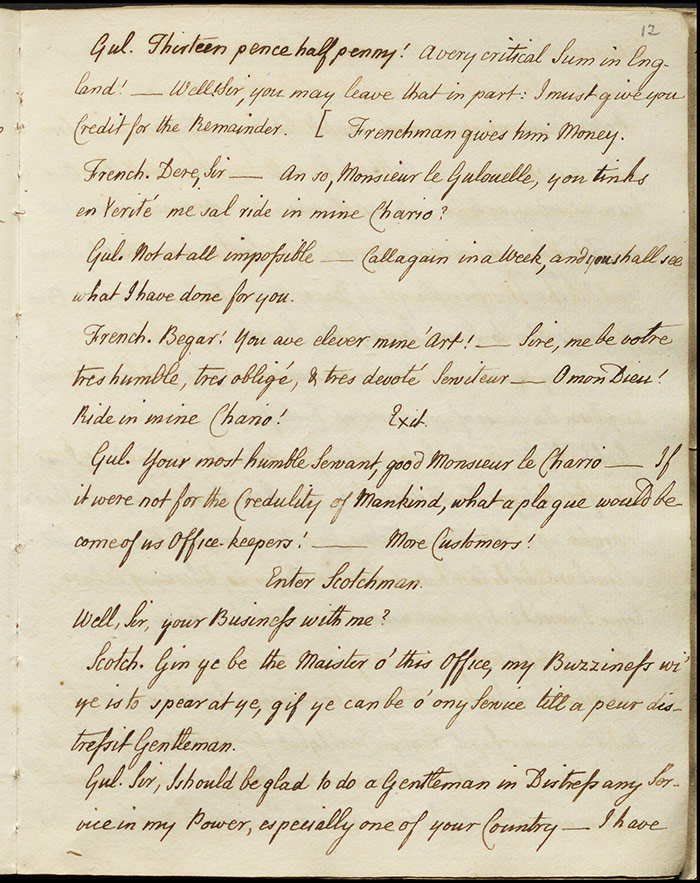

[Scene 2; f.3v]

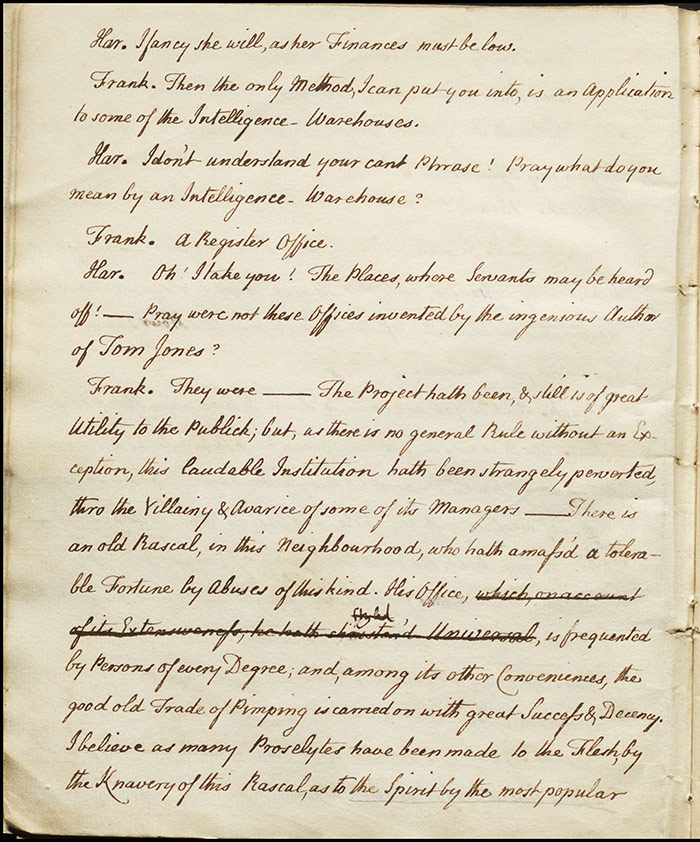

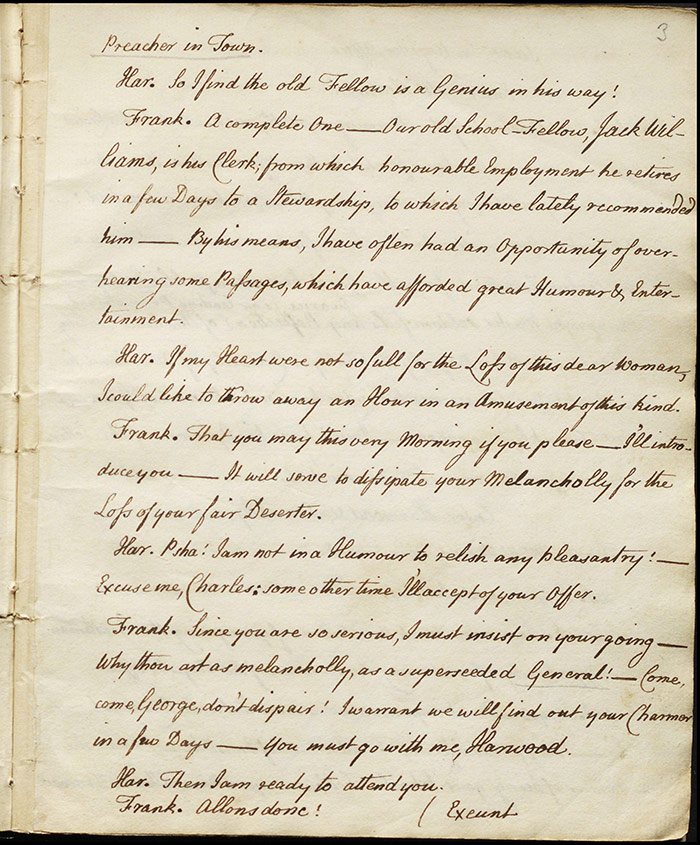

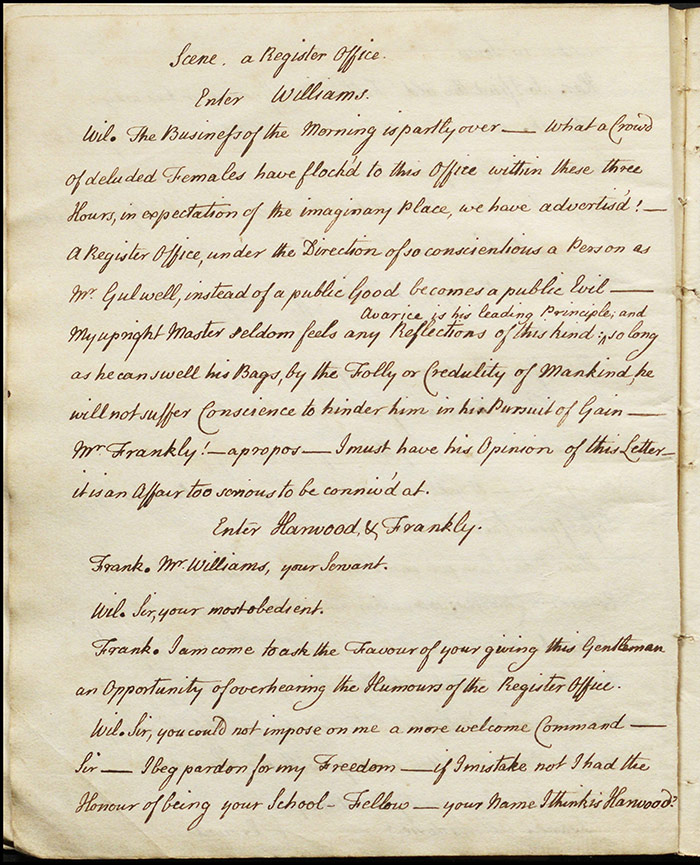

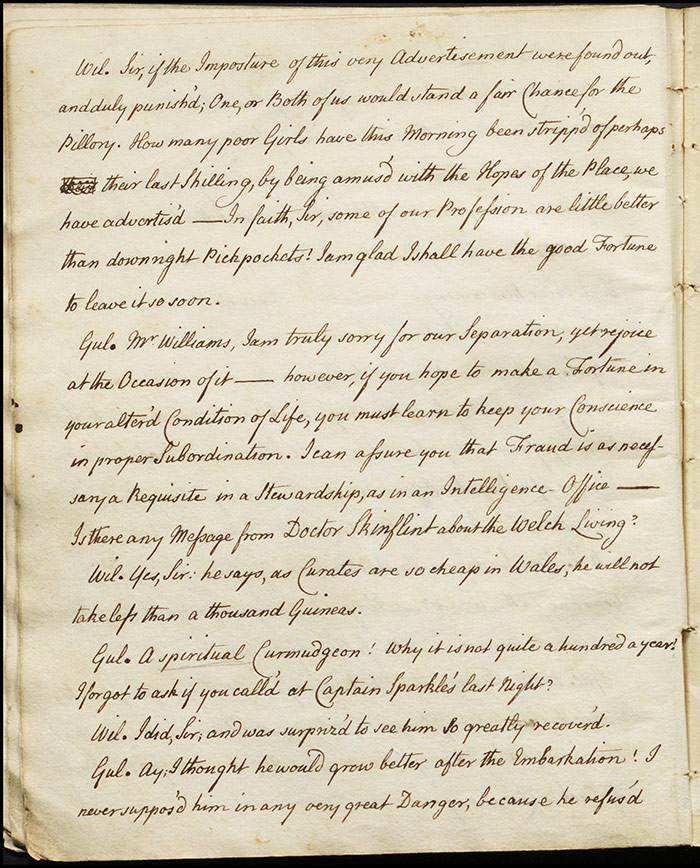

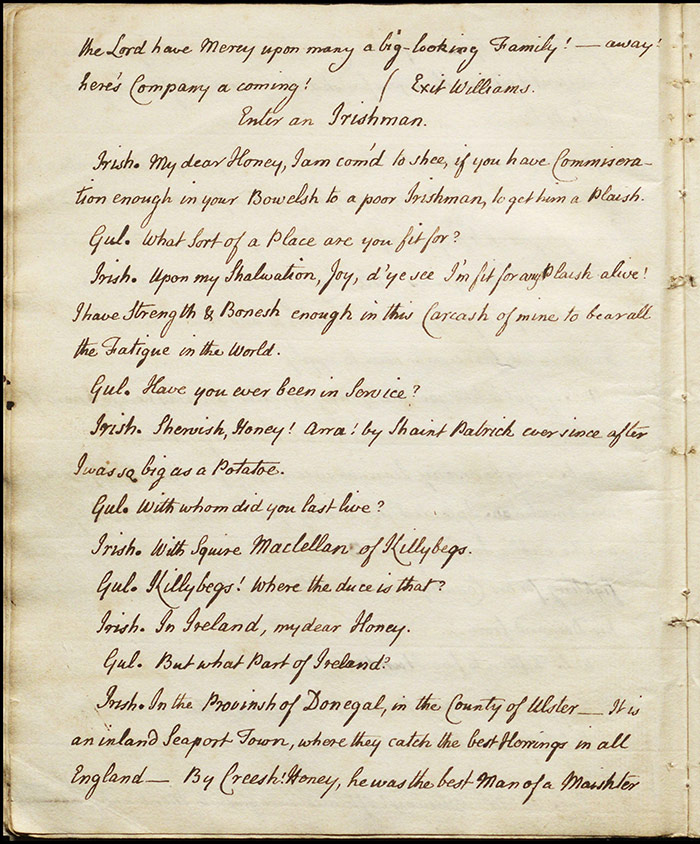

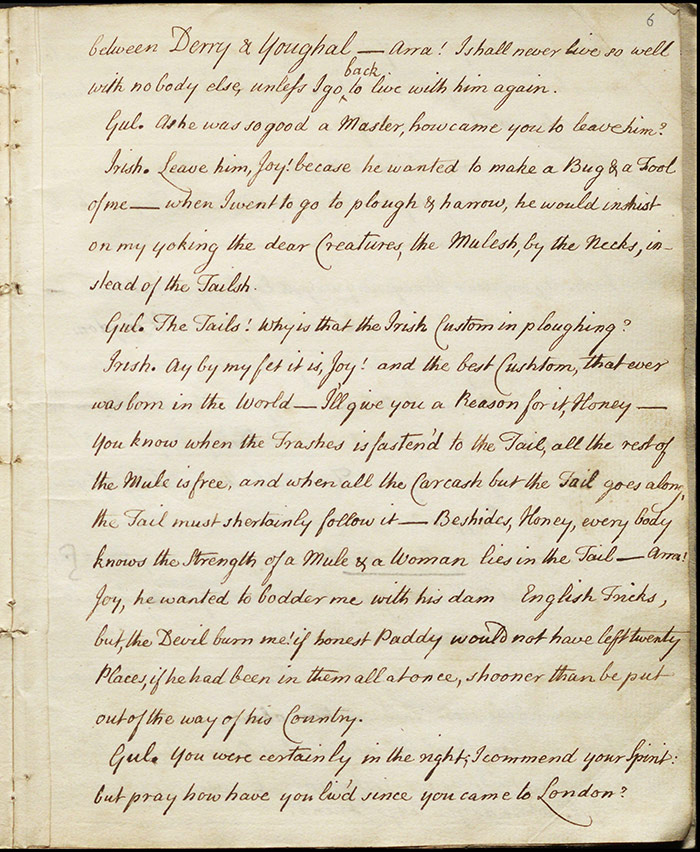

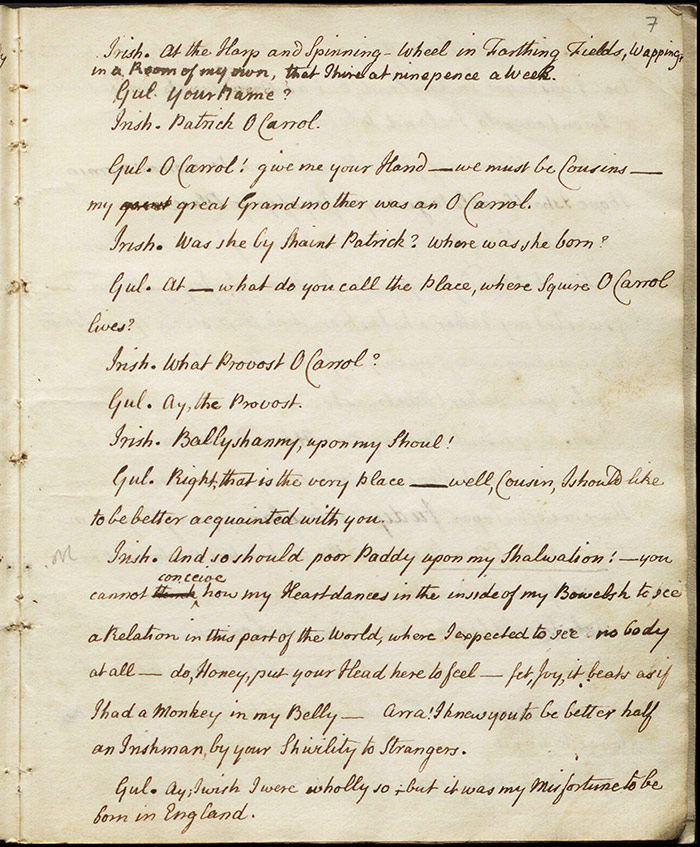

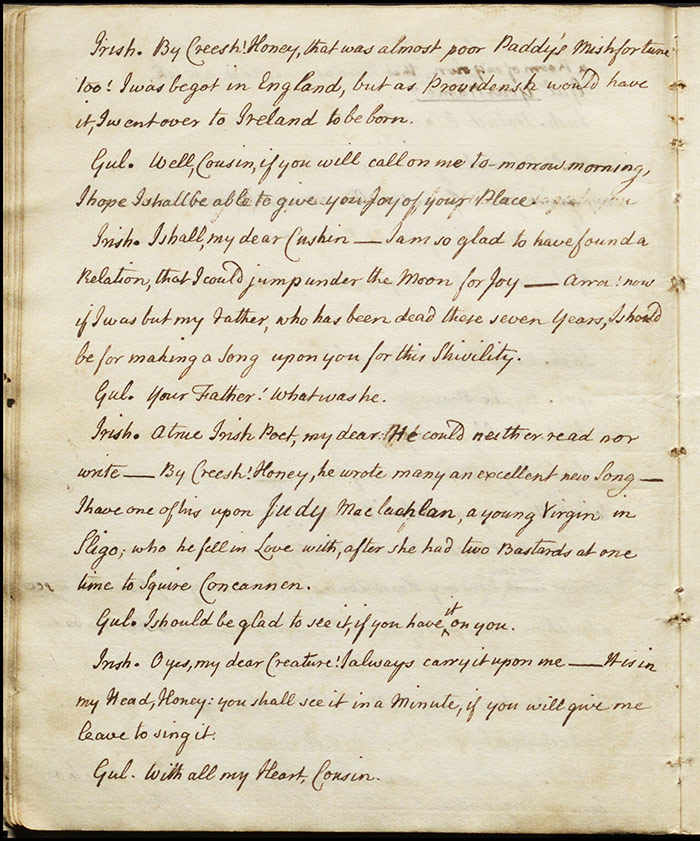

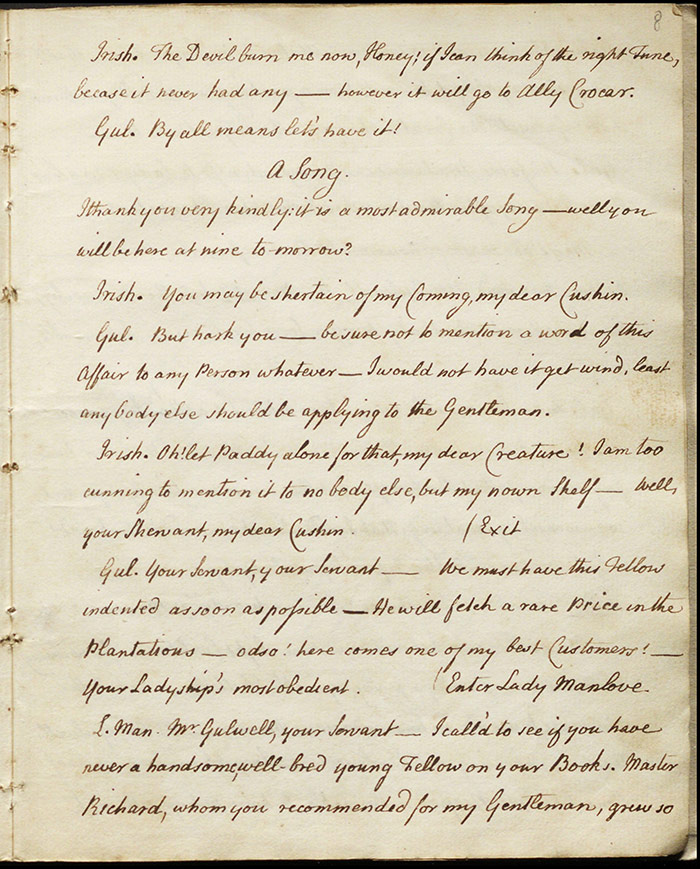

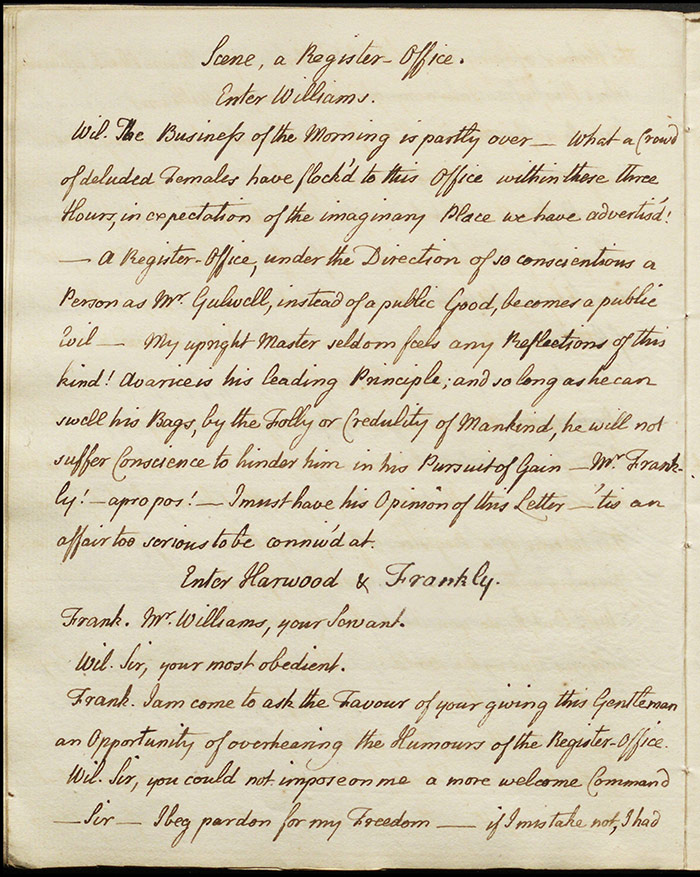

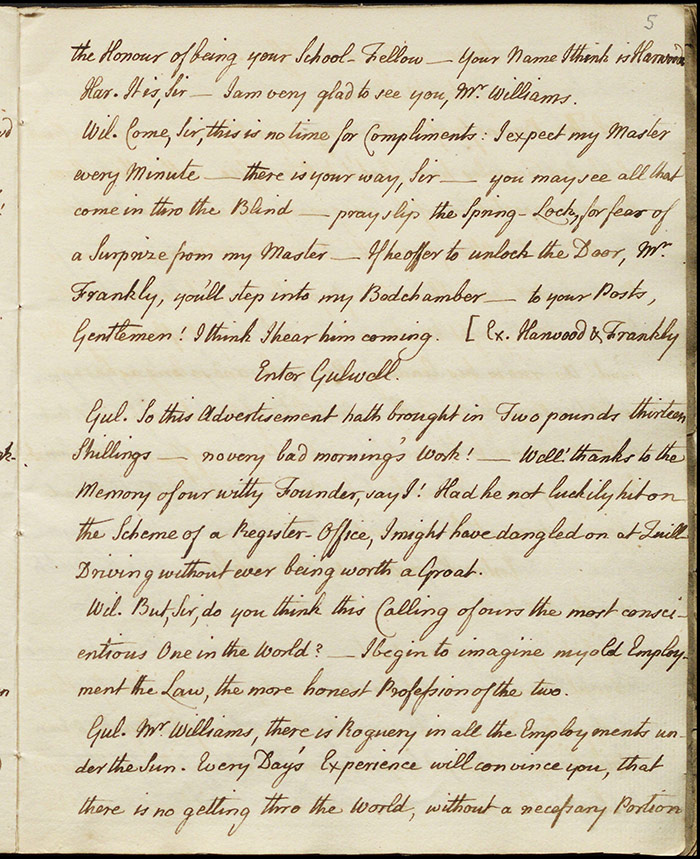

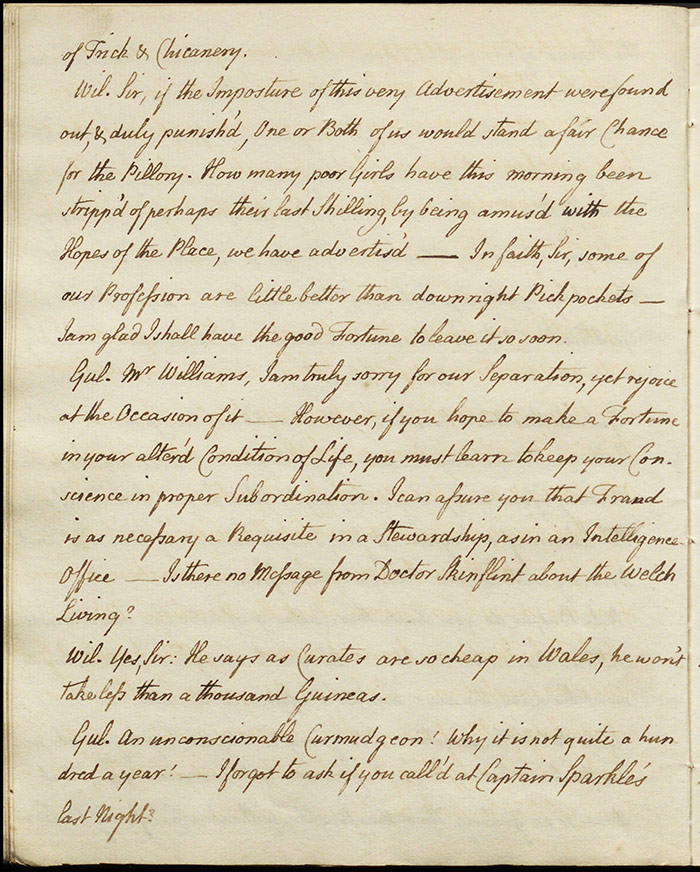

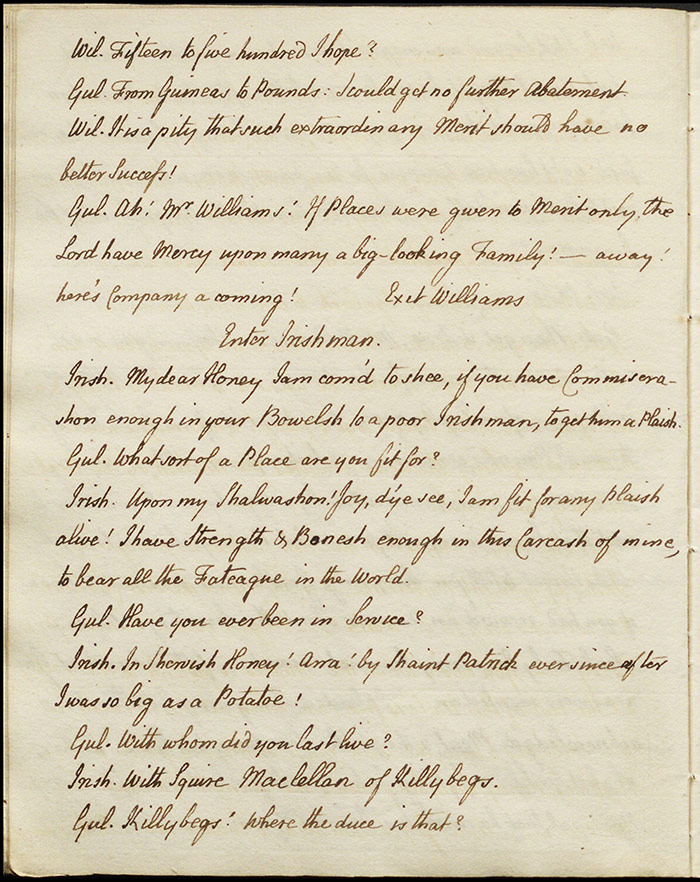

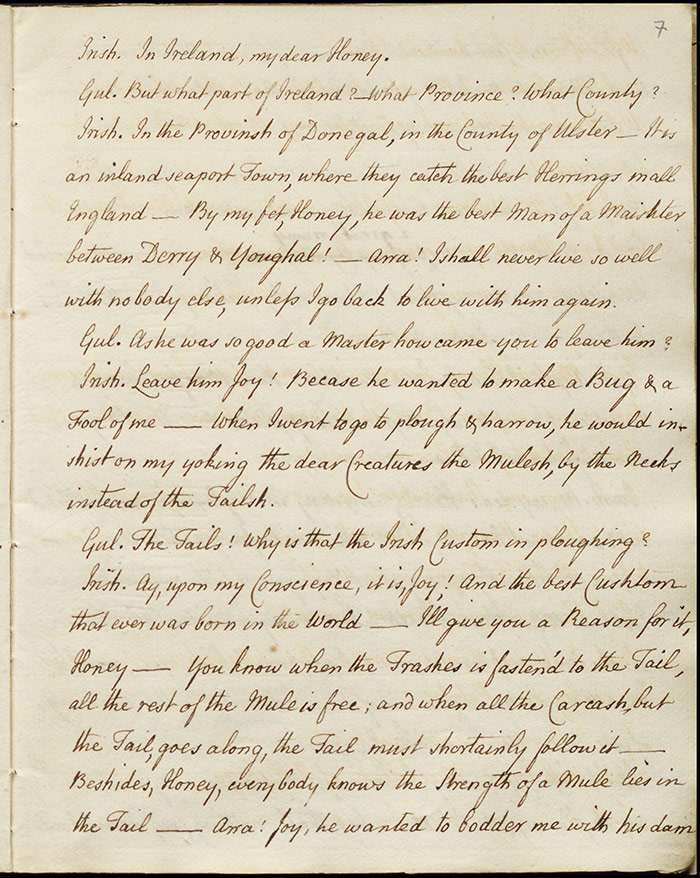

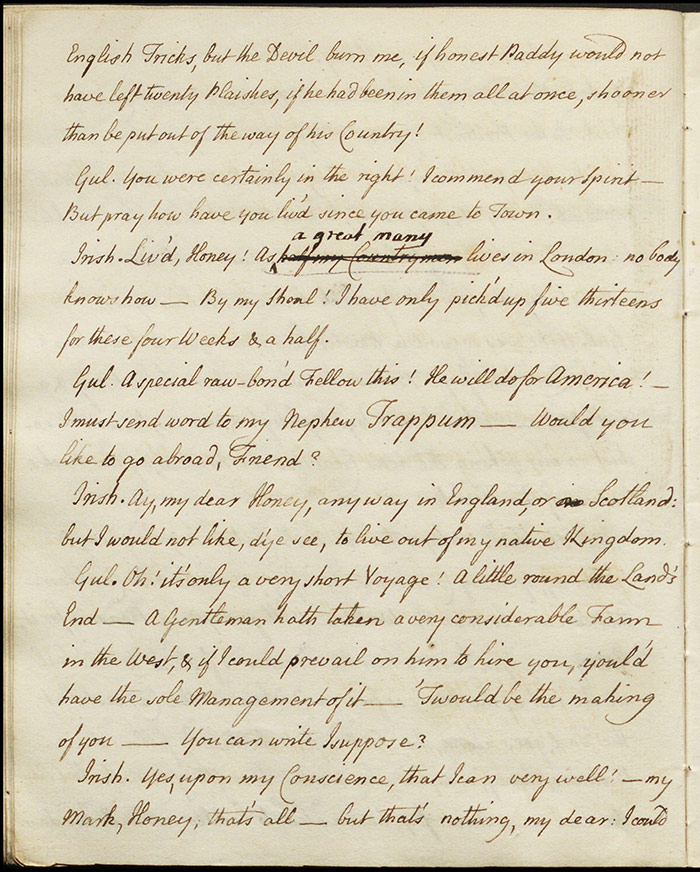

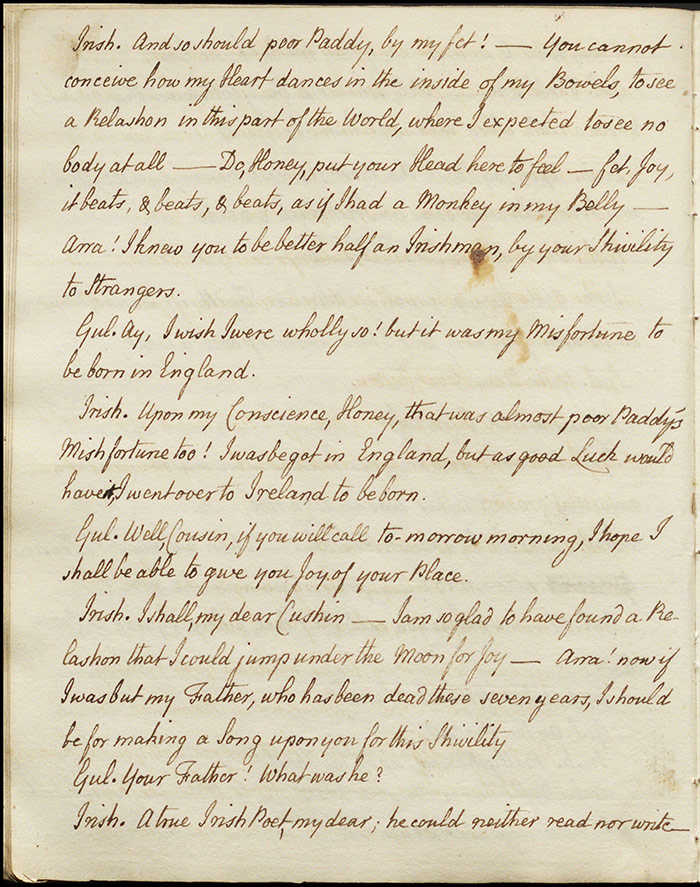

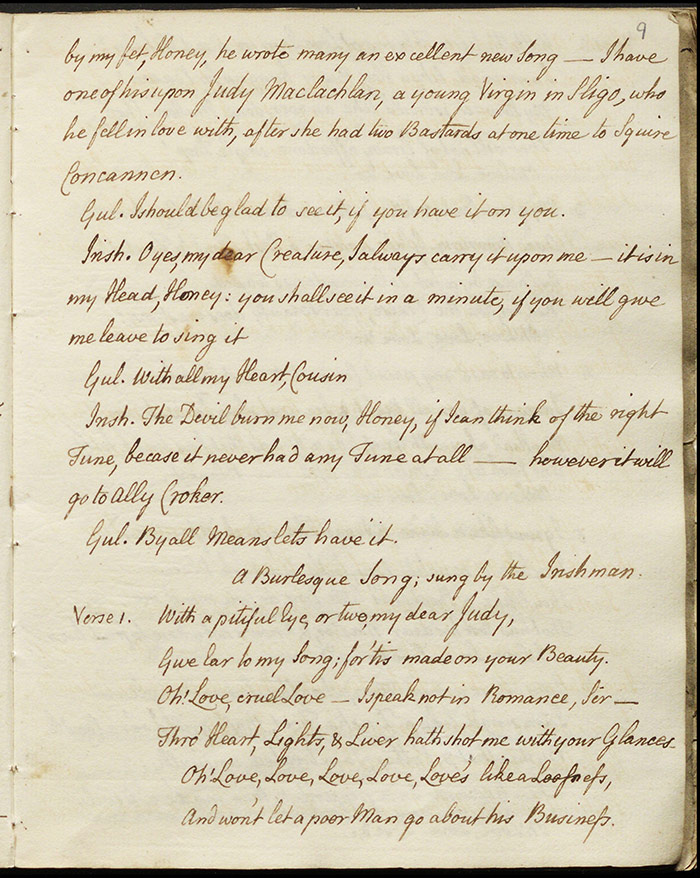

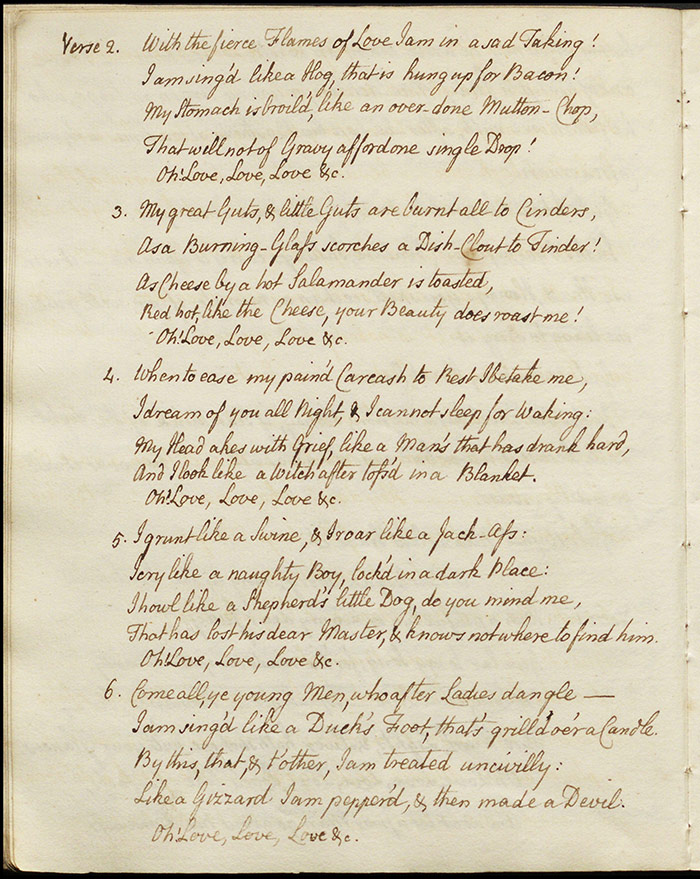

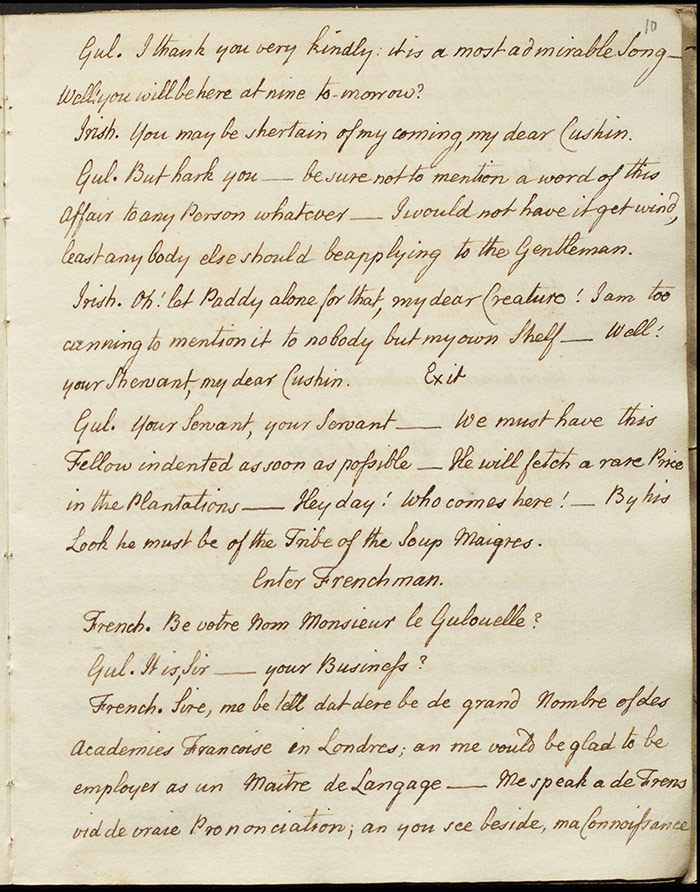

Enter Jack Williams, at the register office. He comments on the unscrupulous business practices of his master, Mr Gulwell, who advertises fictitious places and collects fees from unsuspecting applicants. Enter Frankly and Harwood. Williams is very happy to accommodate them, not least because he wants to discuss a letter he has received which he deems very serious, and he hides them quickly just before Gulwell enters. Gulwell is delighted at the morning’s takings and dismisses Williams’s scruples by insisting that ‘there is no getting through the World, without a necessary Portion of Trick and Chicanery’ (f4r). They discuss some current cases before an Irishman, Patrick O’Carroll, enters. He is looking for ‘a Plaish’ (f.5v) and Gulwell immediately thinks of tricking him into indentured labour in American plantations. Delighted, O’Carroll sings a song before promising to return in the morning after Gulwell has made (fictitious) enquiries on his behalf.

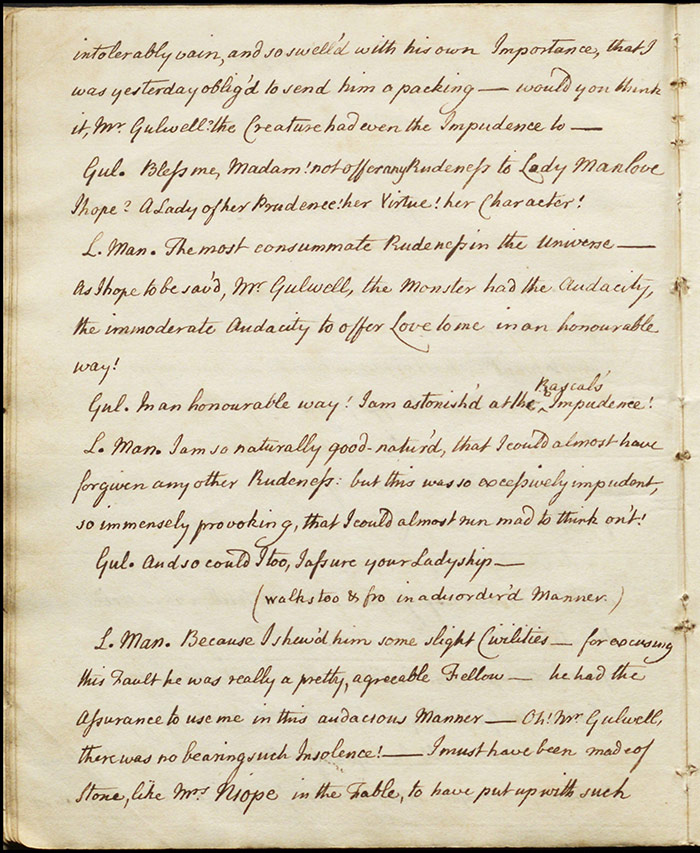

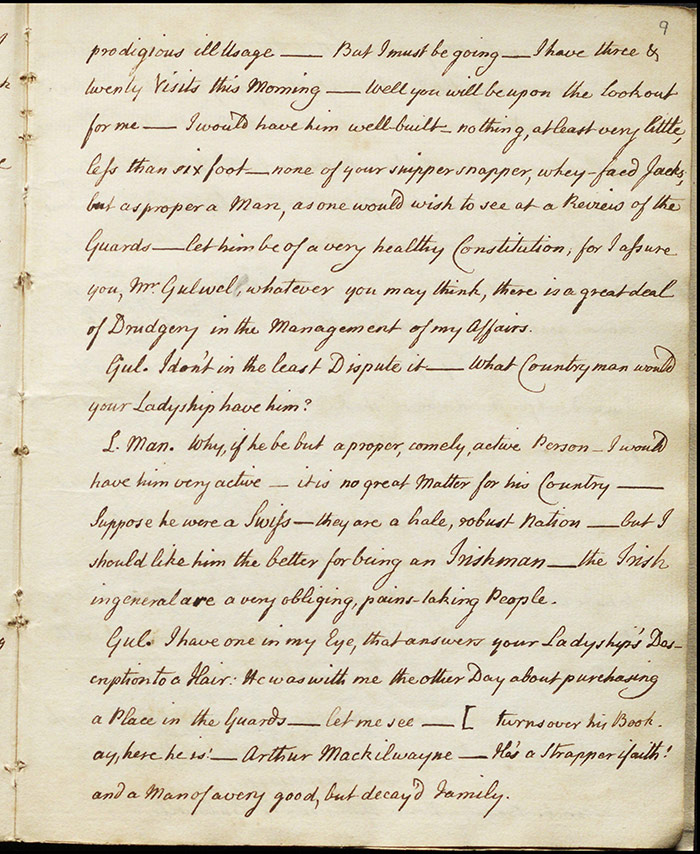

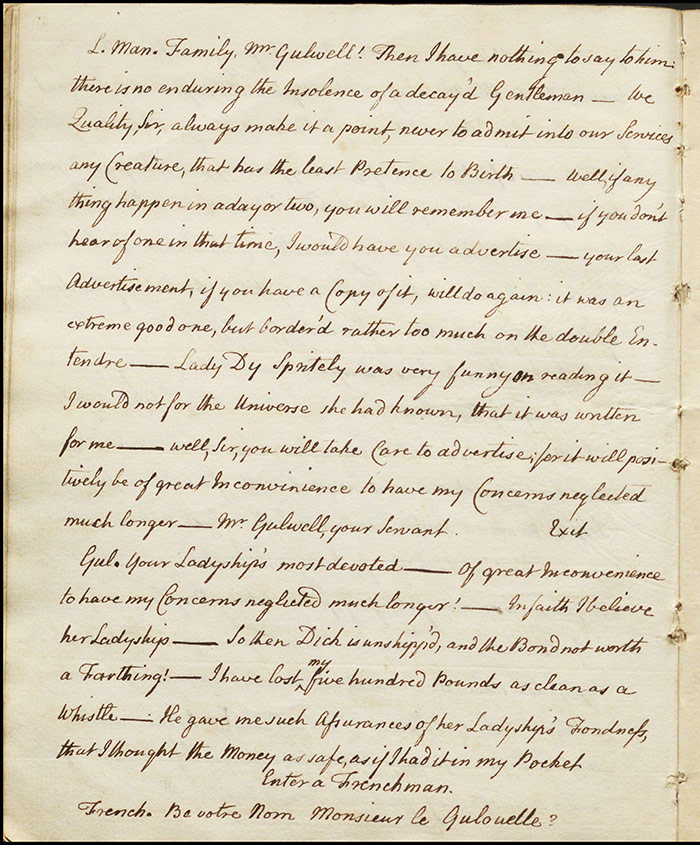

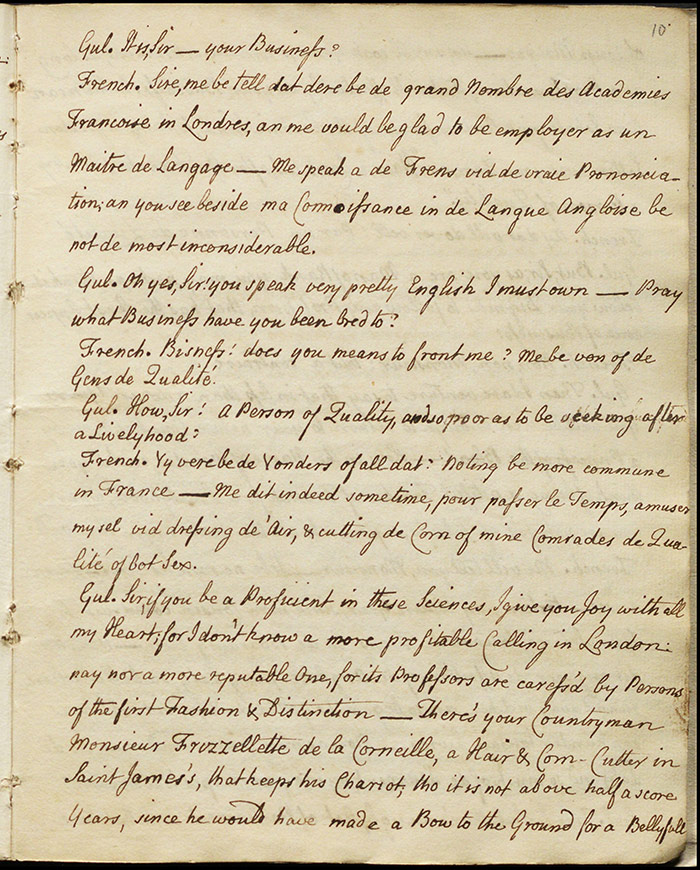

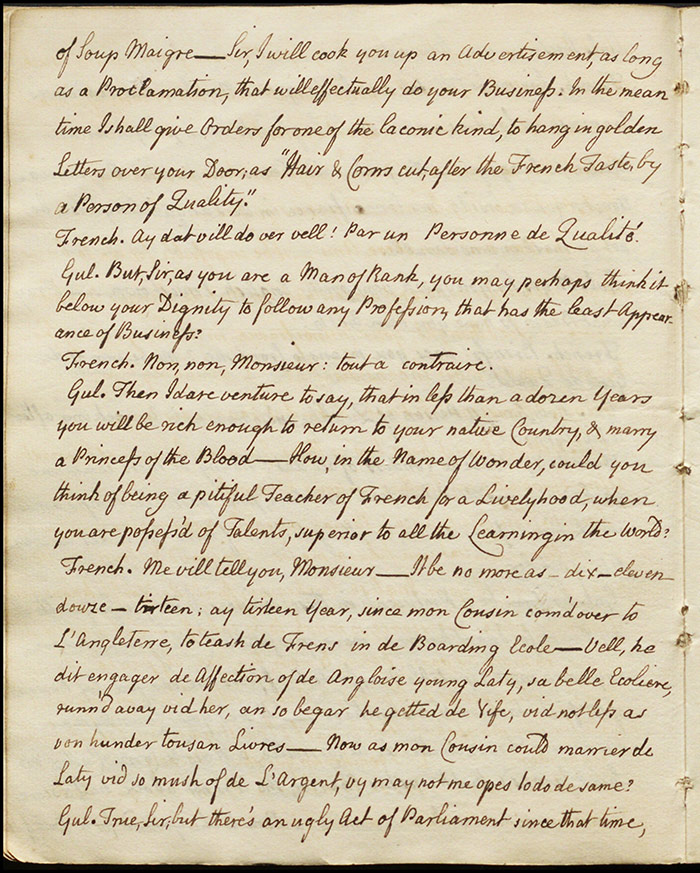

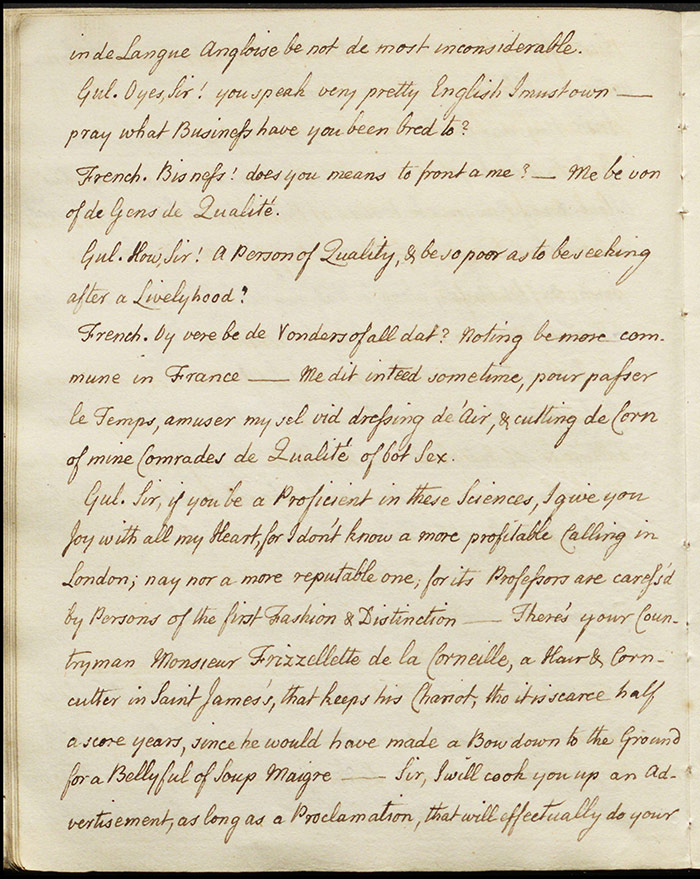

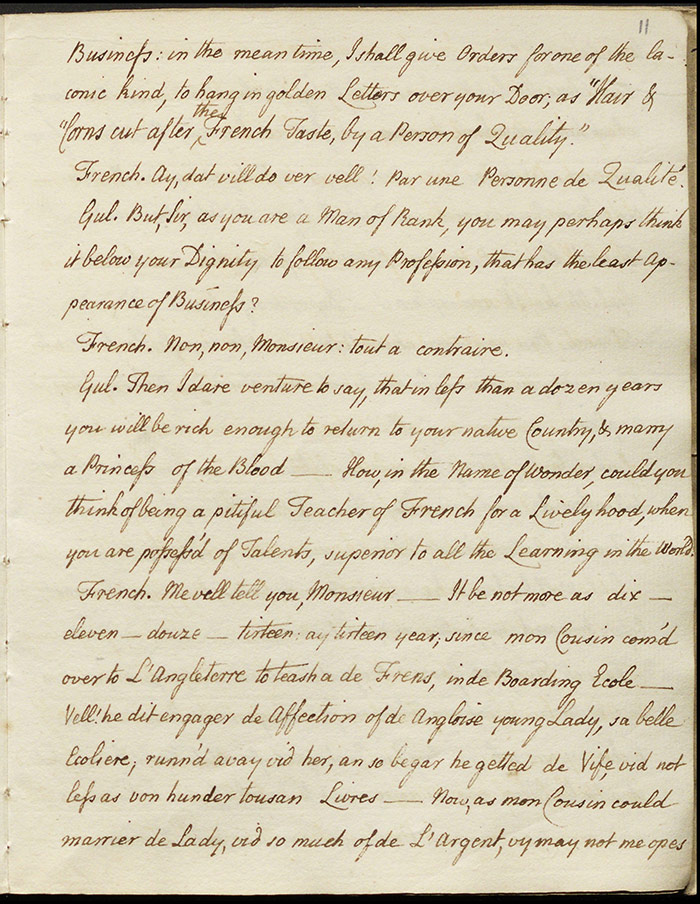

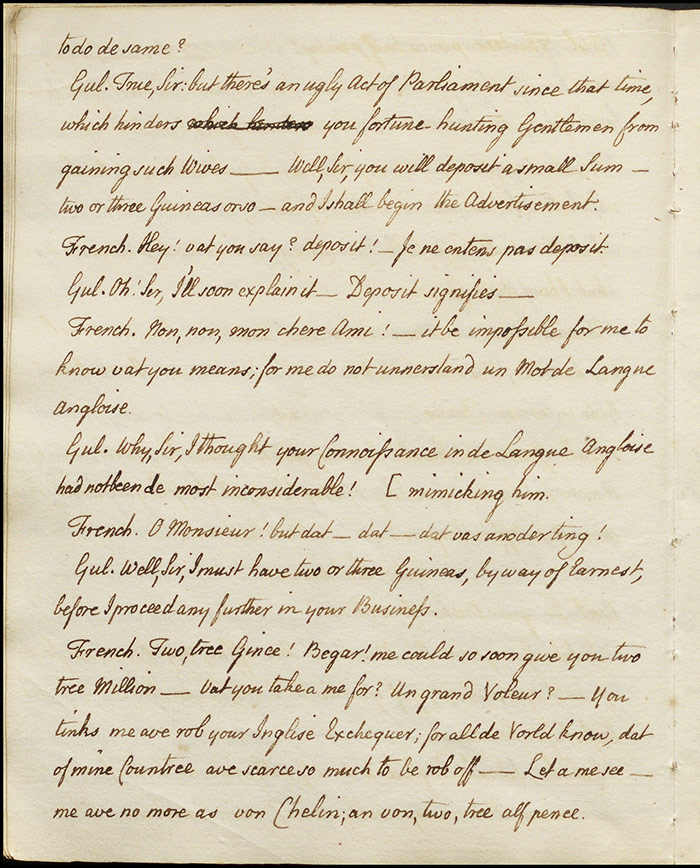

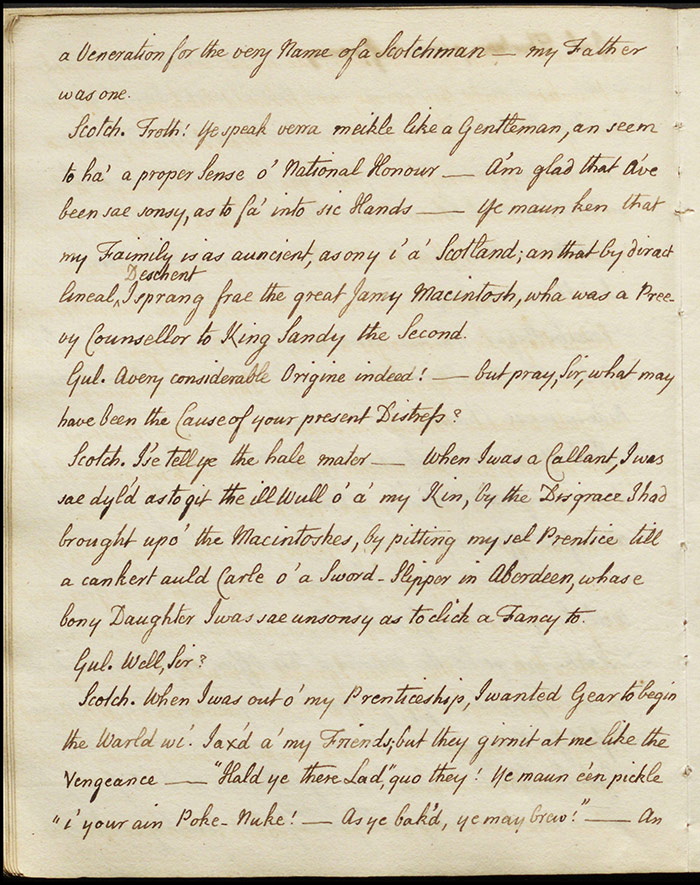

Exit O’Carroll and enter Lady Manlove, a regular customer. She had to let the last employee she recruited from the office go as he had the audacity ‘to offer Love to me in an honourable way!’ (f.8v). Now she is looking for Gulwell to supply her with a man servant who is ‘well built […] very little less than six foot’ who will need ‘a very healthy Constitution’ to deal with the ‘Drudgery in the Management of my Affairs’ (f.9r). She is happy for the last advertisement to run again despite the heavy double entendres contained in it. Exit Lady Manlove and enter a Frenchman. He is looking to be a French language teacher in an academy but his affectations disguise less genteel skills and Gulwell agrees to place an advertisement for him as a hairdresser and corn-cutter.

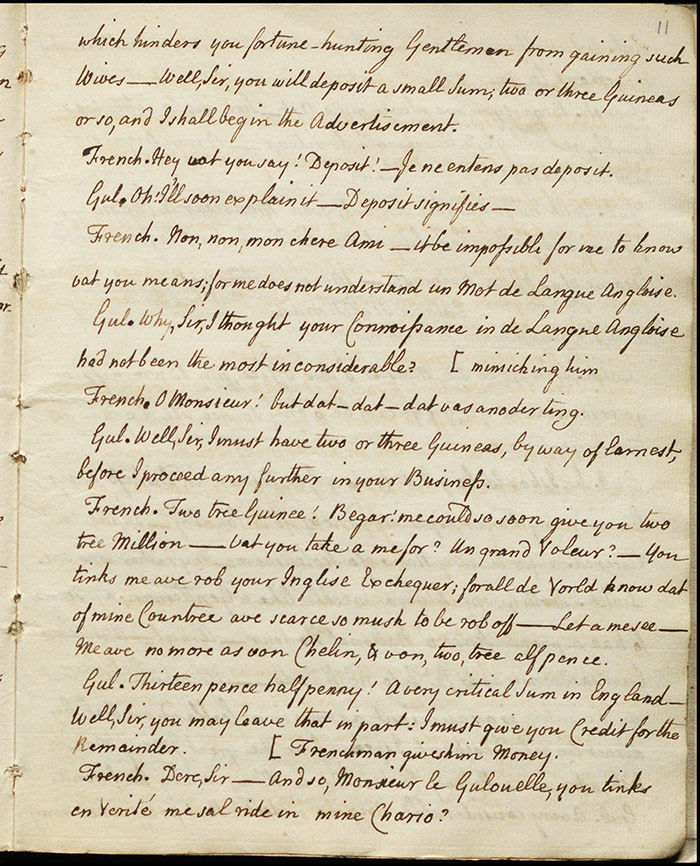

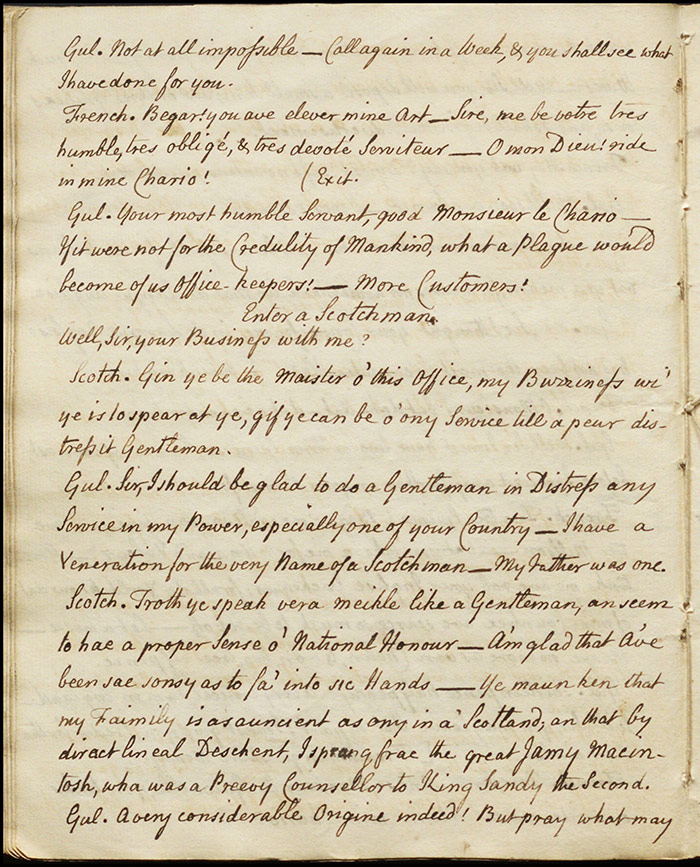

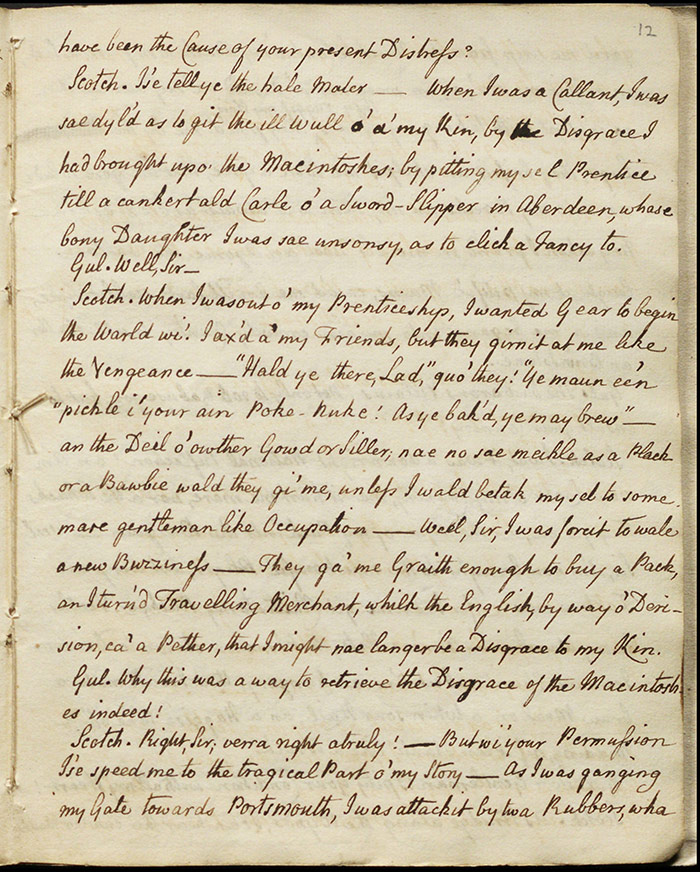

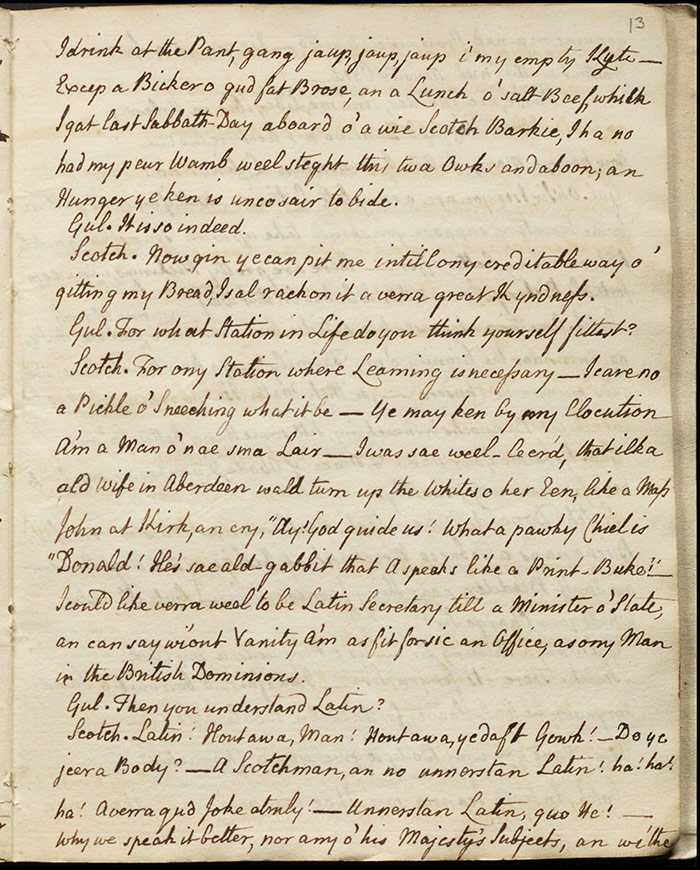

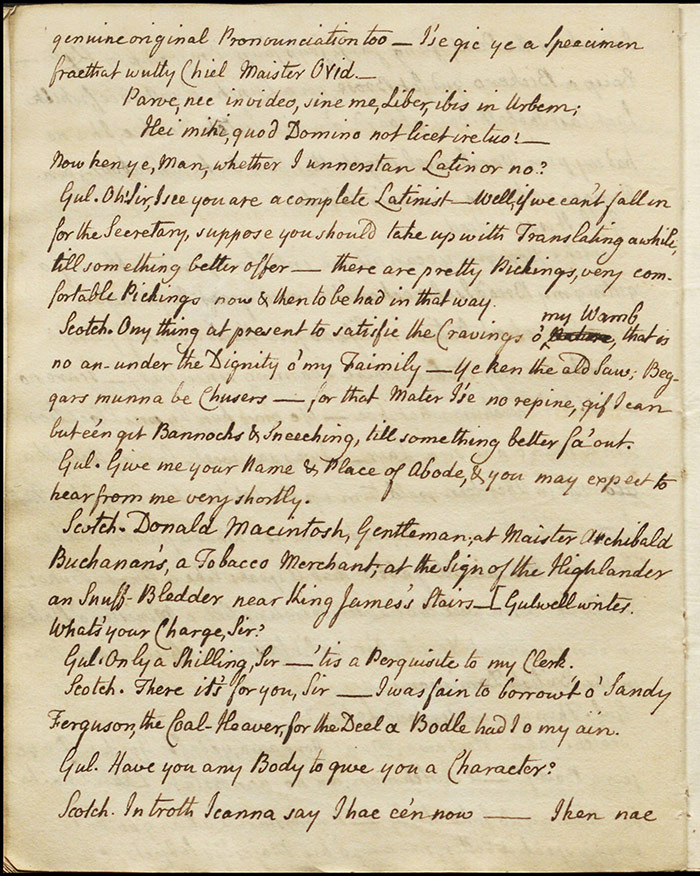

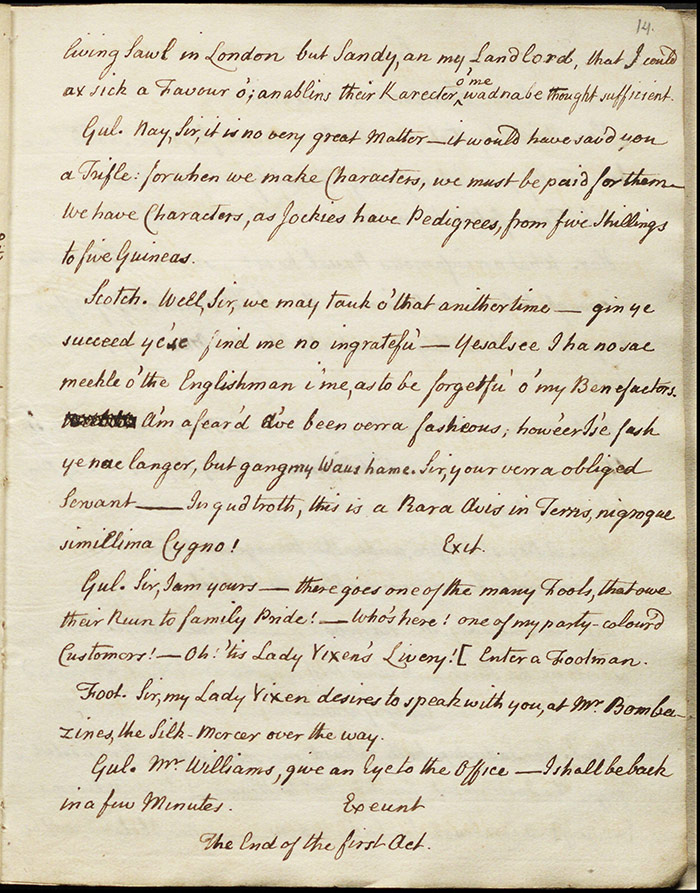

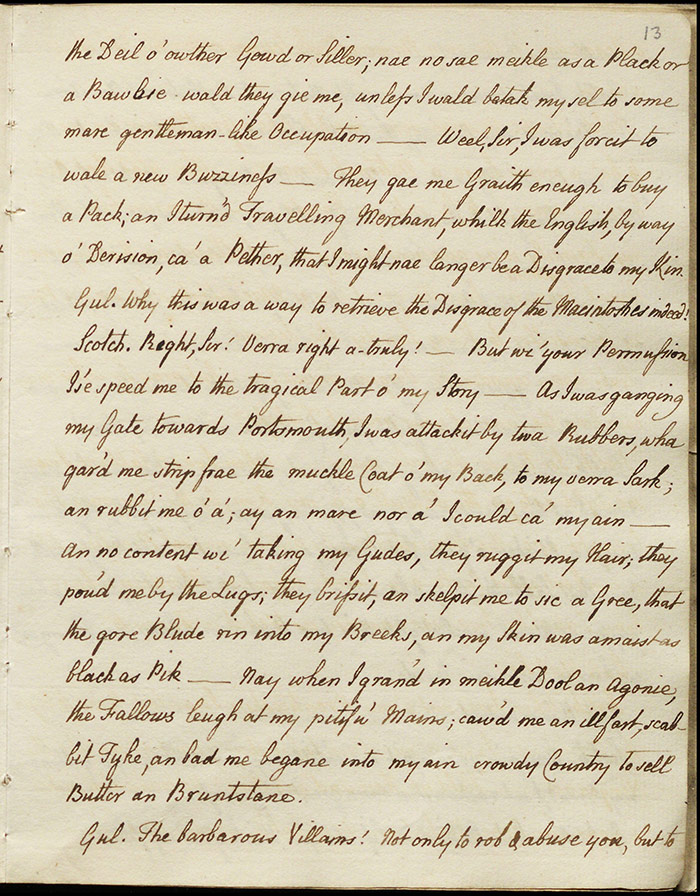

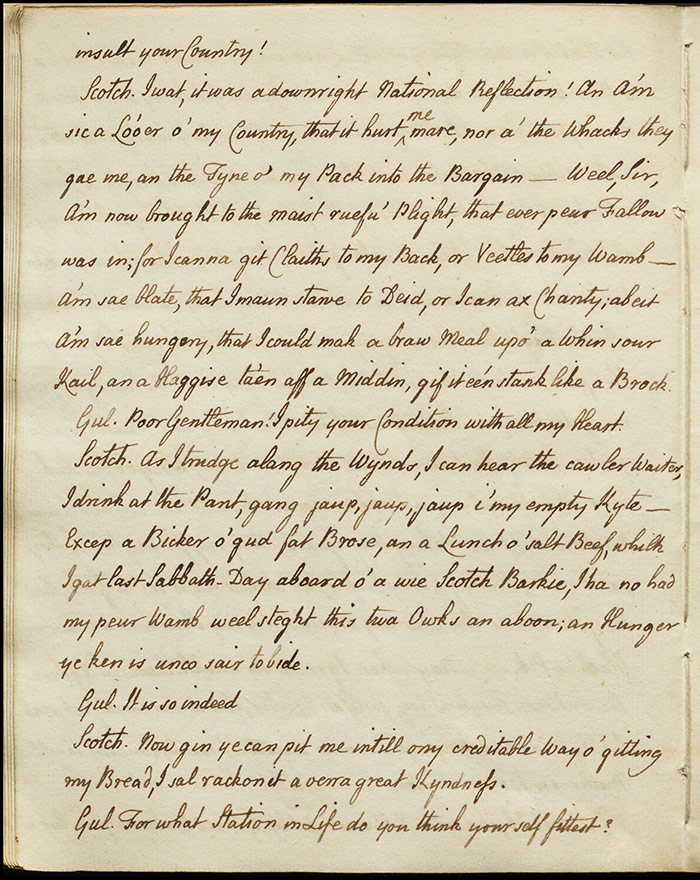

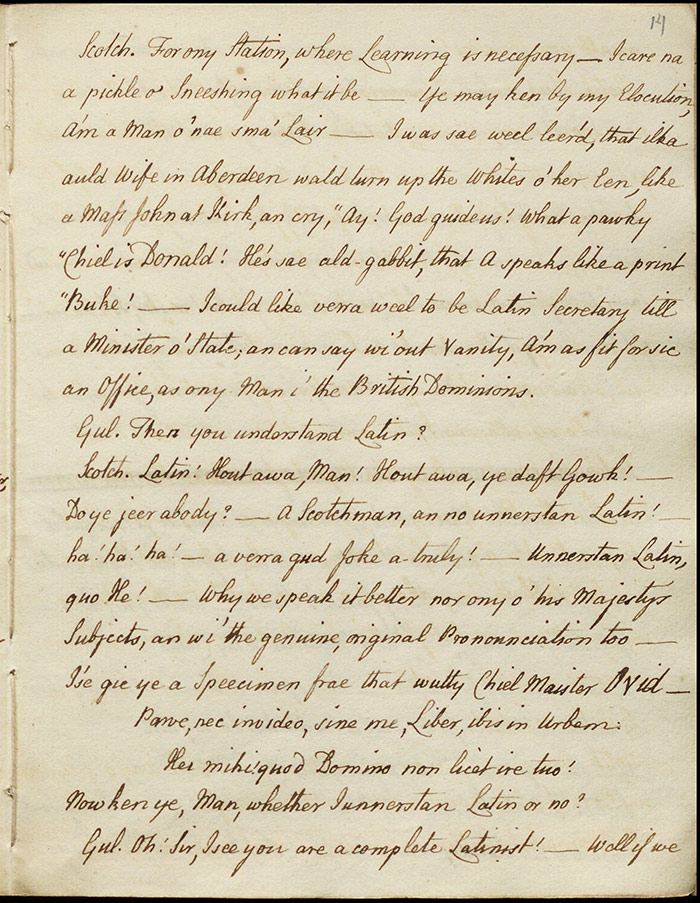

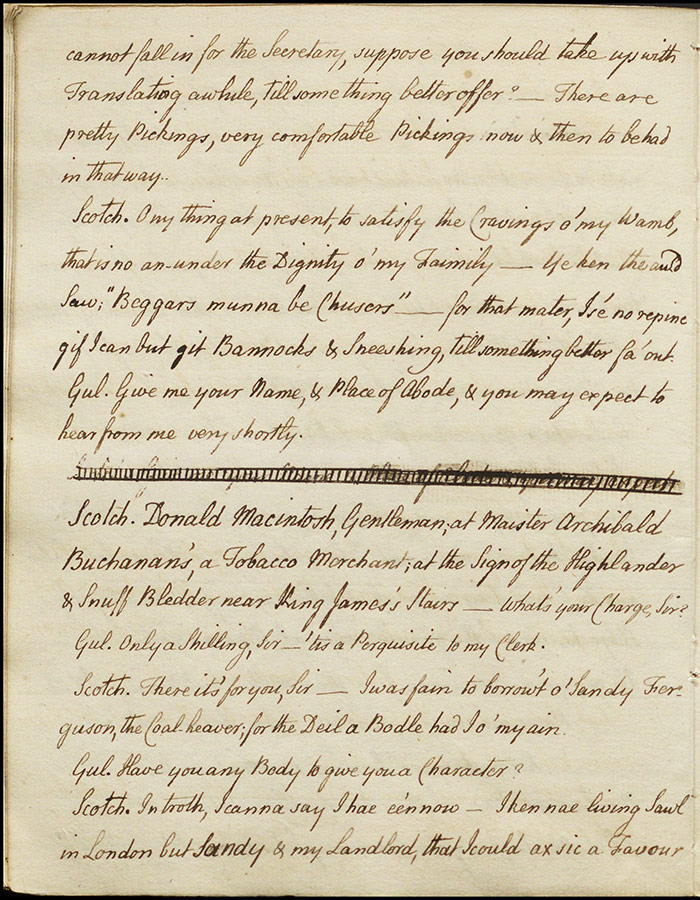

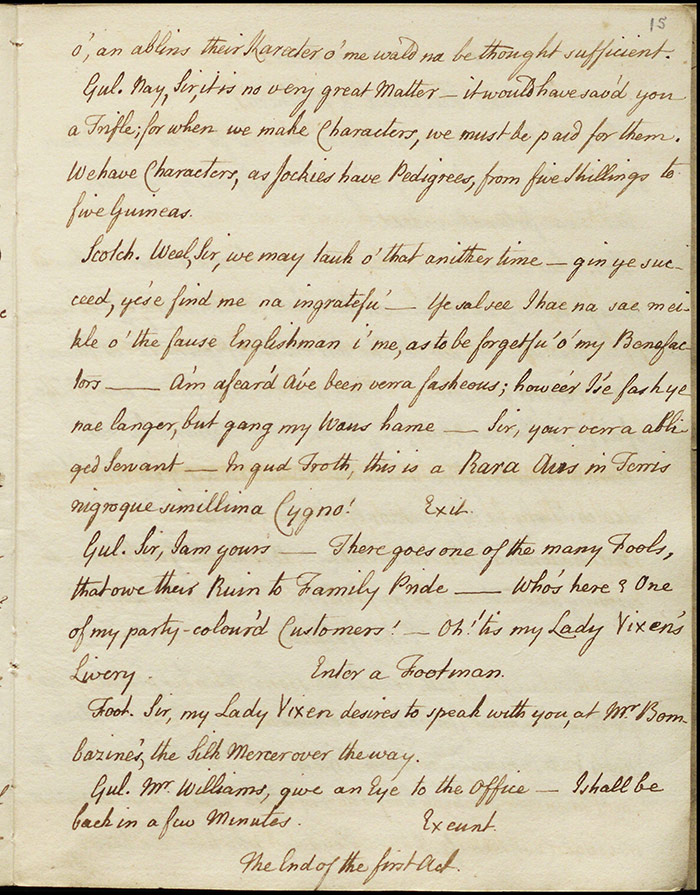

Exit Frenchman and enter Scotchman, Donald Macintosh. He recounts a tale of hardship including his being attacked and robbed on his way to Portsmouth. He claims to be proficient in Latin (his recital of Latin, like the Irishman’s lines, is firmly intended to provoke ethnic-based laughs) and Gulwell says that he will look for a place as a translator. However, Macintosh has no one to vouch for him but Gulwell reassures him ‘we have Characters, as Jockies have Pedigrees, from five Shillings to five Guineas’ (f.14r). Exit Scotchman and enter Lady Vixen’s footman who summons Gulwell to see her. Exeunt.

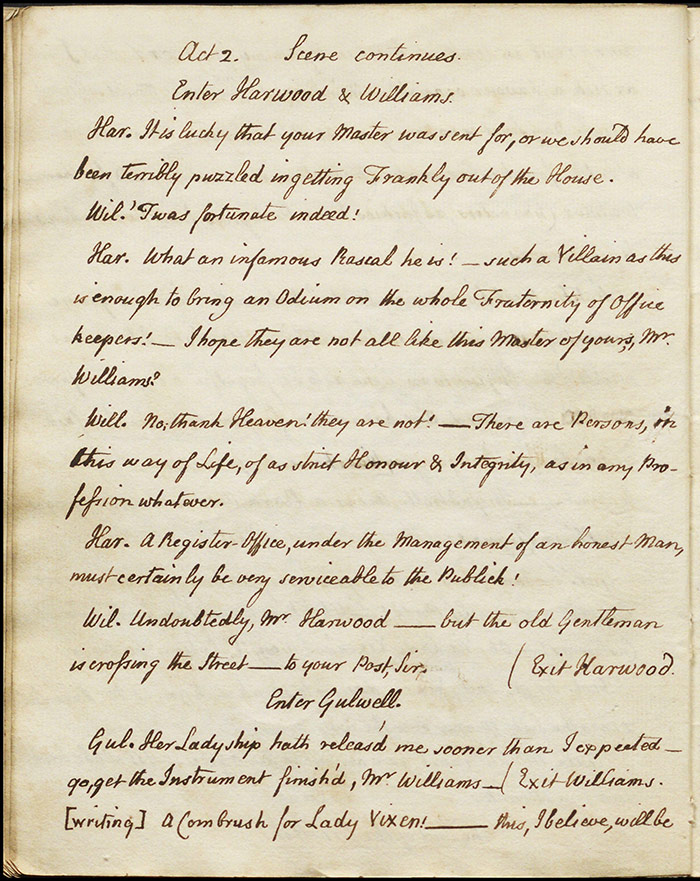

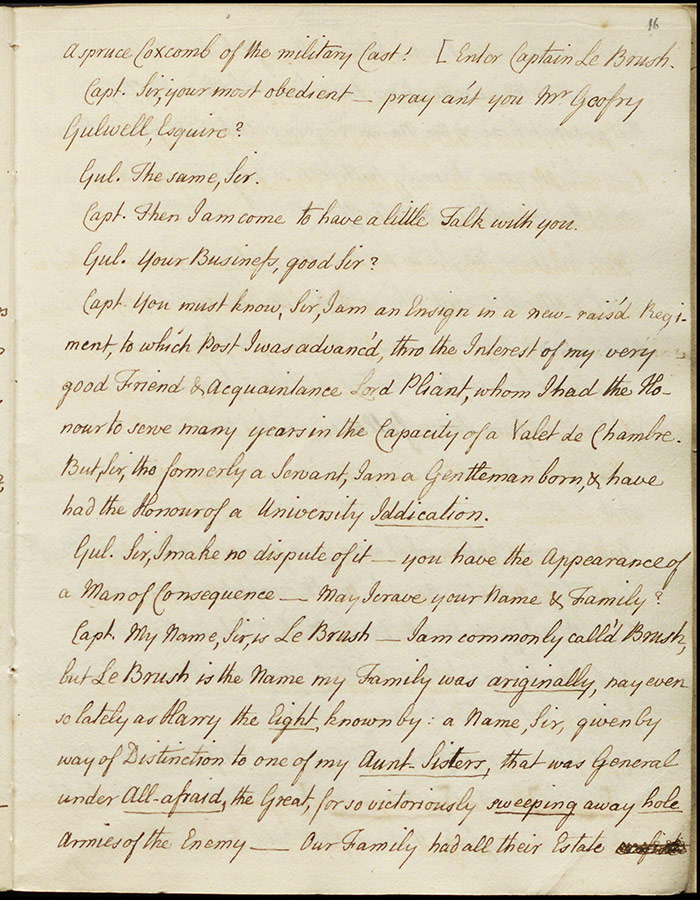

[Act 2; f.14v]

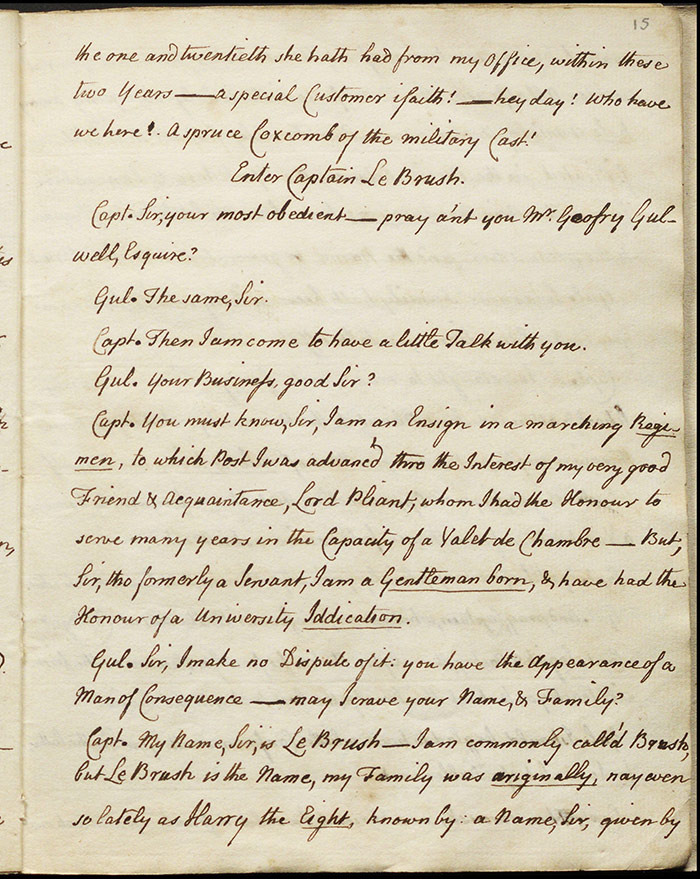

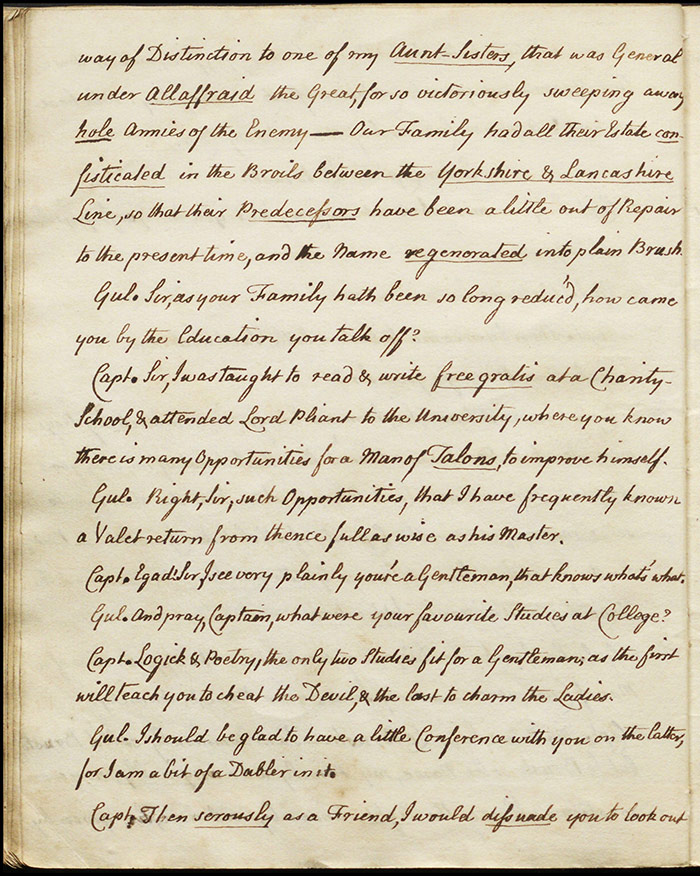

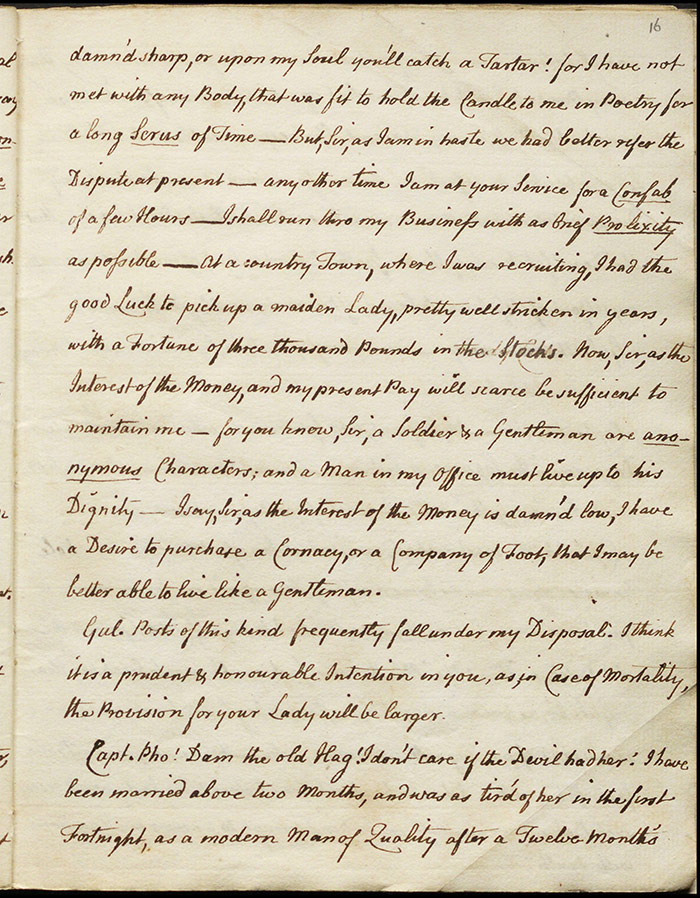

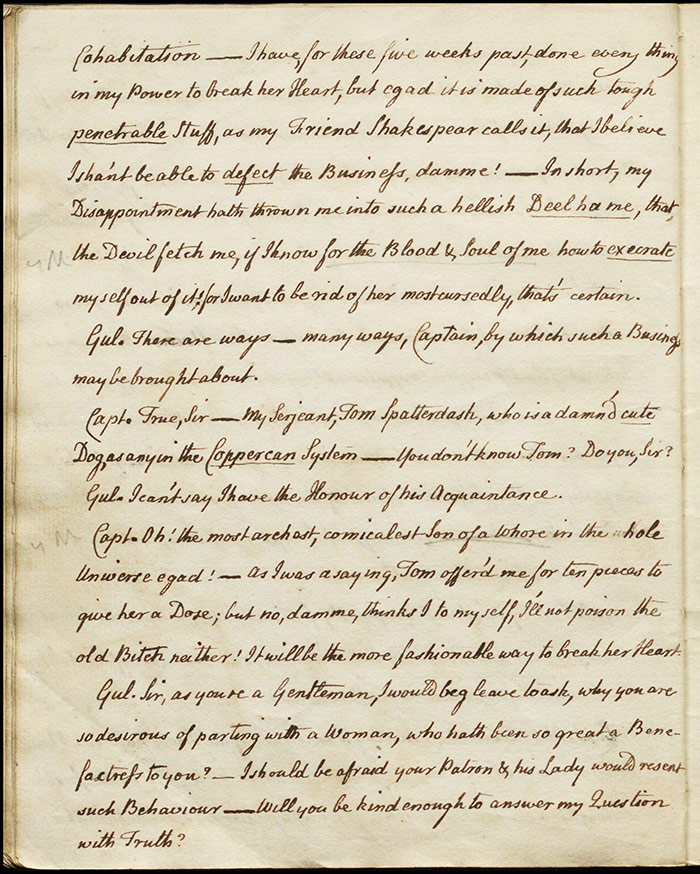

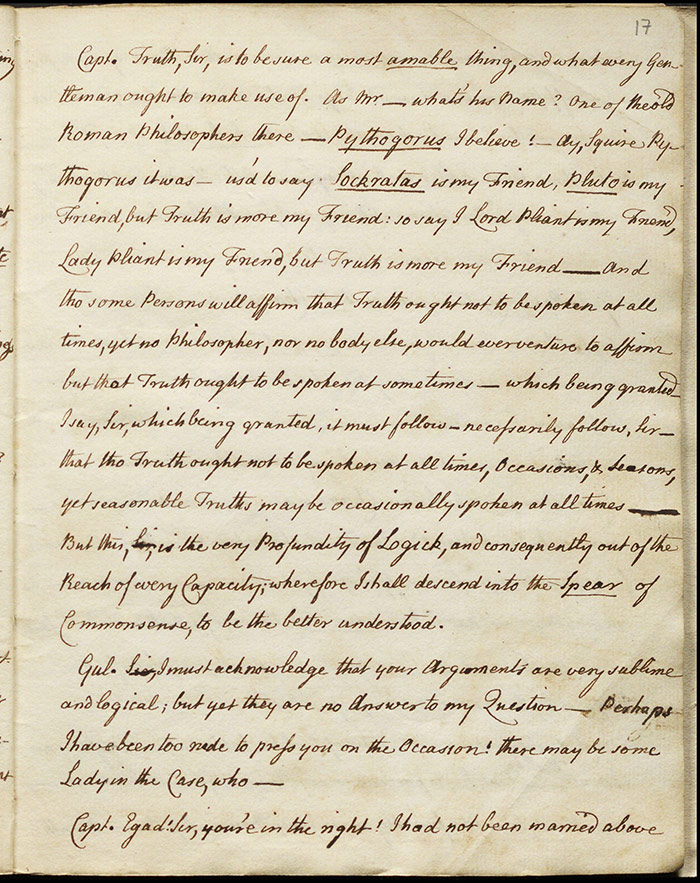

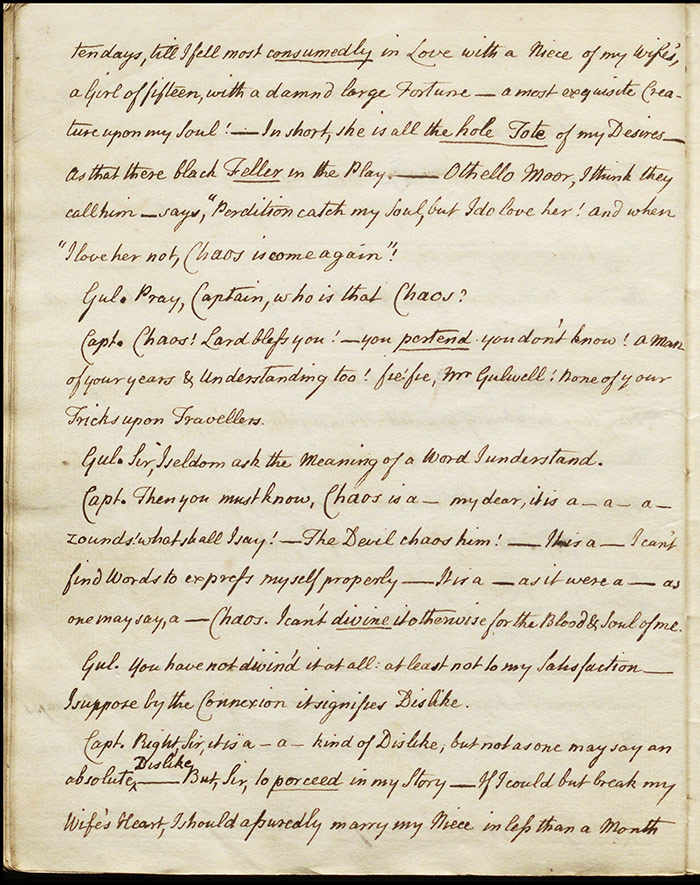

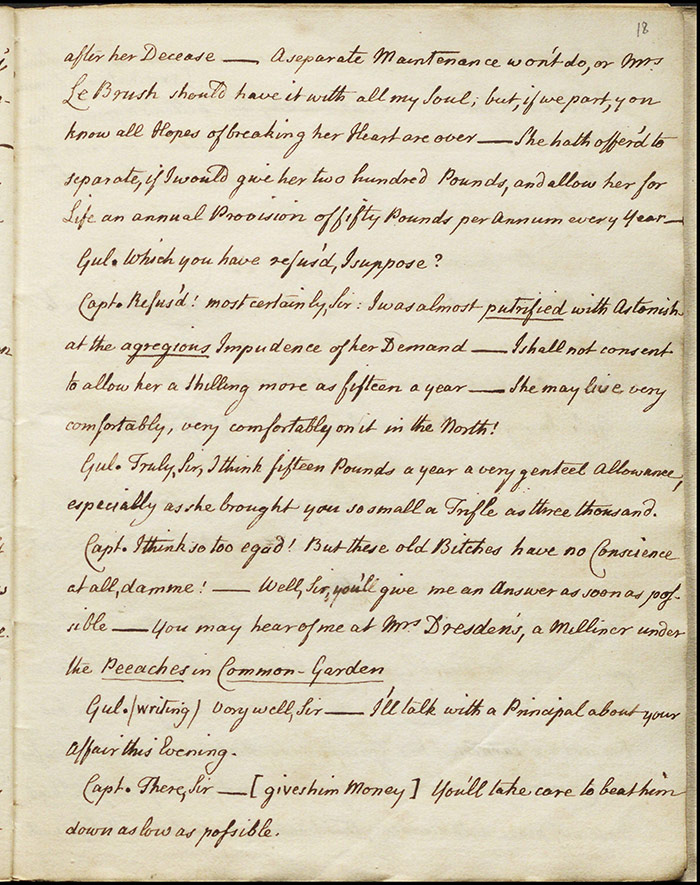

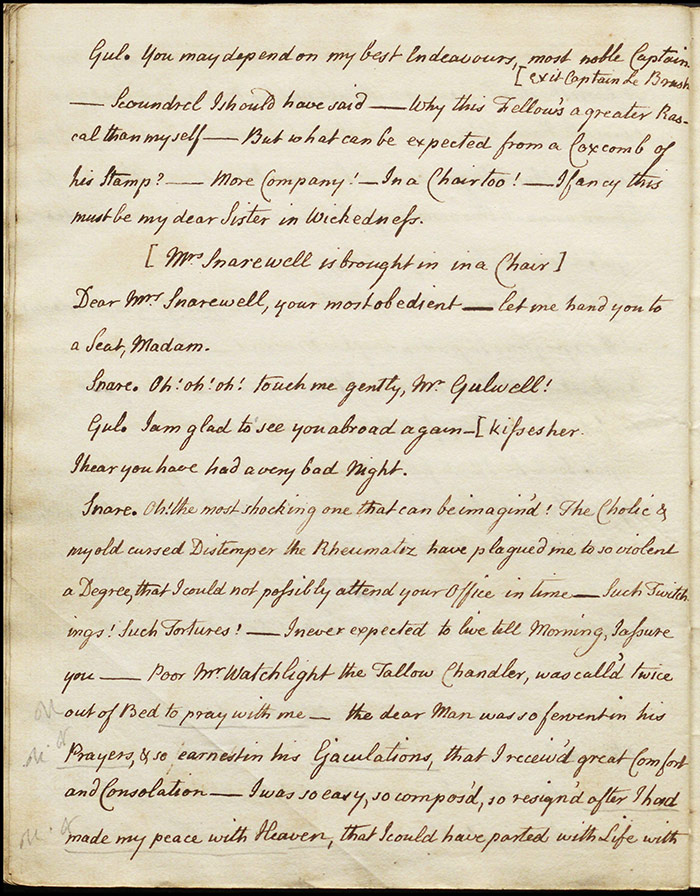

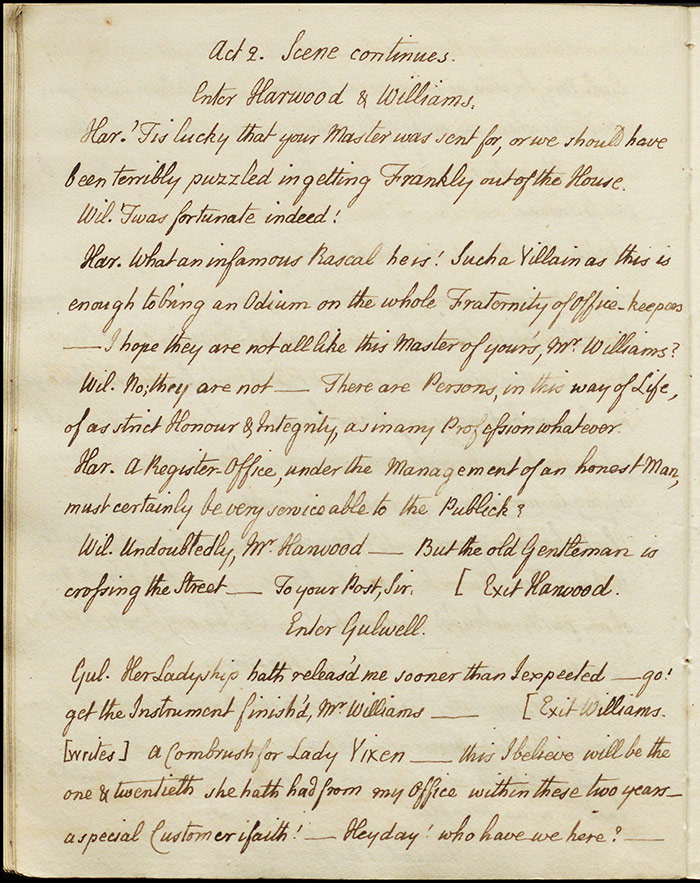

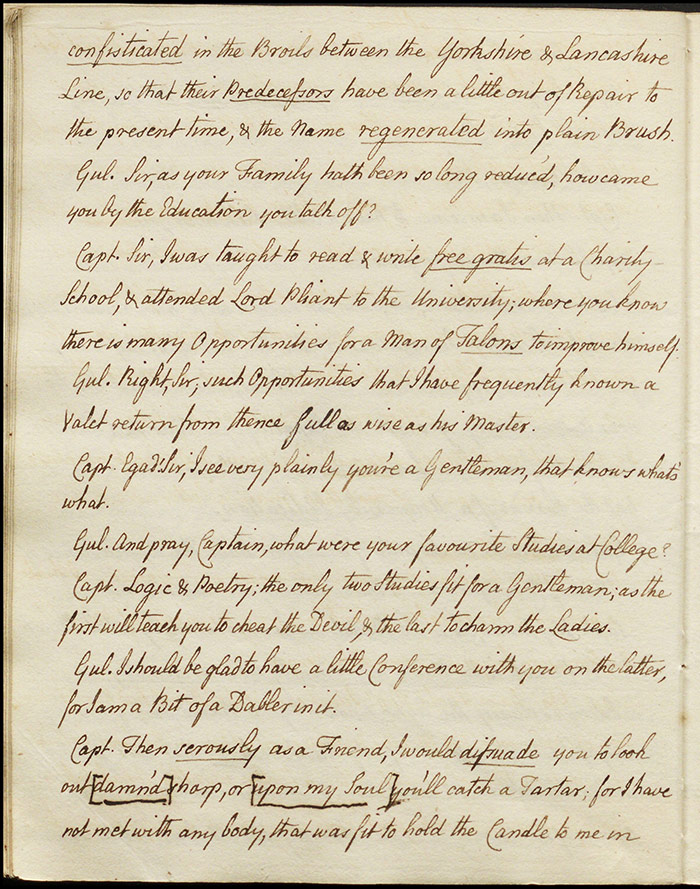

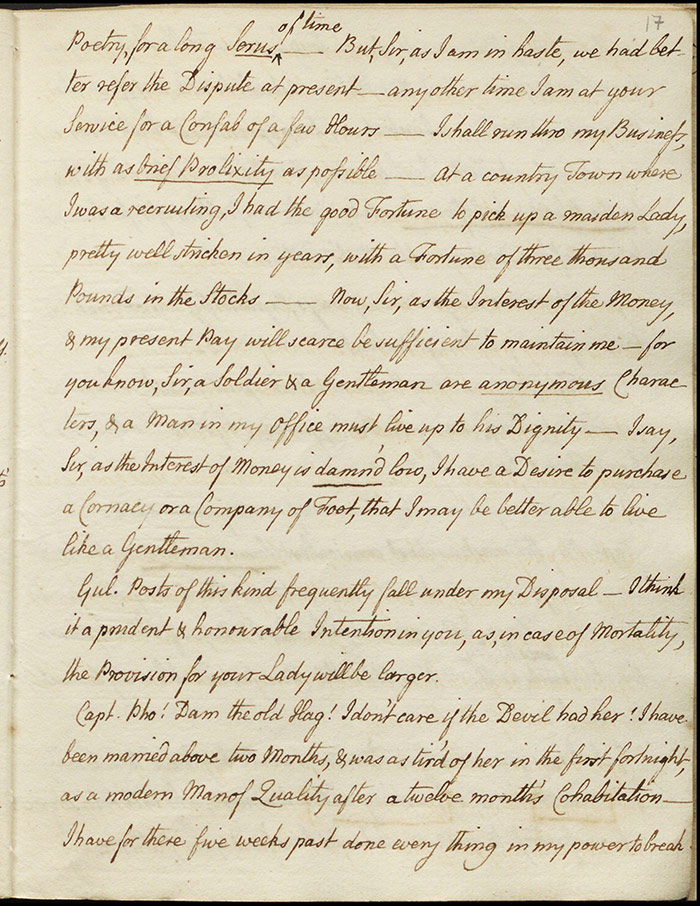

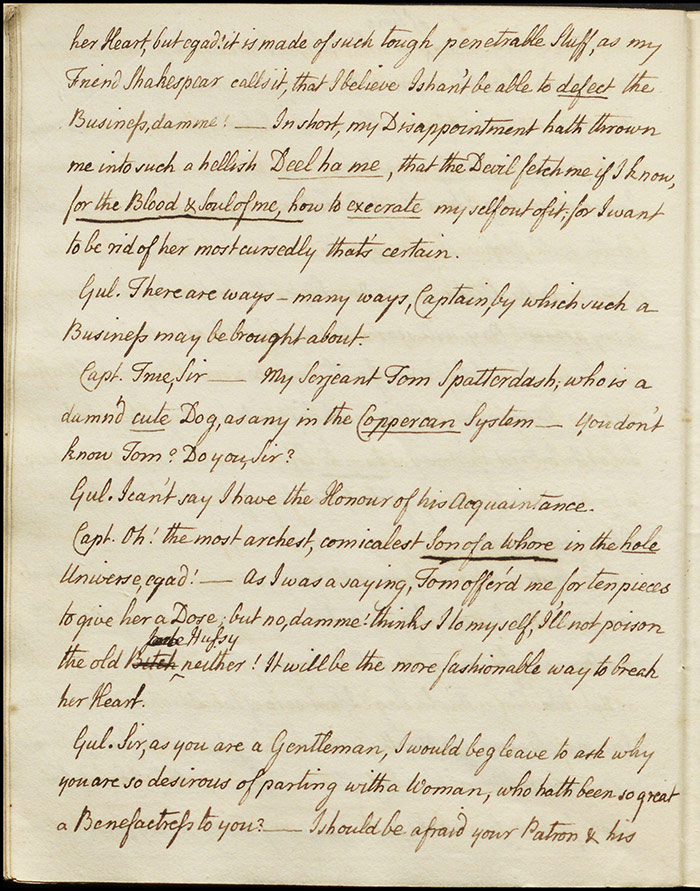

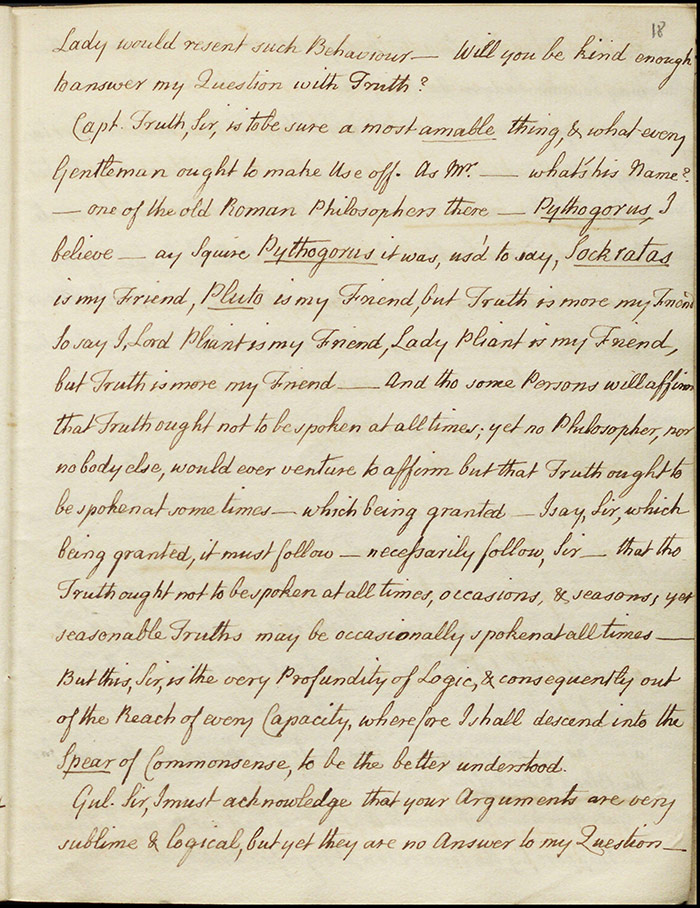

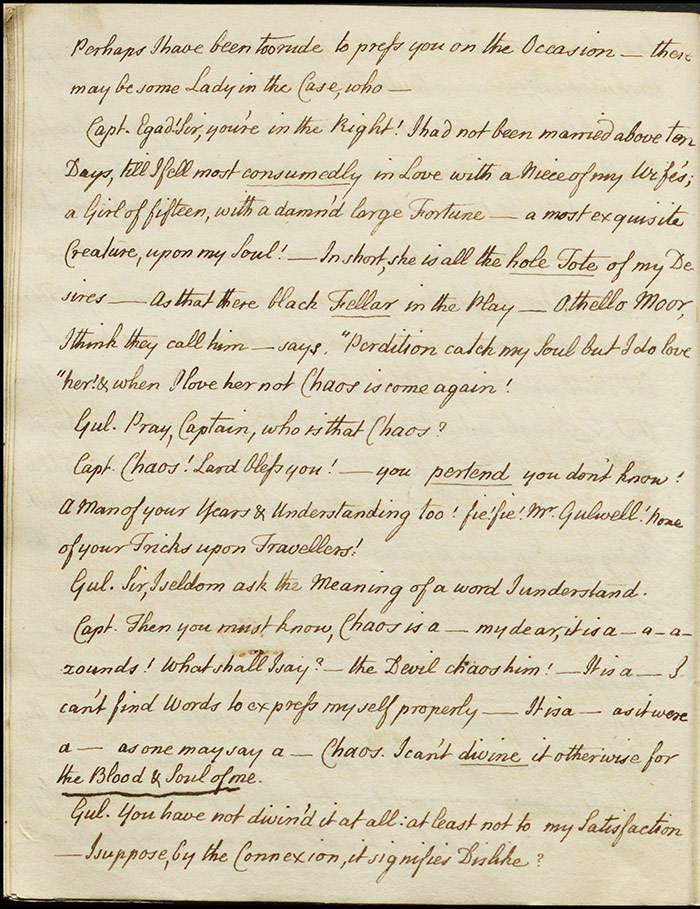

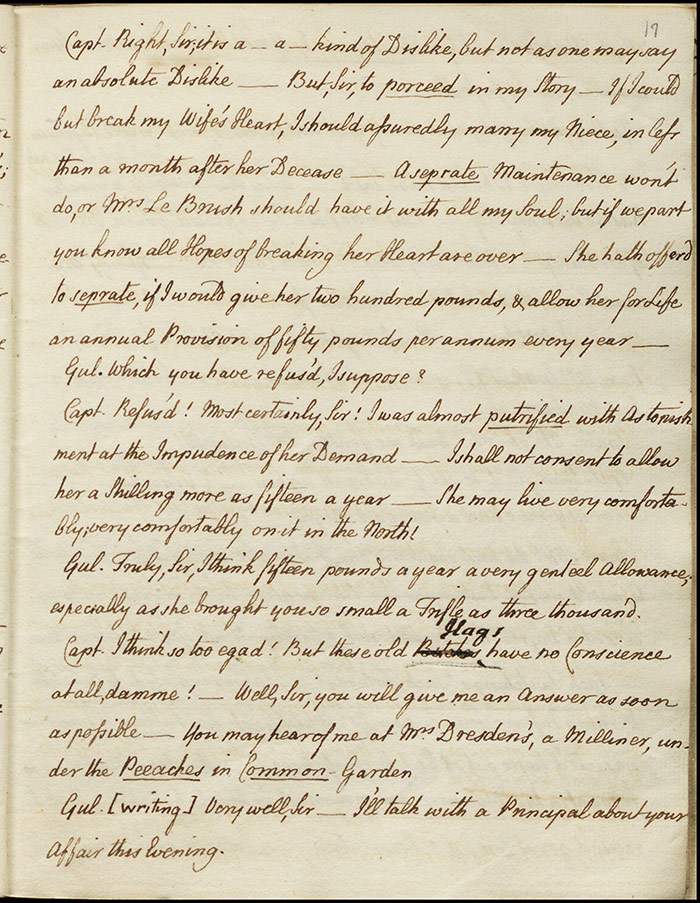

Harwood decrys Gulwell’s villainy but Harwood reassures him that not all register offices are like this and that many operate with honesty and integrity. Williams spots Gulwell returning and Harwood exits. Enter Gulwell who celebrates Lady Vixen’s demand for another comb-brush (a lady’s maid) – her twenty-first such request in two years. Enter Captain Le Brush, a military coxcomb. His grandiose and self-regarding manner is undercut by his flawed pronunciation and the many malapropisms in his speech. He has recently married a woman with £3000 a year but the interest is not enough to sustain him so he wishes to purchase ‘a Cornacy, or a Company of Foot, that I may be better able to live like a Gentleman’ (f.16r). He also wants rid of his wife—preferably to kill her by breaking her heart rather than by poison—in order to marry her prettier and wealthier niece. Although his wife as offered to separate for an annual allowance of £50 per annum, Le Brush professes himself astonished at her impudence ‘But these old Bitches have no Conscience at all, damme!’ (f.18r).

Gulwell promises to make enquiries on his behalf and Le Brush exits.

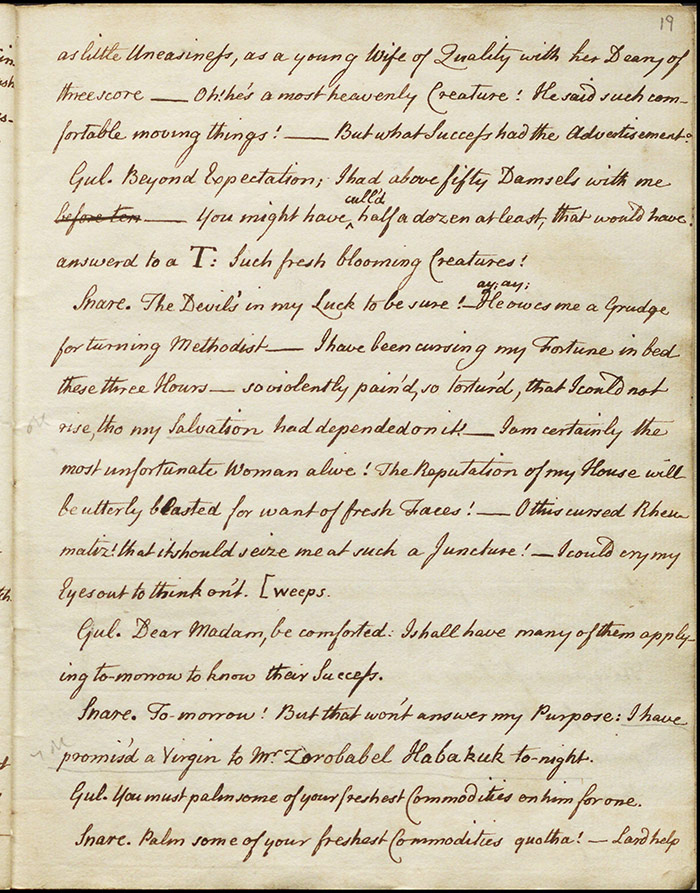

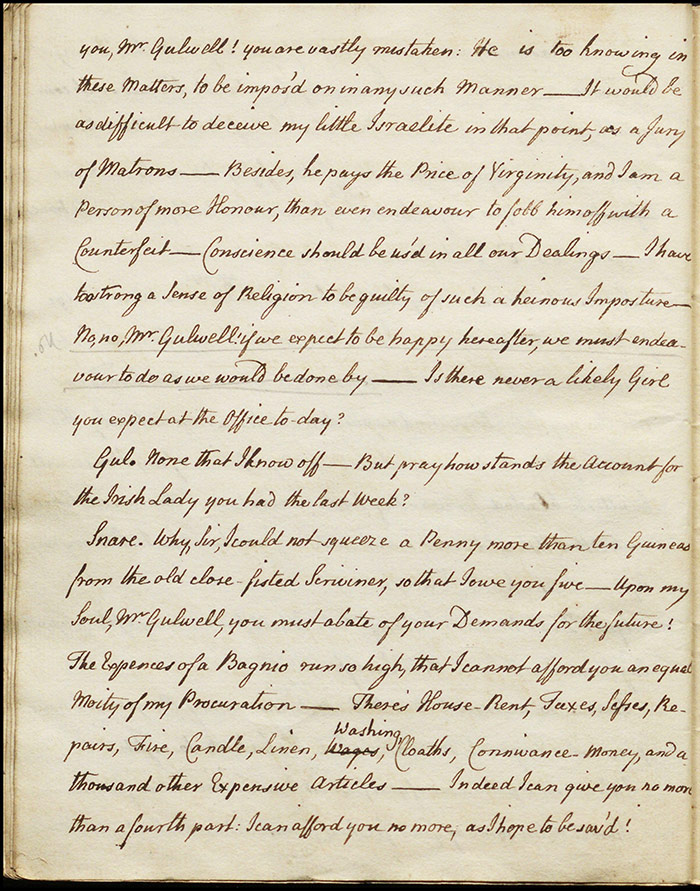

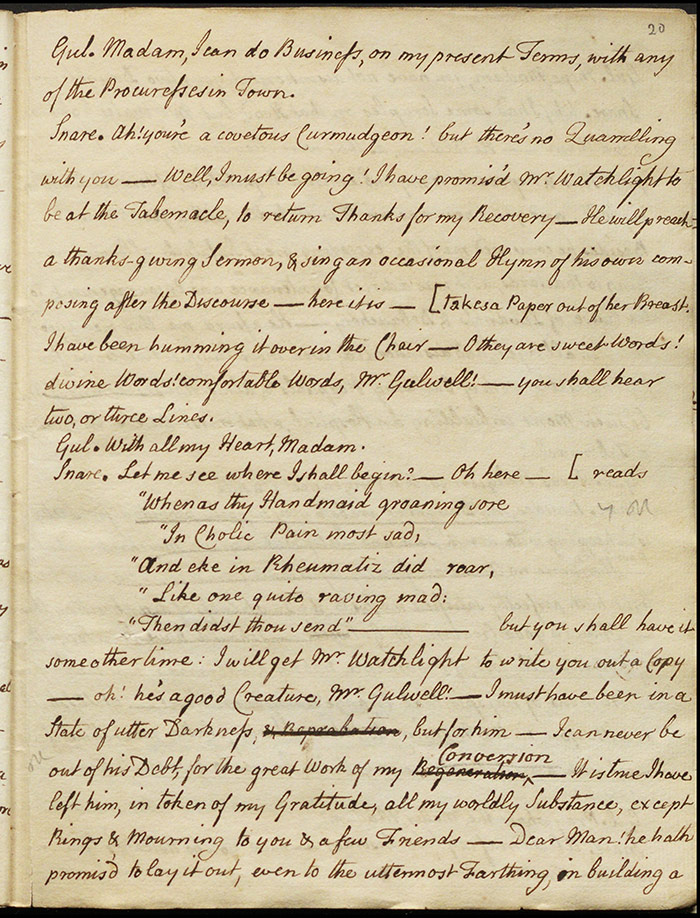

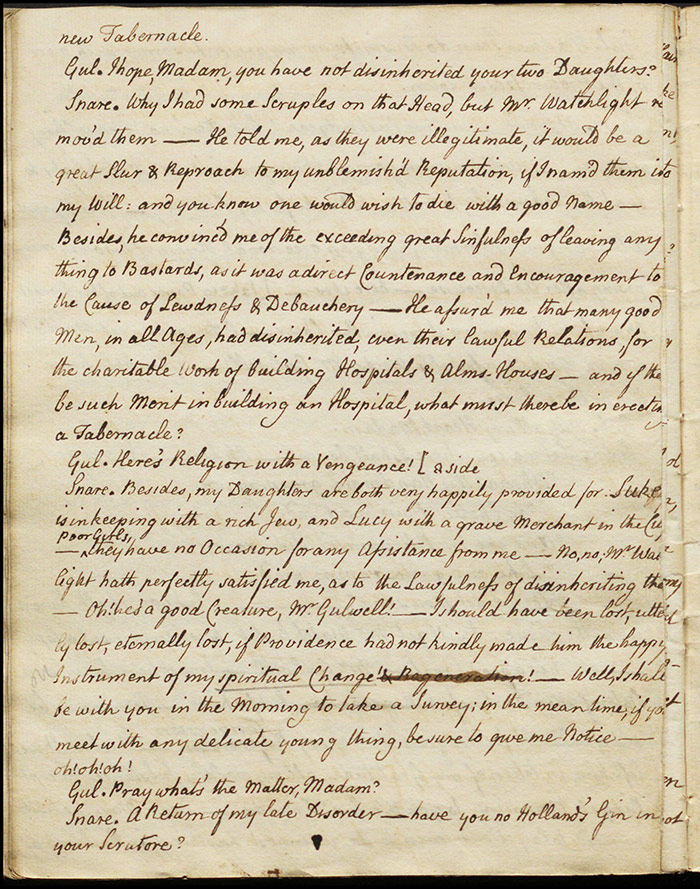

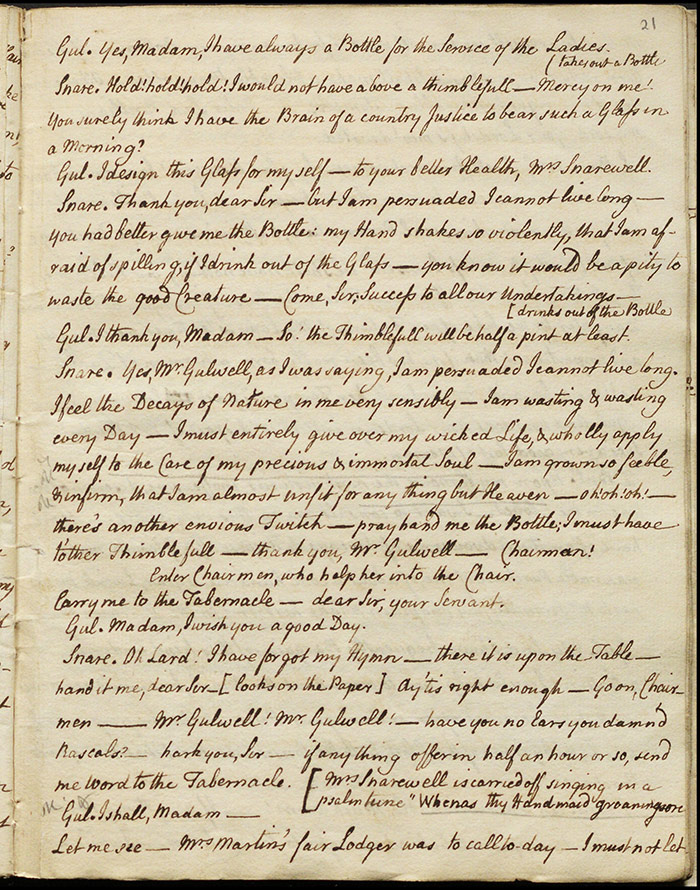

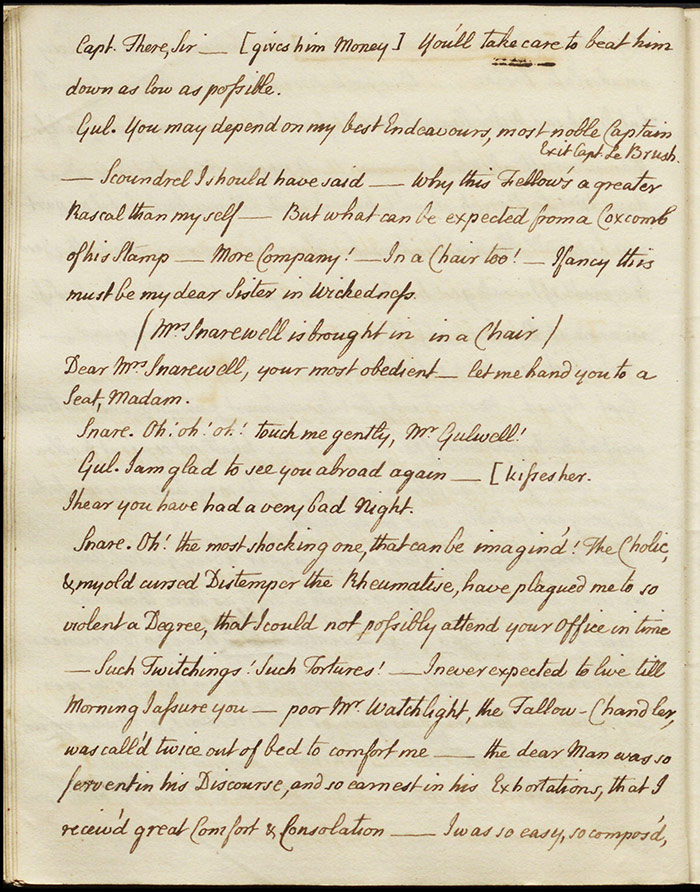

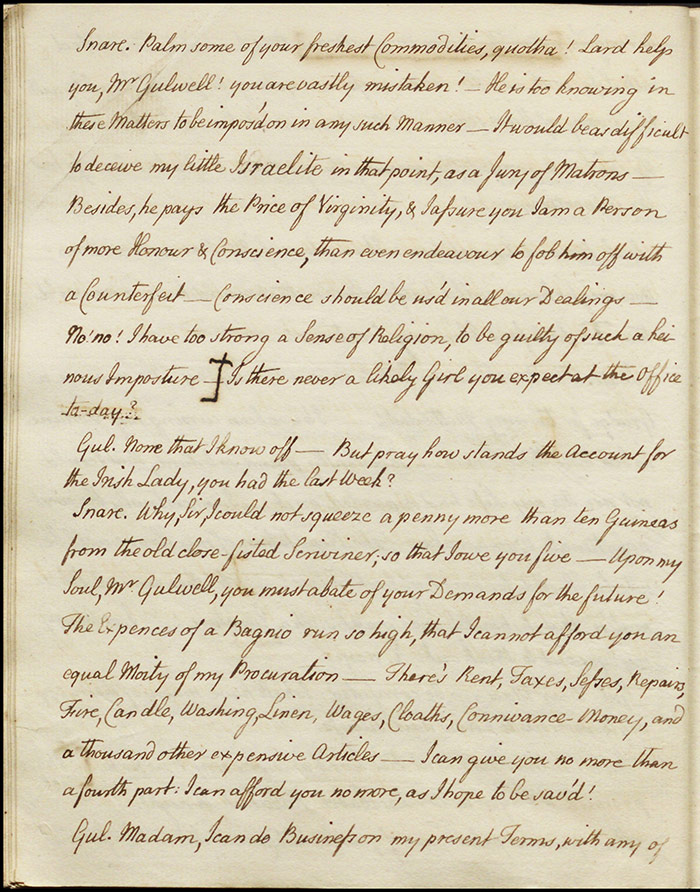

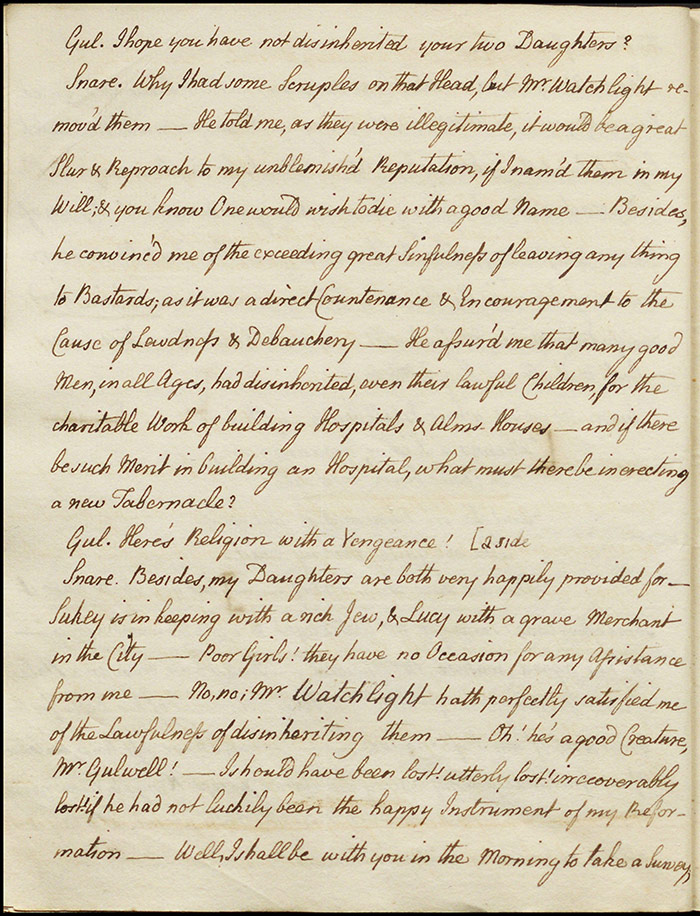

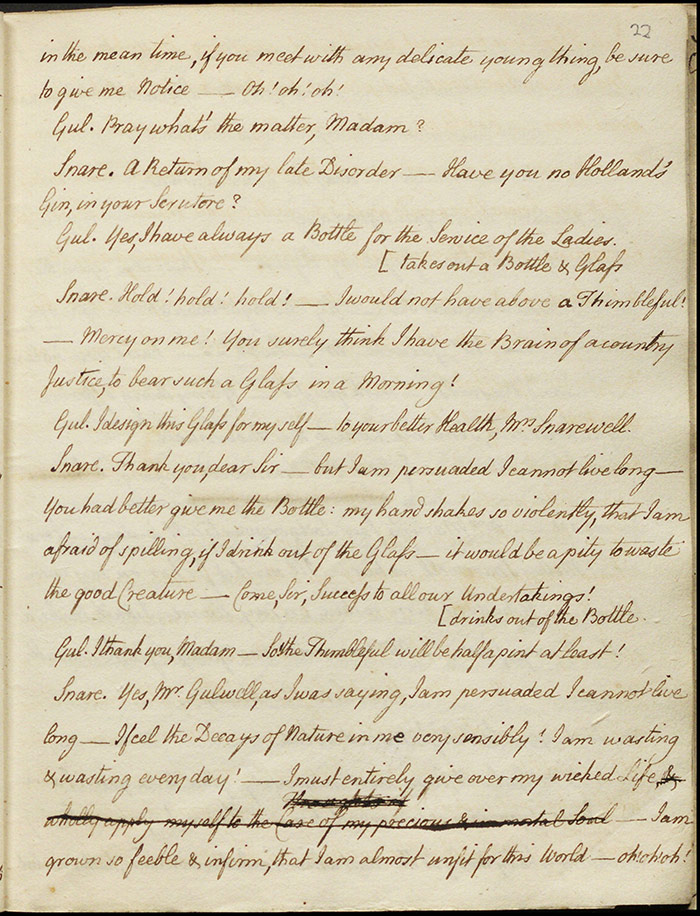

Enter Mrs Snarewell, an old bawd and Gulwell’s ‘dear sister in Wickedness’ (f.18v). She complains of a myriad of health problems and a terrible night’s sleep until the kind attentions of Mr Watchlight the Tallow Chandler, ‘so earnest in his Ejaculations’, eased her (f.18v). She is so enamoured of Watchlight that she has disinherited her two illegitimate daughters on his advice (to avoid the shame of naming them in her will) and committed her wealth to him. He has claimed that he will build a new tabernacle with the money. She is in need of new prostitutes for her brothel and, in particular, is desperately in need of a genuine virgin for a discerning and wealthy Jewish client for that evening. Before leaving, she asks him to keep an eye out for a likely young woman and drinks copious amounts of his gin.

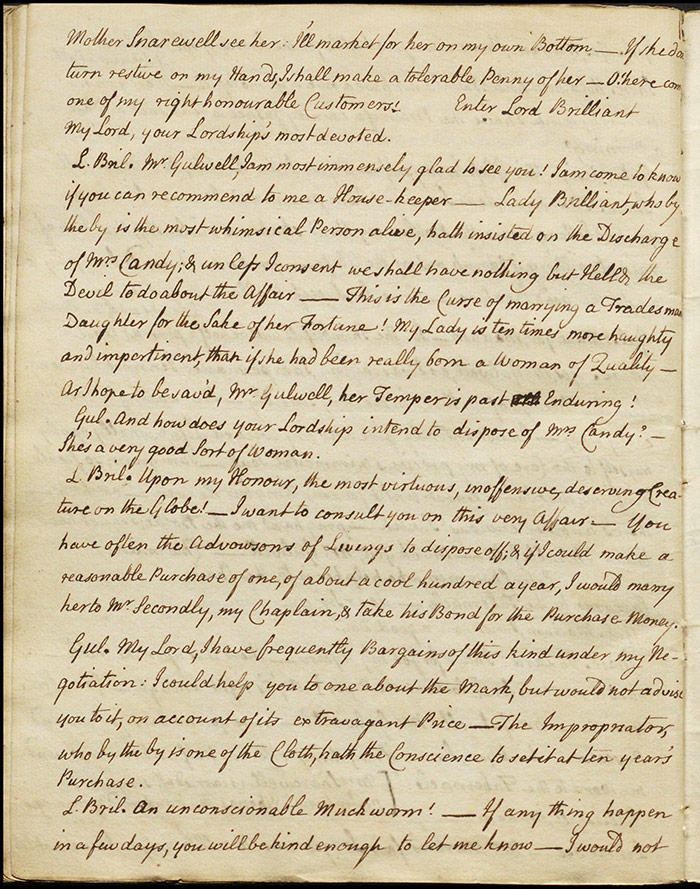

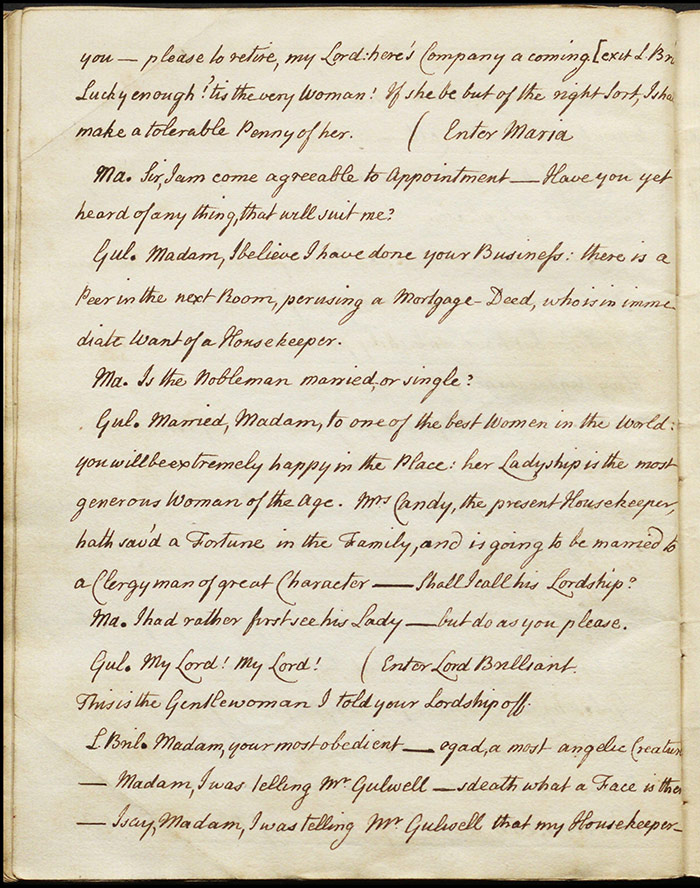

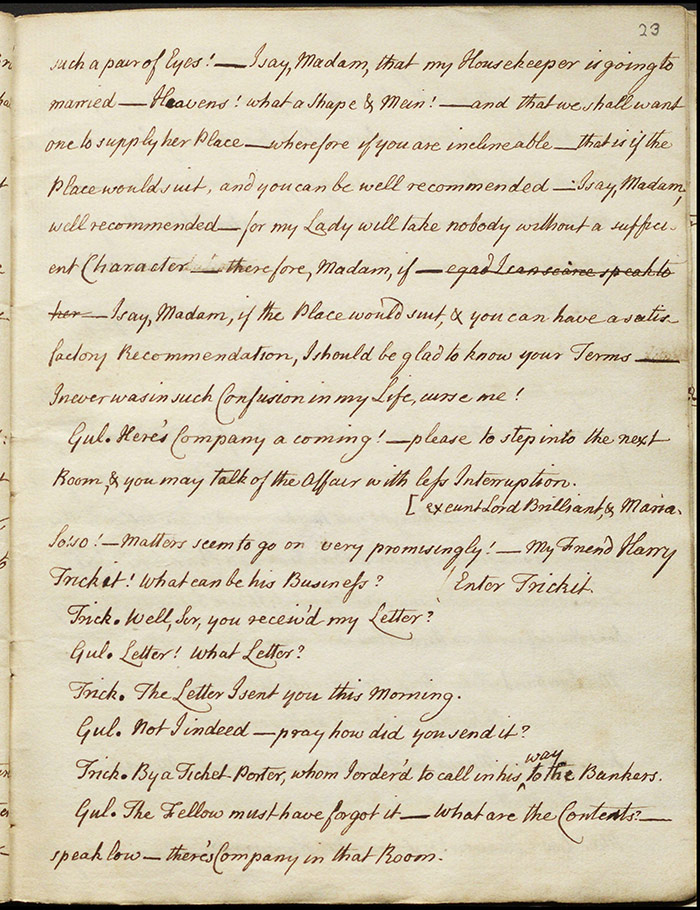

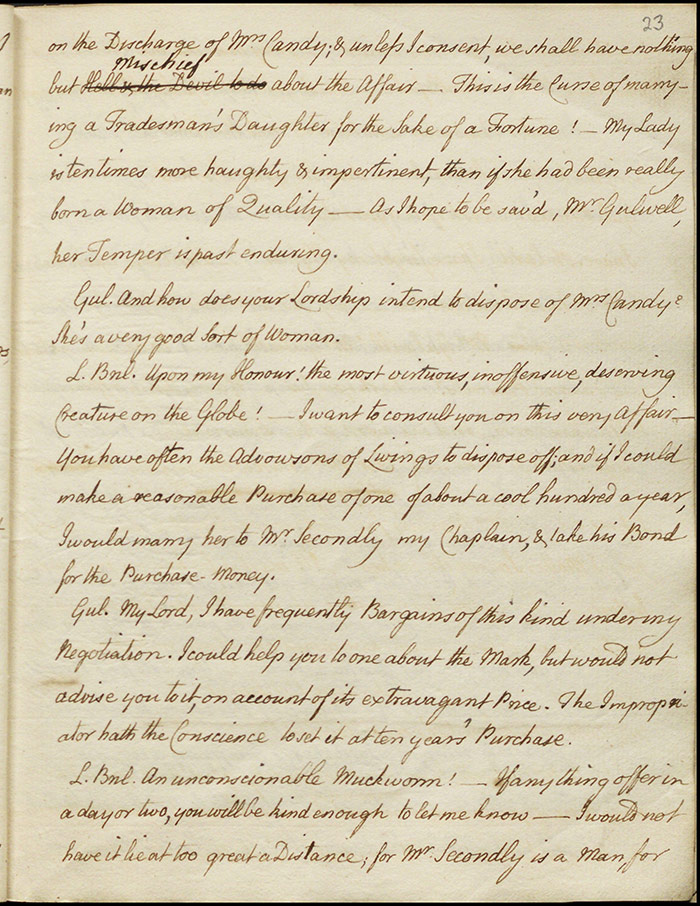

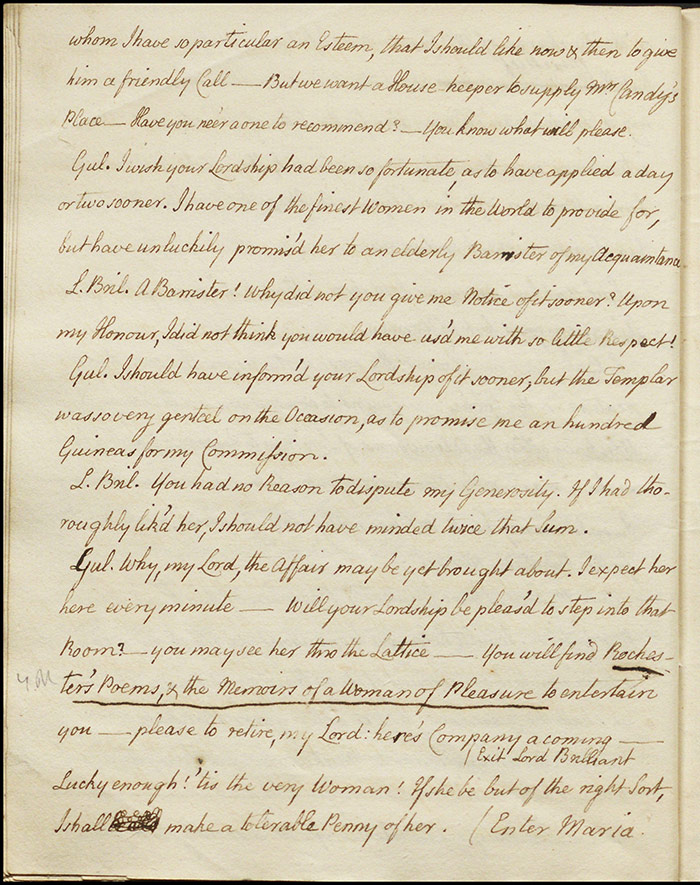

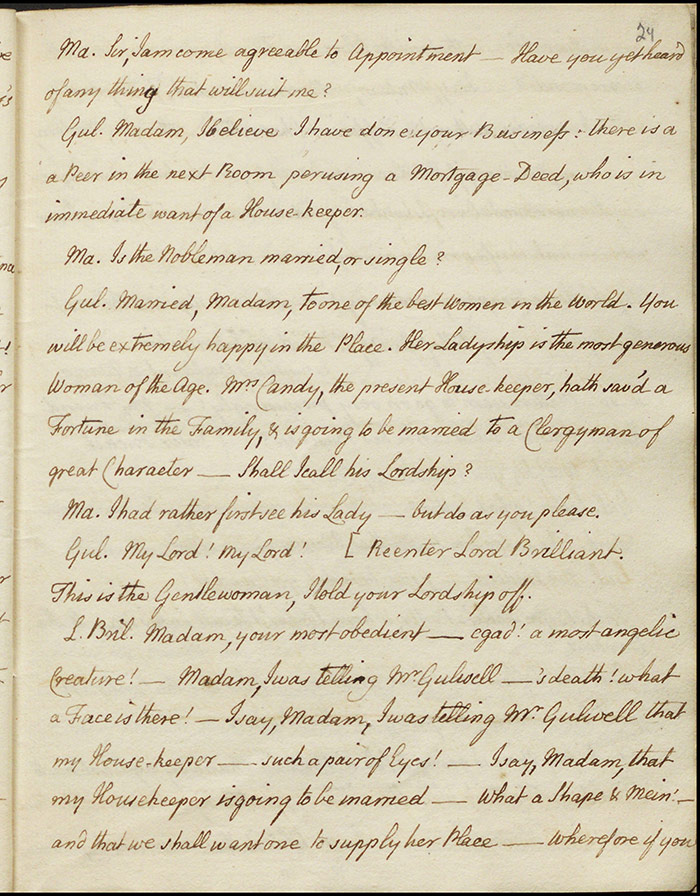

Exit Mrs Snarewell and enter Lord Brilliant. He is in need of a new housekeeper, ostensibly because his wife is ‘whimsical’ and wants rid of Mrs Candy but as he wants to marry Mrs Candy off to his chaplain so that he can ‘now and then to give him a friendly call’, we might suspect an ulterior motive (f.22r). Gulwell tells him to hide in the back as he has a lady coming who might fit the bill and Lord Brilliant will be able to inspect her himself. Exit Lord Brilliant and enter Maria. Gulwell tells her he has found her an ideal position as a housekeeper and calls Lord Brilliant. He is lascivious in his approach to her and then Gulwell asks them to step into the next room as more company approaches.

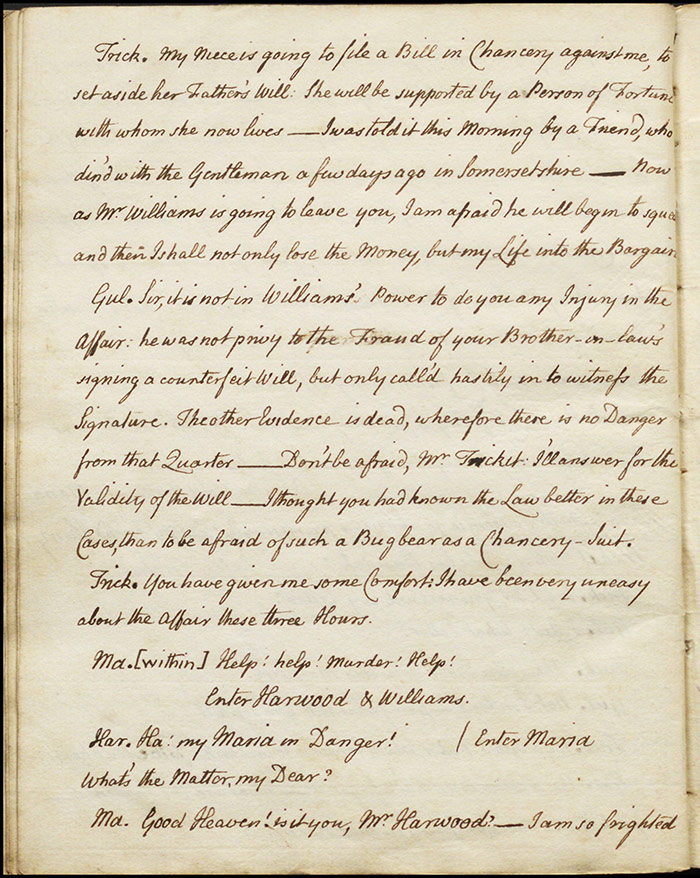

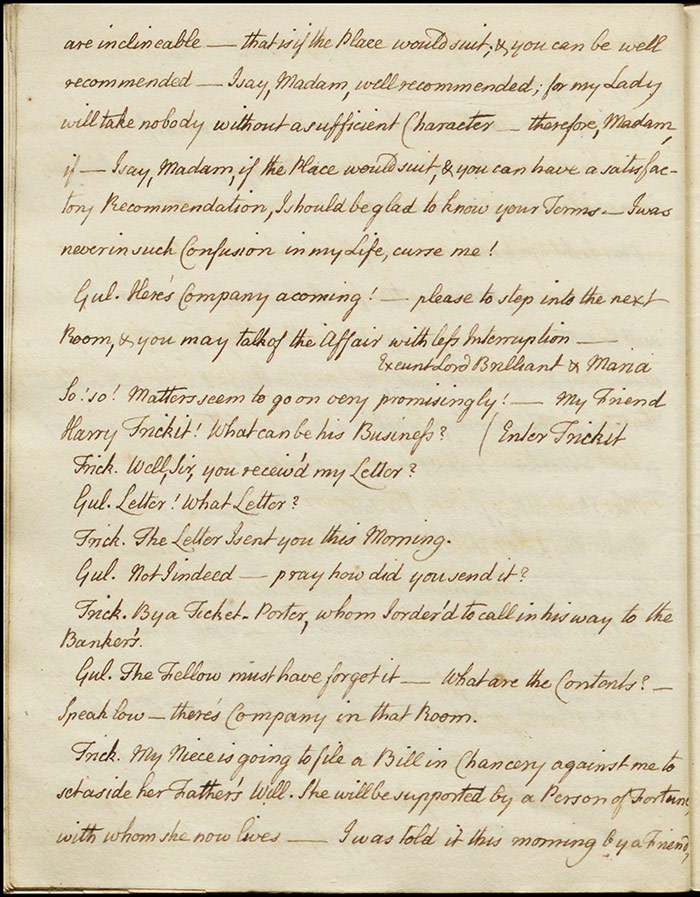

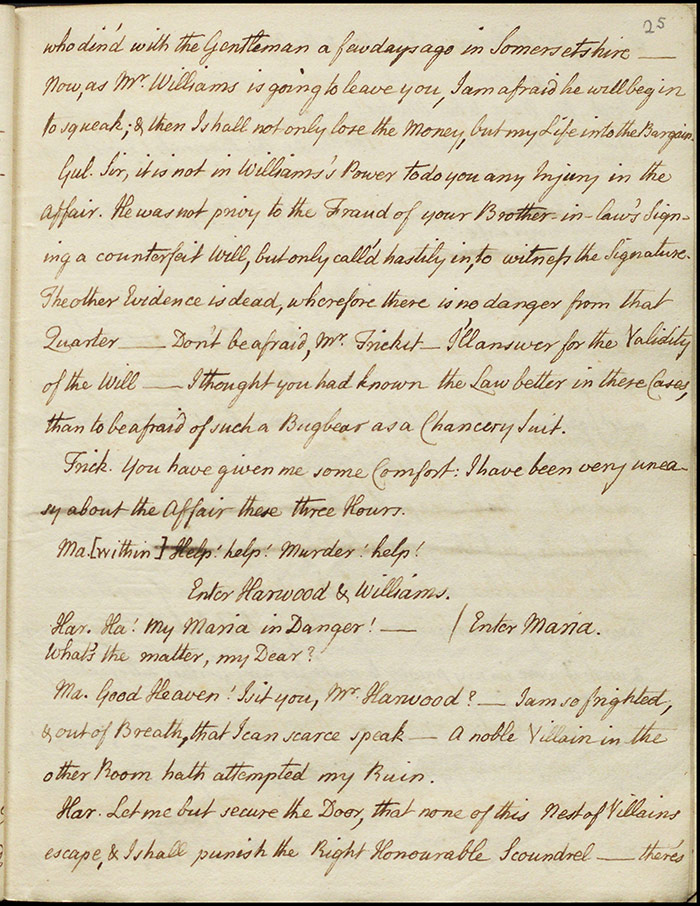

Exit Lord Brilliant, Maria, and Harry Trickit, steward to Lord Brilliant. Their conversation reveals that they have conspired to defraud Trickit’s niece of her inheritance by forging a will and Trickit is worried because Williams is leaving Gulwell’s service and might reveal the plot. Gulwell reassures him that Williams was not aware of the plot. They are interrupted by Maria shouting for help from the next room.

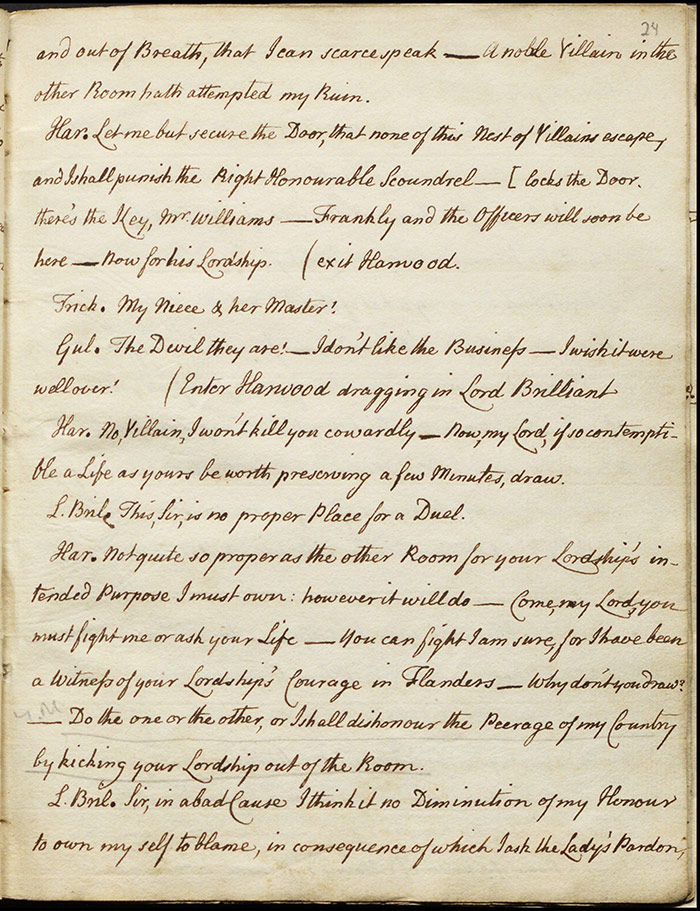

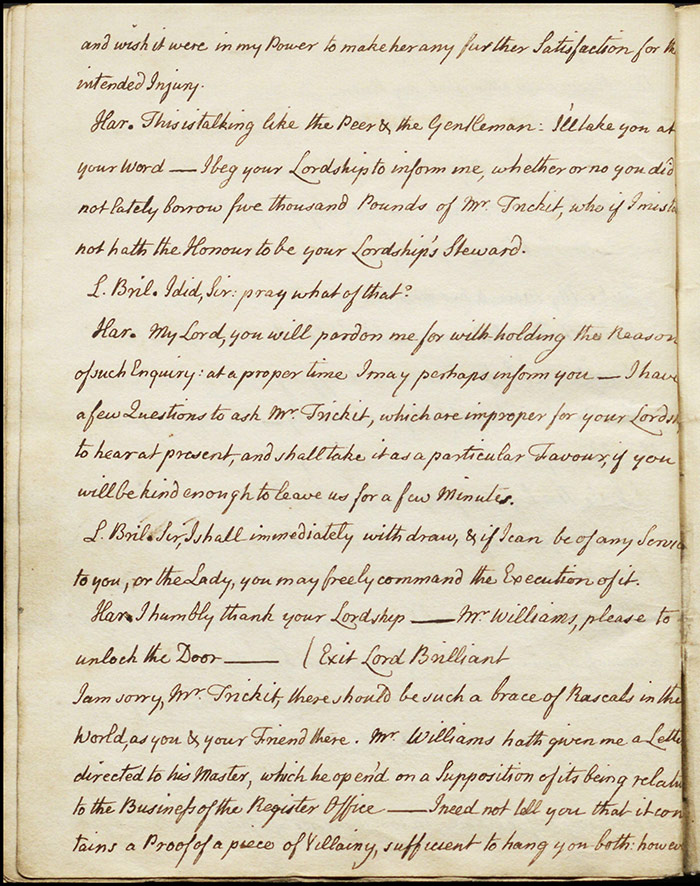

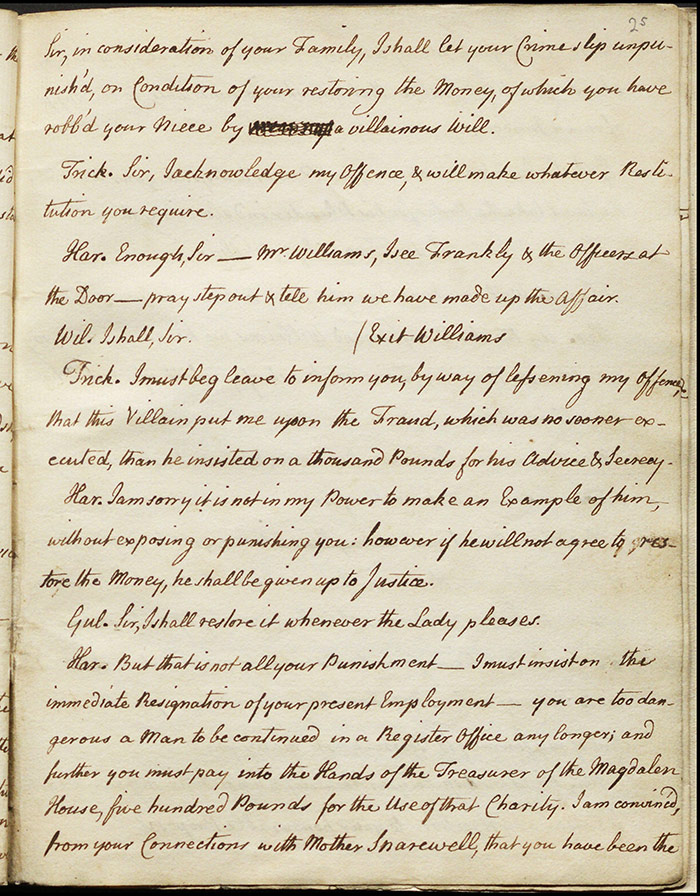

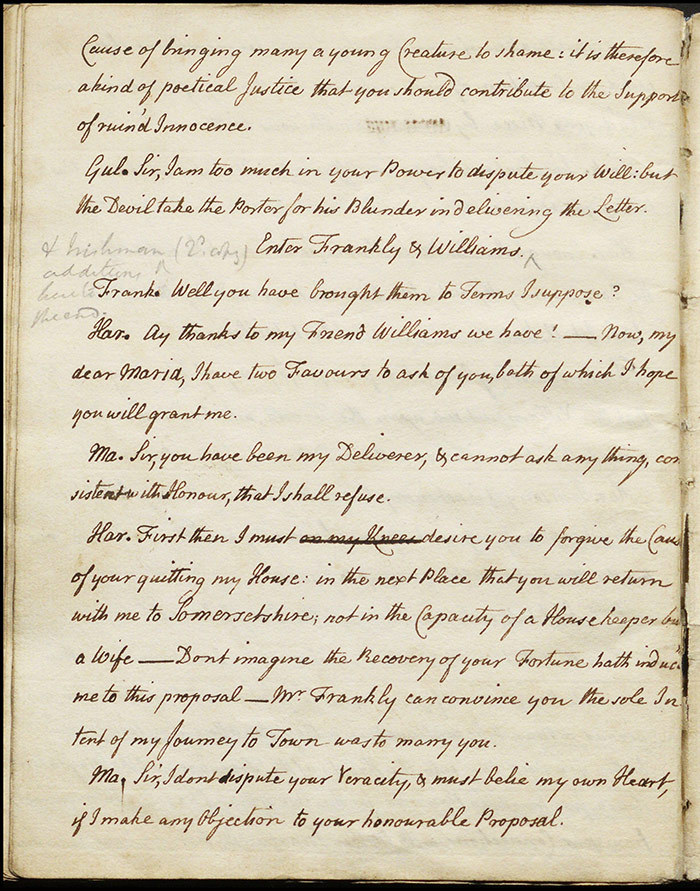

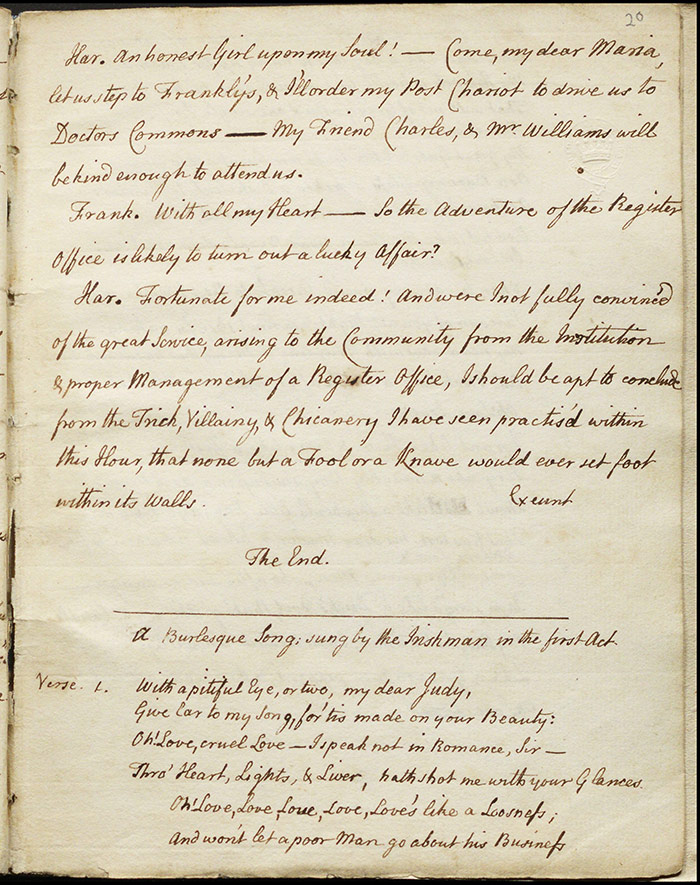

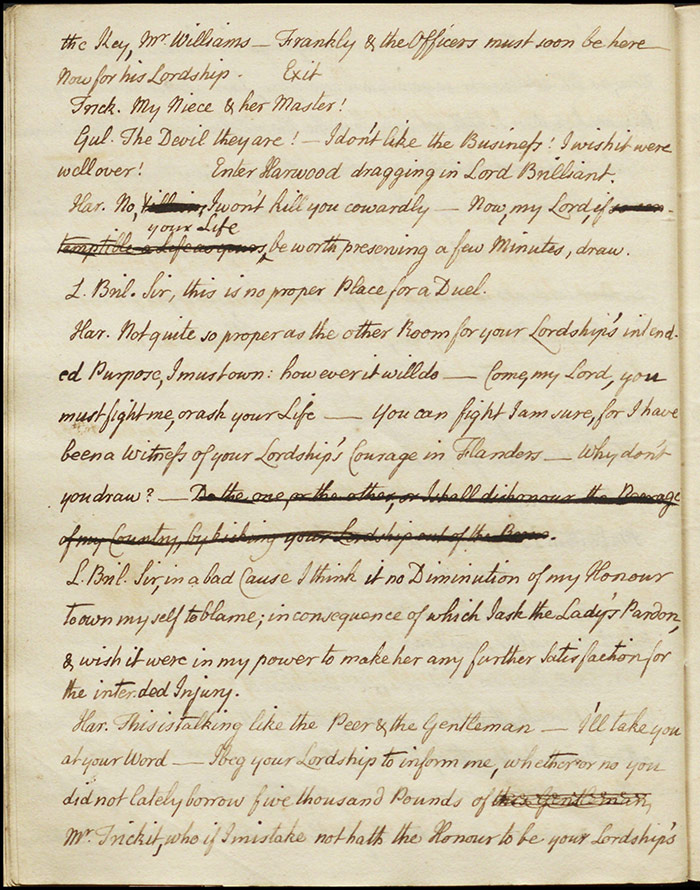

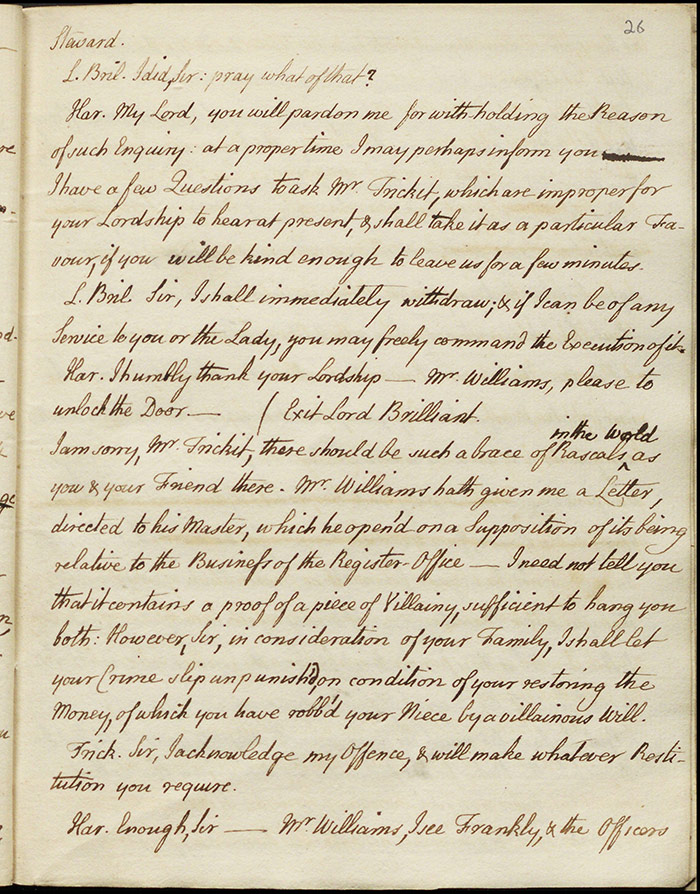

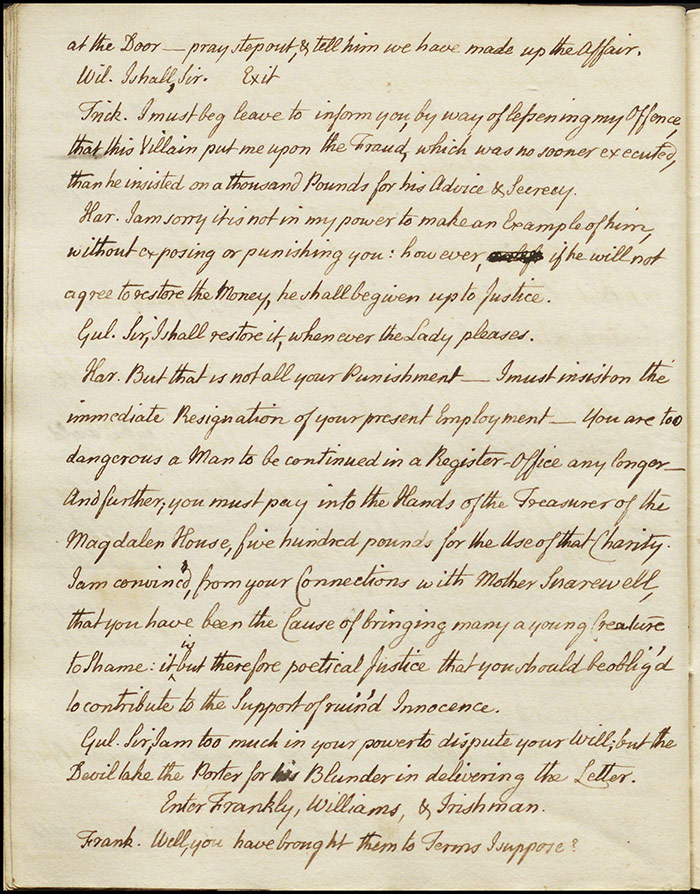

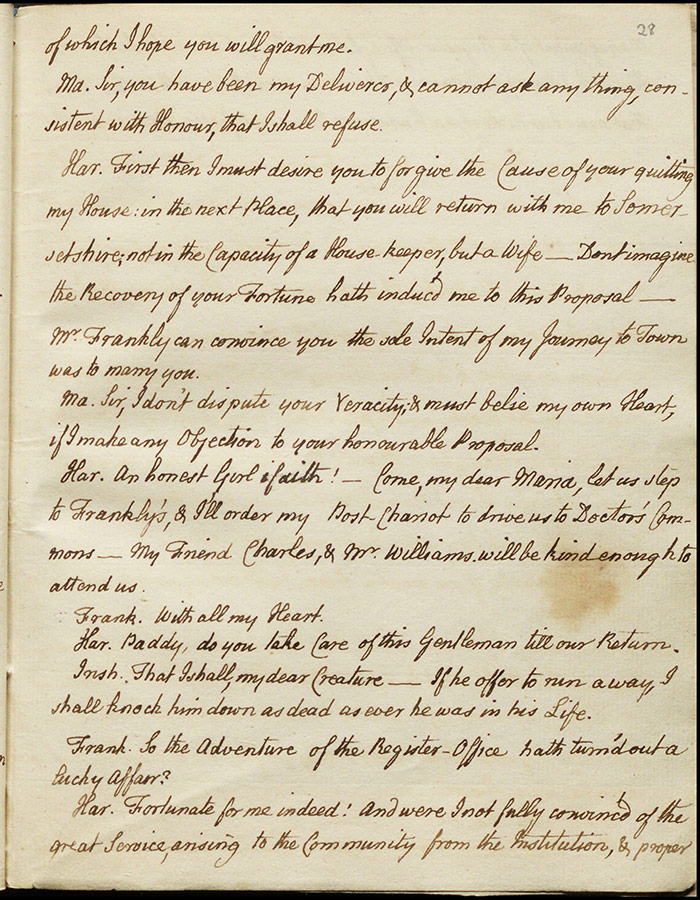

Enter Harwood, Williams and Maria. She reports that Lord Brilliant attempted to rape her. Trickit identified her as his defrauded niece. Lord Brilliant apologises and withdraws after confirming to Harwood that he has borrowed £5000 from Trickit. Harwood tells Trickit that he has the letter sent to Gulwell revealing their crime but he will not use it as long as Trickit restores Maria’s money to her. Harwood also demands that Gulwell resign his office and contribute £500 to Magdalen House as ‘you are too dangerous a Man to be continued in a Register Office any longer’ (f.25r). Enter Frankly and Williams. Harwood begs Maria’s forgiveness and asks her to marry him.

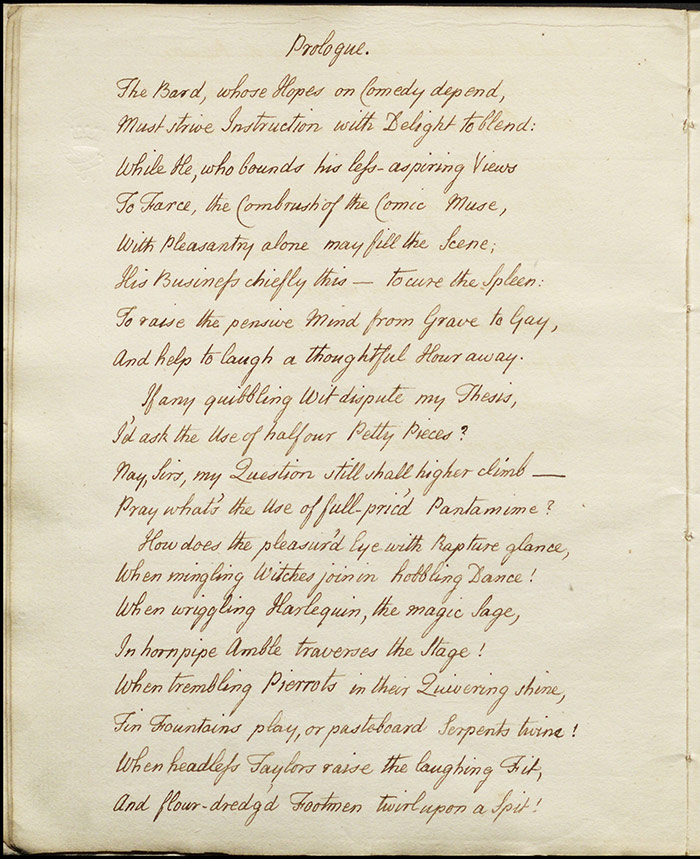

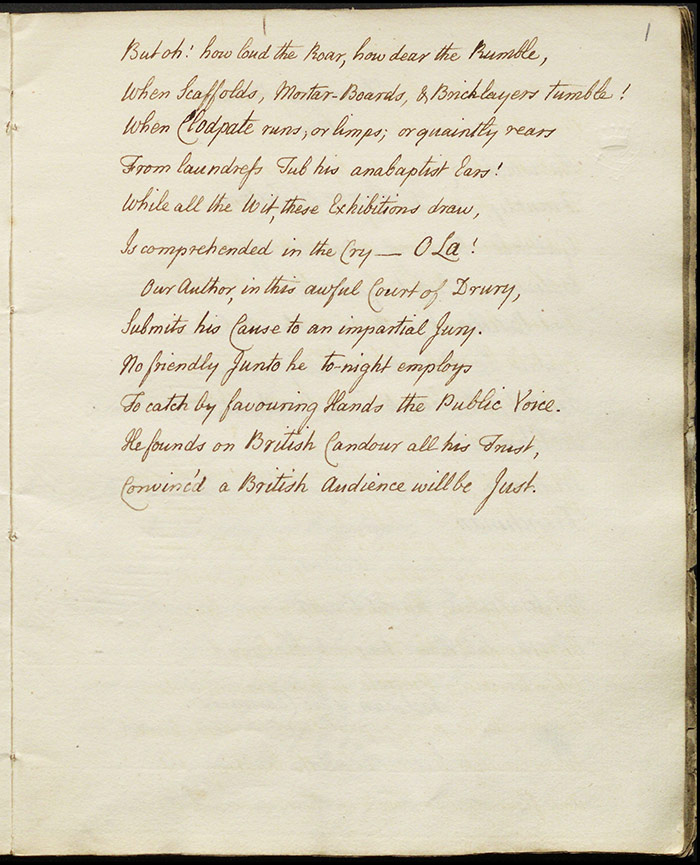

Performance, publication and reception

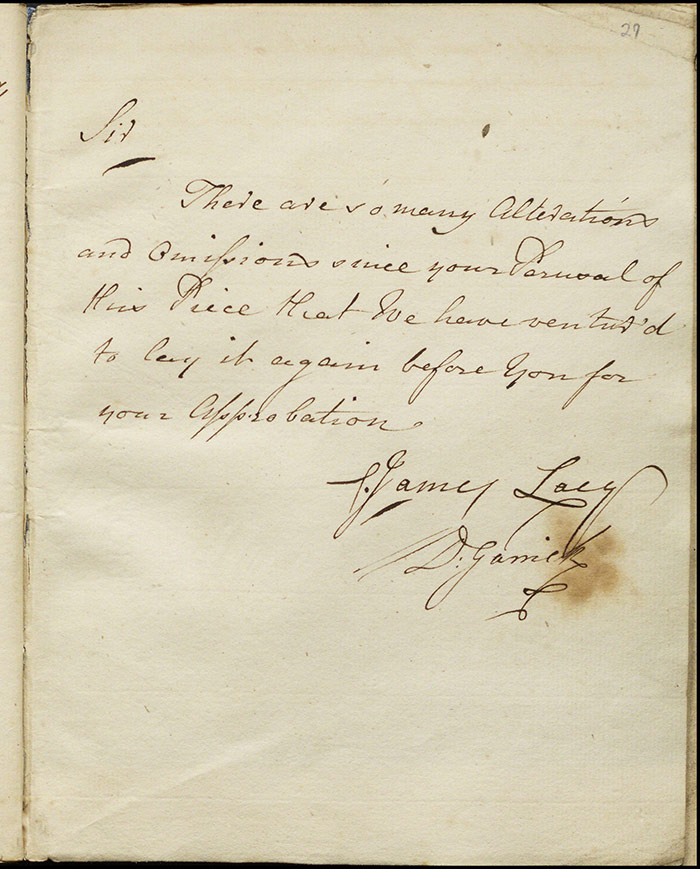

The Universal Register Office was submitted to the Examiner on 7 March 1761 but the play was deemed ‘not thought fit to be acted’. Later that month, Garrick and Lacy resubmitted the piece and included a note which argued that ‘There are so many Alterations and Omissions since your Perusal of this Piece that we have ventur’d to lay it again before you for your Approbation’. The Examiner of Plays evidently agreed and The Register Office was performed on 25 April 1761 at Drury Lane Theatre.

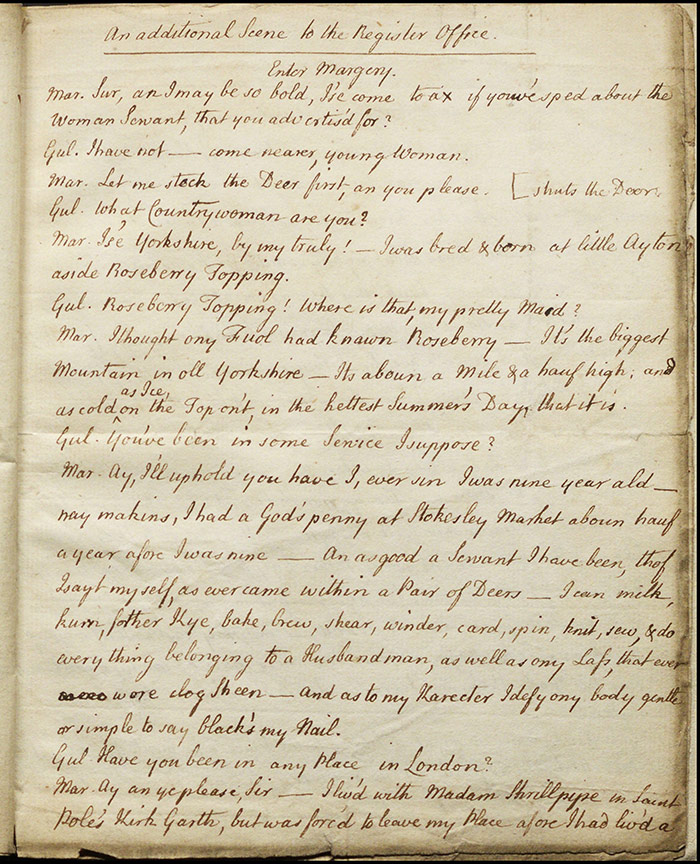

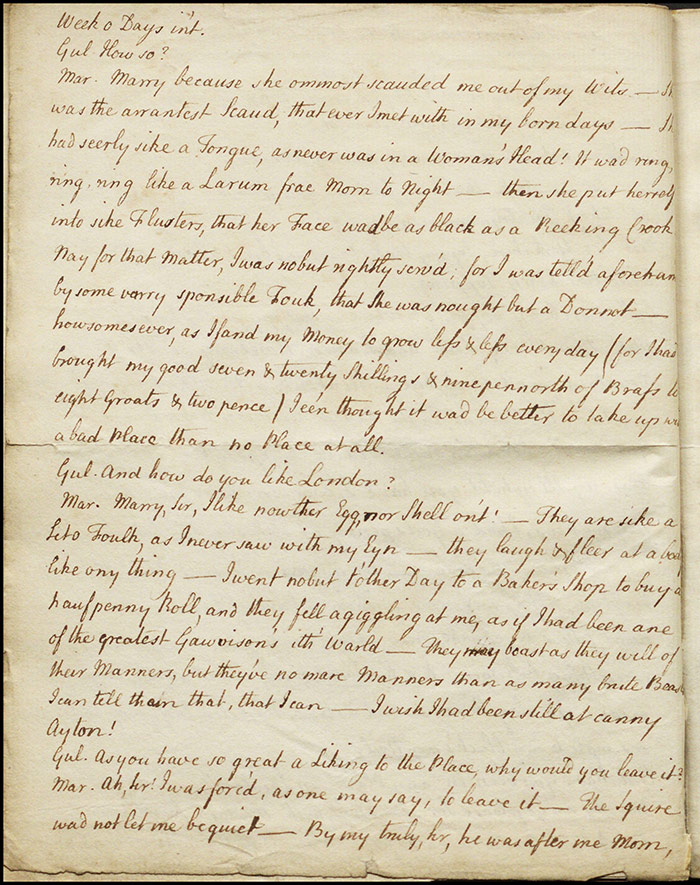

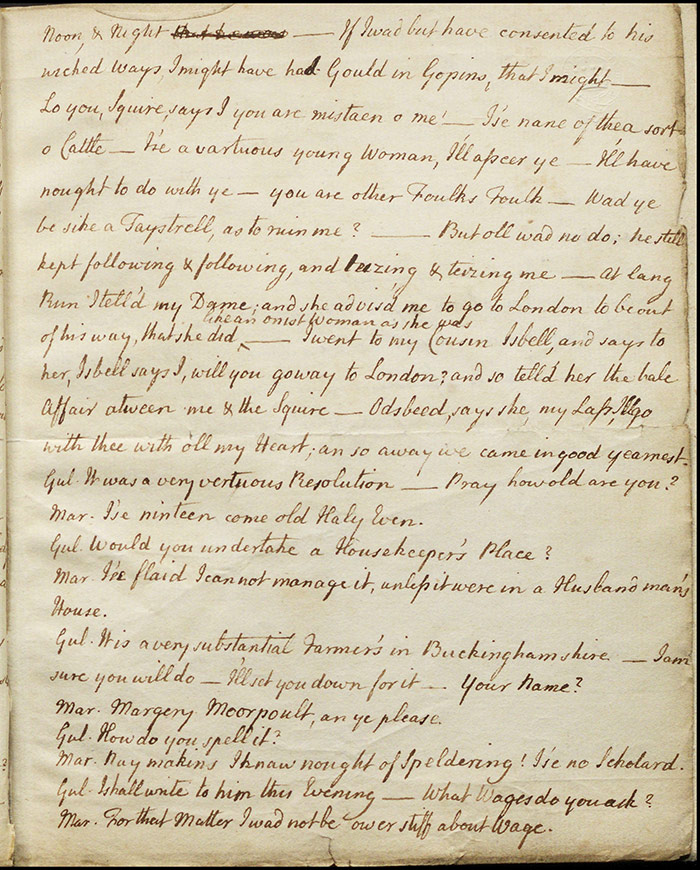

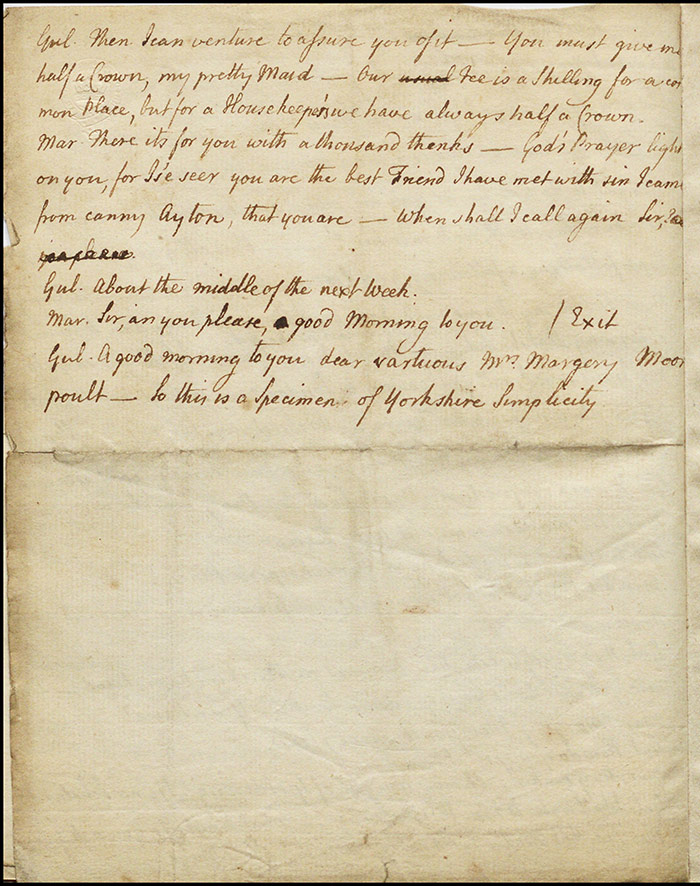

The play had a moderate reception although it was hissed a little at the end (London Stage, 4:2, 861). Nonetheless, it was performed again on 1 May and again on 7 May where the part of Margery was added to be played by Mrs Kennedy (see final 3 images of LA 196). There were no further performances that season. It was revived on 12 April 1761 as a benefit for the actor Mr Love. It proved a poor choice as Love was hissed ‘very much’ in the part of the Scotchman, perhaps due to lingering anti-Bute sentiment. There was something of a revival in May and June 1767 when the play, or rather a version of it, was staged 8 times: the parts of Frankly, Maria, William, Lord Brilliant, and Trickit were all omitted (LS, 4:2, 1246-54). The play continued to be staged in the 1770s and its final performance of the eighteenth century was in 1781.

The play was published by Thomas Davies in 1761 in London and a second edition appeared in the same year. It was also published in Dublin in 1761. The Monthly Review (XXIV, June 1761) described the play as ‘A performance in which the most conspicuous merit is, that the Author of the Minor has borrowed his character of Mrs. Cole, from that of Mrs. Snarewell in this farce. The provincial characters are so perfectly drawn that there is no understanding them’ (441).

The reviewer is referring to the defensive statement made in the play’s advertisement, appended to the end of the published version in response to accusations of plagiarism on Reed’s part:

As there is a palpable Similarity between the Characters of Mrs COLE in the Minor, and Mrs SNAREWELL in the foregoing Performance; it may not be unnecessary here to declare, that the Register-Office was put into Mr Foote’s Hands in August 1758, on his Promise of playing it at one of the Patent-Theatres in the ensuing Season.

(The Register-Office, 47)

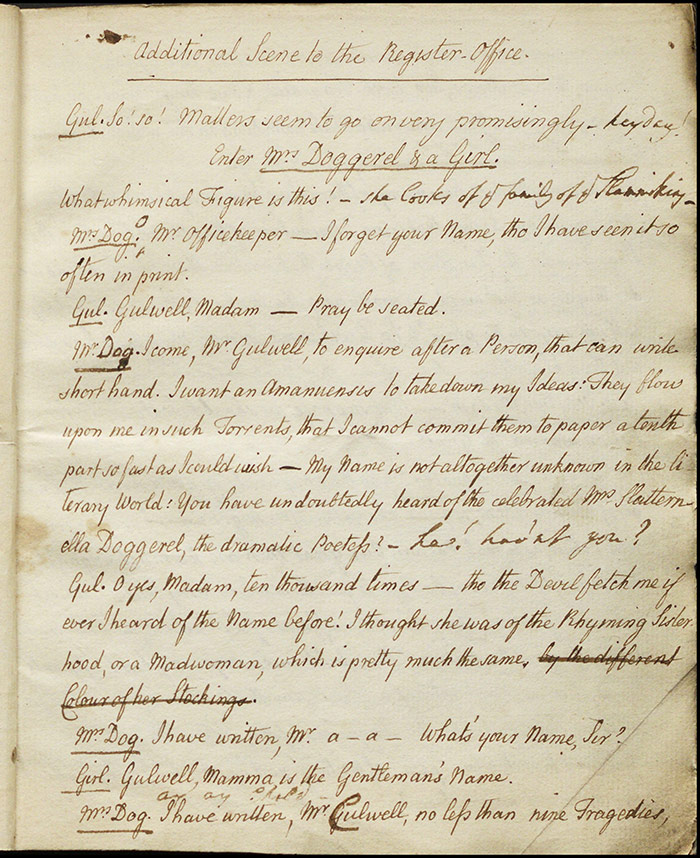

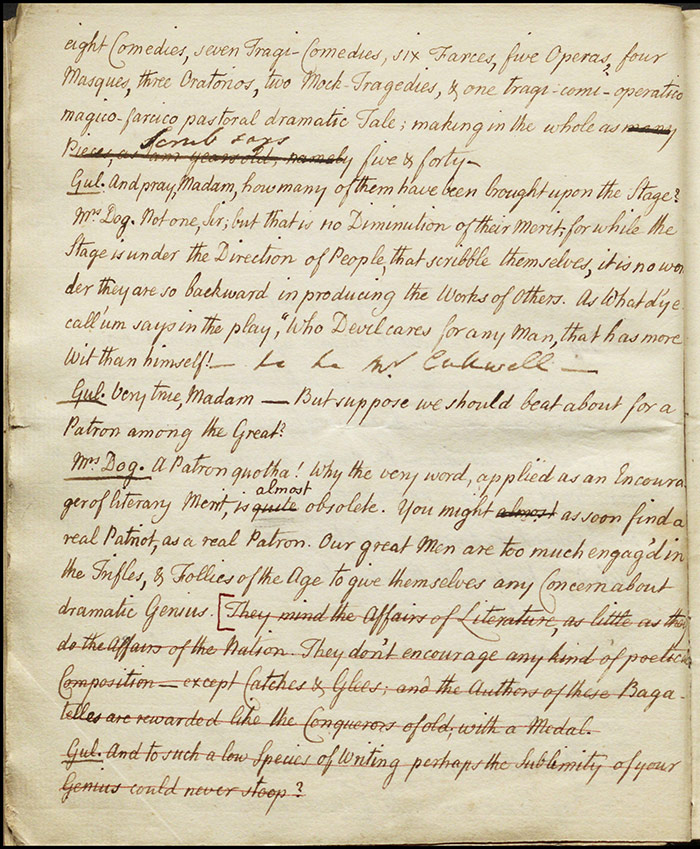

Not one to let a challenge go unanswered, Foote published a mocking riposte that same year titled An Additional Scene to the Comedy of the Minor. He mocked Reed’s tradesman roots, tongue-in-cheek, one imagines: ‘What the devil business has such a fellow to write! let the hound mind his halter making’ (An Additional Scene, 18).

The play stemmed from Henry Fielding’s business venture with his half-brother John described in A Plan of the Universal Register-Office (1751). The business was to be a services market where one could seek or offer employment along with financial, travel, and real estate services, among others. The business originally operated from the Strand but had moved to Castle Court in 1755. Customers could register for sixpence and paid an additional threepence for successful enquiries. Samuel Johnson, for one, was impressed by the Plan and his praise and concerns speaks to those of Reed’s play:

My imagination soon presented to me the latitude to which this design may be extended by integrity and industry, and the advantages which may be justly hoped from a general mart of intelligence, when once its reputation shall be so established, that neither reproach not fraud shall be feared from it; when an application to it shall not be censured as the last resource of desperation, not its informations suspected as the fortuitous suggestions of men obliged not to appear ignorant. (The Rambler, cited in Goldgar, xxi)

However, Johnson’s hopes were not well founded. Other similar competing enterprises were more disreputable, particularly with regard to the sex industry, by the time of Reed’s play.

Commentary

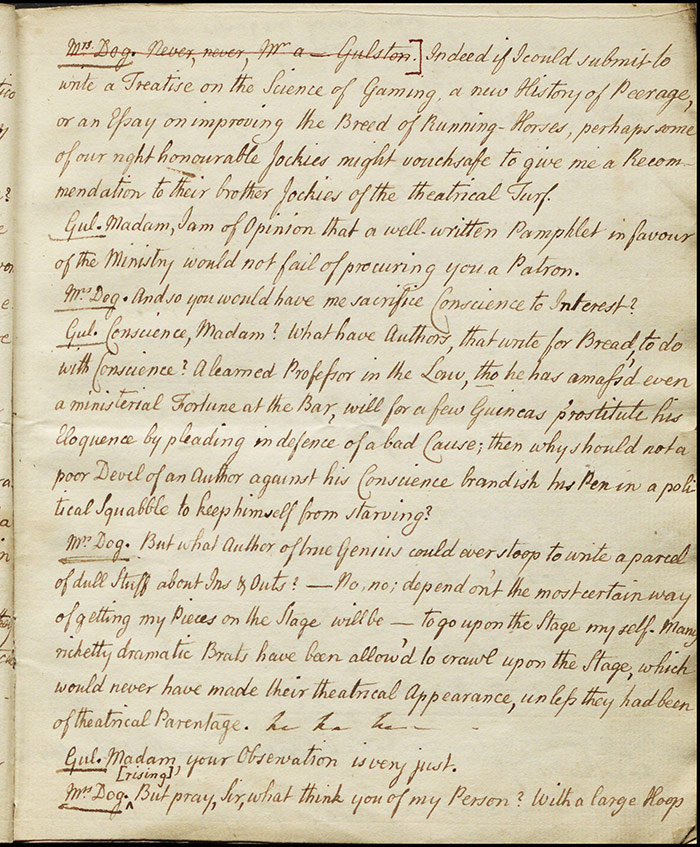

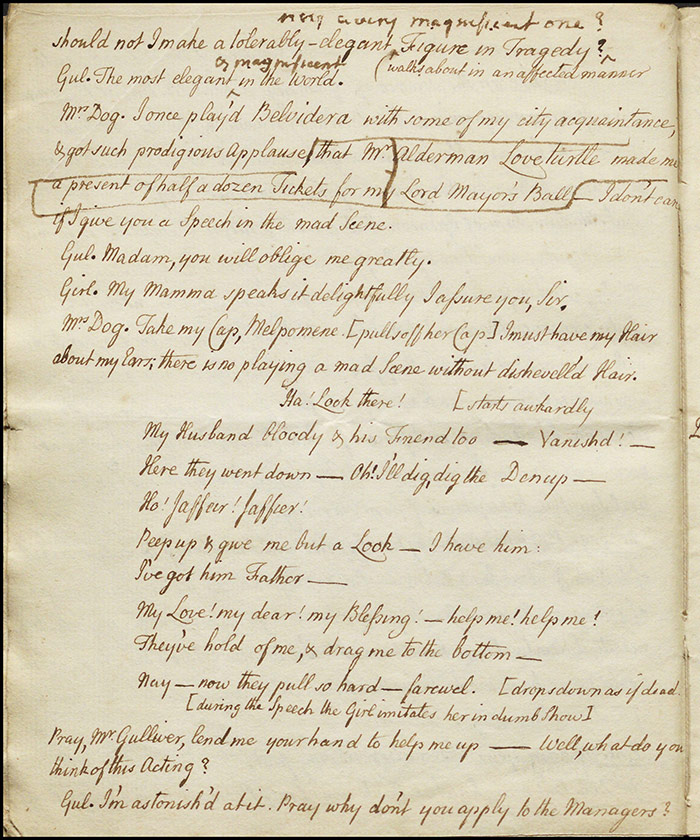

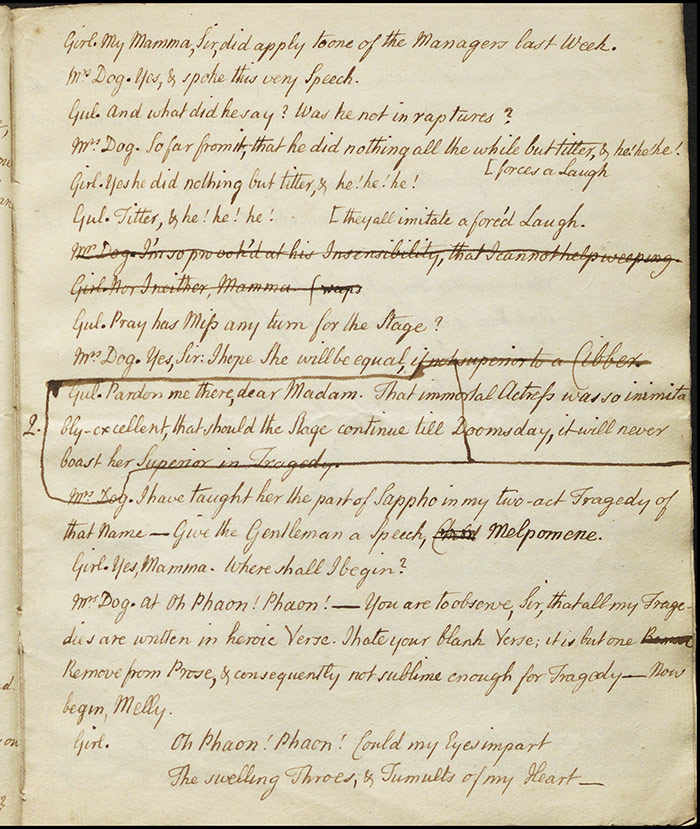

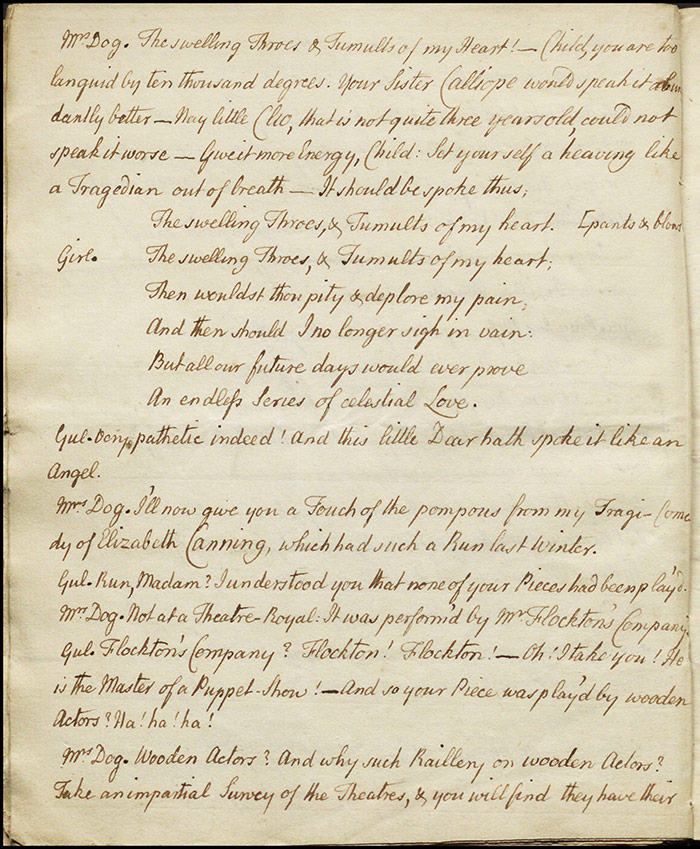

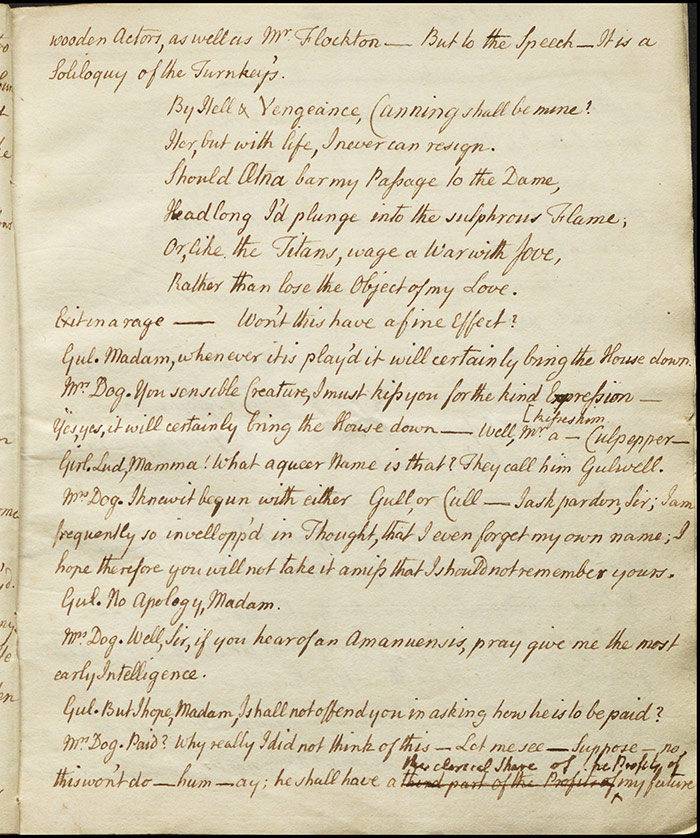

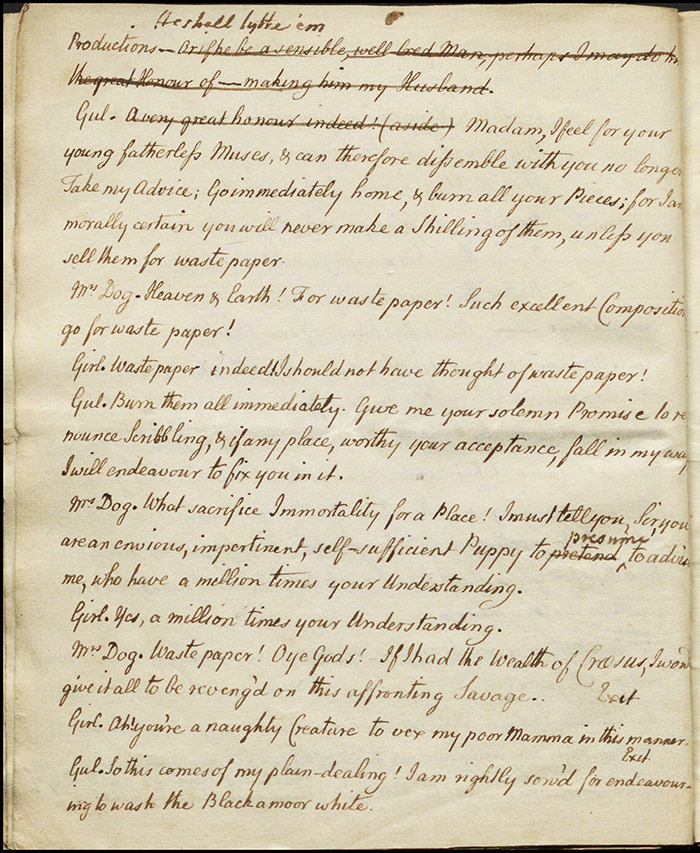

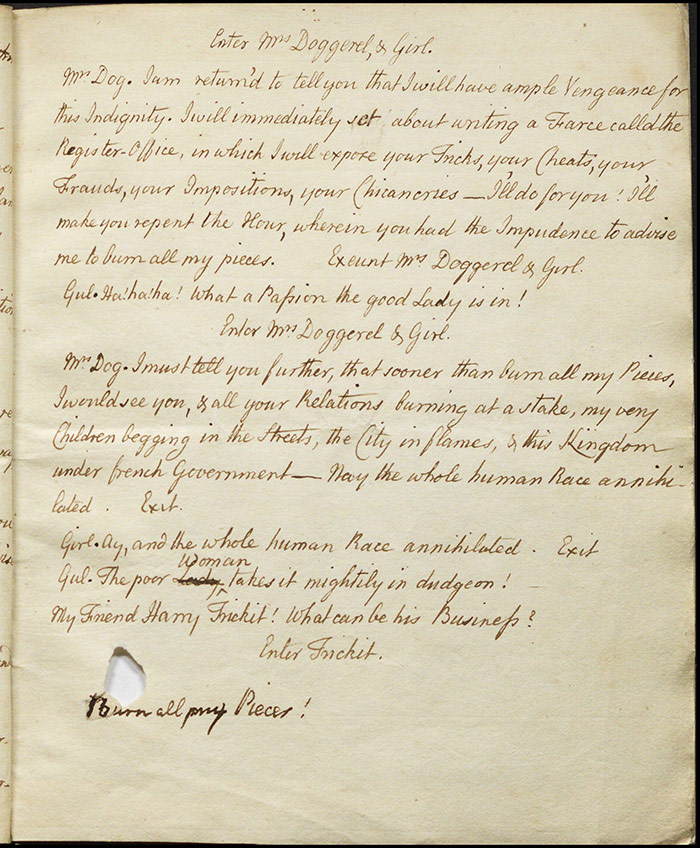

LA 189

The manuscript shows a number of emendations and excisions marked in pen and in pencil. While there are some deletions that may be likely attributed to the manager/author, we can be reasonably sure that most are made by the Examiner. Passages are crossed out, underlined, or marked in brackets. For many of them, the Examiner has underlined and made an indication (it is difficult to make out what this is but it is consistent and may be ‘out’ or the deleatur symbol or both) in the margin in pencil which gives a degree of certainty not always found in the Larpent manuscripts as to who is making the excision. The phrases and words found objectionable are mostly related to blasphemy, profanity, sexual innuendo, and disparaging comment on the nobility and/or the character of the age. Of particular interest is the excision of an entire character, Lady Manlove, who seeks a manservant for, it is suggested, sexual services and heavy censorship of Mrs Snarewell’s lines where she conflates religious experience with sexual pleasure.

There are numerous examples of the language of religion being deleted by the Examiner. Words deemed inappropriate for stage utterance include ‘spiritual’ (f.4v); ‘shalvation’, and ‘providensh’ (f.7r); spoken by the Irish character). These are relatively straightforward incidents of mild blasphemy but the Examiner is unequivocal. It is intriguing to note, however, that profanities such as ‘bitch’ (f.16v) do not draw his ire. These are picked up in LA 196, however, so it is possible that this is simply an oversight as far as the original submission is concerned or perhaps the Examiner took a sterner line with it as the play was a resubmission.

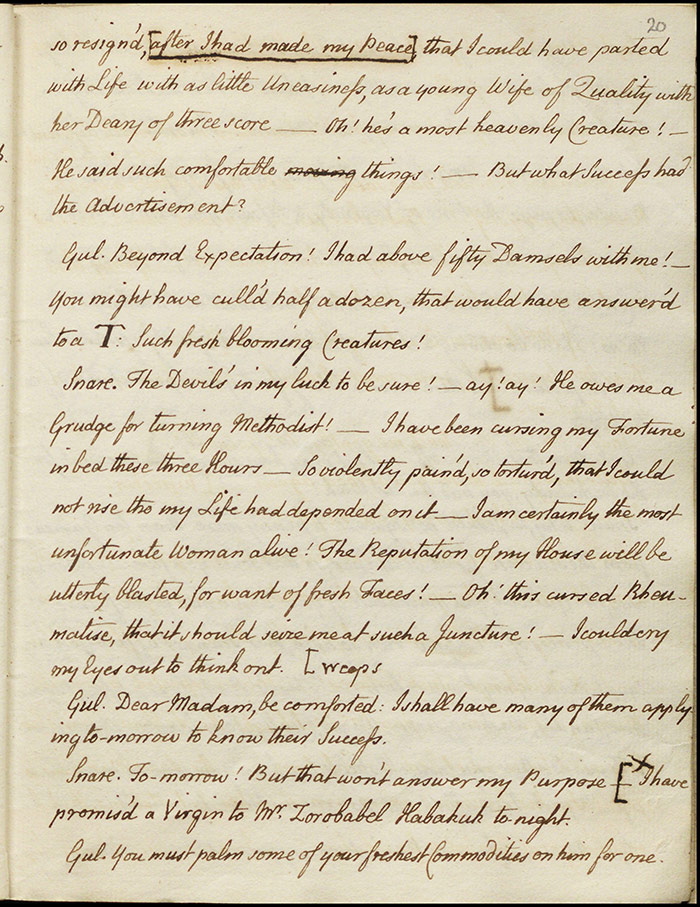

Frankly’s early observation that ‘as many Proselytes have been made to the Flesh by the Knavery of this Rascal, as to the Spirit by the most popular / Preacher in Town’ (ff.2v-3r) is the first example of a number of parallels drawn between vice and spirit that draw the Examiner’s attention. Where it is most pronounced is in Mrs Snarewell whose dialogue is positively riddled with such innuendo, the most prominent example is given here:

Poor Mr Watchlight the Tallow Chandler, was call’d twice out of Bed to pray with me – the dear Man was so fervent in his Prayers, & so earnest in his Ejaculations, that I receiv’d great Comfort and Consolation – I was so easy, so compos’d, so resign’d after I had made my peace with Heaven, that I could have parted with Life with / as little Uneasiness, as a young Wife of Quality with her Deary of threescore – (ff.18v-19r)

The Examiner’s objections to Mrs Snarewell’s character stretch beyond such lasciviousness. Any claim she makes to religiously-minded living is deemed unfit for the stage, given her status as a procuress. For instance, when she insists to Gulwell ‘if we expect to be happy hereafter, we must endeavour to do as we would be done by’ (f.19v). Thus although it would be self-evident to the audience that she is, by the mores of the day, delusional as to imagining herself attaining heavenly respite, the claim cannot be made. A humorous scene where she sings a ‘hymn’ is also marked for excision: despite the words being relatively innocuous (with perhaps the exception of a reference to a handmaid groaning, the genre of the hymn appears to be protected from any kind of mockery (f.20r).

Other items of note which are marked for removal include an underlined reference to a ‘superseeded General’ (f.3r) which seems likely to refer to a protagonist in the Seven years’ War: references to real people on stage were generally not permitted by Examiners. The resubmission has ‘placeman’ instead.

Gulwell’s references to Rochester’s poems and John Cleland’s bawdy novel, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure are also marked for removal (f.22r). Naturally, despite Lord Brilliant’s atrocious behaviour with his attempt to rape Maria, Harwood’s threat to ‘dishonour the Peerage of my Country by kicking your Lordship out of the Room’ is deemed inappropriate (f.24r). We might also note that a reference to Brilliant as a ‘villain’ on the same folio is passed without comment here but is marked for excision in the resubmission as was the case with ‘bitch’ above. Finally, there is a striking excision related to the Irish population in London when Patrick O’Carroll boasts that ‘half my Countrymen lives in London’ (f.6v), this struck a chord with the Examiner (‘a great many [Irishmen]’ is substituted in LA 196). Anxieties about hordes of migrant Irish workers coming to London and its environs offering cheap labour were certainly felt in the period and such a swaggering assertion by O’Carroll may have agitated the theatrical audience.

LA 196

There are three main points of interest in this resubmitted manuscript. Firstly, it seems evident that there was some form of additional communication between the Examiner’s office and Drury Lane management as the character of Lady Manlove has been deleted. It may be surprising that there are no excisions or comments actually marked on LA 189 relating to her scene but it was perhaps so audacious and provocative that such detail was unnecessary and the character was ordered removed in its entirety. We may infer then that the Examiner’s office was not aloof and that there were channels of communication open to managers outside of the exchange of manuscripts.

The second major point of interest from a censorship point of view is that the resubmission contains a multitude of lines and phrases whose removal was already requested in LA 189. Examples occur throughout the manuscript and they provoke questions over what Garrick and Lacy sought to achieve by doing so. It seems unlikely to be an error on their part or on the part of their copyist as there are a couple of significant changes to the plot (primarily the removal of Manlove, the reappearance of O’Carroll in the final scene). We might infer then that they believed that removing Lady Manlove and rewriting Mrs Snarewell’s lines would satisfy the Examiner’s office. Whether this was a risky attempt to sneak these elements past the Examiner or a genuine misunderstanding of what was required of them will remain unknown.

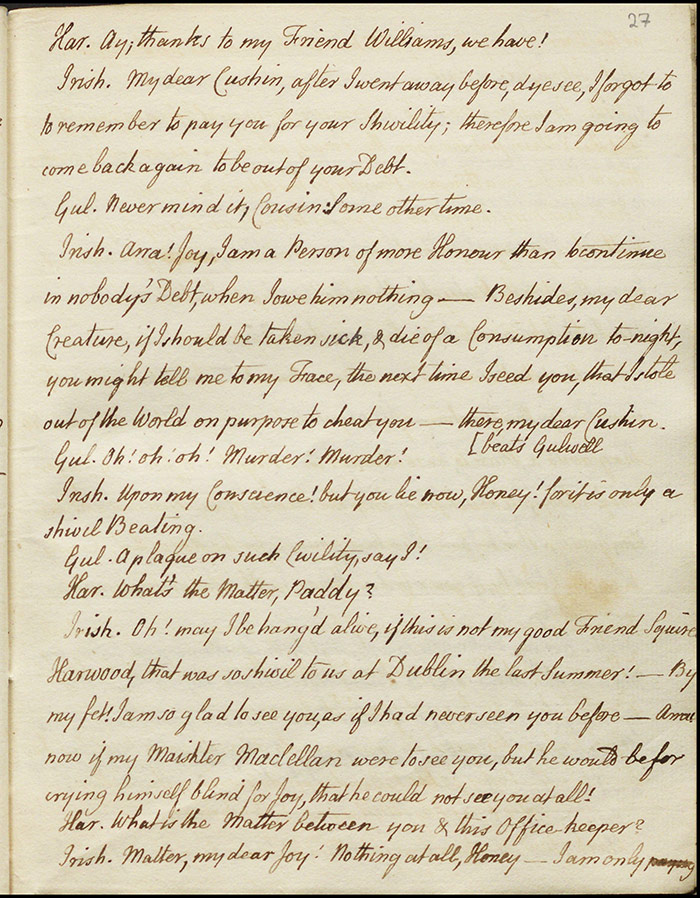

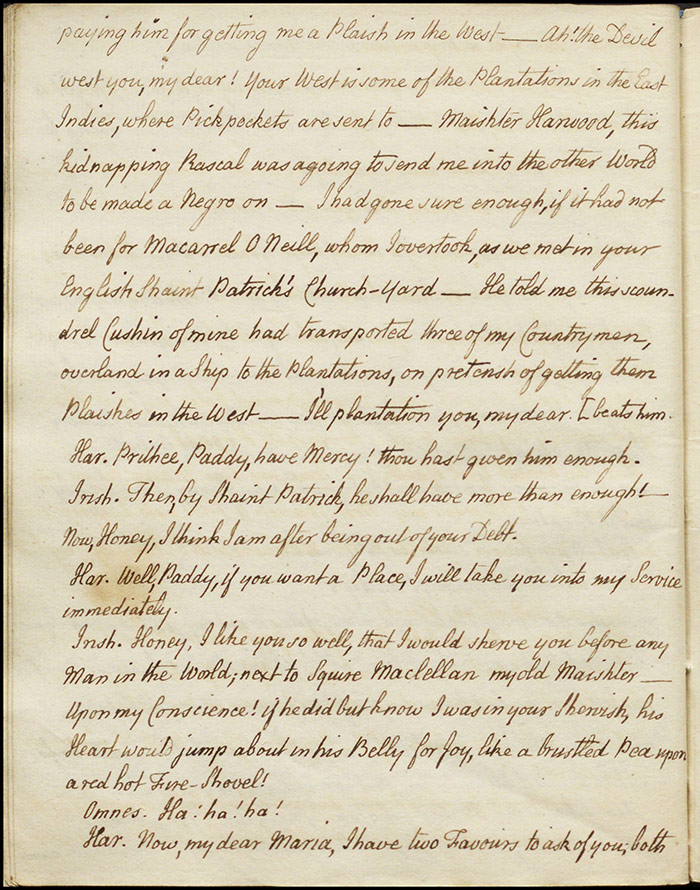

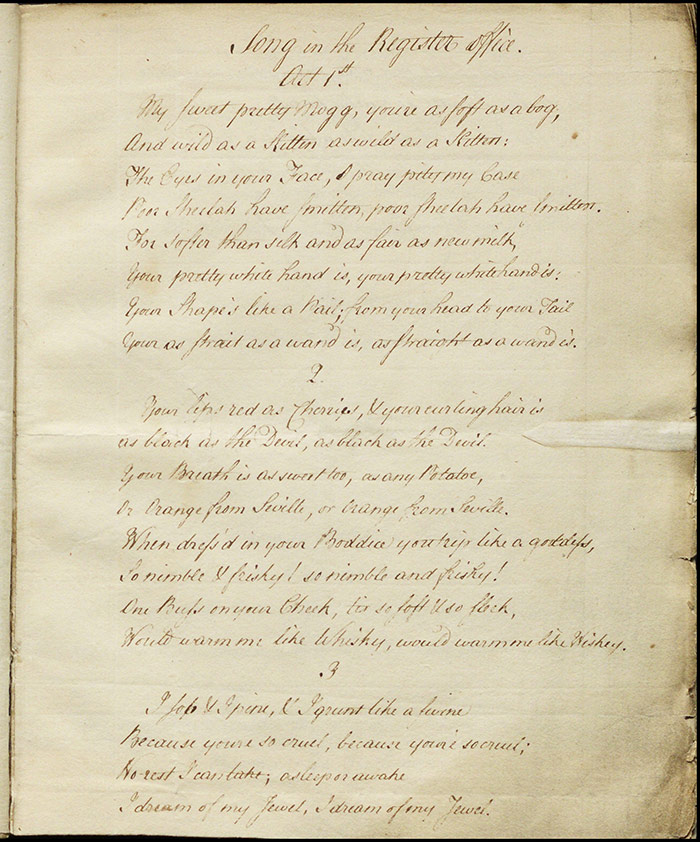

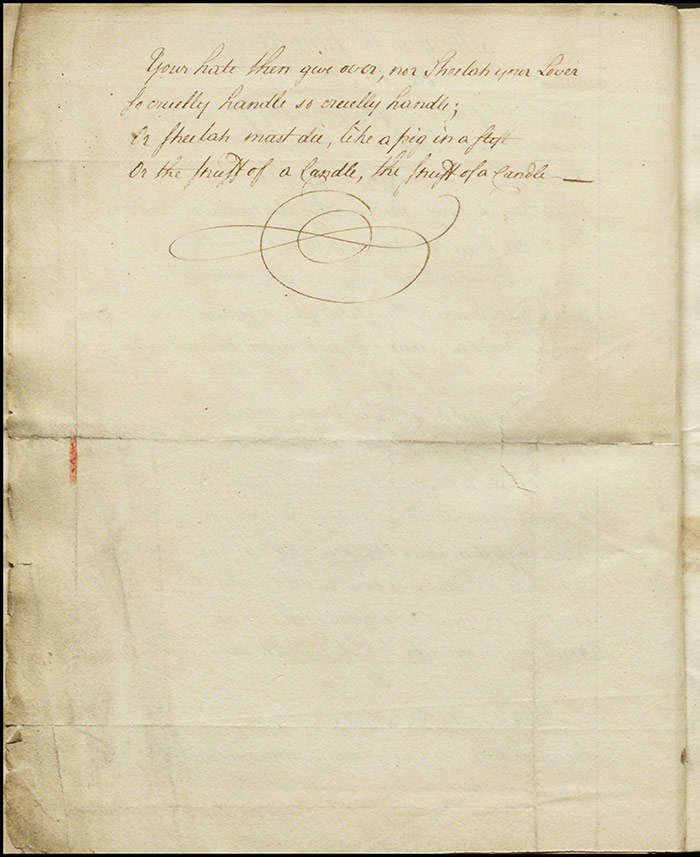

Finally, there is an additional unfoliated scene added to the end of this manuscript which features Mrs Doggerel, a literary figure (LA 196, nf). There are references to political chicanery and an analogy between the dilution of political patriotism and that of literary patronage removed as well as a positive reference to Susannah Cibber. There is also a striking reappearance of O’Carroll in the final scene where he gets to mete out justice to Gulwell in the form of a beating (ff.26v-27r). It may be that this was simply a dramaturgical decision based on the popularity of Stage Irishman specialist John Moody, an audience favourite since his appearance as Sir Callaghan O’Brallaghan in Love á la Mode (1759), that they decided to re-introduce him. It is also possible that there was some sense of appeasing the Examiner’s concerns about the play’s tendency by ensuring that Gulwell was properly and publically punished for his nefarious actions.

Further Reading

Monthly Review (XXIV, June 1761).

L.W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino: The Huntington Library, 1976), 144-48.

L. Lynnette Eckersley, ‘Reed, Joseph (1723–1787)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/23273, accessed 5 April 2017]

Samuel Foote, An Additional Scene to the comedy of the Minor (London: J. Williams, 1761).

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

Bertrand A. Goldgar (ed), The Covent-Garden Journal and A Plan of the Universal Register Office (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), esp. xv-xxviii.

Joseph Reed, The Register-Office: A Farce (London: Thomas Davies, 1761).

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]