Fingal; or, Erin Delivered (1813) LA 1776

Author

Unknown

Plot

I am indebted to Kenneth Clarke (University of York) for supplying me with this plot synopsis and the information on Cesarotti.

A ‘dramatic poem’ in two parts.

The Irish;

Cotullino, lord of Dunscaglia, regent during the Scottish minority;

Degrena, wife of Crugallo, soldier, who dies in the first attack (assault)

Conallo, soldier

Morano, soldier

Scottish;

Fingal, King of the Caledons,

Malvina, daughter of Toscar, lord of Luta, and lover of Oscar, son of Ossian, nephew of Fingal, lover of Malvina

Morna, confidante of Malvina

Danes

Svarano, King of Loclin, Jutland

Morla, soldier

Chorus

Irish ladies,

Irish and Scottish warriors,

Soldiers of the three nations

Act 1

Sc. 1: exchange between Cotullino and Morano, about the arrival of Svarano and his superior force; Cotullino determines he will fight or die;

Sc. 2: Conallo and Cotullino; lots of talk about the oppressor, death or freedom; Morano enters, more talk of not fighting or fighting etc;

Sc 3: impending battle, like a storm;

Sc 4: Chorus introduces Malvina, praising her beauty; Morna reveals that Crugal has been killed by Svarano; here comes Degrena, look at her face full of grief.

Sc 5: Degrena laments the death of her husband;

Sc 6: Cotullina, Conallo, Degrena & Malvina; Conallo recommends peace; Cotulllina says Degrena’s loss is glorious etc;

Sc 7: Morano, then Morna;

Sc 8: Morla, Cotullino, Morna; Morla – let’s attack; Cotullino – off you go;

Sc 9: Fingal and Oscar; sound the battle horn; both speak about impending battle and their own courage etc;

Sc 10: Malvina, Fingal, Morna, then Oscar; Malvina laments Oscar leaving her for battle etc; Oscar declares his love etc for Malvina

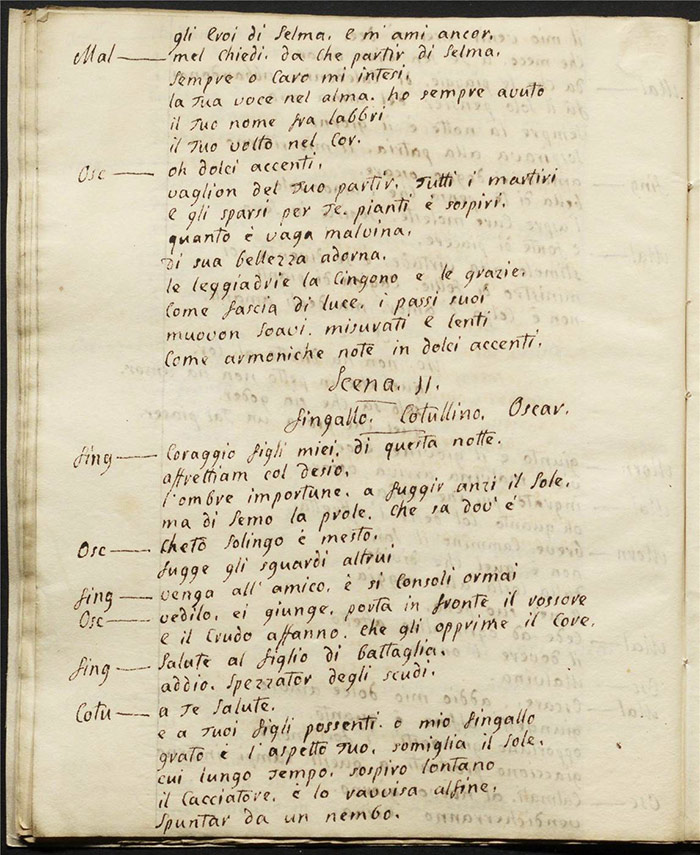

Sc 11: Fingal, Cotullino, Oscar; look ahead to battle, Fingal says he’ll be victorious for sure. Cotullino says he’s oppressed by death.

Act 2 (f.7v)

[Sc 1] Morano and Conallo; more declarations of ardour at the prospect of the impending war;

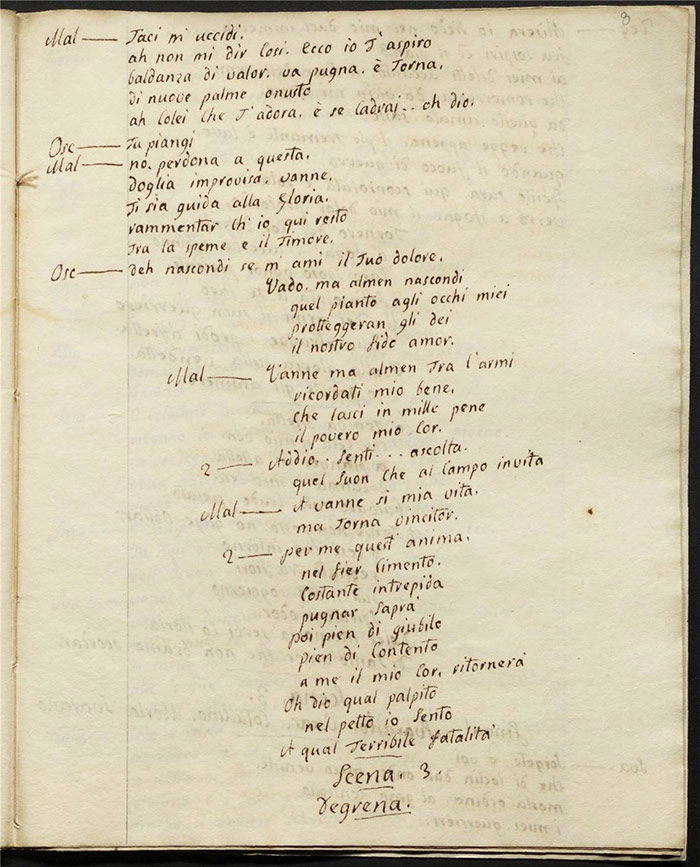

Sc 2: [Malvina and Oscar]; she can’t be parted, he has to go to battle; more talking up the impending battle;

Sc 3: Degrena; laments her grief and suffering; address the tomb of her husband;

Sc. 4 [but misnumbered 3], Fingal, Svarano, Oscar, Cotullino, Morla; Fingal looks forward to the battle; Svarano offers peace terms; rejects them;

Sc 5 [labelled 4]: Oscar, Fingal, Svarano; Oscar and Fingal urge each other on [battle seems to have begun]

Sc 6 [labelled 5]: Malvina, Oscar, Degrena; all wonder how the battle is going, seek to calm each other;

Sc 7 [labelled 6]: Morna; looks for Malvina to give her the news of victory, and Oscar’s safe return

Sc 8 [labelled 7]: Fingallo and Ullina; Fingallo’s son [unmentioned previously?] seems to have died on the battlefield, and Ullina is a harpist who will sing of him

Sc 9 [labelled 8]: Conallo, Morna, then Oscar; Conallo and Morna announce the arrival of the victorious Oscar; Oscar then talks about hanging the spoils of war on the walls, arms etc;

Sc 10 [labelled 9]: Fingallo, and all the others; Cotullino gives Fingallo a famous sword; Oscar and Malvina are united and pledge themselves to each other [oh joy etc]

Sc 11 [labelled 10]: Svarano, Conallo and Morano . Fingal; invitation to Svarano to come to a feast.

Sc 12 [labelled 11]: Cotullino. Malvina. Degrena Morna. Feast. Fingal and Degrena each remember their lost loved ones; Oscar and Malvina declare their love for each other;

Sc 13 [labelled 12]: Fingal and Svarano; Svarano admits defeat and concedes everything to Fingal; the latter then compliments the former’s magnanimity; Let peace live together, long live love, joy and pleasure (etc);

Sc. 14 [labelled 13]: Conallo . Morano; commentary on what’s just happened; goodbyes to Svarano;

Final scene: Fingallo, Conallo, Morano and everyone; hunt scene in the woods provides a dramatic resolution.

Performance, publication and reception

The manuscript was submitted on 3 July 1813 by William Jewell for representation at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. It was refused a licence and was not performed. I have found no evidence that it was published.

Commentary

This is an example of a brief oratorio in Italian that was refused a performance licence. The censorship of an oratorio is not a unique event – see, for example, Handel’s Rossane (1743; LA 41) which has passages marked for omission (although this was performed in the end) – but it certainly is unusual. We are also reliant on John Larpent’s account books to identify the oratorio as being censored; this document was where he kept a record of manuscripts licensed (or not) and his fee for examining them. The Larpent manuscript of Fingal bears no indication that it was not licenced but the account book which has 2 volumes (Huntington Library, Mss HM 19926, 1, f.31r) has ‘Not licensed’ written in the margin.

The oratorio seems to be based on Melchior Cesarotti’s widely celebrated Poesie di Ossian, the Italiantwo-volume translation of MacPherson’s Ossianic poetry published in Padua in 1763. Cesarotti’s translation and accompanying editorial apparatus sought to present Ossian as a classical writer and indeed as a peer of Homer. A more complete 4-volume edition of the Poems of Ossian was subsequently translated by him and published in 1772, again in Padua. Lord Bute, who had also funded MacPherson, provided financial support to this edition and was its dedicatee.

While the title of the oratorio refers to McPherson’s Ossian poems, we can be in little doubt that this is a highly charged political piece and that it very likely evokes Arthur James Plunkett (1759–1836), 8th Earl of Fingall. Plunkett was a Catholic campaigner and in 1804 took the chair of a newly formed Catholic Committee in Dublin to advocate for emancipation. He authored a pamphlet An address to the Catholics of Ireland (1811) and presented petitions for the abolition of the penal laws to London on a number of occasions including 1813. A number of newspapers record him in London that summer mixing in Whiggish circles. On 10 June 1813, he and other prominent Irish Catholics were hosted enthusiastically by the Friends of Religious Liberty (chaired by the Duke of Bedford). At the meeting, a toast was called for the Prince Regent and was ‘received in silence’, doubtless due to his betrayal of the Catholic cause.

There are two passages marked in the manuscript:

Osc[ar] – al Conflitto alla strage, al nuovo sole.

preparate O morveni. la destra e il Cor venite.

il brando mio. d’alta vittoria e segno

punirem lo straniero. fia salvo il regno

Io sapro. Sapro, l’altero

debellare d’avvilir

vi e guida il mio braccio

si corra al cimento

poi torni content

il core a gioir

sia Salva erina o vadassi

tutti con, lei a perir

(f.5v)

[To the conflict to the massacre, to a new sun.

Prepare yourselves, oh Morvens, bring your right [hands] and your hearts.

My sword is a sign of great victory

We will punish the stranger [so] the kingdom may be saved

I will succeed. I will succeed in humiliating the arrogant in defeat

My arm is your guide

May we hasten to the struggle

That the heart may gladly rejoice once more

May Erin be saved or may we all perish with her.]

Cotu – su figli d’Erina Alzate l’aste

piegate l’arco, andiam

secondiam degli amici, il braccio invitto

ardir trionferem, nel gran conflitto

(f.9r)

[children of Erin! raise the flagpole, bend [your] bows, let us go.

Let us match our friends’ undefeated arms (limbs)

Daring we will triumph in the great conflict]

I am extremely grateful to Olga Rachello for translating these two passages.

The rationale for censorship is clear. This example from the archive also shows Anna Larpent’s importance to John’s office. He had no Italian so we can be fairly certain that she was responsible for casting an eye over the manuscript. The unusual flourishes in the margin of f.9r – very different to those made by John – also support this view. Unfortunately, there is no mention in her diary for 3-5 July of this Italian piece (Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library Mss, HM 31201, vol. 8, f.275v), evidence which would make her intervention absolutely certain.

Further reading

Anna Larpent Diary, Huntington Library Mss, HM 31201

Claire Miller Colombo, ‘“This pen of mine will say too much”: Public performance in the journals of Anna Larpent’, Texas Studies in Language and Literature 38:3/4 (1996), 285-301.

L.W. Conolly, ‘The Censor’s Wife at the Theater: The Diary of Anna Margaretta Larpent, 1790-1800’, Huntington Library Quarterly 35:1 (1971), 49-64.

_______ The Censorship of English Drama, 1737-1824 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 41-44.

Enrico Mattioda, ‘Ossian in Italy: From Cesarotti to the theatre’ in Howard Gaskill (ed), The Reception of Ossian in Europe (London: Continuum, 2004), 274-302.

C. J. Woods. "Plunkett, Arthur James 8th earl of Fingall Viscount Killeen". Dictionary of Irish Biography. (ed.) James McGuire, James Quinn. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

[http://dib.cambridge.org/viewReadPage.do?articleId=a7378, accessed 3 February 2019]