MP; or, The Blue Stocking (1811) LA 1688

Author

Thomas Moore (1779–1852)

Born in Dublin, Moore was one of the first Catholic students to attend Trinity College Dublin in 1795 where he was friendly with Robert Emmett, later executed for treason. A classical scholar, Moore translated Anacreon but was also engaged with revolutionary politics while at Trinity.

Irish students with a view to being called to the bar were obliged to attend one of the Inns of Court in London. Moore enrolled in the Middle Temple in 1799 and soon, with thanks to the patronage of the earl of Moira, gained a name for himself in London society by singing his songs at social gatherings. With Moira’s influence, he almost became Irish poet laureate but his father objected.

In 1803 he travelled to Bermuda to take up a position as registrar of the naval prize court but was quickly disillusioned. After a few months exploring the United States, he returned to London in 1804 to begin his literary career in earnest. He published Epistles, Odes, and other Poems in 1806 but it received a scathing review from Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review. Indeed, Moore challenged him to a duel over the matter but the police intervened. The press treated the whole affair with glee, alleging that the pair were going to use paper pellets. The embarrassment appears to have caused him to retire to Dublin for a time.

Happily, it was during his time in Dublin in 1806-1807 that he embarked on the very successful Irish Melodies series (1808-34). This involved him writing words to Irish tunes which he would then sing at parties; the published versions also ensured a steady income for many years. He was also writing patriot poetry and developing a reputation as a whig satirist. In 1824 he published a damning critique of British rule in Ireland with Memoirs of Captain Rock and his patriotism would continue to infuse further works up to his death.

Such was his literary reputation in the wake of Irish Melodies that his oriental romance Lalla Rookh was sold to Longman for the enormous sum of £3000 in 1814 although it would not appear until 1817. Further successes followed but the emergence of large debt from his Bermuda days forced him abroad for three years; notably, he was gifted a manuscript of memoirs by his friend Byron during this time.

He returned to England in 1821 and continued to write his Memoirs of the Right Honourable Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1825). It was well received and enabled him to negotiate a £4000 contract for writing a biography of Byron. Moore’s ownership of the Byron manuscript was contested by the Byron family and, after a legal dispute, it was burnt. Undaunted, Moore published a biography in 1830 and followed up with an edition of Byron’s poetry in 1832-33. He committed the last years of his writing life to a History of Ireland (1835-46) before he died in 1852.

Plot

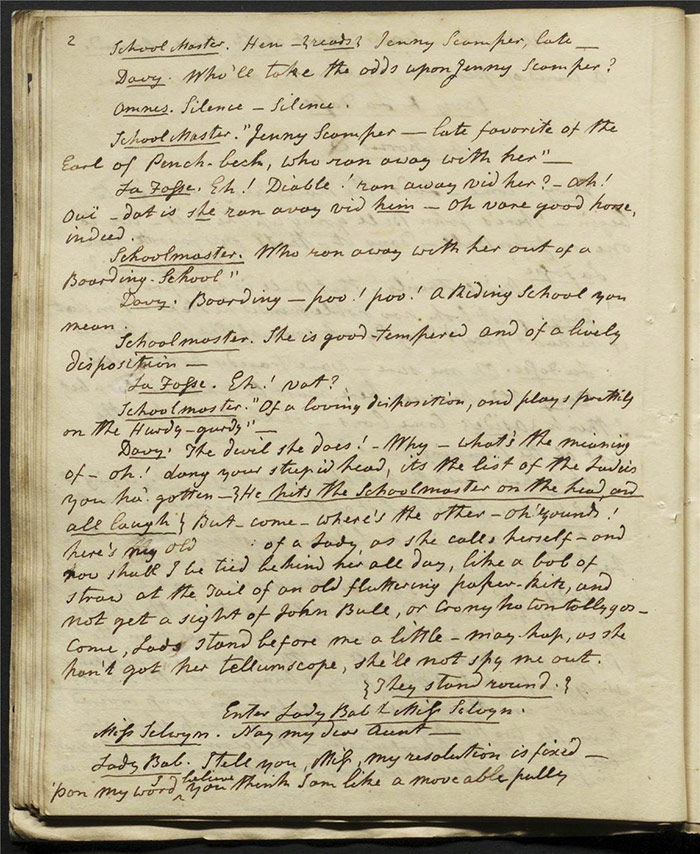

Sir Charles Canvas is on a beach attempting to woo an uninterested Miss Selwyn. Her affections are in fact directed towards his brother, Captain Canvas, who is away fighting in the navy. Their exchange reveals that although Captain Canvas is the elder brother, he was the progeny of a private marriage to which no witnesses are known. As a result, it is only the Canvas parents’ second marriage—and subsequent second child—that is recognized. Thus he holds the title and wealth, rather than the supposedly illegitimate Captain. Irritated at his lack of feeling towards his brother, Miss Selwyn leaves with her friend Lady Hartington. Lady Bab Blue, looking through her telescope, is left with Sir Charles and her booby servant, Davy.

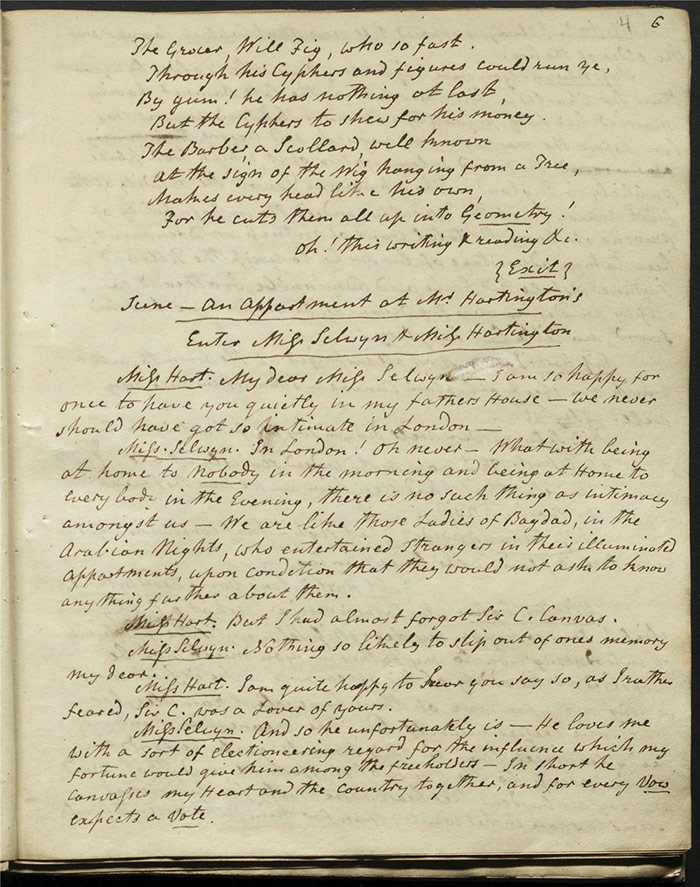

At the Hartington house, Miss Selwyn and Miss Hartington talk about the Canvas brothers(f.4r). Miss Hartington speaks fondly of him as he was close to Henry De Rosier, her beau, but Miss Selwyn interprets her ardour as aimed at Captain Canvas. Mr Hartington joins them, dressed as a beggar as he prepares to go out and relieve distress. They exit and Sir Charles, looking for Miss Selwyn, comes across Hartington in his disguise. Not recognizing him, Sir Charles bribes Hartington to tell Hartington that Sir Charles is a charitable sort.

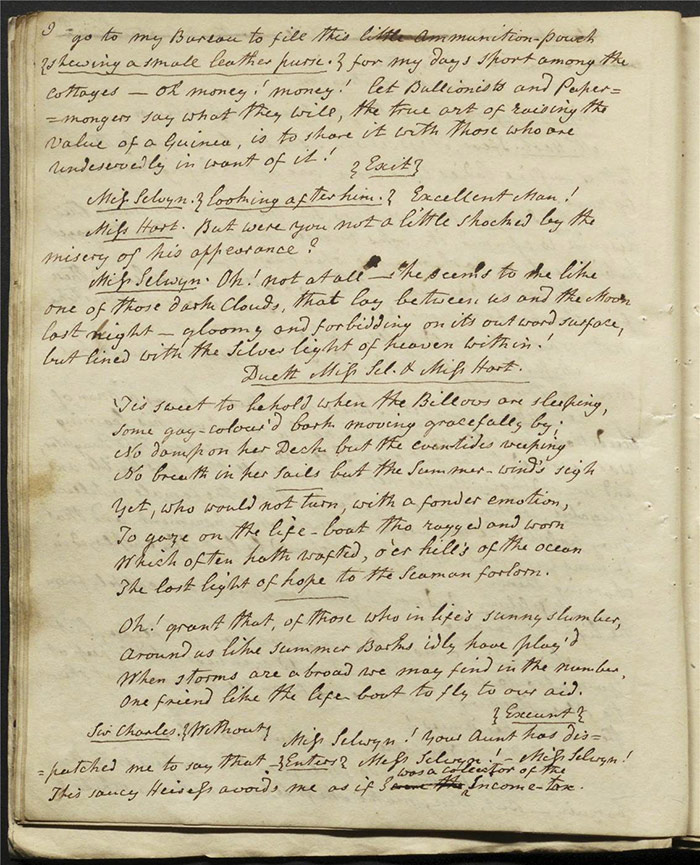

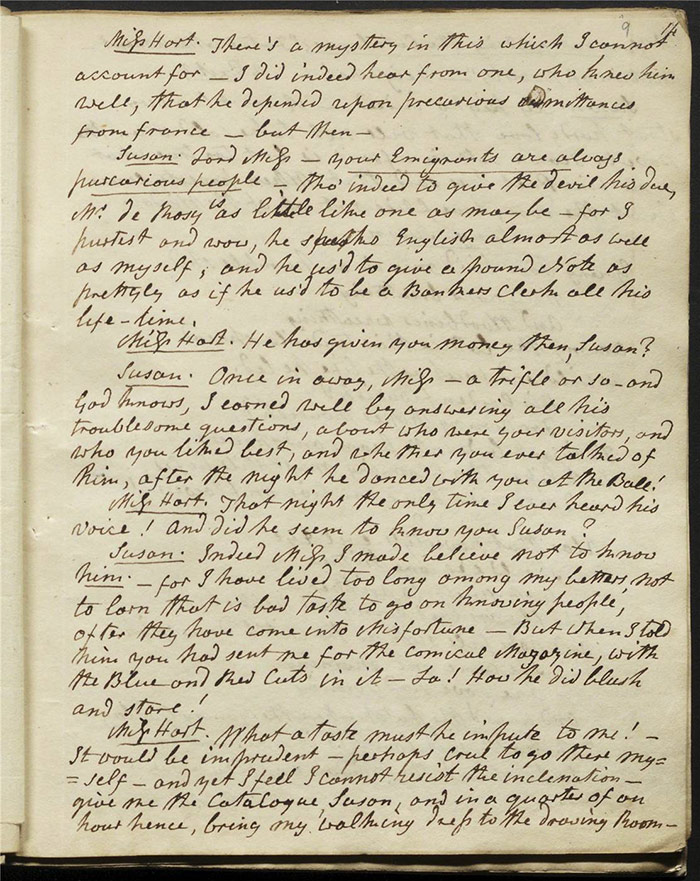

The servant Susan confirms to her mistress, Miss Hartington, that it is indeed Mr De Rosier who has arrived at her house(f.7v). We learn that his material circumstances have changed for the worse.

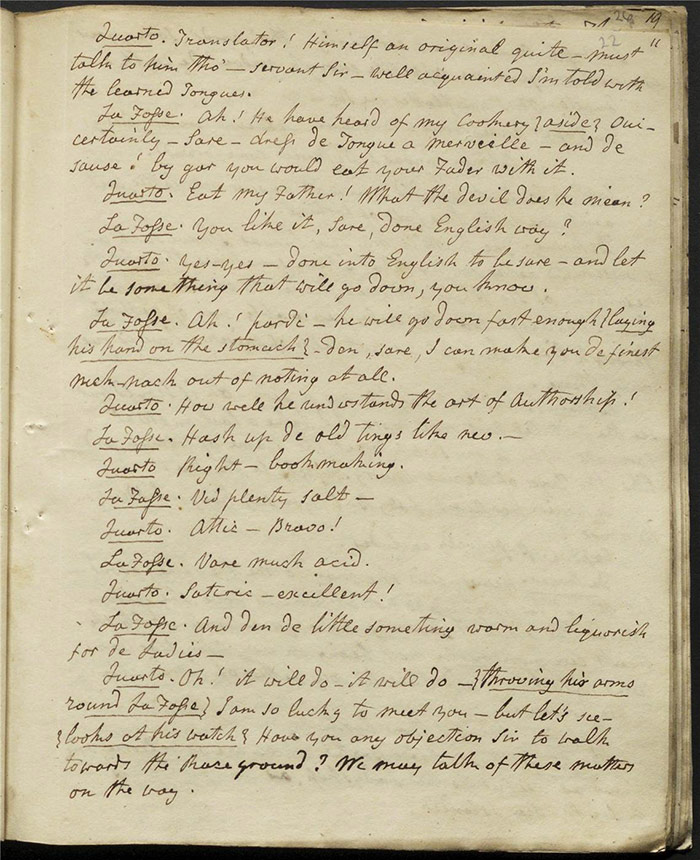

At a circulating library, we discover De Rosier working there for the proprietor, Quarto (changed to Leatherhead in the published version) (f.10r). He has had to take the job to support his mother. Miss Hartington and Susan arrive at the library. De Rosier is embarrassed and feigns distance from her while she struggles to speak to him too but it is clear she loves him still.

Act 2 finds Davy and La Fosse (servant to Madame De Rosier) at the races (f.16r). Lady Bab and Miss Selwyn enter, discussing Captain Canvas, with Lady Bab sending Davy home to instruct the other servants that he is to be refused admission to the house if he calls. Sir Charles then enters and starts discussing a race with a horse called Regent (there is some political allusion in this dialogue). Captain Canvas arrives on the scene, bemoaning the fickleness of women as he has found Miss Selwyn’s home shut to him. He asks La Fosse for directions to Quarto’s library, as he is keen to find his friend De Rosier.

Susan and De Rosier are in conversation at the circulating library; she gives him some hope of Miss Hartington’s affections (f.20r). Quarto enters, pleased with sheets from his new printing-press but De Rosier points out a number of faults. Annoyed, Quarto sends him to Lady Bab with some books. Captain Canvas and La Fosse enter. Captain Canvas and De Rosier agree that the Captain will deliver the books to Lady Bab in the hope of getting to see Miss Selwyn. During their conversation, the miniatures of their respective lovers get mixed up before Captain Canvas leaves.

Madame De Rosier welcomes Mr Hartington (still in disguise) into her house after he was under threat from some belligerent servants (f.24v). Hartington recognizes her magnanimous kindness as well as her poor spirits and leaves something on the table for her, promising it will revive her. La Fosse announces that there has been a coach accident outside and Sir Charles Canvas enters. He blusters on and insists to an appalled Hartington that Miss Hartington has taken a fancy to him. On Sir Charles’s declaration of who he is, Madame De Rosier is delighted to see what she believes to be her old friend’s oldest son. Sir Charles realizes that she has mistaken him for Captain Canvas; moreover, he recognizes that she could witness the legality of the first marriage and thus disinherit him. In a panic, Sir Charles says that he will be writing to the Alien Office to get rid of Henry De Rosier. In order to save her son, Madame De Rosier swears to keep the legitimate Parisian wedding a secret. De Rosier arrives back to discover his mother in tears and angrily brings her away.

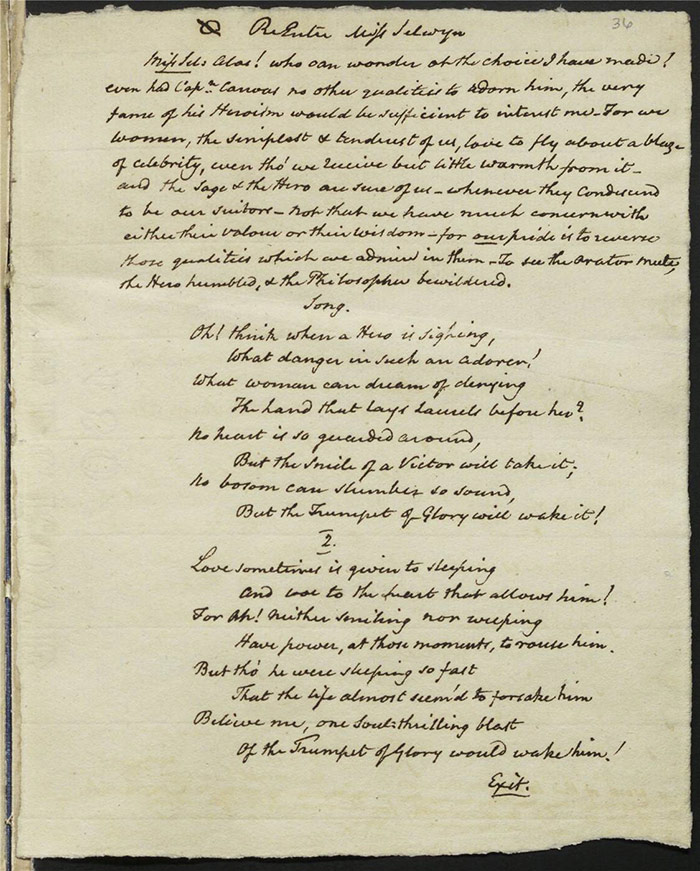

Captain Canvas in disguise is at Lady Bab Blue’s house arranging the books he has delivered (f.29r). Miss Selwyn and a mildly inebriated Davy are also present. She recognizes him but when he returns the miniature in order to end their understanding (as he thinks she has proved false and wants his brother), she is equally angry as it is Miss Hartington’s image that he places in her hands. Captain Canvas arrives and Miss Selwyn feigns affection for him.

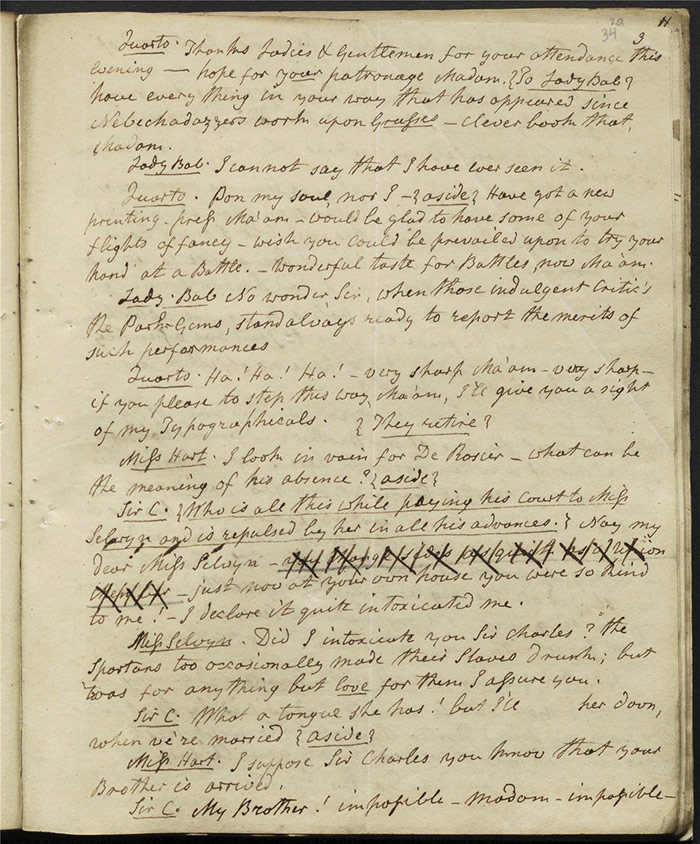

Quarto is drawing a lottery at the library when act 3 opens (f.33r). Sir Charles is discomfited to hear of his brother’s arrival in town. He decides that bribery might be the best way to keep the De Rosiers quiet. Miss Selwyn reiterates her admiration for Captain Canvas. A mix-up with some letters and communication means that Quarto thinks Lady Bab wants him to marry Miss Selwyn, much to the amusement of Susan and Davy (f.37r). La Fosse comforts De Rosier who has been turned out of his job by Quarto (f.39r). When Madame De Rosier arrives, La Fosse asks her where the bag the beggar (ie Hartington) gave her earlier. He discovers a £50 note in it to everyone’s delight.

Sir Charles Canvas solicits Hartington to tell Madame De Rosier that he will settle an annuity on her if she decamps along with La Fosse (f.42r). He reveals to Hartington that she has a secret that would open up his brother’s claim. Enraged, Hartington admonishes him and Sir Charles prepares to attack him. However, De Rosier stops him. Hartington thanks De Rosier and invites him to share his meal. Lady Bab and Quarto talk at cross-purposes: she about her treatise on ammonia and he thinking she has promised him her niece (f.44v). Lady Bab gets Davy to throw the impertinent Quarto out of her house.

De Rosier is surprised to find himself at Miss Hartington’s house, being led there in error by the indigent old man he has met (f.47r). Captain Canvas and Miss Selwyn declare their love to each other to a disbelieving Lady Bab and a disappointed Sir Charles. Hartington, no longer in disguise, then appears and reveals himself to Sir Charles and De Rosier. He tells the truth of Captain Canvas’s claim to the inheritance. Lady Bab changes her mind as to his merits. Miss Hartington and De Rosier are also united.

Performance, publication, and reception

The manuscript for M.P., or, The Blue Stocking was submitted on 22 August 1811 by Samuel Arnold of the Lyceum Theatre. The Examiner had a number of issues with the submitted manuscript and demanded revisions. We know this as the Larpent manuscript includes two folios of corrections at the beginning of the manuscript for a resubmission on 30 August. Anna Larpent read this version that same evening: ‘Also read a most absurd Opera the Bluestocking a sad contemptible Claptrap but in [Puns] [&] broad farce that makes one laugh past its absurdity yet one is ashamed at oneself for laughing at it’ (Anna Larpent Diary, vol. 8, f.120v). There is no mention of a meeting between Larpent and Moore, discussed below, in her diary.

The preface to the published version reveals that Moore challenged, unsuccessfully we may surmise, some of the cuts that were made by Larpent:

You will perceive, Sir, by the true estimate which I make of my own nonsense, that, if your censorship were directed against bad jokes, &c. I should be much more ready to agree with you than I am at present. Indeed, in that case, the ‘una litura’ would be sufficient (MP, iv).

It is unclear whether Moore’s objections were made in relation to the first or second submission of the manuscript.

The first performance was on 9 September: given the gap between the second submission and the performance, it may be that Moore wrote his letter of objection in response to lingering concerns of Larpent (ie after 30 August). It is more probable that he wrote to respond to the initial concerns (ie before 30 August). In any case, the situation was far from the vitriolic case of Hook’s Killing No Murder as Moore was at pains to compliment the Examiner’s ‘politeness and forbearance with which he attended to [Moore’s] remonstrances’ (iv).

The preface also pays particular attention to the ‘elaborate criticisms’ expressed by The Times (10 September 1811) and the Examiner (15 September 1811). The review in The Times was detailed and excoriating, attacking the plot, characters, morality, music, and songs of the piece. The conclusion of the piece reveals that Moore’s Whiggish (and pro-Regency) politics had a part to play in the downbeat assessment:

We must repeat to Mr. MOORE, and he seems to require the repetition, that if wit be desirable, it is not so at the expense of decency; and that, though loyalty be perfectly becoming, there can be nothing more utterly degrading to the spirit of poetry, more offensive to rational minds, or more totally opposed to every feeling which an honourable and high-hearted man should labour to cherish in himself, than adulation of Princes on the throne, or in sight of the throne.

The author of the piece in the Examiner was, if anything, more damning. However, the journalist is at pains to point out that Moore distanced himself from The M.P. in a letter to the Sun, describing the comedy as a ‘bagatelle, which has been received much more indulgently than it deserves’. The article also reprinted a letter from Samuel James Arnold, manager of the Lyceum, which insisted on the rapturous reception The M.P. got from audiences. Certainly, the play was a considerable commercial success with multiple performances through September and into October. A more positive review can be found, unsurprisingly, in the Whig-leaning Morning Chronicle (10 September 1811). It emphasized the light ambition and satirical deftness of Moore in the most glowing of terms while flagging the comedy’s political raciness:

The words of his tender songs play round the heart with the finest emotion; and it is here that our British Anacreon is without a rival. His delineation of character is sprightly, and in the character of the M.P., unusually bold. We were struck with astonishment at the flashes of satyrical merriment which the eye of the licencer (generally so jaundiced) had passed over without an objection.

Finally, we might note that Moore’s success was celebrated in the Morning Chronicle (21 September) by an Irish patriot. Hyde Mathis Browne, a regimental surgeon, contributed ‘Erin, A Song’ (sample line ‘Give [Erin’s] Sons but their due! undisturb’d, unconfin’d / And let Erin and Albion each other embrace’). Browne references a song sung by Mr Phillips, who played De Rosier, as his inspiration. This song is almost certainly the patriotic paean to England and its liberties sung by De Rosier in the third act.

Moore’s own private assessment of his experience was mixed. He was unimpressed with the temperament of the theatrical audiences as he described in a letter to Lady Donegal (17 August 1811):

I think there is not in the world so stupid or boorish a congregation as the audience of an English playhouse. I have latterly attended a good deal, and I really think that when an author makes them laugh, he ought to feel like Phocion when the Athenians applauded him, and ask what wretched bêtise had produced the tribute. (Memoirs, I: 257-8)

Yet however the success of the piece grew on him and he wrote to her again some weeks later (28 October 1811) to announce that M.P. was now going to be played outside of London: ‘My opera has succeeded much better than I expected, and I am glad that [John] Braham is going to play it at Bath; but I have been sadly cheated. What a pity that we “swans of Helicon” be such geese!’ (Memoirs, I: 262)

The comic opera was printed by W. Clowes for J. Power in October 1811.

Commentary

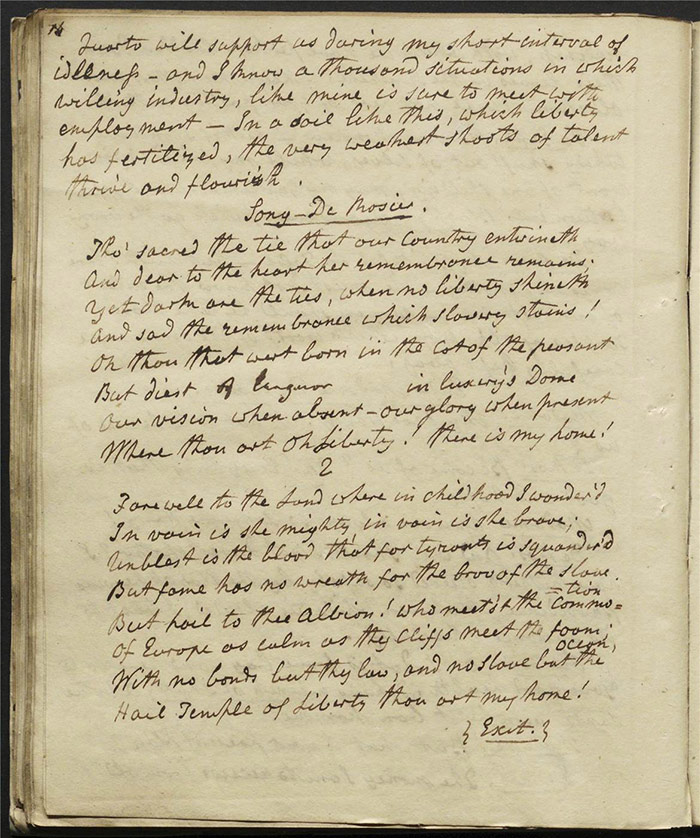

The manuscript (LA 1688) shows a number of emendations and excisions marked both in pen and pencil. It is unclear whose hand is at play here but we might hazard that the penciled underlining is by Larpent.

Evidently, the regency is the key context for understanding Moore’s intentions with this play and the Examiner’s response. The regency had commenced in February 1811, an event which the Whiggish Moore celebrated. He attended a grand fete on 19 June at Carlton House to celebrate the Regent’s inauguration and did not leave, he wrote to his mother, until after six o’clock in the morning. Moore’s language, as he describes the scene in the letter, invites us to read the play in a jubilant, indeed triumphant, Whiggish tone: ‘Nothing was ever so magnificent; it was in reality all that they try to imitate in the gorgeous scenery of the theatre’ (Memoirs, I: 254-5).

Moore’s triumphalist tone is indicative of the general tenour of Whiggish hopes that the Regent would replace his father’s Tory government under Spencer Perceval. The party political tension in the capital during the composition and staging of M.P. helps explain Moore’s motives and indeed the Examiner’s caution when it came to the many references to parliamentary life that caught his eye.

Turning to the manuscript, what is helpful here – and relatively unusual – are the pair of inserted folios which contain dialogue, copied from the main manuscript, marked for excision. The writing is almost certainly Larpent’s so it appears these pages are a summary of his cuts, compiled for the theatre’s convenience. What is confusing, however, is that the emendations marked on these initial folios (some lines are marked for excision in pen, some are left as is) do not always correspond with those made in the play-text proper. We might speculate that these summary folios then provided the basis for Moore’s discussion with the Examiner, referred to in his preface to the published version, over the fitness of his play for public consumption and it may be that the lines not crossed out here on the initial folios were restored.

The first cut seems fairly innocuous: ‘Two strings to my Bow, as Lord Either says in the House’ (f.6r); this line was underlined emphatically in pencil and crossed out in pen. It may be that this is simply a generic lord but it may be more probable that the lord referenced was identifiable to a Georgian audience, through the two strings to his bow reference. In any case, the line is crossed out in pen in the main text and in the summary folios.

On (f.26r) we have a comment from Sir Charles casting aspersions on politicians when he says ‘just the way in the house tho’ – when a Member arrives at a Post, he always vacates his Seat immediately’. Here we have the words ‘Post’ and ‘vacates’ underlined in pen to indicate emphasis (they appear italicized in the published version, as does ‘seat’). The whole line is underlined in pencil but rather faintly. In this instance we have no material struck out in pen on the folio but the line is unscathed on (f.i). Quite fascinatingly, the same folio has a speech from Sir Charles, after his carriage crashes, with an explicit reference to Lord Grey, leader of the Whig opposition: ‘Not much [injured] Ma’am - head a little out of order as we say - all owing to the spirit of my leaders – Greys – Madam – fine creatures – your Greys make excellent leaders in opposition coaches’. It is surprising, as the Morning Chronicle noted, that Larpent allowed this through.

The remaining excisions in the play all follow the same political tenour: ‘you change sides as quick as a union member’ (f.34r) is crossed out in pen, underlined in pencil. The cut on (f.35v) is partially illegible but, as Moore restored it in the published version (p.66), it is a reasonably safe assumption that we can render it accurately:

I’ll try bribery – I will – they are poor – and a bribe will certainly stop their mouths – besides it will keep my hand in and make me a more saleable article myself in future – for nothing breaks a man in for taking bribes so effectually as giving them.

I will eschew a fuller description of the complex pencil and pen markings and interlineations here as the image should be consulted. But a comparison between this folio with (f.i) is suggestive as it would appear – assuming one accepts the thesis that Moore negotiated back some lines – that the first reference to a bribe was passed (perhaps because it was directed at a poor man?) and that is was when the taking of bribes was associated with the titled Sir Charles that it became problematic.

A couple of other interventions on political grounds should be examined on (f.42r) and (f.48r).

Further reading

Geoffrey Carnall, ‘Moore, Thomas (1779-1852), poet.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/19150, accessed 31 January 2019]

Christopher Hibbert, George IV Regent and King 1811-1830 (London: Allen Lane, 1973), 1-15.

Ronan Kelly, Bard of Erin: The Life of Thomas Moore (Penguin, 2008), 197-200.

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library, HM31201 vol. 8, f.120v

Thomas Moore, MP or The Blue-Stocking (London: Printed by W. Clowes for J. Power, 1811).

[available on HathiTrust.org]

John Russell (ed), Memoirs, journal, and correspondence of Thomas Moore, 8 vols. (London: Longmans, 1853-56).

[available on HathiTrust.org]