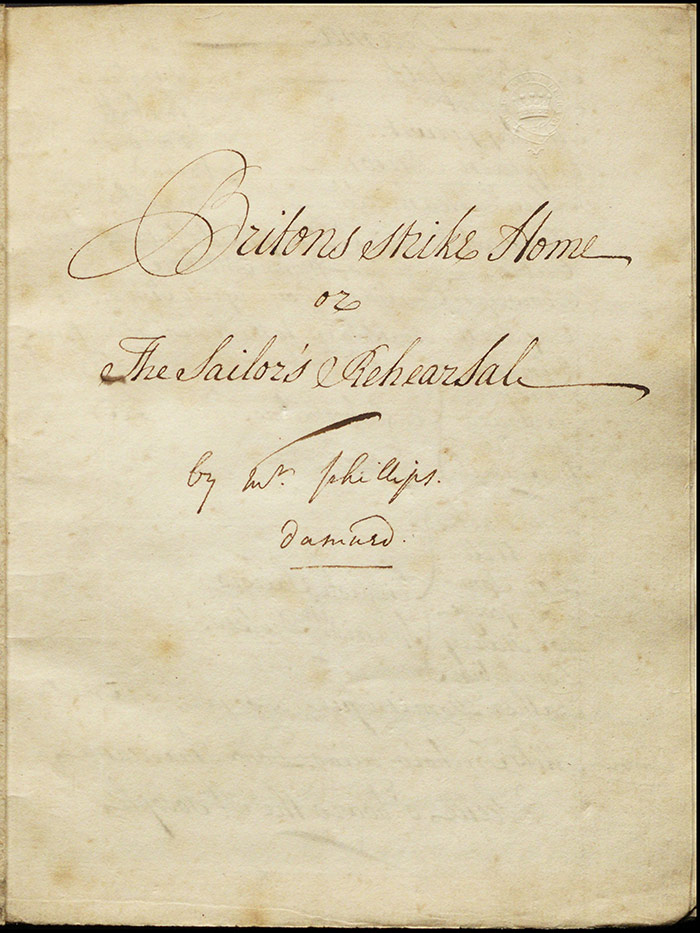

Britons Strike Home (1739) LA 16

Author

Edward Phillips (b. 1708/9)

Phillips was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge. He had a long association with John Rich and Covent Garden and his first success was a ballad opera afterpiece The Mock Lawyer (CG, 1733). A burlesque of an actors’ rebellion at Drury Lane, led by Theophilus Cibber, titled The Stage Mutineers; or, A Playhouse to be Let followed that same year. Phillips continued to write with an eye on current events, producing a The Nuptial Masque, or The Triumphs of Cupid and Hymen (1734) which celebrated the marriage of Anne, the princess royal. He then wrote some scenes to accompany Covent Garden’s depictions of Queen Caroline’s new Hermitage at Richmond Lodge in 1736. That same year saw the unsuccessful production (one night only) of Marforio (CG), an attempt to counter the enormous success of Fielding’s Pasquin (DL, 1736), a play to which Macklin’s Covent Garden Theatre (1752) was also a response. Britons Strike Home; or, The Sailors’ Rehearsal, performed in December 1739 (CG), was Phillips’s final contribution to London’s theatre, inspired by Henry Purcell’s stirring patriotic air of the same name from 1695.

Plot

The published version contains a prologue and epilogue (see further reading).

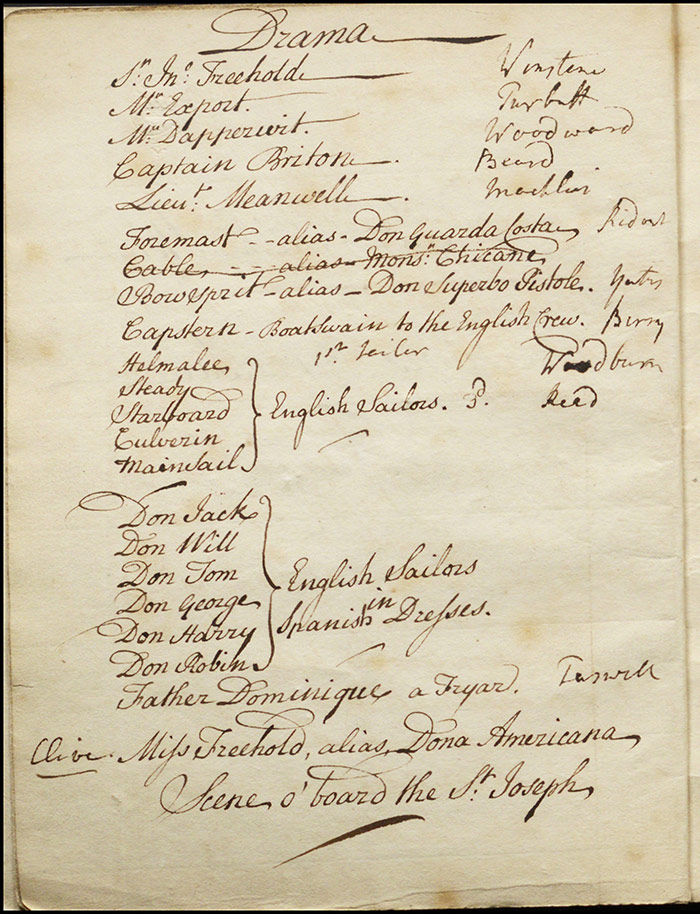

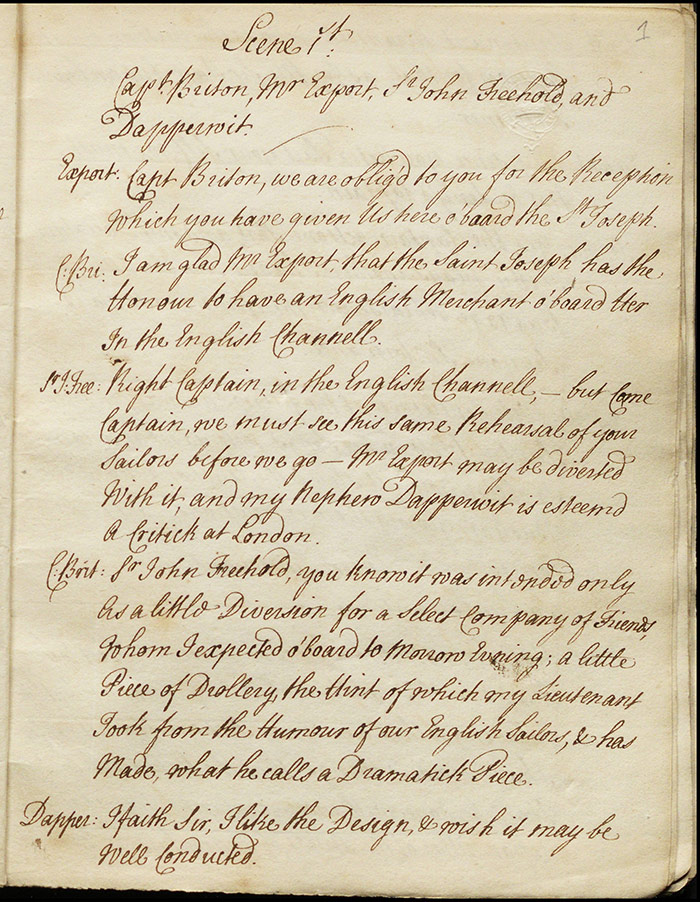

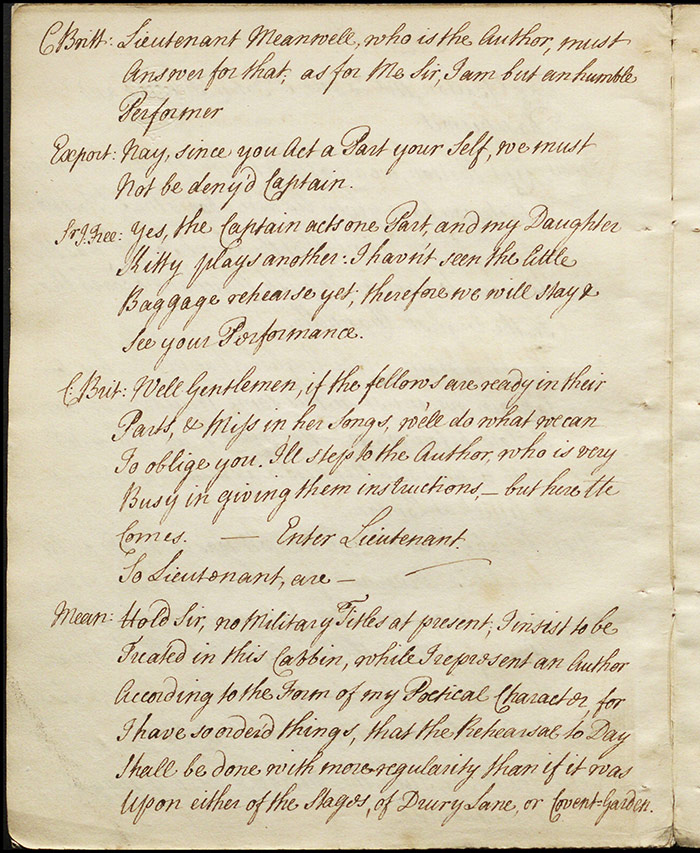

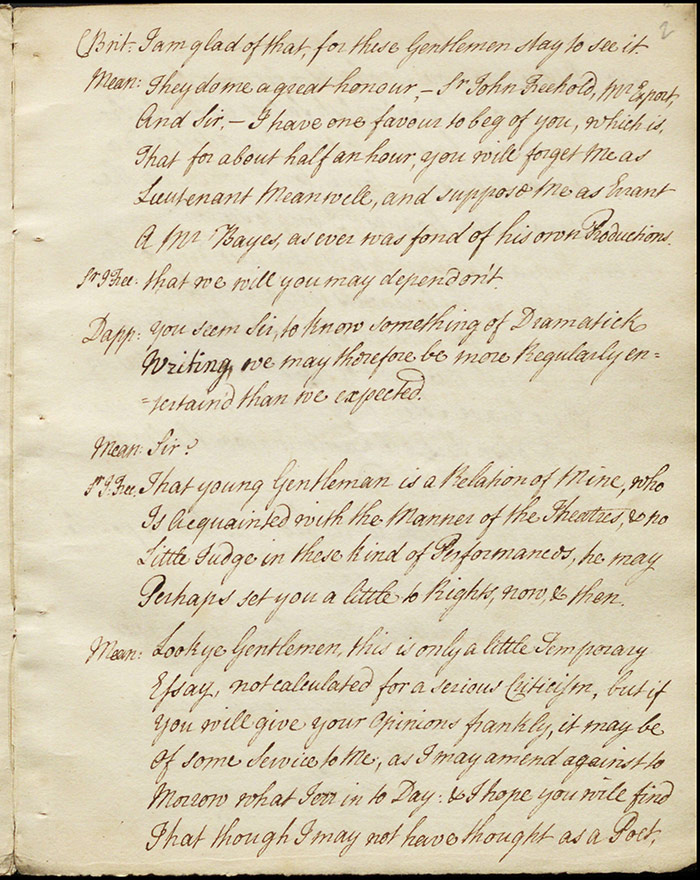

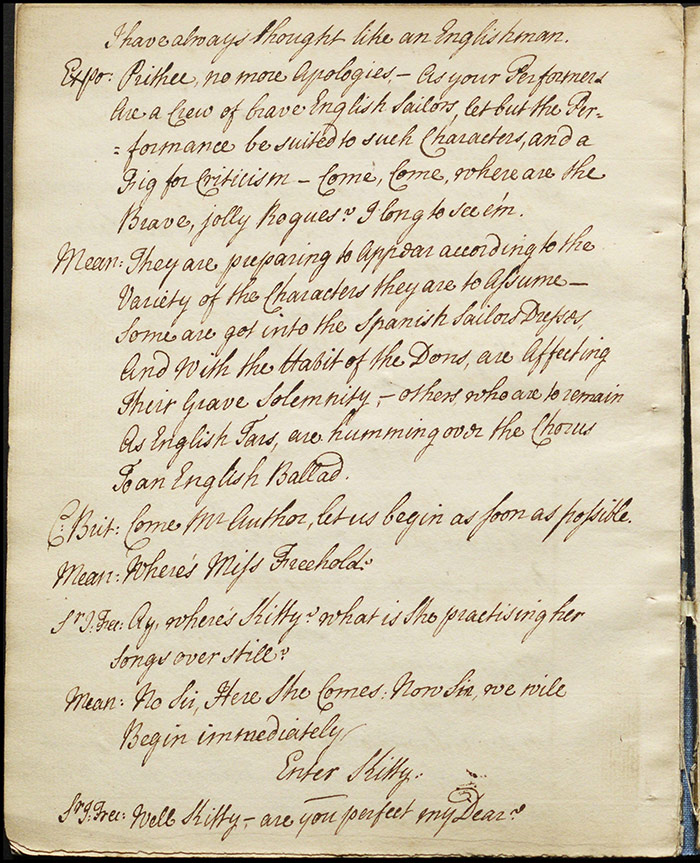

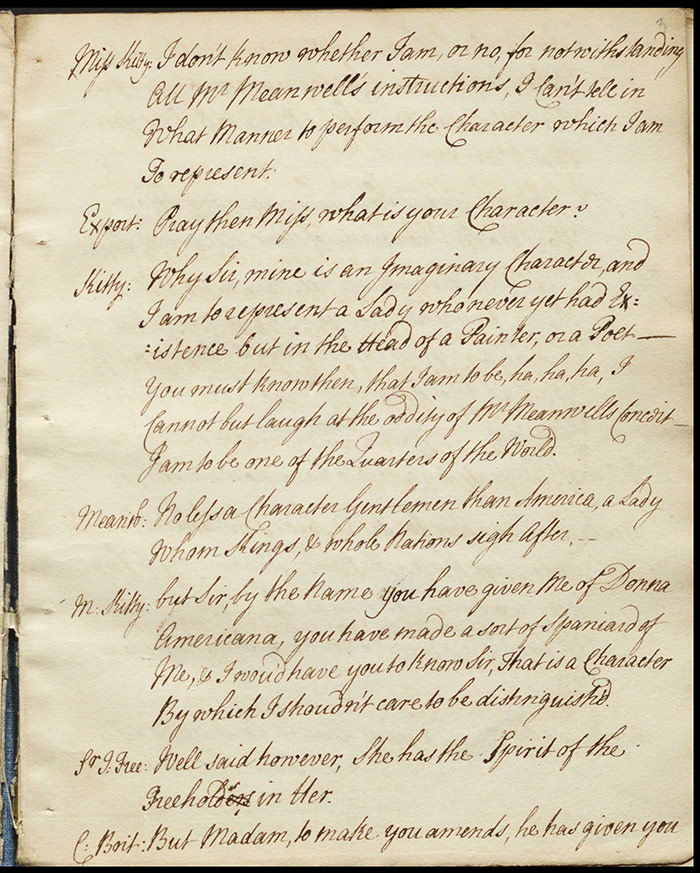

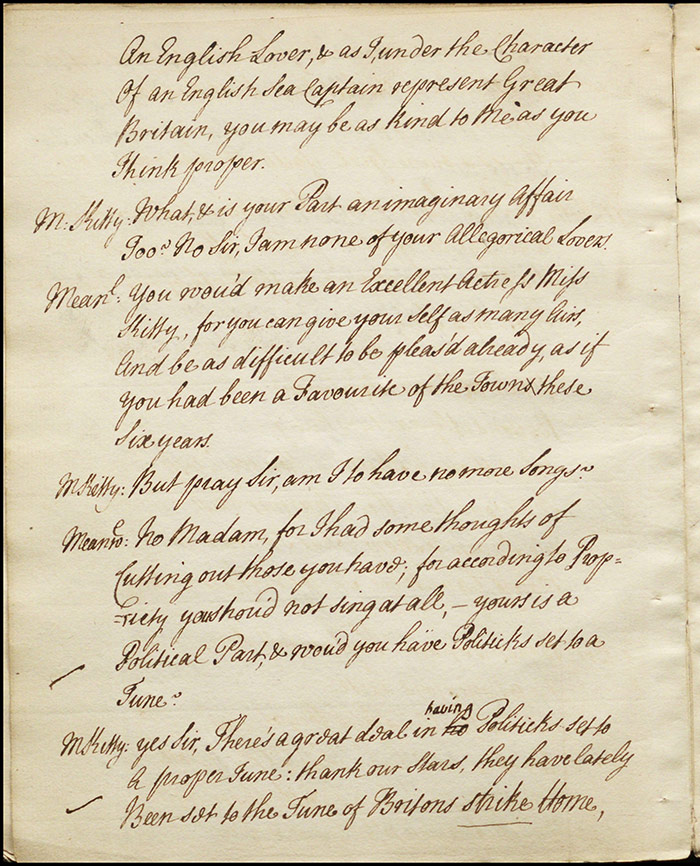

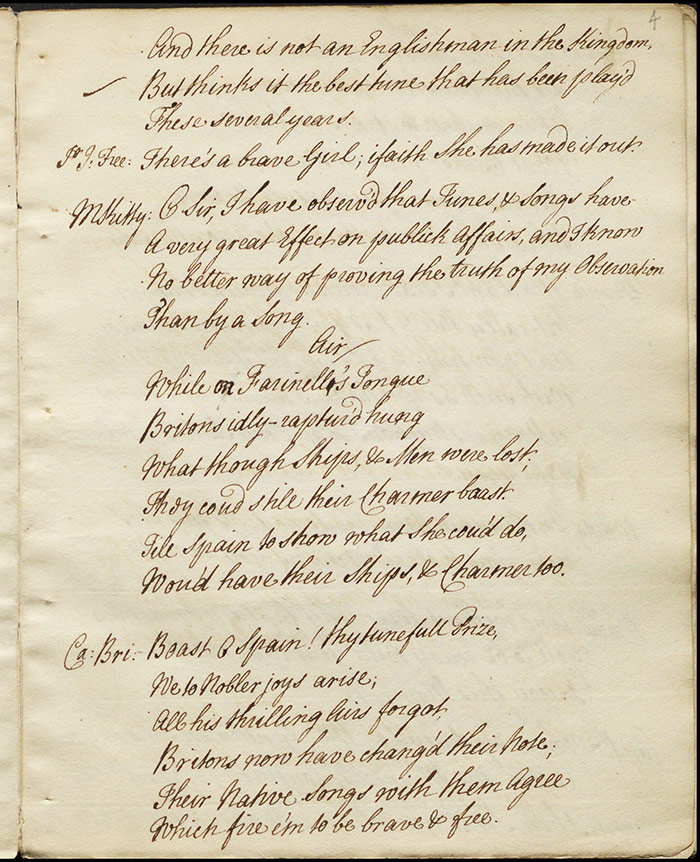

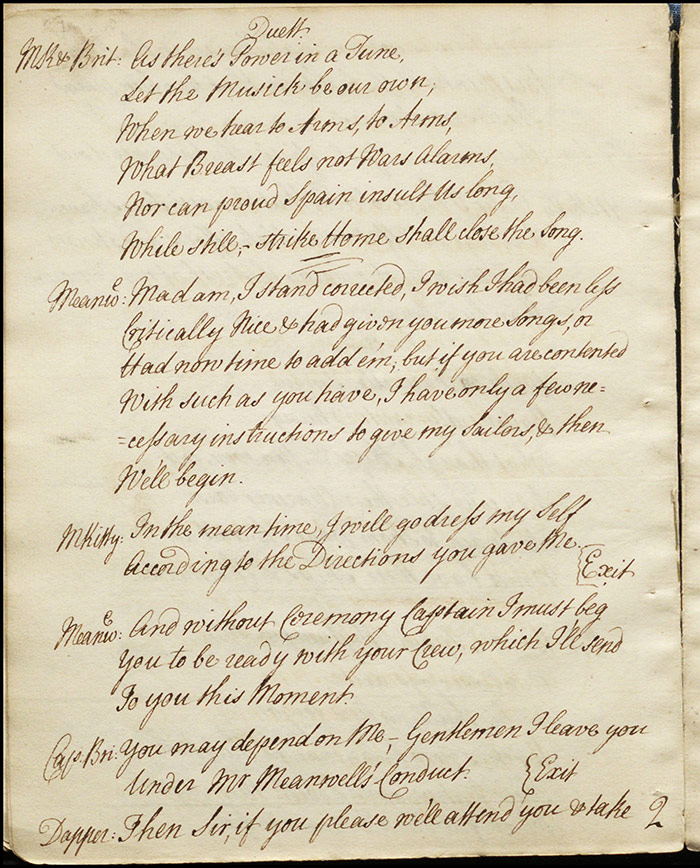

The action takes place on the St Joseph, a British warship in the English Channel. Captain Briton is hosting Mr Export, Sir John Freehold, and his nephew Dapperwit. The crew are planning a dramatic entertainment for some friends of the Captain who are visiting tomorrow but Sir Freehold asks can they see the sailors’ rehearsal before they go as Dapperwit, his nephew, is ‘esteemd a Critick at London’ (f.1r). The Captain—who is playing a part along with Sir John’s daughter, Kitty—agrees. Lieutenant Meanwell, the author of the piece, enters and is pleased to learn of the new audience. On being told that Dapperwit is a critic, he emphasizes that this is an amateur production and we learn that some of the sailors will be dressing as Spaniards and others as English tars. Kitty enters and admits she is a little nonplussed at the abstract nature of the character she’s to play, Donna Americana ‘a Lady whom Kings, & whole Nations sigh After’ (f.3r). Moreover, she is not terribly keen on the Spanish connotations either. Captain Briton tries to reassure her by reminding her that his character, an English sea captain, is her lover. She turns her attention to Meanwell and asks that he provide more songs for her part. Meanwell dismisses her request as she has a ‘Political Part’ (f.3v) but she wins him round with her singing. Kitty exits to get dressed for the performance. They hear the sailors singing and they all exit to watch the rehearsal.

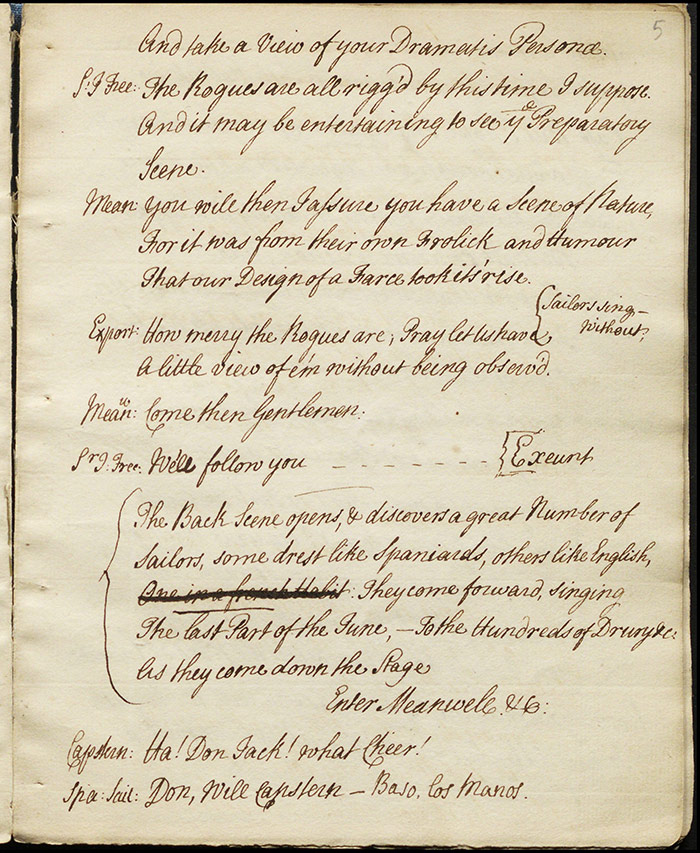

The scene opens with the crew just finishing a song (f.5r). They are dressed as English and Spanish sailors and playfully exchange some words, also in character, much to Meanwell’s chagrin as he feels they are disclosing the substance of his drama. Export and Sir John are impressed by their lusty patriotism and cheer the sailors as essential bulwarks of trade and liberty. Dapperwit, on the other hand, suggests there might be political objections to the allegorical drama.

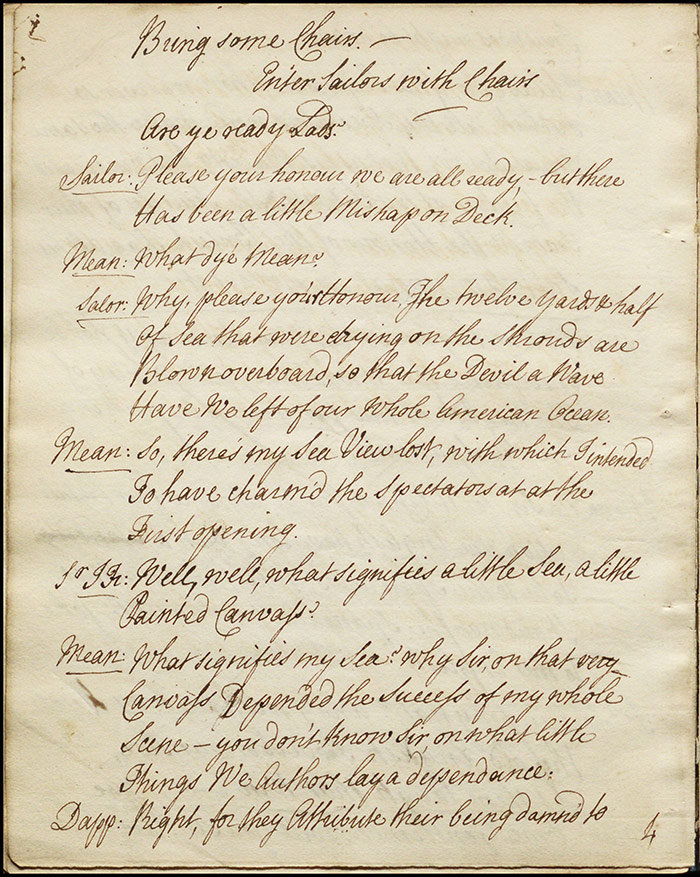

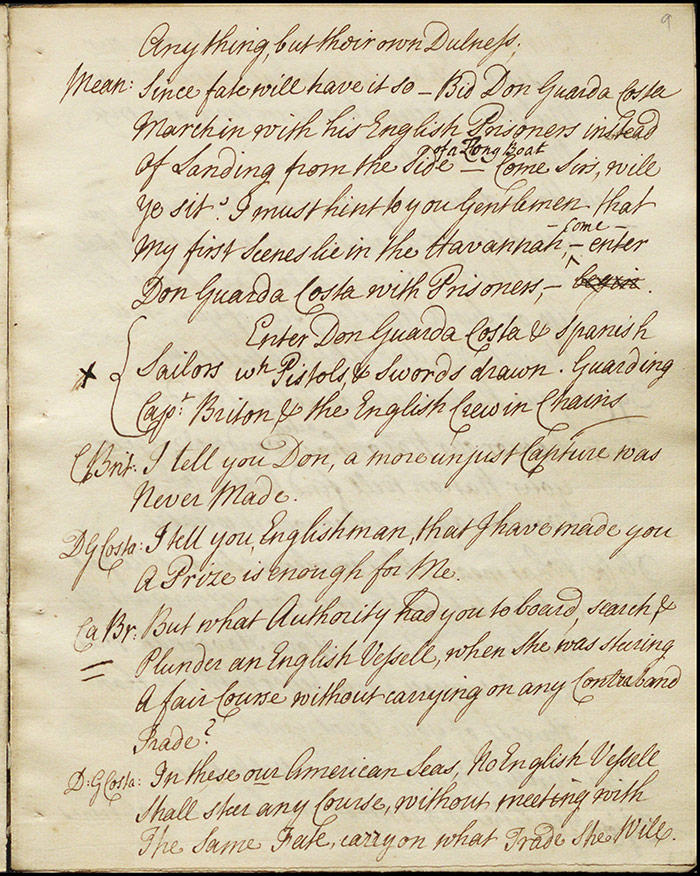

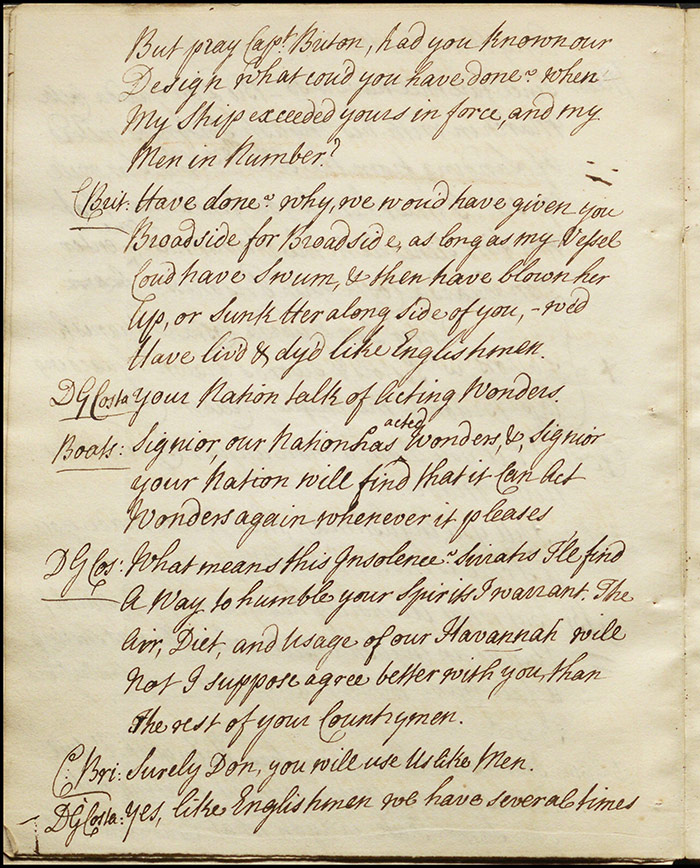

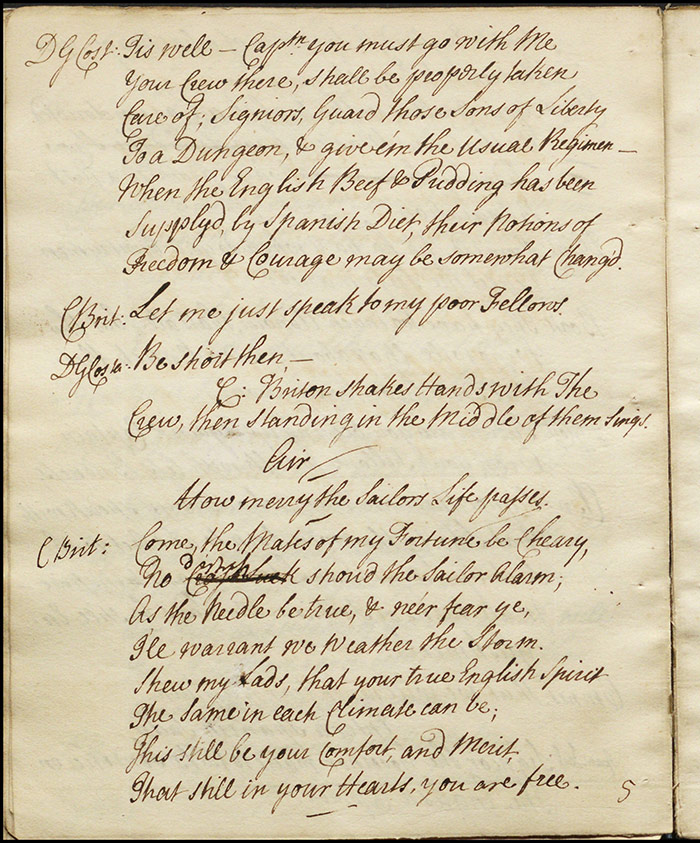

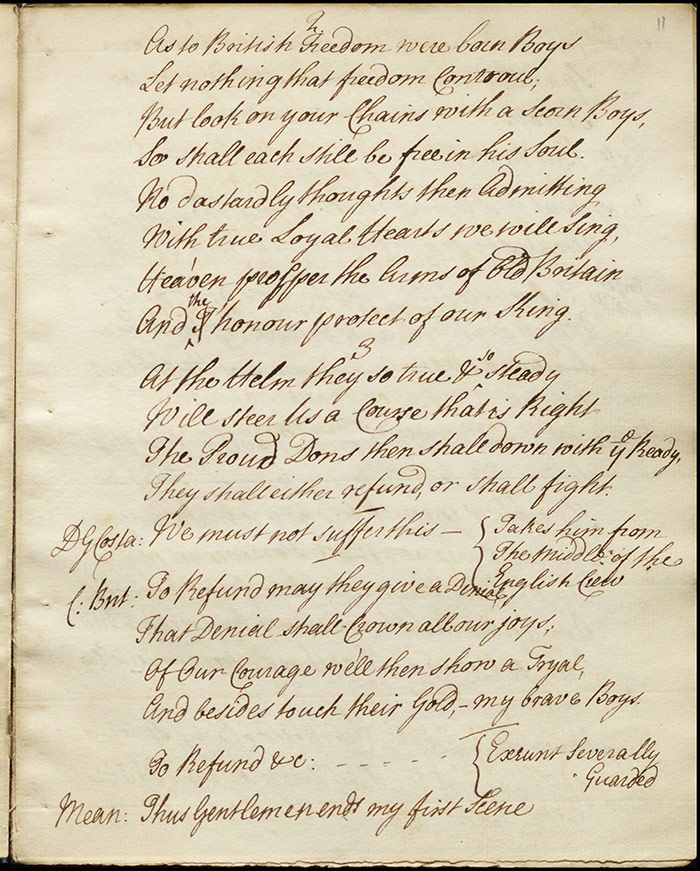

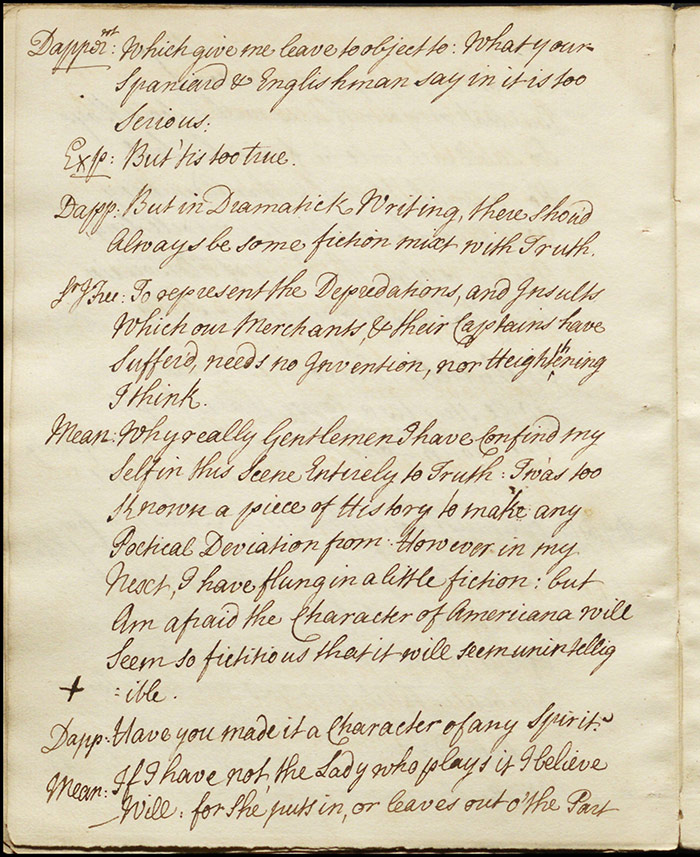

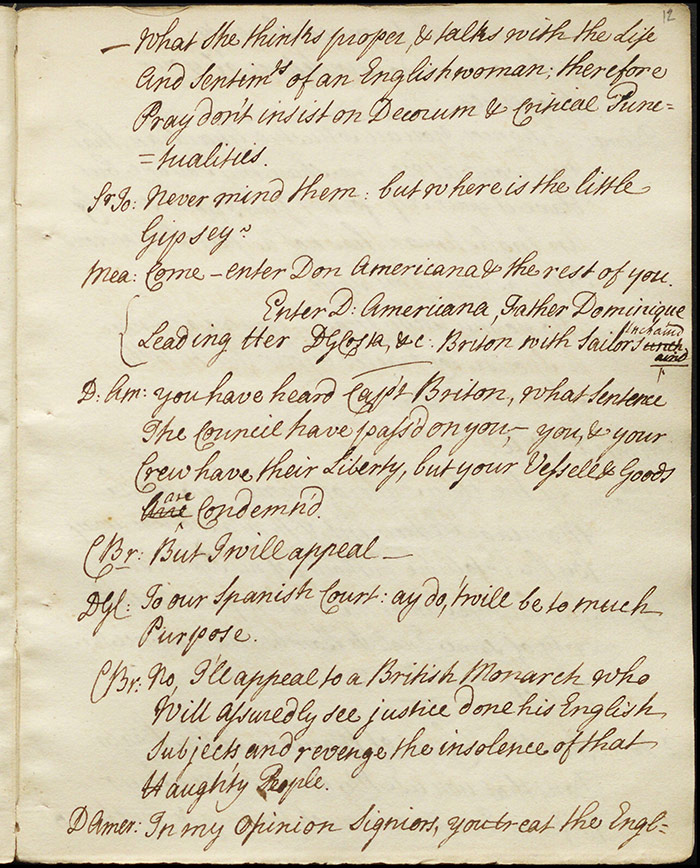

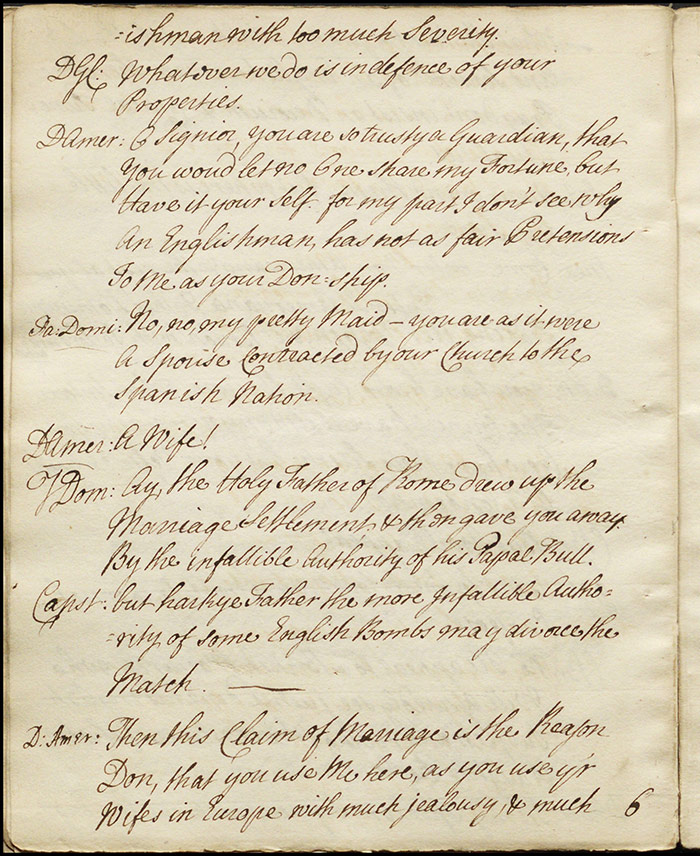

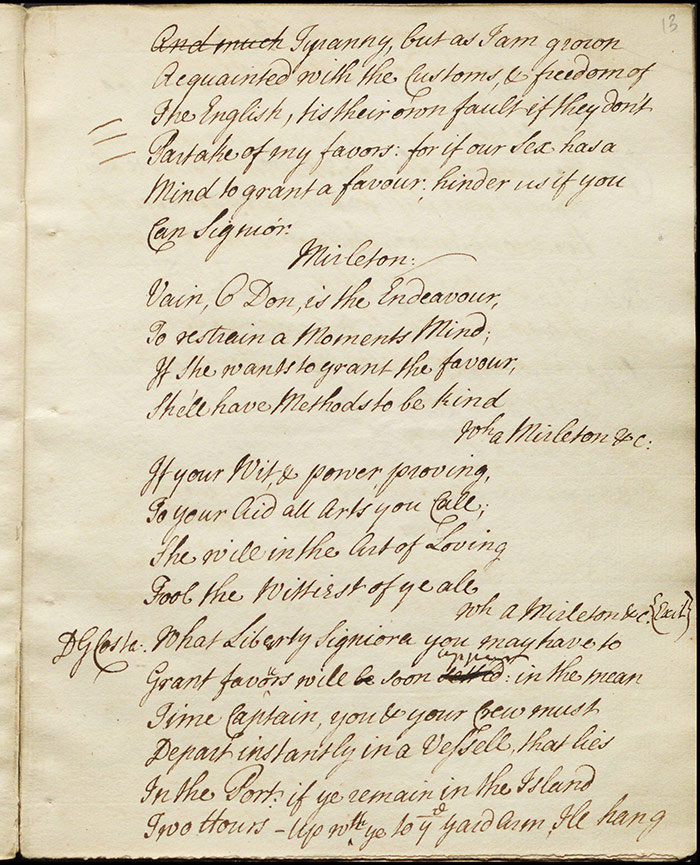

A sailor then enters to announce that the stage backdrop representing the sea has fallen over board which forces Meanwell to reorder his drama. He then orders a scene in which Captain Briton and his sailors are held captive by Don Guarda Costa to commence. The exchange between the two parties celebrates English stoicism, courage, and liberty and highlights Spanish perfidy, ending with a defiant song from Captain Briton and his crew. Meanwell turns to the guests for reaction and Dapperwit again repeats his political objections and insists ‘But in Dramatick Writing, there should Always be some Fiction mixed with Truth’ (f.11v). Meanwell announces a second scene with Donna Americana in it and promises, if anything, this will have too much fiction in it. In this scene, Donna America argues with Don Guarda that she has a right to have a liaison with the English, as well as the Spanish. The scene ends with Don Guarda ordering the expulsion of the English under threat of hanging to which the sailors respond with a rousing song.

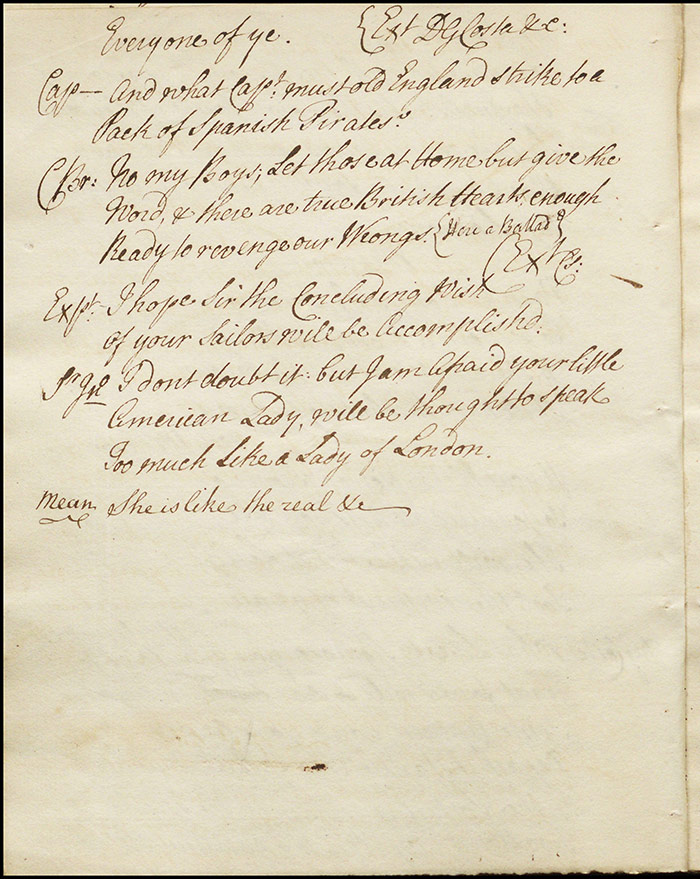

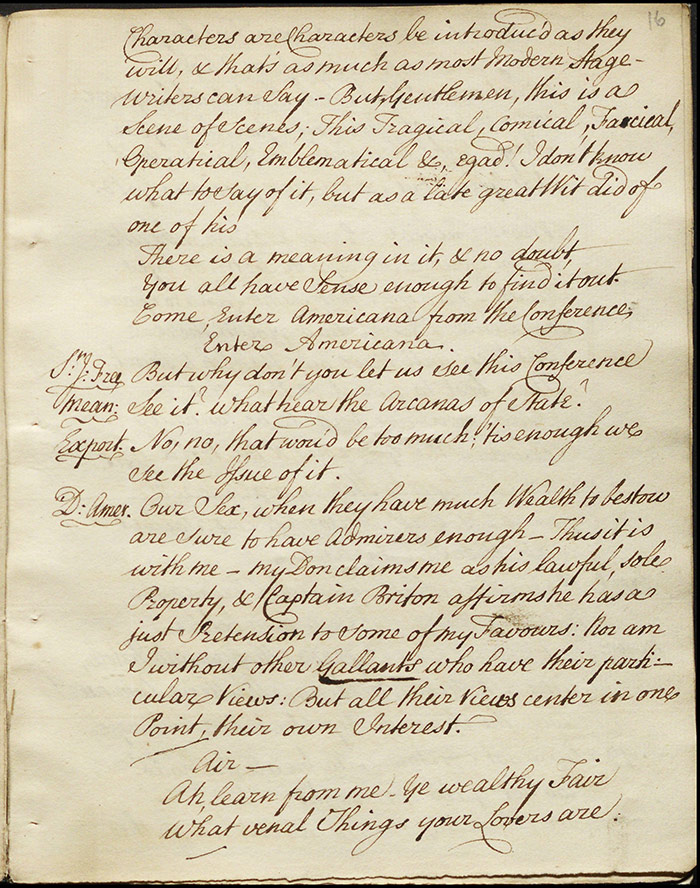

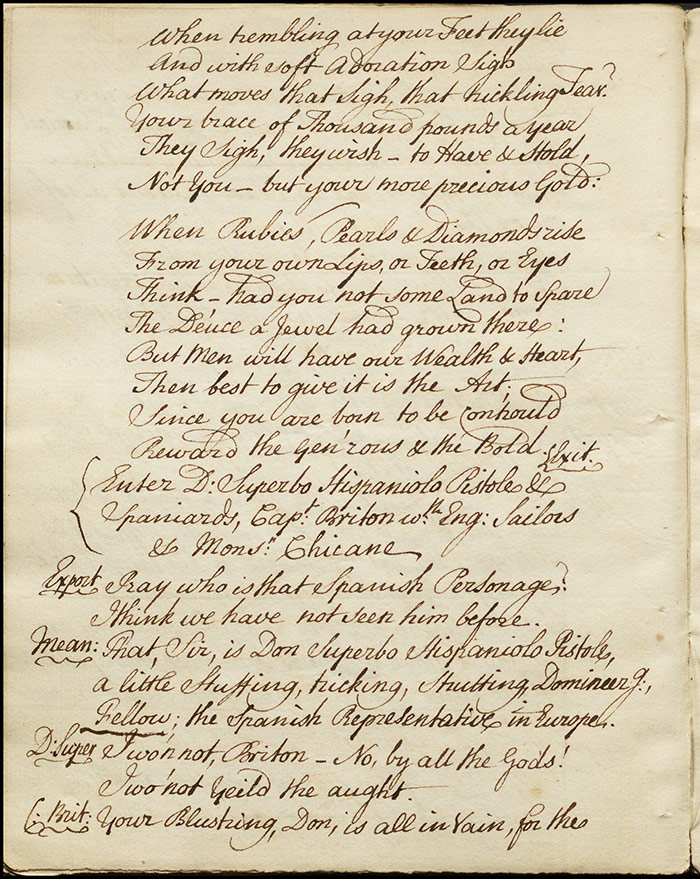

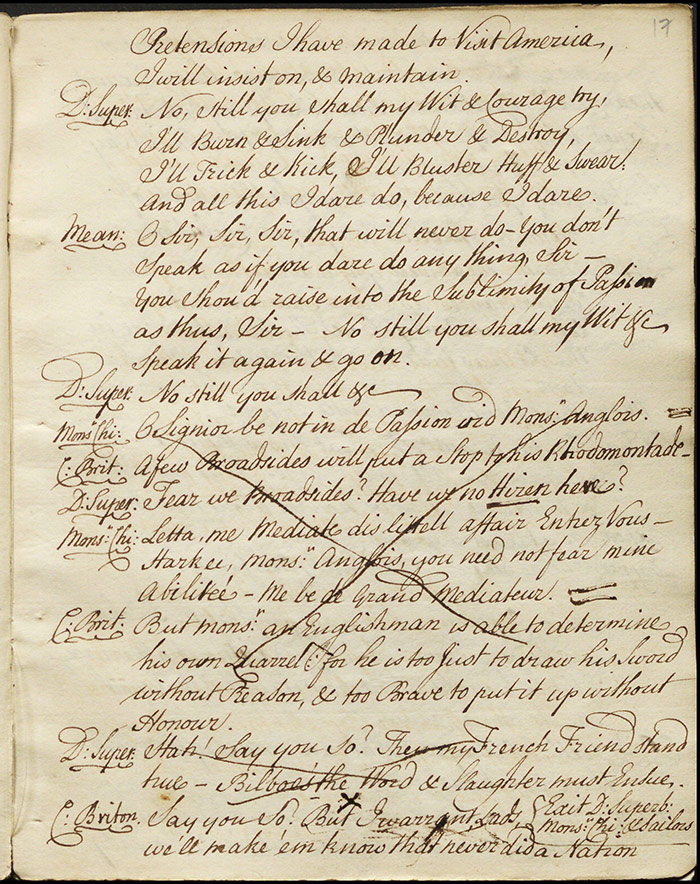

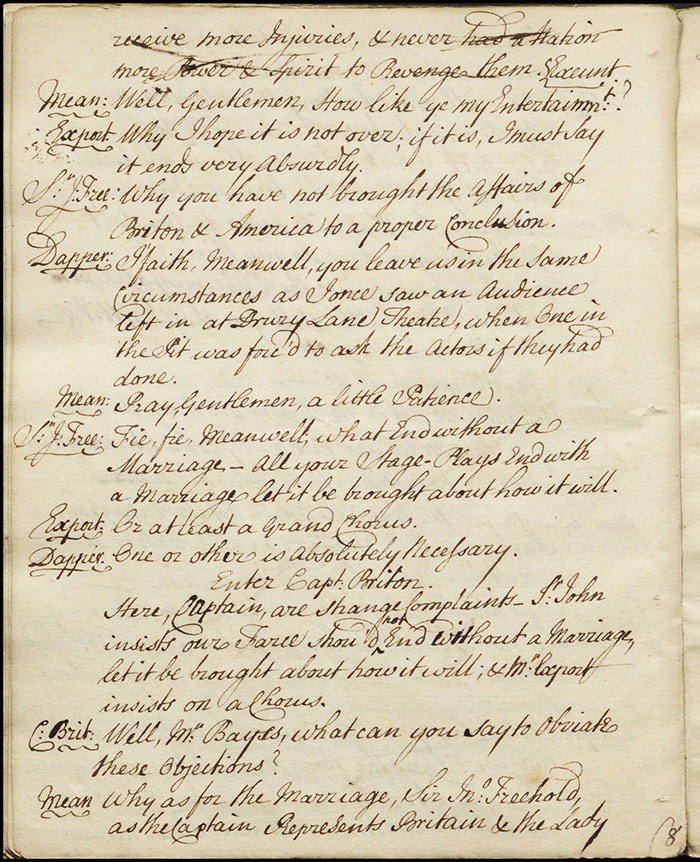

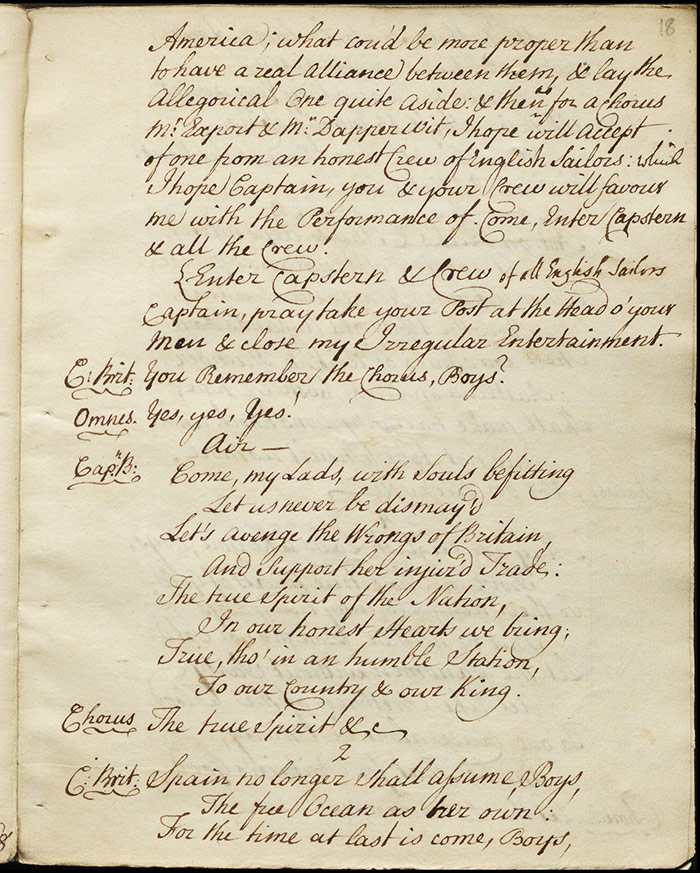

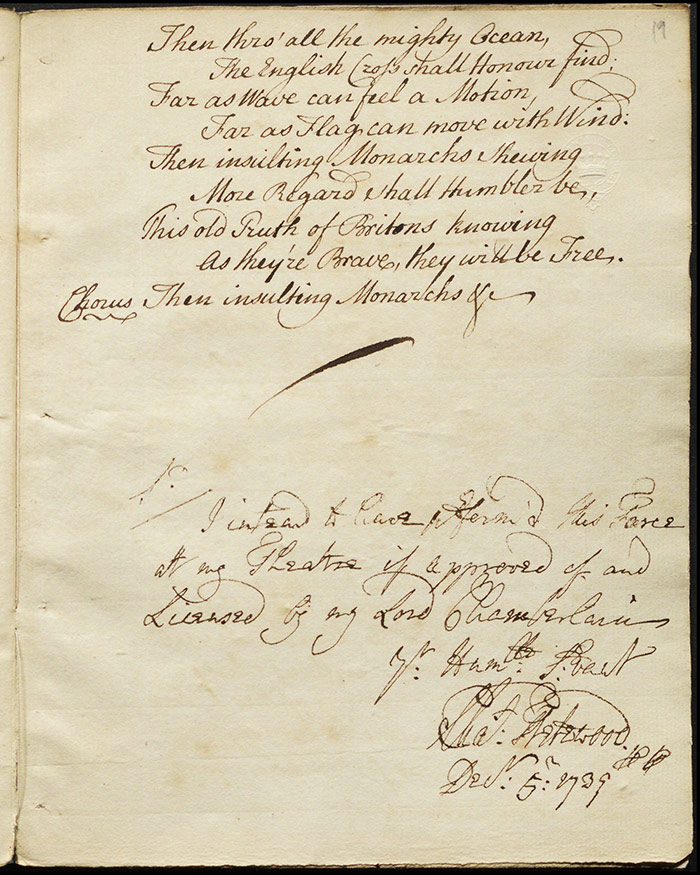

The next scene is announced by Meanwell as taking place in Europe with the Spanish being boarded by English, although Dapperwit is disappointed that an opportunity to show a battle has been passed up (f.14r). The English sailors search a Dominican friar who is found laden with gold. Again, Dapperwit finds fault with the dramatic logic of it but Meanwell dismisses his objections and introduces another scene. This final scene consists of a heated exchange between Captain Briton and Don Superbo Hispaniolo Pistole, concluding with a hearty song where Briton and his crew promise to protect British trading interests (f.16v). The abruptness of the ending upsets his audience and they suggest that the piece should end with a marriage or a grand chorus in line with other plays. Meanwell rebuts energetically that as Captain Briton represents Great Britain and the Lady, America, a real alliance would ‘lay the Allegorical one quite aside’ (f.18r). A defiant chorus concludes the action.

Performance, publication, and reception

The play was performed on 31 December 1739 at Drury Lane. The 1-act afterpiece was offered alongside John Hughes’s The Siege of Damascus (1720). It was not repeated and the title page of the manuscript is marked ‘damned’. We might also note that Charles Macklin plays the part of the author character, Meanwell: his Covent Garden Theatre, included in this resource, was also inspired by Buckingham’s The Rehearsal.

The context for the play was the War of Jenkins’s Ear (1739-1748), a Spanish-British conflict sparked by trade disputes in the Caribbean between the two countries. The popular name for the conflict stemmed from an incident off the coast of Florida in 1731 when a Spanish vessel boarded a British ship suspected of breaking a trade agreement. The Spanish captain cut off his opposite number’s ear and is said to have threatened to do the same to the British king. In March 1738 Captain Jenkins testified to a parliamentary committee and, in some accounts, produced his ear—or something he claimed to be his ear—to the presumably startled parliamentarians. Diplomatic relations worsened and war was declared on Spain on 23 October 1739. Phillips then had a firm weather-eye on events at a time ‘when the Spirit of every Briton is rais’d by their Hopes of humbling Spain, and revenging the Wrongs of their Country’ as one correspondent to the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal (29 December 1739) put it.

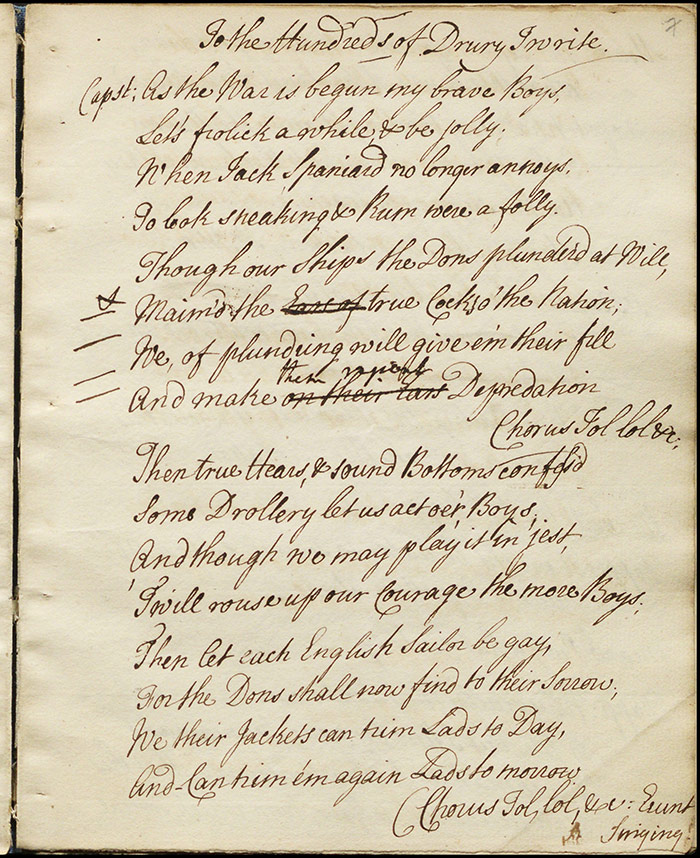

Patriotic sentiment was certainly in the air and the eponymous song of the afterpiece had already appeared that season in The Alchymist (DL, 24 October 1739), The Necromancer (CG, 30 October 1739), and—rather appositely—in The Rehearsal (CG, 31 October).

There is a possible—albeit cryptic—reference to the afterpiece in Henry Fielding’s The Champion (3 January 1740). Fielding writes that ‘the Capture of the Ship St Joseph is the only Article of Importance [the war] has produced’ (157). There is no mention of any ship with that name in the newspapers for December-January 1739-40 so Fielding may be referring to Phillips’s play, a theory given some credence by the proximity of the dates of the performance and the newspaper.

Commentary

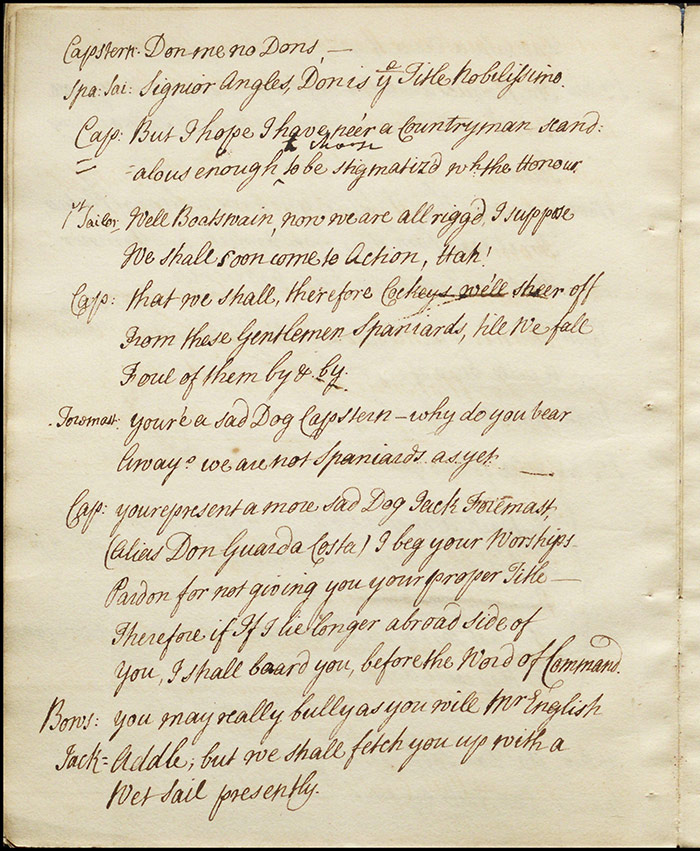

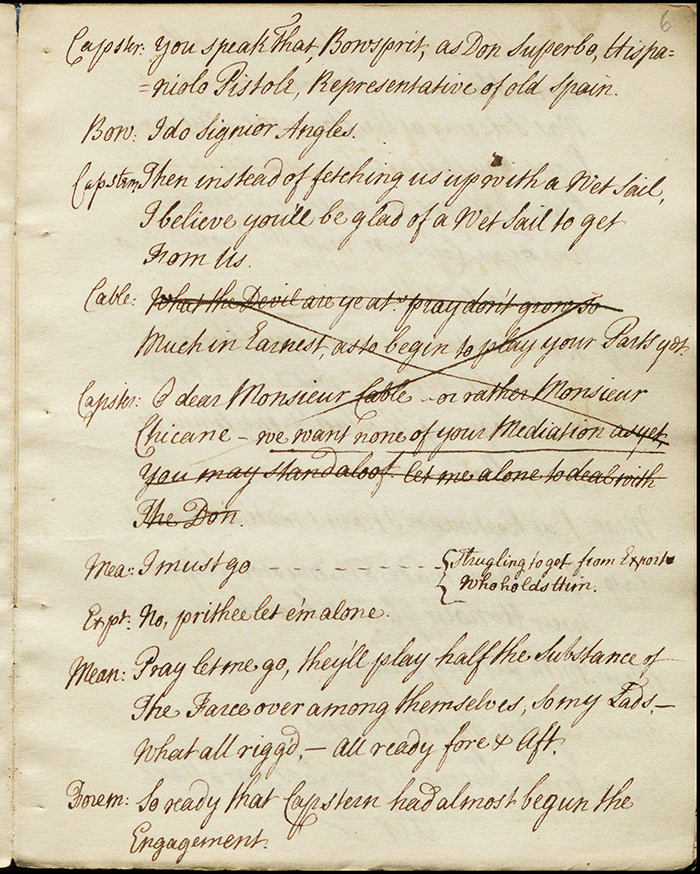

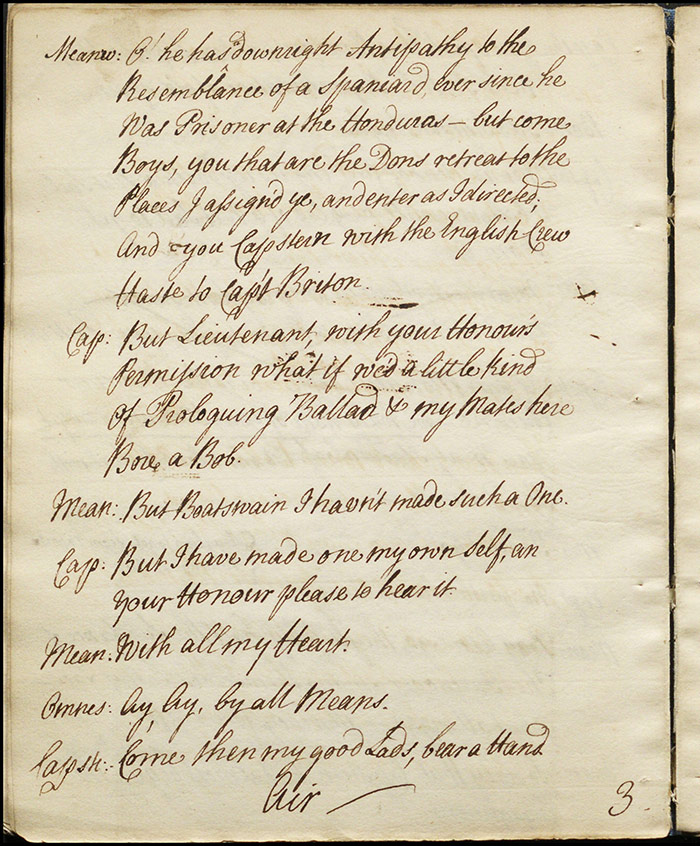

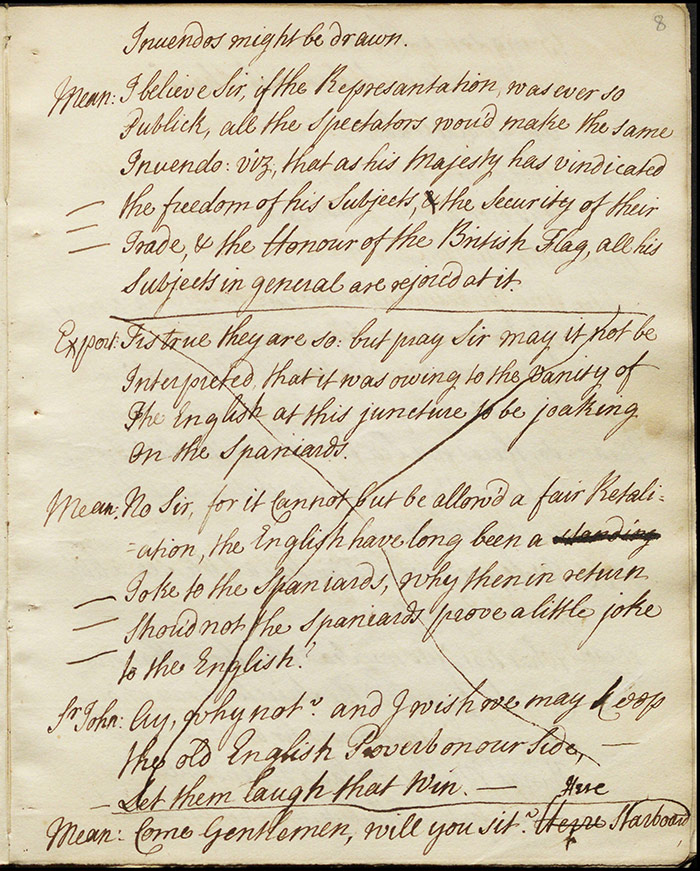

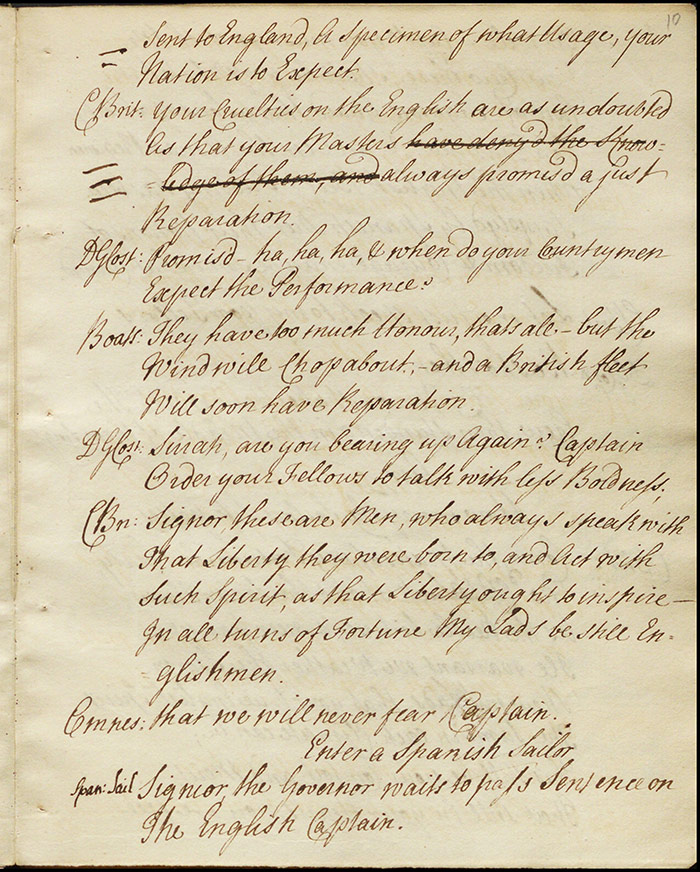

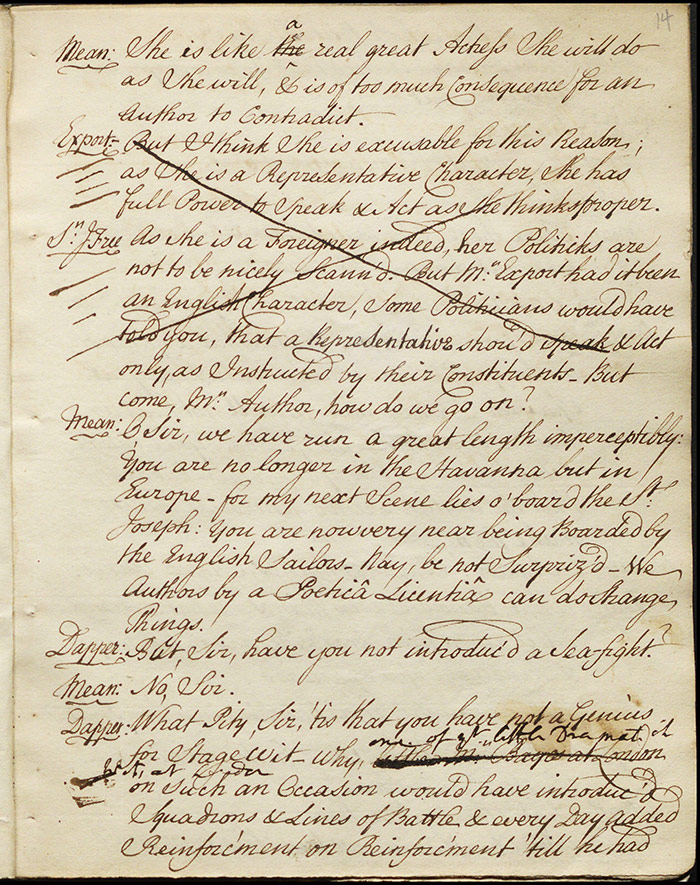

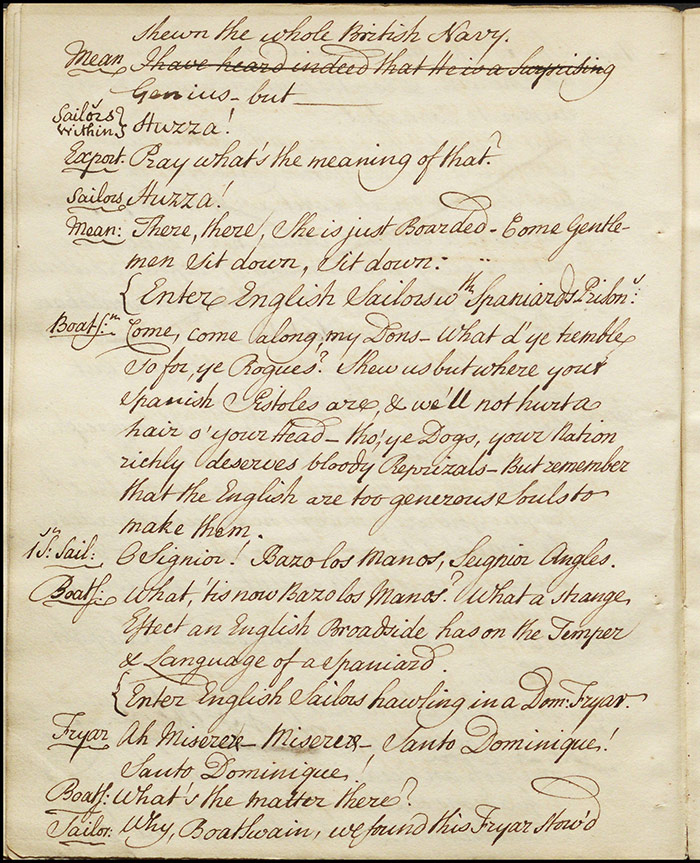

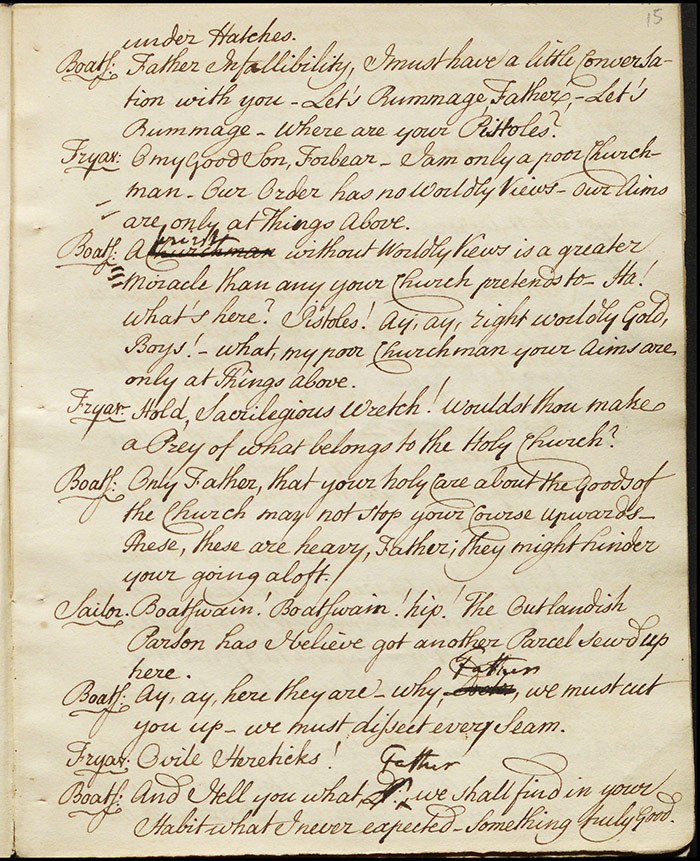

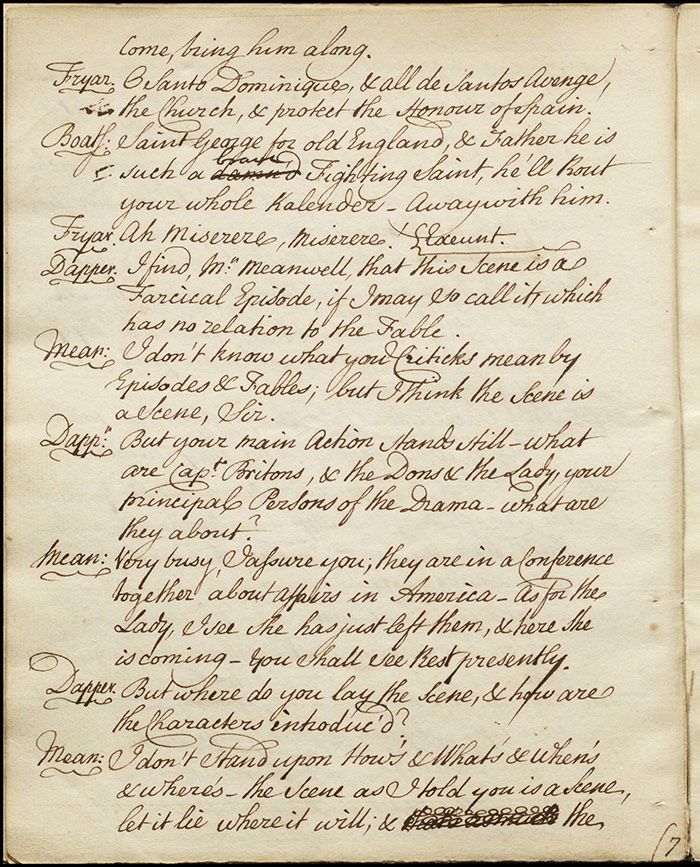

The manuscript (LA 16) shows a number of emendations and excisions marked in pen. Both authorial/managerial and Examiner edits are in evidence. We can speculate with a degree of confidence that the passages marked in the margin with dashes (single, double, and triple) are those marked by the Examiner (Chetwynd). Passages crossed out with a large ‘X’ and with additional text inserted seem likely to have been made by the author or manager (Charles Fleetwood) in response to these Examiner emendations. There are a small number of paragraphs marked with a small but enigmatic ‘x’ in the margin whose authorship is unclear. The interventions to this brief farce cover a wide range of categories; the objections are mostly political but also touch on gender, religion, profanity, and, perhaps, theatrical rivalries.

The play’s obvious political topicality was always likely to ensure a close perusal by the Examiner and most of the passages marked in the margin with the Examiner’s dashes relate to political or military references. There are a number of references to the episode of Jenkins’s ear marked for omission. First an explicit mention of the ear itself is censored (f.7r). Further references to the affair to the Spanish boarding an English vessel (f.9r) and the official Spanish denial of the affair (f.10r) are also marked, indicating that any allusion at all to this sensitive event was prohibited from theatrical representation.

There are also some broader geopolitical observations that provoked a response. A stage direction, which describes the collected sailors as mostly Spanish and English, also includes a redacted reference to ‘One in a french Habit’ (f.5r). The simplest explanation is that the manager struck this out as it was inaccurate: France was not party to the conflict. However, the phrase is both underlined and struck out, suggesting that the Examiner objected to the political implications of France being embroiled in the conflict and thus he underlined, an excision acceded to by the manager’s subsequent deletion. It had been expected—on both sides—that France would join the fray on the Spanish side but they remained neutral throughout. We might speculate then that representing the French as involved in the conflict on stage may have misled the audience and generated anxiety. Further references to Monsieur Chicane on (f.6r), (f.7v), (f.15r), and (f.17r) are also marked for removal and he is also crossed out from the ‘Dramatis Personae’.

The most extensive passage that is marked for removal is on (f.8r) where an exchange referencing English vanity and Meanwell’s observation that the English have long been a joke to the Spanish is crossed through with a large ‘X’. There is a suspicion that there was a brief attempt to redeem the passage by judicious deletion—see the crossing out ‘standing’—but that this was then abandoned in favour of simply removing this section of dialogue in its entirety.

Broader political commentary also elicited the censor’s disapproval. Sir John Freehold’s claim that ‘the Landed Gentleman of this Isle wou’d make but an Ill figure without them [the navy]’ (f.7v) is deemed to be out of order and is both marked by dashes in the margin and excised. Similarly, Meanwell’s insistence that ‘his Majesty has vindicated the freedom of his Subjects’ appears to have veered into overly Whiggish sentiment for the Examiner’s liking (f.8r). The manager appears to have attempted to rescue another similar sentiment occurs on (f.5v) where Capstern’s declaration ‘But I hope I have ne’er a Countryman scandalous enough to be stigmatized with the Honour’ has attracted two dashes of disapproval in the margin. ‘the Honour’ in question relates to the ‘Don’, explained to him as a Spanish title of nobility. The censor has read this conservatively as a snipe at the nobility more generally so the manager has adroitly added ‘to choose’ before ‘to be stigmatized’ in order to indicate that it is acquiescence to a Spanish appellation in particular that is being referenced here, rather than any disparagement of the nobility.

The play’s character Donna Americana also generated considerable censorial activity. If the quantity of dashes in the margin are any measure of the Examiner’s opprobrium, an exchange between Export and Sir John Freehold, which appear to offer America a considerable degree of political agency, deserve particular attention:

Export: But I think She is excusable for this Reason; as She is a Representative Character, She has full Power to speak & Act as she thinks proper.

Sir John: As She is a Foreigner indeed, her Politicks are not to be nicely Scann’d. But Mr Export had it been an English Character, some Politicians would have told you, that a Representative shou’d speak & Act only, as Instructed by their Constituents. (f.14r)

Both speeches earn four exasperated penned dashes each and the manager concedes the point by deleting them with a large penned ‘X’.

Concerns of political agency also extend to Kitty where references to her having a ‘political part’ and a subsequent patriotic exhortation on her part (f.3rv) draw a couple of single dashes in the margin. We might also read the objection to Americana’s claim that ‘tis their own fault if [the English] don’t Partake of my favors: for if our Sex has a Mind to grant a favour, hinder us if you can Signior’ (f.13r) in terms of gender politics.

A modified speech by Dapperwit warrants some attention: ‘What Pity, Sir, ‘tis that you have not a Genius for Stagewit – why, one of ye little Dramatick Wits at London little Mr. Bayes at London on such an Occasion would have introduc’d Squadrons & Lines of Battle & every Day added Reinforc’ment on Reinforc’ment ‘till he had shewn the whole British navy’ (f.14rv). One can speculate that the replacement text was intended to soften a snipe at Theophilus Cibber, who had played Bayes, in a performance of The Rehearsal on 31 October 1739 (CG) which had ‘an Additional Re-Inforcement of Mr Bayes’s new-rais’d Troops’ and which also featured a song based on the tune of ‘Britons, Strike Home’ (London Stage, 3: 798).

Religion and profanity also feature in the excisions with some deletions and replacements inserted in order to emphasise the Catholicism of the dissolute Spanish clergyman (‘priest’ for ‘Churchman’; ‘Father’ for ‘Doctor’) (f.15r). Profanity in the form of ‘Damn’d’ is excised on (f.15v).

Further reading

Yvonne Noble, ‘Phillips, Edward (b. 1708/9)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22149, accessed 8 Dec 2016]

Edward Phillips, Britons, Strike Home: or, The Sailor’s Rehearsal. A Farce (London: J. Watts, 1739)

[available on Google Books and ECCO]

Philip Woodfine, Britannia's Glories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain (Woodbridge, 1998).