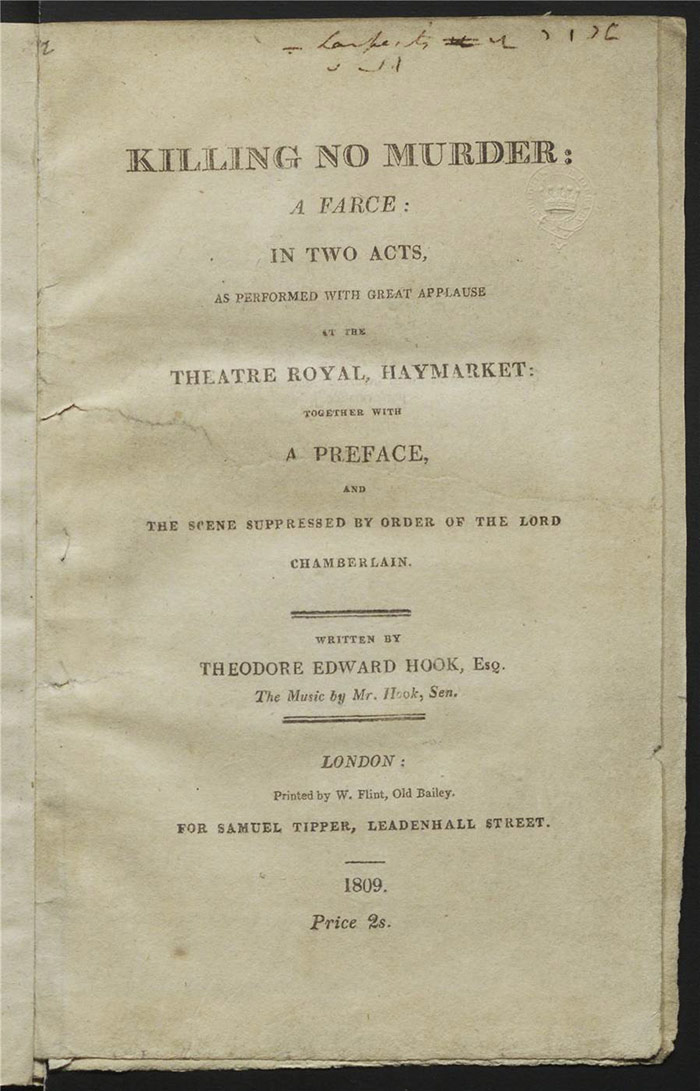

Killing No Murder (1809) LA 1582 / 1589

Author

Theodore Edward Hook (1788–1841)

Hook gained an early reputation for raillery and began writing librettos for his composer father’s operas such as Soldier’s Return, or, What can beauty do? (1805). He produced a number of farces and melodramas in subsequent years, one, Tekeli (1806), even earning Byron’s mocking in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers.

Hook gained considerable repute as a trickster. His Berners Street hoax of 1809 saw him arrange for the simultaneous delivery of items such as furniture, wagons of coal, jewellery and organs to a woman with whom he had had a disagreement. He also tricked various social luminaries such as the mayor of London and the duke of Gloucester to call on her at the same time. The street was blocked by gapers all day.

He ended up moving to Mauritius to act as treasurer in 1813. However, his tenure was a disaster. An 1817 audit revealed a shortfall of $62,000 for which he could offer no explanation; he was imprisoned in England 1823-25.

He continued to write plays and novellas through the 1810s and 1820s, some with success. A satire on Queen Caroline and Matthew Wood, Tentamen, or, An Essay towards the History of Whittington, Sometime Lord Mayor of London (1820), won him considerable acclaim as well as the editorship of John Bull. This journal was established in 1820 to undermine the popularity of Queen Caroline and the DNB ranks it alongside The Craftsman and the North Briton in terms of political influence. Never had Hook’s penchant for public comic scurrility been better on display.

The 1830s saw further novels as well as biographies, including the rewriting of Michael Kelly’s reminiscences. Coleridge described his genius as being comparable to that of Dante. His memory lived on after his death in 1841 with characters based on him featuring in Disraeli’s Coningsby (1844) and Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848).

Plot

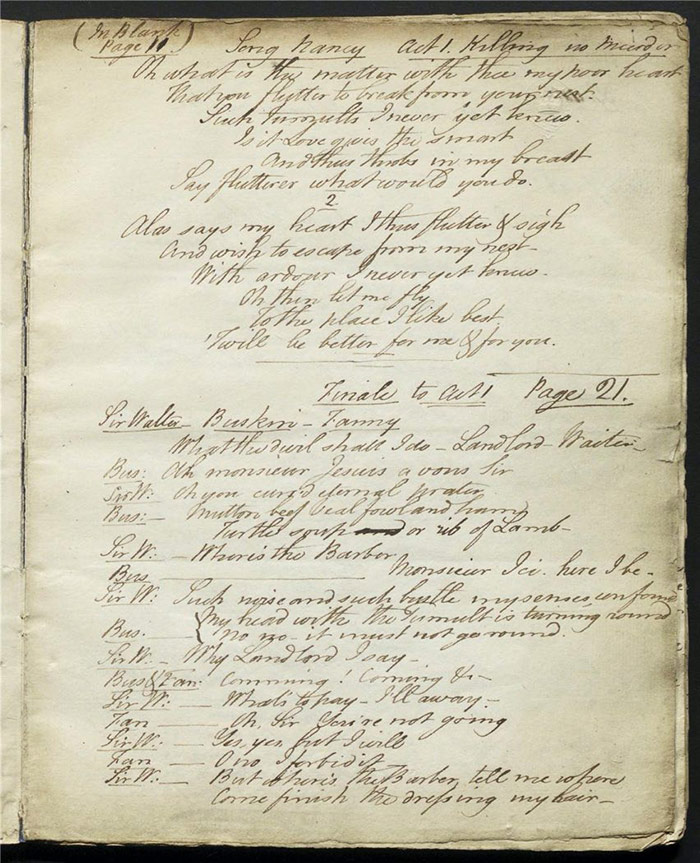

Charles Tap the landlord welcomes a stage of passengers to the London Inn. Among those alighting are Fanny (Tap’s sister) and her lover—and man of theatre—Buskin. But he is afraid to declare his feelings for her publicly as he anticipates the disapproval of her brother Tap. A further complication is her engagement to Apollo Belvi, a dancing master. Bradford, Buskin’s friend, enters to report on his unsuccessful attempt to see his lover Nancy Wellington who is under the watchful eye of her aunt. Buskin, with colourful references to the drama, encourages him to elope with her to Gretna Green in Scotland, the traditional destination of lovers who wish to marry without permission.

Nancy is being berated for wantonness by her aunt, Mrs Watchet (f.4v). Sir Walter, Nancy’s uncle and the magistrate, arrives to speak to Mrs Watchet. He announces that rather than going to the trouble of finding her a husband, he will marry her himself. Although she had previously been destined for his nephew, he has abandoned the law and gone to dissipation. Mrs Watchet tries to dissuade him, saying that Nancy is too young for him, not least, it is insinuated, as she has designs on Sir Walter herself. Nancy overhears all of this and decides she will elope with Bradford.

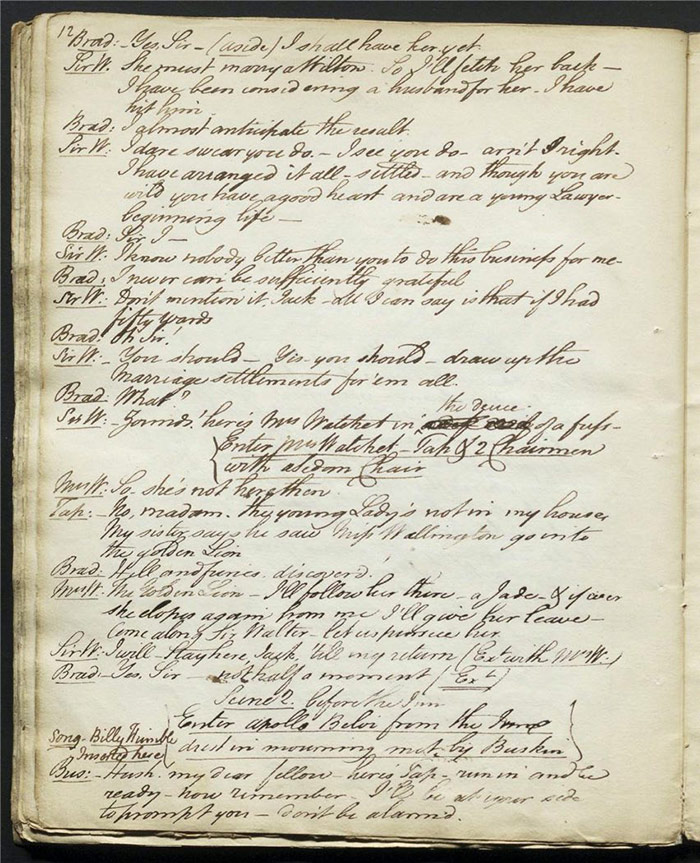

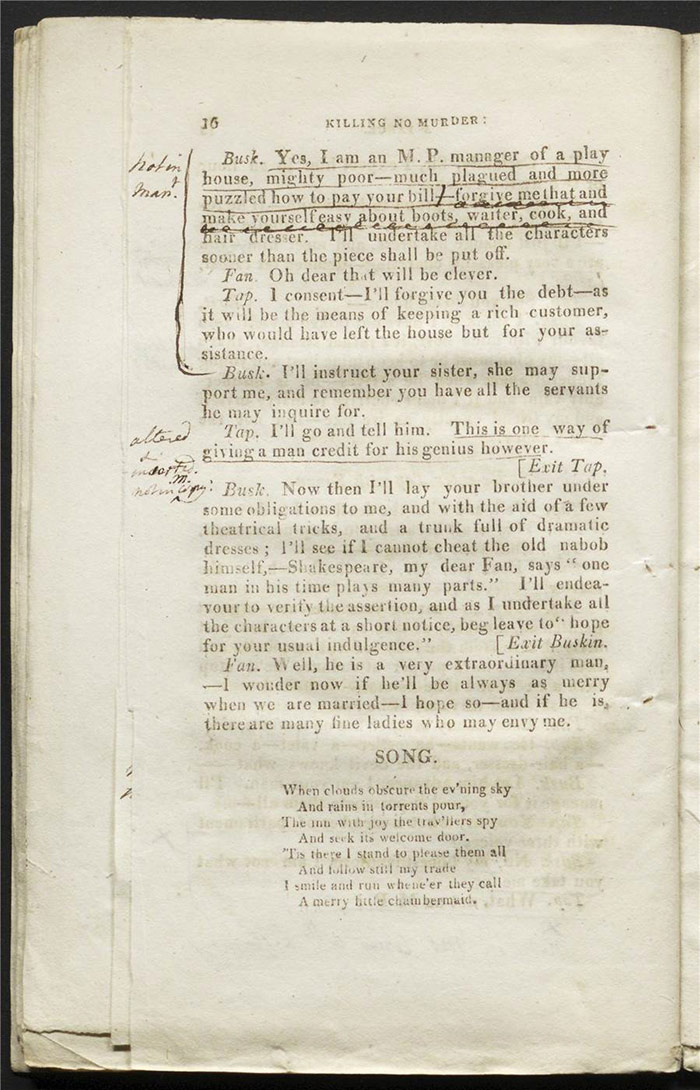

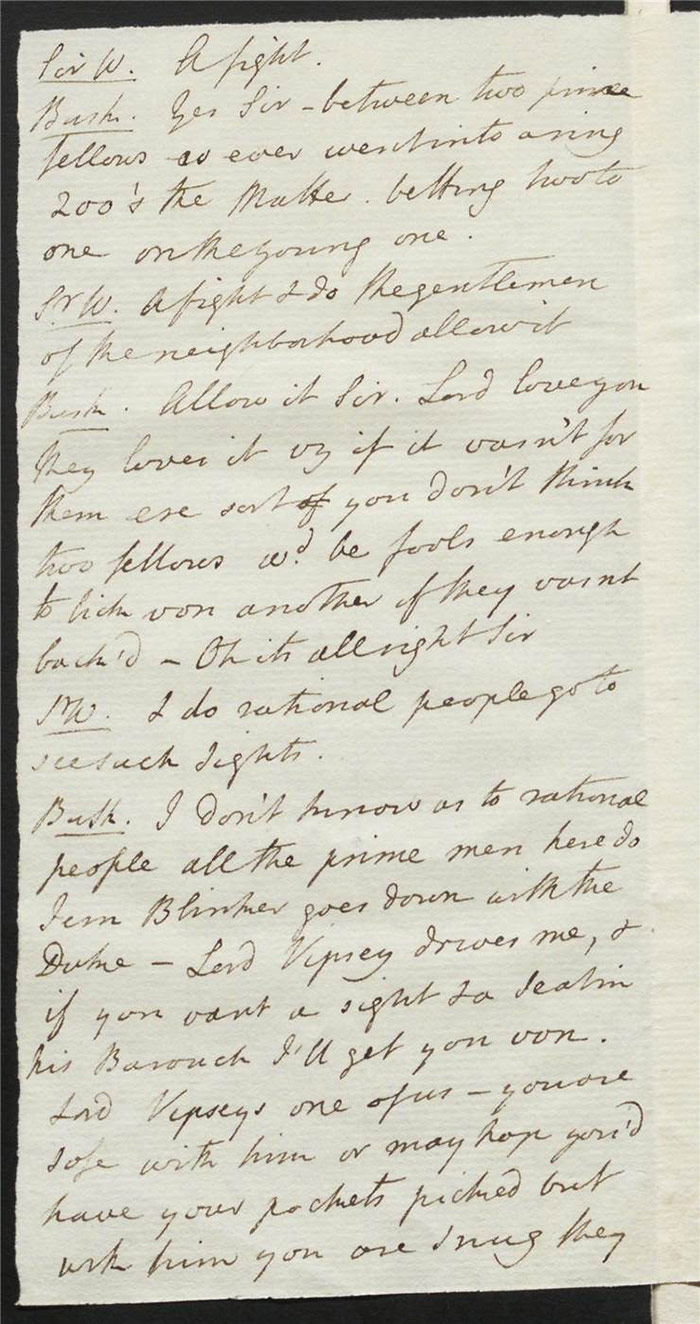

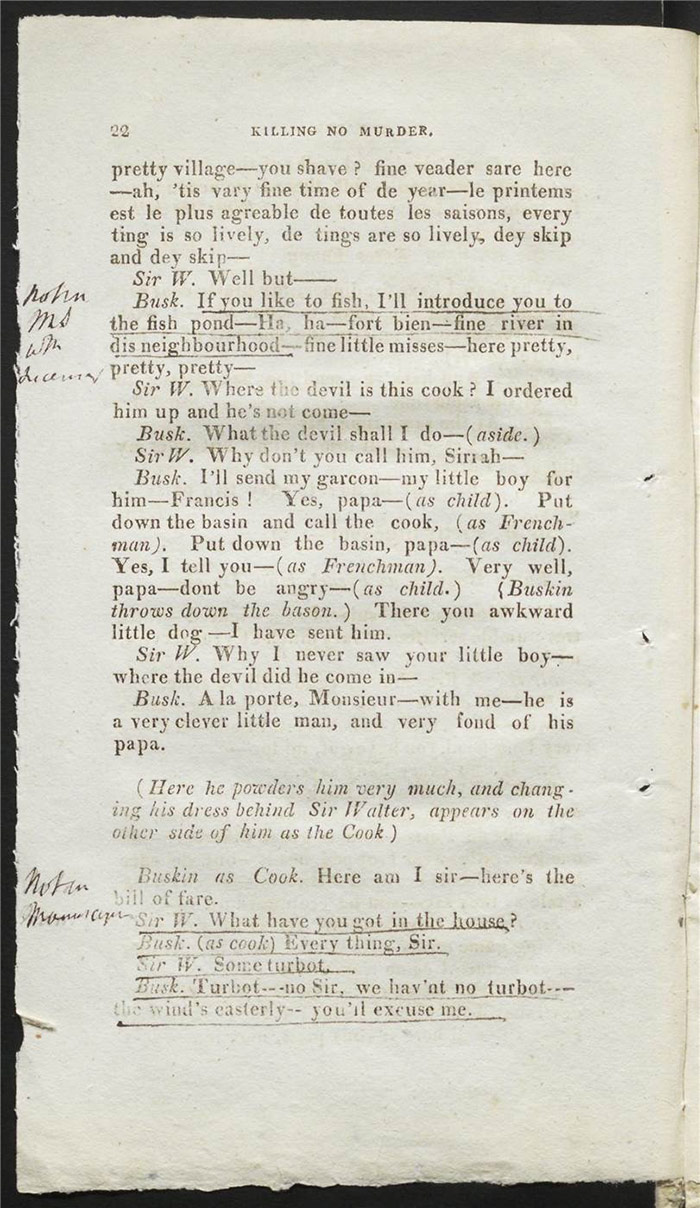

Back at the inn, Tap tries to get Buskin to pay his bill (under the mistaken impression that he is a gentleman and an MP) (f.5v). Buskin deliberately misreads the conversation with humorous effect but then reveals his true identity when Sir Walter arrives at the inn: he will not stay without the appropriate staff and Buskin offers to play the multiple roles that will allow Tap to give the impression of a respectable establishment and Tap agrees to forgive his debt. Sir Walter enters and Buskin comes to in various guises as a boot shiner, a racing groom (or waiter as he becomes in LA 1589), and a French hair dresser. The act ends with Sir Walter threatening to leave, befuddled by Buskin appearing in successive parts and in song.

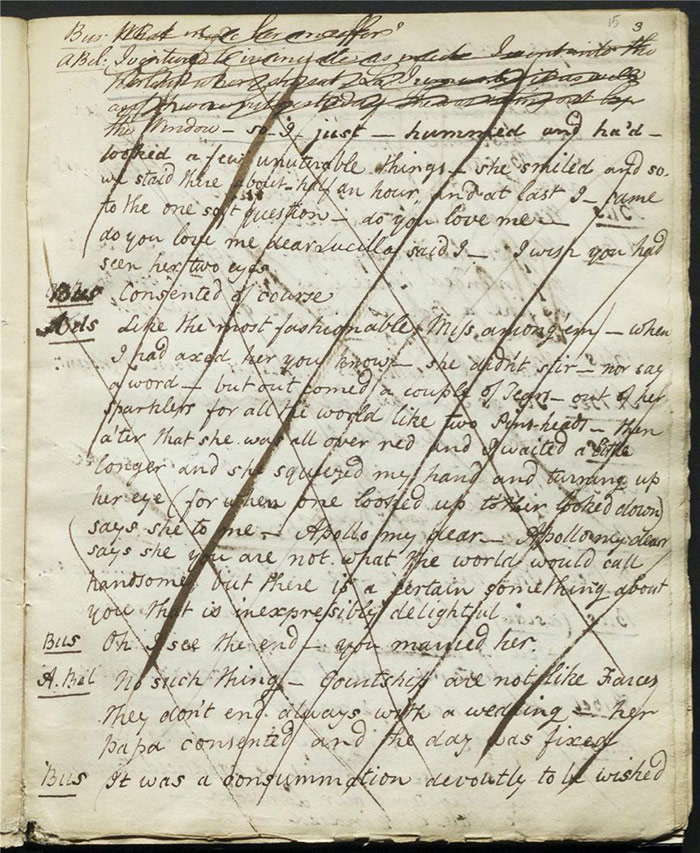

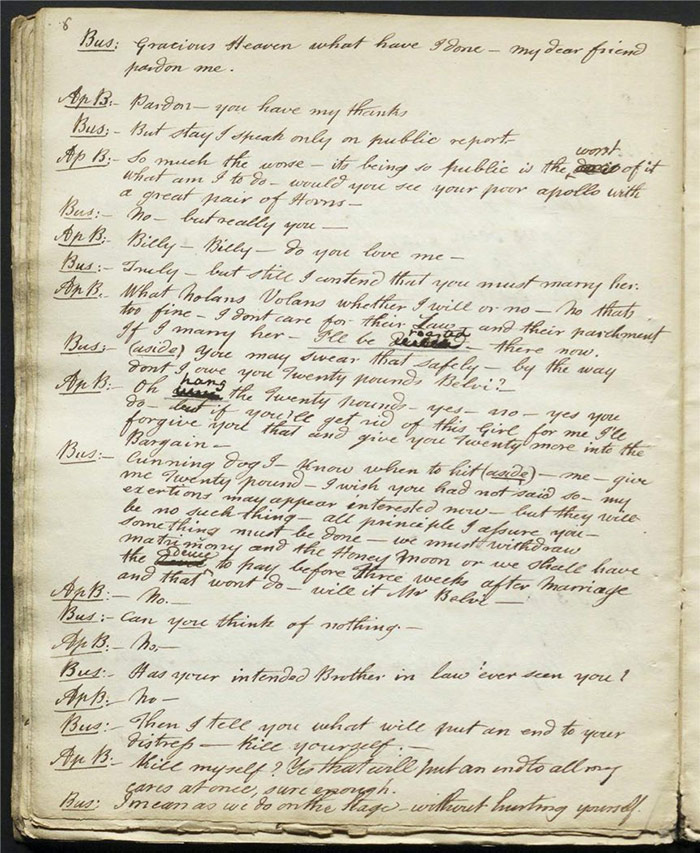

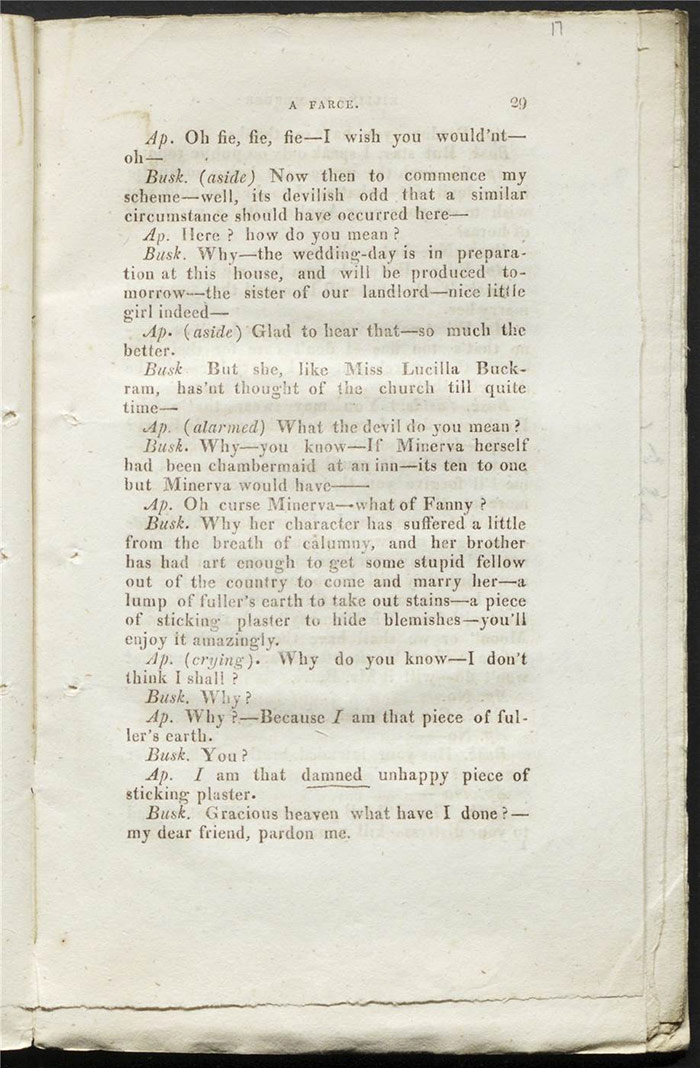

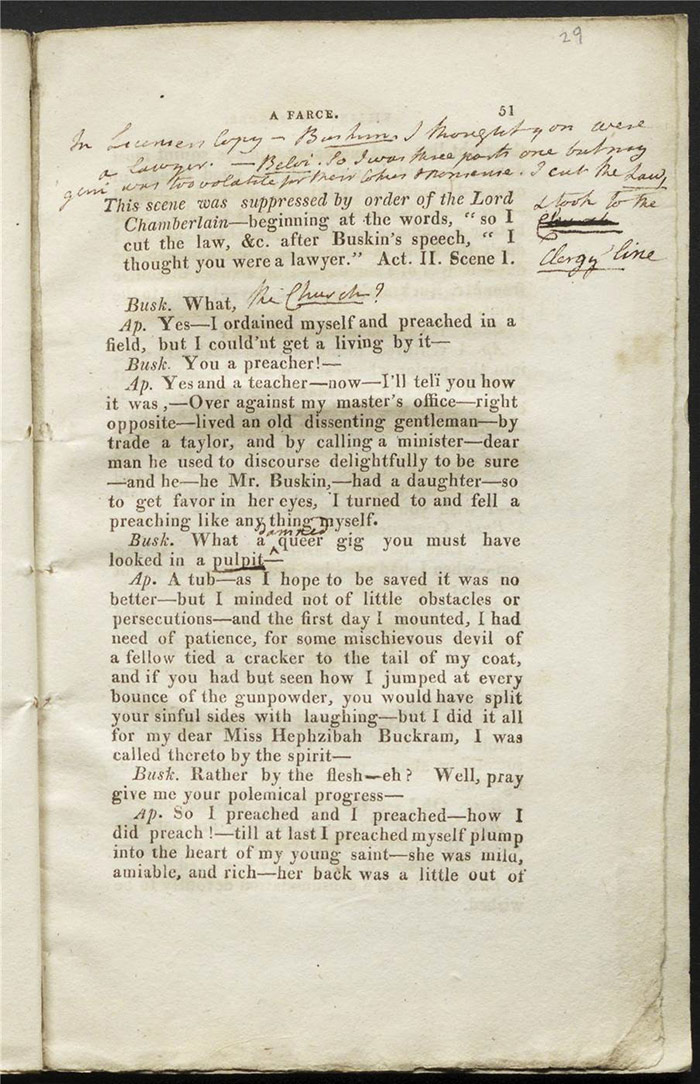

Apollo Belvi arrives at the inn in the second act and is reunited with Buskin (f.12r). Belvi reveals he left the legal profession and took up with the church. He tells Buskin how he became a preacher in order to impress the father of a girl he liked (the father is a tailor and a dissenting minister). He wooed her with his preaching and a date was set for their wedding when, the night before, the ministers’ daughter gave birth to a child of unknown parentage – although Apollo does not convincingly refute the charge that he may have been the father. [This anecdote is cut in the manuscript and the inserted (ff. 13-14) reimagine the tailor/minister as a tailor/aspiring actor]. Buskin then puts his plan into action by insinuating that Fanny may be pregnant and that her brother Charles has tricked some country yokel to marry her (Buskin is aware that this yokel is Apollo). Apollo, upset, promises to forgive Buskin a debt if he will get him off the hook. Buskin suggests that Apollo take on the character of his own cousin and announce Apollo’s death (it’s all an acted death, thus ‘killing no murder’).

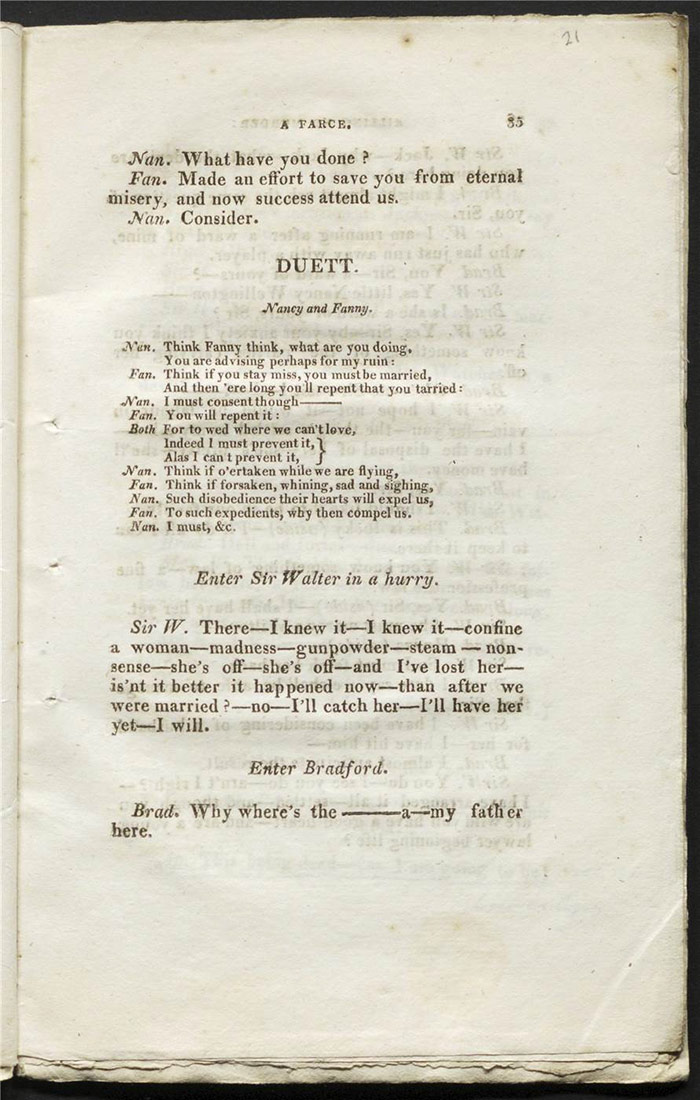

Nancy and Bradford arrived, eloping from her aunt. Nancy is nervous and is threatening to baulk when Fanny arrives. She sends Nancy to go to another inn, assuring Bradford he will find her there in due course. Sir Walter and Bradford meets. Sir Walter tells his son that Nancy, his ward, must be married to someone in the family – meaning himself. Mrs Watchet arrives, looking for Nancy. Tap reveals that she’s gone to the other inn and Mrs Watchet and Sir Walter leave to get her.

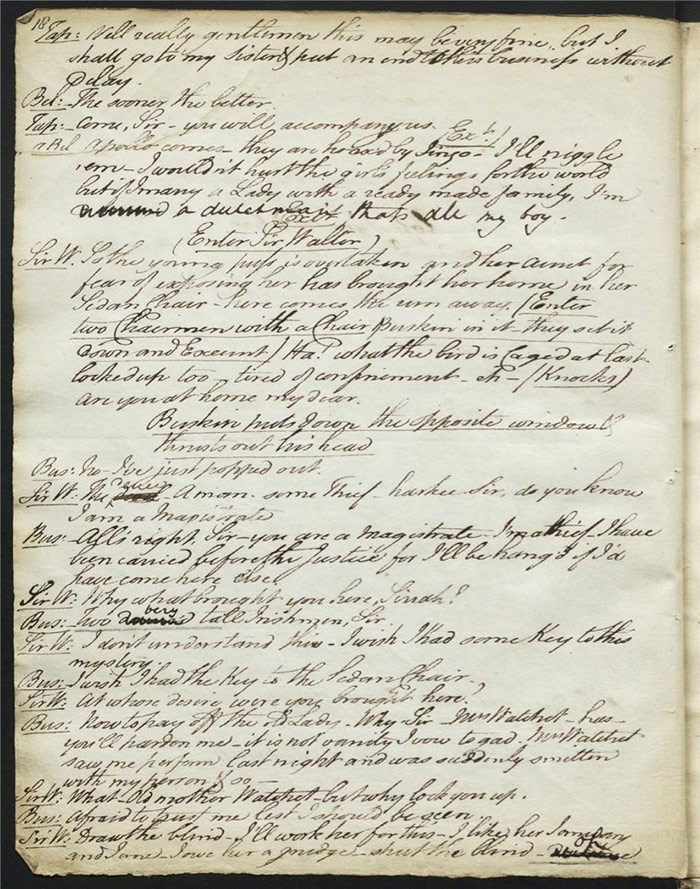

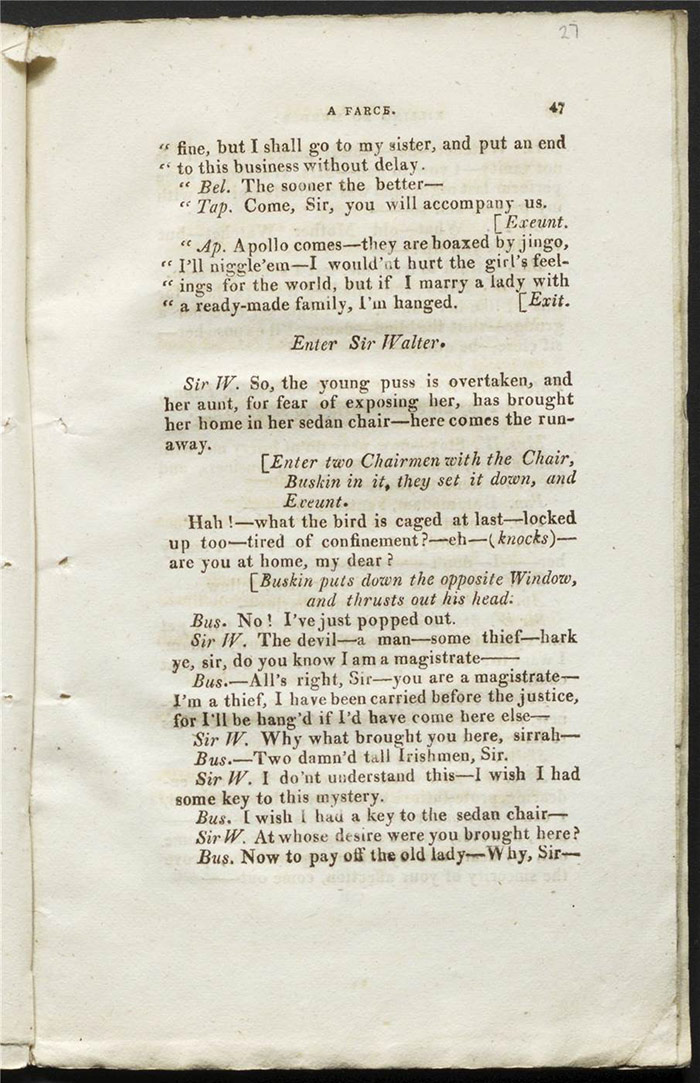

Apollo, in mourning suit, and—very clumsily—passes himself off his own cousin to Tap (f.19v). Tap is frustrated but is placated when Buskin tells him he knows someone who will marry her for a smaller dowry. In the meantime, Mrs Watchet has seized Nancy and is bringing her to the inn. Buskin promises Fanny that he will rescue her. When Mrs Watchet brings Nancy to the inn in a sedan-chair, Buskin manages to let her out while he goes into the chair to replace her.

Apollo Belvi’s uncle meets Tap at the manor house and is surprised to learn that his nephew is apparently dead (f.21v). Sir Walter, the magistrate, discovers Buskin in the sedan-chair when it arrives and determines to expose Mrs Watchet (Buskin has told him that she hid him in there as she took a fancy to him). All the characters emerge on the stage then. Bradford is revealed to Mrs Watchet as Sir Walters’ son and thus her objections are abandoned for a happy conclusion.

Performance, publication, and reception

The play was submitted by James Winston to Larpent on 20 June 1809. However, Larpent had some issues with the manuscript and sent it back for revision (there are no mentions of the play in Anna Larpent’s diary for the month of June). The play was resubmitted on 22 June. The changes were made to Larpent’s satisfaction and the play was granted a licence.

Although the Macmillan catalogue suggests that the first performance was on 21 August, the play was actually first staged on 1 July and indeed was virtually ubiquitous on the Haymarket stage for the rest of the month.

The newspapers are unusually quiet on this comedy. The Morning Chronicle (3 July) appears to offer the only review in the British Library Newspaper database:

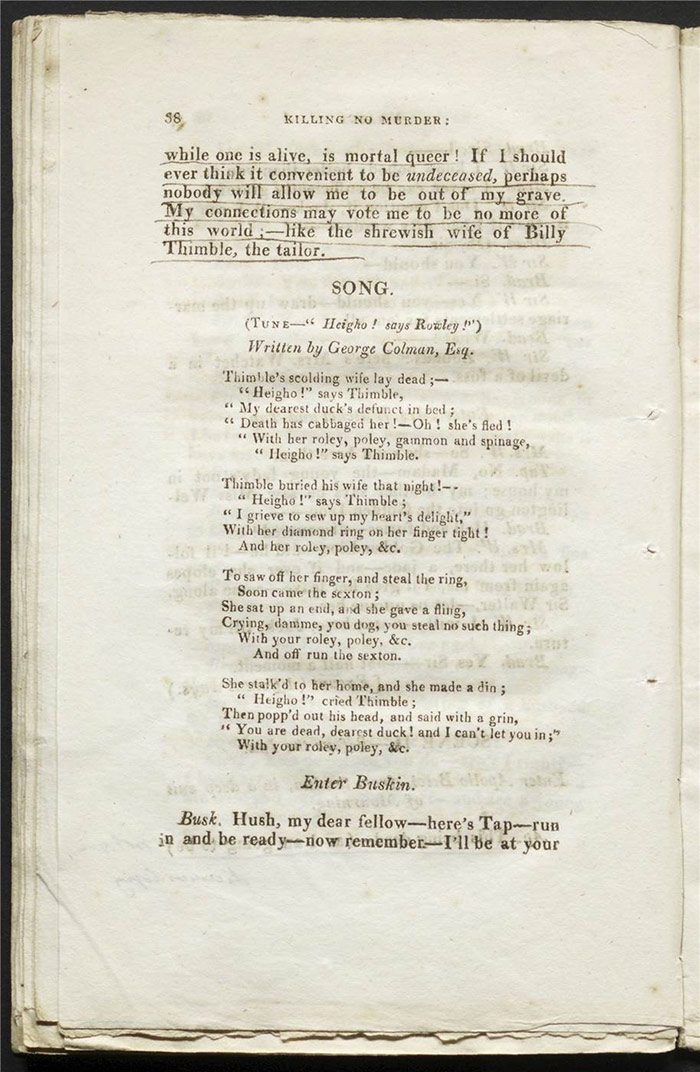

Mr. Hook’s operatical Farce of Killing no Murder, was produced on Saturday, the parts objected to by the LORD CHAMBERLAIN having been expunged. The plot turns upon the efforts of Billy Buskin (MATHEWS), a strolling player, to avoid paying his bill at an inn, and to secure his marriage with the landlord’s sister. The author has been very happy in his endeavours to afford an opportunity for the display of the peculiar powers of MATHEWS and LISTON; and supported as it is by these able performers, the piece will certainly prove attractive. The music is pretty, and two of the songs were loudly encored. In one of these, the singing and dancing of the Opera-house were ridiculed with great success.

The only other newspaper account of the play (although we must acknowledge the weaknesses of the search facility of digital archives – there may well be more reviews extant which could be discovered with more patient archive work) was from the Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle (3 July) which mistakenly reported that ‘The Lord Chamberlain has refused to grant a license for the performance of Mr. Theodore Hook’s new farce of “Killing No Murder,” and in consequence of such refusal the piece is withdrawn’.

Despite the paucity of commentary in the newspapers, there is evidence of the play’s popularity and considerable penetration of the public consciousness was the use of the play title in contemporary political caricatures. Isaac Cruikshank’s caricature Killing No Murder, or a new ministerial way of settling the affairs of the nation critiqued the duel between the two ministers Castlereagh and Canning (due to a dispute over foreign policy) and was published in September 1809. George Cruikshank produced a satire on the Old Price Riots at Drury Lane titled Killing no murder. As performing at the Grand National Theatre in November 1809. The title of the play is, of course, an allusion to the Civil War pamphlet published in 1657 calling for the assassination of Oliver Cromwell.

Commentary

In previous examples where we have looked at two manuscripts we have generally taken each in turn. Here, however, we have a set of unique circumstances which suggest an alternative method would work better.

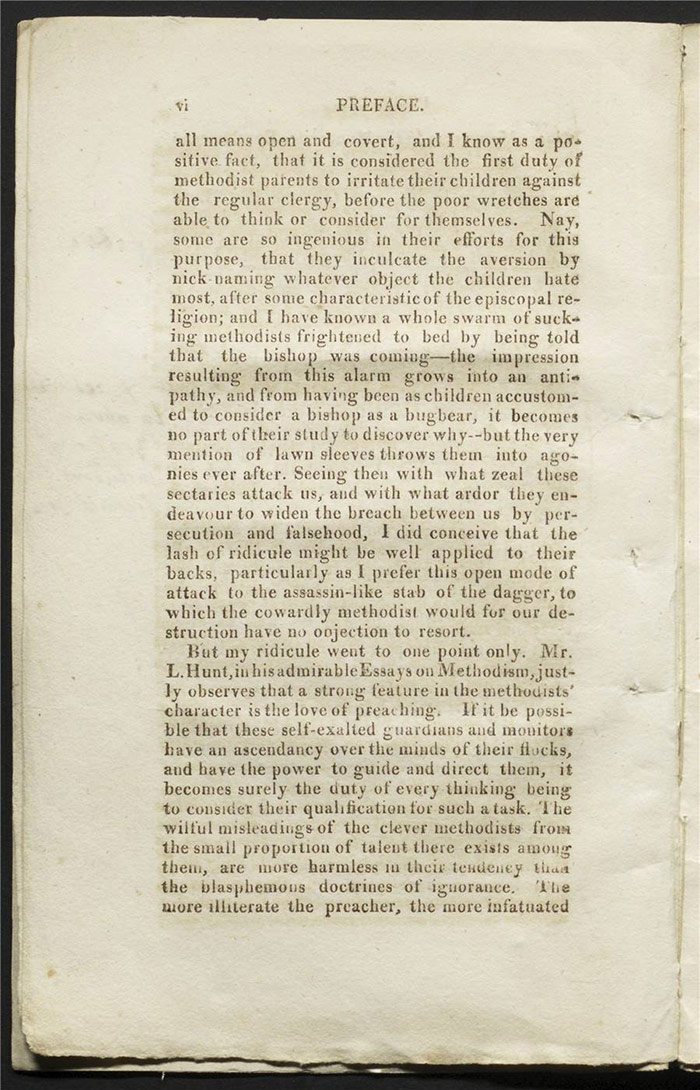

When Hook published his play in early July, the preface castigated Larpent’s interference with his original play in terms that Larpent considered to be libellous. The preface also gives some more detail around the submission and assessment of the manuscript. The preface’s ad hominem attack riled Larpent as suggested by his copy of the published play which contains some marvelous annotation, unique in the Larpent collection, where the writer challenges the assertions made by Hook. Although the writing bears some resemblance to Larpent’s, it also looks very much like Anna Larpent’s hand. Moreover, her diary tells us that she ‘spent 2 hours looking over Hook’s publi[shed] no murder & the licensed copy’ on 15 July 1809 [f.238v] so it seems likely that she is at work here. There is no record of a discussion with her husband but it is safe to assume that she was engaged in preparatory work on her husband’s complaint to the Lord Chamberlain, Dartmouth. On 18 July she then ‘copied Mr L’s letter to Lord Dartmouth abt Hook’s Libel’ [f.239r]. Unfortunately, we are none the wiser on how Dartmouth responded to this missive—probably the most forceful response to public criticism the Larpents made over the course of John’s tenure as Examiner.

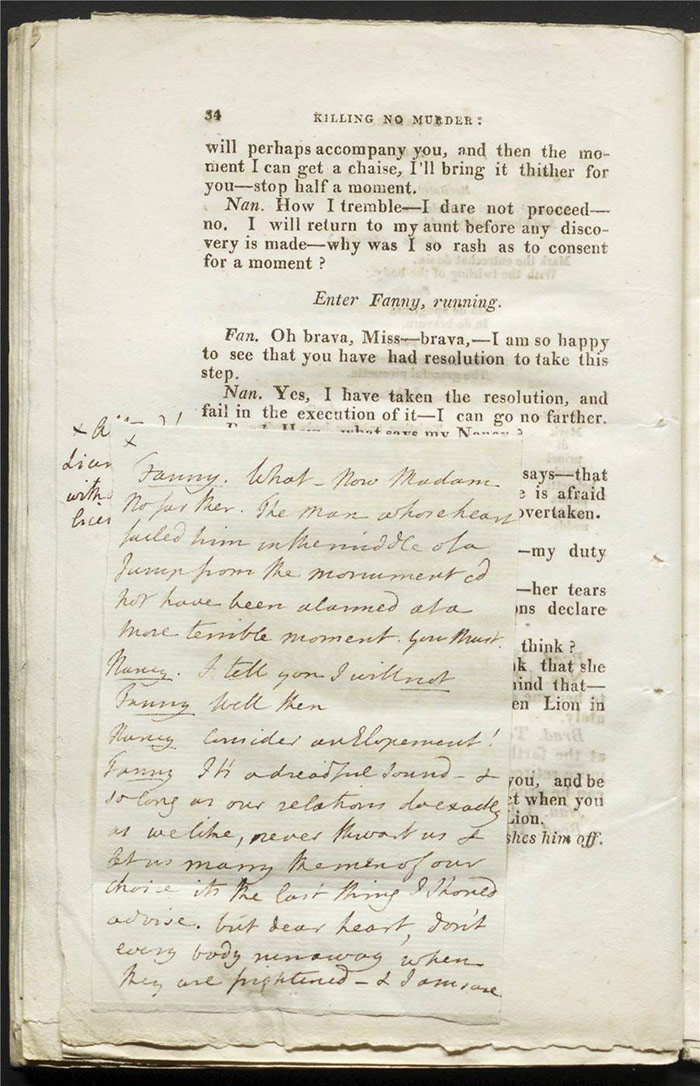

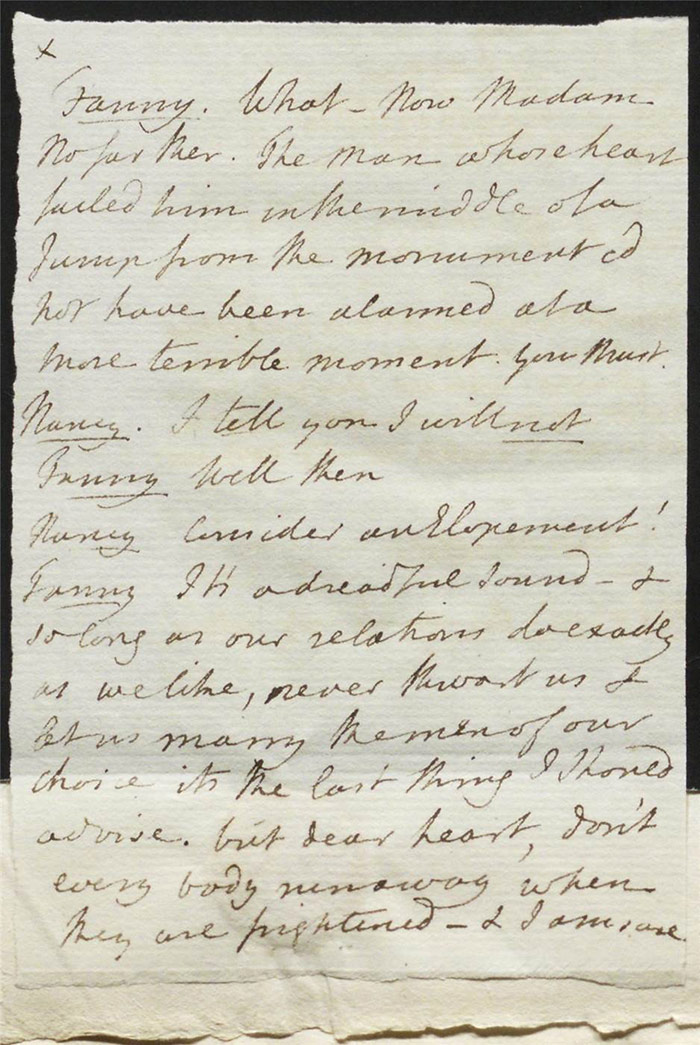

This brief introductory note cannot cover the rich interplay of the manuscript, the annotated published version, its preface and the Larpent response thus the reader is encouraged to work through the materials in greater detail. In the remainder of the space here, some highlights will be offered from the preface and Anna Larpent’s response to same, taking into account the evidence of the two versions of the comedy. We will note Hook’s insertion of dialogue in the second version intended explicitly to critique the censorship process.

In general terms, the first manuscript (LA 1582) shows a number of excisions and emendations. With thanks to Hook’s acerbic response to Larpent, we can be reasonably confident that John is responsible for the majority, if not all, of the excisions in this manuscript while the annotation is mostly attributable to Anna. The cuts he demanded seem to be related largely to critiques of Methodism and profanity. The second text (LA 1589) shows Anna Larpent’s annotation and commentary on the claims made by Hook in his preface as well as some comparative work between the two versions.

The preface tells us that Hook called on Larpent when he heard his play was to be refused a licence on either political or moral grounds. When he arrived at Larpent’s home, he claimed he was left waiting for dramatic effect:

After a seasonable delay to beget an awful attention on my part, he appeared, and told me with a chilling look that the second act of my farce was the most “indecent and shameful attack on a very religious and harmless set of people” (he meant the Methodists:) “and that my piece altogether was an infamous persecution of the sectaries”—out came the murder—the character of a Methodist preacher written for Liston’s incomparable talents, with the hope of turning into ridicule the ignorance, the impudence of the self-elected pastors who infest every part of the kingdom met with the reprehension of the licenser. (LA 1589, f.iv)

In the left margin of this paragraph Larpent has marked it ‘X’ and ‘false’, disputing Hook’s account of the conversation. Two further instances of ‘false’ are on the same page; these are related to Hook’s claim that Larpent said to him ‘GOVERNMENT DID NOT WISH THE METHODISTS TO BE RIDICULED’ and his further claim that the Larpent had ‘even built a little tabernacle of his own’. Hook’s criticism of Larpent was personal and ironically called into question his fitness for the lucrative office he held:

I took my leave, fully convinced how proper a person Mr. Larpent was to receive, in addition to his other salaries four hundred pounds per annum, besides perquisites for reading plays, the bare and simple performance of which by his creed is the acme of sin and unrighteousness—his even looking at them is contamination —but four hundred a year—a sop for Cerberus—what will it not make a man do? [Larpent retorts in the margin: ‘X reduce to about 300£ a yr including the Licence Fees] (LA 1589, f.iir)

The preface continues in a detailed explanation of Hook’s rationale for poking fun at Methodists in the character of Apollo Belvi. Essentially, Hook is motivated not only by their, as he sees it, self-importance and grandiosity but their attacks on and undermining of the established church.

Before turning to the play proper, it is worth noting that the advertisement to the play offers ironic thanks to both Larpent and Dartmouth for their unwitting marketing efforts on Hook’s behalf:

The great applause Killing No Murder has received, calls me to make my acknowledgements where they are due. To Mr Larpent, for refusing his licence, and creating interest for the farce, I am first obliged—to Lord Dartmouth, for his concurrence in the refusal, equally indebted—the Lord Chamberlain and his deputy were as good as a dozen newspaper paragraphs to me. (LA 1589, f.iiiv)

As Lord Chesterfield observed in his well-known—if unsuccessful—speech opposing the introduction of the Licensing Act in 1737, ‘people are fond of what is forbidden’. The evidence of the play’s popularity in the month of July and its presence as a trope in contemporary caricatures confirm Hook’s gloating that the censorship measures taken only served to widen public awareness and interest, as Chesterfield anticipated.

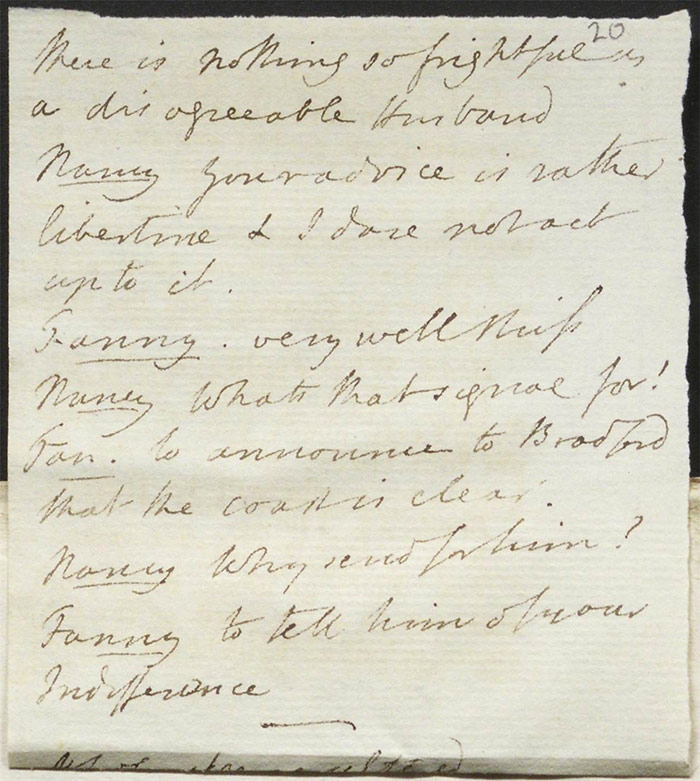

Turning now to the Larpent manuscript and the annotated print version, we can first compare one early reference to Methodism. In this early exchange between Fanny and Buskin, the lovers plot to foil the planned wedding between her and Apollo Belvi. Buskin tells Fanny:

Leave that to me – he is a consummate coxcomb – a Strange mixture of Boor and Beau – is in high practice as a Cutter of Capers at Swansea

& has been till lately a Methodist preacher.I’ll settle all that. (LA 1582, f.2r)

An insertion just underneath the excised sentence (crossed out in pen) reads ‘oh no’. If we look at the comparable passage in the print version we have the following rewrite:

Leave that to me—he is a consummate coxcomb – a strange mixture of boor and beau – is in high practice as a cutter of capers at Swansea, and has been till lately a—what I must not mention*—XI’ll settle all that.

*In the piece originally “a Methodist Preacher” X but altered by order of the Licenser. (LA 1589, f.2r).

Anna Larpent has put in the Xs as well as underlining the reference to Methodism. At the bottom of the page she insists ‘Not erased by Licenser, but struck out in consequence of the Change of Character’. Even in this small opening example, one can see the complexity in trying to unpick the truth of the matter. We can take neither party at their word: Hook is trying to win over the public while the Larpents are attempting to convince Dartmouth that a case for libel exists. We might observe that the unusually emotive ‘oh no’ does not, on the face of it, support the contention that the change was made for dramatic rather than censorship reasons. Nonetheless, we cannot be certain. What is fascinating in this example is that Matthews—who receives particularly warm praise as a man as well as an actor in the advertisement—would have had a fabulous opportunity to deliver that line ‘what I must not mention’ to a knowing audience. It is rare to see such a condemnation of John Larpent or indeed any other Examiner explicitly imagined for stage performance.

An example shortly after provides some further evidence on the question of Methodism. Hook makes another complaint about an alleged excision in a speech from Buskin:

Why she’s as proud as a lioness, watchful as a lynx, and for hypocrisy an over-match for—what must not be mentioned.* X

*“Methodist,” again—another erasure. (LA 1589, f.3r)

Larpent has annotated the bottom of this page; ‘X Not erased in the Manuscript with the Licenser ‘till the Character was changed’. And if turn to the original manuscript, we can see that he is absolutely right. The relevant folio (LA 1582, f.3r) reveals no interference on the part of Larpent here. That Larpent may simply have missed the reference seems improbable, given his sensitivity to this issue. We must also consider what, precisely, Larpent is claiming here. In effect, all he is stating that he didn’t make any actual marks on the manuscript – but it is clear from the earlier example and from the deletion of later folio pages in their entirety that there was a general demand that the references to Methodism be expunged, whatever about the technicalities of this particular reference.

Moreover, we might note with interest that Larpent has pasted in a note here where she has carefully copied some lines of dialogue which were cut from the printed version on literary rather than censorship grounds. We may surmise that this done to offer some supporting arguments to Dartmouth that Hook was making publicly libelous claims about a text that was not the one that was examined by Larpent. There are a number of other comparable notes by her noting such—innocuous—discrepancies on inter alia LA 1589, f.3v, f.5v, f.7rv, and f.18r (this final example is notable as Hook as introduced the title of the play into dialogue, taking advantage of an opportunity he had missed in the first version).

From these few examples (and there are more), we can see the care and attention the Larpents put into responding to what they saw as an unwarranted attack on John Larpent’s office. Hook evidently made the very most of the controversy around the play, sensing both a chance to get a measure of revenge in his censor and commercial opportunity. However, in the end the reader of the initial manuscript can see unequivocally on (LA 1582 , f.12v) and (LA 1582, f.15rv), folio pages excised with a furious pen and pencil, that mockery of religion was something that Larpent would not tolerate. There are also multiple excisions of swearwords, primarily ‘damme’ throughout (interestingly, Hook was happy to retain the cleaned up language for the print version). Killing No Murder is an extraordinary episode in the history of theatre censorship and it can only be hoped that further research might shed more light on the public interest in it or indeed Dartmouth’s input.

Further reading

R.H. Dalton, Barnham, The Life and Remains of Theodore Edward Hook (London: R. Bentley, 1846), vol. 1.

[available on HathiTrust.org]

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 157-159.

Graham Harper, ‘Hook, Theodore Edward (1788-1841), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Pres, 2004; online edn Oct 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13686, accessed 12 November 2018]

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, HM 31201, vol. 7, ff.238-239