Monody on the Death of Sir John Moore (1809) LA 1568

Author

Matthew Lewis (1775-1818)

Lewis was educated at Oxford and, although he would become famous for his novel The Monk (1796), he had a considerable interest in the theatre from an early age. He spent a year in Paris after graduation where he wrote a farce The Epistolary Intrigue in 1791 and completed a comedy The East Indian in 1792 (staged Drury Lane, 1799). He initially pursued a diplomatic career and became an MP in 1796, the same year in which The Monk was published.

He had his greatest theatrical success in 1797 when The Castle Spectre was staged at Drury Lane. Despite being attacked for radicalism, particularly around its criticism of feudalism and slavery, the play was an enormous success. It had over 40 performances in his first season and was established in the repertory for many seasons after that.

He had further plays staged in both major London playhouses over the following years. At Drury Lane, he had two comedies performed in 1799, The Twins and The East Indian. At Covent Garden he had a full five-act tragedy Alfonso, King of Castile staged in 1802 to much critical success. Other plays followed but he had his most extravagant spectacle with Timour the Tartar (Covent Garden, 1811) which featured live horses on stage. Despite a roar of critical repugnance, it was a commercial smash hit with 44 performances that season.

Plot

Given the brevity of the monody, a full transcription is offered here:

[f.2r]

Monody on the Death of Sir John Moore

(To be introduced by the Dead march in Saul)

From sad Iberia’s coast while Gallic Fires

Pursued his bark, and shook Corunna’s spires.

A British Chief, as plunged in grief he eyed

The Shores, where Moore had fought, where Moore had died,

Dash’d from his Cheek the manly tear, and paid

This parting tribute to the Hero’s shade.

- “When first, oh! Moore, that truncheon of command

You swayed so ably, graced your martial hand,

Who that had seen you; had forborne to say

- “Favoured of God and Mortals, speed thy way!

If Man there breathes, to whom by lavish Heav’n

Unbalanced bliss and cloudless skies were given,

Whom Nature’s eyes and Fortune’s seem’d to see

Alike with partial love, sure thou art He.” –

For who with Moore in Nature’s gifts could vye,

Or when did Fortune richer streams supply?

His person formed the coldest maid to move

His hand for friendship, and his heart for Love,

Frank in his language, polished in his mind,

Was none more firm or gentle, true or kind

E’en Fortune’s self his merit seemed to feel,

For him unveil’d her Eyes, and fixt her wheel:

No chilling clouds obscured his dawn, and bade

His youthful talents languish in the Shade;

[f.2v]

To clear his passport to the shrine of Fame,

All owned at once the justice of his claim

Nor dared e’en Envy’s self deny through spite,

That Moore had merit, or the Sun gave light.

He mourned no slanderous tale, no jealous hate,

Nor paid that common tax for being great;

With steps so firm he trod his even road,

So pure from soil his brilliant current flowed,

That Slander quite despaired his life to stain,

Nor wasted efforts on a task so vain.

His earliest Youth was gilt by Glory’s rays,

Year followed year, and praise was heaped on praise.

How bright the scenes, which round his Manhood rise;

Still brighter prospects beckoning Time supplies!

All thought deserves, all Men from Heaven implore

All these are his……Alas are his no more.

Health, Virtues, Talents, glory, rank and power…

The wealth of years is spent in one short hour.

Fate guides the ball to strike the Hero low,

And England’s bleeding bosom shares the blow:

“And couldn’t thou, Moore, ere fled thy thy soul away*

Doubt, Britain to thy shade would honors pay?

And could He value trophies rais’d by art;

Whose fame must live stamped on each Briton’s heart?

Oh! in your martial Bands with gashes seamed,

Saved by thy prudence, with thy blood redeemed,

Behold a monument of prouder praise

Than Head can fancy, or than Hand can raise.

Each anxious mother, and each tender wife,

Who trembled for a Son’s or Husband’s life,

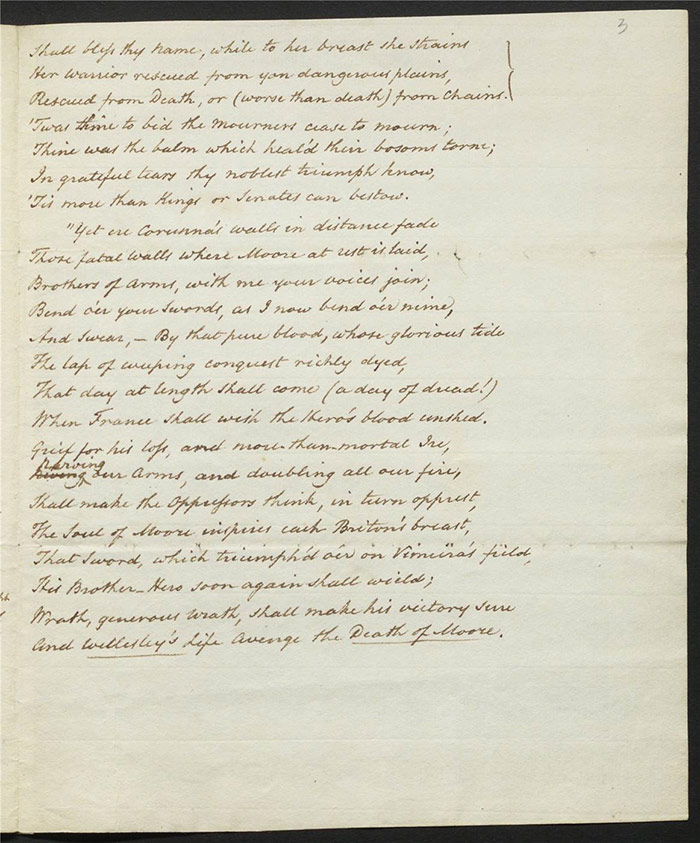

[f.3r]

Shall bless thy name, while to her breast she strains

Her warrior rescued from yon dangerous plains,

Rescued from Death, or (worse than death) from chains.

’Twas thine to bid the mourners cease to mourn;

Thine was the balm which heal’d their bosoms torne;

In grateful tears thy noblest triumph know,

’Tis more than Kings or Senates can bestow.

“Yet are Corunna’s walls in distance fade

Those fatal walls where Moore at rest is laid,

Brothers of arms, with me your voices join;

Bend o’er your swords, as I now bend o’er mine,

And swear, – By that pure blood, whose glorious tide

The lap of weeping conquest richly dyed,

That day at length shall come (a day of dread!)

When France shall wish the Hero’s blood unshed.

Grief for his life, and more than mortal Ire,

Nerving our arms, and doubling all our fire,

Shall make the Oppressors think, in turn opprest,

The Soul of Moore inspires each Briton’s breast,

That Sword, which triumph’d o’er on Vimeira’s field,

His Brother-Hero soon again shall wield;

Wrath, generous wrath, shall make his victory sure

And Wellesley’s Life avenge the Death of Moore.

*alluding to his being said to have expressed a wish in his last moments that his country might bestow some mark of approbation on his memory.

Performance, publication, and reception

The Drury Lane prompter William Powell submitted the monody to Larpent on 11 February 1809 with the standard cover note. It was advertised on 13 February in the Morning Chronicle for delivery the following night and was spoken by Mrs Powell after a performance of The School for Scandal and Blue Beard at Drury Lane Theatre. It was advertised again on 15 February for performance on 16 February and on 17 February for the 18 February. The manuscript instructs that it was to be introduced by the dead march from Handel’s Saul (1739).

The monody—an elegaic poem or funeral oration—is a very rare genre for the theatre. There is only one other example in the Larpent Collection, written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan and dedicated to memory of David Garrick in 1779 (LA 471). Lewis himself had written one earlier in tribute to Charles James Fox (Wilson, 381-87) in 1806 (as did the reformer John Thelwall).

There are no newspaper reports of its reception. But The Poetical Register, and Repository of Fugitive Poetry, for 1808–1809 (London: F.C. and J. Rivington, 1812), although puzzled at the withdrawal of the piece, thought it was of reasonable merit:

Were Solomon himself now alive, it would puzzle him to find out any cause which could have induced the Lord Chamberlain to prohibit the recitation of these lines. We have not been able to discover a single word capable of giving offence. The Monody seems to be a hasty production, and is not equal to many of Mr. Lewis’s former compositions. It is, nevertheless, evidently the work of a man of genius. (600-601)

Lewis was himself rather pleased with it and wrote to his mother to tell her that it was dedicated to the Princess of Wales who ‘accepted it graciously’. He also revealed that MP George Tierney ‘abused ministers’ about the monody (Wilson, 375). Lewis appears to have been rather put out by the prohibition of the monody and arranged to have fifty copies printed for distribution.

There is no mention of the monody in Anna Larpent’s diary; she does, however, begin reading ‘Letters during Sr J Moore’s Campaign’ on 7 July 1809, possibly a reference to A Narrative of the Campaign of the British Army in Spain (1809). On 11 July she offered this extended ‘observation’ on Letters from Portugal and Spain, written during the march of the British troops under Sir John Moore (1809):

These letters are written in such an affected manner the stile is so very inflated one can hardly read them with patience ‘tis a poetic prose in extreme bad taste & a tortured attempt at playfulness. I began the book once & left it with a sullen indignation yet interested by the subject & John’s assuring me the details were correct I read again & was entertained with following this sad retreat – the anecdotes amuse & the descriptions stript of their flowery apendages seem just – Partial as the Author was to Sr J. Moore & not informed of any thing correctly beyond what he saw from his narrative It appears to me that there was a great want of Judgment of some sort in the whole business, & great despondency at the close not one precautionary regulation of the commander is brought forward – not one interference marked by cool discipline all went off as they could - Ill humours & disappointedness producing every possible evil.

While this is not a reflection on the monody, it certainly gives us a firm sense that both Larpents were interested in the subject of Moore. We may even speculate that this is partially a retrospective justification of the withdrawal of the licence, given the passage’s disapproval of ‘flowery apendages’ to the undoubted mismanagement of the battle of Corunna (see ‘Commentary’ below)..

Commentary

The manuscript has no marks of intervention by the Examiner or indeed anyone else. It is included here as it is a very rare example of post-performance censorship. Although John Larpent’s account books record that the monody had its ‘Licence refused’ (f.18v), this is not, strictly speaking, true. The licence was rather withdrawn after initial approval. As Lewis outlines in the prefatory advertisement to the published version (May 1809):

These lines were recited twice on Drury-Lane stage with considerable applause, for which they were probably indebted entirely to the subject: but on the third night an order from the Lord Chamberlain absolutely prohibited their further repetition’ (Lewis, n.p.).

The reason for the Lord Chamberlain’s intervention is quite straightforward. Sir John Moore (1761-1809) was killed in action on 16 January 1809. The commander of substantial British forces during the Peninsular War, Moore had retreated from vastly superior French forces to the city of Corunna by January 1808. His men were exhausted, disorganized, and completely ill-prepared for battle. While his men were embarking on transports, he led a fatal counter-charge against the pursuing French; he died from cannon shot wounds. Moore’s DNB entry, drawing on a statement of General Orders issued by the Horses Guards (which can be read in full in The Aberdeen Journal, 15 February 1809), paints him in a decidedly Romantic hue. It is worth noting that Moore’s death had further literary appeal: it was also the subject of a poem by Charles Wolfe—youngest son of Irish revolutionary Wolfe Tone—titled ‘The Burial of Sir John Moore’ (1816); this in turn was inspired by a reading of Robert Southey’s account of Moore’s death in the Edinburgh Annual Register. In 1822, no less an authority than Byron declared Wolfe’s poem ‘the most perfect ode in the English language’ (Edwards, n.p.). Two years later Mary Mitford also remembered him with ‘To the memory of Sir John Moore’ (1811). Evidently, Moore’s death was an event which lent itself to widespread literary pathos (for more, see Saglia 161–63).

However, a contemporary report printed in the Morning Chronicle (14 February 1809) reveals the magnitude of the military disaster, notwithstanding Moore’s courage and purported military prowess in enabling the escape of his men:

The 42d, 50th, and 52d British regiments were utterly destroyed in the battle of the 16th. General MOORE was killed charging at the head of his brigade […] The night after the battle of the 16th, the enemy entered Corunna in the greatest consternation and confusion; out of 80 pieces of cannon which had been landed, only one dozen were re-embarked. The French kept possession of 60 pieces. Independently of the immense treasure the English had taken, a great quantity had been thrown from the precipices, which had been found by the peasants. Previously to, and in the battle of Corunna, two English Generals had been killed, and three wounded; among the latter was General CRAUFORD. The French found in the port of Corunna seven English vessels, three with horses, four with troops. They had taken from the English every thing which constitutes an army.

The English have gained nothing by the expedition but the hatred of the Spaniards, and disgrace.

A subsequent parliamentary debate in May 1809 indicates that George Tierney, Whig MP, politicized Moore’s death, suggesting that it was a direct result of ministerial negligence. We know from Lewis’s publication of the Monody in May 1809 (the prefatory address is dated 13 May) that it was Tierney’s intervention that provoked the publication:

In the debate of Tuesday May the 9th, Mr. Tierney, among other reasons for his suspecting Ministers of underhand attempts to tarnish the merits of Sir John Moore, stated the above fact: and such public notice having been taken of the prohibition of the Monody, I think it necessary to print it, lest the Public should suppose that it contained something objectionable either in a moral, religious, or political view. From what motive the recitation of these lines was forbidden, I shall not venture to give an opinion: but in justice I must add, that Mr. Percival in the House of Commons positively denied any knowledge of the prohibition; and that, from the manner of Lord Castlereagh and Mr. Canning, it was understood, that they also disclaimed any concern in it. (Lewis; a full report on the debate can be read in the Morning Chronicle, 10 May 1809)

What is less clear is the extent of any furore at the time of public recitation that prompted Dartmouth, Lord Chamberlain, to withdraw the licence at the time of performance. There is no indication in the press reports that the theatre audiences were provoked into anti-ministerial sentiment. Ministerial politicians were quick to disavow any knowledge of the prohibition in parliamentary debate so it is perhaps simply a case of overly prudent political censorship.

Further reading

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, Huntington Library, HM 31201, v7: f.236v.

John Larpent’s Account Books, Huntington Library, HM 19926.

Morning Chronicle, 14 February and 10 May 1809.

M. G. Lewis, Monody on the Death of Sir John Moore recited at Drury-Lane Theatre By Mrs. Powell, Prohibited on the Third Night by the Lord Chamberlain, and Quoted by Mr. Tierney in the House of Commons on Tuesday May 9 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1809), np.

[available on Googlebooks]

James Carrick Moore, A Narrative of the Campaign of the British Army in Spain, Commanded by His Excellency Lieut-General Sir John Moore (London: Joseph Johnson, 1809).

[available on archive.org]

[Robert Keir Porter], Letters from Portugal and Spain, written during the march of the British troops under Sir John Moore (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1809)

[available on archive.org, HathiTrust.org]

Diego Saglia, Poetic Castles in Spain: British Romanticism and Figurations of Iberia (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000).

[Margaret Harries Wilson], Life and correspondence of M. G. Lewis, with many pieces in prose and verse never before published, 2 vols. (London: H. Colburn, 1839).

[available on archive.org, Googlebooks]