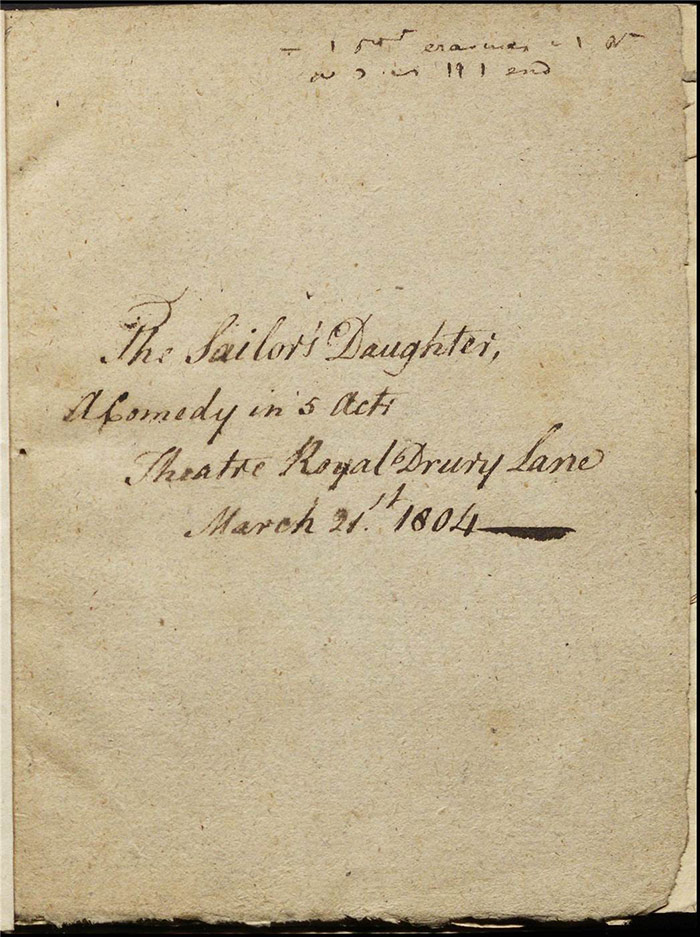

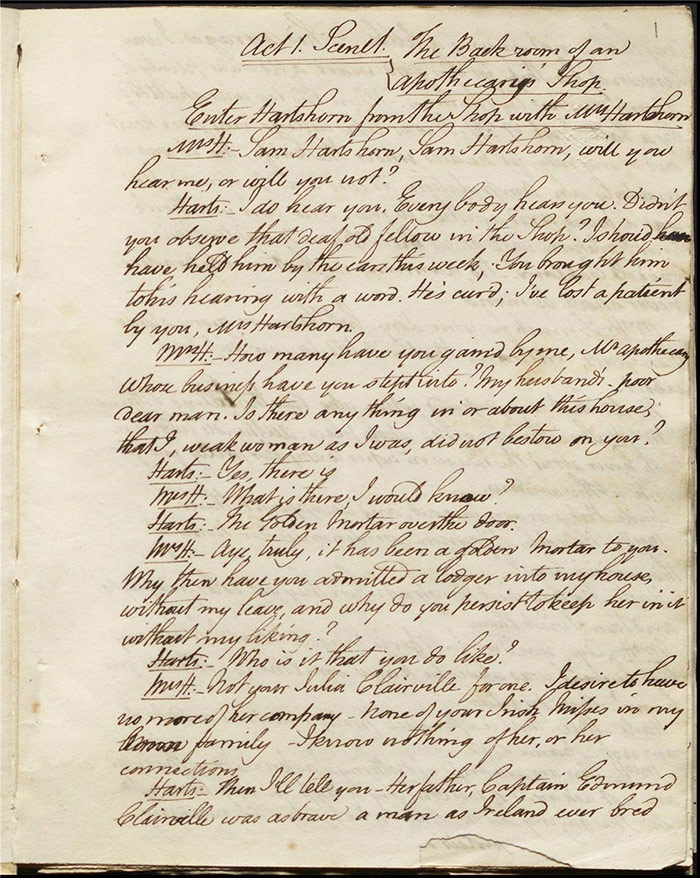

The Sailor’s Daughter (1804) LA 1409

Author

Richard Cumberland (1732-1811)

Cumberland attended Westminster School, where his classmates included William Cowper, Charles Churchill and George Colman, before studying at Cambridge. Although he went on to be best known for his comedies, his first serious dramatic effort was The Banishment of Cicero (c.1759), a history play but David Garrick would not stage it. Cumberland held various administrative and diplomatic positions within the British state apparatus from the 1750s until his retirement around 1780.

Throughout and after this time Cumberland wrote novels, poetry and periodicals as well as plays. He wrote 152 essays for The Observer, a periodical which appeared in five volumes 1786-1790 and he produced an 8-book epic poem Calvary; or, the Death of Christ (1792) which went into an American edition. His Memoirs of Richard Cumberland (1806-7) is an important source for theatre historians; there is also a less well known self-reflective poem Retrospective which was published in 1811.

However, despite this substantial body of work, Cumberland is primarily remembered as a dramatist today. The West Indian (1771) , a sentimental comedy, is his best known play. It was an enormous success and featured the character Major O’Flaherty, one of the earliest examples of the benevolent Stage Irishman, and the play earned him an honorary doctorate from the University of Dublin. He had further successes with The Jew (1794) and The Wheel of Fortune (1795): the former rehabilitated the Stage Jew and the latter’s Penruddock was one of John Kemble’s more important roles.

Cumberland also had regular encounters with the Examiner of Plays before The Sailor’s Daughter. The Brothers (1770) had some passages excised as did The Mysterious Husband (1783) and The Box Lobby Challenge (1794). Notably, his Richard II (1792) was one of the few plays refused a licence outright by Larpent. Anna Larpent recorded reading this manuscript on 8 December 1792 in some detail:

Evening I worked at the Chair & Mr Larpent red loud a MSS offered for Licensing An Opera Richard the 2d written by Cumberland it appears extremely unfit for representation at a time when the Country is full of Alarm, being the Story of Wat Tyler the killing of the Tax Gatherer &c. very ill judged. ye poetry pretty & the whole really written with taste. (Diary of Anna Larpent)]

Cumberland’s relationships with his dramatic peers was suspect. Garrick criticized him for being unable to accept any criticism while Sheridan lampooned him in The Critic (1779) as Sir Fretful Plagiary, an onomastic jibe if there ever was one. Nonetheless, he was a member of Johnson’s Literary Club and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Plot

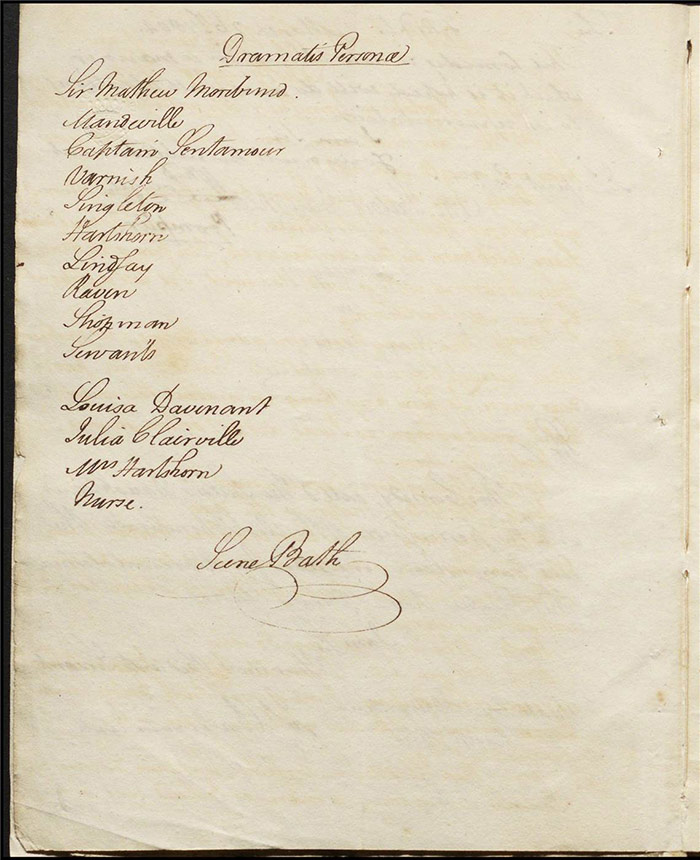

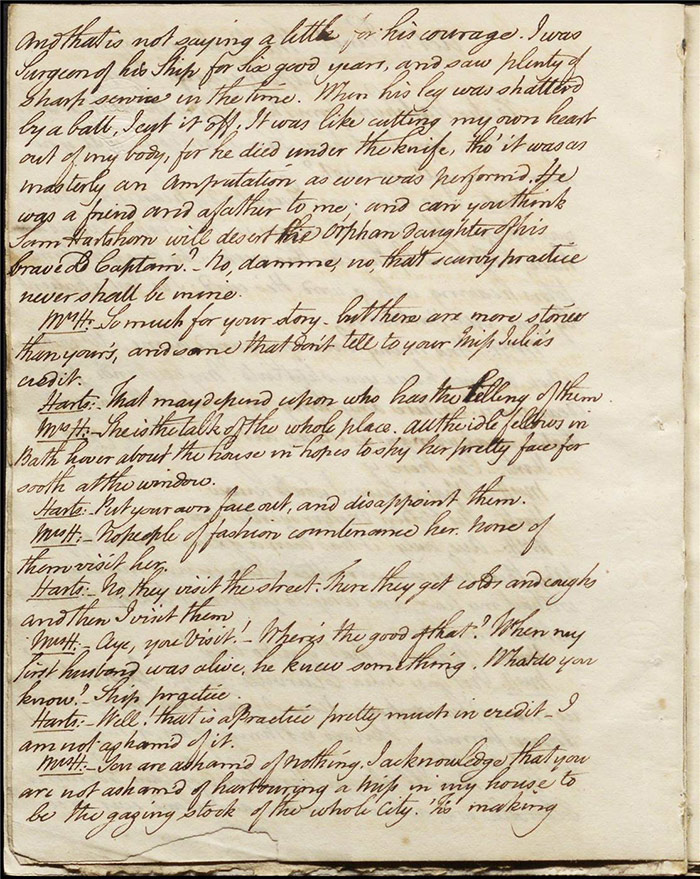

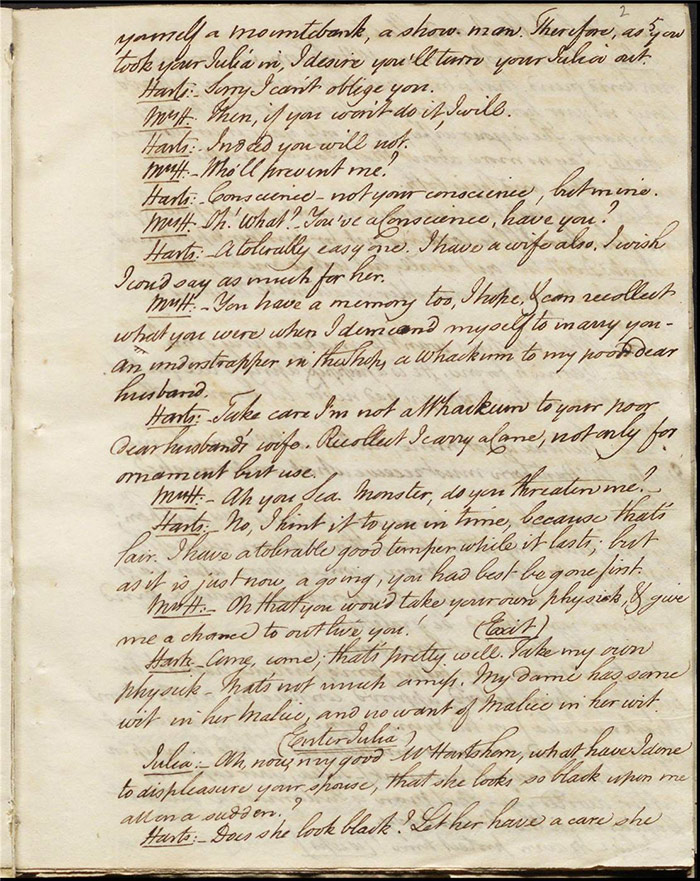

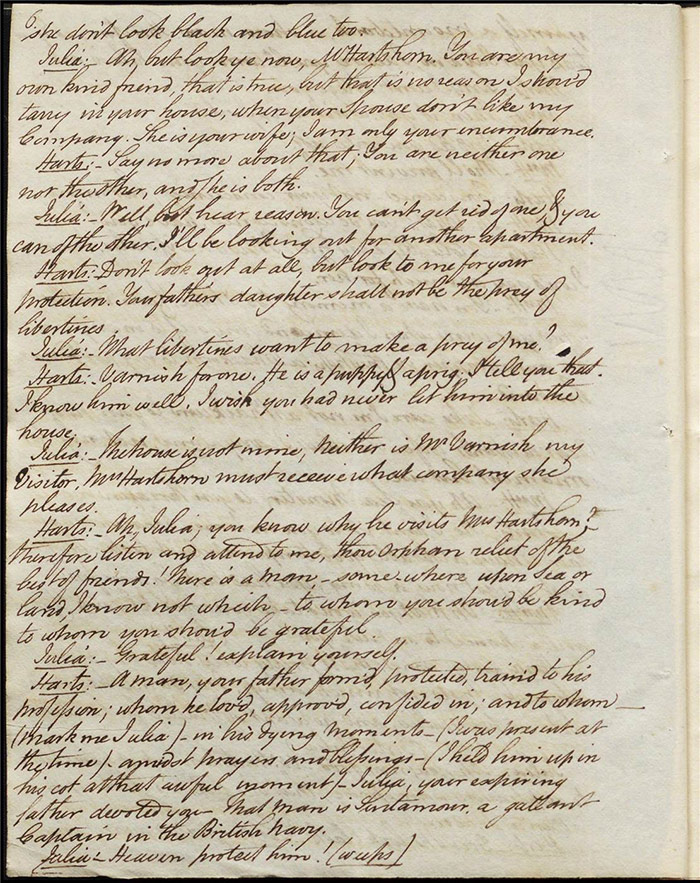

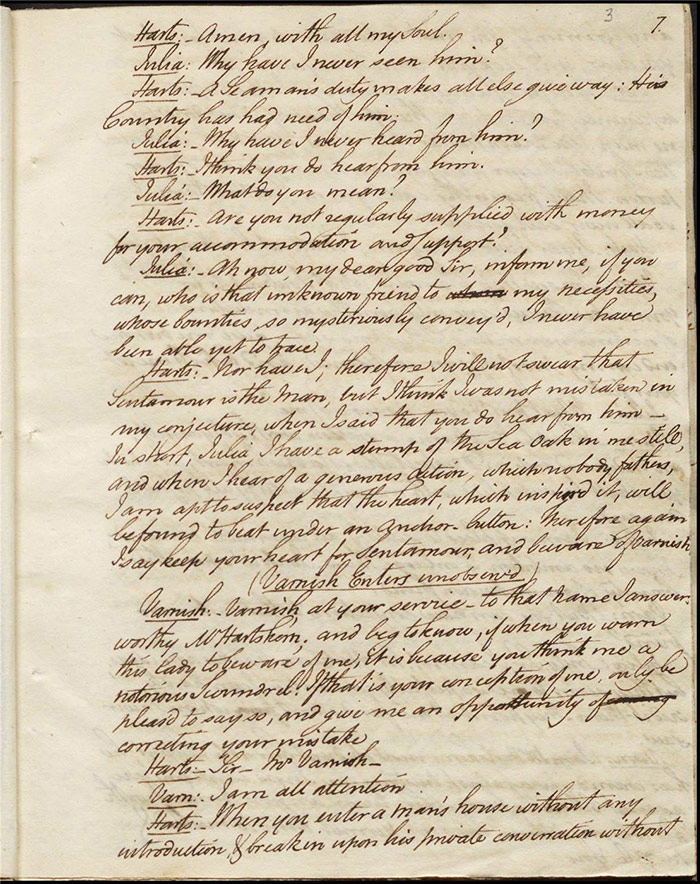

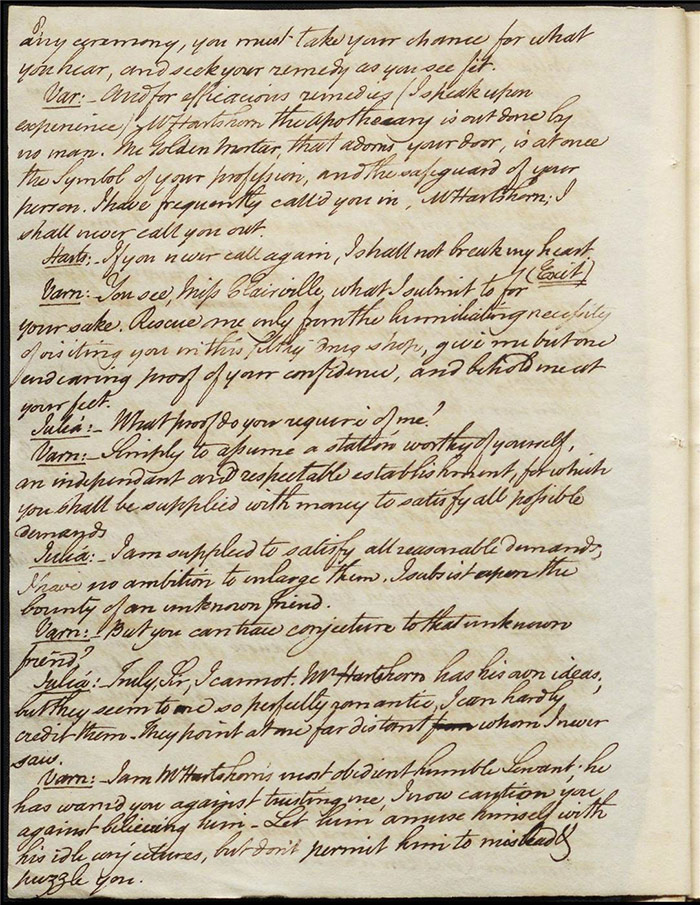

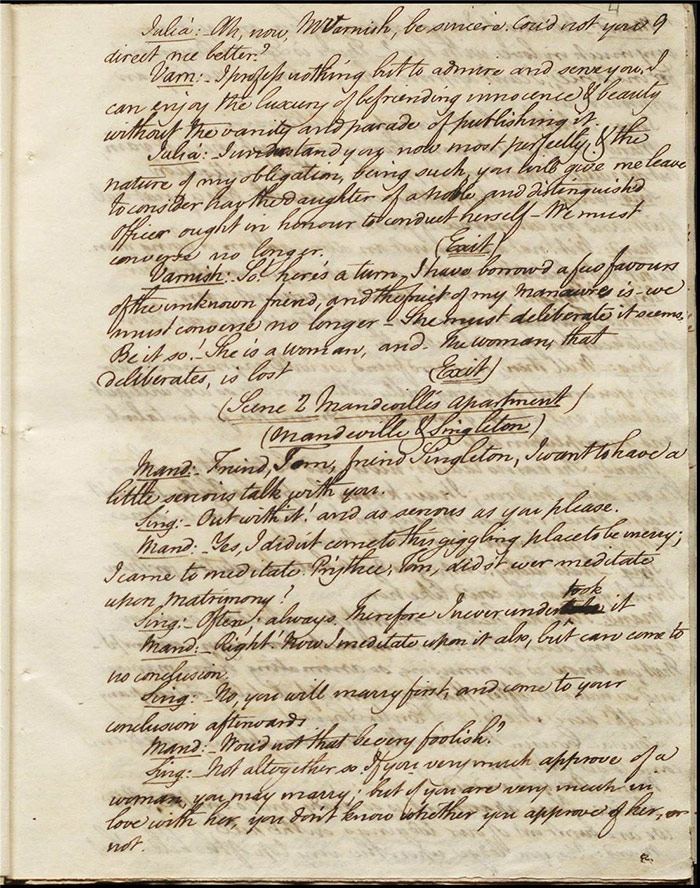

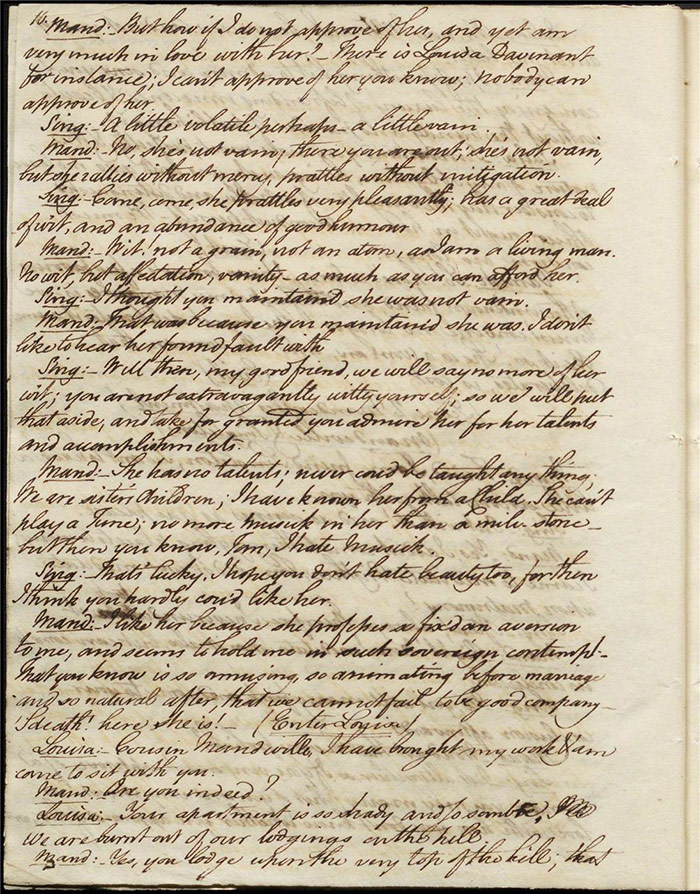

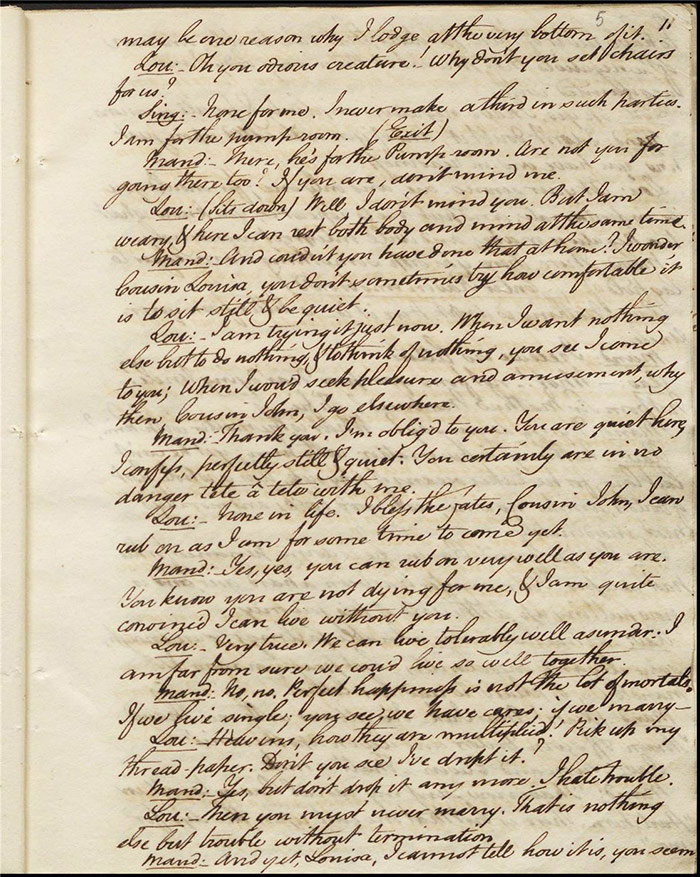

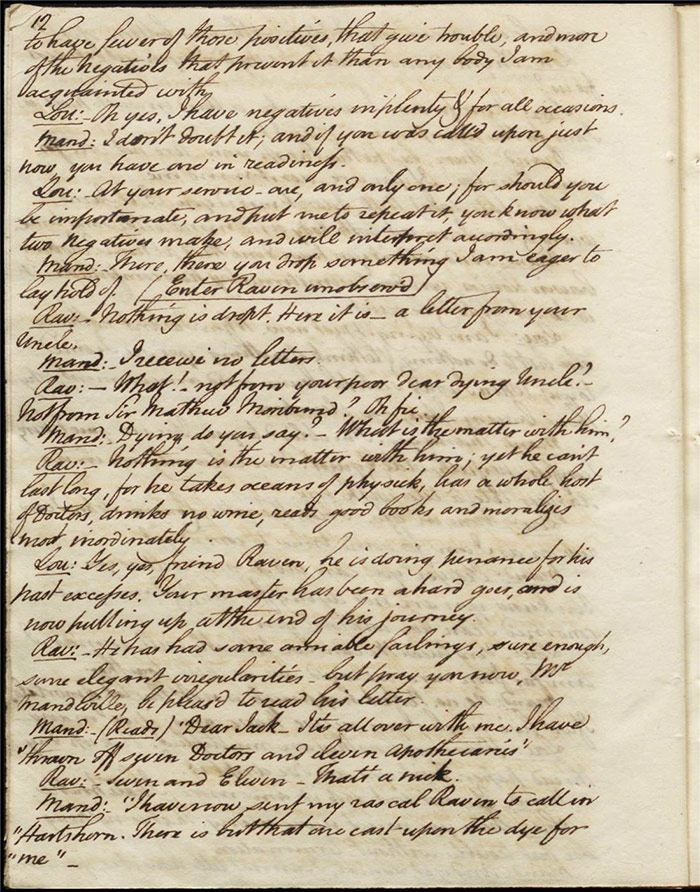

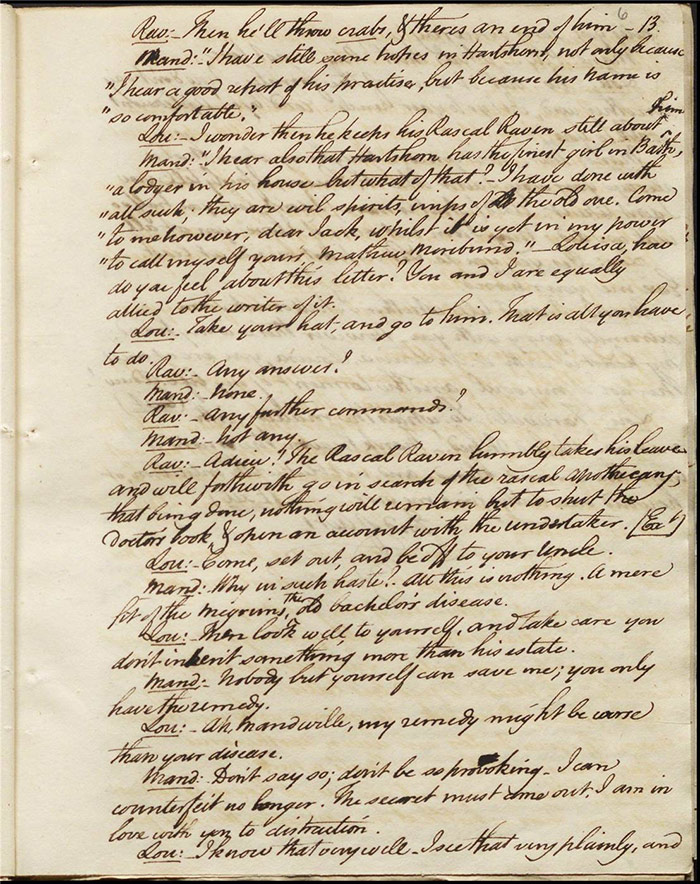

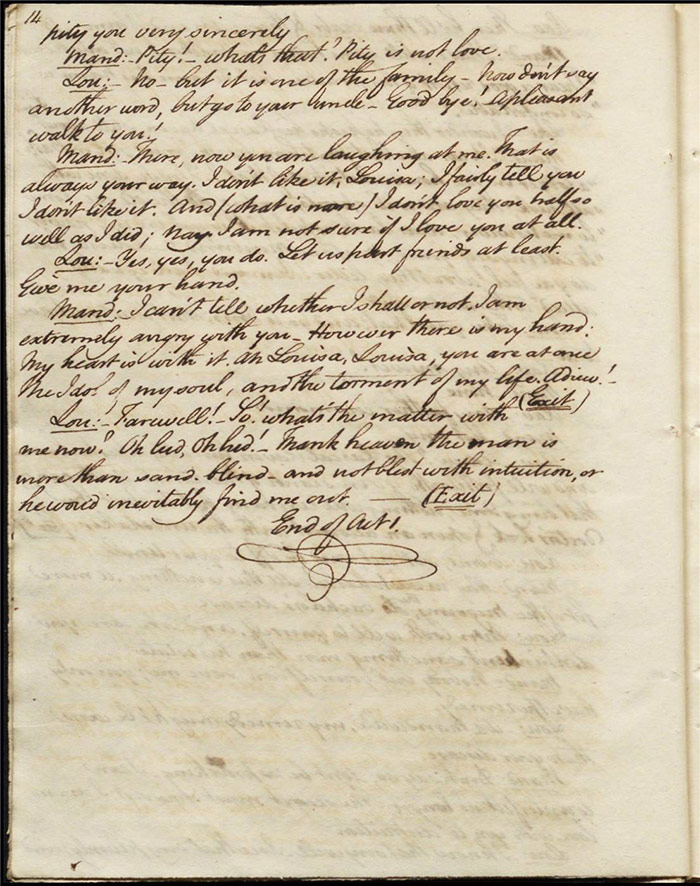

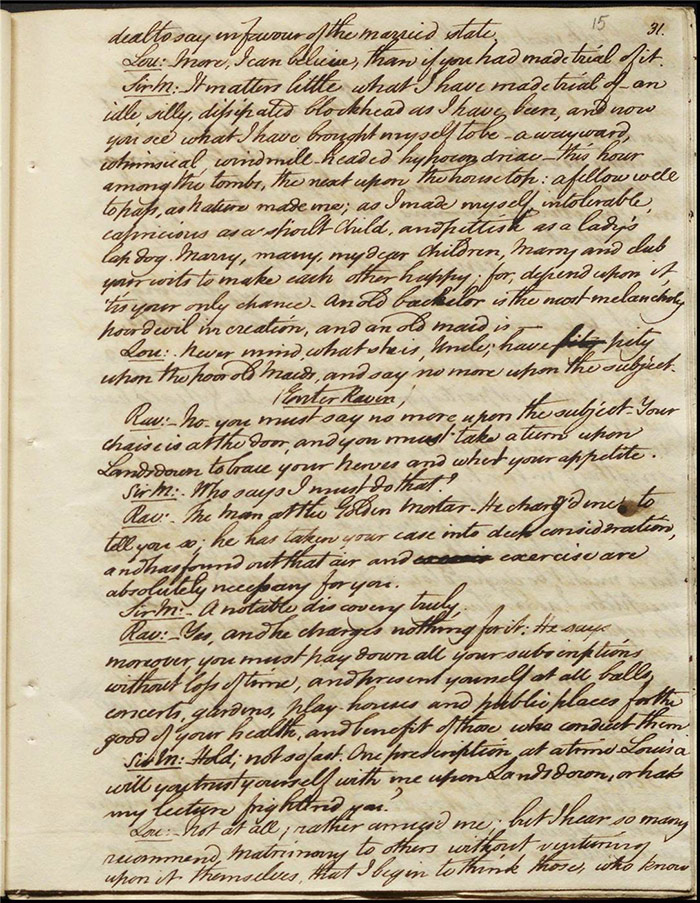

Hartshorn, an apothecary, quarrels with his wife. She wants rid of his beautiful ward, Julia, orphaned daughter of his Irish friend but he is unbending in his duty. He tells Julia that she is promised to her father’s protégé, Sentamour, a navy captain. He further suspects that Sentamour is Julia’s anonymous benefactor. However, the devious Varnish, who has designs on her, intimates that he might be the mysterious sponsor. Mandeville discusses marriage with his friend Singleton (f.4r). He admires Louisa but she is too vain for him. She enters and they quarrel. Raven delivers a letter from Mandeville’s uncle Sir Matthew Moribund. He claims that he is dying and, after consulting a host of doctors, Hartshorn represents his last chance. He asks that Mandeville attend him. Despite believing that this is all nonsense, Mandeville leaves to go to him but not before he declares his love to an apparently indifferent Louisa.

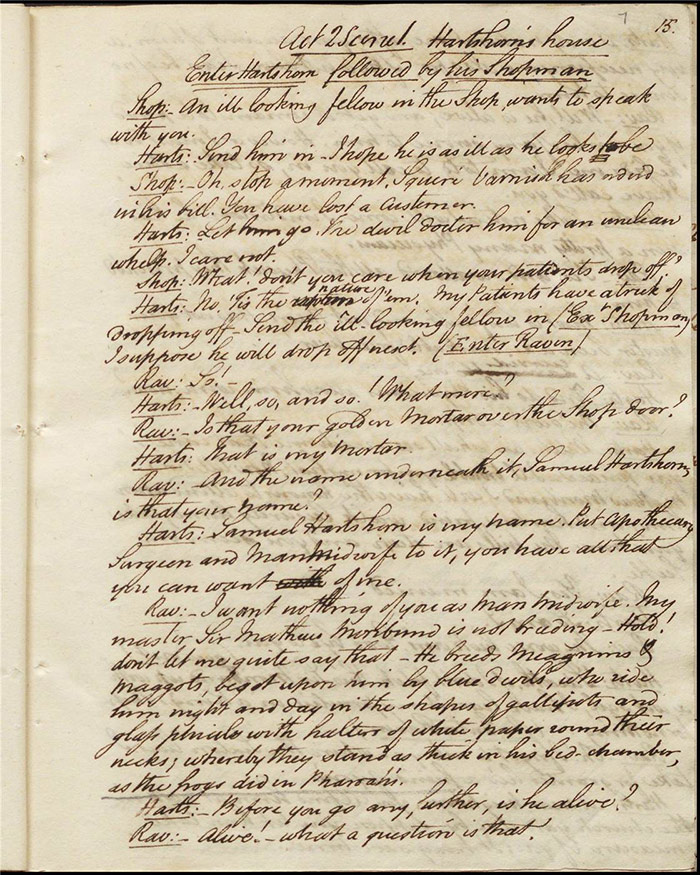

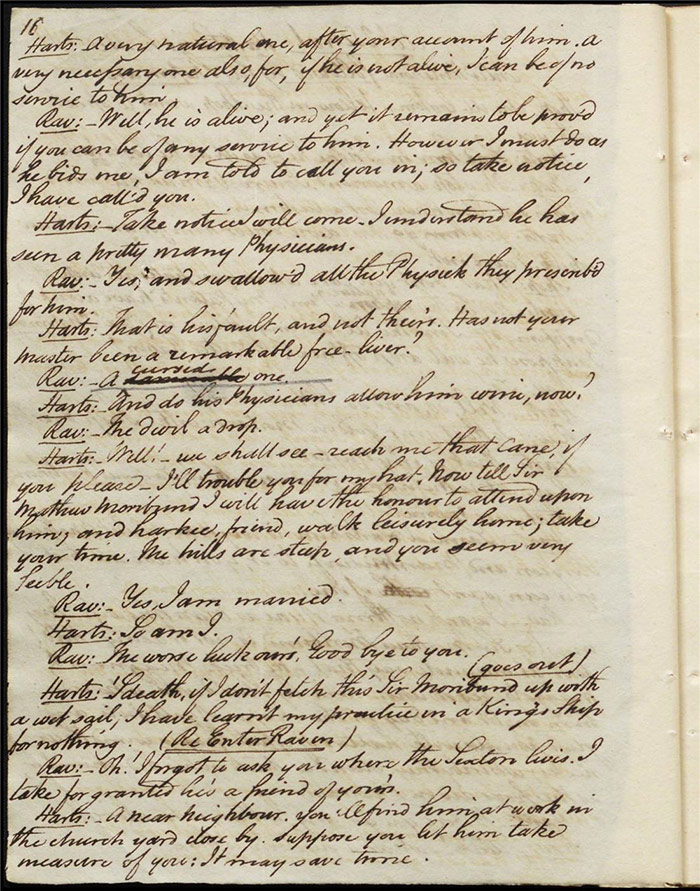

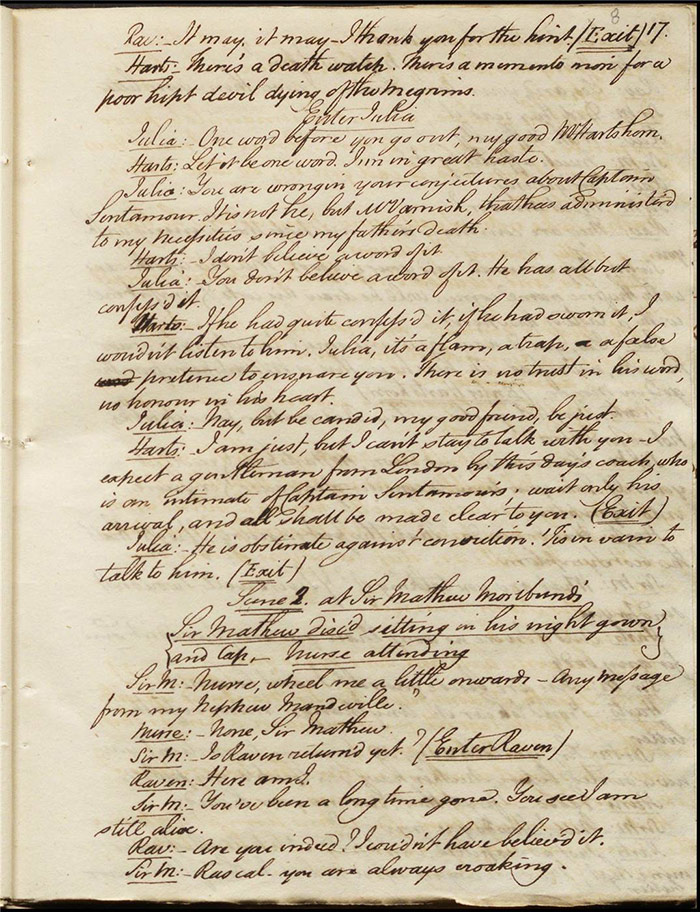

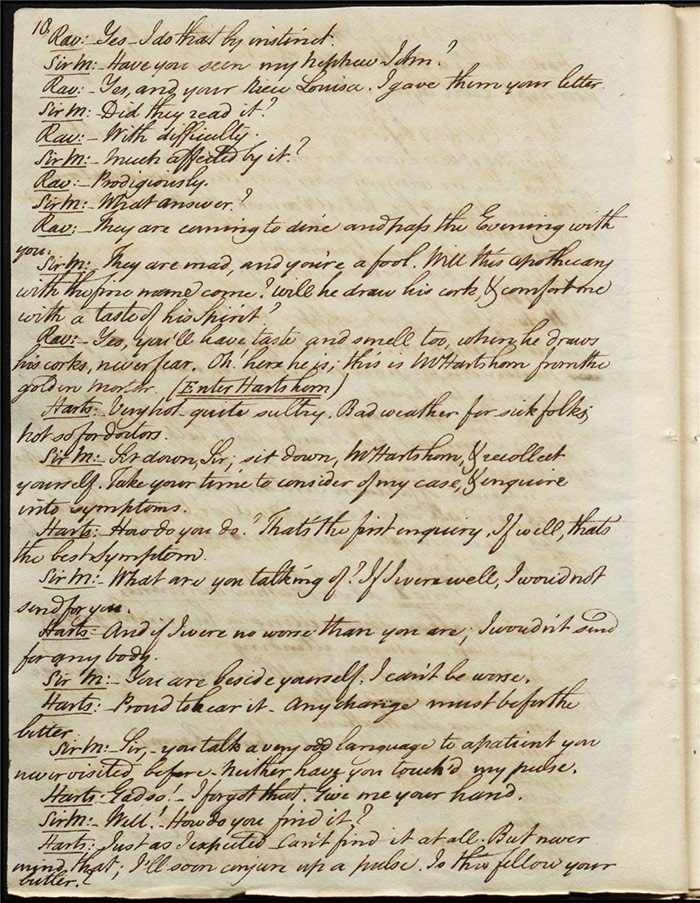

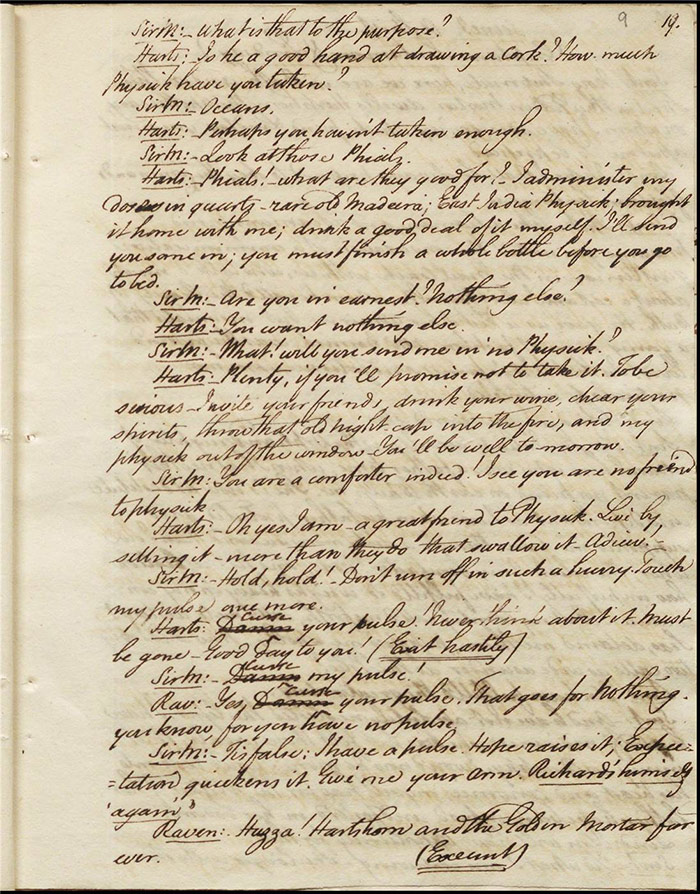

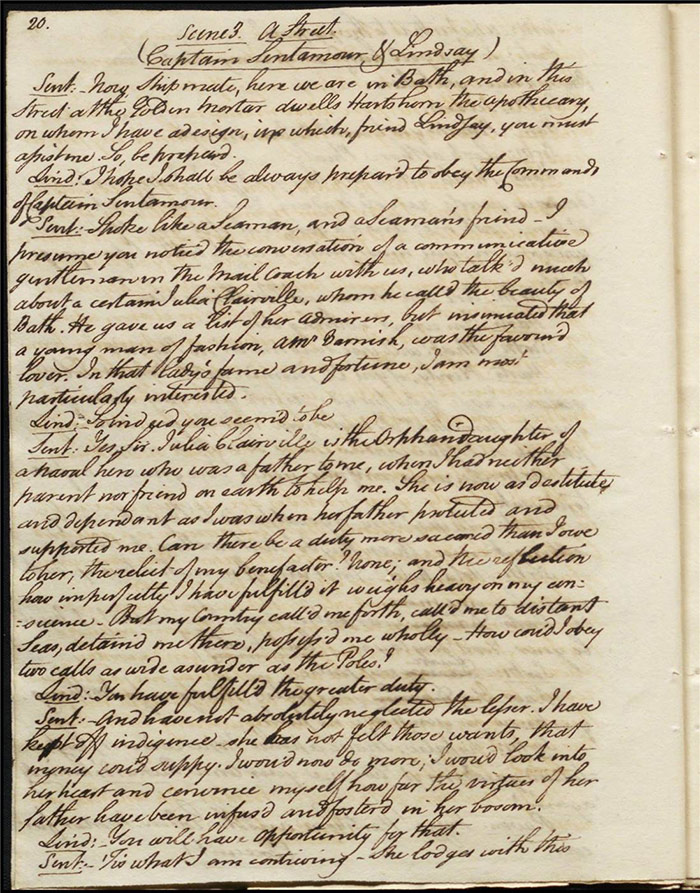

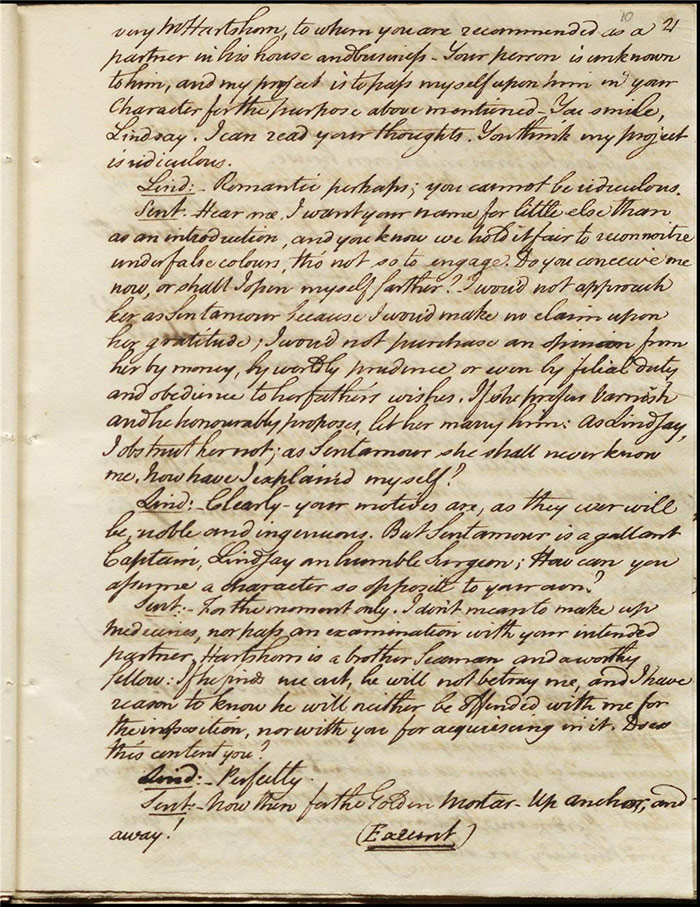

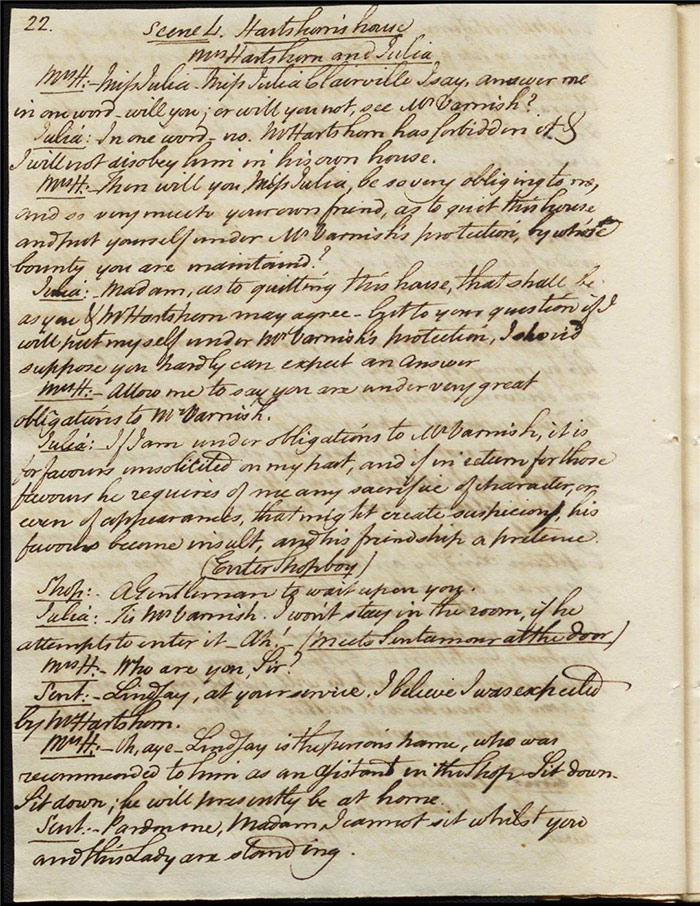

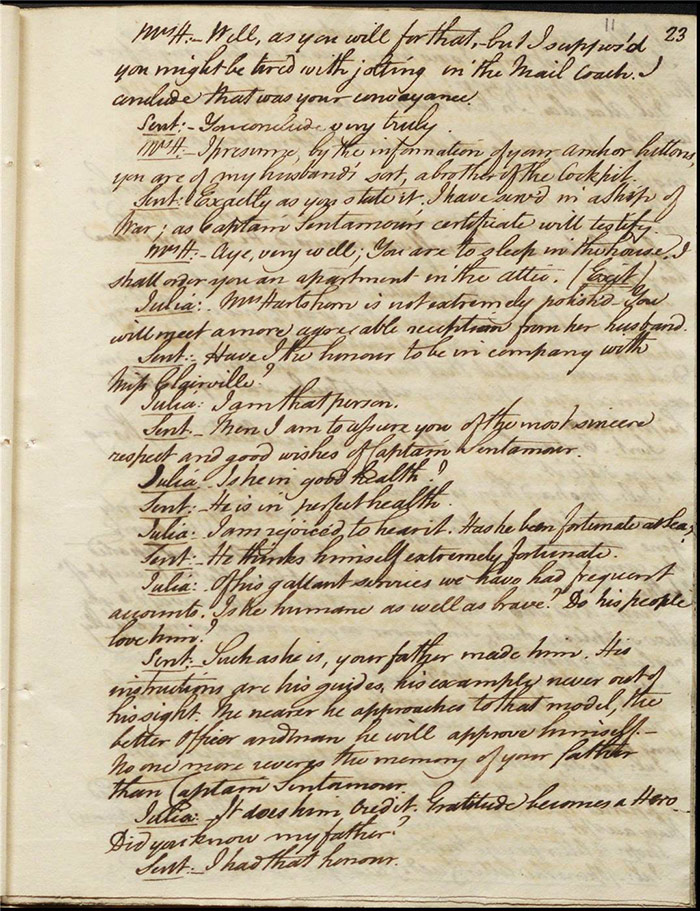

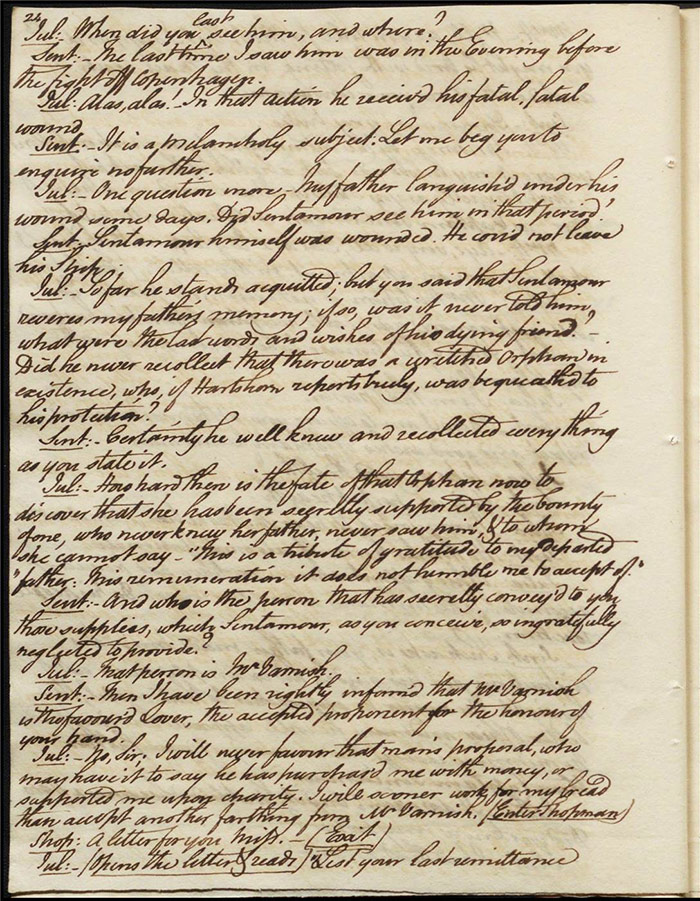

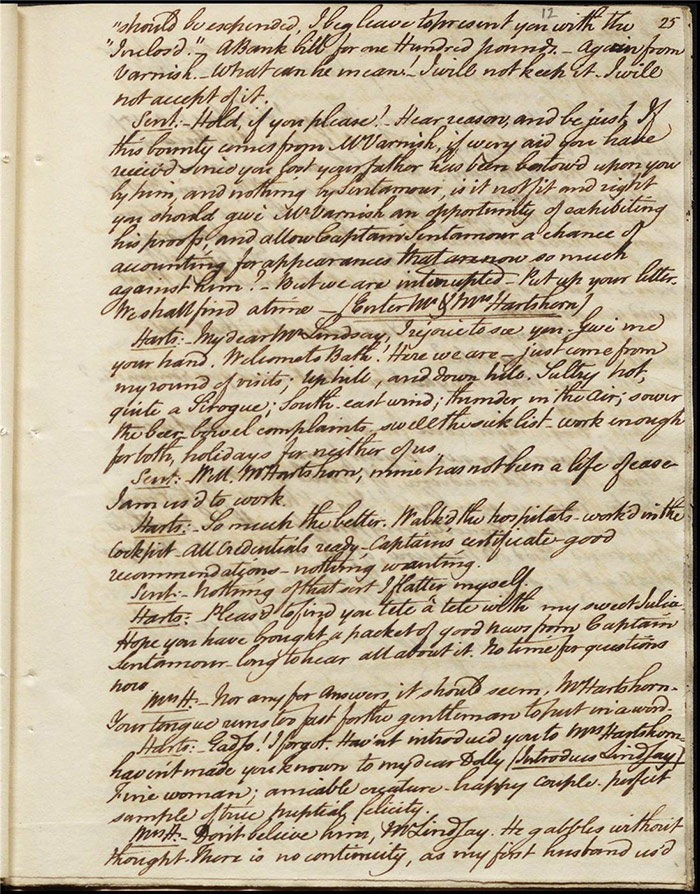

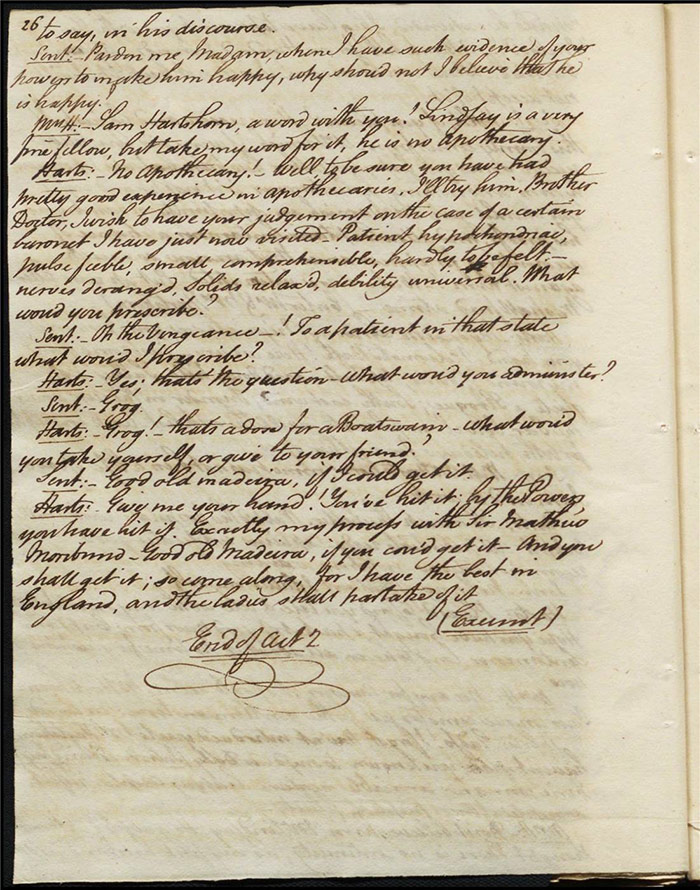

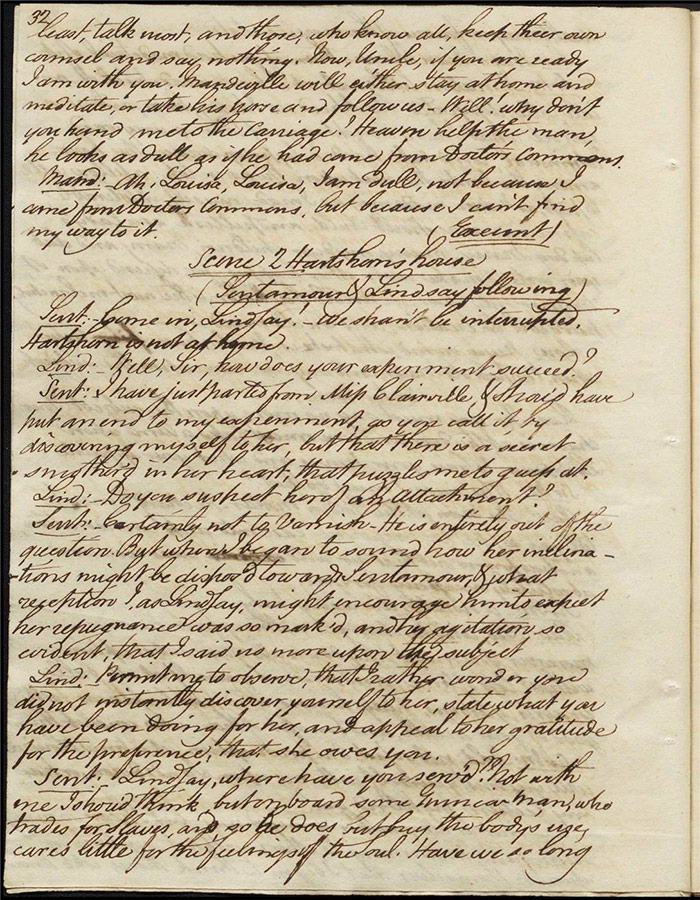

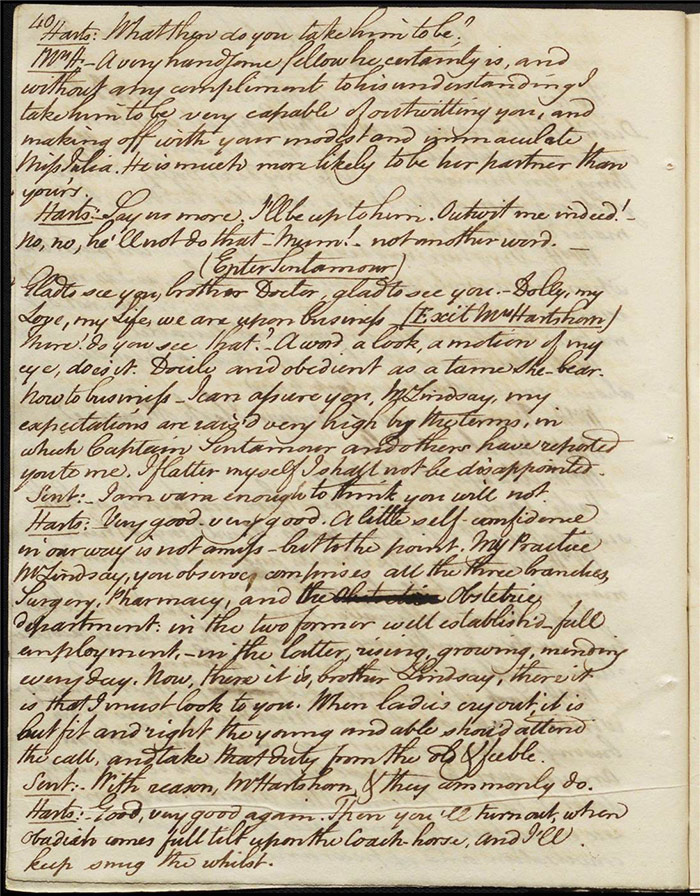

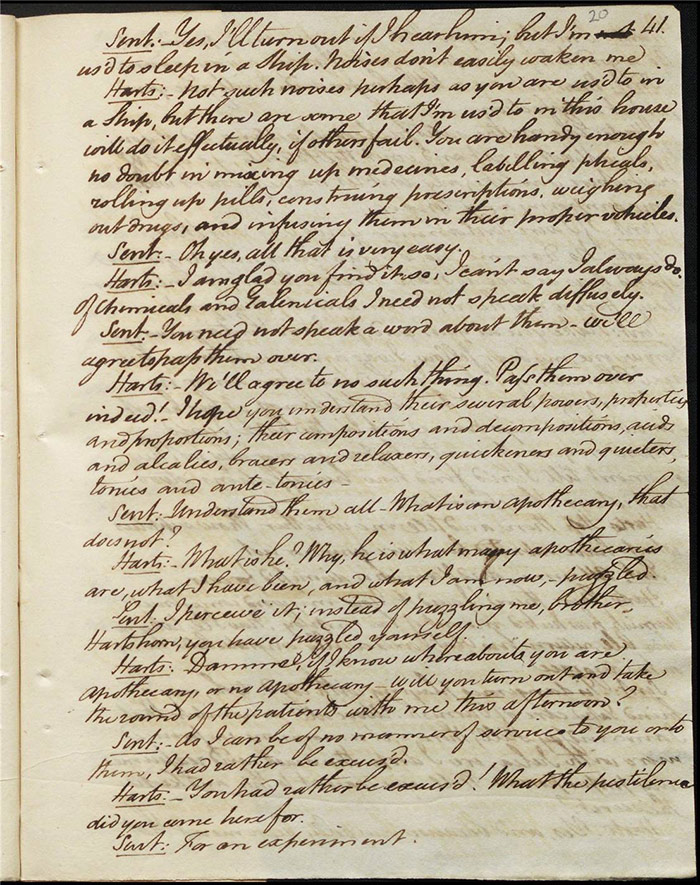

Raven calls on Hartshorn to request his services when act 2 opens; he agrees (f.7r). Julia tells Hartshorn that Varnish is in fact her secret benefactor but he dismisses the claim as a lie. Raven arrives back to Sir Matthew to tell him that Mandeville and Louisa are coming (f.8r). Hartshorn arrives and prescribes a bottle of Madeira for the skeptical Sir Matthew. Sentamour and his friend Lindsay arrive in Bath (f.9v). Sentamour determines to disguise himself as Lindsay to better gauge the true worth of Julia’s character by pretending to be a prospective assistant to Hartshorn. We also learn that he was indeed her true benefactor. Mrs Hartshorn puts pressure on Julia to go to Varnish (f.10v). Sentamour, as Lindsay, arrives. Julia and he talk and she simultaneously indicates that Varnish provides her with aid and that she will never marry him. Hartshorn enters and tests Sentamour’s credentials by describing Sir Matthew’s symptoms and asking for a prescription. He is delighted when Sentamour suggests grog or Madeira.

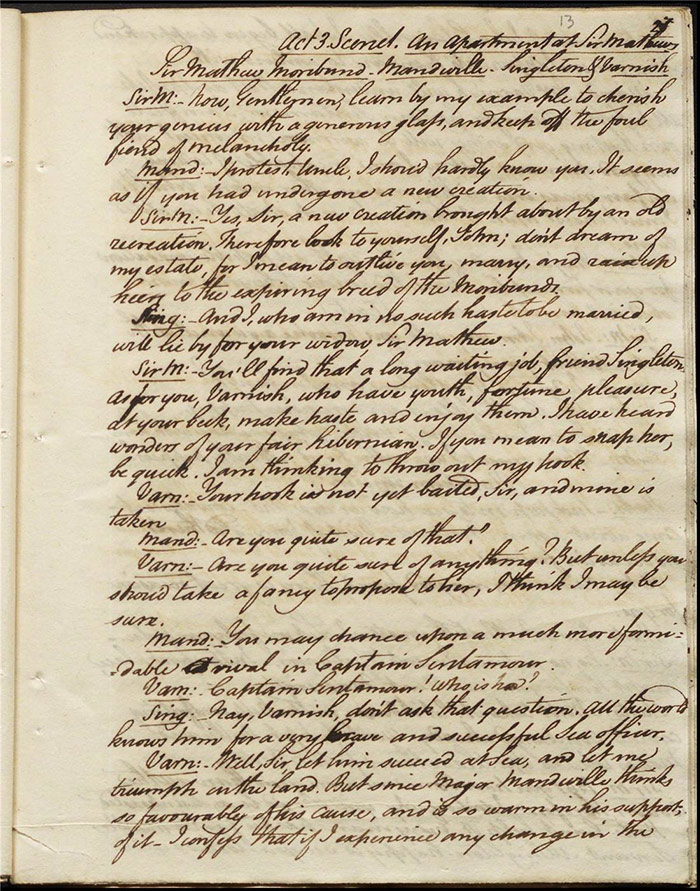

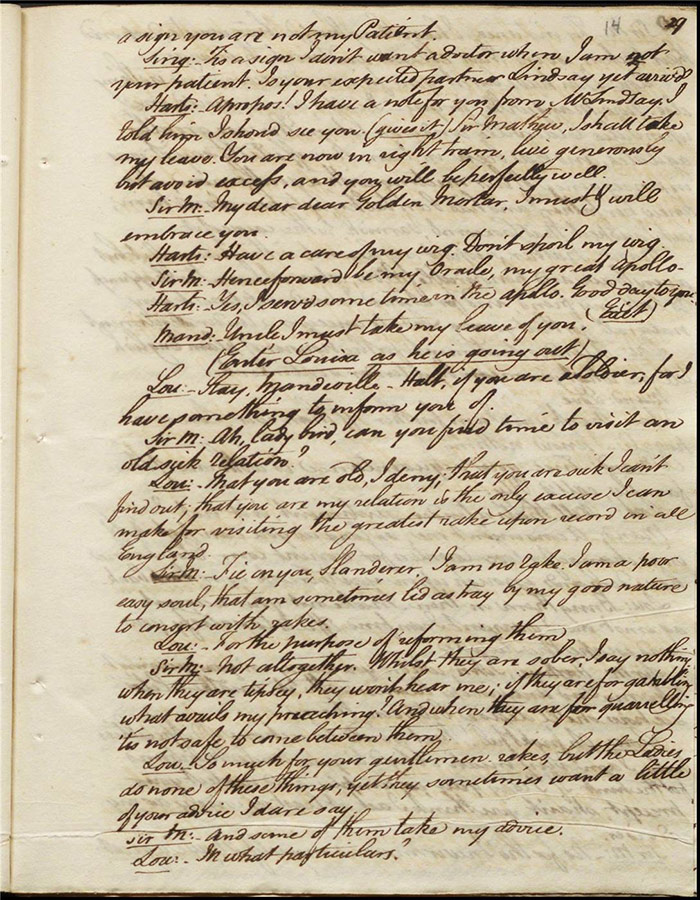

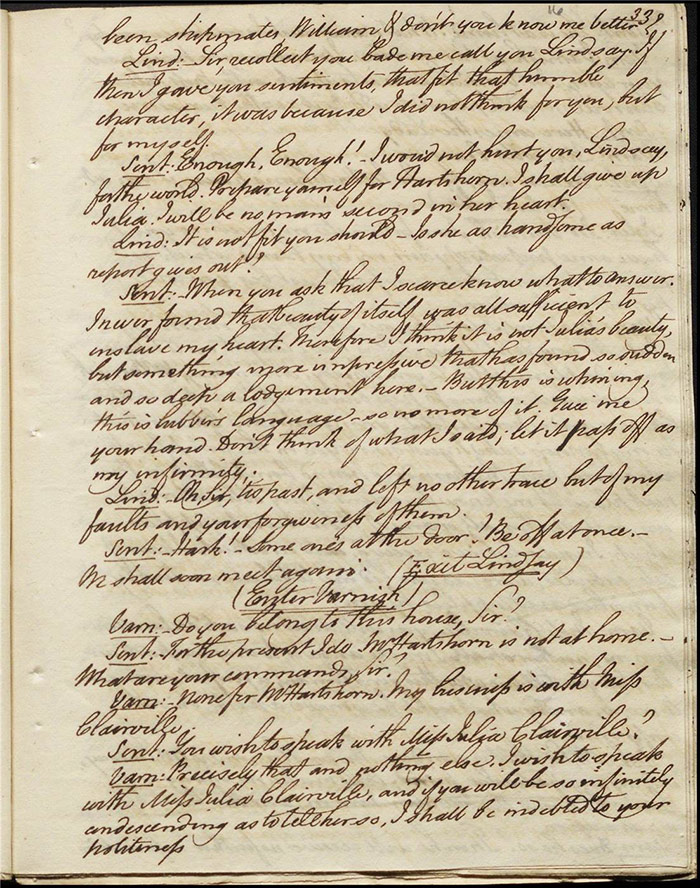

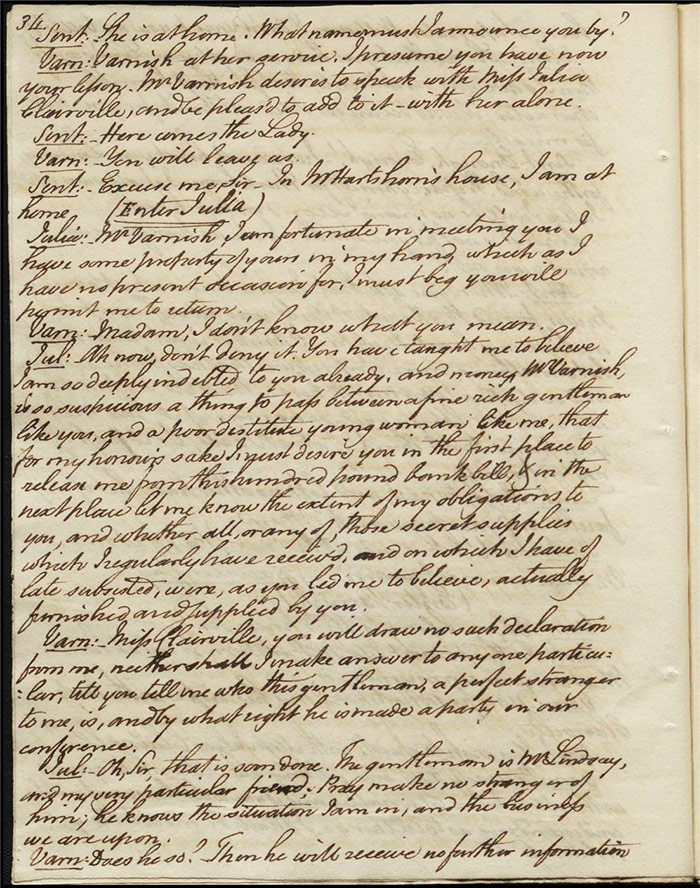

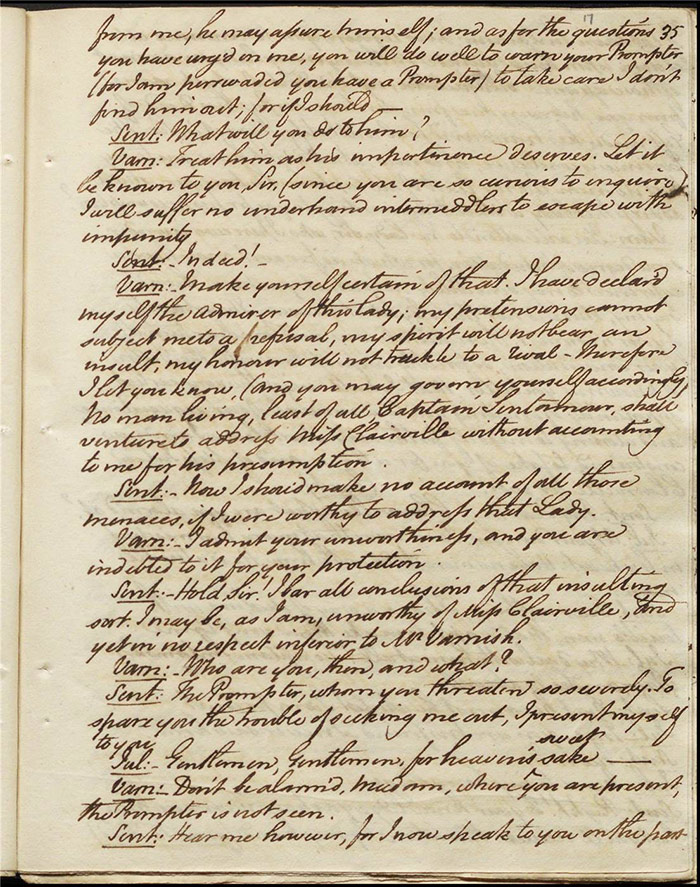

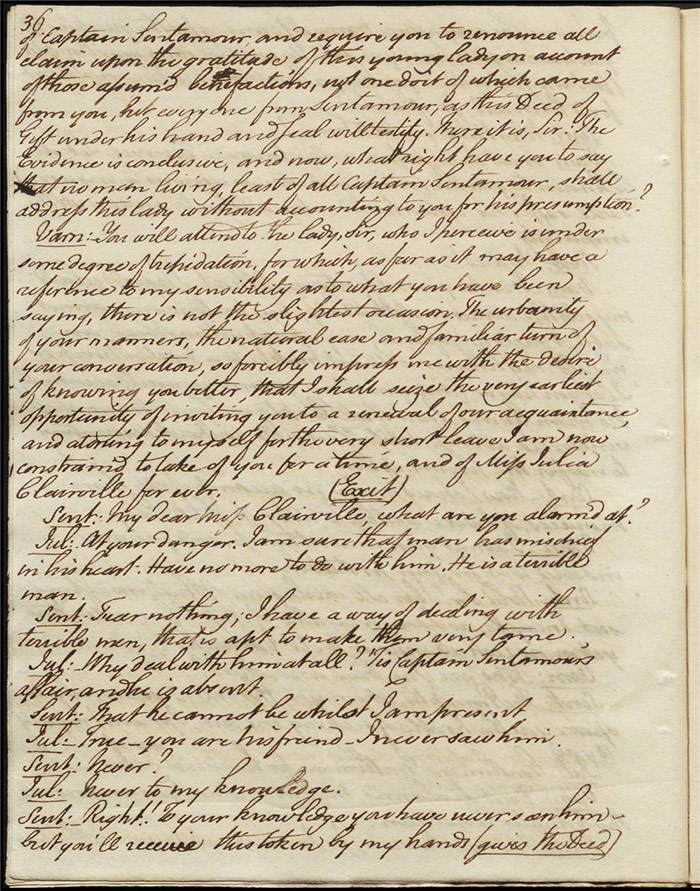

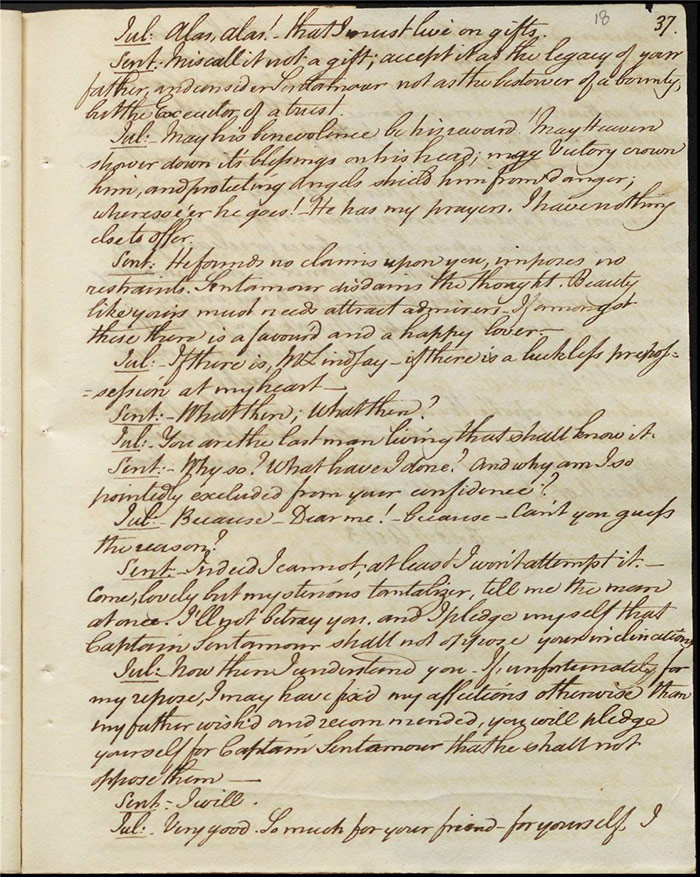

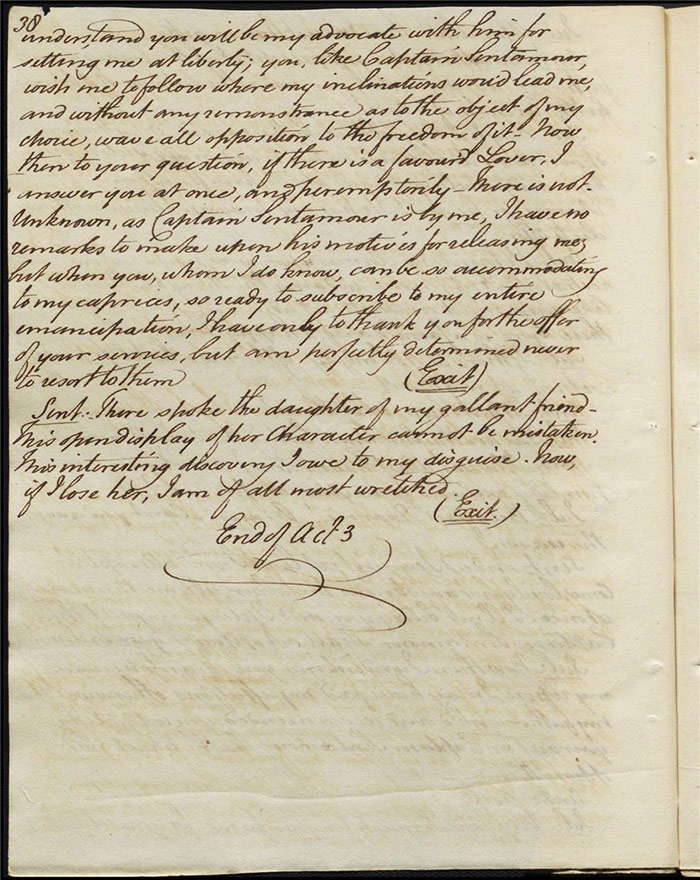

In act 3, a rejuvenated Sir Matthew declares that he might get married, perhaps even to Julia (f.13r). Mandeville tells Varnish about Sentamour. Hartshorn gives a note from Sentamour (as Lindsay) to Mandeville. Louisa reports that Julia has been upset at meeting someone who knew her father. Sir Matthew recommends that everyone get married. Sentamour meets Lindsay at Hartshorn’s and declares that he is giving up on Julia as she loves another (f.15v). Varnish arrives and Lindsay leaves. Varnish is looking for Julia. She appears and tries to give Varnish a £100 bill in order to free herself of any obligation to him. Sentamour, without revealing his identity, demands that Varnish admit he is no benefactor and renounce his claim to Julia. Varnish leaves, threatening the captain. Julia intimates that she is in love with Sentamour.

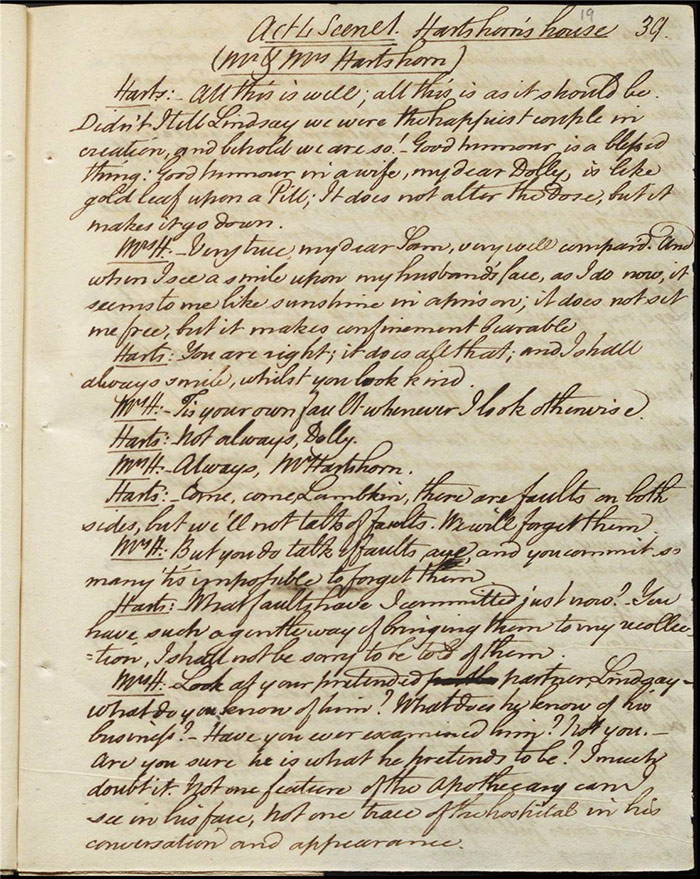

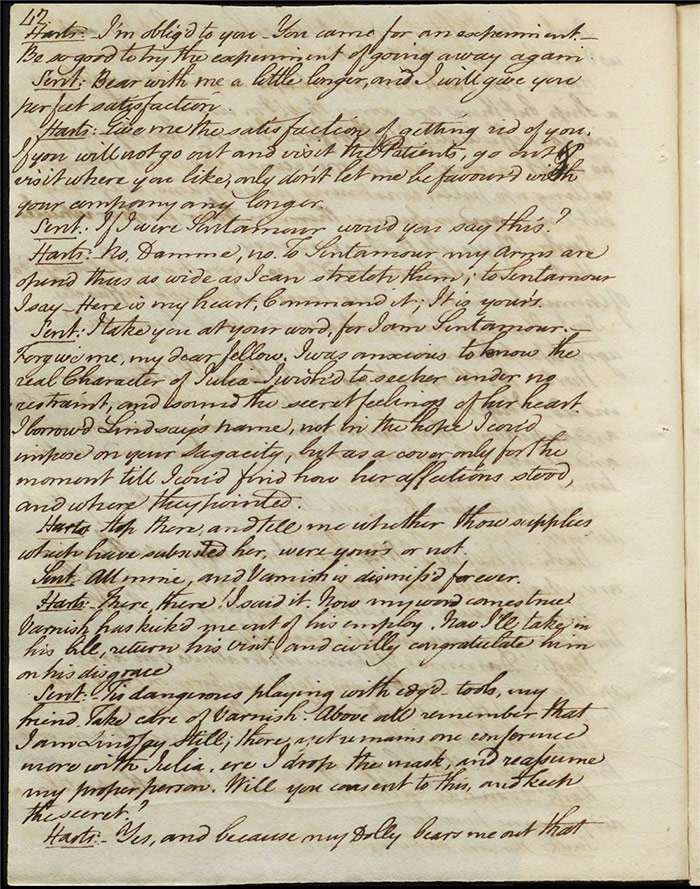

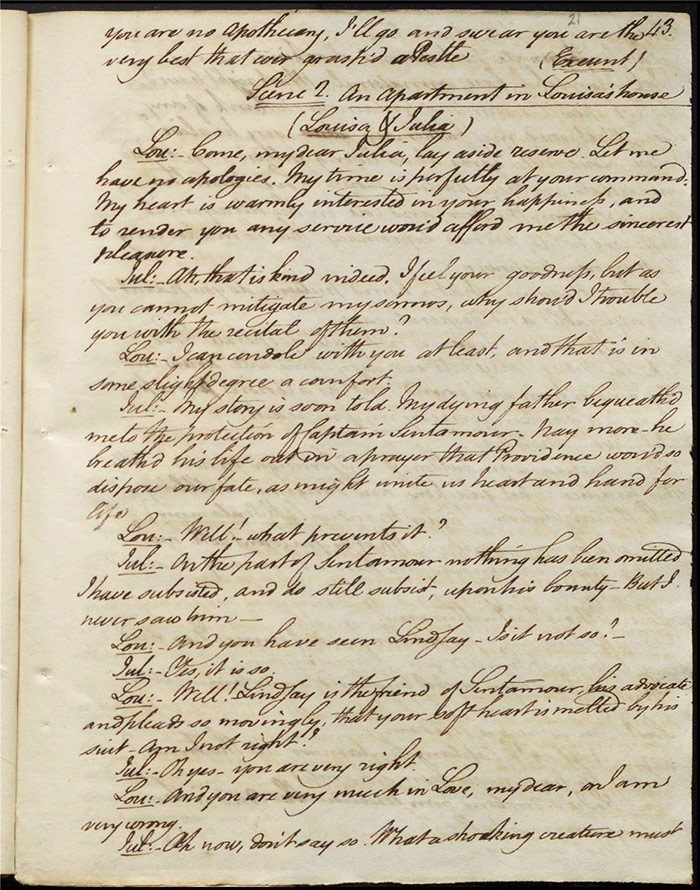

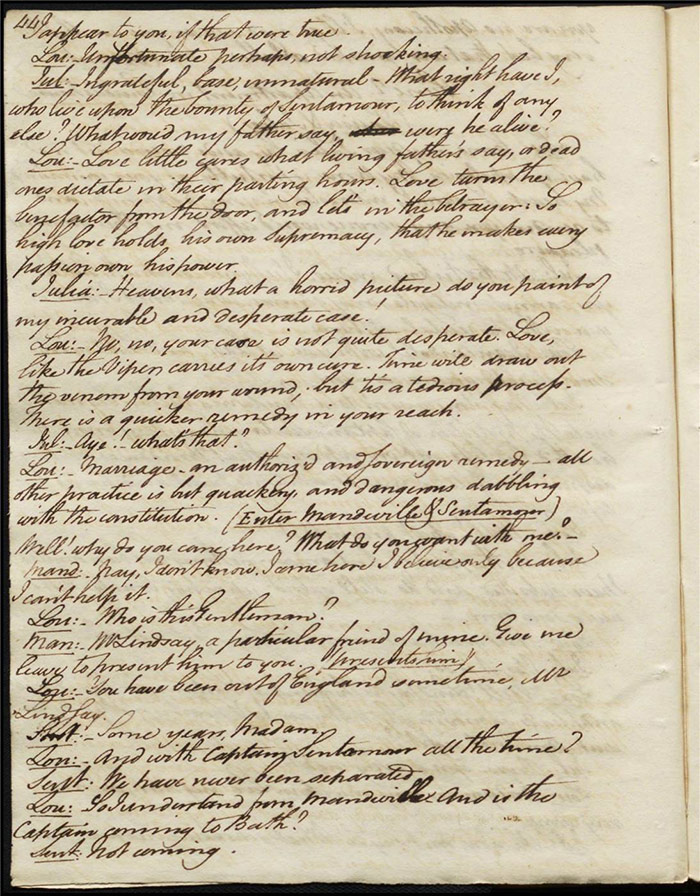

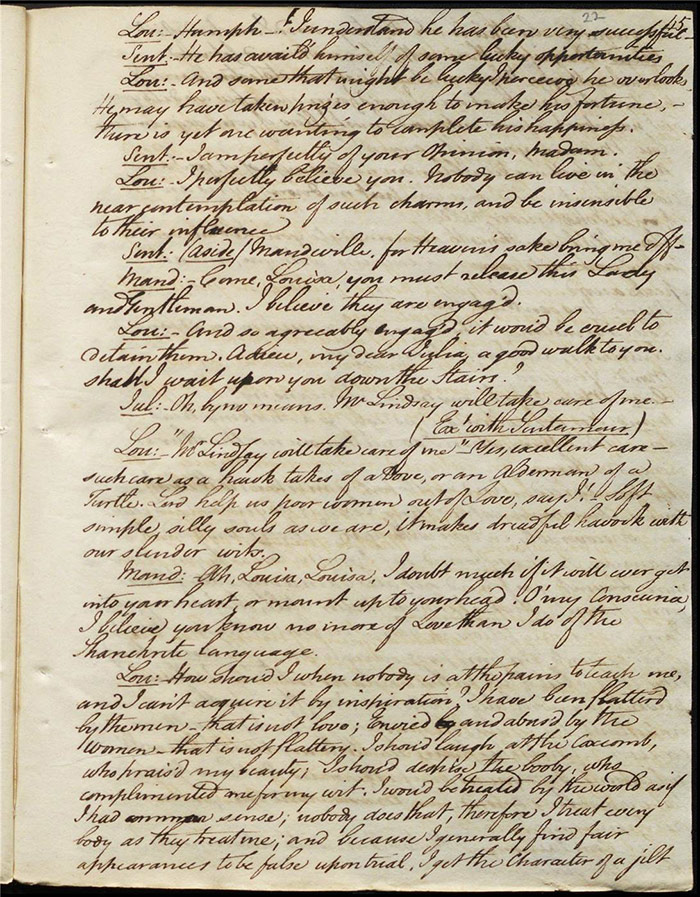

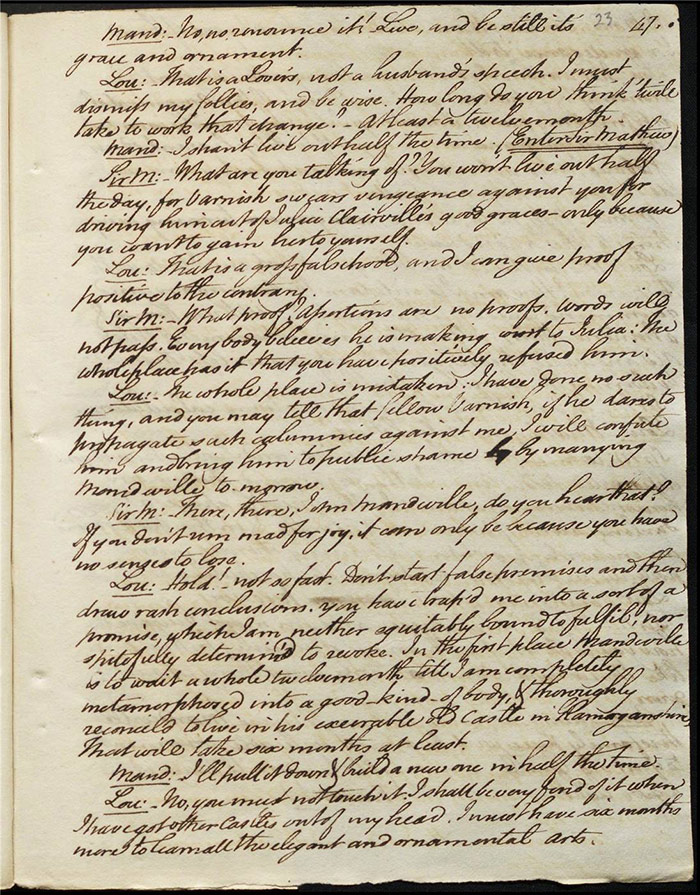

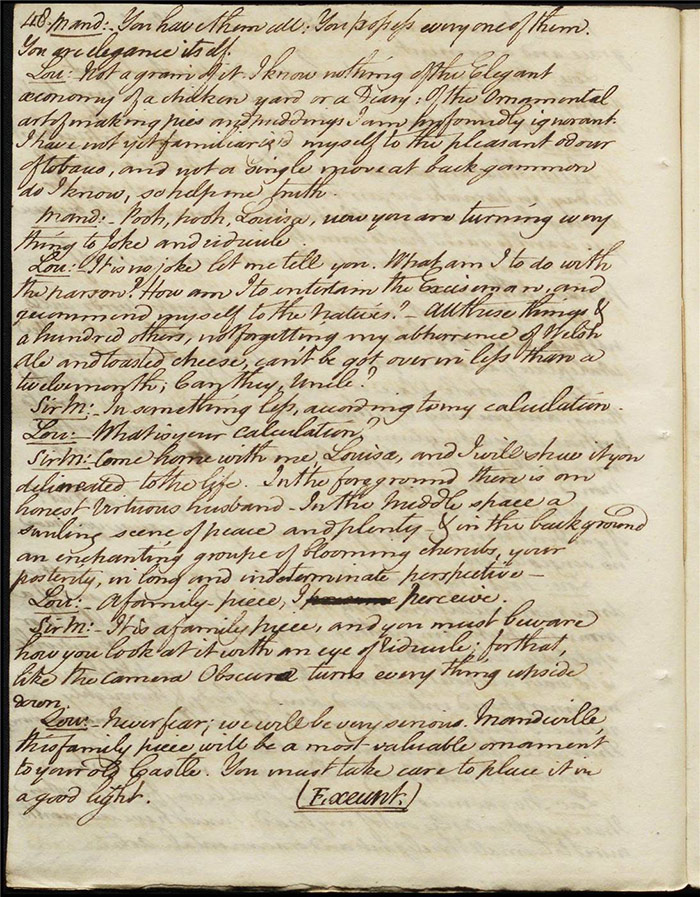

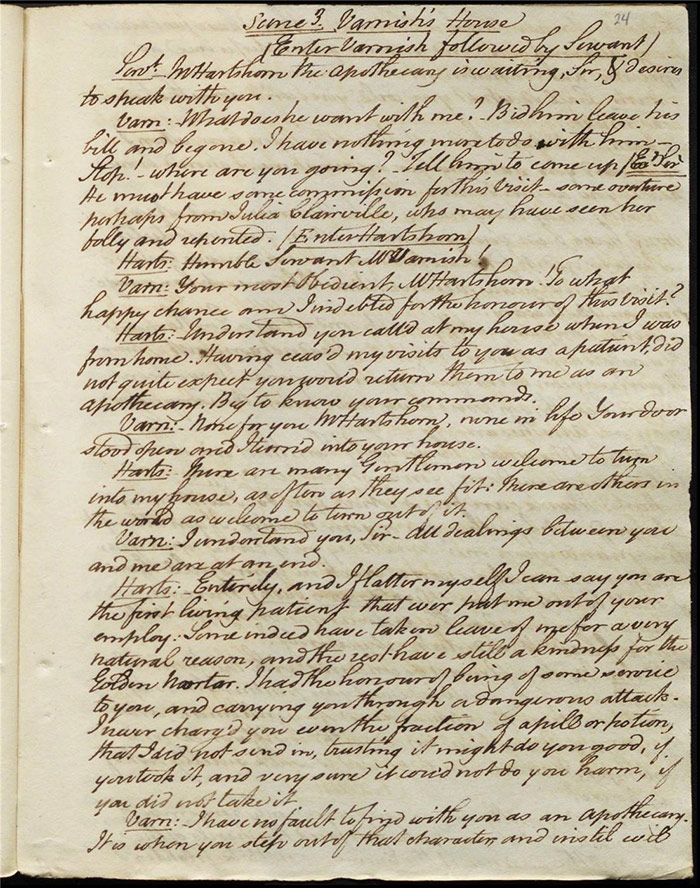

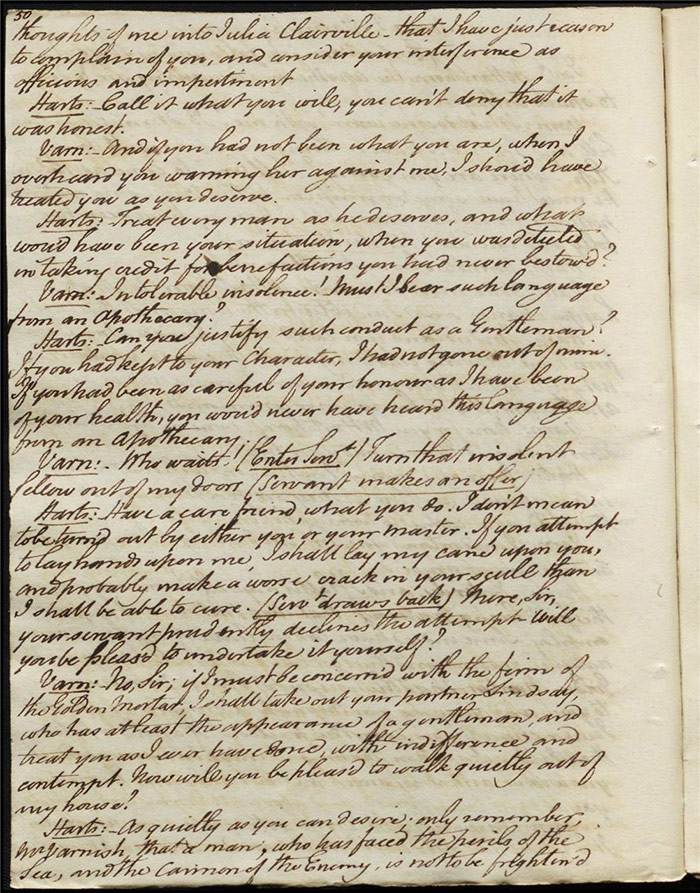

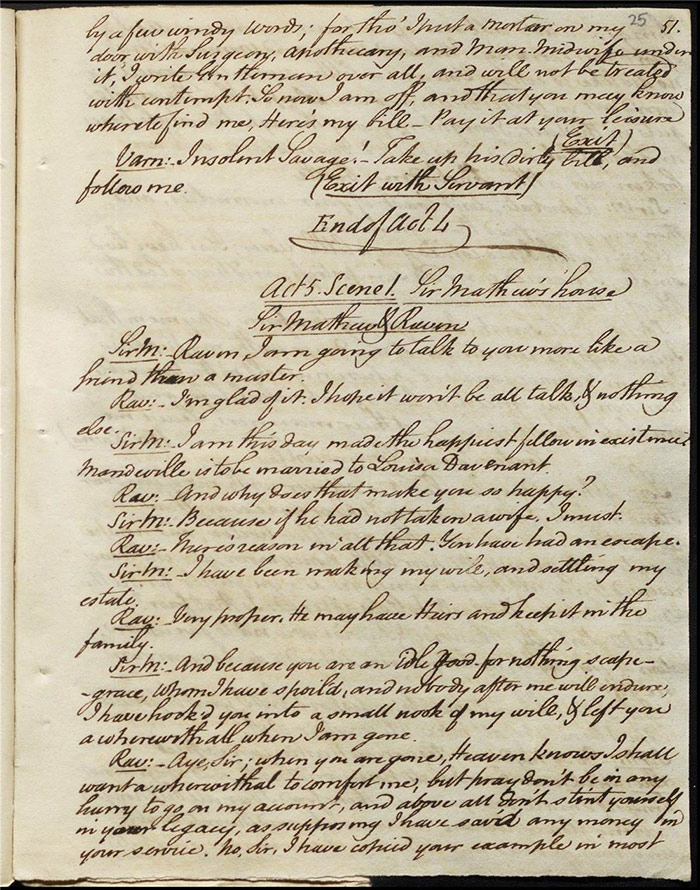

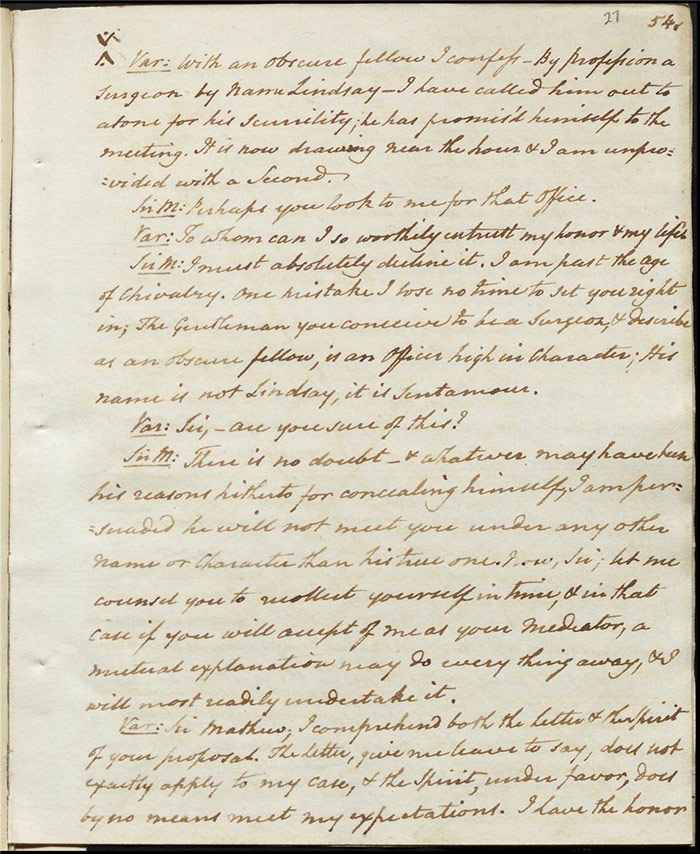

Mrs Hartshorn rouses her husband’s suspicions of Sentamour in disguise in act 4, believing him to have designs on Julia(f.19r). Hartshorn forces the issue and Sentamour admits who he is and explains he wanted to see Julia’s true character. Julia confesses to Louisa that she loves ‘Lindsay’ but feels guilty as her father wanted her to marry Sentamour (f.21r). Mandeville and Sentamour enter and they separate into pairs: Julia leaves with Sentamour while Louisa sings on love to Mandeville. After telling him that she won’t marry him as he is more a lover than a husband, she changes her mind when she hears that Varnish has accused her of turning Julia against him but insists he will have to wait twelve months so she can get used to country life. Hartshorn calls on Varnish and they argue (f.24r). Varnish is angry at Hartshorn’s warnings to Julia about him and insists he will only work with Lindsay (ie Sentamour) in future. Hartshorn leaves his bill and exits.

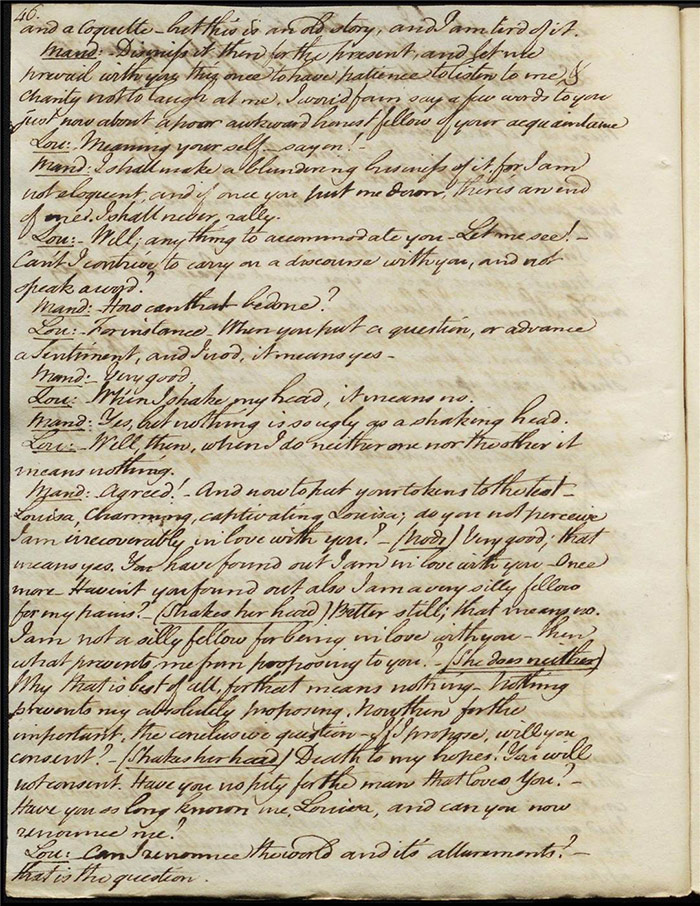

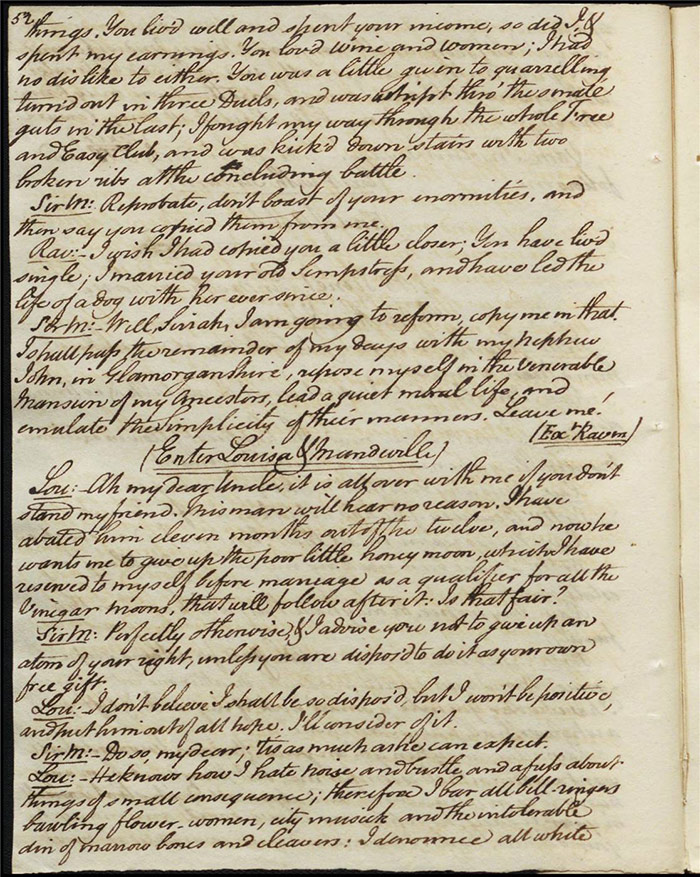

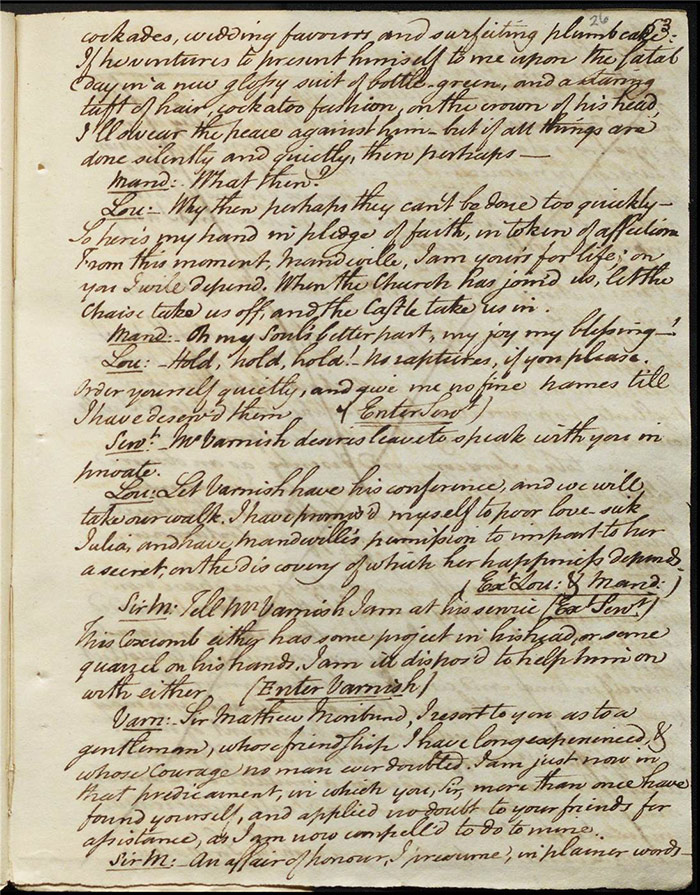

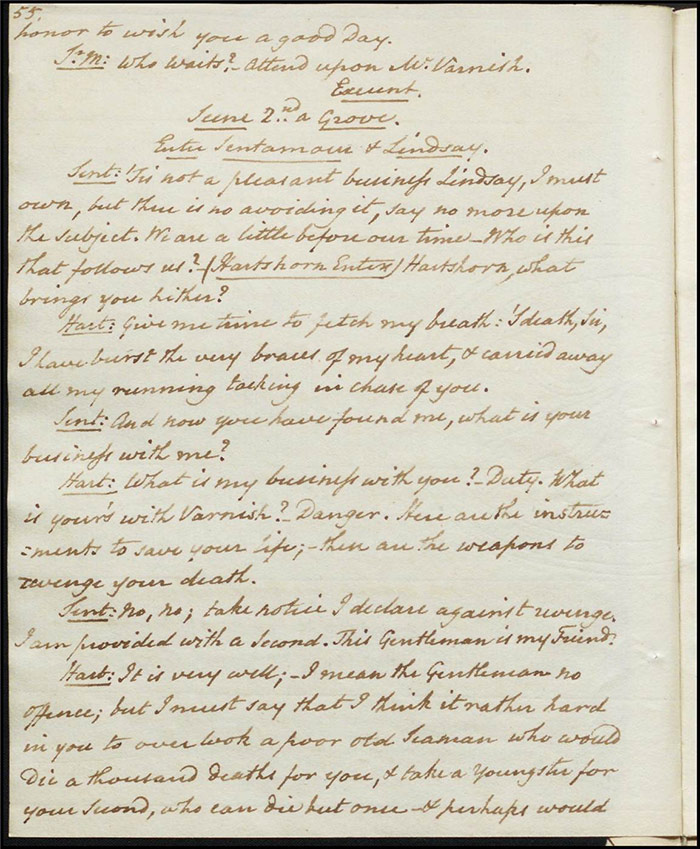

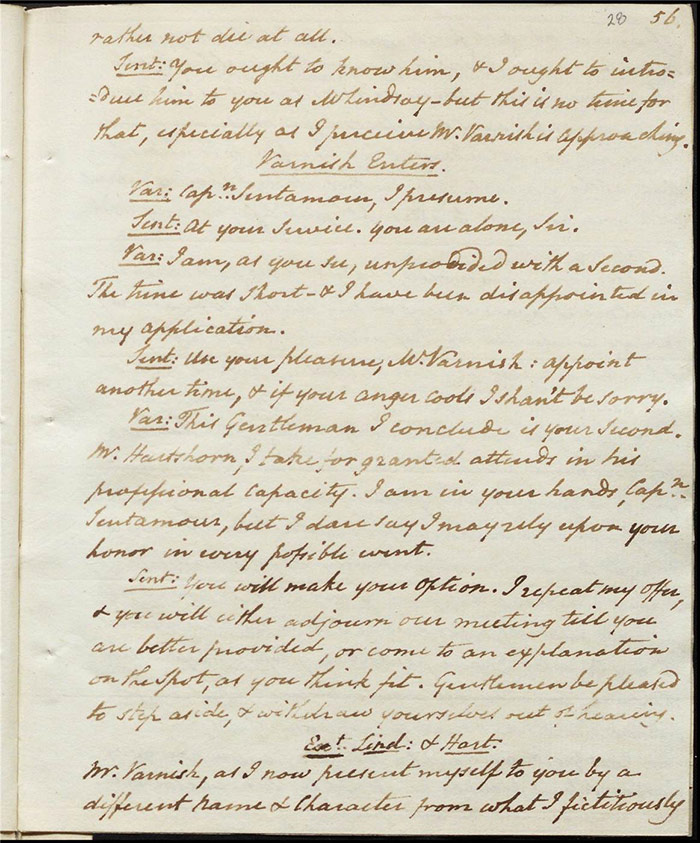

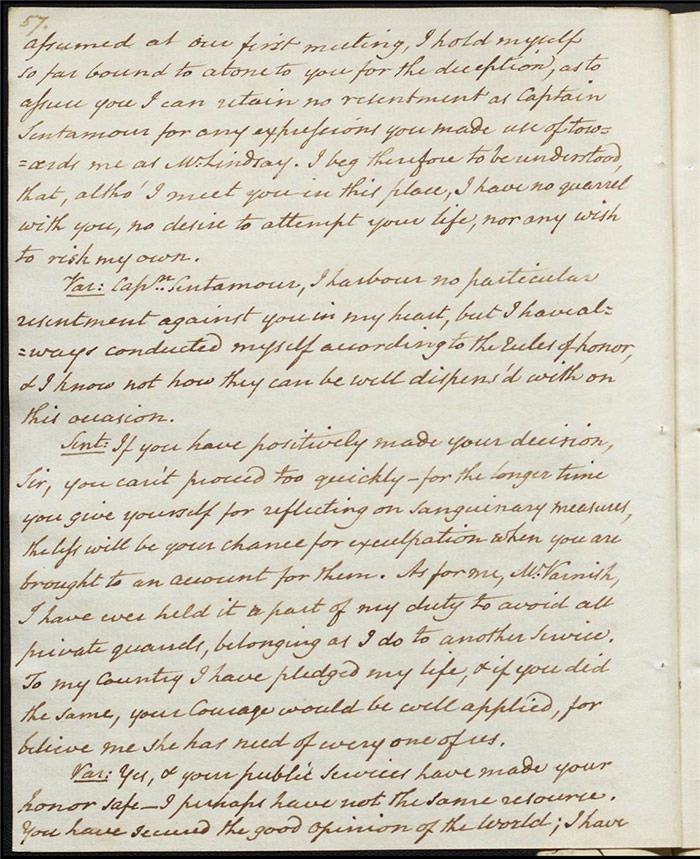

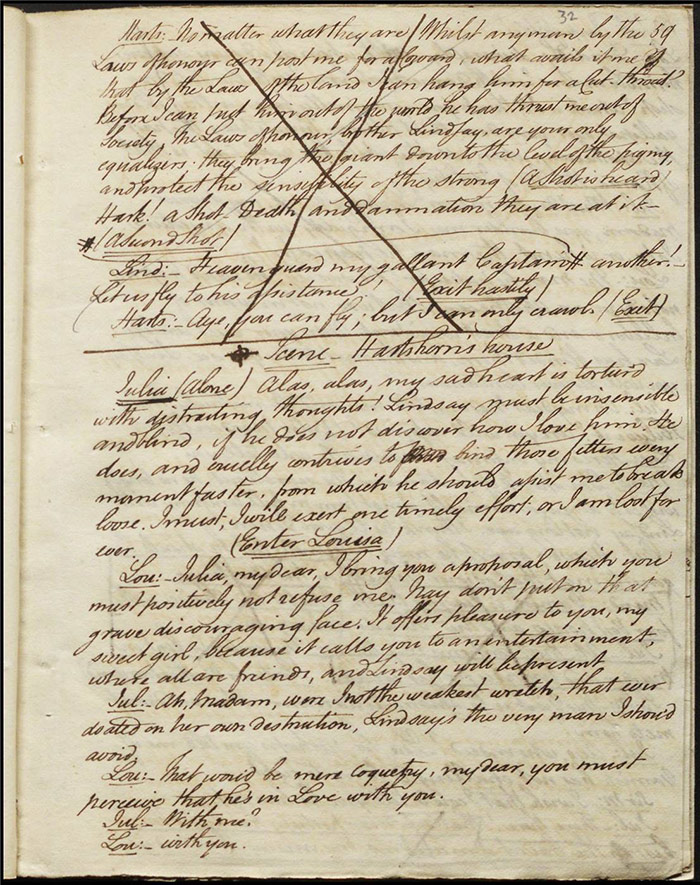

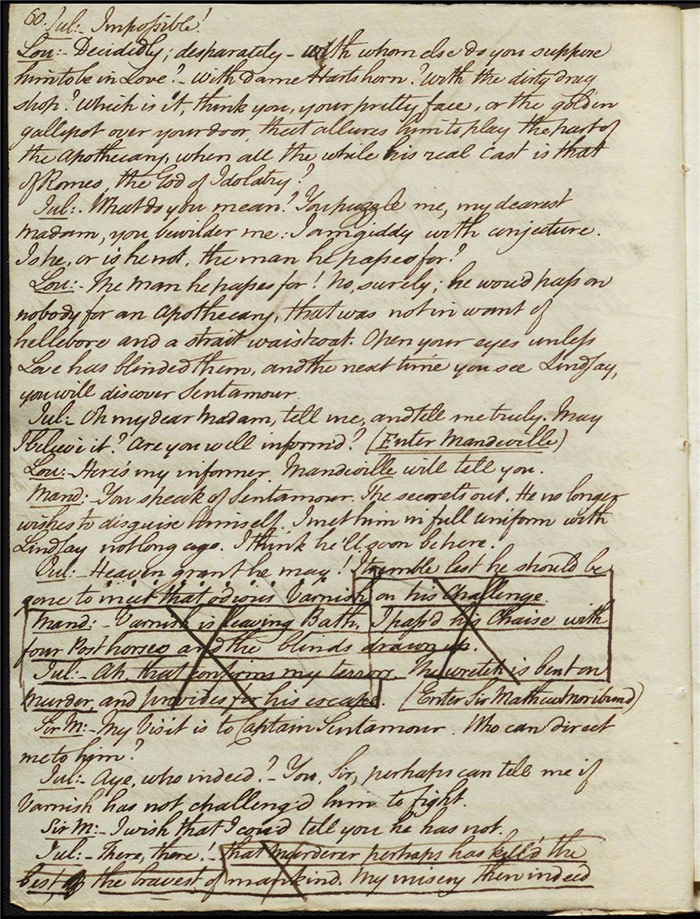

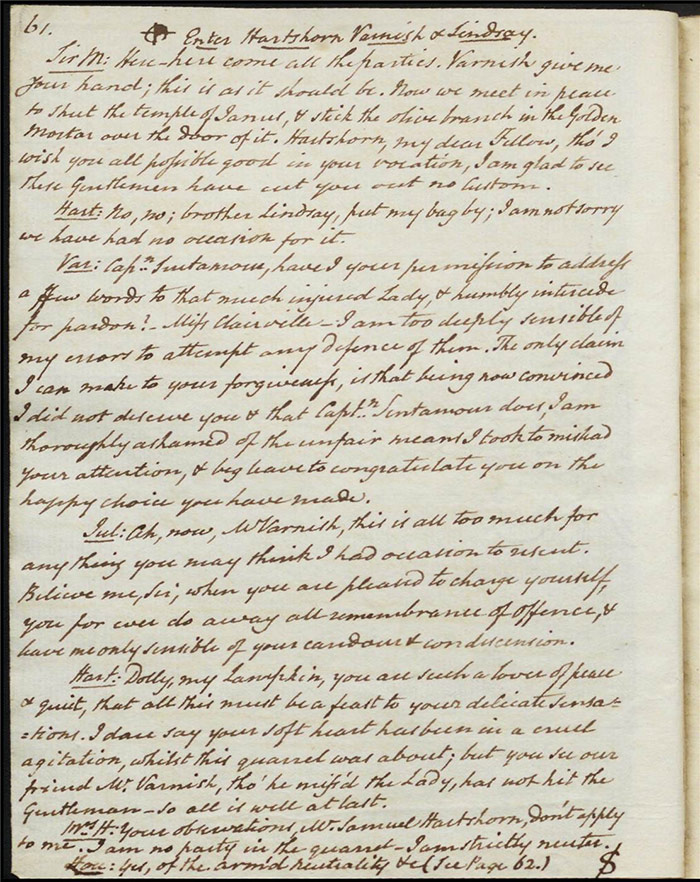

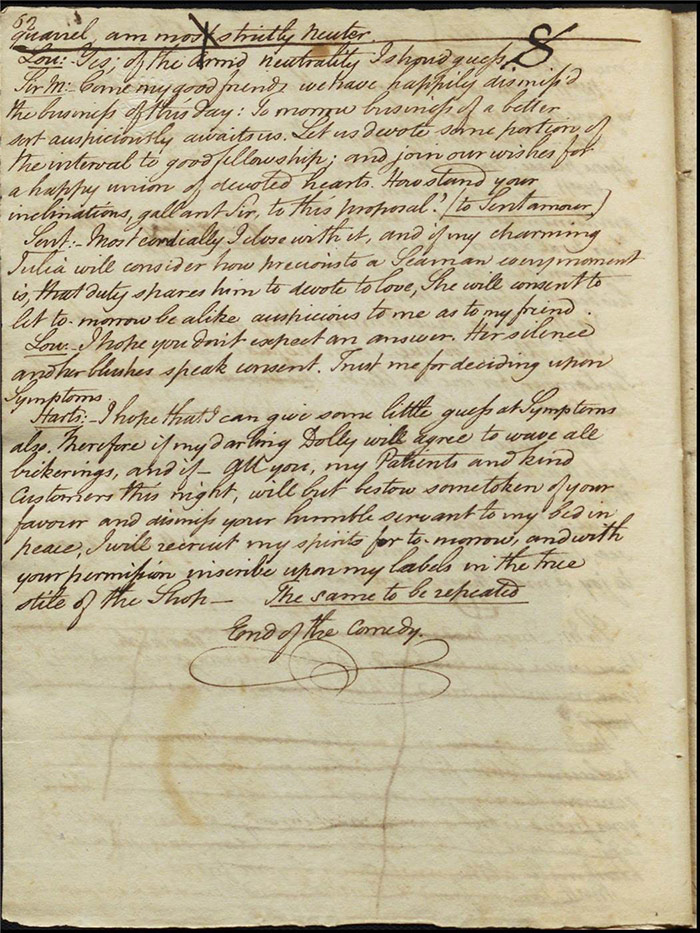

In the concluding act, Sir Matthew is delighted that Mandeville and Louisa are to be married as it saves him the trouble of producing an heir (f.25r) [The plot given here is that of the play as performed; extensive revisions to this final act were demanded by Larpent and these are documented in the ‘Commentary’ section]. Louisa tells Mandeville they can be married straight away if there is a simple ceremony without any fuss. Varnish enters and tells Sir Matthew that he needs him as a second for a duel with Lindsay. Sir Matthew explains that Lindsay is actually Sentamour. Sentamour and Lindsay await Varnish in a grove (f.27v). Hartshorn enters and offers to be his second but Sentamour explains that he already has one. Varnish arrives and, after a lengthy discussion about the demands of honour, the pair agree to abandon the duel. Varnish withdraws any claims on Julia and offers to leave for Bath. Sentamour advises him to stay in town to avoid any accusations of cowardice. Julia explains to Louisa that Lindsay is actually Sentamour and that he is in love with her (f.32r). Mandeville, Sir Matthew, Varnish and Lindsay all enter, reconciled. Sentamour enters and presents himself to Louisa.

Performance, publication and reception

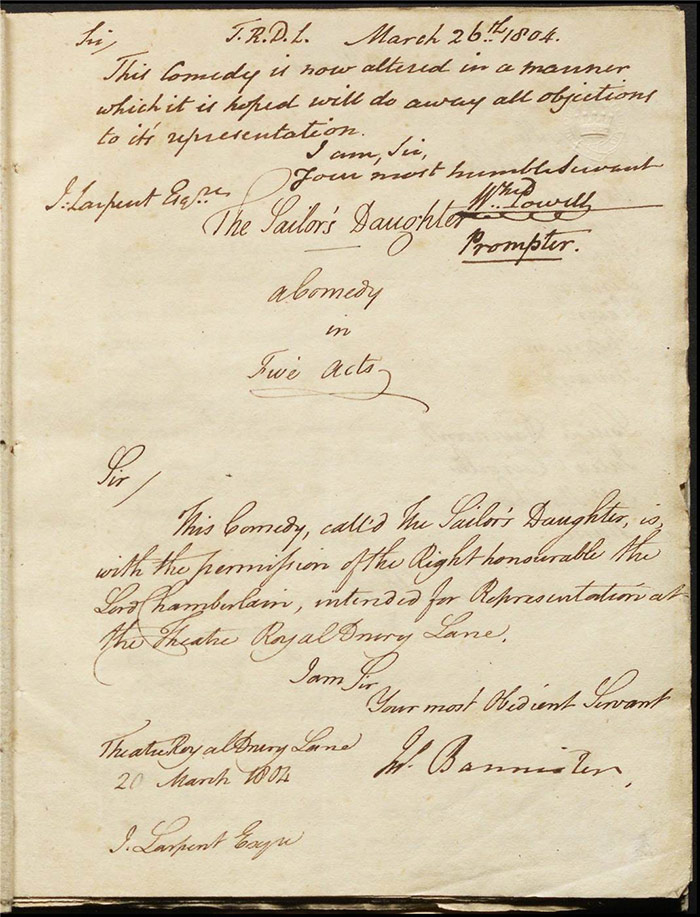

The manuscript was submitted on 20 March 1804 by John Bannister. Anna Larpent recorded reading it on 21 March win her diary but offered no comment (HM 31201, vol 5: f.200r). After Larpent’s objections were dealt with, it was resubmitted on 26 March by William Powell, the prompter, who wrote in a cover note ‘This Comedy is now altered in a manner which it is hoped will do away all objections to its’ representation’ [n.f.] The play was first performed at Drury Lane Theatre on 7 April 1804.

Lloyd’s Evening Post (6-9 April 1804) pronounced the house ‘very divided in opinion’ on a comedy which was ‘far inferior to the pieces from which the author has acquired his deserved celebrity’. The Morning Chronicle (9 April 1804) was more blunt, declaring the plot ‘both weak and improbable’. Cumberland’s mature dramatic abilities—he was recently turned 72—were explicitly called into question:

We cannot help, however, expressing some regret that he does not allow himself the ease and quiet to which he is so justly entitled from his past labours. His well meant endeavours to contribute to the public amusement at the advanced age to which he has now reached, may impair the lustre of his dramatic fame.

Despite these negative reports on the first night, Lloyd’s Evening Post (9-11 April) reported that the second performance involved ‘several judicious alterations’ and that it was subsequently received ‘without the least murmur of disapprobation’. The reviewer for The Times (9 April 1804) may have helpfully provided hints for some of those amendments: ‘we recommend to the Author to dismiss from his dialogue the miserable puns, the wretched attempts at wit and humour, the coarse allusions, and trifling quiddities, which are an insult to true taste’.

In an act of regional dissent, the authoritative voice of the Derby Mercury (12 April 1804) insisted that ‘[the comedy] bids fair to rival in attraction the most popular plays of the season. Pope, Bannister and Mrs H. Johnston, were very successful in their respective characters, and Mrs Jordan was as fascinating as ever’.

The newspaper advertisements indicate there were subsequent performances on 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, and 17 April so Cumberland had at least had 2 benefit nights for his efforts. The comedy was published by Lackington, Allen, & Co. and went to a second edition.

In his advertisement to the published version, Cumberland hoped that ‘it may find favour in the closet, whatever it may be likely to experience on the Stage’. He admitted that he had perhaps ‘not been so studious of the reigning taste as I ought to have been’. These words give us an indication as to how poorly the play was received, whatever the Derby Mercury might have thought.

Commentary

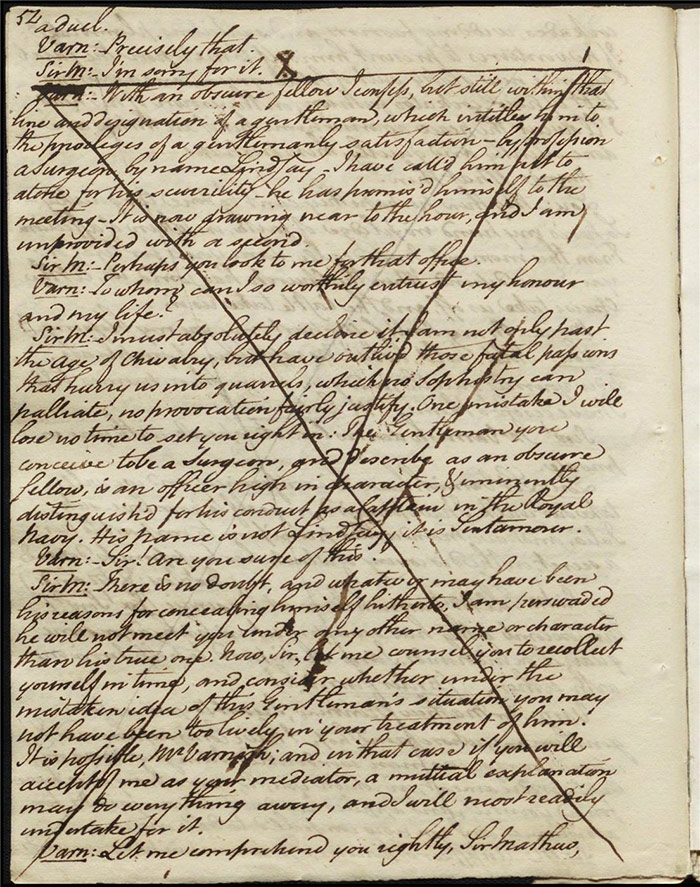

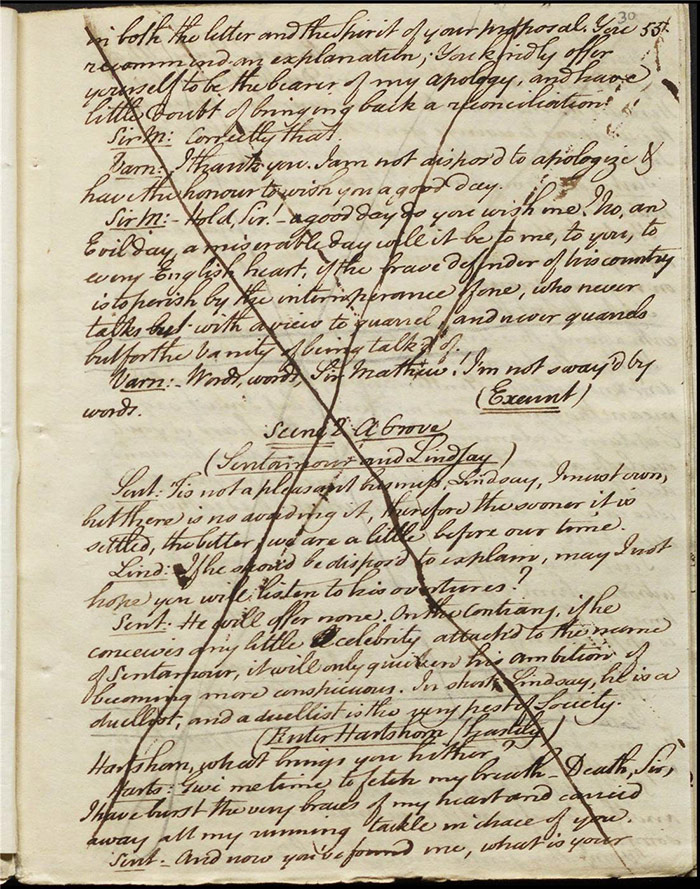

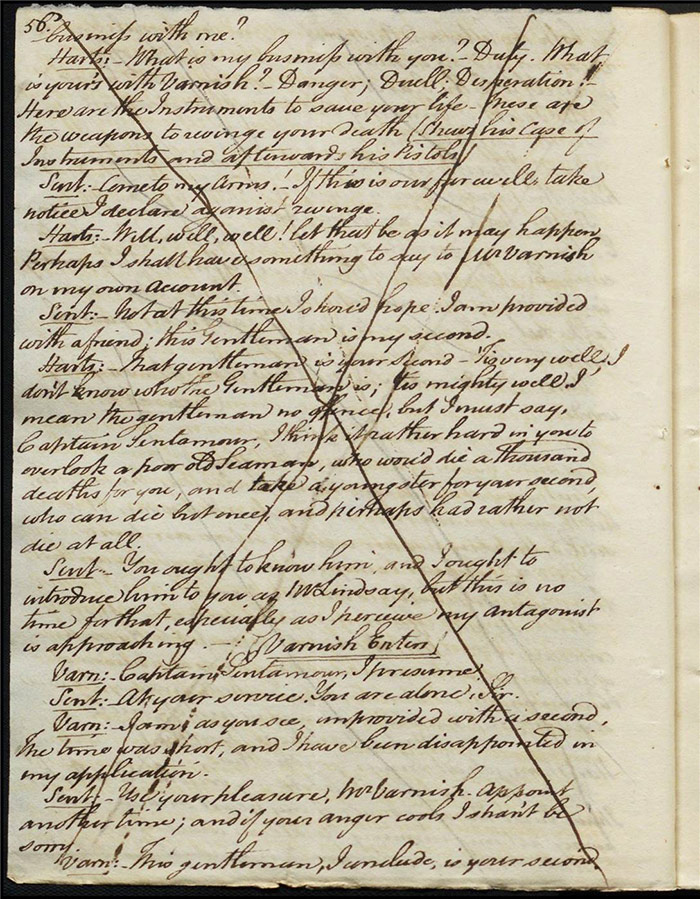

The manuscript (LA 1409) shows a number of excisions and emendations marked in pen and pencil relating to the fifth act. It is uncertain as to whom is marking the manuscript but we might tentatively suggest that Larpent used the pencil to underline some lines that he found particularly egregious. In any case, as indicated by William Powell’s cover note, it was certainly on the firm instruction of Larpent that the major excisions in pen were made even if he did not personally wield it. The nature of the changes—whole pages marked with large ‘X’s accompanied by substantive rewrites—indicate that Larpent may have simply verbally demanded a rewrite of the play’s denouement and that Powell, Cumberland, and Bannister (or some combination thereof) contrived to produce it. The published version contains no protest and indeed sticks to the amended version which suggests, at the least, Cumberland’s acquiescence to the changes.

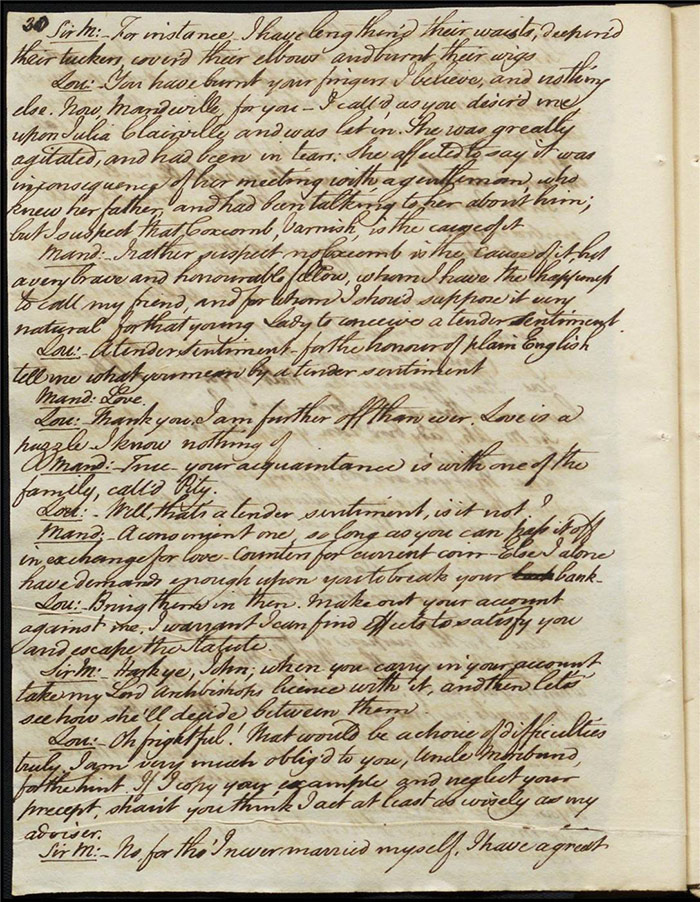

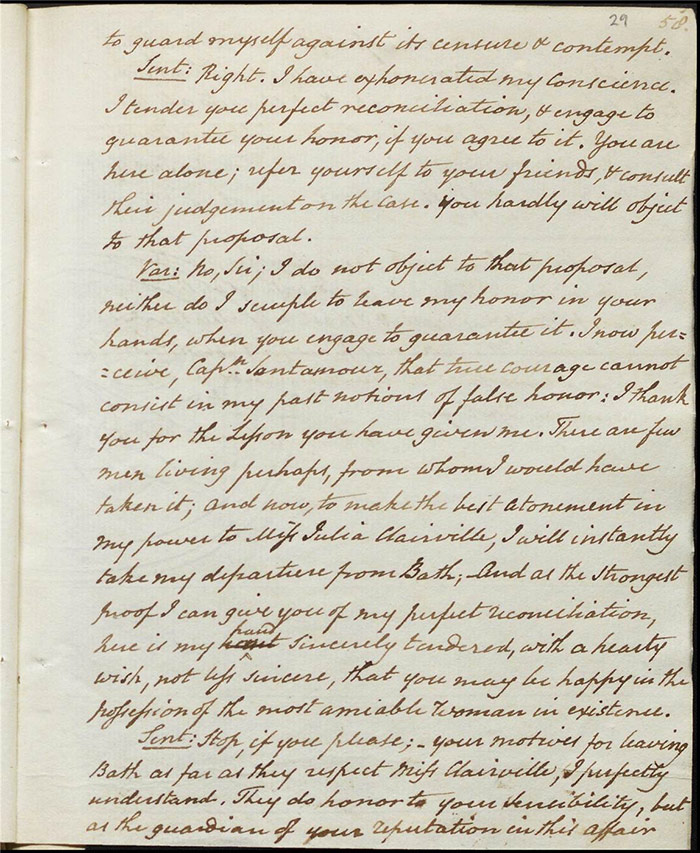

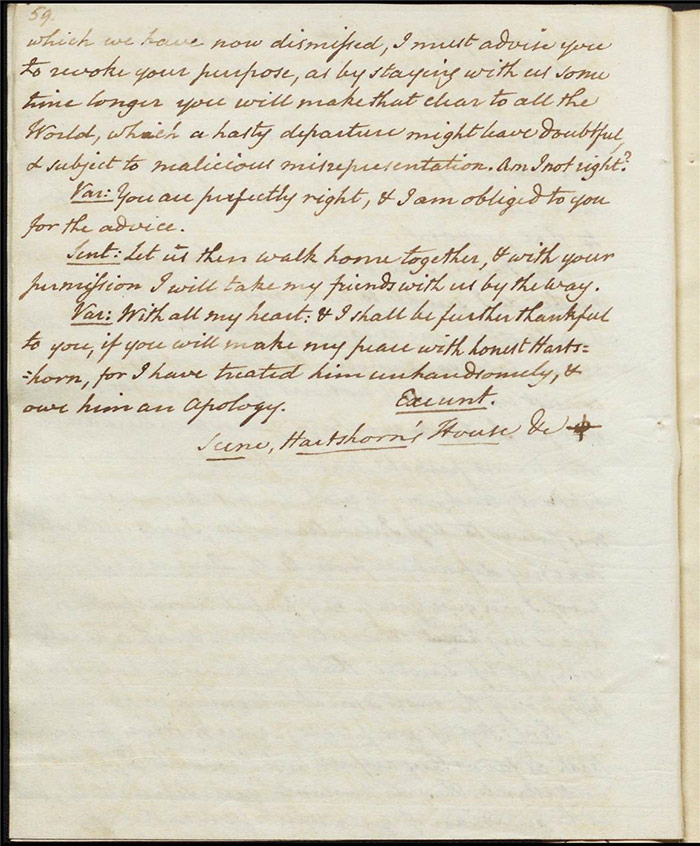

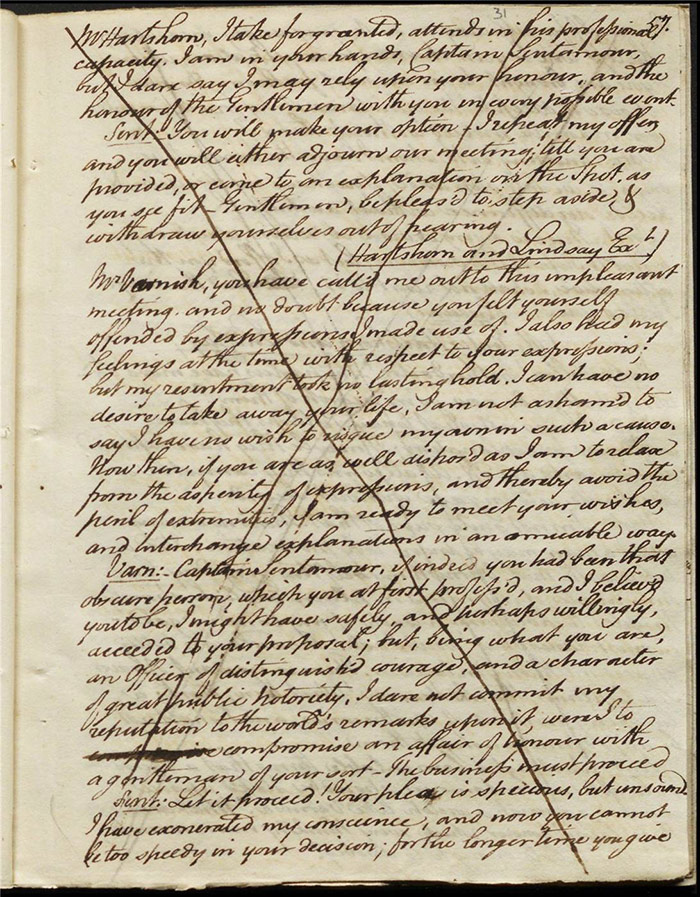

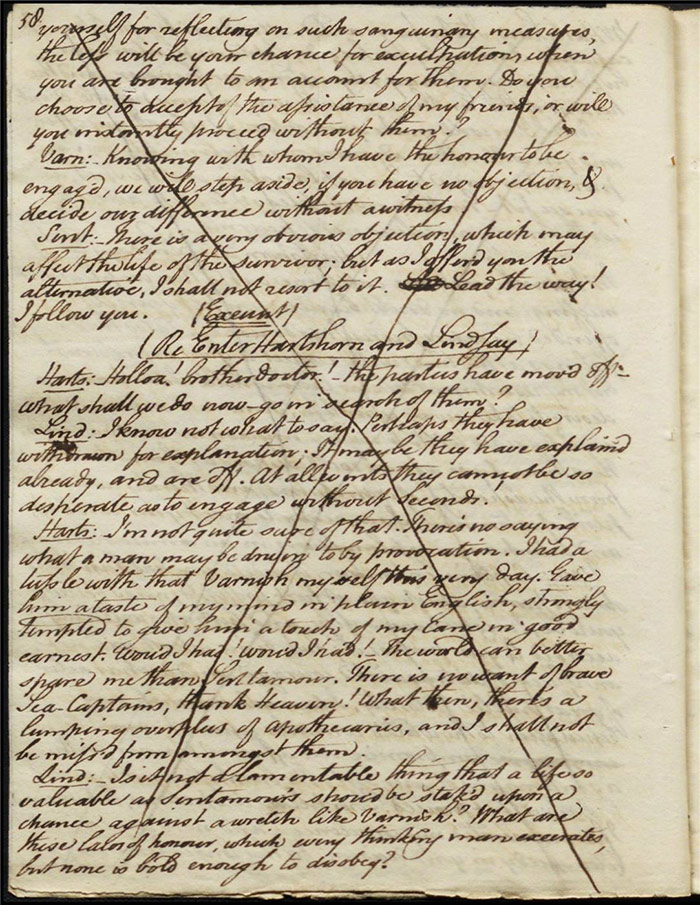

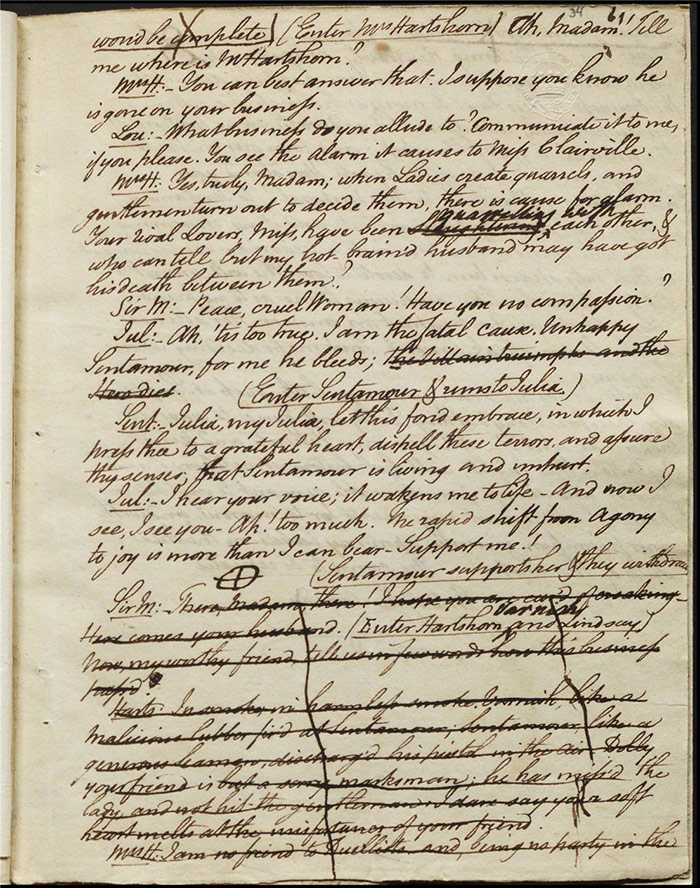

The large excisions in pen can be seen on (f.26v), (ff.30r-32v), and (ff.34rv) and the rewrites on (ff. 27r-29v) and (f.33v). All these changes are related to Larpent’s difficulty with the concluding duel and some context is required to make sense of them.

On 7 March 1804—just a fortnight before submission of the manuscript—a duel was fought between Thomas Pitt, Lord Camelford and an old friend, Thomas Best. Pitt had a colourful history of violent behavior dating back to his navy days. He was even thought to have entered France, armed, with the intention of assassinating Napoleon Bonaparte in 1801 – and perhaps again in 1802!

According to the detailed report of the duel in the Morning Chronicle (9 March 1804), Camelford had been informed by one Mrs Symons that Best had made a disparaging remark about him. Camelford confronted Best publicly at a coffee-house and Best unequivocally denied he had made any such comments. Camelford’s insults led to a duel being arranged. Best made further efforts to avoid the duel but although Camelford was ultimately convinced the charge was false, he felt obliged to persist. The Morning Chronicle article even claims that Camelford missed deliberately but without telling Best that he was going to do so. Camelford was mortally wounded but his will made it clear that Best was not to be held accountable.

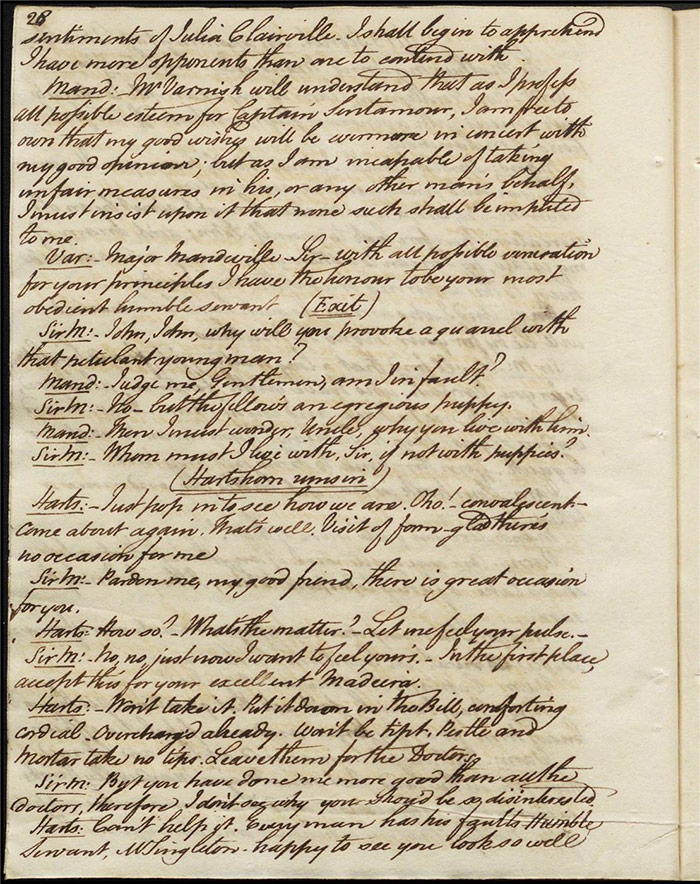

Larpent’s sensitivity around the depiction of dueling and the language used to describe it and its real-life practitioners must be understood in the context of this high-profile event. The few lines that are underlined in pencil are on (f.30r). Here Sir Matthew is attempting to make the peace between Varnish and Captain Sentamour and he addresses the former:

Hold Sir! – a good day do you wish me? No, an Evil day, a miserable day will it be to me, to you, to every English heart, if the brave defender of his country is to perish by the intemperance of one, who never talks but with a view to quarrel, and never quarrels but for the vanity of being talk’d of.

Given the recently deceased Camelford’s highly public record of affray, Cumberland was undoubtedly referring to him and Larpent picked up on it. Some lines later, Sentamour’s unequivocal condemnation of Varnish’s ego must have read like an ad hominem attack on the dead Camelford:

If [Varnish] conceives any little celebrity attach’d to the name of Sentamour, it will only quicken his ambition of becoming more conspicuous. In short, Lindsay he is a duellist, and a duellist is the very pest of Society.

The next folio (f.30v) also reveals some pencil marks scored through dialogue relating to the duel that may indicate a growing general disapprobation of the theme on Larpent’s part. Certainly, the deletion of the entire folio and those following make clear that Cumberland’s intended critique of dueling culture misfired. The original plot has the duel proceeding with both Varnish and Sentamour essentially admitting that they are obliged to do so—despite their rational misgivings—due to rigid laws of honour. A passage on (f.34r) which is marked for particular attention (by Larpent?) with a symbol and every line scored out individually had Hartshorn tell the ensemble how the duel unfolded. The possibility of the audience understanding this as what was supposed to have transpired between Camelford and Best was clearly very troubling for Larpent:

In smoke in harmless smoke. Varnish, like a malicious lubber fir’d at Sentamour; Sentamour, like a generous Seaman, discharg’d his pistol in the air. Dolly, [Mrs Hartshorn] your friend is but a sorry marksman; he has miss’d the lady, and not hit the gentleman. I dare say your soft heart melts at the misfortunes of your friend.

As a brief coda, we might observe that there are some parallels between the reaction of the audience to the conclusion of the play with that of the audience of William Godwin’s Antonio (1800). In Charles Lamb’s memorable telling in ‘The Old Actors’ (1822) of that tragedy’s first and only performance he observed the audience’s moral dilemma when the prospect of a duel was suddenly withdrawn:

The audience here were fairly caught – their courage was up, and on the alert – a few blows, ding dong, as R[eynold]s the dramatist afterwards expressed it to me, might have done the business – when their most exquisite moral sense was suddenly called into assist in the mortifying negation of their own pleasure. They could not applaud, for disappointment; they would not condemn, for morality’s sake. (329-30)

Godwin’s characters’ philosophical moralizing was dramatically misjudged and the audience were sorely disappointed. The mixed reaction to the conclusion of Cumberland’s play reported in the press reviews cited above suggest the same was true for him. It would appear that—perhaps particularly at a time of war—English audiences wanted their naval officers to be more aggressive and less philosophically decorous.

Further reading

Morning Chronicle, 9 and 13 March 1804.

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 106.

Richard Cumberland, The Sailor’s Daughter (London: Lackington & Allen, 1806).

[available on archive.org]

______ Memoirs of Richard Cumberland. Written by himself. Containing an account of his life and writings, interspersed with anecdotes and characters of several of the most distinguished persons of his time, with whom he has had intercourse and connexion. (London: Lackington, Allen, & Co., 1806).

[available on HathiTrust. Archive.org]

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, HM 31201 vol 1, f.93v

Arthur Sherbo, ‘Cumberland, Richard (1721-1811), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Pres, 2004; online edn Oct 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6888, accessed 25 October 2018]

Nikolai Tolstoy, The half-mad lord: Thomas Pitt, 2nd Baron Camelford (London: Jonathan Cape, 1978).