Quarter Day (1798) LA 1192/1212

Author

John O’Keeffe (1747-1833)

Keeffe was born in Dublin and began his theatrical career as an actor at Smock Alley around 1764. Henry Mossop staged his afterpiece The She Gallant in 1767 and O’Keeffe worked as an actor around Ireland for ten years, occasionally writing comedies, notably Tony Lumpkin in Town (1774), a sequel to Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer. He sent a revised version of Tony Lumpkin in Town to George Colman, the Haymarket manager, and it received six performances in 1778. O’Keeffe continued to send his work to the receptive Colman and this, along with the breakup of his marriage, led to his permanent move to London in 1781.

His afterpiece The Agreeable Surprise (1781) was a major success and, despite the loss of his sight, O’Keeffe continued to produce a series of major successes through the 1780s and 1790s, mostly at Thomas Harris’s Covent Garden. Chief among these were The Poor Soldier (1783) and Wild Oats (1791): the former became a favourite in America and the latter continues to be revived today. He also demonstrated an uncanny knack for rewriting initial failures into later successes. Adelaide O’Keeffe, later a writer herself, acted as his amanuensis from 1788.

He also had some brushes with the Examiner of Plays in addition to Quarter Day. He was refused a licence for Le Grenadier (1790), a play which depicted the French Revolution as being sparked by a corn monopoly and state oppression. His play Jenny’s Whim (1794) was also refused a licence for its mocking representation of the Emperor of Morocco, an indication of just how sensitive the authorities were to any satire of monarchical figures in the 1790s.

His writing career petered out by 1798 and he published his 4-volume Dramatic Works in 1798 under the patronage of the Prince of Wales in the hope of financial security. Thomas Harris agreed to pay him an annuity for some of his copyrights and unpublished plays in 1803 and later he received pensions from the Treasury and from the Crown. He dictated his Recollections, an important source for theatre historians, to Adelaide and they were published in (1826). She subsequently published O’Keeffe’s Legacy to his Daughter (1834), a memoir of her father along with a volume of his poems.

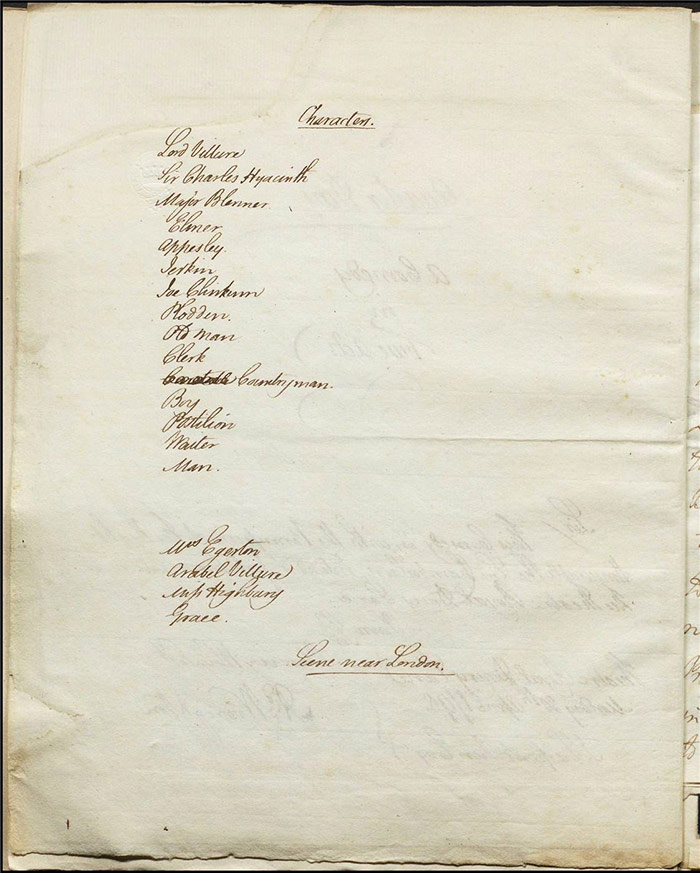

Plot

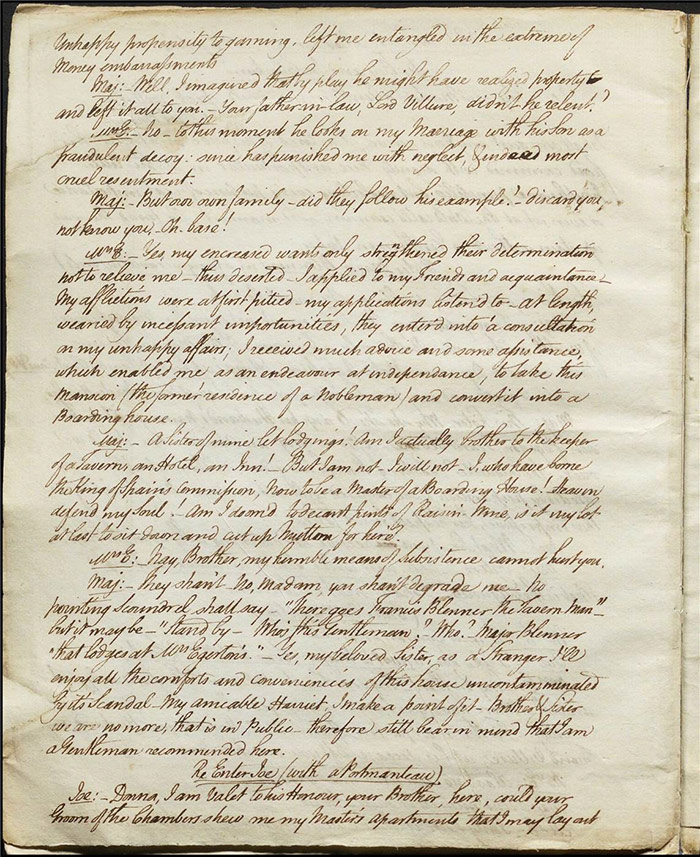

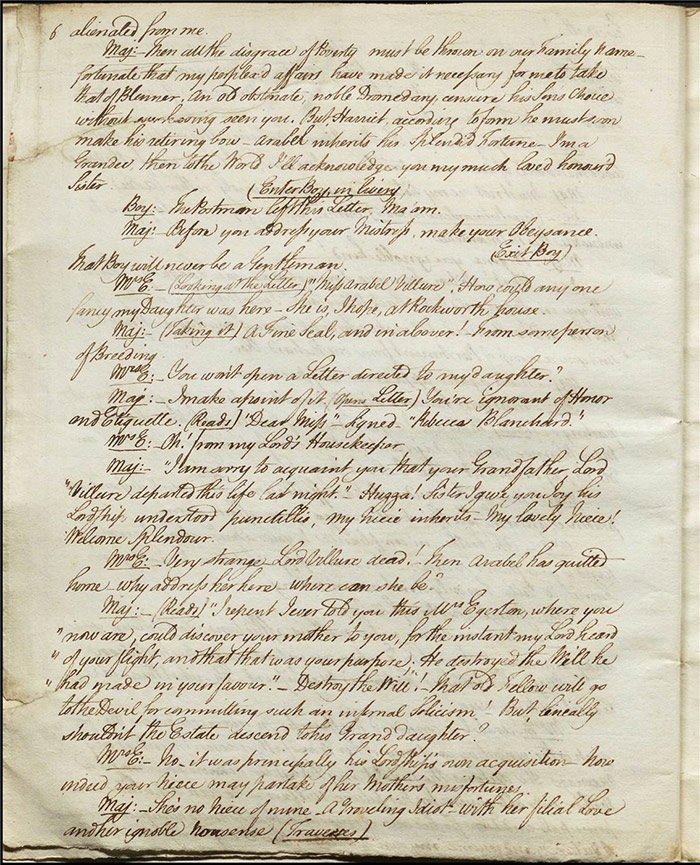

When the play opens, Major Blenner has returned from Spain after an absence of some years and calls on his sister, Mrs Egerton, the widow of Villure. She has been left in poverty by her husband’s gambling and her father-in-law’s neglect. She is now, to her brother’s horror, running a boarding house to make ends meet. Blenner resolves to stay there anonymously so that he won’t be tainted by association with her although he defends her against the approaches of Joe, his servant. Joe decides to part company from him and seek his wife. Mrs Egerton tells her brother that her daughter, Arrabel, is under the care of Lord Villure; a key condition of Villure’s was that she revert to her maiden name.

A letter arrives for Arrabel which Blenner opens. Initially delighted to hear of Lord Villure’s death, he is subsequently enraged to discover that she has been disinherited on account of her leaving to find her mother. He insists that their cousin Grace, helping out Mrs Egerton in the home, collude with them to pretend they don’t know who Arrabel is when she arrives.

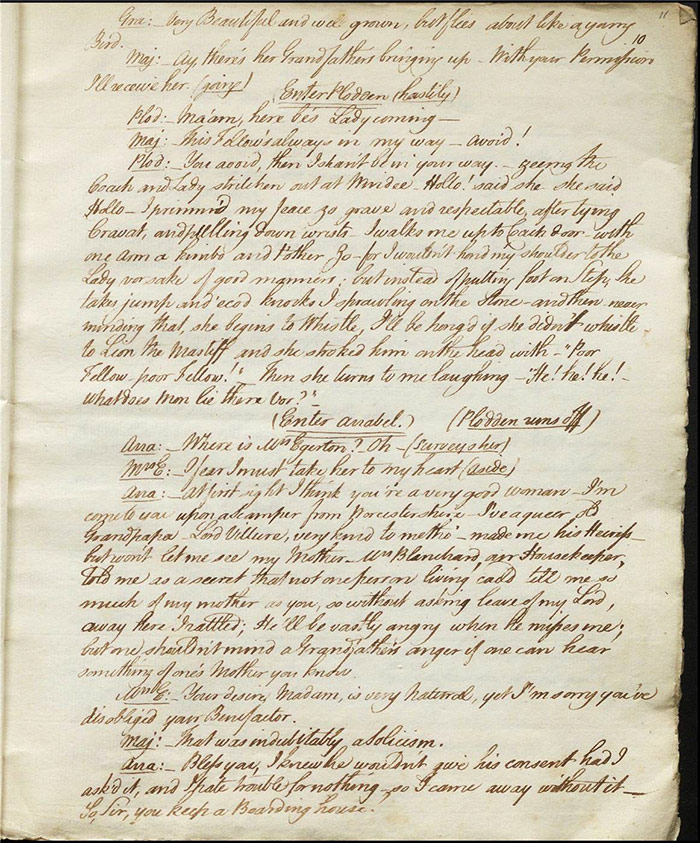

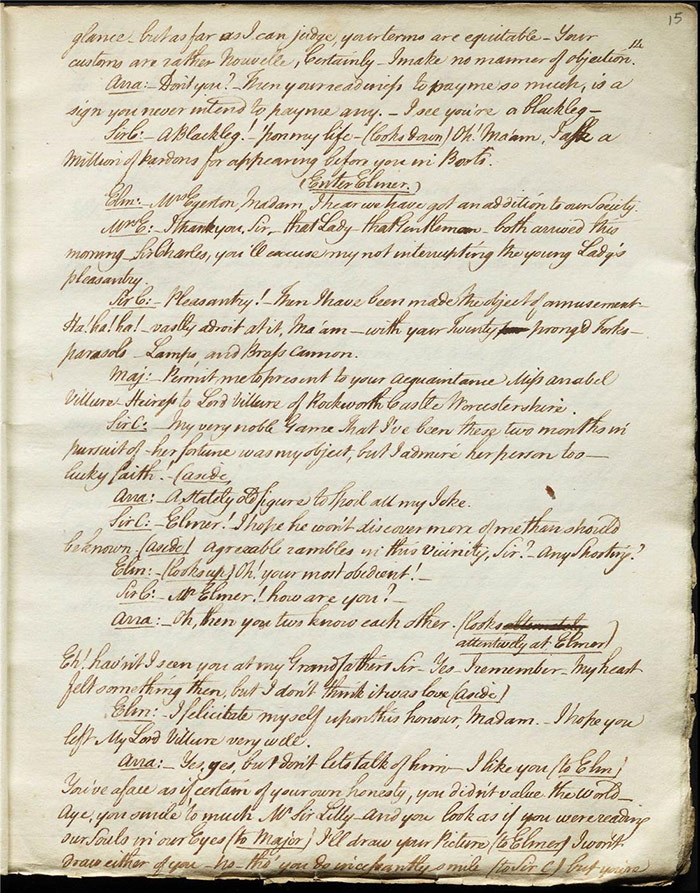

The bell rings and Plodden, a discontented servant who claims that his family was dispossessed by an ancestral General Villure, admits Arrabel. She is a feisty and confident young woman and demands to see her mother but to no avail. She then decides to pretend to be the lady of the house when Sir Charles Hyacinth arrives, looking for the rich heiress. After some mockery, the joke is revealed by Elmer, another lodger whose servant Jerkin reveals to us that he has gambled away all of Elmer’s rent money for Mrs Egerton.

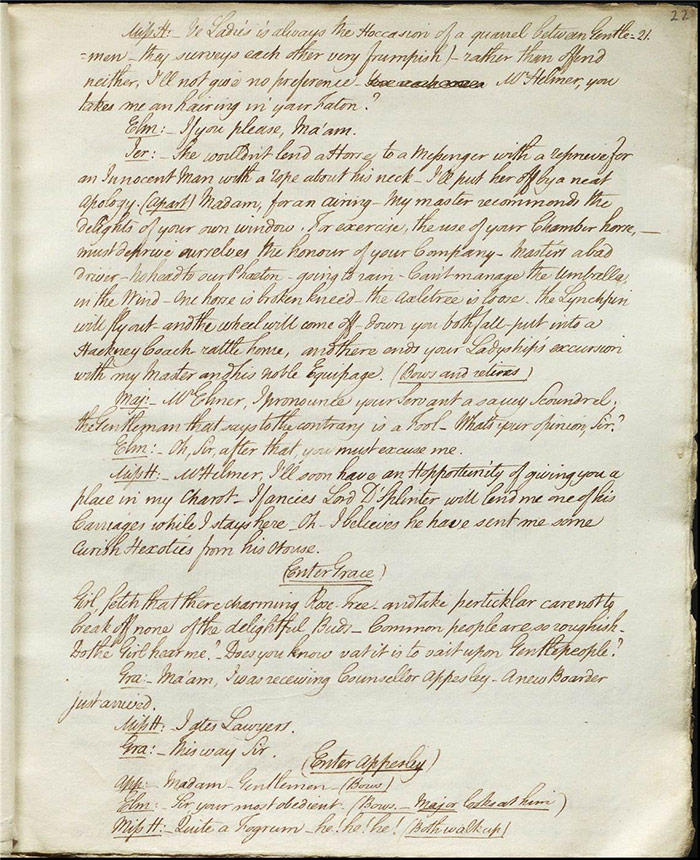

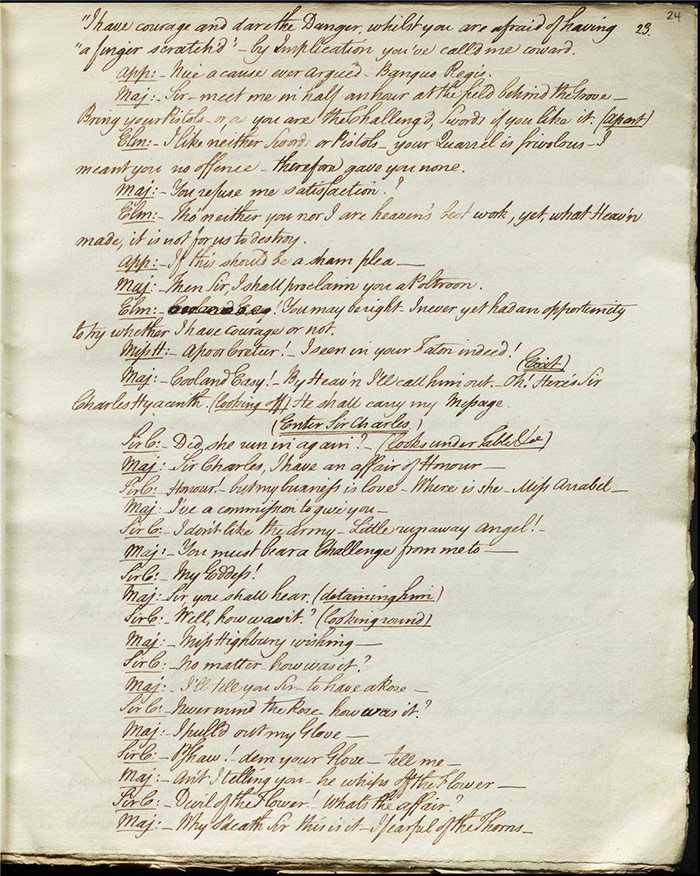

Sir Charles attempts to recruit Elmer to his nefarious plans to marry Arrabel for her fortune in act 2 (f.18r). Elmer warns Arrabel and instructs her to eavesdrop on their conversation. But Sir Charles, on returning to the room, is wise to Elmer’s plan and denies any base aspirations for Arrabel. She, enraged, then castigates Elmer for his supposed deception. Elmer manages to avoid a phaeton ride with the irritating Miss Highbury but then is frivolously challenged to a duel by the Major after an alleged insult. Elmer declines the challenge due to its silliness. The lawyer Appesley has arrived and Plodden announces a visitor for him. Joe Clinkum, servant to Elmer, is pleased to see his old friend Jerkin but less pleased to learn of Miss Highbury – his wife.

Lord Villure enters an inn (f.27r). He reveals to Appesley that he faked his death in order to punish Arrabel but has now come to atone for his treatment of Mrs Egerton. Villure has purchased her house and asks Appesley to monitor Arrabel’s behaviour. He is pleased to hear that Elmer and her may have a mutual attraction.

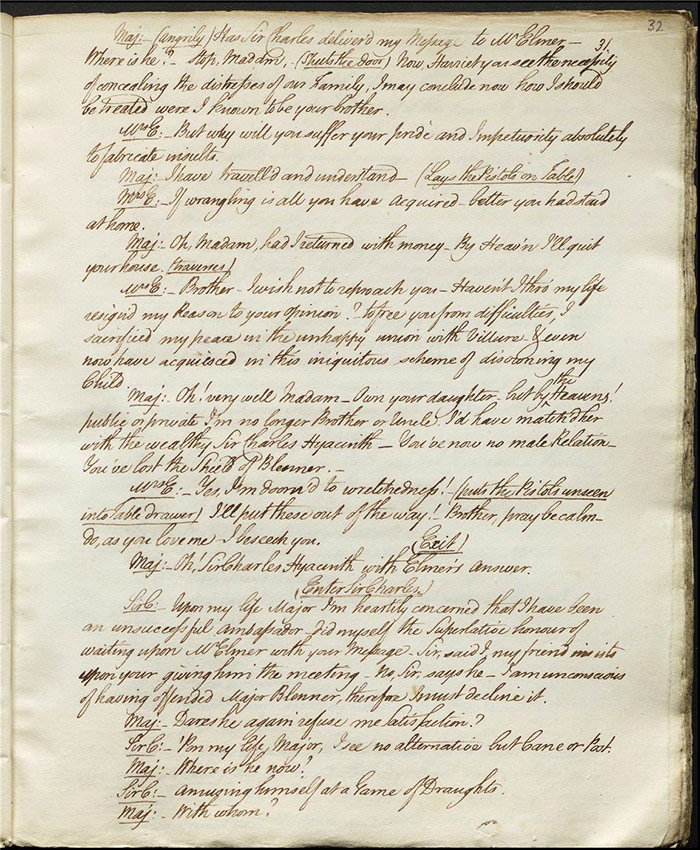

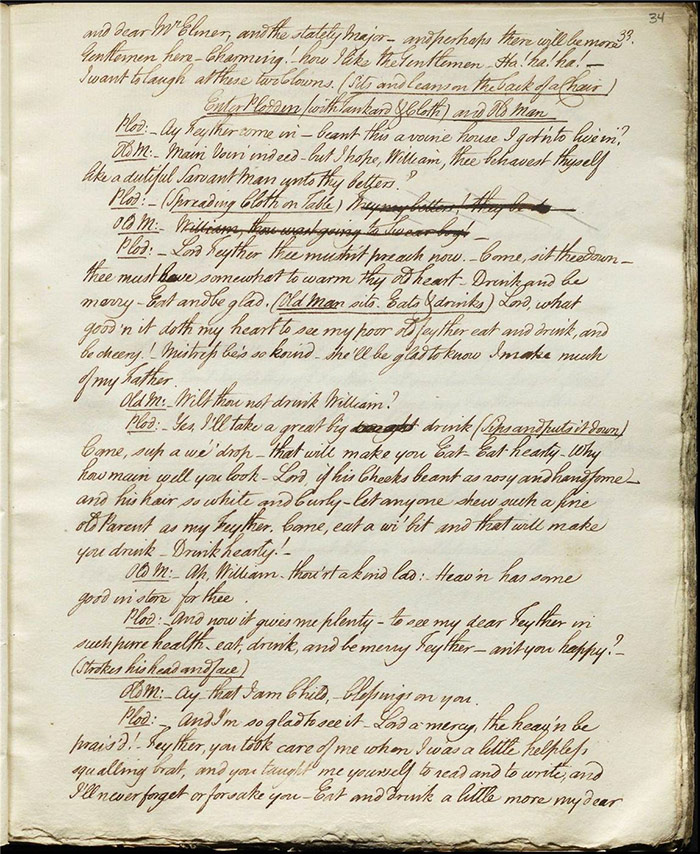

Mrs Egerton reveals her anxieties about her daughter and the impending rent due on quarter day to Grace (f.29r). Grace then tries to suggest delicately to Miss Highbury that she lend Mrs Egerton some money but the subtlety eludes her. Major Blenner chastises his sister for wanting to reveal herself to her daughter and is also angry when Sir Charles tells him that Elmer continues to refuse him satisfaction. Arrabel laughingly dismisses Sir Charles before witnessing Plodden’s kind treatment of his father, prompting her own regret for her mother.

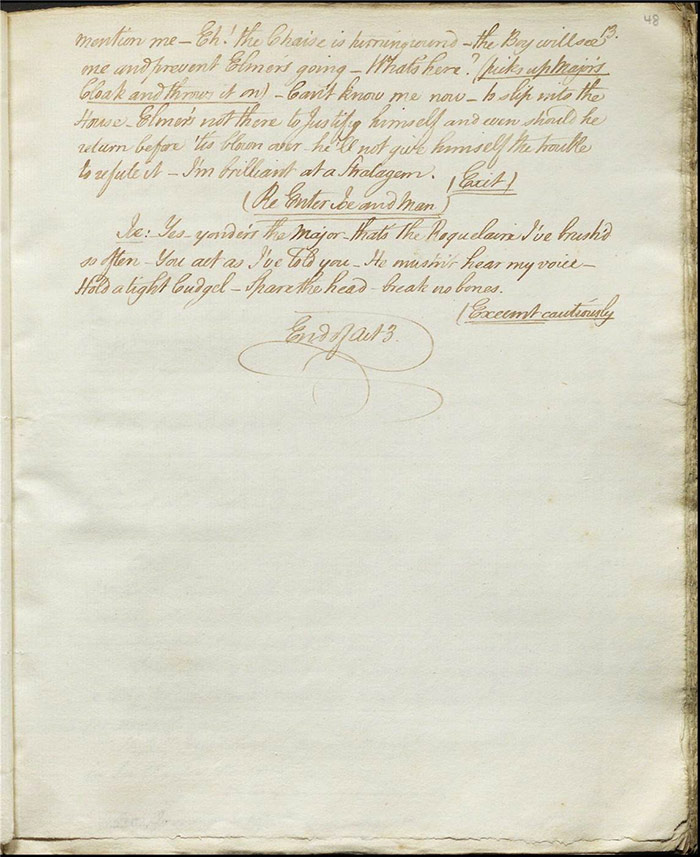

Act 3 sees Sir Charles challenges Elmer to a game of cards but he mistakenly lays down one of his flash advertisements (which would reveal his true character) as the bet (f.36r). Arrabel, Blenner and Miss Highbury enter, followed by a crying Plodden, distraught at the loss of his place as parish clerk. Arrabel, mindful of his recent demonstration of filial love, starts a collection to make up the shortfall in his income. Elmer is the only contributor but he hands over the advertisement, thinking it a banknote, thus lowering the company’s estimation of his character. He exits, thinking it is Jerkin’s fault.

Plodden is asked by Grace and Arrabel to give his small room to Jerkin and to move to a tower room (she also places some gold in his boot there for him). Elmer rebukes Jerkin over the banknote and then apologises for being in error. Jerkin is relieved as he thought he had been discovered for gambling away the rent money. Appesley is asking Arrabel about her plans for her inheritance when Jerkin enters and signals that she is wanted outside. He then distracts Appesley with a convoluted comic tale as she slips off. Sir Charles—in order to clear the field for his pursuit of Arrabel—encourages Joe Clinkum to beat up Blenner, telling him that he has designs on Miss Highbury, Clinkum’s wife.

Grace calls upon Plodden in his tower room to get him to come to dinner (f.43r). He pushes her out and then discovers the gold Arrabel has placed for him to his delight. Mrs Egerton comes to get him as well but he pretends to be asleep.

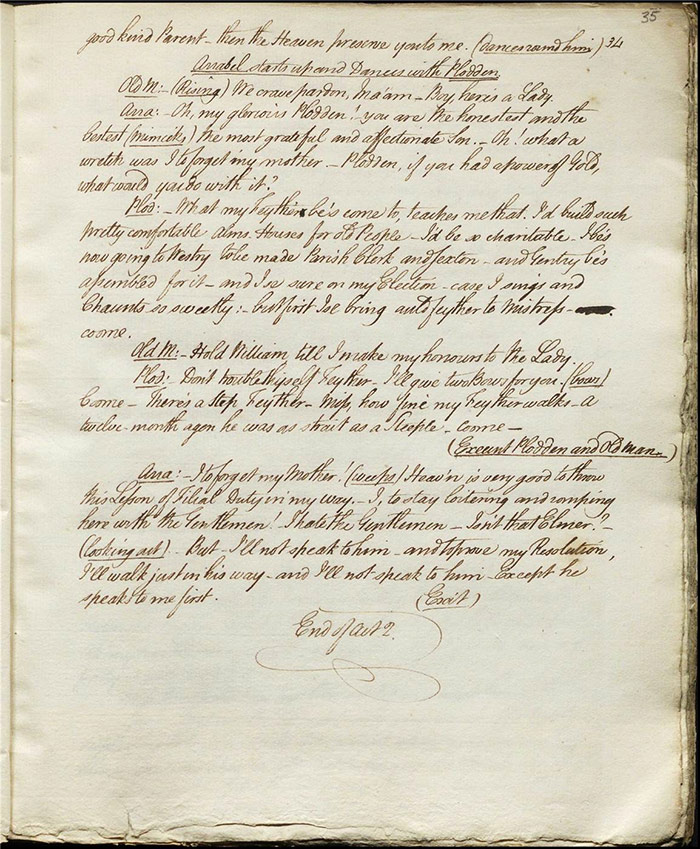

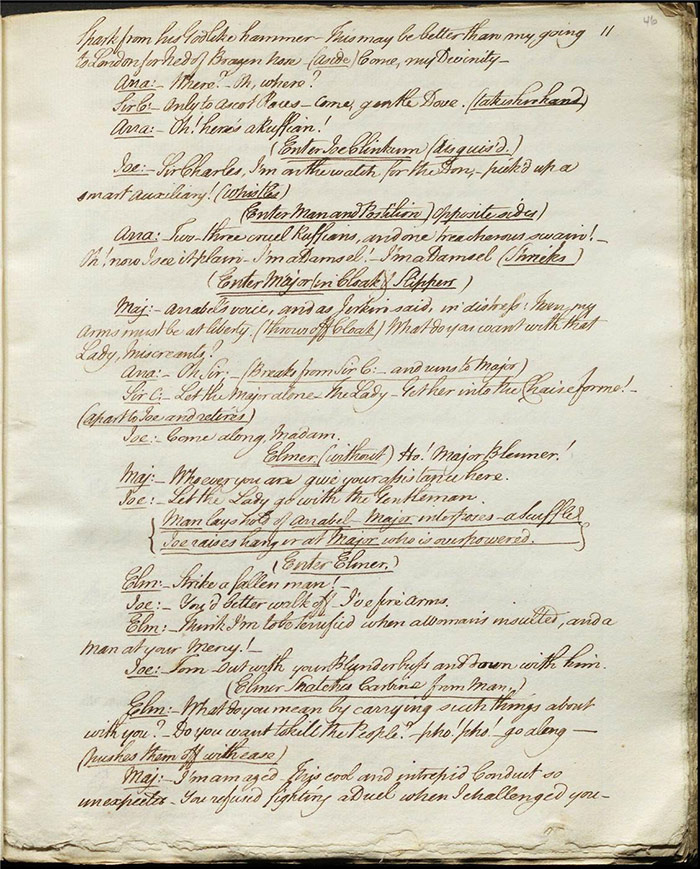

Arrabel arrives at a grove where Jerkin tells her that Sir Charles plots to run away with her; he asks for £50 to escort her safely back to Mrs Egerton’s (f.44r). Sir Charles arrives and Jerkin runs off. Arrabel, believing herself to be in danger, responds in shrill terror; Sir Charles reads this as an affectation inviting him to carry her off. Joe Clinkum and a postilion arrive, as does Blenner and Elmer. Elmer saves the day but Arrabel believes him to have orchestrated what she mistakenly believes to be an attempted kidnapping. Elmer decides to take the coach to town to meet his banker and get to the bottom of the banknote issue. Sir Charles, throws on Blenner’s cloak, which ensures that Clinkum mistakes his identity and follows him to assault him.

Plodden is deeply troubled by his newfound wealth in act 4 (f.49r). Sir Charles receives a number of visitors as he has put about the story that he fell from his horse to explain his bruises. He is incensed when Clinkum arrives looking for money but is forced to pay up as Clinkum threatens to reveal all. Sir Charles gives him the banknote he got from Elmer and Clinkum sends it to town to be changed.

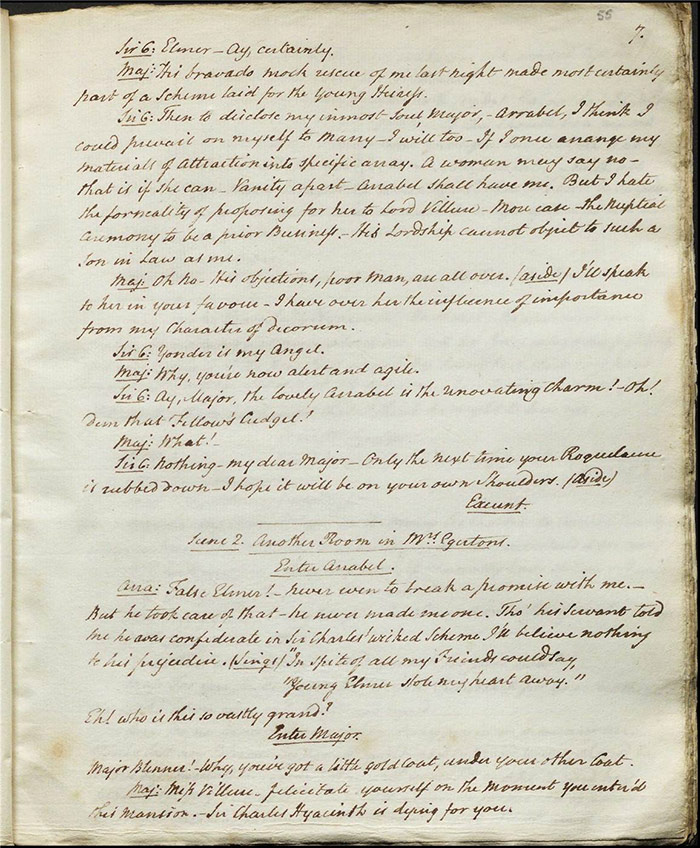

Blenner woos Arrabel on behalf of Sir Charles (f.55r); after she dismisses him, he tries another tack, telling her that it was a joke and that Sir Charles actually wants to marry Grace. This prompts a jealous response and, after being further angered by what she perceives to be the duplicity of Mrs Egerton, she goes to chase Grace around the house. However, Arrabel overhears Sir Charles and Blenner planning to dupe her into marrying Sir Charles. She enlists Grace to pretend to go along with the plan, all the while thinking she is Mrs Egerton’s daughter.

Plodden reveals his wealth and how he came about it to Jerkin just before Elmer angrily challenges him about his unpaid bills (f.59r). Jerkin claims that he hid the money away – right where Plodden found it. Mrs Egerton enters looking for her money which Elmer believes he has paid. In anguish, Mrs Elmer, in fear of her landlord, pleads with Appesley before Lord Villure enters. Appesley warns him that Mrs Egerton is too independent and proud to accept his help so he determines to terrify her into reconciliation by exacerbating her present financial difficulties.

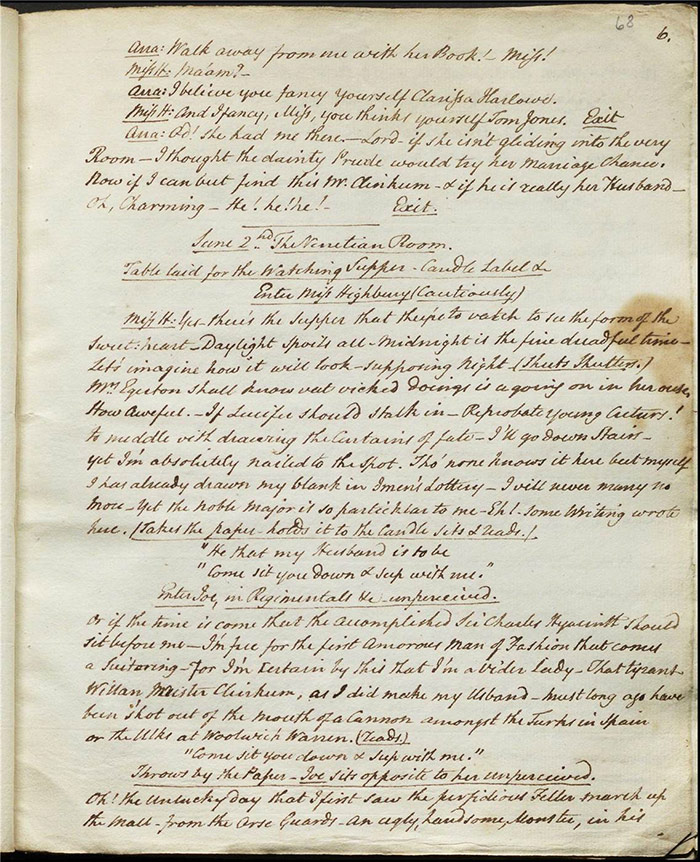

In the final act of the comedy, Arrabel is trying to hide in time for the supposed wedding between Grace and Sir Charles (f.63r). She encounters Plodden who has been corrupted by his wealth. She sings for him, trying to redeem him. Then she demands—with a pistol—that he dance in turn for her. Concluding that her generosity to him has corrupted him, she takes the money back. She then meets Miss Highbury whom she now suspects of being Clinkum’s wife; they quarrel.

Clinkum and Miss Highbury come face to face (f.68r). Lord Villure, without revealing himself demands his rent from Mrs Egerton. She is defended by the feisty Arabel who does not recognize her grandfather. To test her character, he tells her that he is dead and she was disinherited. Naturally, she responds with pity and love for him. Her nobility inspires Mrs Egerton to declare herself and they embrace. Lord Villure follows suit and all are reconciled. Elmer and Villure reveal Sir Charles to be a fraud and Elmer is free to marry Arrabel.

Performance, publication, and reception

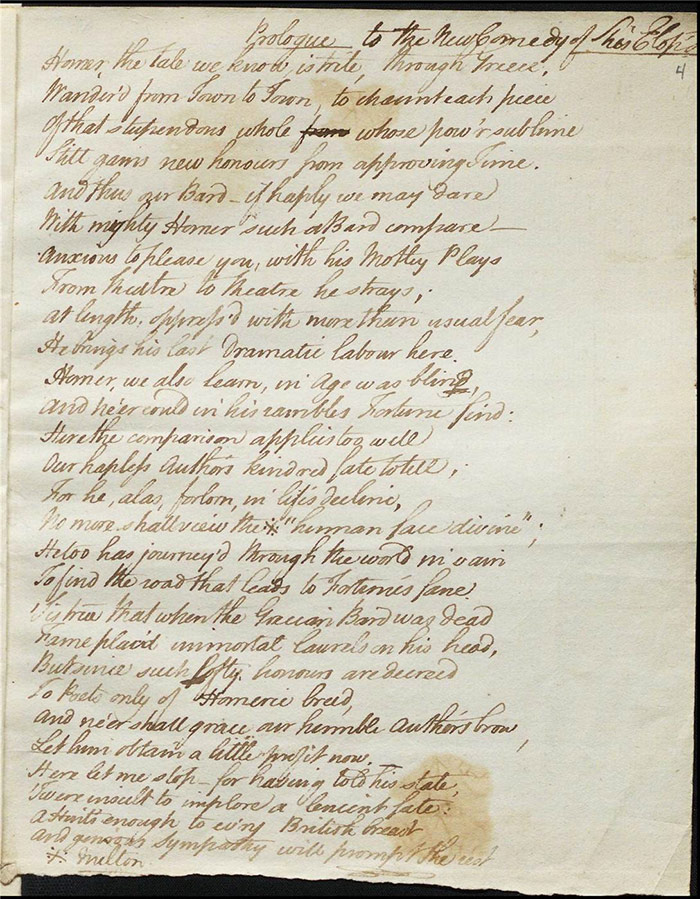

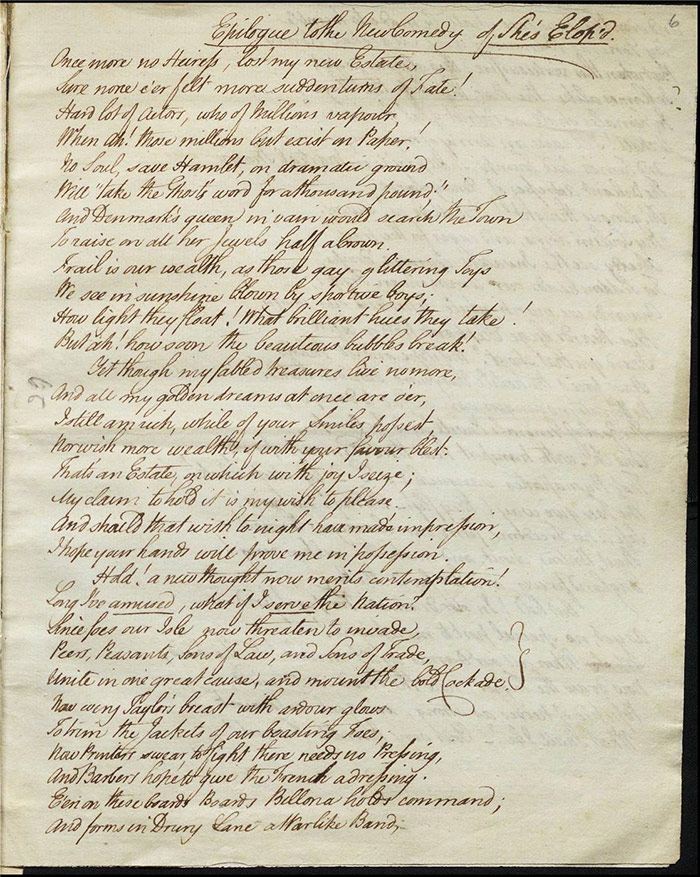

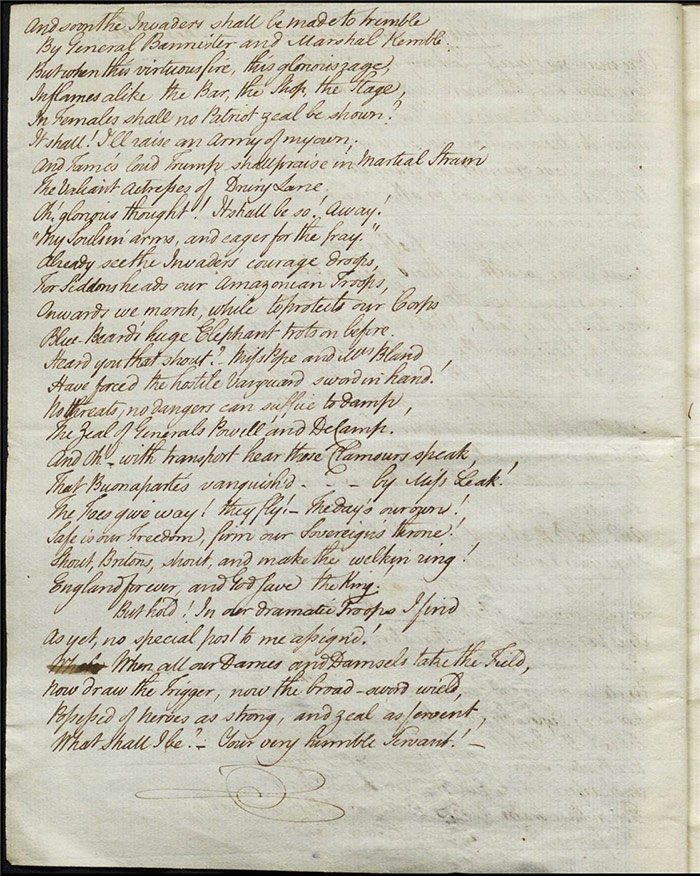

The play was submitted to the Examiner by Richard Wroughton on 30 April 1798. It was first performed on 19 May when it was produced as She’s Eloped at Drury Lane Theatre. M. G. Lewis supplied the epilogue and a ‘celebrated author’ wrote the prologue which talked of ‘Homer, poverty, and blindness’. O’Keeffe claimed that the ‘proud pang of a wounded spirit’ came over him and that he cut the prologue at the last minute (Recollections, II: 354); however, a couple of the reviews make explicit mention of this prologue which suggests that his wishes for ignored. She’s Eloped was O’Keeffe’s first ever play to be staged at this theatre; it was also his last ever new production. It had only one performance and the reviews which follow explain why.

Indeed, while O’Keeffe does not give any explicit reason for his retirement in 1798, the overwhelmingly negative reception of his play must have factored into his thinking. Lloyd’s Evening Post (18-21 May 1798) called it ‘radically defective’ while the Morning Chronicle (21 May 1798) stated that it ‘was received with a very strong mixture of disapprobation’.

The Observer (20 May 1798) was equally caustic:

It were a difficult task to trace the fable of the Play, and assuredly an unprofitable one. It has but little to boast, either on the score of interest or probability, and we cannot say more in favor of the language […] The characters are drawn without decision or novelty, and the piece, although supported by the whole comic power of the house [actors included Dorothy Jordan, Jane Powell, John Aickin, John Palmer], was marked throughout with decided disapprobation.

Towards the close of the last act, the performance was for some time suspended, by the wishes of the audience that it should terminate.

Reviews were equally damning in The Times (21 May), Evening Mail (18-21 May), Express and Evening Chronicle (19-22 May), and, the Star (22 May). The Oracle and Public Advertiser (21 May 1798) was somewhat more sympathetic towards this ‘medley of exquisite sentiment and low buffoonery’ although the reviewer admits his kindness is due to the sympathy elicited by the prologue’s allusion to O’Keeffe’s poverty and blindness. Ultimately, the reviewer suggests that O’Keeffe confine himself to ‘lighter pieces’: the complexities of a 5-act comedy or plays that deal with social issues are now beyond him.

The play was never published. .

Commentary

Before we deal with the manuscript emendations proper, we may take note that, unusually, the manuscript contains correspondence between the various parties involved in submitting and licensing the play which allows us to build a more detail picture than usual of the licencing process.

Larpent was uneasy with the radical sentiments expressed in the play. Anna Larpent recorded that she was ‘home employed all Eveng [2 May] reading Quarter Day A play for licencing with all the Cynical feelings of Holcroft, levelling the great & rich by abuse’ (Diary of Anna Larpent). Prompted by these reservations, John Larpent wrote to the Lord Chamberlain, Salisbury, for advice. Salisbury replied on 4 May: ‘I have received the favor of your Letter with a Play calld Quarter Day; after the account you give of it, it is impossible for me to permit it to be performed’ (f.i).

The ideological association with Holcroft—an ‘acquitted felon’ of the Treason Trials—was enough to damn it as far as Salisbury was concerned. However, it seems as if O’Keeffe was not prepared to give up without a fight. He made an appointment with Salisbury to plead his case (and presumably to make explicit that Holcroft was not the author). This meeting was successful: Wroughton passed the manuscript back to O’Keeffe for alteration as this subsequent letter to Larpent dated 12 May indicates:

Sir,

Mr O’Keefe this day had an Interview with the Marquis of Salisbury, who received him very kindly and referred him to your Decision with Alterations – As your Wishes towards the Author I am sure from your last Letter are favourable, I take the Liberty of sending this to remind you how near the Season draws towards a Conclusion – and at the same Time to say how anxious we are to advertize the Play for Thursday next under the new Title of She’s eloped! – with every Respect I am Sir

Your very humble Sert

Rd Wroughton (f.3r)

O’Keeffe made the required cuts to the manuscript although not in an entirely abject fashion as Wroughton’s next to Larpent shows:

Monday May 14 1798

Sir,

The Proprietor & the Author are much obliged by the Dispatch you have so kindly used with this Comedy – The Alterations pointed out are strictly attended to – except reserving a trifling Quotation from Shakespeare used by Arrabella to Plodden – “You Goneril with a white red Beard”. – but even this, if objected to, shall be expunged – I have ordered the Play to be Advertized for Performance on Thursday next under the Title of She’s Eloped! the Prologue & Epilogue are sent with this – I hope in this and every other theatrical Transaction to meet your Approbation. I am Sir

Your very humble Sert

Rd Wroughton /.At the request of Mr O’Keefe I inclose this Slip of Paper –

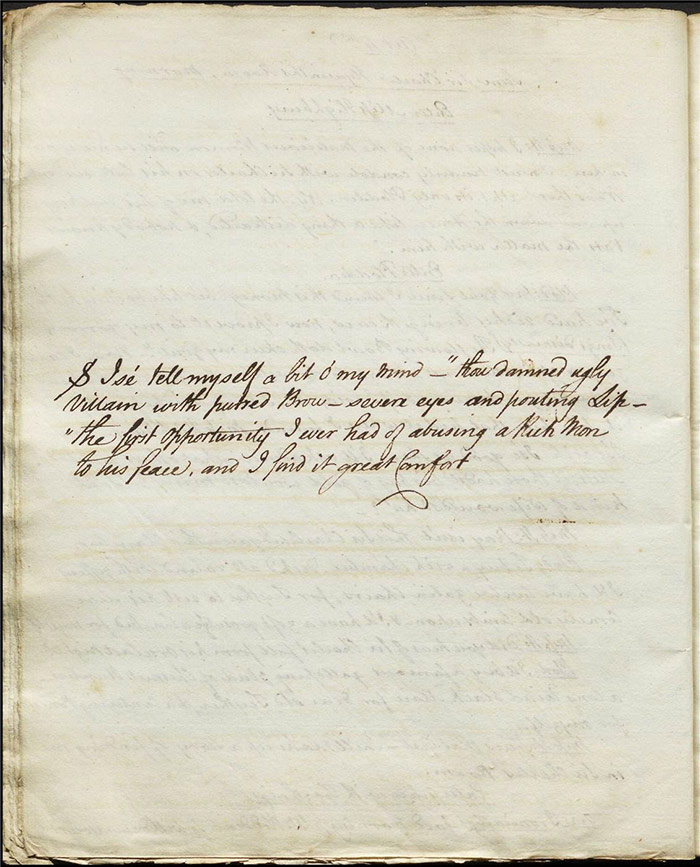

Mr O’Keefe presents his Compts & Thanks to Mr Larpent – and wishes if Mr L– is not positively averse to it – that the Character of Mr Plodden in Act 4 Page 2 – may make use of the following Passage, which Mr O’Keefe supposes will produce Laughter innocently abusing himself at the Glass – “I’se tell myself a bit ‘o my Mind – thou damned ugly Villain with pursed Brow – severe Eyes & pouting Lip – “ the first Opportunity I ever had of abusing a Rich Man to his Face and I find it great Comfort – (f.1r-2r)

Wroughton felt sufficiently emboldened to schedule the opening night for Thursday 17 May but the manuscript for Holcroft’s Knave or Not? (LA 1192) contains a further letter (bound there in error) from Salisbury to Larpent on She’s Eloped which revealed continuing reservations despite, it would appear, not bothering to read the play at all:

Sir

I was favoured with your Letter on Tuesday morning, and I think proper to observe, that tho the Offensive Passages are omitted, yet if the Plot appears to you to have the same Tendency as Knave or Not which you mentioned in a former Letter, you must not allow the Play to be performed.

The Morning Chronicle (17 May 1798) reported that the planned performance of She’s Eloped for that day was cancelled ‘on account of the indisposition of a principal performer’. This may indeed have been the case but the suspicion must remain that the delay was down to Larpent needing some time to consider or him demanding further cuts – O’Keeffe’s belated request to include a passage that talked of a character being comforted by abusing the wealthy must have given him pause. The play was finally performed on Saturday 19 May but O’Keeffe lamented that ‘the comedy of “She’s Eloped” as I originally wrote it, and the comedy as altered by me and acted, were nearly distinct pieces. I was forced to cut out, mangle, and change whole characters and incidents’ (Recollections, II: 353).

The manuscript shows a number of emendations in pencil and in pen. The correspondence traced above should be taken into account when trying to determine the chronology of the textual interventions. The majority of interventions relate to Plodden, a country bumpkin comic figure, and his criticisms of the wealthy and titled classes. John Bannister, who took the part, said ‘This was a very good part when I first got it, but now I can make nothing of it’ (Recollections, II: 353).

One indicative example of the cuts related to critique of the ruling classes will suffice here. In this early appearance, reminiscent of the Porter scene in Macbeth, Plodden goes to open the door to the house:

Plod: Open Geates! – A time for all things, and now is mine to think on what I be (goes over to looking glass) thou poor mon! all avoid thee – woe bee’s written on thy feace – thous’t ever a grievous Story – knock at Street door, Friend cries from Parlour. I bee’s not at hoame! – “Get in & friend be going out – that he needn’t ax you to sit down he talketh to thee walking about – Bow – and thou’rt mean – hold up thy head, and thou’rt saucy. If invited, the day be not named – Come unask’d, and thou’rt as welcome as a Shower of rain to an Easter Beau, and a bill of Costs to the nonsuited, a pimple on the nose of a pretty Lady, a new bridge to an old Ferryman – 13 on a Lottery number, a Soldier’s Billet to a Public house, or a lighted Candle to a Powder Magazine.(f.9v)

The passage is boxed and crossed out in pen and also in pencil. It is striking that it is a stretch to read this passage as aimed directly at the ruling classes: Plodden seems more filled with self-pity at his alienation from fellow humanity in general. It is perhaps only the word ‘bow’ that brings the question of class explicitly into consideration. Certainly, it seems that this cut tells us much about the degree of sensitivity around perceived slights of the social order in the 1790s. Further cuts related to criticism of the ruling orders can be seen at (f.34r), (f.50r; this is the passage referred to by O’Keeffe in his note given above), (f.63r), (f.64r), (ff.69r-70r), (f.72r).

There is one other cut that is worth noting separately and it is in the first stanza of the play’s concluding song. Here Elmer sings to his mother-in-law to be, Mrs Egerton:

Here in your peaceful mansion happy stay,

And meet with smiles the dreadful Quarter day

Now that your need for Friendship’s at an end (f.74r)

In every Stranger you shall find a Friend

It is not clear why Larpent might have objected to these two lines. Perhaps he detected a hint of implied licentiousness or perhaps it was more a case of him believing that the unregulated and indecorous social mingling suggested by the final line was problematic. Or there remains a contemporary allusion in these two lines that needs to be discovered.

Further reading

Olivia Baldwin and Thelma Wilson, ‘O’Keeffe, John (1747-1833)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn October 2006

[http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20658, accessed 18 November 2018]

Helen Burke, ‘Worlding the Village: John O’Keeffe’s ‘Excentric’ Pastorals’ in Ireland, Enlightenment and the English Stage, 1740-1820, ed. David O’Shaughnessy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 226-248.

L. W. Conolly, ‘A Case of Political Censorship at the Little Theatre in Haymarket in 1794: O’Keefe’s Jenny’s Whim; or, The Roasted Emperor’, Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Theatre Research 10:2 (1971), 34-39.

Anna Larpent, Diary of Anna Larpent, HM 31201 vol 2, f.237r.

Stewart S. Morgan, ‘The damning of Holcroft’s Knave or Not? and O’Keeffe’s She’s Eloped’, Huntington Library Quarterly 22:1 (1958), 51-62.

John O’Keeffe, Recollections of the Life of John O’Keeffe, 2 vols (London: Henry Colburn, 1826).