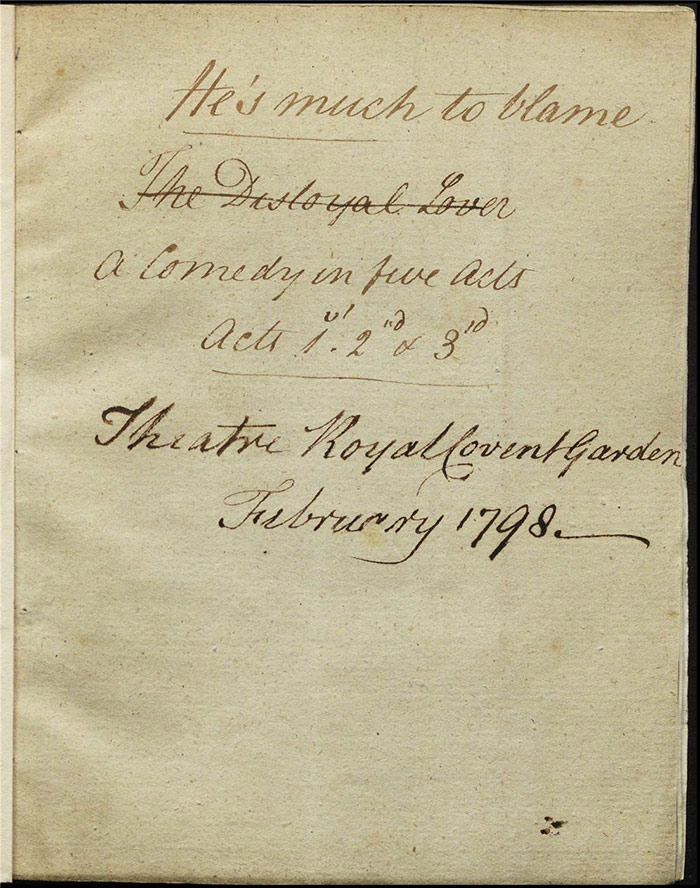

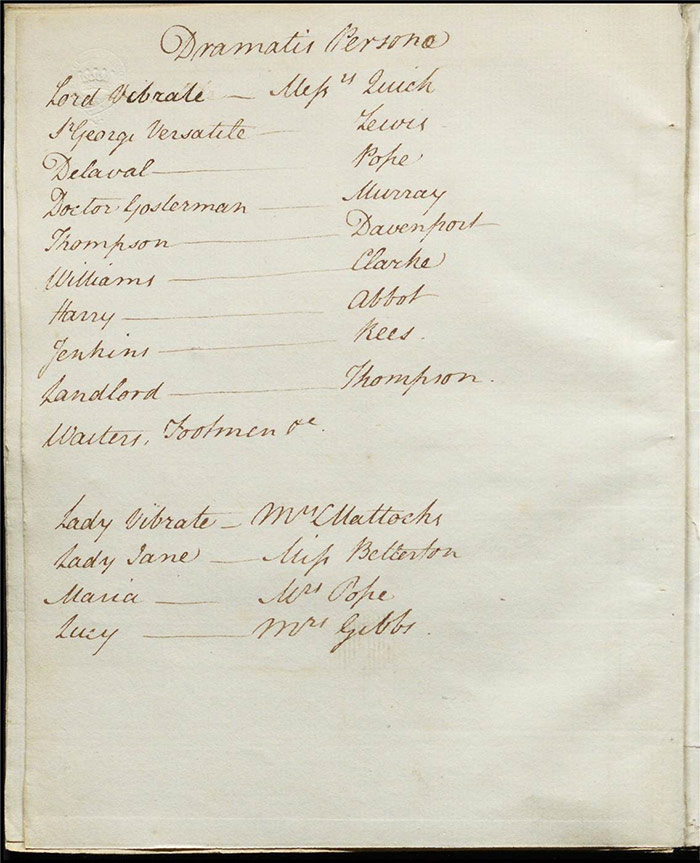

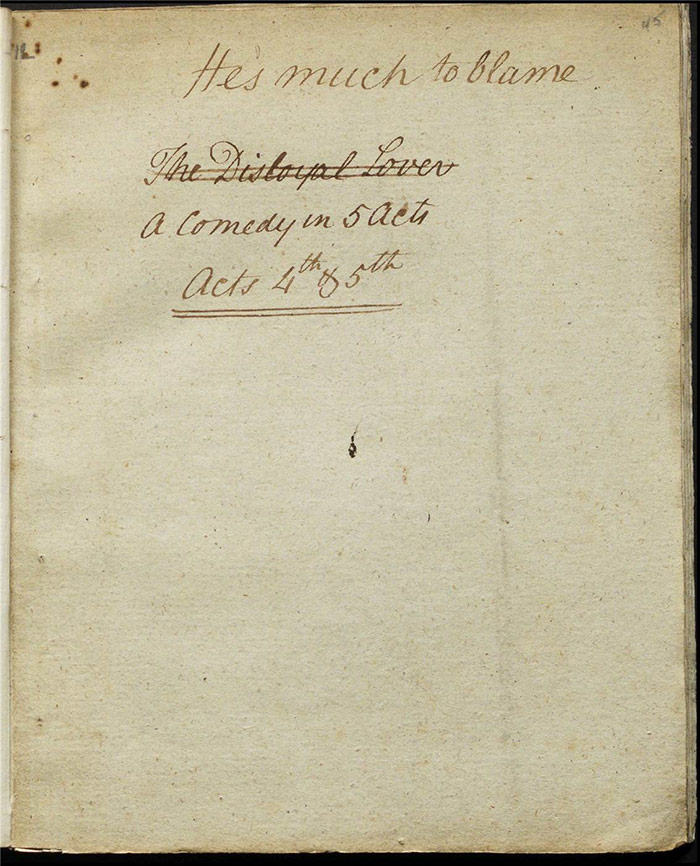

He's Much to Blame (1798) LA 1195

Author

Thomas Holcroft (1745-1809)

Holcroft’s early life was one as an itinerant, first as the son of travelling pedlars and then as a regional actor. He moved to London in 1777 where he soon married (for the third time). He got some acting work at Drury Lane and began writing dramatic afterpieces, poems, essays, a serial novella, and, based on his own experiences, an epistolary picaresque novel Alwyn, or, The Gentleman Comedian (1780). He also wrote two books related to the 1780 Gordon Riots.

He had his first modest dramatic success with Duplicity (CG, 1781). He spent some time as a journalist in Paris where he saw Beaumarchais’s Le Mariage de Figaro (1784). His adaptation Follies of a Day (CG, 1784) was his first major success with 28 performances that season. Further modest success followed with The Choleric Father (CG, 1785) and Seduction (DL, 1787).

Holcroft met William Godwin in 1786 and their friendship was immediate and consequential for both of them. Godwin’s diary and letters of those early years bear testament to the importance of Holcroft to Godwin and vice versa. His plays from those years reflect his growing sense of the need for social and political reform with The Road to Ruin (CG, 1792) achieving 37 performances in its opening season and becoming part of the repertory into the next century.

He also published two novels Anna St Ives (1792) and Hugh Trevor (part 1, 1794; part 2, 1797) which offered a sweeping critique of corrupt British institutions. Holcroft’s political activities eventually saw him charged with treason in 1794 along with a number of other leading radicals such as Thomas Hardy, John Thelwall, and John Horne Tooke. After the acquittal of this trio, the charges against Holcroft and the other reformers were dropped. However, the stigma of being an ‘acquitted felon’ (as he was smeared by MP William Windham) would haunt him afterwards and affect his theatrical career.

He left England in 1799 and spent a couple of years in Germany before returning in 1802. He had some more literary success including A Tale of Mystery (1802) which has a claim to be the first melodrama in the British tradition. He fell out with Godwin over what he believed to be a character attack in Godwin’s novel Fleetwood (1805); the pair were reconciled on Holcroft’s deathbed in 1809.

Plot

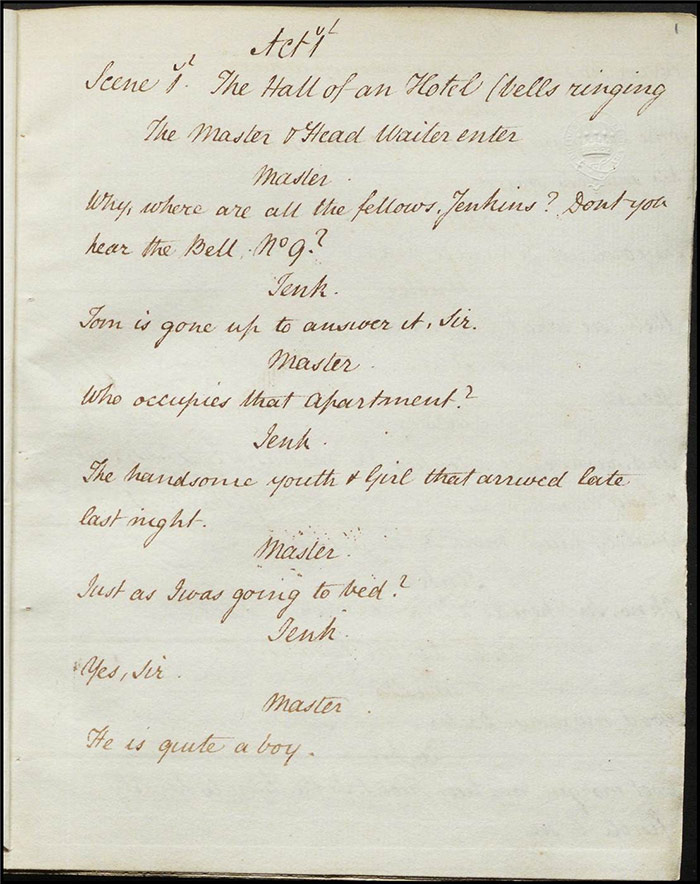

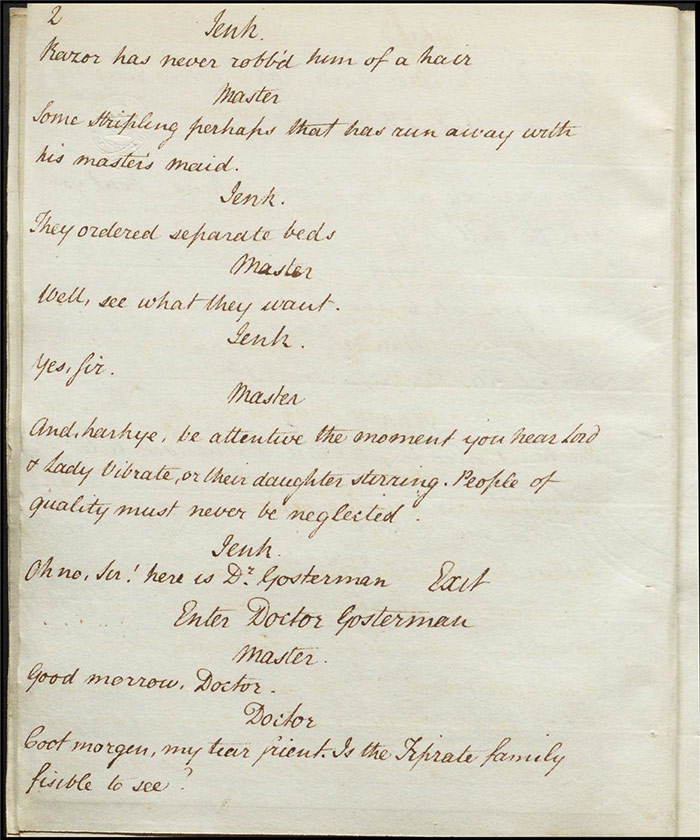

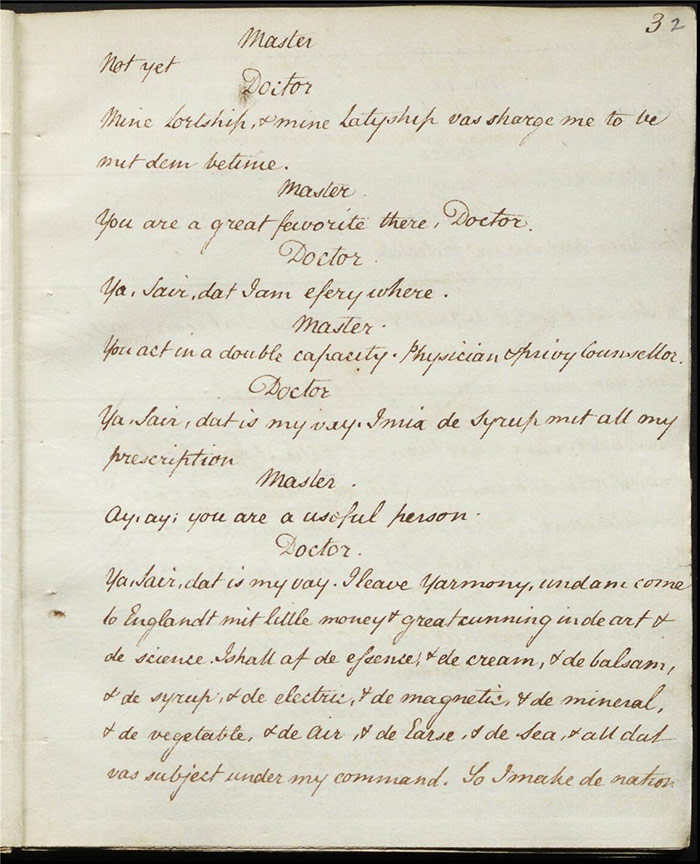

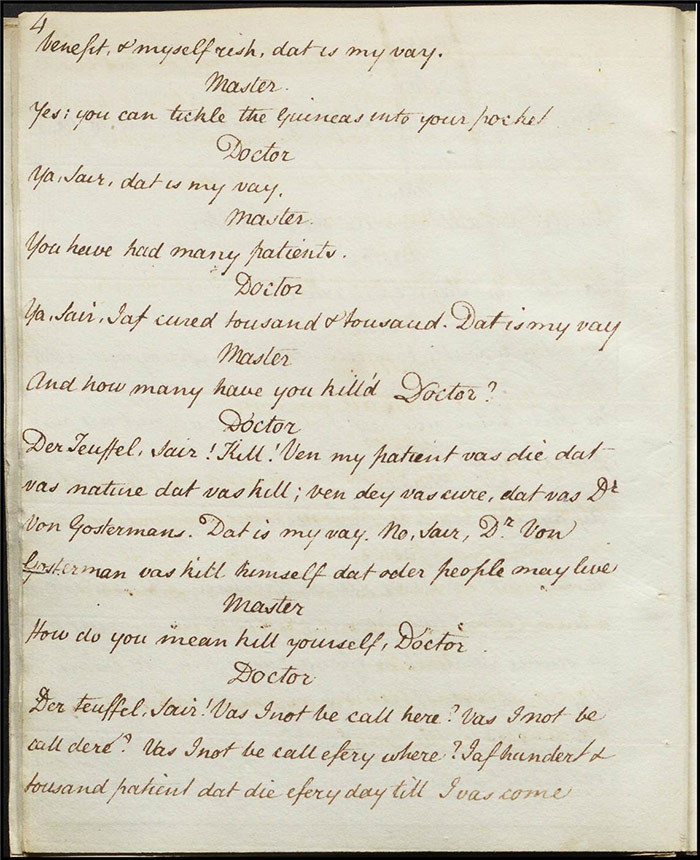

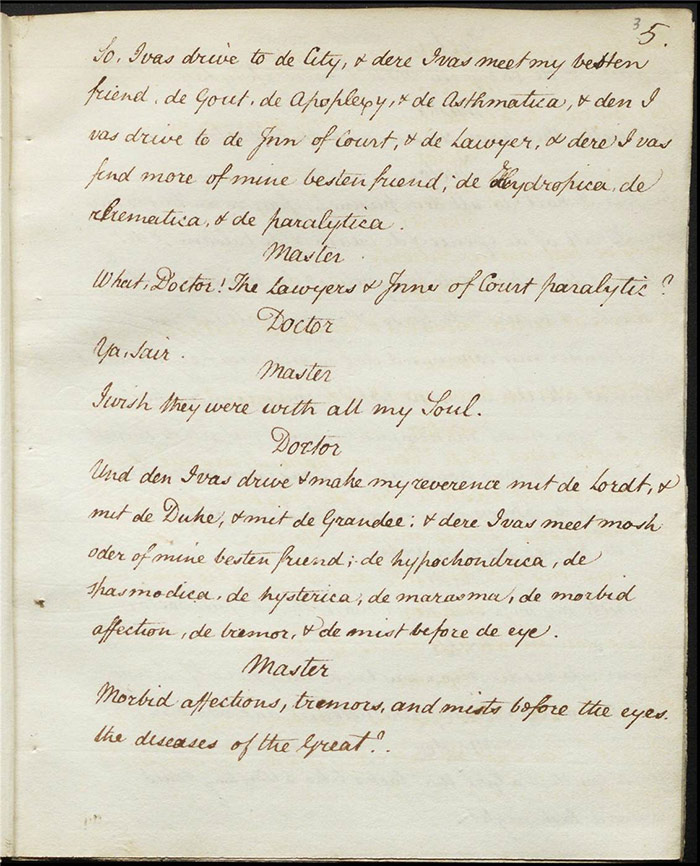

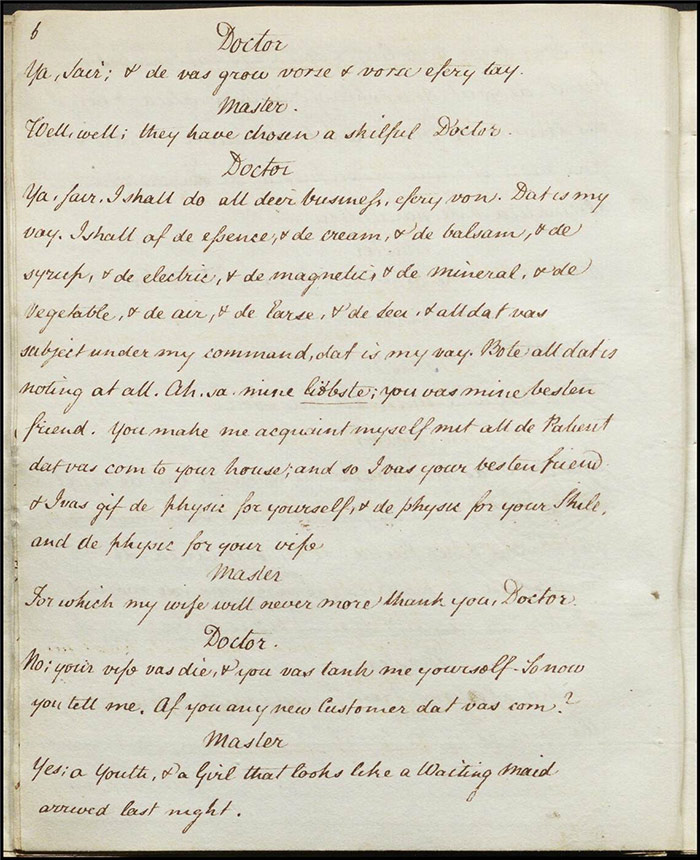

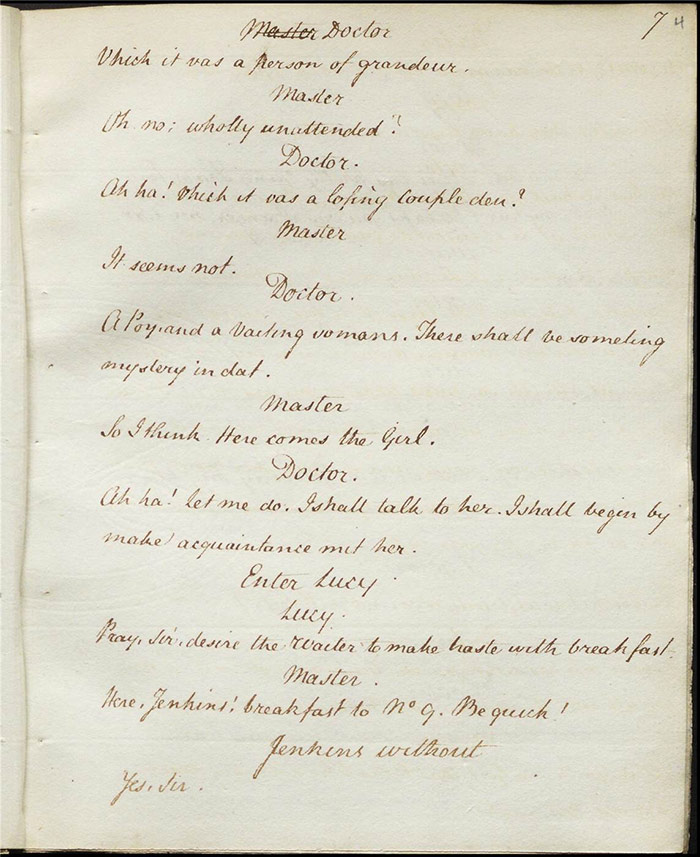

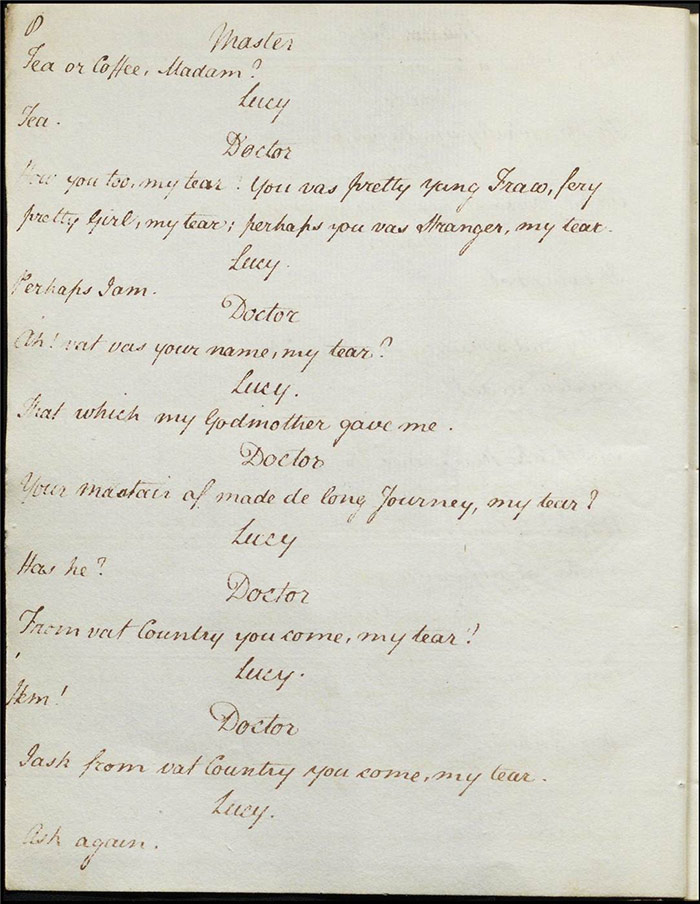

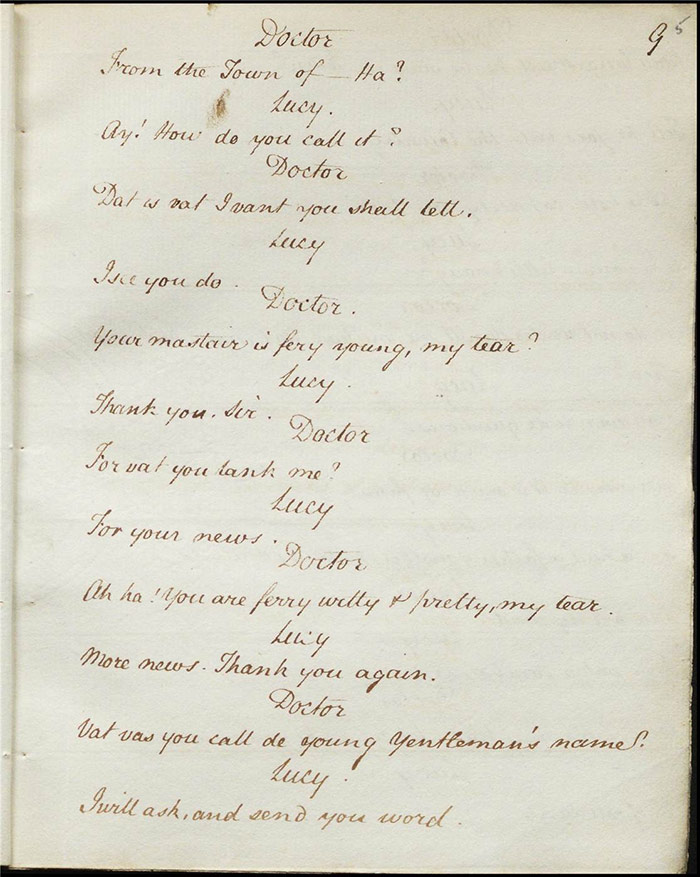

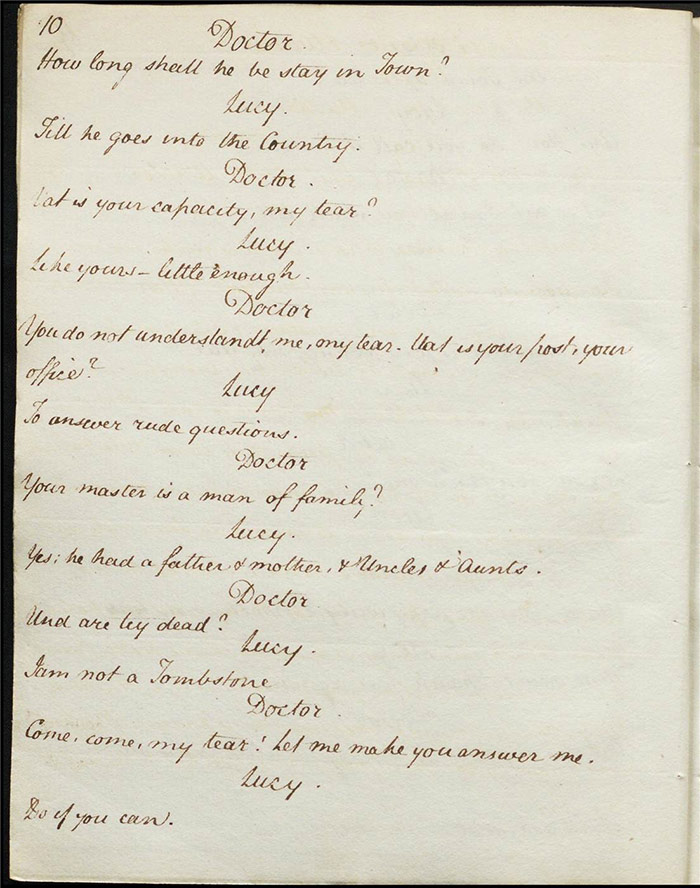

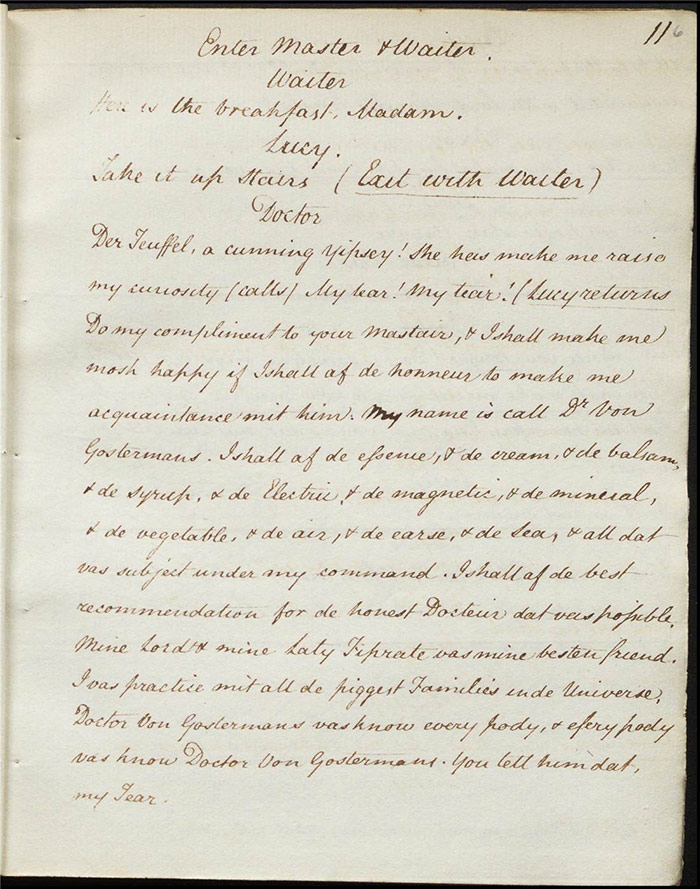

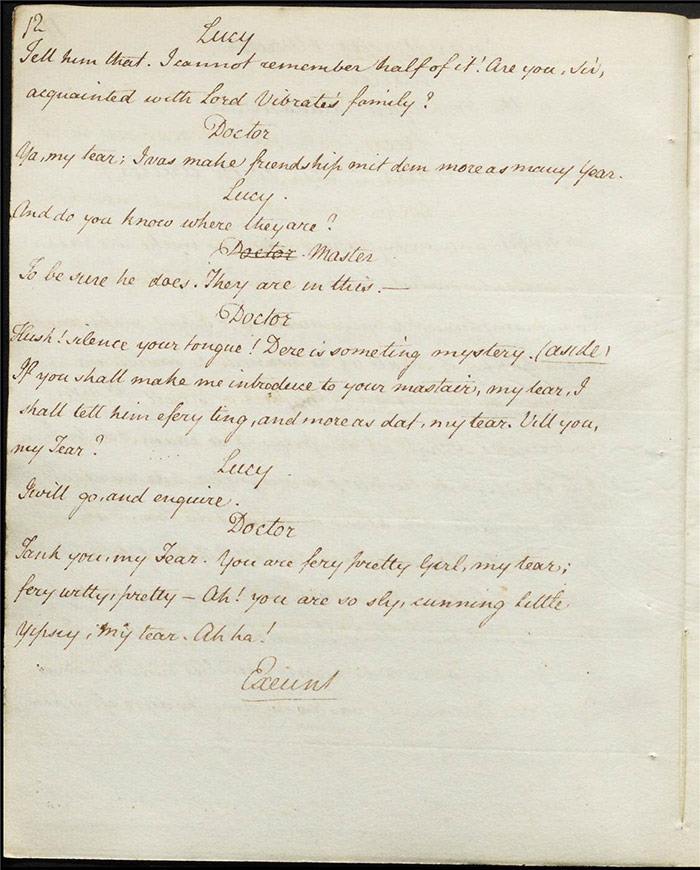

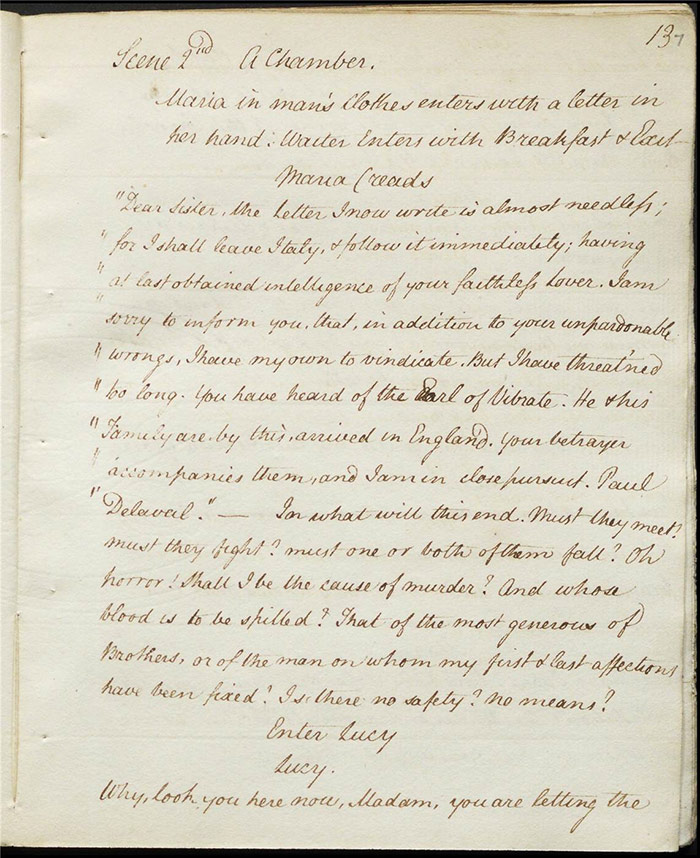

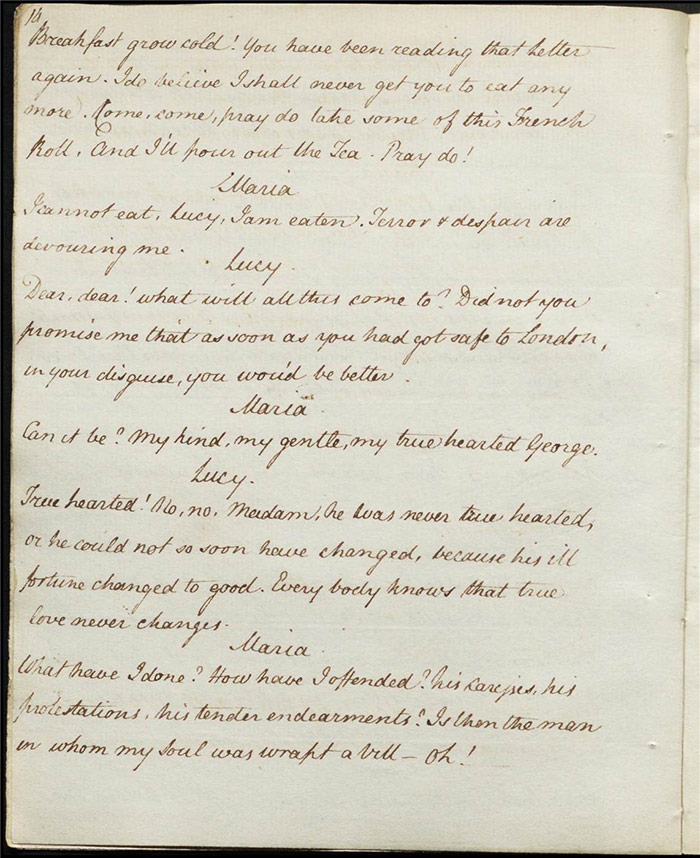

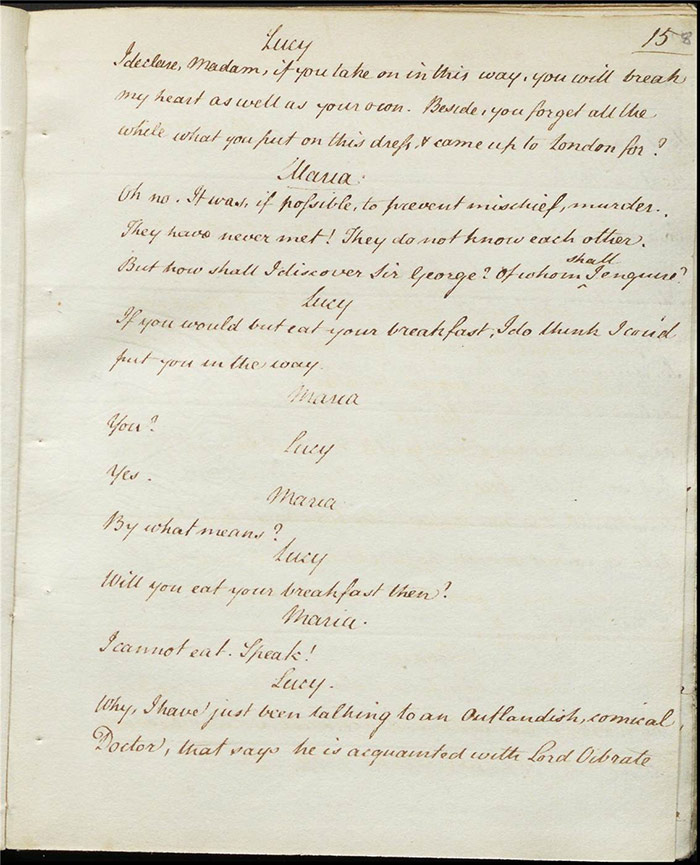

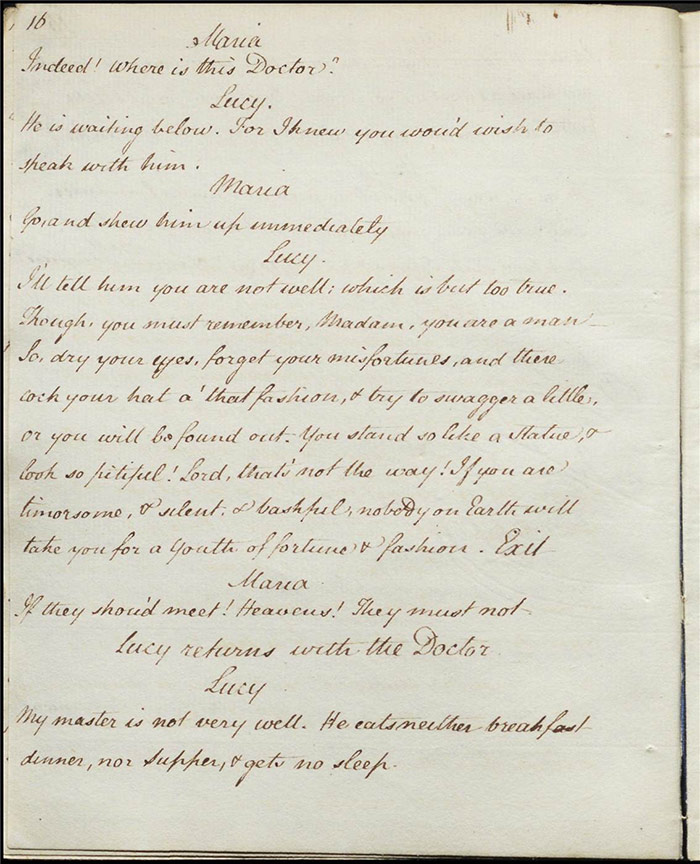

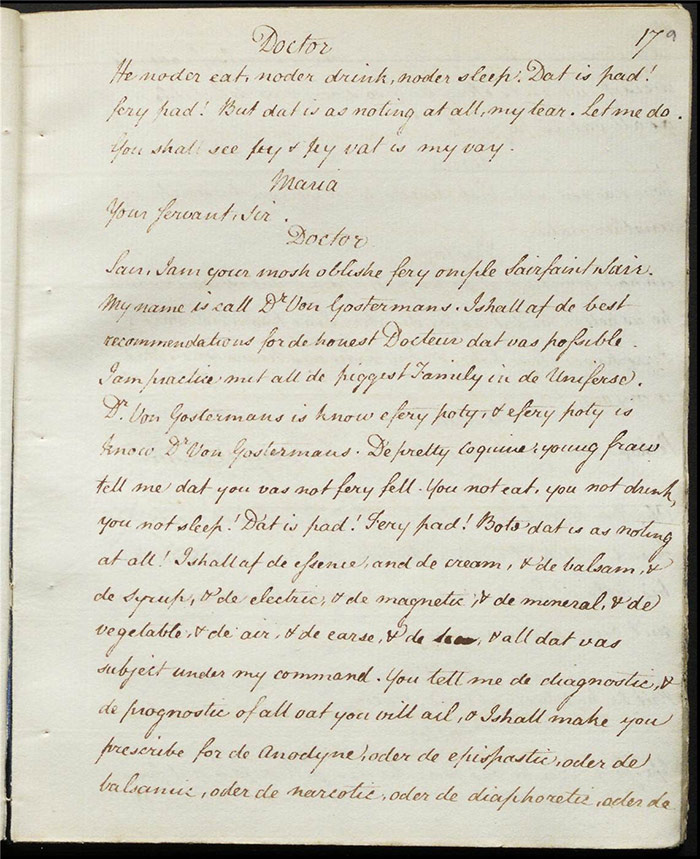

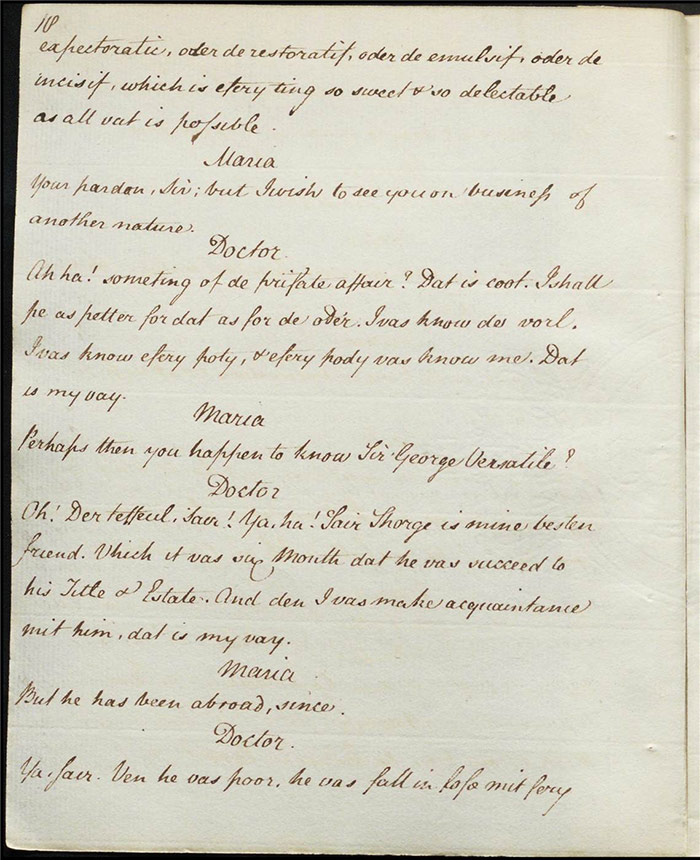

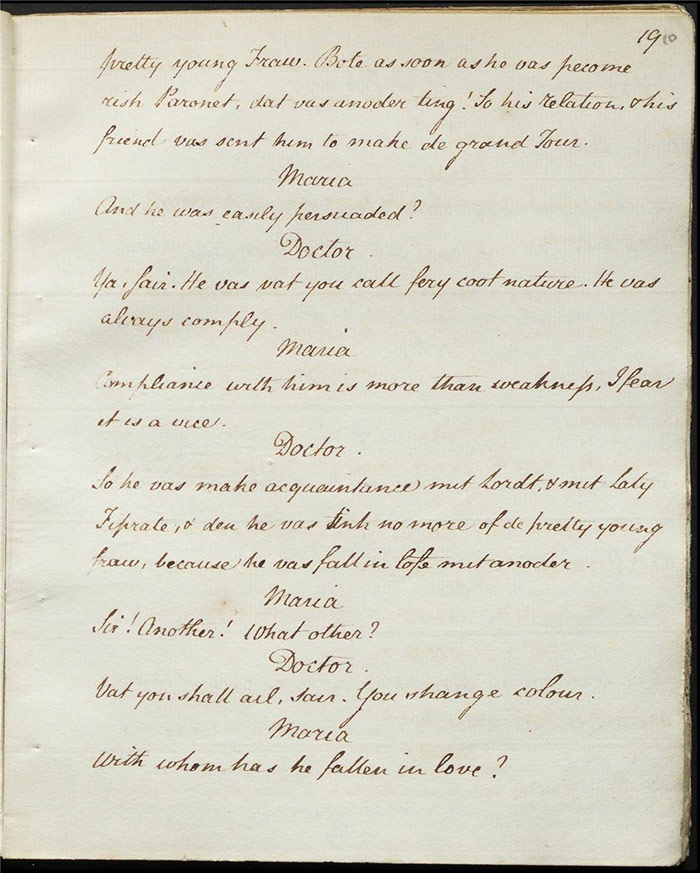

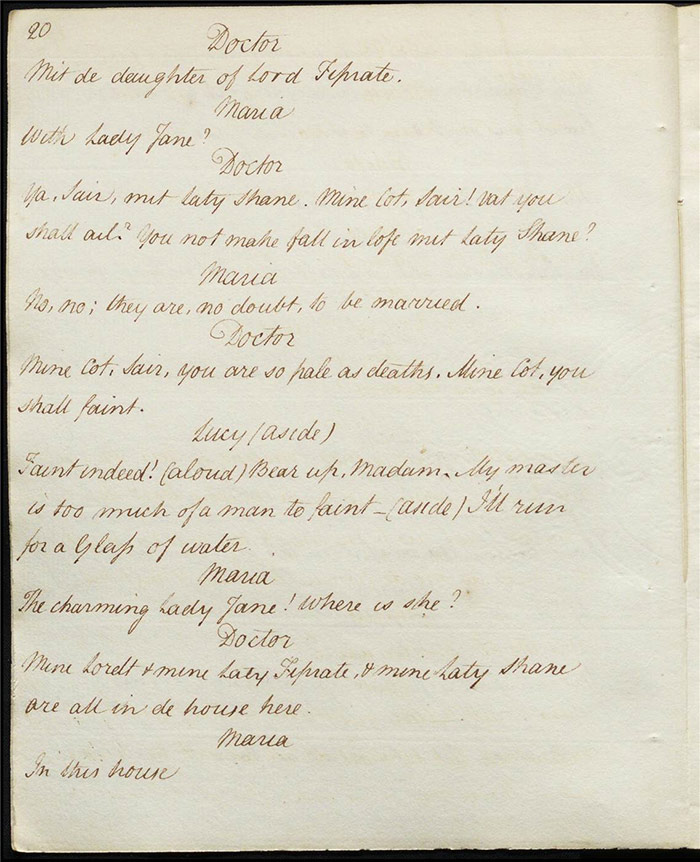

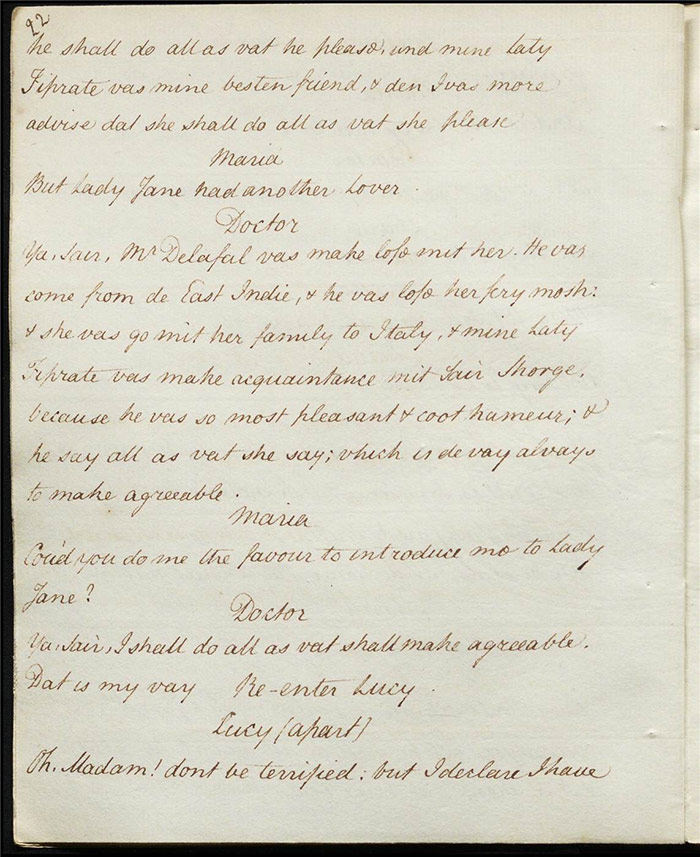

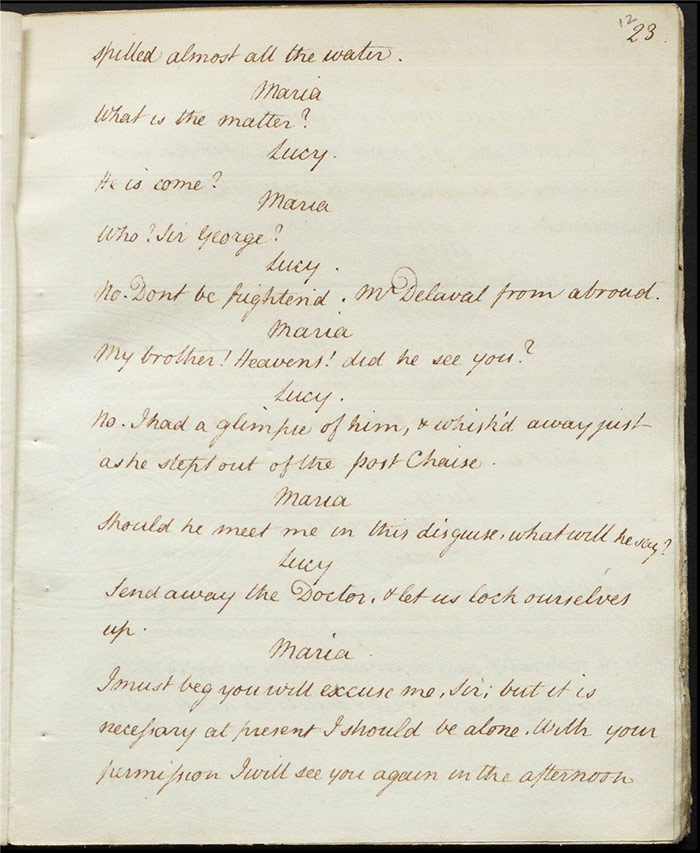

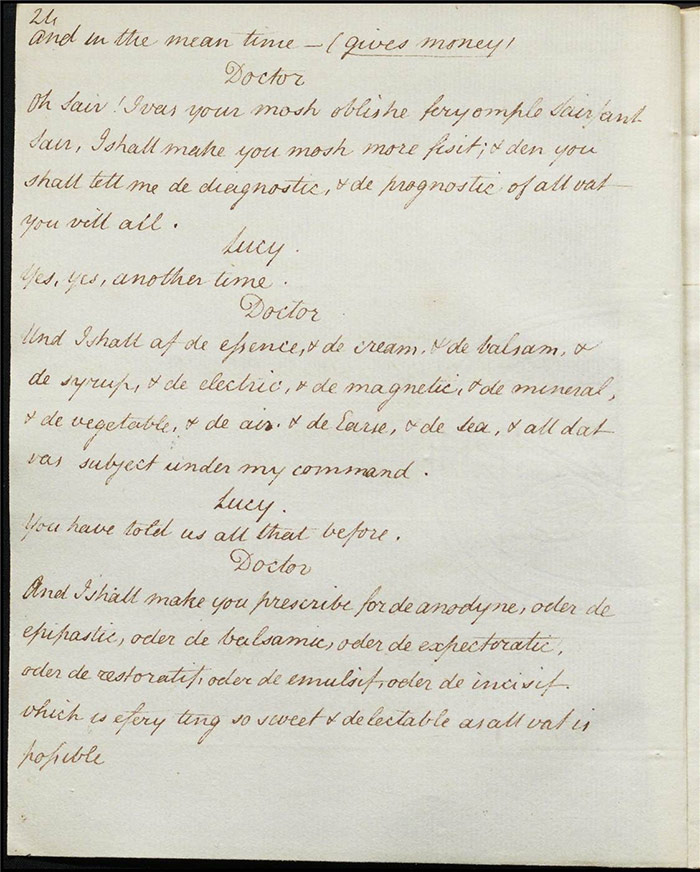

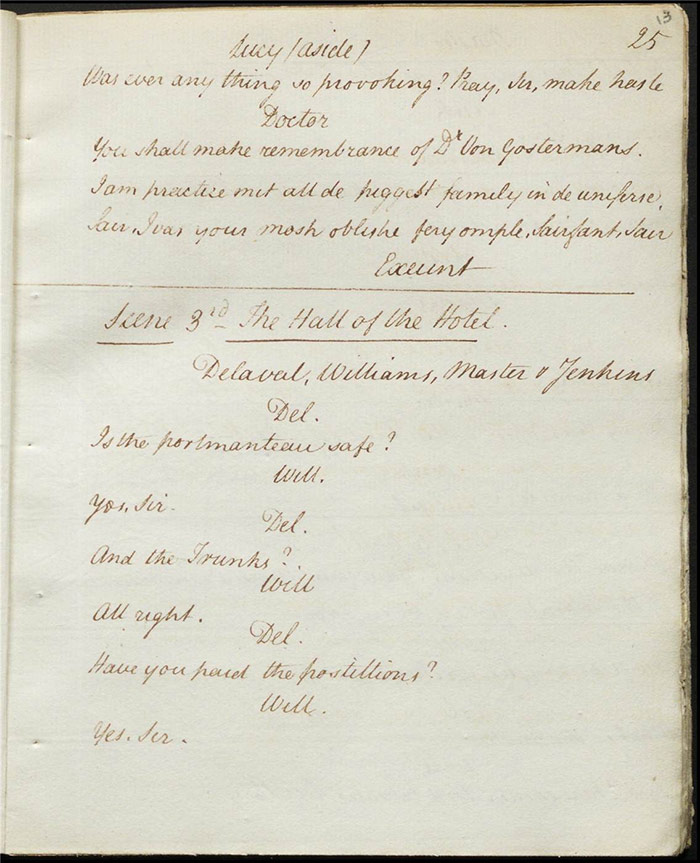

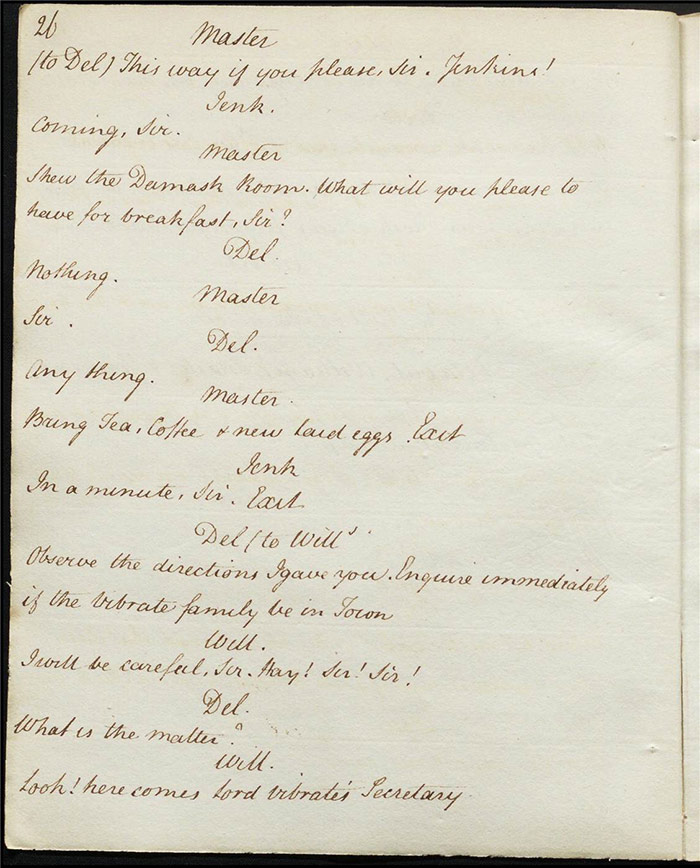

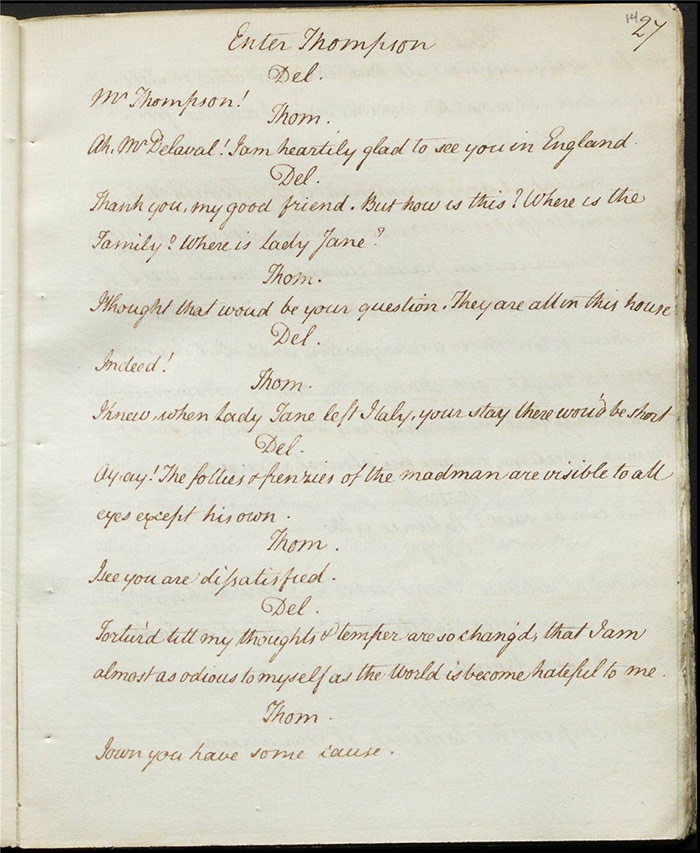

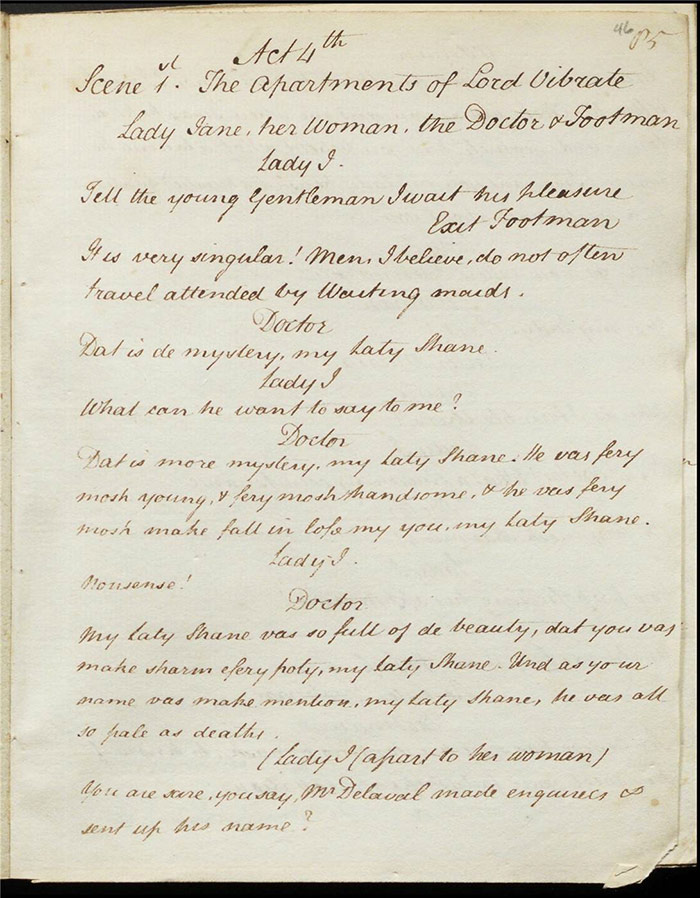

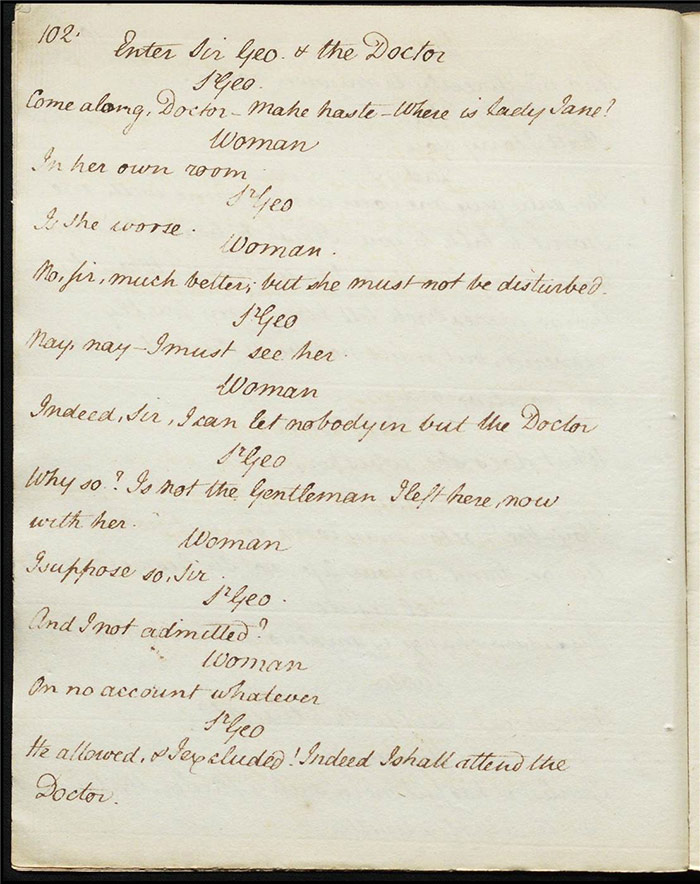

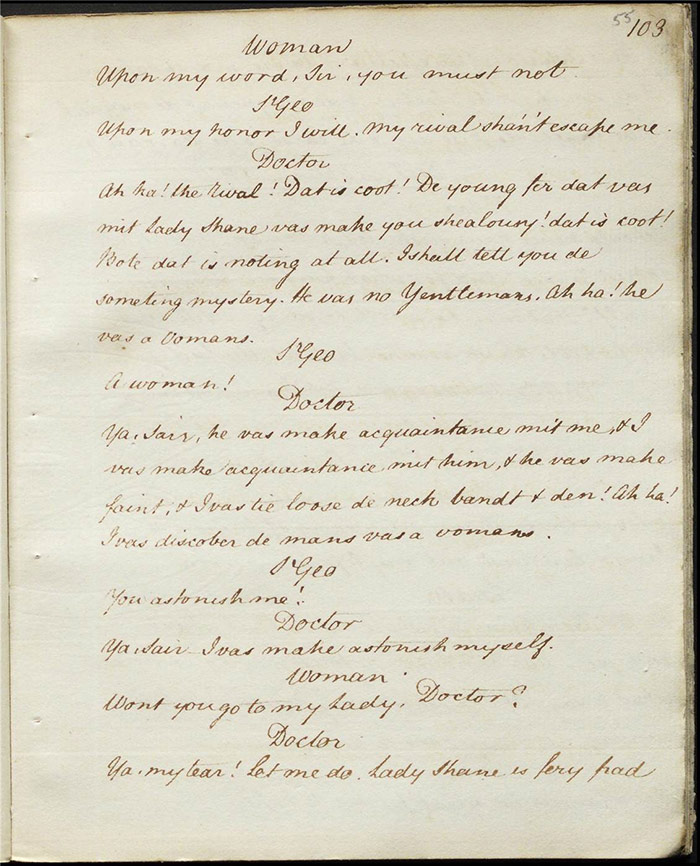

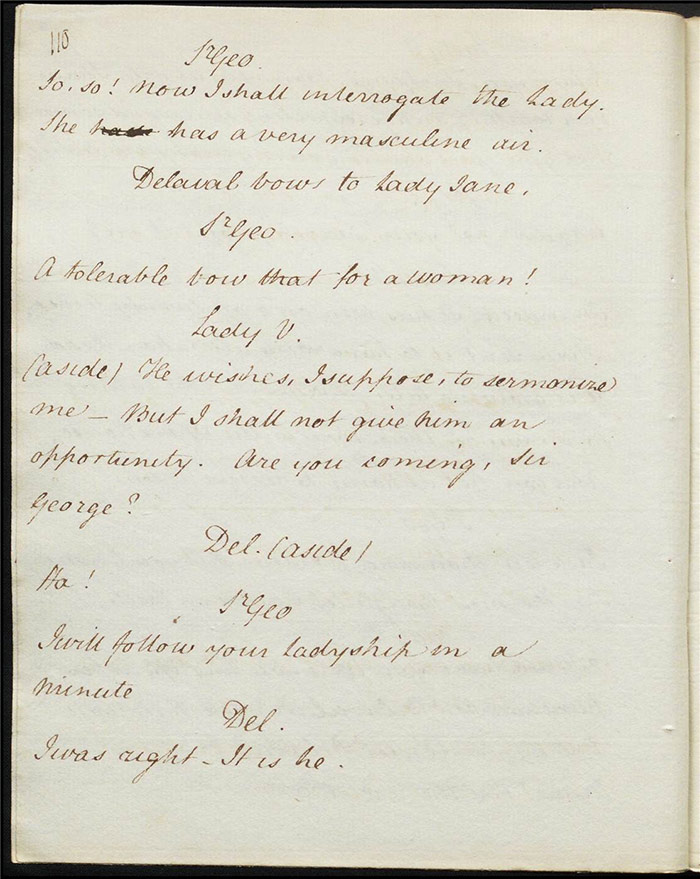

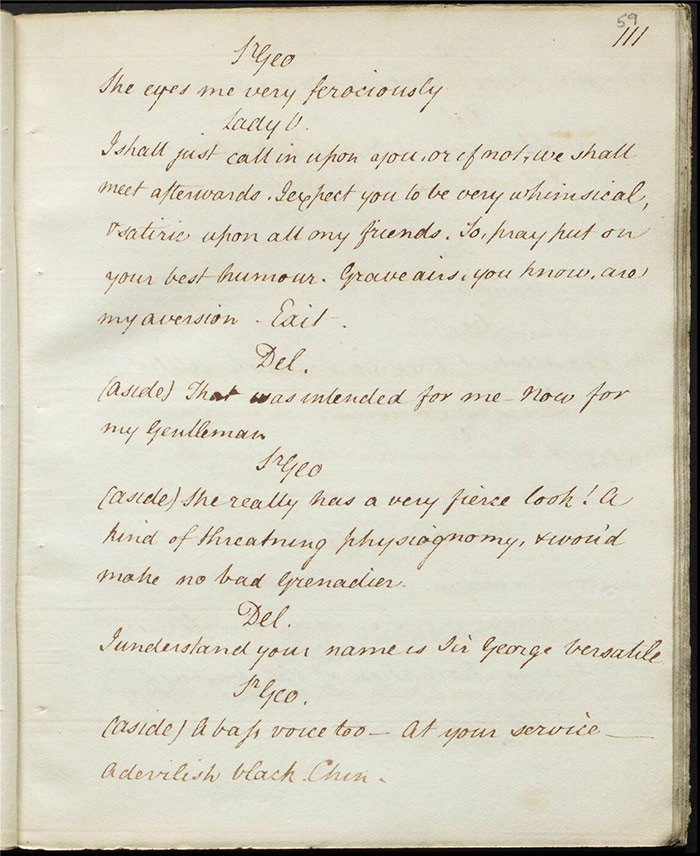

The action opens at a London hotel where a number of different and connected parties are assembled. Maria, disguised as a man and accompanied by her resourceful maid Lucy, is seeking Sir George Versatile. She had been his lover up until he inherited his title but, at the inn, Maria is informed by the comical German quack Dr Gosterman that Versatile is now in love with Lady Jane Vibrate. Lady Jane, of course, is also resident at the inn along with her parents. Added to the mix is Mr Delaval, Maria’s brother, who is in hot-blooded pursuit of his sister and determined to defend her honour after her alleged jilting at the hands of Sir George.

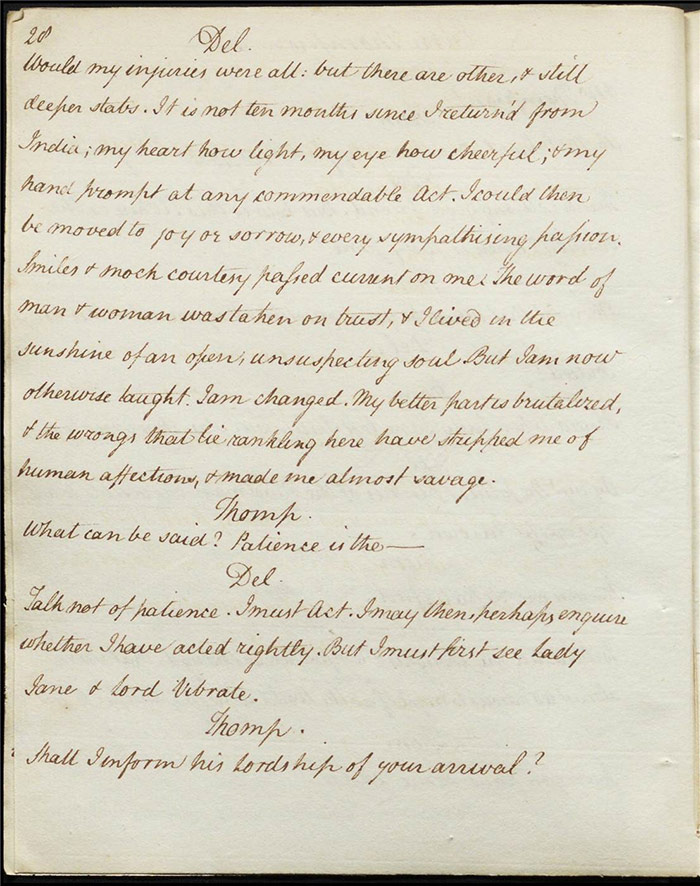

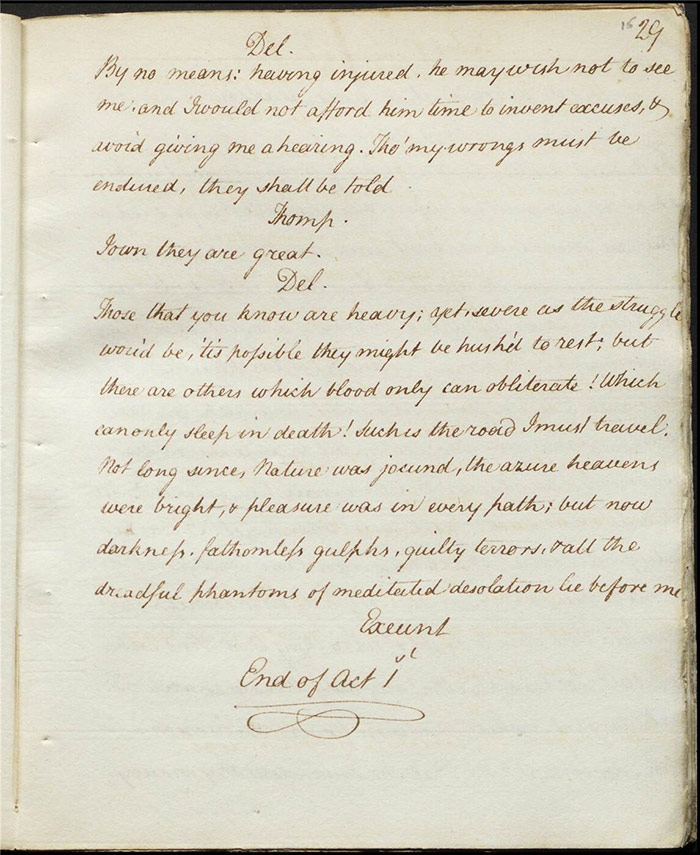

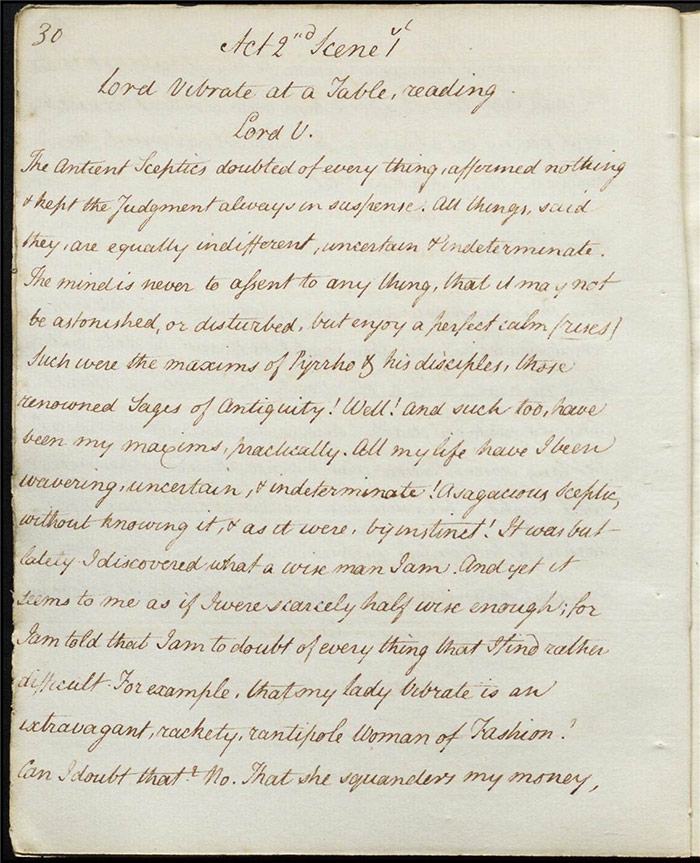

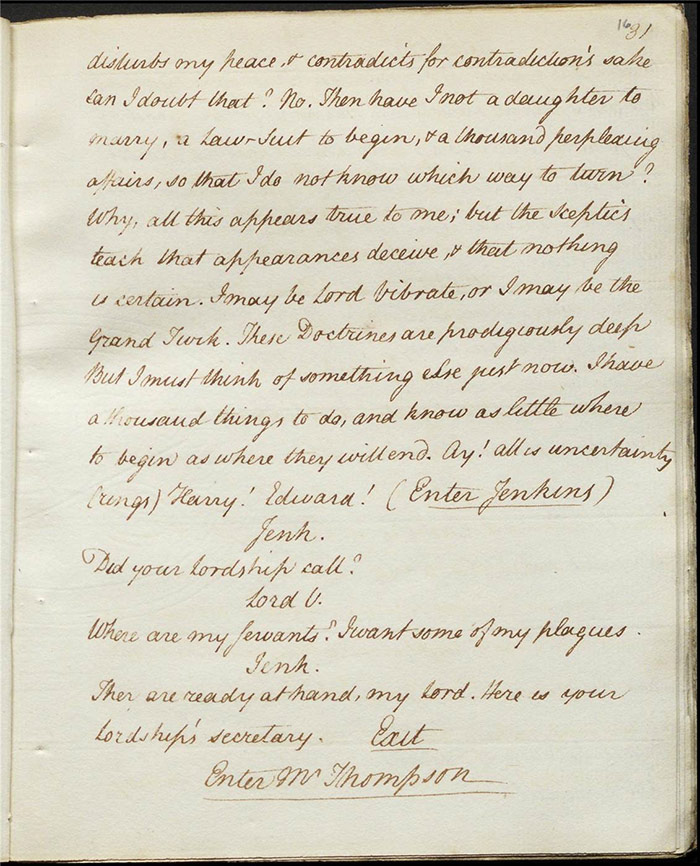

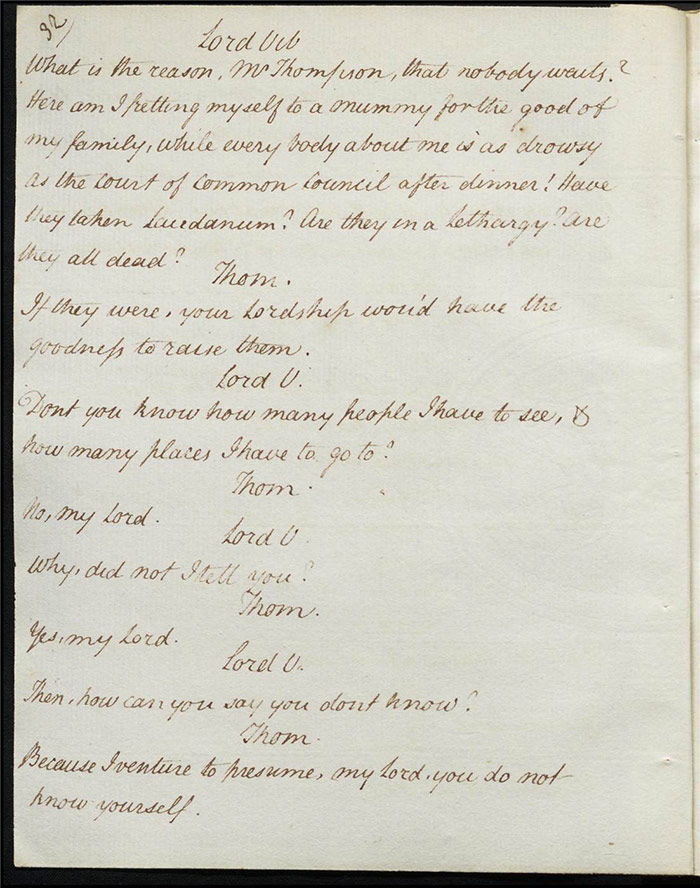

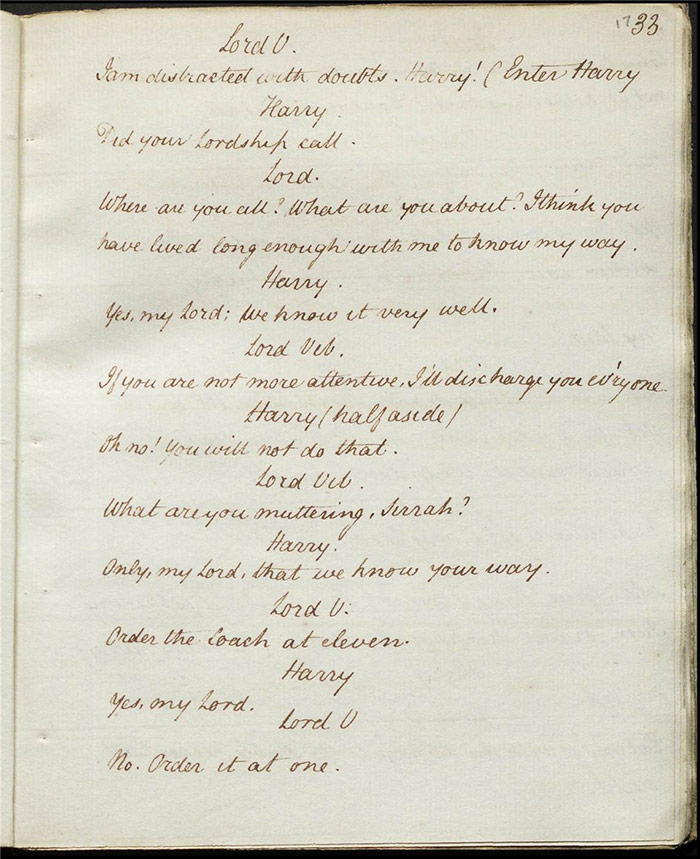

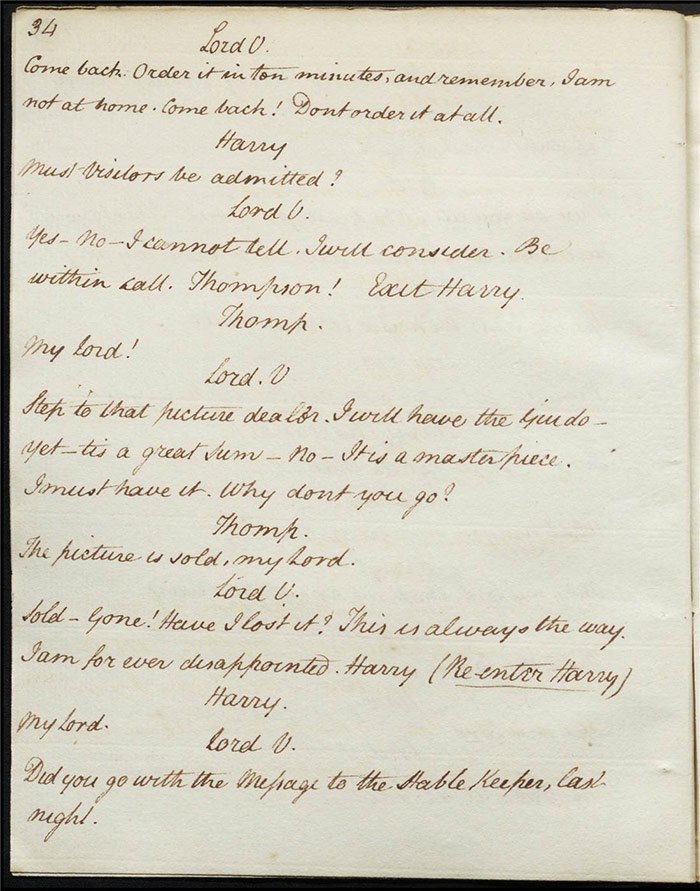

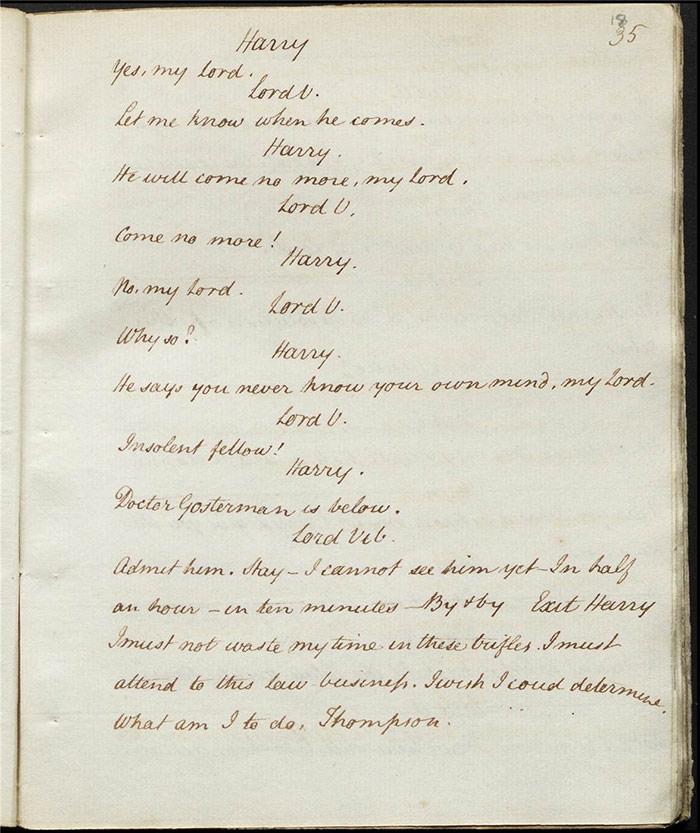

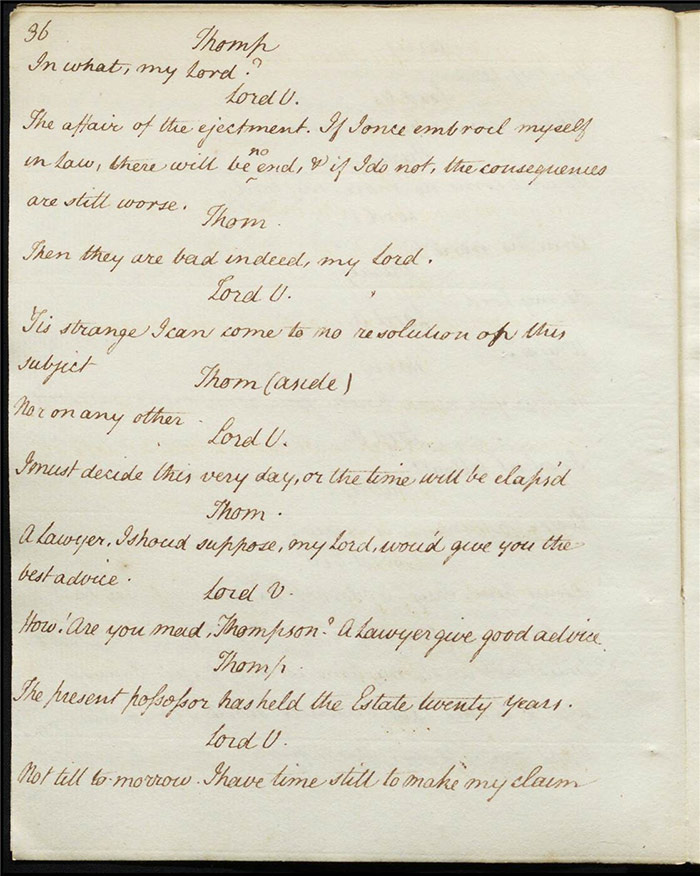

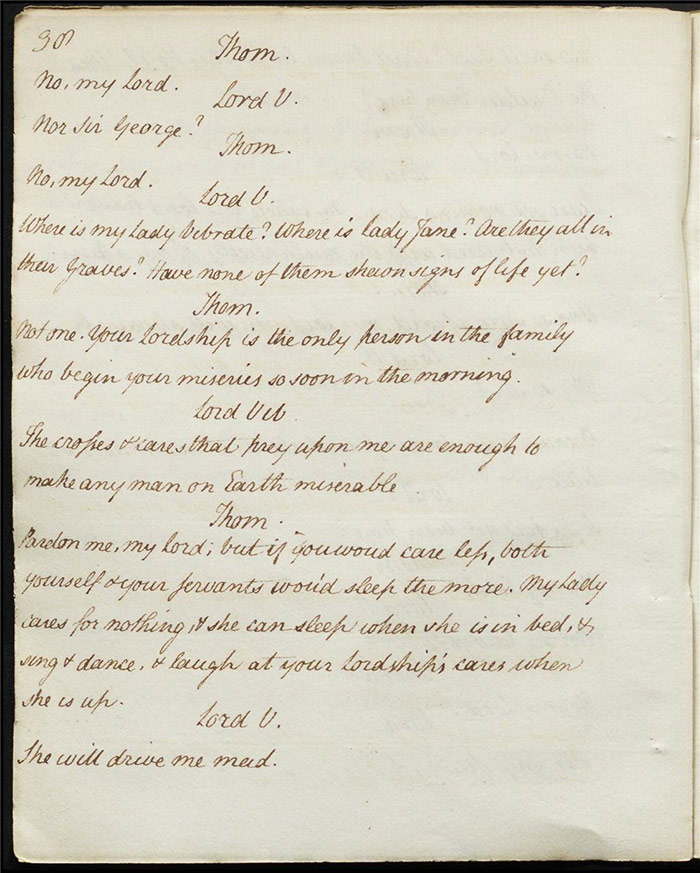

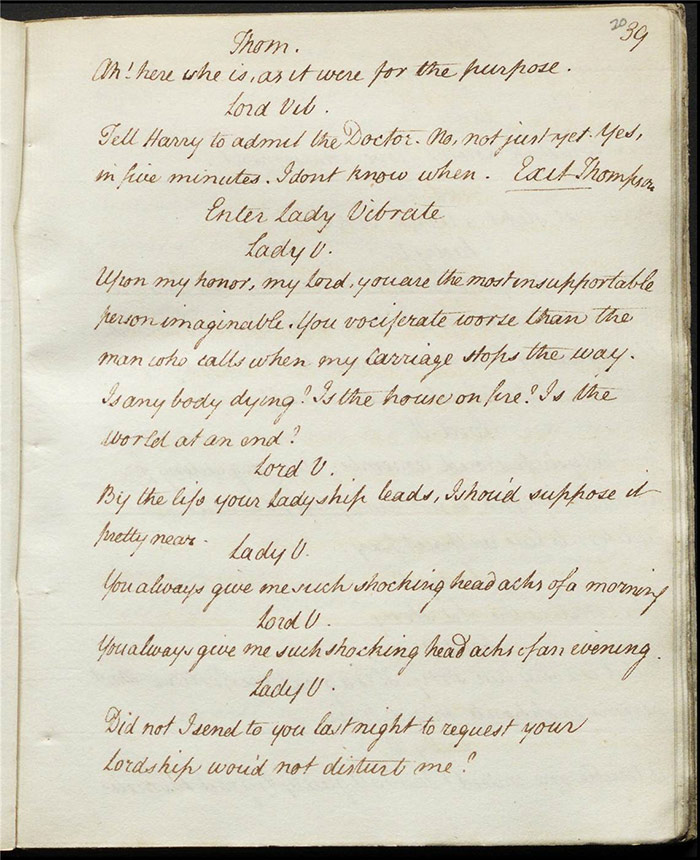

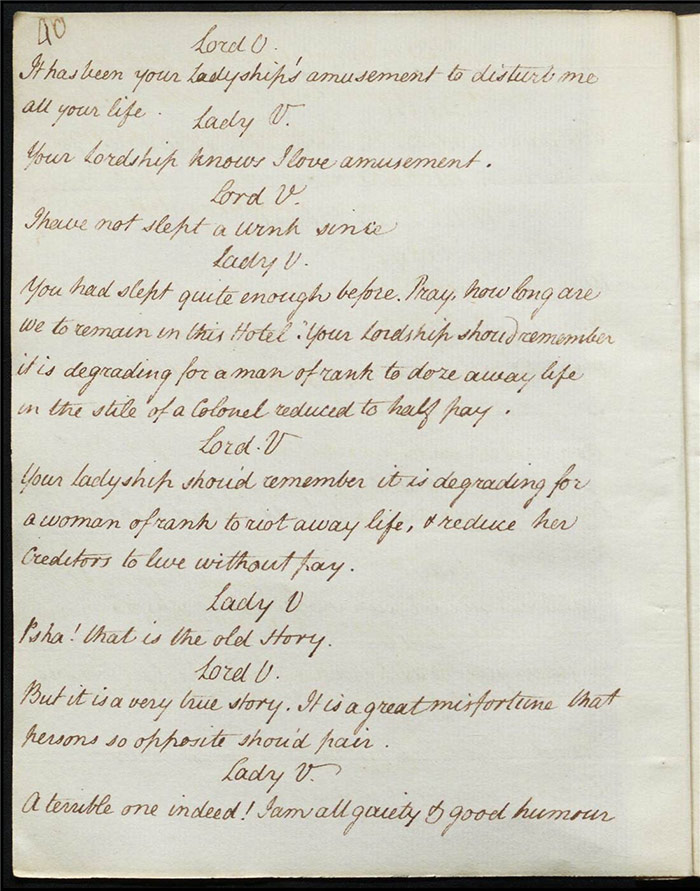

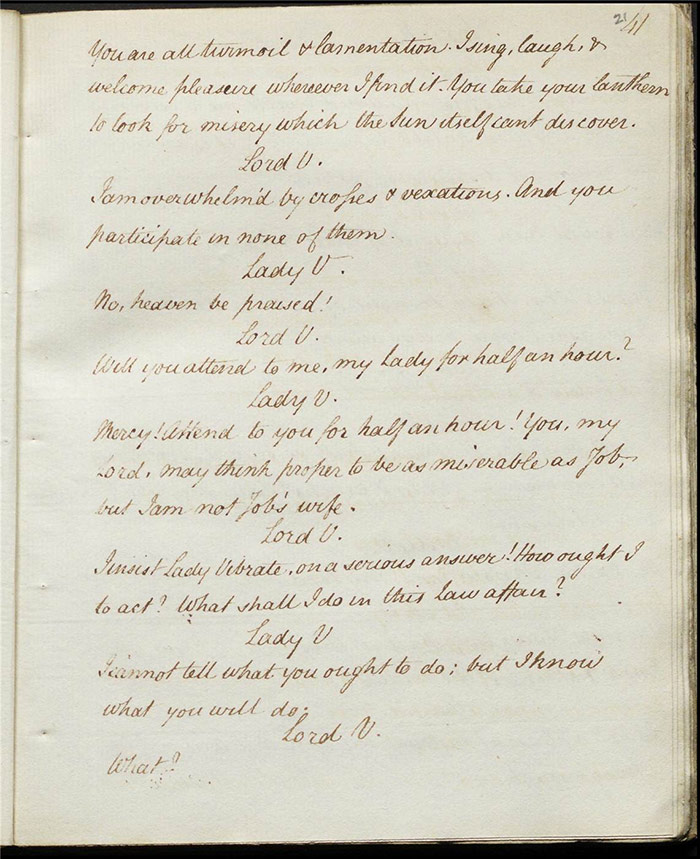

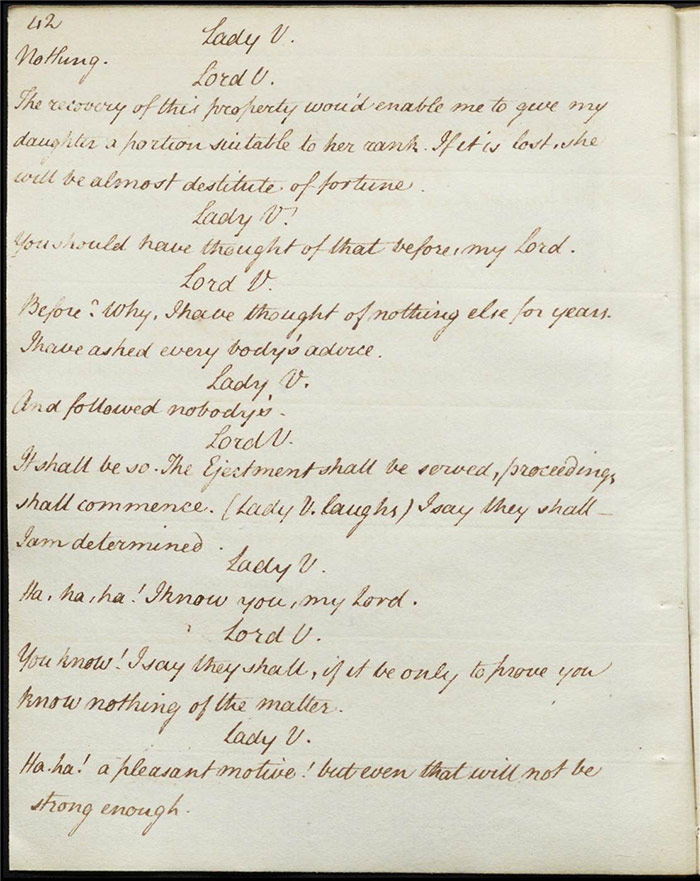

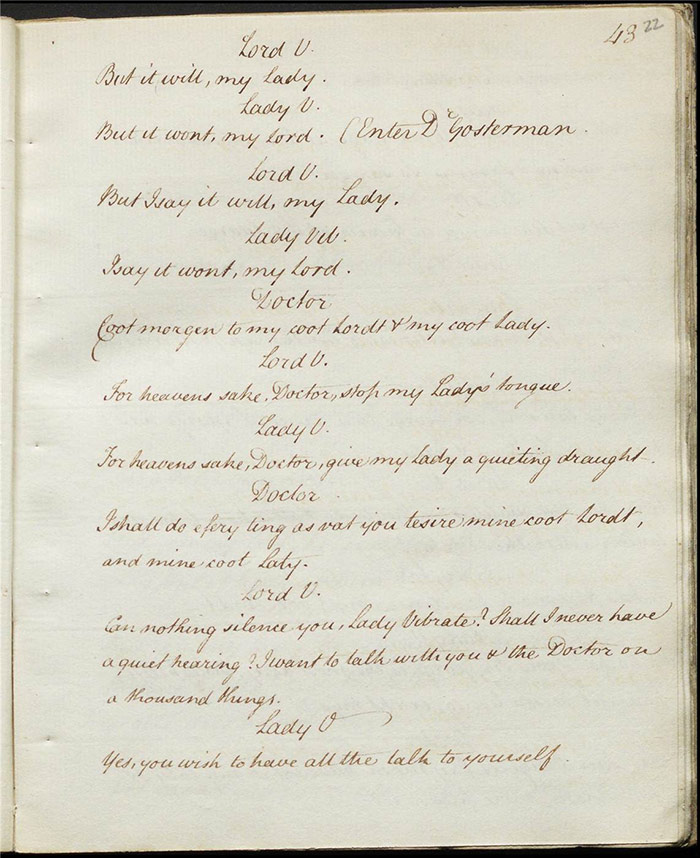

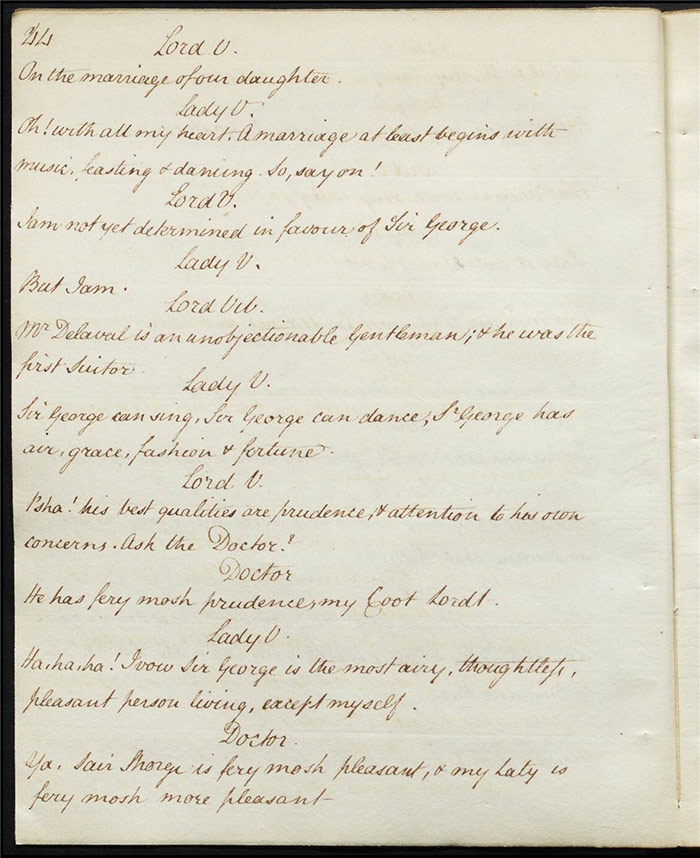

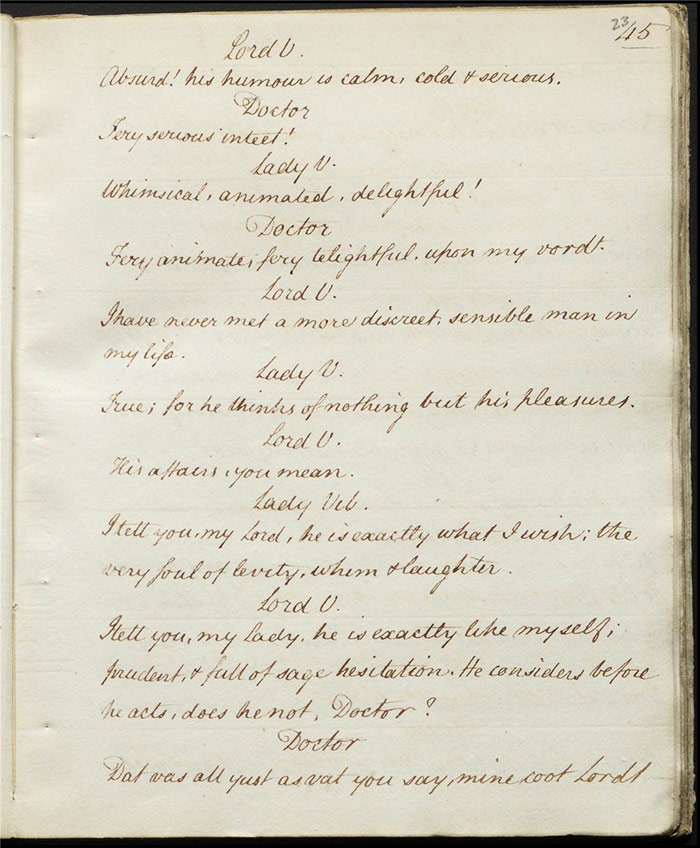

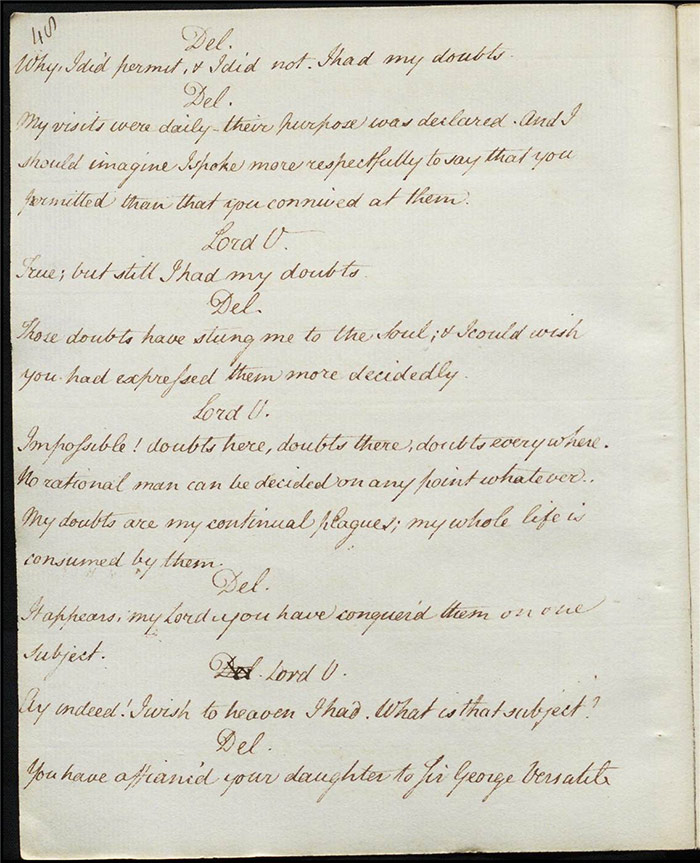

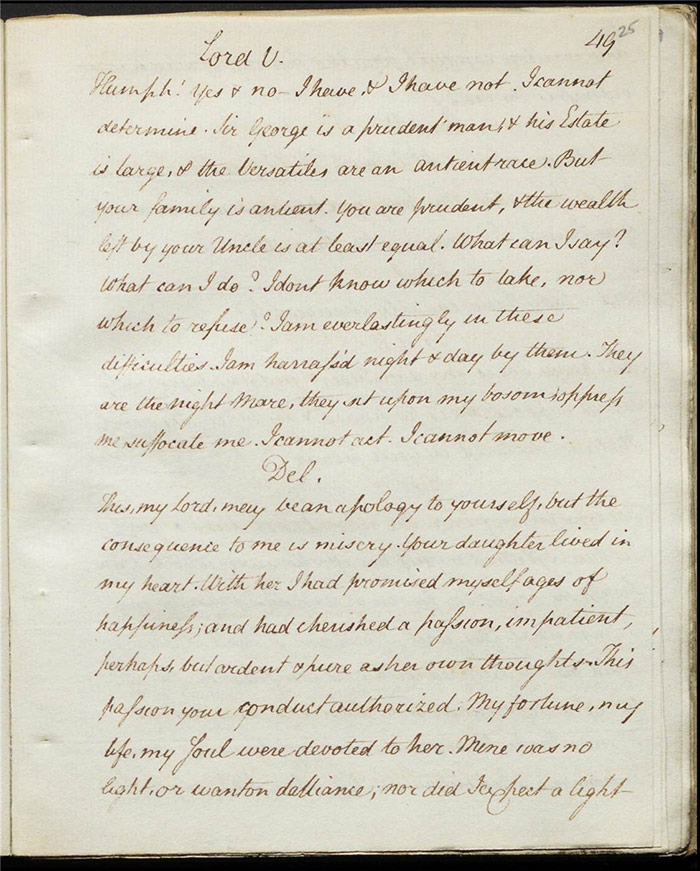

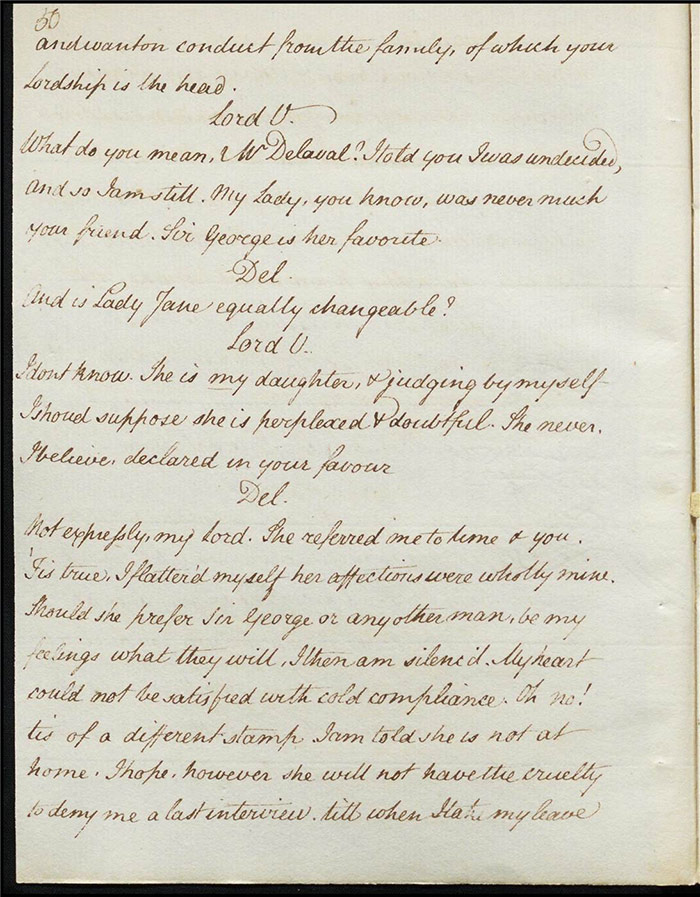

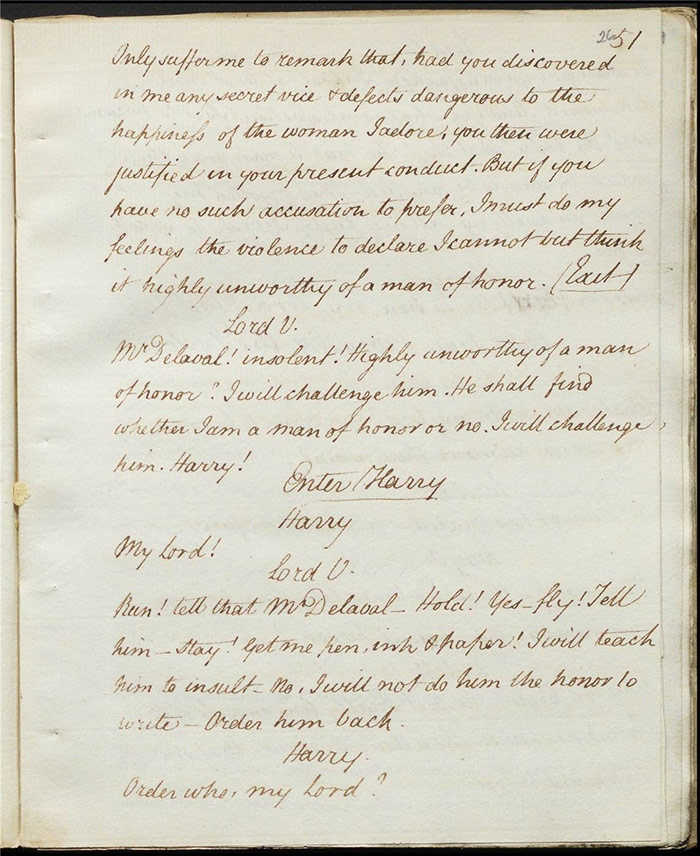

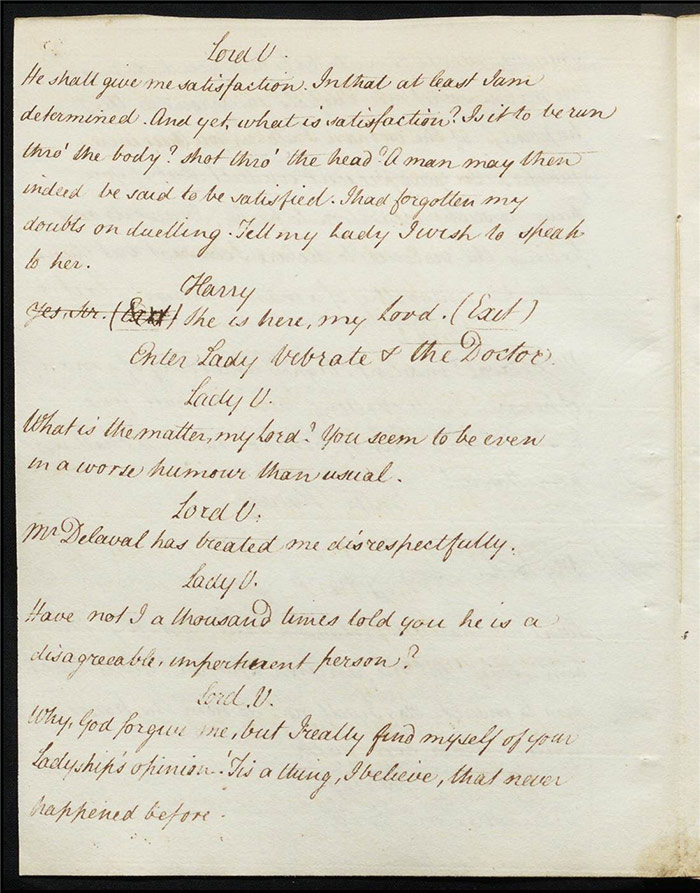

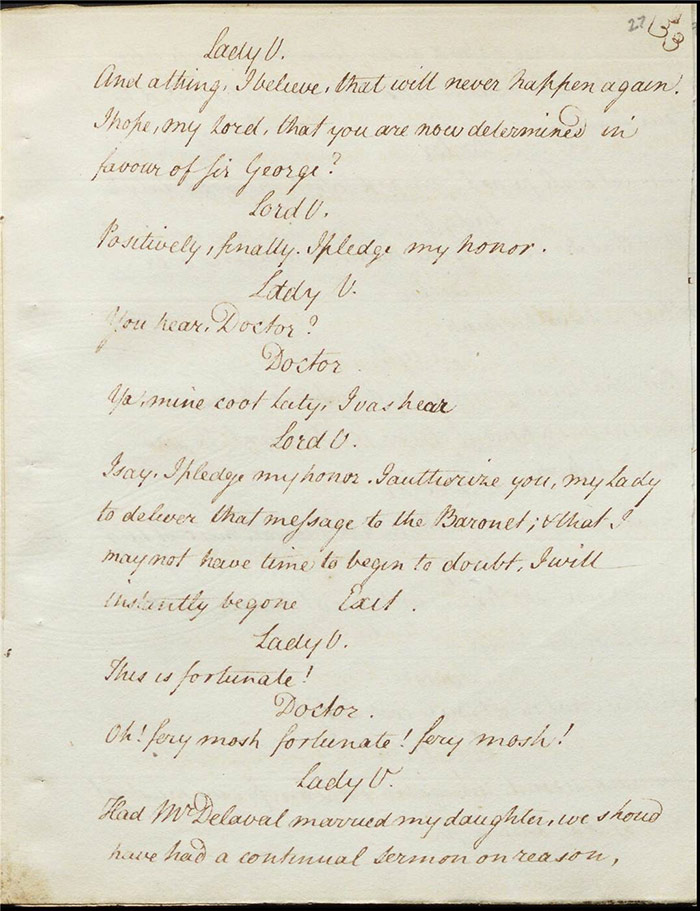

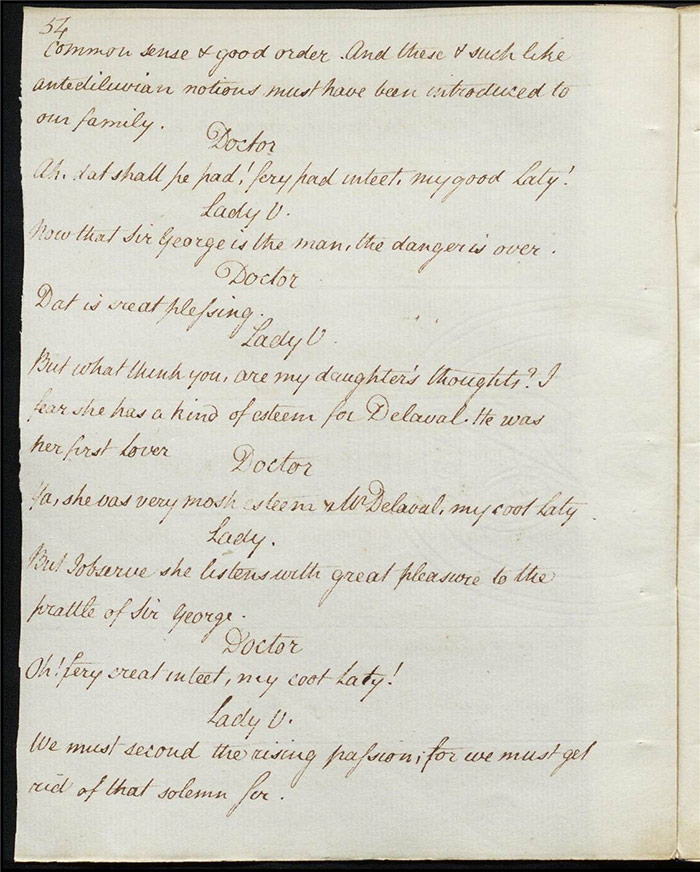

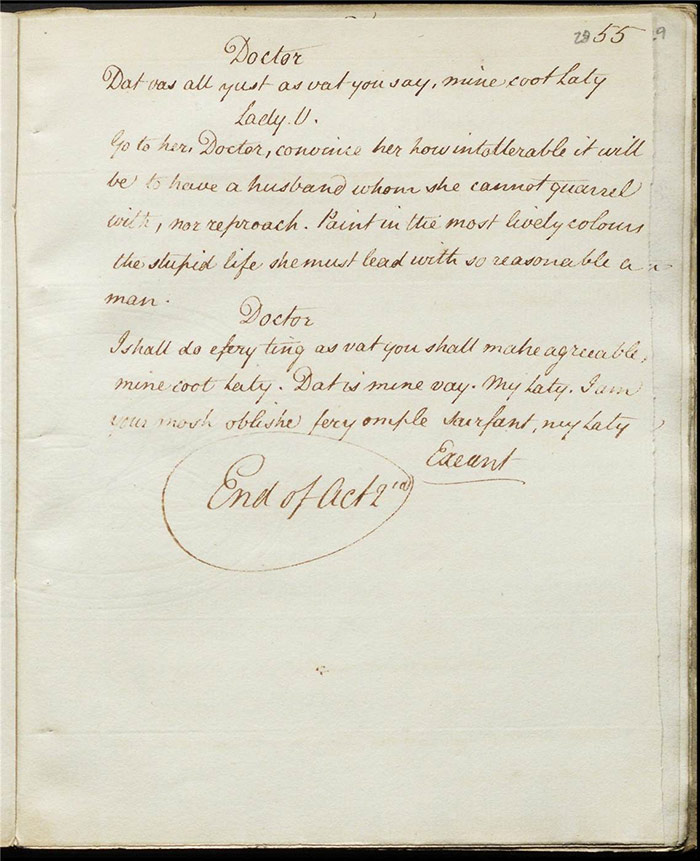

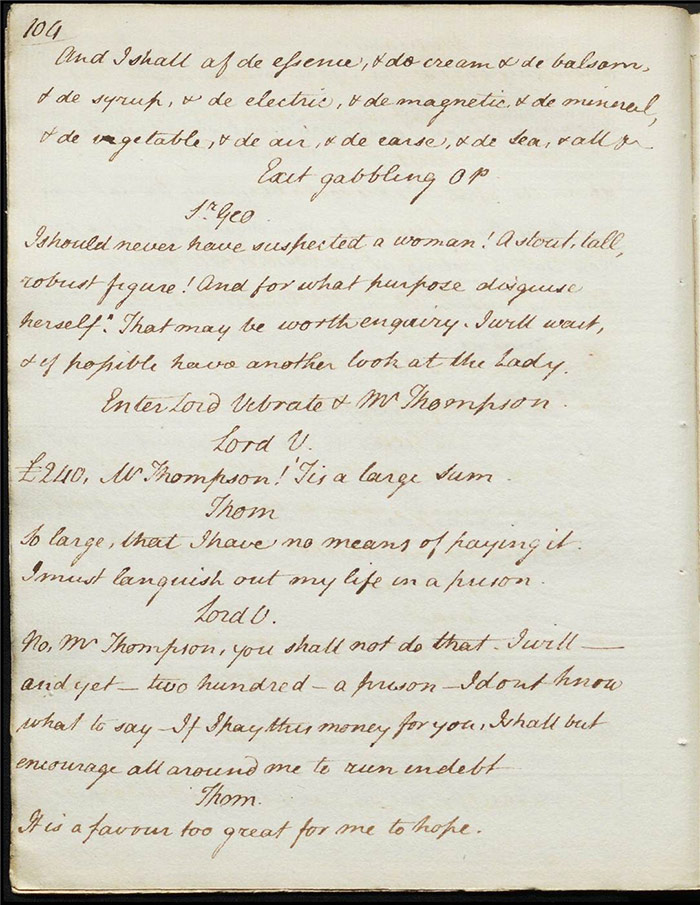

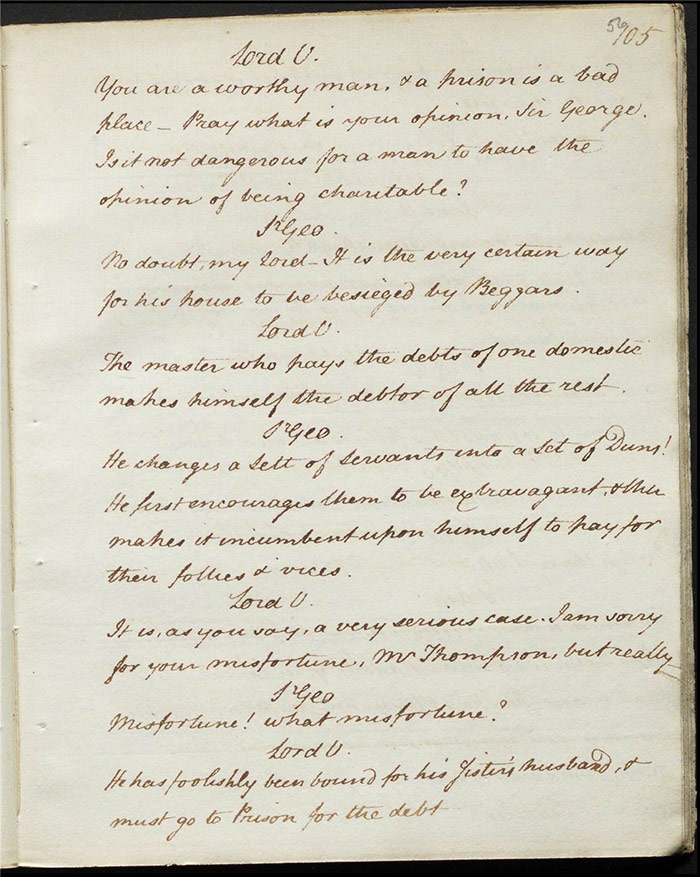

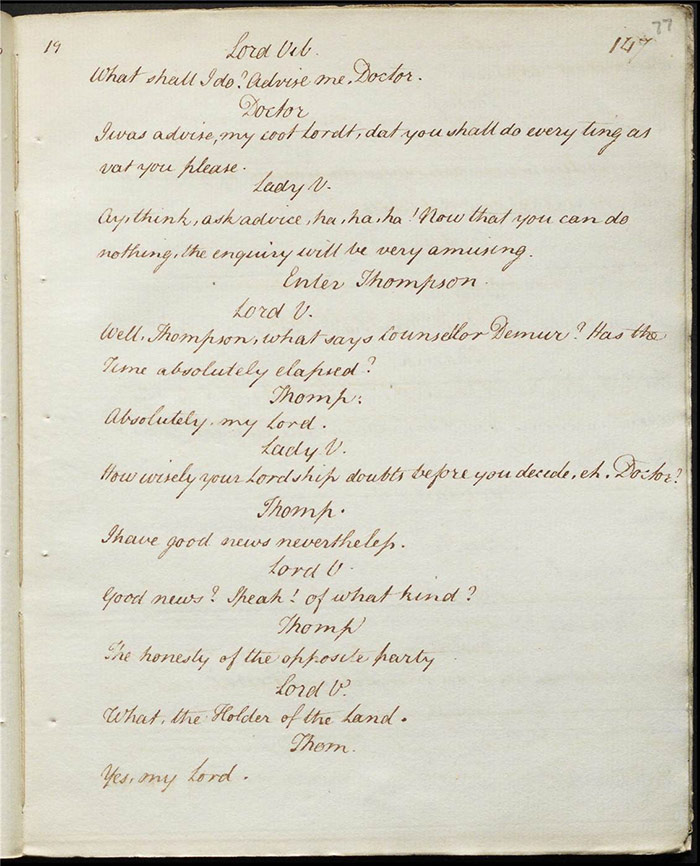

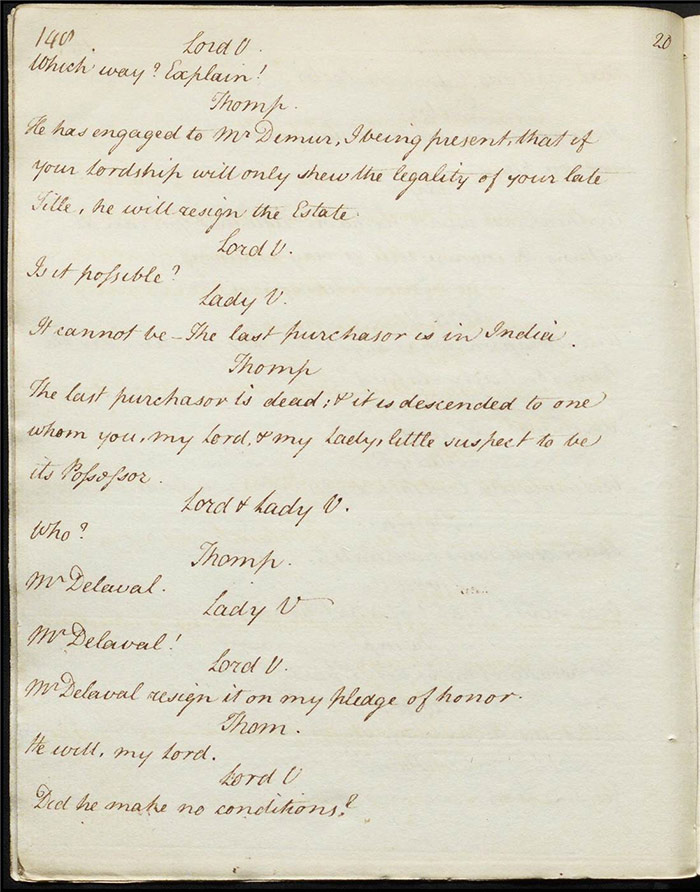

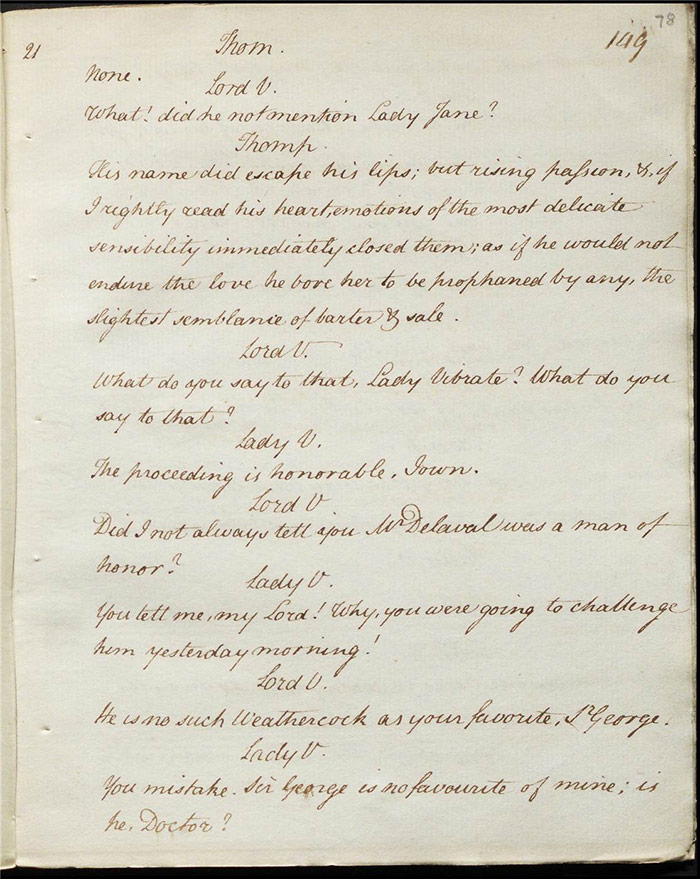

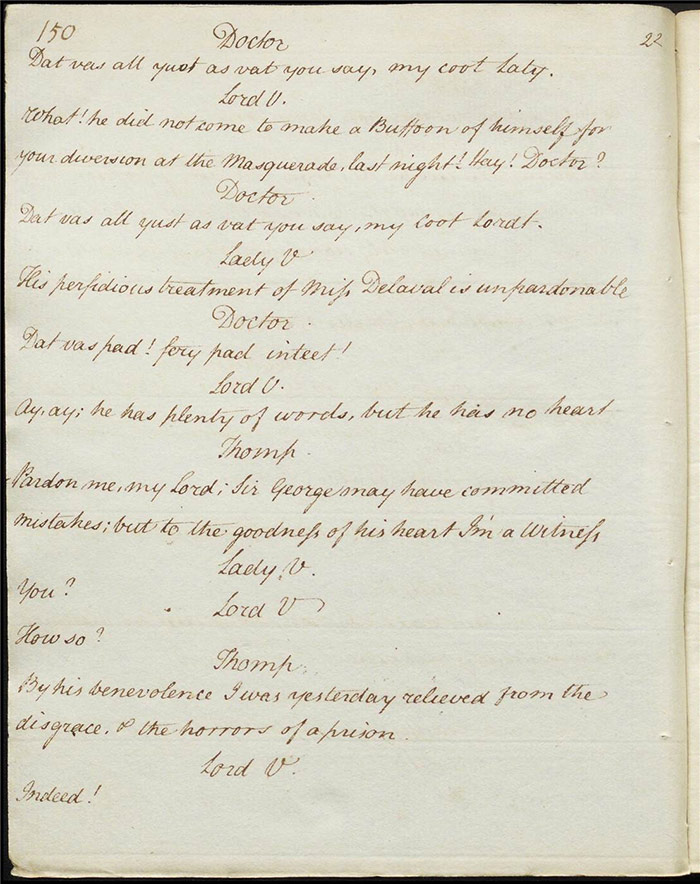

Lord Vibrate’s reading of sceptical philosophy at the opening of the second act indicates the kind of man he is (f.15v). Utterly unable to make a decision, his long-suffering servant Thompson listens patiently to a string of inchoate instructions. Some of Vibrate’s concerns are related to a potential claim on a property he is considering, an issue which he also discusses with his wife when she enters. Despite his eventual determination to pursue the suit for the sake of his daughter’s fortune, she is dubious that he will follow through. The couple then debate the merits of their daughter’s suitors with Lady Vibrate favouring Sir George and Vibrate taking the side of Delaval. Delaval presents his complaints to Vibrate who flusters that he cannot decide between him and Sir George for his daughter. Highly insulted at Delaval’s subsequent forthright contempt, Lord Vibrate informs his wife that he has changed his mind again and that Jane should marry Sir George. She asks Doctor Gosterman, who has witnessed much of these discussions, to make the case for Sir George to Jane.

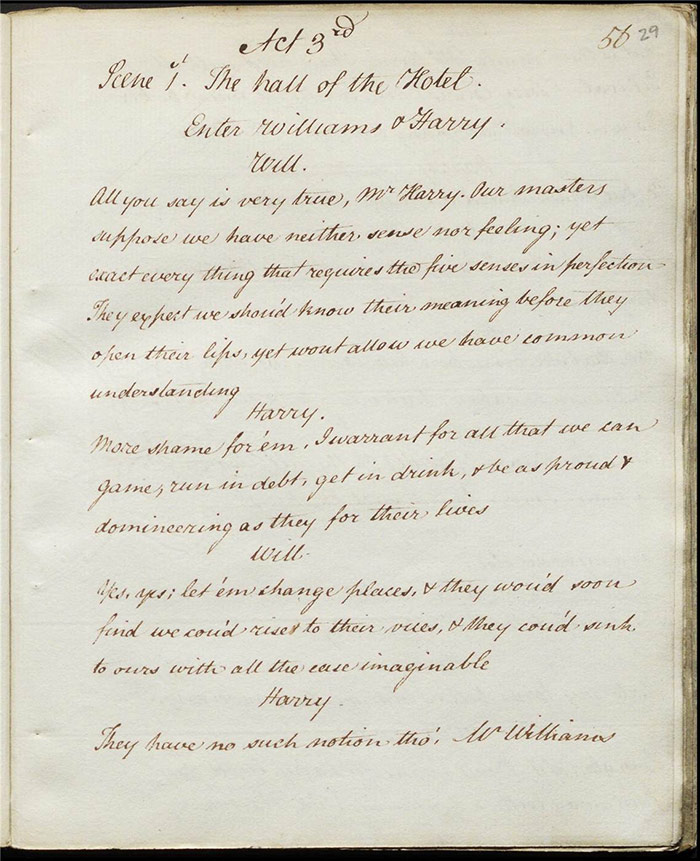

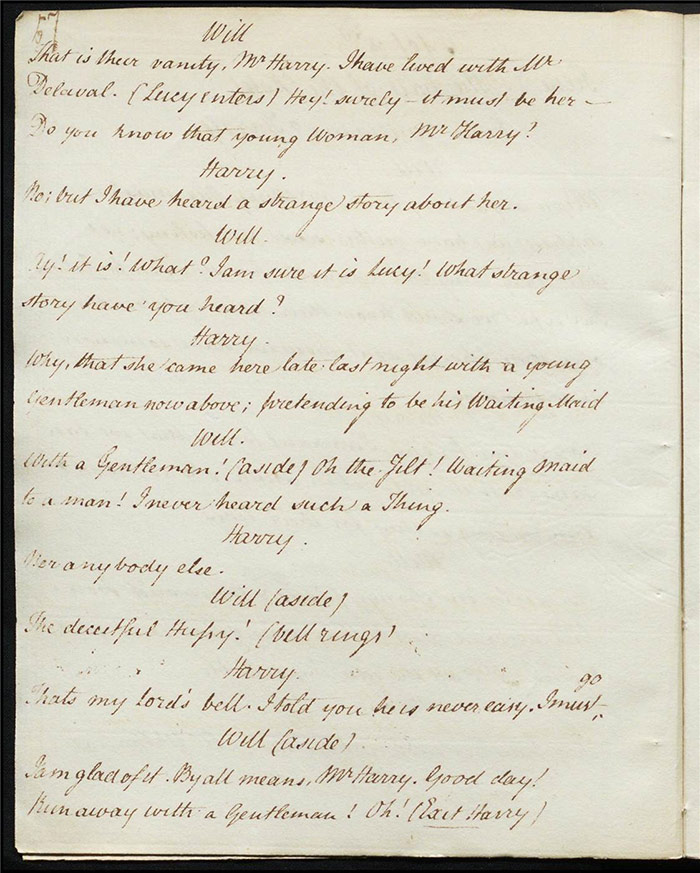

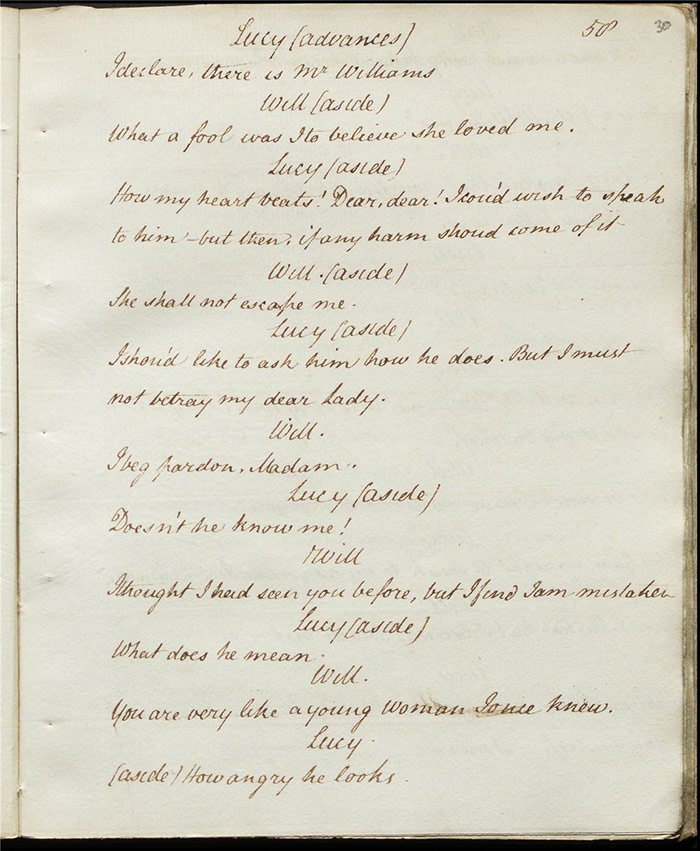

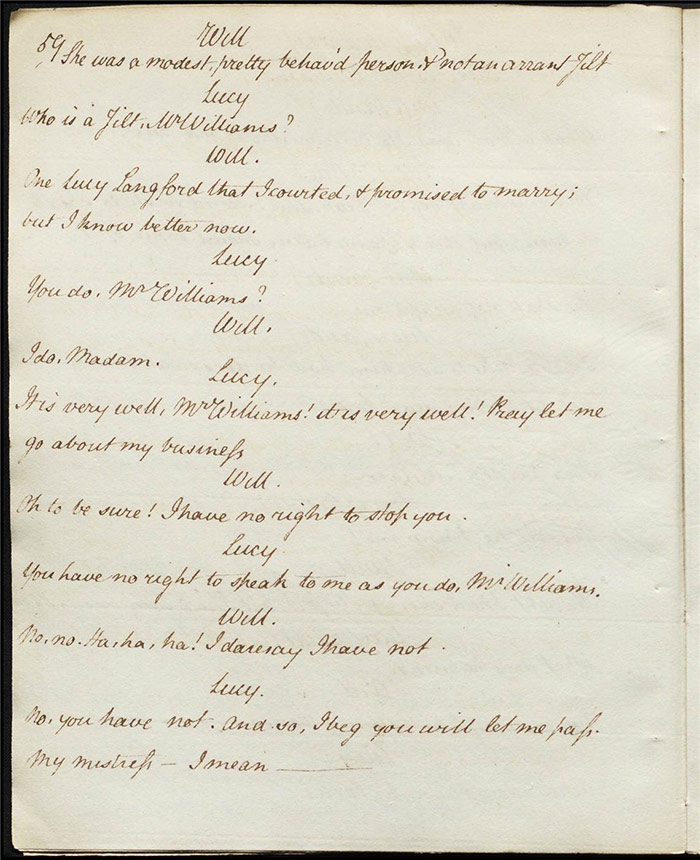

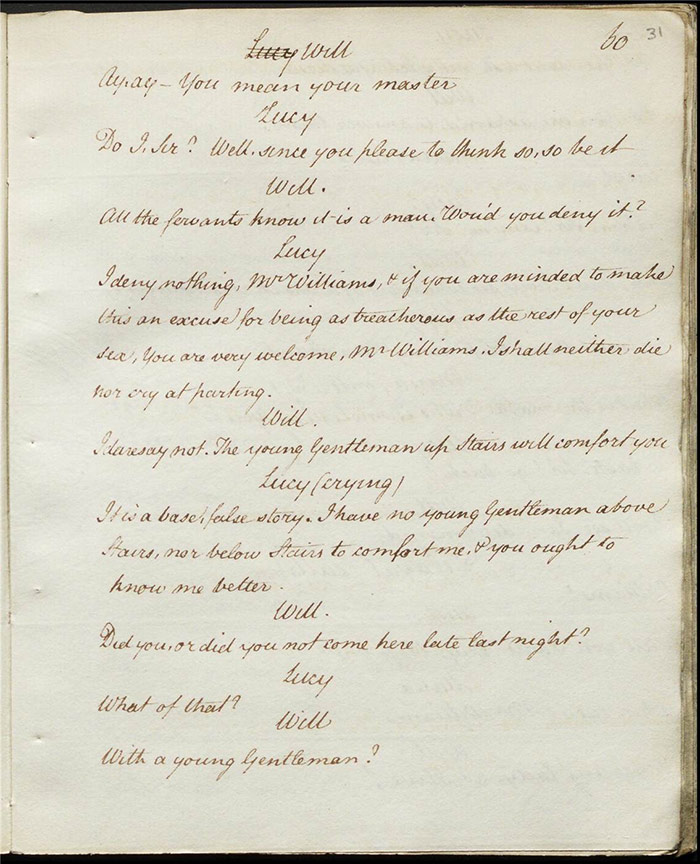

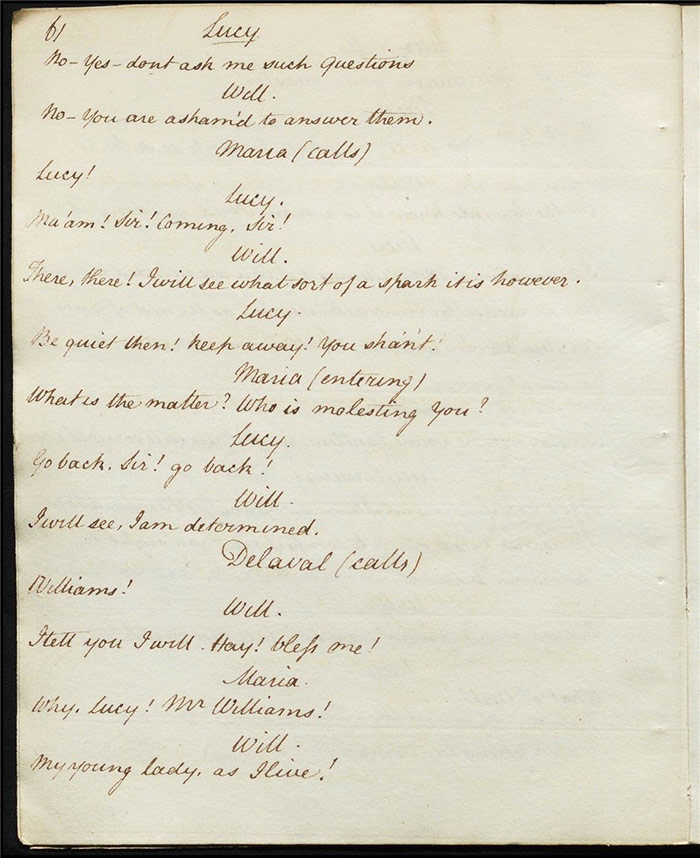

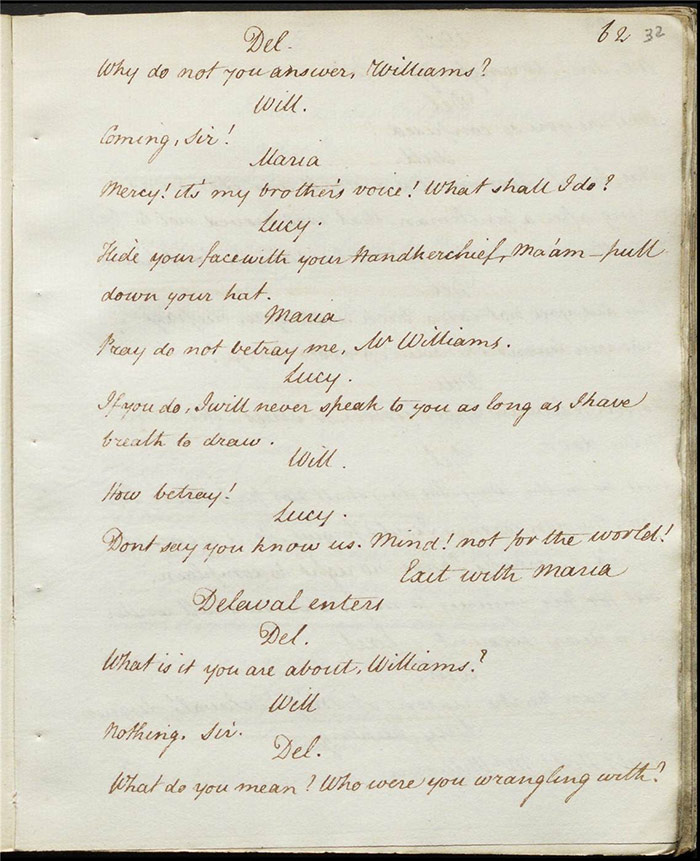

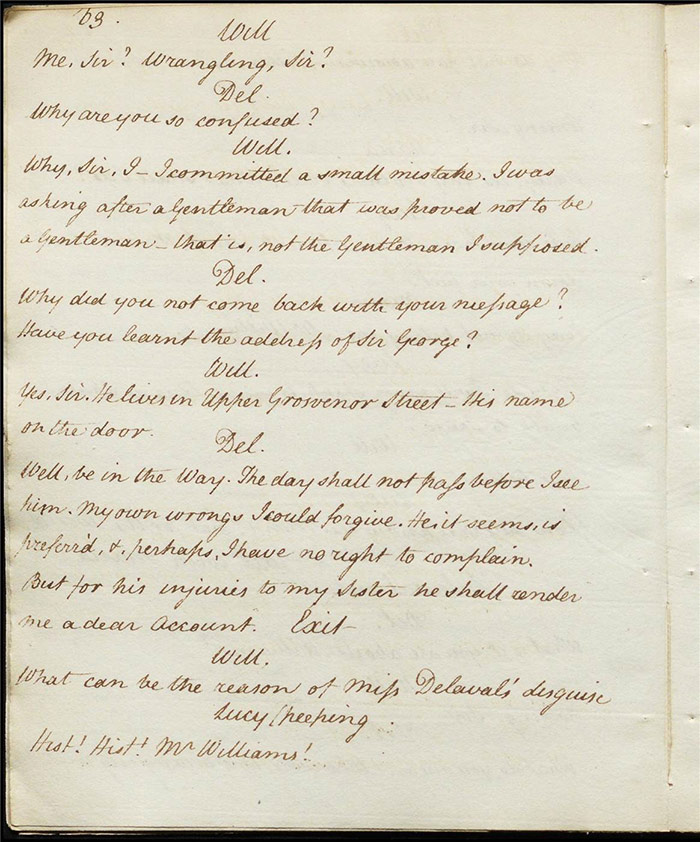

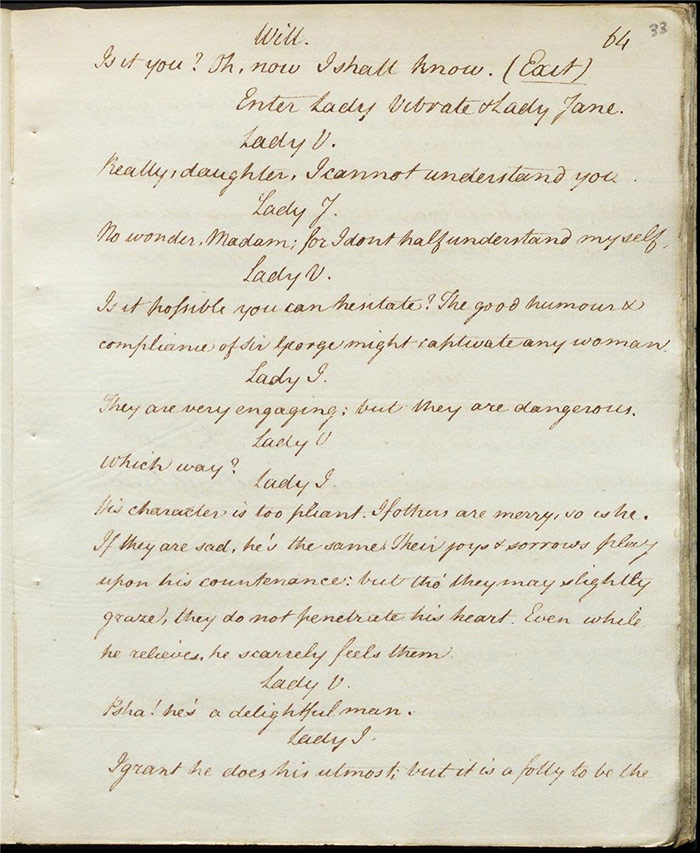

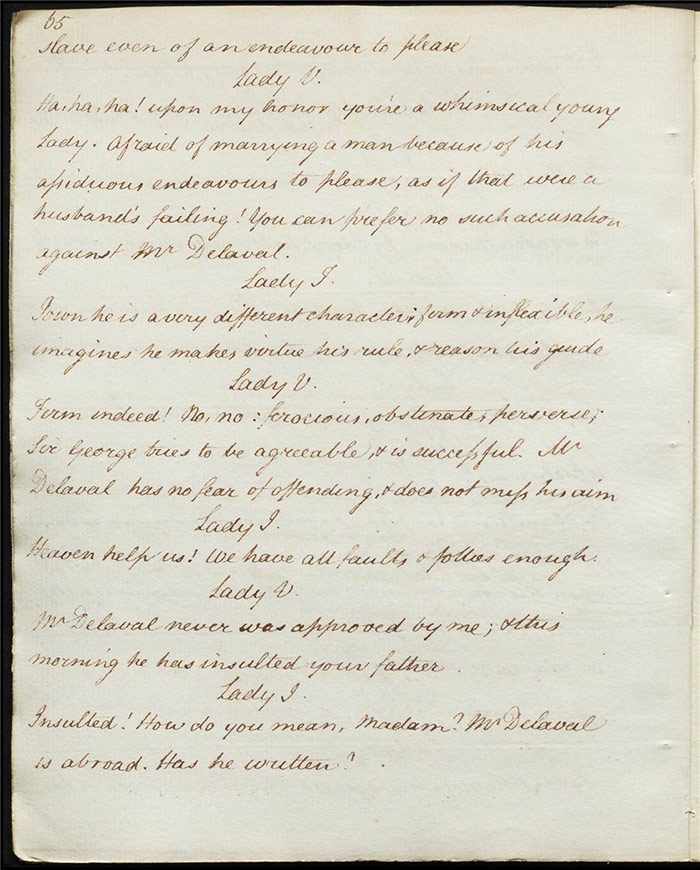

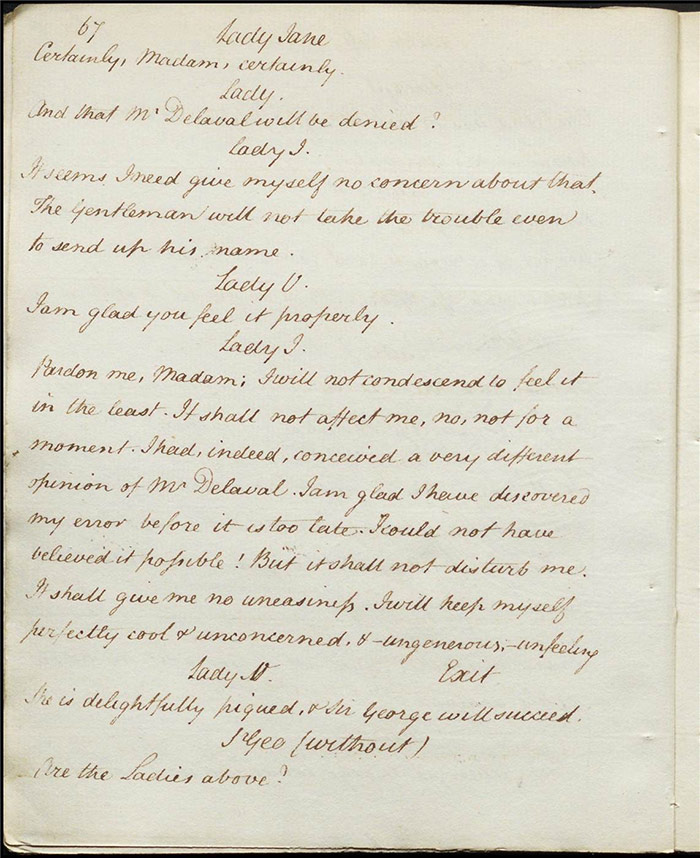

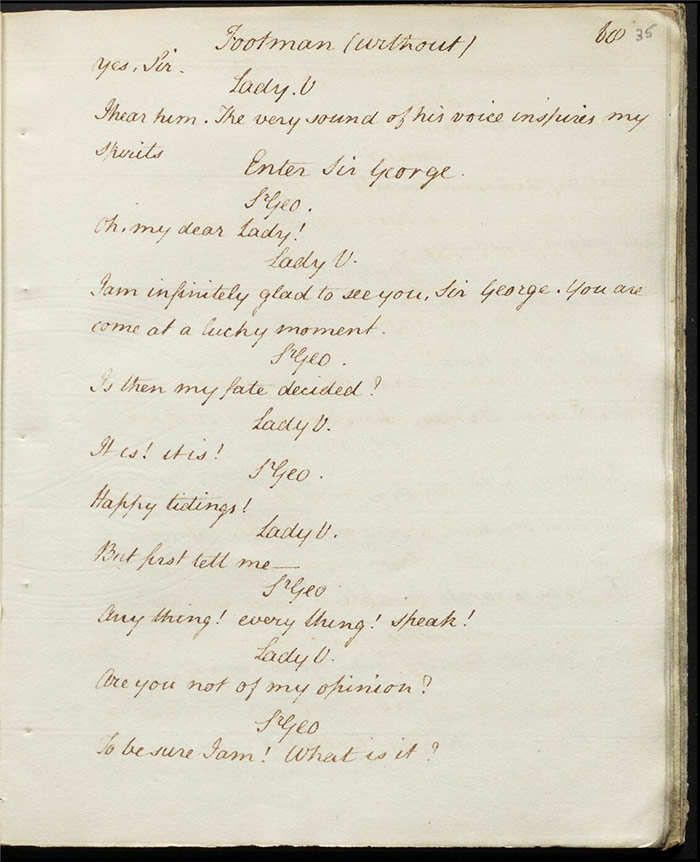

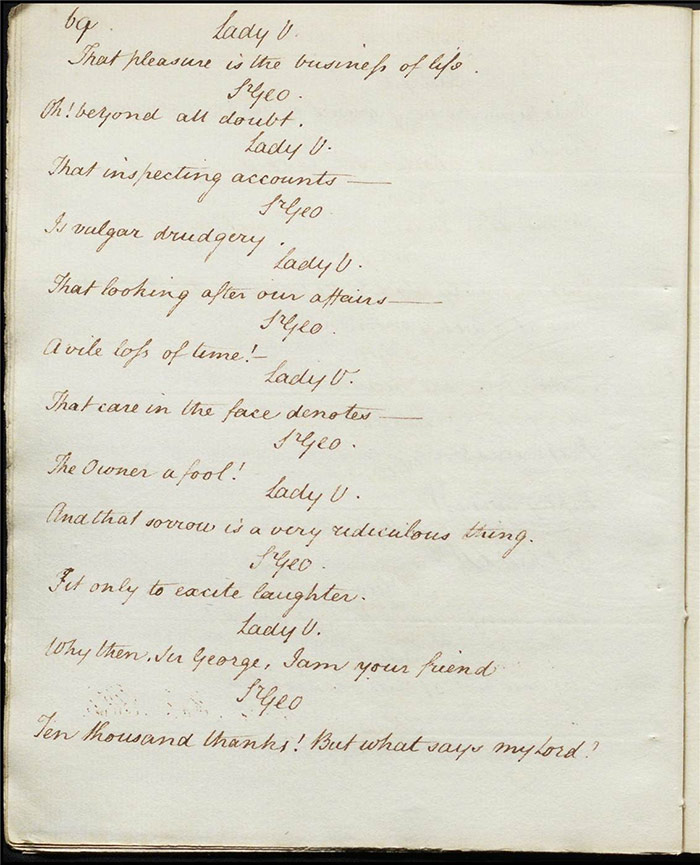

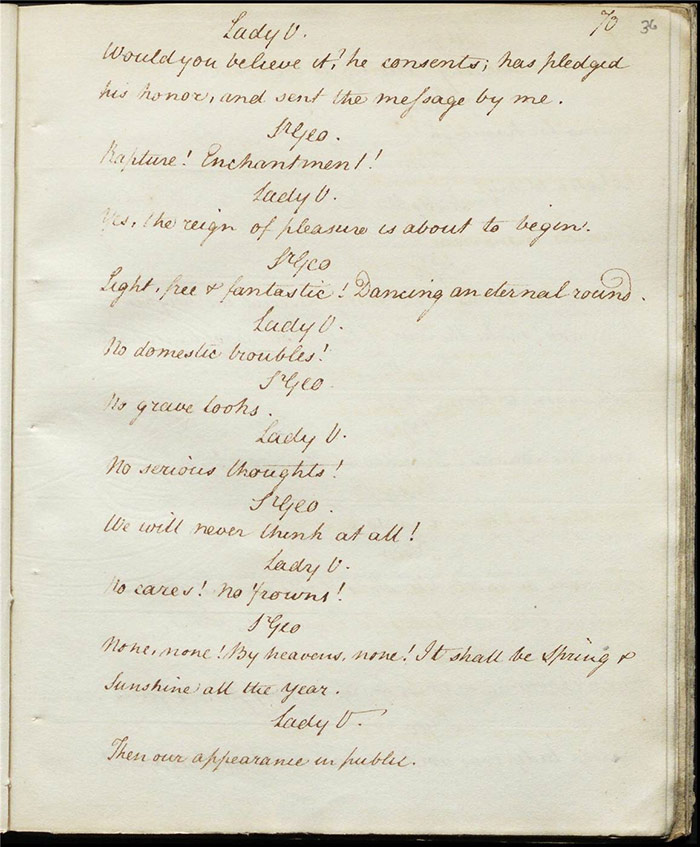

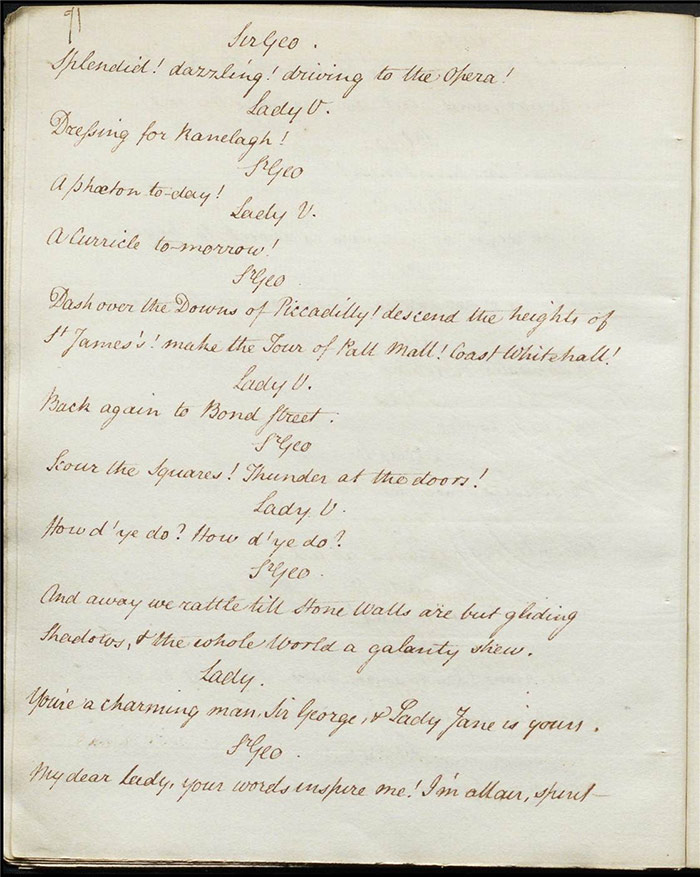

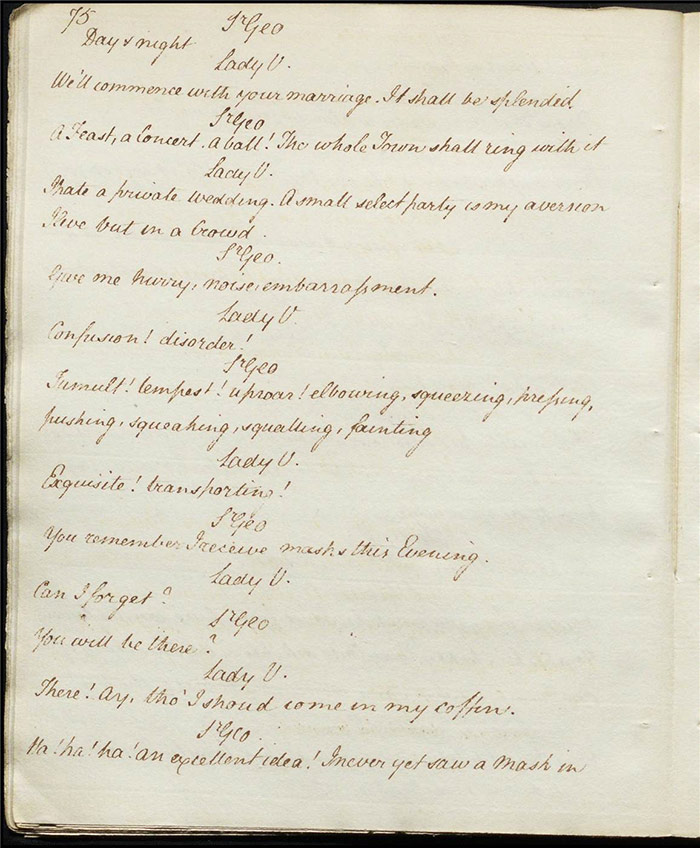

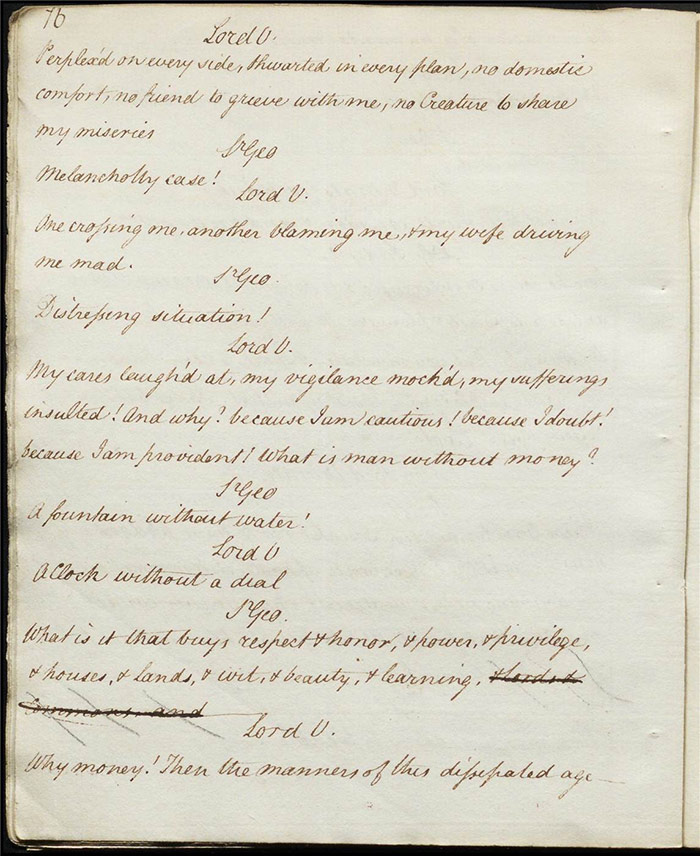

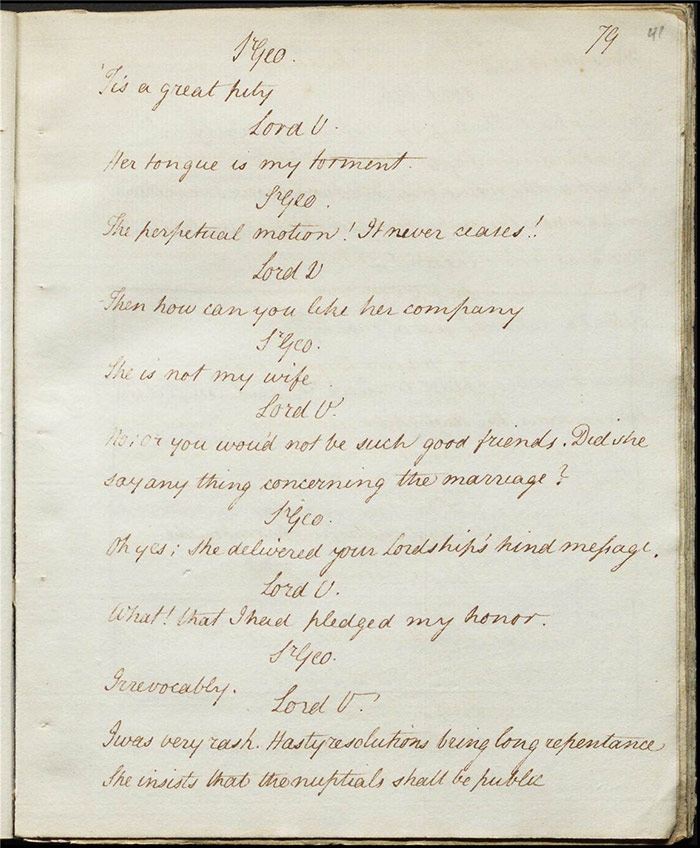

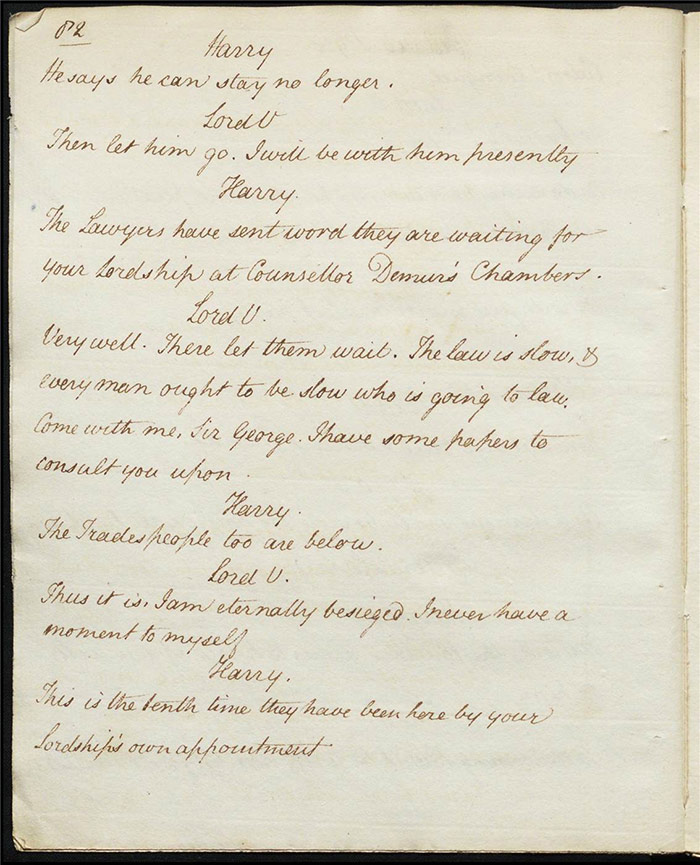

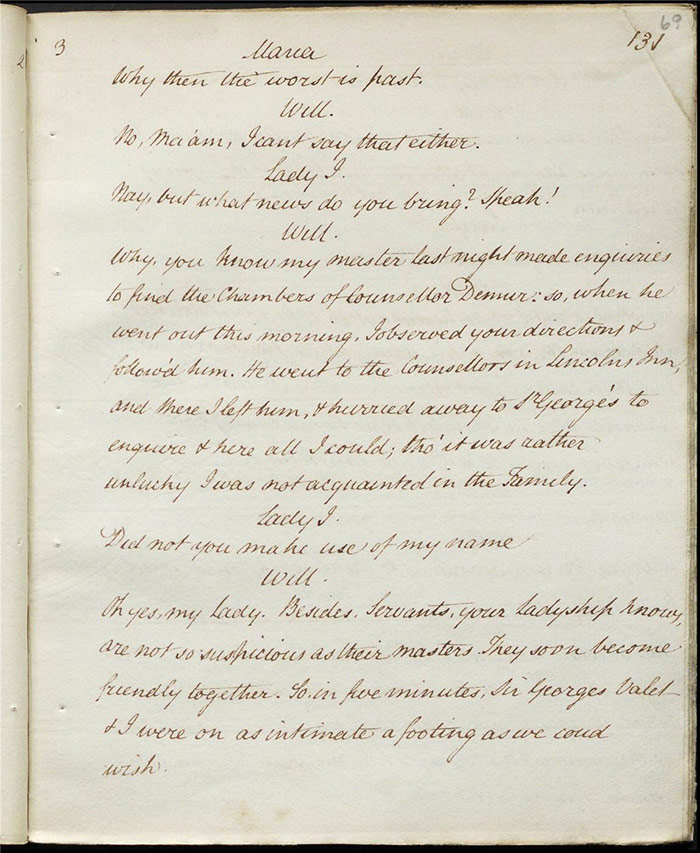

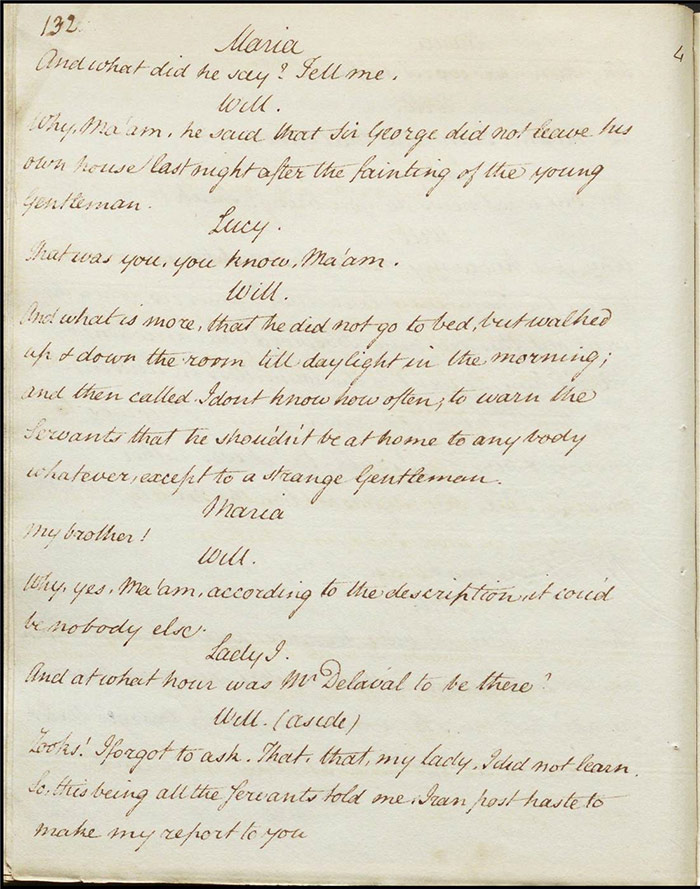

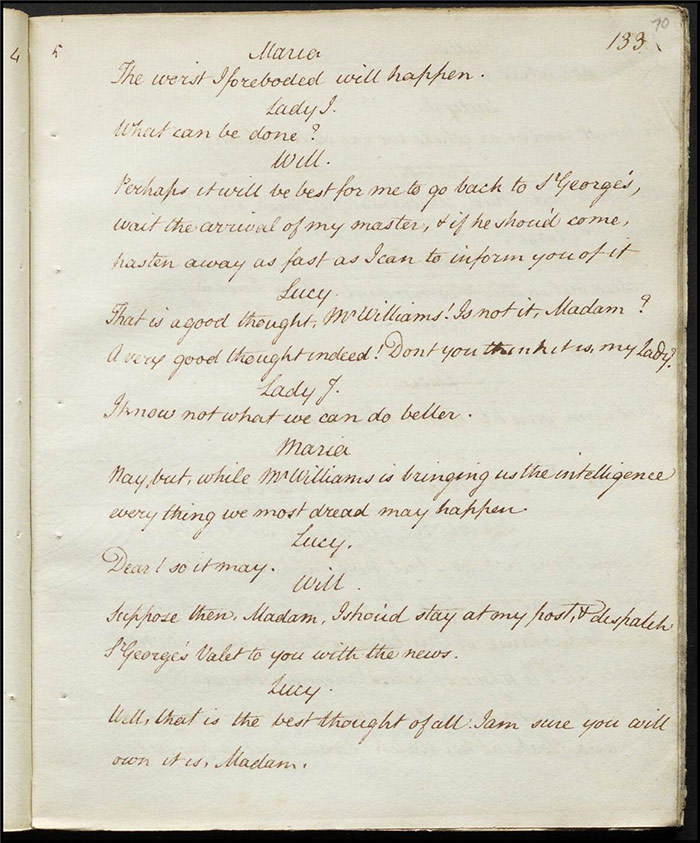

When the third act opens, Williams, servant to Delaval, is incensed when he hears that his lover Lucy is apparently staying with a man (f.29r). He confronts her angrily but, determined to protect her mistress, she does not deny the charge. Maria appears and he recognizes her but she asks him to preserve her anonymity. Lady Vibrate tries to convince Lady Jane to marry Sir George; Lady Jane favoured Delaval but is indignant to hear that he is in the inn but has not made himself known to her. Lady Vibrate reveals her plans for a public extravaganza of a wedding to Sir George who concurs with every sentiment; after she leaves, he then proceeds to agree with Lord Vibrate who wants the precise opposite to his wife. Lord Vibrate is told a court is sitting waiting for his presence but he cannot decide whether to go and pursue the case or not.

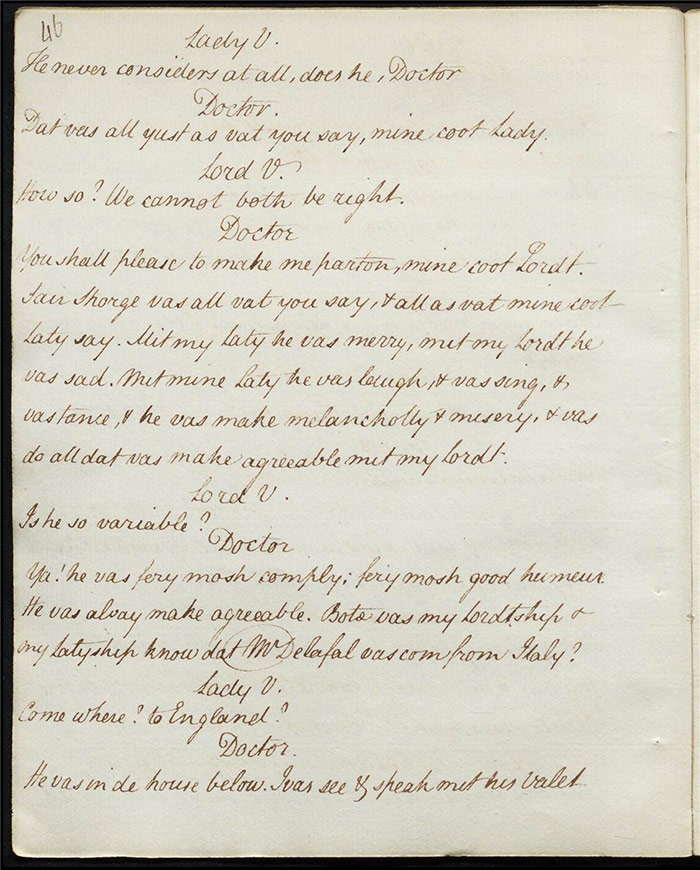

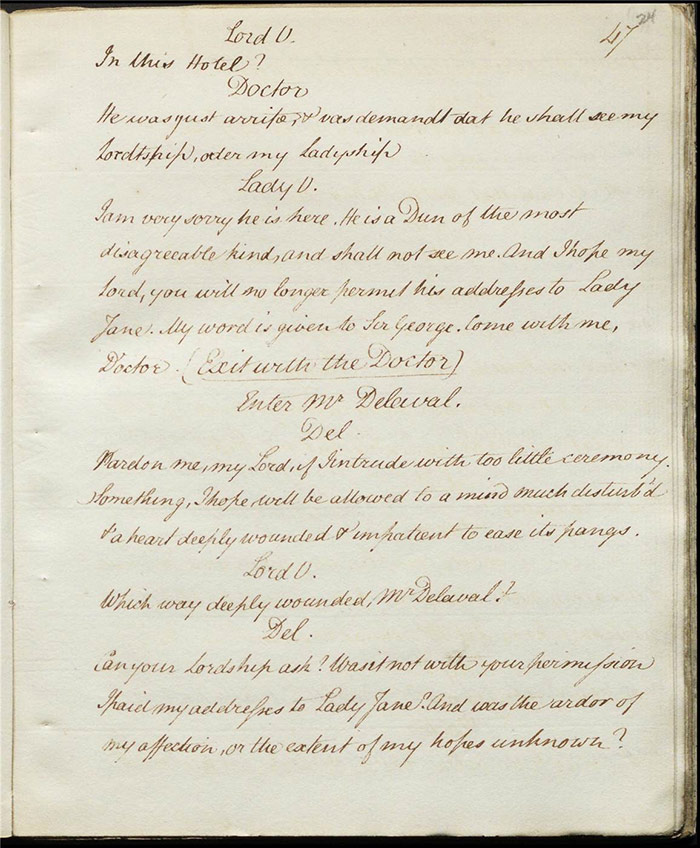

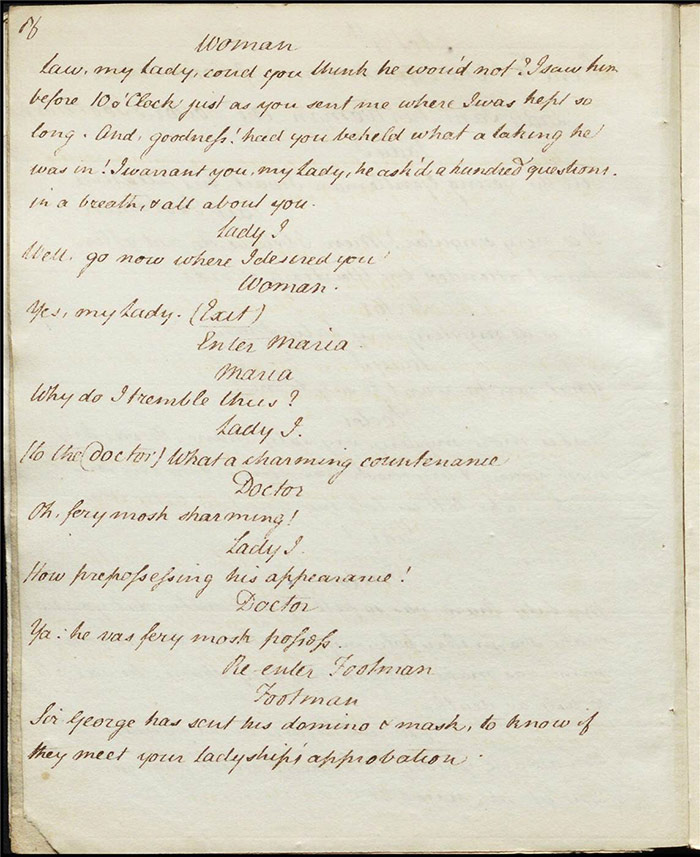

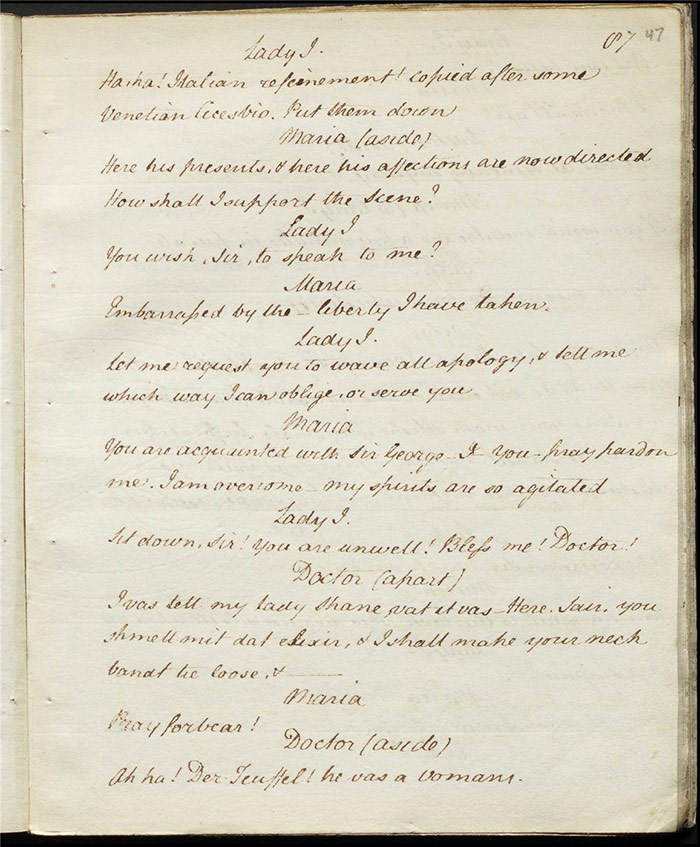

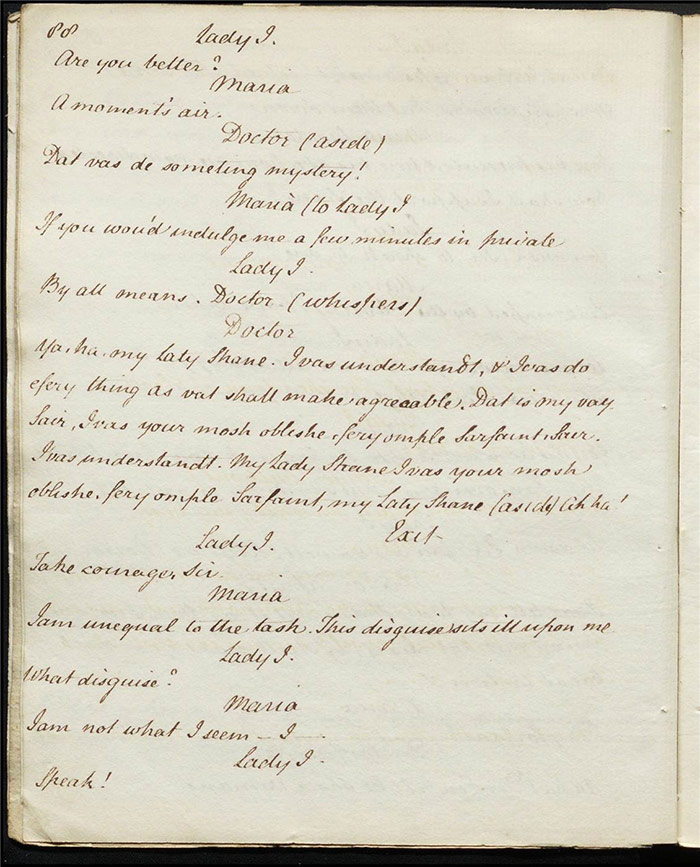

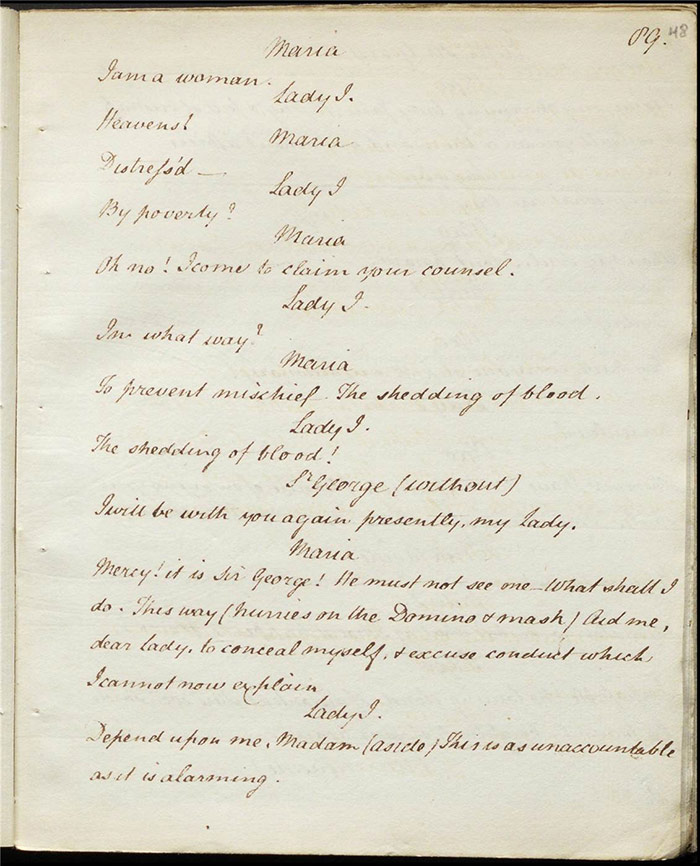

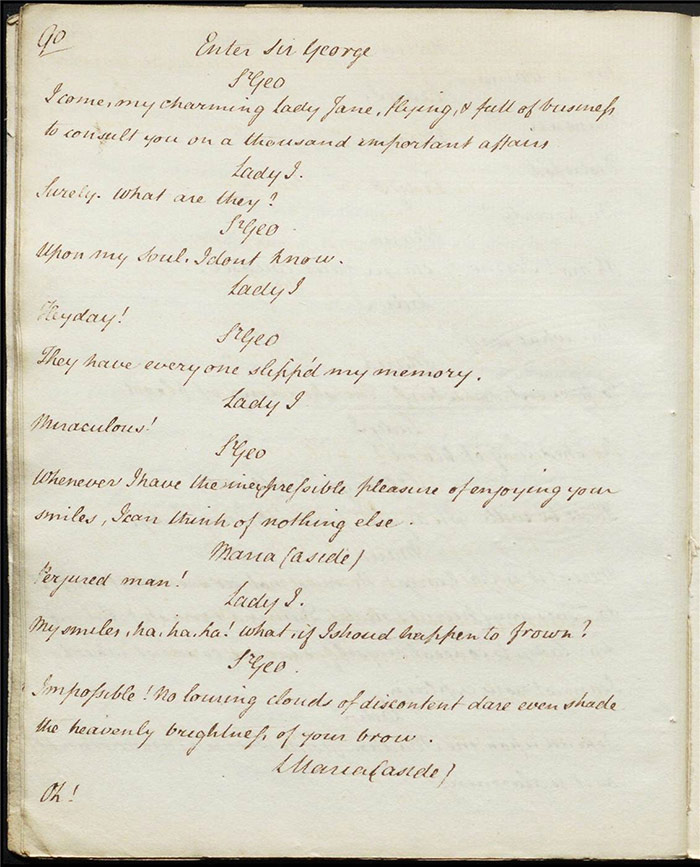

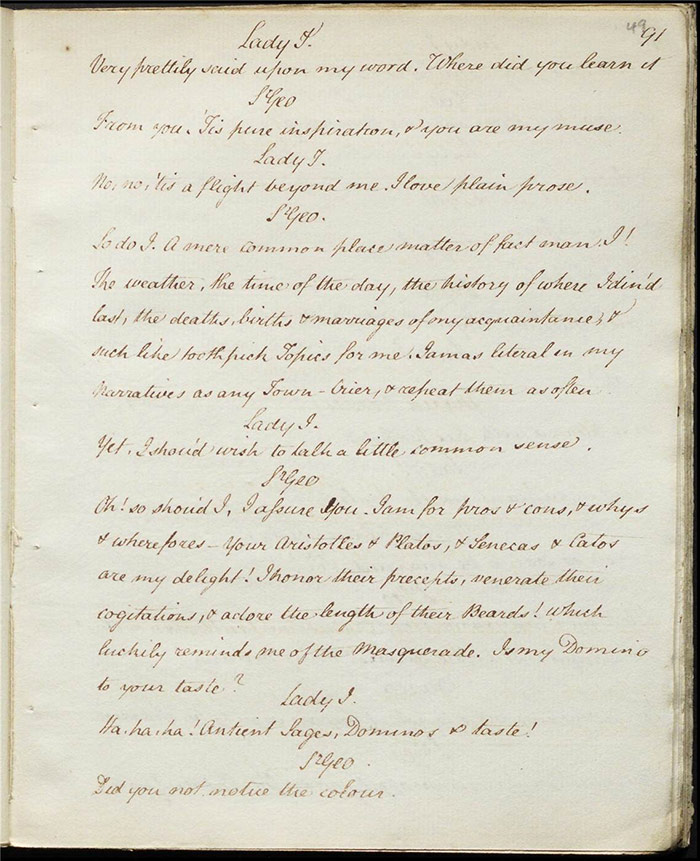

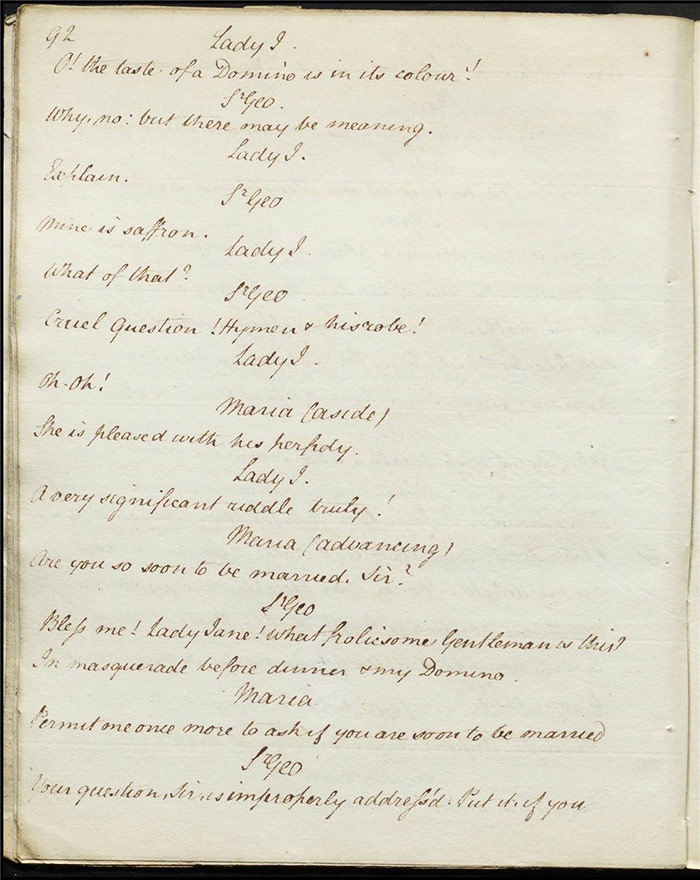

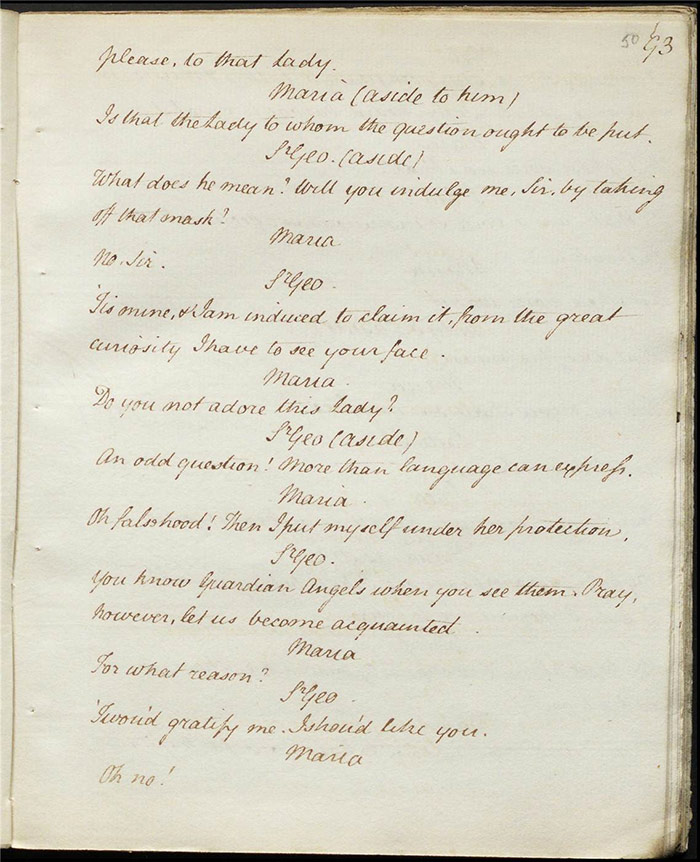

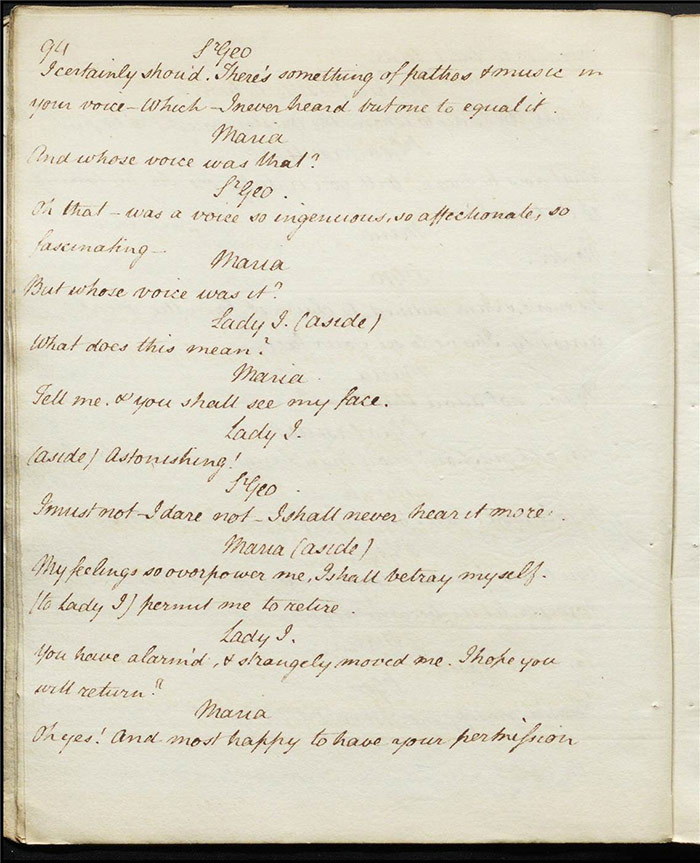

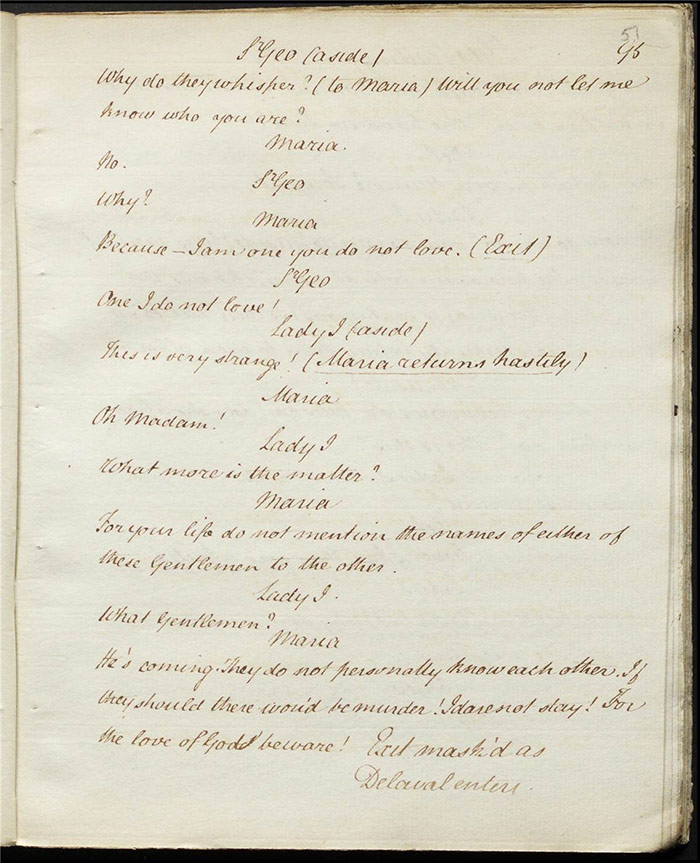

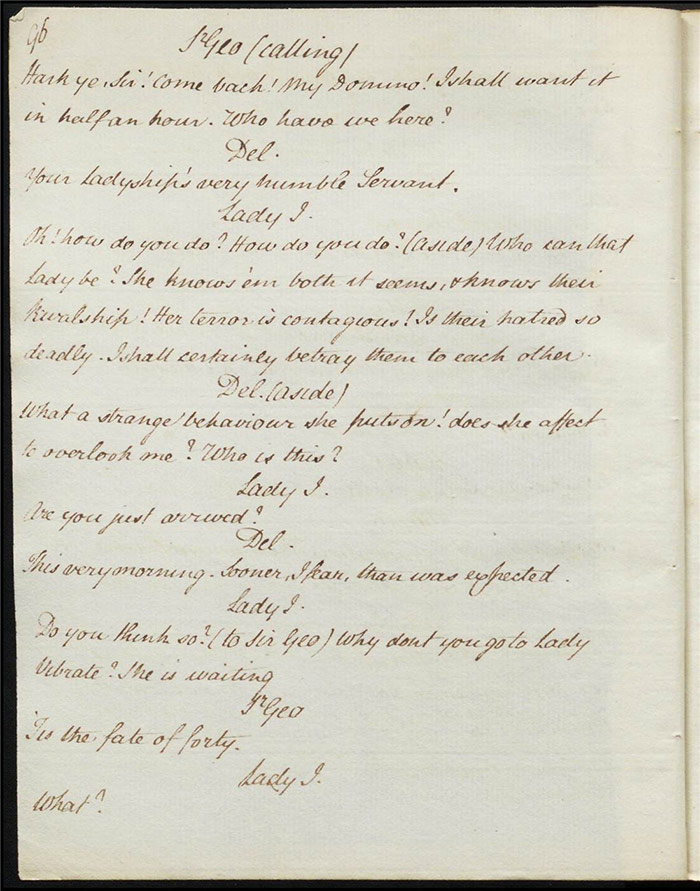

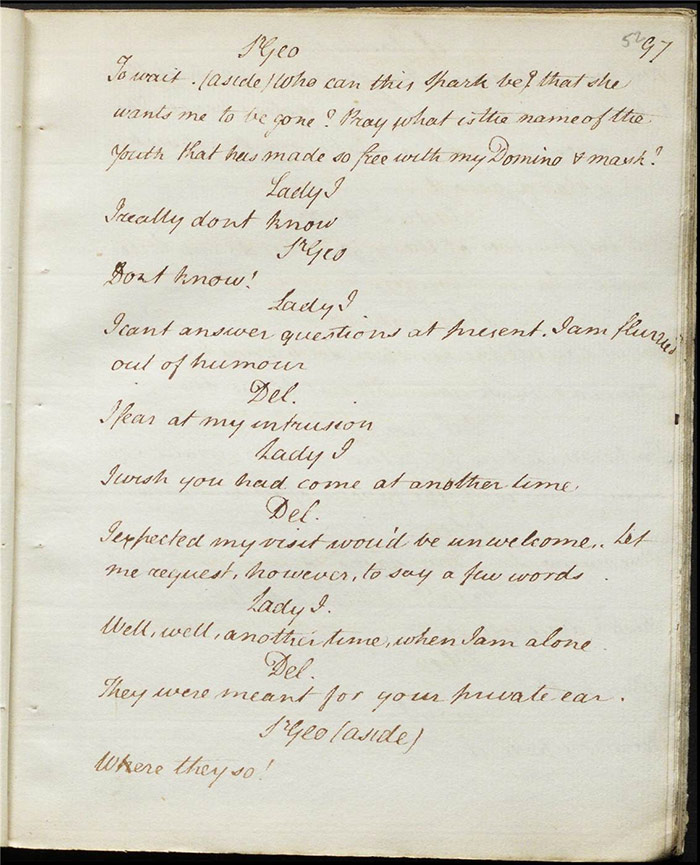

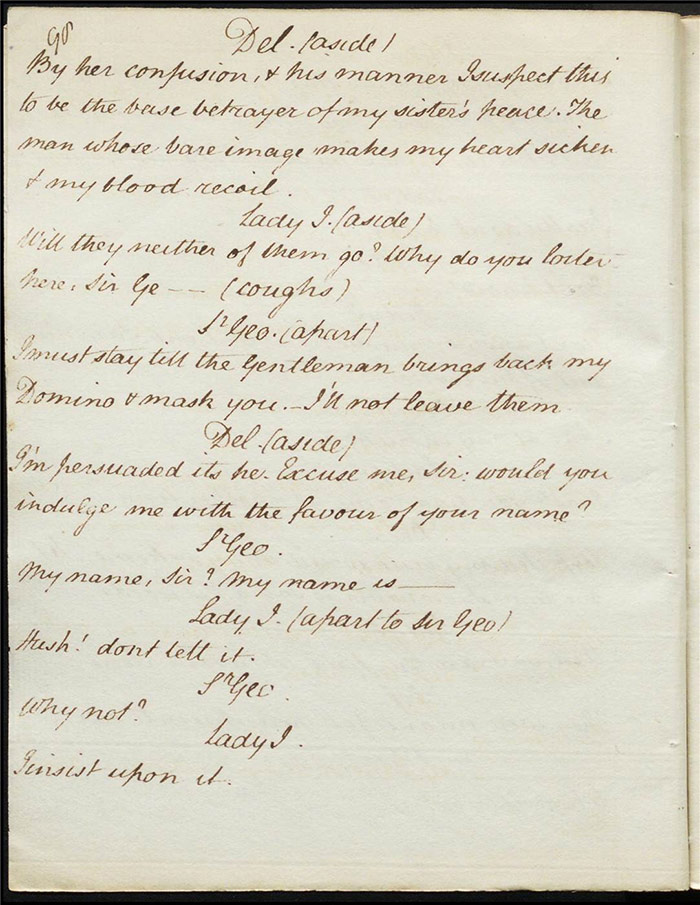

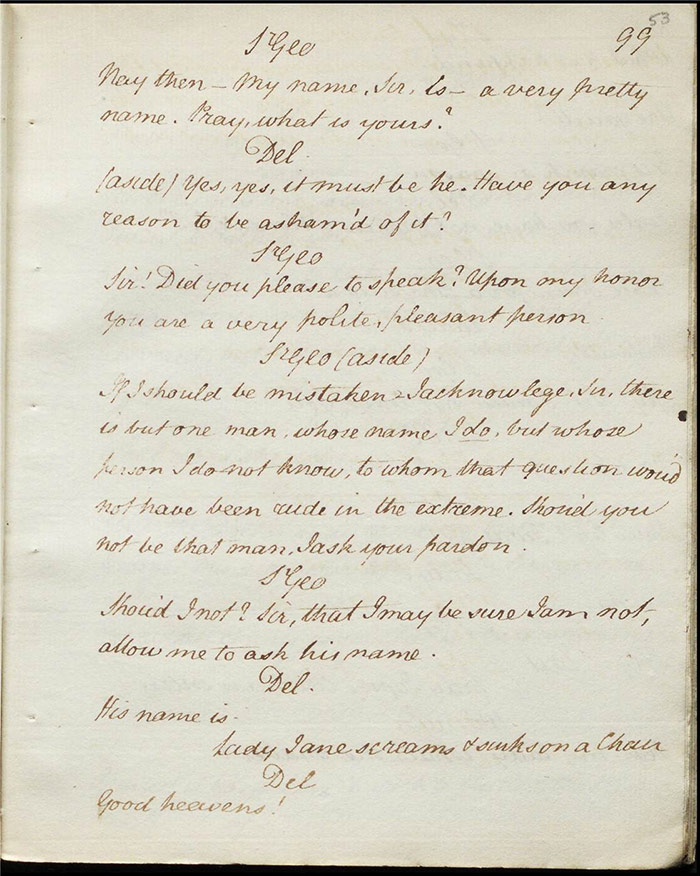

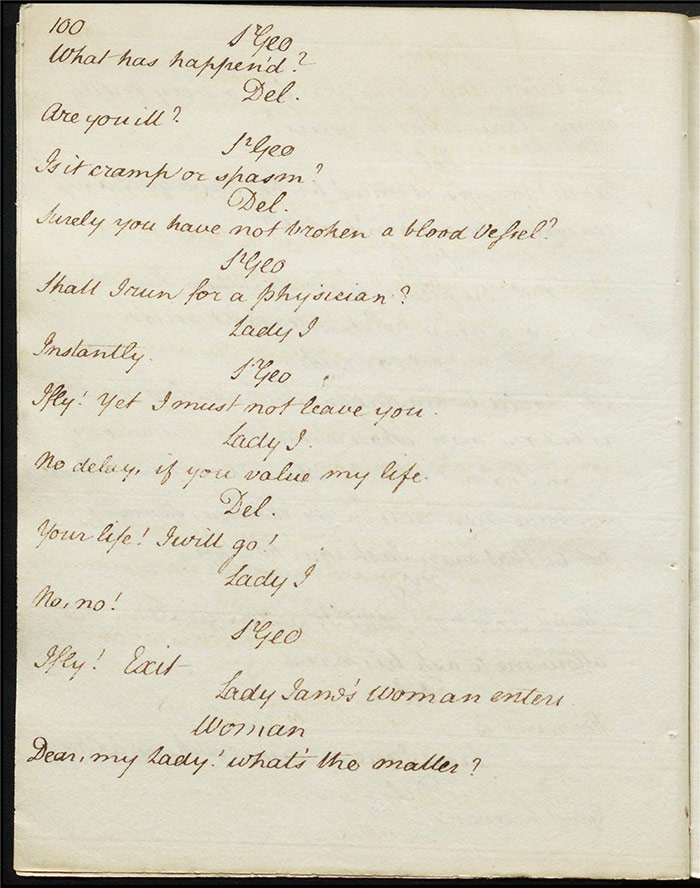

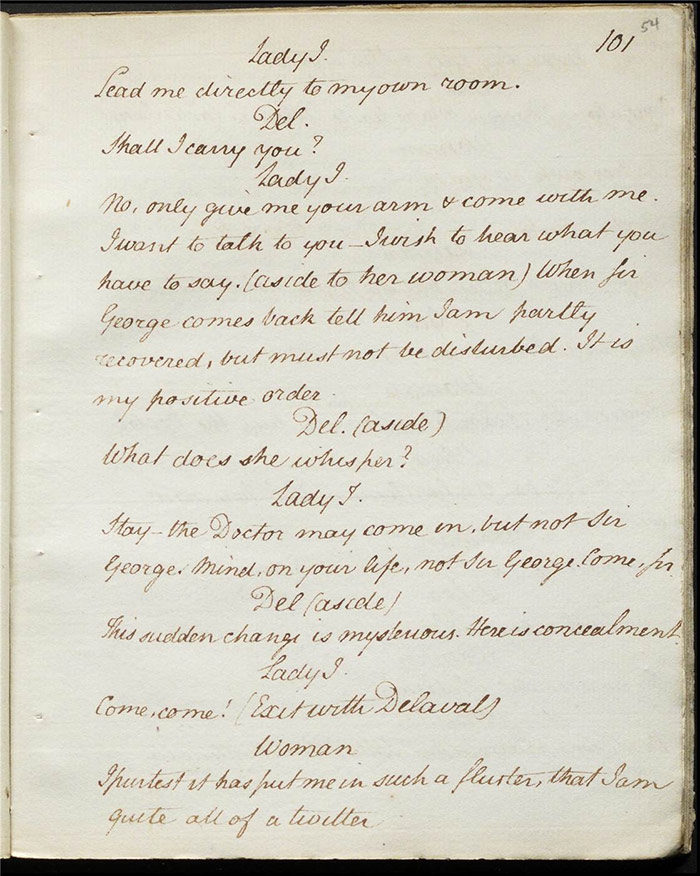

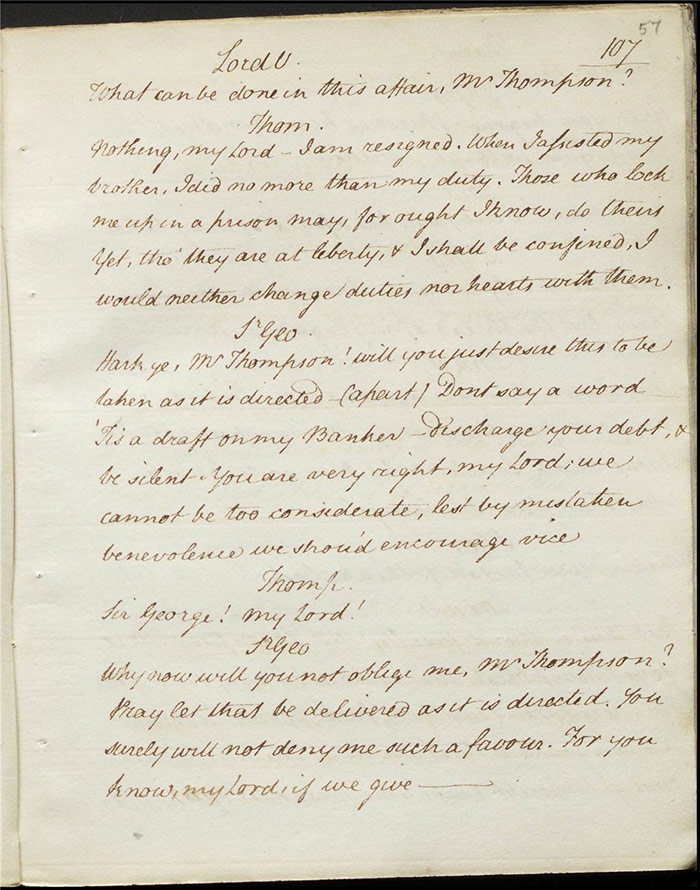

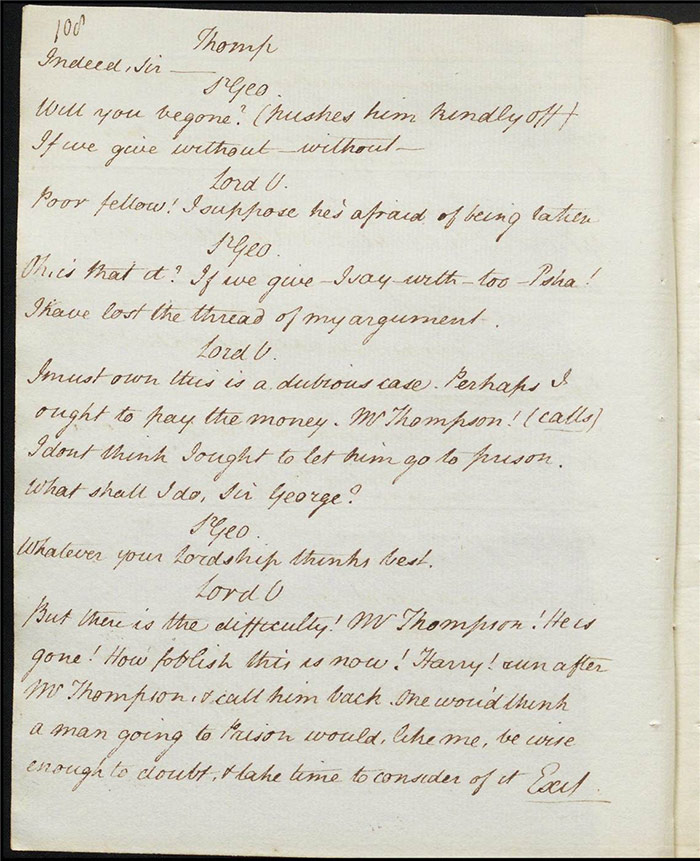

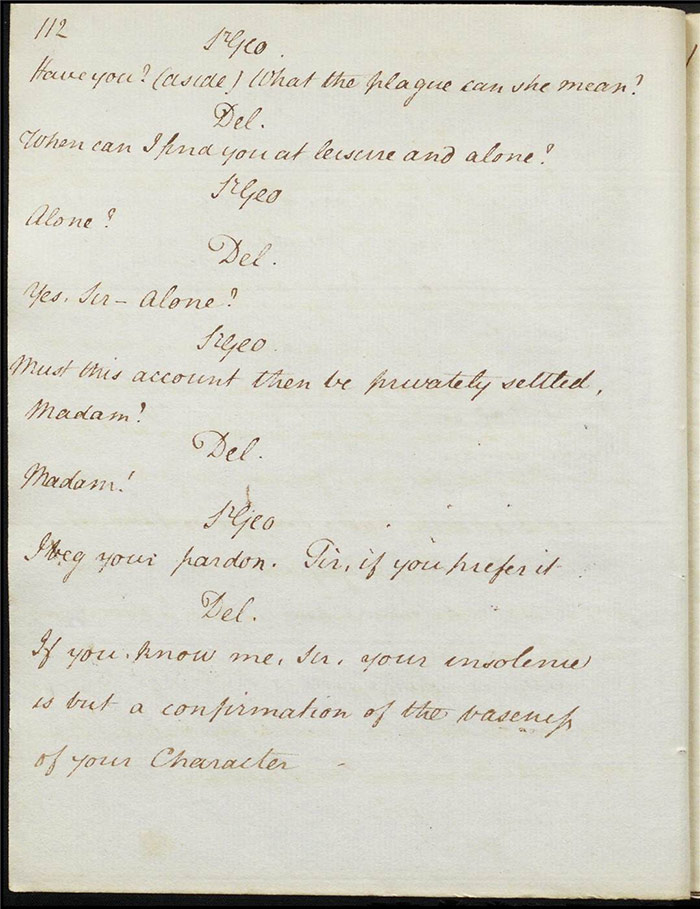

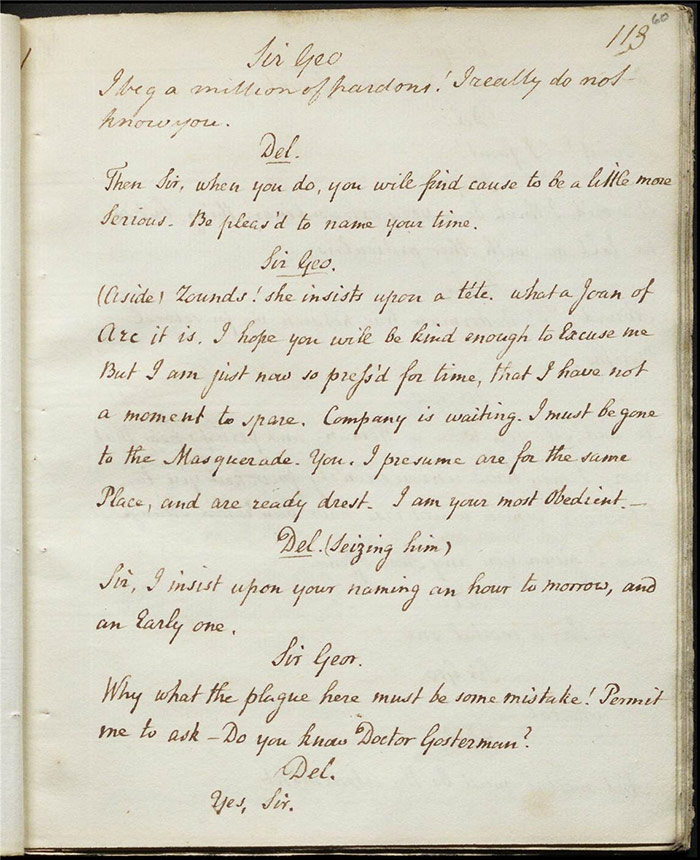

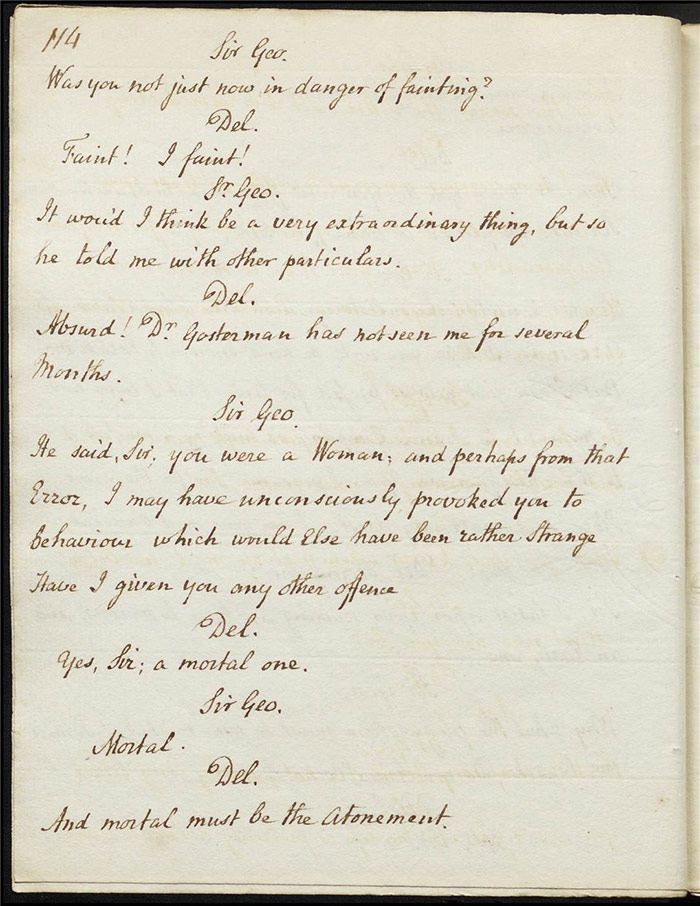

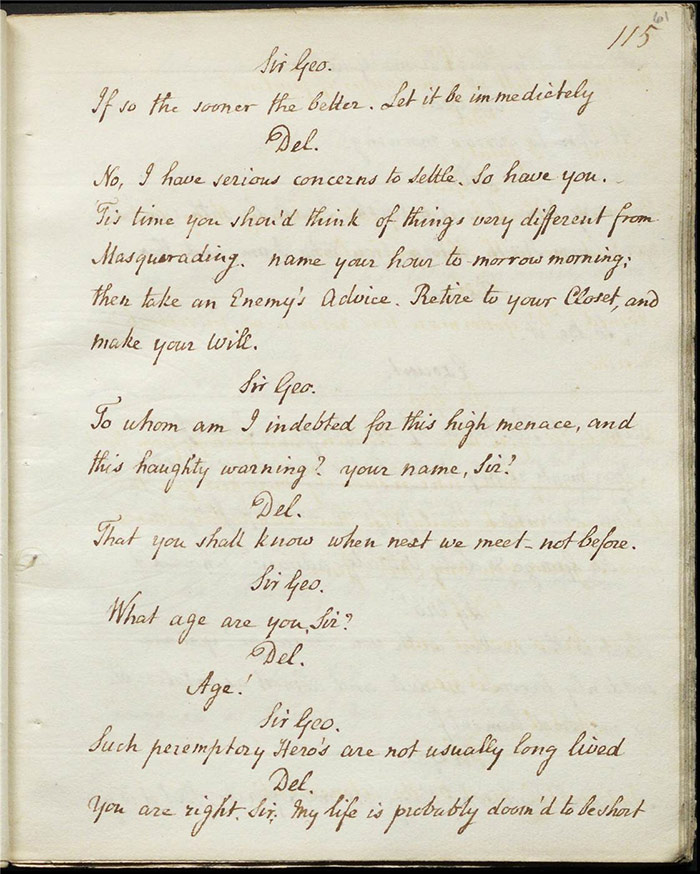

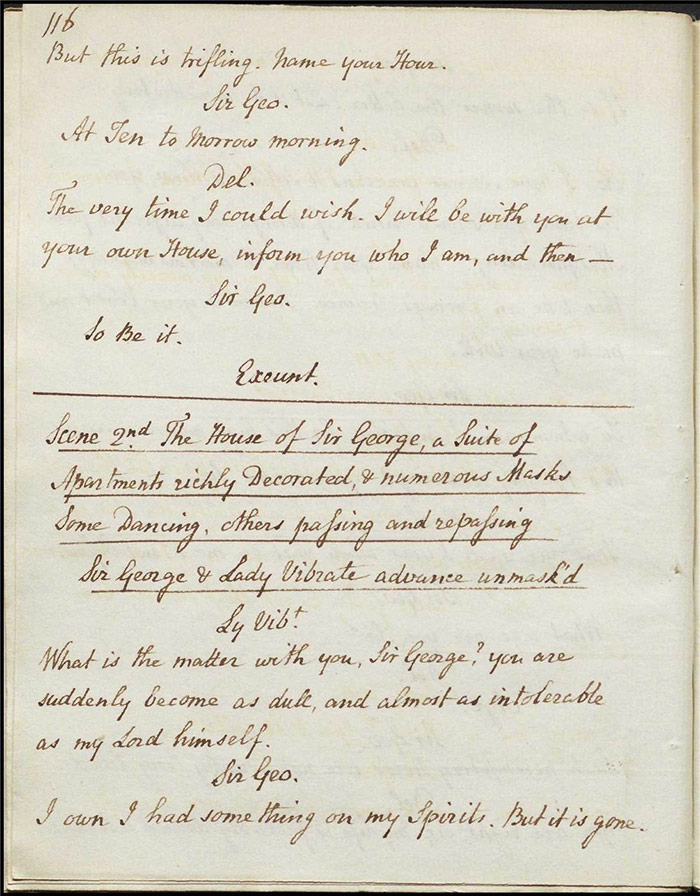

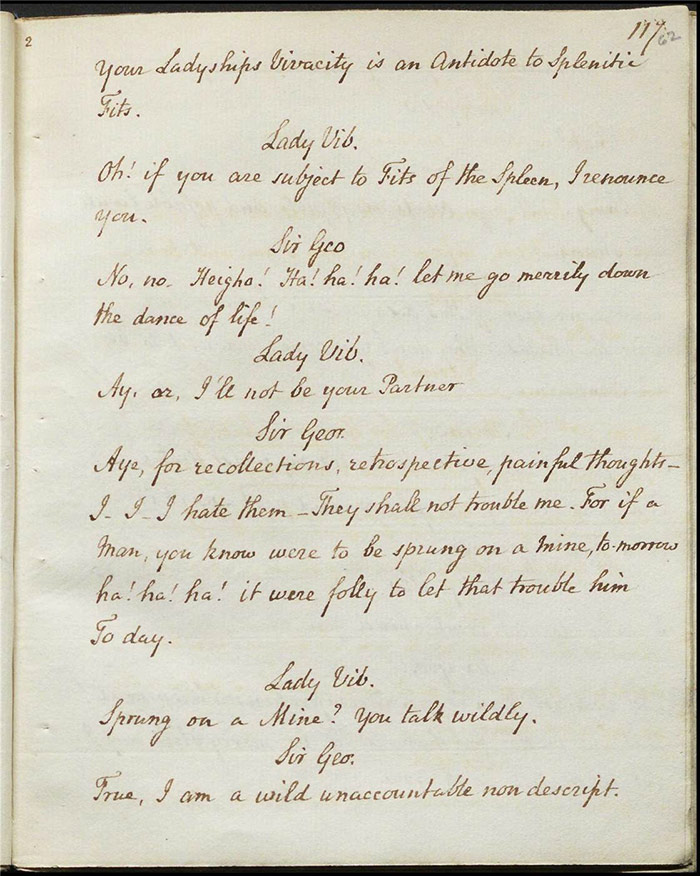

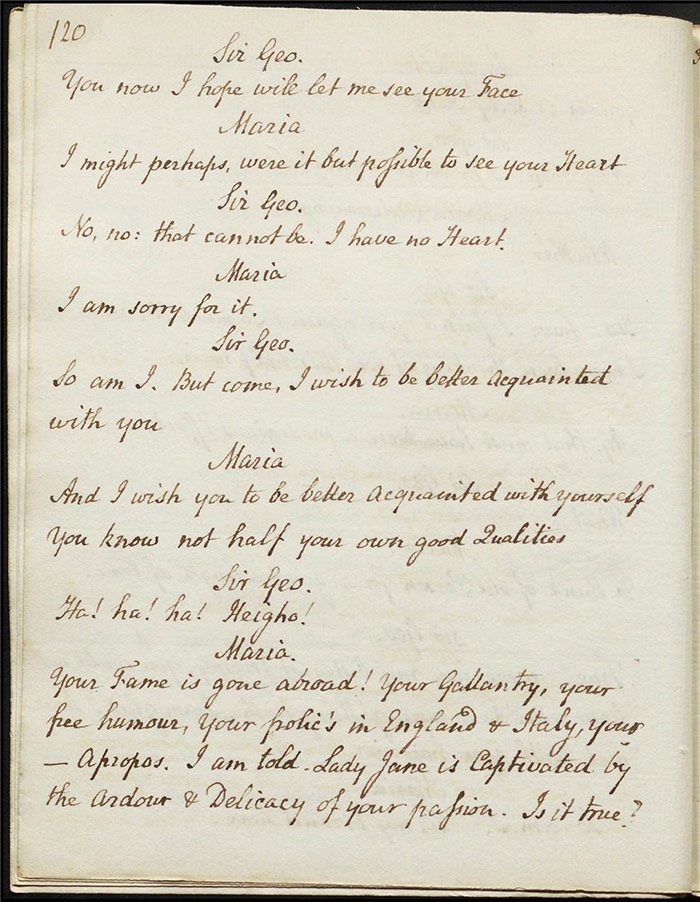

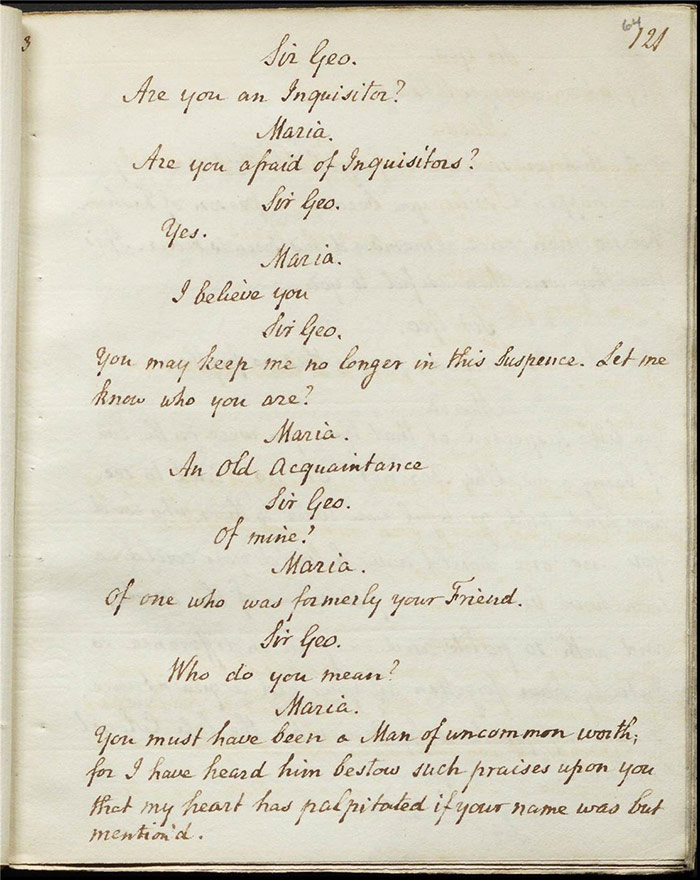

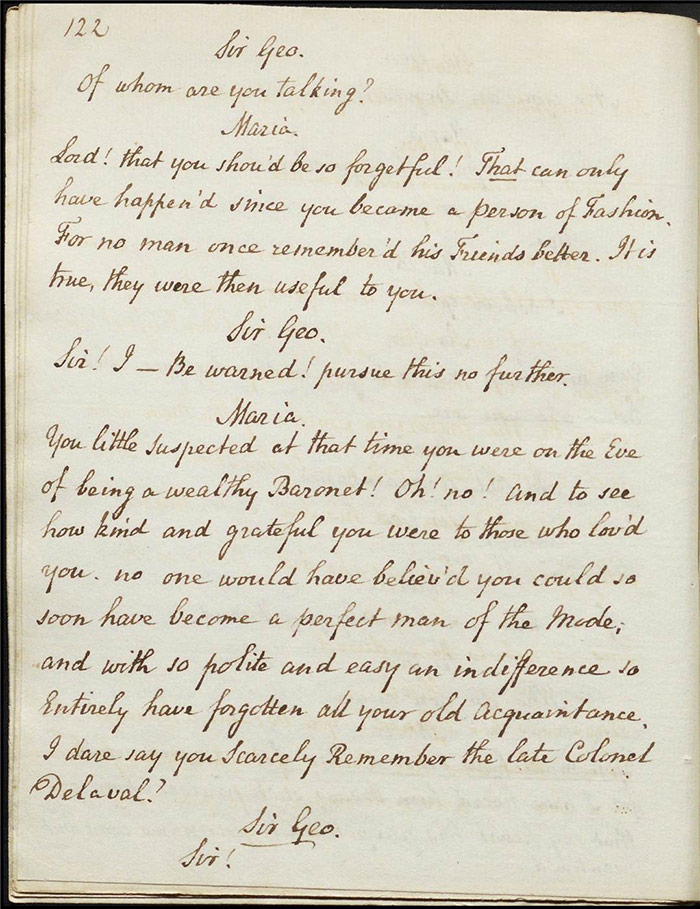

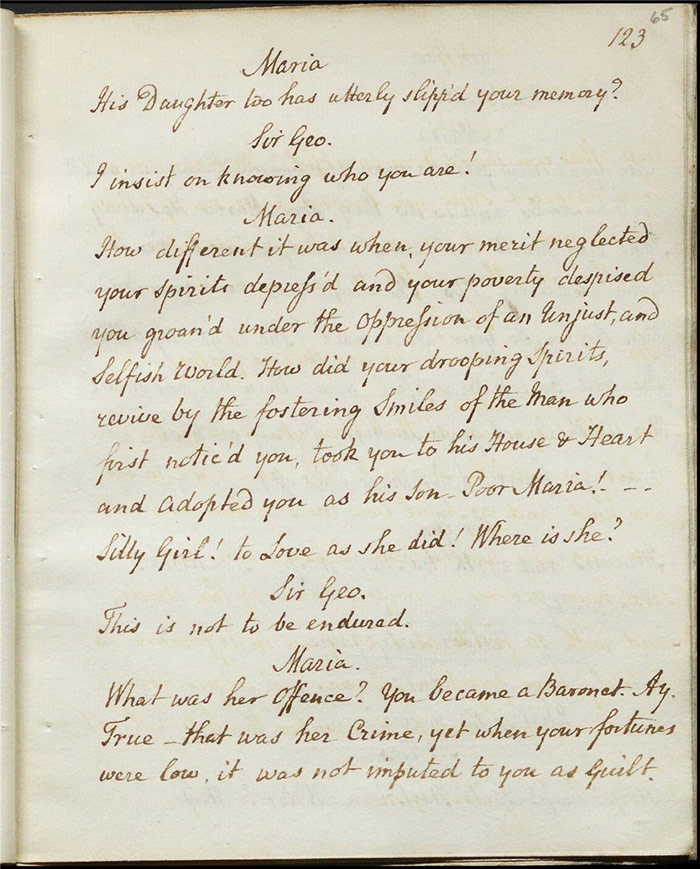

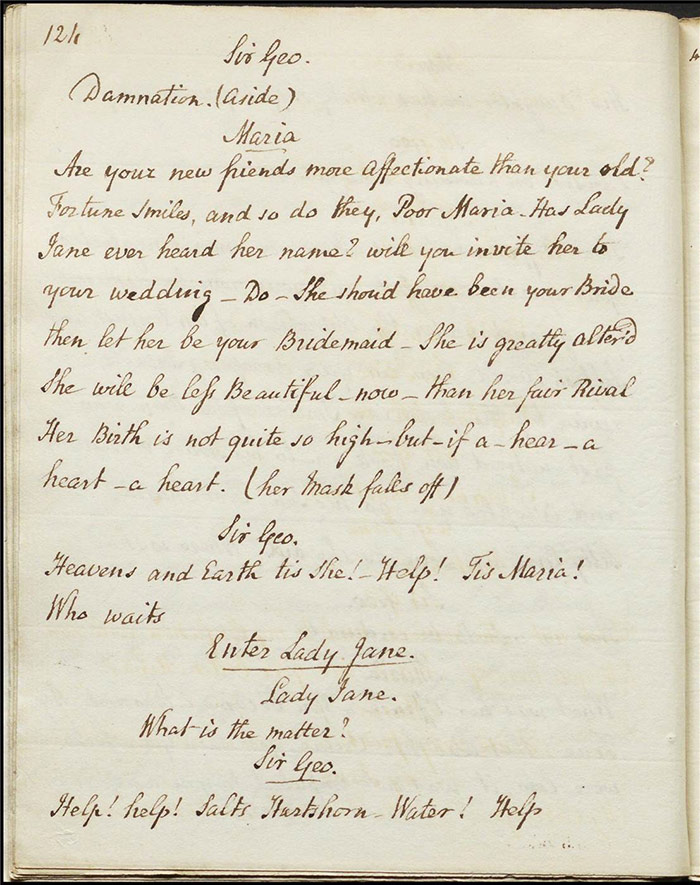

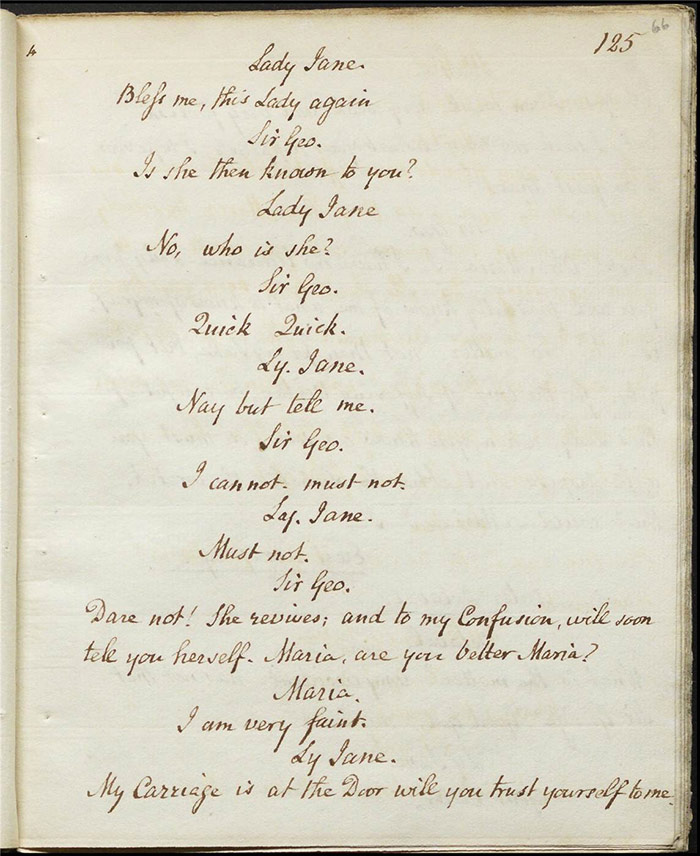

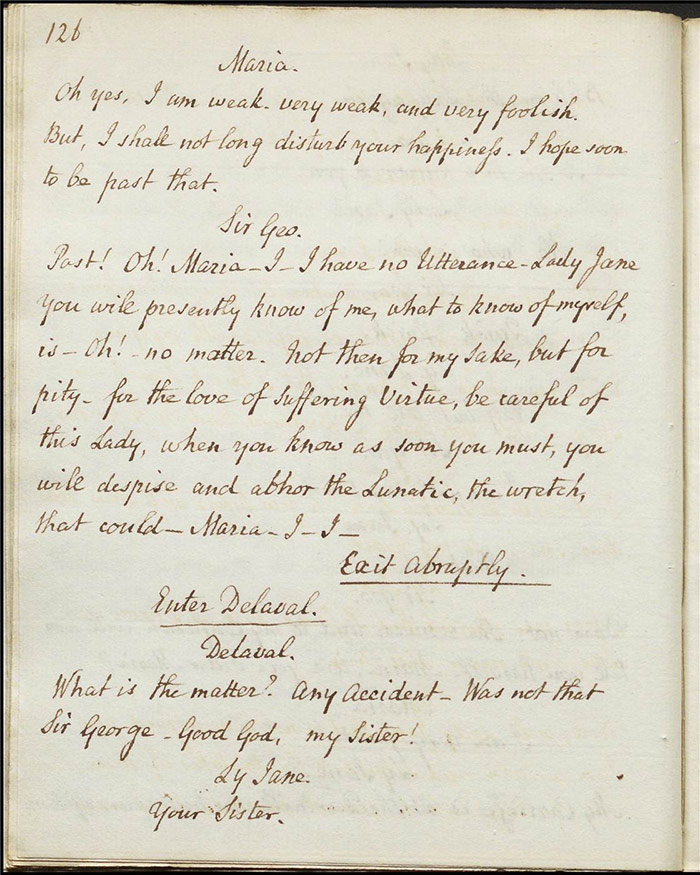

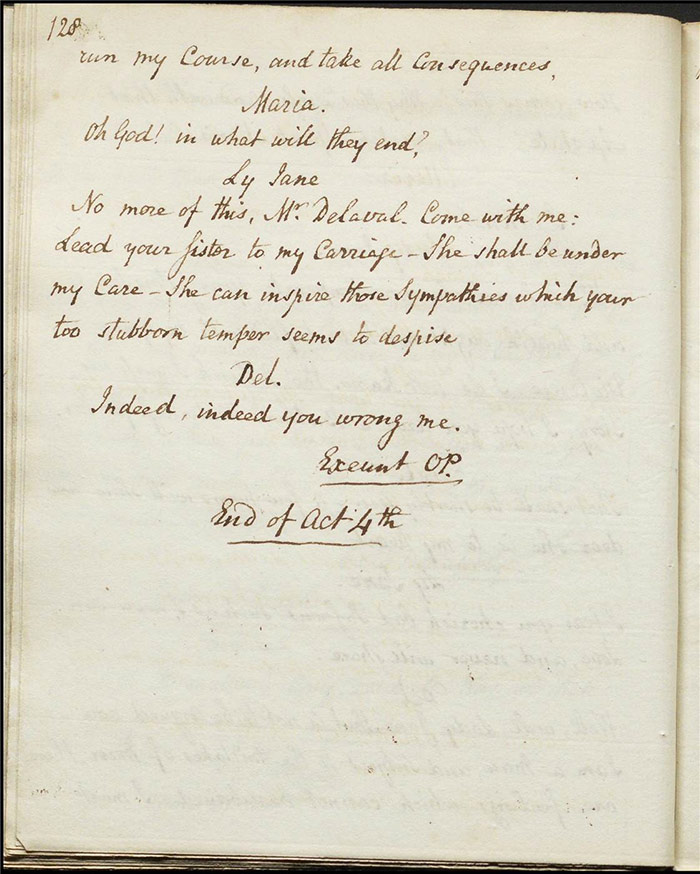

Maria, still disguised as a man, arrives for an audience with Lady Vibrate in act 4 (f.46r). Very agitated, she eventually reveals her true sex and manages to blurt out that she wants to prevent bloodshed before disguising herself again under a cloak and mask when Sir George enters. She promises an alarmed Lady Vibrate that she will explain herself in time. Sir George is quizzed about his love interests by Maria and is perturbed by her but cannot quite recognize her voice. She retires but warns Lady Vibrate not to identify George to the approaching Delaval or vice versa. After some exchanges, Delaval begins to suspect Sir George’s identity but Lady Vibrate fakes a fit in order to distract them. In a separate development, Sir George reveals that he may be acting a part as he discharges a debt for the servant while advising Lord Vibrate not to do so. Delaval recognizes Sir George and challenges him to meet at ten in the morning where he will reveal his name and grievance. At the close of the act, Maria reveals herself to Sir George who is overcome and they are both observed by Delaval.

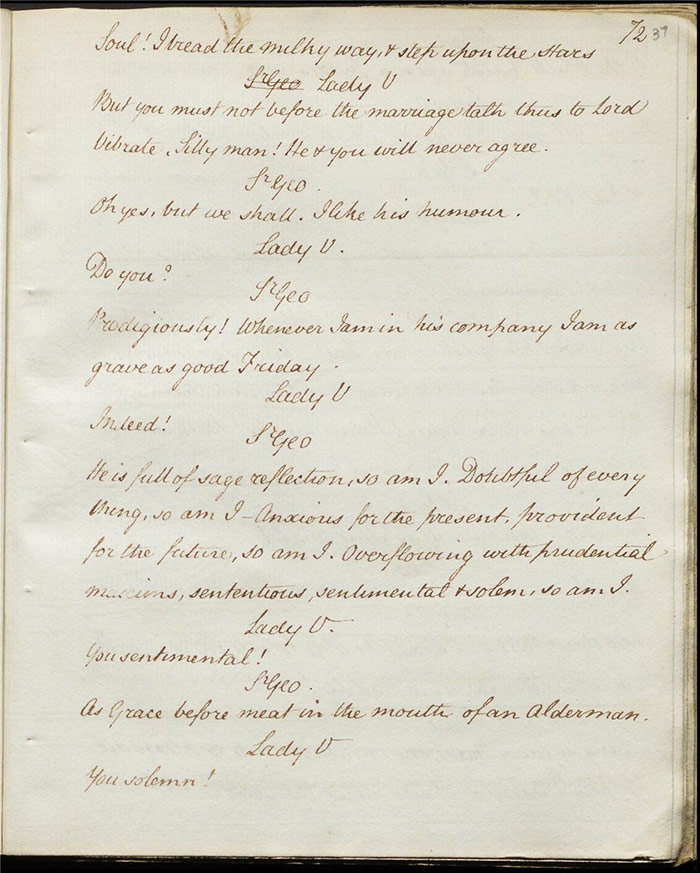

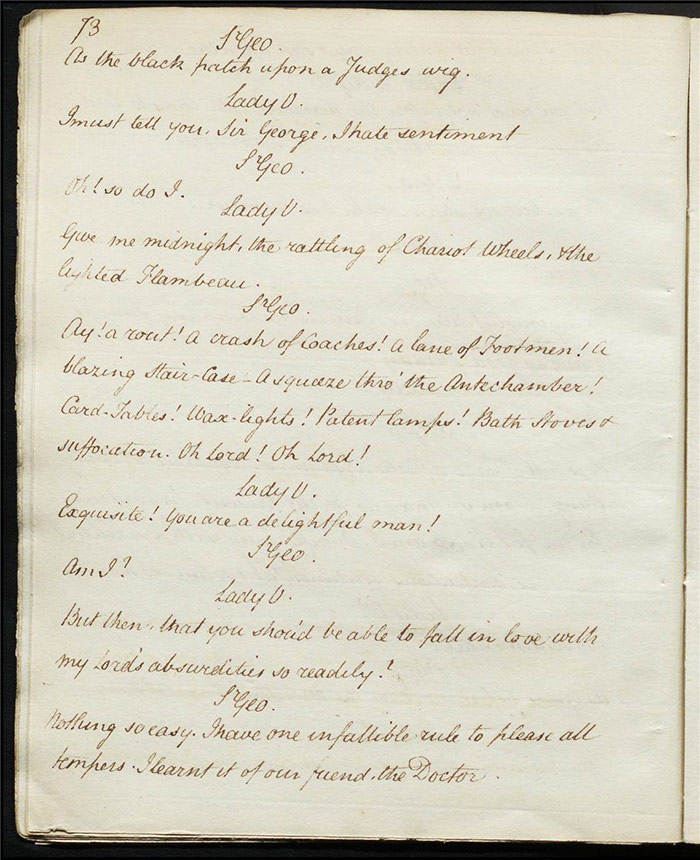

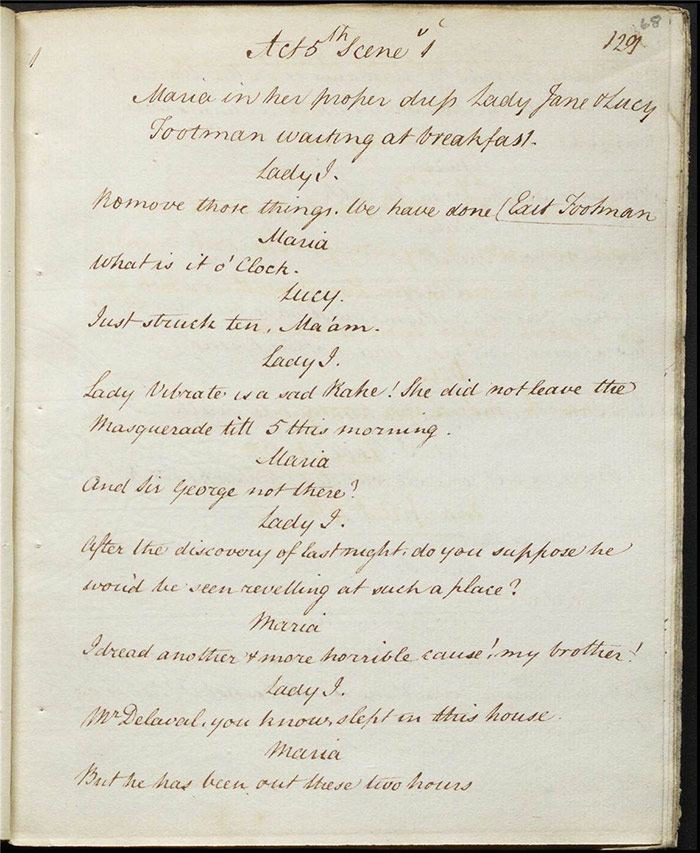

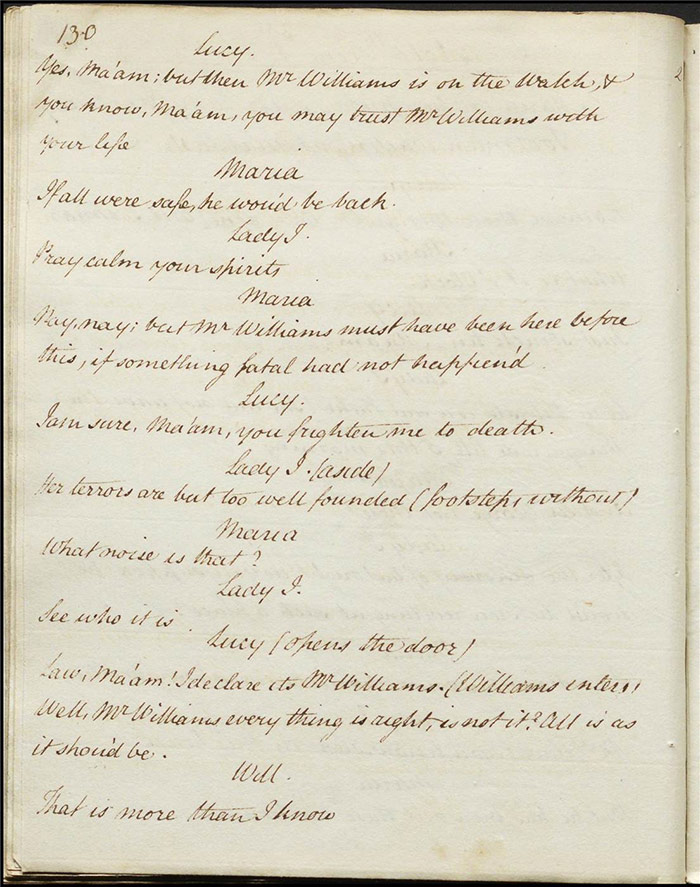

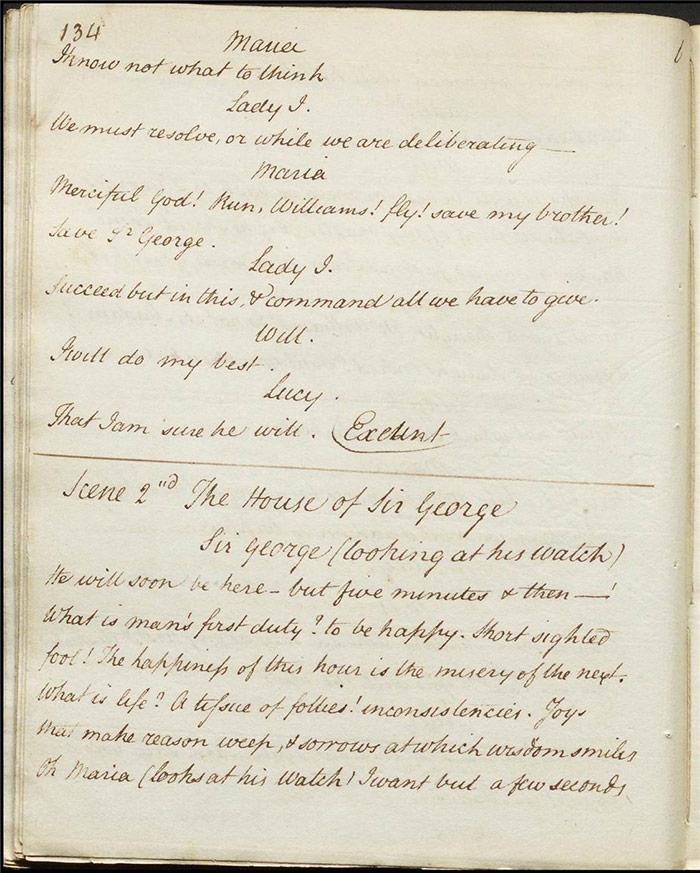

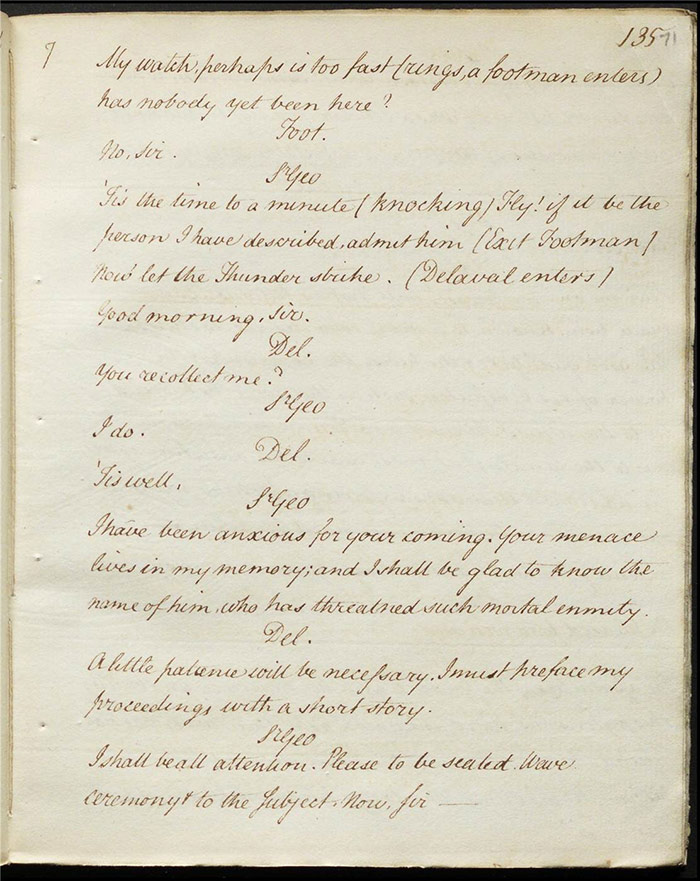

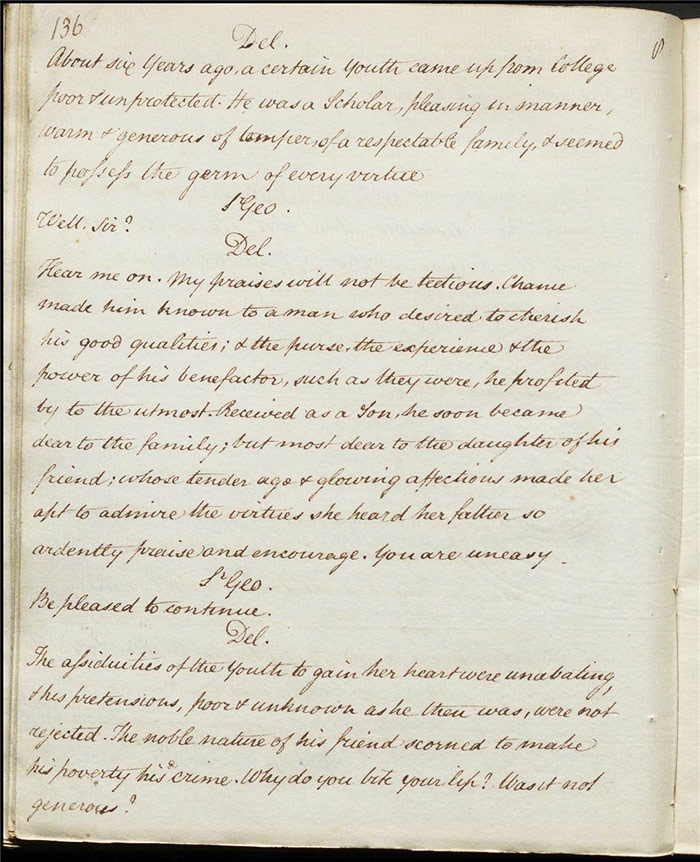

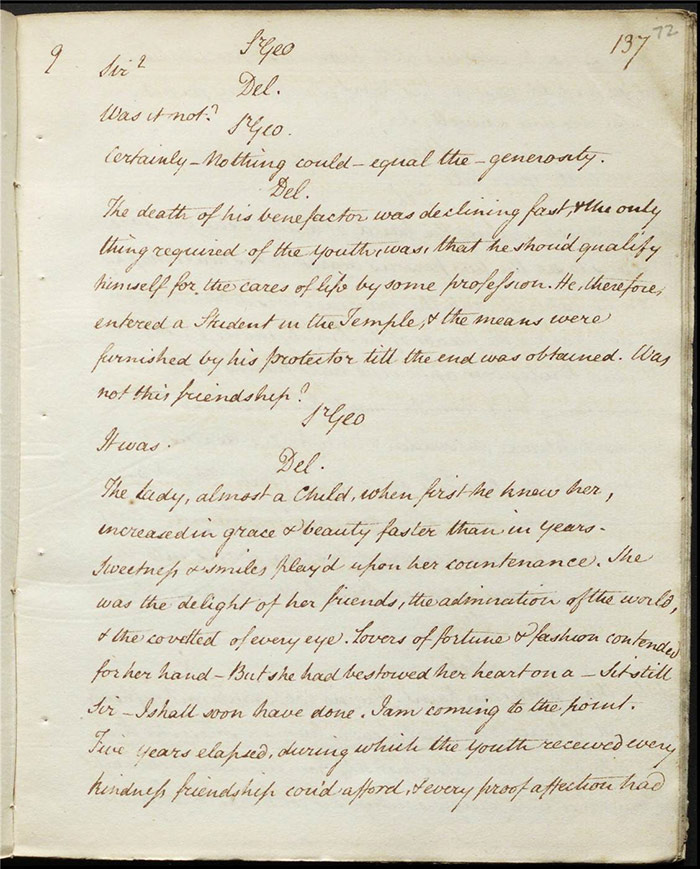

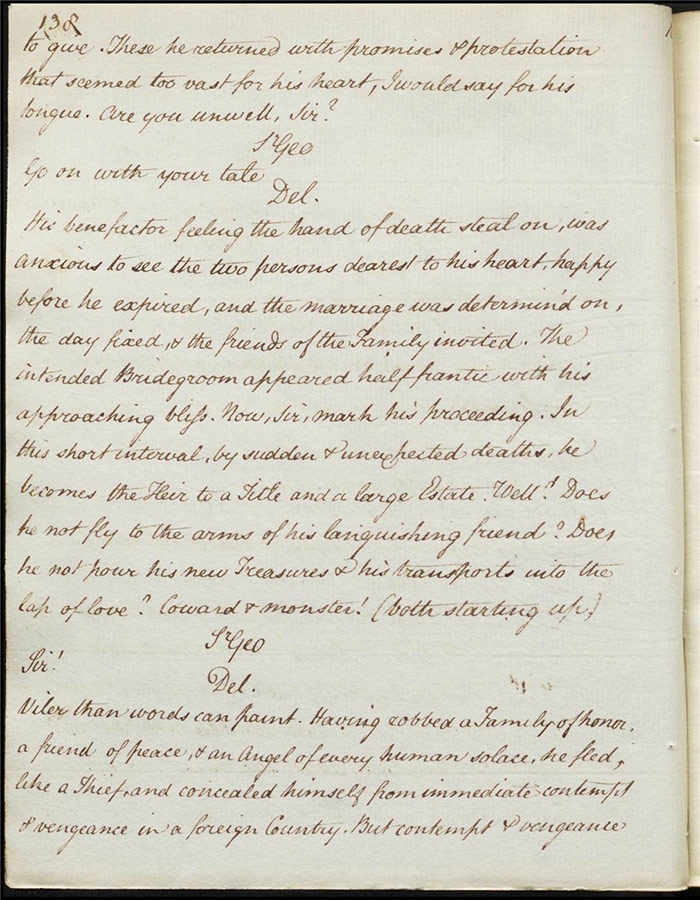

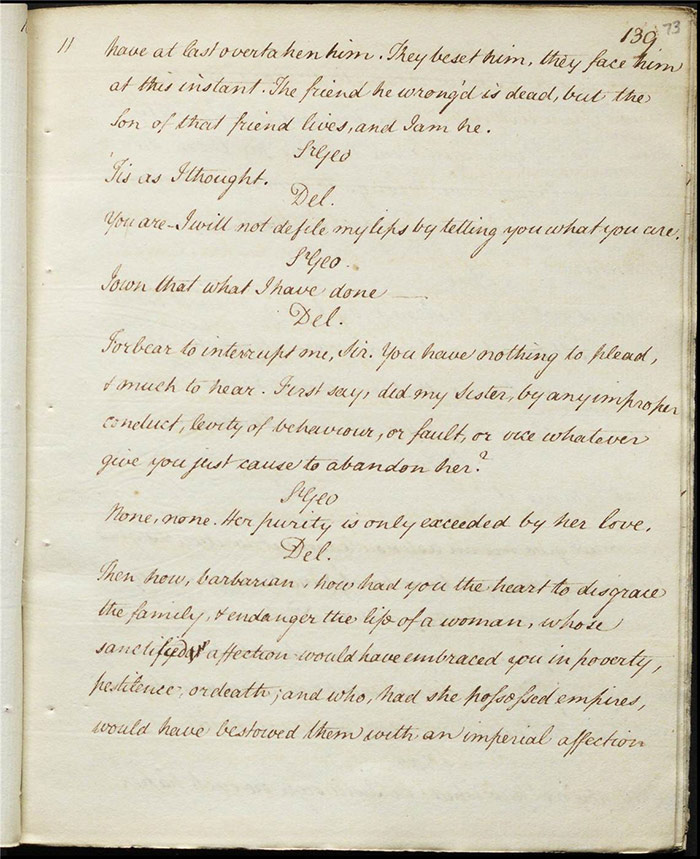

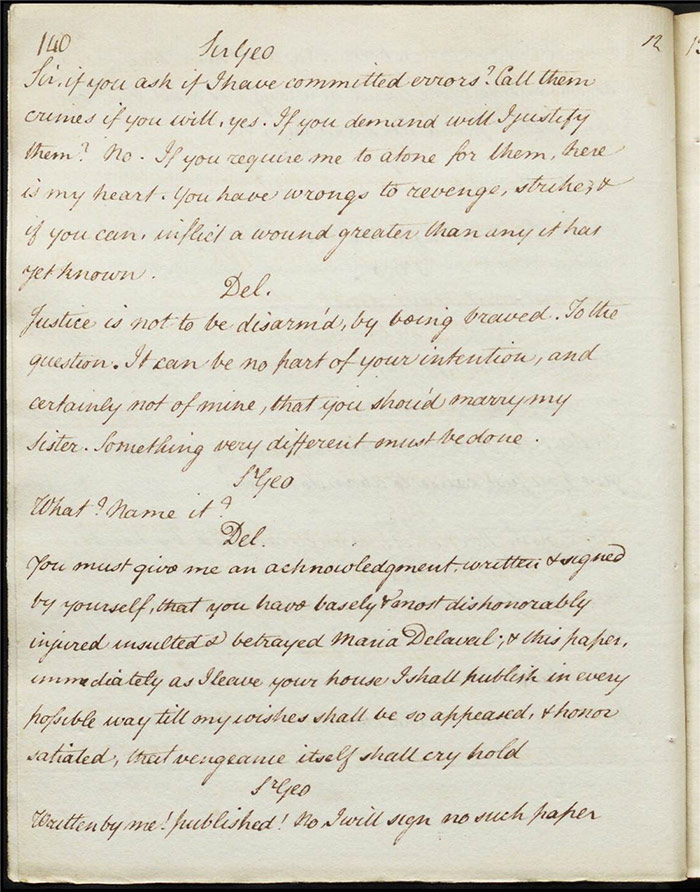

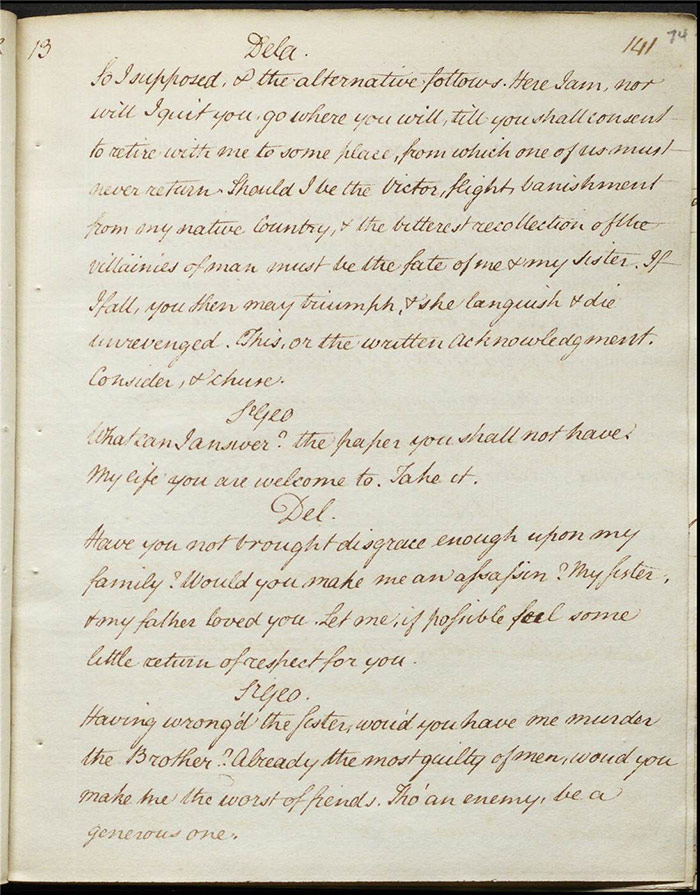

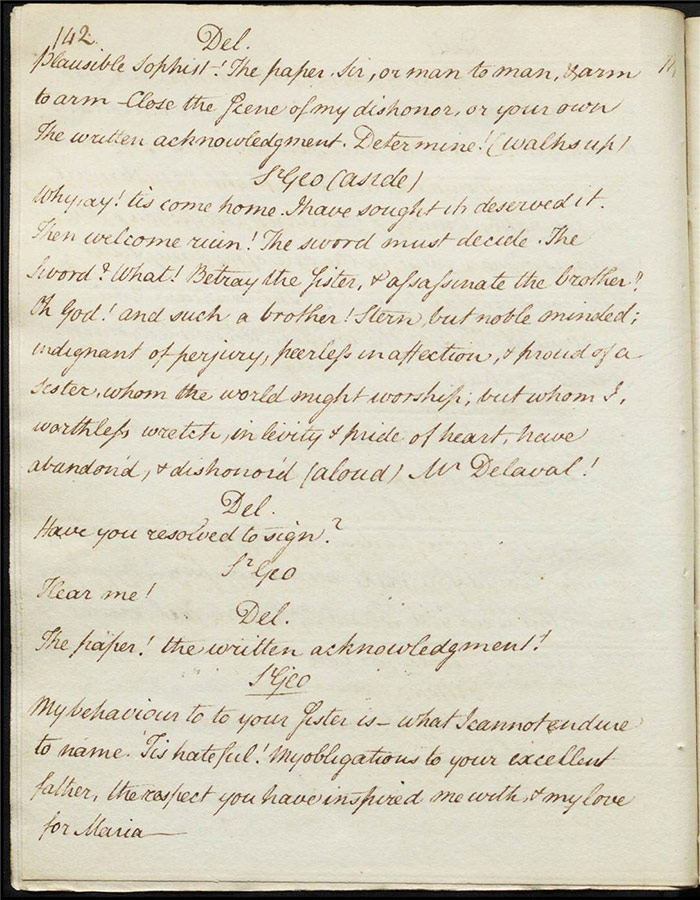

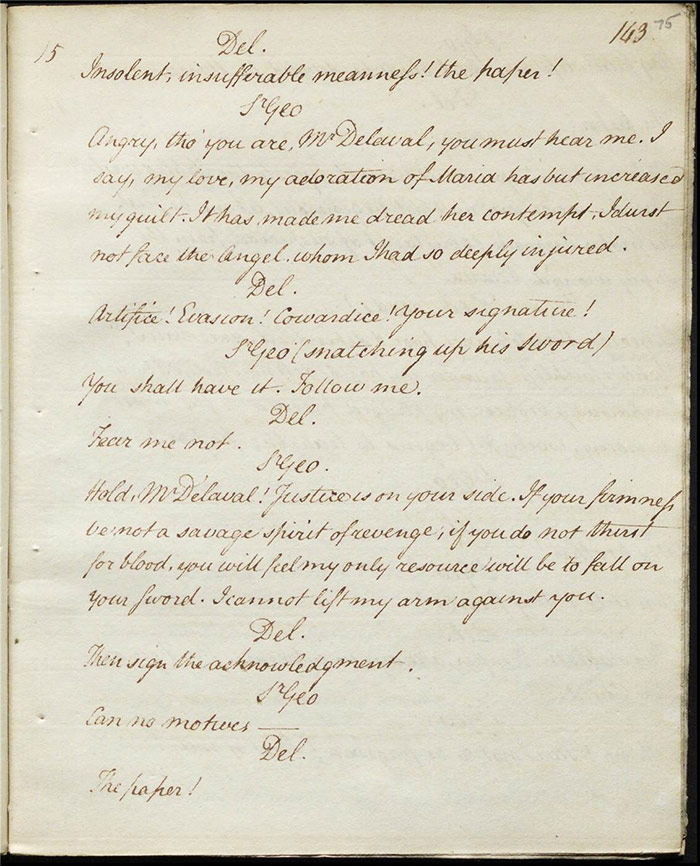

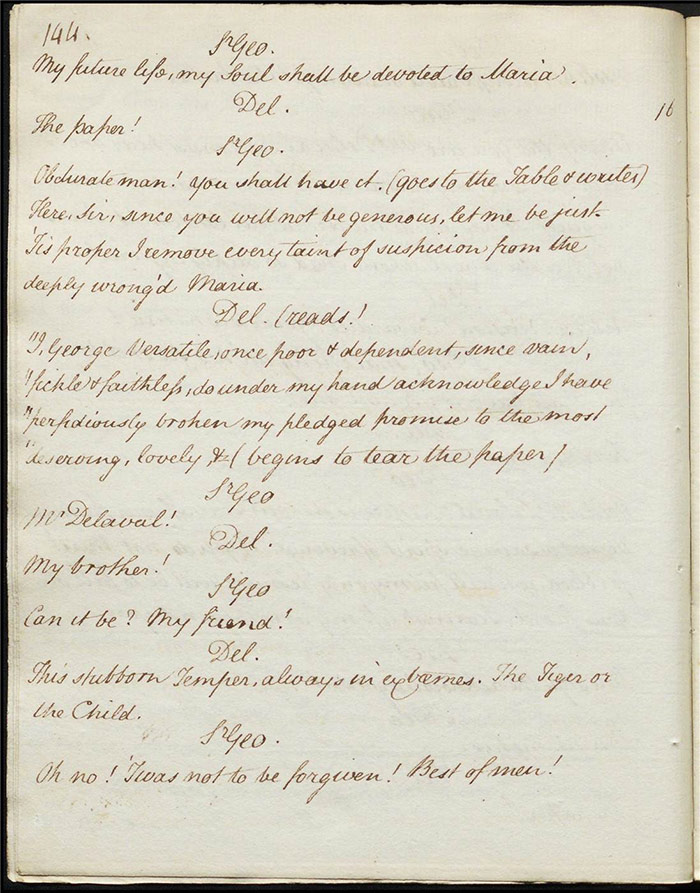

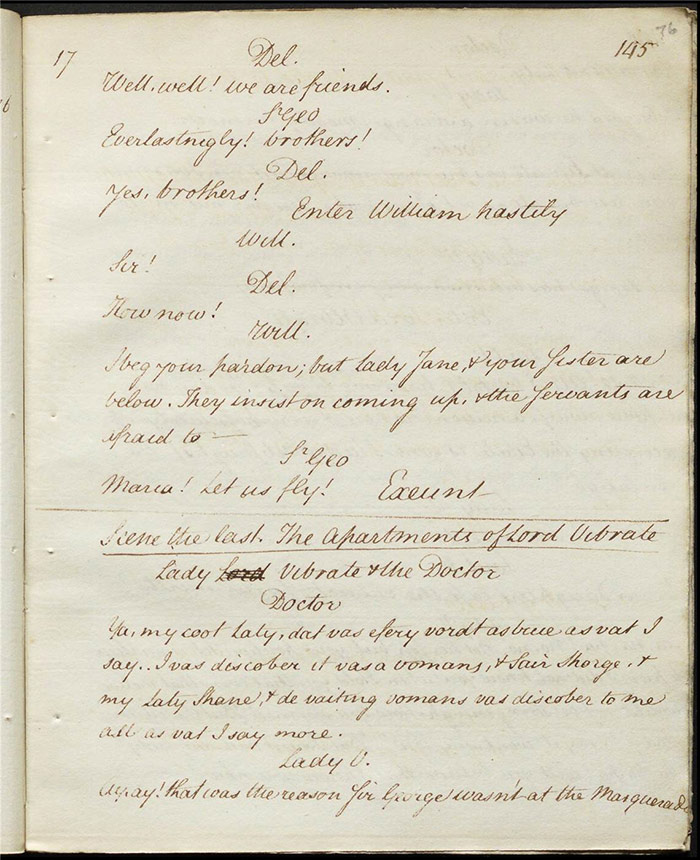

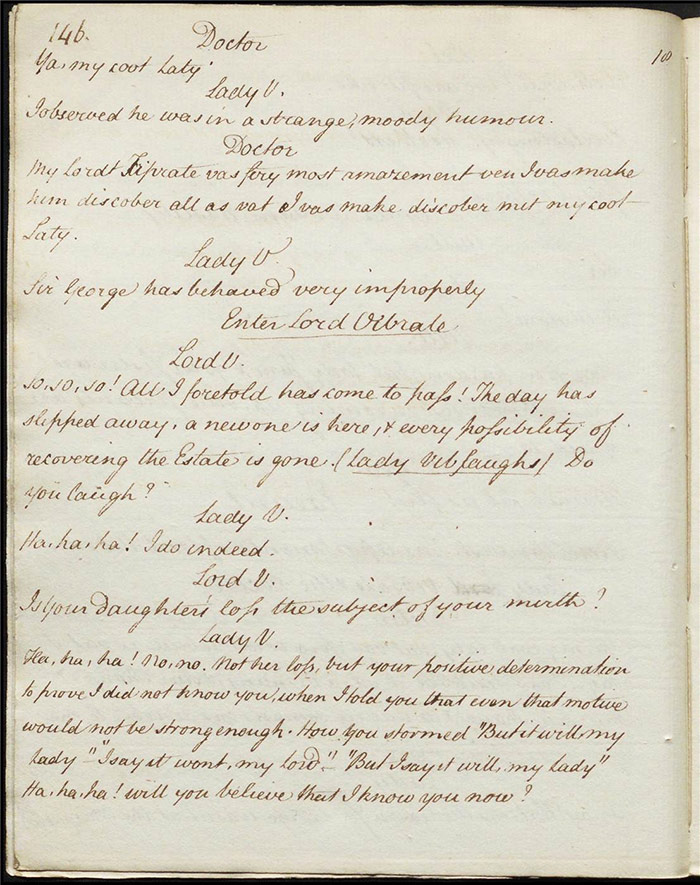

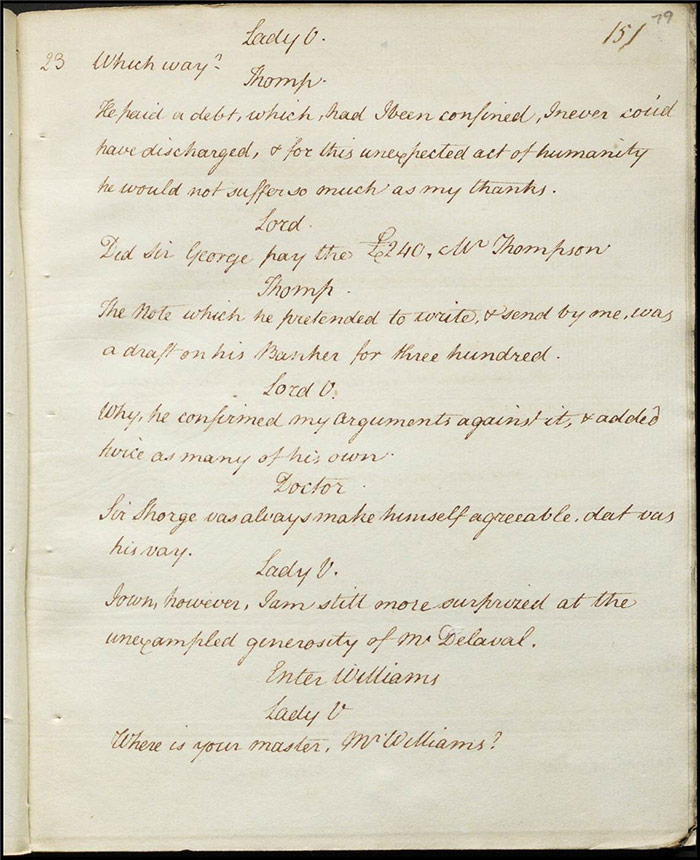

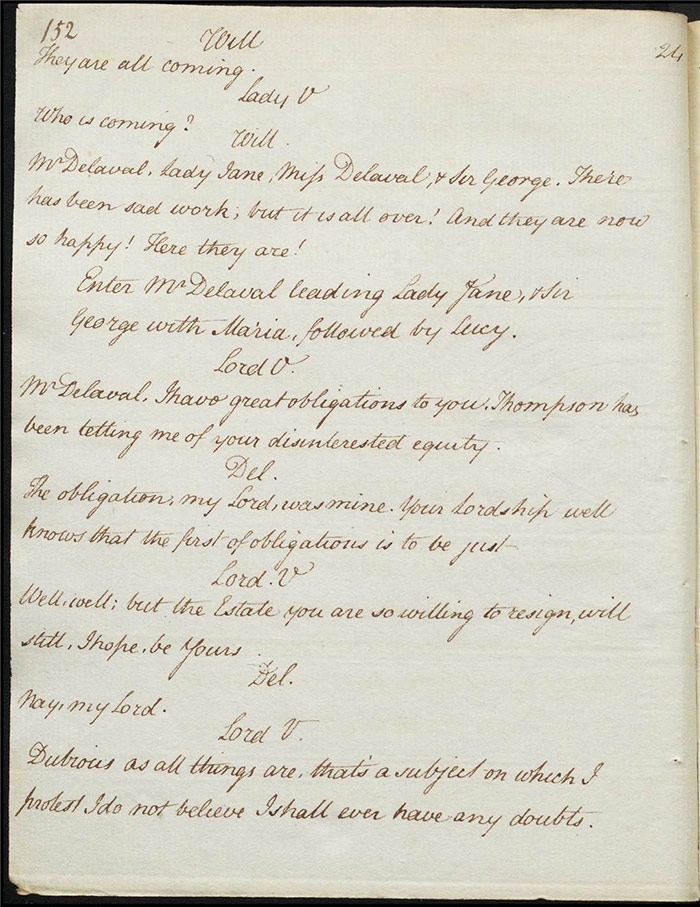

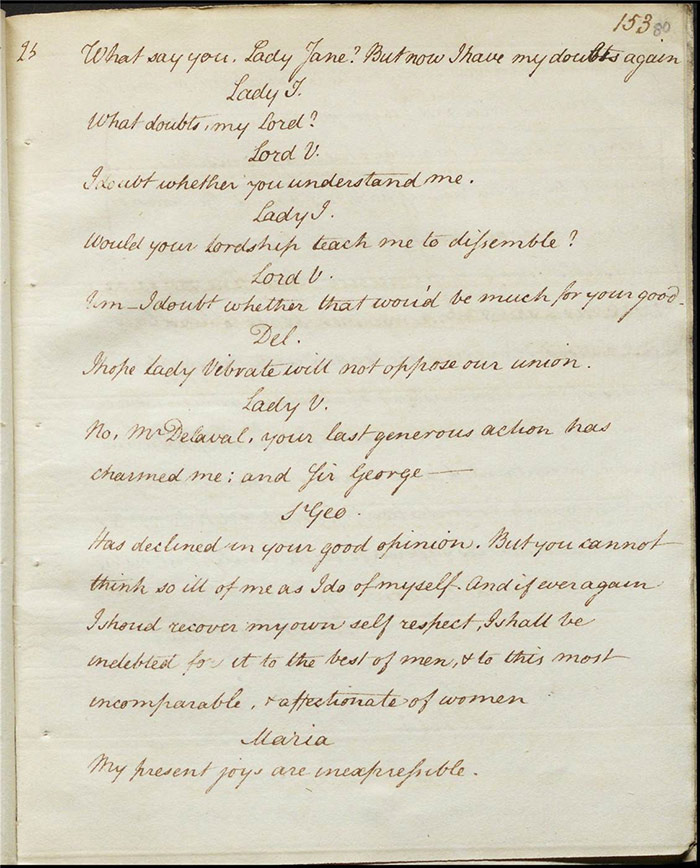

In the final act (f.68r) Delaval confronts Sir George and we learn that Delaval’s father took in Sir George before he was wealthy, paid for his education and took care of his needs. However, when Sir George inherited his wealth he departed, abandoning his fiancée Maria. Delaval demands a publishable confession or a duel. Sir George expresses his heartfelt remorse and after much anguish, agrees to provide the paper but Delaval tears it up and they are reconciled. Lord Vibrate discovers that Delaval owns the title to the land to which he wishes to lay claim and Delaval resigns his opposing claim unconditionally. Impressed that Delaval has made no mention of Lady Jane, even Lady Vibrate has to admit to his honour. Delaval and Lady Jane are thus united as are Sir George and Maria.

Performance, publication, and reception

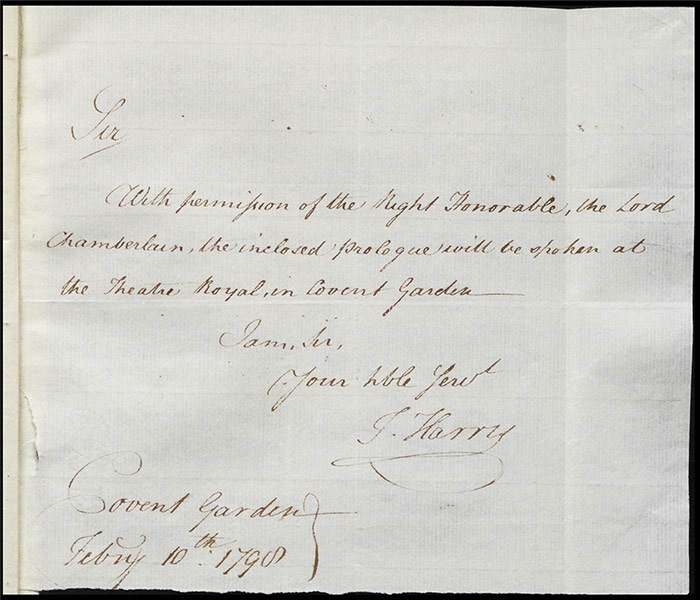

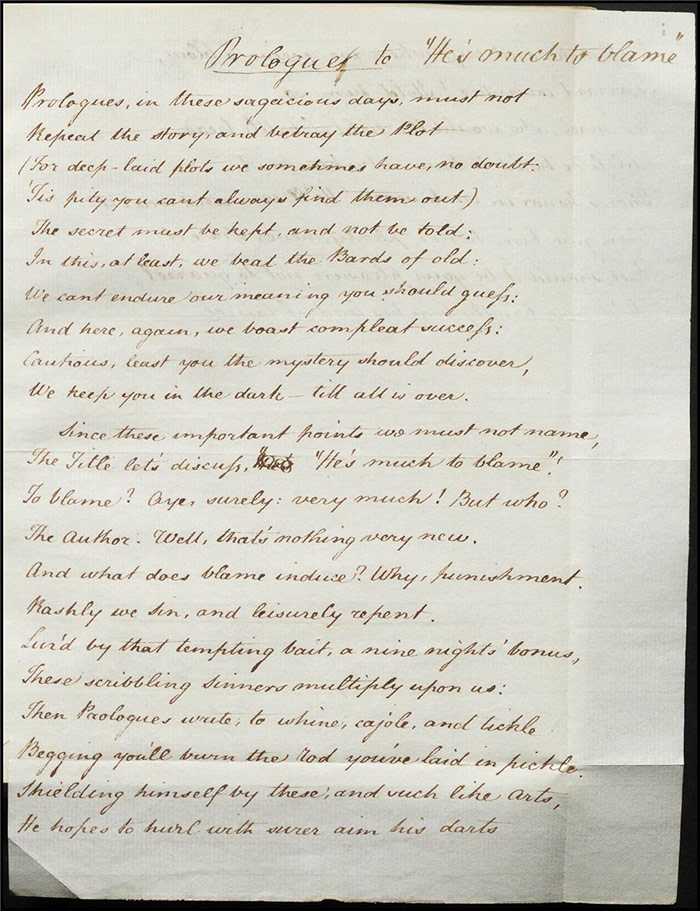

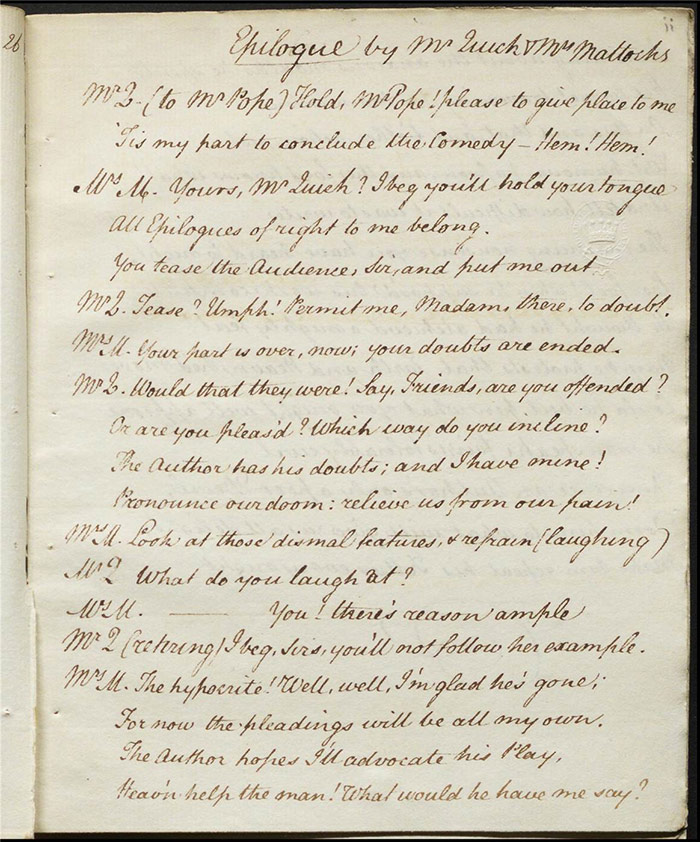

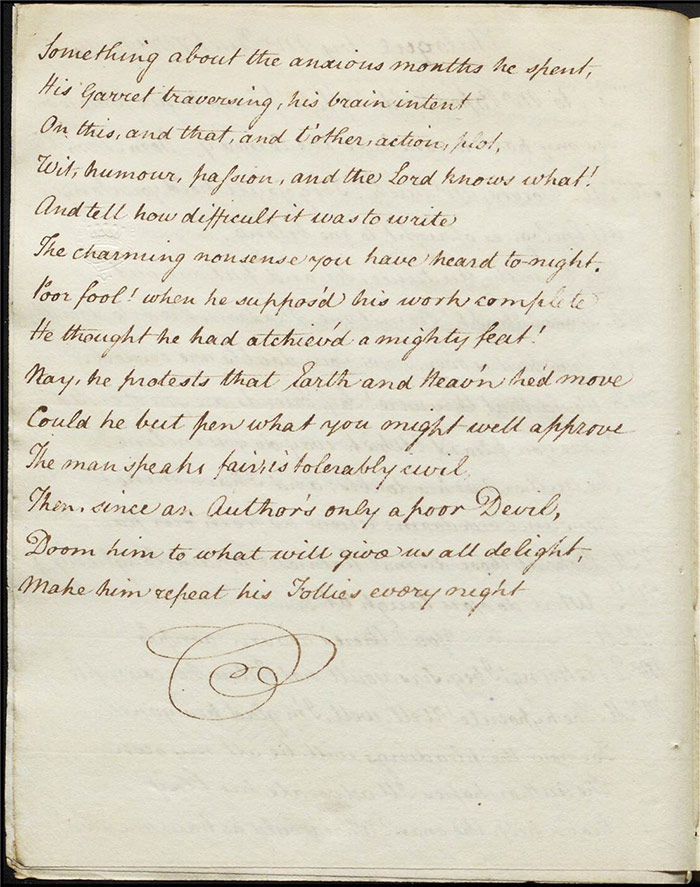

It is unclear when the play was submitted to Larpent. The prologue was submitted by Thomas Harris on 10 February but it appears likely that the play itself was sent earlier, perhaps in two parts (the manuscript suggests that the first three acts were sent with the remainder to follow). The comedy was originally titled ‘The Disloyal Lover’, also indicated by the manuscript.

The play was performed first on 13 February 1798 at Covent Garden and one indication of its immediate success was that it attracted a royal audience on 16 February. Due to his ‘acquitted felon’ status after the Treason Trials, Holcroft wisely decided to keep his authorship a secret and asked his friend, the radical John Fenwick, to claim the authorship. As the Bell’s Weekly Messenger (18 February 1798) testifies, the gambit succeeded (He’s Much to Blame is ‘said to be written by a Gentleman, new to the town, of the name of Fenwick’). The review, like the majority of them, was extremely positive: the story is told with ‘such consummate skill’ that ‘if the Author is new to the Stage, he is thoroughly versed in its laws’. Its success is ‘a compliment to the good sense of the Public’.

The Morning Post and Gazetteer (14 February 1798) was equally enthused: ‘In an age so productive of light, unmeaning, flimsy comedies, it is with no small degree of satisfaction we have to announce one of a different description’. It was ‘…certainly one of the best comedies which we have witnessed for some time’ and had the ‘singular merit of uniting lofty sentiment with great amusement; a quality for which modern comedies have not been distinguished’.

The Oracle and Public Advertiser (16 February 1798) went further and placed it among the pantheon of great eighteenth-century comedies, believing that Thomas Harris had made an ‘effort to restore a taste for genuine comedy; and will give the Author, whoever he be, a just claim to place himself on the same form with the writers of The Conscious Lovers, The Clandestine Marriage, The West Indian, and The School for Scandal.’ Three days after its original performance, however, word seemed to getting out about the true author: ‘It is now whispered that the new Comedy “He’s Much to Blame” is Holcroft’s. If so, the title certainly corresponds with the Political Character of the writer’. The authorship was evidently a matter of some public discussion, as The Star (19 February 1798) also felt obliged to dismiss another possible candidate when it insisted ‘that if anyone attributes it to GODWIN, He’s Much to Blame’. Nonetheless, its review was glowing.

Newspapers across the political divide were a little less keen on the play. The Sun (14 February 1798) summed up: ‘This Comedy is lively without extravagance. It is not the work of a vigorous mind, but it is written by a man who has observed the superfices of life, who knows the progress and the conflicts of the passions, and who seems desirous to foster the amiable affections, and to aid the cause of morality’. Despite its general approval of the author’s moralizing, the reviewer did baulk at one scene which revealed that women have breasts to the London audience:

The only objectionable passage through the Piece is, the manner in which the Doctor discovers that Miss Delaval, in her virile habit, is a woman. This discovery might easily be accomplished without making the Doctor perceive her sex, in attempting, while she is fainting, to untie her neck-cloth.

William Hazlitt identified the play as ‘the finest specimen Mr. Holcroft has left of his powers for writing what is commonly understood by genteel comedy’ (Memoirs, II: 219). The play was published in 1798 by G.G. and J. Robinson.

Commentary

The manuscript of the play shows a number of emendations in both pencil and pen. As usual, one cannot be certain as to whether Larpent is wielding the pen or pencil—or indeed both—but the interventions are very suggestive of the 1790s context and Holcroft’s willingness to continue to offer social critique despite his blasted reputation.

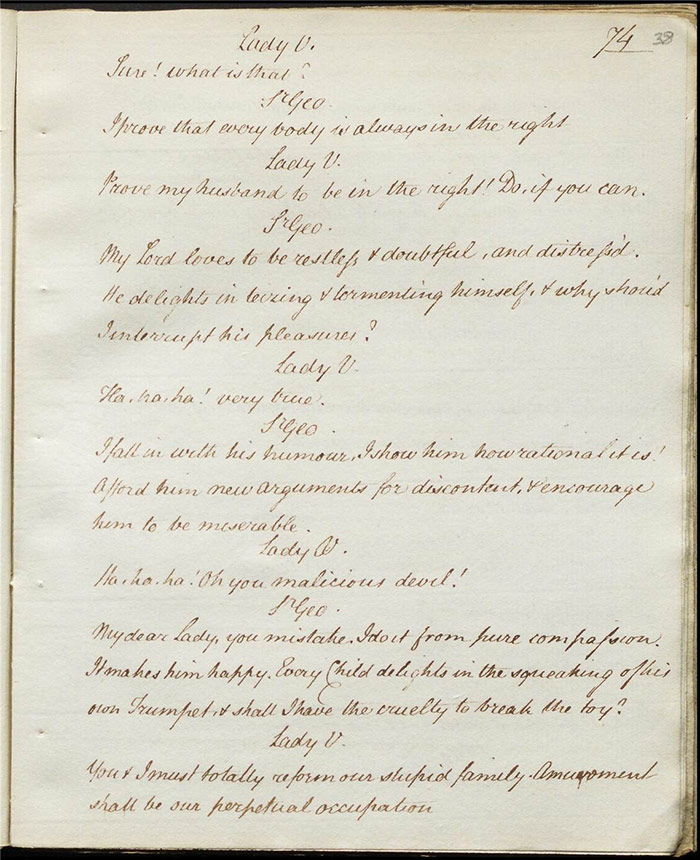

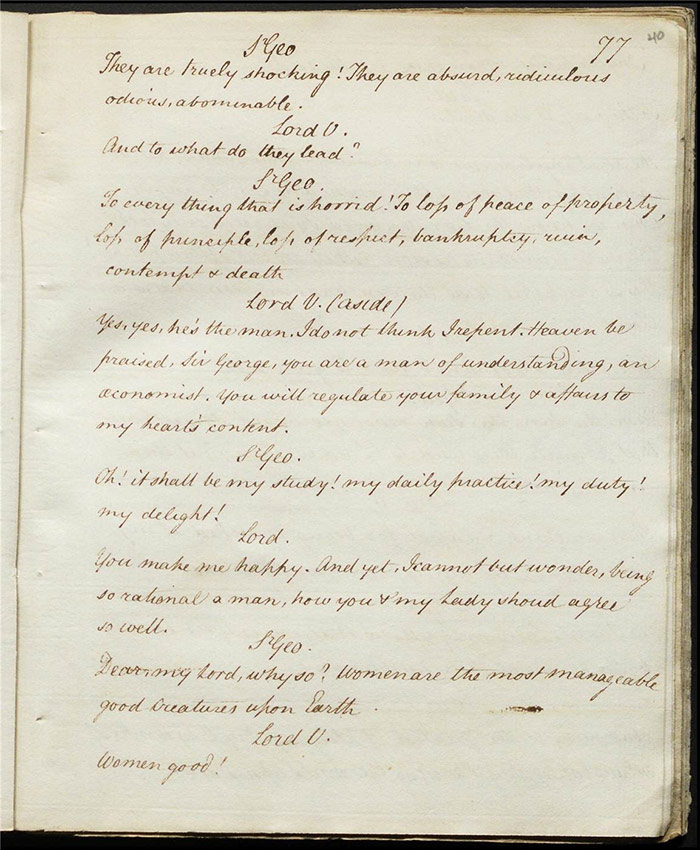

There are only four examples of deleted passages and they all relate to questions of political justice, as we might well expect. On (f.39v) we have the first minor deletion, in both pen and pencil.

Sir Geo[rge]: What is it that buys respect & honor, & power, & privilege, & houses, & lands, & wit, & beauty, & learning,

& Lords, & commons, and

Given the relative lightness of the pencil marks—a series of diagonal lines crossing out the offending phrase—to the heavy scoring out made by the pen, it seems likely that the pencil marks were made first. This may be corroborated by the second example, a dialogue between Lord Vibrate and Sir George:

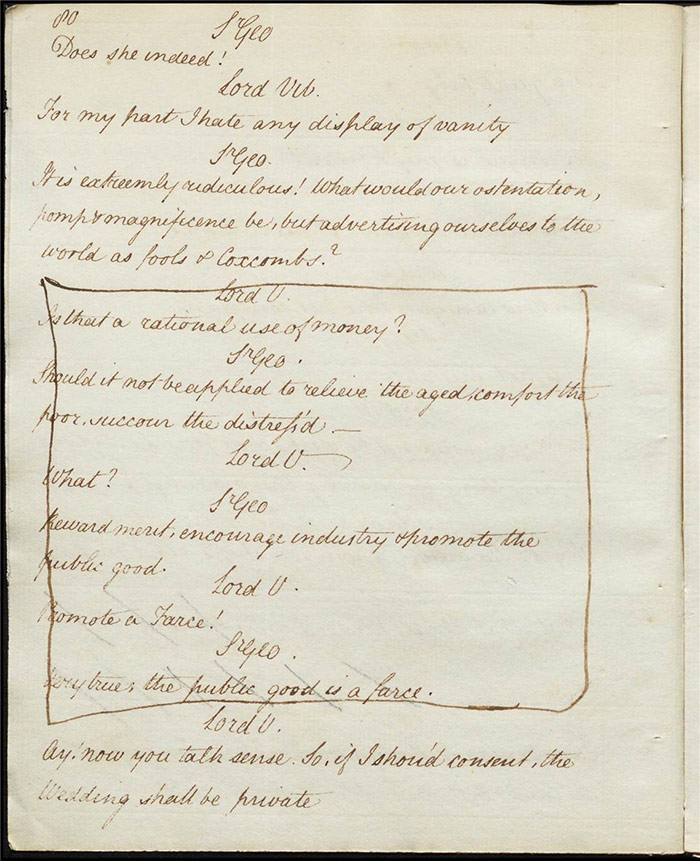

Lord V: Is that a rational use of money?

Sir Geo: Should it not be applied to relieve the aged, comfort the poor, succor the distress’d –

Lord V: What?

Sir G: Reward merit, encourage industry & promote the public good

Lord V:Promote a Farce!

Sir G:Very true, the public good is a farce. (f.41v)

In this example, the final two lines are marked for deletion with a series of diagonal pencil lines. However, the passage in its entirety is boxed in pen – a clear discrepancy. As we shall see in the next example, the likelihood is that the pen was in the hand of Larpent. This leaves us with at least two possibilities for the pencil marks. One is that someone from Covent Garden—such as Harris—had gone through the manuscript and suggested these deletions in an attempt to perform responsible theatre management to the Examiner. The second is that Larpent himself went through the manuscript twice, first with pencil and then with pen to confirm his previous assessment. This may be indicative of increased caution during the volatility of this period.

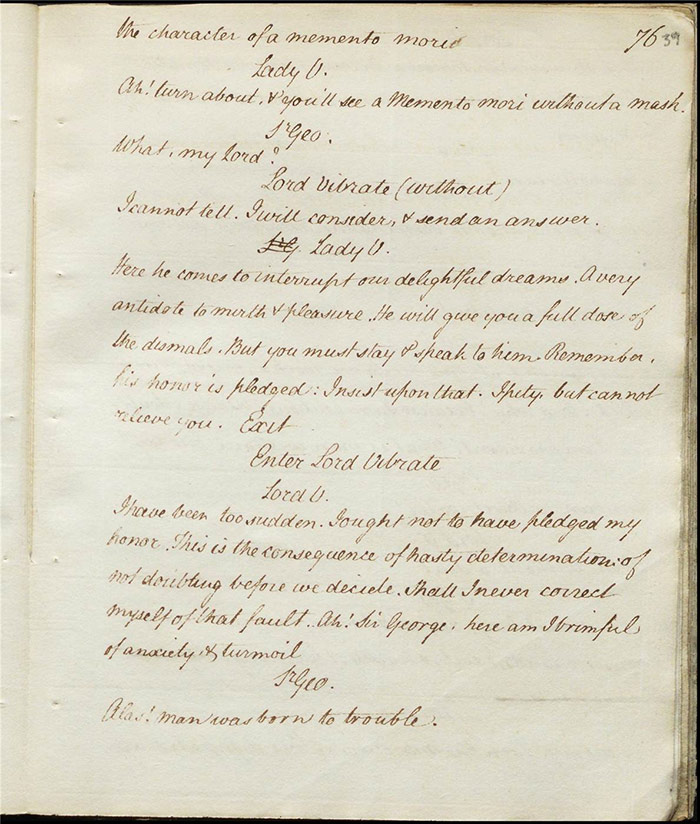

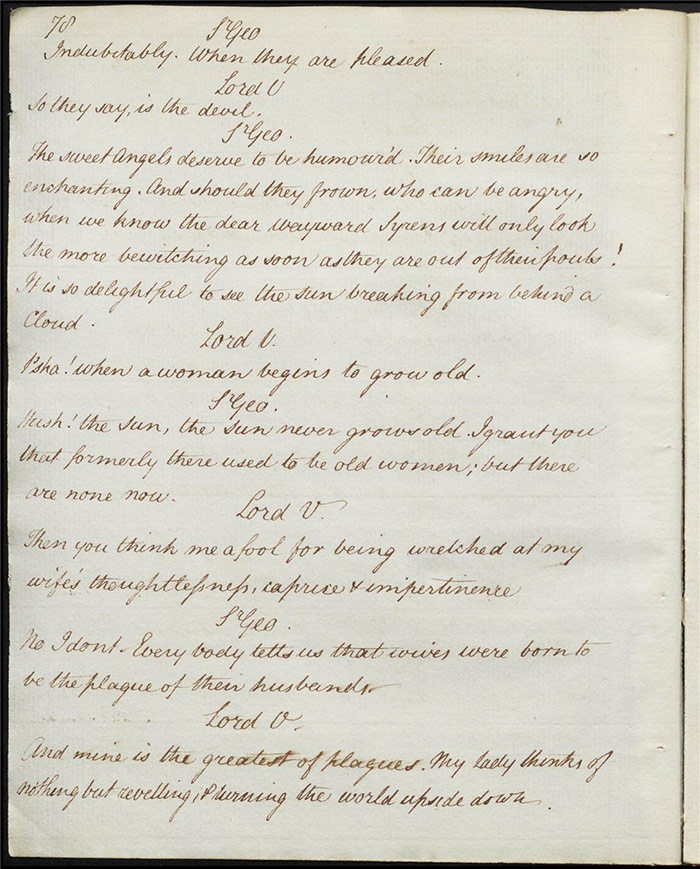

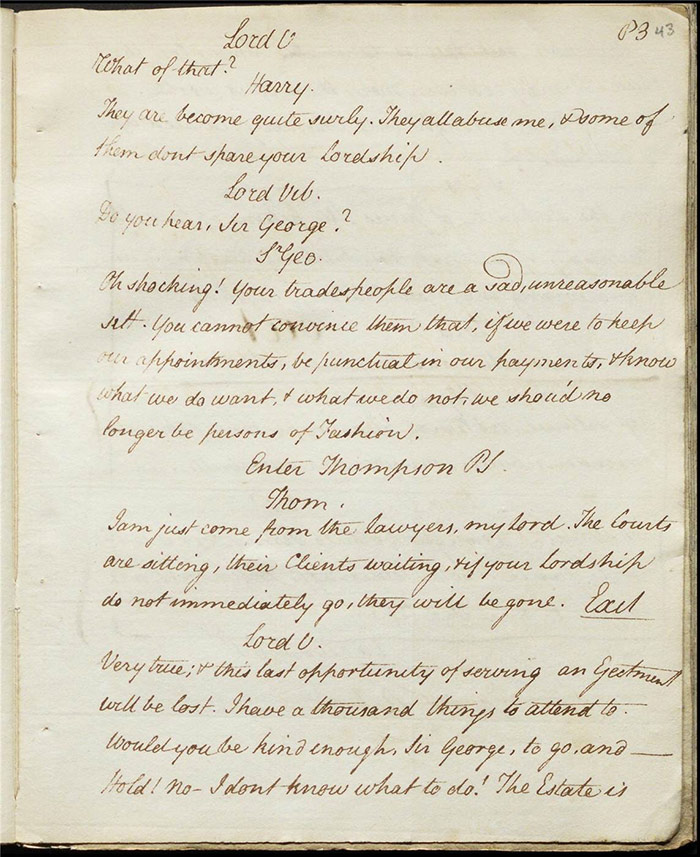

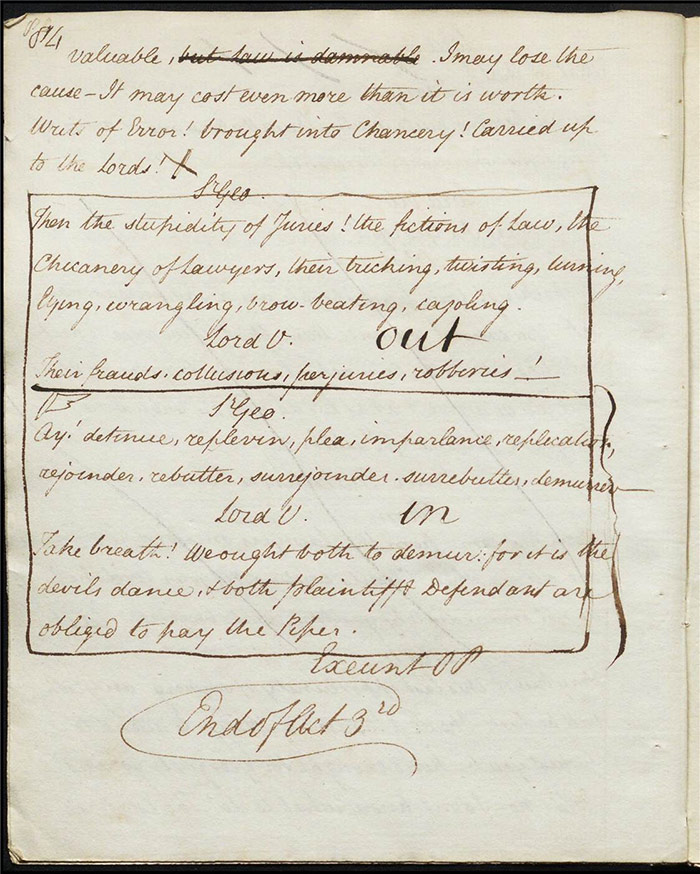

The third example is the most intriguing as it may show a degree of hesitancy, even second-guessing, on the part of the Examiner. Again, it is a dialogue between Lord Vibrate and Sir George:

Lord V: Very true; & this last opportunity of serving an Ejectment will be lost. I have a thousand things to attend to. Would you be kind enough Sir George, to go, and – Hold! No – I don’t know what to do! The Estate is / valuable, but law is damnable. I may lose the cause – It may cost even more than it is worth. Writs of Error! brought into Chancery! Carried up to the Lords. X

Sr Geo:Then the stupidity of Juries! the fictions of Law, the Chicanery of Lawyers, their tricking, twisting, cunning, lying, wrangling, brow-beating, cajoling.(f.43rv)

Lord V: Their frauds, collusions, perjuries, robberies –

Sr Geo: Ay! Detinue, replevin, plea, imparlance, replication, rejoinder, rebutter, surrejoinder, surrebutter, demurrer –

Lord V: Take breath! We ought both to demur: for it is the devils dance, & both plaintiff & Defendant are obliged to pay the Piper.

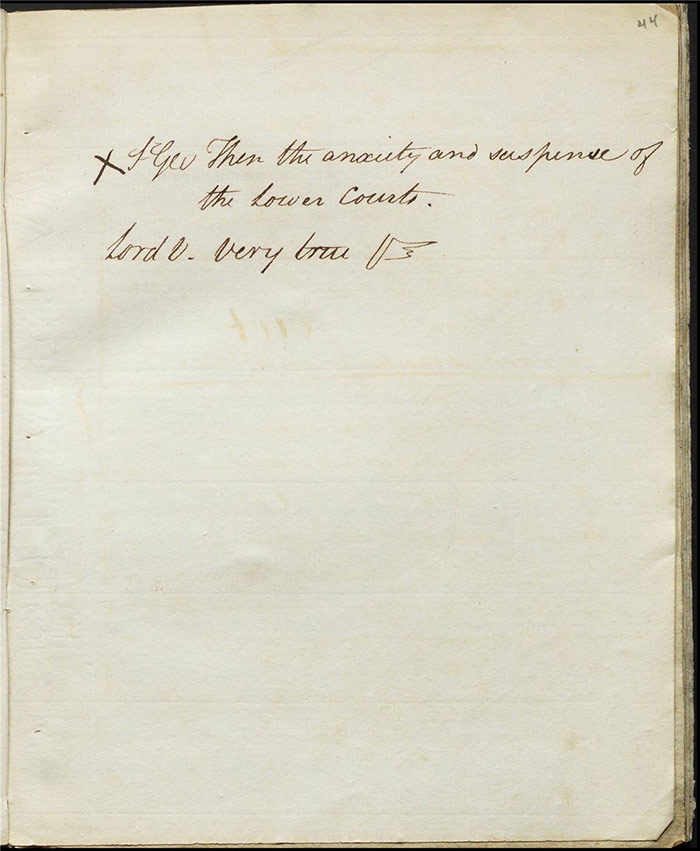

The dialogue struck out above is all marked out in the manuscript with pencilled diagonal lines. It is also boxed in pen in its entirety. However, the box is also divided into two—perhaps retrospectively—with the word ‘out’ inserted in the top half and the word ‘in’ inserted below. The folio opposite offers the substituted text ‘Sr Geo[:] Then the anxiety and suspense of the lower Courts / Lord V.[:] Very true’ for the ‘out’ dialogue. The lower half of the box is also marked with a wavy bracket. Thus it may be possible that Larpent reconsidered his initial exclusion of the full passage.

This raises all sorts of speculative possibilities of why he might have done this. Applying the principle of Occam’s razor, we might simply conclude that he just changed his mind. Alternatively, he may have run it past his wife for her input. Or indeed perhaps an emissary from Covent Garden, keen to maintain these concluding lines to act 3, managed to convince him that the play was on safe ground with the mocking of convoluted legal language, a distinct and well established literary motif, less dangerous than the corruption and criminality suggested by the top half of the box.

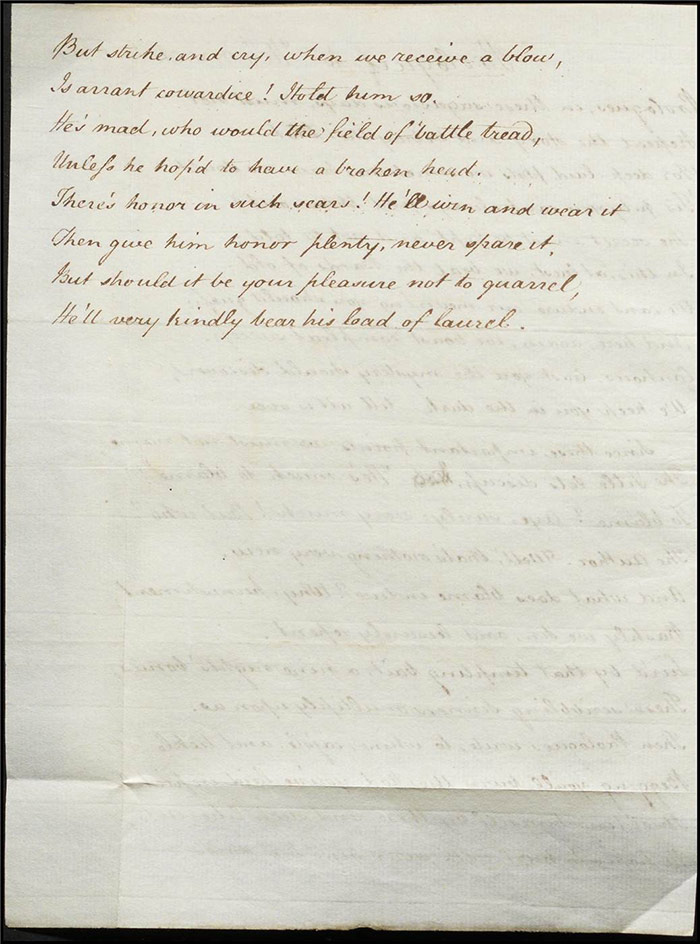

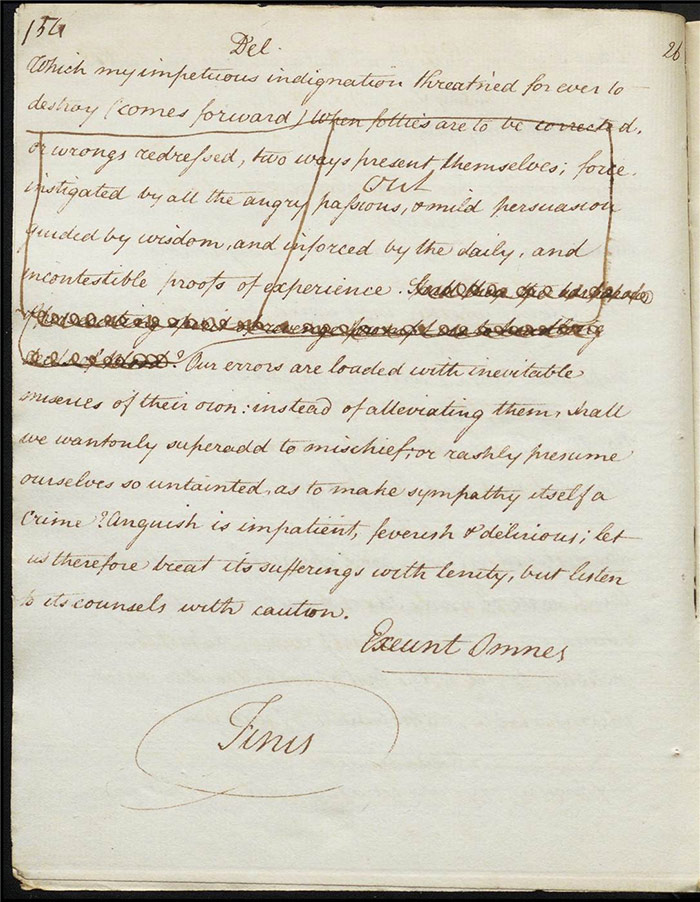

The final act of excision occurs in the closing speech of the play on (f.80v). Evidently, Holcroft, after many moderate pages, could not contain himself at the last:

Del: Which my impetuous indignation threat’ned for ever to destroy (comes forward) When follies are to be corrected, or wrongs redressed, two ways present themselves; force instigated by all the angry passions, & mild persuasion guided by wisdom, and inforced by the daily, and incontestible proofs of experience.

Shall then the barbarous [illeg]ting spirit of revenge prompt us to headstrong deeds of blood?

There is no evidence of pencil here (which may lend credence to the idea that the pencil was from an agent of Covent Garden). The passage is boxed in pen and marked ‘out’. The penholder seemed particularly exercised by the final line which is practically obliterated by extremely heavy strikethrough.

Further reading

John Barrell, Imagining the King’s Death (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Philip Cox, ‘“Perfectly harmless and secure?”: The Political Contexts of Thomas Holcroft’s He’s Much to Blame?’ in Miriam L. Wallace and A.A. Markley (ed), Re-Viweing Thomas Holcroft, 1745-1809: Essays on his Life and Work (Farnham & Burlington: Ashgate, 2012).

Amy Garnai, ‘‘A Lock Upon My Lips’: The Melodrama of Silencing and Censorship in Thomas Holcroft's Knave or Not?’, Eighteenth-Century Studies 43:4 (2010), 473-484.

William Hazlitt (ed), Memoirs of the late Thomas Holcroft, 3 vols(London: Printed for Longman et al, 1816).

[available on archive.org]

Thomas Holcroft, He’s Much to Blame (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1798)

[available on archive.org, Googlebooks]

Gary Kelly, ‘Holcroft, Thomas (1745–1809)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004; online edn Oct, 2006. [https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/13487, accessed 2 August 2018]

The Diary of William Godwin, (eds) Victoria Myers, David O'Shaughnessy, and Mark Philp (Oxford: Oxford Digital Library, 2010).

http://godwindiary.bodleian.ox.ac.uk