The Whim (1795) LA 1093/1104

Author

Lady Eglantine Wallace (d. 1803)

Wallace was born in Scotland, daughter of Sir William Maxwell and his wife Magdalene Blair. She had a reputation for boisterousness but this did not prevent her marriage to Thomas Dunlop, later baronet of Craigie, in 1770. That said, the pair separated in 1778.

She moved to London at an undetermined period after this and began to write. Her works include A letter to a Friend, with a Poem called the Ghost of Werter (1787) and Diamond Cut Diamond (1787). Her staunchly conservative politics can be read in Lady Wallace's address to the Margate volunteers, on the 28th of May, 1795, published to celebrate Pitt’s birthday, ‘the greatest Minister which this, or any other Country can boast; - the Terror of our Enemies—and the Hope of all Lovers of Law, Liberty, and Loyalty’.

Her play The Ton; or, Follies of Fashion (CG, 1788) was not a success and had only 3 performances. The playbill for the final performance states somewhat mysteriously (or perhaps merely diplomatically) that ‘The many Ladies and Gentlemen who have places for the succeeding Nights [of The Ton] are respectfully informed this Comedy cannot be performed after this Evening’ (London Stage, V:1055). After the play’s failure she sought to have her loyalist credentials confirmed by publishing A Sermon, Addressed to the PEOPLE, pointing out the only sure method to obtain a speedy Peace and Reform: this was advertised alongside other works including a second edition of The Whim (Oracle and Public Advertiser, 14 December 1795).

The failure of The Whim (1795) is thought to have provoked her into leaving England in outrage. She was arrested in Paris as a British agent in 1789 but could be found in Brussels in 1792. She died in Munich in 1803.

Plot

The plots of the two versions are essentially identical. There are some minor differences noted in the commentary below.

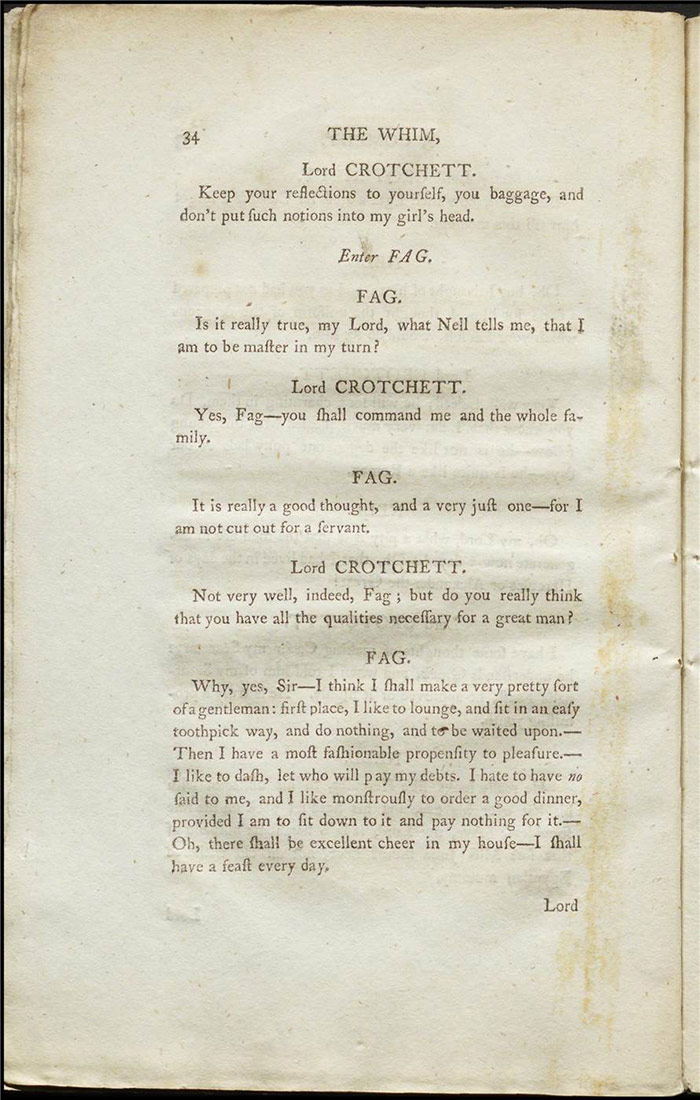

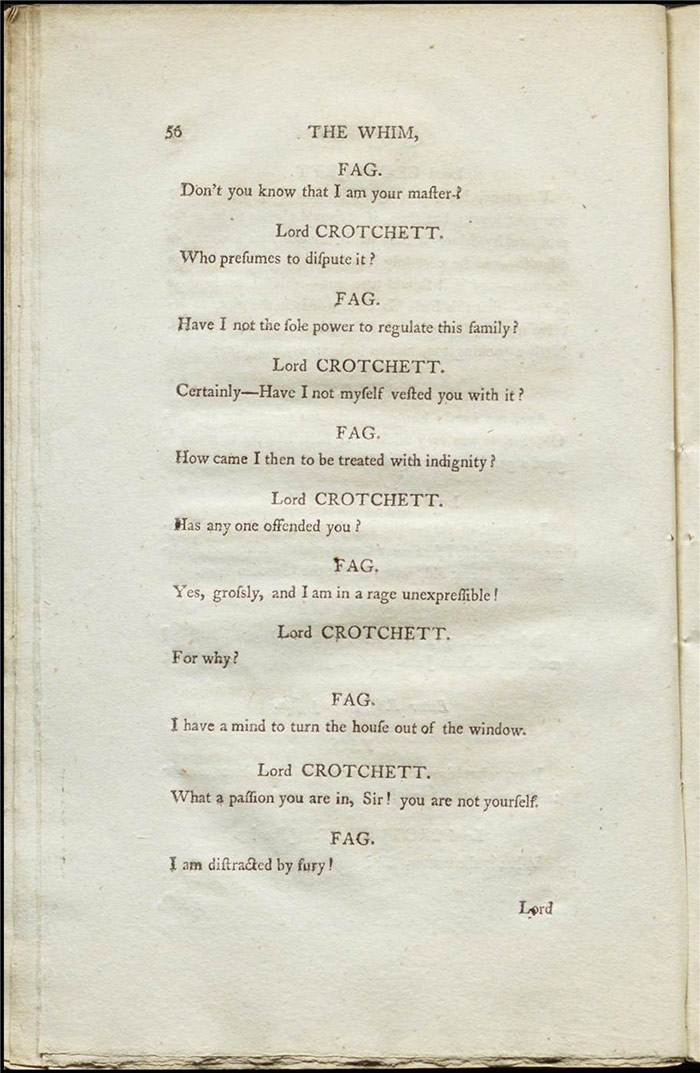

Lord Crotchet, ‘an old antiquarian’, has taken a Saturnalian whim to reverse the social order in his house for the day so that servants become the masters and vice versa. Fag and Nell, the servant and maid of the house, are excited by the prospect and have a fun conversation of what they will do when in power. Julia, daughter to Lord Crotchett, interrupts and we learn that Nell has allowed Julia’s lover, Belgrave, into the house disguised as a servant in the hope of finding an opportune moment to ask Crotchet for her hand in marriage (Crotchet has promised her to someone else). Lord Crotchett enters and offers his rationale—to ape classical Rome and Greece—for the reversal of places in the house. He is delighted with Caesar, the name Belgrave has taken while incognito, and he and Fag discuss the finer qualities required to be a ‘great man’. For his part, Fag wonders what he shall do with Lord Crotchet before deciding he should be a cook.

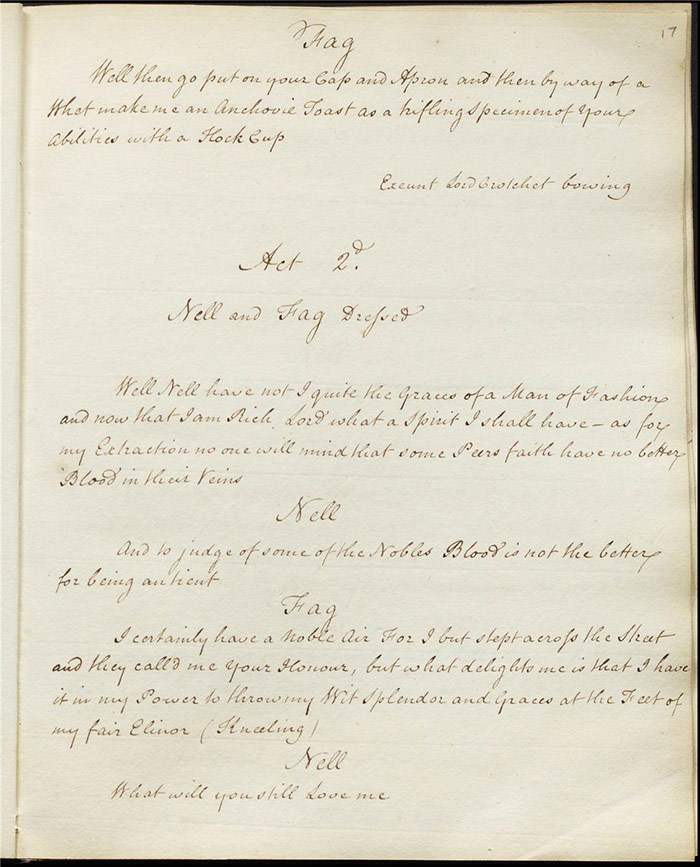

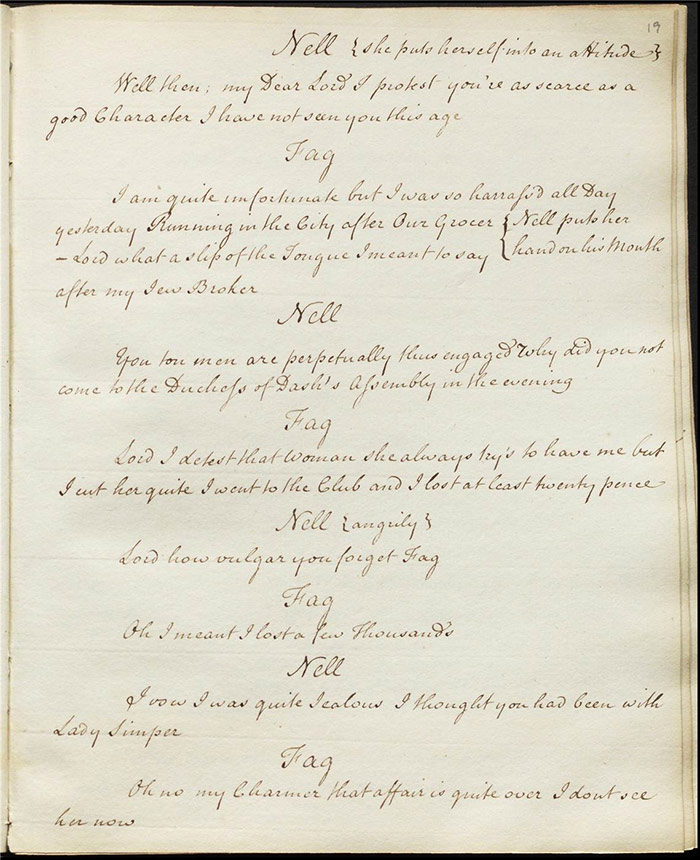

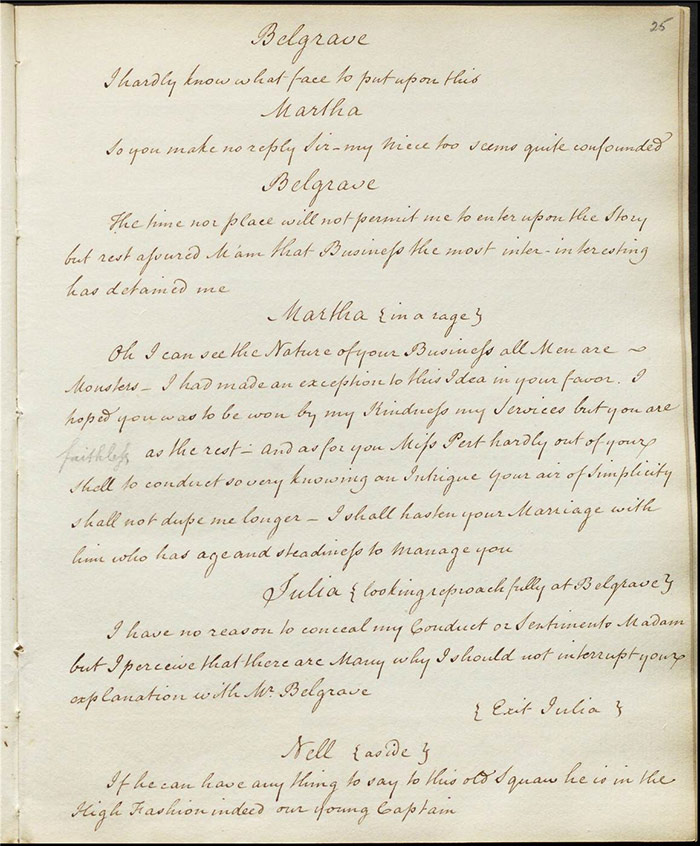

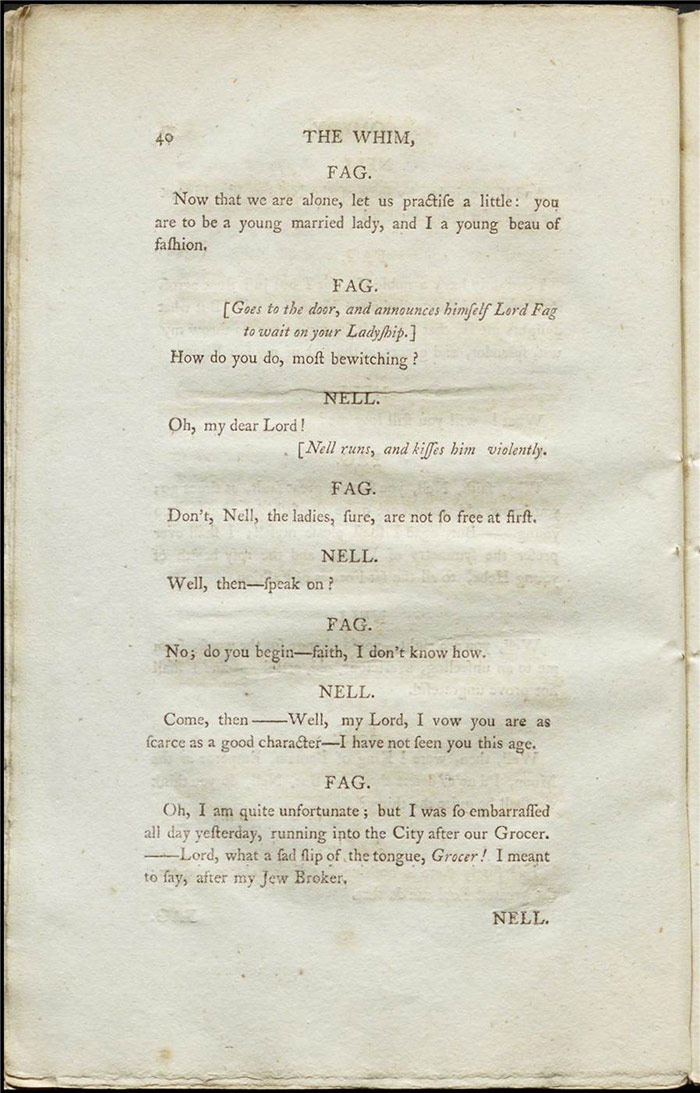

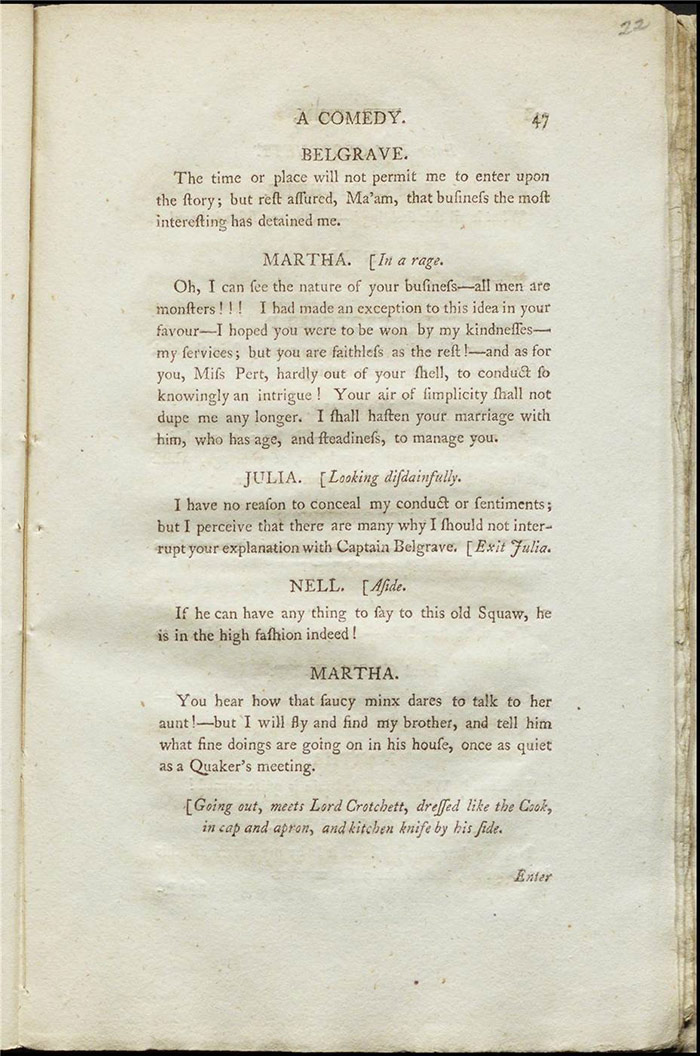

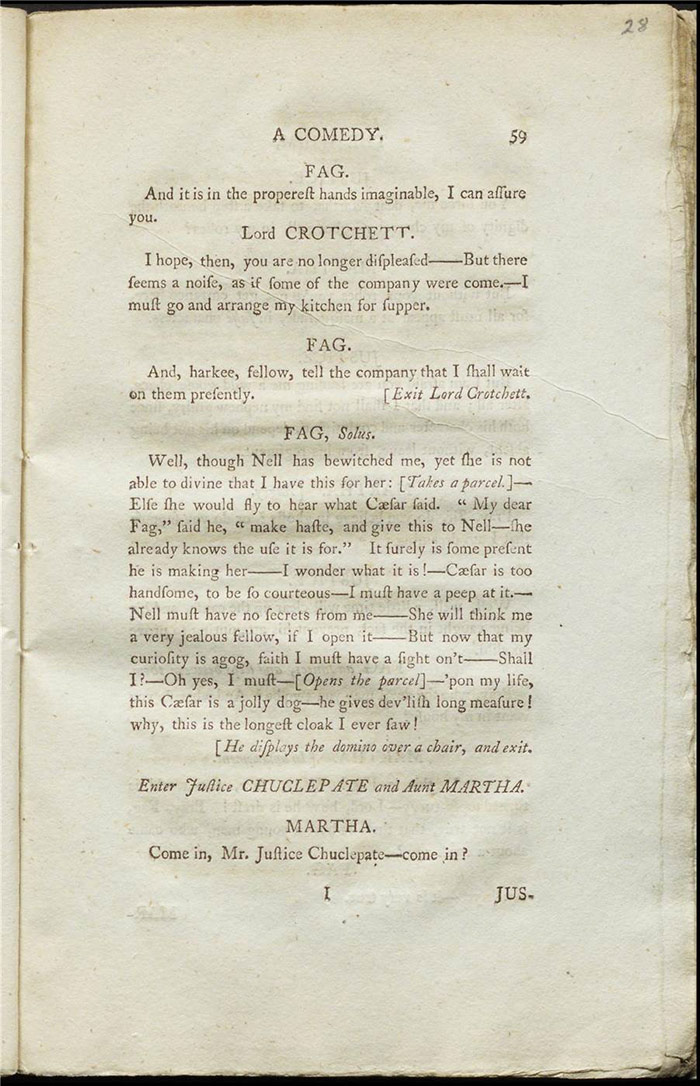

Fag and Nell, now dressed for the parts they will adopt, roleplay as wealthy lord and lady of fashion at the opening of act II (f.17r). Belgrave interrupts them and demands to know when he will see Julia – he is absent without leave from his regiment and is anxious that his uncle, Justice Chuclepate, shall discover him. Julia then enters dressed as a servant and tries to reassure him before her aunt Martha appears. She is enraged to discover Belgrave and runs to tell Lord Crotchet. However, he dismisses her with a laugh. She is even more angered and rushes off to tell Justice Chuclepate; perplexed at this turn of events, Crotchet follows her. On his return, he is still none the wiser but has decided to turn Caesar out of the house for the sake of prudence. Nell is dismayed but then Fag arrives and, playing the part of master of the house, berates Crotchet mightily and reverse Belgrave’s expulsion. Fag then lays down a long domino cloak which Belgrave has given him for Nell for a matter of subterfuge. Martha and Justice Chuclepate then enter and she fails to persuade him that his nephew Belgrave is in the house, Fag staunchly denying it. However, she convinces him to attend the night’s masquerade ball—wearing the cloak left down by Fag—so he can see for himself.

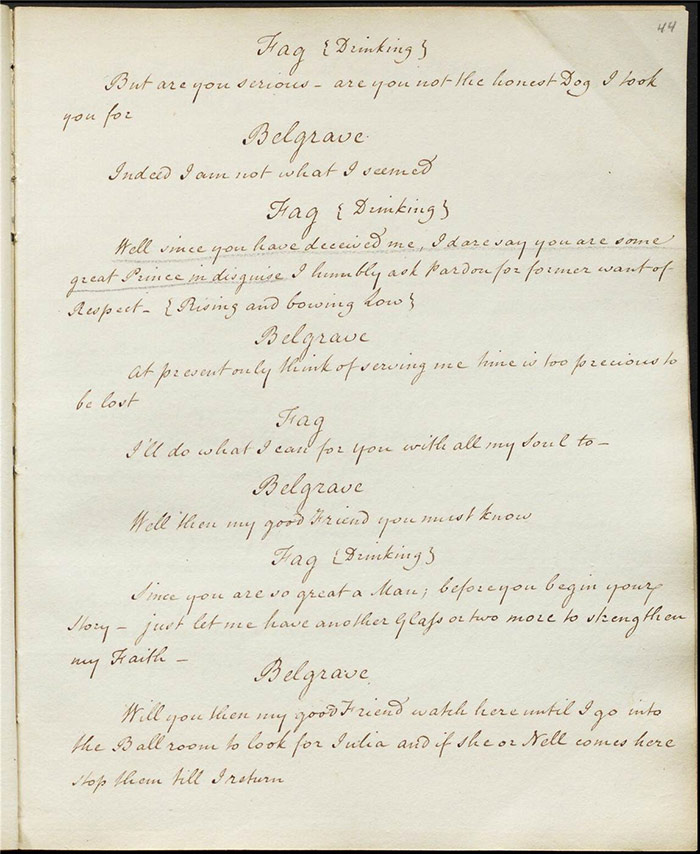

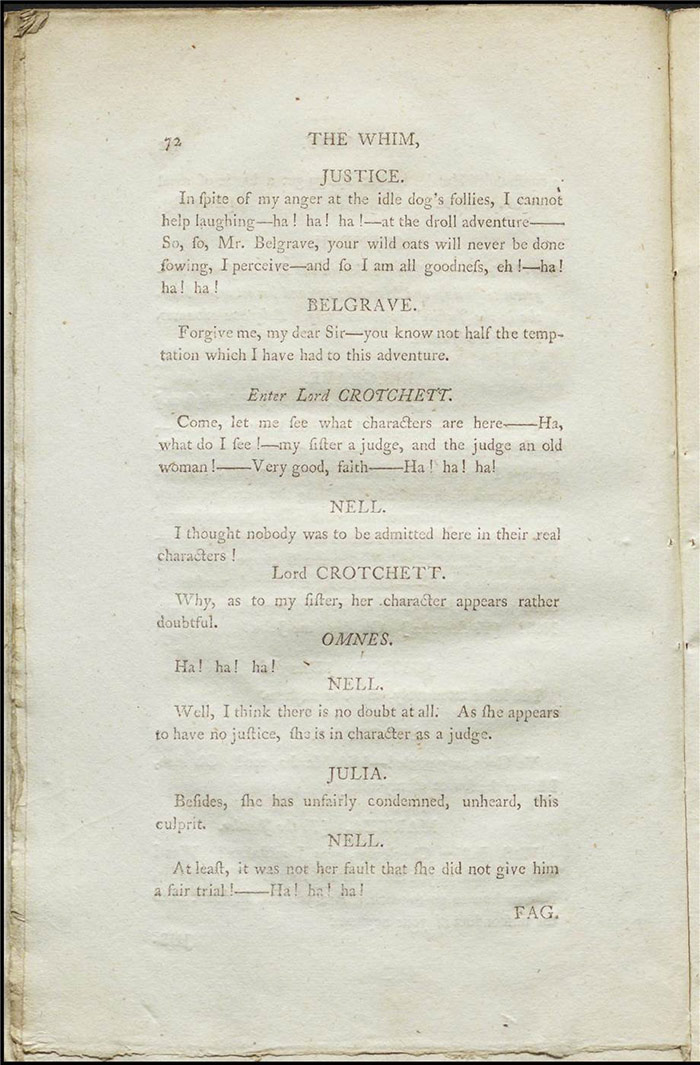

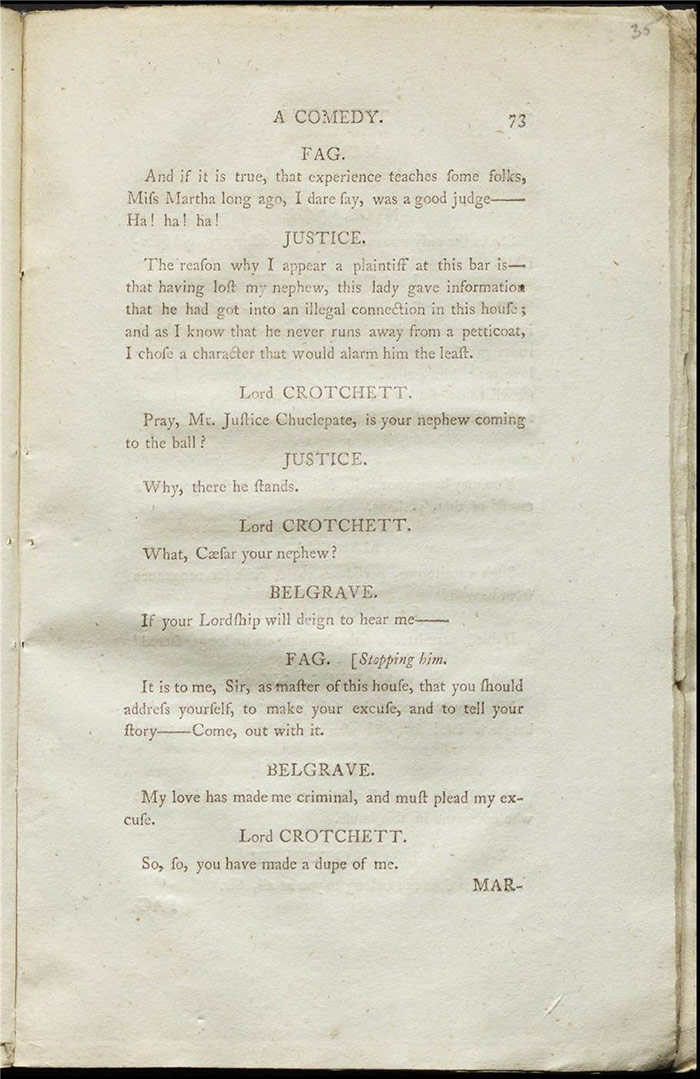

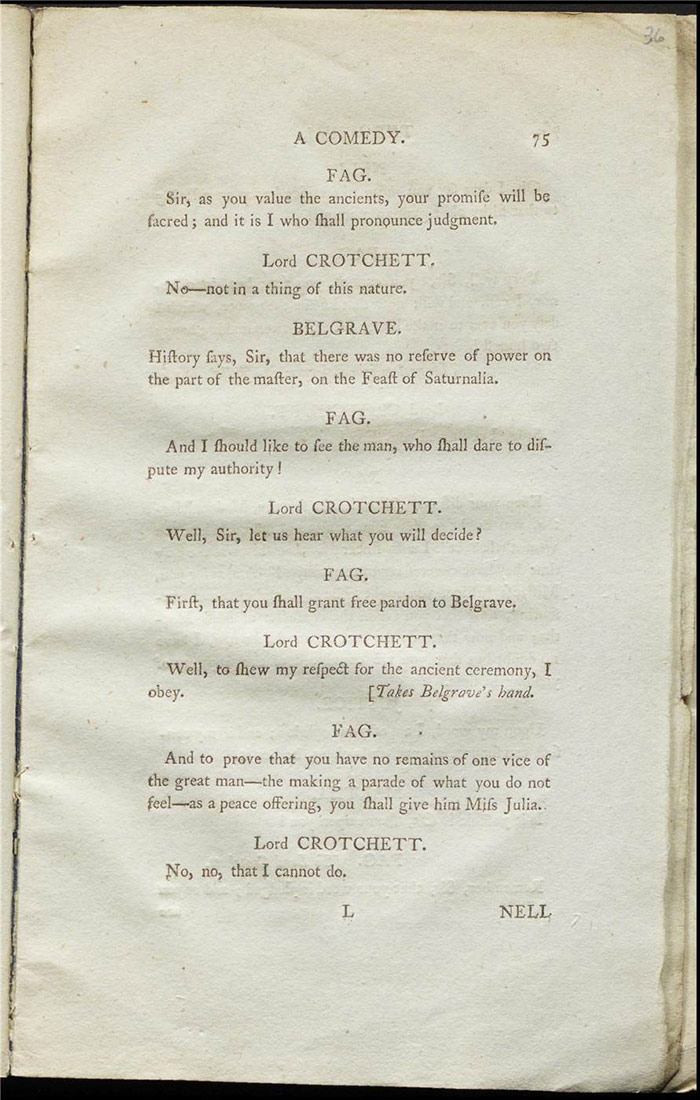

In the third act (as per the published version, no act III marked in corresponding manuscript folio, f.42r), Belgrave asks Fag, who is fully enjoying his temporary lofty status by imbibing generously, to watch out for Julia and Nell while he searches the ball for Julia. Unfortunately, when he goes into the masquerade, he unburdens himself to his uncle, who is wearing the domino cloak Belgrave had intended for Julia. However, although Martha is gleeful at being proved right, Chuclepate seems more amused, as is most of the company who gather round the scene. Lord Crotchet, on the other hand, seems irate but before he can seek sanction, Fag interrupts and invokes the power of the ancients to settle Belgrave and Julia together. The play ends with a reflective Crotchet declaring that he will never again cede the duties of his situation and his responsibility to uphold the constitution.

Performance, publication, and reception

The play manuscript was submitted to Larpent on the 7 September 1795 by Thomas Shaw, proprietor and manager of the Theatre Royal, Margate. He refused to issue a licence and Lady Wallace wrote in vain to Salisbury, the Lord Chamberlain to complain. Wallace speedily published the play with an irate ‘Address to the Public, upon the arbitrary and unjust aspersion of the licenser against its political sentiments’; it was advertised in the London newspapers on 15 October (Morning Chronicle) and published on 28 October (Morning Post and Fashionable World, Star).

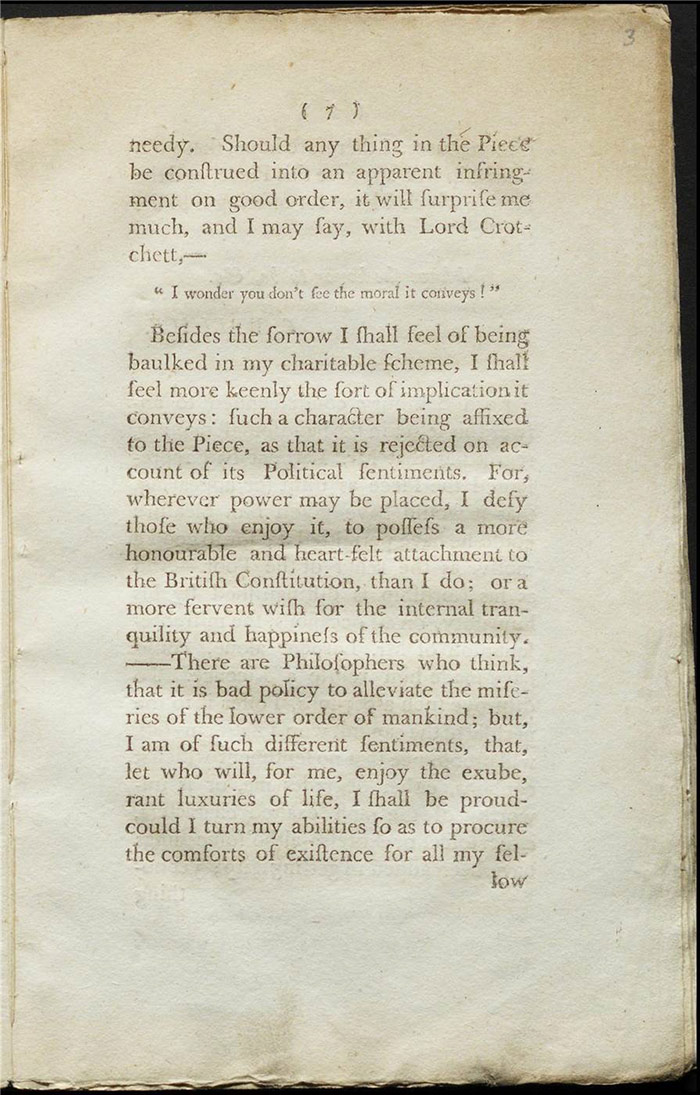

Wallace begins her ‘Address’ by pointing out that she wrote the comedy with a view to raising money for the poor of the isle of Thanet. Expressing her bemusement, Wallace then gives the text of her letter to Salisbury appealing Larpent’s decision. From this account, Wallace claims that Larpent did, in fact, give his permission only to withdraw it while promising to bring it to Salisbury for a final deliberation. It is clear that Wallace is troubled by the personal implications of having a play refused a licence:

Besides the sorrow I shall feel of being baulked in my charitable scheme, I shall feel more keenly the sort of implication it conveys: such a character being affixed to the Piece, as that it is rejected on account of its Political sentiments. For, wherever power be placed, I defy those who enjoy it, to possess a more honourable and heart-felt attachment to the British Constitution, than I do (LA 1104, f.3r)

Perhaps the most intriguing part of the letter is Wallace’s account of Salisbury’s reply. According to her representation of his letter, written in the ‘handsomest manner’, Salisbury expressed his regret for Larpent’s decision, particularly given the charitable motives behind the piece. Moreover, it would have given him pleasure to allow the piece ‘could he have permitted it’: the clear implication is that Salisbury submits to Larpent’s authority here or at least hides behind the convenience (LA 1104, f.3v). This offers us a rare glimpse of the dynamic between Examiner and Lord Chamberlain.

Wallace’s lengthy preface goes on to deal explicitly with the question of the French Revolution, arguing that satirical plays such as hers were important mirrors to society and goes so far as to say that if France had allowed such plays, it may be that the corrective influence of the stage may have curbed the excesses to the French elite and thus prevented them from pushing the people towards revolution:

The Stage is the only school which overgrown boys and girls can go to, and did the Licencer permit more satire, more sentiment, and less ribaldry, outrê pantomime, and folly, to appear under his auspices, it would be doing the State more service than thus taking alarm at The Whim of renewing the Saturnalia Feast. (LA 1104, f.6v)

Although the play was not performed, the controversy around it ensured the published version got some attention. The first number of the Monthly Mirror appeared in December 1795 and contained a review of The Whim as well as a letter to the Lord Chamberlain on the powers of the Examiner.

The review was not kind, describing the play as a ‘jumble of nonsense and vulgarity from beginning to end’. The writer objected to the politics of the piece and disputed Wallace’s assertion that they were unexceptionable. ‘If the stage is the “only school which over-grown boys and girls can go too”, appeals the review, ‘we are glad the Licencer has prevented this lesson from entering into the academy’.

However, although the Monthly Mirror was dismissive of Wallace’s comedy, a letter from ‘Honestus’, which appears immediately after the review, shares Wallace’s concern about the Examiner’s exercise of power. Larpent, it is suggested, gets things wrong and is not quite up to the job:

My LORD, it seems to me that it never entered into the conception of the ministry, that it was necessary for the LICENCER to be a man of talent. I don’t presume to know what talent may be requisite to make an officer of state, but the drama, MY LORD, it should be recollected, is a species of literature, one of the most useful and valuable, perhaps, we possess. I would not be thought wantonly to stigmatize the taste or discriminative powers of any person: but, MY LORD, prejudice may carry a man a great way; and when his vision is clouded by the mists of policy, he may imagine that to be a libel on government, which is in reality nothing more than a moral sentiment. (MM, 41)

Newspapers also took an interest in Wallace’s comedy. Wallace had attacked the press as being much worthier of the Licencer’s attention in her ‘Address’ which may account for the tone of much of the coverage.

The Morning Post and Fashionable World (19 October 1795) claimed, tongue firmly in cheek, that ‘Lady WALLACE expresses the greatest contempt for Lord SALISBURY’S Dramatic Judgment. She boasts of General DUMOUNIER and other Gentlemen having owned her Whim to be a good Piece’ (Dumouriez was a French general who had fled France and whom she had entertained in London). The Courier and Evening Gazette (3 November 1795) took pleasure in recording that ‘The Marquis of SALISBURY has declined the challenge of Lady WALLACE. His Lordship scorns to exercise his Wand to gratify the Whim of every person that may think proper to call upon him.

The Oracle and Public Advertiser seemed to be keen to cast a cloud over her character in other ways: ‘Lady Wallace is in the country. When her Ladyship gladdens the town with her presence we cannot tell: but be she in town or country, she is always happy in the company of young GORDON—and thereby hangs a tale’ (7 December 1795; Wallace’s sister, Jane, was married to Alexander Gordon, duke of Gordon)) and later, there is a rather more cryptic ‘Lady WALLACE is employing her extensive powers on a poetical translation of the tenth chapter of Nehemiah (24 December 1795). This may be related to a ribald ditty on Admiral Robert Roddam, attributed to Wallace, that appeared in the Tomahawk or Censor General (4 November 1795):

‘TO MRS ADM-L R-DD-M

By Lady Wallace

Is he alive?

At seventy-five?

Mrs R-DD-M’s Answer

He was not dead

When last in bed!

Further research is required to make sense of these references and connect them together. However, the circumstantial evidence does suggest that Wallace received a violent level of public opprobrium in the wake of her literary effort, all too consistent with that meted out to other women of this period.

Commentary

The manuscript (LA 1093) shows a number of emendations marked with underlining in pencil. Given the evidence of the preface and the similarity to other manuscripts from this time, we can be essentially certain that Larpent was responsible for the underlining.

The events of the French Revolution and the anxiety provoked in England as a result would have preyed heavily on Larpent’s mind. Thomas Paine published the first part of his Rights of Man in March 1791, just some months before Larpent received this submission, and it is thought that there were 50,000 copies in circulation by May, much to the discomfort of many.

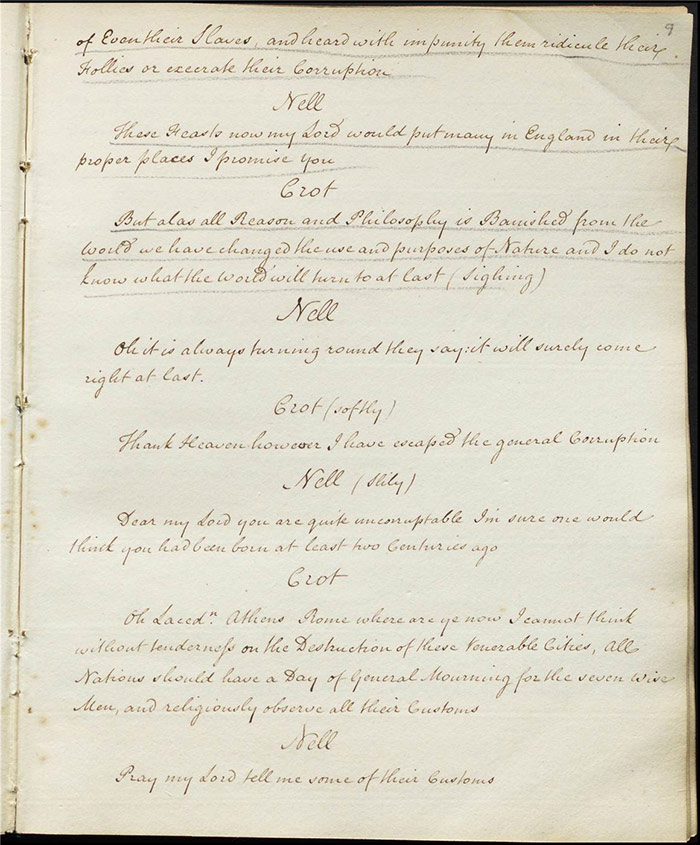

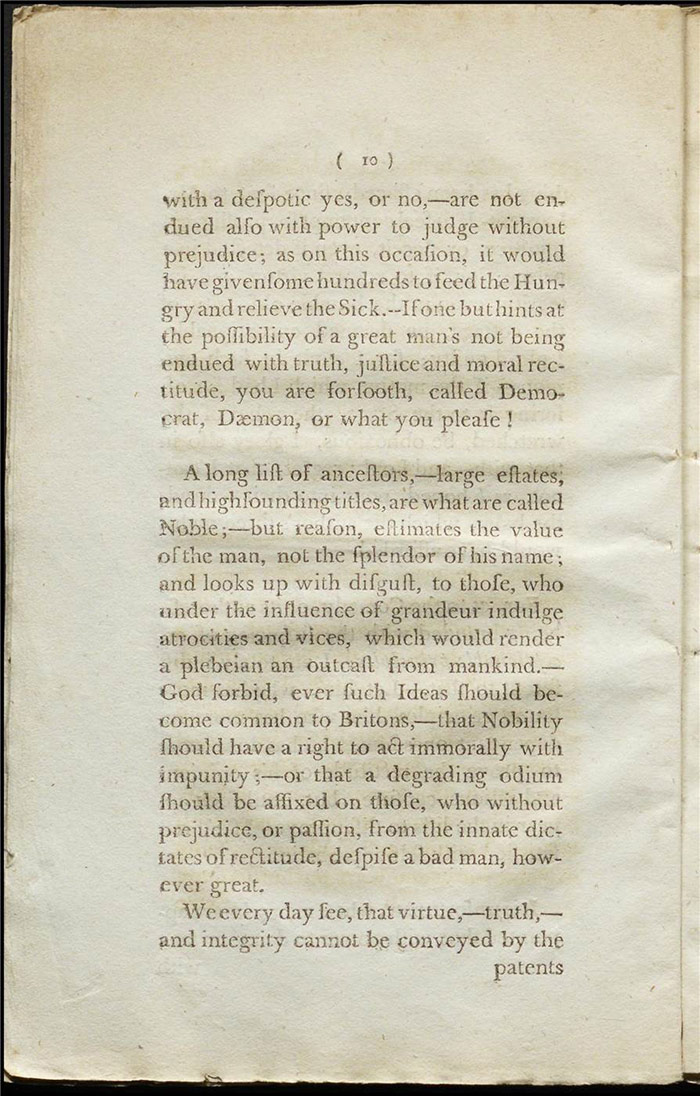

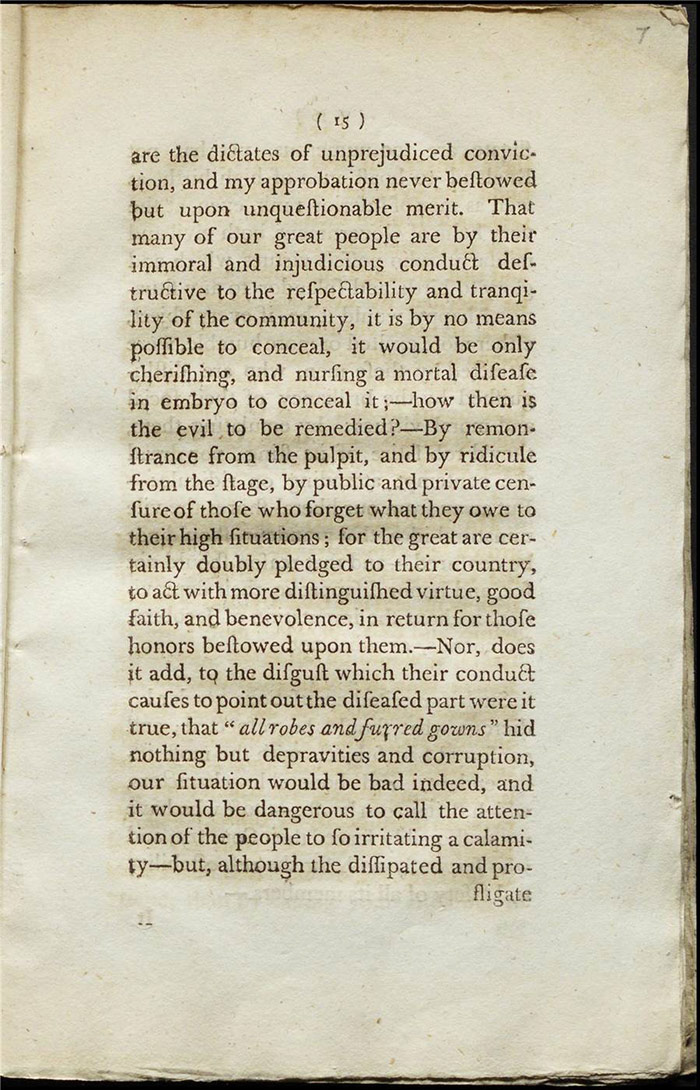

The passages underlined in the manuscript indicate the degree of Larpent’s trepidation. As early as (LA 1093, f.3r), we come across a leaf with almost all the dialogue, with references to ‘our debauchee Nobles’, ladies who are ‘liberal of [their] Favors’, and servants ‘laughing at the sorry figure some [sic] of Our Luberly Great Men’, marked for removal. More excisions related to rank can be seen on (LA 1093, f.9r), (LA 1093, f.11r), (LA 1093, f.15r), and (LA 1093, f.36r) but there are many more throughout the manuscript.

When asked to lay out the changes she would make on becoming a lady, Nell’s insistence that she would ‘have a fine Glorious Crop next year for I’d convert all their Swords into Ploughshares’ (LA 1093, f.5r) is also marked for omission, indicating that references to economic difficulties would not be tolerated. Fag’s claim that bread is ‘devilish dear’ (LA 1093, f.14r) is likewise deemed inadmissible.

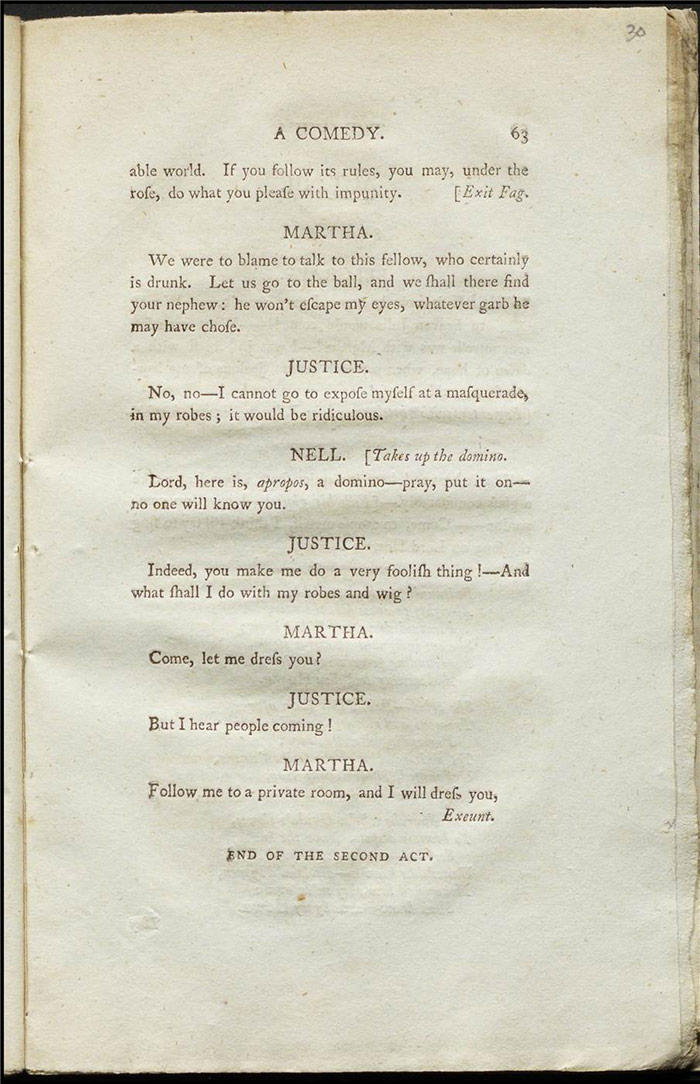

The figure of Justice Chuclepate is also held up to ridicule in a manner that Larpent deemed inappropriate. Not only is his blustering ‘No, no, I cannot go to expose myself at a Masquerade, a Judge in his Robes would be ridiculous’ marked for omission, so too is any minor affront to the judiciary’s dignity such as the faintest innuendo of Martha (a markedly conservative character) offering to dress him in a private room (LA 1093, f.41r-42r). See also (LA 1093, f.46r) and (LA 1093, f. 47r).

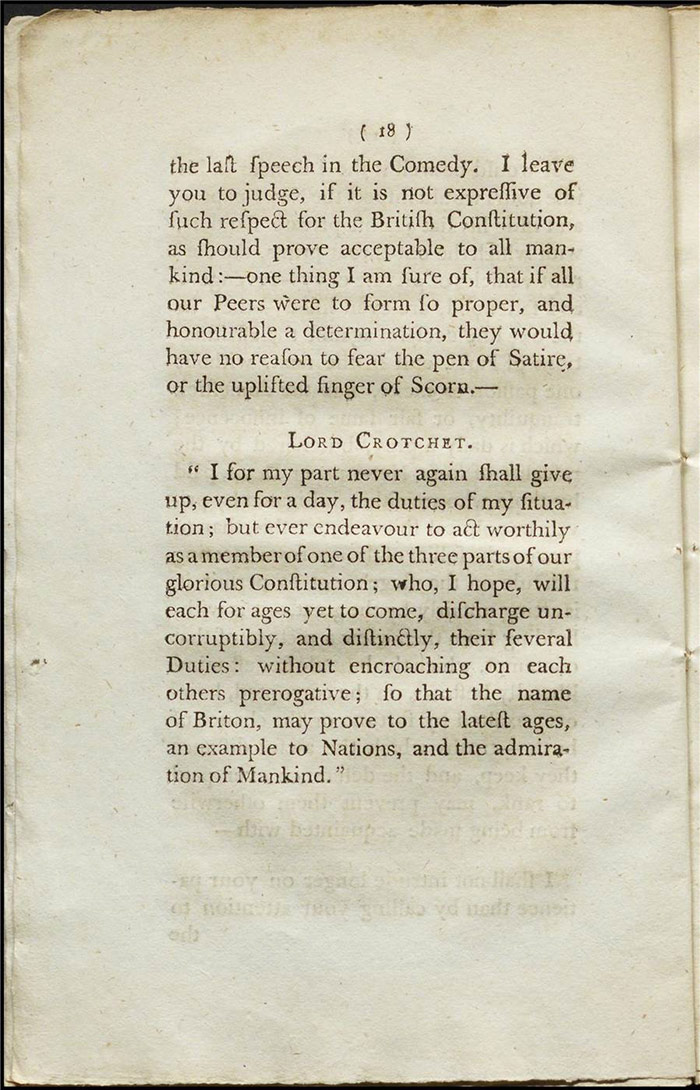

The final two speeches of the play deserve some attention. We may readily see why Nell’s speech, where she warns that society should never ‘let a flaw be long of Mending. Else it would soon get incurable; for a stitch in time, saves nine’, be inappropriately provocative for the Examiner, it being understood to refer to the fabric of the constitution. However, the entirety of Crotchet’s speech is also underlined by Larpent and this was a matter of particular indignation for Wallace, as we saw from her ‘Address’ which she unapologetically closes by quoting the speech in full. We might speculate that Larpent viewed Crotchet’s sentiments as overly humble and hopeful when a more emphatic endorsement of the current regime was required:

I shall never again give up even for a Day, the Duty of my Situation, But endeavour to Act worthy of one of those three Valuable Parts of Our Glorious Constitution. Who I hope will for Ages each distinctly discharge uncorruptibly their several Duties without encroaching on each^ others Prerogative so that the Name of Britons to the latest time, may be the Envy and Admiration of Mankind’ (LA 1093, f.55r; LA 1104, f.8v).

While Wallace was resolutely indignant in her ‘Address’ as to the innocence of her political sentiments, the published version has had some additions to make it more palatable. At the very least, we can say that Wallace felt she needed to refine some parts of the play in order that her political sympathies be more explicit.

There are two notable examples. Compare this early exchange between Fag and Nell as they imagine themselves in new positions of political power.

Fag: And I trust you’d make Peace Nell.

Nell: Oh that I would I should have a fine Glorious Crop next year for I’d convert all their Swords into Ploughshares.

Fag: And you’d surely untax us Nell.

Nell: No I’d tax all Luxuries: and Gaming. Men Milleners Dogs and Dolly’s so completely that every one should be able to pay for Bread if it was twice as dear (LA 1093, f.5r)

And in the published version:

Fag: […] I trust, then, you’d make peace?

Nell: Oh that I would: I should have a fine glorious crop next year, for I’d convert all their swords into ploughshares.

Fag: Then the French would come and gather it; and I suppose, you’d surely untax us Nell.

Nell: No: taxes are necessary evils. But I’d tax all luxuries, gaming, men-milleners, men-servants, dogs and dollies, so completely, that every one should be able to pay for bread, even if was twice as dear. (LA 1104, f.12rv)

Wallace makes the French threat to the nation more present in the revised version, as well as making Nell’s acceptance of sensible taxation an essential part of British life, particularly in times of war.

The more considerable amendment made to the published version is the insertion of a lengthy song by Fag to open the final act. While the manuscript version does note that Fag ‘sings’ (LA 1093, f.42r), Wallace appears to have taken the opportunity to bolster her claims of patriotism by including an unusually lengthy song (14 6-line stanzas) on Lord Howe’s 1794 naval victory. Howe’s victory had been the subject of a play by Richard Brinsley Sheridan The Glorious First of June produced in July 1794. The closing stanza of Wallace’s song (which appears to be original) will suffice to give a taste of it:

Encamp’d by nature, arm’d by God,

Britannia holds th’avenging rod,

To which the world does bow;

Triumphant o’er the main I’ll ride,

My wooden walls, brave foe and tide,

All nations yield to HOWE. (LA 1104, f.31v)

The ‘Address to the Public’ in the published version of the play has a number of lines underlined in pen. There are no marks on the play text itself.

It seems very probable that the underlining was done by Larpent himself as the marked-up text insinuates, at best, unfounded biases, or, at worst, corruption. Underlined are suggestions ‘that other motives, independant [sic] of the sentiments and merits of [the play], influenced his decision’ (LA 1104, f.1v); speculation that ‘Perhaps, Mr. Larpent may have more weighty reasons for objecting to the licensing the Piece’ (LA 1104, f.2v); and, finally, an insinuation that he was a ‘venal dependant [sic]’ (LA 1104, f.6v). Larpent’s interventions here may be usefully compared to his reaction to Theodore Hook’s complaints regarding the censorship of Killing No Murder (1809).

Further reading

J.K. Laughton, ‘Wallace, née Maxwell, Eglantine, styled Lady Wallace (d. 1803)’, rev. Rebecca Mills, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006

[https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28530, accessed 26 April 2017]

L. W. Conolly, The Censorship of English Drama 1737-1824 (San Marino: Huntington Library Press, 1976), 102-105.

Lady Eglantine Wallace, Lady Wallace's address to the Margate volunteers, on the 28th of May, 1795 (Margate, 1795)

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]

Monthly Mirror,1 (December 1795)

Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Songs, Duetts, Choruses &C in a New and Appropriate Entertainment called the First of June. (London: Printed by C. Lowndes, [1794])

[available on Eighteenth-Century Collections Online]